Bioanalytical Method Transfer for Chromatographic Assays: A Comprehensive Guide to Strategies, Validation, and Troubleshooting

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the successful transfer of bioanalytical chromatographic methods.

Bioanalytical Method Transfer for Chromatographic Assays: A Comprehensive Guide to Strategies, Validation, and Troubleshooting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the successful transfer of bioanalytical chromatographic methods. It covers the foundational principles and regulatory requirements, explores practical transfer methodologies including comparative testing and covalidation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and details the critical process of validation and cross-validation. The content synthesizes current best practices and regulatory expectations to ensure data integrity, accelerate drug development timelines, and maintain compliance in regulated bioanalysis.

Understanding Bioanalytical Method Transfer: Core Principles and Regulatory Landscape

Defining Analytical Method Transfer (AMT) in a GxP Environment

Analytical Method Transfer (AMT) is a documented process that verifies a validated analytical procedure performs consistently and reliably in a different laboratory, known as the "receiving laboratory," matching the performance of the original "sending laboratory" [1] [2]. In the highly regulated GxP environment, AMT provides the critical evidence required by agencies like the FDA and EMA that an analytical method remains robust and reproducible when executed by different analysts, using different equipment, and in a different location [1]. This process is foundational to ensuring drug product quality and patient safety, especially when manufacturing is transferred to a new facility or when testing is outsourced to partner labs [1] [3].

The Fundamentals of Analytical Method Transfer

The core principle of AMT is to demonstrate equivalency between two laboratories. It is not a re-invention of the method but a confirmation that the existing, validated method works as intended in a new setting [1] [2]. This is distinct from method validation; validation proves a method is suitable for its intended purpose, while transfer proves it can be executed equivalently in a new environment [1].

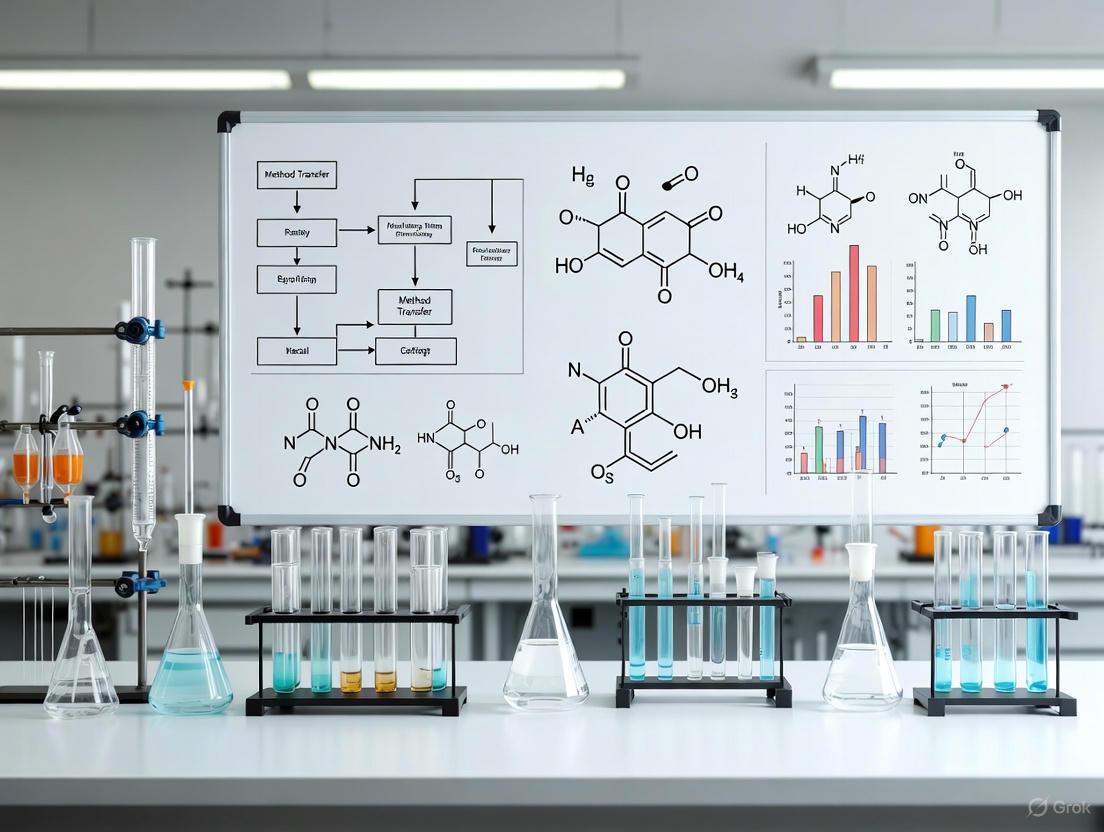

A successful transfer follows a structured, pre-defined path. The diagram below outlines the key stages in the AMT lifecycle, from initial planning to regulatory filing.

Comparison of AMT Approaches

The strategy for transferring a method is not one-size-fits-all. Based on a risk assessment that considers the method's complexity and criticality, different transfer protocols can be applied [1] [4] [5]. The following table compares the four primary types of analytical method transfer.

| Transfer Type | Description | Typical Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [1] [2] [4] | Both labs analyze identical samples from the same lot(s). Results are statistically compared against pre-defined acceptance criteria. | Most common approach; used for critical methods. | Provides direct, quantitative evidence of equivalency. | Requires significant resources and coordination between labs. |

| Co-Validation [1] [4] [6] | The receiving lab participates in the original method validation studies, providing reproducibility data. | Useful for new or complex methods destined for multi-site use. | Establishes shared ownership and understanding from the start. | Requires early involvement of the receiving lab, which is not always possible. |

| Re-Validation [1] [5] [6] | The receiving lab performs a partial or full validation of the method. | Applied when there are significant differences in equipment or lab environment, or if the originating lab is unavailable. | Does not require parallel testing with the sending lab. | Resource-intensive for the receiving lab; essentially repeats validation work. |

| Transfer Waiver [4] [5] [6] | A formal transfer is omitted based on a justified risk analysis. | Suitable for simple compendial methods (e.g., USP) or when personnel transfer with the method. | Saves time and resources. | Requires robust, documented justification for regulatory acceptance. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Transfer

For a Comparative Testing transfer—the most common protocol—the experiment is executed according to a tightly controlled and pre-approved protocol.

Detailed Methodology: Comparative Testing Protocol

- Sample Selection and Preparation: A single, homogeneous lot of the drug substance or product is typically used to ensure that variability stems from the analytical method itself, not the product [5]. The samples are split and distributed to both the sending and receiving laboratories.

- Parallel Analysis: Both laboratories analyze the samples using the identical, validated analytical procedure. A typical design may include multiple assay parameters (e.g., assay, impurities) and replicate analyses (e.g., n=6) to adequately assess precision [1] [7].

- System Suitability: Both labs must first demonstrate that the analytical system is performing adequately by meeting all system suitability criteria outlined in the method prior to data acquisition [2].

- Data Comparison and Statistical Analysis: The resulting data from both labs are compared using statistical tools. A total error approach is increasingly recommended, which combines accuracy and precision into a single criterion based on an allowable out-of-specification (OOS) rate, overcoming the difficulty of setting separate criteria for precision and bias [7]. Common comparisons include:

- Assay/Potency: Comparison of means using a t-test or equivalence test (e.g., 90% or 95% confidence interval for the difference should fall within ±2.0%) [7].

- Impurity Results: Comparison of means for each specified impurity.

- Content Uniformity: Comparison of means and standard deviations (or variances) [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of an AMT, particularly for chromatographic assays, depends heavily on the quality and consistency of key reagents and materials [1] [2].

| Material/Reagent | Critical Function in AMT | Considerations for Success |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard [2] | Serves as the primary benchmark for quantifying the analyte and establishing the calibration curve. | Use the same lot and supplier for both labs to eliminate variability. If not possible, the receiving lab must carefully qualify their standard against the sending lab's [2]. |

| Chromatographic Column [1] | The stationary phase where the critical separation of analytes occurs. | Specify the exact brand, chemistry, dimensions, and particle size. Different column lots can exhibit variations in performance [1]. |

| Critical Reagents (e.g., buffers, ion-pairing agents) [1] | The mobile phase components that directly impact retention time, peak shape, and resolution. | Standardize the grade, supplier, and preparation SOPs. Slight differences in pH or buffer concentration can significantly alter results [1] [2]. |

| Sample Matrix | The biological fluid (e.g., plasma, serum) or placebo formulation in which the analyte is dissolved. | Use the same matrix source (e.g., human plasma from a single lot) or a well-defined synthetic placebo to ensure consistency in sample preparation and analysis [6]. |

| HTH-02-006 | HTH-02-006, MF:C25H29IN6O3, MW:588.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KDOAM-25 | KDOAM-25, MF:C15H25N5O2, MW:307.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Navigating AMT Challenges and the Modern Lifecycle Approach

Despite clear guidelines, laboratories face practical challenges during AMT. Common issues include instrument variability (model, age, calibration), reagent/column variability, differences in analyst technique, and environmental conditions [1] [2]. Mitigation strategies include conducting a thorough risk assessment, ensuring equipment equivalency, standardizing materials, and providing comprehensive, hands-on training for analysts [1] [2].

The landscape of AMT is evolving with the adoption of ICH Q14 and the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle (APL) concept [8]. This paradigm shift moves methods from a static, one-time validation to a dynamic, knowledge-managed system. Key to this approach is defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)—a predefined objective for the method's performance—and establishing a Method Operable Design Region (MODR), which is the combination of analytical parameter ranges within which the method performs as expected [8]. Changes within the MODR do not require regulatory re-approval, offering greater flexibility and simplifying post-transfer changes.

By understanding the fundamental principles, choosing the appropriate transfer strategy, meticulously executing experimental protocols, and embracing a modern, lifecycle-oriented mindset, organizations can ensure robust, compliant, and successful analytical method transfers. This ultimately safeguards product quality and accelerates the delivery of therapies to patients [1] [2] [8].

Analytical method transfer is a formally documented process that qualifies a laboratory (the receiving laboratory) to use a validated analytical test procedure that originated in another laboratory (the sending or transferring laboratory) [9]. The primary goal is to ensure that the analytical method continues to perform in its validated state regardless of the change in testing location, thereby guaranteeing the reliability and consistency of data crucial for pharmaceutical development and quality control [10]. This process is fundamental in the lifecycle of a bioanalytical method, ensuring that when methods move—whether from development to quality control, between sites within a company, or to external contract laboratories—data generated remains accurate, precise, and reproducible. A successful transfer hinges on clear communication and a well-defined understanding of the distinct duties assigned to the sending and receiving laboratories [11].

Comparative Roles and Responsibilities

The collaboration between the sending and receiving laboratories is a structured partnership where each party has specific, critical responsibilities. The table below summarizes these key roles for easy reference.

Table 1: Core Responsibilities of Sending vs. Receiving Laboratory

| Area of Responsibility | Sending Laboratory | Receiving Laboratory |

|---|---|---|

| Documentation & Knowledge Transfer | Provides comprehensive method documentation, validation reports, and historical data [11] [5]. | Reviews all provided data for feasibility; identifies gaps or needs for training [11]. |

| Protocol & Report Development | Typically drafts the method transfer protocol, defining objectives and acceptance criteria [11]. | Reviews and approves the protocol; executes the study and drafts the final transfer report [11] [5]. |

| Training & Technical Support | Provides necessary training, which may include on-site sessions for complex methods [11] [12]. | Ensures staff are properly trained and qualified to execute the method [5] [10]. |

| Materials & Equipment | Provides reference standards, test samples, and details on critical reagents [5]. | Verifies availability of required equipment; ensures it is qualified and properly calibrated [5]. |

| Experimental Execution | May analyze pre-determined sample sets for comparative testing [11] [12]. | Perishes the analytical method as per the protocol on a homogeneous lot of material [11] [5]. |

| Communication | Proactively shares tacit knowledge, practical tips, and risk assessments [11]. | Maintains open communication, promptly raising issues or deviations encountered [11] [13]. |

The Sending Laboratory's Role

The sending laboratory acts as the source of truth for the analytical method. Its primary responsibility is the complete and transparent transfer of all technical and scientific knowledge related to the method [11]. This begins with providing the receiving unit with the detailed analytical procedure, the formal validation report, and information on the quality of reference standards and reagents [11] [5]. Crucially, their role extends beyond sharing documents; they must also communicate the "tacit knowledge"—the unwritten practical tips and troubleshooting experience gained during method development and validation [11]. For instance, they might know that a specific column temperature is critical for achieving adequate resolution or that a particular reagent lot can affect sensitivity. This knowledge is often shared through kick-off meetings and, for complex methods, on-site training sessions to ensure the receiving laboratory fully understands the method's nuances [11] [12].

The Receiving Laboratory's Role

The receiving laboratory's role is one of qualification and preparation. Their first task is to conduct a gap analysis, reviewing all information from the sending laboratory to ensure they have the technical capability to perform the method [11]. This involves verifying that all required equipment is available, qualified, and properly calibrated [5]. Furthermore, the receiving lab must ensure its staff are adequately trained on the new method before the formal transfer begins [5] [10]. During the execution phase, the receiving laboratory is responsible for performing the method exactly as written, using the agreed-upon protocol and a single, homogeneous lot of the article to ensure that the comparison focuses on method performance rather than product variability [5]. They must also maintain rigorous documentation of all activities and results, which will form the basis of the final transfer report that concludes the process [11].

The Method Transfer Workflow

The process of analytical method transfer follows a logical sequence from initiation to closure, requiring close collaboration between both laboratories. The diagram below illustrates this workflow and the key responsibilities at each stage.

Diagram 1: Analytical Method Transfer Workflow

The workflow begins with the initiation of the transfer project, often triggered by a need to move testing to a new site. The first critical step is the sharing of documentation and knowledge from the sending unit to the receiving unit [11]. The receiving laboratory then performs a feasibility and gap analysis to assess their readiness and identify any needs for additional training or equipment [11] [12].

A kick-off meeting is highly recommended to align both teams, discuss the method in detail, and plan the transfer [11]. This is often where tacit knowledge is shared. Following this, a detailed transfer protocol is developed and agreed upon, defining the experimental design, acceptance criteria, and responsibilities [11] [5]. With the protocol approved, the execution phase begins, where the receiving laboratory performs the analysis, often in parallel with the sending lab for comparative transfers [12]. The resulting data is then analyzed against the pre-defined acceptance criteria, and a final report is generated to document the success (or failure) of the transfer [11]. The process concludes once the report is approved, and the receiving lab is formally qualified to use the method for its intended GMP purpose.

Experimental Data from a Multi-Platform Bioanalytical Comparison

To ground the principles of method transfer in practical research, a 2024 study provides relevant experimental data. The study directly compared the performance of four different bioanalytical assay platforms—Hybrid LC-MS, SPE-LC-MS, HELISA, and SL-RT-qPCR—for quantifying a single siRNA therapeutic (SIR-2) in a pharmacokinetic study [14]. This inter-platform comparison mirrors the challenges of an inter-laboratory transfer, where demonstrating comparable method performance is key.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Bioanalytical Platforms for siRNA Quantification [14]

| Assay Platform | Key Performance Characteristics | Observed Trend in PK Samples | Potential Cause of Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid LC-MS | High sensitivity, high specificity, potential for metabolite identification | Lower concentrations | High specificity for parent analyte only [14] |

| SPE-LC-MS | Generic reagents, shorter development time, high specificity | Lower concentrations | High specificity for parent analyte only [14] |

| HELISA | High throughput, high sensitivity | Higher concentrations | Lack of specificity; may detect metabolites [14] |

| SL-RT-qPCR | Highest throughput, highest sensitivity | Higher concentrations | Lack of specificity; may detect metabolites [14] |

Experimental Protocol

The methodology for this comparative study was as follows [14]:

- Analyte: A 21-mer lipid-conjugated siRNA therapeutic (SIR-2).

- Sample Matrix: Control Kâ‚‚EDTA plasma.

- Study Design: Samples from a pre-clinical pharmacokinetic study were analyzed by all four developed methods.

- Methodologies:

- Hybrid LC-MS & SPE-LC-MS: Used mobile phases containing 0.1% (v/v) N-Dimethylbutylamine (DMBA) and 0.5% (v/v) hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP). An analog siRNA (ISTD-3) was used as an internal standard.

- HELISA: Utilized locked nucleic acid (LNA) capture probes and a ruthenium-labeled anti-digoxigenin antibody for detection.

- SL-RT-qPCR: All reagents were part of commercially available kits, with custom-synthesized primers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Bioanalytical Method Transfer

The successful execution of a method transfer relies on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The table below lists essential items and their functions based on the featured study and general practice.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioanalytical Transfers

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Analytical Workflow |

|---|---|

| Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) Probes | Synthetic nucleic acid analogs used in HELISA and Hybrid LC-MS to specifically capture and enrich the target oligonucleotide, improving sensitivity and specificity [14]. |

| Stem-Loop RT-qPCR Primers | Specialized primers that improve the efficiency of reverse transcription for short RNA targets like siRNA, enabling highly sensitive quantification via PCR [14]. |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents (e.g., DMBA) | Chromatographic additives used in LC-MS mobile phases to facilitate the separation and detection of negatively charged oligonucleotides by interacting with their phosphate backbone [14]. |

| Analog Internal Standard (e.g., ISTD-3) | A structurally similar but non-identical molecule added to samples in LC-MS assays to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency [14]. |

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized samples of the analyte used to prepare calibration curves and quality control samples, ensuring the accuracy and traceability of the quantitative results [5]. |

| Critical Biological Reagents | Items such as enzymes (e.g., proteinase K), antibodies, and magnetic beads, which are essential for specific binding, capture, or sample digestion steps in various assay formats [14]. |

| GNE-3511 | GNE-3511, CAS:162112-43-8, MF:C23H26F2N6O, MW:440.5 |

| Pegnivacogin | Pegnivacogin|Factor IXa Inhibitor|Research Use Only |

A successful analytical method transfer is not an isolated event but the result of a meticulously managed collaboration where the sending laboratory acts as the knowledge repository and the receiving laboratory as the qualified implementer. As demonstrated by the comparative bioanalytical data, different methodologies can yield varying results based on their inherent principles, underscoring the need for a controlled and well-understood transfer process. The entire endeavor relies on a foundation of exhaustive documentation, proactive and open communication, and a shared commitment to data integrity. By clearly defining and adhering to their respective roles and responsibilities, laboratories can ensure that analytical methods remain robust, reliable, and in a state of control throughout their lifecycle, thereby safeguarding product quality and patient safety.

In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, Analytical Method Transfer (AMT) has emerged as a critical business process that ensures analytical methods perform consistently and reliably when transferred from one laboratory to another. The objective of a formal method transfer is to guarantee that the receiving laboratory is thoroughly trained, qualified to run the method, and achieves the same results—within experimental error—as the initiating laboratory [15]. This process establishes documented evidence that the analytical method works as effectively in the receiving laboratory as in the originator's facility, qualifying the receiving laboratory to produce Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) "reportable data" [15].

The business case for AMT extends far beyond mere regulatory compliance. In an era of outsourcing and complex global supply chains, AMT serves as a strategic enabler for operational efficiency, cost reduction, and accelerated drug development. The practice of outsourcing bioanalytical methods from laboratory to laboratory has increasingly become a crucial strategy for successful and efficient delivery of therapies to the market [16]. For generic drug development specifically, technological advancements are profoundly reshaping the development lifecycle, leading to accelerated timelines, significant cost reductions, and enhanced product quality [17]. This article examines the business case for AMT through the lenses of outsourcing efficiency, technological advancement, and strategic drug development optimization.

AMT Methodologies and Transfer Protocols

Core AMT Approaches

The selection of an appropriate AMT strategy depends on the stage of method development, the complexity of the method, and the experience of the personnel involved [15]. There are several well-established approaches to conducting analytical method transfers, each with distinct applications and advantages.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of AMT Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Description | Typical Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing | Both laboratories perform a preapproved protocol testing identical samples, with results compared against predetermined acceptance criteria [15] [6]. | Late-stage methods; transfer of complex methods; post-approval situations involving additional manufacturing sites or contract laboratories [15]. | Most common and straightforward approach; provides direct performance comparison; comprehensive assessment. |

| Covalidation | The receiving laboratory participates in the original validation of the method, conducting intermediate precision experiments to generate reproducibility data [15] [6]. | When GMP testing requires multiple laboratories; during initial method validation phases [6]. | Eliminates separate transfer exercise; more efficient; builds method ownership in receiving laboratory. |

| Method Validation/Revalidation | The receiving laboratory repeats some or all of the originating laboratory's validation experiments [15]. | When originating laboratory is unavailable; significant changes in method or instrumentation [6]. | Comprehensive understanding of method performance; demonstrates receiving laboratory proficiency. |

| Transfer Waiver | Formal transfer process is waived based on receiving laboratory's existing experience with similar methods [15] [6]. | Compendial methods (USP, EP); laboratory already testing similar products; transfer of personnel with method expertise [15]. | Saves time and resources; leverages existing capabilities; appropriate for low-risk transfers. |

Experimental Design and Acceptance Criteria

A successful AMT requires a preapproved test plan protocol that details all aspects of the transfer exercise. This document typically takes the form of a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) specific to the product and method [15]. The protocol must clearly define:

- Scope and Objectives: The specific methods, products, and laboratories involved in the transfer [15].

- Materials and Samples: Representative, homogeneous samples identical for both laboratories, typically pre-GMP materials or "control lots" to avoid triggering out-of-specification (OOS) investigations [15].

- Instrumentation and Parameters: Description of equipment and associated parameters, with consideration given to instrument differences between laboratories [15].

- System Suitability: Established parameters that the method must meet before transfer testing can begin [15].

- Acceptance Criteria: Predetermined statistical criteria for evaluating results, often including means, standard deviations, F-tests, or t-tests [15].

Table 2: Example Experimental Design and Acceptance Criteria for AMT

| Analytical Parameter | Experimental Design | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Assay and Impurities | Two analysts in receiving lab; one lot in triplicate; compare to original lab data [15]. | 95-105% of original lab results; RSD ≤3% for assay [15]. |

| Content Uniformity | Two analysts in receiving lab; 30 units from one lot; compare to original lab data [15]. | 90-110% of original lab results; RSD ≤6% [15]. |

| Dissolution | Six units from one lot by two analysts in receiving lab; compare to original lab profile [15]. | Similar dissolution profile; difference factor f2 ≥50 [15]. |

The AMT process culminates in a comprehensive transfer report that certifies whether acceptance criteria were met and the receiving laboratory is fully qualified to run the method. This report summarizes all experiments, results, instrumentation used, and any observations made during the transfer [15].

The Outsourcing Imperative: Strategic Business Advantages of AMT

Cost Efficiency and Resource Optimization

The business case for AMT in outsourcing scenarios is compelling from a financial perspective. Partnering with specialized contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) and contract research organizations (CROs) eliminates the need for substantial capital investments in production equipment and facilities [18]. These significant upfront investments have already been made by the contract organizations, allowing pharmaceutical companies to convert fixed costs into variable costs and maintain financial flexibility [18].

The economic value is particularly pronounced in the generic drug sector, where companies frequently operate with razor-thin profit margins and face intense market pressures [17]. Technological advancements, including those in analytical methodologies, are proving critical for maintaining economic viability in this sector. The substantial cost reductions (up to 40% in drug discovery) and timeline accelerations (up to 70% in development) achievable through advanced approaches represent a vital mechanism for generic companies to sustain operations and capture market share [17].

Focus on Core Competencies and Speed to Market

AMT enables pharmaceutical companies to concentrate internal resources on core competencies such as research and development, innovation, and strategic planning. By outsourcing analytical operations to specialized laboratories, companies can accelerate development timelines and bring products to market faster [18]. This speed-to-market advantage represents a significant competitive edge in an industry where patent protection periods are finite.

The streamlined operations facilitated by effective AMT processes allow medical device and pharmaceutical companies to optimize their supply chain logistics and decrease risks associated with regulatory compliance and quality control [18]. As one contract manufacturer highlights, their comprehensive approach to contract manufacturing allows clients to "concentrate on their core competencies, such as product development, marketing, and sales" without the need to establish and maintain their own manufacturing lines [18].

Access to Specialized Expertise and Technologies

Outsourcing analytical methods through formal transfer protocols provides access to a broader range of skilled professionals and leading-edge technologies that might not be available internally [18]. This access is particularly valuable for complex analytical techniques such as chromatographic-based assays, which require specialized expertise and instrumentation [16] [6].

The field of chromatography continues to evolve rapidly, with recent innovations including:

- AI-powered instrumentation that automates calibration and optimizes system performance [19]

- Micropillar array columns featuring lithographically engineered elements that ensure uniform flow paths [19]

- Microfluidic chip-based columns that replace traditional resin-based columns for exceptional scalability [19]

- Biocompatible/inert columns with passivated hardware to prevent adsorption of metal-sensitive analytes [20]

These technological advancements enable more precise, efficient, and reliable analytical methods, but require significant investment and expertise to implement effectively.

Technological Innovations Enhancing AMT Efficiency

Artificial Intelligence and Automation in Chromatography

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is transforming chromatographic practices, including method transfer processes. AI algorithms are now being employed to automate calibration, optimize system performance, and enhance data analysis [19]. The global AI in pharmaceutical market is valued at $1.94 billion in 2025 and is forecasted to reach approximately $16.49 billion by 2034, demonstrating a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 27% [17].

Vendors are responding to demands for greater uptime and cost efficiency by incorporating AI directly into instrumentation and workflow design [19]. This technological evolution supports more reliable method transfers by reducing human error and variability between laboratories. Standardized, preconfigured chromatography setups further simplify operation, reducing errors and enabling quicker adoption even by novice users [19].

Advanced Column Technologies

Recent innovations in liquid chromatography columns have significant implications for method transfer success and reliability. The 2025 review of new HPLC columns reveals several trends directly impacting AMT:

Small Molecule Reversed-Phase Columns: New stationary phases with advanced particle bonding and hardware technology enhance peak shapes, improve column efficiency, extend usable pH ranges, and provide improved selectivity [20]. Examples include the Halo 90 Ã… PCS Phenyl-Hexyl column with enhanced peak shape for basic compounds [20], and the SunBridge C18 column with exceptional pH stability (pH 1-12) [20].

Biocompatible/Inert Columns: The trend toward columns with inert hardware continues to address challenges with metal-sensitive analytes [20]. Products like the Halo Inert column integrate passivated hardware to create a metal-free barrier, particularly advantageous for phosphorylated compounds and metal-sensitive analytes [20]. These advancements improve analyte recovery and peak shape, critical factors in successful method transfer.

Specialized Columns for Complex Analyses: New columns designed specifically for challenging separations such as oligonucleotides, proteins, and complex biomolecules are entering the market [20]. The Evosphere C18/AR column, for instance, is suited for oligonucleotide separation without ion-pairing reagents [20].

Cloud Integration and Remote Monitoring

Cloud integration is transforming how chromatographers engage with their instruments, enabling remote monitoring, seamless data sharing, and consistent workflows across global sites [19]. This capability is particularly valuable for AMT activities involving multiple laboratories in different locations. Cloud-based solutions enhance flexibility and collaboration while maintaining data integrity and security.

User-friendly interfaces, including touchscreens, further simplify system control and improve accessibility for personnel of varying expertise levels [19]. This accessibility reduces the training burden during method transfers and facilitates more consistent implementation across sites.

The Regulatory Landscape and Quality Assurance

FDA's Advanced Manufacturing Technologies Designation Program

In December 2024, the FDA finalized its guidance on the Advanced Manufacturing Technologies (AMT) Designation Program, creating a structured pathway for adopting innovative manufacturing technologies [21] [22]. This program aims to facilitate early adoption of AMTs that have the potential to benefit patients by improving manufacturing and supply dependability and optimizing development time of drug and biological products [21].

While distinct from Analytical Method Transfer, the AMT Designation Program shares the overarching goal of enhancing manufacturing and analytical processes in the pharmaceutical industry. The program provides a formal mechanism for FDA recognition of novel technologies that substantially improve manufacturing processes while maintaining or enhancing drug quality [22]. This initiative reflects the regulatory emphasis on technological innovation as a means to address challenges such as drug shortages and quality issues.

Quality Assurance in Analytical Methods

Quality assurance is woven into every aspect of the method transfer process, from initial development through transfer and implementation [6]. Regulatory agencies demand stringent criteria for method validation to ensure the accuracy and reliability of data generated [6]. A successful AMT provides documented evidence that the receiving laboratory can consistently generate reliable results that meet established quality standards.

The foundation of a successful AMT is a properly developed and validated method, with robust robustness studies serving as a development and validation cornerstone [15]. As emphasized in chromatography publications, "the development and validation of robust methods and strict adherence to well documented standard operating procedures is the best way to ensure the ultimate success of the method" [15].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic Assays

Successful method transfer of chromatographic-based assays requires careful attention to critical reagents and materials. The following table outlines key research reagent solutions and their functions in bioanalytical method transfer.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic-Based Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantification of target analytes; method calibration [6]. | Purity, stability, proper storage; certificate of analysis [15]. |

| Critical Reagents | Antibodies, enzymes, or other specialized reagents used in sample preparation or analysis [6]. | Lot-to-lot consistency; stability documentation; predefined acceptance criteria [6]. |

| Mobile Phase Components | Chromatographic separation of analytes [20]. | pH, buffer concentration, organic modifier; stability and shelf-life [20]. |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitor method performance during validation and transfer [6]. | Representative matrix; low, medium, high concentrations; cover calibration range [6]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample cleanup and analyte concentration [16]. | Recovery efficiency; selectivity; lot-to-lot reproducibility [16]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enhance detection of low-response analytes [23]. | Reaction efficiency; stability; completeness of reaction [23]. |

Workflow Visualization of AMT Process

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive analytical method transfer process from initiation through completion, including key decision points and documentation requirements.

Diagram 1: Analytical Method Transfer Workflow (32.4KB)

Method Transfer Experimental Protocol

The experimental protocol for a typical comparative testing approach, the most common AMT option, involves method-specific steps but follows a consistent structure [15] [6]:

Protocol Development: Create a preapproved test plan detailing scope, objectives, responsibilities, methods, samples, instrumentation, procedures, and acceptance criteria [15].

Sample Selection and Preparation: Identify representative, homogeneous samples identical for both laboratories, typically using pre-GMP materials or "control lots" to avoid triggering out-of-specification investigations [15].

System Suitability Testing: Both laboratories demonstrate that their chromatographic systems meet predefined criteria before commencing transfer testing [15].

Method Execution: Following a standardized procedure, analysts in both laboratories analyze the predetermined number of sample replicates using identical lots and conditions [15].

Data Collection and Documentation: Both laboratories collect raw data, system suitability results, and any observations during analysis, maintaining complete documentation for all activities [15].

Statistical Comparison: Apply predefined statistical tests (e.g., means comparison, F-tests, t-tests) to evaluate whether results from both laboratories meet acceptance criteria [15].

Report Generation: Document the transfer exercise, including all experiments, results, statistical analyses, instrumentation used, and certification of receiving laboratory qualification [15].

The business case for Analytical Method Transfer rests on its role as a strategic enabler of outsourcing efficiency, technological advancement, and accelerated drug development. In an industry characterized by increasing complexity and pressure to reduce costs while maintaining quality, AMT provides the framework for reliable technology transfer between laboratories. The practice of outsourcing bioanalytical methods from laboratory to laboratory has become a crucial strategy for successful and efficient delivery of therapies to the market [16].

Companies that strategically implement AMT processes with attention to robust method development, clear protocols, and comprehensive documentation position themselves to leverage the benefits of specialized external partners, access cutting-edge technologies, and optimize internal resource allocation. As technological innovations continue to transform chromatographic science and regulatory frameworks evolve to support advanced manufacturing approaches, the strategic importance of effective AMT will only increase.

The integration of AI, advanced column technologies, and cloud-based monitoring systems represents the next frontier in AMT efficiency and reliability. Forward-thinking organizations that embrace these advancements while maintaining rigorous quality standards will achieve sustainable competitive advantages in the rapidly evolving pharmaceutical landscape. Through strategic implementation of AMT principles, companies can balance the competing demands of quality, efficiency, and innovation that define success in modern drug development.

Essential Regulatory Guidelines and Compliance Requirements (FDA, EMA, USP, ICH)

In the realm of pharmaceutical research and development, bioanalytical method validation and transfer are critical processes that ensure the reliability, accuracy, and consistency of data used to support regulatory submissions. Compliance with guidelines from major regulatory bodies—including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)—provides a framework for generating credible analytical results that form the basis for regulatory decisions on drug safety and efficacy. These guidelines establish harmonized expectations that are recognized globally, increasing confidence in the accuracy of analytical results and supporting every stage of drug development and manufacturing.

The process of method transfer serves as the critical bridge connecting laboratory-developed methods to the manufacturing environment, ensuring that analytical procedures maintain their integrity and performance characteristics when transitioning between laboratories or to production settings. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the regulatory frameworks governing these processes, with a specific focus on chromatographic assays, detailing experimental protocols for compliance and offering visualization of the complex workflows involved in maintaining regulatory standards.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

The regulatory landscape for bioanalytical methods is governed by harmonized yet distinct guidelines from major international bodies. The following table provides a structured comparison of the essential guidelines applicable to bioanalytical method validation for chromatographic assays.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Key Regulatory Guidelines for Bioanalytical Methods

| Regulatory Body | Primary Guideline | Status & Date | Geographical Scope | Key Focus Areas | Legal Standing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICH | M10: Bioanalytical Method Validation | Finalized (November 2022) [24] | International (Harmonized) | Method validation for chemical & biological drugs; chromatographic & ligand-binding assays; study sample analysis [25] | Scientific guideline, harmonized regulatory expectations |

| FDA | M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis | Final (November 2022) [24] | United States | Nonclinical and clinical studies supporting regulatory submissions; validation of chromatographic and ligand-binding assays [24] | Guidance document (current thinking, not legally binding) [26] |

| EMA | ICH M10 on bioanalytical method validation | Scientific guideline (adopted ICH M10) | European Union | Chemical and biological drug quantification; validation and study sample analysis [25] | Scientific guideline, part of EU regulatory framework |

| USP | General Chapters & Reference Standards | Continuously updated | United States (Global recognition) | Quality standards; reference materials; analytical procedures; compendial methods [27] | Official compendia (legally recognized under FDCA) |

Inspection and Compliance Verification

Regulatory authorities employ various inspection mechanisms to verify compliance with established guidelines. The EMA coordinates inspections for medicines authorized under the centralized procedure, though it does not conduct inspections itself but rather requests them through national authorities in EU Member States [28]. These inspections can be either "for cause" (triggered by findings of possible non-compliance) or routine (conducted as part of surveillance programs) [28].

The FDA conducts inspections to verify compliance with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) and other regulatory requirements, with guidance documents representing the agency's current thinking on regulatory issues [26]. While these guidance documents do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities, they provide the framework for inspection criteria and compliance expectations. For bioanalytical methods, both agencies emphasize the importance of proper method validation, equipment qualification, and data integrity throughout the method lifecycle.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation and Transfer

Bioanalytical Method Validation Parameters (ICH M10/FDA/EMA)

The ICH M10 guideline provides comprehensive recommendations for validating bioanalytical methods intended for regulatory submissions. The experimental protocols must demonstrate that assays are suitable for their intended purpose through characterization of specific parameters.

Table 2: Required Experiments for Bioanalytical Method Validation per ICH M10

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Acceptance Criteria | Chromatographic Assay Specifics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy and Precision | Analyze minimum 5 replicates at 4 concentrations (LLOQ, L, M, H); 3 separate runs | Within ±15% of nominal value (±20% at LLOQ); Precision ≤15% RSD (≤20% at LLOQ) | Use of stable isotope-labeled internal standards recommended |

| Selectivity/Specificity | Test at least 6 individual matrix sources; evaluate potential interferents | Response <20% of LLOQ for interferents; <5% of internal standard | Chromatographic resolution >1.5 between analyte and closest eluting interference |

| Calibration Curve | Minimum of 6 non-zero standards; 3 separate runs | ±15% deviation from nominal (±20% at LLOQ) | Linear or weighted regression with r² >0.99 typically required |

| Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥5; accuracy and precision within ±20% | Response ≥5 times blank response; precision ≤20% RSD | Confirmed with minimum 5 replicates across multiple runs |

| Stability | Bench-top, freeze-thaw, long-term, processed sample | Within ±15% of nominal value | Evaluate in entire matrix; document storage conditions and duration |

The experimental design must include incurred sample reanalysis (ISR) to demonstrate reproducibility, where a minimum of 10% of study samples (or 50 samples, whichever is greater) should be reanalyzed to confirm method performance with actual study samples [25]. For chromatographic methods specifically, additional parameters such as carryover (assessed by injecting blank samples after high concentration standards) and hematocrit effect (for dried blood spot methods) must be evaluated.

Method Transfer Approaches and Protocols

Method transfer ensures that analytical methods maintain performance characteristics when relocated between laboratories. The transfer process must be documented in a detailed protocol outlining experimental design and acceptance criteria.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Method Transfer Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Experimental Protocol | Statistical Analysis | Acceptance Criteria | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing | Both labs analyze same set of samples (minimum 3 batches, each in triplicate) [6] | Calculation of mean, % difference, and statistical comparison (e.g., t-test) | Predefined equivalence margins (e.g., ±10% for mean comparison) | Most common approach; suitable for well-established methods |

| Covalidation | Receiving laboratory participates as part of validation team [6] | Intermediate precision experiments to assess reproducibility | Consistency with original validation data | When GMP testing requires multiple laboratories |

| Revalidation | Receiving laboratory repeats specific validation experiments [6] | Comparison with original validation data | Meeting original validation criteria | When originating laboratory unavailable; major method changes |

| Transfer Waiver | Limited verification (e.g., system suitability, key parameters) [6] | Comparison with established method characteristics | Meeting predefined verification criteria | Method already in USP-NF; personnel transfer; minimal changes |

The transfer protocol must clearly define the roles and responsibilities of both sending and receiving laboratories, the number and type of samples to be analyzed, the specific analytical procedures to be followed, and the predefined acceptance criteria that will demonstrate a successful transfer. For chromatographic methods, system suitability tests must be established to ensure the analytical system is operating properly throughout the execution of the transfer protocol.

Visualization of Regulatory Workflows

Bioanalytical Method Validation and Transfer Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for bioanalytical method development, validation, and transfer, highlighting critical decision points and regulatory requirements.

USP Standards Development and Implementation Process

The United States Pharmacopeia plays a critical role in establishing public quality standards. The following diagram outlines the USP standards development process and its integration into regulatory compliance.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of bioanalytical methods requires carefully selected reagents and reference materials that meet regulatory standards. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for chromatographic assay development and validation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bioanalytical Chromatography

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Regulatory Considerations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP Reference Standards [27] | Highly characterized specimens for qualification and quantification; method validation | Required for compendial methods; accepted by global regulators | System suitability testing; quantitative analysis; identity confirmation |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization of extraction efficiency; compensation for matrix effects | Must be well-characterized for purity and stability | LC-MS/MS bioanalysis for small molecules; pharmacokinetic studies |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance over time; validate individual runs | Should mimic study samples; prepared in same matrix | Within-run and between-run precision and accuracy assessment |

| Matrix Lots (Plasma, Serum, Blood) | Assessment of selectivity; determination of matrix effects | Minimum 6 individual sources recommended; should cover relevant populations | Selectivity/specificity testing; hemolyzed and lipemic matrix evaluation |

| Critical Reagents (Antibodies, Enzymes) | Essential components for sample processing and analysis | Require characterization and stability data; documentation of source | Ligand-binding assays; immunocapture techniques; enzymatic digestion |

USP Reference Standards are particularly critical as they are "recognized globally" and "accepted by regulators around the world," providing the foundation for analytical rigor in pharmaceutical testing [27]. These standards help reduce the risk of incorrect results that could lead to unnecessary batch failures, product delays, and market withdrawals. For non-compendial methods, internally characterized reference standards must be thoroughly documented with certificates of analysis detailing source, purification methods, and characterization data.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The regulatory landscape for bioanalytical methods continues to evolve with several emerging trends impacting compliance requirements. The ICH M10 guideline, while recently finalized, is undergoing implementation with frequently asked questions (FAQ) documents being developed to address practical considerations [25]. Regulatory transparency is increasing, as evidenced by the FDA's recent publication of over 200 complete response letters (CRLs) for drug applications from 2020-2024, providing greater insight into the agency's decision-making process [29].

The USP is transitioning to a new publication model in July 2025, consolidating official publications from 15 to 6 issues per year while maintaining the same content volume [30]. This change aims to provide "expedited publishing timelines, a regular distribution cadence and a single bi-monthly source for official content," potentially impacting how quickly new and revised standards become official.

Regulatory agencies are also increasing collaboration, as demonstrated by the upcoming December 2025 workshop jointly hosted by FDA, USP, and the Association for Accessible Medicines titled "Quality and Regulatory Predictability: Shaping USP Standards" [31]. Such initiatives aim to "increase stakeholder awareness of, and participation in, the USP standards development process, ultimately contributing to product quality and regulatory predictability."

These developments highlight the dynamic nature of the regulatory environment and emphasize the importance of continuous monitoring of guidelines and participation in stakeholder engagement opportunities to maintain compliance in bioanalytical method development, validation, and transfer activities.

In pharmaceutical research and development, the reliability of bioanalytical data is paramount. The journey of an analytical method—from its initial conception in the laboratory to its routine application in quality control—follows a defined pathway known as the method lifecycle. This comprehensive process of method development, validation, and transfer ensures that analytical procedures consistently produce reliable, accurate, and reproducible results, forming the critical backbone for decision-making in drug development [6]. A robust method lifecycle is indispensable for generating data that regulatory bodies such as the FDA and EMA can trust, ultimately supporting submissions for investigational new drugs (INDs), new drug applications (NDAs), and abbreviated new drug applications (aNDAs) [6] [32].

The inherent complexity of modern therapeutics, from small molecules to large biologics like antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), demands increasingly sophisticated bioanalytical methods [33]. This guide objectively compares the performance of different strategies and technological solutions available for navigating the method lifecycle, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the evidence needed to optimize their analytical workflows.

The Method Development Phase: Building a Robust Foundation

Method development is the crucial first stage where the analytical procedure is designed and optimized. The primary goal is to establish a reliable methodology for quantifying the analyte within a specific biological matrix, outlining everything from sample preparation and separation to detection and data evaluation [32].

Core Challenges and Strategic Comparisons

Researchers face significant challenges during method development. The selection of an appropriate internal standard (IS) is a critical decision point. Stable isotope-labeled versions of the analyte represent the gold standard, as their nearly identical chemical behavior minimizes variability during sample preparation and analysis [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Internal Standard Types for LC-MS/MS Assays

| Internal Standard Type | Key Characteristics | Impact on Assay Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Analyte | Chemically identical, differs by ≥3 amu in mass [32]. | Excellent accuracy and precision; accounts for losses and instrument variation [32]. | Isotopic purity must be high to avoid interference with the analyte [32]. |

| Structural Analogue | Nearly identical structure (e.g., differs by a methyl group) [32]. | Good performance if it undergoes the same extraction processes [32]. | May not perfectly mimic the analyte's behavior, leading to higher variability. |

| No Internal Standard | Practice common in ELISA assays [32]. | Simplifies preparation. | Lower accuracy and precision; data should be considered exploratory or semi-quantitative [32]. |

The sample preparation and analysis stage presents another layer of complexity. For High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), common issues include column deterioration, evidenced by peak shape problems and high back pressure, and mobile phase contamination, which leads to rising baselines and noise [32]. For Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), challenges are often related to optimizing mass spectrometry parameters and managing complex sample matrices [32].

The Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) Framework

A modern approach to method development involves adopting Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles. Inspired by ICH Q8 and Q9 guidelines, AQbD shifts the focus from a reactive to a proactive methodology [34]. It begins with defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP), which outlines the method's required performance characteristics, such as the intended measurement, concentration range, and acceptable uncertainty [34]. Through structured experimentation, scientists identify the method's design space—a multidimensional combination of input variables (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, gradient time) that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality [34]. Operating within the design space creates a more robust and resilient method, reducing the risk of failure during subsequent validation and transfer.

The Method Validation Phase: Demonstrating Reliability

Following development, a method must undergo rigorous validation to demonstrate its reliability and reproducibility for the intended use [32]. Validation provides evidence that the method meets predefined acceptance criteria for key parameters, giving scientists and regulators confidence in the generated data.

Key Validation Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

Validation involves testing a series of performance parameters using known standards and quality controls within the relevant biological matrix [32]. The following parameters are typically assessed:

- Accuracy and Precision: The closeness of measured values to the true value (accuracy) and the agreement between a series of measurements (precision) [32].

- Selectivity/Specificity: The ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of other components, such as metabolites or matrix interferences [32].

- Sensitivity: Defined by the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ), the lowest concentration that can be measured with acceptable accuracy and precision [32].

- Stability: The integrity of the analyte under various conditions, including during sample collection, storage, and processing [6].

Navigating Revalidation Challenges Across Species

A significant challenge in drug development is the need to revalidate methods when transitioning from preclinical studies to clinical trials or when adapting to different species. Species-specific metabolic and physiological differences can necessitate modifications to sampling procedures, analytical parameters, or the incorporation of species-specific biomarkers [35]. For instance, circulating target levels for monoclonal antibodies can vary dramatically between animal models and humans, impacting assay specificity [35]. This often requires a partial or full revalidation, extending project timelines and increasing costs [35]. Maintaining a long-term partnership with a single laboratory can mitigate these challenges by ensuring continuity and deep institutional knowledge of the method and compound [35].

The Method Transfer Phase: Ensuring Consistency Across Laboratories

Method transfer is the formal process of moving a fully developed and validated method from one laboratory (the sending unit) to another (the receiving unit), which could be an internal QC lab or an external partner like a Contract Research Organization (CRO) or Contract Development and Manufacturing Organization (CDMO) [6]. The goal is to ensure the method performs consistently and reliably in the new environment, maintaining the integrity and stability of the methods to guarantee consistent product quality throughout its lifecycle [6].

Comparing Method Transfer Approaches

Several standardized approaches exist for method transfer, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Analytical Method Transfer Strategies

| Transfer Approach | Methodology | Typical Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing | Same samples are tested by both sending and receiving labs; results are compared against predefined acceptance criteria [6]. | Most prevalent approach for standard method transfers [6]. | Provides direct, empirical data comparing lab performance. |

| Covalidation | The receiving lab becomes part of the validation team and conducts specific experiments (e.g., intermediate precision) [6]. | When GMP testing requires multiple labs from the outset [6]. | Integrates transfer into validation, potentially saving time. |

| Revalidation | The receiving laboratory re-performs parts or all of the original validation [6]. | When the originating lab is unavailable or major changes are anticipated [6]. | Provides a standalone validation package for the receiving lab. |

| Transfer Waiver | A formal waiver is granted, forgoing the need for an experimental transfer [6]. | If the receiving lab already uses an identical procedure or the method is specified in a pharmacopoeia like USP-NF [6]. | Eliminates redundant experimental work. |

The Digital Transformation of Method Transfer

Traditional, document-heavy transfer processes are a major industry bottleneck. Relying on PDFs, emails, and manual data re-entry into different Chromatography Data Systems (CDS) is inherently prone to human error, misinterpretation, and mismatched terminology [36] [37]. These manual processes lead to costly deviations, investigations, and project delays. With each delay day for a commercial therapy costing approximately \$500,000 in unrealized sales, the economic incentive for efficiency is immense [36].

A modern, digital approach is solving this old problem. Initiatives like the Pistoia Alliance Methods Hub are pioneering the use of machine-readable, vendor-neutral method exchange formats, such as the Allotrope Data Format (ADF) [36] [37]. This creates a "digital twin" of an analytical method, which can be stored in a central repository and unambiguously executed on different instrument platforms without manual transcription [37]. This digital transformation reduces transfer errors, speeds up tech transfer, and improves overall quality, ultimately accelerating a therapy's time-to-market [36] [37].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The success of a bioanalytical method hinges on the quality and appropriateness of its core components. The following table details key reagent solutions and their critical functions.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials in Bioanalytical Method Lifecycle

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Accounts for variability during sample preparation and instrument analysis in LC-MS/MS [32]. | Ideal standard has ≥3 amu mass difference from analyte and high isotopic purity to avoid interference [32]. |

| Critical Reagents (e.g., antibodies, enzymes) | Enable specific capture and detection of analytes in Ligand Binding Assays (LBAs) [33]. | Development of anti-idiotype or anti-payload antibodies can be resource-intensive and time-consuming [33]. |

| Reference Standards | Provide a known quality and purity benchmark for calibrating analytical measurements [6] [32]. | Essential for establishing calibration curves and defining the analytical method's range [32]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Monitor the method's performance and ensure ongoing reliability during sample analysis [32]. | Prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations in the relevant biological matrix to assess accuracy and precision [32]. |

Executing a Successful Transfer: Methodologies, Protocols, and Real-World Applications

In the development and application of bioanalytical assays for chromatography research, the reliable transfer of methods from one laboratory to another is a critical yet challenging endeavor. A flawed transfer can lead to discrepant results, delays in product release, and significant regulatory scrutiny [2]. Within the broader thesis on method transfer for bioanalytical assays, this guide objectively compares the four established analytical method transfer protocols. We evaluate their performance through the lens of experimental data, regulatory guidelines, and practical implementation challenges, providing a structured framework to help scientists and drug development professionals select the optimal strategy for their specific context.

The Four Primary Transfer Approaches: A Detailed Comparison

The fundamental principle of any analytical method transfer is to demonstrate that the receiving laboratory can perform a validated analytical procedure and generate results equivalent to those from the originating laboratory [2]. The choice of protocol is a risk-based decision that must be documented in a formal transfer plan [2]. The four primary approaches are detailed below.

Table 1: Comparison of the Four Primary Analytical Method Transfer Approaches

| Transfer Approach | Core Methodology | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Ideal Use Case Scenario | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [2] [1] | Both originating and receiving labs analyze identical samples; results are statistically compared. | Pre-defined limits for accuracy, precision, and system suitability; results must be statistically equivalent [2] [1]. | Transfer of critical methods for product quality assessment [1]. | Provides direct, quantitative evidence of equivalence; most common and widely accepted approach [2]. | Can be resource-intensive, requiring significant sample analysis and data comparison [2]. |

| Co-validation [2] [1] | Both laboratories collaborate from the outset, jointly performing the method validation studies. | Validation parameters (linearity, accuracy, precision) must meet pre-defined criteria from pooled data [2]. | New or complex methods being established for multi-site use from the beginning [2]. | Fosters shared ownership and deep understanding of the method; efficient for multi-site deployment [1]. | Requires extensive coordination and planning between labs from an early stage [2]. |

| Partial or Full Revalidation [2] [1] | The receiving laboratory performs a full or partial revalidation of the method without direct comparison to the originating lab's results. | Method performance parameters must meet original validation criteria or other justified standards [2]. | When the receiving lab has a high degree of confidence, different equipment, or a unique lab environment [1]. | Demonstrates the receiving lab's standalone capability; useful when originating lab data is unavailable [2]. | Does not provide direct comparability with the originating lab; can be as intensive as the original validation [2]. |

| Waiver of Transfer [2] | A formal transfer is waived under specific, justified circumstances. | Not applicable, but the rationale for the waiver must be thoroughly documented and approved [2]. | Transfer of a simple compendial method (e.g., USP) or between labs with identical equipment and cross-trained staff [2] [1]. | Saves significant time, cost, and resources where risk is demonstrably low [2]. | Requires strong, documented justification and is subject to approval by Quality Assurance [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

The success of a transfer protocol hinges on a meticulously detailed experimental design and a clear analysis of the resulting data.

Protocol for Comparative Testing

This is the most common protocol and its experimental design serves as a model for rigorous comparison [2].

- Sample Selection: A statistically appropriate number of samples from different batches (e.g., a drug product) are selected. These should cover the specification range, including low, medium, and high concentrations of the analyte[s].

- Experimental Procedure: Both the originating and receiving laboratories analyze the identical set of samples using the same validated method and standardized materials, such as the same lot of reagents and reference standards where possible [2]. The analysis should be performed over multiple days by different analysts to incorporate routine variability.

- Data Analysis: Results from both labs are compared using statistical tests. Common methods include calculating the relative difference between means, using a t-test for accuracy, and a Fisher's test (F-test) for precision [1]. The results must fall within the pre-defined acceptance criteria established in the transfer protocol.

Table 2: Example of Comparative Testing Data for an Assay Method

| Sample ID | Theoretical Concentration (µg/mL) | Originating Lab Result (µg/mL) | Receiving Lab Result (µg/mL) | Relative Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (LLOQ) | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.98 | -6.7 |

| B (Low QC) | 3.00 | 2.95 | 3.10 | +5.1 |

| C (Medium QC) | 50.00 | 49.80 | 50.50 | +1.4 |

| D (High QC) | 80.00 | 81.20 | 79.80 | -1.7 |

| E (ULOQ) | 100.00 | 98.50 | 101.30 | +2.8 |

Acceptance Criteria (Example): The mean results from the receiving laboratory should be within ±10% of the originating laboratory's mean results for each sample level. The precision (RSD) for each lab's results should be ≤5%. All system suitability parameters must be met.

Protocol for a Risk-Based Approach and Strategic Calibration Transfer

Emerging strategies focus on minimizing experimental burden without compromising predictive accuracy. A strategic calibration transfer framework can reduce calibration runs by 30–50% [38].

- Experimental Procedure: This involves iterative subsetting of calibration sets and applying optimal design criteria (D-, A-, and I-optimality). I-optimal design has been identified as the most efficient route to achieve high predictive performance with fewer experimental runs, as it minimizes the average prediction variance [38].

- Data Analysis: The predictive accuracy of models built from these minimal, optimally-selected calibration sets is compared against the full factorial model. Research demonstrates that modest, optimally selected calibration sets combined with Ridge regression and Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC) preprocessing can deliver prediction errors equivalent to full factorial designs [38]. Ridge regression has been shown to consistently outperform traditional Partial Least Squares (PLS) models, eliminating bias and halving prediction error [38].

A Decision Framework for Selecting a Transfer Approach

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate transfer method based on key project parameters.

This decision tree should be used in conjunction with a formal risk assessment, which evaluates factors such as method complexity, the analytical technique's familiarity, and the criticality of the data generated [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method transfer relies on the standardization and quality of key materials. The following table details essential reagents and materials, with a focus on LC-MS bioanalysis of small-molecule drugs in physiological matrices [39].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioanalytical LC-MS Method Transfer

| Item | Function / Purpose | Critical Considerations for Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | To identify and quantify the target analyte(s); used for calibration. | Use the same lot number or a certified standard traceable to the original. Purity and stability are paramount [2]. |

| Internal Standards | To correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response. | Ideally, use a stable isotope-labeled analog of the analyte. Must be co-eluting and show consistent recovery with the analyte [39]. |

| Biological Matrix | The sample material (e.g., plasma, urine) in which the analyte is measured. | Source (species), anticoagulant (for plasma), and storage conditions must be consistent. Matrix effects from different lots should be evaluated [39]. |

| Sample Extraction Sorbents | To clean up the sample and extract the analyte (e.g., SPE cartridges, 96-well plates). | Sorbent chemistry (e.g., C18, mixed-mode), lot-to-lot variability, and retention capacity must be equivalent between labs [2] [39]. |

| LC Chromatography Column | To separate the analyte from matrix interferences. | Specify brand, dimensions, particle size, and pore size. Use columns from the same manufacturer and lot, if possible, to ensure identical selectivity [2]. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents & Buffers | The liquid medium that carries the sample through the LC system. | Use the same grades of solvents, buffer salts, and pH. Minor variations in pH or ionic strength can significantly alter retention times and separation [2]. |

| ONO-7579 | ONO-7579 | Chemical Reagent |

| Nvs-bptf-1 | Nvs-bptf-1, MF:C26H28FN7O3S, MW:537.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Selecting the appropriate transfer approach is not a one-size-fits-all process but a strategic decision based on method criticality, risk, and operational constraints. Comparative testing remains the gold standard for critical methods, providing robust evidence of equivalence. Co-validation offers a proactive path for multi-site methods, while revalidation asserts a receiving lab's independent capability. The waiver, though efficient, is reserved for low-risk scenarios with strong justification.

The evolving landscape of method transfer emphasizes strategic, risk-based principles. By adopting frameworks that leverage optimal experimental design and advanced data modeling, scientists can achieve regulatory-compliant transfers with greater efficiency and resource conservation. A rigorous, well-documented transfer process, supported by the decision framework and toolkit provided, ultimately transforms a potential operational bottleneck into a strategic advantage, ensuring data integrity and product quality across the global pharmaceutical network.

In the highly regulated landscape of pharmaceutical research and development, ensuring the consistency and reliability of bioanalytical data across different laboratories is paramount. Analytical method transfer is the formal, documented process that qualifies a receiving laboratory to use a method that was developed and validated in another (transferring) laboratory [40]. Among the various approaches available, comparative testing has emerged as the most prevalent and trusted strategy [6] [11]. This guide provides an objective comparison of comparative testing against other method transfer strategies, underpinned by experimental data and framed within the context of modern bioanalytical chromatography research.

The Method Transfer Landscape: A Comparative Analysis

Method transfer is a critical bridge that connects laboratory-developed methods to the manufacturing environment, ensuring consistent product quality throughout its lifecycle [6]. Several standardized approaches exist, each with distinct applications and validation logics. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting the appropriate transfer method.

Strategic Approaches to Method Transfer

The choice of transfer strategy is guided by regulatory standards, the method's development stage, and the specific relationship between the involved laboratories [6] [40].

Table 1: Method Transfer Approaches: Principles and Applications

| Transfer Approach | Core Principle | Best-Suited Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing | Both laboratories analyze a predefined set of identical samples; results are statistically compared for equivalence [6] [40]. | Well-established, validated methods; laboratories with similar capabilities [40]. | Requires robust statistical analysis and homogeneous samples; most common approach [11]. |

| Covalidation | The receiving laboratory participates as an integral part of the method validation team, conducting experiments to generate reproducibility data [6]. | New methods being developed for multi-site use from the outset [40]. | Demands high collaboration and harmonized protocols; efficient for GMP testing at multiple labs [6]. |

| Revalidation | The receiving laboratory performs a full or partial revalidation of the method as if it were new to their site [40]. | Significant differences in lab conditions/equipment or when the original lab is unavailable [11]. | Most rigorous and resource-intensive; requires a complete validation protocol and report [40]. |

| Transfer Waiver | The formal transfer process is waived based on strong scientific justification and documented risk assessment [6]. | Highly experienced receiving lab using identical conditions; simple, robust methods (e.g., pharmacopoeia) [11]. | Rare and subject to high regulatory scrutiny; requires verification, not full transfer [40]. |

Comparative Testing: The Gold Standard Protocol

Experimental Design and Workflow

The integrity of comparative testing hinges on a meticulously controlled and documented experimental process. The workflow below details the key stages from initial planning to final method qualification.

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatography Assays

The success of a comparative study, particularly for complex bioanalytical assays like those for Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs), relies on high-quality, well-characterized reagents [33].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bioanalytical Method Transfer

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Application in Comparative Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Serves as the primary benchmark for calibrating instruments and quantifying analytes [33]. | A single, well-characterized lot must be used by both labs to ensure data comparability [40]. |

| Critical Reagents | Includes specific capture/detection antibodies, enzymes, and other binding molecules used in Ligand Binding Assays (LBAs) [33]. | Consistency in lot and sourcing between labs is vital to avoid variability in assay performance [6]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Prepared samples with known analyte concentrations used to monitor the assay's accuracy and precision during the transfer [6]. | Spiked samples are analyzed by both labs to statistically demonstrate equivalence [11]. |

| Stable-Labeled Internal Standards | Isotopically labeled versions of the analyte used in LC-MS/MS to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization [33]. | Essential for achieving the high precision required for successful comparative results in mass spectrometry. |