Modern Design of Experiments for Organic Synthesis: Integrating AI, Automation, and Green Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies for optimizing organic synthesis.

Modern Design of Experiments for Organic Synthesis: Integrating AI, Automation, and Green Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies for optimizing organic synthesis. It explores the foundational shift from traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches to data-driven strategies leveraging high-throughput experimentation (HTE) and machine learning (ML). The content covers practical applications in drug development, troubleshooting common optimization challenges, and validation techniques for comparing traditional and advanced methods. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices to enhance efficiency, sustainability, and success rates in synthetic campaigns.

The Paradigm Shift: From Intuition to Data-Driven Experimentation

Limitations of Traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) Approaches

This application note details the fundamental limitations of the One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) approach within organic synthesis research. While historically prevalent, OVAT methodology presents significant constraints in efficiency, statistical rigor, and predictive capability when optimizing chemical reactions. Contemporary approaches utilizing Design of Experiments (DoE) and machine learning-driven optimization demonstrate superior performance for navigating complex parameter spaces, particularly in pharmaceutical development where efficiency and comprehensive process understanding are critical. This document provides a structured comparison of these methodologies, an experimental protocol highlighting their practical implications, and visual workflows to guide researchers in implementing advanced optimization strategies.

Critical Analysis of OVAT Limitations

The traditional OVAT approach, while intuitively simple, suffers from several fundamental limitations that hinder its effectiveness for modern organic synthesis optimization, especially when compared to multivariate methods like Design of Experiments (DoE) and machine learning (ML)-guided approaches.

Inability to Detect Factor Interactions

The most significant limitation of the OVAT method is its failure to capture interaction effects between variables [1]. In complex chemical systems, variables rarely act independently; the effect of one factor (e.g., temperature) often depends on the level of another (e.g., catalyst concentration). OVAT, by holding all other variables constant while varying one, is structurally blind to these critical interactions. This can lead to incorrect conclusions about a factor's importance and result in suboptimal reaction conditions [2]. Factorial designs within DoE, in contrast, systematically vary all factors simultaneously, enabling the quantification of these interactions and providing a more accurate model of the reaction system [3].

Statistical Inefficiency and Data Limitations

OVAT is notoriously data-inefficient [1]. It requires a large number of experiments to explore the same parameter space that a well-designed multivariate experiment can map with significantly fewer runs [4]. Furthermore, OVAT lacks proper statistical rigor as it does not allow for the estimation of experimental error across the entire design space. Without replication across the entire sequence, it is impossible to distinguish true factor effects from random noise [2]. Data generated from OVAT is also ill-suited for building predictive models, as it does not provide a balanced and orthogonal dataset covering the multi-dimensional design space [5].

Propensity for Finding Local Optima

The sequential nature of OVAT makes it highly prone to converging on local optima rather than the global optimum [4]. The path taken through the experimental space—which variable is optimized first—can lock the researcher into a region of moderate performance, missing potentially superior conditions elsewhere. A classic tutorial example demonstrates how OVAT identified a local yield maximum of 52.1%, while a simple factorial design found a superior condition with a yield of 56.1% within the same parameter bounds [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of OVAT versus DoE Performance Characteristics

| Characteristic | OVAT Approach | DoE/Multivariate Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of Interactions | Not possible [1] | Explicitly models and quantifies interactions [3] [2] |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires many runs for limited information [1] | High; more information per experiment [4] |

| Statistical Rigor | Low; lacks proper error estimation [1] | High; built-in estimation of error and significance [4] |

| Risk of Finding Optima | High risk of local optima [4] [2] | Effective navigation to global optimum [5] |

| Model Building | Poor; data not suited for predictive models [5] | Excellent; generates data for robust predictive models [1] [4] |

| Exploration of Parameter Space | Sequential and limited [2] | Comprehensive and systematic [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination Case Study

This protocol is adapted from a published study that directly compared OVAT and DoE for optimizing a Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination (CMRF) reaction, a critical process in Positron Emission Tomography (PET) tracer synthesis where efficiency is paramount due to the short half-life of isotopes [4].

Background and Objective

Objective: To systematically optimize the reaction conditions for the CMRF of an arylstannane precursor to produce 2-{(4-[¹â¸F]fluorophenyl)methoxy}pyrimidine-4-amine ([¹â¸F]pFBC) with the goal of maximizing Radiochemical Conversion (%RCC).

Challenge: This is a complex, multicomponent reaction with several continuous (temperature, time, stoichiometry) and discrete (solvent, base) variables that potentially interact. Initial OVAT optimization failed to yield satisfactory and reproducible synthesis performance for automation [4].

Methodology & Workflow Comparison

The core difference lies in the experimental sequence. The following diagram contrasts the fundamental workflows of the OVAT and DoE approaches.

Detailed Procedural Steps

Part A: Traditional OVAT Optimization (Ineffective Protocol)

- Initialization: Start with a set of baseline conditions (e.g., Solvent: DMF, Temperature: 100°C, Time: 10 min, Cu(OTf)₂(Py)₄: 5 µmol).

- Temperature Optimization: Hold all other variables constant. Perform reactions at 80, 100, 120, and 140°C. Determine that 120°C gives the highest %RCC. Lock temperature at 120°C.

- Reaction Time Optimization: With temperature locked at 120°C, vary time (5, 10, 15, 20 min). Determine 15 min is best. Lock time at 15 min.

- Catalyst Optimization: With temperature and time locked, vary catalyst amount. This sequential process fails to discover that the optimal temperature might be different if the catalyst amount or reaction time were also changed, likely leading to a suboptimal combination of conditions [4] [2].

Part B: DoE-Based Optimization (Recommended Protocol)

Screening Design:

- Objective: Identify the few critical factors from a large list of potential variables.

- Design: Select a Resolution III or IV Fractional Factorial Design.

- Execution: Perform a highly efficient set of 8-16 experiments where multiple factors (e.g., solvent type, temperature, time, catalyst load, base stoichiometry) are varied simultaneously according to the design matrix.

- Analysis: Use statistical analysis (e.g., Pareto charts) to identify temperature and catalyst load as the most significant factors influencing %RCC.

Optimization Design:

- Objective: Model the response surface and find the global optimum.

- Design: For the critical factors (temperature, catalyst load), select a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like a Central Composite Design (CCD).

- Execution: Perform the 13-experiment CCD, which includes factorial points, axial points, and center points (for error estimation).

- Analysis: Fit the data to a quadratic model. The model will reveal the nature of the effect of each factor and their interaction, allowing for the precise prediction of the combination of temperature and catalyst load that maximizes %RCC [4].

Anticipated Outcomes

- OVAT: The process is slow, data-inefficient, and highly likely to result in a set of conditions that are not the global optimum. The final understanding of the reaction system is limited.

- DoE: The process is faster and provides a comprehensive, quantitative model of the reaction. It will identify the true global optimum and reveal how factors interact, leading to more robust and reproducible reaction conditions for automated synthesis [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The transition from OVAT to advanced optimization methods relies on both physical tools and conceptual frameworks. The following table details key components of the modern synthesis optimization toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Reaction Optimization

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Role in Optimization |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Automated systems (e.g., Chemspeed, Unchained Labs) that use parallel reactors (e.g., 96-well plates) to rapidly execute the large number of experiments required for DoE and ML workflows with minimal human intervention [5]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | A class of machine learning algorithms that iteratively suggest the next most informative experiments by balancing exploration (probing uncertain regions) and exploitation (improving known good conditions), dramatically accelerating the search for optimal conditions [1]. |

| Factorial & Fractional Factorial Designs | The foundational experimental designs for DoE. They efficiently screen a large number of factors to identify the most influential ones, and are uniquely capable of detecting and quantifying interaction effects between variables [3] [4]. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Designs | Advanced experimental designs (e.g., Central Composite, Box-Behnken) used after screening to build a precise mathematical model of the reaction landscape. This model allows for accurate prediction of outcomes and location of the global optimum [4]. |

| Liquid Handling / Automation Modules | Robotic liquid handling systems are critical for ensuring the reproducibility and accuracy of small-volume reagent additions in HTE platforms, eliminating a major source of human error in data generation [5]. |

| In-line/Online Analytical Tools | Integrated analytics (e.g., HPLC, GC, IR) that provide rapid, automated analysis of reaction outcomes (yield, purity). This closed-loop data collection is essential for feeding results back to ML algorithms in real-time [5]. |

| Dafadine-A | Dafadine-A, MF:C23H25N3O3, MW:391.5 g/mol |

| Nitazoxanide-d4 | Nitazoxanide-d4, MF:C12H9N3O5S, MW:311.31 g/mol |

Integrated Optimization Workflow

Combining the principles of DoE with modern automation and machine learning creates a powerful, self-optimizing system for organic synthesis. The following diagram outlines this integrated, closed-loop workflow.

Core Principles of Modern Design of Experiments (DOE)

The modern framework of Design of Experiments (DOE) provides a systematic, efficient methodology for planning and conducting experimental investigations, thereby maximizing the knowledge gained from research while minimizing resource consumption. In the context of organic synthesis, this translates to the strategic optimization of chemical reactions—including the identification of ideal conditions for parameters such as temperature, concentration, and reaction time—to enhance yield, purity, and sustainability. Moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, modern DOE empowers researchers to explore complex factor interactions and build predictive models for chemical behavior. This is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, where rapid process optimization and scale-up are essential [6].

The core philosophy of DOE rests on several key principles: structured experimentation, where runs are deliberately planned to gather maximal information; multifactorial analysis, which allows for the simultaneous variation of multiple factors; and statistical robustness, ensuring that conclusions are reliable and reproducible. The integration of DOE with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) robotic platforms and machine learning (ML) algorithms, such as Bayesian Optimization (BO), represents the cutting edge of autonomous chemical research, enabling the accelerated discovery and optimization of synthetic routes under practical laboratory constraints [7].

Core Principles and Methodologies

Foundational Principles of DOE

Modern DOE is guided by a set of interdependent principles that ensure the efficiency and validity of experimental campaigns.

- Structured Experimentation vs. Random Testing: Unlike haphazard experimentation, DOE relies on pre-defined experimental matrices (designs) that systematically cover the factor space. This structure is what allows for the unambiguous attribution of observed effects to specific factors and their interactions.

- Multifactorial Analysis: A central tenet of DOE is the conscious variation of several factors at once. This approach not only saves time and resources but is the only way to detect and quantify interactions between factors—for instance, where the optimal level of one reagent depends on the concentration of another [6].

- Statistical Rigor and Reproducibility: DOE is grounded in statistical theory. Principles like randomization (running trials in a random order to mitigate the effects of lurking variables), replication (repeating experimental runs to estimate variability and improve precision), and blocking (grouping runs to account for known sources of noise, like different batches of starting material) are fundamental to ensuring that results are reproducible and not artifacts of uncontrolled experimental conditions [6].

Key Methodologies and Design Types

Different experimental goals call for specific design structures. The table below summarizes the primary DOE designs used in organic synthesis.

Table 1: Key DOE Designs and Their Applications in Organic Synthesis

| Design Type | Primary Objective | Key Characteristics | Typical Application in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial [6] | To study all possible combinations of factors and their interactions. | Comprehensive but can become large; for k factors at 2 levels, requires 2k runs. | Screening a small number (e.g., 2-4) of critical reaction parameters (e.g., solvent, catalyst, temperature) to understand their full influence. |

| Fractional Factorial [6] | To screen a larger number of factors efficiently when interactions are assumed to be limited. | Studies a carefully chosen fraction (e.g., 1/2, 1/4) of the full factorial design. | Initial screening of 5+ potential factors (e.g., reagents, ligands, additives) to identify the few most impactful ones for further optimization. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) [6] | To model curvature and find the optimal set of conditions (a "sweet spot"). | Uses designs with 3 or more levels per factor (e.g., Central Composite Design, Box-Behnken). | Fine-tuning reaction conditions (e.g., temperature and time) to maximize the yield of a key synthetic step after critical factors are identified. |

| Optimal Designs (D-, A-, I-optimal) [6] | To create highly efficient custom designs for complex constraints or pre-existing data. | Algorithms select design points to minimize prediction variance or the volume of a confidence ellipsoid. | Optimizing a reaction when the experimental region is irregular or when adding new runs to a pre-existing dataset. |

| Definitive Screening Designs [6] | To screen a moderate number of factors while retaining some ability to detect curvature. | Very efficient; requires only 2k+1 runs. Each factor is tested at three levels. | Rapidly screening 6-10 factors with minimal experimental effort to identify critical main effects and detect non-linear responses. |

The Integration of Machine Learning and Bayesian Optimization

A paradigm shift in modern DOE is the integration of machine learning to create closed-loop, self-optimizing systems. Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful active learning method particularly suited for optimizing noisy, expensive-to-evaluate functions, such as chemical reaction yields [7].

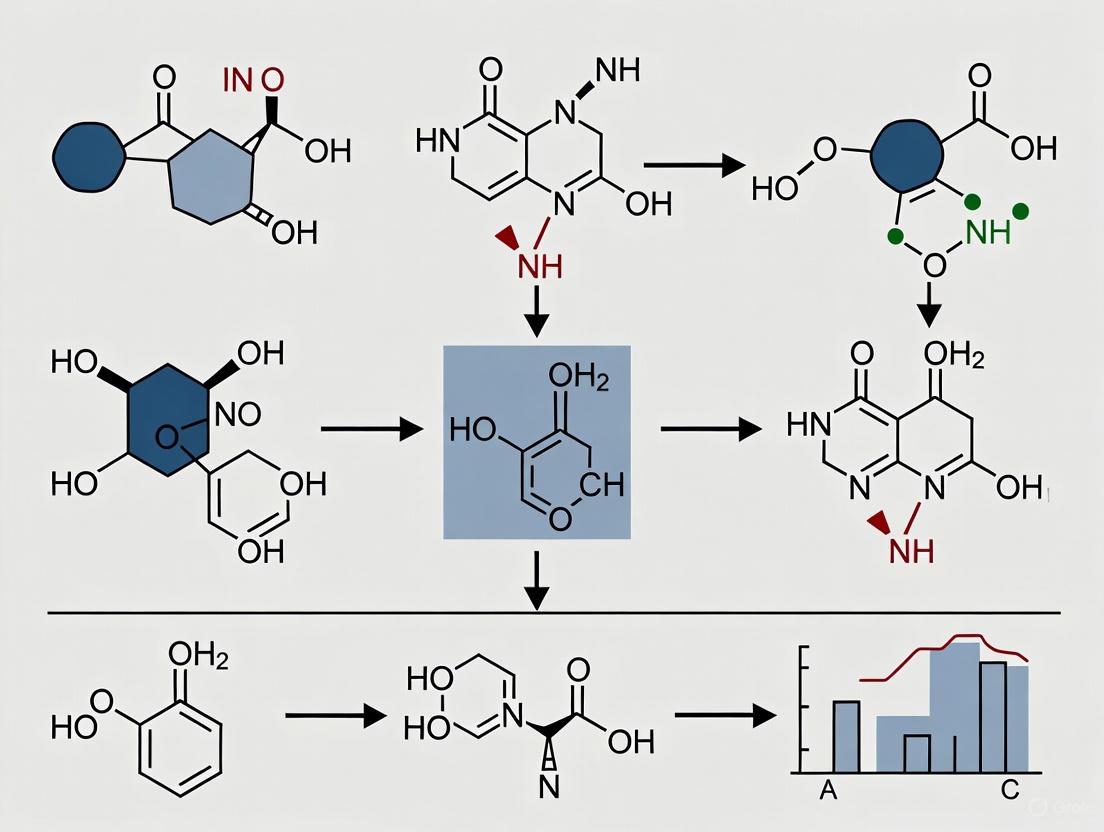

The BO workflow in organic synthesis involves several key stages, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Figure 1: Closed-loop workflow for Bayesian Optimization of chemical synthesis.

This iterative process is highly efficient. For instance, in the optimization of a sulfonation reaction for redox flow batteries, a BO framework successfully navigated a 4D parameter space (time, temperature, acid concentration, analyte concentration) and identified 11 high-yielding conditions (>90% yield) under mild temperatures, demonstrating the power of this modern approach [7].

Application Notes & Protocols

Case Study: Optimizing a Sulfonation Reaction with Flexible Batch BO

Objective: To autonomously optimize the sulfonation of a fluorenone derivative using a high-throughput robotic platform, maximizing product yield under mild conditions to minimize the use of fuming sulfuric acid [7].

Experimental Parameters & Ranges:

- Analyte Concentration: 33.0 - 100 mg mLâ»Â¹

- Sulfonating Agent (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„): 75.0 - 100.0%

- Reaction Time: 30.0 - 600 min

- Reaction Temperature: 20.0 - 170.0 °C

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Sulfonation Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorenone Analyte | The redox-active molecule to be functionalized. | Starting material; solubility is a key property being improved. |

| Sulfuric Acid | Sulfonating agent; introduces -SO₃⻠groups. | Concentration is a key variable; milder conditions are targeted. |

| Heating Blocks | Provide precise temperature control for reactions. | A practical constraint (3 blocks) influenced the batch BO design. |

| Liquid Handler | Automates the formulation of reaction mixtures. | Enables high-throughput and reproducible sample preparation. |

| HPLC System | Characterizes reaction outcomes and quantifies yield. | Provides the critical data (yield) for the Bayesian model. |

Protocol:

- Initialization: Generate 15 initial reaction conditions using a 4D Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to uniformly explore the parameter space [7].

- Hardware-Aware Clustering: Accommodate hardware constraints (only 3 heating blocks) by clustering the LHS-generated temperatures and assigning three centroid temperatures to the actual runs.

- High-Throughput Execution:

- Use a liquid handler to prepare reaction mixtures in parallel according to the 15 specified conditions, with three replicates per condition.

- Transfer samples to one of three heating blocks set to the assigned centroid temperatures.

- Automated Analysis: After the specified reaction time, transport samples to an HPLC system for automatic analysis. Calculate the percent yield based on the chromatogram peak areas.

- Decision-Making Loop:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model using the mean and variance of the yield from the replicates.

- Use a Batch Bayesian Optimization (BBO) algorithm with an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to suggest the next batch of 15 conditions. The algorithm employs strategies like post-BO clustering or temperature pre-selection to handle the hardware constraints.

- Repeat steps 3-5 until the yield is maximized or convergence is achieved.

Outcome: The flexible BO framework successfully identified optimal synthesis conditions, achieving high yields (>90%) while operating under milder temperatures, which reduces hazardous fuming and improves energy efficiency [7].

Case Study: Chemoselective Oxidation in Total Synthesis

Objective: To achieve chemoselective oxidation of a primary alcohol to an aldehyde in a complex molecule, without over-oxidation to the acid or epimerization of sensitive stereocenters [8].

Method: Piancatelli/Margarita Oxidation (IBD/TEMPO).

Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Dissolve the substrate containing the primary alcohol group in dichloromethane (DCM).

- Catalyst Addition: Add a catalytic amount (typically 1-10 mol%) of TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl) to the solution.

- Oxidant Addition: Add 1.1-1.5 equivalents of iodosobenzene diacetate (IBD) to the reaction mixture.

- Reaction Monitoring: Stir the reaction at room temperature and monitor by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) until the starting material is consumed.

- Work-up: Quench the reaction with a saturated sodium thiosulfate solution, extract with DCM, dry the organic layer over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude aldehyde using standard techniques like flash chromatography.

Key Considerations and Applications:

- Chemoselectivity: This protocol is highly selective for primary alcohols over secondary alcohols and tolerates a wide range of other oxidizable functional groups [8].

- Stereochemical Integrity: The mild conditions prevent epimerization at alpha-stereocenters, a critical advantage in the synthesis of chiral molecules like (+)-pumiliotoxin B [8].

- Industrial Application: The robustness of this method allows for scale-up. For example, Novartis Pharma performed this oxidation on a large scale during the synthesis of the anti-cancer agent (+)-discodermolide, noting that adding a small amount of water dramatically accelerated the reaction [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software and R Packages

The practical application of modern DOE relies heavily on statistical software. R, in particular, has a rich ecosystem of packages specifically for experimental design. The table below summarizes key packages as detailed in the CRAN Task View on Experimental Design [6].

Table 3: Essential R Packages for Design of Experiments (DoE)

| R Package | Primary Function | Use Case in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

DoE.base [6] |

Creation of full factorial designs and orthogonal arrays. | A foundational package for generating basic screening designs. |

FrF2 [6] |

Creation and analysis of regular and non-regular fractional factorial designs. | Efficiently screening a large number of factors to identify the few vital ones. |

rsm [6] |

Fitting and analysis of Response Surface Models (e.g., CCD, Box-Behnken). | Modeling curvature to find optimal reaction conditions. |

AlgDesign [6] |

Generation of D-, A-, and I-optimal designs. | Creating custom, resource-efficient designs for complex situations. |

daewr [6] |

Contains data sets and functions from Lawson's textbook; includes definitive screening designs. | Rapid screening with the ability to detect active second-order effects. |

skpr [6] |

A comprehensive toolkit for generating optimal designs and calculating power. | Designing and evaluating the statistical power of planned experiments. |

| Cdk-IN-2 | Cdk-IN-2, CAS:1269815-17-9, MF:C18H19ClFN3O2, MW:363.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ixazomib citrate | Ixazomib Citrate - 1239908-20-3 - Proteasome Inhibitor | Ixazomib citrate is a proteasome inhibitor for cancer research. This product, CAS 1239908-20-3, is for Research Use Only and not for human consumption. |

Visualization and Color Accessibility Guidelines

Effective data visualization is a critical component of reporting DOE results. Adherence to the following guidelines ensures that figures are interpretable by a broad audience, including those with color vision deficiencies [9] [10].

- Color Scheme Selection: Use sequential color schemes (e.g., white to highly saturated single color) for ordered data, diverging schemes for data with a critical midpoint, and categorical schemes (with a maximum of 6-12 distinct colors) for qualitative data [9].

- Accessibility: Avoid relying solely on color to convey information. Incorporate differing shapes, fill patterns, or direct labels. Use online tools like ColorBrewer (which includes a "colorblind safe" option) or Coblis (a color blindness simulator) to test palettes [9] [10].

- RGB Color Model: For digital figures, use the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) color model, specifying colors with hexadecimal codes (e.g., #34A853 for green) to ensure consistency across platforms [10].

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate experimental design based on the research objective, incorporating these visualization guidelines.

Figure 2: A decision pathway for selecting an appropriate experimental design.

In modern organic synthesis, particularly within pharmaceutical development, achieving optimal reaction outcomes requires a systematic approach to navigating complex experimental spaces. The key variables—catalysts, solvents, temperature, and stoichiometry—interact in ways that profoundly influence yield, selectivity, and efficiency. Traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization approaches often fail to capture these critical interactions, leading to suboptimal conditions and prolonged development timelines. The implementation of Design of Experiments (DoE) principles, particularly Response Surface Methodology (RSM), provides a powerful framework for efficiently mapping these multidimensional parameter spaces and identifying robust optimal conditions [11] [12]. This application note details practical methodologies for integrating DoE into the optimization of organic syntheses, featuring structured protocols, quantitative guidance, and visualization tools tailored for research scientists.

Quantitative Guidance for Reaction Variable Selection

Solvent Selection Guide

Table 1: Properties of Common Organic Synthesis Solvents

| Solvent | Dielectric Constant (ε) | Boiling Point (°C) | Polarity Class | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | 1.89 | 69 | Non-polar | Extraction, non-polar reactions |

| Toluene | 2.38 | 111 | Non-polar | Friedel-Crafts, organometallics |

| Diethyl ether | - | 34.6 | Low polarity | Grignard reactions, extractions |

| Dichloromethane | 8.93 | 39.8 | Moderate polarity | SN1 reactions, extractions |

| Tetrahydrofuran | - | 66 | Moderate polarity | Organometallics, polymerizations |

| Acetonitrile | 37.5 | 82 | Polar aprotic | SN2 reactions, photochemistry |

| Dimethylformamide | - | 153 | Polar aprotic | Transition metal catalysis, nucleophilic substitutions |

| Water | 80.1 | 100 | Polar protic | Hydrolysis, green chemistry |

Solvent polarity significantly impacts reaction mechanisms and rates. Polar solvents stabilize charged intermediates, making them ideal for reactions like SN1 processes, where a carbocation intermediate requires stabilization [13]. Conversely, non-polar solvents like hexane or toluene may be preferred for reactions involving non-polar intermediates or substrates. The dielectric constant (ε) serves as a quantitative measure of solvent polarity, with higher values indicating greater polarity [13].

Beyond polarity, practical considerations include boiling point (affecting temperature control and solvent removal), toxicity, and environmental impact. Solvent mixtures can sometimes provide superior outcomes by balancing beneficial properties of multiple solvents, as demonstrated in a case study where a toluene/dichloromethane mixture (1:1) achieved 85% yield and 90% selectivity, outperforming either solvent alone [13].

Temperature Optimization Guidelines

Table 2: Temperature Ranges and Their Applications in Organic Synthesis

| Temperature Range | Common Applications | Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic (-78°C to -40°C) | Organolithium chemistry, directed lithiations, sensitive functional group protection | Favors kinetic control, enhances selectivity |

| Low (0°C to 25°C) | Diazotization, sensitive heterocycle formations, enzyme-catalyzed reactions | Kinetic control dominant |

| Ambient (25°C) | Many coupling reactions, Michael additions, click chemistry | Balanced kinetic and thermodynamic control |

| Elevated (50°C to 100°C) | Nucleophilic substitutions, esterifications, Diels-Alder reactions | Thermodynamic control increases with temperature |

| Reflux Conditions (Solvent-dependent) | Extended reaction times, energy-intensive transformations | Shifts toward thermodynamic control |

Temperature profoundly influences both reaction rate and selectivity through the Arrhenius equation (k = Ae^(-Ea/RT)), where k is the rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature in Kelvin [14]. Lower temperatures typically favor kinetic control, where the product distribution is determined by relative rates of formation rather than thermodynamic stability. This is particularly valuable for achieving selectivity in complex molecule synthesis [14]. Higher temperatures generally increase reaction rates but may compromise selectivity and promote decomposition pathways.

Catalyst and Stoichiometry Optimization

While specific catalyst recommendations are highly reaction-dependent, modern data-driven approaches can recommend appropriate catalysts, additives, and their optimal quantities. A recent framework demonstrated improved performance over traditional baselines by predicting agent identities, reaction temperature, reactant amounts, and agent amounts as interrelated sub-tasks [15]. Stoichiometry optimization should consider both reactant equivalents and catalyst loading, with modern optimization algorithms capable of navigating these complex parameter spaces efficiently [5].

Experimental Protocols for DoE-Based Synthesis Optimization

Protocol 1: Initial Reaction Screening Using High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

Objective: Rapid identification of promising reaction conditions for further optimization.

Materials:

- Liquid handling system (e.g., Chemspeed SWING, Zinsser Analytic, or Tecan systems)

- Microtiter well plates (96-well or 384-well format)

- Temperature-controlled reactor block

- In-line or offline analytical tools (HPLC, GC, LC-MS)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Select a screening design (e.g., fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman) that efficiently explores the primary variables: catalyst type (categorical), solvent (categorical), temperature (continuous), and stoichiometry (continuous) [5].

- Reaction Setup: Utilize automated liquid handling to dispense reagents according to the experimental design into the microtiter plate. Maintain inert atmosphere if required.

- Reaction Execution: Transfer the plate to a temperature-controlled reactor block. Implement the designated temperature profile for each well.

- Reaction Monitoring: Quench reactions at predetermined timepoints or monitor continuously if in-line analytics are available.

- Analysis: Quantify conversion and selectivity for each well using analytical methods. For the silicate synthesis example, this was done by 1H NMR [16].

- Data Processing: Construct preliminary models identifying significant factors and interactions affecting the critical response variables (yield, selectivity).

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for early-stage reaction scoping in pharmaceutical synthesis, where multiple candidate routes must be evaluated rapidly [5].

Protocol 2: Response Surface Methodology for Reaction Optimization

Objective: Determine optimal conditions for key variables after initial screening.

Materials:

- Standard round-bottom flasks or specialized reaction vessels

- Precision temperature control system

- Automated sampling or quenching capability

- Analytical instrumentation (HPLC, GC, NMR)

Procedure:

- Central Composite Design: Implement a central composite design or Box-Behnken design around the promising conditions identified in Protocol 1. These designs efficiently estimate quadratic effects, essential for locating optima [11] [12].

- Reaction Execution: Conduct experiments in randomized order to minimize systematic error. For the synthesis of diisopropylammonium bis(catecholato)cyclohexylsilicate, this involved refluxing in tetrahydrofuran with precise stoichiometric control [16].

- Response Measurement: Quantify key responses (yield, selectivity, purity) for each experimental run.

- Model Building: Fit the data to a second-order polynomial model: ( Y = β0 + ΣβiXi + ΣβiiXi^2 + ΣβijXiXj ) where Y is the response, β are coefficients, and X are variables.

- Optimization: Use canonical analysis to locate the optimum conditions [12]. For multiple responses, apply desirability functions to find a compromise optimum.

- Verification: Conduct confirmation experiments at the predicted optimum to validate model accuracy.

Applications: This protocol is ideal for late-stage optimization of key synthetic steps in drug development, where achieving robust, high-yielding conditions is critical for process scale-up.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Optimized Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polar Aprotic Solvents | Acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO | Stabilize charged transition states, dissolve diverse substrates | Ideal for SN2 reactions, palladium-catalyzed couplings |

| Non-polar Solvents | Hexane, Toluene, Cyclohexane | Dissolve non-polar compounds, minimize solvation of charged species | Suitable for free radical reactions, organolithium chemistry |

| Chlorinated Solvents | Dichloromethane, Chloroform | Moderate polarity, volatile for easy removal | Useful for extraction, SN1 reactions; environmental concerns |

| Ether Solvents | THF, Diethyl ether, 1,4-Dioxane | Lewis basicity coordinates to metals, moderate polarity | Essential for Grignard reactions, organometallic catalysis |

| Lewis Acid Catalysts | AlCl3, BF3, TiCl4 | Activate electrophiles towards reaction | Friedel-Crafts acylations/alkylations, Diels-Alder reactions |

| Transition Metal Catalysts | Pd(PPh3)4, Ni(COD)2, RuPhos | Facilitate cross-coupling, C-H activation | Suzuki, Heck, Buchwald-Hartwig amination reactions |

| Bases | K2CO3, Et3N, NaH, LDA | Scavenge protons, generate nucleophiles | Deprotonation, elimination reactions, substrate activation |

| Reducing Agents | LiAlH4, NaBH4, DIBAL-H | Source of hydride equivalents | Carbonyl reductions, selective functional group manipulation |

| GNF-6231 | GNF-6231, MF:C24H25FN6O2, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Norvancomycin hydrochloride | Norvancomycin hydrochloride, CAS:213997-73-0, MF:C65H74Cl3N9O24, MW:1471.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Case Study: Kinetic Control in Selective Synthesis

The principle of kinetic control enables selective formation of desired products by manipulating reaction conditions to favor the pathway with the lowest activation barrier, even if it leads to a less thermodynamically stable product [14]. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical synthesis where specific regio- or stereochemistry is required for biological activity.

Implementation Strategy:

- Lower reaction temperatures slow down all reactions but disproportionately affect pathways with higher activation energies

- Careful catalyst selection can lower the activation energy for the desired pathway specifically

- Solvent effects can stabilize certain transition states over others

- Controlled addition rates of reagents maintain favorable concentration gradients

In practice, kinetic control requires careful monitoring of reaction progress to quench the reaction before thermodynamic equilibrium is established. Analytical techniques like in-situ IR or rapid sampling coupled with HPLC analysis enable real-time tracking of product distribution [14].

Systematic optimization of catalysts, solvents, temperature, and stoichiometry through designed experiments represents a paradigm shift in organic synthesis methodology. The integration of High-Throughput Experimentation with Response Surface Methodology provides a powerful framework for efficiently navigating complex experimental spaces and identifying robust optimal conditions. The protocols and guidelines presented here offer practical implementation strategies that can significantly reduce development timelines and improve reaction outcomes in pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis. As synthetic methodologies continue to evolve, the marriage of experimental design with automated synthesis platforms and machine learning algorithms promises to further accelerate the discovery and optimization of organic transformations [15] [5].

Application Notes

The exploration of high-dimensional parametric space represents a paradigm shift in the design of experiments for organic synthesis, moving from traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches to efficient, multi-variable synchronous optimization enabled by laboratory automation and machine learning (ML) [17] [5]. This shift is crucial for drug development, where optimizing reactions for yield, selectivity, and purity requires navigating complex parameter interactions that OFAT methods cannot adequately address [17].

The core challenge lies in the exponential growth of the experiment number with additional parameters. For example, optimizing just three parameters with five values each creates 125 possible combinations; adding a fourth parameter with ten values expands this to 1,250 [18]. High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) platforms address this by using automation and parallelization to execute and analyze numerous experiments rapidly [17] [5]. When coupled with ML optimization algorithms, these platforms can form closed-loop, "self-driving" systems that iteratively propose and execute experiments to find optimal conditions with minimal human intervention [17].

Machine learning guides this exploration by building models that predict reaction outcomes from parameters. Bayesian Optimization is prominent, using an acquisition function to balance exploration of unknown parameter regions against exploitation of known high-performing areas [18]. Tools like CIME4R, an open-source interactive web application, help researchers analyze optimization campaigns and understand AI model predictions, bridging human expertise and computational power [18].

For resource-constrained projects, computation-guided tools like ChemSPX offer an alternative. This Python-based program uses an inverse distance function to map parameter space and strategically generate new experiment sets that sample sparse, underexplored regions, maximizing information gain from a minimal number of experiments [19].

Table 1: Key High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms for Organic Synthesis

| Platform Name/Type | Key Features | Applications in Organic Synthesis | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Batch Systems (e.g., Chemspeed, Mettler Toledo) [17] | Automated liquid handling, 24- to 1536-well reactor blocks, heating, mixing | Suzuki–Miyaura couplings, Buchwald–Hartwig aminations, N-alkylations, photochemical reactions [17] | High throughput; limited independent control of time/temperature in individual wells; commercial cost [17] |

| Custom Academic Platforms (e.g., mobile robot [17], portable synthesizer [17]) | Tailored to specific needs, can integrate disparate stations (dispensing, sonication, analysis) | Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, solid/liquid-phase synthesis of organic molecules, peptides, oligonucleotides [17] | High versatility and adaptability; requires significant initial development investment [17] |

| Industrial Automated Labs (e.g., Eli Lilly's ASL [17]) | Fully integrated, cloud-accessible, gram-scale reactions, diverse conditions (cryogenic, microwave, high-pressure) | Large-scale reaction execution across diverse case studies [17] | High productivity for gram-scale synthesis; very high initial investment and infrastructure [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Closed-Loop ML-Guided Optimization Campaign

This protocol outlines the workflow for an iterative, AI-guided reaction optimization campaign, visualized in Figure 1.

1. Design of Experiments (DOE)

- Define the Parameter Space: Identify all categorical (e.g., solvent, catalyst, ligand) and continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration, reaction time) parameters and their feasible ranges [18].

- Select Initial Experiments: Choose an initial set of experiments (the "first batch") to seed the ML model. This can be done via Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or random sampling to ensure a broad, space-filling initial coverage of the parameter space [19] [18].

2. Reaction Execution

- Utilize HTE Platforms: Execute the batch of experiments using an automated HTE platform [17]. The platform handles liquid handling, reagent addition, reaction setup (heating, mixing), and quenching.

3. Data Collection and Processing

- Analyze Products: Use in-line or off-line analytical tools (e.g., UHPLC, GC, NMR) to characterize the reaction outcome(s) (e.g., yield, conversion, selectivity) for each experiment [17].

- Curate Dataset: Create a structured dataset mapping each set of reaction conditions to its corresponding outcome(s).

4. Machine Learning and Prediction

- Train ML Model: Input the curated dataset into an ML model (e.g., a Bayesian Optimization algorithm) [18].

- Generate New Predictions: The trained model predicts outcomes for all possible (or a large subset of) parameter combinations in the defined space. It also calculates the uncertainty (variance) for these predictions [18].

- Propose Next Experiments: An acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Expected Improvement) uses the predictions and uncertainties to propose the next batch of experiments, optimally balancing exploration and exploitation [18].

5. Iteration

- The newly proposed experiments are fed back to Step 2 for execution. This closed-loop process continues until a satisfactory outcome is achieved or resources are exhausted [17] [18].

Figure 1: Closed-loop ML-guided optimization workflow.

Protocol 2: Exploring Parameter Space Using ChemSPX for Hydrolysis of DMF

This protocol details the application of the ChemSPX Python program for a non-automated, computation-guided exploration of a specific reaction: the acid-hydrolysis of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), relevant to metal-organic framework (MOF) synthesis [19].

1. Objective To efficiently sample the multi-dimensional parameter space of DMF hydrolysis to understand the influence of various parameters (e.g., acid additive, temperature, time, water content) on the formation of formic acid [19].

2. Define Parameters and Ranges

- Parameters: Acid type (categorical: HCl, Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, TFA, etc.), acid concentration, temperature, reaction time, water content.

- Ranges: Set realistic minimum and maximum values for each continuous parameter.

3. Generate Initial Experiment Batch with ChemSPX

- Configure ChemSPX: Initialize the ChemSPX program with the defined parameter space.

- Initial Sampling: Use the built-in algorithm (e.g., LHS) to generate an initial set (e.g., M=20) of experiment conditions. The algorithm maximizes the distance between these initial points in parameter space to ensure diversity [19].

4. Execute and Analyze Experiments

- Manual Experimentation: Set up and run each hydrolysis reaction according to the generated conditions in a standard lab setting.

- Quantify Outcome: Use quantitative NMR (qNMR) or another suitable method to measure the concentration of formic acid produced in each experiment [19].

5. Sequential Sampling with Inverse Distance Function

- Input Data to ChemSPX: Provide ChemSPX with the results from the initial batch.

- Identify Sparse Regions: The algorithm calculates the inverse distance function (φ) for the entire parameter space, identifying regions that are most underexplored [19].

- Generate Next Experiment Batch: ChemSPX proposes a new set of experiments located in these sparse regions, maximizing the information gained about the parameter space landscape.

6. Data Analysis and Model Building

- Statistical Analysis and ML: Use the collected dataset to perform statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA) or train a simple ML model (e.g., linear regression, decision tree) to identify critical factors and their interactions affecting DMF hydrolysis [19].

Figure 2: ChemSPX-guided parameter space exploration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Throughput Exploration

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in HTE |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (MTP) | Standardized reaction vessels (e.g., 96, 384, or 1536-well plates) enabling parallel synthesis and high-throughput screening [17]. |

| Commercial HTE Platforms | Integrated robotic systems for automated liquid handling, reaction execution, and workup. Key for closed-loop optimization [17]. |

| Python-based ML Libraries | Provide algorithms for design of experiments, Bayesian optimization, and data analysis. |

| ChemSPX | A specialized Python program for computation-guided, strategic sampling of reaction parameter space without dependency on prior experimental data [19]. |

| CIME4R | An open-source interactive web application for visualizing and analyzing data from reaction optimization campaigns, crucial for understanding AI model predictions [18]. |

| CPA inhibitor | CPA inhibitor, CAS:223532-02-3, MF:C18H19NO4, MW:313.3 g/mol |

| Bet-IN-1 | Bet-IN-1, MF:C25H30N4O4, MW:450.5 g/mol |

The Role of Automation and Robotics in Foundational Screening

Foundational screening in organic synthesis involves the systematic evaluation of chemical reactions and conditions to establish robust and efficient synthetic methodologies. The integration of automation and robotics has revolutionized this process, enabling researchers to explore experimental spaces more comprehensively than traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approaches. When framed within the context of Design of Experiments (DoE) principles, automated screening becomes a powerful strategy for accelerating reaction optimization and development [20]. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries where understanding complex factor interactions is essential for developing sustainable and scalable synthetic routes.

The application of robotic screening systems allows for precise control over multiple reaction parameters simultaneously, facilitating the efficient mapping of reaction landscapes. This capability is critical for modern organic synthesis research, where the relationship between reaction components—including catalysts, solvents, temperature, and concentration—often involves significant interactions that OVAT approaches frequently miss [20]. By implementing DoE principles through automated platforms, researchers can extract maximum information from a minimal number of experiments, dramatically reducing development time and material consumption while improving reaction understanding and optimization.

DoE and Automated Screening: A Strategic Framework

Core Principles Integration

The synergy between Design of Experiments and automated robotics creates a systematic framework for foundational screening in organic synthesis. Traditional OVAT optimization varies individual factors while holding others constant, potentially missing optimal conditions due to factor interactions and response surface complexities [20]. In contrast, statistical DoE approaches systematically vary multiple factors simultaneously to efficiently explore the experimental space and model complex relationships between variables and outcomes.

Automation enables the practical implementation of sophisticated DoE designs by executing numerous experimental conditions with precision and reproducibility. Robotic platforms can accurately dispense sub-microliter volumes of reagents, maintain precise temperature control, and perform intricate reaction sequences without intervention [21] [22]. This capability is particularly valuable for response surface methodology (RSM) and factorial designs that require execution of multiple experimental conditions across multi-dimensional parameter spaces. The integration allows researchers to rapidly identify critical factors, optimize reaction conditions, and develop robust synthetic protocols with comprehensive understanding of parameter effects and interactions.

Experimental Workflow Architecture

The implementation of automated foundational screening follows a structured workflow that integrates experimental design, robotic execution, and data analysis. This systematic approach ensures efficient resource utilization and maximizes information gain from each experimental campaign.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for automated Design of Experiments screening in organic synthesis.

Implementation in Organic Synthesis

Solvent Screening and Optimization

Solvent selection critically influences reaction rate, selectivity, mechanism, and yield in organic synthesis. Traditional solvent screening often relies on chemist intuition and limited experimentation, potentially overlooking optimal solvent systems. Automated platforms integrated with DoE principles enable systematic exploration of multidimensional solvent space using solvent maps based on principal component analysis (PCA) of physical properties [20].

These solvent maps categorize solvents according to properties such as polarity, hydrogen bonding capability, and polarizability, creating a structured framework for selection. Automated robotic systems can then efficiently execute screening experiments using representative solvents from different regions of this map. This approach not only identifies optimal solvents for specific reactions but also facilitates replacement of hazardous solvents with safer alternatives, supporting the development of greener synthetic methodologies. The integration of automated solvent dispensing with real-time analysis enables rapid mapping of solvent effects on reaction outcomes, providing valuable insights into reaction mechanisms and solvent-solute interactions.

Reaction Parameter Optimization

Comprehensive optimization of synthetic reactions requires simultaneous investigation of multiple continuous and categorical variables, including temperature, catalyst loading, reagent stoichiometry, and concentration. Automated robotic systems enable precise control and manipulation of these factors according to statistical experimental designs. For example, a single automated screening campaign can systematically explore the effects of temperature gradients, catalyst concentrations, and reagent ratios on reaction yield and selectivity [20].

This multi-factorial approach is particularly valuable for identifying complex interaction effects, such as temperature-catalyst interactions that significantly influence reaction performance. Automated platforms facilitate execution of these designed experiments with minimal human intervention, ensuring consistency and reproducibility while freeing researcher time for data analysis and interpretation. The resulting data enables construction of predictive models that describe the relationship between reaction parameters and outcomes, supporting optimization and robustness testing within defined design spaces.

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Automated foundational screening systems demonstrate quantifiable advantages in efficiency, accuracy, and throughput compared to manual approaches. These performance metrics validate the investment in automation technology for research and development applications.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Automated Screening Systems

| Performance Parameter | Manual Methods | Automated Systems | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | 10-20 reactions/day | 100-1000 reactions/day | 5-50x [21] |

| Liquid Handling Accuracy | 5-10% CV (manual pipetting) | 1-2% CV (automated dispensing) | 3-5x improvement [22] |

| Solvent Screening Efficiency | 3-5 solvents evaluated | 20-50 solvents evaluated | 4-10x [20] |

| Experimental Reproducibility | 10-15% RSD | 2-5% RSD | 3-5x improvement [22] |

| Error Rate | 5-10% (human error) | <1-2% (automated systems) | 5x reduction [21] |

| Data Generation Continuity | 6-8 hours/day (limited by operator) | 24 hours/day (continuous operation) | 3-4x increase [21] |

Table 2: Success Metrics in Automated Method Development

| Application Domain | Success Metric | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Toxicology | Sample preparation success rate | 98.3% (1073/1092 samples) | [22] |

| Reaction Optimization | Factor interactions identified | 3-5x more interactions detected vs. OVAT | [20] |

| Method Scalability | Transfer to production success | 85-90% first-time success | [23] |

| Resource Utilization | Solvent and reagent consumption | 60-70% reduction in material use | [20] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated DoE Screening for Reaction Optimization

This protocol describes the implementation of a factorial design for initial reaction screening using automated liquid handling systems.

Materials and Equipment:

- Robotic liquid handling platform (e.g., Tecan Evo, Hamilton STAR)

- Temperature-controlled reaction blocks

- Analytical instrumentation (HPLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS)

- Chemical reagents and solvents

- Microtiter plates or reaction vials

Procedure:

DoE Design Implementation:

- Select 4-6 critical continuous factors (e.g., temperature, catalyst loading, concentration)

- Define factor ranges based on preliminary experiments or literature data

- Generate a Resolution IV fractional factorial design (for screening) or central composite design (for optimization)

- Program the experimental design matrix into the robotic control software

Robotic System Configuration:

- Calibrate liquid handling components for each reagent solution

- Configure temperature control parameters for reaction blocks

- Establish sampling and quenching protocols for time-point analysis

- Validate dispensing accuracy gravimetrically or spectrophotometrically [22]

Automated Execution:

- Execute reagent additions according to the design matrix

- Initiate reactions simultaneously with temperature control

- Monitor reaction progress through periodic automated sampling

- Quench reactions at predetermined time points

Analysis and Modeling:

- Transfer samples to analytical instrumentation

- Quantify reaction conversion and selectivity

- Fit response surface models to experimental data

- Identify significant factors and factor interactions

- Determine optimal reaction conditions through model prediction

Validation:

- Confirm predicted optimum through experimental verification

- Assess model adequacy through residual analysis

- Evaluate robustness around optimal conditions [20]

Protocol 2: Automated Solvent Screening Using PCA-Based Solvent Maps

This protocol utilizes principal component analysis-based solvent selection for efficient exploration of solvent effects on reaction outcomes.

Materials and Equipment:

- Robotic liquid handling system with solvent resistance

- Chemically resistant tips and tubing

- Solvent library representing diverse chemical properties

- Analytical instrumentation for reaction monitoring

Procedure:

Solvent Map Generation:

- Select 20-30 solvents representing diverse chemical properties

- Calculate principal components based on solvent properties (polarity, hydrogen bonding, etc.)

- Generate a 2D or 3D solvent map based on the first principal components

- Identify solvents from different regions of the map for screening [20]

Automated Solvent Preparation:

- Program solvent distribution sequence into robotic software

- Dispense selected solvents into reaction vessels

- Add substrates and reagents to solvent systems

- Maintain inert atmosphere if required

Reaction Execution:

- Initiate reactions simultaneously across all solvent systems

- Maintain temperature control throughout experiment

- Monitor reaction progress through automated sampling

- Quench reactions at appropriate time points

Data Analysis:

- Analyze samples to determine reaction outcomes

- Correlate solvent position on PCA map with reaction performance

- Identify optimal solvent regions for the specific reaction type

- Select lead solvent candidates for further optimization

Validation:

- Verify lead solvents in scale-up experiments

- Evaluate solvent mixtures for synergistic effects

- Assess green chemistry metrics for selected solvents [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementation of automated foundational screening requires specialized materials and equipment to ensure reproducibility, accuracy, and compatibility with robotic systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Automated Screening

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Automated Screening | Compatibility Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Libraries | Palladium complexes, organocatalysts, enzyme preparations | Screening catalyst activity and selectivity | Solubility in screening solvents, stability in solution |

| Solvent Systems | Water, MeCN, DMF, THF, 2-MeTHF, CPME, EtOAc | Exploring solvent effects on reaction outcomes | Robotic system compatibility, viscosity for dispensing |

| Reagent Solutions | Boronic acids, amines, alkyl halides, oxidizing agents | Evaluating substrate scope and reactivity | Chemical stability, concentration optimization |

| Internal Standards | Anthracene, tridecane, specialized deuterated standards | Quantifying reaction conversion and yield | Chromatographic separation, mass spectrometric detection |

| Calibration Solutions | Orange G, caffeine, potassium chromate | Verifying liquid handling accuracy and precision | Absorbance characteristics, stability [22] |

| Derivatization Agents | Silylation, acylation, chromogenic reagents | Enabling detection and analysis of products | Reaction specificity, byproduct formation |

| PI4KIIIbeta-IN-9 | PI4KIIIbeta-IN-9, MF:C23H25N3O5S2, MW:487.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Ozagrel hydrochloride | Ozagrel hydrochloride, CAS:74003-18-2, MF:C13H12N2O2.HCl, MW:264.71 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Analytical Workflows

Modern automated screening platforms incorporate inline or at-line analytical techniques to enable real-time reaction monitoring and rapid decision-making. This integration creates closed-loop systems where analytical data directly informs subsequent experimental iterations.

Figure 2: Integrated analytical workflow for automated reaction screening and optimization.

The seamless connection between automated synthesis and analysis enables real-time reaction monitoring and rapid experimental iteration. This integration is particularly valuable for capturing kinetic profiles and identifying transient intermediates that provide mechanistic insights. Automated platforms can be programmed to trigger additional experiments based on real-time results, creating an adaptive experimental workflow that responds to incoming data. This approach maximizes information content per unit time and accelerates the optimization process, reducing the timeline from initial discovery to optimized protocol.

The integration of automation and robotics with Design of Experiments principles has transformed foundational screening in organic synthesis research. This synergistic approach enables comprehensive exploration of complex experimental spaces, identification of critical factor interactions, and development of robust predictive models. The structured methodologies and protocols presented here provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing automated screening strategies that enhance efficiency, reproducibility, and information yield in synthetic methodology development. As automation technology continues to advance alongside increasingly sophisticated DoE approaches, this integrated strategy will play an expanding role in accelerating discovery and optimization across chemical research domains.

Advanced Tools and Workflows: HTE, Flow Chemistry, and Machine Learning

Within organic synthesis research, the efficient exploration of chemical space and optimization of reaction conditions are paramount. High-Throughput Experimentation has emerged as a transformative tool, enabling the rapid and parallel investigation of numerous synthetic parameters [24]. Central to implementing HTE is the choice between two primary reactor paradigms: batch and flow systems. The design of experiments for organic synthesis must be intrinsically linked to the capabilities and constraints of the physical hardware [7]. This Application Note details the principles, protocols, and practical considerations for employing batch and flow HTE platforms, providing researchers and development professionals with a framework for selecting and deploying these powerful technologies within a modern, data-driven research strategy.

Batch HTE Systems

Batch HTE platforms conduct reactions in discrete, isolated volumes without the continuous addition of reactants or removal of products during the process. These systems leverage parallelization, using reaction blocks or well plates (e.g., 96, 384, or 1536-well plates) to perform multiple experiments simultaneously [5]. A standard setup includes a liquid handling system for reagent dispensing, a reactor block with integrated heating and mixing capabilities, and often an in-line or offline analysis station [5]. Their versatility is a key advantage, allowing for easy control over categorical variables and stoichiometry. However, a significant limitation is the inability to independently control process variables like temperature and reaction time for individual wells within a shared plate [5].

Flow HTE Systems

In contrast, flow HTE systems involve the continuous pumping of reagents through a reactor, enabling steady-state operation and precise control over reaction parameters such as residence time, temperature, and pressure [25]. These systems are particularly noted for enhancing safety by containing small reaction volumes at any given time, which is beneficial for handling hazardous or exothermic reactions [25]. A major strength of flow chemistry is its suitability for scale-up; a reaction optimized in a laboratory flow reactor can be scaled predictably by increasing operation time or employing parallel reactors [25]. Furthermore, the combination of photo- and electro-chemistry is often more readily implemented in flow systems due to superior photon and electron delivery compared to traditional batch setups [26].

Quantitative Comparison of HTE Platforms

The choice between batch and flow systems depends on specific research goals and reaction requirements. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Batch and Flow HTE Systems for Organic Synthesis

| Feature | Batch HTE Systems | Flow HTE Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Production Quantity | Specific quantity per batch; discrete runs [27]. | Continuous flow of product; steady-state operation [27]. |

| Setup Time | Requires significant setup/reconfiguration between batches [27]. | Minimal setup time between runs; continuous process [27]. |

| Inventory (Work-in-Progress) | Higher inventory levels due to batch processing [27]. | Lower inventory levels due to continuous flow [27]. |

| Reaction Variable Control | Limited independent control per well in a shared plate [5]. | Precise, continuous control over time, temperature, and pressure [25]. |

| Quality Control | More extensive measures needed per batch [27]. | Consistent and predictable process allows for tighter quality control [25]. |

| Lead Time | Can be longer due to scheduling of runs and setup [27]. | Shorter lead times due to streamlined, continuous process [27]. |

| Resource Utilization | Can lead to underutilization due to downtime between batches [27]. | Generally more efficient and optimal resource use [27]. |

| Scalability | Scaled by increasing batch size or number of vessels, which can introduce new challenges [25]. | Inherently scalable; simplified transition from lab to production [25]. |

| Safety | Larger reaction volumes can pose higher risks for exothermic or hazardous reactions [25]. | Enhanced safety from smaller reaction volumes at any given time [25]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Reaction Optimization in Batch HTE

This protocol outlines the optimization of a sulfonation reaction for redox-active molecules using a automated batch platform, based on a study employing flexible batch Bayesian optimization [7] [28].

1. Experimental Design and Initialization:

- Define Search Space: Identify and set boundaries for key reaction variables. In the referenced study, this was a 4D space comprising reaction time (30.0–600 min), temperature (20.0–170.0 °C), sulfuric acid concentration (75.0–100.0%), and fluorenone analyte concentration (33.0–100 mg mLâ»Â¹) [7].

- Generate Initial Conditions: Use a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to generate the first batch of experimental conditions (e.g., 15 unique conditions) [7].

- Account for Hardware Constraints: The idealized LHS conditions may require adjustment for physical hardware. For example, if the heating system only supports three distinct temperatures, cluster the LHS-generated temperatures to determine three centroid values and reassign conditions to the nearest available temperature [7].

2. Reaction Execution:

- Liquid Handling: Employ a robotic liquid handler (e.g., Chemspeed SWING) to accurately dispense reagents and prepare reaction mixtures in a 96-well plate or similar reactor block according to the designed conditions [7] [5].

- Initiate Reaction: Transfer the reaction plate to a heating block set to the predefined temperatures. Start the reaction with mixing.

3. Product Analysis and Data Processing:

- Quenching and Transfer: After the specified reaction time, quench the reactions and automatically transport samples to an analysis system like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [7].

- Feature Extraction: Analyze chromatograms to identify peaks corresponding to product, reactant, and byproducts. Calculate the percent yield for each condition based on peak areas [7].

- Data Consolidation: Calculate the mean and variance of yields for replicate specimens to train a surrogate model.

4. Machine Learning-Guided Iteration:

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model on the collected yield data [7] [29].

- Suggest New Conditions: Use a Batch Bayesian Optimization (BBO) algorithm with an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to suggest the next set of conditions predicted to maximize yield. The algorithm must respect hardware constraints, such as a limited number of available temperatures [7].

- Close the Loop: Execute the new suggested conditions (Steps 2-4) iteratively until optimal yield is achieved or resources are exhausted.

Protocol for Reaction Screening in Flow HTE

This protocol describes a generalized workflow for screening photochemical reactions in a continuous flow system, leveraging the enhanced photon delivery of such platforms [26].

1. System Configuration and Priming:

- Reactor Setup: Select an appropriate flow photoreactor (e.g., a tube reactor coiled around a light source). Ensure the light source (LED) emission wavelength matches the absorption maximum (λmax) of the photocatalyst or reactant [26].

- Calibration: Precisely calibrate pump flow rates to achieve desired residence times. Use an integrating sphere to quantify the light intensity and spectral output of the LED if possible [26].

- System Priming: Prime all pumps and the reactor with the chosen solvent to remove air and ensure stable fluid dynamics.

2. Reaction Execution and Steady-State Sampling:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of reactants and catalyst, ensuring homogeneity and solubility.

- Pumping and Mixing: Use syringe or peristaltic pumps to deliver reactant solutions. Pass streams through a mixing tee or a static mixer before entering the photochemical reactor.

- Establish Steady State: Allow the system to run for at least three times the residence time to reach a steady state before collecting any product for analysis.

- Sample Collection: Collect the reactor effluent into a collection vial or an automated sampler for analysis.

3. Analysis and Optimization:

- In-line or Off-line Analysis: Analyze samples using techniques like UPLC-MS or GC-MS to determine conversion and yield. In-line analysis can provide real-time data for rapid feedback [24].

- Iterative Refinement: Vary key parameters systematically (e.g., flow rate/residence time, catalyst loading, light intensity) based on the initial results. Software like

phactorcan be used to design and analyze these screening arrays [24]. Bayesian Optimization can also be applied to flow systems for efficient multi-variable optimization [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following reagents and software solutions are critical for executing and managing modern HTE campaigns.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for High-Throughput Experimentation

| Item | Function / Application | Relevance to HTE |

|---|---|---|

| 9-Fluorenone & Sulfuric Acid | Redox-active molecule and sulfonating agent for synthesizing aqueous organic redox flow battery electrolytes [7]. | Model system for optimizing sulfonation reactions under mild conditions using Bayesian Optimization in batch HTE [7]. |

| Photocatalysts (e.g., Organic Dyes, [Ru(bpy)₃]²âº) | Absorb light to initiate photoredox catalysis via Single Electron Transfer (SET) or energy transfer [26]. | Essential for photochemical reactions in flow HTE; requires matching LED wavelength to catalyst absorption profile [26]. |

| Transition Metal Catalysts & Ligands | Enable key cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Buchwald-Hartwig) [5] [24]. | Commonly screened in both batch and flow HTE to discover active catalyst/ligand pairs for new reactivities [5] [24]. |

| phactor Software | Web-based software for designing, executing, and analyzing HTE reaction arrays in well plates [24]. | Streamlines workflow from ideation to result interpretation, generates robot instructions, and stores data in machine-readable formats [24]. |

| Katalyst D2D Software | A commercially available, chemically intelligent platform for managing end-to-end HTE workflows [30]. | Integrates inventory, experiment design, automated analysis, and data visualization; includes Bayesian Optimization module for ML-guided DoE [30]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (EDBO+) | Machine learning algorithm for efficient global optimization of noisy, expensive-to-evaluate functions [7] [29]. | Core decision-making engine in self-driving labs; guides the selection of subsequent experiments to find optimal conditions with minimal trials [7] [29]. |

| d-threo-PDMP | d-threo-PDMP, CAS:109836-82-0, MF:C23H38N2O3.ClH, MW:427.025 | Chemical Reagent |

| Charybdotoxin | Charybdotoxin, CAS:95751-30-7, MF:C176H277N57O55S7, MW:4296 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The discovery and optimization of new organic reactions are fundamental to advancements in pharmaceuticals, materials science, and agrochemicals. Traditionally, this process has been guided by labor-intensive, trial-and-error experimentation, often employing a "one-variable-at-a-time" (OVAT) approach. This method is not only inefficient but also frequently fails to identify true optimal conditions because it cannot account for complex, synergistic interactions between multiple reaction parameters [20]. The integration of Design of Experiments (DoE) provides a powerful statistical framework for systematically exploring this multi-dimensional reaction space, enabling researchers to evaluate the effects of multiple variables and their interactions simultaneously with a minimal number of experiments [31] [20].

The paradigm is now shifting with the confluence of laboratory automation, sophisticated data analysis tools, and Machine Learning (ML). This convergence enables the development of a robust, iterative workflow where ML algorithms can navigate complex parameter spaces, predict promising reaction conditions, and autonomously guide experimentation toward optimal outcomes. This guide details a standard ML-driven optimization workflow, framing it within the context of DoE for organic synthesis research. This approach has demonstrated the ability to find global optimal conditions in fewer experiments than traditional methods, significantly reducing process development time and resource consumption [5] [17].

The Integrated Workflow: From DoE to Autonomous Optimization

The standard ML-driven optimization workflow is an iterative cycle that combines careful experimental design with predictive modeling and automated validation. It transforms the experimental process into a closed-loop system that continuously learns from data.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative nature of the standard ML-driven optimization workflow.

Workflow Description

This workflow creates a closed-loop optimization system [5] [32]. The cycle begins with a carefully designed set of initial experiments that provide a foundational dataset for the ML model. The results from each iteration of experiments are used to refine the model's understanding, allowing it to make increasingly accurate predictions about which areas of the experimental parameter space are most likely to contain the optimum. This process continues until a predefined performance target is met or the system converges on the best possible conditions.

Step-by-Step Protocol and Application Notes

This section provides a detailed, actionable protocol for implementing the ML-driven optimization workflow in an organic synthesis context.

Step 1: Design of Experiments (DoE)

Objective: To plan an initial set of experiments that efficiently explores the multi-dimensional parameter space and generates high-quality data for machine learning model training.

Detailed Protocol:

- Define Objectives: Clearly state the primary optimization goal (e.g., maximize yield, improve selectivity, minimize cost). Consider multi-objective optimization if goals are conflicting [5].

- Select Factors and Ranges: Identify the variables (factors) to be studied, such as:

- Continuous: Temperature, concentration, catalyst loading, reaction time.

- Categorical: Solvent, catalyst type, ligand.

- Define realistic high and low levels for each continuous factor based on chemical feasibility and safety.

- Choose an Experimental Design:

- For an initial screening study to identify the most influential factors from a large set, use a Resolution IV fractional factorial design or a Plackett-Burman design.

- For modeling curvature and locating an optimum, use a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design, such as a Central Composite Design (CCD) [33].

- For optimizing solvent choice, a principal component analysis (PCA)-based solvent map should be used. Select 4-6 solvents from different regions of the PCA map to broadly sample solvent property space [20].

- Generate Experimental Matrix: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Design-Expert, or Python libraries like

pyDOE2) to generate the list of experimental runs, including necessary replicates and center points to estimate experimental error.

Application Note: A well-designed DoE is critical. The initial data quality directly dictates the ML model's performance. Avoid the OVAT pitfall; a properly designed screening DoE with 19 experiments can efficiently evaluate up to eight factors and their interactions [20].

Step 2: High-Throughput Reaction Execution

Objective: To execute the planned DoE matrix rapidly, consistently, and with minimal human intervention.

Detailed Protocol:

- Platform Selection:

- Batch Systems: Utilize commercial high-throughput batch platforms (e.g., Chemspeed, Unchained Labs) or custom-built systems with 24-, 48-, or 96-well reactor blocks [5]. These excel at controlling stoichiometry and chemical formulation.

- Flow Systems: For reactions requiring precise control of time, temperature, or hazardous reagents, consider automated flow chemistry platforms [32].

- Automated Setup: Employ liquid handling robots for precise dispensing of reagents, catalysts, and solvents into reaction vessels according to the DoE matrix.

- Reaction Control: Program the platform to execute the required reaction conditions (temperature, stirring speed, pressure) for each vessel simultaneously.