Data-Driven Organic Synthesis: The Convergence of AI, Robotics, and Chemistry to Revolutionize Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative field of data-driven organic synthesis, a paradigm that integrates robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to automate and accelerate chemical discovery.

Data-Driven Organic Synthesis: The Convergence of AI, Robotics, and Chemistry to Revolutionize Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative field of data-driven organic synthesis, a paradigm that integrates robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to automate and accelerate chemical discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of the foundational concepts, from the historical evolution of data-driven modeling to the core hardware and software components of modern autonomous platforms. It delves into the methodological applications, including advanced synthesis planning with tools like ASKCOS and Chematica, and the practical implementation of closed-loop optimization systems. The article further addresses critical challenges in troubleshooting, error handling, and robustness, and validates the technology's impact through comparative case studies from pharmaceutical R&D. By synthesizing key takeaways, the conclusion outlines future directions and the profound implications of these platforms for accelerating biomedical research and clinical development.

The Foundations of Autonomous Chemistry: From Linear Free Energy Relationships to AI

The journey toward data-driven organic synthesis represents a paradigm shift in chemical research, moving from empirical observation and intuition-based design to a quantitative, predictive science. This evolution finds its roots in the pioneering work of Louis Plack Hammett, who in 1937 provided the first robust mathematical framework for correlating molecular structure with chemical reactivity. The Hammett equation established a foundational linear free-energy relationship (LFER) that quantified electronic effects of substituents on reaction rates and equilibria for meta- or para-substituted benzene derivatives [1]. For decades, this equation served as the principal quantitative tool for physical organic chemists, enabling mechanistic interpretation and reaction prediction within constrained chemical spaces.

Today, the field is undergoing another transformative shift with the integration of machine learning (ML) and autonomous experimentation platforms. These technologies are extending the Hammett paradigm beyond its original limitations, enabling the prediction and optimization of chemical reactions across vast molecular landscapes. Within modern drug development and materials science, this historical evolution has culminated in the development of integrated systems capable of autonomous multi-step synthesis of novel molecular structures, where robotics and data-driven algorithms replace traditional manual operations [2]. This whitepaper traces this intellectual and technological trajectory, examining how quantitative structure-reactivity relationships have evolved from simple linear equations to complex artificial intelligence models that now drive cutting-edge chemical discovery.

The Hammett Equation: A Foundational Formalism

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Hammett equation formalizes the relationship between molecular structure and chemical reactivity through a simple yet powerful linear free-energy relationship. Its mathematical expressions for reaction equilibria and kinetics are:

For equilibrium constants: log(K/Kâ‚€) = Ïσ For rate constants: log(k/kâ‚€) = Ïσ

Where:

- K and k are the equilibrium and rate constants for the substituted benzene derivative

- Kâ‚€ and kâ‚€ are the corresponding values for the unsubstituted reference compound

- σ (sigma) is the substituent constant quantifying the electronic effect of the group

- Ï (rho) is the reaction constant indicating the sensitivity of the process to substituent effects [1]

This logarithmic form stems directly from the relationship between free energy and equilibrium/rate constants via ΔG = -RT lnK, ensuring additivity of substituent influences across similar systems. The physical interpretation rests on linear free-energy relationships, which posit that free energy changes induced by structural variations are linearly proportional across related reaction series [1].

Experimental Determination of Hammett Parameters

Traditional Methodology for Determining Substituent Constants

The experimental protocol for establishing standard σ values relies on a carefully chosen reference reaction:

- Reference System: Ionization of meta- and para-substituted benzoic acids in water at 25°C

- Measured Quantity: Acid dissociation constant (pKa) for each derivative

- Calculation: σ = log(K/K₀) = pKa(benzoic acid) - pKa(substituted benzoic acid)

- Standardization: By definition, Ï = 1 for this reference reaction [1]

This experimental design ensures consistent quantification of electronic effects across different substituents. The methodology requires precise physical organic chemistry techniques:

- Solution Preparation: Accurate preparation of substituted benzoic acid solutions in purified water

- Potentiometric Titration: Determination of acid dissociation constants using calibrated pH measurements

- Temperature Control: Maintenance at 25°C ± 0.1°C throughout measurements

- Ionic Strength Adjustment: Use of background electrolytes to maintain constant ionic strength

Experimental Determination of Reaction Constants

For new reaction series, the protocol involves:

- Measuring rate or equilibrium constants for multiple meta- and para-substituted benzene derivatives

- Plotting log(k/k₀) or log(K/K₀) against known σ values for these substituents

- Determining Ï as the slope of the resulting line via linear regression

The quality of the correlation (R² value) indicates how well the reaction adheres to Hammett behavior and whether specialized sigma parameters are needed.

Tabulated Hammett Parameters

Table 1: Selected Standard Hammett Substituent Constants

| Substituent | σ_m | σ_p |

|---|---|---|

| H | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| CH₃ | -0.069 | -0.170 |

| OCH₃ | 0.115 | -0.268 |

| OH | 0.121 | -0.370 |

| NHâ‚‚ | -0.161 | -0.660 |

| F | 0.337 | 0.062 |

| Cl | 0.373 | 0.227 |

| Br | 0.391 | 0.232 |

| I | 0.352 | 0.180 |

| COOH | 0.370 | 0.450 |

| CN | 0.560 | 0.660 |

| NOâ‚‚ | 0.710 | 0.778 |

Table 2: Representative Hammett Reaction Constants

| Reaction | Conditions | Ï Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzoic acid ionization | Water, 25°C | +1.00 | Reference reaction |

| ArCO₂Et hydrolysis | 60% acetone, 30°C | +2.44 | Large negative charge buildup |

| Anilinium ionization | Water, 25°C | +2.89 | Strong resonance demand |

| C₆H₅CH₂Cl solvolysis | 50% EtOH, 0°C | -1.69 | Positive charge development |

The Computational Transition: From Empirical Correlations to Machine Learning

Limitations of the Classical Hammett Approach

While revolutionary, the classical Hammett equation possesses significant limitations that constrained its predictive scope:

- Structural Constraints: Primarily applicable to meta- and para-substituted benzenoids; ortho-substituents introduce steric complications

- Electronic Simplification: Assumes separability of electronic effects from steric and solvation contributions

- Resonance Limitations: Standard σ values fail for systems with strong direct resonance interactions, necessitating specialized parameters (σâº, σâ»)

- Limited Chemical Space: Difficult to extend to aliphatic systems, heterocycles, or complex molecular architectures [1]

The Rise of Cheminformatics and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships

The development of cheminformatics marked a critical transition toward more comprehensive structure-reactivity models. This discipline focuses on extracting, processing, and extrapolating meaningful data from chemical structures, leveraging:

- Molecular Descriptors: Numerical representations of structural features (topological, electronic, steric)

- Chemical Similarity Methods: Comparing molecular structures to identify patterns

- Statistical Modeling: Establishing quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) beyond linear models [3]

With the rapid explosion of chemical 'big data' from high-throughput screening (HTS) and combinatorial synthesis, machine learning became an indispensable tool for processing chemical information and designing compounds with targeted properties [3].

Modern Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Hammett Constants

Recent advances have demonstrated the powerful application of machine learning to predict Hammett constants, overcoming traditional experimental limitations. A 2025 study exemplifies this approach:

Experimental Protocol: ML-Based Hammett Constant Prediction

Dataset Construction:

- Curated over 900 benzoic acid derivatives spanning meta-, para-, and symmetrically substituted variants

- Incorporated quantum chemical descriptors and Mordred-based electronic, steric, and topological descriptors

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithms tested: Extra Trees (ET) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

- Dataset partitioned into training/validation/test sets

- Hyperparameter optimization via cross-validation

- Applicability domain (AD) analysis to identify outliers and ensure model reliability

Performance Metrics:

- The ANN model achieved superior performance with test R² = 0.935 and RMSE = 0.084

- Outperformed both other ML models and previously developed graph neural networks

- Feature importance analysis revealed key descriptors: NBO charges and HOMO energies [4]

This methodology demonstrates how ML can effectively learn the underlying electronic principles captured by Hammett constants, enabling accurate prediction for novel substituents without experimental measurement.

Modern Data-Driven Organic Synthesis Platforms

Hardware Infrastructure for Autonomous Synthesis

The actualization of autonomous, data-driven organic synthesis relies on advanced hardware capabilities to overcome practical challenges in automated chemical synthesis [2]. Key components include:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Component | Function | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid handling robots | Precise reagent transfer | Robotic pipettors, syringe pumps |

| Modular reaction platforms | Performing chemical reactions | Chemputer, flow chemistry systems |

| Chemical inventory management | Storage and retrieval of building blocks | Eli Lilly's system storing 5M compounds |

| In-line analysis | Real-time reaction monitoring | LC/MS, NMR, corona aerosol detection |

| Purification modules | Automated product isolation | Catch-and-release methods, prep-HPLC |

Synthesis Planning and Retrosynthesis Algorithms

Modern autonomous platforms integrate sophisticated software for reaction planning that extends far beyond traditional retrosynthesis:

- Data-Driven Retrosynthesis: Neural models learning allowable chemical transformations from reaction databases

- Template-Based and Template-Free Approaches: Utilizing both symbolic pattern-matching rules and learned transformation patterns

- Hardware-Agnostic Protocols: Chemical description languages (e.g., XDL) for translating synthetic plans into physical operations [2]

Notable implementations include Segler et al.'s Monte Carlo tree search approach that passed a "chemical Turing test," wherein graduate-level organic chemists expressed no statistically significant preference between literature-reported routes and the program's proposals [2]. Similarly, Mikulak-Klucznik et al. demonstrated viable synthesis planning for complex natural products with their expert program, Synthia [2].

Integration with Machine Learning and Adaptive Control

The true autonomy of modern platforms emerges from their capacity for self-improvement and adaptation:

- Bayesian Optimization: Efficient empirical optimization of reaction conditions

- Closed-Loop Operation: Integration of synthesis, analysis, and planning in continuous cycles

- Failure Recovery: Detection and circumvention of failed reaction steps

- Continual Learning: Accumulation of platform-specific knowledge to improve predictions [2]

This integration enables platforms to handle mispredictions and explore new reactivity space, moving beyond merely automated execution to truly autonomous discovery.

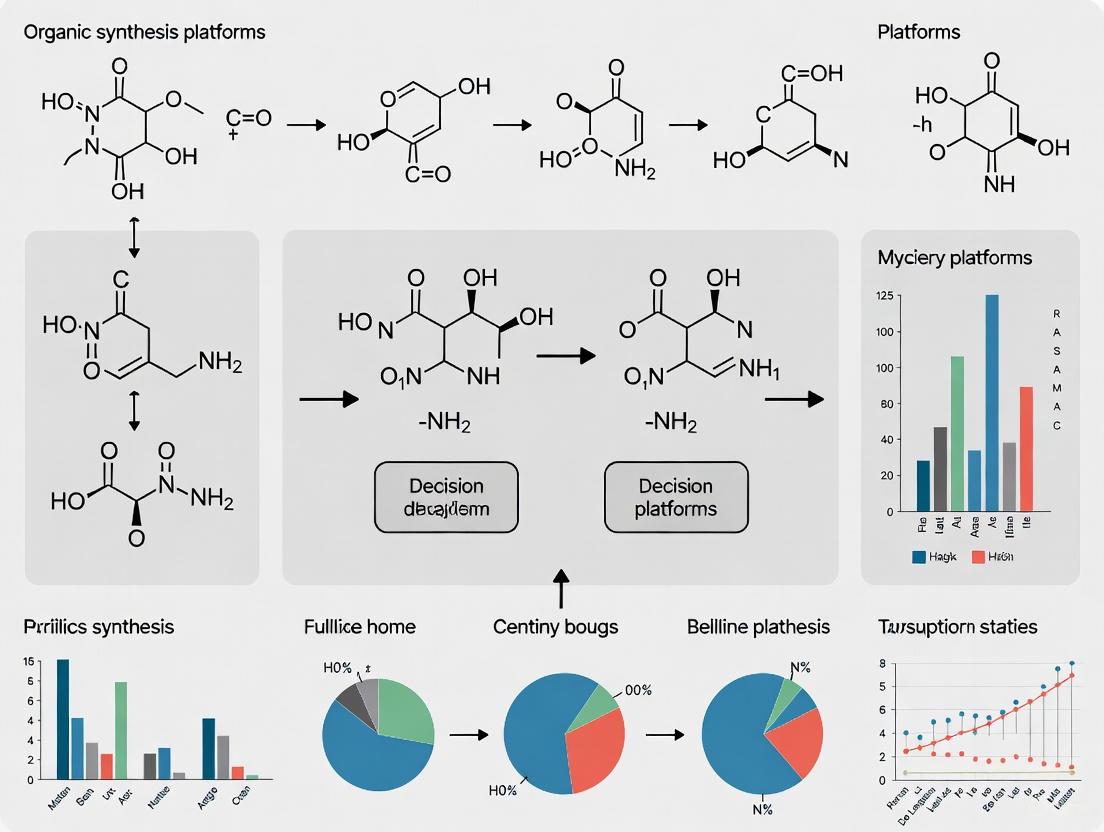

Visualizing the Workflow: From Hammett Principles to Autonomous Discovery

The Hammett Equation Concept

Modern ML-Driven Hammett Constant Prediction

Integrated Autonomous Synthesis Platform

The historical evolution from Hammett equations to modern machine learning represents more than a century of progress in quantifying and predicting chemical behavior. What began as a linear relationship for substituted benzenes has transformed into a multidimensional predictive science capable of navigating vast chemical spaces. This evolution has fundamentally reshaped organic synthesis from an artisanal practice to an information science.

In contemporary drug development and materials science, this convergence enables autonomous discovery platforms that integrate historical knowledge with adaptive learning. These systems leverage the quantitative principles established by Hammett while transcending their limitations through big data and artificial intelligence. As noted in Nature Communications, transitioning from "automation" to "autonomy" implies a certain degree of adaptiveness that is difficult to achieve with limited analytical capabilities, but represents the future of chemical synthesis [2].

The continued integration of physical organic principles with machine learning and robotics promises to further accelerate molecular discovery. This synergistic approach, honoring its quantitative heritage while embracing computational power, positions the field to address increasingly complex challenges in synthetic chemistry, drug discovery, and materials science in the data-driven era.

Autonomous platforms represent a paradigm shift in scientific research, merging advanced robotics with artificial intelligence to create self-driving laboratories. Within the context of data-driven organic synthesis, these systems close the predict-make-measure-analysis loop, dramatically accelerating the discovery and optimization of new molecules and materials [5]. This guide details the three core components—hardware, software, and data—that constitute a functional autonomous platform for modern scientific research.

Hardware: The Physical Layer of Automation

The hardware component encompasses the robotic systems and instrumentation that perform physical experimental tasks. These systems automate the synthesis, handling, and characterization of materials, enabling high-throughput and reproducible experimentation.

Robotic Platforms and Synthesis Modules

Automated robotic platforms form the operational core of the autonomous laboratory. Key hardware modules include [6]:

- Liquid Handling Robotic Arms: Z-axis arms equipped with pipettes for precise liquid transfer, addition, and serial dilution.

- Agitation and Reaction Stations: Modules with multiple reaction sites for vortex mixing and temperature control to conduct chemical reactions.

- Purification and Processing Modules: Centrifuges for solid-liquid separation and fast wash modules for cleaning tools.

- Inline Characterization Tools: Integrated analytical instruments, such as UV-Vis spectroscopy modules, for immediate property measurement of synthesized materials.

These modules are often designed to be lightweight and detachable, providing flexibility to reconfigure the platform for different experimental workflows [6].

Implementation and Cost Considerations

Autonomous platforms can be developed following several approaches, each with distinct advantages and resource requirements. The following table summarizes three common strategies based on real-world implementations for energy material discovery [7]:

| Implementation Approach | Description | Relative Cost | Development Time | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turn-Key System | A fully integrated, commercially available robotic platform ready for use upon delivery. | ~€160,000 | Several years | Integrated system; reduced initial development burden. |

| Do-It-Yourself (DIY) | A custom-built platform using open-source components and in-house mechanical design. | ~€4,000 | Rapid development | Very low cost; highly customizable; fosters deep technical knowledge. |

| Hybrid System | Combines a ready-to-use core robot (e.g., pipetting robot) with custom-built tools and cells. | ~€17,000 | As low as two weeks | Fast deployment; ideal for cross-laboratory collaboration; balanced cost. |

Software: The Intelligence and Orchestration Layer

The software component provides the decision-making brain of the autonomous platform. It integrates AI models for planning, optimization, and data analysis, orchestrating the hardware to perform closed-loop experimentation.

AI Decision-Making and Optimization Algorithms

AI algorithms are critical for efficiently navigating complex, multi-parameter experimental spaces. These algorithms decide which experiment to perform next based on previous outcomes.

- Heuristic Search Algorithms: The A* algorithm, a heuristic search method, has demonstrated high efficiency in optimizing nanomaterial synthesis parameters (e.g., for Au nanorods and nanospheres) within a discrete parameter space, requiring significantly fewer iterations than other methods [6].

- Bayesian Optimization: This probabilistic model-based approach is widely used to minimize the number of experiments needed to find optimal conditions, particularly for black-box optimization problems in catalysis and material synthesis [5] [7].

- Genetic Algorithms (GAs): GAs are effective for handling large numbers of variables and have been successfully applied to optimize the crystallinity and phase purity of complex materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [5].

- Large Language Models (LLMs) for Literature Mining: GPT and other LLMs can be integrated to extract synthesis methods and parameters from vast scientific literature, converting unstructured text into executable experimental procedures [6].

The workflow below illustrates how these components integrate to form a closed-loop, autonomous discovery cycle, from knowledge extraction to experimental execution and AI-driven analysis.

AI Agent Frameworks for Orchestration

The coordination of complex, multi-step workflows can be managed by specialized AI agent frameworks. These platforms provide the infrastructure for building, deploying, and monitoring autonomous AI agents that can execute tasks. The following table summarizes key frameworks relevant for research environments [8]:

| Framework | Type | Primary Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AutoGen | Open-Source | Ideal for orchestrating multi-agent collaboration, where specialized agents (e.g., for planning, analysis) communicate and reflect. |

| CrewAI | Open-Source/Platform | Useful for designing role-based teams of agents (e.g., "Synthesis Planner", "Data Analyst") that collaborate on a problem. |

| LangChain | Open-Source | Provides modular components for building complex, custom multi-model AI applications with flexible retrieval and memory. |

Data: The Foundational Layer

Data serves as the fuel for AI-driven discovery. A robust data infrastructure ensures the generation, management, and utilization of high-quality, standardized data.

Chemical Science Databases and Knowledge Graphs

The chemical science database is a cornerstone, managing and organizing diverse, multimodal data for AI-powered prediction and optimization [5].

- Data Sources: These include structured data from proprietary (e.g., Reaxys, SciFinder) and open-access databases (e.g., PubChem, ChEMBL), as well as unstructured data extracted from scientific literature and patents using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and named entity recognition (NER) toolkits like ChemDataExtractor [5].

- Knowledge Representation: Processed data can be organized into Knowledge Graphs (KGs), which provide a structured representation of entities (e.g., molecules, reactions) and their relationships, enhancing AI's reasoning capabilities. Frameworks like SAC-KG leverage LLMs for efficient domain KG construction [5].

The Role of High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

HTE is a critical methodology for generating the high-quality, standardized data required to train robust AI models.

- Function: HTE involves conducting miniaturized reactions in parallel, which allows for the rapid exploration of a vast chemical space (e.g., varying solvents, catalysts, reagents, temperatures) and provides comprehensive datasets that include both positive and negative results [9].

- Data for Machine Learning: The robust and reproducible data generated by HTE is particularly valuable for training and validating machine learning algorithms, moving beyond serendipity to a systematic understanding of reaction landscapes [9].

Experimental Protocols in Autonomous Workflows

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization of Nanomaterials

This detailed methodology is derived from an autonomous platform that employed the A* algorithm to optimize Au nanorod synthesis [6].

- Literature Mining & Initial Script Setup:

- A GPT model, trained on hundreds of academic papers, is queried to retrieve established synthesis methods and initial parameters for seed-mediated growth of Au nanorods.

- Based on the generated experimental steps, an automated operation script (mth or pzm file) is edited or called to control the robotic hardware.

Automated Synthesis Execution:

- The robotic platform automatically dispenses precise volumes of precursor solutions (Chloroauric acid, AgNO₃, ascorbic acid, and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide surfactant) using its Z-axis arms.

- Reaction vials are transferred to agitator modules for controlled mixing and reaction.

Inline Characterization:

- The synthesized nanoparticle dispersion is automatically transferred to an integrated UV-Vis spectrometer.

- The Longitudinal Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) peak position and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) are measured and recorded.

AI Decision & Parameter Update:

- The synthesis parameters and corresponding UV-Vis data are uploaded to a specified location.

- The A* algorithm processes this data to determine the most promising set of parameters to test next, aiming to reach the target LSPR range (e.g., 600-900 nm).

- Steps 2-4 are repeated in a closed loop until the target criteria are met. The platform conducted 735 such experiments to comprehensively optimize multi-target Au NRs [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the aforementioned autonomous nanomaterial synthesis experiment, along with their functions [6].

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuClâ‚„) | Gold precursor salt for the formation of Au nanospheres and nanorods. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Additive to control the aspect ratio and growth of Au nanorods. |

| Ascorbic Acid | Reducing agent that converts Au³⺠ions to Au⺠for subsequent reduction on seed particles. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Surfactant that forms a bilayer structure, directing the anisotropic growth of nanorods. |

| Au Nanosphere Seeds | Small spherical gold nanoparticles that act as nucleation sites for the growth of nanorods. |

| RS 8359 | RS 8359, CAS:119670-32-5, MF:C14H12N4O, MW:252.27 g/mol |

| Aeroplysinin | Aeroplysinin, CAS:55057-73-3, MF:C9H9Br2NO3, MW:338.98 g/mol |

Quantitative Performance of Autonomous Systems

The efficacy of autonomous platforms is demonstrated by concrete performance metrics from deployed systems. The table below summarizes quantitative results from two distinct autonomous platforms for materials discovery [6] [7].

| Platform / Study | Key Performance Metric | Result / Output |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Synthesis Platform [6] | Optimization iterations for Au NRs (LSPR 600-900 nm) | 735 experiments |

| Optimization iterations for Au NSs / Ag NCs | 50 experiments | |

| Reproducibility (LSPR peak deviation) | ≤ 1.1 nm | |

| Reproducibility (FWHM deviation) | ≤ 2.9 nm | |

| FastCat SDL for Catalysts [7] | Compositions tested (Ni, Fe, Cr, Co, Mn, Zn, Cu, Al LDH) | > 1000 compositions |

| Cycle time per sample (synthesis & measurement) | 52 minutes | |

| Best overpotential (at 20mAcmâ»Â²) | 231 mV (NiFeCrCo) |

The logical flow of the A* algorithm's decision-making process within the optimization module is detailed below. This process enables the efficient navigation from initial parameters to an optimal synthesis recipe.

In the pursuit of accelerating scientific discovery, particularly in data-driven organic synthesis, the distinction between automation and autonomy represents a fundamental paradigm shift. While both concepts aim to enhance efficiency and productivity, they differ profoundly in their operational approach and cognitive capabilities. Automation refers to systems that execute pre-programmed, repetitive tasks with high precision but limited adaptability, functioning effectively in stable, predictable environments such as assembly line robots or automated data processing systems [10]. In contrast, autonomy describes systems capable of performing tasks independently by making decisions based on their environment and internal programming. Autonomous systems can adapt to new situations, learn from experiences, and handle unpredictable variables without direct human control [10].

The transition from automation to autonomy is critically enabled by adaptive learning, where systems leverage artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) to continuously improve their performance based on data acquisition and feedback [11]. In the context of organic synthesis platforms, this evolution is transforming how researchers design, execute, and analyze chemical reactions, moving from merely mechanizing manual tasks toward creating self-optimizing systems that can navigate complex scientific challenges with minimal human intervention. This technical guide explores the role of adaptive learning in bridging the gap between automated and autonomous systems, with specific application to data-driven organic synthesis platforms for drug development professionals and research scientists.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Fundamental Distinctions

The transition from automated to autonomous systems represents a fundamental shift in human-machine interaction, particularly in scientific domains like organic synthesis. Automation creates systems that follow predetermined instructions with exceptional precision but minimal deviation tolerance. In laboratory settings, this encompasses liquid handling robots, computer-controlled heater/shaker blocks, and automated purification systems that perform repetitive, high-precision tasks [2] [10]. These systems require human oversight to monitor operations and address any malfunctions or deviations from expected parameters.

Autonomy, however, introduces systems capable of independent decision-making based on sensory input and learning algorithms. Autonomous systems can perceive their environment, process information, and take action without direct human control, adapting their behavior in response to changing conditions or unexpected obstacles [10]. In chemical synthesis, this might include platforms that can design synthetic routes, execute multi-step reactions, analyze outcomes, and revise strategies based on results—all with minimal human intervention [2].

The Critical Role of Adaptive Learning

Adaptive learning serves as the crucial bridge between static automation and dynamic autonomy. This capability enables systems to modify their behavior and improve performance over time through data-driven experience rather than explicit reprogramming. Adaptive learning systems employ various AI/ML techniques to gather and interpret data, detect patterns, identify areas of strength and weakness, and generate personalized recommendations and interventions [12].

In scientific contexts, adaptive learning empowers platforms to cope with mispredictions and determine suitable action sequences through trial and error. This functionality is particularly valuable in reaction optimization, where systems can modulate reaction conditions to improve yields or selectivities through empirical approaches like Bayesian optimization [2]. The "closed loop" architecture fundamental to all adaptive learning systems collects data from the operational environment, uses it to evaluate progress, suggests subsequent actions, and delivers customized feedback in a continuous cycle of improvement [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of System Capabilities

| Feature | Automation | Autonomy |

|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making | Follows predetermined rules | Makes independent decisions based on environment |

| Adaptability | Limited to predefined scenarios | High; handles unpredictable variables |

| Learning Capability | None without reprogramming | Continuous improvement through adaptive learning |

| Human Intervention | Requires monitoring and oversight | Limited to maintenance and complex exceptions |

| Data Utilization | Executes fixed protocols | Uses data to inform decisions and optimize processes |

| Error Handling | Stops or requires human intervention | Adapts and recovers from unexpected situations |

Technical Implementation in Organic Synthesis

Hardware Infrastructure for Autonomous Chemistry

The physical realization of autonomous organic synthesis platforms requires sophisticated hardware infrastructure that extends beyond conventional laboratory automation. The foundational layer consists of modular robotic systems that perform common physical operations: transferring precise amounts of starting materials to reaction vessels, heating or cooling while mixing, purifying and isolating desired products, and analyzing outcomes [2]. These operations are enabled by commercial components including liquid handling robots, robotic grippers for plate or vial transfer, computer-controlled heater/shaker blocks, and autosamplers for analytical instrumentation.

Reaction execution occurs primarily in either flow or batch systems, each with distinct advantages for autonomous operation. Flow chemistry platforms utilize computer-controlled pumps and reconfigurable flowpaths, enabling continuous processing with integrated purification capabilities [2]. Batch systems, exemplified by the Chemputer or platforms using microwave vials as reaction vessels, automate traditional flask-based chemistry through programmed transfer operations [2]. Critical engineering considerations include minimizing evaporative losses, performing air-sensitive chemistries, and maintaining precise temperature control—all addressable through specialized engineering solutions.

Post-reaction analysis typically employs liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) for product identification and quantitation. For multi-step syntheses, autonomous platforms must also address the challenge of intermediate isolation and resuspension between reactions, requiring automated solution transfer between reaction areas and purification units [2]. A universally applicable purification strategy remains elusive, though specialized approaches like iterative MIDA-boronate coupling platforms demonstrate how constraining reaction space can enable effective "catch and release" purification methods [2].

Synthesis Planning and Decision Algorithms

Beyond physical execution, autonomous synthesis requires sophisticated planning capabilities that transcend traditional retrosynthesis. Computer-aided synthesis planning has evolved from rule-based systems to data-driven approaches using neural models trained on reaction databases. These include both template-based and template-free approaches, with demonstrations such as Segler et al.'s Monte Carlo tree search method that proposed routes indistinguishable from literature approaches by graduate-level organic chemists [2].

However, retrosynthesis represents merely the initial step in autonomous organic synthesis. Experimental execution requires specification of quantitative reaction conditions—precise amounts of reactants, solvents, temperatures, times—and translation into detailed action sequences for hardware execution [2]. These procedural subtleties are often missing from current databases and data-driven tools, creating a significant gap between theoretical planning and practical implementation.

Emerging platforms address this challenge through hybrid planning approaches that combine organic and enzymatic strategies with AI-driven decision-making. For example, ChemEnzyRetroPlanner employs a RetroRollout* search algorithm that outperforms existing tools in planning synthesis routes for organic compounds and natural products [13]. Such platforms integrate multiple computational modules, including hybrid retrosynthesis planning, reaction condition prediction, plausibility evaluation, enzymatic reaction identification, enzyme recommendation, and in silico validation of enzyme active sites [13].

Experimental Protocols for Adaptive Learning Implementation

The implementation of adaptive learning in organic synthesis follows a structured experimental protocol centered on continuous optimization:

Initial Condition Prediction: Deploy neural networks trained on historical reaction data to propose initial reaction conditions as starting points for optimization. These models leverage databases such as the Open Reaction Database to identify patterns and correlations between molecular structures and optimal conditions [2].

Bayesian Optimization Loop: Execute successive experimental iterations using a Bayesian optimization framework that models the reaction landscape and strategically selects subsequent conditions to maximize desired outcomes (yield, selectivity, etc.). Each iteration narrows the parameter space toward optimal conditions [2].

Real-Time Analytical Integration: Incorporate inline analytical monitoring (e.g., LC/MS, NMR) to provide immediate feedback on reaction outcomes. This enables rapid assessment of success or failure without manual intervention [2].

Failure Recovery Protocols: Implement contingency procedures for when reactions fail to produce desired products. For flow platforms, this includes mechanisms to detect and recover from clogging events; for vial-based systems, protocols to discard failed reactions and initiate alternative routes [2].

Knowledge Database Updates: Systematically incorporate successful and failed reaction data into continuously updated knowledge bases, enabling progressively improved initial predictions over time through transfer learning approaches [2].

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Autonomous Synthesis Platforms

| Technique | Primary Function | Throughput | Quantitation Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) | Product identification and reaction monitoring | High | Limited without standards |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Structural elucidation | Low | Excellent with calibration |

| Corona Aerosol Detection (CAD) | Universal detection for quantitation | Medium | Excellent (universal calibration) |

| Inline IR Spectroscopy | Real-time reaction monitoring | High | Requires model development |

Visualization of System Architectures

Autonomous Synthesis Platform Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of an autonomous organic synthesis platform, highlighting the continuous feedback loops enabled by adaptive learning:

Adaptive Learning Cycle

The core adaptive learning process that enables autonomy is detailed in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Organic Synthesis

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MIDA-boronates | Catch-and-release purification | Iterative cross-coupling platforms [2] |

| Chemical Description Language (XDL) | Hardware-agnostic protocol definition | Standardizing execution across platforms [2] |

| Open Reaction Database | Community-curated reaction data | Training data for prediction algorithms [2] |

| ChemEnzyRetroPlanner | Hybrid organic-enzymatic synthesis planning | Sustainable route design [13] |

| RetroRollout* Algorithm | Neural-guided A* search | Retrosynthesis pathway optimization [13] |

| AI Center (UiPath) | Adaptive learning implementation | Continuous process improvement [11] |

| Bayesian Optimization | Reaction condition optimization | Efficient parameter space exploration [2] |

| Alliin | Alliin (S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide) | High-purity Alliin, the key biosynthetic precursor to allicin in garlic. Explore its role in antimicrobial and cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Cefprozil | (Z)-Cefprozil |

The integration of adaptive learning represents the critical differentiator between merely automated systems and truly autonomous platforms for organic synthesis. While current technologies have demonstrated compelling proof-of-concept applications—from mobile robot chemists to automated multi-step synthesis platforms—achieving full autonomy requires overcoming significant challenges in data quality, model precision, and system integration [2] [14]. The foremost hurdles include developing universally applicable purification strategies, creating algorithms that match the precision required for experimental execution, and establishing robust frameworks for continuous learning from platform-generated data.

The future trajectory of autonomous synthesis platforms points toward tighter integration with molecular design algorithms for function-oriented synthesis, where the ability to achieve target molecular functions may ultimately prove more valuable than achieving specific structural targets [2]. As these platforms evolve, the scientific community must concurrently address nascent concerns regarding data standardization, reproducibility, and appropriate governance frameworks [15]. Through continued advancement in both hardware capabilities and adaptive learning algorithms, autonomous synthesis platforms hold exceptional promise for transforming discovery workflows in pharmaceutical development and beyond, ultimately accelerating the delivery of novel therapeutic agents to patients.

The Critical Role of Data Curation and Open-Access Databases

In the field of data-driven organic synthesis, the acceleration of research and discovery is intrinsically linked to the quality and accessibility of chemical data. Cheminformatics, which combines artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and data analytics, is transforming organic chemistry from a trial-and-error discipline into a predictive science [16]. This transformation depends on two foundational pillars: robust data curation, which ensures data is accurate, consistent, and reusable, and open-access databases, which provide the large-scale, high-quality data necessary to fuel advanced computational models [17] [18].

The broader thesis of modern research platforms is that data-driven approaches can dramatically accelerate molecular design and synthesis. As of 2025, organic chemistry thrives in the digital space, where cheminformatics tools predict reaction outcomes, optimize retrosynthetic pathways, and enable the design of novel compounds [16]. However, the effectiveness of these AI-driven tools is contingent on the data they are trained on. Data curation is the critical process that transforms raw, unstructured experimental data into a reliable asset, making it findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) [19]. When coupled with open-access data, curated datasets empower researchers to make informed decisions, reduce experimental redundancies, and advance innovation in drug discovery and materials science [16] [20]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the methodologies and resources that underpin this scientific evolution.

Data Curation: Concepts and Process

Defining Data Curation

Data curation is the comprehensive process of maintaining accurate, consistent, and trustworthy datasets. It extends beyond simple data cleaning to include the addition of context, metadata, and governance, creating long-term value and trust in data-driven decisions [18]. In scientific research, a data curator reviews a dataset and its associated documentation to enhance its findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR principles) [19]. The goal is to ensure that research data publication is FAIR and that the data will remain useful for generations to come [17].

This process is a continuous task, requiring datasets to be reviewed regularly to ensure their ongoing accuracy, completeness, and accessibility [18]. For machine learning applications, particularly in fields like computer vision and cheminformatics, data curation refines raw inputs into usable datasets by removing duplicates, fixing labels, and balancing classes. This is crucial for tasks where label accuracy directly impacts model performance, such as in molecular property prediction [18].

The Data Curation Workflow

The data curation process involves a series of methodical steps, each building upon the previous to strengthen data quality, integrity, and potential for reuse. The following workflow outlines the key stages, with specific protocols for the types of data common in organic synthesis and cheminformatics.

Table 1: Key Steps in the Data Curation Workflow

| Step | Core Activities | Technical Protocols for Organic Synthesis Data |

|---|---|---|

| Data Identification & Collection | Determine data needs and acquisition sources. Standardize formats early. | Identify relevant data from patents, academic papers, and reaction databases [16]. Standardize file formats (e.g., SDF, SMILES) and image resolutions. |

| Data Cleaning | Remove errors, duplicates, and inconsistencies. Validate and normalize data. | Use tools like RDKit [16] to standardize chemical structures and validate SMILES strings. Correct errors in reaction logs and handle missing values in yield data. |

| Data Annotation | Label and tag raw data to provide structure. | Apply precise labels for bounding boxes in spectral images or named entity recognition in scientific text using NLP tools like ChemNLP [16]. |

| Data Transformation & Integration | Convert data into consistent formats and merge multiple sources. | Normalize pixel values in PXRD patterns [20]. Unify annotation schemas (e.g., converting between COCO, YOLO formats) using tools like Labelformat [18]. |

| Metadata Creation & Documentation | Provide essential context and documentation for interpretation and reuse. | Document synthesis conditions, catalyst used, and solvent for a reaction [17]. Use standards like JSON or CVAT XML for records [18]. Include a data dictionary. |

| Data Storage, Publication & Sharing | Store data in accessible, secure systems with clear access rules. | Publish in FAIR-compliant repositories. Use open, non-proprietary file formats (e.g., CSV over Excel, LAS/LAZ for point clouds) to ensure long-term usability [17]. |

| Ongoing Maintenance | Regularly update, validate, and re-annotate datasets to prevent model drift. | Add new reaction types or conditions. Regularly validate dataset against new research findings to maintain accuracy and relevance [18]. |

Data Curation in Practice: Experimental Protocols and AI-Ready Data

A Detailed Experimental Protocol for Curating a Chemical Reaction Dataset

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for curating a dataset of organic reactions, such as those from digitized patents or automated synthesis robots, to make it suitable for training machine learning models.

- Objective: To transform a raw collection of chemical reaction records into a clean, annotated, and well-documented dataset for predicting reaction yields.

- Raw Data Source: A collection of reactions exported in a structured format (e.g., SD files) from a source like US patents [13] or an internal electronic lab notebook (ELN) system.

- Equipment & Software: RDKit Cheminformatics Toolkit, Python scripting environment, a data annotation tool (e.g., CVAT), and a repository for storage (e.g., institutional FAIR repository).

Procedure:

- Data Extraction and Validation: Load the raw SD files. Use RDKit to parse each record and validate the chemical structures of reactants, reagents, and products. Discard records where structures cannot be parsed or are deemed invalid by the toolkit's sanitization process [16].

- Data Cleaning:

- Duplicate Removal: Calculate molecular hashes (InChIKey) for all reaction products. Identify and remove duplicate reactions based on an exact hash match.

- Handling Missing Values: For reactions with missing yield data, flag them for potential imputation later or exclude them from yield prediction tasks. For categorical data (e.g., solvent), a "Not Reported" category may be created.

- Standardization: Standardize reaction components using RDKit. This includes neutralizing charges, removing solvents and salts according to predefined rules, and generating canonical SMILES strings for all molecules to ensure consistency [16].

- Data Annotation and Feature Engineering:

- Automatic Annotation: Use RDKit to compute molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, number of aromatic rings) for each reactant and product.

- Reaction Center Identification: Employ an unsupervised learning model to identify the reaction center, which is critical for understanding the transformation [13].

- Condition-Based Contrastive Learning: To enhance yield prediction, apply a contrastive learning technique that groups reactions with similar conditions (temperature, catalyst, solvent) together in the embedding space [13].

- Metadata Creation and Documentation:

- Create a comprehensive data dictionary that defines every field in the final dataset (e.g.,

SMILES_reactant,SMILES_product,yield,temperature_C,solvent). - In a README file, document the provenance of the original data, all cleaning and standardization steps applied, the version of RDKit used, and any known limitations or biases in the data [17].

- Create a comprehensive data dictionary that defines every field in the final dataset (e.g.,

- Storage and Publication:

- Store the final curated dataset in a repository such as DesignSafe-CI or Zenodo, ensuring it is accompanied by the README and data dictionary [17].

- Prefer non-proprietary formats: store tabular data as CSV files and chemical structures as SDF or SMILES strings in a text file.

Achieving AI-Ready Curation Quality

For datasets intended to train or benchmark AI models, curation requirements are more stringent. "AI-Ready" data must be clean, well-structured, unbiased, and include necessary contextual information to support AI workflows effectively [17]. Best practices include:

- Referencing Public Models: If the data is used to train a model, the public model used should be referenced in the dataset's metadata [17].

- Documenting Model Performance: The data report should document the performance results of the model trained on the published dataset. If results are in a paper, the paper should be referenced [17].

- Network of Resources: AI-ready data should showcase a network of resources that includes the data, the model, and the performance of the model, creating a complete package for reuse and validation [17].

The effectiveness of data-driven platforms relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for scientists working in this domain.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for Data-Driven Organic Synthesis

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Toolkit | Open-source cheminformatics providing core functions like molecular visualization, descriptor calculation, and chemical structure standardization for data consistency [16]. |

| IBM RXN | Web Platform | Uses AI to predict reaction outcomes and perform retrosynthetic analysis, modeling synthesis routes to boost research efficiency [16]. |

| AiZynthFinder | Software | Open-source tool for retrosynthetic planning that integrates extensive reaction databases to automate the design of optimal synthetic pathways [16] [13]. |

| ChemEnzyRetroPlanner | Web Platform | Open-source hybrid synthesis planning platform that combines organic and enzymatic strategies using AI-driven decision-making [13]. |

| Reaxys | Commercial Database | A curated database of chemical substances, reactions, and properties, used for data mining and validation of synthetic pathways [13]. |

| US Patent Data | Open Data Source | A large-scale dataset of chemical reactions extracted from US patents (1976-2016), serving as a primary source for training reaction prediction models [13]. |

| SMILES | Data Format | A line notation system (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) for representing chemical structures as text, enabling easy storage and processing by ML models [20]. |

| PXRDPattern | Data Type | Powder X-ray Diffraction pattern, represented as a 1D spectrum, used as input for multimodal ML models to predict material properties [20]. |

The Indispensable Role of Open-Access Databases

Open-access databases are the fuel for the AI engines in modern chemistry. They provide the vast, diverse datasets necessary to train robust machine learning models that can generalize beyond narrow experimental conditions.

The value of these databases is demonstrated in studies like the one on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Researchers created a multimodal model that used only data available immediately after synthesis—PXRD patterns and chemical precursors (as SMILES strings)—to predict a wide range of MOF properties [20]. This model was pretrained in a self-supervised manner on large, open MOF databases, which allowed it to achieve high accuracy even on small labeled datasets, connecting new materials to potential applications faster than ever before [20].

This approach is directly applicable to organic synthesis. Tools like AiZynthFinder are built on extensive reaction databases and have seen years of successful industrial application, demonstrating the practical power of open data [13]. The push for open data is also institutional, with funding agencies and journals increasingly requiring data deposition in public repositories, making curation skills essential for modern researchers [16] [19].

Visualizing Workflows and Data Relationships

The Data Curation Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the data curation process, from raw data to a reusable, AI-ready asset.

Data Curation Pipeline

Connecting Synthesis to Application via Multimodal ML

This diagram outlines the synthesis-to-application workflow for materials, demonstrating how curated data powers AI-driven property prediction and application recommendation.

Synthesis-to-Application ML Workflow

The integration of meticulous data curation and open-access databases is the cornerstone of the ongoing revolution in data-driven organic synthesis. As the field advances, the ability to generate, curate, and leverage high-quality chemical data will be a key differentiator for research groups and organizations. The methodologies and tools outlined in this whitepaper—from the rigorous CURATE(D) workflow and AI-ready standards to the powerful combination of cheminformatics tools and open data—provide a roadmap for researchers to navigate this new landscape. By adopting these practices, scientists and drug development professionals can enhance the speed, efficiency, and impact of their research, ensuring they remain at the forefront of innovation in 2025 and beyond.

AI and Robotics in Action: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) has emerged as a transformative technology in organic chemistry, enabling researchers to navigate the complex retrosynthetic landscape of target molecules through computational power. CASP systems are broadly categorized into two methodological paradigms: rule-based approaches, which rely on curated knowledge of chemical transformations, and data-driven approaches, which leverage statistical patterns learned from large reaction databases [16]. The evolution from primarily rule-based systems to increasingly data-driven, artificial intelligence (AI)-powered platforms represents a significant shift in the field, accelerating research in drug discovery and materials science [16] [13]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of both paradigms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding modern CASP technologies within the broader context of data-driven organic synthesis platform research.

Rule-Based Retrosynthesis: Knowledge-Driven Approaches

Core Principles and Historical Context

Rule-based CASP systems operate on a foundation of explicitly encoded chemical knowledge, representing one of the earliest approaches to computational retrosynthesis. These systems utilize hand-crafted transformation rules derived from established chemical principles and expert knowledge. Each rule defines a specific chemical reaction type, including the required structural context, stereochemical constraints, and compatibility conditions for functional groups.

The development of rule-based systems dates back to pioneering work in the late 20th century, with foundational systems like LHASA (Logic and Heuristics Applied to Synthetic Analysis) establishing the core principles of the methodology [13]. These systems implement a goal-directed search strategy that recursively applies retrosynthetic transformations to decompose target molecules into simpler, commercially available starting materials. The strategic application of these rules is often guided by chemical heuristics that prioritize disconnections based on strategic value, functional group manipulation, and molecular complexity reduction.

Implementation Architecture

The architecture of a rule-based CASP system typically comprises three interconnected components: a knowledge base of transform rules, a reasoning engine for rule application, and a scoring mechanism for route evaluation.

Knowledge Representation: Transformation rules are formally represented as graph rewriting operations where subgraph patterns define reaction centers and associated molecular contexts. For example, a Diels-Alder transformation rule would encode the diene and dienophile patterns with appropriate stereochemical and electronic constraints.

Search Algorithm: The retrosynthetic search employs a tree expansion algorithm where nodes represent molecules and edges represent the application of retrosynthetic transforms. The search space is navigated using heuristic evaluation functions that estimate synthetic accessibility or proximity to available starting materials.

Strategic Control: Expert systems often incorporate meta-rules that govern the selection and application of transforms based on chemical strategy, such as prioritizing ring-forming reactions, addressing stereochemical challenges early, or implementing protective group strategies.

Table 1: Key Rule-Based CASP Systems and Their Characteristics

| System Name | Knowledge Representation | Search Methodology | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LHASA [13] | Reaction transforms with applicability conditions | Depth-first search with heuristic pruning | Complex natural product synthesis |

| Chematica [16] | Manually curated reaction network | Algorithmic pathfinding with cost optimization | Pharmaceutical route scouting |

| SYNCHEM | Reaction rules with thermodynamic data | Breadth-first search with synthetic cost evaluation | Biochemical pathway design |

Data-Driven Retrosynthesis: The Machine Learning Paradigm

Fundamental Concepts and Advances

Data-driven retrosynthesis represents a paradigm shift from knowledge-based to pattern-based synthesis planning, leveraging statistical regularities discovered in large reaction datasets. Rather than relying on pre-defined chemical rules, these systems learn the patterns of chemical transformations directly from experimental data, enabling the discovery of novel disconnections and routes that might not be captured by traditional rule sets [21].

The emergence of data-driven approaches has been enabled by three key developments: (1) the digitization of chemical knowledge through large-scale reaction databases containing millions of examples, (2) advances in machine learning (ML) algorithms capable of processing complex molecular representations, and (3) increased computational power for training and inference [16]. Modern data-driven CASP systems increasingly employ deep learning architectures, including sequence-to-sequence models, graph neural networks, and transformer-based approaches pretrained on chemical corpora.

Methodological Framework

Data-driven retrosynthesis employs a diverse methodological framework centered on learning from reaction examples and generalizing to novel targets.

Molecular Representation: Structures are typically encoded as Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings, molecular graphs, or learned embeddings. Advanced representations like reaction fingerprints (rxnfp) capture the holistic transformation of a reaction, incorporating both structural and chemical context [21].

Model Architectures: Single-step retrosynthesis models commonly employ:

- Sequence-to-sequence models that treat retrosynthesis as a translation problem from product to reactants

- Graph-to-sequence models that leverage molecular graph representations

- Transformer architectures with attention mechanisms that capture long-range dependencies in molecular structures

- Graph neural networks that explicitly model atomic interactions and bond formations

Multi-step Planning: For complete synthetic route planning, data-driven systems employ algorithms such as:

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) for balanced exploration and exploitation of the retrosynthetic tree

- Neural-guided A* search (Retro*) which uses neural networks to estimate synthetic cost [21]

- String-based optimization in reaction fingerprint space that grows synthetic pathways by minimizing distance to known synthetic routes [21]

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Data-Driven CASP Tools

| Platform | Architecture | Top-1 Accuracy (%) | Round-Trip Accuracy (%) | Route Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBM RXN [16] | Transformer-based | 54.4 | 65.2 | 48.7 |

| AiZynthFinder [13] | Template-based neural network | 49.7 | 61.8 | 45.3 |

| ChemEnzyRetroPlanner [13] | Hybrid AI with RetroRollout | 58.9 | 70.1 | 55.2 |

| BioNavi-NP [13] | Deep learning network | 52.6 | 63.5 | 50.1 |

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Strategic Advantages and Limitations

Both rule-based and data-driven CASP approaches present distinct strategic advantages and limitations that determine their appropriate application contexts.

Rule-based systems excel in chemical interpretability, with each disconnection traceable to established chemical principles. They perform reliably on well-characterized reaction types and can incorporate deep chemical knowledge about regioselectivity, stereochemistry, and reaction conditions. However, these systems suffer from knowledge base incompleteness, inability to generalize beyond encoded rules, and high development costs for domain expansion. Their performance is inherently limited by the breadth and depth of human-curated knowledge [13].

Data-driven systems offer superior scalability, continuous improvement with additional data, and discovery of novel transformations not explicitly documented in rules. They demonstrate particularly strong performance on popular reaction types with abundant training examples. Limitations include potential generation of chemically implausible suggestions, "black box" decision processes, and performance degradation on rare or novel reaction classes with limited training data [21].

Application Performance in Pharmaceutical Contexts

In pharmaceutical development, CASP systems are evaluated based on route feasibility, cost efficiency, and strategic alignment with medicinal chemistry constraints. Recent benchmarks indicate that hybrid approaches combining data-driven prediction with rule-based validation demonstrate superior performance in industrial applications.

Target Complexity Handling: Data-driven systems show enhanced performance on complex pharmaceutical targets with unusual structural motifs, where traditional rules may be insufficient. For example, systems like Retro* have successfully planned routes for complex natural products by learning from biosynthetic pathways [21].

Reaction Condition Prediction: Advanced data-driven CASP platforms now incorporate reaction condition recommendation as an integral component, predicting catalysts, solvents, temperatures, and yields with increasing accuracy. Platforms like IBM RXN and ChemEnzyRetroPlanner have demonstrated >70% accuracy in recommending viable reaction conditions for published transformations [13].

Table 3: Application-Based Performance Metrics for CASP Methodologies

| Application Domain | Rule-Based Success Rate | Data-Driven Success Rate | Key Performance Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecule drug candidates | 68% | 72% | Route feasibility, step count |

| Natural product synthesis | 45% | 63% | Strategic disconnections |

| Enzymatic hybrid routes | 38% | 58% | Biocompatibility prediction |

| Patent-free route design | 52% | 79% | Novelty of transformations |

| Green chemistry optimization | 61% | 56% | Environmental impact metrics |

Experimental Protocols for CASP Evaluation

Benchmarking Methodology for Retrosynthesis Algorithms

Rigorous evaluation of CASP systems requires standardized benchmarking protocols that assess both single-step and multi-step performance. The following methodology outlines a comprehensive evaluation framework:

Dataset Curation: Utilize established reaction datasets such as USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office), Pistachio, or Reaxys with standardized splits for training, validation, and testing [21]. For multi-step evaluation, use curated sets of target molecules with known synthetic routes, ensuring diversity in structural complexity and synthetic approaches.

Single-Step Evaluation Metrics:

- Top-k Accuracy: Proportion of test reactions where the true reactant set appears in the top-k predictions

- Round-Trip Accuracy: Forward prediction consistency check where predicted reactants are fed into forward prediction models to verify recovery of original product

- Chemical Validity: Percentage of generated reactant sets that represent chemically valid structures

- Reaction Center Recovery: Atom-mapping accuracy between products and predicted reactants

Multi-Step Evaluation Metrics:

- Route Success Rate: Percentage of target molecules for which a chemically valid and complete route to available starting materials is found

- Average Step Count: Mean number of steps in proposed synthetic routes

- Commercial Availability: Percentage of required starting materials that are commercially available

- Synthetic Accessibility Score: Computational assessment of route feasibility using metrics like SAscore or SCScore

Case Study: Evaluating ChemEnzyRetroPlanner Hybrid Performance

A recent study evaluated the hybrid organic-enzymatic synthesis planning platform ChemEnzyRetroPlanner using the following experimental protocol [13]:

Target Selection: 150 complex molecules including pharmaceutical intermediates, natural products, and agrochemicals were selected from literature with known synthetic routes.

Planning Protocol: For each target, the platform executed the following workflow:

- Hybrid Retrosynthesis Planning: Simultaneous exploration of organic and enzymatic transformations using the RetroRollout* search algorithm

- Reaction Condition Prediction: AI-driven recommendation of solvents, catalysts, and conditions for each transformation step

- Plausibility Evaluation: Multi-factor scoring of proposed routes based on yield prediction, step economy, and green chemistry metrics

- Enzyme Recommendation: Identification of suitable biocatalysts for enzymatic steps with active site validation

- In Silico Validation: Molecular docking of proposed substrates into enzyme active sites to verify compatibility

Performance Assessment: The platform achieved a 55.2% complete route success rate, outperforming purely organic data-driven approaches (42.7%) and rule-based systems (38.4%) on the same target set. The hybrid routes demonstrated an average 23% reduction in step count and 31% improvement in estimated overall yield compared to literature routes [13].

Visualization of CASP Workflows and System Architectures

Data-Driven CASP System Architecture

Diagram 1: Data-Driven CASP Architecture

Retrosynthesis Search Algorithm Comparison

Diagram 2: Retrosynthesis Search Algorithm Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CASP Implementation

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [16] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Molecular visualization, descriptor calculation, chemical structure standardization | Fundamental chemical representation and manipulation for custom CASP development |

| Chemprop [16] | Machine learning package | Predicts molecular properties (solubility, toxicity) using message-passing neural networks | Molecular property prediction for route evaluation and compound prioritization |

| AutoDock [16] | Molecular docking software | Virtual screening of molecular interactions through docking simulations | Enzyme-substrate compatibility validation in hybrid organic-enzymatic synthesis |

| IBM RXN [16] | Cloud-based AI platform | Reaction prediction and retrosynthesis planning using transformer models | Automated single-step and multi-step synthesis planning with web interface |

| AiZynthFinder [13] | Open-source software | Retrosynthetic planning using neural network and search algorithm | Rapid route identification for small molecules with commercial availability checks |

| ChemEnzyRetroPlanner [13] | Hybrid planning platform | Combines organic and enzymatic strategies with AI-driven decision-making | Sustainable synthesis planning with biocatalytic steps and condition recommendation |

| Schrödinger [16] | Molecular modeling suite | Comprehensive computational chemistry platform for drug discovery | High-accuracy molecular modeling for complex synthesis challenges |

| Gaussian [16] | Computational chemistry software | Quantum mechanical calculations for reaction mechanism prediction | Electronic-level understanding of reaction pathways and feasibility assessment |

| D(+)-Raffinose pentahydrate | D-(+)-Raffinose Pentahydrate|Research Grade|[Your Company] | Bench Chemicals | |

| IRL 1038 | IRL 1038, MF:C68H92N14O15S2, MW:1409.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution of Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning from rule-based to data-driven paradigms represents a significant advancement in organic chemistry, with profound implications for drug development and materials science. While rule-based systems provide chemically interpretable solutions grounded in established principles, data-driven approaches offer unprecedented scalability and discovery potential through pattern recognition in large reaction datasets. The emerging trend toward hybrid systems that integrate the strengths of both approaches—such as ChemEnzyRetroPlanner's combination of AI-driven search with enzymatic transformation rules—points to the future of CASP as a synergistic technology [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application contexts of these complementary approaches is essential for leveraging CASP technologies to accelerate synthetic innovation. As data-driven methods continue to evolve with advances in deep learning and the availability of larger reaction datasets, their integration with the chemical wisdom embedded in rule-based systems will likely define the next generation of synthesis planning platforms, ultimately enabling more efficient, sustainable, and innovative synthetic strategies.

The paradigm of chemical discovery is undergoing a radical transformation, shifting from manual, intuition-driven experimentation to autonomous, data-driven processes. Central to this shift is the development and implementation of closed-loop systems that seamlessly integrate algorithmic planning, robotic execution, and analytical feedback. Framed within ongoing research on data-driven organic synthesis platforms, this whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these integrated systems. We detail the core architectural components, present standardized experimental protocols, and quantify performance through comparative data analysis. The discussion is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand and implement these transformative technologies in molecular discovery and optimization.

In the iterative design-make-test-analyze cycle of molecular discovery, the physical synthesis and testing of candidates remain a critical bottleneck [2]. Data-driven organic synthesis platforms aim to overcome this by creating closed-loop systems where algorithms propose synthetic targets and routes, robotics execute the chemistry, and inline analytics provide immediate feedback to inform subsequent cycles [22] [16]. This convergence of disciplines—cheminformatics, robotics, and machine learning—enables the exploration of chemical space at unprecedented speed and scale. The ultimate goal is a resilient, adaptive platform capable of autonomous discovery, moving beyond mere automation to systems that learn and improve from every experiment [2].

Core Components of a Closed-Loop Synthesis Platform

A functional closed-loop system is built upon three tightly integrated pillars: intelligent software for planning and analysis, versatile hardware for physical execution, and robust data infrastructure for learning.

Algorithmic Intelligence: Planning and Decision-Making

The "brain" of the system involves multiple algorithmic layers. Retrosynthesis and Reaction Planning tools, such as ASKCOS, IBM RXN, and Synthia, use data-driven models to deconstruct target molecules into feasible synthetic routes [2] [16]. These models have evolved from rule-based systems to neural networks that can propose routes experts find indistinguishable from literature methods [2]. However, planning extends beyond retrosynthesis to include Reaction Condition Optimization. Machine learning models, particularly Bayesian optimization, are employed to navigate high-dimensional parameter spaces (e.g., solvent, catalyst, temperature, time) to maximize yield or selectivity [22]. Finally, Adaptive Decision-Making algorithms interpret analytical results to decide the next action—whether to proceed to the next synthetic step, re-optimize conditions, or abandon a route—emulating a chemist's reasoning [2].

Robotic Hardware: Automated Execution

The "hands" of the system consist of automated platforms that modularize chemical operations. Two primary paradigms exist: Batch-Based Systems and Flow Chemistry Platforms [2]. Batch systems often use vial or plate-based arrays, with robotic grippers or liquid handlers for transfers, and modular blocks for heating, cooling, and stirring. Examples include platforms built around microwave vials [2] or the mobile robotic chemist described by Burger et al. [2]. Flow systems use computer-controlled pumps and valve manifolds to reconfigure reaction pathways dynamically, offering advantages in heat/mass transfer and safety for hazardous reactions [2]. A key hardware challenge is the automation of purification and analysis between multi-step sequences, which often requires creative engineering solutions like catch-and-release purification [2].

Analytical and Data Infrastructure: The Feedback Loop

Real-time, inline analysis is what closes the loop. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) is the most common analytical modality, providing data on identity, purity, and yield [2]. The integration of universal quantification methods, such as Corona Aerosol Detection (CAD), is an area of active development to overcome the need for compound-specific calibration [2]. The resulting data streams into a centralized Data Lake, where it is curated and structured using tools like the Open Reaction Database [2]. This repository fuels the machine learning models, creating a virtuous cycle of self-improvement. The platform's "experience"—rich in procedural detail—complements the broad but often sparse data found in public reaction databases [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Platform Hardware Architectures

| Architecture | Description | Key Advantages | Common Challenges | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch (Vial/Plate-Based) | Reactions performed in discrete, separate vessels with automated liquid handling and transfer. | High flexibility, simple parallelization, disposable vessels on failure. | Automation of intermediate workup/purification, evaporative losses. | Multi-step synthesis of novel pharmaceutical candidates [2]. |

| Continuous Flow | Reactions performed in a continuously flowing stream within tubular reactors. | Excellent heat/mass transfer, inherent safety, precise reaction control. | Solubility of intermediates, risk of clogging, complex planning. | Optimization of hazardous or exothermic reactions [2]. |

| Hybrid (Mobile Robot) | A mobile robotic manipulator that transports samples between fixed, modular workstations. | Highly flexible use of existing lab equipment, adaptable workflow. | Slower cycle times, complex spatial coordination. | Autonomous exploration of photocatalyst mixtures [2]. |

Experimental Implementation: Protocols and Workflows

The operation of a closed-loop system follows a defined, iterative protocol. The following methodology synthesizes approaches from state-of-the-art platforms [2] [22].

Protocol: Single-Step Reaction Optimization via Closed-Loop

Objective: To autonomously discover the optimal conditions (Catalyst, Ligand, Solvent, Temperature) for a given transformation to maximize yield.

Algorithmic Setup:

- Define the chemical reaction (SMILES strings for reactants and product).

- Define the parameter search space (e.g., list of 10 catalysts, 15 ligands, 8 solvents, temperature range 25-100°C).

- Initialize a Bayesian optimization algorithm with a prior model, if available from historical data.

Robotic Preparation:

- The platform accesses its chemical inventory, dispensing stock solutions of reactants into a series of reaction vials (e.g., in a 96-well plate) [2].

- According to the first set of conditions proposed by the optimizer, the robot dispenses the specified volumes of catalyst, ligand, and solvent to each vial.

Execution and Analysis:

- The plate is transferred to a heated, agitated station for the prescribed reaction time.

- After quenching, samples are automatically transferred from each vial to an LC/MS system equipped with an autosampler [2].

- Chromatograms and mass spectra are automatically processed. Yield is quantified using a universal detector (e.g., CAD) or by integrating UV peaks relative to an internal standard.

Feedback and Iteration:

- The measured yield for each condition is fed back to the Bayesian optimization algorithm.

- The algorithm updates its model of the reaction landscape and proposes the next, most informative set of conditions to test.

- Steps 2-4 are repeated until a yield threshold is met or a predefined number of experiments is completed.

Protocol: Multi-Step Synthesis with Inline Analysis

Objective: To autonomously execute a multi-step synthetic route with quality control after each step.

Route Planning and Translation:

- A target molecule is input into a retrosynthesis planner (e.g., ASKCOS) [2] [16].

- A high-probability route is selected and translated into a hardware-agnostic procedural language, such as the Chemical Description Language (XDL) [2].

- The XDL script is compiled into a machine-specific sequence of low-level operations (e.g.,

aspirate 1.5 mL from vial A1).

Closed-Loop Step Execution:

- The robotic platform executes the first reaction step as per the compiled instructions.

- Upon completion, an aliquot is automatically sampled and analyzed by LC/MS.