Bayesian Optimization in Chemical Synthesis: Accelerating Drug Discovery with AI

This article explores the transformative role of Bayesian Optimization (BO) in efficiently identifying optimal chemical reaction conditions, a critical and resource-intensive challenge in pharmaceutical development.

Bayesian Optimization in Chemical Synthesis: Accelerating Drug Discovery with AI

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Bayesian Optimization (BO) in efficiently identifying optimal chemical reaction conditions, a critical and resource-intensive challenge in pharmaceutical development. It covers the foundational principles of BO, including Gaussian Process surrogate models and acquisition functions that balance exploration and exploitation. The scope extends to practical methodologies and applications in high-throughput experimentation (HTE), troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validating performance against traditional approaches. Through case studies and comparative analysis, we demonstrate how BO enables rapid optimization of complex reactions, such as Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, significantly shortening process development timelines for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and paving the way for autonomous laboratories.

What is Bayesian Optimization? Core Principles Transforming Chemical Reaction Screening

The Challenge of Chemical Reaction Optimization in Pharmaceutical Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Bayesian Optimization in Action

This guide addresses common challenges scientists face when implementing Bayesian Optimization (BO) for chemical reaction optimization in pharmaceutical development.

FAQ 1: My Bayesian optimization algorithm suggests experiments that seem theoretically impossible to improve yield. Why does this happen, and how can I prevent it?

- Problem: Standard BO algorithms can sometimes suggest experimental conditions that are "futile" – meaning that even with a 100% yield, they could not improve the current best objective value, especially when optimizing complex functions like throughput.

- Solution: Implement an Adaptive Boundary Constraint (ABC-BO) strategy. This method incorporates knowledge of the objective function into the BO process. It dynamically identifies and excludes futile experimental conditions as the optimization progresses, allowing the algorithm to focus only on the most promising regions of the search space. This has been shown to prevent up to 50% of futile experiments in complex optimizations involving multiple categorical, continuous, and discrete variables [1].

- Recommended Action: Review your objective function and integrate a check that assesses whether a suggested condition has the theoretical potential to surpass the current best value before running the experiment.

FAQ 2: How can I effectively explore a vast condition space with many categorical variables (like ligands and solvents) without exhaustive screening?

- Problem: The high dimensionality of reaction condition spaces, particularly with categorical variables, makes exhaustive screening intractable, even with High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE).

- Solution: Use a scalable BO framework (e.g., Minerva) designed for large parallel batches and high-dimensional spaces. The workflow should start with algorithmic quasi-random sampling (e.g., Sobol sampling) to diversify initial space coverage. Subsequently, an acquisition function guided by a surrogate model (like a Gaussian Process) balances the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of known promising conditions [2].

- Recommended Action: Frame your reaction space as a discrete combinatorial set of plausible conditions, automatically filtering out impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points). This allows the BO algorithm to efficiently navigate spaces with tens of thousands of potential conditions [2].

FAQ 3: My experimental results are noisy. Is Bayesian optimization still suitable?

- Problem: Chemical reaction data often contains inherent noise and variability, which can derail optimization algorithms.

- Solution: Yes, BO is suitable. Its probabilistic nature, through surrogate models like Gaussian Processes, inherently handles uncertainty. The algorithm uses prediction uncertainty to guide experimentation, making it robust to noisy data. Furthermore, noise-robust methods and multi-task learning are emerging techniques that enhance BO's versatility in such scenarios [2] [3].

- Recommended Action: Ensure your BO implementation uses a surrogate model and acquisition functions that explicitly account for noise. Techniques such as Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) are designed for such environments [2] [3].

FAQ 4: Bayesian optimization feels like a "black box." How can I understand why it suggests certain conditions?

- Problem: The decision-making process of sophisticated BO models can be opaque, making it difficult for chemists to trust, validate, or align suggestions with their expertise.

- Solution: Consider alternative, more interpretable optimization frameworks. Swarm Intelligence approaches, such as the α-PSO algorithm, offer a solution. α-PSO uses mechanistically clear, physics-inspired swarm dynamics where the movement of "particles" (representing experiments) is guided by simple rules based on personal best, swarm best, and a machine learning term. This provides a transparent view of the factors driving each optimization decision [4].

- Recommended Action: For critical projects where interpretability is key, explore hybrid metaheuristic algorithms like α-PSO, which have demonstrated performance competitive with state-of-the-art BO while maintaining methodological clarity [4].

Performance Data: Bayesian Optimization in Pharmaceutical Research

The table below summarizes quantitative data from real-world applications of Bayesian optimization in pharmaceutical development.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Bayesian Optimization in Pharmaceutical Reaction Optimization

| Application Context | Optimization Target | Key Performance Outcome | Experimental Efficiency | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-catalyzed Suzuki & Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig API syntheses | Yield & Selectivity | Identified multiple conditions achieving >95% area percent yield and selectivity | Led to improved process conditions at scale in 4 weeks vs. a previous 6-month campaign [2] | |

| General catalytic reaction optimization | Finding optimal conditions | Found optimal conditions in 4 rounds of 10 experiments from a pool of 180,000 possibilities | Tested just <0.02% of total possibilities, representing an estimated 85% reduction in experiments [5] | |

| Algorithmic Process Optimization (APO) with Merck | Multi-objective problems at scale | Awarded 2025 ACS Green Chemistry Award for sustainable innovation | Reduced hazardous reagents, material waste, and accelerated development timelines [6] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Bayesian Optimization Workflows

Protocol 1: Scalable Multi-Objective Optimization with Minerva

This methodology is designed for highly parallel HTE campaigns, such as in 96-well plates [2].

- Problem Formulation: Define the reaction condition space as a discrete combinatorial set of plausible conditions, incorporating practical constraints (e.g., solvent safety, boiling points).

- Initial Sampling: Use quasi-random Sobol sampling to select an initial batch of experiments. This maximizes initial coverage of the reaction space.

- Model Training & Experiment Selection:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on the collected experimental data to predict reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and their uncertainties.

- Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI, or q-NEHVI) to evaluate all possible conditions and select the next batch of experiments. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performing areas.

- Iteration: Repeat the cycle of experimentation, model updating, and batch selection until objectives are met or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Adaptive Boundary Constraint Bayesian Optimization (ABC-BO)

This protocol is designed to prevent futile experiments in complex reaction spaces [1].

- Standard BO Setup: Begin a standard Bayesian optimization process with a defined objective function and search space.

- Boundary Assessment: Before executing a suggested experiment, calculate whether the given conditions could theoretically improve the existing best objective, even assuming a 100% yield.

- Constraint Application: If the experiment is deemed "futile," the algorithm adaptively excludes it and re-directs the acquisition function to suggest a more promising condition.

- Focused Optimization: As the optimization progresses, the algorithm dynamically narrows its focus to the shrinking set of truly promising experimental conditions, maximizing the value of each experiment.

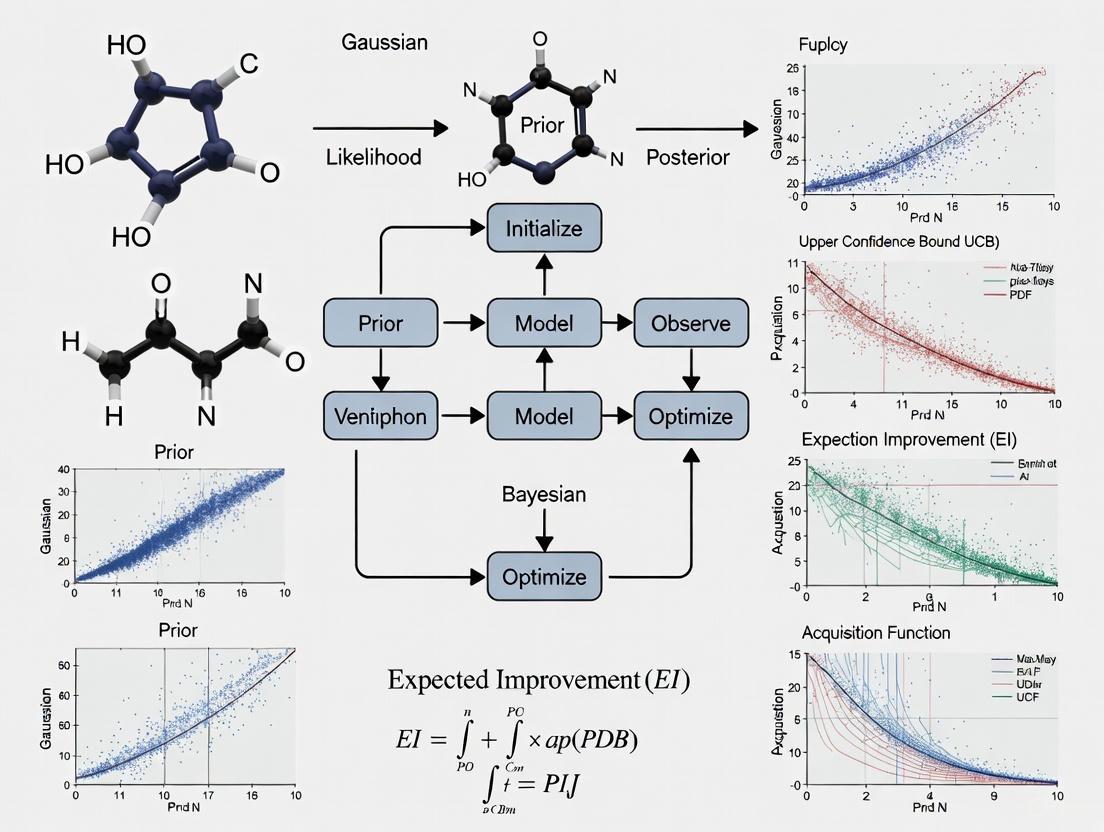

Workflow Visualization: Bayesian Optimization Logic

The diagram below illustrates the core iterative workflow of a Bayesian Optimization campaign for chemical reaction development.

Core Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions in machine-learning-driven reaction optimization campaigns, as featured in the cited research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in ML-Driven Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Earth-abundant, cost-effective alternative to precious metal catalysts for cross-coupling reactions. | Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction optimization [2] [4] |

| Palladium Catalysts | High-performance catalysts for key C-C and C-N bond-forming reactions like Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings. | Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig amination [2] [4] |

| Ligand Libraries | Modular components that significantly influence catalyst activity and selectivity; a primary categorical variable for screening. | Explored in high-dimensional search spaces to find optimal catalyst systems [2] |

| Solvent Sets | Medium that affects reaction kinetics, solubility, and mechanism; a key categorical variable to optimize. | Screened following pharmaceutical green chemistry guidelines (e.g., solvent selection guides) [2] |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Automated robotic systems enabling miniaturized, highly parallel execution of reactions (e.g., in 96-well plates). | Essential for generating the large datasets required for efficient ML-guided optimization [2] [4] |

| Chitin synthase inhibitor 8 | Chitin synthase inhibitor 8, MF:C23H23N3O5, MW:421.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-epi-Azido-3-deoxythymidine | 3-epi-Azido-3-deoxythymidine, MF:C10H13N5O4, MW:267.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bayesian Optimization as a Solution for Black-Box, Expensive-to-Evaluate Functions

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My Bayesian Optimization (BO) process is converging slowly. How can I improve its performance?

Slow convergence often stems from an imbalance between exploration and exploitation. You can adjust the acquisition function's parameters to better suit your problem. For the Expected Improvement (EI) function, increase the ξ (xi) parameter to encourage more exploration of uncertain regions [7] [8]. Additionally, ensure your initial dataset is sufficient; starting with too few random samples (e.g., less than 5-10) can lead to poor surrogate model fitting [9]. For high-dimensional spaces, consider using a Sobol sequence for initial sampling to maximize space-filling properties [2].

Q2: How should I handle categorical variables, like solvent or catalyst type, in my BO setup? Categorical variables require special treatment as standard Gaussian Processes (GPs) model continuous spaces. One effective approach is to represent the reaction condition space as a discrete combinatorial set of potential conditions [2]. Convert categorical parameters into numerical descriptors. The algorithm can then automatically filter out impractical combinations based on domain knowledge (e.g., excluding temperatures exceeding a solvent's boiling point) [2]. For ligand or solvent screening, treat each unique combination as a distinct category within the optimization space.

Q3: A significant portion of my experiments are "futile" – they cannot possibly improve the objective. How can I prevent this? Implement an Adaptive Boundary Constraint (ABC-BO) strategy [1]. Before running an experiment, check if the proposed conditions could theoretically improve the best-known objective, even assuming a 100% yield. If not, the algorithm should reject these conditions and propose new ones. This is particularly useful for objective functions like throughput, where physical limits can be calculated. This method has been shown to reduce futile experiments by up to 50% in complex reaction optimizations [1].

Q4: What should I do when my objective function evaluations are noisy or my measurements have significant experimental error? Incorporate a nugget term (also known as a jitter term) into your Gaussian Process model [9]. This term, added to the diagonal of the covariance matrix, accounts for measurement noise and improves computational stability. Estimate the noise level from your data if possible, or set it to a small positive value. Using a nugget is recommended even for deterministic simulations, as it helps account for the bias between the simulation and reality [9].

Q5: How can I optimize for multiple objectives simultaneously, such as maximizing yield while minimizing cost? Use Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO). For highly parallel setups (e.g., 96-well plates), scalable acquisition functions like q-NParEgo, Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI), or q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) are recommended [2]. These functions efficiently handle multiple competing objectives and large batch sizes. Performance can be evaluated using the hypervolume metric, which measures both convergence towards optimal objectives and the diversity of solutions [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: The algorithm seems stuck in a local optimum.

- Potential Cause: Over-exploitation due to an acquisition function that favors known high-performing regions too heavily.

- Solution: Switch to the "plus" variant of your acquisition function (e.g.,

expected-improvement-plus), which detects overexploitation and modifies the kernel function to increase variance in unexplored areas, encouraging escape from local optima [10]. Alternatively, manually increase the exploration parameter in EI or UCB functions.

Problem: The Gaussian Process model is taking too long to fit.

- Potential Cause: The computational complexity of GPs scales as O(N³) with the number of data points, becoming slow with hundreds of evaluations [11].

- Solution: For problems requiring many evaluations, consider surrogate models that scale better, such as Random Forests or Bayesian Neural Networks [3]. Since experimental evaluations are expensive, staying below 1000 data points is common, where GPs remain manageable [11].

Problem: BO fails to find good conditions in a very large search space.

- Potential Cause: The search space is too vast or contains many impractical regions.

- Solution: Integrate domain expertise to define a plausible reaction condition space first [2]. Use algorithmic quasi-random sampling (e.g., Sobol sequences) for the initial batch to ensure broad coverage. This increases the likelihood of discovering informative regions containing global optima.

Bayesian Optimization Components and Performance

Table 1: Common Acquisition Functions and Their Use Cases

| Acquisition Function | Key Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) [7] [10] | Balances probability and amount of improvement; most widely used [8]. | General-purpose optimization; a reliable default choice. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) [7] [10] | Focuses on the likelihood of improvement, can get stuck in local optima. | When a quick, simple solution is needed; less recommended for global optimization. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [10] [9] | Uses a confidence bound parameter (κ) to explicitly balance exploration and exploitation. | Problems where a clear trade-off between exploration/exploitation is desired. |

| q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) [2] | Scalable, multi-objective acquisition function. | Simultaneous optimization of multiple objectives (e.g., yield, cost, selectivity) in large batches. |

| Thompson Sampling (TS) [2] [3] | Randomly draws functions from the posterior and selects the best point. | Multi-objective optimization and highly parallel batch evaluations. |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for a Bayesian Optimization Campaign

| Reagent / Component | Function in the Optimization |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) [7] [9] | Core surrogate model; approximates the unknown objective function and provides uncertainty estimates. |

| Matérn 5/2 Kernel [10] [9] | A common covariance function for the GP; less smooth than the RBF kernel, making it better for modeling physical phenomena [9]. |

| Nugget Term [9] | A small value added to the kernel's diagonal to account for experimental noise and improve numerical stability. |

| Sobol Sequence [2] | A quasi-random sequence for selecting initial experiments; ensures the design space is evenly sampled. |

| Hypervolume Metric [2] | A performance metric for multi-objective optimization; calculates the volume of objective space dominated by the found solutions. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The following workflow is adapted from real-world applications in chemical synthesis [2] [3].

Problem Definition

- Define the objective(s) (e.g., reaction yield, selectivity, space-time yield).

- Identify all optimization variables (continuous: temperature, concentration; categorical: solvent, catalyst).

- Set feasible bounds for all variables.

Initial Experimental Design

- Select an initial set of experiments using a Sobol sequence or random sampling within the defined bounds.

- For a typical 96-well HTE plate, a common initial batch size is 24, 48, or 96 reactions [2].

- Run the experiments and record the outcomes.

Model Fitting and Iteration

- Surrogate Model Construction: Fit a Gaussian Process model to the collected data. The Matern 5/2 kernel is often recommended [9].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize the GP's hyperparameters (length scales, output scale, noise variance) using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) [9].

- Next Experiment Selection: Use an acquisition function (e.g., EI) to determine the most promising conditions for the next batch of experiments.

- Automated Filtering: Apply constraints (like ABC-BO) to filter out futile experiments before execution [1].

- Data Augmentation: Run the new experiments and add the results to the dataset.

Termination

- Repeat Step 3 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., no significant improvement over several iterations, a desired performance threshold is reached, or the experimental budget is exhausted).

Workflow and Algorithm Visualization

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | Poor model fit, inaccurate predictions in unexplored regions. | Incorrect prior width or over-smoothing due to improper kernel lengthscale. | Tune GP hyperparameters (amplitude, lengthscale) via Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Consider a more flexible kernel (e.g., Matern 5/2). | [12] [13] |

| Acquisition Function | Optimization gets stuck in local optima, lacks exploration. | Inadequate balance between exploration and exploitation (e.g., incorrect ϵ in PI, low β in UCB). |

Switch to a more robust AF like Expected Improvement (EI). For multi-objective problems, use q-NParEgo or TS-HVI. | [12] [7] [13] |

| Computational Performance | Long delays in selecting new experiments, especially with large batches. | High complexity of multi-objective acquisition functions (e.g., q-EHVI) scaling poorly with batch size. | Use scalable AFs like TS-HVI or q-NParEgo for large parallel batches (e.g., 96-well plates). | [2] |

| Prior Specification | Posterior results are biased or unrealistic. | Poorly chosen prior distributions that do not accurately reflect domain knowledge. | Perform sensitivity analysis on priors. Use hierarchical modeling or empirical Bayes to estimate priors from data. | [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the most suitable surrogate model for handling the noise commonly found in chemical reaction data?

Gaussian Processes (GPs) are the most commonly used and recommended surrogate model for Bayesian optimization in chemistry [15] [3] [13]. They are particularly effective because they not only provide a prediction (the posterior mean) but also a quantitative measure of uncertainty (the posterior variance) for any point in the search space [13]. This uncertainty quantification is crucial for guiding the exploration-exploitation trade-off. GPs can naturally handle noisy observations by incorporating a noise term (e.g., Gaussian noise) directly into the model [13].

How do I choose an acquisition function for simultaneously optimizing both reaction yield and selectivity?

When moving from a single objective to multiple objectives, you must use a multi-objective acquisition function. The core goal shifts from finding a single best point to mapping a Pareto front—a set of conditions where one objective cannot be improved without worsening another [2] [3].

For highly parallel experimentation, such as 96-well HTE plates, traditional methods like q-EHVI can be computationally slow. In these cases, it is recommended to use more scalable functions like:

- q-NParEgo

- Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI) [2]

These functions are designed to efficiently handle large batch sizes and high-dimensional search spaces common in real-world laboratories [2].

Our optimization keeps converging to a local optimum. How can we encourage more exploration?

This is a classic sign of an acquisition function that is over-exploiting. You can address this by:

- Adjusting AF Parameters: If using Probability of Improvement (PI), increase the

ϵparameter to encourage exploring more uncertain regions. If using Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), increase theβparameter to give more weight to the uncertainty term [7]. - Switching the AF: Consider using Expected Improvement (EI), which typically offers a better balance by considering both the probability and magnitude of improvement [15] [13]. It is a popular choice due to its well-balanced performance and straightforward analytic form [15].

What are the best practices for specifying priors in the Gaussian Process model when historical data is limited?

Specifying priors is a known challenge in Bayesian methods [14]. With limited data, you can:

- Use Sensitivity Analysis: Test how different prior choices affect your final results to ensure they are not introducing bias [14].

- Adopt Hierarchical Modeling: This allows you to incorporate multiple levels of information, making the model more robust [14].

- Leverage Chemical Intuition: Your domain knowledge as a chemist is invaluable. Use it to define reasonable bounds and constraints for the search space (e.g., excluding solvent and temperature combinations that would cause boiling) [2] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bayesian Optimization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Serves as the core surrogate model; approximates the expensive black-box function (e.g., reaction yield) and provides uncertainty estimates. | The Matern 5/2 kernel is recommended for practical optimization due to its flexibility [13]. Hyperparameters (lengthscale, amplitude) must be tuned. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | A popular acquisition function that selects the next experiment by calculating the expected value of improving upon the current best result. | Balances exploration and exploitation effectively and has an analytic form for efficient computation [15] [13]. |

| Sobol Sequence | A space-filling design algorithm used to select the initial set of experiments before the Bayesian loop begins. | Maximally spreads out initial experiments across the search space, increasing the chance of finding promising regions early [2]. |

| Thompson Sampling (TS-HVI) | A multi-objective acquisition function suitable for large parallel batches. Efficiently scales to 96-well plates. | Helps overcome the computational bottlenecks of other multi-objective functions like q-EHVI in high-throughput settings [2]. |

| 9-Dihydroestradiol-d3 | 9-Dihydroestradiol-d3, MF:C18H22O2, MW:273.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Xanthine oxidase-IN-6 | Xanthine oxidase-IN-6, MF:C29H34N2O15, MW:650.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of Bayesian Optimization, which can be applied to the optimization of chemical reactions.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Initial Design: Use a space-filling design like Sobol sampling to select an initial set of

nâ‚€reaction conditions (e.g., 10-20% of your experimental budget). This maximizes early information gain about the landscape [2] [13]. - Run Experiments: Conduct the chemical reactions at the chosen conditions and measure the outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity, etc.).

- Update Dataset: Add the new {reaction conditions, results} pairs to your growing dataset

Dâ‚™. - Build Surrogate Model: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) model on the current dataset

Dâ‚™. The GP will model the objective function across the entire search space, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates [13]. - Maximize Acquisition Function: Using the trained GP, compute an acquisition function (AF) like Expected Improvement (EI) across the search space. Identify the reaction condition that maximizes this function [15] [13].

- Check Stopping Criterion: If the experimental budget is exhausted, a satisfactory result is found, or further iterations show no improvement, stop the process. Otherwise, return to Step 2 with the new candidate suggested by the AF.

Workflow Diagram: Multi-Objective Optimization with Large Batches

For industrial applications like pharmaceutical process development, optimization often involves multiple objectives and highly parallel experiments. The following diagram outlines a workflow adapted for this scale.

Key Adaptations for Scale:

- Condition Space: The search space is defined as a discrete set of plausible reaction conditions, automatically filtering out unsafe or impractical combinations (e.g., NaH in DMSO, temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [2].

- Scalable Acquisition: Instead of selecting one experiment per iteration, the AF selects a large batch of experiments in parallel. This requires using scalable AFs like TS-HVI or q-NParEgo that can handle the computational load of proposing dozens of experiments at once [2].

- Objective: The outcome is a set of Pareto-optimal conditions, giving process chemists multiple viable options that represent the best trade-offs between competing objectives like yield, selectivity, and cost [2].

Within the framework of a thesis on Bayesian optimization for chemical reaction conditions research, Gaussian Processes (GPs) serve as a cornerstone for building intelligent, data-efficient optimization systems. A GP is a probabilistic machine learning model that defines a distribution over functions, perfectly suited for approximating the complex, often non-linear relationship between reaction parameters (e.g., temperature, concentration, solvent choice) and experimental outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) [3]. In Bayesian optimization (BO), the GP acts as a surrogate model, or emulator, of the expensive-to-evaluate experimental function. It provides not just a prediction of the outcome for untested conditions but, crucially, a measure of uncertainty for that prediction [17] [18]. This uncertainty quantification is the engine of BO, enabling acquisition functions to strategically balance the exploration of unknown regions of the reaction space with the exploitation of known promising conditions, thereby accelerating the discovery of optimal reaction parameters with minimal experimental effort [3] [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common GP Challenges in Reaction Optimization

This guide addresses specific, high-impact challenges researchers may encounter when applying GPs to chemical reaction optimization.

Poor Model Performance and Prediction Inaccuracy

- Problem: GP predictions are inaccurate or the model is overconfident in incorrect predictions, leading to poor optimization guidance.

- Causes & Solutions:

- Inadequate Kernel Function: The kernel determines the GP's assumptions about the function's behavior. A standard Squared Exponential (Radial Basis Function) kernel assumes a very smooth response, which may not hold for complex chemical landscapes.

- Solution: Experiment with more flexible kernel structures. The Matérn kernel (e.g., Matérn 5/2) is a robust default as it accommodates less smooth functions [18]. For specialized applications, custom kernel combinations (e.g., additive or multiplicative kernels) can be tested to capture different scales of variation [19].

- Dominant Mean Function: An overly strong prior mean function can cause the model to ignore the data, leading to high confidence in poor predictions.

- Solution: Weaken the influence of the mean function, for example, by using a constant mean and optimizing its hyperparameter, rather than a complex, fixed mean function [20].

- Improperly Optimized Hyperparameters: The kernel's hyperparameters (e.g., length scale, noise) control the model's fit.

- Inadequate Kernel Function: The kernel determines the GP's assumptions about the function's behavior. A standard Squared Exponential (Radial Basis Function) kernel assumes a very smooth response, which may not hold for complex chemical landscapes.

Handling Categorical and High-Dimensional Inputs

- Problem: Reaction optimization involves categorical variables (e.g., solvents, ligands, catalysts) and potentially many continuous parameters, making standard GP application difficult.

- Causes & Solutions:

- Non-Numerical Inputs: Standard GP kernels operate on continuous numerical spaces.

- High-Dimensional Search Space: The computational cost of GPs scales poorly with the number of dimensions, and modeling becomes data-inefficient.

- Solution: Use dimension reduction techniques like Karhunen-Loève (KL) expansions to approximate the high-dimensional input field with a finite number of dominant stochastic dimensions, making emulation computationally feasible [17].

Managing Multiple Objectives and Outputs

- Problem: Chemical optimization typically involves multiple, often competing objectives (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost or environmental impact). Standard single-task GPs cannot model correlations between these outputs.

- Causes & Solutions:

- Independent Modeling is Suboptimal: Modeling each property with an independent GP fails to leverage shared information, slowing down the discovery process.

- Solution: Employ multi-task GPs (MTGPs) or hierarchical models like Deep GPs (DGPs). These use advanced kernel structures to capture correlations between distinct material properties, allowing information from one objective to inform others and significantly accelerating multi-objective optimization [22].

- Independent Modeling is Suboptimal: Modeling each property with an independent GP fails to leverage shared information, slowing down the discovery process.

Computational Bottlenecks with Large Datasets

- Problem: GP training time becomes prohibitively slow as the number of experimental data points increases, hindering rapid iteration.

- Causes & Solutions:

- Cubic Scaling Cost: The computational complexity of standard GP inference is O(n³), where n is the number of data points.

- Solution: For large-scale High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) campaigns, utilize scalable GP approximations. Sparse GPs or inducing point methods (e.g., implemented in libraries like GAUCHE) approximate the full model using a subset of "inducing points," reducing computational cost while maintaining performance [21] [18].

- Cubic Scaling Cost: The computational complexity of standard GP inference is O(n³), where n is the number of data points.

Dealing with Bifurcating Solutions or Multiple Equilibria

- Problem: In some physico-chemical processes, multiple stable equilibrium states (bifurcating solutions) can exist for the same input parameters. A single GP emulator will fail in such regions, as it expects a single output for a given input.

- Causes & Solutions:

- Non-Unique Outputs: The presence of a bifurcation point violates the fundamental assumption of a function.

- Solution: Implement a combined classification and regression approach. First, use a Gaussian process classifier to predict which branch or class the output belongs to for a given input. Then, build separate GP regressors for each class of solutions to model the output within that branch, enabling successful uncertainty analysis near bifurcation points [17].

- Non-Unique Outputs: The presence of a bifurcation point violates the fundamental assumption of a function.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a GP preferred over other surrogate models like Random Forests in Bayesian optimization for chemistry? A1: GPs are intrinsically probabilistic, providing principled uncertainty estimates (predictive variances) directly from the model structure. This native uncertainty quantification is essential for the acquisition function to effectively balance exploration and exploitation. While other models can be adapted, GPs are particularly well-suited for data-scarce scenarios common in experimental chemistry [3] [18].

Q2: My experimental measurements are noisy. How can the GP model account for this?

A2: GPs can explicitly model observation noise by including a noise term in the covariance function. This is typically a white noise kernel. During model training, the hyperparameter associated with this noise term (often called the alpha or noise level parameter) is optimized from the data, allowing the GP to distinguish between the underlying trend and the stochastic noise in your experimental measurements [19] [18].

Q3: What is a key advantage of using BO with GPs over traditional Design of Experiments (DoE)? A3: The primary advantage is adaptivity. Traditional DoE relies on a fixed, pre-determined experimental plan. In contrast, BO using GPs is a sequential, model-based process. Each experiment informs the selection of the next, allowing the campaign to dynamically focus on the most promising regions of the search space. This often leads to finding optimal conditions in fewer experiments, saving valuable time and resources [18].

Q4: Are there specific acquisition functions recommended for multi-objective optimization in high-throughput chemistry? A4: Yes, for highly parallel HTE campaigns with multiple objectives, scalable acquisition functions are crucial. While q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-EHVI) is powerful, its computational cost can be high. Functions like q-NParEgo, Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI), and q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) have been developed and benchmarked to handle large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) efficiently in multi-objective settings [2].

Q5: How can I prevent my optimization algorithm from suggesting futile experiments? A5: You can incorporate domain knowledge directly into the BO loop. The Adaptive Boundary Constraint BO (ABC-BO) strategy is one such method. It uses knowledge of the objective function (e.g., knowing that yield cannot exceed 100%) to screen out experimental conditions that are mathematically incapable of improving the objective, even under ideal outcomes, thus preventing wasted experimental effort [1].

Essential Workflows and Protocols

Core GP Workflow for Reaction Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the standard iterative workflow for using a Gaussian Process in Bayesian optimization for chemical reactions.

Protocol: Implementing a GP-Based Optimization Campaign

This protocol outlines the steps for a single iteration within the broader workflow, corresponding to the "Train GP Surrogate Model" and "Optimize Acquisition Function" steps in the diagram.

- Objective: To optimize a Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction for maximum yield and selectivity.

- Search Space: 88,000 possible conditions defined by categorical (ligand, solvent, base) and continuous (temperature, concentration) variables [2].

Step-by-Step Method:

Initialization and First Batch:

- Select an initial set of experimental conditions (e.g., 1x 96-well plate) using a space-filling algorithm like Sobol sampling to ensure broad coverage of the search space [2].

- Execute the reactions and measure outcomes (Yield, Selectivity).

Data Preprocessing:

- Clean the data and handle any missing values.

- Standardize continuous variables (e.g., temperature, concentration) to have zero mean and unit variance.

- Encode categorical variables (e.g., solvent, ligand) using numerical descriptors or one-hot encoding. For complex molecules, use learned representations from libraries like GAUCHE [21].

GP Model Training:

- Model Choice: Select a GP model with a Matérn 5/2 kernel for flexibility [18].

- Multi-objective Handling: For simultaneous yield/selectivity optimization, use a Multi-Task GP (MTGP) to capture correlations between the two objectives [22].

- Training: Optimize the GP hyperparameters (length scales, noise variance) by maximizing the log marginal likelihood using a conjugate gradient algorithm.

Suggesting New Experiments:

- Define an acquisition function. For multi-objective problems, use q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) [2].

- Optimize the acquisition function over the entire search space to identify the single set or batch of conditions that promises the greatest improvement.

- Return these conditions to the experimentalist for the next iteration.

Workflow for Handling Bifurcating Solutions

For complex reaction landscapes with multiple possible equilibria, a modified workflow is required.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental resources essential for implementing GP-based optimization.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| GAUCHE Library [21] | A specialized Python library providing kernels for structured chemical data (graphs, strings) and GP tools for chemistry. | Modeling the effect of different molecular catalysts or solvents on reaction yield. |

| Multi-Task GP (MTGP) [22] | A GP variant that learns correlations between multiple output properties (e.g., yield & selectivity), accelerating multi-objective optimization. | Simultaneously optimizing for high CTE and high BM in high-entropy alloy discovery. |

| Sobol Sequence [2] | A quasi-random algorithm for generating space-filling initial experimental designs, ensuring efficient search space coverage. | Selecting the first 96 reactions in an HTE campaign to maximally reduce initial uncertainty. |

| q-NParEgo / TS-HVI [2] | Scalable acquisition functions designed for large-batch, multi-objective BO, overcoming computational limits of standard functions. | Choosing the next batch of 48 reactions in an HTE plate to efficiently explore the Pareto front of yield vs. cost. |

| ABC-BO Strategy [1] | (Adaptive Boundary Constraint) Prevents futile experiments by incorporating objective function knowledge (e.g., 100% yield maximum). | Avoiding suggestions of conditions that are theoretically incapable of improving throughput, even with 100% yield. |

| Karhunen-Loève (KL) Expansion [17] | A dimension reduction technique that approximates a random field (e.g., permeability heterogeneity) with a finite number of variables. | Making uncertainty quantification computationally feasible in models of CO₂ dissolution in complex, heterogeneous porous media. |

| Melengestrol acetate-d6 | Melengestrol acetate-d6, MF:C24H30O4, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| cIAP1 Ligand-Linker Conjugates 3 | cIAP1 Ligand-Linker Conjugates 3, MF:C39H56N4O11S, MW:788.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Concepts: Your Acquisition Function Guide

Acquisition Functions (AFs) are the decision-making engine of Bayesian Optimization (BO), intelligently guiding the selection of the next experiments by balancing the exploration of unknown regions of the search space with the exploitation of known promising areas [3] [23].

The following table summarizes the most common acquisition functions used in chemical reaction optimization.

| Acquisition Function | Mechanism for Balancing Exploration & Exploitation | Typical Use Case in Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [24] [23] | Uses an explicit parameter (λ or β) to weight the mean (μ, exploitation) against the uncertainty (σ, exploration): α(x) = μ(x) + λσ(x) [24] [23]. |

Highly tunable for specific campaign goals; a small λ favors fine-tuning known conditions, while a large λ promotes broad screening [23]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) [12] [23] | Calculates the expected value of improvement over the current best result, considering both the probability and magnitude of improvement [23]. | The most common choice for single-objective optimization; efficiently hones in on high-performance conditions without an explicit tuning parameter [3]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) [12] [23] | Measures only the probability that a new point will be better than the current best, ignoring the potential size of the improvement [23]. | Less common than EI, as it can get stuck in modest, incremental improvements [12]. |

| q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) [2] | A advanced, scalable function for multi-objective optimization (e.g., maximizing yield and selectivity simultaneously) that measures improvement in the volume of dominated space [2]. | Ideal for highly parallel HTE campaigns (e.g., 96-well plates) with multiple, competing objectives [2]. |

Workflow of a Bayesian Optimization Cycle

The diagram below illustrates how the acquisition function integrates into the iterative Bayesian Optimization workflow for chemical reaction optimization.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the single most important role of an acquisition function? The acquisition function automates the critical trade-off between exploration (testing new, uncertain reaction conditions) and exploitation (refining known high-performing conditions), making sample-efficient decisions on which experiments to run next [3] [23].

Q2: Why is Expected Improvement (EI) often preferred over Probability of Improvement (PI)? While PI only considers the chance of improvement, EI calculates the average amount of expected improvement. This means EI will favor a candidate condition that will likely yield a 20% increase over a candidate that will likely yield a 1% increase, even if both have the same probability of success, leading to more rapid optimization [12] [23].

Q3: How do I choose an acquisition function for a multi-objective problem, like maximizing yield while minimizing cost? For multi-objective optimization, you should use specialized acquisition functions like q-NParEgo or q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI). These are designed to identify a set of optimal solutions (a Pareto front) that balance the trade-offs between your competing objectives [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Optimization appears trapped in a local optimum, failing to find better conditions.

- Potential Cause: Over-exploitation due to an inadequately tuned acquisition function or poor surrogate model priors [12].

- Solution:

- Increase Exploration: If using UCB, increase the λ or β parameter to give more weight to uncertain regions [24] [23].

- Switch the AF: Consider using Expected Improvement, which has a built-in balance.

- Check the Prior: Ensure the Gaussian Process prior width is correctly specified; an incorrect prior can lead to over-confident or over-cautious models [12].

Problem: The optimization process is unstable, suggesting chemically implausible conditions.

- Potential Cause: The algorithm is exploring too aggressively without domain knowledge constraints [16].

- Solution:

- Constrain the Search Space: Pre-define a discrete set of plausible conditions (e.g., solvents that are stable at the reaction temperature) to prevent the algorithm from evaluating unsafe or impractical combinations [2].

- Use a Hybrid Framework: Integrate an LLM-based "reasoning" layer to filter out candidates that violate known chemical rules before running the experiment [16].

Problem: Performance is poor despite many experiments, especially with categorical variables (e.g., ligands, solvents).

- Potential Cause: The surrogate model struggles with high-dimensional or complex categorical search spaces [2].

- Solution:

- Use a Different Regressor: Consider using a surrogate model better suited for categorical data, such as Random Forests [3].

- Apply Scalable MOBO: For large-scale High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) with many categories, employ a scalable framework like Minerva with acquisition functions like TS-HVI or q-NParEgo designed for this purpose [2].

Featured Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction via HTE

This protocol details the methodology for a 96-well plate HTE optimization campaign as described in the Minerva framework [2].

Objective

To identify the reaction conditions that maximize the area percent (AP) yield and selectivity for a challenging nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Reaction |

|---|---|

| Nickel Catalyst | Non-precious metal catalyst to facilitate the cross-coupling reaction [2]. |

| Ligand Library | A set of diverse organic molecules that bind to the nickel center and modulate its reactivity and selectivity [2]. |

| Base Additives | To neutralize reaction byproducts and facilitate the catalytic cycle [2]. |

| Solvent Library | A collection of organic solvents with varying polarity, dielectric constant, and coordination ability to solubilize reactants and influence reaction outcome [2]. |

| Aryl Halide & Boronic Acid | The core coupling partners in the Suzuki reaction [2]. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the specific high-throughput workflow for optimizing the Suzuki reaction.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Search Space Definition:

- Define a combinatorial space of 88,000 potential reaction conditions by selecting plausible ranges and categories for variables such as catalyst loading, ligand identity, solvent, additive, and temperature. Automated filtering is applied to exclude unsafe combinations [2].

Initial Experimental Design:

- Select an initial batch of 96 reaction conditions using Sobol sampling. This quasi-random method ensures the first batch is spread diversely across the entire search space to maximize initial knowledge gain [2].

Automated High-Throughput Experimentation:

- Use an automated liquid handling robot to dispense reagents and catalysts into a 96-well plate according to the selected conditions [2].

- Execute all 96 reactions in parallel under their specified conditions (e.g., temperature).

Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze the reaction outcomes in parallel using techniques like UHPLC to obtain quantitative metrics for yield and selectivity (Area Percent) [2].

- Compile the results into a dataset linking each condition to its outcomes.

Machine Learning Iteration Loop:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model on the collected data to predict outcomes and uncertainties for all unexplored conditions [2].

- Apply the q-NEHVI acquisition function to the GP's predictions to select the next batch of 96 conditions that promise the greatest hypervolume improvement for both yield and selectivity [2].

- Repeat steps 3-5 until convergence (e.g., no significant improvement is observed) or the experimental budget is exhausted. The reported result was identification of conditions yielding 76% AP yield and 92% selectivity [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Bayesian Optimization Issues in Chemical Reaction Optimization

FAQ 1: My optimization is converging slowly or seems stuck. How can I improve its performance?

Answer: Slow convergence often stems from an imbalance between exploring new regions of the search space and exploiting known promising areas. This is frequently observed when optimizing complex chemical reactions with multiple categorical variables (like ligands or solvents) that can create isolated optima in the yield landscape [2].

- Adjust Your Acquisition Function: The acquisition function controls the exploration-exploitation trade-off. If stuck, try switching from a purely exploitative function to one more weighted towards exploration.

- Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) are common choices. UCB is parameterized by a

kappavalue, where a higherkappapromotes more exploration [25] [3]. - For multi-objective problems (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost), functions like q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) or Thompson Sampling (TS) have demonstrated strong performance [2] [3].

- Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) are common choices. UCB is parameterized by a

- Re-evaluate Your Surrogate Model: The model that approximates your objective function is critical.

- Gaussian Processes (GP) with anisotropic kernels (like the Matérn kernel with Automatic Relevance Detection - ARD) can outperform simpler models because they learn the sensitivity of the objective to each input feature (e.g., temperature vs. catalyst loading) [25].

- Random Forest (RF) models are a strong, assumption-free alternative to GPs and can handle high-dimensional spaces efficiently [25].

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Use chemical intuition to constrain the search space. For example, if you know certain solvent and temperature combinations are unsafe or impractical, explicitly filter them out. Advanced strategies like Adaptive Boundary Constraint BO (ABC-BO) can automatically prune "futile" experiments that are mathematically incapable of improving the objective, even with a 100% yield, saving significant experimental budget [1].

FAQ 2: How do I handle multiple, competing objectives like yield and cost simultaneously?

Answer: This is a Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) problem. The goal is to find a set of "Pareto-optimal" conditions where improving one objective means worsening another [3].

- Use Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions: Standard functions like EI are not suitable. Instead, employ functions designed for multiple objectives:

- q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI): Directly targets the enlargement of the Pareto front [2].

- Thompson Sampling for Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI): A scalable alternative effective for large parallel batches [2].

- q-NParEgo: Another scalable option for high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms [2].

- Track the Hypervolume Metric: This metric quantifies the volume of the objective space dominated by your discovered Pareto front. It measures both convergence towards the true optimum and the diversity of solutions. Monitor this metric to assess the progress of your optimization campaign [2].

FAQ 3: A recommended experiment seems chemically implausible or risky. Should I run it?

Answer: No. Do not run experiments that violate safety principles or well-established chemical knowledge. Bayesian optimization treats the reaction as a black box and may suggest conditions that are mathematically promising but chemically invalid.

- Constrained BO: Implement hard constraints in your BO algorithm to filter out invalid suggestions. This can be based on:

- Physical Laws: For example, excluding temperatures above a solvent's boiling point [2].

- Thermodynamic Models: In bioprocessing, integrating activity coefficient models can prevent suggestions that would cause amino acid precipitation in cell culture media [26].

- Chemical Logic: Pre-define "implausible" combinations, such as using a base-labile reagent in a strongly basic environment [2].

- Interactive BO: Use a human-in-the-loop approach. The algorithm proposes a batch of experiments, and a chemist reviews them, vetoing unsafe options before the experiments are conducted. This combines algorithmic efficiency with expert knowledge.

FAQ 4: How can I find reaction conditions that work for many related substrates (generality)?

Answer: This is known as generality-oriented optimization. The goal is to find a single set of robust parameters (conditions) that perform well across a diverse set of tasks (substrates) [27].

- Formulate as a Curried Function: Structure the problem as optimizing over a function

f(x, w), wherexis the condition parameters andwis the discrete task (substrate). The objective is to find thexthat maximizes average performance across allw[27]. - Strategic Task Selection: Since testing every condition on every substrate is too expensive, the algorithm must also choose which substrate to test next.

Key Bayesian Optimization Performance Data

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of Common Surrogate Models in Materials Science [25]

| Surrogate Model | Key Characteristics | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GP with anisotropic kernels (ARD) | Learns individual length scales for each input dimension; models sensitivity. | Most robust performance across diverse experimental datasets; outperforms isotropic GP. |

| Random Forest (RF) | No distribution assumptions; lower time complexity; minimal hyperparameter effort. | Performance comparable to GP-ARD; a strong alternative, especially in high dimensions. |

| GP with isotropic kernels | Uses a single length scale for all dimensions. | Commonly used but consistently outperformed by GP-ARD and RF in benchmarks. |

Table 2: Comparison of Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions for High-Throughput Experimentation [2]

| Acquisition Function | Best For | Scalability to Large Batches (e.g., 96-well) |

|---|---|---|

| q-NParEgo | Scalable multi-objective optimization. | Highly scalable. |

| Thompson Sampling (TS-HVI) | Scalable multi-objective optimization. | Highly scalable. |

| q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume (q-NEHVI) | Direct hypervolume improvement. | Scalable. |

| q-Expected Hypervolume (q-EHVI) | Direct hypervolume improvement. | Less scalable; complexity scales exponentially with batch size. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Bayesian Optimization Workflow

This protocol outlines a generalized BO cycle for optimizing a chemical reaction, adaptable for both sequential and small-batch experiments.

Objective: Maximize the yield of a nickel-catalyzed Suzuki coupling reaction. Variables: Ligand (categorical, 10 options), Solvent (categorical, 8 options), Temperature (continuous, 25°C - 100°C), Catalyst Loading (continuous, 0.5 - 5 mol%).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Initial Experimental Design:

- Select an initial set of 8-16 experiments using a Sobol sequence or other space-filling design. This ensures the initial data points are well-spread across the entire reaction condition space, aiding the initial model build [2].

Model Building (Surrogate Model):

Recommendation via Acquisition Function:

- Using the trained GP model, calculate an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) over the entire search space.

- Select the next condition (or batch of conditions) that maximizes the acquisition function. This is the "recommended experiment."

Execution and Data Augmentation:

- Conduct the experiment(s) with the recommended conditions.

- Measure the outcome (yield) and add the new

(conditions, yield)data pair to the existing dataset.

Iteration and Termination:

- Repeat steps 2-4 until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., yield >95%, no significant improvement over 3-5 iterations, or exhaustion of the experimental budget).

- The optimal condition reported is the one with the highest observed yield from all experiments conducted.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Bayesian Optimization Campaign in Reaction Optimization

| Item / Solution | Function in the BO Workflow |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Model | The core surrogate model that predicts reaction outcomes (e.g., yield) and their uncertainties for any set of conditions based on prior data [2] [25]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., EI, UCB) | An algorithm that uses the GP's predictions to balance exploration and exploitation, deciding the most informative experiment to run next [25] [3]. |

| Categorical Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical choices (e.g., solvents, ligands) that allow the algorithm to reason about their chemical similarity and impact on the reaction [2]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robot | Automation platform that enables the highly parallel execution of the batch of experiments recommended by the BO algorithm, drastically accelerating the optimization cycle [2]. |

| Multi-Objective Algorithm (e.g., q-NEHVI) | A specialized acquisition function used when optimizing for several competing objectives at once (e.g., yield, selectivity, cost), identifying the Pareto-optimal set of conditions [2]. |

| Constrained Search Space | A pre-defined set of chemically plausible conditions, often curated by a chemist, which prevents the BO algorithm from recommending unsafe or impractical experiments [2] [1]. |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-PEG4-NH2 hydrochloride | (S,R,S)-AHPC-PEG4-NH2 hydrochloride|VHL Ligand for PROTAC |

| Quercetin 3-Caffeylrobinobioside | Quercetin 3-Caffeylrobinobioside, MF:C36H36O19, MW:772.7 g/mol |

Implementing Bayesian Optimization: Methods and Real-World Chemical Applications

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: My optimization is stuck in a local optimum. How can I improve exploration?

- A: This can happen if the balance between exploration and exploitation is off. Try adjusting your acquisition function's parameters (e.g., increase the

kappaparameter in the Upper Confidence Bound function to favor exploration) [28]. Also, ensure your initial Sobol sample is large enough to adequately cover the parameter space before the Bayesian optimization loop begins [28] [2].

- A: This can happen if the balance between exploration and exploitation is off. Try adjusting your acquisition function's parameters (e.g., increase the

Q: How should I handle failed or invalid experiments in my data?

- A: Failed experiments are common and can be treated as unknown feasibility constraints. Instead of discarding this data, use a variational Gaussian process classifier to learn the constraint function on-the-fly. This model can be combined with your primary surrogate model to parameterize feasibility-aware acquisition functions, which will actively avoid regions predicted to be infeasible in future suggestions [29].

Q: What is the advantage of using Sobol sequences over simple random sampling for the initial design?

- A: Sobol sequences are a type of low-discrepancy sequence designed to provide more uniform coverage of the parameter space than random sampling. This property, known as equidistribution, helps the initial surrogate model learn a better representation of the underlying function from the very first batch, leading to faster convergence in the subsequent Bayesian optimization steps [30] [2].

Q: My optimization involves multiple, competing objectives (e.g., high yield and low cost). What strategies can I use?

- A: You need to implement Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO). Instead of a single score, the surrogate model models each objective. Acquisition functions like

q-NEHVI(q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement) are then used to efficiently search for a set of Pareto-optimal solutions that represent the best trade-offs between your objectives [3] [2]. For objectives with a known hierarchy, frameworks likeBoTierthat use tiered scalarization functions can be more efficient [31].

- A: You need to implement Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO). Instead of a single score, the surrogate model models each objective. Acquisition functions like

Q: How do I know when to stop the optimization process?

- A: Common convergence criteria include reaching a maximum number of function evaluations, exhausting a predefined computational or experimental budget, or observing that the improvement between iterations falls below a set threshold for a sustained period [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance of the Initial Surrogate Model

Problem: The model trained on the initial sample has high prediction error, leading to poor suggestions from the first few batches of Bayesian optimization.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check Initial Sample Size and Quality:

- Cause: The initial sample size may be too small for the dimensionality of your problem, or the sampling method may provide poor coverage.

- Solution: Ensure your initial sample size is sufficient. Compare the space-filling properties of your Sobol sample against a Latin Hypercube Sample (LHS). Sobol sequences generally provide better and more reproducible coverage [30] [2].

- Protocol: Generate a 2D Sobol sequence and a 2D LHS of the same size. Plot them to visually compare uniformity. Calculate the discrepancy—a lower value indicates better space-filling.

Verify Data Preprocessing:

- Cause: Input parameters on different scales can skew the surrogate model.

- Solution: Standardize or normalize all continuous input parameters (e.g., to zero mean and unit variance). For categorical variables, use appropriate descriptors or embeddings [2].

Inspect Kernel Choice:

- Cause: The default kernel for the Gaussian Process may be unsuitable for your objective function's properties (e.g., smoothness, periodicity).

- Solution: For most chemical applications, start with a Matérn kernel (e.g., Matérn 5/2), which is a good default for modeling functions that are less smooth than those modeled by a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel [29] [3].

Issue 2: The Optimization Loop Fails to Suggest New Experiments

Problem: The acquisition function maximization step fails to return a new candidate point, or returns an error.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check for Invalid or

NaNValues:- Cause: The surrogate model's predictions (mean or variance) may be undefined in some regions, often due to numerical instability in the kernel matrix.

- Solution: Add a small "jitter" term to the diagonal of the kernel matrix during training to improve numerical conditioning.

- Protocol: In your Gaussian Process implementation, locate the parameter for jitter (often called

alphaorjitter) and set it to a small value (e.g.,1e-6).

Verify Acquisition Function Configuration:

- Cause: The acquisition function may be overly exploitative and get stuck on a flat peak.

- Solution: For the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) function, increase the

kappaparameter to give more weight to uncertainty (exploration). For Expected Improvement (EI), ensure the implementation correctly handles the trade-off [28]. - Protocol: Re-run the optimization for a few iterations with a higher

kappa(e.g., 5 or 10) and observe if the algorithm begins to suggest more diverse experiments.

Issue 3: Optimization Performance is Inefficient with Large Batch Sizes

Problem: The time to select a new batch of experiments becomes prohibitively long, or the quality of batch suggestions decreases.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Use Scalable Acquisition Functions:

- Cause: Some multi-objective acquisition functions, like

q-EHVI, have computational complexity that scales exponentially with batch size (q). - Solution: For large-scale High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) with batch sizes of 96 or more, switch to more scalable acquisition functions like

q-NParEgo, Thompson sampling with hypervolume improvement (TS-HVI), orq-NEHVI[2]. - Protocol: Benchmark the computation time of your current acquisition function against

q-NParEgofor a batch size of 96 on a test problem to quantify the improvement.

- Cause: Some multi-objective acquisition functions, like

Consider Alternative Algorithms for High-Dimensional Spaces:

- Cause: Standard Gaussian Processes struggle with high dimensionality (>20 parameters).

- Solution: For very high-dimensional search spaces, consider using alternative surrogate models like Random Forests or Bayesian Neural Networks, which may be more computationally efficient [3].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing a Robust Initial Sampling Strategy

This protocol outlines the steps for generating an initial dataset using Sobol sequences [2].

- Define Parameter Space: Establish the bounds for all continuous parameters (e.g., temperature: 25°C - 150°C) and the list of all categorical parameters (e.g., solvent A, B, C).

- Generate Sobol Sequence: Use a library like

SciPyorSALibto generate a Sobol sequence of points within a hypercube of [0, 1]^d, wheredis the total number of parameters (continuous and categorical combined after encoding). - Scale to Parameter Bounds: Map the generated points from the [0,1] hypercube to the actual bounds of your continuous parameters.

- Encode Categorical Variables: Convert categorical variables into numerical descriptors (e.g., one-hot encoding). The Sobol sequence should be generated for this entire, encoded parameter space.

- Select Batch: The first

Npoints from the scaled and encoded sequence constitute your initial experimental batch.

Protocol 2: A Standard Bayesian Optimization Iteration

This protocol details the core loop for updating the model and suggesting new experiments [29] [3].

- Train Surrogate Model: Using all available data (initial design + previous iterations), train a Gaussian Process regressor. The model will learn a probabilistic mapping from input parameters to the objective function(s).

- Construct Acquisition Function: Define an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, UCB) that uses the GP's posterior (mean and variance) to quantify the utility of evaluating any new point.

- Maximize Acquisition Function: Find the point (or batch of points) that maximizes the acquisition function. This is a numerical optimization problem, often solved with techniques like L-BFGS or multi-start optimization.

- Run Experiment: Execute the experiment(s) with the suggested parameter set(s) and measure the outcome(s).

- Update Dataset: Append the new {parameters, outcome} pair to the historical dataset.

- Check Convergence: Evaluate against your stopping criteria. If not met, return to Step 1.

Quantitative Comparison of Sampling Methods

The table below summarizes findings on sampling methods for initial design and sensitivity analysis [30].

| Sampling Method | Key Principle | Convergence Speed | Reproducibility | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sobol Sequences | Low-discrepancy deterministic sequence | Faster | High (Deterministic) | Initial design for BO; Global sensitivity analysis |

| Latin Hypercube (LHS) | Stratified sampling from equiprobable intervals | Medium | Low (Stochastic) | Initial design for BO |

| Random Sampling | Independent random draws | Slower | Low (Stochastic) | General baseline |

Characteristics of Common Acquisition Functions

The table below compares acquisition functions used to guide the optimization [28] [3].

| Acquisition Function | Exploration/Exploitation Balance | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Balanced | Tends to be a robust, general-purpose choice. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Tunable (via kappa parameter) |

Explicitly tunable; high kappa favors exploration. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | More exploitative | Can get stuck in local optima more easily. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table lists essential computational "reagents" for constructing a Bayesian optimization pipeline in chemical research.

| Tool / Component | Function in the Pipeline | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sobol Sequence | Initial Design | Generates a space-filling initial batch of experiments to build the first surrogate model [2]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | Surrogate Model | A probabilistic model that approximates the unknown objective function and provides uncertainty estimates [29] [3]. |

| Matérn Kernel | Model Kernel for GP | Defines the covariance structure in the GP; a standard choice for modeling chemical functions [29]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Acquisition Function | Suggests the next experiment by balancing high performance (exploitation) and high uncertainty (exploration) [28] [3]. |

| Variational GP Classifier | Constraint Modeling | Models the probability of an experiment being feasible (e.g., successful synthesis) when handling unknown constraints [29]. |

| q-NEHVI | Multi-Objective Acquisition Function | Efficiently selects batches of experiments to approximate the Pareto front for multiple objectives [2]. |

| Tri(Azide-PEG10-NHCO-ethyloxyethyl)amine | Tri(Azide-PEG10-NHCO-ethyloxyethyl)amine, MF:C81H159N13O36, MW:1891.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5,7,8-Trihydroxy-6-methoxy flavone-7-O-glucuronideb | 5,7,8-Trihydroxy-6-methoxy flavone-7-O-glucuronideb, MF:C22H20O12, MW:476.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete optimization pipeline, integrating the components and troubleshooting points discussed above.

Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The diagram below details the internal process of the "Train Surrogate Model" and "Construct Acquisition Function" steps, showing how the probabilistic model guides the selection of new experiments.

Model Update and Suggestion Logic

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) as an Ideal Partner for BO

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) uses automated, miniaturized, and parallelized workflows to rapidly execute vast numbers of chemical experiments [2] [32]. When paired with Bayesian Optimization (BO)—a machine learning method that efficiently finds the optimum of expensive "black-box" functions—a powerful, synergistic cycle is created [33]. BO intelligently selects which experiments to run next by balancing the exploration of unknown conditions with the exploitation of promising results [3]. HTE provides the automated means to execute these suggested experiments in parallel, generating high-quality data that BO uses to refine its model and suggest the next optimal batch [2] [32]. This partnership is transforming reaction optimization in fields like pharmaceutical development, allowing scientists to navigate complex chemical landscapes with unprecedented speed and efficiency [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental and Computational Challenges

Poor Optimization Performance or Slow Convergence

| Problem Area | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Sampling | Algorithm takes many iterations to find promising regions; gets stuck in local optima. | Initial dataset is too small or not diverse enough to build an accurate initial surrogate model [2]. | Use quasi-random sampling (e.g., Sobol sequences) for the initial batch to maximize coverage of the reaction condition space [2]. |

| Acquisition Function | Slow progress in multi-objective optimizations (e.g., yield and selectivity) with large batch sizes. | The acquisition function does not scale efficiently to large parallel batches (e.g., 96-well plates) and multiple objectives [2]. | Switch to scalable multi-objective acquisition functions like q-NParEgo, TS-HVI, or q-NEHVI [2]. |

| Search Space Definition | Algorithm suggests impractical or unsafe conditions (e.g., temperatures above a solvent's boiling point). | The search space includes too many implausible or invalid combinations of parameters [2]. | Pre-define the space as a discrete set of plausible conditions and implement automatic filters to exclude unsafe combinations [2]. |

Handling Complex Chemical Spaces and Data Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical Variables | The model performs poorly when selecting between different ligands, solvents, or catalysts. | Categorical variables (e.g., solvent type) are not properly encoded for the ML model, creating a complex, high-dimensional space with isolated optima [2]. | Use numerical descriptors for molecular entities and employ surrogate models (e.g., Gaussian Processes) that can handle mixed variable types [2] [33]. |

| Noisy or Sparse Data | Model predictions are inaccurate and do not match subsequent experimental results. | Experimental noise is high, or the available historical data is sparse, low-quality, or not relevant to the current optimization [32] [33]. | Use noise-robust models like Gaussian Processes with built-in noise estimation. For sparse data, employ multi-task learning or transfer learning to leverage related datasets [3]. |

| Platform Integration | Difficulty translating BO recommendations into automated experiments on the HTE platform. | A technical barrier exists between the BO software and the robotic control systems of the HTE platform [32]. | Implement or use control software (e.g., Summit [3]) capable of translating model predictions into machine-executable tasks and workflows [32]. |

Workflow for HTE-BO Reaction Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative workflow of a Bayesian Optimization campaign guided by High-Throughput Experimentation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: What makes HTE and BO such a powerful combination? HTE generates large, consistent datasets through automation, but exploring vast chemical spaces exhaustively is intractable. BO reduces the experimental burden by intelligently selecting the most informative experiments to run. This creates a synergistic cycle: BO guides HTE, and HTE provides high-quality data for BO, dramatically accelerating the optimization process [2] [32].

Q2: My reaction has multiple goals (e.g., high yield, low cost, good selectivity). Can BO handle this? Yes. This is known as multi-objective optimization. Advanced BO frameworks use acquisition functions like q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) to identify a set of optimal conditions (a "Pareto front") that represent the best trade-offs between your competing objectives [2] [3].

Q3: What is "generality-oriented" BO and why is it important in pharmaceutical development? Traditional BO finds optimal conditions for a single reaction. Generality-oriented BO aims to find a single set of reaction conditions that performs well across multiple related substrates [27]. This is crucial in drug development, where optimizing conditions for every single molecule is infeasible. It frames the problem as optimizing over a "curried function," requiring the algorithm to recommend both a condition set and a substrate to test in each cycle [27].

Technical Implementation

Q4: What are the key components of a Bayesian Optimization algorithm? A BO algorithm has two core components:

- Surrogate Model: A probabilistic model (most often a Gaussian Process) that approximates the unknown objective function (e.g., reaction yield) and provides predictions with uncertainty estimates [3] [33].

- Acquisition Function: A utility function (e.g., EI, UCB, q-NEHVI) that uses the surrogate's predictions to balance exploration and exploitation, deciding the next best experiments to run [3] [33].

Q5: How do I choose an acquisition function for my HTE campaign? The choice depends on your campaign's goals and scale:

- For large-scale, multi-objective HTE (e.g., 96-well plates), use scalable functions like q-NParEgo or Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI) [2].

- For smaller, single-objective campaigns, Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) are standard choices [3].

- Benchmarking on emulated virtual datasets before starting wet-lab experiments can help select the best performer for your specific problem [2].