Machine Learning in Chemical Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Reaction Yields for Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing chemical reaction yields, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical development.

Machine Learning in Chemical Synthesis: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Reaction Yields for Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing chemical reaction yields, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical development. It covers the foundational principles of moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches to data-driven experimentation. The scope includes a detailed examination of key ML methodologies like Bayesian optimization and self-driving laboratories, their practical application in optimizing complex reactions such as Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, and strategies for overcoming common challenges like data scarcity and high-dimensional search spaces. Finally, the article provides a comparative analysis of ML performance against traditional methods, validating its impact on accelerating process development and improving yields for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Reaction Optimization

The Limitations of Traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) and Human-Intuition-Driven Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the main limitation of the OFAT optimization method? OFAT examines one factor at a time while holding others constant. This approach fails to capture interactions between factors and can miss the true optimal condition in complex processes with interdependent variables [1]. It is less effective at covering the parameter search space compared to modern methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) [1].

2. How does human intuition fall short in experimental optimization? While valuable, human intuition is constrained by limited data processing capacity, susceptibility to cognitive biases, and reliance on precedent which may not apply to new conditions [2] [3]. It struggles to efficiently process the large, multi-dimensional datasets common in modern research, potentially overlooking subtle but critical patterns [4] [5].

3. What are the key advantages of using Machine Learning (ML) for optimization? ML algorithms can analyze vast amounts of data to identify complex, non-linear relationships and interactions between multiple factors that are difficult for humans to discern [1] [6]. They can predict optimal conditions, such as reaction parameters for higher device efficiency or drug efficacy, often surpassing outcomes achieved through traditional methods or purified materials [1] [6].

4. Can ML and human intuition be used together? Yes, a synergistic approach is often most effective. This can involve Human-in-the-Loop systems where AI provides data-driven recommendations and humans apply contextual knowledge and ethical considerations for final decision-making [4] [5]. This combines the scalability of AI with the creative problem-solving and strategic oversight of human experts [2] [4].

5. What is a real-world example where ML optimization outperformed traditional methods? In organic light-emitting device (OLED) development, a DoE and ML strategy optimized a macrocyclisation reaction. The device using the ML-predicted optimal raw material mixture achieved an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 9.6%, surpassing the performance of devices made with purified materials (which showed EQE <1%) [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Optimization Results and Inefficient Parameter Searching

- Symptoms: Consistently missing performance targets (e.g., yield, efficiency); experiments seem to hit a local maximum and cannot find further improvements; process is time- and resource-intensive.

- Cause: Relying solely on OFAT or unstructured, intuition-based experimentation.

- Solution:

- Switch to a DoE framework: Systematically vary multiple factors simultaneously according to a designed array (e.g., Taguchi's orthogonal arrays) to efficiently explore the parameter space [1].

- Integrate an ML model: Use machine learning methods like Support Vector Regression (SVR) or Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) to build a predictive model from your DoE data [1].

- Validate the model: Run test experiments at the predicted optimal conditions to confirm performance. For example, an SVR model predicted an EQE of 11.3%, and a validation run yielded a comparable 9.6% [1].

Problem: Inability to Capture Critical Factor Interactions

- Symptoms: Changing one factor leads to unpredictable or inconsistent changes in the outcome; the "best" condition for one factor seems to depend on the level of another.

- Cause: OFAT methodology, which by design cannot detect interactions between variables.

- Solution:

- Adopt a multivariate approach: Use a DoE that is specifically designed to estimate interaction effects [1].

- Visualize with ML-generated heatmaps: Train an ML model on your experimental data to generate multi-dimensional heatmaps. These visualizations can reveal how factors interact to affect the outcome, guiding you toward the global optimum [1].

Comparison of Optimization Approaches

The table below summarizes the key differences between traditional and modern data-driven optimization methodologies.

| Feature | Traditional OFAT / Intuition | ML-Driven DoE Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Search | Sequential, narrow focus [1] | Simultaneous, broad exploration of multi-factor space [1] |

| Factor Interactions | Cannot be detected [1] | Explicitly identified and modeled [1] |

| Data Efficiency | Low; many experiments for limited information [1] | High; maximizes information gain from each experiment [1] [7] |

| Underlying Principle | Experience-based judgment, trial-and-error [2] [7] | Pattern recognition in multi-dimensional data, predictive algorithms [1] [6] |

| Handling Complexity | Struggles with complex, non-linear systems [1] | Excels at modeling complex, non-linear relationships [1] [6] |

| Output | A single "best" point based on tested conditions | A predictive model of the entire parameter space and a quantified optimal point [1] |

Experimental Protocol: DoE + ML for Reaction-to-Device Optimization

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing a macrocyclisation reaction for organic light-emitting device performance [1].

1. Define Factors and Levels

- Select factors known to influence the reaction outcome. In the cited study, five factors were chosen: equivalent of Ni(cod)2 (M), dropwise addition time (T), final concentration (C), % content of bromochlorotoluene (R), and % content of DMF in solvent (S) [1].

- Define three levels for each factor (e.g., Low, Medium, High) [1].

2. Design the Experiment Array

- Select an appropriate DoE array, such as Taguchi's orthogonal array (e.g., L18), to define the set of experimental conditions that need to be run [1].

3. Execute Experiments and Measure Outcomes

- Carry out all reactions in the designed array under the specified conditions.

- Perform a standard workup (e.g., aqueous workup, short-path silica gel column) to obtain the crude raw material for testing [1].

- Fabricate the test device (e.g., a double-layer OLED via spin-coating and sublimation) using the crude material [1].

- Measure the performance metric of interest (e.g., External Quantum Efficiency - EQE) for each device in replicate [1].

4. Build and Validate the Machine Learning Model

- Correlate the reaction condition factors (M, T, C, R, S) with the performance outcome (EQE) using ML methods.

- Test different ML algorithms (e.g., Support Vector Regression (SVR), Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)) [1].

- Validate the models using a method like Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) and select the best performer based on the lowest Mean Square Error (MSE) [1].

- Use the chosen model (e.g., SVR) to predict performance across the entire parameter space and identify the theoretical optimum [1].

5. Confirm Optimal Conditions

- Run a validation experiment at the predicted optimal conditions.

- Compare the actual result with the model's prediction to confirm accuracy [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Taguchi's Orthogonal Arrays | A structured DoE table that allows for the efficient investigation of multiple process factors with a minimal number of experimental runs [1]. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | A machine learning algorithm used for regression analysis. It was found to be an effective predictor for correlating reaction conditions with device performance in a cited study [1]. |

| Crude Raw Material Mixtures | Using unpurified reaction products directly in device fabrication. This can bypass energy-intensive purification and, as demonstrated, sometimes yield superior performance than purified single compounds [1]. |

| AutoRXN | A mentioned example of a free, Bayesian algorithm-based tool that can assist in planning reaction optimization experiments by learning from results and suggesting subsequent conditions to test [7]. |

| Carpinontriol B | Carpinontriol B, MF:C19H20O6, MW:344.4 g/mol |

| Isoedultin | Isoedultin, MF:C21H22O7, MW:386.4 g/mol |

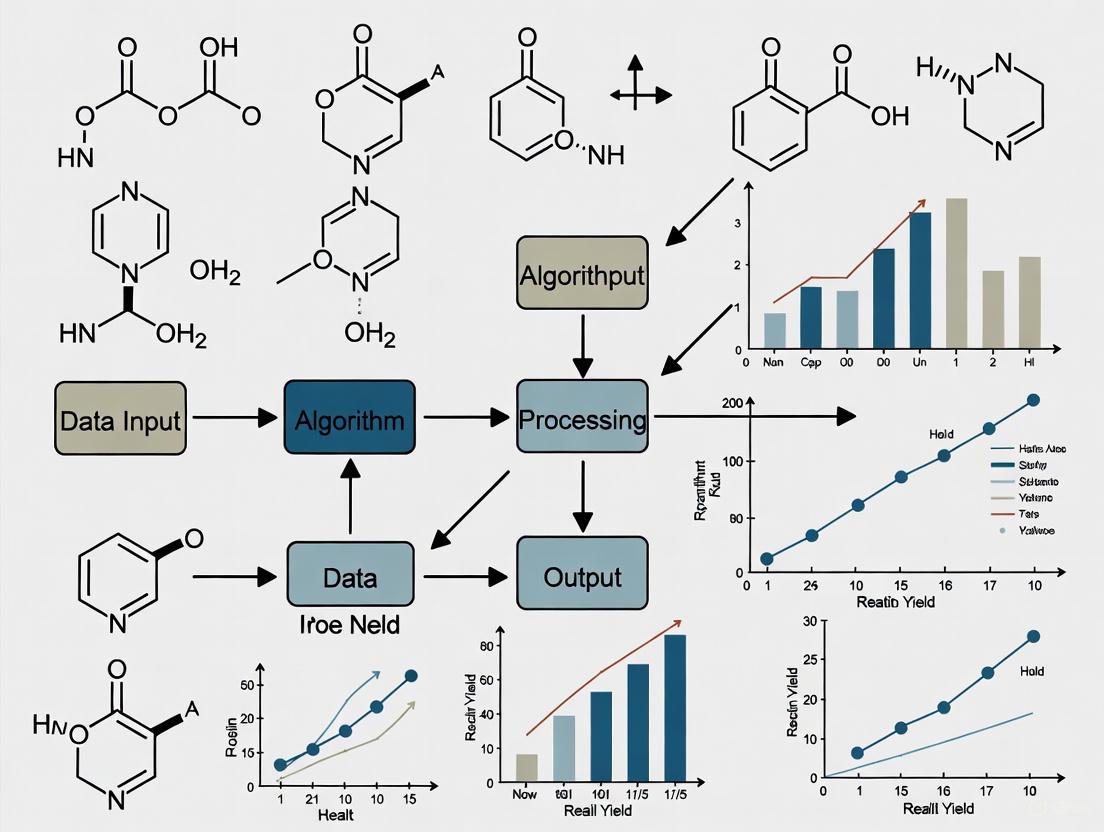

Workflow: OFAT vs. DoE+ML

DoE+ML Optimization Process

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between traditional Design of Experiments (DoE) and Bayesian Optimization?

Traditional DoE relies on a pre-determined mathematical model (e.g., linear or polynomial) and a fixed set of experiments from the start. This can create a bias that may not reflect the true system dynamics and offers limited flexibility to adapt to new findings. In contrast, Bayesian Optimization (BO) is an adaptive, sequential model-based approach. It uses a probabilistic surrogate model (like a Gaussian Process) to approximate the complex, unknown system. After each experiment, the model is updated with new data, and an acquisition function intelligently selects the next most promising experiment. This creates a "learn as we go" process that dynamically balances the exploration of new regions with the exploitation of known high-performance areas, leading to faster convergence with fewer experiments [8] [9].

2. My Bayesian Optimization process is converging slowly. Is the issue with my surrogate model or my acquisition function?

Slow convergence can be linked to both components. First, check your Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model. The choice of kernel and its hyperparameters (length scale, output scale) is critical. An inappropriate kernel for your response surface can lead to poor predictions. The hyperparameters are typically learned by maximizing the marginal likelihood of the data [9] [10]. Second, your acquisition function might be unbalanced. If it is too exploitative, it can get stuck in a local optimum. If it is too explorative, it wastes resources on unpromising areas. You can experiment with different acquisition functions or use a strategy that dynamically chooses between them [11] [12].

3. How do I choose the right acquisition function for my reaction yield optimization problem?

The choice depends on your primary goal. The table below summarizes common acquisition functions and their best-use cases [11] [9].

| Acquisition Function | Primary Mechanism | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Balances the probability and amount of improvement over the current best. | A robust, general-purpose choice for most problems, including reaction yield optimization [11] [13]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Maximizes the probability of improving over the current best. | Quickly finding a local optimum, but can be overly exploitative. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Uses a parameter (κ) to explicitly balance mean prediction (exploitation) and uncertainty (exploration). | Problems where you want direct control over the exploration-exploitation trade-off. |

| EI-hull-area/volume (Advanced) | Prioritizes experiments that maximize the area/volume of the predicted convex hull. | Complex multi-component systems (e.g., alloys, drug formulations) to efficiently explore the entire composition space [11]. |

4. Can I use Bayesian Optimization for problems with more than just a few parameters?

Yes, but with considerations. While BO is most prominent in optimizing a small number of continuous parameters (e.g., temperature, concentration), it can be applied to higher-dimensional problems and discrete parameters (e.g., catalyst type, solvent choice). However, performance may degrade in very high-dimensional spaces (>20 parameters) as the model's uncertainty estimates become less reliable. For problems with categorical variables, specific kernel implementations are required to handle them effectively [14] [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Poor Results from the Gaussian Process Model

Symptoms: The GP model's predictions do not match the experimental validation data, or the uncertainty estimates (confidence intervals) are unreasonably wide or narrow.

Solutions:

- Check and Preprocess Input Data: Ensure your input variables (e.g., temperature, flow rate) are normalized. GP performance can be sensitive to the scale of the inputs.

- Inspect the Kernel Function: The kernel defines the smoothness and patterns of the functions the GP can model.

- The Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel assumes smooth, infinitely differentiable functions [9].

- The Matérn kernel (particularly with ν=5/2) is a less rigid alternative that can better handle rougher, more complex response surfaces common in chemical reactions [9].

- If your data is noisy, add a White Noise kernel to the base kernel to account for experimental error [10].

- Re-optimize Hyperparameters: The kernel has hyperparameters (length scales, output scale) that must be fitted to your data. Use maximum likelihood estimation to optimize them. Most GP software libraries perform this automatically during model fitting [10].

Problem: The Optimization Gets Stuck in a Local Maximum

Symptoms: The algorithm repeatedly suggests experiments in a small region of the parameter space without discovering better yields elsewhere.

Solutions:

- Switch to a More Explorative Acquisition Function: If you are using Probability of Improvement (PI), try switching to Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), which are better at exploring uncertain regions [11].

- Adjust the Acquisition Function's Balance: For the UCB function, increase the κ parameter to give more weight to exploration (high uncertainty). Some libraries allow you to adjust a similar parameter in the EI function [13].

- Implement a Rollout Strategy: Advanced strategy that models the acquisition function selection as a sequential decision-making problem (Partially Observable Markov Decision Process), which can dynamically choose the best acquisition function at each step to improve long-term performance [12].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Optimizing Reaction Yield with Bayesian Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps to maximize reaction yield for a specific reaction step influenced by multiple factors, as demonstrated in a case study that reduced the need for experiments from 1,200 (full factorial) to a manageable subset [8].

1. Define the Problem and Design Space: * Objective: Maximize reaction yield (%). * Key Factors: Identify and define the ranges of continuous (e.g., temperature, flow rate, agitation rate) and categorical (e.g., solvent, reagent) variables.

2. Initial Experimental Design: * Use Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to select an initial set of 10-20 experiments. LHS ensures good coverage of the entire multi-dimensional design space, providing a robust foundation for the initial model [8].

3. Iterative Bayesian Optimization Loop: * a. Run Experiments: Conduct the experiments in the lab and record the yield for each condition. * b. Update the Gaussian Process Model: Fit the GP model using all data collected so far. The model will learn the relationships between your factors and the yield. * c. Optimize the Acquisition Function: Use an optimizer (like L-BFGS or an evolutionary algorithm) to find the set of conditions that maximizes the Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function [15]. * d. Select Next Experiment: The point suggested by the acquisition function is the next most informative experiment to run. * Repeat steps a-d until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., yield target is achieved, budget is exhausted, or improvements between iterations become negligible).

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Protocol 2: Advanced Strategy for Complex Systems (Convex Hull Search)

For problems involving the discovery of stable material compositions or multi-component drug formulations, the goal is often to map the convex hull of the system. A specialized acquisition function called EI-hull-area/volume has been shown to reduce the number of experiments needed by over 30% compared to traditional genetic algorithms [11].

1. Initialization: * Start with an initial dataset of computed or measured formation energies for a set of configurations.

2. Model and Acquisition: * Fit a Bayesian-Gaussian model (like Cluster Expansion) to the data. * Instead of a standard EI, use the EI-hull-area function. This function scores and ranks batches of experiments based on their predicted contribution to maximizing the area (or volume) of the convex hull. This prioritizes experiments that explore a wider range of compositions [11].

3. Convergence: * The process converges when the ground-state line error (GSLE)—a measure of the difference between the current and target convex hull—is minimized.

The quantitative performance of different acquisition functions for this task is shown below [11]:

| Acquisition Strategy | Key Metric: Ground-State Line Error (GSLE) | Number of Observations after 10 Iterations | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA-CE-hull) | Higher than EI-hull-area | ~77 | Traditional method, requires more user interaction. |

| EI-global-min | Highest (slows after 6 iterations) | 87 | Can miss on-hull structures at extreme compositions. |

| EI-below-hull | Comparable to GA-CE-hull | 87 | Prioritizes based on distance to the observed hull. |

| EI-hull-area (Proposed) | Lowest | ~78 | Most efficient, best performance with fewest resources. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details essential computational and methodological "reagents" for implementing Bayesian Optimization in reaction yield or materials development projects.

| Tool / Component | Function / Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A non-parametric probabilistic model used as the surrogate to approximate the unknown objective function and quantify prediction uncertainty [9] [10]. | Often used with a constant prior mean and a Matérn (ν=5/2) or RBF kernel. Hyperparameters are learned by maximizing the marginal likelihood. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that balances the probability of improvement and the magnitude of that improvement, making it a strong general-purpose choice [11] [13]. | A standard, robust option. Available in all major BO libraries (e.g., BoTorch, Scikit-learn). |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) | A statistical method for generating a near-random sample of parameter values from a multidimensional distribution. Used for the initial design of experiments [8]. | Superior to random sampling for covering the design space with fewer points. Use for the initial batch before starting the BO loop. |

| BoTorch / GPyTorch | Libraries for Bayesian Optimization and Gaussian Process regression built on PyTorch. Provide state-of-the-art implementations and support for modern hardware (GPUs) [10]. | Ideal for high-performance and research-oriented applications. Offers flexibility in modeling and acquisition function customization. |

| Matérn Kernel (ν=5/2) | A common kernel function for GPs that models functions which are twice differentiable, offering a good balance between smoothness and flexibility for modeling physical processes [9]. | A recommended default kernel over the RBF for many scientific applications, as it is less rigid. |

| Dregeoside Da1 | Dregeoside Da1, MF:C42H70O15, MW:815.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Clerodenoside A | Clerodenoside A, MF:C35H44O17, MW:736.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons for the failure of an ML-HTE integration project? Failure is often not due to the ML algorithm itself, but underlying organizational and data issues. The most common reasons include:

- Lack of a Solid Data Foundation: Attempting ML before establishing robust data engineering practices leads to the "garbage in, garbage out" principle. This occurs when data is fragmented, lacks unique identifiers, or is generally untrustworthy, forcing teams to spend most of their time creating workarounds instead of building models [16].

- No Clear Business Case: Projects are sometimes built because the technology is trendy, not because it solves a real, valuable problem. One team spent a year developing an LLM-powered assistant for a food delivery app, only to find it didn't address any actual user pain points and was abandoned after launch [16].

- Chasing Complexity Before Nailing the Basics: Management sometimes demands complex neural networks when simpler business rules or linear regression would suffice and perform better. Starting with simpler models provides faster insights and a more solid foundation for iteration [16].

FAQ 2: How can I detect and correct for systematic errors in my HTE data? Systematic errors, unlike random noise, can introduce significant biases that lead to false positives or false negatives in hit selection [17]. They can be caused by robotic failures, pipette malfunctions, or environmental factors like temperature variations [17].

- Detection: The presence of systematic error can be visually identified by examining the hit distribution surface across well locations. In an ideal, error-free scenario, hits are evenly distributed. Clustering of hits in specific rows or columns indicates systematic bias [17]. Statistically, the Student's t-test is recommended to formally assess the presence of systematic error prior to applying any correction method [17].

- Correction: Several normalization methods are widely used to remove these artefacts. The choice of method depends on your experimental design and available controls [17].

Table 1: Common Normalization Methods for Correcting Systematic Error in HTE

| Method | Formula | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Percent of Control | ( \hat{x}{ij} = \frac{x{ij}}{\mu_{pos}} ) | When positive controls are available. |

| Control Normalization | ( \hat{x}{ij} = \frac{x{ij} - \mu{neg}}{\mu{pos} - \mu_{neg}} ) | When both positive and negative controls are available. |

| Z-score | ( \hat{x}{ij} = \frac{x{ij} - \mu}{\sigma} ) | For normalizing data within each plate using the plate's mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ). |

| B-score | ( B\text{-}score = \frac{r{ijp}}{MAD{p}} ) | A robust method using a two-way median polish to account for row and column effects, followed by scaling by the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) [17]. |

FAQ 3: Can I use ML for reaction optimization with only a small amount of experimental data? Yes, active learning strategies are specifically designed for this scenario. For example, the RS-Coreset method uses deep representation learning to guide an interactive procedure that approximates the full reaction space by strategically selecting a small, representative subset of reactions for experimental evaluation [18]. This approach has been validated to achieve promising prediction results for yield by querying only 2.5% to 5% of the total reaction combinations in a space [18].

FAQ 4: What is a scalable ML framework for multi-objective optimization in HTE? Frameworks like Minerva are designed for highly parallel, multi-objective optimization. They address the challenge of exploring high-dimensional search spaces (e.g., with hundreds of dimensions) with large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) [19]. The workflow uses Bayesian optimization with scalable acquisition functions like q-NParEgo and Thompson sampling with hypervolume improvement (TS-HVI) to efficiently balance the exploration of new reaction conditions with the exploitation of known high-performing areas [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance and Unreliable Predictions

- Symptoms: Your ML model fails to predict reaction outcomes accurately, even when the training data seems sufficient.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Disconnect between ML teams and domain experts. The model may be technically sound but solves the wrong problem or uses misaligned metrics [16].

- Solution: Foster continuous collaboration between data scientists and chemists. Ensure ML metrics are directly aligned with true business objectives (e.g., optimize for retention, not just initial conversion) [16].

- Cause: Ignoring MLOps. Deploying models without a system for versioning, monitoring, and retraining leads to brittle, unmaintainable solutions that fail when the original developer leaves [16].

- Solution: Invest early in MLOps practices to create a stable, scalable, and sustainable ML culture. This includes establishing processes for model tracking, deployment, and continuous integration [16].

Issue 2: Inefficient Exploration of the Reaction Space

- Symptoms: Your HTE campaigns are not finding optimal conditions quickly, wasting resources on uninformative experiments.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Relying solely on intuition-driven or grid-based (one-factor-at-a-time) screening, which can overlook important regions of the chemical landscape [19].

- Solution: Implement a Bayesian optimization workflow. This involves [19]:

- Initial Sampling: Use quasi-random Sobol sampling to diversely cover the reaction condition space.

- Model Training: Train a model (e.g., Gaussian Process regressor) on the collected data to predict outcomes and their uncertainties.

- Acquisition Function: Use an acquisition function to select the next batch of experiments that best balance exploration and exploitation.

- Protocol: A standard Bayesian optimization cycle involves running the initial batch, training the model, using the acquisition function to select the next batch of experiments, and then repeating the process until convergence or budget exhaustion [19].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Active Learning with RS-Coreset for Small-Scale Data

This protocol is designed for predicting reaction yields with a minimal number of experiments [18].

- Reaction Space Definition: Predefine the scopes of reactants, products, additives, catalysts, and other relevant components to construct the full reaction space.

- Initial Random Selection: Select a small set of reaction combinations uniformly at random or based on prior literature knowledge.

- Iterative Cycle: Repeat the following steps for a set number of iterations or until prediction performance stabilizes:

- Step 3.1 - Yield Evaluation: Perform the experiments on the selected reaction combinations and record the yields.

- Step 3.2 - Representation Learning: Update the model's representation of the reaction space using the newly obtained yield information.

- Step 3.3 - Data Selection: Based on a maximum coverage algorithm, select a new set of reaction combinations that are the most instructive to the model for the next iteration.

Diagram 1: RS-Coreset Active Learning Workflow

Protocol 2: Scalable Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (Minerva Framework)

This protocol is for large-scale, automated HTE campaigns optimizing for multiple objectives like yield and selectivity simultaneously [19].

- Define Combinatorial Space: Represent the reaction condition space as a discrete set of plausible conditions, automatically filtering out impractical or unsafe combinations (e.g., temperature exceeding solvent boiling point).

- Initial Batch with Sobol Sampling: Select the first batch of experiments using Sobol sampling to maximize diversity and coverage of the reaction space.

- ML-Driven Optimization Cycle:

- Step 3.1 - Run Experiments: Execute the batch of reactions using HTE automation.

- Step 3.2 - Train Model: Train a multi-output Gaussian Process regressor on all collected data to predict outcomes and uncertainties for all possible conditions.

- Step 3.3 - Select Next Batch: Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to select the next batch of experiments that promises the greatest hypervolume improvement.

- Step 3.4 - Iterate: Repeat until objectives are met, performance converges, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Diagram 2: Minerva Multi-Objective Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an ML-Driven HTE Campaign

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Library | Substances that accelerate the chemical reaction. Different catalysts can dramatically alter yield and selectivity. | A library of Nickel (Ni) or Palladium (Pd) catalysts for cross-coupling reactions, such as Suzuki or Buchwald-Hartwig couplings [19]. |

| Ligand Library | Molecules that bind to the catalyst, modifying its activity and selectivity. Often the most critical variable. | A diverse set of phosphine or nitrogen-based ligands screened to find the optimal combination with a non-precious metal catalyst like Nickel [19]. |

| Solvent Library | The medium in which the reaction occurs. Solvent properties can affect reaction rate, mechanism, and outcome. | A collection of common organic solvents (e.g., DMSO, THF, Toluene) screened for optimal performance under green chemistry guidelines [19]. |

| Additives / Bases | Chemicals used to adjust reaction conditions, such as pH or to facilitate specific reaction pathways. | Various inorganic or organic bases (e.g., K2CO3, Et3N) tested to optimize the yield of a biodiesel production process [20]. |

| Positive Controls | Substances with known, strong activity. Used for data normalization and quality control. | Included on each plate to detect plate-to-plate variability and for normalization methods like "Percent of Control" [17]. |

| Negative Controls | Substances with known, no activity. Used to determine background noise and for normalization. | Used alongside positive controls in normalization formulas to correct for systematic measurement offsets [17]. |

| Verbenacine | Verbenacine, MF:C20H30O3, MW:318.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Paniculoside II | Paniculoside II, MF:C26H40O9, MW:496.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the pursuit of efficient drug discovery and sustainable chemical processes, the traditional focus on maximizing reaction yield is no longer sufficient. Modern research and industrial applications demand a holistic approach that simultaneously balances multiple critical objectives, including product selectivity, economic cost, and environmental sustainability.

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) frameworks provides a powerful methodology to navigate these complex, and often competing, goals. This technical support center provides guidance on implementing these advanced strategies, addressing common challenges, and outlining detailed protocols to accelerate your research in this evolving field.

Core Concepts: ML-Driven Multi-Objective Optimization

What is Multi-Objective Optimization in Chemical Synthesis?

Multi-objective optimization involves finding a set of solutions that optimally balance two or more conflicting objectives. In chemical synthesis, this means that improving one performance metric (e.g., yield) might lead to the deterioration of another (e.g., cost or environmental impact) [21] [22].

Key Conflicting Objectives: The core challenge lies in managing trade-offs between:

- Reaction Yield: The amount of target product formed.

- Selectivity: The preference for forming the desired product over side products.

- Cost: Expenses related to raw materials, catalysts, energy, and time.

- Sustainability: Environmental impact, including energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [21].

The Pareto Front: The set of optimal trade-off solutions is known as the Pareto front. A solution is "Pareto optimal" if it is impossible to improve one objective without making at least one other objective worse. The goal of MOO is to discover this frontier of non-dominated solutions [22].

How Does Machine Learning Enable MOO?

Machine learning enhances MOO by creating accurate predictive models that replace or guide costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments.

- Predictive Modeling: ML models, such as CatBoost, graph neural networks (GNNs), or random forests, can be trained on high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data to predict key performance indicators (KPIs) like yield, selectivity, and energy consumption from reaction parameters [21] [23].

- Optimization as an Objective Function: Once trained, these ML models can serve as the objective functions within an MOO framework. Optimization algorithms, such as the Constrained Two-Archive Evolutionary Algorithm (C-TAEA) or Genetic Algorithms (GAs), then explore the parameter space to find the Pareto-optimal set of conditions [21].

- Virtual Screening: ML models can rapidly predict the outcomes for thousands of virtual reactions, allowing researchers to screen for promising candidate conditions or molecules before any wet-lab experimentation [23] [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for ML-MOO Experiments

FAQ 1: My ML model has high predictive accuracy for yield but performs poorly on selectivity and cost. What could be wrong?

This is often a data quality and feature engineering issue.

- Possible Cause: Imbalanced or Incomplete Data

- Solution: Ensure your training dataset is representative and has sufficient high-quality data for all target objectives. The dataset should cover a wide range of the experimental parameter space. For multi-objective data, confirm the correspondence between samples and all properties [22].

- Possible Cause: Suboptimal Feature Selection

- Solution: Re-evaluate your feature set (descriptors). Incorporate domain-knowledge descriptors relevant to cost (e.g., catalyst price) and sustainability (e.g., E-factor). Use feature selection methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or MIC (Maximum Information Coefficient) to identify the most impactful features for each objective [22].

- Possible Cause: Inappropriate Model Architecture

- Solution: For complex molecular data, consider switching to models designed for structured data, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), which can better capture structural information related to selectivity [23].

FAQ 2: The optimization algorithm converges on solutions that are not practically feasible in the lab. How can I improve this?

This indicates a disconnect between the computational model and experimental constraints.

- Possible Cause: Lack of Constraints in the Optimization

- Solution: Implement hard constraints within your MOO algorithm. For example, use the Constrained Two-Archive Evolutionary Algorithm (C-TAEA) to enforce practical limits, such as maximum allowable catalyst loading, a cap on solvent toxicity, or a maximum temperature threshold [21].

- Possible Cause: Model-Experiment Mismatch

- Solution: Refine your ML model with experimental feedback. Incorporate transfer learning to update the model with a small number of validation experiments conducted near the predicted Pareto front. This improves the model's accuracy in the most relevant regions [23].

- Possible Cause: Overfitting to Training Data

- Solution: Regularize your ML model and use cross-validation techniques (e.g., K-fold CV) to ensure it generalizes well to unseen data. Avoid using overly complex models for small datasets [22].

FAQ 3: How can I effectively visualize and select the single best solution from the Pareto front?

Choosing a final solution from the many Pareto-optimal options is a key step.

- Solution: Use Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Methods

- TOPSIS/SPOTIS: These methods identify the solution that is closest to the ideal solution and farthest from the worst-possible solution, based on your weighted preferences for each objective [21].

- Parallel Coordinate Plots: This visualization tool helps you explore high-dimensional trade-offs. Each objective is represented by a vertical axis, and each candidate solution is a line crossing each axis at its value. This allows for intuitive comparison and selection based on your priorities [21].

- Solution: Define a Scalarization Function

- Assign explicit weights to each objective (e.g., cost is 50% important, yield is 30%, and sustainability is 20%) and combine them into a single score. This transforms the MOO problem into a single-objective one, simplifying the final choice [22].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: ML-MOO for Hit-to-Lead Progression

This protocol, adapted from a recent study, outlines an integrated workflow for diversifying and optimizing lead compounds in drug discovery [23].

Objective: Accelerate the hit-to-lead phase by optimizing for binding potency (activity), favorable pharmacological profile (e.g., solubility, metabolic stability), and synthetic feasibility (cost).

Title: Hit-to-Lead Multi-Objective Optimization Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE):

- Perform a matrix of ~13,490 Minisci-type C–H alkylation reactions to build a comprehensive dataset.

- Systematically vary reactants, catalysts, solvents, and concentrations.

- Measure outcomes: reaction success, yield, and byproducts.

Data Curation & Feature Engineering:

- Compile data into a structured format (e.g., SURF format).

- Encode reactions and molecules using descriptors such as Structural, ECFP, and Reaction-mechanism based DFT descriptors (energy, charge, bond length) [24].

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Train a deep graph neural network on the HTE dataset.

- Use the model to predict the outcomes of a virtual library of 26,375 enumerated molecules.

Multi-Objective Optimization:

- Define objectives: maximize potency (pIC50), minimize predicted toxicity, and optimize synthetic yield.

- Use an evolutionary algorithm (e.g., C-TAEA) to search the virtual library for the Pareto-optimal set of compounds.

Candidate Selection & Validation:

- Apply the TOPSIS decision-making method to select 212 top candidates from the Pareto front.

- Synthesize and test 14 top-priority compounds.

- Validate with co-crystallization of ligands with the target protein (e.g., MAGL) to confirm binding modes.

Key Outcomes: This workflow resulted in compounds with subnanomolar activity, representing a potency improvement of up to 4500 times over the original hit compound [23].

Quantitative Data from Case Studies

Table 1: Performance of ML-MOO in Different Industrial Applications

| Industry/Application | ML Model Used | Optimization Objectives | Optimization Algorithm | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Mining [21] | CatBoost (tuned with Grey Wolf Optimizer) | Ore processed, Energy consumed, Cost, GHG emissions | Constrained Two-Archive Evolutionary Algorithm (C-TAEA) | R² of 0.978 for predicting GHG emissions intensity; Identified best trade-offs for energy & emissions. |

| Hit-to-Lead Drug Discovery [23] | Deep Graph Neural Networks | Potency, Pharmacological profile, Synthetic feasibility | Evolutionary Algorithm (unspecified) | 4500-fold potency improvement; 14 compounds with subnanomolar activity developed. |

| Reaction Modeling [24] | Random Forest, XGBoost, GCNs | Reaction Yield, Impurity/Side products | Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Enabled virtual screening; eliminated low-yield reactions from wet-lab testing, saving cost and time. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for ML-MOO Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Kits | Rapidly generate large, consistent datasets for ML model training. | Miniaturized reaction blocks with pre-dispensed reagents covering a wide matrix of conditions [23]. |

| Specialized DNA Polymerases | Amplify DNA templates for molecular biology applications in R&D. | Hot-start polymerases to prevent nonspecific amplification; High-fidelity polymerases (e.g., Q5, Phusion) to minimize replication errors [25] [26]. |

| PCR Additives & Co-solvents | Modify reaction conditions to optimize specificity and yield for difficult targets (e.g., GC-rich templates). | DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M), GC Enhancer. Help denature secondary structures [25] [27]. |

| Molecular Purification Kits | Remove PCR inhibitors (e.g., phenol, EDTA, salts) to ensure high template quality. | Silica membrane-based kits (e.g., NucleoSpin) or drop dialysis for rapid desalting and cleanup [28]. |

| DFT Computational Pipeline | Calculate quantum mechanical descriptors for reaction modeling. | Generates reaction-mechanism based parameters (energy, charge, bond-length) for use as features in ML models [24]. |

| Ganoderenic acid F | Ganoderenic acid F, MF:C30H38O7, MW:510.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Jacquilenin | Jacquilenin, MF:C15H18O4, MW:262.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Visualization: The Pareto Front for Decision-Making

Understanding the Pareto front is critical for making informed trade-offs. The diagram below illustrates the concept for two conflicting objectives.

Title: Pareto Front of Two Conflicting Objectives

Explanation:

- The blue line (P1-P5) represents the Pareto front. Any solution on this line is "non-dominated." For example, moving from P3 to P4 improves Objective 1 (e.g., Yield) but worsens Objective 2 (e.g., Sustainability).

- The red points (D1-D3) are "dominated solutions." Solution D1 is worse than solutions on the front because you can move to P4 and improve on both objectives simultaneously.

- The final choice along the Pareto front depends on the researcher's priorities, which can be quantified using decision-making methods like TOPSIS [21].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What machine learning approaches can I use to predict Transition State geometries, especially when I don't have a large dataset?

For predicting Transition State (TS) geometries, two main ML strategies are effective, particularly in low-data scenarios:

- Group Contribution Methods: This approach uses a hierarchical tree of molecular groups to predict key inter-atomic distances at the TS. The distances are estimated by summing contributions from molecular groups present in the reactants, and the full 3D geometry is constructed using distance geometry. This method has been successfully applied to hydrogen abstraction reactions, with root-mean-squared errors for reaction center distances as low as 0.04 Ã… when sufficient training data is available [29].

- Bitmap Representation with CNN: A more recent method converts 3D molecular information into 2D bitmap images. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), such as a ResNet50 architecture, is then trained to assess the quality of TS initial guesses. This visual approach, combined with a genetic algorithm to evolve the best structures, has achieved verified TS optimization success rates of 81.8% for hydrofluorocarbons and 80.9% for hydrofluoroethers in hydrogen abstraction reactions [30].

FAQ 2: My TS geometry optimization fails repeatedly. How can I generate a better initial guess?

Failed optimizations are often due to poor-quality initial guesses. You can use the following workflow, which leverages machine learning, to generate improved initial structures for the TS optimizer in your quantum chemistry software.

FAQ 3: How can I accurately predict kinetic parameters like rate constants for a new reaction?

A robust strategy involves using quantum chemical calculations to obtain molecular-level properties and then feeding these into a machine learning model. This hybrid approach was used to quantitatively predict all rate constants and quantum yields for Multiple-Resonance Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence (MR-TADF) emitters [31].

- Objective: Predict all rate constants (e.g., kRISC, kF) and quantum yields.

- Protocol:

- Quantum Chemical Calculations: Perform calculations to determine key molecular properties. The following table details the critical computed parameters [31]:

| Computed Parameter | Symbol | Role in Kinetic Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Differences | ΔE(T1→S1), ΔE(T2→S1) | Dictate the thermodynamic driving force for transitions like RISC. |

| Spin-Orbit Coupling | SOC(S1–T2) | Governs the rate of intersystem crossing between singlet and triplet states. |

| Transition Dipole Moment | Correlates with the radiative decay rate constant (k_F). |

FAQ 4: I have a limited experimental budget. How can I map a large reaction space to predict yields?

Active learning strategies are designed for this exact scenario. The RS-Coreset method is an efficient tool that uses deep representation learning to guide an interactive procedure for exploring a vast reaction space with very few experiments [18].

- Objective: Predict yields across a large reaction space using a small subset of experiments.

- Protocol:

- Initial Random Sampling: Start by running a small, random set of experiments (e.g., 2.5% of the reaction space) [18].

- Iterative Active Learning Loop: Repeat the following steps:

- Update Model: Train or update a yield-prediction model using all data collected so far.

- Select Informative Experiments: Use the RS-Coreset algorithm to select the next batch of reaction conditions that are most informative for the model, maximizing the coverage of the reaction space.

- Run Experiments: Perform experiments on the selected conditions and record yields.

- Final Prediction: After a few iterations (e.g., using only 5% of the total possible reactions), the model can provide a reliable yield prediction for the entire reaction space [18].

FAQ 5: How do I ensure my ML-predicted reaction pathway is physically plausible?

To ensure physical plausibility, use models that incorporate fundamental physical constraints. The FlowER model is a generative AI approach that explicitly conserves mass and electrons [32].

- Core Principle: The model uses a bond-electron matrix (a method from the 1970s) to represent electrons in a reaction. Non-zero values in the matrix represent bonds or lone electron pairs.

- Why it Works: This representation forces the model to track all chemicals and how they are transformed throughout the reaction, preventing the generation of pathways that violate the law of conservation of mass [32]. This is a key limitation of models that treat atoms like tokens in a language model, which can sometimes "create" or "delete" atoms [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and methodologies referenced in this guide for predicting reaction fundamentals.

| Tool / Method | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Group Additive Model [29] | Algorithm | Predicts inter-atomic distances at the transition state by summing contributions from molecular groups. |

| Bitmap/CNN Model [30] | Machine Learning Model | Evaluates the quality of transition state initial guesses from a 2D bitmap representation of molecules. |

| Quantum Chemical Calculations [31] | Computational Method | Provides fundamental molecular properties (energies, couplings) for kinetic parameter prediction. |

| FlowER [32] | Generative AI Model | Predicts realistic reaction pathways and products while conserving mass and electrons. |

| RS-Coreset [18] | Active Learning Algorithm | Guides efficient sampling of a large reaction space to predict yields with minimal experiments. |

| Minerva [19] | ML Optimization Framework | Enables highly parallel, multi-objective optimization of reaction conditions using Bayesian optimization. |

| Carmichaenine C | Carmichaenine C, MF:C30H41NO7, MW:527.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hortein | Hortein, MF:C20H12O6, MW:348.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

ML in Action: Algorithms, Workflows, and Real-World Applications in Pharma

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Minerva ML framework in the context of chemical reaction optimization? Minerva is a scalable machine learning framework designed for highly parallel, multi-objective reaction optimization integrated with automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE). It uses Bayesian optimization to efficiently navigate large, high-dimensional reaction spaces, handling batch sizes of up to 96 reactions at a time and complex search spaces with over 500 dimensions. It is particularly useful for tackling challenges in non-precious metal catalysis and pharmaceutical process development [19].

Q2: My ML model's yield predictions are inaccurate when exploring new chemical spaces. How can I improve this? Inaccurate predictions often occur due to sparse, high-yield-biased data. To address this [33]:

- Employ a Subset Splitting Training Strategy (SSTS): This method can significantly boost model performance, as demonstrated by an increase in R² value from 0.318 to 0.380 on a challenging Heck reaction dataset [33].

- Utilize Informative Molecular Features: Prioritize molecular environment features like Morgan Fingerprints, XYZ coordinates, and other 3D descriptors around reactive functional groups. These have been shown to boost model predictivity more effectively than bulk material properties such as molecular weight or LogP [34].

Q3: How does Minerva handle the optimization of multiple, competing reaction objectives? Minerva employs scalable multi-objective acquisition functions to balance competing goals, such as maximizing yield while minimizing cost. Key functions include [19]:

- q-NParEgo: A scalable approach for parallel batch optimization.

- Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI): Efficiently balances exploration and exploitation.

- q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI): An advanced function for handling noisy experimental data. These functions are designed to overcome the computational limitations of traditional methods, allowing for optimization across large parallel batches [19].

Q4: What are the best practices for designing an initial set of experiments for ML-guided optimization? Initiate your campaign with algorithmic quasi-random Sobol sampling [19]. This method selects initial experiments that are diversely spread across the entire reaction condition space, ensuring broad coverage. This maximizes the likelihood of discovering informative regions that contain optimal conditions, providing a robust data foundation for subsequent Bayesian optimization cycles [19].

Q5: Our optimization process is hindered by the "large batch" problem. How can we scale efficiently? The framework within Minerva is specifically engineered for highly parallel HTE. To scale efficiently [19]:

- Leverage the Discrete Condition Space: Frame the reaction space as a discrete combinatorial set of plausible conditions, which allows for automatic filtering of impractical combinations.

- Use Scalable Acquisition Functions: Implement functions like q-NParEgo or TS-HVI, which are designed to handle large batch sizes (e.g., 24, 48, or 96) without the exponential computational load of other methods [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Optimization Performance in High-Dimensional Spaces

Symptoms

- The optimization algorithm fails to identify high-yielding conditions even after several iterations.

- Results are consistently outperformed by traditional chemist-designed experiments.

Resolution Steps

- Review Search Space Definition: Ensure your reaction condition space is a discrete set of plausible conditions, which helps in automatically filtering out unsafe or impractical combinations (e.g., NaH in DMSO, temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [19].

- Validate Feature Representation: For categorical variables like ligands and solvents, confirm that they are converted into meaningful numerical descriptors. The choice of descriptor significantly impacts the model's ability to navigate the landscape [19] [34].

- Adjust the Acquisition Function: If optimizing for multiple objectives, consider switching to a more scalable acquisition function like q-NParEgo or TS-HVI, which are better suited for large batch sizes and high-dimensional spaces than other methods [19].

- Check for Chemical Noise: Benchmark the robustness of your workflow against emulated virtual datasets that incorporate chemical noise. This ensures the algorithm can handle the variability present in real-world laboratories [19].

Issue 2: ML Model Fails to Generalize from Literature or Sparse Data

Symptoms

- The model performs well on training data but poorly on new, external test sets.

- Learning ability is limited, with low R² values on test data.

Resolution Steps

- Apply Data Stratification: Use the Subset Splitting Training Strategy (SSTS). This involves dividing the data into meaningful subsets to tackle the challenges of sparse distribution and high-yield preference common in literature-based data sets [33].

- Feature Engineering: Move beyond simple features. Implement Feature Distribution Smoothing (FDS) and prioritize molecular environment features like Morgan Fingerprints and 3D descriptors, which have proven more effective for predicting outcomes in complex reactions like amide couplings [34].

- Model Selection: Evaluate a diverse set of algorithms. Studies on amide coupling reactions show that kernel methods and ensemble-based architectures typically perform significantly better than linear models or single decision trees for classification tasks like identifying ideal coupling agents [34].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Minerva ML Workflow for a 96-Well HTE Suzuki Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the application of the Minerva framework for optimizing a nickel-catalysed Suzuki reaction, exploring a search space of 88,000 conditions [19].

1. Experimental Design and Setup

- Objective: Simultaneously optimize yield and selectivity.

- Search Space: A discrete combinatorial set of 88,000 potential reaction conditions, defined by parameters such as reagents, solvents, catalysts, and temperatures deemed plausible by a chemist.

- Automation Platform: A 96-well HTE system for highly parallel reaction execution.

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Step 1 - Initial Sampling: Use Sobol sampling to select the first batch of 96 experiments. This ensures diverse and widespread coverage of the reaction condition space [19].

- Step 2 - Data Collection & Analysis: Execute the reactions in the HTE platform and analyze outcomes (e.g., via UPLC or GC) to obtain yield and selectivity data for each condition.

- Step 3 - Machine Learning Cycle:

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all collected experimental data to predict reaction outcomes and their uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space [19].

- Next-Batch Selection: Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to evaluate all conditions and select the next most promising batch of 96 experiments based on the balance between exploration and exploitation [19].

- Step 4 - Iteration: Repeat Step 2 and Step 3 for as many iterations as needed, typically until performance converges, stagnates, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

3. Outcome Assessment

- Performance Metric: Calculate the hypervolume metric to quantify the quality of identified reaction conditions. This metric measures the volume of the objective space (yield, selectivity) dominated by the selected conditions, considering both convergence towards the optimum and diversity [19].

- Benchmarking: Compare the final hypervolume achieved by the ML workflow against conditions identified by traditional chemist-designed HTE plates [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative optimization process:

Protocol 2: ML-Guided Optimization for Palladaelectro-Catalyzed Annulation

This protocol details a data-driven approach for optimizing complex electrochemical reactions, which feature high dimensionality due to parameters like electrodes and applied potential [35].

1. Experimental Design

- Objective: Optimize the yield of a palladaelectro-catalyzed annulation reaction.

- Key Parameters: Electrode material, electrolyte, solvent, and applied potential/current.

- Design Strategy: An orthogonal experimental design is used to ensure diverse sampling and effective exploration of the high-dimensional synthetic space [35].

2. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Step 1 - Design of Experiments (DoE): Employ an orthogonal design to create a set of initial experiments that broadly and efficiently sample the multi-factor space.

- Step 2 - High-Throughput Experimentation: Carry out the designed experiments.

- Step 3 - Model Building and Prediction: Use the experimental data to train a machine learning model for yield prediction. The model utilizes physical organic descriptors to navigate the chemical space.

- Step 4 - Condition Identification: The trained model is used to efficiently identify ideal reaction conditions from the vast synthetic space [35].

The following table summarizes key quantitative benchmarks and results from the cited research on ML-guided optimization frameworks.

| Metric / Outcome | Value / Finding | Context / Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Batch Size | 96 reactions | Minerva HTE platform [19] |

| Search Space Dimensionality | 530 dimensions | Minerva in-silico benchmark [19] |

| Condition Space for Suzuki Reaction | 88,000 possible conditions | Minerva experimental campaign [19] |

| Best Identified Yield (AP) & Selectivity | 76% yield, 92% selectivity | Ni-catalysed Suzuki reaction via Minerva [19] |

| Performance vs. Traditional Methods | Outperformed two chemist-designed HTE plates | Minerva experimental campaign [19] |

| Model Performance Improvement (R²) | Increased from 0.318 to 0.380 using SSTS | Heck reaction yield prediction [33] |

| Top-Performing Model Types for Classification | Kernel methods and ensemble-based architectures | Amide coupling agent classification [34] |

| Process Development Time Acceleration | Reduced to 4 weeks from a previous 6-month campaign | Pharmaceutical process development with Minerva [19] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments, along with their primary functions in the optimization workflows.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Non-precious, earth-abundant metal catalyst used in Suzuki coupling; a focus for cost-effective and sustainable process development [19]. |

| Palladium Catalysts | Precious metal catalyst used in reactions like Buchwald-Hartwig amination; optimized for efficiency and selectivity in API synthesis [19]. |

| Uronium Salts (e.g., HATU) | Class of coupling agents for amide bond formation; ML models can classify and identify these as optimal for specific substrate pairs [34]. |

| Phosphonium Salts (e.g., PyBOP) | Class of coupling agents for amide bond formation; identified as optimal conditions through ML classification models [34]. |

| Carbodiimide Reagents (e.g., DCC) | Class of coupling agents for amide bond formation; a category predicted by ML models for certain reaction contexts [34]. |

| Electrode Materials | A key variable in electrochemical optimization (e.g., palladaelectro-catalysis); material choice significantly influences reaction yield and selectivity [35]. |

| Electrolyte Systems | Component in electrochemical reactions; its identity and concentration are critical parameters optimized by ML workflows [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO), when should I use q-NEHVI over other acquisition functions like q-EHVI or Thompson Sampling?

A1: You should use q-NEHVI (q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement) as your default choice in most experimental settings, especially when dealing with noisy observations or running experiments in parallel batches [36]. It is more efficient and scalable than q-EHVI for batch optimization (q > 1) and provides robust performance even in noiseless scenarios [37] [38].

Use q-EHVI primarily for small-batch or sequential (q=1) noiseless optimization, as its computational cost scales exponentially with batch size [19] [36]. Thompson Sampling variants are highly effective for best-arm identification problems, such as clinical trial adaptive designs, where the goal is to correctly identify the optimal treatment with high probability while minimizing patient regret [39].

Q2: My MOBO algorithm seems to be "stuck" and repeatedly suggests similar experimental conditions. What could be wrong?

A2: This is a common issue, often caused by:

- Inadequate Exploration: Your acquisition function might be over-exploiting. The "N" in q-NEHVI specifically helps mitigate this by integrating over the uncertainty of the observed Pareto front, preventing the algorithm from overfitting to noisy data points [36].

- Incorrect Reference Point: The reference point used for hypervolume calculation is critical. It should be set slightly worse than the minimum acceptable value for each objective. A poorly chosen reference point can distort the hypervolume improvement calculation and hinder exploration [38].

- High Noise Levels: In very noisy environments, the model struggles to distinguish signal from noise. Ensure your Gaussian Process model is correctly configured to account for observation noise [38].

Q3: How do I handle a mix of categorical (e.g., solvent, ligand) and continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) parameters in MOBO?

A3: This is a key challenge in chemical reaction optimization. A recommended approach is to treat the reaction condition space as a discrete combinatorial set [19]. This involves:

- Defining a finite set of plausible reaction conditions by combining all possible categorical and continuous parameters.

- Applying domain knowledge to filter out impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding a solvent's boiling point).

- Letting the BO algorithm search over this discrete set. The algorithm can effectively navigate this high-dimensional space to discover promising regions defined by the categorical variables before refining continuous parameters [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Algorithm Performance in High-Dimensional or Large-Batch Scenarios

Symptoms:

- Slow convergence in search spaces with many parameters (e.g., >10 dimensions).

- Intractable computation times when suggesting a new batch of experiments (e.g., for a 96-well plate).

Solution: Adopt scalable algorithms and workflows designed for high-throughput experimentation.

- Algorithm Selection: For large batch sizes (e.g., 48 or 96), use scalable acquisition functions like q-NParEGO, Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI), or q-NEHVI, which have better computational complexity than q-EHVI [19].

- Cached Box Decomposition: When using q-NEHVI, ensure you leverage its Cached Box Decomposition (CBD) feature. CBD scales polynomially with batch size, unlike the exponential scaling of the method used in q-EHVI [38].

- Baseline Pruning: Enable the

prune_baseline=Trueoption in q-NEHVI. This speeds up computation by ignoring previously evaluated points that have a near-zero probability of being on the Pareto front [38].

Table: Scalability of Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions

| Acquisition Function | Recommended Batch Size | Key Strength | Computational Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| q-NEHVI | Medium to Large (e.g., 4-96) | Handles noise, high scalability with CBD | Polynomial scaling with batch size [19] [38] |

| q-NParEGO | Medium to Large | Uses random scalarizations, highly scalable | Lower computational cost per batch [19] |

| TS-HVI | Medium to Large | Combines Thompson Sampling with HVI | Suitable for highly parallel HTE [19] |

| q-EHVI | Small (q=1) to Medium | Analytic gradients via auto-diff | Exponential scaling with batch size; use for small q [37] [19] |

Issue: Handling Multiple Competing Objectives Effectively

Symptoms:

- The algorithm finds solutions that are good for one objective but poor for another.

- Difficulty interpreting the trade-offs between objectives (e.g., yield vs. selectivity).

Solution: Focus on identifying the Pareto front, which represents the set of optimal trade-offs.

- Visualize the Pareto Front: Regularly plot the current non-dominated solutions during the optimization campaign. A good outcome is a diverse set of points along the front [40].

- Track Hypervolume: Use the hypervolume metric to quantitatively assess performance. It measures the volume of objective space dominated by the current Pareto front, balancing convergence and diversity. The goal is to maximize this value over iterations [19].

- Post-Optimization Analysis: After the campaign, use the set of Pareto-optimal conditions for further decision-making, selecting the one that best aligns with your project's priorities (e.g., maximizing yield at the cost of some selectivity) [40].

Table: Key Multi-Objective Performance Metrics

| Metric | Description | Interpretation in Reaction Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Hypervolume | Volume of objective space dominated by the Pareto front, relative to a reference point [19] [40]. | A higher value indicates a better and more diverse set of optimal reaction conditions. |

| Pareto Front | The set of solutions where improving one objective worsens another [37] [40]. | Represents the best possible trade-offs, e.g., between reaction yield and selectivity. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines a closed-loop workflow for optimizing chemical reactions, integrating Bayesian optimization with automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [19] [40].

Workflow for Autonomous Reaction Optimization

Initialize:

- Define all reaction parameters (categorical and continuous) and their bounds.

- Specify optimization objectives (e.g.,

maximize_yield,maximize_selectivity). - Set a reference point for hypervolume calculation based on the minimum acceptable performance for each objective [38].

Initial Data Collection:

- Use a space-filling design like Sobol sampling to select an initial set of diverse experiments. This maximizes the chance of finding promising regions of the chemical space early [19].

Model Training:

Candidate Selection:

Automated Execution & Analysis:

- Execute the proposed reactions using an automated HTE platform.

- Analyze the outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and update the central database [19].

Iteration:

- Repeat steps 3-5 until convergence (e.g., hypervolume plateaus) or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Conclusion:

- The final output is a Pareto front of optimal reaction conditions, allowing chemists to choose the best trade-off for their application [40].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Algorithm Performance

To evaluate the performance of a MOBO algorithm (e.g., q-NEHVI vs. baseline) in silico before running wet-lab experiments [19]:

- Obtain a Dataset: Use a historical dataset from a similar reaction, such as catalytic coupling screenings [19].

- Create an Emulator: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, GP) on this dataset to predict reaction outcomes. This model emulates the "ground truth" of the reaction landscape.

- Run Virtual Optimization Campaigns:

- Simulate the optimization loop: the algorithm suggests a batch of conditions, and the emulator provides the outcomes instead of a real experiment.

- Use different acquisition functions to compare their performance.

- Evaluate with Metrics:

- Track the hypervolume of the identified Pareto set over each iteration.

- Compare the final performance against the known optimum in the dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

This table details essential components for implementing a machine learning-driven reaction optimization campaign, as demonstrated in pharmaceutical process development case studies [19].

Table: Essential Components for an ML-Driven Optimization Campaign

| Item / Solution | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotic Platform | Enables highly parallel execution of numerous reactions (e.g., in 24, 48, or 96-well plates), providing the data throughput required for data-driven optimization [19]. |

| q-NEHVI Acquisition Function | The core algorithmic engine for selecting the next batch of experiments; efficiently balances multiple objectives and handles experimental noise in parallel settings [19] [36]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | A probabilistic machine learning model that predicts reaction outcomes and, crucially, quantifies the uncertainty of its predictions, which guides the exploration-exploitation trade-off [19]. |

| Discrete Combinatorial Search Space | A pre-defined set of plausible reaction conditions (combinations of solvents, ligands, catalysts, etc.), filtered by chemical knowledge, which the algorithm searches over [19]. |

| Hypervolume Performance Metric | A single quantitative measure used to track the progress and success of an optimization campaign, assessing both the quality and diversity of the identified Pareto-optimal conditions [19]. |

| Tsugaric acid A | Tsugaric acid A, MF:C32H50O4, MW:498.7 g/mol |

| Cyanidin 3-xyloside | Cyanidin 3-xyloside, MF:C20H19ClO10, MW:454.8 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can Machine Learning (ML) specifically reduce the costs associated with optimizing API synthesis routes? Machine learning reduces costs by accelerating the identification of viable synthetic pathways and predicting successful reaction conditions early in development. This minimizes reliance on lengthy, resource-intensive trial-and-error experiments in the lab. By using ML to predict synthetic feasibility, researchers can avoid investing in routes that are prohibitively complex or low-yielding, thereby reducing costly late-stage failures [41] [42].

2. My ML model for predicting reaction yields seems to perform well on training data but poorly on new substrates. Why is this happening and how can I fix it? This is often a problem of generalization capability, where the model fails to predict outcomes for molecules not represented in its training set. This can be addressed by using models and representations that capture more comprehensive chemical information. For instance, the ReaMVP framework, which incorporates both sequential (SMILES) and 3D geometric views of molecules through multi-view pre-training, has demonstrated superior performance in predicting yields for out-of-sample data, significantly enhancing model generalizability [43].

3. What are the key properties to predict for a new catalytic reaction to ensure it is not only high-yielding but also suitable for scale-up? To ensure a reaction is manufacturable, key properties to predict include:

- Reaction Yield: The primary indicator of efficiency [43].

- Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score: Estimates the ease of synthesis, typically on a scale from 1 (easy) to 10 (difficult) [41].

- Condition Optimality: The identification of robust parameters (catalyst, ligand, solvent, temperature) that work across multiple substrates [44] [45].

4. Are there fully autonomous laboratories (self-driving labs) being used for reaction optimization? Yes, self-driving laboratories (SDLs) are an emerging reality. These platforms integrate automation with artificial intelligence to autonomously conduct experiments, analyze data, and iteratively refine conditions. For example, one ML-driven SDL was able to rapidly optimize enzymatic reaction conditions in a five-dimensional parameter space, a task that is highly complex and time-consuming for humans. This approach significantly expedites the optimization process and improves reproducibility [45].

5. Why do traditional Bayesian optimization methods sometimes fail when using simple molecular descriptors? Traditional Bayesian optimization often depends on domain-specific feature representations (e.g., chemical fingerprints). When shifting domains or reaction types, the time-consuming feature engineering must be repeated, as descriptors for one system may not transfer effectively to another. This lack of generalizability can lead to poor performance [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor or Inconsistent Yields in Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig Amination

Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Ligand Selection or Catalyst Deactivation The choice of ligand is critical for stabilizing the active palladium catalyst and facilitating the reductive elimination step. Suboptimal selection can lead to low conversion and yield [44] [41].

- ML-Guided Solution:

- Use a Data-Driven Ligand Screening Tool: Employ machine learning models trained on high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data to predict ligand performance for your specific substrate combination. The GOLLuM framework, for instance, learns from experimental outcomes to organize its latent space, automatically clustering high-performing ligands and separating them from low-performing ones [44].

- Leverage Specialized Condition Predictors: Utilize graph neural networks or other ML models specifically trained to predict optimal catalytic systems (ligand and metal precursor) for C–N cross-coupling reactions [41].

Potential Cause 2: Unoptimized Reaction Parameters Subtle interactions between parameters like temperature, base strength, and solvent polarity can significantly impact yield. Navigating this high-dimensional space manually is inefficient [18].

- ML-Guided Solution:

- Implement Bayesian Optimization (BO): Use BO with a Gaussian Process surrogate model to efficiently explore the parameter space. This algorithm balances exploration of unknown conditions with exploitation of known high-yielding areas, finding the global optimum in fewer experiments [44] [45].

- Adopt an Active Learning Workflow: Start with a small set of initial experiments. Use an ML model like RS-Coreset to select the most informative subsequent experiments to run, iteratively updating the model to rapidly converge on optimal conditions with minimal experimental effort [18].

Problem: Low Yield and Selectivity in Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Cross-Coupling

Potential Cause: Competitive Side-Reactions and Homocoupling Nickel catalysis can be prone to side reactions such as homocoupling (bisarylation) or β-hydride elimination, which reduce the yield of the desired cross-coupled product.

- ML-Guided Solution:

- Predict and Model Side-Product Formation: Train machine learning models not only on yield but also on selectivity data. Models can learn to identify regions in the chemical parameter space where the risk of homocoupling is high and guide the optimization away from those conditions.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Frame the problem as a multi-task optimization where the algorithm simultaneously maximizes the cross-coupled product yield and minimizes the yield of key side products. This ensures the identified conditions are selective, not just high-converting.

Problem: ML Model for Yield Prediction Has a High Error Rate on New Data

Potential Cause: Model Overfitting or Inadequate Data Representation The machine learning model may have learned patterns from noise in the training data or from biased data that over-represents certain chemical classes, rather than the underlying chemistry [41].

- ML-Guided Solution:

- Apply Challenging Data Splits: Evaluate and train your model using stringent benchmark splits, such as splitting based on specific substrate scaffolds or functional groups (out-of-sample splits). This provides a more realistic assessment of generalizability than simple random splits [43].