Closed-Loop Optimization of Organic Reactions: A Machine Learning-Driven Paradigm for Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative impact of closed-loop optimization, which integrates high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with machine learning (ML), on accelerating the development of organic syntheses.

Closed-Loop Optimization of Organic Reactions: A Machine Learning-Driven Paradigm for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of closed-loop optimization, which integrates high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with machine learning (ML), on accelerating the development of organic syntheses. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of self-optimizing platforms, details the methodological workflow from experimental design to algorithmic optimization, and addresses key challenges such as chemical representation and data efficiency. Through validation case studies from recent literature, including Suzuki-Miyaura coupling and metallophotocatalysis, it demonstrates how this approach outperforms traditional methods, significantly reducing experimentation time and material waste while achieving superior reaction outcomes for biomedical research.

The New Paradigm: Understanding Closed-Loop Systems and Their Core Components

Closed-loop optimization represents a paradigm shift in scientific experimentation, moving from traditional manual trial-and-error approaches to autonomous, data-driven research systems. This methodology integrates predictive machine learning with real-time experimental feedback under algorithmic control, creating an iterative cycle where each experiment informs the next. In disciplines ranging from battery development to organic synthesis, this approach dramatically accelerates the exploration of complex parameter spaces where exhaustive searching is practically impossible due to time or resource constraints [1] [2]. The core innovation lies in systems that automatically incorporate feedback from past experiments to inform future decisions, enabling intelligent navigation of multidimensional design spaces without requiring complete theoretical understanding of the underlying systems [3] [4].

Core Principles and Mechanism

At its foundation, closed-loop optimization combines three essential components: a parameterized experimental system, a measurable objective function, and a machine learning algorithm that selects subsequent experiments based on all accumulated data. The machine learning element, typically Bayesian optimization (BO), constructs a probabilistic model of the experimental landscape and uses it to balance exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of promising areas [1] [2]. This creates an autonomous cycle where the algorithm selects experimental parameters, receives performance measurements, updates its internal model, and recommends new experimental conditions—continuing until meeting convergence criteria or resource limits [3].

For organic chemistry and drug development applications, this framework enables navigating complex reaction condition spaces where catalyst composition, concentrations, temperatures, and other variables interact in unpredictable ways. The algorithm doesn't require fundamental physical principles to make progress; instead, it learns the relationship between input parameters and experimental outcomes directly from empirical data [2].

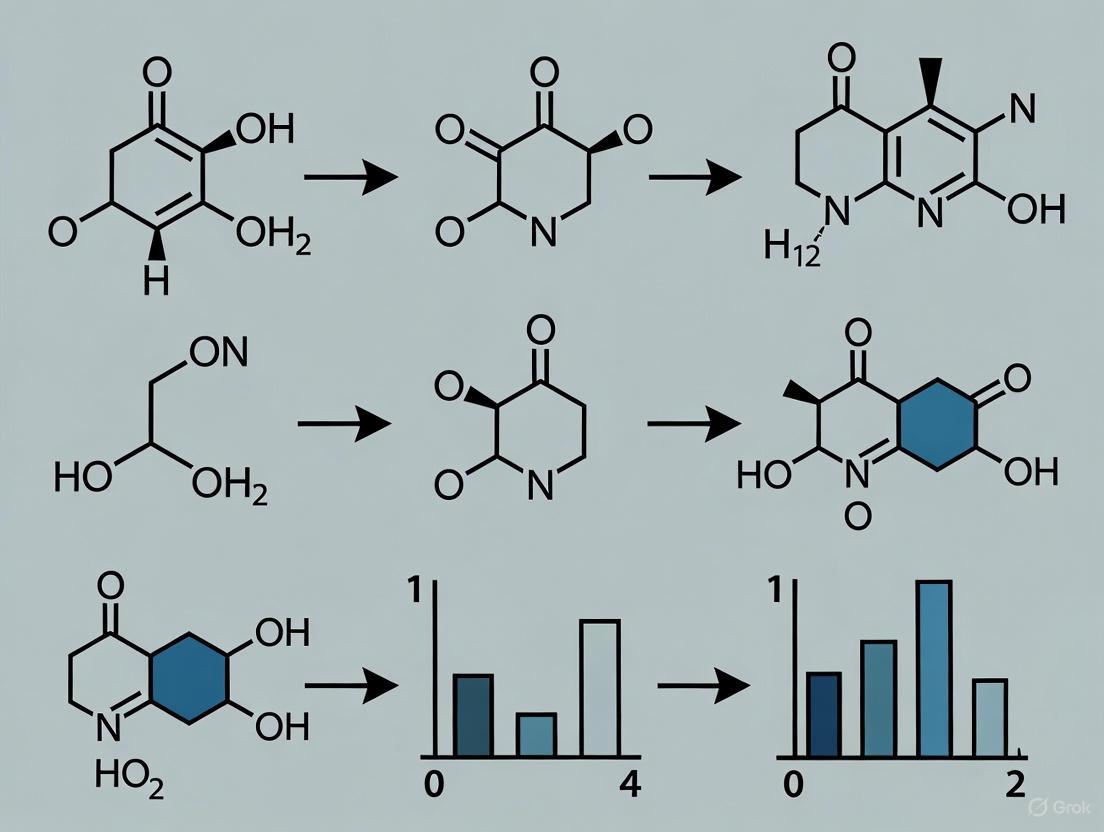

Application in Organic Molecular Metallophotocatalyst Discovery

A landmark demonstration of closed-loop optimization in organic chemistry involved discovering and optimizing organic photoredox catalysts (OPCs) for decarboxylative sp³–sp² cross-coupling reactions. This research addressed the significant challenge of predicting catalytic activities of OPCs from first principles, which depends on a complex range of interrelated properties that often leads to discovery through trial and error [2].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The research employed a sequential two-step closed-loop optimization process:

Stage 1: Catalyst Discovery from Virtual Library

- Constructed a virtual library of 560 synthesizable cyanopyridine (CNP) molecules using Hantszch pyridine synthesis with 20 β-keto nitrile derivatives and 28 aromatic aldehydes [2]

- Encoded each CNP using 16 molecular descriptors capturing thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state properties

- Implemented batched constrained discrete Bayesian optimization

- Initialized with 6 diverse CNPs selected via Kennard-Stone algorithm

- Iteratively synthesized and tested batches of 12 CNPs guided by the Bayesian optimization algorithm

- Evaluated catalysts under standardized conditions: 4 mol% CNP, 10 mol% NiCl₂·glyme, 15 mol% dtbbpy, 1.5 equiv. Cs₂CO₃, DMF, blue LED irradiation [2]

Stage 2: Reaction Condition Optimization

- Selected 18 promising CNPs from Stage 1

- Varied nickel catalyst concentration and coordinating ligands

- Employed second Bayesian optimization model to navigate 4,500 possible reaction condition combinations

- Evaluated 107 condition sets (2.4% of total space) through algorithmic guidance [2]

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Organic Photoredox Catalyst Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Example from Study |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanopyridine (CNP) Core | Serves as molecular scaffold for photocatalyst library | Functionalized with Ra (β-keto nitrile) and Rb (aromatic aldehyde) derivatives [2] |

| Nickel Catalyst | Cross-coupling catalyst working synergistically with photocatalyst | NiCl₂·glyme at 10 mol% initial concentration [2] |

| Ligands | Coordinate with nickel catalyst to modulate reactivity | 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (dtbbpy) at 15 mol% [2] |

| Base | Facilitates decarboxylation and maintains reaction environment | Cs₂CO₃ (1.5 equivalents) [2] |

| Solvent | Reaction medium | Dimethylformamide (DMF) [2] |

| Light Source | Photoexcitation of catalysts | Blue light-emitting diode (LED) [2] |

Performance Metrics and Outcomes

The closed-loop optimization approach demonstrated remarkable efficiency in navigating the complex chemical space. By synthesizing and testing only 55 molecules (9.8% of the 560 virtual library), the system identified catalysts achieving 67% yield for the target cross-coupling reaction. The subsequent reaction condition optimization evaluated just 107 of 4,500 possible condition combinations (2.4% of total space) to reach an 88% yield [2]. This represents an order-of-magnitude reduction in experimental effort compared to traditional high-throughput screening or design-of-experiments approaches.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Results from Sequential Optimization

| Optimization Stage | Library Size | Experiments Performed | Efficiency | Best Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Discovery | 560 virtual CNPs | 55 synthesized & tested | 9.8% exploration | 67% reaction yield |

| Condition Optimization | 4,500 possible conditions | 107 evaluated | 2.4% exploration | 88% reaction yield |

| Overall Efficiency | 5,060 total possibilities | 162 total experiments | 3.2% exploration | 88% final yield |

Comparative Analysis with Battery Fast-Charging Optimization

The effectiveness of closed-loop optimization extends beyond organic chemistry, as demonstrated by its application to battery fast-charging protocols. In this domain, researchers faced similar challenges with time-intensive experiments—evaluating battery cycle life typically required months to years per experiment [1] [4].

Experimental Protocol for Battery Optimization

The battery research employed a complementary approach combining two key elements:

- Early-prediction model: Reduced experiment time from months to days by predicting final cycle life using data from the first few cycles [1]

- Bayesian optimization algorithm: Reduced number of experiments by balancing exploration and exploitation to efficiently probe the parameter space of 224 charging protocols [1]

This methodology identified high-cycle-life charging protocols in just 16 days compared to the estimated 500 days required for exhaustive search without early prediction [1] [4]. The general workflow shares remarkable similarities with the organic catalyst optimization, despite the different application domains.

Implementation Framework

Implementing closed-loop optimization requires specific computational and experimental infrastructure. The Boulder Opal framework provides a representative example of the necessary components, which includes establishing an interface with the experiment, configuring the optimization parameters, and executing the iterative cycle [3].

Core Implementation Protocol

1. Experimental Interface Configuration

- Define optimizable parameters as real numbers representing controllable experimental quantities

- Establish cost function measurement quantifying experimental objective

- Configure experimental batching to accommodate hardware constraints and latency [3]

2. Optimization Setup

- Determine initial seed parameters through diverse sampling (e.g., uniform distribution)

- Select and initialize appropriate optimizer (e.g., CMA-ES, Bayesian optimization)

- Define parameter bounds based on experimental constraints [3]

3. Execution Cycle

- Algorithm generates test parameter sets

- Experimental apparatus executes tests and returns cost measurements

- Algorithm updates internal model and selects new test points

- Cycle continues until meeting convergence criteria (target cost, iteration limit) [3]

This framework emphasizes the flexibility of closed-loop approaches to adapt to various experimental domains without requiring complete system models, making it particularly valuable for complex organic reaction systems where first-principles understanding remains incomplete.

Closed-loop optimization represents a transformative methodology for scientific experimentation, particularly in complex domains like organic reaction research and drug development. By integrating machine learning with automated experimentation, this approach enables efficient navigation of vast parameter spaces that would be prohibitive to explore through traditional methods. The documented successes in organic photocatalyst discovery and battery protocol optimization demonstrate order-of-magnitude improvements in experimental efficiency while achieving superior performance outcomes. As this methodology becomes more accessible through frameworks like Boulder Opal and others, its adoption across chemical and pharmaceutical research promises to accelerate discovery timelines and expand the accessible design space for novel molecular entities and synthetic methodologies.

The exploration and optimization of organic reactions have traditionally relied on iterative, one-variable-at-a-time approaches that are both time-consuming and resource-intensive. The emergence of closed-loop optimization systems represents a paradigm shift, integrating Design of Experiments (DOE), High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), automated data collection, and machine learning (ML) prediction into a self-improving cycle. This methodology is particularly transformative in bioca talysis, where it accelerates the discovery and engineering of enzymatic reactions for pharmaceutical applications. By leveraging this integrated framework, researchers can efficiently navigate vast chemical and biological spaces that were previously inaccessible through conventional methods. The core strength of this approach lies in its ability to rapidly generate high-quality datasets and use ML models to extract meaningful patterns, enabling predictive design and optimization of biocatalytic processes with unprecedented efficiency [5] [6].

This automated, data-driven workflow is revolutionizing how scientists approach complex biochemical optimization challenges. As noted in research from Peking University, this combination "explores a black-box space with no prior knowledge to find molecules with target properties" [6]. The system's ability to learn from each experimental cycle and refine its predictions creates a continuous improvement loop that dramatically accelerates research timelines. For drug development professionals, this translates to faster identification of viable enzyme candidates, optimized reaction conditions, and ultimately more efficient routes to therapeutic compounds.

Core Components of the Workflow

Design of Experiments (DOE)

Design of Experiments provides the foundational structure for systematic investigation of multivariable reaction spaces. In biocatalytic reaction optimization, DOE principles guide the strategic selection of input variables—such as enzyme variants, substrate concentrations, pH buffers, temperature levels, and cofactors—to maximize information gain while minimizing experimental effort. Rather than testing one factor at a time, statistical experimental designs enable researchers to explore interaction effects between multiple parameters simultaneously.

In practice, researchers initially define the reaction objective—such as maximizing yield, enantioselectivity, or total turnover number—and identify critical factors likely to influence these outcomes. For enzyme engineering applications, this typically involves creating a diverse yet rationally designed library of enzyme variants based on sequence-activity relationships or structural insights. The design space may also include reaction condition parameters such as solvent composition, temperature, pH, and pressure. These elements are structured in experimental arrays (e.g., factorial designs, Plackett-Burman designs, or central composite designs) that efficiently sample the multi-dimensional parameter space while maintaining statistical power for detecting significant effects [6].

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

High-Throughput Experimentation provides the physical implementation platform for executing designed experiments in miniaturized, parallelized formats. Modern HTE systems for biocatalytic applications leverage liquid handling robots, microtiter plates, and automated screening protocols to conduct thousands of reactions with minimal manual intervention. This scalability is essential for comprehensively exploring the complex variable spaces inherent to enzyme-catalyzed reactions.

A prominent example comes from the development of the CATNIP prediction tool, where researchers conducted a "high-throughput experimental screening campaign" involving "thousands of micro-reactions in 96-well plates" where "314 enzymes were paired with 111 substrates in a pairwise manner" [5]. This massive parallelization enabled the generation of a comprehensive dataset (BioCatSet1) containing 215 newly discovered biocatalytic reactions. Similarly, the Peking University team working on synthetic polyclonal antibodies employed "automated liquid workstations" to precisely formulate "hundreds of differenté…æ–¹ of random heteropolypeptides (RHPs) in 96-well plates" [6]. These examples demonstrate how HTE enables the rapid empirical testing of theoretical designs, generating the robust datasets necessary for subsequent machine learning analysis.

Table 1: Key HTE Platform Components for Biocatalytic Reaction Optimization

| Component | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automated pipetting systems for precise reagent delivery | Dispensing enzyme variants and substrate solutions into microtiter plates [6] |

| Multi-well Plates | Miniaturized reaction vessels (96-, 384-, 1536-well) | Performing thousands of micro-reactions in 96-well plates for enzyme-substrate pairing [5] |

| Automated Screening Assays | High-throughput analytical methods (UV-Vis, fluorescence) | ELISA screening for polymer-protein binding affinity [6] |

| Library Management Systems | Software and hardware for tracking diverse sample libraries | Managing libraries of 314 enzyme sequences and 111 substrates [5] |

Data Collection and Management

The data collection phase transforms experimental results into structured, machine-readable formats suitable for computational analysis. For biocatalytic reactions, this typically involves quantifying conversion rates, reaction yields, enantiomeric excess, enzyme kinetics (kcat, Km), and thermodynamic parameters. Modern platforms automate this process through integrated analytical systems such as HPLC-MS, GC-MS, NMR spectroscopy, and plate reader spectrophotometers that directly feed data into centralized databases.

Critical to this stage is the development of standardized data descriptors that effectively capture molecular properties and reaction outcomes. In the CATNIP project, researchers used the MORFEUS computational chemistry software to calculate "a set of 21-parameter 'digital fingerprints' for each molecular substrate" [5]. Similarly, enzyme sequences were quantified based on their "relationship distances in the Sequence Similarity Network (SSN)" [5]. This structured data representation enables machines to recognize complex patterns between enzyme sequences, substrate structures, and reaction outcomes. Proper data management ensures that information flows seamlessly from experimental execution to model training, creating the foundation for accurate predictive algorithms.

Machine Learning-Guided Prediction

Machine learning models serve as the cognitive core of the closed-loop system, extracting meaningful relationships from experimental data to guide subsequent design cycles. Various ML algorithms can be applied depending on dataset size and problem complexity. For biocatalytic reaction prediction, common approaches include gradient boosting decision trees (GBM), random forests, neural networks, and Gaussian process regression.

The CATNIP platform exemplifies this approach, employing "a machine learning model called Gradient Boosted Decision Tree (GBM)" which the researchers describe as "a committee of decision experts" that "learns the extremely complex, non-linear intrinsic connections between chemical space and protein sequence space" [5]. This model demonstrated remarkable predictive accuracy, with its top-10 enzyme predictions being "7 times more likely to find a truly effective enzyme than randomly selecting 10 enzymes from the enzyme library" [5]. Similarly, the Peking University team used "Bayesian optimization and genetic algorithms" where "Bayesian optimization uses Gaussian process regression to estimate the performance distribution of untested formulations" [6]. These trained models can then propose the most promising candidates for the next experimental cycle, progressively focusing the search on optimal regions of the chemical and biological space.

Figure 1: Closed-Loop Optimization Workflow for Biocatalytic Reactions. The system cycles through designed experiments, high-throughput testing, data collection, and machine learning prediction, with each iteration informing the next experimental design.

Application Protocols

Protocol: Enzyme-Substrate Reaction Discovery Using Closed-Loop Optimization

This protocol describes the comprehensive procedure for implementing a closed-loop optimization system to discover novel enzyme-catalyzed reactions, based on the methodology used in developing the CATNIP prediction tool [5].

Initial Experimental Setup and Library Design

Materials:

- Enzyme library (e.g., aKGLib1 containing 314 NHI enzymes) [5]

- Substrate library (e.g., 111 diverse compounds) [5]

- 96-well or 384-well reaction plates

- Automated liquid handling system

- Appropriate buffers and cofactors for target reaction class

- Analytical instrumentation (HPLC-MS, GC-MS, or plate readers)

Procedure:

- Library Design and Curation: Compile a diverse enzyme library representing the target protein family. For the CATNIP study, researchers used sequence similarity networks (SSN) to select 314 enzyme sequences with "average identity of only 13.7%" to maximize diversity [5].

- Reaction Plate Preparation: Using automated liquid handlers, dispense enzyme solutions into designated wells of microtiter plates. In parallel, prepare substrate solutions in appropriate solvents.

- High-Throughput Screening: Initiate reactions by combining enzyme and substrate solutions across all pairwise combinations. Incubate under controlled temperature and agitation.

- Reaction Quenching and Analysis: After appropriate incubation time, quench reactions and analyze conversion rates or product formation using suitable analytical methods.

Data Processing and Model Training

Procedure:

- Feature Engineering: Calculate molecular descriptors for all substrates (e.g., using MORFEUS software for 21-parameter digital fingerprints) [5]. Encode enzyme sequences using bioinformatic descriptors such as SSN coordinates.

- Dataset Assembly: Compile experimental results into a structured table linking enzyme descriptors, substrate descriptors, and reaction outcomes (e.g., conversion rate, enantioselectivity).

- Model Training: Implement and train machine learning algorithms (e.g., Gradient Boosted Decision Trees) using the assembled dataset. Employ cross-validation to assess model performance and prevent overfitting.

Prediction and Experimental Validation

Procedure:

- Model Predictions: Use trained models to predict promising enzyme-substrate pairs for subsequent validation. Generate ranked lists of candidates for both "substrate-to-enzyme" and "enzyme-to-substrate" predictions [5].

- Experimental Validation: Test top predictions from the model in laboratory experiments. For the CATNIP platform, researchers validated predictions by testing "10 candidate enzymes" for new substrates, with "7 of them successfully catalyzing the reaction" [5].

- Data Feedback and Model Retraining: Incorporate validation results into the training dataset and retrain models to improve predictive accuracy in subsequent cycles.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from Closed-Loop Biocatalytic Screening

| Metric | Initial Screening | ML-Guided Validation | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate Discovery | 38% of enzymes showed activity [5] | 70% of predicted enzymes showed activity [5] | ~1.8x increase |

| Reaction Discovery Scale | 215 new reactions identified [5] | N/A | Comprehensive mapping |

| Prediction Accuracy | N/A | 91.7% for haloenzymes [5] | >7x better than random [5] |

| Screening Efficiency | 314 enzymes × 111 substrates [5] | Focused testing of top predictions | Reduced experimental load |

Protocol: Data-Driven Design of Synthetic Polyclonal Antibodies

This protocol outlines the closed-loop methodology for designing functional synthetic polymers that mimic natural protein functions, based on the work published by Peking University researchers [6].

High-Throughput Polymer Synthesis and Screening

Materials:

- Polymer precursors (e.g., amino acid derivatives for polypeptide synthesis)

- Modification reagents (8 different modifying groups with diverse properties) [6]

- 96-well plates with automated synthesis capability

- Target proteins (e.g., TNF-α, IFN-α)

- ELISA reagents and equipment

- Automated liquid handling systems

Procedure:

- Automated Polymer Synthesis: In 96-well plates, use automated workstations to synthesize "hundreds of differenté…æ–¹ of random heteropolypeptides (RHPs)" by systematically varying the composition of 8 different modification groups [6].

- Binding Affinity Screening: Evaluate each RHP formulation for binding to target proteins using ELISA. Include control proteins (e.g., human serum albumin) to assess specificity.

- Quantitative Scoring: Calculate binding scores based on "difference in binding strength" between target and control proteins [6].

Machine Learning Optimization

Procedure:

- Algorithm Implementation: Employ both Bayesian optimization (BO) and genetic algorithms (GA) to guide the exploration of the polymer composition space.

- Iterative Design Cycles: Conduct multiple rounds (typically 4-6) of synthesis and testing, with each round informed by the algorithmic predictions of most promising compositions.

- Performance Validation: Scale up synthesis of top-performing candidates for detailed characterization. For the TNF-α targeting polymer, this resulted in a binding constant of "7.9 nM" with "approximately 400-fold higher affinity than human serum albumin" [6].

Figure 2: Workflow for Data-Driven Design of Synthetic Polyclonal Antibodies. The system combines automated synthesis, high-throughput screening, and machine learning optimization to identify functional polymers that mimic natural protein functions.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of closed-loop optimization for organic reactions requires access to specialized reagents, libraries, and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key materials referenced in the protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Closed-Loop Biocatalytic Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Specifications | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Libraries | Diversity-optimized (e.g., aKGLib1: 314 enzymes, 13.7% avg identity) [5] | Provides biological catalyst diversity for reaction discovery and optimization |

| Substrate Libraries | Structurally diverse compound collections (e.g., 111 substrates) [5] | Enables comprehensive exploration of reaction scope and specificity |

| Polymer Precursors | Amino acid derivatives with modification handles [6] | Building blocks for synthetic polymer libraries mimicking protein functions |

| Modification Reagents | 8+ chemotypes (hydrophilic, hydrophobic, charged) [6] | Introduces functional diversity into polymer libraries for property optimization |

| Analytical Standards | Quantified substrates and products for HPLC/GC calibration | Enables accurate quantification of reaction conversion and yield |

| Multi-well Plates | 96-well, 384-well, or 1536-well formats [5] [6] | Miniaturized reaction vessels for high-throughput parallel experimentation |

| Binding Assay Kits | ELISA or similar protein-binding detection systems [6] | High-throughput screening of molecular interactions and specificities |

| Sequence-Structure Descriptors | Digital fingerprints (e.g., 21-parameter molecular descriptors) [5] | Machine-readable representations of molecules for ML model training |

The integration of Design of Experiments, High-Throughput Experimentation, systematic Data Collection, and ML-Guided Prediction represents a transformative framework for optimizing organic and biocatalytic reactions. This closed-loop approach enables researchers to efficiently navigate complex multivariable spaces that would be intractable through traditional methods. As demonstrated by the CATNIP platform for enzyme reaction prediction and the synthetic antibody design work from Peking University, this methodology dramatically accelerates the discovery and optimization process while providing fundamental insights into structure-activity relationships.

For drug development professionals, adopting this integrated workflow offers the potential to significantly reduce development timelines and costs while accessing novel chemical space. The continuous learning inherent in this approach creates a virtuous cycle of improvement, with each iteration enhancing predictive capabilities and experimental efficiency. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they are poised to become the standard methodology for reaction optimization across pharmaceutical development and manufacturing.

The discovery of optimal conditions for organic reactions is a labor-intensive, time-consuming task that requires exploring a high-dimensional parametric space. Traditional optimization, guided by human intuition and one-variable-at-a-time approaches, is increasingly being supplanted by a new paradigm enabled by lab automation and machine learning (ML). Closed-loop optimization represents the cutting edge of this paradigm, wherein multiple reaction variables are synchronously optimized with minimal human intervention [7]. This approach integrates three core technological pillars: automated batch reactor modules, robotic material handling systems, and custom automation platforms. When coupled with ML algorithms, these systems form "self-driving laboratories" that can rapidly navigate complex experimental spaces to identify high-performing conditions for organic reactions, significantly accelerating research in drug development and materials science [7] [8].

HTE Platform Architectures and Specifications

High-Throughput Experimentation platforms are defined by their ability to perform rapid screening and analysis of large numbers of experimental conditions simultaneously. They combine automation, parallelization, advanced analytics, and data processing to streamline repetitive tasks and increase experimental execution rates compared to traditional manual experimentation [7].

Commercial Batch Reactor Platforms

Batch reactors operate without the continuous flow of reagents or products until a target conversion is achieved. HTE batch platforms leverage parallelization to perform numerous reactions under different conditions simultaneously.

Table 1: Commercial HTE Batch Platforms and Their Applications

| Platform/Manufacturer | Reactor Format | Key Features | Documented Organic Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemspeed SWING [7] | 96-well metal blocks (PFA-sealed) | Integrated robotic system with four-needle dispense head for low-volume and slurry delivery; precise control of categorical/continuous variables | Stereoselective Suzuki–Miyaura couplings [7], Buchwald–Hartwig aminations [7] |

| Modular Robotic System (e.g., Zinsser Analytic, Mettler Toledo) [7] | 96/48/24-well plates or 1536-well plates (UltraHTE) | Liquid handling via plunger pump (syringe, pipette); reactor capable of heating and mixing; in-line/online analytics | Suzuki couplings, N-alkylations, hydroxylations, photochemical reactions [7] |

Inherent Limitations of Batch MTPs: A significant challenge with standard microtiter plate (MTP) reactors is the inability to independently control variables like reaction time, temperature, and pressure in individual wells. Furthermore, standard MTPs are unsuitable for high-temperature reactions near a solvent's boiling point as they are not designed for reflux conditions [7].

Robotic Arm-Based Automation Systems

Robotic arms introduce mobility and flexibility, connecting discrete experimental stations to create a unified, automated workflow.

Table 2: Custom Robotic Automation Systems

| System Name / Developer | Robotic Function | Integrated Stations & Capabilities | Performance & Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot [7] (Burger et al.) | Mobile robot as a human substitute | Eight stations: solid/liquid dispensing, sonication, characterization equipment, consumables/sample storage | Ten-dimensional parameter search for photocatalytic hydrogen production; achieved hydrogen evolution rate of ~21.05 µmol·hâ»Â¹ after 8 days [7] |

| Aurora [9] (Empa Lab) | Robotic battery materials research platform | Automated electrolyte formulation, battery cell assembly, and >1500 battery cycling channels; FAIR data management | Produces large, standardized, open datasets for battery research [9] |

Custom and Low-Cost Automation Solutions

To address the high cost and large footprint of commercial systems, several research groups have developed innovative custom platforms.

- RoboChem-Flex [8]: This is a low-cost, modular self-driving laboratory platform designed to democratize autonomous chemical experimentation. It combines customizable, in-house-built hardware with a flexible Python-based software framework that integrates real-time device control and advanced Bayesian optimization strategies, including multi-objective and transfer learning workflows. The system supports both fully autonomous closed-loop operation and human-in-the-loop configurations [8].

- Portable Chemical Synthesis Platform [7] (Manzano et al.): This small-footprint system utilizes 3D-printed reactors generated on demand. It features liquid handling, stirring, heating, and cooling modules, and is capable of operating under inert and low-pressure atmospheres, handling separation steps, and pressure sensing. It has successfully synthesized small organic molecules, oligopeptides, and oligonucleotides, offering a low-cost alternative despite lower throughput and a lack of integrated characterization modules in its current configuration [7].

Experimental Protocols for Closed-Loop Optimization

The following protocols detail the operation of HTE platforms within a closed-loop optimization framework, illustrated by specific case studies from recent literature.

Protocol 1: Bayesian Optimization of Organic Photoredox Catalysts

This protocol is adapted from the two-step, data-driven approach for discovering and optimizing organic molecular metallophotocatalysts, as detailed in Nature Chemistry [2].

Objective: To identify a high-performance organic photoredox catalyst (OPC) formulation from a virtual library of 560 candidate molecules for a decarboxylative sp³–sp² cross-coupling reaction.

Workflow Overview: The process involves two sequential closed-loop Bayesian optimization (BO) workflows. The first loop selects and synthesizes promising catalyst candidates, while the second loop optimizes the reaction conditions for the best-performing catalysts.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Virtual Library Design & Encoding:

- Reagent Solution: Design a virtual library of 560 cyanopyridine (CNP) core molecules using 20 β-keto nitrile derivatives (Ra groups: 7 ED, 5 EW, 8 X) and 28 aromatic aldehydes (Rb groups: 18 PAHs, 5 PAs, 5 CZs) via Hantzsch pyridine synthesis [2].

- Data Processing: Encode each CNP molecule using 16 molecular descriptors capturing key thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state properties [2].

Initial Sampling & Experimentation:

- Reagent Solution: Select an initial set of 6 CNP molecules scattered across the chemical space using the Kennard-Stone (KS) algorithm. Synthesize these molecules.

- Experimental Execution: Test each synthesized CNP under standardized reaction conditions: 4 mol% CNP, 10 mol% NiCl₂·glyme, 15 mol% dtbbpy, 1.5 equiv. Cs₂CO₃, DMF solvent, blue LED irradiation. Perform catalysis measurements in triplicate and report the average reaction yield [2].

Machine Learning & Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Data Processing: Build a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model using the collected experimental data (catalyst descriptors as input, reaction yield as output) [2].

- Algorithmic Selection: Using Bayesian optimization, query the model to select the next batch of 12 CNP molecules from the virtual library that are predicted to maximize the reaction yield.

- Iteration: Synthesize and test the newly selected catalysts. Add the results to the dataset and update the GP model. Repeat this loop until convergence (e.g., yield no longer improves significantly). The published study achieved a yield of 67% after synthesizing only 55 of the 560 candidates (~9.8%) [2].

Reaction Condition Optimization:

- Experimental Execution: Take the best-performing catalysts (e.g., 18 from the published study) and initiate a second BO campaign. This campaign should simultaneously optimize continuous and categorical variables, such as catalyst concentration, nickel catalyst loading, and ligand concentration.

- Outcome: The published study evaluated 107 of 4,500 possible condition sets (~2.4%) and identified conditions yielding up to 88% [2].

Protocol 2: General Workflow for Closed-Loop HTE in Organic Synthesis

This protocol generalizes the core steps of a closed-loop optimization campaign as reviewed in the Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry [7].

Objective: To autonomously optimize an organic synthesis reaction (e.g., yield, selectivity) by synchronously varying multiple reaction parameters.

Workflow Overview: The platform operates in a continuous cycle of design, execution, analysis, and planning, driven by an optimization algorithm.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Design of Experiments (DOE): The optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian optimizer) selects an initial or subsequent set of reaction conditions to test. This defines the parameters for a single iteration (or "batch") of experiments [7].

Reaction Execution: A high-throughput platform (e.g., Chemspeed, custom robotic system) automatically prepares the reactions. This involves liquid handling for reagent transfer, dispensing into reaction vessels (well plates or vials), and controlling environmental conditions like temperature and stirring [7].

Data Collection & Analysis: The platform utilizes integrated analytical tools (e.g., in-line HPLC, UPLC, GC) to monitor reaction progress or analyze the final composition. Data is automatically processed to calculate performance metrics (e.g., yield, conversion) against the target objectives [7].

Machine Learning-Driven Prediction: The collected data is fed back to the optimization algorithm. The algorithm updates its internal model of the reaction landscape and predicts the most informative set of conditions to test in the next cycle to rapidly approach the optimum [7]. The loop (Steps 1-4) continues until a predefined performance target or iteration limit is reached.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section catalogs key reagents, materials, and software solutions referenced in the HTE protocols and case studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTE

| Item Name / Category | Specification / Example | Function in Protocol / Application |

|---|---|---|

| CNP Catalyst Library [2] | 560 virtual molecules from 20 Ra (β-keto nitriles) and 28 Rb (aldehydes) groups | Organic photoredox catalyst candidates for metallaphotocatalysis. |

| Nickel Catalyst [2] | NiCl₂·glyme | Transition-metal catalyst in dual photoredox/Nickel cross-coupling cycles. |

| Ligand [2] | dtbbpy (4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine) | Ligand for nickel catalyst coordination. |

| Base [2] | Cs₂CO₃ | Base for decarboxylative cross-coupling reaction. |

| Solvent [2] | DMF (Dimethylformamide) | Reaction solvent. |

| Commercial HTE Platform [7] | Chemspeed SWING, Zinsser Analytic, Mettler Toledo | Automated liquid handling, reaction setup, and parallel synthesis. |

| Custom Robotic Platform [7] [8] | RoboChem-Flex, Mobile Robot by Burger et al. | Flexible, customizable automation for complex, multi-step experimental workflows. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software [2] [8] | Gaussian Process-based models, Python frameworks | Core algorithm for guiding closed-loop experimentation and predicting optimal conditions. |

| Bet-bay 002 | Bet-bay 002, MF:C22H18ClN5O, MW:403.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ibrutinib-biotin | Ibrutinib-biotin, MF:C56H80N12O9S, MW:1097.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Theoretical Foundations: Bayesian Optimization and Gaussian Processes

Bayesian optimization (BO) is a powerful machine learning strategy for the global optimization of black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate. This makes it particularly suited for optimizing chemical reactions, where each experiment is costly and time-consuming. The core principle of BO lies in its iterative process of building a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function (e.g., reaction yield or selectivity) and using an acquisition function to intelligently select the next experiments to run. This enables efficient navigation of complex, high-dimensional chemical spaces while balancing the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of known promising areas [10].

Gaussian Processes (GPs) are the most commonly employed surrogate model within Bayesian optimization frameworks. A GP defines a distribution over functions and is fully specified by a mean function and a covariance function (kernel). The kernel function is critical as it encodes assumptions about the function's smoothness and periodicity. For example, the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel models smooth responses of continuous variables like temperature, while a Periodic Kernel can capture resonance effects in photocatalysis [11]. This probabilistic framework provides not only predictions of reaction outcomes but also quantifies the uncertainty (standard deviation) associated with those predictions, which is essential for guiding experimental campaigns [10] [11].

Applications in Organic Synthesis: A Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes key recent applications of Bayesian optimization and Gaussian processes across various challenging domains in organic synthesis, highlighting the specific algorithms used and the outcomes achieved.

| Application Domain | Key Optimization Variables | BO/GP Methodology | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Photoredox Catalyst (OPC) Discovery | Molecular structure of cyanopyridine-based OPCs, nickel catalyst/ligand concentration [2] | Batched, constrained BO with GP surrogate and molecular descriptors [2] | Identified competitive organic catalysts; achieved 88% yield after testing only 107 of 4,500 possible conditions [2] | |

| Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Reaction Optimization | Reagents, solvents, catalysts, additives, temperature [12] | Minerva platform; GP regressor with scalable AFs (q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) [12] | Achieved 76% yield and 92% selectivity in a space of 88,000 conditions, outperforming traditional HTE [12] | |

| Pharmaceutical Process Development | Conditions for Suzuki coupling & Buchwald-Hartwig amination [12] | High-throughput BO (batch sizes of 24-96) with GP [12] | Identified multiple conditions with >95% yield/selectivity; reduced development time from 6 months to 4 weeks [12] | |

| Stereoselective Glycosylation Discovery | Additives, solvents, promoters, temperature [13] | BO treating reaction class as a black box [13] | Discovered novel lithium salt-directed stereoselective glycosylation methodology [13] | |

| Nanoparticle Synthesis & Drug Synthesis | Elemental composition in 8D alloy space; reagent equivalents, solvent, temperature [11] | GP surrogate with domain-informed kernels (Matérn, Neural Network) [11] | High prediction success (18/19) for nanoparticles; 99% yield for Mitsunobu reaction via non-traditional conditions [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Closed-Loop Optimization

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective Optimization of a Metallophotoredox Reaction

This protocol is adapted from a study that used a two-step, closed-loop BO workflow to discover organic photoredox catalysts and optimize their reaction conditions for a decarboxylative cross-coupling [2].

Step 1: Define the Virtual Chemical Library and Search Space

- Construct a virtual library of candidate molecules. The cited example used a cyanopyridine (CNP) core, combining 20 β-keto nitriles (Ra) and 28 aromatic aldehydes (Rb) for a 560-member library [2].

- For reaction condition optimization, define the ranges and options for continuous and categorical variables (e.g., photocatalyst identity, transition metal catalyst loading, ligand concentration, base equivalence) [2].

Step 2: Encode the Chemical Space

- Calculate molecular descriptors for each catalyst candidate. The protocol in [2] used 16 thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state property descriptors (e.g., redox potentials, absorption wavelengths).

- Standardize all numerical descriptors and one-hot encode categorical variables.

Step 3: Initial Experimental Design

- Select an initial set of experiments to seed the model. The Kennard-Stone (KS) algorithm can be used to choose a small set (e.g., 6 points) that are diverse and span the defined space [2].

- Synthesize and test the selected catalysts or conditions under standardized reactions. Perform replicates to estimate experimental noise.

Step 4: Establish the Closed-Loop Workflow

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model on all accumulated experimental data. The GP uses a kernel (e.g., Matérn) to model the relationship between inputs (descriptors/conditions) and outputs (e.g., yield) [2].

- Candidate Selection: Use an acquisition function to propose the next batch of experiments. For batched multi-objective optimization, functions like q-NParEgo or Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective (TSEMO) are effective [2] [12].

- Automated Experimentation: Integrate the BO platform with automated robotic fluid handling systems to execute the proposed experiments.

- Analysis & Feedback: Use high-throughput analytics (e.g., UPLC/HPLC) to quantify reaction outcomes. Feed the results back into the dataset.

- Iterate: Repeat the model training and candidate selection steps until a performance target is met or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Reaction Optimization with Minerva

This protocol is designed for highly parallel optimization using a platform like Minerva, which is benchmarked for batch sizes of 24, 48, or 96 experiments per iteration [12].

Step 1: Define the Discrete Condition Space

- Enumerate all plausible combinations of reaction parameters (e.g., ligands, solvents, bases, catalysts, temperatures) based on chemical intuition and practical constraints.

- Apply filters to automatically remove unsafe or impractical conditions (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [12].

Step 2: Initial Quasi-Random Sampling

- Use a Sobol sequence to select the initial batch of experiments. This ensures maximum coverage and diversity across the entire condition space [12].

Step 3: Build the GP Model and Select Subsequent Batches

- Train a GP regressor on the collected data. For high-dimensional and categorical data, the GP kernel must be carefully chosen to handle mixed data types.

- Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function like q-NParEgo, Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI), or q-NEHVI to select the next large batch of experiments in parallel. These are designed to handle large batch sizes computationally efficiently [12].

- The acquisition function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performing regions.

Step 4: Iterative High-Throughput Experimentation

- Conduct the batch of experiments using an automated HTE platform (e.g., a 96-well plate reactor).

- Analyze outcomes and update the dataset.

- Repeat the modeling and batch selection process for a predetermined number of iterations or until performance plateaus.

Workflow Visualization: Closed-Loop Bayesian Optimization

The diagram below illustrates the iterative, closed-loop workflow of a Bayesian optimization campaign for chemical reactions.

The following table lists essential materials, computational tools, and their functions for implementing Bayesian optimization in organic chemistry.

| Category | Item / Software / Algorithm | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Research Reagents & Materials | Organic Photoredox Catalyst Library (e.g., Cyanopyridine cores) [2] | Tunable, metal-free catalysts for metallaphotoredox reactions. |

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Nickel complexes) [12] | Earth-abundant, lower-cost alternatives to palladium for cross-couplings. | |

| Ligand Libraries (e.g., dtbbpy, diverse phosphine ligands) [2] [12] | Modulate catalyst activity and selectivity; key categorical variables. | |

| Computational & Software Tools | Molecular Descriptors (e.g., redox potentials, excitation energies) [2] | Encode molecular structures into numerical features for the ML model. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | Core surrogate model for predicting reaction outcomes and uncertainties [10] [12]. | |

| Acquisition Functions (AFs) | Guide experimental selection by balancing exploration and exploitation. Common AFs include Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), and multi-objective functions like q-NParEgo and TS-HVI [10] [12]. | |

| Automation & HTE Platforms (e.g., Minerva, RoboChem-Flex) [12] [8] | Enable highly parallel execution of reactions in closed-loop systems. | |

| Specialized Algorithms | Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective (TSEMO) | An AF that uses Thompson sampling for multi-objective optimization [10]. |

| Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) | Integrates deep neural networks (e.g., LLMs) with GPs to learn better representations for optimization [14]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing a Closed-Loop Workflow for Reaction Optimization

In the context of closed-loop optimization for organic reactions, the rapid and accurate prediction of molecular properties is paramount. This process relies on converting chemical structures into computer-interpretable numerical representations, known as molecular descriptors. The choice of descriptor significantly influences the performance of predictive models in tasks such as quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and virtual screening [15]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of contemporary molecular descriptor methodologies, from classical one-hot encoding to advanced density functional theory (DFT) calculations, and details their experimental protocols for integration into automated reaction optimization pipelines.

Molecular Descriptor Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of various molecular descriptor classes used in modern cheminformatics.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Molecular Descriptor Methodologies

| Descriptor Class | Key Features | Representation | Interpretability | Computational Cost | Primary Applications in Closed-Loop Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based (NMT) | Translates between SMILES/InChI; learned from large corpora [15] | Fixed-size continuous vector | Moderate | Moderate (requires training) | QSAR, virtual screening, de novo molecular design |

| Graph-Based (KA-GNN) | Integrates KAN modules into GNN node embedding, message passing, and readout [16] | Graph-structured data | High (highlights chemically meaningful substructures) | Moderate to High | Molecular property prediction, drug discovery |

| Fragment-Based (Saagar) | Extensible library of molecular substructures beyond drug-like compounds [17] | Pre-defined substructure patterns | High (clear structural insight) | Low | Environmental toxicology, chemical modeling |

| Quantum Chemical (DFT) | Derived from electronic structure calculations (e.g., ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) [18] [19] | Electronic/geometric parameters | High (direct physical meaning) | Very High | High-accuracy energy and property prediction, dataset generation |

| Fragment-Based Contrastive (MolFCL) | Embeds fragment-fragment interactions and uses functional group prompts [20] | Augmented molecular graph | High (identifies key functional groups) | Moderate | Molecular property prediction, interpretable drug design |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Data-Driven Descriptors via Neural Machine Translation

This protocol generates continuous molecular descriptors by training a model to translate between different molecular string representations, compressing the essential structural information into a latent vector [15].

- Input: Large corpus of molecular structures (e.g., 250,000+ unlabeled molecules from ZINC15 [20]).

- Software Requirements: Python, deep learning framework (e.g., PyTorch/TensorFlow), RDKit [15].

- Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Obtain canonical SMILES and InChI strings for all molecules using RDKit.

- Tokenization: Tokenize sequences into a vocabulary of characters (approx. 28-38 unique tokens), including special tokens for "Cl", "Br", etc. Convert tokens to one-hot vectors.

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Use an encoder-decoder model. The encoder (CNN or RNN) processes the input sequence (e.g., InChI). A fully connected layer maps the encoder's output to a fixed-size latent vector. The decoder (RNN) initializes its state from this vector and generates the output sequence (e.g., SMILES).

- Training Objective: Minimize the cross-entropy loss between the decoder's output and the target sequence on a character level.

- Descriptor Extraction: After training, pass any new molecule through the encoder network and extract the latent representation vector as its molecular descriptor.

Protocol 2: Implementing Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks (KA-GNNs)

This protocol details the integration of Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) into Graph Neural Networks for molecular property prediction, enhancing expressivity and interpretability [16].

- Input: Molecular graphs where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds.

- Software Requirements: Python, deep learning framework, graph neural network library.

- Procedure:

- Node Embedding Initialization: For each atom node, concatenate its atomic features (e.g., atomic number, radius) with the averaged features of its neighboring bonds. Pass this concatenated vector through a Fourier-based KAN layer to generate the initial node embedding.

- Message Passing with KANs: In each message-passing layer, aggregate features from neighboring nodes. Instead of using standard MLPs with fixed activation functions, update node features using residual KAN layers. The KANs employ learnable univariate functions (e.g., Fourier series) on edges, enabling the model to capture complex, non-linear relationships [16].

- Readout with KANs: After several message-passing layers, generate a graph-level representation by pooling all node features. Pass this representation through a final KAN-based readout layer for the downstream prediction task (e.g., property classification).

Protocol 3: High-Fidelity Descriptor Calculation using Density Functional Theory

This protocol calculates quantum chemical molecular descriptors, which provide a first-principles description of electronic structure and are valuable for high-accuracy benchmarks [18] [21] [19].

- Input: 3D molecular geometry.

- Software Requirements: Quantum chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, Schrödinger Materials Science Suite).

- Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometry using a DFT method (e.g., B3LYP functional) and a basis set (e.g., 6-311++G(d,p)) until a stable minimum energy is reached [21].

- Property Calculation: Using the optimized geometry, calculate a suite of electronic and topological descriptors:

- Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMO): Calculate the energies of the Highest Occupied (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied (LUMO) Molecular Orbitals.

- Electrostatic Potentials: Compute the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) surface.

- Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis: Perform NBO analysis to understand charge transfer and conjugative interactions.

- Vibrational Frequencies: Calculate the vibrational frequencies to confirm the structure is at a minimum and derive thermodynamic properties.

- Descriptor Compilation: Extract calculated numerical values (e.g., HOMO/LUMO energies, dipole moment, polarizability, atomic charges) to form the quantum chemical descriptor vector.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel application of these descriptor methodologies within a closed-loop optimization system.

Diagram 1: Multi-Descriptor Workflow for Closed-Loop Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Descriptor Research

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Closed-Loop Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [15] | Cheminformatics Library | Generation and manipulation of chemical structures (e.g., canonical SMILES). | Fundamental for pre-processing and featurizing molecular data in automated pipelines. |

| OMol25 Dataset [19] | Pre-computed Quantum Chemistry Dataset | Provides over 100 million high-accuracy DFT calculations for training and benchmarking. | Serves as a massive, high-quality source of data for training ML potentials and validating predictions. |

| eSEN/UMA Models [19] | Pre-trained Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Fast and accurate computation of molecular energies and forces. | Enables rapid energy evaluations in silico, replacing expensive quantum calculations in high-throughput screening. |

| MEHC-Curation [22] | Python Framework | Automated validation, cleaning, and normalization of molecular datasets (SMILES). | Ensures input data quality, which is critical for the reliability of any downstream optimization model. |

| MEDUSA Search [23] | Mass Spectrometry Search Engine | ML-powered identification of molecular formulas and reactions in large-scale HRMS data. | Allows "experimentation in the past" by mining undiscovered reactions from existing data, informing new optimization cycles. |

| TH588 hydrochloride | TH588 hydrochloride, MF:C13H13Cl3N4, MW:331.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Fumarate hydratase-IN-1 | Fumarate hydratase-IN-1, MF:C27H30N2O4, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of diverse molecular descriptors—from efficient data-driven vectors to interpretable fragment-based features and high-fidelity quantum chemical parameters—creates a powerful, multi-faceted representation strategy for closed-loop optimization systems. By leveraging the protocols and tools outlined in this document, researchers can construct robust and interpretable AI-driven platforms for accelerated organic reaction discovery and optimization.

The discovery and formulation of high-performance organic photoredox catalysts (OPCs) represent a significant challenge in modern synthetic chemistry due to the vast, multivariate nature of the search space. Conventional discovery, which often relies on design, trial and error, and serendipity, struggles with the complex interplay of optoelectronic properties and reaction conditions that dictate catalytic activity [2]. This case study details a data-driven approach that leverages sequential closed-loop Bayesian optimization to efficiently navigate this complexity, leading to the discovery of OPCs competitive with established iridium-based catalysts [2] [24]. The methodology and results presented herein serve as a foundational protocol within the broader thesis that closed-loop optimization is fundamentally reshaping research in organic reactions.

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

The following section outlines the core experimental workflow and provides detailed protocols for its implementation.

The discovery process employs a sequential two-step closed-loop optimization, illustrated in the diagram below.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Virtual Library Design and Molecular Encoding

This protocol covers the creation of a virtual chemical library and the numerical representation of molecules for machine learning.

- Principle: Construct a chemically diverse yet synthetically accessible virtual library. Encode each molecule using molecular descriptors that capture key physical properties to create a machine-readable search space [2].

- Procedure:

- Library Construction:

- Select a reliable and diversifiable molecular scaffold. The case study used the Hantzsch pyridine synthesis [2].

- Define a set of modular building blocks. The study combined 20 β-keto nitrile derivatives (Ra groups) with 28 aromatic aldehydes (Rb groups) to generate a virtual library of 560 cyanopyridine (CNP) molecules [2].

- Ensure synthetic feasibility and broad coverage of chemical moieties (e.g., electron-donating, electron-withdrawing, halogenated, polyaromatic hydrocarbons) to avoid class imbalance [2].

- Molecular Encoding:

- For each molecule in the virtual library, calculate a set of molecular descriptors using computational chemistry software.

- The case study used 16 descriptors capturing thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state properties [2].

- The resulting descriptor matrix (560 molecules x 16 descriptors) defines the chemical space for the optimization algorithm.

- Library Construction:

Protocol 2: Closed-Loop Bayesian Optimization for Catalyst Discovery

This protocol details the iterative machine learning-guided process for selecting which molecules to synthesize and test.

- Principle: Use Bayesian optimization to build a surrogate model that predicts reaction yield based on molecular descriptors. The algorithm sequentially selects the most informative molecules to test, balancing the exploration of unknown regions of chemical space with the exploitation of known high-yielding areas [2] [10].

- Procedure:

- Initialization:

- Select a small, diverse initial set of molecules from the virtual library using an algorithm like Kennard-Stone (KS) to ensure broad coverage. The case study began with 6 CNPs [2].

- Synthesis and Testing:

- Synthesize the selected CNP molecules via the Hantzsch pyridine synthesis.

- Test all catalysts under identical, standardized reaction conditions for the target transformation (e.g., decarboxylative cross-coupling). The case study used: 4 mol% CNP, 10 mol% NiCl₂·glyme, 15 mol% dtbbpy, 1.5 equiv. Cs₂CO₃, DMF, blue LED irradiation [2].

- Perform catalysis measurements in triplicate and report the average reaction yield.

- Model Building and Iteration:

- Build a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model using the acquired yield data and molecular descriptors [2] [10].

- Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to query the model and select the next batch of promising catalyst candidates for synthesis (e.g., 12 molecules per batch) [2].

- Update the GP model with new experimental results and repeat the cycle until performance converges or a resource limit is reached. The case study synthesized only 55 of 560 virtual candidates (≈10%) to discover high-performing catalysts [2].

- Initialization:

Protocol 3: Multi-Objective Formulation Optimization

This protocol describes the optimization of reaction conditions for a shortlist of promising catalysts.

- Principle: Once top catalyst candidates are identified, a second Bayesian optimization loop can efficiently find the optimal reaction formulation (e.g., catalyst and metal catalyst loadings, ligand concentration) to maximize performance [2].

- Procedure:

- Define Search Space:

- Select a subset of the best-performing catalysts from the first optimization (e.g., 18 OPCs).

- Define the continuous and categorical variables for optimization. This includes the OPC identity, nickel catalyst concentration, and ligand concentration, defining a space of 4,500 possible condition sets [2].

- Closed-Loop Optimization:

- Initialize a new Bayesian optimization run, often with a new GP model.

- The algorithm sequentially proposes reaction condition sets expected to maximize yield.

- Execute experiments, measure yields, and update the model. The case study evaluated only 107 of 4,500 possible conditions (≈2.4%) to achieve the highest yield [2].

- Define Search Space:

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The table below catalogs the essential reagents and their functions from the featured case study, constituting a core "Scientist's Toolkit" for this research domain.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Role in the Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanopyridine (CNP) Library | Organic photoredox catalysts (OPCs) with tunable optoelectronic properties [2]. | Core discovery target; synthesized via Hantzsch pyridine synthesis from β-keto nitriles and aromatic aldehydes. |

| NiCl₂·glyme | Transition-metal catalyst precursor [2]. | Essential component of the metallophotoredox system; enables cross-coupling cycle. |

| dtbbpy (4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine) | Ligand for the nickel catalyst [2]. | Coordinates to nickel, modulating its reactivity and stability in the catalytic cycle. |

| Cs₂CO₃ | Base [2]. | Facilitates key steps in the reaction mechanism, such as decarboxylation. |

| DMF Solvent | Reaction medium [2]. | Solubilizes reagents and catalysts. |

| Blue LED Light Source | Photon source for photoexcitation [2]. | Provides energy to excite the OPC, initiating the photoredox cycle. |

Results and Data

The sequential Bayesian optimization approach yielded significant performance improvements with high experimental efficiency. The quantitative results are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Summary of Optimization Performance and Results

| Optimization Metric | Catalyst Discovery Phase | Formulation Optimization Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Total Search Space Size | 560 virtual molecules [2] | 4,500 possible condition sets [2] |

| Number of Experiments Performed | 55 molecules synthesized & tested [2] | 107 conditions tested [2] |

| Experimental Fraction Explored | ~10% [2] | ~2.4% [2] |

| Initial Reaction Yield | 39% (best from initial 6 molecules) [2] | Not Specified |

| Final Optimized Yield | 67% (after catalyst discovery) [2] | 88% (after formulation optimization) [2] |

| Key Achievement | Identified high-performing OPCs from a vast virtual library. | Achieved performance competitive with iridium-based catalysts. |

Discussion

This case study exemplifies the transformative potential of closed-loop optimization in organic synthesis. The two-step Bayesian optimization strategy dramatically reduced the experimental burden, requiring the synthesis of only 10% of the catalyst library and testing of only 2.4% of the full reaction condition space to achieve high yields [2]. This represents a paradigm shift from traditional, resource-intensive screening methods.

The success of this methodology hinges on several factors: the careful design of a diverse and synthetically tractable virtual library, the intelligent encoding of molecular structures via physicochemical descriptors, and the efficient balancing of exploration and exploitation by the Bayesian optimization algorithm. This approach is particularly powerful for multivariate problems like photoredox catalysis, where performance depends on a complex, non-linear interplay of factors that is difficult to predict a priori [2] [25].

Integrating these protocols into a broader research thesis underscores a new paradigm: the future of organic reaction research lies in human-AI synergy [26]. The chemist's role evolves to focus on strategic design (defining the virtual library and objective) and interpreting results, while the AI-driven autonomous loop handles the high-dimensional exploration. This synergy accelerates discovery while maintaining chemical insight and understanding [26].

The pursuit of general reaction conditions represents a paramount challenge in synthetic organic chemistry, particularly in the context of pharmaceutical development where heterocyclic motifs are ubiquitous [27]. The Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling (SMC) reaction, a transformative method for constructing carbon-carbon bonds, faces significant limitations when applied to heteroaryl-heteroaryl couplings due to catalyst poisoning by Lewis basic sites inherent to heterocyclic substrates [27]. Traditional optimization approaches, which rely on one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) experimentation or extensive ligand screening, struggle to efficiently navigate the high-dimensional parameter spaces encompassing substrates, catalysts, ligands, and reaction conditions [28] [27].

This application note details a case study framed within a broader thesis on closed-loop optimization for organic reactions. It explores how the integration of machine learning (ML) with automated experimentation enabled the discovery of substantially improved, general conditions for heteroaryl SMC, doubling the average yield compared to a widely used benchmark [29].

Background and Significance

Heterocycles are fundamental components of modern pharmaceuticals, with a recent survey indicating that 82% of new FDA-approved drugs contain at least one N-heterocyclic unit [27]. Consequently, catalytic methods for forging C─C bonds between two heterocyclic motifs, such as the SMC reaction, are indispensable in drug discovery campaigns [27].

The Challenge of Heteroaryl-Heteroaryl Coupling

The primary obstacle in heteroaryl SMC lies in the propensity of Lewis basic heteroatoms (e.g., nitrogen, sulfur, oxygen) within both coupling partners to coordinate strongly and deactivate precious metal catalysts like Palladium and Nickel [27]. This necessitates the use of specially designed, bulky ligands to shield the metal center, often requiring practitioners to possess deep knowledge of reactivity profiles or to conduct laborious, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) ligand screens [27]. The result is a reliance on specialized, narrow conditions that lack generality across diverse substrate combinations.

The Paradigm of Closed-Loop Optimization

Recent advances are precipitating a paradigm shift in chemical reaction optimization [28]. Closed-loop optimization systems merge three critical components:

- Algorithmic Intelligence: Machine learning models, such as Bayesian optimization, guide the exploration of the reaction space.

- Robotic Experimentation: Automated liquid-handling platforms perform the physical experiments.

- Data-Guided Workflows: The algorithm selects experiments, the robot executes them, and the resulting data is fed back to update the model, creating an iterative, self-optimizing cycle [30] [29]. This approach allows for the synchronous optimization of multiple variables with minimal human intervention, making the exploration of vast chemical spaces practically feasible [28].

Case Study: Closed-Loop Optimization of Heteroaryl SMC

Objective and Challenges

The objective was to discover general reaction conditions for the challenging heteroaryl Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling. The search space for such a problem is astronomically large, derived from the cross product of a wide matrix of diverse substrates and a high-dimensional matrix of potential reaction conditions (catalyst, ligand, base, solvent, concentration, temperature, etc.) [29]. Exhaustive experimentation via traditional methods is therefore implausible.

Workflow and Implementation

A simple yet powerful closed-loop workflow was employed to efficiently navigate this vast search space [29]. The process is illustrated in the following diagram, which outlines the iterative cycle of data-guided down-selection, machine learning, and robotic experimentation.

- Data-Guided Matrix Down-Selection: The initial high-dimensional space was strategically reduced to a more manageable set of promising conditions for algorithmic evaluation [29].

- Uncertainty-Minimizing Machine Learning: A machine learning model (e.g., a Gaussian Process) was used to build a surrogate model of the reaction landscape. This model predicts reaction yield and, crucially, its own uncertainty. The algorithm then selects the next experiments to perform, often by balancing exploration (testing in uncertain regions) and exploitation (testing where high yields are predicted) [29].

- Robotic Experimentation: A liquid-handling robotic platform automatically prepared and conducted the chosen reactions, ensuring reproducibility and high-throughput data generation [30] [29].

- Closed-Loop Feedback: The results from the robotic experiments were fed back into the ML model, refining its understanding of the reaction landscape and informing the next round of experiments. This loop continued until optimal conditions were identified [29].

Key Outcomes and Performance

The application of this closed-loop workflow led to a significant breakthrough. The discovered conditions doubled the average yield of the heteroaryl SMC reaction compared to a previously established benchmark condition that had been developed using traditional optimization approaches [29]. This result underscores the power of closed-loop systems to uncover superior and more general reaction parameters that elude conventional methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Methods for Heteroaryl SMC

| Optimization Method | Key Characteristics | Efficiency | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (OVAT/HTE) | Relies on expert intuition; one-variable-at-a-time or extensive screening. | Low; labor-intensive and time-consuming. | Established benchmark conditions. |

| Closed-Loop (ML-Driven) | Synchronous multi-variable optimization; algorithmic guidance. | High; minimal human intervention. | Double the average yield vs. benchmark [29]. |

Complementary Research: "Naked Nickel" Catalytic System

In a parallel development relevant to simplifying these challenging couplings, researchers have reported an air-stable "naked nickel" catalyst, Ni(4-CF3stb)3, that operates effectively in the absence of exogenous ligands [27].

Protocol: Ni(4-CF3stb)3-Catalyzed Heteroaryl SMC

Reaction Setup: An oven-dried vial was equipped with a magnetic stir bar and sealed with a septum under an inert atmosphere. Charge Substrates: * Heteroaryl bromide (e.g., 3-bromopyridine, 1.0 equiv., 0.3 mmol) * Heteroaryl boronic acid (e.g., 3-thienylboronic acid, 1.5 equiv.) * K₃PO₄ base (2.0 equiv.) Add Solvent: DMA (Dimethylacetamide) was added to achieve a concentration of 0.5 M. Add Catalyst: Ni(4-CF3stb)₃ (10 mol%) was introduced. Reaction Conditions: The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 16 hours. Work-up and Isolation: The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with ethyl acetate, and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was dried over MgSO₄, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography to afford the desired heterobiaryl product.

Substrate Scope and Limitations

This catalytic system demonstrated remarkable generality, accommodating a wide range of 6-membered heteroaryl bromides (pyridines, pyrimidines, pyrazines, isoquinolines, quinazolines) coupled with 5- and 6-membered heterocyclic boron-based nucleophiles [27]. The system tolerates various functional groups, including esters, nitriles, and protected amino acids. A key limitation noted was the poor performance with potassium trifluoroborate (BF₃K) nucleophiles [27].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Heteroaryl SMC

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ni(4-CF3stb)₃ Catalyst | Air-stable Ni(0) pre-catalyst; operates without exogenous ligands. | CAS: 2413906-36-0; simplifies setup and avoids ligand screening [27]. |

| Heteroaryl Bromides | Electrophilic coupling partner. | 3-Bromopyridine, bromoquinoline, bromopyrimidine [27]. |

| Heteroaryl Boron Reagents | Nucleophilic coupling partner. | Boronic acids (e.g., 3-thienylboronic acid) and pinacol esters (Bpin) perform well [27]. |

| K₃PO₄ Base | Inorganic base crucial for transmetalation step. | Identified as optimal base in DMA solvent [27]. |

| DMA (Dimethylacetamide) | Polar aprotic solvent. | 0.5 M concentration was used in the optimized protocol [27]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit for Closed-Loop Optimization

Implementing a closed-loop optimization system for organic reactions requires a suite of specialized tools and algorithms. The following table details the key components.

Table 3: Essential Components of a Closed-Loop Optimization System

| Toolkit Component | Description | Application in Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Robotic platform for precise, high-throughput dispensing of reagents. | Executes the experiments selected by the algorithm without researcher intervention [30] [29]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A machine learning technique that balances exploration and exploitation. | Guides the search for optimal conditions by modeling the reaction landscape and uncertainty [2]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic model used as a surrogate for the objective function. | The core of many BO algorithms; predicts reaction yield and uncertainty from experimental parameters [2]. |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical representations of chemical structures or properties. | Encodes molecules (e.g., catalysts, substrates) for the ML model; can range from simple (OHE) to complex (DFT-calculated) [30] [2]. |

| Active Learning | An iterative algorithm that selects the most informative data points. | Decides which experiments to run next to maximize learning and performance gains [30]. |

| Rociletinib hydrobromide | Rociletinib hydrobromide, CAS:1446700-26-0, MF:C27H29BrF3N7O3, MW:636.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SCR-1481B1 | SCR-1481B1, MF:C28H29ClF2N5O10P, MW:700.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Algorithmic Considerations

The choice of molecular descriptor is critical. A key finding from related closed-loop research is that complex descriptors (e.g., derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT)) do not necessarily outperform simple representations (like one-hot encoding, OHE) in these optimization tasks [30]. Furthermore, initializing the optimization with a larger initial dataset, even with less informative descriptors, often delivers better performance than a small dataset with highly complex descriptors [30].