Closed-Loop Optimization of Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling: Accelerating Reaction Discovery for Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing closed-loop optimization for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions.

Closed-Loop Optimization of Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling: Accelerating Reaction Discovery for Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing closed-loop optimization for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions. It bridges foundational mechanistic principles with advanced AI-driven methodologies, offering practical strategies for troubleshooting common challenges like protodeboronation and halide inhibition. The content covers high-throughput experimentation (HTE) workflows, validation protocols aligned with ICH guidelines, and comparative analysis with traditional optimization approaches. By synthesizing recent advances in palladium catalysis, boron reagent stability, and reinforcement learning, this resource aims to equip scientists with a systematic framework for accelerating the development of robust, scalable C–C bond-forming reactions critical to pharmaceutical synthesis.

Suzuki-Miyaura Reaction Fundamentals and the Need for Advanced Optimization

The Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction stands as a powerful method for carbon–carbon bond formation, widely applied across various substrates, catalysts, reagents, and solvents [1]. At the heart of this transformative reaction lies a catalytic cycle primarily mediated by palladium or nickel complexes, revolving around three fundamental organometallic steps: oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination. Understanding these core mechanistic steps is crucial for the closed-loop optimization of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling research, where iterative feedback between experimental data and reaction parameters leads to progressively refined and efficient synthetic protocols. This application note details these pivotal steps within an optimization framework, providing structured protocols, quantitative data summaries, and visual workflows to accelerate research in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

The catalytic cycle begins with oxidative addition, where the metal catalyst inserts into the carbon-halogen bond of an organic electrophile, increasing its oxidation state by two units. Subsequent transmetalation involves the transfer of an organic group from the boron-based nucleophile to the metal center. Finally, reductive elimination forms the new carbon-carbon bond while regenerating the active catalyst. Each of these steps presents unique optimization challenges and opportunities that will be explored in the subsequent sections, with a focus on practical implementation for research scientists.

Core Mechanistic Steps

Oxidative Addition

Oxidative addition represents the initial and often rate-determining step in the Suzuki-Miyaura catalytic cycle. During this process, a Pd(0) or Ni(0) complex inserts into the carbon-halogen (C-X) bond of an aryl or vinyl halide, resulting in a metal dihalide complex where the metal oxidation state increases by two units [2]. This step is critical for establishing the subsequent connectivity in the final biaryl product and dictates much of the substrate scope and functional group tolerance of the overall transformation.

Mechanistic Pathways: Oxidative addition proceeds through three primary mechanistic pathways, each with distinct characteristics and substrate preferences:

Concerted Mechanism: This pathway occurs in a single synchronous step without discrete ionic intermediates, typically favored for non-polarized substrates such as C-H bonds and dihydrogen [2]. The reaction proceeds through a three-centered transition state where the sigma (σ) bond of the substrate adds across the metal center. A classic example is the reaction of Vaska's complex (trans-IrCl(CO)[P(C₆H₅)₃]₂) with dihydrogen, where the two hydrogen atoms initially adopt cis geometry before potential isomerization [2].

Non-Concerted (SN2) Mechanism: This pathway mirrors a nucleophilic displacement (SNâ‚‚) reaction and is predominant with polarized substrates such as methyl, allyl, and benzyl halides [2]. The metal center acts as a nucleophile, attacking the carbon atom of the organic halide with concomitant halide departure. Evidence for this mechanism includes the inversion of stereochemistry observed with optically active substrates.

Radical Mechanism: Alkyl halides can engage with metal centers through radical pathways, which are further categorized into non-chain and chain mechanisms [2]. These reactions are particularly sensitive to dioxygen due to its paramagnetic nature, which can interfere with radical intermediates. This mechanism can lead to various byproducts, including those resulting from radical recombination or termination events.

Transmetalation

Transmetalation constitutes the transfer of an organic group from the boron-based nucleophile (organoboronic acid or ester) to the metal center of the dihalide complex formed during oxidative addition. This step generates a diorganometallic species primed for the final bond-forming reductive elimination. The transmetalation process in Suzuki-Miyaura coupling is unique in its reliance on a base activator, which enhances the nucleophilicity of the boronate species.

Activation Cycle: The base plays a crucial role in generating a more nucleophilic tetracoordinate boronate anion from the tricoordinate boronic acid precursor. This activated species then transfers its organic group to the metal, with the coordination sphere and ligand environment significantly influencing the kinetics and selectivity of this process. The metal (M) involved in transmetalation can vary, including Sn, Zn, B, and Zr, with boron being characteristic of the Suzuki-Miyaura paradigm [2].

Reductive Elimination

Reductive elimination is the culminating bond-forming step in the catalytic cycle, wherein the two organic ligands on the metal center couple to form the new carbon-carbon bond. This process decreases the metal oxidation state by two units and reduces its coordination number, thereby regenerating the active catalyst for subsequent turnover [2].

Stereoelectronic Requirements: Reductive elimination is an intramolecular process that requires the two reacting groups to be adjacent (cis) to one another in the metal coordination sphere [2]. Consequently, isomerization steps often precede elimination when the groups are trans. The reaction is favored at metal centers with low electron density, which can be modulated through judicious ligand selection. This electronic influence provides a critical leverage point for optimizing overall catalytic efficiency.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Metals in Cross-Coupling Catalytic Cycles

| Metal Catalyst | Oxidative Addition | Transmetalation | Reductive Elimination | Typical Ligands | Relative Rate | Substrate Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium (Pd) | Broad scope with Ar-X [1] | With B compounds [2] | Highly favorable [2] | Phosphines, NHCs | Fast | Very Broad |

| Nickel (Ni) | Broader scope incl. Ar-OTf | With B compounds [2] | Can be slower | Phosphines, Bipyridyl | Moderate | Extended |

| Gold (Au) | Demonstrated with Ar-I [3] | With Zn compounds [3] | Demonstrated for biaryl [3] | Bipyridyl | Slow | Emerging |

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling Steps [1]

| Mechanistic Step | Key Influencing Factors | Optimization Levers | Common Challenges | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Addition | Catalyst oxidation potential, Halide leaving group (I > Br > Cl), Aryl ring electronics, Steric hindrance | Ligand selection (electron-rich favors oxidation), Pre-catalyst activation, Solvent polarity | Slow with electron-poor/sterically hindered aryl halides | Use Pd(0) sources, Electron-donating ligands, Elevated temperature |

| Transmetalation | Base strength and concentration, Boron reagent hydrolysis, Solvent coordination | Base choice (Cs₂CO₃, K₃PO₄), Aqueous/organic biphasic systems, Boronic acid protection as esters | Protodeboronation, Homocoupling | Controlled base stoichiometry, Anhydrous conditions, Slow boronate addition |

| Reductive Elimination | Electron density at metal center, Cis geometry of aryl groups, Steric bulk of ligands | Electron-withdrawing ligands, Forcing steric environments (Buchwald-type ligands), Temperature | β-Hydride elimination with alkyl groups | Ligand design (bulky, monodentate), Spacious coordination geometry |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling

Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Specifications & Handling | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium Catalyst | Catalytic cycle initiation/mediation | Pd(II) salts (e.g., Pd(OAc)â‚‚) or Pd(0) (e.g., Pd(dba)â‚‚); Stored under inert atmosphere | Pre-catalysts often require reduction to active Pd(0) species [1] |

| Phosphine/NHC Ligands | Modifies electron density/sterics at metal center | e.g., Triphenylphosphine, SPhos, XPhos; Air-sensitive, store under Nâ‚‚/Ar | Electron-rich ligands favor oxidative addition; Bulky ligands favor reductive elimination [1] |

| Aryl Halide | Electrophilic coupling partner | Aryl iodide, bromide, or triflate; Purified prior to use | Reactivity order: I > OTf > Br >> Cl; Electronics affect oxidative addition rate [1] |

| Aryl Boronic Acid | Nucleophilic coupling partner | Typically solid; Check for dehydration (boroxine formation) | Can undergo protodeboronation in strong basic conditions; Pinacol esters offer stability |

| Base Activator | Activates boronic acid via boronate formation | Carbonates (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, K₂CO₃) or phosphates (e.g., K₃PO₄) | Choice affects transmetalation rate and boronic acid stability; Solubility is key [1] |

| Solvent System | Reaction medium | Often biphasic (e.g., Toluene/Hâ‚‚O, DME/Hâ‚‚O) or homogeneous (DMF, DMSO) | Must dissolve reagents and facilitate interaction between organic and inorganic phases |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Title: Optimization of Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling via Closed-Loop Feedback

Protocol ID: SM-OPT-001

Objective: To provide a standardized, optimized procedure for the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction between 4-bromotoluene and phenylboronic acid, with detailed monitoring of each mechanistic step for continuous optimization.

Materials and Setup:

- Reagents: Refer to Table 3 for the complete list.

- Equipment: Schlenk flask (50 mL), magnetic stirrer, heating mantle, reflux condenser, syringe/septa setup for inert atmosphere (Nâ‚‚ or Ar), TLC plate, UV lamp.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: In a flame-dried Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, evacuate and backfill with inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) three times.

- Catalyst Formation: Under a positive flow of inert gas, charge the flask with the palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(OAc)â‚‚, 2 mol%) and ligand (e.g., SPhos, 4 mol%). Add degassed toluene (5 mL) and stir for 15 minutes at room temperature to form the active catalytic species.

- Substrate Addition: Sequentially add 4-bromotoluene (1.0 mmol, 171 mg) and a degassed aqueous solution of the base (e.g., K₂CO₃, 2.0 mmol in 2 mL H₂O).

- Oxidative Addition Monitoring: Heat the mixture to 50°C and monitor by TLC or in-situ spectroscopy for 30-60 minutes to track the consumption of the aryl halide (Oxidative Addition phase).

- Transmetalation Initiation: After the initial period, add phenylboronic acid (1.2 mmol, 146 mg) dissolved in a minimal amount of degassed ethanol. Increase the temperature to 80-90°C to commence reflux.

- Reaction Progress: Monitor the reaction closely by TLC (e.g., Hexanes:Ethyl Acetate 9:1) every 30 minutes until the boronic acid spot diminishes significantly, indicating progression through transmetalation and completion.

- Work-up: After completion (typically 2-8 hours), cool the reaction mixture to room temperature. Add water (10 mL) and extract with ethyl acetate (3 x 15 mL). Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous MgSOâ‚„, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography to yield 4-methylbiphenyl.

Troubleshooting and Optimization:

- Low Conversion: Increase catalyst loading (to 5 mol%), use a more active ligand, increase temperature, or extend reaction time.

- Homocoupling: Ensure boronic acid is fresh and anhydrous, reduce base concentration, or employ a slower addition of the boronic acid.

- Protodeboronation: Use boronic ester instead of the acid, lower the reaction temperature, or reduce the base strength.

Workflow and System Diagrams

Catalytic Cycle

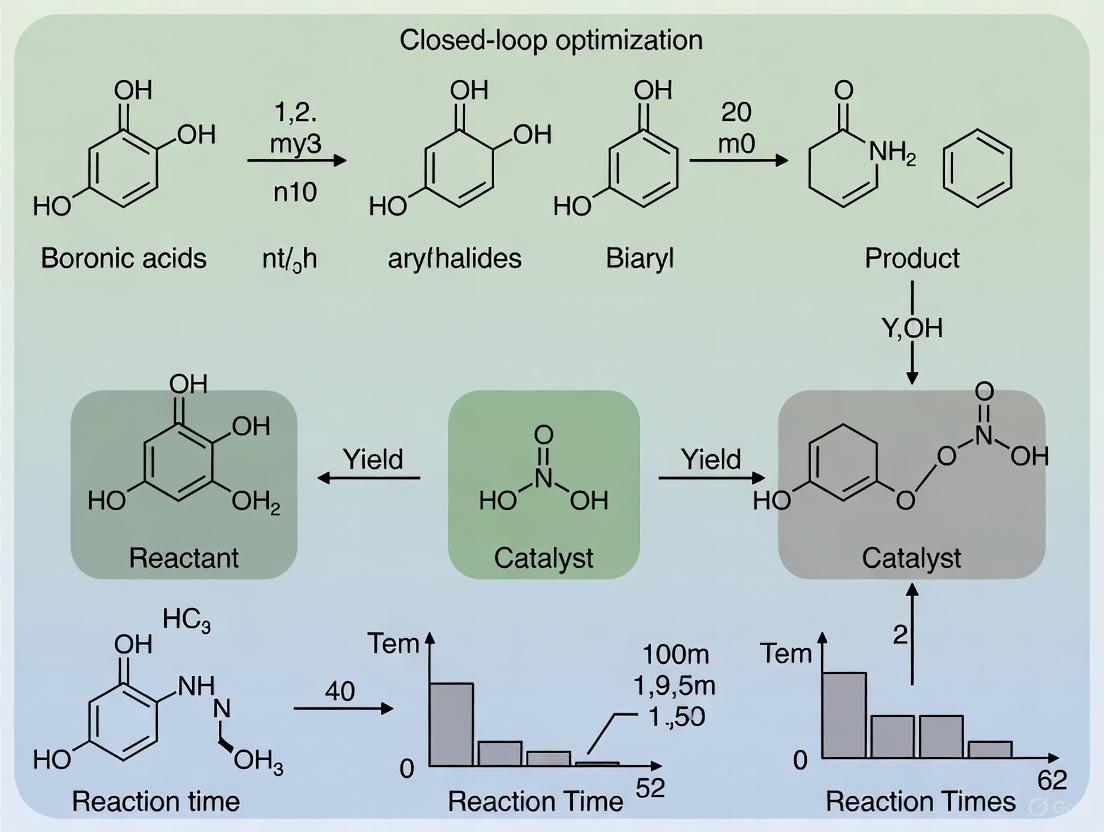

Closed-Loop Optimization

Despite significant advancements in synthetic methodology, a striking analysis reveals that over 80% of current Suzuki-Miyaura reactions still rely on pre-2003 conditions [4]. This persistent dependency creates a substantial optimization gap in modern synthetic chemistry, particularly within pharmaceutical development and research laboratories where efficiency, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness are paramount. This application note dissects the root causes of this lag, provides updated experimental protocols addressing key limitations, and frames these solutions within a closed-loop optimization system for continuous reaction improvement.

The reluctance to transition from established protocols stems from multiple interconnected factors: the sheer volume of available literature makes identifying optimal conditions time-consuming [4], perceived risks associated with new catalyst systems, and scalability concerns with modern methodologies. Furthermore, traditional approaches often prioritize initial reaction setup speed over holistic process efficiency, ignoring long-term benefits of improved catalysts and conditions.

Analysis of Pre-2003 Condition Limitations

Key Technical Limitations of Legacy Systems

Traditional Suzuki-Miyaura reactions employing pre-2003 conditions face several critical technical constraints that impact their efficiency and applicability in modern synthetic contexts, particularly for pharmaceutical development and complex molecule synthesis.

Limited Electrophile Scope: Traditional palladium-phosphine catalyst systems exhibit poor reactivity with challenging electrophiles like aryl chlorides and sterically hindered substrates due to difficult oxidative addition [4] [5]. These systems often require high catalyst loadings (1-5 mol%) and elevated temperatures to achieve reasonable conversion rates.

Boron Source Instability: Conventional boronic acids suffer from protodeboronation under basic reaction conditions, particularly with heteroaryl and electron-deficient substrates [4]. This side reaction reduces yields and complicates purification, especially in large-scale applications.

Ligand Constraints: Traditional triarylphosphine ligands (PPh₃) demonstrate limited performance for challenging coupling partners and offer poor stabilization of the active catalytic species [4] [5]. More effective bulky, electron-rich ligands developed more recently remain underutilized.

Solvent System Limitations: Aqueous-organic biphasic mixtures used in legacy systems often cause halide inhibition where soluble halide-byproducts slow transmetalation, a particular issue in polar solvents like THF [4].

Economic and Practical Drivers of the Status Quo

The persistence of outdated methodologies stems from several practical considerations that create resistance to adopting improved systems, despite their technical advantages.

Protocol Proliferation: The vast number of reported Suzuki-Miyaura protocols creates a selection paralysis for researchers [4], who often default to familiar conditions rather than spending significant time exploring alternatives.

Risk Aversion: Pharmaceutical process chemistry prioritizes reproducibility and predictability, creating disincentives for adopting new catalytic systems with perceived validation risks [6].

Knowledge Transfer Gaps: Many recent advances remain confined to specialized literature, with insufficient practical guidance for implementation across diverse substrate classes [1].

Table 1: Economic and Practical Challenges in Adopting Modern Suzuki-Miyaura Conditions

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| Information Overload | Hundreds of ligand/reagent combinations described [4] | Researchers default to familiar systems to reduce decision complexity |

| Validation Burden | Required re-optimization for new conditions | Perceived as more time-consuming than using sub-optimal but familiar conditions |

| Scalability Uncertainty | Limited large-scale validation data for newer catalysts [6] | Process chemists hesitate to implement new systems without demonstrated scale-up |

| Cost Considerations | Perception that newer ligands/catalysts are prohibitively expensive | Actual cost savings from reduced Pd levels and improved yields not fully appreciated |

Modern Catalytic Solutions and Research Reagent Toolkit

Advanced Catalyst Systems

Recent research has addressed the limitations of traditional systems through designed ligands and earth-abundant metal catalysts that offer superior performance across diverse substrate classes.

Palladium-Schiff Base Complexes: Schiff base ligands provide stable, tunable coordination environments for palladium, enabling activation of challenging aryl chlorides under mild conditions with catalyst loadings as low as 0.1 mol% [5]. These nitrogen-based ligands offer advantages over traditional phosphines in terms of air stability, synthetic accessibility, and cost-effectiveness [5].

Nickel Catalysis with specialized ligands: Nickel-based catalysts present a compelling alternative due to nickel's lower cost, higher earth abundance, and reduced metal-removal requirements in pharmaceutical synthesis [7]. Recent developments, such as the (tri-ProPhos)Ni system, enable coupling of challenging heteroaromatics in green solvents (i-PrOH/Hâ‚‚O) with catalyst loadings as low as 0.03-0.1 mol% [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Modern Research Reagent Toolkit for Suzuki-Miyaura Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Systems | Tri-ProPhos [7], Schiff bases [5], Dppf [4] | Control catalyst activity, stability, and selectivity; enable challenging couplings |

| Boron Sources | Neopentyl glycol boronates [4], Glycol boronic esters [4] | Balance stability against reactivity; reduce protodeboronation |

| Bases | TMSOK (potassium trimethylsilanolate) [4], K₃PO₄ [7] | Facilitate transmetalation; impact boronate formation kinetics |

| Solvents | 2-MeTHF [4], i-PrOH/Hâ‚‚O mixtures [7] | Reduce halide inhibition; improve green chemistry metrics |

| Additives | Trimethyl borate [4], Lewis acids [4] | Enhance rates and selectivity; prevent catalyst poisoning |

| Quinine hemisulfate | Quinine hemisulfate, MF:C40H50N4O8S, MW:746.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cassamine | Cassamine, CAS:471-71-6, MF:C25H39NO5, MW:433.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Legacy Limitations

Protocol 1: (tri-ProPhos)Ni-Catalyzed Coupling in Green Solvents

This protocol enables efficient coupling of challenging heteroaromatic substrates, including those prone to catalyst poisoning (e.g., 3-pyridinyl boronic acids), using a low-cost, sustainable nickel catalytic system [7].

Reaction Setup:

Procedure:

- Charge reactor with NiCl₂·6H₂O, tri-ProPhos ligand, and i-PrOH/H₂O solvent mixture

- Stir at 25°C for 10 minutes to form active catalyst

- Add aryl halide, boronic acid, and K₃PO₄ sequentially

- Heat reaction mixture to 60-80°C with continuous stirring

- Monitor reaction completion by TLC or HPLC (typically 6-16 hours)

- Cool to room temperature and concentrate under reduced pressure

- Purify by flash chromatography or recrystallization

Key Advantages: This system achieves exceptional functional group tolerance with heterocycles and enables coupling in sustainable solvent systems. The catalyst is air-stable and cost-effective for large-scale applications [7].

Protocol 2: Pd-Schiff Base Catalyzed Coupling of Aryl Chlorides

This protocol demonstrates the activation of challenging aryl chlorides under mild conditions using well-defined palladium-Schiff base complexes [5].

Reaction Setup:

Procedure:

- Prepare Pd-Schiff base catalyst according to literature procedures [5]

- Charge reactor with catalyst, aryl chloride, and solvent

- Add boronic acid/ester and base

- Purge reaction vessel with inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar)

- Heat to target temperature with efficient stirring

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC/HPLC

- Upon completion, filter through celite pad

- Concentrate and purify product by recrystallization or chromatography

Key Advantages: Low catalyst loading (0.1-0.5 mol%), mild reaction conditions for aryl chlorides, and excellent functional group tolerance compared to traditional Pd/PPh₃ systems [5].

Closed-Loop Optimization Framework

Modern Suzuki-Miyaura reaction optimization can be significantly enhanced through implementation of a closed-loop system that integrates real-time data analysis with automated experimentation. This approach directly addresses the historical reliance on suboptimal conditions by creating a continuous improvement cycle.

The workflow creates a self-optimizing chemical system where each experiment informs subsequent iterations, dramatically accelerating the identification of optimal conditions compared to traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches. This methodology is particularly valuable for rapidly adapting reaction conditions to new substrate classes and optimizing for multiple objectives simultaneously (yield, cost, sustainability).

Implementation Recommendations

Strategic Adoption Pathway

Transitioning from legacy systems to modern Suzuki-Miyaura conditions requires a phased implementation strategy to minimize risk while maximizing benefits:

- Stage 1: Benchmarking - Conduct side-by-side comparisons of traditional vs. modern catalytic systems for specific substrate classes of interest

- Stage 2: Pilot Implementation - Apply promising modern conditions to small-scale synthetic campaigns (1-10 gram)

- Stage 3: Process Intensification - Optimize successful systems for scale-up considering engineering factors (mixing, heat transfer, etc.)

- Stage 4: Closed-Loop Integration - Implement automated optimization cycles for critical synthetic steps

Knowledge Management Solutions

To address the information overload that perpetuates reliance on outdated conditions:

- Create organization-specific catalyst selection databases with performance metrics across substrate classes

- Develop decision-tree algorithms for condition selection based on substrate features

- Implement electronic lab notebook systems with automated data extraction for continuous model improvement

The persistent 80% reliance on pre-2003 Suzuki-Miyaura conditions represents a significant opportunity cost for synthetic efficiency across pharmaceutical and fine chemical development. By implementing the modern catalytic systems and closed-loop optimization approaches described in this application note, research organizations can systematically overcome the technical and practical barriers perpetuating this optimization gap. The presented protocols and frameworks provide a concrete pathway toward more sustainable, cost-effective, and efficient cross-coupling methodologies that leverage two decades of catalytic innovation.

The Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction stands as one of the most significant carbon-carbon bond-forming transformations in modern organic synthesis, with indispensable applications in pharmaceutical development, materials science, and natural product synthesis [4]. Despite its widespread adoption, traditional optimization approaches for these reactions face significant constraints that limit their efficiency and applicability. These limitations become particularly evident when contrasted with emerging closed-loop optimization methodologies, which represent a paradigm shift in chemical reaction development [8]. This application note details the key constraints—time, resources, and substrate scope—within the context of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling research, providing researchers with detailed protocols for both understanding and addressing these challenges.

The fundamental challenge in traditional optimization lies in the exponential complexity of multidimensional chemical space. As the number of reaction parameters increases, exhaustive experimentation becomes practically impossible, forcing researchers to rely on suboptimal conditions or narrow experimental designs [8]. This document quantitatively analyzes these constraints and provides structured methodologies for researchers navigating these limitations in drug development environments.

Time Constraints in Traditional Optimization

Time constraints represent one of the most significant bottlenecks in traditional reaction optimization. These limitations manifest primarily through extensive manual experimentation requirements, lengthy parameter screening processes, and slow knowledge integration from historical data.

Quantitative Analysis of Time Requirements

Table 1: Time Investment Analysis for Traditional Suzuki-Miyaura Optimization

| Optimization Phase | Experimental Setup (Hours) | Execution & Analysis (Hours) | Iteration Cycle (Hours) | Total Project Time (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Screening | 8-16 | 24-72 | 48-96 | 10-21 |

| Ligand Selection | 4-8 | 24-48 | 48-72 | 7-14 |

| Solvent/Base Optimization | 4-8 | 24-48 | 48-72 | 7-14 |

| Substrate Scope Exploration | 8-16 | 72-144 | 96-168 | 18-35 |

| Scale-up Studies | 8-12 | 48-96 | 72-144 | 14-26 |

The temporal demands documented in Table 1 create substantial bottlenecks in research timelines. Recent SciFinder analysis indicates that over 80% of current Suzuki-Miyaura reactions still rely on pre-2003 conditions, highlighting the slow adoption of newer methodologies despite their potential advantages [4]. This inertia stems largely from the significant time investment required to validate new reaction systems against established protocols.

Protocol: Rapid Assessment of Reaction Parameters

Objective: Efficiently identify critical reaction parameters for Suzuki-Miyaura optimization while minimizing time investment.

Materials:

- Palladium catalysts: Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd(dppf)Cl₂, Pd(OAc)₂ with selected ligands

- Bases: K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, K₃PO₄, TMSO (potassium trimethylsilanolate)

- Solvents: toluene, 1,4-dioxane, DMF, 2-Me-THF, water cosolvent systems

- Boron sources: boronic acids, neopentyl glycol boronates, pinacol esters

Procedure:

- Design of Experiments (DoE) Setup

- Employ a fractional factorial design (Resolution IV) to screen 5 parameters simultaneously with 16 experiments

- Prioritize factors: catalyst loading (1-5 mol%), ligand type (monodentate vs. bidentate), base strength, solvent polarity, temperature

- Include center points to assess curvature and model adequacy

Parallel Reaction Setup

- Utilize carousel reaction stations for simultaneous execution of 8-16 reactions

- Employ Schlenk techniques for oxygen-sensitive catalysts under nitrogen atmosphere

- Preheat heating blocks to target temperatures (50-110°C) prior to reaction initiation

Rapid Analysis Protocol

- Quench aliquots (50 μL) in acetonitrile (1 mL) with internal standard

- Analyze by UPLC-MS with short runtime methods (<3 minutes)

- Quantify conversion by relative peak area against internal standard

Data Analysis

- Construct response surface models to identify significant factor interactions

- Prioritize factors showing statistically significant effects (p<0.05)

- Identify regions of operability for further refinement

Troubleshooting:

- If no clear optimum emerges, expand design to include additional catalyst systems

- For reactions showing poor reproducibility, evaluate moisture sensitivity of reagents

- When protodeboronation is observed, switch to more stable boron sources (e.g., MIDA boronates, glycal boronates)

Resource Constraints in Reaction Optimization

Resource limitations present critical barriers to comprehensive reaction optimization, particularly when working with precious catalysts, specialized ligands, or complex substrate libraries.

Resource Allocation Challenges

Table 2: Resource Constraints in Suzuki-Miyaura Reaction Optimization

| Constraint Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Optimization | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Resources | High-cost palladium catalysts (≥$500/g for specialized ligands); Limited budget for substrate library acquisition | Restricted catalyst screening; Limited substrate diversity in scope studies | Use of catalyst pre-screening kits; Prioritization of cost-effective phosphine ligands; Collaborative reagent sharing programs |

| Material Limitations | Limited availability of specialized boronic acids (heteroaryl, polyfluorinated); Air-sensitive phosphine ligands | Incomplete assessment of reaction generality; Excluded challenging substrate classes | Strategic use of stable boron sources (pinacol esters, glycal boronates); Focus on most relevant substrate classes for drug development |

| Equipment Access | Limited high-throughput screening platforms; Restricted analytical instrument time | Reduced experimental throughput; Delayed analytical results | Scheduling optimization; Implementation of rapid UPLC methods; Use of preselection algorithms to minimize experiments |

| Human Resources | Technician availability for reaction setup and monitoring; Data analysis expertise | Extended project timelines; Suboptimal experimental design | Cross-training laboratory personnel; Implementation of electronic lab notebooks with automated data analysis templates |

The resource constraints detailed in Table 2 frequently force researchers into suboptimal compromises. The Theory of Constraints (TOC) framework provides a systematic approach to addressing these limitations by identifying the single most limiting resource (the constraint) and systematically optimizing its utilization [9]. For Suzuki-Miyaura optimization, this often involves identifying whether catalyst cost, substrate availability, or analytical throughput presents the primary constraint and re-engineering the workflow accordingly.

Protocol: Resource-Efficient Catalyst and Ligand Screening

Objective: Maximize screening efficiency while minimizing consumption of precious catalysts and ligands.

Materials:

- Catalyst stocks: Pd₂(dba)₃, Pd(OAc)₂, PdCl₂(MeCN)₂, Pd(PhCN)₂Cl₂

- Ligand library: PPh₃, XPhos, SPhos, XantPhos, dppf, RuPhos

- Substrate pairs: 4-bromoanisole with phenylboronic acid (benchmark); Challenging pairs (heteroaryl halides with heteroaryl boronates)

- 96-well microtiter plates with PTFE-coated septa

Procedure:

- Stock Solution Preparation

- Prepare catalyst solutions (0.1 M in THF or toluene) under inert atmosphere

- Formulate ligand solutions (0.2 M in appropriate solvent) with stability considerations

- Create substrate master mixes for efficient dispensing

Microscale Reaction Setup

- Dispense substrates (0.5 μmol scale in 100 μL total volume) using liquid handling systems

- Employ catalyst/ligand combinations in glove box or using Schlenk techniques

- Implement n=2 replication for critical combinations to assess reproducibility

High-Throughput Analysis

- Utilize LC-MS with automated sample injection from 96-well format

- Apply short gradient methods (3-5 minutes) with core-shell columns for rapid separation

- Implement automated data processing with conversion calculations

Hit Identification

- Set threshold criteria: ≥80% conversion for benchmark reaction; ≥50% for challenging substrates

- Prioritize catalyst/ligand systems showing broad applicability across substrate classes

- Apply cost-benefit analysis for promising but expensive systems

Troubleshooting:

- If precipitation occurs in microscale format, adjust solvent composition or increase dilution

- For inconsistent results across plates, verify atmospheric control and mixing efficiency

- When benchmark reactions underperform, validate reagent quality and solution concentrations

Substrate Scope Limitations

The generality of reaction conditions represents a fundamental challenge in Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, particularly for pharmaceutically relevant heteroaryl systems that often exhibit poor reactivity or stability under standard conditions.

Substrate-Dependent Reactivity Challenges

The challenges illustrated above necessitate specialized approaches for different substrate classes. Recent mechanistic insights reveal that transmetalation is typically the rate-determining step, with pathways strongly influenced by ligand electronics, base strength, and solvent polarity [4]. Furthermore, certain heteroaryl boronates exhibit pH-dependent stability, with protodeboronation rates varying by a factor of ten across different heterocyclic systems [4].

Protocol: Challenging Substrate Evaluation

Objective: Systematically evaluate and optimize reaction conditions for problematic substrate classes.

Materials:

- Problematic substrates: 2-pyridyl boronates, ortho-substituted arenes, electron-deficient heterocycles, base-sensitive systems

- Specialized reagents: neopentyl glycol boronates, potassium trimethylsilanolate (TMSOK), trimethyl borate

- Ligands for challenging substrates: sterically hindered alkylphosphines (tBuXPhos), electron-deficient arylphosphines

Procedure:

- Substrate Stability Assessment

- Conduct preliminary stability studies under reaction conditions without coupling partner

- Monitor for protodeboronation, hydrolysis, or decomposition by UPLC-MS

- Identify stability thresholds for temperature, pH, and solvent composition

Reaction Condition Templating

- For electron-deficient systems: Employ electron-rich ligands (RuPhos, tBuBrettPhos) with Cs₂CO₃ base in toluene/water

- For heteroaryl systems: Implement neopentyl glycol boronates with K₃PO₄ in dioxane/water at 80°C

- For base-sensitive substrates: Utilize TMSOK in anhydrous THF with Pd-XPhos catalyst system

- For sterically hindered partners: Apply Pd-P(tBu)₃ with high temperature (100-120°C) in toluene

Mechanistic Probes

- Employ competition experiments to assess relative rates of oxidative addition

- Use Hammett studies to quantify electronic effects on transmetalation

- Implement kinetic profiling to identify rate-determining steps for specific substrate pairs

Generality Assessment

- Apply optimized conditions to minimum 15-substrate library spanning electronic and steric diversity

- Include pharmaceutically relevant motifs: pyridines, pyrimidines, azaindoles, saturated heterocycles

- Benchmark against literature standards using standardized metrics (yield, functional group tolerance)

Troubleshooting:

- For substrates prone to protodeboronation, reduce reaction temperature and employ stable boron sources

- When halide inhibition occurs, switch to less polar solvents (toluene instead of THF) to limit halide salt dissolution

- If transmetalation is slow, consider borate additives or alternative bases to enhance boronate formation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Addressing Suzuki-Miyaura Optimization Constraints

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Constraint Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium Sources | Pd(OAc)₂, Pd₂(dba)₃, Pd(PhCN)₂Cl₂ | Catalytic center for cross-coupling; Variation in precursor affects active species formation | Resource constraints through cost-effective selection; Time through predictable performance |

| Ligand Systems | PPh₃ (electron-deficient), XPhos (bulky alkylphosphine), dppf (bidentate) | Modulate catalyst activity, stability, and selectivity; Impact oxidative addition and transmetalation rates | Substrate scope through tailored reactivity; Time through reduced optimization cycles |

| Boronic Acid Derivatives | Boronic acids, pinacol esters, neopentyl glycol esters, MIDA boronates | Trade-off between reactivity and stability; pH-dependent behavior varies by substrate | Substrate scope for challenging heteroaryls; Resource through improved shelf-life |

| Base Systems | K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, K₃PO₄, TMSOK | Affect boronate formation and transmetalation rate; Impact solubility and phase transfer | Substrate scope for base-sensitive motifs; Time through enhanced reaction rates |

| Solvent Systems | Toluene, 1,4-dioxane, 2-Me-THF, water cosolvents | Influence solubility, phase transfer, and halide inhibition effects | Resource through greener alternatives; Substrate scope through engineered media |

| Teicoplanin A2-3 | Teicoplanin A2-3, CAS:61036-62-2; 61036-64-4, MF:C88H97Cl2N9O33, MW:1879.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Tetromycin C1 | Tetromycin C1, MF:C50H64O14, MW:889.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The reagent solutions outlined in Table 3 provide a foundational toolkit for addressing the multifaceted constraints in Suzuki-Miyaura optimization. Recent studies have demonstrated that strategic ligand selection—particularly the use of electron-deficient monophosphines—can significantly accelerate the transmetalation step, which is often rate-determining [4]. Furthermore, the development of stabilized boron sources, such as neopentyl glycol boronates and "ethyl pinacol" esters, has dramatically improved handling and reduced side reactions for sensitive substrate classes [4].

Integrated Workflow: From Traditional Constraints to Closed-Loop Optimization

The limitations of traditional optimization become particularly evident when contrasted with emerging closed-loop approaches. The following workflow illustrates the transition from constrained manual optimization to data-driven autonomous experimentation.

The implementation of closed-loop workflows has demonstrated remarkable success in overcoming traditional constraints. Recent research shows that these systems can identify general reaction conditions for heteroaryl Suzuki-Miyaura coupling that double the average yield relative to widely used benchmark conditions developed through traditional approaches [8]. This represents a fundamental shift from hypothesis-driven to data-driven optimization, where machine learning algorithms guide experimental design to efficiently explore high-dimensional parameter spaces that would be impractical to investigate through manual approaches.

The constraints of time, resources, and substrate scope in traditional Suzuki-Miyaura reaction optimization present significant challenges for researchers in drug development and synthetic chemistry. However, through systematic analysis, strategic experimental design, and the implementation of resource-efficient protocols, these limitations can be effectively managed. The emergence of closed-loop optimization approaches represents a promising direction for overcoming these constraints entirely, enabling the discovery of more general, efficient reaction conditions through data-driven experimentation. As these advanced methodologies become more accessible, they hold the potential to dramatically accelerate reaction optimization and expand the accessible chemical space for pharmaceutical development.

The Suzuki-Miyaura (SM) cross-coupling reaction stands as a cornerstone methodology for carbon-carbon bond construction in modern organic synthesis, with profound implications for pharmaceutical development, materials science, and natural product synthesis [1] [10]. Its exceptional utility derives from the combination of mild reaction conditions, remarkable functional group tolerance, and the relatively stable, low-toxicity profile of organoboron reagents [11]. Despite its widespread adoption, achieving optimal outcomes requires careful balancing of multiple interdependent parameters within a high-dimensional chemical space [12].

Within the broader context of closed-loop optimization research, this application note provides a structured framework for understanding and manipulating three critical parameter classes: ligand electronics, base effects, and boron source selection. By systematically examining these variables and their complex interrelationships, we aim to establish a knowledge foundation that enhances the efficiency of automated optimization platforms, enabling more rapid identification of general reaction conditions for challenging substrate classes, particularly heteroaryl couplings [12] [13].

The Catalytic Cycle and Optimization Workflow

A comprehensive understanding of the Suzuki-Miyaura mechanism provides essential context for rational parameter optimization. The catalytic cycle proceeds through three fundamental steps: oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination [5] [14]. The mechanism can be visualized as follows:

Modern approaches to reaction optimization leverage automated, closed-loop workflows that systematically explore this complex parameter space. These systems integrate robotic experimentation with machine learning algorithms to minimize experimental effort while maximizing information gain [12] [8]. The workflow can be summarized as follows:

Critical Parameter 1: Ligand Electronics and Selection

Ligands play a multifaceted role in stabilizing Pd(0) species, facilitating oxidative addition, and enabling the transmetalation process. Electron density and steric bulk must be carefully balanced to achieve optimal catalytic activity [5] [13].

Ligand Electronic Properties and Catalyst Performance

The electronic character of phosphine ligands significantly influences their performance in SM couplings. Electron-rich ligands enhance oxidative addition rates for challenging substrate classes, while steric bulk promotes reductive elimination [13].

Table 1: Ligand Electronic Properties and Application Scope

| Ligand Class | Electronic Character | Steric Profile | Optimal Substrate Pairings | Typical Loading (mol%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialkylbiarylphosphines | Strongly electron-donating | Bulky | Aryl chlorides, electron-rich arenes | 0.5-2.0 |

| Trialkylphosphines | Electron-donating | Moderate to high | Heteroaryl systems, sterically hindered partners | 1.0-3.0 |

| Bidentate Phosphines | Variable | Rigid | Challenging transmetalation cases | 1.0-2.5 |

| Schiff Base Ligands | Tunable | Modular | Aryl bromides/iodides, green chemistry applications | 0.5-2.0 |

Schiff Base Ligands as Sustainable Alternatives

Schiff base ligands (formed by condensation of primary amines with carbonyl compounds) represent emerging alternatives to traditional phosphine ligands due to their air stability, ease of synthesis, and modular electronic tuning [5]. Palladium-Schiff base complexes demonstrate remarkable efficacy under mild conditions, with certain systems achieving excellent yields with aryl bromides and iodides at room temperature with minimal Pd loading [5].

Protocol 1: Evaluation of Ligand Electronic Effects on Aryl Chloride Activation

Objective: Assess the impact of ligand electron density on conversion of electron-deficient aryl chlorides.

Materials:

- Substrates: 4-chloroacetophenone (1.0 equiv), phenylboronic acid (1.3 equiv)

- Catalyst: Pd(OAc)â‚‚ (1.0 mol%)

- Ligands: P(t-Bu)₃ (electron-rich), PPh₃ (moderate), dppf (bidentate)

- Base: K₂CO₃ (2.0 equiv)

- Solvent: Toluene/water (4:1, 0.1 M total concentration)

Procedure:

- Prepare three 5 mL reaction vials each containing Pd(OAc)â‚‚ (0.01 mmol) and the respective ligand (0.02 mmol for monodentate, 0.01 mmol for bidentate)

- Add 4-chloroacetophenone (1.0 mmol), phenylboronic acid (1.3 mmol), and K₂CO₃ (2.0 mmol) to each vial

- Add solvent mixture (10 mL total) and purge with nitrogen for 5 minutes

- Heat reactions to 80°C with stirring for 12 hours

- Monitor by TLC or HPLC at 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours

- Quench with saturated NHâ‚„Cl solution, extract with ethyl acetate, and analyze

Expected Outcomes: The strongly electron-rich P(t-Bu)₃ system should demonstrate superior conversion (>80%) compared to PPh₃ (<40%) and moderate performance for dppf (50-70%), illustrating the critical role of electron-donating ligands in activating challenging aryl chlorides [5].

Critical Parameter 2: Base Effects and Transmetalation Pathways

The base plays a mechanistically complex role in SM coupling, serving both to activate the organoboron reagent and to facilitate the transmetalation step. Two competing pathways have been identified: the boronate pathway and the oxo-palladium pathway [11] [10].

Base Selection Guidelines

The optimal base depends on the specific boron reagent, substrate sensitivity, and reaction conditions. Inorganic bases are most common, though organic bases find application in specialized contexts [10] [15].

Table 2: Base Applications and Mechanistic Roles

| Base Class | Examples | Strength | Solubility Profile | Mechanistic Pathway | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonates | K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃ | Moderate | Biphasic systems | Boronate | Aryl-aryl couplings, aqueous conditions |

| Phosphates | K₃PO₄ | Strong | Biphasic systems | Boronate | Challenging transmetalations |

| Fluorides | KF, CsF | Strong | Homogeneous in organic solvents | Boronate | Anhydrous conditions, ester-protected boronates |

| Hydroxides | NaOH, KOH | Strong | Aqueous phase | Oxo-palladium | Electron-deficient boronic acids |

| Alkoxides | NaOEt, NaOt-Bu | Strong | Organic solvents | Oxo-palladium | Non-aqueous systems |

Base-Dependent Transmetalation Mechanisms

The base activates the boron reagent for transmetalation through two primary pathways. In the boronate pathway, the base first reacts with the boronic acid to form a more nucleophilic tetracoordinated boronate species, which then transfers its organic group to palladium [11] [10]. In the oxo-palladium pathway, the base first reacts with the palladium complex to form a reactive hydroxo- or alkoxo-bridged intermediate, which then interacts with the boronic acid [11]. Recent mechanistic studies, including ESI-MS and DFT calculations, generally support the boronate pathway as energetically favored for most catalytic systems [10].

Protocol 2: Investigating Base Effects on Transmetalation Efficiency

Objective: Evaluate base influence on coupling efficiency using a model heteroaromatic system.

Materials:

- Substrates: 2-bromopyridine (1.0 equiv), 3-pyridylboronic acid (1.2 equiv)

- Catalyst: Pd(PPh₃)₄ (2.0 mol%)

- Bases: K₂CO₃, K₃PO₄, KF, NaOH (2.0 equiv each)

- Solvent: Dioxane/water (5:1, 0.1 M)

Procedure:

- Prepare four 5 mL reaction vials each containing Pd(PPh₃)₄ (0.02 mmol)

- Add 2-bromopyridine (1.0 mmol) and 3-pyridylboronic acid (1.2 mmol) to each vial

- Add the respective base (2.0 mmol) to each vial

- Add solvent mixture (10 mL total) and degas with nitrogen for 5 minutes

- Heat reactions to 85°C with stirring for 8 hours

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or HPLC at 2, 4, and 8 hours

- Work up with water and extract with dichloromethane

- Analyze yields and byproduct formation

Expected Outcomes: Phosphates and carbonates typically provide optimal yields for heteroaromatic systems (60-80%), while hydroxide bases may increase protodeboronation side products. Fluoride bases may enhance conversion for boronic esters but can promote homocoupling in aqueous systems [15].

Critical Parameter 3: Boron Source Selection and Stabilization Strategies

Organoboron reagents demonstrate remarkable diversity in their reactivity profiles, stability characteristics, and preparation methods. Strategic selection of the boron source is critical for successful cross-coupling, particularly with unstable heteroaromatic systems [11].

Boron Reagent Classes and Properties

Seven main classes of boron reagents are commonly employed in SM coupling, each with distinct advantages and limitations [11].

Table 3: Boron Reagent Classes and Application Guidance

| Boron Reagent | General Stability | Nucleophilicity (Mayr Scale) | Preparation Method | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boronic Acids | Moderate to low | Reference (0) | Miyaura borylation, direct synthesis | Standard aryl-aryl couplings |

| Pinacol Esters | High | -1.1 (slightly less than boronic acid) | Miyaura borylation, esterification | Substrates prone to protodeboronation |

| Trifluoroborates | High | -3.2 (less nucleophilic) | KHFâ‚‚ treatment of boronic acids | Sequential coupling, unstable aromatics |

| MIDA Boronates | Very high | -5.2 (least nucleophilic) | Condensation with MIDA | Automated synthesis, iterative coupling |

| Alkylboranes (9-BBN) | Moderate (air-sensitive) | Not measured | Hydroboration | Alkyl-aryl couplings |

| Catechol Esters | Moderate | Not measured | Esterification, hydroboration | Original methodology |

| Trialkoxyboronate Salts | High | +4.2 (highly nucleophilic) | In situ preparation | Challenging transmetalations |

Nucleophilicity Trends and Transmetalation Efficiency

The nucleophilicity of boron reagents varies significantly across structural classes, directly impacting transmetalation rates. On the Mayr nucleophilicity scale, trialkoxyboronate salts demonstrate remarkably high nucleophilicity (comparable to ketene acetals and enamines), while MIDA boronates are significantly less nucleophilic due to electron-withdrawing carbonyl groups [11]. This nucleophilicity hierarchy provides a rational basis for reagent selection: highly nucleophilic reagents accelerate challenging transmetalations, while less nucleophilic reagents enable chemoselective transformations in multifunctional systems [11].

Protocol 3: Boron Reagent Stability Assessment and Coupling Optimization

Objective: Evaluate coupling performance of different boron reagents with a base-sensitive heteroaromatic system.

Materials:

- Substrates: 4-bromoanisole (1.0 equiv), 2-pyridylboronic acid, pinacol ester, and trifluoroborate salt (1.3 equiv each)

- Catalyst: Pd₂(dba)₃ (1.5 mol%) with SPhos (3.0 mol%)

- Base: K₂CO₃ (2.0 equiv)

- Solvent: Toluene/water (4:1, 0.1 M) or anhydrous toluene with 18-crown-6 for trifluoroborate

Procedure:

- Prepare three 5 mL reaction vials with Pd₂(dba)₃ (0.0075 mmol) and SPhos (0.03 mmol)

- Add 4-bromoanisole (1.0 mmol) to each vial

- Add the respective boron reagent (1.3 mmol) to separate vials

- For boronic acid and ester: use toluene/water solvent; for trifluoroborate: use anhydrous toluene with 18-crown-6 (0.1 mmol)

- Add K₂CO₃ (2.0 mmol) to each vial

- Degas with nitrogen and heat to 90°C for 12 hours

- Monitor protodeboronation and conversion by HPLC at 2, 6, and 12 hours

- Isolate products and compare yields

Expected Outcomes: Trifluoroborate salts typically demonstrate superior stability and reduced protodeboronation for sensitive heteroaromatics, though may require modified conditions. Pinacol esters offer intermediate stability, while boronic acids may show significant decomposition but highest reactivity when fresh [11] [15].

Integrated Case Study: Closed-Loop Optimization of Heteroaryl Coupling

Recent advances in automated reaction optimization demonstrate the power of integrated parameter screening. A landmark study applied closed-loop optimization to the challenging problem of heteroaryl SM coupling, discovering conditions that doubled the average yield compared to widely used benchmark systems [12] [8].

Experimental Design and Implementation

The closed-loop workflow employed data-guided matrix down-selection, uncertainty-minimizing machine learning, and robotic experimentation to efficiently navigate the vast parameter space [12]. This approach considered a large matrix of heteroaromatic substrates crossed with a high-dimensional matrix of reaction conditions, rendering exhaustive experimentation impractical [12].

Protocol 4: Automated Screening of Multidimensional Parameter Space

Objective: Implement a streamlined version of the closed-loop optimization workflow for a specific heteroaryl coupling pair.

Materials:

- Substrates: 2-bromothiophene (1.0 equiv), 3-pyridylboronic acid (1.1-1.5 equiv gradient)

- Catalyst library: Pd(OAc)₂, Pd₂(dba)₃, PdCl₂(dppf) (0.5-2.0 mol% gradient)

- Ligand library: P(t-Bu)₃, SPhos, XPhos, PPh₃ (1.0-4.0 mol% gradient)

- Base library: K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, K₃PO₄ (1.5-3.0 equiv gradient)

- Solvent systems: Toluene/water, dioxane/water, THF/water (3:1 to 10:1 gradients)

- Temperature range: 50-100°C

Automated Procedure:

- Employ a fractional factorial design for initial screen (16-24 experiments)

- Utilize D-optimal design to focus on promising regions of parameter space

- Implement Gaussian process regression or random forest modeling to predict yields

- Apply expected improvement or upper confidence bound acquisition functions

- Iterate through 40-60 automated experiments with real-time HPLC analysis

- Validate predicted optimum with triplicate experiments

Expected Outcomes: The closed-loop approach typically identifies optimized conditions within 60-80 experiments, substantially fewer than traditional screening methods. The resulting conditions often demonstrate non-intuitive parameter combinations that outperform literature benchmarks [12] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Suzuki-Miyaura Reaction Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pd(0) Sources | Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd₂(dba)₃ | Direct source of active catalyst | Air-sensitive, store under inert atmosphere |

| Pd(II) Precursors | Pd(OAc)â‚‚, PdClâ‚‚, Pd(TFA)â‚‚ | Stable precursors requiring in situ reduction | Bench-stable, versatile |

| Precatalyst Complexes | Buchwald precatalysts, PEPPSI complexes | Designed for facile activation | Improved reproducibility |

| Electron-Rich Ligands | P(t-Bu)₃, SPhos, XPhos | Facilitate oxidative addition of Ar-Cl | Air-sensitive, commercial solutions available |

| Bidentate Ligands | dppf, DPEPhos, BINAP | Stabilize Pd centers, control geometry | Moderate air stability |

| Schiff Base Ligands | Salen-type, custom designs | Air-stable, tunable alternatives | Easy synthesis and modification |

| Boron Activators | KF, CsF, 18-crown-6 | Enhance transmetalation from esters | Anhydrous conditions required |

| Aqueous Base | K₂CO₃, K₃PO₄ | Standard boronate activation | Biphasic reaction conditions |

| Anhydrous Base | KOt-Bu, Cs₂CO₃ | Alternative activation pathway | Moisture-sensitive |

| NQK-Q8 peptide | NQK-Q8 peptide, MF:C48H78N14O14, MW:1075.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Pluracidomycin B | Pluracidomycin B, MF:C11H13NO10S2, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The strategic optimization of ligand electronics, base effects, and boron source selection remains fundamental to advancing Suzuki-Miyaura coupling applications in complex synthetic settings. The integration of these classical parameter studies with emerging closed-loop optimization platforms represents a powerful paradigm for accelerating reaction discovery and development [12] [13].

As synthetic challenges continue to evolve toward increasingly complex molecular architectures, particularly in pharmaceutical and materials science applications, the interplay between fundamental mechanistic understanding and advanced optimization methodologies will be essential. The parameters and protocols outlined herein provide both a practical foundation for laboratory experimentation and a conceptual framework for the continued development of automated synthesis platforms.

Within the framework of closed-loop optimization for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions, understanding the rate-determining step is paramount for directing experimental resources and computational modeling. While earlier mechanistic studies often emphasized oxidative addition as the kinetic bottleneck, recent experimental and theoretical advances (2024-2025) have compellingly established transmetalation as the predominant rate-determining step across a wide spectrum of reaction conditions. This paradigm shift has profound implications for catalyst design, condition optimization, and the development of automated discovery platforms.

The transmetalation step, which involves the transfer of an organic group from boron to palladium, has long been recognized for its mechanistic complexity. Contemporary research has elucidated that its kinetics are not intrinsic but are exquisitely sensitive to a multivariate set of parameters including ligand architecture, boron coordination geometry, phase-transfer phenomena, and base identity. This review synthesizes the latest mechanistic insights, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to dissect and influence the transmetalation barrier, thereby offering a strategic compass for enhancing efficiency in closed-loop optimization campaigns.

Recent Mechanistic Insights into Transmetalation Pathways

The Dichotomy of Transmetalation Pathways

The year 2024 yielded a critical advancement in understanding how transmetalation pathways can be strategically shifted. Research published in Nature Communications demonstrated that the use of phase transfer catalysts (PTCs) under biphasic conditions induces a remarkable change in the operative mechanism [16].

- Path A - Boronate Pathway: This route involves the direct reaction of the palladium halide complex (

LnPd(Ar)(X)) with a tetracoordinate 8-B-4 arylboronate species. - Path B - Oxo-Palladium Pathway: This alternative pathway requires the preformation of a palladium hydroxide complex (

LnPd(Ar)(OH)), which then reacts with a tricoordinate 6-B-3 boronic acid.

The introduction of PTCs was found to effect a switch from the Oxo-Palladium (Path B) to the Boronate pathway (Path A), resulting in an observed 12-fold rate enhancement in model systems [16]. This shift is consequential because it directly mitigates halide inhibition—a common kinetic trap where the iodide or bromide anion competitively coordinates palladium and impedes the formation of the active LnPd(Ar)(OH) species in Path B.

Electronic and Steric Ligand Effects

The kinetic profile of transmetalation is profoundly governed by the electronic and steric properties of the phosphine ligands bound to palladium. Recent findings have sharpened the understanding that ligand tuning must balance all elementary steps, not just oxidative addition [4].

- Electron-Deficient Ligands: Monodentate, electron-deficient ligands (e.g., PPh₃) significantly accelerate the transmetalation step. This is because electron deficiency at palladium facilitates interaction with the electron-rich boron-based nucleophile [4].

- Electron-Rich and Bidentate Ligands: In contrast, strongly electron-rich (e.g., PᵢPr₃) or bidentate ligands (e.g., dppf) can create a kinetic bottleneck at transmetalation, despite their potential benefits for oxidative addition of challenging electrophiles like aryl chlorides [4].

- Ligand Geometry and Dynamics: The optimal ligand is one that provides sufficient electron density for initial oxidative addition but allows for flexibility or partial dissociation to enable a lower-energy transition state for transmetalation.

Table 1: Influence of Ligand Properties on Transmetalation Kinetics

| Ligand Type | Electronic Character | Representative Example | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monodentate | Electron-deficient | PPh₃ | Accelerates transmetalation; supports PdL1-type complexes for halide substrates [4]. |

| Monodentate | Electron-rich | PᵢPr₃ | Excellent for oxidative addition of Ar-Cl; can slow transmetalation [4]. |

| Bidentate | Neutral | dppf (PdL2) | Greatly slows transmetalation rate; can be preferred for triflate substrates [4]. |

Boron Source Reactivity and Stability

The choice of organoboron reagent represents a critical trade-off between stability and reactivity, with recent work focusing on narrowing this gap.

- The Stability-Reactivity Paradox: Historically, boronic acids are reactive but prone to protodeboronation, while esters like pinacol boronic esters are more stable but less reactive [4].

- Emerging Compromises: Recent studies highlight neopentyl glycol boronic ester as an optimal balance, demonstrating a transmetalation rate approximately 100 times faster than pinacol esters while retaining good stability [4]. Similarly, 1,1,2,2-tetraethylethylene glycol boronic esters ("ethyl pinacol") have been introduced for coupling labile substrates [4].

- Base-Dependent Behavior: The stability of boronates is highly pH-dependent. For instance, 2-pyridyl boronates exhibit exceptional stability even at high pH, whereas other boronates can undergo rapid, autocatalytic protodeboronation near the pKa of their corresponding boronic acid [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Modern Boron Sources in Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling

| Boron Source | Key Feature | Stability | Transmetalation Rate | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinacol Ester | Widely available | High | Low (Baseline) | Often requires stronger bases/heat; improved yields with labile substrates [4]. |

| Neopentyl Glycol Ester | Balanced performance | Medium | ~100x Pinacol | An effective additive or direct reagent to accelerate reactions [4]. |

| Boronic Acid | Highly reactive | Low (Protodeboronation) | High | Ideal for rapid screening but can be unsuitable for scale-up [4]. |

| Alkyl Glycal Boronate | Novel stable source | Very High | Medium (with tuning) | Enables coupling of highly unstable heteroaryl boronates [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Study

Protocol 1: Kinetic Analysis of Transmetalation Pathway Shifting

This protocol outlines the procedure for using automated reaction sampling to quantify the effect of additives like Phase Transfer Catalysts (PTCs) on transmetalation kinetics, based on the methodology from [16].

Principle: To mechanistically probe the active transmetalation pathway by measuring reaction kinetics in the presence and absence of PTCs, and to correlate rate changes with the speciation of the boron reagent.

Materials:

- Catalyst: XPhos Pd G2

- Solvents: 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF), Deionized Water

- Reagents: Benzyl bromide, 4-Methoxyphenylboronic acid pinacol ester, Potassium phosphate (K₃PO₄) base

- Additive: Tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) as PTC

- Equipment: Automated sampling platform with online HPLC [16]

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a series of reaction vessels, prepare mixtures containing the palladium catalyst (0.5 mol%), benzyl bromide (1.0 equiv), 4-methoxyphenylboronic acid pinacol ester (1.2 equiv), and K₃PO₄ (2.0 equiv) in a biphasic solvent system of MeTHF/H₂O (3:1 v/v).

- Additive Variation: To one set of reactions, add TBAB (5 mol%). Maintain an identical control set without TBAB.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Initiate the reactions with stirring to ensure biphasic mixing. Use the automated sampling platform to withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds for the first 10 minutes). The platform must quench the sample immediately and perform online HPLC analysis.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantify the concentration of the biaryl product and the remaining boronic ester over time.

- Apply Variable Time Normalization Analysis (VTNA) to determine the reaction order in the boronic ester, base, and catalyst.

- Compare the initial rates and time-to-completion between the PTC and control experiments.

Expected Outcome: The reaction with PTC will show a significant (e.g., 12-fold) increase in initial rate. VTNA will indicate a positive order in the boronic ester, supporting its involvement in the rate-determining step. The observed rate enhancement with PTC is diagnostic of a shift toward the boronate pathway (Path A) [16].

Protocol 2: Investigating Halide Inhibition and Solvent Effects

This protocol provides a method to study and overcome halide inhibition, a key phenomenon that impacts transmetalation rate.

Principle: To demonstrate that halide salts dissolved in the organic phase can inhibit the reaction, and to show that switching to a less polar solvent can mitigate this effect by reducing halide solubility [4] [16].

Materials:

- Catalyst: XPhos Pd G2

- Solvents: Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Toluene

- Reagents: Aryl halide (e.g., chlorobenzene), Arylboronic acid/ester, Base (e.g., K₂CO₃)

- Additive: Potassium iodide (KI)

Procedure:

- Baseline Reaction: Conduct a standard Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in THF/Hâ‚‚O with chlorobenzene as the electrophile. Monitor conversion over time via GC or HPLC.

- Inhibition Test: Repeat the baseline reaction, but add one equivalent of KI relative to the catalyst.

- Solvent Engineering Test: Repeat the reaction with added KI, but replace THF with toluene as the organic phase.

- Kinetic Analysis: Plot conversion versus time for all three experiments.

Expected Outcome: The addition of KI in THF will cause a dramatic reduction in reaction rate (up to 25-fold [16]). However, in toluene, the reaction with added KI will proceed at a rate much closer to the original baseline, as the halide salt has lower solubility in the less polar organic phase, thus reducing its inhibitory effect [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying and Optimizing Transmetalation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Key Application in Transmetalation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| XPhos Pd G2 | Well-defined pre-catalyst | Provides a consistent and highly active Pd(0) source; simplifies reaction setup for high-throughput experimentation [16]. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Bromide (TBAB) | Phase Transfer Catalyst (PTC) | Shifts transmetalation to the boronate pathway, accelerating rate and mitigating halide inhibition in biphasic systems [16]. |

| Potassium Trimethylsilanolate (TMSOK) | Anhydrous Base | Enhances reaction rates by improving boronate solubility in the organic phase under anhydrous conditions [4]. |

| Neopentyl Glycol Boronic Ester | Balanced Organoboron Reagent | Offers a superior compromise between stability and reactivity; used to benchmark transmetalation rates [4]. |

| 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF) | Sustainable Solvent | Used in biphasic optimization; its lower miscibility with water helps limit dissolved halide salts in the organic phase, reducing inhibition [4] [16]. |

| Glysperin B | Glysperin B, MF:C40H66N6O18, MW:919.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| JNJ-632 | JNJ-632, MF:C18H19FN2O4S, MW:378.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Closed-Loop Workflow for Transmetalation Optimization

The insights and protocols described above can be integrated into a powerful closed-loop workflow for the discovery of general reaction conditions. This approach, as demonstrated for heteroaryl Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, leverages machine learning to navigate the vast multi-dimensional space of reaction parameters [12].

The workflow initiates with a data-guided matrix down-selection to reduce the initial parameter space to a tractable set of promising conditions [12]. An uncertainty-minimizing machine learning model then guides the iterative cycle by proposing subsequent experiments that best refine its understanding of the complex relationships between reaction parameters (e.g., ligand electronics, PTC use) and the output (reaction yield), with a specific focus on overcoming the transmetalation barrier [12]. Robotic experimentation ensures reproducible and rapid execution of these experiments, which is particularly crucial for biphasic reactions where manual sampling can introduce errors [12] [16]. This closed-loop system has proven highly effective, identifying conditions that double the average yield of a widely used benchmark [12].

Implementing Closed-Loop AI and High-Throughput Experimentation

Closed-loop Artificial Intelligence (AI) optimization represents a paradigm shift in how complex processes are managed and improved. This approach creates a self-correcting system where AI models learn directly from real-time data, predict optimal parameters, and automatically implement adjustments while continuously validating outcomes against defined objectives [17]. In industrial process plants, this method captures 4–5% in EBITDA improvements that conventional linear programming models routinely miss, demonstrating its significant economic potential [17]. For chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical development, particularly in sensitive applications like Suzuki-Miyaura coupling research, this framework enables rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces that would be impractical through traditional experimentation alone [8].

The core innovation of closed-loop AI lies in its ability to handle non-linear interactions, equipment degradation, and dynamic environmental factors that challenge traditional first-principles simulators and spreadsheet optimizers [17]. By integrating machine learning with robotic experimentation, these systems can navigate high-dimensional optimization problems where multiple variables interact in complex ways, as demonstrated in heteroaryl Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling research where the method doubled average yields compared to widely used benchmark conditions [8] [18].

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

Foundational Concepts

Closed-loop AI optimization operates on several interconnected principles that distinguish it from traditional optimization approaches. The system functions as an integrated workflow where each component feeds data to subsequent stages, creating a continuous cycle of improvement.

Data-Centric Learning forms the foundation, where AI models learn directly from historical and real-time data rather than idealized assumptions [17]. This approach captures the actual behavior of complex systems, including the dynamic interactions, time-varying parameters, and non-linear relationships that govern processes like chemical reaction optimization [8]. The models ingest live data continually, refining their understanding of disturbances, feed changes, and equipment degradation [17].

Predictive Modeling utilizes machine learning, particularly deep learning and reinforcement learning, to uncover non-linear, time-varying interactions that actually govern system behavior [17]. These models identify predictive patterns—like rising energy intensity or impending off-spec quality—hours before conventional dashboards react, allowing preemptive optimization [17]. In pharmaceutical contexts, this predictive capability spans from drug discovery through manufacturing, with the FDA noting a significant increase in drug application submissions using AI components [19].

Autonomous Decision-Making enables the system to write optimal setpoints back to control systems in real-time [17]. Economic weighting directs alerts toward the highest-value constraints, allowing researchers to focus on changes that maximize desired outcomes, whether in industrial plant throughput or chemical reaction yields [17].

Continuous Validation ensures that recommendations protect safety margins while growing profits through simulated runs before implementation [17]. This principle is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical applications where regulatory compliance is paramount, with frameworks evolving at the FDA and European Medicines Agency to address AI-specific validation requirements [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Optimization Approaches

Table 1: Performance comparison between traditional and AI-driven optimization methods in process industries

| Performance Metric | Traditional Methods | Closed-Loop AI |

|---|---|---|

| EBITDA Improvement | Baseline | +4-5% vs. conventional methods [17] |

| Yield Improvement | Benchmark conditions | Double average yield (Suzuki-Miyaura case study) [8] |

| Downtime Reduction | Conventional levels | 2.1 million hours saved annually [17] |

| Energy Efficiency | Standard consumption | Significant utility cost reduction [17] |

| Problem Space Scale | Narrow regions of chemical space | Vast regions of chemical space [8] |

| Response to Variation | Steady-state assumptions | Dynamic, real-time adaptation [17] |

Application to Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling Optimization

Experimental Design and Workflow

The closed-loop optimization framework applied to heteroaryl Suzuki-Miyaura coupling exemplifies how this approach transforms chemical reaction optimization. The methodology addresses the fundamental challenge that discovering general reaction conditions requires considering vast regions of chemical space derived from a large matrix of substrates crossed with a high-dimensional matrix of reaction conditions, rendering exhaustive experimentation impractical [8].

The workflow employs data-guided matrix down-selection to reduce the experimental search space, followed by uncertainty-minimizing machine learning to identify the most informative experiments, and robotic experimentation to execute the designed reactions [8] [18]. This creates a virtuous cycle where each experiment informs the next, rapidly converging on optimal conditions while simultaneously building a comprehensive model of the reaction landscape.

The system identified conditions that double the average yield relative to a widely used benchmark that was previously developed using traditional approaches [8]. This dramatic improvement demonstrates the power of closed-loop AI to navigate complex, multidimensional optimization problems that have historically challenged conventional techniques in chemical synthesis.

Research Reagent Solutions for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for closed-loop optimization of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Heteroaryl Boronic Acids | Core reaction substrate with diverse electronic properties | Building block selection to explore chemical space [8] |

| Aryl Halide Partners | Complementary reaction substrates with varied reactivity | Matrix down-selection for general condition identification [8] |

| Palladium Catalysts | Facilitates cross-coupling with different ligand systems | High-dimensional variable in condition optimization [8] |

| Ligand Systems | Modifies catalyst activity and selectivity | Multi-dimensional parameter space exploration [8] |

| Base Additives | Affects transmetalation rate and efficiency | Critical reaction condition variable [8] |

| Solvent Systems | Medium polarity and coordination effects | Optimization of reaction environment [18] |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | Enables robotic experimentation | High-throughput reaction execution [8] |

Implementation Protocols

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocol

Step 1: Historical Data Collection Gather and cleanse historical data from historians, laboratory results, and maintenance logs, eliminating obvious gaps and reconciling tags scattered across isolated systems [17]. In chemical applications, this includes reaction yields, conversion rates, purity measurements, and byproduct formation data across different substrate combinations and reaction conditions [8].

Step 2: Real-Time Data Integration Establish streaming data connections from process sensors, online analyzers, and experimental instrumentation. Implement data validation checks to identify sensor drift, calibration lapses, or contaminated information that could poison model training [17]. Data acquisition should capture multivariate relationships across temperature, pressure, concentration, and other critical parameters.

Step 3: Feature Engineering and Selection Transform raw data into meaningful features that capture the underlying chemical and physical phenomena. This may include calculated parameters like conversion efficiency, selectivity indices, or energy consumption metrics. Apply dimensionality reduction techniques where appropriate to focus on the most informative variables [8].

Step 4: Data Normalization and Reconciliation Standardize data across different measurement scales and reconcile sampling intervals to create a consistent dataset for model training. Address missing values through appropriate imputation techniques that preserve the underlying data structure and relationships.

AI Model Training and Validation Protocol

Step 1: Model Architecture Selection Choose appropriate machine learning algorithms based on the problem characteristics. Deep learning models typically uncover non-linear, time-varying interactions that govern system behavior [17], while reinforcement learning is particularly valuable for sequential decision-making in experimental planning [8].