Error Handling in Autonomous Synthesis Platforms: From Failure Management to Robust Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of error handling strategies for autonomous synthesis platforms used in chemical and materials discovery.

Error Handling in Autonomous Synthesis Platforms: From Failure Management to Robust Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of error handling strategies for autonomous synthesis platforms used in chemical and materials discovery. It explores the fundamental causes of failure in AI-driven laboratories, examines methodological approaches for error detection and recovery, details troubleshooting and optimization techniques for resilient systems, and presents validation frameworks for comparative performance assessment. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and emerging solutions for transforming experimental failures into accelerated discovery in biomedical research.

Understanding Autonomous Laboratory Failure Modes: Why Experiments Go Wrong

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What distinguishes a true "method failure" from a simple execution error in autonomous synthesis platforms? A true method failure occurs when the autonomous system's fundamental approach or planning is incorrect, while execution errors represent correct plans that fail during implementation. Method failures include incorrect task decomposition, invalid synthesis route planning, or fundamentally flawed experimental designs that cannot produce the desired outcome even with perfect execution. In contrast, execution errors might include robotic arm miscalibration, liquid handling inaccuracies, or sensor malfunctions that disrupt otherwise sound methods [1] [2].

Q2: Why do autonomous laboratory systems sometimes achieve high success rates in materials discovery but struggle with organic synthesis? Recent research demonstrates this disparity stems from fundamental differences in process complexity and data availability. The A-Lab system achieved 71% success synthesizing predicted inorganic materials by leveraging well-characterized solid-state reactions, while organic synthesis involves more complex molecular transformations and reaction mechanisms with less comprehensive training data [2]. Additionally, autonomous platforms for organic synthesis face challenges with purification, air-sensitive chemistries, and precise temperature control that are less problematic in materials synthesis [3].

Q3: How can researchers determine whether failure stems from AI planning versus hardware execution? Systematic failure analysis requires examining specific failure signatures. AI planning failures typically manifest as incorrect task decomposition, invalid synthesis route selection, or logically flawed experimental sequences. Hardware execution failures present as robotic positioning errors, liquid handling inaccuracies, sensor reading failures, or equipment communication breakdowns. Implementing comprehensive logging that captures both the AI's decision rationale and hardware sensor readings is essential for accurate diagnosis [1] [2].

Q4: What are the most common failure points in fully autonomous drug synthesis workflows? The most vulnerable points in autonomous drug synthesis include: (1) synthesis planning where AI proposes chemically invalid routes, (2) purification steps where platforms lack universal strategies, (3) analytical interpretation where AI misidentifies products, and (4) hardware-specific issues like flow chemistry clogging or vial-based system cross-contamination. These failures are particularly consequential in pharmaceutical applications where they can impact patient safety and regulatory approval [3] [4].

Q5: How do regulatory considerations impact error handling strategies for autonomous systems in drug development? Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require rigorous validation and transparent documentation of AI systems used in drug development. This impacts error handling by necessitating comprehensive audit trails, predefined acceptance criteria for autonomous decisions, and explicit uncertainty quantification. For high-risk applications affecting patient safety or drug quality, regulators expect detailed information about AI model architecture, training data, validation processes, and performance metrics [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Planning and Reasoning Failures

Problem: Autonomous systems generate plausible but chemically impossible synthesis routes or experimental plans.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check if the proposed reactions violate fundamental chemical principles

- Verify that suggested precursors are commercially available or synthesizable

- Confirm that reaction conditions fall within physically possible parameters

- Validate that the experimental sequence follows logical dependencies

Resolution Strategies:

- Implement chemistry-aware validation rules that check for atomic balance, functional group compatibility, and thermodynamic feasibility

- Incorporate retrosynthesis analysis tools like Synthia or ASKCOS to verify proposed routes [3]

- Enhance AI training with broader reaction databases and explicit constraint learning

- Introduce human-in-the-loop verification for critical planning decisions

Prevention Measures:

- Train AI models on high-quality, curated reaction databases with explicit failure examples

- Implement ensemble methods that combine multiple planning approaches

- Develop better uncertainty quantification to flag low-confidence proposals

Hardware and Execution Failures

Problem: Robotic systems fail to correctly perform physical operations despite sound experimental plans.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check robotic calibration and positioning accuracy

- Verify liquid handling volumes and transfer completeness

- Confirm sensor readings against known standards

- Test communication between software controllers and hardware components

Resolution Strategies:

- Implement automated calibration routines using standardized references

- Add vision systems to verify critical operations like powder transfer or liquid dispensing

- Incorporate redundant sensors for critical parameters (temperature, pressure, pH)

- Develop fault detection algorithms that identify deviations from expected operation signatures

Prevention Measures:

- Establish preventive maintenance schedules with usage-based triggers

- Design hardware architectures with modular components for easy replacement

- Create comprehensive simulation environments to test hardware commands before physical execution

Analytical Interpretation Failures

Problem: AI systems mischaracterize experimental outcomes based on analytical data.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Verify analytical instrument calibration using standard samples

- Check that spectral interpretation algorithms are appropriate for the chemical system

- Confirm that reference databases contain relevant compounds

- Validate that signal-to-noise ratios support the conclusions drawn

Resolution Strategies:

- Implement orthogonal analytical techniques to confirm key findings (e.g., LC-MS plus NMR) [2]

- Apply ensemble analytical models that combine multiple interpretation approaches

- Incorporate human expert review for ambiguous or critical results

- Develop confidence metrics for analytical interpretations that trigger verification

Prevention Measures:

- Train interpretation models on comprehensive spectral libraries with known artifacts

- Regularly update reference databases with newly characterized compounds

- Implement continuous model evaluation against ground-truth validation samples

Autonomous System Performance Data

Table 1: Task Completion Rates Across Autonomous Agent Frameworks [1]

| Agent Framework | Web Crawling Success (%) | Data Analysis Success (%) | File Operations Success (%) | Overall Success (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaskWeaver | 16.67 | 66.67 | 75.00 | 50.00 |

| MetaGPT | 33.33 | 55.56 | 50.00 | 47.06 |

| AutoGen | 16.67 | 50.00 | 50.00 | 38.24 |

Table 2: Failure Cause Taxonomy in Autonomous Systems [1] [2]

| Failure Category | Specific Failure Modes | Frequency | Impact Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning Errors | Incorrect task decomposition, invalid synthesis routes, logically flawed sequences | High | Critical |

| Execution Issues | Robotic positioning errors, liquid handling inaccuracies, sensor failures | Medium | Moderate-Severe |

| Analytical Interpretation | Spectral misidentification, yield miscalculation, phase misclassification | Medium | Moderate |

| Hardware Limitations | Clogging in flow systems, evaporative losses, temperature control failures | Low-Medium | Variable |

| Model Limitations | Training data gaps, overfitting, poor generalization to new domains | High | Critical |

Experimental Workflows

Autonomous Experiment Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Autonomous Synthesis Platforms [3] [2]

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Compatibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Block Libraries | MIDA-boronates, Common amino acids, Heterocyclic cores | Provide chemical diversity for synthesis | Must be compatible with automated dispensing systems |

| Catalysts | Pd(PPh3)4, Organocatalysts, Enzyme cocktails | Enable key bond-forming reactions | Stability in automated storage conditions critical |

| Solvents | DMF, DMSO, Acetonitrile, Ether solvents | Reaction media and purification | Must minimize evaporative losses in open platforms |

| Analytical Standards | NMR reference compounds, LC-MS calibration mixes | Instrument calibration and quantification | Essential for validating autonomous analytical interpretation |

| Derivatization Agents | Silylation reagents, Chromophores for detection | Enhance analytical detection | Required for compounds with poor inherent detectability |

| Purification Materials | Silica gel, C18 cartridges, Scavenger resins | Product isolation and purification | Limited by current automation capabilities |

Failure Resolution Protocol

Within autonomous synthesis platforms, the physical execution of experiments by robotic hardware is a common point of failure. Researchers and professionals in drug development frequently encounter issues related to the dispensing of solids and handling of liquids, which can compromise experimental integrity and slow the pace of discovery. This guide addresses specific, high-frequency hardware limitations and provides targeted troubleshooting methodologies to enhance system robustness.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Solid Dispensing Issues

Solid dispensing, critical for reactions in automated chemistry and materials synthesis, is prone to specific failures that can halt an autonomous workflow [2].

| Problem | Root Cause | Troubleshooting Method | Key Parameters & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powder Clogging | Moisture absorption; static cling; particle bridging [2]. | Use of anti-static coatings; implement humidity-controlled enclosures; incorporate mechanical agitators or vibrating feeders [2]. | Target relative humidity: <15%; Agitation frequency: 5-10 Hz. Outcome: >80% reduction in clog-related downtime [2]. |

| Inaccurate Powder Dosing | Variations in powder density; inconsistent feed rate; sensor calibration drift. | Perform volumetric-to-gravimetric calibration; use force sensors for real-time feedback; install automated tip-over mass check stations [6]. | Dosing accuracy: <1 mg deviation; Calibration frequency: Before each experiment campaign. Outcome: Achieve >95% dosing precision [6]. |

| Cross-Contamination | Residual powder in dispensing tips or pathways; airborne particulates. | Implement active purge cycles with inert gas; use disposable liner sleeves; schedule ultrasonic cleaning of reusable parts [7]. | Purge gas pressure: 2-3 bar; Ultrasonic cleaning duration: 15 min. Outcome: Eliminate detectable cross-contamination (below ICP-MS detection limits) [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Powder Dispensing Accuracy

Objective: To validate the gravimetric accuracy of a solid dispensing unit after maintenance or when introducing a new powder reagent [6].

- Setup: Place an calibrated micro-balance at the dispensing location. Tare the balance.

- Execution: Command the robotic arm to dispense a pre-defined volume of the test powder onto the balance. Use the robot's internal volume-to-mass conversion factor.

- Measurement: Record the actual mass measured by the balance. Repeat this process 10 times to establish a dataset.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean dispensed mass and the standard deviation. Compare the mean to the target mass to determine bias, and use the standard deviation to assess precision.

- Calibration: If the bias exceeds the acceptable threshold (e.g., 1%), update the robot's volume-to-mass conversion factor in the control software and repeat the protocol until accuracy is achieved [6].

Common Liquid Handling Issues

Precision in liquid handling is fundamental for genomics, drug development, and diagnostic assays [7]. failures here directly impact data integrity [7].

| Problem | Root Cause | Troubleshooting Method | Key Parameters & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Clogging | Particulates in reagent; precipitate formation; dried reagent in tips [8]. | Pre-filtration of reagents (e.g., 0.2 µm filter); implement regular solvent purge cycles; schedule tip cleaning with solvents like acetone [8]. | Filter pore size: 0.2 µm; Backflush pressure: 1-2 bar. Outcome: 90% reduction in clogging incidents [8]. |

| Uneven Dispensing & Bubbles | Air bubbles in fluid path; unsteady pressure; worn seals; improper wetting [8]. | Centrifuge or degas reagents under vacuum; adjust fluid pressure to ≥60 psi; extend valve-open time to >0.015 seconds; inspect and replace seals [8]. | Degas time: 15 min; Valve open time: >0.015 s. Outcome: 80% improvement in flow consistency; 40% reduction in air pockets [8]. |

| Liquid Stringing | Adhesive or viscous liquid properties; high dispensing height; slow tip retraction [8]. | Optimize Z-axis retraction speed and height; use low-adhesion coated tips; apply an anti-static bar to dissipate charge for non-aous solvents [8]. | Retraction speed: >20 cm/s; Retraction height: 1-2 mm. Outcome: Elimination of visible filaments between tip and target [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Verifying Liquid Handling Precision and Accuracy

Objective: To measure the volumetric precision and accuracy of a liquid handling robot using a gravimetric method [7].

- Reagent Preparation: Use purified water as the test reagent. Allow it to equilibrate to the laboratory ambient temperature to minimize density fluctuations.

- Setup: Tare a precision micro-balance along with a clean, dry receiving vessel.

- Dispensing: Program the robot to dispense a specific volume (e.g., 10 µL) into the vessel. Record the mass displayed on the balance.

- Replication: Repeat the dispense-and-weigh cycle at least 10 times for statistical significance.

- Calculation:

- Accuracy: Calculate the average dispensed mass. Convert this mass to volume using the density of water at the recorded temperature. Compare this volume to the target volume.

- Precision: Calculate the standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV) for the series of dispensed masses. A CV of <1% is typically acceptable for most applications [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common points of failure in a fully autonomous synthesis platform?

The most common failures occur at the interface between hardware and the physical world. This includes solid dispensing units jamming due to hygroscopic or electrostatic powders [2], liquid handling robots suffering from clogs or inaccurate dispensing due to bubble formation [8] [7], and purification steps failing because a universally applicable automated strategy does not yet exist [3]. Hardware also struggles with unexpected events like precipitate formation causing flow path clogs in fluidic systems [2].

2. How can we improve the robustness of robotic hardware against unpredictable chemical behaviors?

Improving robustness requires a multi-layered approach:

- Advanced Sensing: Integrate in-line sensors (e.g., pressure, optical) for real-time clog detection [2].

- Adaptive Software: Develop algorithms that can trigger pre-defined cleaning or corrective protocols upon sensing an anomaly [2].

- Hardware Redundancy: For critical components like dispensing valves, having a backup can allow the system to switch and continue operations [6].

- Modular Design: As highlighted in recent research, platforms with modular hardware architectures and mobile robots can be more easily reconfigured to work around failed components or to accommodate different chemical tasks [2].

3. Our automated platform's retrosynthesis planning is excellent, but execution fails. Why?

This is a known bottleneck. Computer-aided synthesis planning tools can propose viable routes, but they often lack the procedural details critical for physical execution [3]. The subtleties of order-of-addition, precise timing, and handling of exothermic reactions are frequently missing from training databases. Furthermore, proposed routes are not scored for their automation compatibility, meaning the plan may involve steps that are notoriously difficult to automate, such as those requiring complex solid handling or manual intervention for purification [3].

4. What data and metrics should we log to diagnose intermittent dispensing errors?

Comprehensive logging is essential for diagnosing elusive errors. Key data points include:

- Environmental Data: Laboratory temperature and humidity [8].

- Liquid Handling Parameters: For every dispense, log fluid pressure, valve open/close times, and tip type [8] [7].

- Solid Handling Parameters: Agitator operation status, purge cycles, and motor current draw (which can indicate jamming) [2].

- System Performance: Log the results of regular self-checks, such as tip presence verification or balance calibration status [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Autonomous Platforms |

|---|---|

| Filtered Reagent Vials | Pre-filtered reagents (0.2 µm) prevent particulate-induced clogs in liquid handling pathways [8]. |

| Anti-Static Additives & Coatings | Reduce powder adhesion and static cling in solid dispensing systems, improving flow and accuracy [2]. |

| Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved air from solvents prior to dispensing, preventing bubble formation that causes volumetric inaccuracies [8]. |

| Standardized Solvent Library | A curated inventory of common, high-purity solvents with pre-loaded density and viscosity data for precise liquid class settings in pipetting robots [7]. |

| Ceramic-Cut Dispensing Tips | Tips with sharp, clean-cut orifices minimize liquid stringing and provide more consistent droplet detachment for viscous liquids [8]. |

| 3-O-(2'E ,4'Z-Decadienoyl)-20-O-acetylingenol | 3-O-(2'E ,4'Z-Decadienoyl)-20-O-acetylingenol, MF:C32H44O7, MW:540.7 g/mol |

| 5,6,4'-Trihydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone | 5,6,4'-Trihydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone|Natural Flavonoid |

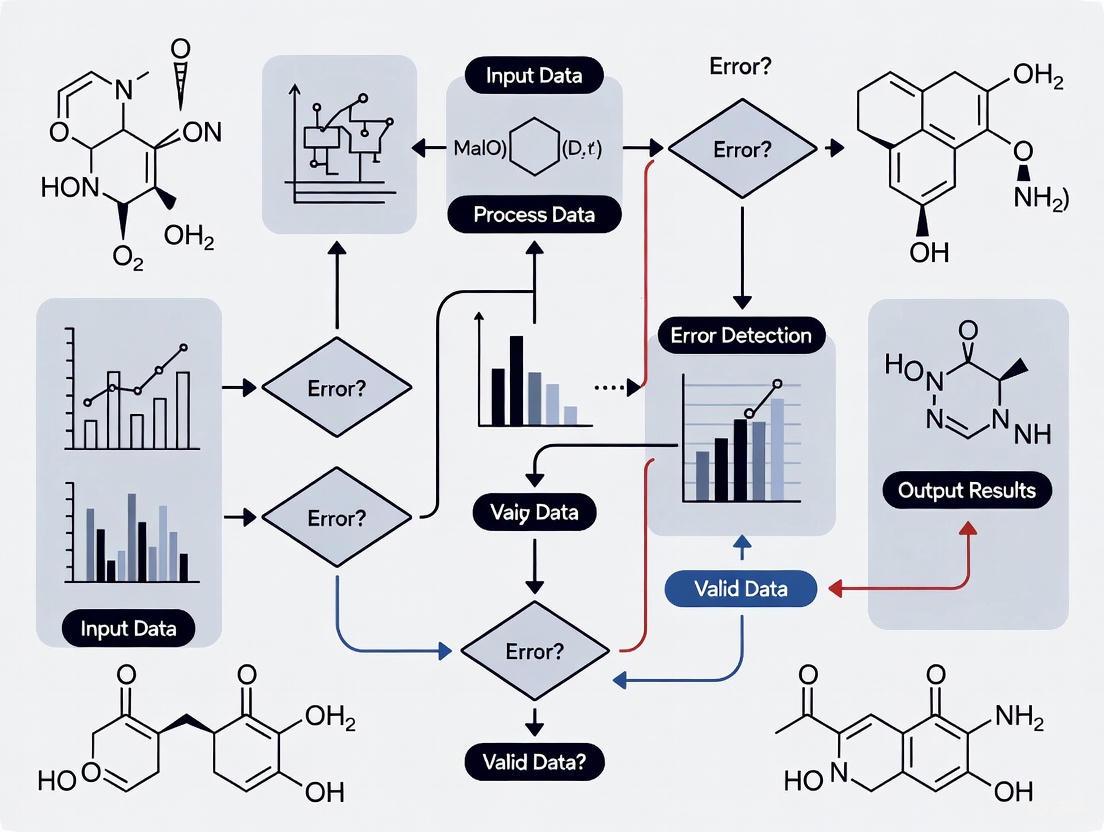

Experimental Workflow for Error Handling

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for detecting and handling hardware dispensing errors within an autonomous experimental cycle, integrating the troubleshooting guides and FAQs above.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists working with autonomous synthesis platforms in drug discovery. It addresses common cognitive challenges related to AI model limitations and errors that arise during cross-domain application.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common AI Model Failures

Issue 1: AI Generates Irrelevant or Hallucinated Outputs in Clinical Data Analysis

- Symptoms: The model provides answers disconnected from the query (e.g., interpreting "physical activity" as "glasses of wine per week") or invents unsupported facts [9].

- Root Cause: Use of generic Large Language Models (LLMs) trained on broad, non-clinical datasets. These models misinterpret domain-specific terminology, abbreviations, and the semi-structured nature of medical records [9].

- Solution:

- Implement a purpose-built, clinically trained model specifically fine-tuned on medical text [9].

- Employ Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to ground the AI's responses in a verified, domain-specific knowledge base [10].

- Maintain a human-in-the-loop (HITL) for verification. The AI should provide outputs with traceable links to source material for human approval [9].

Issue 2: Critical Thinking "Atrophy" or Over-reliance on AI

- Symptoms: Researchers accept AI outputs without independent verification, leading to reduced problem-solving engagement and weaker analytical abilities [11] [12].

- Root Cause: Cognitive offloading, where the AI is used as a crutch rather than a tool for growth. This is exacerbated by algorithmic bias in training data [11] [12].

- Solution:

- Define a "collaborative" workflow. Use AI for data processing and hypothesis generation, but mandate manual, critical evaluation of all results [11].

- Incorporate AI-free problem-solving exercises into the experimental design phase to preserve cognitive flexibility [12].

- Actively seek disconfirming evidence for AI-generated hypotheses to counter bias [12].

Issue 3: Poor Model Performance When Transferring to a New Domain (e.g., from Chemistry to Proteomics)

- Symptoms: A model successful in one domain (e.g., predicting small molecule interactions) fails to maintain accuracy in a related but distinct domain (e.g., protein folding prediction) [13] [9].

- Root Cause: Domain shift. The statistical relationships learned from the source domain's data do not hold in the target domain due to differing feature spaces or distributions [9].

- Solution:

- Apply transfer learning with targeted fine-tuning. Retrain the final layers of the pre-trained model using a high-quality, curated dataset from the new domain [13].

- Use domain adaptation techniques, such as adversarial training, to learn domain-invariant features [13].

- Ensure data quality and representativeness in the target domain to prevent learning spurious correlations [13] [14].

Issue 4: AI System Failure Without Graceful Error Handling

- Symptoms: The entire autonomous synthesis or analysis pipeline crashes or produces catastrophic outputs from a single-point failure [15].

- Root Cause: Lack of anticipatory design and fault tolerance in the agentic AI system [15].

- Solution:

- Implement graceful degradation. Design systems to maintain core critical functions even when secondary modules fail [15].

- Build in redundancy and self-healing protocols. Use algorithmic diversity for key tasks and define automated recovery sequences for common error states [15].

- Establish clear HITL escalation paths for errors exceeding a predefined risk threshold [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can AI truly perform "critical thinking" in drug discovery? A: No. AI excels at data-driven pattern recognition, calculation, and prediction but lacks the human experience, insight, and ethical reasoning essential for true critical thinking [11]. AI processes are recursive and statistical, not reflective. Its role is to augment, not replace, human reasoning and innovation [11] [16].

Q2: What is the "missing middle" problem in generic AI models? A: When processing long contexts (e.g., a patient chart), generic LLMs often remember information from the beginning and end of the text but "forget" or gloss over crucial details in the middle. This leads to inaccurate or incomplete analyses [9].

Q3: How can we measure the impact of AI reliance on our team's cognitive skills? A: Monitor metrics related to error identification and resolution. A study on AI system failures found that 67% stemmed from improper error handling [15]. Internally, track Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR) and Error Amplification Factor (do small errors cascade?). An increase may indicate over-reliance and degraded troubleshooting skills [15].

Q4: Are there quantitative studies on AI's impact on human cognition? A: Yes. Research indicates a negative correlation between frequent AI usage and critical-thinking abilities [12]. A non-linear relationship exists: moderate use has minimal impact, but excessive reliance leads to significant diminishing cognitive returns [12]. Furthermore, an MIT Media Lab study suggested excessive AI reliance may contribute to "cognitive atrophy" [11].

Q5: What is the most effective way to integrate a human into an autonomous AI synthesis loop? A: The most effective model is Human-as-Approver, not Human-as-Operator. Change the human's role from manual search and data entry to validating AI-curated results. The AI should present findings with source citations, and the human's task is to approve, reject, or refine them, maintaining accountability and oversight [9].

Table 1: Documented AI Limitations & Cognitive Impact Studies

| Limitation / Finding | Quantitative Data / Description | Source Context |

|---|---|---|

| Error Handling Root Cause | 67% of AI system failures stem from improper error handling (not core algorithms). | Study by Stanford's AI Index Report (2023) [15] |

| Cognitive Atrophy Correlation | "Excessive reliance on AI-driven solutions" may contribute to "cognitive atrophy." | MIT Media Lab study (mentioned in 2025 article) [11] |

| Critical Thinking Correlation | Negative correlation found between frequent AI usage and critical-thinking abilities. | Gerlich (2025) study [12] |

| Generic AI Hallucination Rate | High tendency to "hallucinate" or misinterpret clinical shorthand (e.g., "AS" as "as" not "aortic stenosis"). | Expert analysis from pharma AI CEO [9] |

| Self-Healing System Uptime | AI systems with self-healing capabilities achieved 99.99% uptime vs. 99.9% for traditional systems. | IBM research paper (2023) [15] |

Table 2: Domain-Specific AI Application Challenges in Pharma

| Domain / Task | Generic AI Challenge | Purpose-Built AI Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Note Analysis | Misinterprets semi-structured data, acronyms (e.g., "Pt"), and medical jargon. | Trained on clinical corpora to disambiguate terms based on document context [9]. |

| Pharmacovigilance | Struggles with reliable extraction of adverse event data from unstructured notes. | Fine-tuned for named entity recognition (NER) of drug and event terms, linked to source text [9]. |

| De Novo Molecule Design | May generate chemically invalid or non-synthesizable structures. | Integration with rule-based chemical knowledge and molecular dynamics simulations [13]. |

| Target Discovery | Predictions may lack biological plausibility due to data biases. | Multi-modal integration of omics data (genomics, proteomics) and pathway analysis [13] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Evaluating AI-Generated Drug Candidate Efficacy [13]

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of a Deep Learning (DL) model in predicting the biological activity of novel drug compounds.

- Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: Compile a large, high-quality dataset of known drug compounds paired with their corresponding quantitative biological activity measures (e.g., IC50).

- Model Training: Train a DL algorithm (e.g., a graph neural network) on the curated dataset. The input is the compound's molecular structure (e.g., SMILES string), and the output is the predicted activity.

- Validation: Use a held-out test set of known compounds to validate prediction accuracy (metrics: RMSE, R²).

- Experimental Corroboration: Synthesize top AI-predicted novel compounds and test their actual activity via in vitro assays (e.g., enzyme inhibition). Compare experimental results with AI predictions.

Protocol 2: Human-AI Collaborative Error Recovery [15]

- Objective: To measure the efficiency of hybrid human-AI teams in resolving complex system failures in an autonomous platform.

- Methodology:

- Failure Simulation: Use Chaos Engineering principles to inject realistic, complex faults (e.g., cascading API failures, corrupted data streams) into a simulated autonomous synthesis platform.

- Group Setup: Establish three test groups: (A) AI-only automated recovery, (B) Human-only troubleshooting, (C) Human-in-the-loop (HITL) with AI providing diagnostic summaries and suggested fixes.

- Metric Tracking: For each simulated failure, track Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR) and Resolution Success Rate.

- Analysis: Compare metrics across groups. A cited MIT-Harvard study found hybrid (HITL) approaches resolved failures 3.2 times faster than either humans or AI alone [15].

Visualization Diagrams

Title: AI Error Handling & Human-Escalation Workflow

Title: Domain Transfer Challenges & Mitigation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Addressing AI Limitations |

|---|---|

| Purpose-Built, Domain-Specific AI Model | An AI model pre-trained and fine-tuned on high-quality, curated data from the specific target domain (e.g., clinical notes, protein sequences). Function: Dramatically reduces hallucinations and improves accuracy by understanding domain jargon and context [9]. |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Framework | A system architecture that combines an LLM with a searchable, verified knowledge base (e.g., internal research databases, PubMed). Function: Grounds AI responses in factual sources, providing citations and reducing fabrication [10]. |

| Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Platform Interface | A software interface designed for collaborative review, not just data entry. It highlights AI suggestions, provides source evidence, and requires explicit human approval. Function: Maintains accountability, ensures oversight, and leverages human critical thinking for final judgment [15] [9]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) & Model Interpretability Tools | Software libraries (e.g., SHAP, LIME) and model architectures that provide insights into why an AI model made a specific prediction. Function: Builds trust, allows scientists to validate the biological/chemical plausibility of AI outputs, and identifies model biases [13] [14]. |

| High-Quality, Curated Domain Datasets | The fundamental "reagent" for any AI project. Function: The quality, size, and representativeness of training data directly determine model performance and generalizability. Investing in data curation is essential to overcome the "garbage in, garbage out" principle [13] [14]. |

| Multi-Modal Data Integration Pipelines | Tools that allow AI models to process and correlate different data types simultaneously (e.g., chemical structures, genomic data, histological images). Function: Enables more robust and biologically-relevant predictions by capturing complex, cross-domain relationships [13]. |

| 2,4,6-Trimethylbenzeneamine-d11 | 2,4,6-Trimethylbenzeneamine-d11, MF:C9H13N, MW:146.27 g/mol |

| 4-(2-Azidoethyl)phenol | 4-(2-Azidoethyl)phenol, MF:C8H9N3O, MW:163.18 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical data quality issues in autonomous synthesis platforms? The most critical data quality issues that hinder autonomous synthesis platforms are data scarcity, label noise, and inconsistent data sources [2]. Data scarcity limits the amount of available training data for AI models, while label noise (mislabeled data) and inconsistencies from multiple sources reduce the accuracy and reliability of these models, leading to failed experiments and inaccurate predictions [17] [2].

2. How does 'bad data' specifically impact AI-driven chemical discovery? Poor data quality directly compromises the performance of AI models. Inaccurate or biased data can lead AI to make irrelevant predictions, imperiling entire research initiatives [17]. For example, Gartner predicts that "through 2026, organizations will abandon 60% of AI projects unsupported by AI-ready data" [17]. In chemical synthesis, mislabeled data or incomplete reaction details can result in failed syntheses and incorrect route planning [3] [2].

3. What are the root causes of inconsistent data in automated laboratories? Inconsistent data often arises from integrating multiple instruments and data sources that lack standardized formats and handling procedures [2] [18]. This includes variations in data entry, evolving data sources, and a lack of unified data governance. In logging, for instance, different developers may adopt their own formatting approaches, leading to inconsistencies that complicate analysis [19].

4. Why is data scarcity a particular problem for autonomous discovery? AI models, particularly those for retrosynthesis or reaction optimization, require large, diverse datasets to make accurate predictions [3] [2]. Data scarcity is a fundamental impediment because experimental data in chemistry is often limited, proprietary, or not recorded with the necessary procedural detail for AI training. This lack of high-quality, diverse data prevents models from generalizing effectively to new problems [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Data Scarcity

Symptoms: AI models fail to generalize, produce low-confidence predictions, or cannot propose viable synthetic routes for novel molecules.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Pre-train models on large, general chemical databases (e.g., the Open Reaction Database [3]). Subsequently, fine-tune these models on your smaller, specific experimental dataset. This allows the model to apply broad chemical knowledge to a narrow domain.

- Implement Active Learning: Create a closed-loop system where the AI proactively identifies and proposes experiments for the areas of chemical space where its predictions are most uncertain.

- The AI model selects and proposes a batch of experiments with the highest prediction uncertainty.

- The robotic platform executes these experiments.

- Results are fed back into the training dataset.

- The model is retrained, improving its knowledge specifically where it was weakest [2].

Issue 2: Data Noise (Mislabeled/Inaccurate Data)

Symptoms: Unexpected experimental failures, AI models that learn incorrect patterns, and high variation in replicate experiments.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Automated Data Profiling and Cleansing:

- Profile Data: Use automated tools to scan datasets for anomalies like duplicate entries, values outside permitted ranges, or missing required fields [17] [18].

- Establish Validation Rules: Implement rule-based checks for data structure and logic (e.g., format validation for email fields, range validation for reaction temperatures) [18].

- Correct Errors: Apply data cleaning techniques such as standardization (e.g., converting all "Jones St" to "Jones Street"), deduplication, and imputation for missing values. AI can be used to automate the standardization and consolidation of duplicates [17].

- Multi-Modal Data Cross-Validation:

Symptoms: Broken data pipelines, inability to combine datasets from different instruments or labs, and errors during data integration and analysis.

Methodology for Resolution:

- Enforce Data Governance and Standardization:

- Set Policies: Define clear, organization-wide data standards for how data should be structured, formatted, and labeled [17] [18].

- Use a Metadata Catalog: Implement a searchable catalog of data assets that documents data definitions, rules, and lineage (metadata) to ensure shared understanding [17] [18].

- Standardize Early: Apply consistent formats and naming conventions at the point of data generation, not afterward [19] [18].

- Implement an Observability Pipeline:

- Route all data through a central processing layer before analysis.

- In this pipeline, automatically transform disparate data formats and schemas into a unified, consistent structure.

- This approach allows for reshaping data and omitting unneeded fields to reduce noise and inconsistency before the data reaches analytical systems [19].

| Data Quality Issue | Impact on Autonomous Synthesis | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Scarcity [2] | Limits AI model training and generalization. | Use transfer learning and active learning cycles [2]. |

| Label Noise [17] [2] | Causes AI models to learn incorrect patterns, producing inaccurate outputs. | Implement automated data validation and multi-modal data cross-validation [3] [18]. |

| Inconsistent Sources [2] [18] | Precludes data integration and breaks automated analysis scripts. | Enforce data governance and implement an observability pipeline for standardization [17] [19]. |

| Duplicate Data [17] [19] | Skews analysis, over-represents trends, increases storage costs. | Perform data deduplication and use unique identifiers for data entries [18]. |

| Outdated Data (Data Decay) [17] [18] | Leads to decisions that don't reflect present-day chemical knowledge or conditions. | Schedule regular data audits and updates; establish data aging policies [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Closed-Loop System for Data Quality Enhancement

Objective: To create a self-improving autonomous laboratory system that continuously enhances data quality by identifying and rectifying data noise and scarcity.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- AI Planning: Given a target molecule, the AI uses data-driven retrosynthesis tools (e.g., trained on reaction databases) to propose a synthetic route and initial reaction conditions [3].

- Robotic Execution: The robotic platform automatically executes the synthesis, handling liquid transfers, reaction control (heating/stirring), and sample collection [3] [2].

- Multi-Modal Analysis: The crude product is automatically analyzed using integrated instruments (e.g., UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR). Software algorithms process this data for substance identification and yield estimation [2].

- Data Quality Validation:

- Cross-Verification: The results from LC-MS and NMR are compared to check for consistency.

- Rule-Based Checks: Data is validated against pre-defined rules (e.g., yield between 0-100%, solvent name from a controlled vocabulary).

- Anomaly Detection: The system flags outcomes that are statistical outliers for expert review [17] [18].

- Knowledge Base Update: The verified, high-quality data—including the full procedural context and analytical results—is added to the project's database.

- Model Retraining: The AI planning model is periodically retrained on the updated knowledge base, allowing it to learn from both successes and failures, thereby improving its future predictions [2]. This closes the active learning loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Autonomous Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates precise dispensing of reagents and solvents, a foundational physical operation for running reactions [3] [2]. |

| Chemical Inventory System | Stores and manages a large library of building blocks and reagents, enabling access to diverse chemical space without manual preparation [3]. |

| LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Provides primary analysis for product identification and quantitation from reaction mixtures [3] [2]. |

| Benchtop NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) | Offers orthogonal analytical validation for structural elucidation, crucial for verifying product identity and detecting mislabeling [2]. |

| Data Observability Tool | A software platform that provides a central pane for monitoring, shaping, and standardizing data streams from all instruments, ensuring consistency [17] [19]. |

| Active Learning Software | An AI component that identifies the most informative experiments to run next, strategically overcoming data scarcity [2]. |

| N4-Ac-C-(S)-GNA phosphoramidite | N4-Ac-C-(S)-GNA phosphoramidite, MF:C39H48N5O7P, MW:729.8 g/mol |

| Fmoc-PEG6-Val-Cit-PAB-OH | Fmoc-PEG6-Val-Cit-PAB-OH, MF:C48H68N6O13, MW:937.1 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Proprietary Integration Issues

This guide addresses frequent challenges when integrating proprietary instruments and control systems into autonomous synthesis platforms.

Communication Failure with Proprietary Analytical Instruments

Problem: An automated synthesis platform cannot establish a connection with a proprietary benchtop NMR or UPLC-MS, resulting in failed data acquisition.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Steps | Underlying Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Device not found" or timeout errors. | Proprietary communication protocol or closed API. | 1. Verify Gateway Software: Install and configure any vendor-provided gateway or middleware software. [20]2. Check Emulation: Investigate if the instrument can emulate a standard (e.g., SCPI) command set.3. Utilize Adapters: Employ protocol adapters or hardware gateways to translate between systems. [21] | Autonomous platforms rely on seamless data exchange for closed-loop operation; protocol gaps halt the synthesis-analysis-decision cycle. [21] [20] |

| Intermittent data stream or corrupted data. | Unstable network connection or data packet issues. | 1. Network Isolation: Place the instrument on a dedicated, stable network segment to minimize packet loss.2. Data Validation: Implement software checksums to validate data integrity upon receipt. | Robust, uninterrupted data flow is critical for AI-driven analysis and subsequent decision-making in autonomous discovery. [2] |

Vendor Lock-In and Scalability Limitations

Problem: The autonomous laboratory's expansion is hindered because a proprietary system cannot integrate with new, third-party hardware or software components.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Steps | Underlying Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inability to add new robotic components or sensors. | Closed architecture and non-standard interfaces. [22] | 1. Middleware Solution: Use a flexible, open-source robotics middleware (e.g., ROS) as an abstraction layer. [20]2. Custom Driver Development: Commission the development of a custom API driver, acknowledging the high cost and effort. | Exploratory research requires modular, scalable platforms. Proprietary barriers directly oppose the need for flexible hardware architectures that can accommodate diverse chemical tasks. [2] |

| High costs and restrictive contracts for upgrades. | Single-vendor dependency. [23] | 1. Lifecycle Cost Analysis: Perform a total cost-of-ownership analysis to justify migrating to open standards.2. Phased Migration: Plan a phased replacement of the proprietary system with open-standard components over time. [24] | Managing budget constraints is a key challenge in control engineering. Justifying ROI for new, open-technology investments is crucial for long-term platform sustainability. [21] |

Data Security and Integrity Concerns

Problem: Integrating multiple proprietary systems from different vendors creates a complex network with potential security vulnerabilities and data integrity risks.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Steps | Underlying Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unauthorized access attempts or security alerts. | Inconsistent security patches and weak encryption on proprietary systems. | 1. Network Segmentation: Implement a firewall to isolate the laboratory control network from the corporate network.2. Robust Encryption: Enforce strong encryption for all data in transit between modules. [21] | Cybersecurity is a paramount concern in digital control systems. A breach could compromise intellectual property or alter experimental outcomes, invalidating research. [21] |

| Experimental data inconsistencies. | Lack of unified data management platform. | 1. Centralized Database: Route all data to a central, secure database with a standardized format. [20]2. Audit Logs: Maintain detailed logs of all system access and data transfers for traceability. | The performance of AI models in autonomous labs depends on high-quality, consistent data. Scarcity and noisy data hinder accurate product identification and yield estimation. [2] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a proprietary and an open system in a laboratory context? A: A proprietary system is a closed ecosystem where the hardware, software, and communication protocols are controlled by a single manufacturer. This often leads to vendor lock-in, limiting service options and integration capabilities. [22] [23] An open system uses non-proprietary, industry-standard protocols (e.g., ONVIF, OPC UA), allowing components from different vendors to interoperate seamlessly, offering greater flexibility and long-term cost-efficiency. [24] [23]

Q2: Our proprietary HPLC system uses a closed protocol. How can we get it to send data to our autonomous platform's central AI? A: The most common and practical solution is to use a gateway or middleware. This involves running the vendor's proprietary software on a dedicated computer and then using a second, custom-built software "bridge" to scrape the data from the application's interface or database and forward it to your central AI using a standard API (e.g., REST). This creates a modular workflow that respects the instrument's proprietary nature while enabling integration. [20]

Q3: Are there any success stories of autonomous platforms overcoming proprietary challenges? A: Yes. Recent research has demonstrated a modular robotic workflow where mobile robots transport samples between a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer, a UPLC-MS, and a benchtop NMR spectrometer. The key to its success was using a heuristic decision-maker that processes data from these standard, and sometimes proprietary, instruments by leveraging their vendor software in an automated way, thus bypassing deep integration challenges through a modular approach. [20] [2]

Q4: What are the long-term risks of building an autonomous platform primarily on proprietary systems? A: The primary risks are obsolescence, high lifecycle costs, and inhibited innovation. [22] If the vendor discontinues support, changes their protocol, or fails to innovate, your entire platform's capabilities and security could be compromised. You are entirely dependent on the vendor's roadmap, which may not align with your research needs, forcing expensive and disruptive platform replacements in the future. [22] [23]

Experimental Protocols for Integration and Error Handling

Protocol 1: Establishing a Modular Connection to a Proprietary Instrument

Objective: To enable an autonomous control system to reliably receive data from a proprietary analytical instrument without direct low-level protocol access.

Methodology:

- Setup: Install the instrument's proprietary control and data analysis software on a dedicated Windows PC with a stable connection to the instrument.

- Automation Script: Develop a Python script using libraries like

pyautoguiorseleniumto automate the process of opening data files, exporting results, and managing the instrument's queue from within the vendor's software. - Data Bridge: Create a second service (e.g., a Flask API) that monitors the export directory for new files. This service parses the exported data (e.g., CSV, XML) and republishes it in a standardized JSON format via a REST API endpoint.

- Integration: Configure the central autonomous laboratory manager to call this REST API to retrieve standardized data, effectively decoupling the proprietary instrument from the main workflow.

Thesis Context: This protocol directly addresses the challenge of integrating diverse systems and protocols [21] by creating a hardware-agnostic data layer. It allows for seamless data exchange despite proprietary barriers, which is a prerequisite for adaptive error handling and self-learning in autonomous systems. [20]

Protocol 2: Error Handling for Failed Synthesis Steps in a Closed-Loop Workflow

Objective: To create a decision-making logic that allows an autonomous platform to detect and respond to a failed reaction step.

Methodology:

- Analysis and Detection: Following a reaction, the crude mixture is analyzed by orthogonal techniques (e.g., UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR). [20] A heuristic decision-maker automatically grades the result.

- UPLC-MS Pass/Fail: A pass is assigned if the expected mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) for the product is detected above a predefined intensity threshold.

- NMR Pass/Fail: A pass is assigned if the spectrum shows characteristic chemical shifts for the desired product, using techniques like dynamic time warping to detect changes from the starting material. [20]

- Decision Logic: The results from both analyses are combined. A reaction must pass both UPLC-MS and NMR checks to be considered a success.

- Autonomous Response:

- If Pass: The platform is instructed to proceed to the next synthetic step, which may include scale-up or functional assay. [20]

- If Fail: The platform is instructed to either (a) attempt a one-time re-synthesis of the failed step to check for reproducibility or (b) discard the failed reaction and proceed with the next candidate in the library to conserve resources.

Thesis Context: This protocol embodies the core of error handling and robustness to mispredictions in autonomous research. It moves beyond simple automation by enabling the platform to cope with mispredictions and unforeseen outcomes, a key step toward true autonomy and continuous learning. [20] [2]

Workflow Visualization

Autonomous Synthesis Error Handling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Solution | Function in Autonomous Synthesis | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Hardware | Chemspeed ISynth / Chemputer |

Automated synthesis platform for executing reactions in batch manner; modularizes physical operations like transferring, heating, and stirring. [3] [20] | Enables reproducible, hands-off synthesis according to a chemical programming language. [3] |

| Analytical Instruments | UPLC-MS & Benchtop NMR | Provides orthogonal data (molecular weight & structure) for robust product identification and reaction monitoring. [20] | Heuristic decision-makers combine data from both for a pass/fail grade, mimicking expert judgment. [20] |

| Robotics & Mobility | Mobile Robot Agents | Free-roaming robots transport samples between synthesis and analysis modules, enabling a modular, scalable lab layout. [20] | Allows sharing of standard, unmodified lab equipment between automated workflows and human researchers. [20] |

| Software & AI | Heuristic Decision Maker | Algorithm that processes analytical data against expert-defined rules to autonomously decide the next experimental step. [20] | Critical for transitioning from mere automation to true autonomy and exploratory synthesis. [20] |

| Software & AI | LLM-based Agents (e.g., Coscientist) | Acts as an AI "brain" for the lab, capable of planning synthetic routes, writing code, and controlling robotic systems. [2] | Demonstrates potential for on-demand autonomous chemical research, though can be prone to hallucinations. [2] |

| Isorhamnetin 3-O-galactoside | Isorhamnetin 3-O-galactoside, MF:C22H22O12, MW:478.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,6-Difluorobenzamide-d3 | 2,6-Difluorobenzamide-d3, MF:C7H5F2NO, MW:160.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an automated lab and an autonomous one? An automated lab follows pre-defined scripts and procedures to execute experiments without human intervention. In contrast, an autonomous lab incorporates a closed-loop cycle where artificial intelligence (AI) not only executes experiments but also plans them, analyzes the resulting data, and uses that analysis to decide what experiments to run next, thereby learning and improving over time with minimal human input [2].

Q2: Our autonomous synthesis platform frequently gets stuck in unproductive loops, repeatedly running similar failed experiments. What could be the cause? This is a recognized failure mode, often described as a "cognitive deadlock" or "unproductive iterative loop" [25]. The root cause is typically flawed reasoning within the AI's decision-making process, where it lacks the strategic oversight to change its approach after initial failures. This can be mitigated by implementing a collaborative agent architecture where a supervisory "Expert" agent reviews and corrects the plan of a primary "Executor" agent [25].

Q3: Why does my flow chemistry platform keep clogging, and how can this be prevented? Clogging is a common hardware failure in flow chemistry platforms [3]. Prevention requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Detection: Implement sensors to detect pressure changes that indicate a clog has occurred.

- Recovery: Engineer a means for the system to automatically pause and execute a cleaning or unclogging procedure.

- Robust Hardware: Consider platforms that use disposable reaction vessels (like vial-based systems) for complex reactions where clogs are frequent, as these can simply be discarded upon failure [3].

Q4: Our AI model proposes syntheses that are chemically plausible but fail in the lab. How can we improve the success rate? This is a key challenge, as AI models trained on published literature may lack the subtle, practical details required for successful experimental execution [3]. To improve:

- Data Curation: Supplement training data with high-quality, internally generated data that includes detailed procedural notes.

- Initial Guessing & Optimization: Use the AI's prediction as an initial guess and integrate empirical optimization techniques, like Bayesian optimization, to refine the reaction conditions [3].

- Uncertainty Indication: Prefer AI models that can indicate their level of certainty, helping researchers identify high-risk proposals [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Responding to Synthesis Failures

Synthesis failures can be categorized by their manifestation. The table below outlines common failure types, their diagnostic signals, and recommended corrective actions.

Table 1: Synthesis Failure Diagnosis Guide

| Failure Manifestation | Primary Diagnostic Signals | Recommended Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Convergence (Failure to find optimal conditions) | Repeated, similar experiments with no improvement in yield or selectivity [25]. | 1. Halt the experimental loop [25]. 2. Review and adjust the AI's optimization algorithm parameters [3]. 3. Manually verify the analytical data quality. |

| Complete Reaction Failure (No desired product detected) | LC/MS or NMR analysis shows no trace of the target molecule [3]. | 1. Verify reagent integrity and inventory levels [3]. 2. Check the proposed reaction pathway for known incompatibilities. 3. Confirm the accuracy of the synthesis planner's output. |

| System Crash / Hardware Fault (e.g., Clogging, Robot Error) | Pressure alarms in flow systems; robotic arm position errors; failure to complete a physical task [3]. | 1. Execute automated emergency stop and recovery protocols [3]. 2. Inspect and clear clogged lines or reset robotic components. 3. For vial-based systems, discard the failed reaction vessel. |

Guide 2: Resolving Issues in AI-Driven Synthesis Planning

This guide addresses failures originating from the software planning stage of autonomous synthesis.

Table 2: Synthesis Planning Failure Guide

| Planning Issue | Root Cause | Resolution Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Problem Localization | The AI agent fails to correctly identify the root cause of a problem in a complex codebase or synthetic pathway [25]. | Implement a collaborative framework where a second "Expert" agent audits the primary agent's diagnostic steps to correct flawed reasoning [25]. |

| Evasive or Incomplete Repair | The agent proposes a patch or synthetic route that only partially addresses the issue or avoids the core problem [25]. | Enhance validation steps to require the agent to explain how its solution directly resolves the issue described. |

| Generation of Incorrect Chemical Information | The LLM "hallucinates," producing plausible but chemically impossible reactions or conditions [2]. | Integrate fact-checking tools that cross-reference proposals against known chemical databases and rule-based systems [2]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Closed-Loop Optimization of Reaction Conditions

This is a standard methodology for autonomous optimization, leveraging a cycle of planning, execution, and analysis [2].

- Initial Proposal: The AI model (e.g., one using Bayesian optimization) proposes an initial set of reaction conditions based on prior data [3].

- Robotic Execution: A robotic system automatically dispenses reagents, sets up the reaction vessel (e.g., a microwave vial), and controls temperature and stirring [3] [2].

- Product Analysis: An automated system (e.g., UPLC-MS) quenches the reaction, samples the mixture, and analyzes the product for yield and purity [3] [2].

- Data Interpretation: Machine learning models interpret the analytical data (e.g., LC-MS chromatograms) to quantify results [2].

- Iterative Planning: The AI uses the results to update its model and propose the next most informative set of conditions to test, returning to Step 2 [3] [2].

Protocol 2: Multi-Step Target-Oriented Synthesis

This protocol outlines the workflow for autonomously synthesizing a complex target molecule over multiple steps [3].

- Retrosynthesis Planning: A data-driven AI tool (e.g., template-based neural models) performs retrosynthesis to break the target down into available building blocks [3].

- Route Scoring & Selection: Proposed routes are ranked based on feasibility, predicted yield, and compatibility with the platform's hardware (e.g., avoiding solid-forming intermediates in flow systems) [3].

- Translation to Actions: The selected route is translated into a hardware-agnostic chemical description language (e.g., XDL), which is then converted into machine commands [3].

- Execution & Isolation: The robotic platform executes the first synthetic step, followed by an automated work-up (e.g., liquid-liquid extraction) and purification (e.g., catch-and-release chromatography) if required [3].

- Intermediate Analysis: The isolated intermediate is analyzed (e.g., via LC-MS or benchtop NMR) to confirm identity and purity before proceeding [3] [2].

- Iteration: Steps 4 and 5 are repeated for each subsequent step in the synthetic route [3].

Workflow Diagrams

DOT Visualization Code

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key components and materials essential for building and operating an autonomous synthesis platform.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Synthesis Platforms

| Item / Component | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chemical Inventory Management System | A centralized, often automated, storage system for building blocks and reagents. It is critical for ensuring the platform has uninterrupted access to a diverse range of chemicals, enabling the synthesis of novel structures [3]. |

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates the precise transfer of liquid reagents, a fundamental physical operation that replaces manual pipetting and increases reproducibility [3] [2]. |

| Modular Reaction Vessels | Standardized vials (e.g., microwave vials) or flow reactors where chemical transformations occur. Modularity allows the platform to be adapted for different reaction types and scales [3]. |

| Computer-Controller Heater/Shaker | Provides precise and programmable control over reaction temperature and mixing, which are critical parameters for successful synthesis [3]. |

| Ultraperformance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS) | The primary workhorse for automated analysis. It separates reaction components (chromatography) and identifies the product based on its mass, providing rapid feedback on reaction outcome [3] [2]. |

| Benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer | Used for more definitive structural elucidation of synthesized compounds, especially when MS data is ambiguous. Its integration into automated workflows is a key advancement [3] [2]. |

| Corona Aerosol Detector (CAD) | A detector for liquid chromatography that promises to enable universal calibration curves, allowing for quantitative yield estimation without a product-specific standard [3]. |

| Flunisolide Acetate-D6 | Flunisolide Acetate-D6, MF:C26H33FO7, MW:482.6 g/mol |

| Histone H3 (116-136), C116-136 | Histone H3 (116-136), C116-136, MF:C107H195N39O28S, MW:2508.0 g/mol |

Error Handling Architectures: Implementing Resilient Autonomous Workflows

In autonomous synthesis platforms, where experiments must proceed reliably without constant human oversight, robust error diagnosis is paramount. The orchestrator-worker pattern provides a structured framework for building such resilient systems. This pattern employs a central orchestrator agent that manages task delegation and coordinates multiple specialized worker agents to diagnose and resolve errors [26] [27].

The core strength of this architecture lies in its specialization and centralized coordination. Individual worker agents can focus on specific diagnostic domains—such as sensor validation, data anomaly detection, or process integrity checks—while the orchestrator maintains a holistic view of the system's health and diagnostic process [26]. This separation of concerns is particularly valuable in complex research environments like pharmaceutical labs or autonomous driving systems, where errors can propagate through multiple subsystems if not promptly identified and contained [28] [29].

When implementing this pattern for error diagnosis, the system transforms fault management from a monolithic process into a coordinated, multi-agent collaboration. The orchestrator assesses incoming error signals, determines the required diagnostic expertise, dispatches tasks to relevant worker agents, synthesizes their findings, and determines appropriate corrective actions [26] [30]. This approach enables comprehensive fault coverage that would be difficult to achieve with a single diagnostic agent, especially as system complexity increases.

Core Architecture & Implementation

Fundamental Components and Data Flow

The orchestrator-worker pattern for error diagnosis consists of several key components that work together to identify, analyze, and resolve system faults:

Orchestrator Agent: Serves as the central coordination unit that receives initial error notifications, determines the diagnostic workflow, dispatches tasks to worker agents, and makes final decisions based on aggregated findings [26] [27]. The orchestrator maintains a global view of system health and diagnostic progress.

Specialized Worker Agents: Domain-specific diagnostic units that possess expertise in particular subsystems or error types [26]. In an autonomous synthesis platform, these might include sensor validation agents, process compliance agents, data integrity agents, and equipment malfunction agents.

Communication Infrastructure: The messaging framework that enables coordination between the orchestrator and workers [31] [27]. Event-driven architectures using technologies like Apache Kafka have proven effective for this purpose, allowing agents to communicate through structured events while maintaining loose coupling [27].

Shared Knowledge Base: A centralized repository where diagnostic findings, system status information, and resolution actions are recorded [27]. This serves as an institutional memory for the diagnostic system, enabling learning from previous error incidents.

The typical diagnostic workflow follows a structured sequence: (1) Error detection or notification, (2) Orchestrator assessment and task decomposition, (3) Parallel agent execution on specialized diagnostic tasks, (4) Result aggregation and analysis by the orchestrator, and (5) Corrective action determination and execution [26].

Technical Implementation Guide

Implementing an effective orchestrator-worker system for error diagnosis requires careful attention to several technical considerations:

Agent Communication Protocols: Standardized communication protocols are essential for reliable agent interaction. Message passing between orchestrator and workers should follow a consistent schema that includes message type, priority, source/destination identifiers, timestamp, and structured payload data [31] [27]. In event-driven implementations, agents consume and produce events to dedicated topics, allowing for asynchronous processing and natural decoupling of system components [27].

Error Classification and Routing: The orchestrator must employ a precise error classification scheme to route diagnostic tasks effectively. A robust classification system might categorize errors by subsystem (sensor, actuator, computation, communication), severity (critical, warning, informational), or temporal pattern (transient, intermittent, persistent) [29]. This classification directly determines which specialized worker agents are activated for diagnosis.

State Management and Recovery: Maintaining diagnostic state across potentially long-running investigations is crucial. The orchestrator should track the progress of each worker agent, manage timeouts for diagnostic operations, and implement checkpointing for complex multi-stage diagnostics [27]. In case of agent failures, the system should be able to reassign diagnostic tasks or continue with degraded functionality.

Implementation Example with Apache Kafka: The orchestrator-worker pattern can be effectively implemented using Apache Kafka for communication [27]. The orchestrator publishes command messages with specific keys to partitions in a "diagnostic-tasks" topic. Worker agents form a consumer group that pulls events from their assigned partitions. Workers then send their diagnostic results to a "findings-aggregation" topic where the orchestrator consumes them to synthesize a complete diagnostic picture. This approach provides inherent scalability and fault tolerance through Kafka's consumer group rebalancing and offset management capabilities [27].

Performance Metrics & Experimental Validation

Quantitative Performance Data

Research and real-world implementations demonstrate the significant performance advantages of multi-agent orchestrator-worker systems for error diagnosis compared to monolithic approaches.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Multi-Agent Diagnostic Systems Across Industries

| Industry Application | Key Performance Improvement | Measurement Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Services | Fraud detection accuracy improved from 87% to 96% | 12 specialized agents working in coordination | [31] |

| Manufacturing | Equipment downtime reduced by 42% | Predictive maintenance across 47 facilities | [31] |

| Customer Service | Resolution time decreased by 58% | 8 specialized agents handling diverse query types | [31] |

| AI Research | Performance improvement of 90.2% on research tasks | Multi-agent vs. single-agent evaluation | [30] |

| Clinical Genomics | Manual error risk reduced by 88% | Automated sample preparation workflow | [32] |

Table 2: Resource Utilization Patterns in Multi-Agent Diagnostic Systems

| Resource Metric | Single-Agent System | Multi-Agent System | Impact on Diagnostic Operations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Token Usage (AI context) | Baseline | 15x higher | Enables more thorough parallel investigation but increases computational costs | [30] |

| Implementation Timeline | 3-6 months | 6-18 months | Greater initial investment for long-term diagnostic robustness | [31] |

| Initial Implementation Cost | $100K-$1M | $500K-$5M | Higher upfront cost for distributed diagnostic capability | [31] |

| Optimal Agent Count | 1 | 5-25 specialized agents | Balance between comprehensive coverage and coordination complexity | [31] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Researchers evaluating orchestrator-worker systems for error diagnosis should employ rigorous experimental protocols to measure system effectiveness:

Diagnostic Accuracy Assessment:

- Objective: Quantify the system's ability to correctly identify, classify, and resolve errors compared to baseline approaches.

- Methodology: Inject controlled faults into the target system (e.g., sensor miscalibration, data anomalies, process deviations) and measure detection time, classification accuracy, and resolution effectiveness [28] [29].

- Metrics: Calculate precision, recall, and F1-score for error classification; measure mean time to detection (MTTD) and mean time to resolution (MTTR); quantify false positive and false negative rates [28].

Scalability and Load Testing:

- Objective: Evaluate system performance under increasing diagnostic workloads and agent counts.

- Methodology: Gradually increase the rate of injected faults or system complexity while monitoring coordination overhead, communication latency, and resource utilization [31].

- Metrics: Measure throughput (diagnoses per unit time), latency from error occurrence to diagnosis, and resource consumption scaling curves [30] [31].

Fault Tolerance and Resilience Evaluation:

- Objective: Assess system robustness when individual agents fail or produce unreliable outputs.

- Methodology: Randomly disable worker agents during diagnostic operations or introduce noisy/malformed data to specific agents [33].

- Metrics: Quantize task completion rates with partial agent failure, measure recovery time from agent failures, and assess error propagation containment [33] [29].

Cross-Domain Adaptability Assessment:

- Objective: Evaluate the system's ability to handle diverse error types across different domains.

- Methodology: Deploy the same architectural pattern to diagnose errors in different contexts (e.g., autonomous vehicles, laboratory automation, manufacturing) with domain-specific worker agents [28] [34] [32].

- Metrics: Compare performance preservation across domains, implementation effort for new domains, and reusable component percentages [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Orchestrator-Worker Implementation Issues

| Problem | Symptoms | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Scalability | Increasing latency with more agents; duplicated diagnostic efforts | Inefficient communication patterns; lack of proper workload distribution | Implement event-driven communication [27]; use key-based partitioning for workload distribution [27] |

| Agent Coordination Failures | Diagnostic tasks remain unassigned; conflicting diagnoses from different agents | Insufficient fault tolerance in orchestrator; unclear agent boundaries | Implement consumer group patterns for automatic rebalancing [27]; define precise agent responsibilities with clear domains [26] [30] |

| Resource Overconsumption | High computational costs; slow diagnostic throughput | Inefficient agent initialization; excessive inter-agent communication | Implement agent pooling; optimize token usage in AI agents [30]; scale agent effort to query complexity [30] |

| Diagnostic Gaps or Overlaps | Some error types not diagnosed; multiple agents handling same error | Incomplete error classification; imprecise task routing logic | Develop comprehensive error taxonomy [29]; implement precise error classification and routing rules [26] |

| Integration Challenges | Failure to diagnose errors in legacy systems; inconsistent data formats | Lack of adapters for legacy systems; incompatible data schemas | Develop specialized connector agents; implement data normalization layer; use standardized messaging formats [31] [27] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How many worker agents are typically optimal for a diagnostic system in autonomous synthesis platforms? A: Most successful implementations use between 5 and 25 specialized agents, with the optimal number depending on system complexity and diagnostic requirements. Smaller systems might function effectively with 5-10 agents covering major subsystems, while complex autonomous research platforms might require 15-25 agents for comprehensive coverage [31].

Q: What are the primary factors that impact the performance of multi-agent diagnostic systems? A: Research indicates that three factors explain approximately 95% of performance variance: token usage (explains 80% of variance), number of tool calls, and model choice [30]. Effective systems carefully balance these factors to maximize diagnostic accuracy while managing computational costs.

Q: How do orchestrator-worker systems handle conflicts when different agents provide contradictory diagnoses? A: The orchestrator agent typically implements conflict resolution mechanisms such as confidence-weighted voting, consensus algorithms, or additional verification workflows [26] [31]. In critical systems, the orchestrator may initiate a secondary diagnostic process with expanded agent participation to resolve contradictions [26].

Q: What communication patterns work best for time-sensitive diagnostic scenarios? A: Event-driven architectures with parallel processing capabilities provide the best performance for time-sensitive diagnostics. Research shows that parallel tool calling and parallel agent activation can reduce diagnostic time by up to 90% compared to sequential approaches [30].

Q: How can we ensure the diagnostic system itself is fault-tolerant? A: Implement health monitoring for all agents, automatic restart mechanisms for failed components, and fallback strategies when agents become unresponsive [27]. The system should maintain diagnostic capability even with partial agent failure, potentially with degraded performance or reduced coverage [33] [29].

Essential Tools and Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Components for Multi-Agent Diagnostic System Implementation

| Component | Function | Example Tools/Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Agent Framework | Provides foundation for creating, managing, and executing agents | Azure AI Agents, Anthropic's Agent SDK, AutoGen, LangGraph |

| Communication Backbone | Enables reliable messaging between orchestrator and worker agents | Apache Kafka, Redis Pub/Sub, RabbitMQ, NATS [27] |

| Monitoring & Observability | Tracks system performance, agent health, and diagnostic effectiveness | Prometheus, Grafana, ELK Stack, Azure Monitor |

| Knowledge Management | Stores diagnostic history, error patterns, and resolution strategies | Vector databases, SQL/NoSQL databases, Graph databases |

| Model Serving Infrastructure | Hosts and serves AI models used by diagnostic agents | TensorFlow Serving, Triton Inference Server, vLLM |

| Workflow Orchestration | Manages complex diagnostic workflows and dependencies | Apache Airflow, Prefect, Temporal, Dagster |

System Architecture Visualization

Diagram 1: Event-Driven Orchestrator-Worker Architecture for Error Diagnosis

Diagram 2: Error Diagnosis Workflow with Parallel Agent Execution

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Liquid Handling Robot Dispensing Inaccurate Volumes

Q: During a high-throughput screening assay, my automated liquid handler consistently dispenses volumes 15% lower than specified for a critical reagent. What could be the cause and solution?

A:

- Root Cause: Primary causes include a partially clogged or wet tip, degradation of the syringe plunger seal, or incorrect liquid class parameters for the reagent's viscosity.

- Impact: This systematic error invalidates dose-response data, leading to incorrect IC50 calculations.

- LLM-Driven Solution: An LLM module integrated with the platform's log files can correlate the error with specific reagent properties and instrument flags. It will:

- Parse error logs for

"aspiration pressure outlier"events. - Cross-reference the reagent with a database to suggest a modified

"liquid class"with slower aspiration speed. - Generate a protocol for executing a

"tip integrity check"and"syringe seal replacement"workflow.

- Parse error logs for

- Supporting Research: A 2024 study on autonomous platforms found that >70% of volumetric errors were traceable to mismatched liquid classes.

FAQ 2: Unpredicted "No Reaction" Outcome in Automated Synthesis

Q: My autonomous synthesis platform executed a validated Suzuki-Miyaura coupling protocol, but NMR shows only starting materials. The platform reported all steps as "successful." How do I diagnose this?

A:

- Root Cause: Likely failure in solid reagent addition (e.g., catalyst Pd(PPh3)4 clumping, improper vial piercing) or an inert atmosphere breach during a critical step.

- Impact: Complete waste of resources and time for a multi-step synthesis.

- LLM-Driven Solution: The LLM analyzes the sensor timeline (weight, pressure, temperature) versus the protocol:

- Identifies a discrepancy between

"command: dispense solid"and"weight sensor delta: 0mg". - Flags the event as a