Functional Groups in Modern Drug Discovery: From Chemical Foundations to AI-Driven Prediction

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of functional groups and their pivotal role in determining molecular properties and biological activity, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Functional Groups in Modern Drug Discovery: From Chemical Foundations to AI-Driven Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of functional groups and their pivotal role in determining molecular properties and biological activity, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the fundamental chemical principles of common functional groups and their reactivity. The scope then systematically progresses to cover the application of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and modern machine learning tools for property prediction. The article further addresses critical challenges such as experimental data bias and activity cliffs, offering optimization strategies. Finally, it evaluates advanced AI frameworks and validation methodologies essential for robust predictive modeling, synthesizing classical knowledge with cutting-edge computational techniques to accelerate rational drug design.

The Chemical Language of Life: Defining Functional Groups and Their Fundamental Properties

Systematic Classification of Key Functional Groups in Organic Chemistry

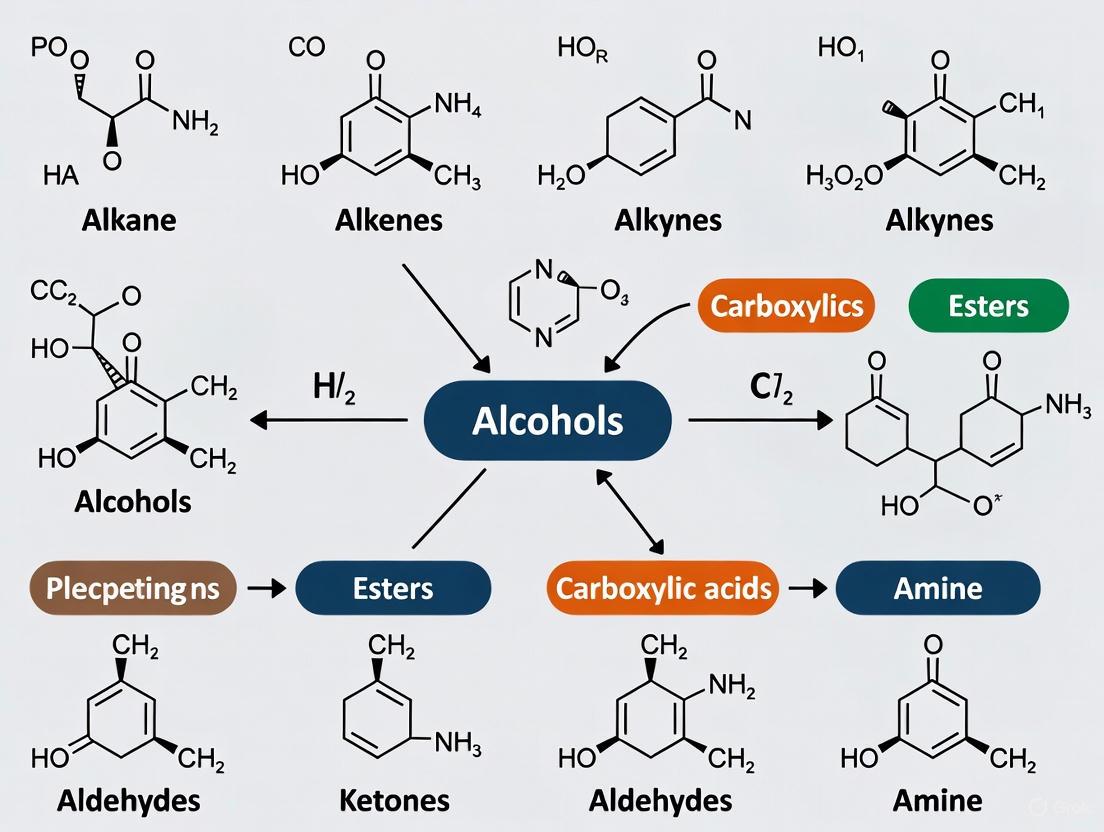

In organic chemistry, functional groups are specific groupings of atoms within molecules that have their own characteristic properties, regardless of the other atoms present in the molecule [1]. These structural motifs are fundamental to understanding organic compound behavior, as they largely determine the chemical properties and reactivity patterns of the molecules that contain them [2]. The systematic classification of these groups provides researchers with a predictive framework for understanding structure-activity relationships, which is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development and materials science where molecular behavior must be precisely engineered.

The concept of functional groups represents a cornerstone of chemical research, enabling scientists to categorize organic compounds based on their reactive characteristics rather than their complete molecular structure. This classification system allows for extrapolation of chemical behavior across diverse molecular scaffolds, facilitating the rational design of novel compounds with desired properties. As molecular property prediction becomes increasingly important in drug and materials discovery, functional group analysis provides an interpretable framework that bridges computational models and chemical intuition [3].

Systematic Classification of Major Functional Groups

Hydrocarbon-Based Functional Groups

Hydrocarbon functional groups form the foundational carbon skeletons of organic molecules and are characterized by their non-polar nature and relatively low reactivity compared to heteroatom-containing groups [1].

Table 1: Classification of Hydrocarbon Functional Groups

| Functional Group | General Structure | Key Characteristics | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkane | C-C single bonds | sp³ hybridized carbons, tetrahedral geometry, very non-polar | Methane, Ethane, Propane [1] |

| Alkene | C=C double bond | sp² hybridized, trigonal planar geometry, more reactive than alkanes | Ethene, Propene, Butene [1] [2] |

| Alkyne | C≡C triple bond | sp hybridized, linear geometry | Ethyne (acetylene) [1] [2] |

| Aromatic | Benzene ring | sp² hybridized, delocalized π-electrons, unusual stability | Benzene, Toluene, Xylene [1] |

Heteroatom-Containing Functional Groups

The introduction of heteroatoms (oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, halogens) dramatically alters the physical and chemical properties of organic molecules, increasing polarity and providing sites for specific chemical interactions.

Table 2: Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups

| Functional Group | General Structure | Key Characteristics | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | R-OH | Polar O-H bond, hydrogen bonding capability, increased water solubility | Methanol, Isopropanol [1] |

| Ether | R-O-R | Oxygen flanked by two carbon atoms, cannot hydrogen bond | Diethyl ether, Tetrahydrofuran [1] |

| Aldehyde | RCHO | Carbonyl bonded to carbon and hydrogen, polar C=O bond | Formaldehyde, Acetaldehyde, Benzaldehyde [1] |

| Ketone | RC(O)R | Carbonyl bonded to two carbons | Acetone (2-propanone) [1] |

| Carboxylic Acid | RCOOH | Carbonyl bonded to -OH, hydrogen bonding, acidic properties | Acetic acid, Formic acid [1] |

| Ester | RCOOR | Similar to carboxylic acids but with O-C bond instead of O-H | Various esters with sweet smells [1] |

Table 3: Nitrogen, Halogen, and Sulfur-Containing Functional Groups

| Functional Group | General Structure | Key Characteristics | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amine | -NHâ‚‚, -NHR, or -NRâ‚‚ | Capable of hydrogen bonding, basic properties | Morphine, Codeine, Cocaine [1] |

| Amide | Carbonyl attached to amino group | Participate in hydrogen bonding, form peptides | Proteins, peptides [1] |

| Alkyl Halide | R-F, R-Cl, R-Br, R-I | Dipole-dipole interactions, important in substitution reactions | Chloroform, Bromobutane [1] |

| Nitrile | -CN | Sometimes called cyanide, can be converted to amides | Acetonitrile, Nitrile rubber [1] |

| Thiol | R-SH | Sulfur analogs of alcohols, strong odors | Ethanethiol (added to natural gas) [1] |

| Nitro | -NOâ‚‚ | Strongly electron-withdrawing | Nitromethane [1] |

Analytical Methodologies for Functional Group Characterization

Classical Qualitative Analysis

Traditional chemical tests provide rapid identification of functional groups through characteristic color changes, precipitate formation, or gas evolution [4].

Silver Nitrate Test for Alkyl Halides and Carboxylic Acids: Place 20 drops of 0.1 M AgNO₃ in 95% ethanol in a clean, dry test tube. Add one drop of sample and mix thoroughly. Observe for formation of white or yellow precipitate within five minutes at room temperature. If no reaction occurs, warm the mixture in a beaker of boiling water and observe changes. If precipitate forms, add several drops of 1 M HNO₃ and note any dissolution of precipitate [4].

Chromic Acid Test for Alcohols and Aldehydes: This test distinguishes oxidizing alcohols and aldehydes from other functional groups through color change from orange to green or blue, indicating oxidation [4].

Solubility Tests: Determination of solubility characteristics in water, 5% NaOH, and 5% HCl provides preliminary classification of functional groups. Carboxylic acids are typically soluble in basic solutions, while amines are soluble in acidic solutions [4].

Instrumental Analysis Techniques

Modern analytical instrumentation provides precise identification and quantification of functional groups in complex molecules.

Table 4: Instrumental Methods for Functional Group Analysis

| Method | Principle | Application in Functional Group Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Absorption of IR radiation by vibrating bonds | Identification of characteristic functional group vibrations (e.g., C=O stretch at 1725-1700 cmâ»Â¹, O-H stretch at 3200-3600 cmâ»Â¹) [5] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei | Determination of functional group environment through chemical shifts (e.g., ¹³C NMR for OMe group at δC ≈ 55.6 ppm) [5] |

| Ultraviolet-Visible Spectrophotometry | Absorption of UV-Vis light by conjugated systems | Detection of conjugated unsaturated bonds or aromatic rings [5] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Ion separation by mass-to-charge ratio | Structural elucidation through fragmentation patterns characteristic of functional groups [5] |

| Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | Separation followed by mass detection | Comprehensive analysis of complex mixtures containing diverse functional groups [5] |

Quantitative Analysis of Functional Groups

Quantitative determination of functional groups serves two primary purposes: determining the percentage content of a component in a sample, and verifying the structure of a compound by determining the percentage and number of characteristic functional groups in the molecule [5].

Chemical Methods include acid-base titration, redox titration, precipitation titration, moisture determination, gas measurement, and colorimetric analysis. These methods measure reagent consumption or product formation from characteristic chemical reactions of functional groups [5].

Statistical Estimation Approaches have been developed for compounds lacking authentic standards. These methods use predictive equations based on linear regression analysis between actual response factors of reference compounds and their physicochemical parameters, such as carbon number, molecular weight, and boiling point [6].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Group Analysis

Systematic Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for systematic functional group identification in unknown organic compounds:

Detailed Solubility Testing Protocol

Solubility in Water:

- Into a small test tube, place 5 drops of known sample (or pea-sized solid sample).

- Add 10 drops of laboratory water and mix thoroughly by flicking the bottom of the test tube.

- Determine if the sample dissolves (formation of a second layer indicates insolubility).

- If soluble, test acidity or basicity using litmus paper (blue to red indicates acidic; red to blue indicates basic) [4].

Solubility in 5% NaOH:

- Into a small test tube, place 5 drops of known sample (or pea-sized solid sample).

- Add 10 drops of 5% NaOH and mix thoroughly.

- Record observations, noting dissolution of acidic compounds [4].

Solubility in 5% HCl:

- Into a small test tube, place 5 drops of known sample (or pea-sized solid sample).

- Add 10 drops of 5% HCl and mix thoroughly.

- Record observations, noting dissolution of basic compounds such as amines [4].

Advanced Research Applications

Functional Group Representation in Molecular Property Prediction

Recent advances in molecular property prediction have incorporated functional group analysis into machine learning frameworks. The Functional Group Representation (FGR) framework encodes molecules based on their fundamental chemical substructures, integrating two types of functional groups: those curated from established chemical knowledge, and those mined from large molecular databases using sequential pattern mining algorithms [3].

This approach achieves state-of-the-art performance on diverse benchmark datasets spanning physical chemistry, biophysics, quantum mechanics, biological activity, and pharmacokinetics while maintaining chemical interpretability. The model's representations are intrinsically aligned with established chemical principles, allowing researchers to directly link predicted properties to specific functional groups [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Group Analysis

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Group Analysis

| Reagent | Function | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 M AgNO₃ in 95% ethanol | Precipitation reagent | Detection of alkyl halides and carboxylic acids through precipitate formation [4] |

| 5% NaOH solution | Basic solubility test | Identification of acidic functional groups (carboxylic acids, phenols) through dissolution [4] |

| 5% HCl solution | Acidic solubility test | Identification of basic functional groups (amines) through dissolution [4] |

| Chromic acid solution | Oxidation test | Distinguishing alcohols and aldehydes through color change [4] |

| Bromine in CClâ‚„ | Unsaturation test | Detection of alkenes and alkynes through decolorization [5] |

| Potassium permanganate | Oxidation test | Identification of unsaturated compounds through color change [5] |

| Ferric chloride solution | Phenol detection | Formation of colored complexes with phenolic compounds [5] |

| Hydroxylamine hydrochloride | Carbonyl detection | Formation of hydroxamates with aldehydes and ketones [5] |

The systematic classification of functional groups provides an essential framework for understanding, predicting, and manipulating the chemical behavior of organic compounds. From fundamental solubility characteristics to sophisticated spectroscopic signatures, functional groups serve as the fundamental units determining molecular properties and reactivity. The integration of traditional chemical analysis with modern computational approaches, such as the Functional Group Representation framework, continues to advance our ability to correlate structural features with chemical behavior, particularly in pharmaceutical research and materials science. As analytical technologies evolve, the precise identification and quantification of functional groups will remain cornerstone methodologies in chemical research, enabling continued innovation in molecular design and synthesis.

The reactivity of a molecule—its propensity to undergo chemical transformation—is not an emergent property but rather a direct consequence of its fundamental structural features and electronic properties. At the most essential level, the spatial arrangement of atoms and the distribution of electrons within a molecule create regions of high and low electron density that dictate interaction patterns with other chemical species. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding these fundamental relationships provides predictive power in designing compounds with specific biological activities or material characteristics. The integration of computational methods with experimental structural biology has revolutionized our ability to probe these relationships, allowing for the expansion of structural interpretation through detailed models [7].

This technical guide examines the quantitative relationship between atomic structure, electronic properties, and chemical reactivity, with particular emphasis on approaches relevant to pharmaceutical research. We explore how computational frameworks built upon density functional theory (DFT), molecular orbital theory, and quantitative structure-reactivity relationships (QSRRs) enable researchers to predict reactivity parameters and understand interaction mechanisms without exhaustive experimental investigation. For drug development professionals, these approaches offer efficient pathways to assess potential drug candidates, understand their mechanism of action, and optimize their therapeutic properties through targeted structural modifications.

Theoretical Foundations: Electronic Properties Dictating Reactivity

Frontier Molecular Orbitals and Global Reactivity Descriptors

The frontier molecular orbital theory represents a cornerstone in understanding chemical reactivity. The Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) energies define critical electronic parameters that govern molecular stability and reactivity. The energy gap between HOMO and LUMO orbitals (ΔE) serves as a fundamental indicator of chemical stability, kinetic stability, and chemical reactivity patterns [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Electronic Parameters and Their Chemical Significance

| Parameter | Definition | Chemical Significance | Computational Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO Energy | Energy of highest occupied molecular orbital | Characterizes electron-donating ability (nucleophilicity) | DFT calculation of molecular orbitals |

| LUMO Energy | Energy of lowest unoccupied molecular orbital | Characterizes electron-accepting ability (electrophilicity) | DFT calculation of molecular orbitals |

| Band Gap (ΔE) | Energy difference between HOMO and LUMO | Large gap indicates high stability, low reactivity; small gap indicates high reactivity, low stability | ΔE = ELUMO - EHOMO |

| Ionization Potential | Energy required to remove an electron | IP ≈ -E_HOMO (Koopmans' theorem) | DFT calculation |

| Electron Affinity | Energy change when adding an electron | EA ≈ -E_LUMO (Koopmans' theorem) | DFT calculation |

| Global Hardness (η) | Resistance to electron charge transfer | η = (ELUMO - EHOMO)/2 | Calculated from HOMO-LUMO energies |

| Chemical Potential (μ) | Negative of electronegativity | μ = (EHOMO + ELUMO)/2 | Calculated from HOMO-LUMO energies |

| Electrophilicity Index (ω) | Measure of electrophilic power | ω = μ²/2η | Composite parameter from HOMO-LUMO |

For the compound 3-(2-furyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid, DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level revealed HOMO and LUMO energies of -5.907 eV and -1.449 eV respectively, yielding a band gap of 4.458 eV [8]. This relatively large energy gap indicates high electronic stability and low chemical reactivity, suggesting the compound would exhibit low kinetic reactivity under standard conditions. The spatial distribution analysis showed the HOMO localized primarily on the pyrazole ring nitrogen atoms (N1 and N2) and the C4-C5 double bond, identifying these as nucleophilic centers. Conversely, the LUMO was predominantly distributed over the furan ring and carbonyl group, marking these regions as electrophilic centers [8].

Local Reactivity Descriptors and Molecular Electrostatic Potential

While global descriptors provide overall reactivity trends, local reactivity descriptors identify specific atomic sites prone to nucleophilic or electrophilic attack. The Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) map provides a visual representation of the electrostatic potential created by the electron distribution and atomic nuclei, enabling identification of electron-rich (negative regions, often colored red) and electron-deficient (positive regions, often colored blue) areas [9] [8].

Table 2: Local Reactivity Descriptors and Applications

| Descriptor | Definition | Application in Reactivity Prediction | Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Electrostatic Potential | Electrostatic potential at each point in space around molecule | Identifies nucleophilic/electrophilic attack sites; predicts non-covalent interactions | Correlates with hydrogen bonding, halogen bonding, reaction regioselectivity |

| Fukui Function | Response of electron density to change in electron number | Identifies sites for nucleophilic/electrophilic/radical attack | Predicts regioselectivity in substitution reactions |

| Atomic Partial Charges | Electron distribution among atoms | Identifies charge distribution; predicts ionic interactions | Correlates with NMR chemical shifts, infrared intensities |

| Conceptual DFT Reactivity Indices | Various parameters from density functional theory | Predicts acid-base behavior, redox properties, reaction mechanisms | Correlates with pKa, reduction potentials, reaction rates |

In the study of a novel purine derivative, 2-amino-6‑chloro-N,N-diphenyl-7H-purine-7-carboxamide, MEP analysis combined with quantum mechanics calculations revealed the nature of C—Cl···π interactions as lone-pair⋯π (n→π*) interactions rather than σ-hole interactions [9]. This detailed understanding of non-covalent interactions contributes significantly to the stability of halogenated organic compounds and supramolecular assemblies, with important implications for biomolecular recognition in drug design.

Quantitative Structure-Reactivity Relationships

Foundations of QSRR Methodology

Quantitative Structure-Reactivity Relationships establish mathematical correlations between structural descriptors and experimentally measured reactivity parameters. For organic synthesis planning, Mayr's approach to quantifying chemical reactivity has proven particularly valuable, expressing rate constants for polar bimolecular reactions through a linear free-energy relationship containing three empirical parameters: electrophilicity (E), nucleophilicity (N), and a nucleophile-specific sensitivity parameter (sN) [10].

The Mayr-Patz equation enables computation of rate constants: log k = sN (E + N)

Where k is the rate constant for the reaction between an electrophile and nucleophile [10]. This formalism has been successfully applied to predict reactivity for a wide range of electrophile-nucleophile combinations, with parameters determined for 352 electrophiles and 1,281 nucleophiles in Mayr's Database of Reactivity Parameters [10].

Data-Driven Workflows for Reactivity Prediction

Traditional determination of reactivity parameters requires time-consuming experiments. Recent advances employ machine learning to build predictive models using structural descriptors as input, enabling real-time reactivity assessment [10]. A novel two-step workflow has been developed to overcome limitations of small datasets:

- Step 1: High-dimensional structural descriptors are linked with quantum molecular properties using Gaussian process regression

- Step 2: The quantum molecular properties are linked to experimental reactivity parameters using multivariate linear regression

This approach significantly reduces computational requirements while maintaining accuracy, as quantum chemical calculations are only needed for a small subset of compounds in the training phase rather than for every prediction [10].

Figure 1: QSRR Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the two-step workflow for predicting chemical reactivity from structural information, reducing dependency on quantum calculations.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Protocol: Density Functional Theory Calculations for Electronic Properties

Objective: Determine optimized molecular geometry, frontier molecular orbital energies, and molecular electrostatic potential of organic compounds.

Materials and Software:

- Gaussian 09 software package (or subsequent versions)

- High-performance computing cluster with multi-core processors

- Visualization software (GaussView, Avogadro, or similar)

Procedure:

- Initial Geometry Construction: Build molecular structure using chemical drawing software or crystallographic data

- Geometry Optimization: Perform full geometry optimization using DFT method (B3LYP hybrid functional recommended) with 6-31G(d) basis set

- Frequency Calculation: Confirm optimized structure corresponds to true energy minimum (no imaginary frequencies)

- Electronic Property Calculation: Compute HOMO/LUMO energies, orbital distributions, and MEP using same theoretical level

- Data Analysis: Calculate global reactivity descriptors (ΔE, hardness, electrophilicity) from orbital energies

- Visualization: Generate spatial representations of molecular orbitals and electrostatic potential maps

Validation: Compare calculated parameters with experimental data where available (UV-Vis spectroscopy for HOMO-LUMO gap, NMR for charge distribution) [8]

Protocol: Quantitative Structure-Reactivity Relationship Development

Objective: Develop predictive model for reactivity parameters based on structural descriptors.

Materials:

- Set of compounds with known reactivity parameters (training set)

- Molecular descriptor calculation software (Dragon, RDKit, or similar)

- Statistical analysis environment (Python/R with ML libraries)

Procedure:

- Data Curation: Compile experimental reactivity parameters for diverse compound set

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute structural descriptors (topological, geometrical, constitutional) for all compounds

- Feature Selection: Reduce descriptor dimensionality using correlation analysis and principal component analysis

- Model Training: Implement two-step workflow with Gaussian process regression and multivariate linear regression

- Model Validation: Assess predictive performance using cross-validation and external test sets

- Applicability Domain: Define structural domain where model provides reliable predictions

Interpretation: Analyze model coefficients to identify structural features most influential on reactivity [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reactivity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G(d) Computational Method | Density functional theory calculation | Geometry optimization, electronic property calculation | Hybrid functional with double-zeta basis set plus polarization functions |

| Gaussian 09 Software | Electronic structure modeling | Quantum chemical calculations of molecular properties | Version AS64L-G09RevD.01 or newer; requires UNIX/Linux environment |

| Benzhydrylium Ions | Reference electrophiles | Reactivity parameter determination and calibration | Mayr's database includes 27 derivatives with E parameters from -7.69 to 8.02 |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactive molecule data | Selectivity assessment and compound characterization | Contains >1.8 million compounds with bioactivity data |

| canSAR Knowledgebase | Integrated chemogenomic data | Target assessment and chemical probe evaluation | Integrates structural biology, compound pharmacology, and target annotation |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation | Conformational sampling | Generates ensemble of molecular conformations | CHARMM, GROMACS, or AMBER software packages |

| Docking Software (HADDOCK) | Biomolecular complex prediction | Protein-ligand interaction studies | Incorporates experimental data as restraints during docking |

| X-ray Crystallography | 3D structure determination | Experimental electron density mapping | Provides reference structures for computational methods |

| Osilodrostat | Osilodrostat (Isturisa)|11β-Hydroxylase Inhibitor for Research | Osilodrostat is a potent 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) inhibitor for Cushing's disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Beclabuvir Hydrochloride | Beclabuvir Hydrochloride, CAS:958002-36-3, MF:C36H46ClN5O5S, MW:696.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Chemical Probe Assessment and Selectivity Profiling

The objective assessment of chemical probes represents a critical application of reactivity principles in biomedical research. Probe Miner exemplifies a data-driven approach that evaluates chemical tools against objective criteria including potency (<100 nM biochemical activity), selectivity (>10-fold against other targets), and cellular activity (<10 μM cellular potency) [11]. Systematic analysis reveals that of >1.8 million compounds in public databases, only 2,558 (0.7% of human-active compounds) satisfy these minimum requirements for use as chemical probes, covering just 250 human proteins (1.2% of the human proteome) [11].

This scarcity of high-quality chemical tools highlights the importance of rational design based on reactivity principles. Kinases represent a success story where broad selectivity profiling has led to a disproportionate number of quality probes, comprising half of the 50 protein targets with the greatest number of minimum-quality probes [11]. This demonstrates how awareness of selectivity as a critical factor drives improvements in chemical tool development.

Integration of Computational and Experimental Methods

Four major strategies have emerged for combining computational methods with experimental data in structural biology and drug discovery:

- Independent Approach: Computational and experimental protocols performed separately with subsequent comparison of results

- Guided Simulation: Experimental data incorporated as restraints to guide conformational sampling

- Search and Select: Computational generation of large conformational ensembles followed by experimental data filtering

- Guided Docking: Experimental data used to define binding sites in molecular docking [7]

The choice of strategy involves trade-offs between computational efficiency, conformational coverage, and agreement with experimental data. For drug discovery applications, the guided docking approach has proven particularly valuable when experimental constraints on binding sites are available [7].

The fundamental relationship between structural features, electronic properties, and chemical reactivity provides a powerful foundation for predictive molecular design in pharmaceutical research. Through the integrated application of computational chemistry, quantitative structure-reactivity relationships, and experimental validation, researchers can accelerate the development of targeted chemical tools and therapeutic agents with optimized properties. As these methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with advances in machine learning and high-throughput characterization, their impact on rational drug design will undoubtedly expand, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and more targeted modulation of biological systems.

In the field of drug discovery, a pharmacophore is formally defined as a set of common chemical features that describe the specific ways a ligand interacts with a macromolecule's active site in three dimensions [12]. These features include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, charged or ionizable groups (anionic or cationic centers), hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings, which collectively determine the biological activity of a compound through complementary interactions with its biological target [12]. Functional groups serve as the fundamental building blocks of these pharmacophoric patterns, creating a direct link between molecular structure and biological function. The identification and mapping of these critical functional groups enable medicinal chemists to understand, optimize, and design novel bioactive compounds with enhanced efficacy, selectivity, and drug-like properties.

The concept of the pharmacophore provides a powerful framework for understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR), which assume that the biological activity of a compound is primarily determined by its molecular structure [13]. This hypothesis is supported by the principle of similarity, where compounds with similar structures often exhibit similar activities [13]. Functional group mapping allows researchers to transcend simple structural similarity and focus on the essential electronic and steric features necessary for biological recognition and response, making it possible to identify structurally diverse compounds that share the same pharmacophore and thus exhibit similar biological effects.

Fundamental Pharmacophoric Features and Their Functional Group Components

Core Pharmacophoric Features

Pharmacophoric features represent abstracted chemical functionalities rather than specific atoms or functional groups. The steric feature of the receptor comprises excluded volumes that represent areas sterically hindered by the binding cavity [12]. These features can be categorized into specific types, each with distinct geometric and electronic properties that define their interactions with biological targets. The spatial arrangement of these features, including their distances and angles, is critical for biological activity.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Functional Group Representations

| Feature Type | Chemical Significance | Representative Functional Groups | Geometric Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Positively polarized hydrogen attached to electronegative atom | Hydroxyl (-OH), Amine (-NH-, -NH₂), Amide (-NH₂) | Directional; sp² hybridized: ~50° cone [12] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Electron-rich atom with lone pair electrons | Carbonyl (>C=O), Ether (-O-), Nitrile (-C≡N), Amine (-N<) | Directional; sp³ hybridized: ~34° torus [12] |

| Hydrophobic | Non-polar regions favoring lipid environments | Alkyl chains, Aromatic rings, Steroid skeletons | Non-directional; varies by size/shape |

| Aromatic | π-electron systems for stacking interactions | Phenyl, Pyridine, Other heteroaromatics | Planar; face-to-face or edge-to-face |

| Ionizable | Positively or negatively charged groups | Carboxylate (-COOâ»), Ammonium (-NH₃âº), Phosphate (-PO₄²â») | Strong, long-range electrostatic |

Three-Dimensional Characteristics

The three-dimensional arrangement of pharmacophoric features is essential for biological activity. For hydrogen-bonding features, the structure of rigid hydrogen-bond interactions at sp2 hybridized heavy atoms is typically represented as a cone with a cutoff apex, with a default range of angles of approximately 50 degrees [12]. For more flexible hydrogen-bond interactions at sp3 hybridized heavy atoms, a torus representation is used with a default range of angles of precisely 34 degrees [12]. These geometric constraints reflect the precise molecular recognition requirements of biological systems and highlight the importance of conformational analysis in pharmacophore modeling.

Hydrophobic features represent another critical element, with pharmacophores with lower hydrophobicity features corresponding to those with higher minimum thresholds, resulting in more restrictive handling of hydrophobic characteristics [12]. Aromatic features encompass pi-pi interaction and cation-pi interaction capabilities, which play significant roles in binding to aromatic or cationic protein moieties [12]. Understanding these features at the functional group level provides the foundation for rational drug design and optimization strategies.

Methodological Approaches for Pharmacophore Analysis

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore design leverages known three-dimensional structures of biological targets, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or NMR spectroscopy [12]. This approach begins with analysis of the protein binding site to identify regions that can form specific interactions with ligand functional groups. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become increasingly valuable in this context, as they determine the coordinates of a protein-ligand complex with respect to time, providing detailed study of atomic dynamics, solvent effects, and the free energy associated with protein-ligand binding [12].

The process typically involves identifying key interaction points in the binding site, such as hydrogen bonding opportunities, hydrophobic patches, and regions accommodating charged groups. These points are then translated into pharmacophoric features with specific geometric constraints. Selectivity can be fine-tuned by adding or removing feature constraints, providing various manipulation options to optimize the model for virtual screening or lead optimization [12]. Several commercial and open-source in silico software platforms are available for structure-based pharmacophore modeling, making this approach widely accessible to drug discovery researchers.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When three-dimensional structural information of the biological target is unavailable, the ligand-based approach to pharmacophore modeling addresses this absence by building models from a collection of known active ligands [12]. This method considers the conformational flexibility of ligands, recognizing that structurally similar small molecules often exhibit similar biological activity [12]. The approach identifies shared feature patterns within a set of active ligands, requiring extensive screening to determine the protein target and corresponding binding ligands.

The ligand-based pharmacophore development process typically involves multiple steps: selecting a diverse set of known active compounds, generating representative conformational ensembles for each compound, identifying common pharmacophoric features across the set, and defining their optimal spatial relationships. This approach is particularly valuable for targets with limited structural information, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels. The resulting models can be used for virtual screening to identify novel chemotypes with potential biological activity, demonstrating how functional group patterns derived from known actives can guide the discovery of new lead compounds.

Computational Functional Group Mapping (cFGM)

Computational functional group mapping (cFGM) has emerged as a high-impact complement to existing experimental and computational structure-based drug discovery methods [14]. cFGM provides comprehensive atomic-resolution 3D maps of the affinity of functional groups that can constitute drug-like molecules for a given target, typically a protein [14]. These 3D maps can be intuitively and interactively visualized by medicinal chemists to rapidly design synthetically accessible ligands.

Advanced implementations of cFGM utilize all-atom explicit-solvent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which offer significant advantages including the detection of low-affinity binding regions, comprehensive mapping for all functional groups across all regions of the target structure, and prevention of aggregation artifacts that can plague experimental approaches [14]. Methods such as co-solvent mapping, MixMD, and SILCS (Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation) employ organic solvents or small fragment molecules as probes to identify favorable binding positions for different functional group types [14]. The resulting probability maps provide quantitative data on functional group preferences throughout the binding site, enabling more informed design decisions.

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Mapping

Structure-Based Workflow

The structure-based pharmacophore modeling protocol begins with preparation of the protein structure, including addition of hydrogen atoms, assignment of protonation states, and optimization of hydrogen bonding networks. The binding site is then defined and analyzed to identify key interaction points:

Protein Preparation:

- Remove water molecules except those mediating key interactions

- Add missing side chains and loops using modeling software

- Optimize hydrogen bonding networks considering physiological pH

Binding Site Analysis:

- Identify hydrophobic pockets and clefts

- Map hydrogen bond donors and acceptors on the protein surface

- Locate charged regions suitable for electrostatic interactions

Feature Generation:

- Convert interaction points to pharmacophoric features

- Define geometric constraints based on interaction type

- Add excluded volumes to represent steric constraints

This protocol enables creation of pharmacophore models that directly reflect the complementarity between functional groups and their target binding site.

Ligand-Based Workflow

For ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, the protocol focuses on identifying common features among known active compounds:

Ligand Set Selection:

- Curate a diverse set of confirmed active compounds

- Include compounds with varying potency to identify features correlated with activity

- Select structurally diverse compounds to ensure robust feature identification

Conformational Analysis:

- Generate representative conformational ensembles for each compound

- Consider energy thresholds and biological relevance

- Account for flexibility and accessible rotatable bonds

Common Feature Identification:

- Superimpose compound conformations to identify spatial overlap

- Detect recurring functional groups at conserved positions

- Define tolerance radii for feature matching

This approach is particularly valuable for target classes where structural information is limited, allowing researchers to leverage known structure-activity relationship data effectively.

Visualization of Pharmacophore Modeling Workflows

Advanced Computational Approaches

Hierarchical Functional Group Ranking

Recent advances in computational approaches include hierarchical functional group ranking via IUPAC name analysis, which generates a descending order of functional groups based on their importance for specific biological targets [15]. This approach, demonstrated in a case study on TDP1 inhibitors, employs machine learning algorithms like Random Forest Classifier to achieve significant predictive accuracy (70.9% accuracy, 73.1% precision, 69.4% F1 score) in identifying critical functional groups for drug discovery [15]. By analyzing IUPAC names, this method systematically deconstructs molecular structures into their functional group components and ranks them according to their contribution to biological activity.

This hierarchical ranking enables medicinal chemists to focus on the most impactful functional groups during optimization campaigns, potentially accelerating the lead optimization process. The approach is particularly valuable for complex target classes where multiple functional groups contribute to binding affinity and specificity, allowing researchers to prioritize modifications that are most likely to improve compound potency.

Cross-Structure-Activity Relationship (C-SAR)

The Cross-Structure-Activity Relationship (C-SAR) approach represents an innovative methodology that extends beyond traditional SAR by analyzing pharmacophoric substituents across diverse chemotypes with distinct substitution patterns [16]. This method utilizes matched molecular pairs (MMP) analysis, where molecules with the same parent structure are compared to extract SAR information from compound series [16]. By examining MMPs with various parent structures, researchers can identify how specific pharmacophoric substitutions at particular positions affect biological activity across different structural scaffolds.

C-SAR facilitates structural development by providing guidelines for converting inactive compounds into active ones, applicable to either the same parent structure or entirely different chemotypes [16]. This approach addresses limitations of traditional methods like the Topliss scheme, which requires the parent compound to remain intact and proves less effective for molecules targeting membrane receptors [16]. C-SAR accelerates SAR expansion by applying existing knowledge of various compounds targeting the same biological entity to new chemotypes requiring modification.

AI-Driven Molecular Representation

Modern artificial intelligence approaches are revolutionizing how functional groups are represented and analyzed in drug discovery. AI-driven molecular representation methods employ deep learning techniques to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large and complex datasets [17]. Models such as graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformers enable these approaches to move beyond predefined rules, capturing both local and global molecular features [17].

These advanced representations facilitate scaffold hopping – the discovery of new core structures while retaining similar biological activity – by capturing subtle structural and functional relationships that may be overlooked by traditional methods [17]. Language model-based approaches treat molecular representations like SMILES as a specialized chemical language, while graph-based methods directly represent molecular structure as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [17]. These AI-driven representations have shown remarkable capability in identifying novel scaffolds with maintained pharmacophoric features, significantly expanding the explorable chemical space for drug discovery.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Functional Group Analysis

| Method Class | Key Methodologies | Applications in Pharmacophore Analysis | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based | Molecular docking, MD simulations, Binding site analysis | Direct mapping of functional group interactions, Identification of key binding features | Target-specific, Physically realistic |

| Ligand-Based | Pharmacophore elucidation, QSAR, Matched molecular pairs | Identification of common features across active compounds, Activity prediction | No target structure needed, Leverages existing bioactivity data |

| AI-Driven | Graph neural networks, Transformer models, Deep learning | Scaffold hopping, Molecular generation, Activity prediction | Handles complex patterns, Explores novel chemical space |

| cFGM | SILCS, MixMD, Co-solvent mapping | Comprehensive mapping of functional group preferences, Hot spot identification | Accounts for flexibility and solvation, Comprehensive coverage |

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Pharmacophore Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Pharmacophore Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [16], DataWarrior [16], GROMACS [12], AMBER [12], LAMMPS [12] | Molecular visualization, docking, dynamics simulations, and pharmacophore modeling |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL [16], PubChem Bioassays [15] | Sources of chemical structures and associated bioactivity data for model building and validation |

| Molecular Descriptors | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) [17], AlvaDesc descriptors [17] | Quantification of molecular properties and structural features for QSAR and machine learning |

| Specialized Probes | Organic solvents (isopropanol, acetonitrile) [14], Fragment libraries [14] | Computational mapping of functional group preferences in binding sites |

| Validation Tools | ROC curves, Applicability domain assessment [18] | Assessment of model reliability and predictive performance |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Design

Virtual Screening and Lead Identification

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening enables the selection of desired property compounds from large molecular libraries, facilitating the identification of novel leads and hits for further development [12]. This approach leverages the essential pharmacophoric features of known active compounds to search database for molecules that share the same feature arrangement, potentially identifying structurally distinct compounds with similar biological activity. The effectiveness of virtual screening depends on accurate active site identification for good binding affinity, which can be guided by extensive literature review of the amino acid sequences present at active sites [12].

Pharmacophore models provide solutions in terms of identifying structurally discrete compounds from retrieved hits [12], enabling scaffold hopping and expansion of chemical diversity in screening hits. This application demonstrates the power of functional group-based approaches to transcend simple structural similarity and focus on essential interaction capabilities, potentially identifying novel chemotypes that would be missed by traditional similarity-based screening methods.

Scaffold Hopping and Molecular Optimization

Scaffold hopping represents a crucial application of pharmacophore principles in drug discovery, aimed at discovering new core structures while retaining similar biological activity as the original molecule [17]. This strategy helps address issues with existing lead compounds, such as toxicity or metabolic instability, while potentially enhancing molecular activity and improving pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles [17]. By modifying the core structure of a molecule, researchers can discover novel compounds with similar biological effects but different structural features, thus navigating around existing patent limitations.

Modern scaffold hopping increasingly utilizes AI-driven molecular generation methods, including variational autoencoders and generative adversarial networks, to design entirely new scaffolds absent from existing chemical libraries [17]. These approaches leverage advanced molecular representations that capture nuances in molecular structure potentially overlooked by traditional methods, allowing for more comprehensive exploration of chemical space and discovery of new scaffolds with unique properties while maintaining critical pharmacophoric features.

ADMET Optimization

Functional group analysis plays a critical role in optimizing absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties of drug candidates. The bioavailability of a drug is based on the absorption and metabolism of a compound, with absorption depending on solubility and lipophilicity, which can be modified by the addition of specific functional groups [19]. SAR approaches can determine key parameters including solubility, metabolic rate, and other factors between drugs, guiding strategic functional group modifications to improve drug-like properties.

For toxicity assessment, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models have been developed for predicting various toxicity endpoints, including thyroid hormone system disruption [18]. These models leverage molecular descriptors and machine learning approaches to identify structural features and functional groups associated with adverse effects, supporting early-stage toxicity risk assessment in drug discovery. The integration of pharmacophore modeling with ADMET prediction enables multi-parameter optimization, balancing potency with developability considerations.

Emerging Trends and Technologies

The field of functional group pharmacophore analysis continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future development. AI-driven molecular representation methods are increasingly moving beyond traditional structural data, facilitating exploration of broader chemical spaces and accelerating scaffold hopping [17]. These approaches include advanced language models, graph-based representations, and novel learning strategies that greatly improve the ability to characterize molecules and their functional group components.

Integration of molecular dynamics simulations with pharmacophore modeling represents another significant trend, providing more realistic representation of protein flexibility and solvation effects [14]. Methods like Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) and MixMD use all-atom explicit-solvent MD to generate comprehensive functional group maps that account for protein flexibility and solvent competition, offering more reliable guidance for molecular design [14]. These approaches detect low-affinity binding regions and provide functional group affinity information across the entire target structure, not just the primary binding site.

Functional groups serve as the fundamental building blocks of pharmacophores, creating an essential link between molecular structure and biological function. Through various computational and experimental approaches, including structure-based design, ligand-based modeling, computational functional group mapping, and emerging AI-driven methods, researchers can identify and optimize the critical functional group arrangements responsible for biological activity. These methodologies enable efficient navigation of chemical space, facilitation of scaffold hopping, and optimization of drug-like properties, collectively accelerating the drug discovery process.

As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the precision and applicability of functional group pharmacophore analysis continues to expand. The integration of physical principles with data-driven approaches promises to further enhance our ability to design functional group combinations with optimal biological activity, potentially transforming drug discovery from a largely empirical process to a more rational and predictive endeavor. This progression underscores the enduring importance of understanding functional groups as critical determinants of pharmacological activity in medicinal chemistry and drug development.

The principle that similar molecular structures elicit similar biological activities is a foundational concept in medicinal chemistry and drug design. However, the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) paradox challenges this assumption, describing the common occurrence where minute structural changes lead to dramatic activity differences [20] [21]. This paradox presents significant challenges in drug discovery, often leading to late-stage failures and increased development costs. Understanding the underlying causes of this phenomenon—from subtle variations in functional group interactions to complex ligand-receptor dynamics—is crucial for advancing predictive toxicology and rational drug design. This whitepaper examines the SAR paradox through the lens of functional group chemistry, providing quantitative frameworks and experimental methodologies to navigate this complex landscape.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone approach in computational chemistry, relating a set of predictor variables (molecular descriptors) to the potency of a biological response [20]. These models operate on the fundamental premise that structurally similar compounds will exhibit similar biological effects, allowing for the prediction of activities for novel chemical entities. The basic assumption for all molecule-based hypotheses is that similar molecules have similar activities, a principle also called Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) [20].

The SAR paradox refers to the observable fact that it is not the case that all similar molecules have similar activities [20]. This phenomenon was first articulated by Maggiora, who visualized SAR datasets as 3D landscapes where the X-Y plane corresponds to chemical structure and the Z-axis represents biological activity [21]. In this conceptual model, most SAR datasets form smoothly rolling surfaces where similar structures have similar activities. However, pairs with similar structures but very different activities represent dramatic peaks or gorges in this landscape, termed "activity cliffs" [21]. From a mathematical perspective, these pairs represent discontinuities in the function describing the relation between chemical structure and biological activity, violating the smoothness assumptions of many statistical modeling approaches [21].

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in SAR Analysis

| Term | Definition | Implication for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| SAR Paradox | The phenomenon where structurally similar compounds exhibit significantly different biological activities [20] | Challenges predictive modeling and lead optimization efforts |

| Activity Cliff | A pair of structurally similar compounds with large differences in biological potency [21] | Represents significant discontinuities in chemical-biological activity relationships |

| Smooth SAR | Gradual changes in activity corresponding to gradual structural modifications [21] | Ideal for rational drug design and property optimization |

| Scaffold Hop | Structurally dissimilar compounds exhibiting similar biological activities [21] | Enprises identification of novel chemotypes with desired activity |

Quantifying and Visualizing the SAR Paradox

Numerical Characterization of Activity Landscapes

Several computational approaches have been developed to quantify the nature of SAR landscapes and identify activity cliffs. The Structure Activity Landscape Index (SALI) provides a pairwise measure of activity cliff intensity, defined as:

SALI(i,j) = |Aáµ¢ - Aâ±¼| / (1 - sim(i,j))

where Aáµ¢ and Aâ±¼ represent the biological activities of compounds i and j, and sim(i,j) denotes their structural similarity (typically ranging from 0-1) [21]. Higher SALI values indicate more pronounced activity cliffs, helping researchers identify problematic regions in chemical datasets.

An alternative approach, the SAR Index (SARI), addresses groups of molecules for specific targets and enables direct identification of continuous and discontinuous SAR trends [21]. SARI is defined as:

SARI = ½(score꜀ₒₙₜ + (1 - scoreð’¹áµ¢â‚›ð’¸))

where the continuity score (score꜀ₒₙₜ) is derived from the potency-weighted mean similarity between molecules, and the discontinuity score (scoreð’¹áµ¢â‚›ð’¸) represents the product of average potency difference and pairwise ligand similarities [21].

Visualization Approaches for SAR Landscapes

Structure-Activity Similarity (SAS) maps provide a powerful two-dimensional visualization tool, plotting structural similarity against activity similarity [21]. These maps can be divided into four key regions representing different SAR behaviors:

- Smooth SAR regions: High structural similarity, high activity similarity

- Activity cliffs: High structural similarity, low activity similarity

- Scaffold hops: Low structural similarity, high activity similarity

- Non-descript regions: Low structural similarity, low activity similarity

Table 2: Quantitative Measures for SAR Landscape Analysis

| Method | Formula | Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SALI | SALI(i,j) = |Aáµ¢ - Aâ±¼| / (1 - sim(i,j)) | Pairwise activity cliff identification | Focuses on individual molecule pairs independent of targets |

| SARI | SARI = ½(score꜀ₒₙₜ + (1 - scoreð’¹áµ¢â‚›ð’¸)) | Group-based SAR trend analysis | Allows identification of continuous/discontinuous trends for specific targets |

| SAS Maps | Plot of structural similarity vs. activity similarity | Dataset visualization and classification | Enables visual identification of different SAR regions and behaviors |

Experimental Protocols for SAR Analysis

Data Set Preparation and Compound Selection

The principal steps of QSAR/QSPR studies begin with careful selection of data sets and extraction of structural descriptors [20]. For robust model development:

- Collect homogeneous bioactivity data: Prefer data from standardized assays (e.g., Ki or IC50 values from the ChEMBL database) [22]. For compounds with multiple experimental values, use median values to better characterize strongly skewed distributions [22].

- Apply stringent filtering: Include only single electroneutral small organic molecules (molecular weight range: 50-1250 Da) to ensure descriptor applicability [22].

- Define activity thresholds: For classification models, establish appropriate thresholds between active and inactive compounds (e.g., 1 μM for antitarget inhibition studies) [22].

- Implement cross-validation splits: Divide data sets into five unique parts using fivefold cross-validation procedures, where each part serves as an external test set while the remaining parts form the training set [22].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Variable Selection

Different QSAR approaches utilize distinct molecular representations:

- Fragment-based descriptors: Decompose molecules into functional groups or substructures to calculate contributions [20].

- 3D-QSAR descriptors: Compute molecular force fields using three-dimensional structures aligned by experimental data or superimposition software [20].

- Chemical descriptors: Quantify electronic, geometric, or steric properties of molecules as a whole [20].

- Topological descriptors: Encode molecular structure as graphs or fingerprints for similarity calculations [21].

Variable selection represents a critical step to avoid overfitting, particularly when working with large descriptor sets [20]. Approaches include visual inspection (qualitative selection by domain experts), data mining algorithms, or molecule mining techniques.

Model Validation and Applicability Domain Assessment

Robust validation is essential for reliable QSAR models [20]:

- Internal validation: Perform cross-validation to assess model robustness.

- External validation: Split available data into training and prediction sets to evaluate predictivity.

- Data randomization: Apply Y-scrambling to verify absence of chance correlations.

- Applicability domain (AD) assessment: Define the chemical space region where models make reliable predictions.

Recent studies highlight that the applicability domain plays a significant role in assessing QSAR model reliability, with qualitative predictions often proving more reliable than quantitative ones against regulatory criteria [23].

Case Studies: Functional Groups and the SAR Paradox

Sulphonamide Antimicrobials

Sulphonamides represent a classic case where subtle functional group modifications dramatically alter biological activity. The parent compound, sulphanilamide, exhibits antibacterial activity, but SAR studies revealed that:

- The amino and sulphonyl radicals must maintain 1,4-position on the benzene ring for optimal activity [24].

- Replacement of the amino group by nitro, hydroxy, or methyl groups diminishes or abolishes activity [24].

- Substitution of the sulphonamide nitrogen (N¹) by alkyl, acyl, or aryl groups typically reduces both toxicity and activity [24].

- N¹-heterocyclic substituents enhance activity, reduce toxicity, and significantly modify pharmacokinetic properties [24].

Notably, the only exception to the 1,4-requirement is metachloridine, which showed better activity than p-aminobenzenesulphonamides against avian malaria, demonstrating that the SAR paradox sometimes enables beneficial deviations from established patterns [24].

Chlorinated N-arylcinnamamides as Arginase Inhibitors

Recent research on chlorinated N-arylcinnamamides targeting Plasmodium falciparum arginase reveals pronounced SAR paradox manifestations. A series of seventeen 4-chlorocinnamanilides and seventeen 3,4-dichlorocinnamanilides showed that:

- 3,4-dichlorocinnamanilides typically exhibited broader activity ranges compared to 4-chlorocinnamanilides [25].

- The most potent derivative, (2E)-N-[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)prop-2-en-amide, demonstrated IC50 = 1.6 μM [25].

- Molecular docking revealed that chlorinated aromatic rings orient toward the binuclear manganese cluster in energetically favorable poses [25].

- The fluorine substituent (alone or in trifluoromethyl groups) on the N-phenyl ring plays a key role in forming halogen bonds, explaining dramatic potency differences despite structural similarity [25].

This case study exemplifies how specific functional group interactions with enzyme active sites can create activity cliffs, where minor halogen substitutions dramatically influence binding affinity and inhibitory potency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SAR Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Public repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Source of standardized bioactivity data (Ki, IC50 values) for model development [22] |

| GUSAR Software | QSAR modeling using QNA and MNA descriptors | Creation of classification and regression models for antitarget inhibition prediction [22] |

| SAS Map Visualization | 2D plot of structural vs. activity similarity | Identification of activity cliffs and smooth SAR regions in compound datasets [21] |

| SALI Calculator | Pairwise activity cliff quantification | Numerical assessment of activity cliff intensity between similar compounds [21] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Chemical modifiers for structure-function studies | Investigation of functional group distribution and electrostatic interactions (e.g., calcium ions in starch modification) [26] |

| VEGA Platform | Integrated QSAR model suite | Environmental fate prediction of cosmetic ingredients under animal testing bans [23] |

| Ledipasvir | Ledipasvir, CAS:1256388-51-8, MF:C49H54F2N8O6, MW:889.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AMG319 | AMG319, CAS:1608125-21-8, MF:C21H16FN7, MW:385.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Functional Group Research

The SAR paradox carries profound implications for drug discovery pipelines and functional group research:

Lead Optimization Challenges: Erratic SAR behavior often predicts lead optimization difficulties, potentially indicating mechanism hopping or indirect activity [24]. A "clean SAR" with interpretable, continuous activity changes suggests well-behaved, on-target activity, while activity cliffs may signal underlying complexities.

Predictive Model Limitations: Comparative studies reveal that qualitative SAR models often outperform quantitative QSAR models in prediction accuracy. For antitarget inhibition, qualitative models demonstrated balanced accuracy of 0.80-0.81 versus 0.73-0.76 for quantitative models [22].

Functional Group Interactions: The SAR paradox underscores that biological activity depends not merely on presence/absence of specific functional groups but on their precise three-dimensional orientation, electronic properties, and interactions with biological targets. Research on oxidized starch demonstrates how introducing carbonyl and carboxyl groups through oxidation dramatically alters electrostatic interactions and binding capabilities [26].

Regulatory Science Applications: With increasing bans on animal testing (particularly for cosmetics), QSAR models face growing importance in regulatory decision-making [23]. Understanding the SAR paradox helps establish appropriate applicability domains and reliability assessments for these models.

The SAR paradox represents both a challenge and opportunity in chemical research and drug discovery. While activity cliffs complicate predictive modeling and rational design, they also offer invaluable insights into the fundamental mechanisms of molecular recognition and function. By employing advanced quantification methods like SALI and SARI, visualization approaches including SAS maps, and rigorous experimental protocols, researchers can better navigate the complexities of structure-activity relationships. Future research should focus on integrating high-quality experimental data with sophisticated computational models that explicitly account for the discontinuous nature of activity landscapes, ultimately transforming the SAR paradox from an obstacle into a source of deeper chemical understanding.

From Structure to Prediction: QSAR and Machine Learning for Property Forecasting

Principles of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a computational approach that mathematically links the chemical structure of compounds to their biological activity or physicochemical properties [20]. These models are regression or classification tools that use physicochemical properties or theoretical molecular descriptors of chemicals as predictor variables (X) to estimate the potency of a biological response variable (Y) [20]. The fundamental premise of QSAR is that the biological activity of a compound is primarily determined by its molecular structure, supported by the observation that compounds with similar structures often exhibit similar activities—a principle known as the similarity principle [13] [27].

The historical development of QSAR began with observations by Meyer and Overton that the narcotic properties of gases and organic solvents correlated with their solubility in olive oil [28]. A significant advancement came with the introduction of Hammett constants, which quantified the effects of substituents on reaction rates in organic molecules [28]. The field formally emerged in the early 1960s with the pioneering work of Hansch and Fujita, who developed a method that incorporated electronic properties of substituents, and Free and Wilson, who introduced an additive approach to quantify substituent effects at different molecular positions [28]. Over the subsequent six decades, QSAR has evolved from using few easily interpretable descriptors and simple linear models to employing thousands of chemical descriptors and complex machine learning methods [13].

In modern drug discovery and development, QSAR modeling serves crucial roles in prioritizing promising drug candidates, reducing animal testing, predicting chemical properties, guiding chemical modifications, and supporting regulatory decisions for chemical risk assessment [27]. The integration of QSAR with functional group research provides a powerful framework for understanding how specific chemical moieties contribute to biological activity, enabling more rational drug design strategies [14] [29].

Theoretical Foundations

Basic Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The fundamental principle underlying QSAR is that variations in molecular structure produce corresponding changes in biological activity [27]. This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [20]

The error term encompasses both model error (bias) and observational variability that occurs even with a correct model [20]. In practice, QSAR models can take either linear or nonlinear forms. Linear QSAR models assume a linear relationship between molecular descriptors and biological activity, expressed as:

Activity = wâ‚(descriptorâ‚) + wâ‚‚(descriptorâ‚‚) + ... + wâ‚™(descriptorâ‚™) + b + ε [27]

Where wᵢ represents the model coefficients, b is the intercept, and ε is the error term. Examples include multiple linear regression (MLR) and partial least squares (PLS) [27]. Nonlinear QSAR models capture more complex relationships using nonlinear functions:

Activity = f(descriptorâ‚, descriptorâ‚‚, ..., descriptorâ‚™) + ε [27]

Where f is a nonlinear function learned from the data, implemented using methods like artificial neural networks (ANNs) or support vector machines (SVMs) [27].

The SAR Paradox

A fundamental concept in QSAR modeling is the Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) paradox, which states that it is not universally true that all similar molecules have similar activities [20]. The underlying challenge is that different types of biological activities (e.g., reaction ability, biotransformation, solubility, target activity) may depend on different molecular differences [20]. This paradox highlights the importance of selecting appropriate descriptors that specifically correlate with the targeted biological endpoint rather than relying solely on general structural similarity measures.

Dimensions of QSAR

QSAR methodologies have evolved through multiple dimensions of increasing complexity:

Table: Evolution of QSAR Dimensions

| Dimension | Key Characteristics | Representative Methods |

|---|---|---|

| 1D-QSAR | Based on single physicochemical properties | Simple regression using properties like solubility or pKa |

| 2D-QSAR | Considers connectivity and substituent effects | Hansch analysis, Free-Wilson method |

| 3D-QSAR | Incorporates three-dimensional ligand structure | Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) |

| 4D-QSAR | Includes multiple ligand conformations | Multiple conformation sampling |

| 5D-QSAR | Accounts for induced fit and protein flexibility | Explicit protein flexibility simulation |

The progression from 1D to 5D-QSAR represents increasing capability to capture the complex nature of biomolecular interactions, with higher dimensions addressing critical factors such as ligand conformation, orientation, and receptor flexibility [30].

Essential Components of QSAR Modeling

Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors are mathematical representations of molecular structures that quantify their characteristics, serving as the fundamental variables in QSAR models [13]. These descriptors should comprehensively represent molecular properties, correlate with biological activity, be computationally feasible, have distinct chemical meanings, and be sensitive enough to capture subtle structural variations [13].

Table: Types of Molecular Descriptors in QSAR

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Describe molecular composition without connectivity | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts |

| Topological | Based on molecular connectivity | Molecular connectivity indices, Wiener index |

| Geometric | Describe 3D molecular geometry | Molecular volume, surface area, shadow indices |

| Electronic | Characterize electronic distribution | Partial charges, dipole moment, HOMO/LUMO energies |

| Thermodynamic | Represent energy-related properties | LogP, refractivity, polarizability |

The information content of descriptors ranges from 0D to 4D, with gradual enrichment of information, though each type has distinct advantages and disadvantages [13]. Currently, no single descriptor can comprehensively represent all molecular structural features, necessitating careful selection based on the specific modeling objectives [13].

Datasets and Data Quality

High-quality datasets form the cornerstone of reliable QSAR models [13]. The quality and representativeness of datasets significantly influence a model's prediction and generalization capabilities [13]. Essential considerations for QSAR datasets include:

- Data Sources: Compile chemical structures and associated biological activities from reliable sources such as literature, patents, and public/private databases [27]

- Structural Diversity: Ensure the dataset covers diverse chemical space relevant to the problem [13]

- Experimental Consistency: Convert all biological activities to common units and scales, and document experimental conditions and metadata [27]

- Data Cleaning: Remove duplicate, ambiguous, or erroneous entries; standardize chemical structures (remove salts, normalize tautomers, handle stereochemistry) [27]

The impact of dataset quality cannot be overstated, as even sophisticated modeling algorithms cannot compensate for fundamentally flawed or non-representative input data [13] [31].

QSAR Modeling Workflow

The development of robust QSAR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing data preparation, model building, and validation. The following diagram illustrates the key stages in this process:

Data Preparation and Curation

Data preparation begins with compiling a dataset of chemical structures and their associated biological activities from reliable sources [27]. The dataset must be representative of the chemical space of interest, as model predictions are only reliable within the represented chemical space [28]. Data cleaning involves removing duplicates, standardizing chemical structures (including handling salts, tautomers, and stereochemistry), and converting biological activities to consistent units [27]. Missing values must be addressed through removal or imputation techniques like k-nearest neighbors or matrix factorization [27]. Finally, data normalization and scaling ensure that molecular descriptors contribute equally during model training, typically through standardization to z-scores [27].

Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection

Molecular descriptors are calculated using software tools such as PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit, Mordred, ChemAxon, or OpenBabel [27]. These tools can generate hundreds to thousands of descriptors, necessitating careful feature selection to identify the most relevant descriptors and improve model performance and interpretability [27]. Feature selection methods include:

- Filter Methods: Rank descriptors based on individual correlation or statistical significance

- Wrapper Methods: Use the modeling algorithm to evaluate descriptor subsets

- Embedded Methods: Perform feature selection during model training [27]

Model Building and Algorithm Selection

The dataset is typically split into training, validation, and external test sets, with the external test set reserved exclusively for final model assessment [27]. Algorithm selection depends on the complexity of the structure-activity relationship and dataset characteristics:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR): Simple, interpretable linear model

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): Handles multicollinearity in descriptor data

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Nonlinear approach robust to overfitting

- Neural Networks (NN): Flexible nonlinear models for complex patterns [27]

Cross-validation techniques, including k-fold and leave-one-out cross-validation, help prevent overfitting and provide reliable estimates of model generalization ability [27].

Validation and Applicability Domain

Validation Techniques

Model validation is critical for assessing predictive performance, robustness, and reliability [27] [31]. Comprehensive validation includes both internal and external approaches:

- Internal Validation: Uses training data to estimate predictive performance through techniques like k-fold cross-validation or leave-one-out cross-validation [27]

- External Validation: Employs an independent test set not used during model development to assess performance on unseen data [27]

- Data Randomization (Y-Scrambling): Verifies the absence of chance correlations between the response and modeling descriptors [20]

Internal validation provides an initial estimate of model performance but may be optimistic, while external validation offers a more realistic assessment of real-world applicability [27].

Applicability Domain Assessment

The Applicability Domain (AD) defines the chemical space where the QSAR model can make reliable predictions [31]. Determining the AD is essential, as predictions for compounds outside this domain are considered unreliable extrapolations [31]. The AD depends on the molecular descriptors and training set used to build the model [31]. The leverage approach is commonly used to identify chemicals outside the AD, helping researchers understand the limitations of their models and avoid erroneous predictions for structurally novel compounds [31].

OECD Validation Principles

For regulatory applications, QSAR models should follow the OECD principles for validation, which include:

- A defined endpoint

- An unambiguous algorithm

- A defined domain of applicability

- Appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity