Automating Air-Sensitive Chemistry: Strategies for Safe, Efficient, and Scalable Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on automating air-sensitive chemical synthesis.

Automating Air-Sensitive Chemistry: Strategies for Safe, Efficient, and Scalable Synthesis

Abstract

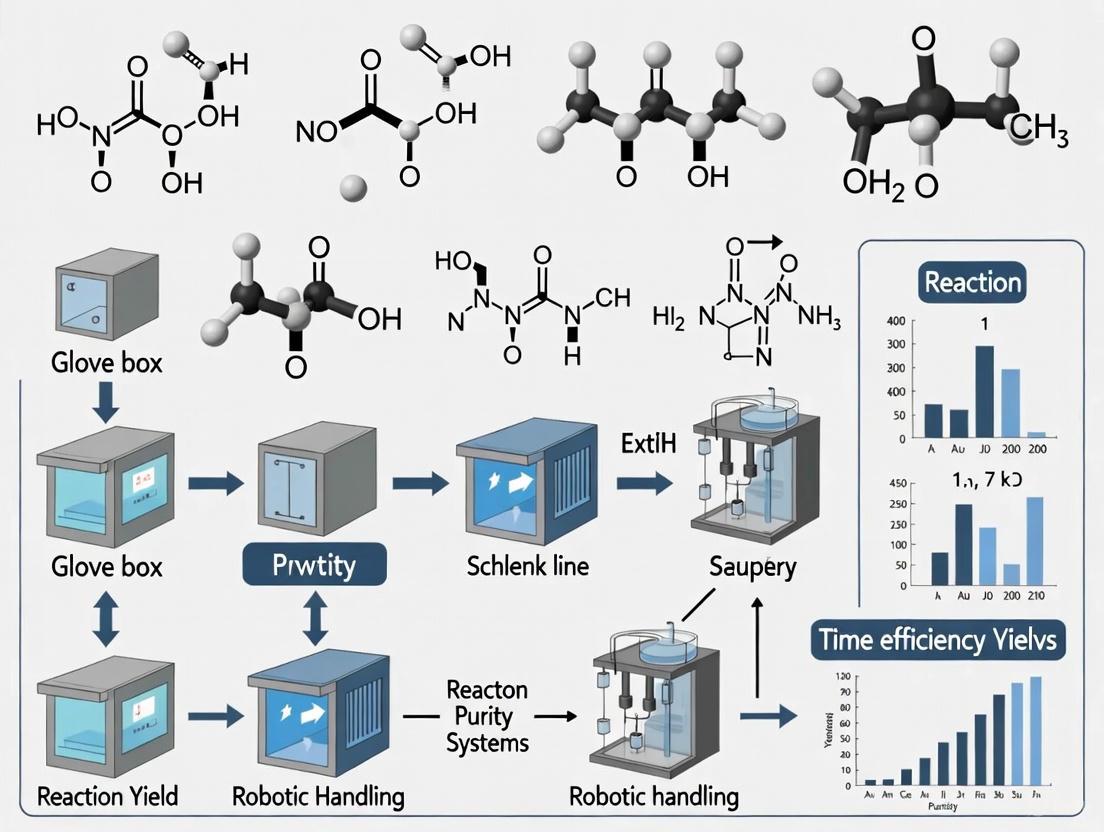

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on automating air-sensitive chemical synthesis. It explores the fundamental challenges of handling oxygen- and moisture-sensitive reactions and details the latest technological solutions, from programmable Schlenk lines and integrated robotic platforms to AI-driven optimization. The content covers practical methodologies for implementation, strategies for troubleshooting common issues, and frameworks for validating automated system performance. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications, this resource aims to accelerate the adoption of automation in process chemistry, enabling safer and more efficient development of pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals.

Understanding Air-Sensitive Chemistry and the Imperative for Automation

Air-sensitive reagents are chemical compounds that react with some constituent of air, most commonly atmospheric oxygen (Oâ‚‚) or water vapor (Hâ‚‚O), although reactions with carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚) or nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) are also possible [1]. These reactions can favor side-reactions, decompose reagents, or cause fires and explosions [2]. The handling of these compounds is critical in various chemical fields, from academic research to industrial drug development. This guide provides a technical foundation for troubleshooting common issues and outlines emerging automated strategies for managing these challenging substances.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My air-sensitive reaction failed, yielding no desired product. What are the most likely causes?

- A: The failure is most likely due to contamination from oxygen or moisture, which decomposed your reagents [2].

- Investigate Your Solvent: Ensure you are using extra-dry solvents. Inappropriate handling can cause solvent degradation over time, which is hard to detect but will interfere with experiments [2].

- Check Your Glassware: Confirm that all glassware was thoroughly cleaned and dried before use. Even minor air moisture condensation caused by temperature differences can be enough to cause a fire or decomposition [2].

- Inspect Your Inert Atmosphere: If using a Schlenk line, verify the integrity of the inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) supply and check that the system is leak-free. A malfunctioning bubbler or leaky tubing can introduce air [3].

Q2: I am new to handling pyrophoric materials like butyllithium. What is the safest way to dispense them?

- A: The safest method involves using specialized packaging and syringes under an inert gas.

- Use Specialized Packaging: Reagents packaged in systems like AcroSeal, which feature a multi-layer septum, limit exposure to the atmosphere [2].

- Follow Safe Dispensing Protocols:

- Use a syringe with an 18- to 21-gauge needle and a dry inert gas like nitrogen or argon.

- Pressurize the bottle by injecting the inert gas before withdrawing the desired amount of liquid.

- Alternatively, use a double-tipped needle—one to withdraw the liquid and the other to add inert gas from a gas line or balloon [2].

- Consider Syringe Material: While some protocols recommend glass syringes, less experienced users may find single-use polypropylene Luer lock syringes easier and safer to handle [2].

Q3: What are the fundamental differences between a Schlenk line and a glovebox, and when should I use each?

- A: The choice depends on the specific requirements of your experiment.

- Schlenk Line: Ideal for reactions performed in solution, as they lend themselves well to cannula and counterflow techniques. They use flexible tubing to connect apparatus and are best for manipulations where easy setup and takedown are needed [3].

- Glovebox: A sealed cabinet filled with an inert gas, allowing you to use normal laboratory equipment inside an isolated environment. This is necessary for handling solids that are extremely sensitive, for long-term storage of sensitive compounds, or for operating equipment that cannot be easily adapted to a Schlenk line [1].

Q4: What are the critical safety practices when working with highly reactive, air-sensitive compounds?

- A: Adherence to strict safety protocols is non-negotiable.

- Never Work Alone: Always have another person present who is familiar with the operation’s hazards and specific emergency procedures [4].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear a lab coat, eye protection, and appropriate chemical-resistant gloves [4].

- Know Emergency Procedures: Be aware of the location of emergency equipment like eyewash stations, safety showers, and fire extinguishers [4].

- Develop a Written SOP: For higher hazard chemicals, a written Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) is an effective tool for communicating hazards, safety precautions, and proper work procedures [4].

Automated Workflows for Quantifying Air-Sensitivity

Traditional handling of air-sensitive compounds is binary—treating them as either "air-sensitive" or "air-stable"—which limits reproducibility and mechanistic understanding. Modern research focuses on digital and automated workflows to quantitatively assess stability [5].

Experimental Protocol: Automated Degradation Profiling with ReactIR

This methodology enables reproducible, high-resolution degradation profiling of air-sensitive compounds [5].

- Workflow Integration: A modular digital workflow integrates an automated liquid handler, a stirring module, and an in-situ ReactIR spectrometer.

- Python Control: The central component is

ReactPyR, a Python package that provides programmable control of the ReactIR platform and seamless integration with the digital laboratory infrastructure [5]. - Sample Preparation: The automated liquid handler dispenses the target compound (e.g., a hexamethyldisilazide salt) and solvent into a sealed reaction vessel under a controlled atmosphere.

- Data Collection: The system exposes the sample to a controlled environment while the ReactIR probe collects real-time spectroscopic data (e.g., infrared spectra) at set intervals.

- Data Analysis: The

ReactPyRworkflow processes the spectral data to identify and quantify degradation products, generating precise degradation profiles and kinetic data that are unfeasible to obtain through conventional methods [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key equipment and materials essential for working with air-sensitive reagents.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Schlenk Line | A dual-manifold system (vacuum and inert gas) that allows glassware to be evacuated and refilled with an inert gas for handling air-sensitive compounds [1] [3]. |

| Glovebox | A sealed cabinet filled with an inert gas (Ar or Nâ‚‚) that allows manipulation of highly sensitive materials and equipment in an isolated environment [1]. |

| AcroSeal / Safe Packaging | Specialized packaging with a self-healing septum that allows safe storage and dispensing of air-sensitive liquids via syringe, limiting atmospheric exposure [2]. |

| Schlenk Flasks & Glassware | Specialized glassware with side-arms for connection to a Schlenk line, enabling reactions to be isolated from the atmosphere [3]. |

| Inert Gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) | Provides an oxygen- and moisture-free atmosphere. Nitrogen is typically preferred unless compounds react with it, in which case the more expensive argon is used [3]. |

| Uridine triphosphate trisodium salt | Uridine triphosphate trisodium salt, MF:C9H14N2Na3O15P3, MW:552.10 g/mol |

| Dammar-20(21)-en-3,24,25-triol | Dammar-20(21)-en-3,24,25-triol, MF:C30H52O3, MW:460.7 g/mol |

The field of air-sensitive chemistry is evolving from a purely manual, qualitative practice to a quantitative and automated science. By combining foundational techniques like Schlenk lines and safe dispensing methods with emerging digital workflows, researchers can achieve greater reproducibility, safety, and fundamental understanding in their work with these challenging yet essential reagents.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Air-Sensitive Chemistry

Q1: My air-sensitive reaction failed or yielded an unexpected product. What are the common causes? Failure in air-sensitive reactions often stems from incomplete oxygen or moisture exclusion. Even minor air exposure can decompose reagents, favor side-reactions, or cause no reaction to occur [2]. Using water-contaminated solvents in air-sensitive reactions is particularly dangerous and can lead to violent outcomes [2]. Check that all glassware is thoroughly clean and dry, as moisture condensation from temperature differences between labware and the environment can be enough to cause a fire [2].

Q2: How can I detect and locate a leak in my glove box? Signs of a glove box leak include a continuous increase in Oâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O levels when sealed, the system struggling to maintain pressure, or deflated gloves [6]. To confirm and locate a leak:

- Run an automated leak test if your system has one [6].

- Visually inspect for tears in the gloves or O-ring seals on the antechamber door [6].

- Check that all bolts around the window are sufficiently tight [6].

- Spray the outside of the glove box with soapy water while circulating nitrogen; bubbles will form where gas is escaping [6].

Q3: The Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O levels in my glove box are gradually increasing. What should I check? First, check that the circulation system is functioning [6]. Then, investigate further based on when the increase happens:

- During antechamber use: The issue could be the antechamber door seal [6].

- When you put your hands in the gloves: A hole in the gloves is a likely cause [6].

- During system purging: The inlet tubing or nitrogen source may be compromised [6]. If no leak is found, the oxygen sensor itself may need replacement [6].

Q4: How do I safely isolate a solid, air-sensitive product after a reaction? Common isolation methods under an inert atmosphere include [7]:

- Solvent Removal: Remove solvent under vacuum using a cold trap. To avoid "bumping," which can coat the flask with product, swirl the flask to redissolve splashed material [7].

- Filtration: Use a cannula with a fitted filter or a specialized sintered-glass filter stick to separate solid product from the solution [7].

- Precipitation/Recrystallization: Force the product out of solution by reducing solvent volume, cooling, or adding a solvent in which the product is sparingly soluble (e.g., adding hexane to dichloromethane) [7].

Q5: How can I protect air-sensitive samples when I need to remove them from the glove box for analysis? To protect samples outside an inert environment [6]:

- Encapsulation: For thin films, use UV-curable epoxy with a glass cover slide.

- Sealed Containers: Use screw-lid bottles, glass ampules, or vacuum-sealed bags.

- Short-Term Transfer: For brief exposures, zip-lock bags can offer some protection.

The following table summarizes quantitative data on the sensitivity of a desiccant material (DRIERITE) when exposed to ambient lab conditions versus a controlled glove box environment, demonstrating the critical need for inert environments [8].

| Time on Autosampler (minutes) | Moisture Uptake in Ambient Lab (%) | Moisture Uptake in Glove Box (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| 30 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| 60 | 0.59 | 0.00 |

| 120 | 0.85 | 0.00 |

| 180 | 0.92 | 0.00 |

| 300 | 0.92 | 0.00 |

| 1440 (24 hours) | - | 0.06 |

Experimental Protocol: A single granule of indicating DRIERITE was heated to 150°C to remove moisture, then placed on the autosampler for varying durations. The sample was heated again to 150°C, and the weight gain due to absorbed moisture was measured using TGA. One TGA was in ambient conditions; the other was installed inside a nitrogen-purged glove box [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Air-Sensitive Chemistry

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| AcroSeal Packaging | Specialized packaging with a multi-layer septum for safe storage and dispensing of air-sensitive liquids, limiting atmospheric exposure [2]. |

| Schlenk Line | A vacuum/inert gas manifold system for handling compounds that react with Oâ‚‚, water, or COâ‚‚, enabling reactions under an argon or nitrogen atmosphere [7]. |

| Inert-Atmosphere Glove Box | Provides a protective environment against oxygen, water vapor, and other reactive gases for long-term storage and handling of sensitive materials [9]. |

| Extra-Dry Solvents | Solvents with minimal water content to prevent undesired side reactions and hazardous situations when used with air-sensitive reagents [2]. |

| Sintered-Glass Filter Stick | Specialized glassware for filtering solid products under an inert atmosphere without exposure to air [7]. |

Workflow Diagram: Air-Sensitive Product Isolation

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for isolating an air-sensitive product after a reaction, from assessing stability to choosing the appropriate technique.

Workflow Diagram: Glove Box Leak Diagnostics

This troubleshooting flowchart guides you through the logical steps to diagnose the source of a leak in a glove box system.

FAQs: Core Concepts in Automation and Air-Sensitive Chemistry

Q1: What are the primary advantages of automating air-sensitive chemistry? Automation brings transformative improvements to air-sensitive workflows. Key advantages include enhanced reproducibility by eliminating human error in repetitive tasks, improved safety by minimizing researcher exposure to hazardous materials and conditions, and superior material efficiency through miniaturized and parallelized reactions. Furthermore, it enables the generation of high-quality, consistent data sets essential for machine learning and closed-loop optimization systems [10] [11] [12].

Q2: My research involves pyrophoric organometallic catalysts. Which air-free technique is most suitable? For handling highly reactive, pyrophoric compounds, a glove box is often the most secure option. It provides a continuously maintained inert atmosphere, allowing for open handling, weighing, and manipulation of materials with minimal risk of exposure. While Schlenk lines are excellent for chemical synthesis, a glove box offers a higher security level for straightforward but highly sensitive tasks like decanting or storing these materials [13].

Q3: We are setting up a high-throughput experimentation (HTE) lab. How can we address spatial bias in our microtiter plates? Spatial bias, where reaction outcomes vary between edge and center wells due to uneven temperature or light distribution, is a known challenge in HTE. Mitigation strategies include using specialized MTPs designed for uniform heating and stirring, ensuring proper calibration of irradiation sources for photochemistry, and implementing experimental design (DoE) strategies that randomize condition placement to decouple spatial effects from reaction variables [10].

Q4: What is the difference between automated and autonomous chemistry platforms? Automation involves using robotics to execute pre-defined human-designed procedures with high precision. Autonomy represents a higher level of capability, where the system can independently plan experiments, execute them, analyze results, and—crucially—use that analysis to form new hypotheses and decide what to do next, creating a self-improving loop. Most current platforms are automated, with true autonomy being a key goal for the future [14] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Automated Air-Sensitive Chemistry

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution Steps | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent yields across a microtiter plate | Spatial temperature gradient, uneven mixing, or evaporation bias [10]. | Verify calibration of heating block and shaker. Use an infrared camera to map plate temperature. Seal plates with chemically inert seals. | Implement randomized experimental design. Use calibrated, high-uniformity equipment. |

| Failed reaction due to suspected oxygen/moisture | Inadequate purging of reaction vessels, leak in gas supply, or compromised glove box atmosphere [3] [13]. | Check system for leaks with a pressure test. Verify inert gas purity and bubbler function. Regenerate glove box antechamber and catalyst. | Establish routine leak-check protocols. Monitor Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O levels in glove boxes continuously. |

| Clogging in automated liquid handling lines | Precipitation of solids, use of viscous solvents, or crystallization in lines [15]. | Flush system with a compatible solvent. Inspect and clean or replace clogged tubing and nozzles. | Pre-filter all solutions. Use temperature control on fluidic paths. Optimize solvent choice for solubility. |

| Poor data quality from in-line LC/MS | Carryover from previous samples, column degradation, or misalignment of autosampler. | Run blank solvent injections. Perform LC/MS system maintenance (column cleaning/replacement). Recalibrate autosampler position. | Implement robust washing cycles between samples. Adhere to a strict instrument maintenance schedule. |

| Robotic arm fails to grip vial | Incorrect vial type/size, misaligned rack, or faulty sensor. | Manually reset the vial and rack. Check and recalibrate the gripper's force and position sensors. | Standardize labware across the platform. Perform regular calibration and sensor checks. |

Detailed Protocol: Establishing an Inert Atmosphere on a Schlenk Line

The Schlenk line is a cornerstone tool for air-sensitive synthesis. This protocol details the proper procedure for rendering a piece of glassware inert.

Principle: The technique of "Evacuate-Refill" (or "Pump-Purge") uses repeated cycles of applying a vacuum to remove the ambient atmosphere and refilling with an inert gas to displace any residual air [3].

Materials:

- Schlenk line connected to a vacuum pump and inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) supply.

- Cold trap (for solvent vapor protection).

- Schlenk flask or similar glassware with a sidearm.

- Grease for ground-glass joints.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Ensure the cold trap is filled with liquid nitrogen or a dry-ice/acetone mixture. Apply a thin, even layer of vacuum grease to all ground-glass joints to ensure an air-tight seal [3].

- Initial Connection: With the flask's tap open to air, connect it to the Schlenk line via flexible tubing.

- Evacuation: Close the flask's tap. Slowly open the Schlenk line's vacuum tap to evacuate the flask. Hold under vacuum for 15-30 seconds.

- Refilling: Close the vacuum tap and slowly open the inert gas tap to fill the flask with gas.

- Cycling: Repeat the Evacuate-Refill cycle (steps 3-4) at least three times. This ensures the atmospheric gases inside are sufficiently diluted and removed.

- Completion: After the final refill cycle, the flask is under a positive pressure of inert gas. The flask is now ready for the reaction to be set up under this inert atmosphere.

Visual Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Automated Air-Sensitive Research

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Schlenk Line | Dual-manifold system for performing chemical reactions under inert vacuum or gas atmosphere. Essential for synthesis, cannula transfers, and other manipulations [3] [13]. | Requires a vacuum pump, cold trap, and inert gas supply. Nitrogen is common; argon is used for highly sensitive species. |

| Glove Box | Sealed chamber with an inert atmosphere and attached gloves, allowing for direct, open-vessel manipulation of air-sensitive materials [13]. | Ideal for long-term storage, weighing solids, and operating equipment that fits inside. Requires monitoring of Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O levels. |

| Microtiter Plates (MTPs) | Multi-well plates (e.g., 96 or 384-well) that enable high-throughput experimentation (HTE) by running numerous reactions in parallel [10] [11]. | Material compatibility with organic solvents is critical. Sealing methods must prevent evaporation and contamination. |

| Inert Gas (Nâ‚‚/Ar) | Creates an oxygen- and moisture-free environment. Used to purge reaction vessels, maintain positive pressure in lines, and fill glove boxes [3]. | Gas purity is paramount. Can be passed through drying columns to remove trace Hâ‚‚O/Oâ‚‚. Argon is denser, providing better blanketing. |

| Chemical Description Language (XDL) | A hardware-agnostic programming language for describing chemical synthesis procedures in a standardized, machine-readable format [14] [15]. | Enables reproducibility and sharing of synthetic protocols across different automated platforms. |

| 24,25-Epoxytirucall-7-en-3,23-dione | 24,25-Epoxytirucall-7-en-3,23-dione, MF:C30H46O3, MW:454.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| endo-BCN CE-Phosphoramidite | endo-BCN CE-Phosphoramidite, MF:C24H40N3O5P, MW:481.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Workflow: Integrating AI with Air-Sensitive Automation

The frontier of laboratory automation lies in closing the loop between AI-driven hypothesis generation, robotic execution, and data analysis. This workflow is key to achieving true autonomy.

Visual Workflow:

Methodology:

- AI-Driven Planning: An AI model (e.g., a retrosynthesis algorithm or a Bayesian optimizer) proposes a synthetic target or a set of reaction conditions to test, generating a machine-readable protocol [14] [15].

- Robotic Execution: The automated platform, housed within a glove box or using Schlenk techniques, executes the protocol. This involves precise liquid handling, temperature control, and stirring in an air-free environment [14] [15].

- In-line Analysis: The reaction crude is automatically sampled and analyzed using integrated analytical instruments like LC/MS or NMR. The key challenge is automated structural elucidation and yield quantification without manual intervention [15].

- Data Integration & Learning: The analytical results are processed and fed back to the AI model. This data, rich in procedural detail, is used to refine the model's predictions, creating a self-improving, closed-loop system that accelerates discovery and optimization beyond human-only capabilities [14] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Residual Moisture Levels

Problem: After purging, your system fails to achieve the required sub-ppm moisture levels.

Check 1: Inert Gas Purity

- Verify the purity specification of your nitrogen or argon gas supply. For sub-ppm work, the gas itself must be of ultra-high purity (e.g., 99.999% or better).

- Install or check the condition of gas purifiers or drying columns in your gas line, as these can become exhausted over time [3].

Check 2: System Leaks

Check 3: Outgassing

- Consider internal outgassing from chamber walls, hoses, or other components. This is a common source of moisture in vacuum systems [16].

- Implement a baking procedure if your system allows it, to accelerate the desorption of water vapor from internal surfaces.

Guide 2: Managing Vacuum Pump Performance Issues

Problem: The vacuum pump fails to reach or maintain the desired base pressure for effective degassing.

Check 1: Pump Oil and Maintenance

- For oil-sealed pumps (e.g., rotary vane pumps), check the condition of the pump oil. Degraded or contaminated oil will significantly reduce pumping efficiency and ultimate vacuum. Change the oil if it appears cloudy or discolored [17].

- Adhere to the manufacturer's recommended service intervals for your specific pump model [17].

Check 2: Cold Trap Operation

- Ensure the cold trap is correctly installed between your vacuum chamber and the pump. The cold trap, typically cooled with liquid nitrogen or a dry-ice/acetone mixture, protects the pump by condensing volatile solvents and water vapor, preventing them from degrading the pump oil [3].

- Verify the cold trap is not blocked with condensed material, which can restrict pumping speed.

Check 3: Process-Related Contamination

- Be aware that handling condensable vapors or reactive gases without a proper cold trap can lead to corrosion, fouling, or hydraulic shock inside the pump, especially in dry screw vacuum pumps [17].

- Maintain proper thermal management of the pump to prevent internal condensation of process vapors [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind using vacuum and inert gas for air-sensitive chemistry?

The core principle is to create a controlled environment isolated from the atmosphere. A vacuum pump removes the bulk of the air (including Oâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O), while an inert gas (like Nâ‚‚ or Ar) is used to backfill the system, providing an oxygen- and moisture-free atmosphere for handling sensitive compounds [3]. This two-step process is often repeated in cycles to progressively dilute and remove contaminants.

Q2: How do I choose between nitrogen and argon for my inert atmosphere?

Nitrogen is typically the preferred gas due to its lower cost. However, argon must be used if you are working with compounds that are reactive toward nitrogen [3]. Argon, being denser than air and nitrogen, can also provide a better protective blanket in open configurations like gloveboxes.

Q3: What are the different methods for purging a system?

The three common purging approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table: Comparison of Common Purging Techniques

| Purging Method | Basic Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Flowing Gas Purge [18] | Continuous flow of inert gas through the system, displacing the existing atmosphere. | Simple geometries without long dead-end branches. |

| Pressurizing-Venting Cycle Purge [18] | System is pressurized with inert gas and then vented; repeated cycles dilute contaminants. | Complex systems, including those with long dead ends (e.g., certain gas cylinders). |

| Vacuum Purging [18] | System is evacuated with a vacuum pump and then backfilled with inert gas. | Systems that can withstand vacuum pressure; often the most efficient method. |

Q4: My Oâ‚‚ sensor readings seem inaccurate. How can I troubleshoot this?

- Perform a Response Test: For a simple functional check, gently blow on the sensor. You should observe a decrease in the oxygen reading, confirming the sensor is responsive [19].

- Check Calibration: Oxygen sensors can drift over time. Perform a two-point calibration using 0% and a known reference point (e.g., 20.9% for air) [19].

- Proper Storage: Always store the Oâ‚‚ sensor in an upright position to maintain its longevity and accuracy [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Air-Sensitive Research

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Schlenk Line [3] | A dual-manifold vacuum/inert gas system that is the central workstation for handling air-sensitive materials. |

| Inert Gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) [3] | Provides an inert atmosphere; supplied from high-purity cylinders or liquid Dewars. |

| Vacuum Pump [3] [17] | Removes air and volatiles from the system. Types include oil-sealed rotary vane pumps (common for Schlenk lines) and dry screw pumps (for clean, oil-free operation). |

| Cold Trap [3] | Fitted between the vacuum line and pump to condense solvents and water vapor, protecting the pump and improving vacuum. |

| Gas Purifier/Drying Column [3] | Installed in the inert gas line to remove residual Oâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚O, ensuring gas purity is adequate for sub-ppm work. |

| Schlenk Flasks & Tubes [3] | Specialized glassware with side-arms for easy connection to the Schlenk line. |

| High-Vacuum Grease [3] | Used on ground-glass joints and taps to create airtight, reversible seals. |

| Bubbler [3] | Fitted to the inert gas outlet to provide a visible monitor of gas flow and a pressure release for the system. |

Experimental Workflows for System Preparation

Workflow 1: Initial System Evacuation and Purging

This diagram illustrates the logical sequence for preparing a contaminated system for air-sensitive work.

Workflow 2: Leak Testing and System Integrity Verification

This diagram outlines the process for verifying the integrity of a sealed system.

Implementing Automated Platforms: From Schlenk Lines to Integrated AI Systems

Troubleshooting Guides

Schlenk Line and Inert-Atmosphere Reactors

Problem: Poor Vacuum Pressure

Poor vacuum pressure is a primary indicator of a system leak or blockage, easily identified when solvents are not being removed effectively or oil is sucked from the bubbler into the inert gas manifold [20].

- Identification and Resolution Workflow:

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for System Leaks: Isolate parts of the Schlenk line to identify the leak source. Individually twist each stopcock to the inert gas line and observe if the manometer reading changes significantly [20].

- Inspect Solvent Trap: A blocked or warm solvent trap can cause poor vacuum. If the trap is blocked by frozen solvents (common with benzene or dioxane), shut down the line, thaw, and empty it. Ensure the trap is topped up with liquid nitrogen [20].

- Evaluate Vacuum Pump: If leaks and blockages are ruled out, the issue may be with the vacuum pump itself, requiring professional maintenance [20].

Problem: Slow or Failed Cannula Transfers

Slow transfers can disrupt the integrity of an inert atmosphere during fluid movement [20].

- Identification and Resolution Workflow:

- Corrective Actions:

- Seal Integrity: Replace leaky rubber septa [20].

- Flow Path: Clean or unblock the cannula and bleed needle [20].

- Pressure and Gravity: Increase the inert gas pressure slightly or raise the transfer flask (or lower the receiving flask) to improve flow [20].

- Filtration Blockages: For cannula filtrations, allow fine solids to settle before filtration and replace the cannula filter. Lower the filter into the suspension slowly to prevent blockages [20].

Problem: Contamination from Sucked-In Materials

Accidentally sucking solids or solvents into the Schlenk line is a common issue [20].

- Immediate Action: Close the stopcock to vacuum immediately to prevent further contamination [20].

- Preventive Measures:

- Use an external trap between the reaction flask and the Schlenk line vacuum manifold [20].

- Attach a hosing adapter with a glass frit for fine solids [20].

- Open the vacuum stopcock slowly and incrementally, especially when drying fine solids or using volatile solvents, and ensure adequate stirring to prevent bumping [20].

Problem: Seized Stoppers and Stopcocks

Ground glass joints can seize under vacuum if inadequately greased or left unused for long periods [20].

- Resolution: Gentle heating with a heat gun can expand the glass and loosen the grease. Always wear appropriate heat-resistant gloves to prevent burns. If unsuccessful, consult a professional glassblower for safe separation [20].

Specialized Glassware

Problem: Poor Cleaning Results in Laboratory Glassware Washers

Residue on cleaned glassware can introduce contaminants into sensitive reactions [21].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Cleaning Path: Verify spray arms rotate freely and that nozzles and filters are clean of debris [21].

- Chemicals and Water: Ensure correct detergent type and concentration, and check that water temperature meets the manufacturer's specifications. Use deionized or purified rinse water to prevent mineral spots [21].

- Loading: Avoid overloading the washer racks, as this prevents proper spray coverage [21].

Problem: Glassware Calibration Out of Tolerance

Inaccurate glassware leads to volumetric errors in quantitative analysis [22].

- Calibration Workflow for Volumetric Flask:

- Preparation: Clean and grease the glassware. Bring it and distilled water to room temperature for at least one hour [22].

- Weighing: Record the weight of an empty, dry flask [22].

- Filling: Fill the flask with distilled water just below the mark, then adjust the meniscus precisely to the calibration mark [22].

- Calculation: Weigh the filled flask. Convert the mass of water to volume using standard temperature-correction Z-factors (e.g., 1.00285 mL/g at 20°C for AR-Glas) [22].

- Acceptance: Compare the calculated volume to the acceptable tolerance limits for the glassware class [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core working principles for safely operating a Schlenk line? A1: Key principles include [23]:

- Always performing multiple vacuum and inert gas cycles on oven-dried glassware to thoroughly remove air and moisture.

- Maintaining a slight positive pressure of inert gas during manipulations to prevent air ingress.

- Using a dynamic vacuum to remove volatile solvents.

- Ensuring all connections, including greased ground glass joints or Teflon taps, provide an airtight seal.

Q2: How can I monitor my Schlenk line's health? A2: "Know your own Schlenk line" by familiarizing yourself with its normal operation [23]. Key indicators include the typical vacuum pressure reading, the sound of the vacuum pump, and the standard inert gas flow rate and pressure. Any deviation from these baselines can signal an emerging problem.

Q3: My glassware comes out spotted from the lab washer. What should I do? A3: Spots or cloudiness are typically caused by mineral deposits from the rinse water [21]. Switch to using deionized or purified water for the final rinse. Also, check and adjust the detergent concentration if streaking occurs, and ensure the water softener salt is not exhausted.

Q4: How often should a laboratory glassware washer be serviced? A4: Follow a structured maintenance schedule [21]:

| Frequency | Key Maintenance Actions |

|---|---|

| Daily | Inspect for residue; clean coarse and fine filters; check spray arms for free rotation; verify chemical levels. |

| Weekly | Deep clean interior surfaces and door seals; inspect racks for damage; run an empty maintenance cycle with detergent. |

| Monthly | Descale the machine; inspect the dosing system and door seals; lubricate hinges as per manufacturer guidelines. |

| Annually | Schedule professional servicing to calibrate and validate performance. |

Q5: What is the tolerance for a Class A 50 mL volumetric flask? A5: According to standards, a Class A 50 mL volumetric flask has a tolerance of ±0.05 mL [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calibration of a Volumetric Flask

This standard operating procedure ensures analytical accuracy [22].

- Objective: To confirm that the nominal volume of glassware is within prescribed tolerance limits.

- Scope: Applicable to volumetric flasks, pipettes, and burettes used in quality control.

- Materials: Glassware to be calibrated, distilled water, analytical balance, thermometer, tissue paper.

- Method (for a Volumetric Flask):

- Clean the flask to ensure it is free of grease [22].

- Allow the flask and distilled water to equilibrate to room temperature for at least one hour [22].

- Weigh the clean, dry, empty flask. Record the weight (W~empty~).

- Fill the flask with distilled water so the meniscus bottom is aligned with the ring mark. Ensure no water is above the meniscus; wipe the outside dry [22].

- Weigh the filled flask. Record the weight (W~filled~).

- Calculate the mass of water: Mass~water~ = W~filled~ - W~empty~.

- Record the water temperature and find the corresponding Z-factor (mL/g) from a standard table (e.g., 1.00285 mL/g at 20°C) [22].

- Calculate the actual flask volume: Volume~actual~ (mL) = Mass~water~ × Z-factor.

- Compare the actual volume to the nominal volume. The difference must be within the tolerance limit for the glassware class (see Table 1).

Table 1: Selected Tolerance Limits for Common Volumetric Glassware (Class A)

| Glassware Type | Nominal Capacity (mL) | Tolerance (± mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Flask | 50 | 0.05 [22] |

| Volumetric Flask | 100 | 0.06 [22] |

| One-Mark Pipette | 10 | 0.02 [22] |

| One-Mark Pipette | 25 | 0.03 [22] |

| Burette | 50 | 0.05 [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Air-Sensitive Chemistry Automation

| Item | Function & Importance in Automation |

|---|---|

| Teflon Taps | Provide a grease-free, inert seal for Schlenk line stopcocks, reducing contamination and maintenance [20]. |

| Rubber Septa | Create a resealable, gas-tight port on flasks for syringe and cannula manipulations under inert atmosphere [23]. |

| High-Vacuum Grease | Ensures an airtight seal on ground glass joints under dynamic vacuum; inadequate greasing can cause leaks or seizure [20]. |

| Cannulae (Stainless Steel/Glass) | Enable safe transfer of liquids and suspensions between vessels within an inert atmosphere manifold [20]. |

| Inert Gas (Nâ‚‚/Ar) | Provides the oxygen- and moisture-free environment. Argon is denser than air, offering better blanket protection [23]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen Traps | Placed between the vacuum line and pump to condense volatile solvents and moisture, protecting the pump from damage and preventing backstreaming [20]. |

| HEPA-Filtered Dryer | Integrated into advanced glassware washers to ensure glassware is dried with particle-free air, ready for sensitive applications [21]. |

| Anti-inflammatory agent 6 | Anti-inflammatory Agent 6|NF-κB Inhibitor|476.39 g/mol |

| TCO-PEG3-amide-C3-triethoxysilane | TCO-PEG3-amide-C3-triethoxysilane, MF:C27H52N2O9Si, MW:576.8 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common sources of error in automated liquid handling? The most common errors stem from pipetting techniques, tip selection and quality, contamination, and incorrect method parameters in the software. Using the wrong pipetting mode (forward vs. reverse) for a specific liquid type, or employing low-quality tips that do not fit properly, can significantly compromise accuracy and precision. [24] [25]

Q2: How can I prevent contamination during automated runs? Contamination can be prevented by using disposable tips to eliminate carryover, adding a trailing air gap after aspiration to prevent droplets from falling, and carefully planning the deck layout to avoid ejecting tips over critical labware. For fixed-tip systems, rigorous validation of tip-washing protocols is essential. [26] [24] [25]

Q3: Why are my serial dilution results inconsistent? Inconsistent serial dilutions are often due to inefficient mixing. If the reagent in the well is not homogenized before the next transfer, the concentration will not be as theoretically assumed, skewing all subsequent results. Ensure your method includes adequate mixing steps, such as aspirate/dispense cycles or on-deck shaking, before each transfer. [24] [25]

Q4: How often should I calibrate my liquid handler? While vendors typically perform qualification (IQ/OQ/PQ) during installation and may offer annual or semi-annual service, this is often insufficient. For high-frequency use, laboratories should implement a regular, standardized volume verification check to quickly identify performance drift. Relying on only one or two checks per year when you may run over 150 experiments creates significant risk. [27]

Q5: What is the economic impact of liquid handling inaccuracy? The impact is substantial. In a high-throughput screening lab, over-dispensing expensive reagents by just 20% could lead to over $750,000 in additional annual costs and risk depleting rare compounds. Under-dispensing can cause false negatives, potentially causing a company to miss the next blockbuster drug and billions in future revenue. [24] [25]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Volume Dispensing

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent over- or under-dispensing across all channels. | Incorrect liquid class or pipetting mode selected. [24] [25] | Use forward mode for aqueous solutions; use reverse mode for viscous or foaming liquids. [24] [25] |

| Low precision (high variation) between dispenses. | Poor quality or non-vendor-approved pipette tips. [24] [25] | Use vendor-approved tips to ensure proper fit, material, and wettability. [26] [24] |

| Drift in accuracy over time without method changes. | Lack of regular calibration and performance verification. [27] | Implement a frequent calibration schedule using a standardized, traceable method. [24] [25] |

Problem: Cross-Contamination Between Samples

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Carryover of reagents between samples in a run. | Ineffective washing of fixed tips. [24] [25] | Validate and optimize tip wash station protocols to ensure complete residue removal. [24] |

| Contamination on the deck or labware. | Droplets falling from tips during movement. [24] [25] | Program a "trailing air gap" to follow reagent aspiration. [24] [25] |

| Splatter when tips are ejected. [24] | Adjust method to eject tips into a waste container that is not over other critical labware. [24] |

Problem: Failed Serial Dilution Assays

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear or unpredictable dose-response curves. | Inefficient mixing after each dilution step. [24] [25] | Incorporate mixing steps (e.g., repeated aspirate/dispense cycles or on-deck shaking) after each reagent addition. [24] |

| Inconsistent volumes in sequential dispensing. | "First and last dispense" error from a large aspirated volume. [24] [25] | Validate that the same volume is dispensed in each well; consider breaking into separate aspirations. [24] |

Problem: System Errors and Hardware Failures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid sensing errors; failure to aspirate. | Tips lowered into bubbly or frothy liquid, causing false sensing. [24] [25] | Adjust the method to aspirate from a calmer part of the reservoir or use a different liquid detection setting. |

| Clogged probes or tips. | Precipitates in reagents or dispensing into dry wells. [26] | Implement tip cleaning routines or use disposable tips. For dry dispenses, ensure the dispensing height is correct to avoid splashing. |

| Robotic arm movement is jerky or inaccurate. | Mechanical wear of bearings, belts, or servo motors. [28] | Perform regular preventive maintenance as per the vendor's schedule. Check for unusual vibrations. [28] |

Experimental Protocol: Volume Transfer Verification

Objective: To regularly verify the accuracy and precision of an automated liquid handler's volume delivery.

Methodology (Gravimetric):

- Preparation: Tare a high-precision microbalance. Place a small weighing vessel on the balance.

- Environmental Recording: Record the temperature and relative humidity of the lab.

- System Setup: Program the liquid handler to dispense a target volume of pure water (density ~1 g/µL at 20°C) into the weighing vessel. Ensure the liquid class settings (aspirate/dispense speed, delay, etc.) are correct.

- Dispensing: Run the method. For each dispense, record the weight. Repeat for at least n=10 replicates per channel or volume being tested.

- Calculation:

- Actual Volume (µL) = Mass (mg) / Water Density (mg/µL) (correct for temperature).

- Calculate the Accuracy as (Mean Actual Volume / Target Volume) x 100%.

- Calculate the Precision as the Coefficient of Variation (%CV) of the actual volumes.

- Analysis: Compare the calculated accuracy and precision against the manufacturer's specifications and your laboratory's required tolerances for the assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Vendor-Approved Pipette Tips | Ensure optimal fit and performance. Special low-volume tips are validated for reliable microliter/sub-microliter dispensing. [26] [24] |

| Sterile, Filter Tips | For applications requiring sterility or when working with radioactive/biohazardous materials, they prevent aerosol contamination and protect the instrument. [26] |

| Liquid Displacement Needles | Fixed, washable steel needles ideal for piercing septa, handling viscous liquids, and multi-dispensing small volumes below 5 µL. [26] |

| Optimal Liquid Class | A software-defined set of parameters (speeds, delays, etc.) tailored to the physical properties (viscosity, surface tension) of a specific reagent. [24] [25] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Traceable standards used for calibrating liquid handlers and validating that they dispense the correct volumes. [24] |

| Purpurin 18 methyl ester | Purpurin 18 methyl ester, MF:C34H34N4O5, MW:578.7 g/mol |

| pGlu-Pro-Arg-MNA monoacetate | pGlu-Pro-Arg-MNA monoacetate, MF:C25H36N8O9, MW:592.6 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Logic and Resolution Pathway

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common liquid handling issues.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common XDL Programming Issues

This guide addresses specific issues users might encounter when programming automated synthesis platforms with the Chemical Description Language (XDL) for air-sensitive chemistry.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common XDL Execution Errors

| Error Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

HardwareNotFound or ComponentUnavailable during compilation |

Hardware graph does not match physical platform configuration; incorrect device names or connections. | Verify the hardware graph (procedure_graph.json) accurately reflects the system setup, including all Schlenk line taps, reactors, and liquid handlers. Use the platform's introspection tools to confirm device availability. |

[29] [30] |

StepExecutionTimeout or procedure hangs |

A hardware operation (e.g., EvacuateAndRefill, liquid transfer) did not complete within the expected time. |

Check for physical blockages, ensure Schlenk line vacuum pressure is sufficient (<0.1 mbar), and verify sensor feedback. Implement dynamic steps with timeout handling to manage non-ideal conditions. | [31] [32] |

CompilationError with reaction blueprints |

Syntax error in XDL file; missing required parameters for a blueprint; type mismatch. | Validate XDL syntax against the standard. Ensure all Reagents and Parameters required by the blueprint (e.g., molecular weight, density, stoichiometry) are correctly defined. |

[33] [30] |

| Uncontrolled exotherm or reaction failure | Lack of real-time feedback for highly exothermic reactions; fixed addition rates unsuitable for scale-up. | Integrate a DynamicStep that uses an in-situ temperature probe to control reagent addition rate, pausing the addition if a temperature threshold is exceeded. |

[31] |

| Failed transfer of air-sensitive liquids | Inadequate inertization of vessels or transfer lines; leak in the system. | Ensure the EvacuateAndRefill cycle is performed correctly (e.g., 3 min vacuum, 2 min gas, 3 repeats). Use a liquid sensor or vision system to confirm transfers and detect failures. |

[32] |

| Inconsistent results between manual and automated runs | Ambient conditions (temperature, humidity) affecting reaction; subtle differences in timing. | Use the environmental sensor to record ambient conditions. Employ the Monitor step to use inline analytics (e.g., Raman, NMR) for endpoint detection instead of fixed times. |

[31] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is XDL and how does it enhance reproducibility in air-sensitive chemistry? XDL (Chemical Description Language) is a universal, high-level programming language for encoding chemical synthesis procedures in a hardware-independent, human- and machine-readable format [29] [30]. For air-sensitive chemistry, it allows the precise digital capture of complex inert-atmosphere protocols—including Schlenk line operations, evacuation-and-refill cycles, and handling of pyrophoric reagents—as executable code. This eliminates ambiguity and manual technique variations, ensuring that every reproduced procedure follows the exact same sequence of operations, thereby significantly enhancing reproducibility [32].

Q2: How can I implement real-time feedback control for safety in my XDL procedure?

XDL supports DynamicSteps that can react to sensor data in real-time. You can implement feedback control by using steps that monitor sensor input. For example, to safely handle an exothermic reaction or quench alkali metals, you can define a DynamicStep that reads from an in-situ temperature probe. The step's logic can be programmed to pause reagent addition or initiate a cooling sequence if the temperature exceeds a predefined safety threshold, preventing thermal runaway [31] [32].

Q3: What are "Reaction Blueprints" and how do they help in synthesizing a library of compounds? Reaction Blueprints are the chemical analog to functions in computer science. They allow you to define a general, multi-step synthesis protocol (e.g., for a class of organocatalysts) where the specific reagents and parameters (e.g., concentrations, temperatures) are treated as inputs [33]. This means you can write a single, validated blueprint and then reuse it to synthesize different members of a compound library simply by providing different input reagents (e.g., different aryl halides) and parameters. This promotes code reuse, reduces redundancy, and standardizes synthetic workflows across a research group [33].

Q4: Which analytical techniques can be integrated for closed-loop optimization and how?

The AnalyticalLabware Python package enables integration with various inline analytical instruments for closed-loop optimization [31]. Supported techniques include:

- HPLC-DAD: For quantifying yield and purity.

- NMR Spectroscopy: For structural confirmation and reaction monitoring.

- Raman Spectroscopy: For tracking reaction progress in real-time.

- UV-Vis/NIR Spectroscopy: For concentration measurement and endpoint detection.

The workflow involves adding an

Analysestep in your XDL. The collected spectral data is processed, and the result (e.g., yield) is fed to an optimization algorithm (e.g., from the Summit or Olympus frameworks), which then suggests and updates the reaction parameters for the next automated iteration [31].

Q5: Our lab has both batch and flow chemistry modules. Can XDL control hybrid systems?

Yes, a core principle of XDL is hardware abstraction [29] [34]. The same XDL procedure can be compiled to run on different platforms, provided the target platform's hardware graph defines the available components (e.g., a batch reactor or a continuous flow reactor). The XDL interpreter handles the translation of abstract steps (like Add, Heat, Stir) into the platform-specific commands, making it suitable for hybrid or reconfigurable systems [31] [34].

Experimental Protocol: Automated Synthesis of an Air-Sensitive Organometallic Complex

The following methodology details a validated automated synthesis on the Schlenkputer platform, capable of handling compounds sensitive to oxygen and water at sub-ppm levels [32].

1. Objective: To autonomously synthesize and isolate {DippNacNacMgI}2 (a highly air-sensitive compound) using XDL-controlled Schlenk hardware.

2. Required Reagents and Materials:

- Precursor: DippNacNacH ligand.

- Reagent: Alkyl iodide or alkali metal (e.g., for metalation).

- Solvents: Dry, deoxygenated hydrocarbon and ether solvents (e.g., toluene, diethyl ether).

- Inert Gas: High-purity argon or nitrogen gas.

3. Essential Hardware Setup (The Schlenkputer):

- Programmable Schlenk Line: Automated vacuum taps capable of achieving ≤ 1.5 x 10â»Â³ mbar [32].

- Automated Liquid Handling (Chemputer backbone): For precise reagent delivery.

- Specialized Glassware: Remotely operable Schlenk flasks with automated taps for isolation and filtration.

- In-line NMR probe or UV-Vis spectrometer: For reaction monitoring and analysis.

- In-situ Temperature Probe: For safety monitoring and feedback.

4. XDL Procedure Workflow: The automated sequence is encoded in an XDL file and can be visualized as the following workflow:

5. Key Technical Considerations for Air-Sensitive Synthesis:

- Inertization: The

EvacuateAndRefillstep is critical. The standard is three cycles of vacuum (3 min) and inert gas refill (2 min) to achieve sub-ppm Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O levels [32]. - Safety Feedback: The addition of the metal reagent is controlled by a

DynamicStepthat uses the temperature probe to pause addition if an exotherm is detected, preventing thermal runaway [32]. - Endpoint Detection: Instead of a fixed reaction time, the procedure uses a

Monitorstep with in-line NMR to determine completion, ensuring consistency [31] [32]. - Solid Handling: The product is transferred under inert atmosphere to the automated filtration flask. The solid is isolated by removing solvent in vacuo, all within the sealed system, allowing for retrieval from a glovebox [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Automated Air-Sensitive Chemistry

| Item | Function in the Context of Automation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Rotaflo or J. Young Taps | Remotely operable glassware taps controlled by linear actuators for Schlenk line and flasks. | Enable full software control over the inert atmosphere, replacing manual manipulation. Essential for dynamic evacuation and refill cycles. [32] |

| Perfluoroelastomer O-Rings | Seals for automated Schlenk glassware and taps. | Provide excellent chemical resistance and minimal swelling upon solvent exposure, ensuring long-term gas-tight integrity for sensitive reagents. [32] |

| In-situ Raman Probe | For real-time, non-destructive reaction monitoring directly in the reactor. | Integrated via the AnalyticalLabware package. Provides data for endpoint detection and quantitative analysis for closed-loop optimization. [31] |

| Color/Turbidity Sensor | Low-cost sensor for monitoring reaction progress or physical state changes. | Can detect endpoints based on discoloration (e.g., in nitrile synthesis) or increased turbidity during crystallization, triggering the next step dynamically. [31] |

| Modular Solvent Dispensing System | Integrated solvent reservoirs connected to the liquid handling system. | Provides a continuous supply of dry, deoxygenated solvents, which is crucial for the success of multi-step, unattended air-sensitive syntheses. [32] |

| 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloroaniline-d3 | 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloroaniline-d3, CAS:1219806-05-9, MF:C6H3Cl4N, MW:233.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist 2 | Vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist 2, MF:C62H91FN16O11, MW:1255.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with automated laboratory equipment is revolutionizing chemical research. These "self-driving laboratories" perform iterative, closed-loop experiments to discover and optimize reactions with minimal human intervention [35] [36]. For researchers working with air-sensitive chemistry, these systems present unique challenges and opportunities. This guide serves as a technical support center, providing troubleshooting and detailed protocols for implementing these advanced workflows within a controlled, inert atmosphere.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common technical issues encountered when running autonomous workflows for air-sensitive chemistry.

FAQ 1: My autonomous platform is suggesting experimental conditions that lead to decomposition or poor yield. How can I improve the quality of its suggestions?

- Problem: The AI algorithm is exploring regions of the experimental parameter space that are non-productive or lead to failed reactions.

- Solution:

- Review Parameter Bounds: Check the defined ranges for parameters like temperature, concentration, and catalyst loading. Impose stricter bounds based on prior chemical knowledge to prevent the algorithm from exploring impractical conditions [37].

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use transfer learning strategies. Fine-tune the AI model on a small, high-quality dataset of relevant, known successful reactions before starting the autonomous optimization. This seeds the algorithm with better initial intuition [37].

- Inspect the Acquisition Function: The acquisition function (e.g., in Bayesian optimization) balances exploration vs. exploitation. If it is over-prioritizing exploration, adjust its parameters to focus more on optimizing areas near known successful conditions.

FAQ 2: I am observing inconsistent results and catalyst deactivation during a long-term autonomous run. What could be causing this?

- Problem: The system's performance is degrading over time, compromising data integrity.

- Solution:

- Check Air-Sensitive Integrity: Verify the integrity of your inert atmosphere (e.g., glovebox, Schlenk line). Use a oxygen/moisture probe to confirm that levels remain below the acceptable threshold (typically <1 ppm) throughout the entire experiment [3].

- Inspect for Catalyst Poisoning: In heterogeneous catalytic systems, check for catalyst leaching or fouling from the reactor's 3D-printed structure itself. Analyze the reactor's material compatibility with your catalyst and solvents [36].

- Validate Automated Sampling: Ensure that the automated liquid handling system for sample preparation is not introducing oxygen or moisture during reagent transfers. Check for leaks in tubing, valves, or seals in the flow chemistry system [35].

FAQ 3: The real-time analytical data (e.g., from NMR) used for feedback is noisy, causing the AI model to make poor decisions. How can this be resolved?

- Problem: Unreliable or noisy data from inline analyzers leads to incorrect performance calculations and misguided subsequent experiments.

- Solution:

- Increase Acquisition Time/Average Scans: For techniques like benchtop NMR, increase the signal averaging to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, even if it slightly slows the analytical loop [36].

- Implement Data Pre-processing: Introduce real-time data smoothing or filtering algorithms (e.g., Savitzky-Golay filter) in the software pipeline before the data is passed to the AI model.

- Calibrate Analytical Equipment: Perform regular calibration of the inline analyzer with standard samples to ensure accuracy. For UV-Vis, ensure the flow cell is clean and free of air bubbles.

FAQ 4: The closed-loop workflow is taking too long per cycle, limiting the number of experiments we can run. What are the potential bottlenecks?

- Problem: The experiment cycle time is slow, reducing the overall throughput of the self-driving laboratory.

- Solution:

- Analyze Cycle Timeline: Break down the workflow into steps: reagent preparation, reaction execution, analysis, and AI decision time. Identify the slowest step.

- Parallelize Experiments: If possible, design the platform to run multiple reactions in parallel, a key feature of advanced self-driving labs [36].

- Optimize Reaction Time: For flow chemistry systems, consider increasing the flow rate to reduce residence time, provided it does not adversely impact conversion or selectivity.

- Review AI Optimization: Consider using a faster, less computationally expensive surrogate model during the active learning cycle.

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

The following are detailed methodologies for establishing core autonomous workflows, with special considerations for air-sensitive chemistry.

Protocol 1: Autonomous Electrochemical Mechanistic Investigation

This protocol is adapted from a study on the mechanistic investigation of molecular electrochemistry using a closed-loop platform [35].

1. Objective: To autonomously identify the presence of an EC (Electrochemical-Chemical) mechanism and extract kinetic parameters for the chemical (C) step.

2. Experimental Setup & Reagents:

- Platform Modules: Integrated system with (a) flow chemistry for automated electrolyte formulation, (b) potentiostat with automated iR compensation, (c) DL-based voltammogram analysis model, and (d) Bayesian optimization algorithm for decision-making [35].

- Core Reactor: Standard single-compartment, three-electrode electrochemical cell inside a glovebox ( [35], [3]).

- Key Reagents:

- Analyte: Cobalt tetraphenylporphyrin (CoTPP), 1 mM in DMF.

- Electrophile Library: Various organohalides (RX) like 1-bromobutane.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (NBu₄PF₆) in DMF.

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen or Argon gas supply for glovebox, maintained at <1 ppm Oâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚O [3].

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- System Initialization: Purge the glovebox and flow chemistry lines with inert gas. Confirm atmospheric purity.

- Parameter Space Definition: Define the ranges for scan rate (ν, e.g., 0.01-0.2 V/s) and electrophile concentration ([RX], e.g., 0-20 mM).

- Autonomous Loop Execution:

- Design: The Bayesian optimization algorithm suggests a new combination of ν and [RX].

- Formulate & Execute: The flow system prepares the electrolyte with the specified [RX]. The potentiostat runs a set of six cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans at different ν.

- Analyze: The deep learning (DL) model analyzes the CV set and outputs a numerical propensity (probability) for the EC mechanism versus other pathways [35].

- Decide: Based on the DL output, the algorithm evaluates if the objective (e.g., high confidence in EC mechanism) is met. If not, it designs a new experiment to probe the mechanism more effectively or to precisely map the kinetics.

- Kinetic Extraction: Once an EC mechanism is confirmed, the system focuses on finding optimal (ν, [RX]) pairs to accurately determine the second-order rate constant (k₀) for the C step.

4. Key Data & Output:

The primary output is the kinetic rate constant kâ‚€. The table below summarizes example data for different electrophiles from an autonomous run.

Table 1: Exemplar Kinetic Data from Autonomous EC Mechanism Investigation

| Organohalide Electrophile (RX) | Propensity for EC Mechanism | Extracted Rate Constant, kâ‚€ (Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Bromobutane | 0.95 | 1.5 x 10² |

| Benzyl Chloride | 0.89 | 2.1 x 10âµ |

| Iodomethane | 0.91 | 5.8 x 10ⶠ|

| (Negative Control) | <0.10 | Not Applicable |

Protocol 2: AI-Driven Optimization of a 3D-Printed Catalytic Reactor

This protocol is based on the Reac-Discovery platform for continuous-flow catalytic reactor discovery and optimization [36].

1. Objective: To autonomously design, fabricate, and optimize the performance of a 3D-printed catalytic reactor for a multiphase reaction.

2. Experimental Setup & Reagents:

- Platform Modules: (a) Reac-Gen: parametric design software for Periodic Open-Cell Structures (POCS), (b) Reac-Fab: high-resolution 3D printing and functionalization, (c) Reac-Eval: self-driving lab with parallel reactors and real-time NMR monitoring [36].

- Key Reagents:

- Reaction-specific chemicals: e.g., Acetophenone and Hâ‚‚ gas for hydrogenation; Epoxide and COâ‚‚ for cycloaddition.

- Immobilized Catalyst: e.g., Metal nanoparticles on a solid support, packed or coated within the 3D-printed reactor.

- Solvents: Anhydrous, degassed solvents (e.g., THF, MeCN).

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Reactor Design (Reac-Gen): The algorithm generates a set of reactor geometries (POCS like Gyroids) by varying parameters: Size (S), Level Threshold (L), and Resolution (R) [36].

- Printability Check & Fabrication (Reac-Fab): An ML model validates the generated designs for printability. Validated designs are 3D-printed via stereolithography.

- Catalyst Functionalization: The printed reactors are functionalized with the immobilized catalyst, typically via coating or packing in a controlled atmosphere.

- Autonomous Evaluation & Optimization (Reac-Eval):

- The fabricated reactors are installed in the parallel testing rig.

- The SDL varies process descriptors (temperature, gas/liquid flow rates, concentration).

- Real-time NMR monitors reaction conversion and yield.

- Two ML models are trained: one optimizes process conditions, and the other refines the reactor geometry for the next iteration, creating a closed loop between design and performance [36].

4. Key Data & Output: The primary output is the Space-Time Yield (STY). The system co-optimizes geometry and process parameters.

Table 2: Exemplar Optimization Parameters and Performance Output for a COâ‚‚ Cycloaddition Reaction

| Optimization Parameter | Parameter Type | Role in Reaction Performance | Optimized Value (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gyroid Level Threshold (L) | Geometric | Controls porosity & wall thickness; impacts surface area and mass transfer. | 0.75 |

| Temperature | Process | Governs reaction kinetics; must be balanced against catalyst stability. | 100 °C |

| Gas Flow Rate | Process | Determines reactant availability and residence time in gas-liquid-solid systems. | 5 mL/min |

| Liquid Flow Rate | Process | Controls liquid residence time and mixing. | 0.2 mL/min |

| Resulting Space-Time Yield | Performance Metric | Mass of product produced per unit reactor volume per unit time. Key metric for reactor efficiency. | 950 g Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details critical items for setting up autonomous workflows for air-sensitive chemistry.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Autonomous Air-Sensitive Chemistry Workflows

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Schlenk Line or Glovebox | Provides an inert atmosphere (Nâ‚‚/Ar) for handling sensitive compounds and setting up reactions; foundational for preventing catalyst decomposition and side reactions [3]. |

| Anhydrous, Degassed Solvents | Essential for preventing quenching of reactive intermediates and maintaining catalyst activity; typically dried over molecular sieves and sparged with inert gas. |

| Air-Free Syringes & Cannulae | Enable the safe and precise transfer of liquids and solutions between sealed vessels without exposure to air [3]. |

| 3D Printer (SLA/DLP) | For fabricating custom reactor geometries with complex internal structures (POCS) that enhance mass/heat transfer in continuous flow systems [36]. |

| In-line NMR Spectrometer | Provides real-time, non-destructive reaction monitoring, supplying the crucial data stream on conversion/yield for the AI's feedback loop [36]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | The core AI engine (e.g., Dragonfly) that designs sequential experiments by modeling the parameter space and maximizing a performance objective [35]. |

| Deep Learning Model (e.g., ResNet) | Used for advanced data analysis, such as classifying electrochemical mechanisms from subtle features in voltammograms, translating raw data into actionable insights [35]. |

| GABA receptor Antagonist 1 | GABA receptor Antagonist 1, MF:C21H17Cl2F6N3O3S, MW:576.3 g/mol |

| Antimicrobial agent-29 | Antimicrobial agent-29, MF:C19H14N4O4S, MW:394.4 g/mol |

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core closed-loop feedback process that is fundamental to autonomous experimentation.

Closed-Loop Autonomous Experimentation

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Catalyst Degradation and Loss of Activity

- Problem Description: The homogeneous catalyst, particularly a transition metal complex like a palladium or ruthenium catalyst, shows significantly reduced activity or complete deactivation during the automated synthesis process [38].

- Possible Causes:

- Solutions:

- Preventive Handling: Store and handle all air-sensitive catalysts in an inert atmosphere using a glovebox (e.g., MIKROUNA Glovebox) or nitrogen cabinet (e.g., CATEC nitrogen cabinet) [39].

- System Purging: Implement and validate an inert gas purging system (using nitrogen or argon) for the automated synthesizer to maintain an inert environment throughout the synthesis cycle [38].

- Equipment Selection: Use chemically inert reactors, such as glass-lined reactors, to minimize interaction between the catalyst and reactor surfaces [38].

Issue 2: Reactor Clogging in Continuous-Flow Systems

- Problem Description: Solid particulates, often from by-products or precipitated intermediates, obstruct the flow path in a continuous-flow microreactor or a packed-bed reactor, leading to increased pressure and process failure [40].

- Possible Causes:

- Solutions:

- In-line Filtration: Integrate in-line filters or cross-flow filtration modules ahead of critical reactors and narrow flow paths.

- Solvent Compatibility Scouting: During reaction development, perform solubility studies for intermediates in the solvents used in subsequent steps to avoid precipitation [40].

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Use PAT tools to monitor pressure drops across the reactor in real-time, allowing for early detection and intervention before complete clogging occurs.

Issue 3: Isomerization of PNP Ligands to PPN Form

- Problem Description: Diphosphinoamine (PNP) ligands, crucial for certain catalytic reactions like ethylene tetramerization, isomerize to their iminobisphosphine (PPN) form under reaction conditions. This leads to decreased catalytic performance and increased formation of undesirable polyethylene by-products [41].

- Possible Causes:

- Solutions:

- Computational Pre-Screening: Before synthesis, use an automated computational workflow (e.g., XTBDFT) to calculate the thermodynamic stability of the PNP ligand against isomerization (ΔGPPN). Ligands with a more negative ΔGPPN are more stable and less likely to isomerize [41].

- Ligand Selection: Select PNP ligand candidates based on computational screening to rule out those with non-trivial synthetic routes and poor expected stability, saving significant experimental time and resources [41].

Issue 4: Inconsistent Yield and Impurity Profile in Automated Multistep Synthesis

- Problem Description: Batch-to-batch variability in yield and impurity profile is observed during a multistep automated synthesis, such as the synthesis of Prexasertib [40] [42].

- Possible Causes:

- Solutions:

- Solid-Phase Synthesis (SPS-Flow): Adopt a solid-phase synthesis approach in a continuous flow. The target molecule grows on a solid resin, and all purifications are done by simple filtration before the final compound is cleaved, effectively eliminating solvent and reagent incompatibility issues [40].

- Protective Group Strategy: Re-evaluate the protective group used. For example, in the synthesis of MK-0941, selecting a proper protective group for a key O-alkylation step was critical to improving the synthesis [42].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Use HTS to rapidly identify optimal catalysts and reaction conditions for each step, ensuring high conversion and selectivity before automating the full process [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of automated SPS-flow synthesis over traditional batch methods for APIs?

Automated Solid-Phase Synthesis in flow (SPS-flow) offers several key advantages [40]:

- Avoids Incompatibility: It overcomes solvent and reagent incompatibility between synthetic steps by anchoring the growing molecule to a solid resin, with simple filtrations between steps.

- Enables Long Sequences: Facilitates automation of multistep synthesis with longer steps (e.g., a demonstrated 6-step synthesis of Prexasertib).

- Wider Reagent Compatibility: Tolerates a much wider range of reagents, including pyrophoric ones like LDA.

- Compact and Reusable: The synthesizer is compact and can be reused for different targets without system reconstruction.

Q2: How can computational methods accelerate catalyst and ligand development?

Computational methods can dramatically speed up development [41]:

- Automated Conformer Analysis: Tools like XTBDFT automate the identification of the global minimum energy structure for conformationally complex molecules (like ligands), which is crucial for accurate thermodynamic calculations.

- Predictive Thermodynamics: They can calculate key properties, such as the thermodynamic stability of a ligand against isomerization (ΔG_PPN), which has shown a strong inverse correlation with experimental catalyst performance (e.g., polyethylene formation).

- Virtual Screening: Researchers can computationally screen novel candidate ligands, ruling out those with poor expected performance before investing time and resources in their complex synthesis.

Q3: What equipment is essential for handling air-sensitive catalysts in an automated workflow?

Essential equipment for handling air-sensitive catalysts includes [39] [38]:

- Inert Atmosphere Chambers: A glovebox (e.g., MIKROUNA) or nitrogen cabinet (e.g., CATEC) for catalyst storage, weighing, and loading into the system.

- Inert Reactors: Glass-lined reactors that provide a chemically inert environment to prevent catalyst deactivation.

- Sealed Conveying Systems: Automated bulk material handling and conveying systems designed to mitigate risks of degradation and contamination.

- Inert Gas Purging: Integrated inert gas (Nâ‚‚, Ar) purging systems for the entire automated synthesizer to maintain an oxygen- and moisture-free environment.

Q4: What are the typical turnaround times for high-throughput catalyst screening services?

High-throughput catalyst screening services can provide results very rapidly [39]:

- Standard Service: Delivers screening results within a 72-hour turnaround time.

- VIP/Expedited Service: Offers results in as little as 48 hours.

| Metric | Performance Data |

|---|---|

| API Synthesized | Prexasertib (Trifluoroacetic Acid Salt) |

| Number of Steps | 6 steps |

| System Type | Automated SPS-Flow |

| Execution Time | 32 hours (continuous-flow cyclic execution) |

| Resin Used | 2 grams of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin |

| Isolated Yield | 65% |

| Derivative Library Size | 23 prexasertib derivatives |

| Service Phase | Activity Description | Standard Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Design & Setup | Define parameters and select screening matrix. | Within 12 hours |

| Screening Execution | Conduct parallel experiments under controlled conditions. | Within 24 hours |

| Analysis & Data Compilation | Analyze conversion, selectivity, and yields. | Within 48-72 hours |

| Total Standard Turnaround | 72 hours | |

| Total VIP Turnaround | 48 hours |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To execute a fully automated, multistep synthesis of the active pharmaceutical ingredient Prexasertib and its derivatives using solid-phase synthesis in a continuous flow.

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: A single column reactor is filled with 2.0 grams of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin.

- Computer Recipe File (CRF): The synthesis is controlled by a computer-based chemical recipe file (CRF) developed through prior batch studies.

- Cyclic Execution: The automated system executes the following steps cyclically for 32 hours:

- Coupling: Reagents and activated amino acids or building blocks are delivered to the solid-phase resin.

- Washing: Solvents are pumped through the column to remove excess reagents and by-products.

- Deprotection: Specific reagents are introduced to remove protective groups from intermediates.

- Filtration: After each step, the resin is washed, and solutions are filtered away, purifying the bound intermediate.

- Cleavage: After the final synthetic step, a cleavage cocktail is introduced to release the finished Prexasertib molecule from the solid resin.

- Precipitation & Isolation: The product is precipitated and isolated as a trifluoroacetic acid salt.

Objective: To automatically identify the lowest-energy conformer of PNP and PPN isomers and calculate the Gibbs free energy of isomerization (ΔG_PPN) to predict ligand stability and catalyst performance.

Methodology:

- Initial Geometry Generation: Generate an initial 3D molecular structure (

.xyzfile) using a molecular editor like MolView. - Conformer Sampling with CREST: Use the CREST software, driven by the GFN2-xTB semi-empirical method, to perform a meta-dynamics search. This generates a broad ensemble of conformers within a specified energy window (e.g., 6 kcal/mol).

- Conformer Refinement with DFT: Re-optimize the geometry of the lowest-energy conformers from Step 2 using Density Functional Theory (DFT) in NWChem with a B3LYP functional and a def2-SV(P) basis set.

- High-Level Single-Point Energy Calculation: Perform a more accurate single-point energy evaluation on the refined DFT-optimized structure using a larger basis set (def2-TZVP).

- Thermochemical Correction: Apply a quasi-harmonic correction to low-frequency vibrational modes (below 100 cmâ»Â¹) using the GoodVibes script to obtain an accurate Gibbs free energy (G).

- Calculate ΔGPPN: The thermodynamic stability is calculated as: ΔGPPN = GPPN - GPNP. A more negative ΔG_PPN indicates a PNP ligand that is more stable against isomerization.

Workflow Diagrams