Modular Robotic Systems: Revolutionizing Exploratory Synthetic Chemistry and Drug Discovery

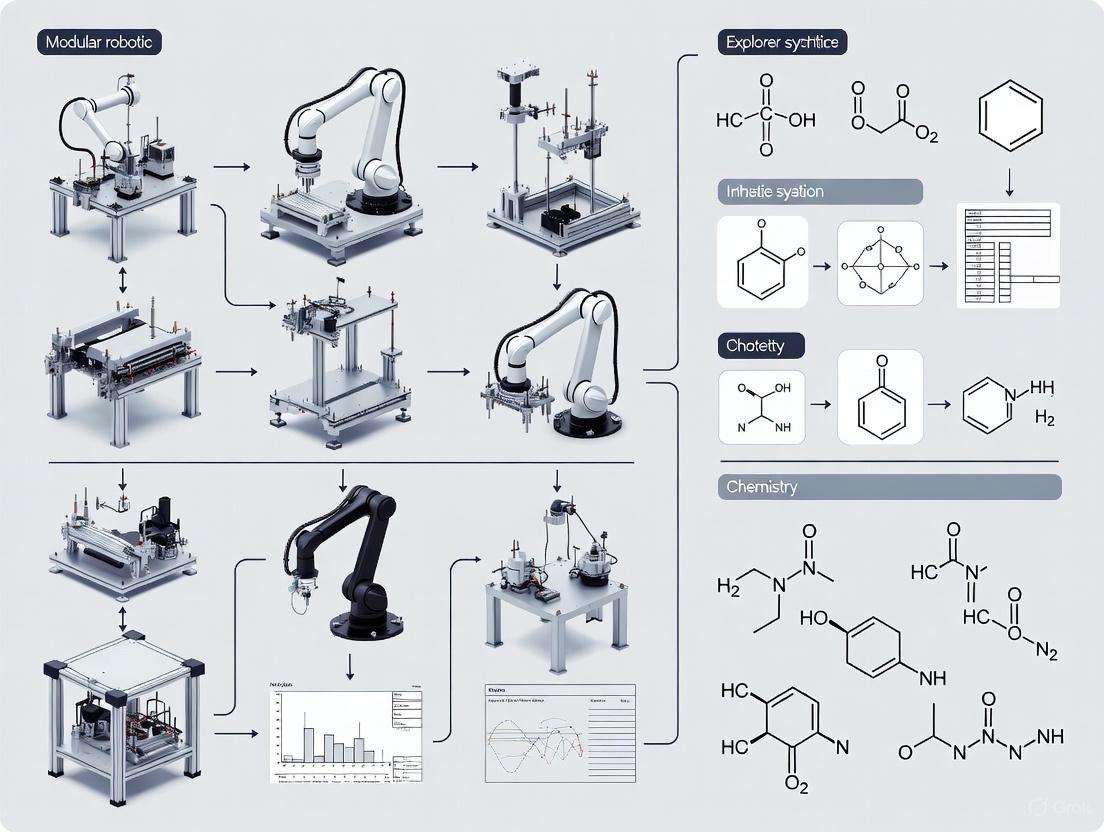

This article explores the transformative impact of modular robotic systems on exploratory synthetic chemistry, a critical field for pharmaceutical R&D.

Modular Robotic Systems: Revolutionizing Exploratory Synthetic Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of modular robotic systems on exploratory synthetic chemistry, a critical field for pharmaceutical R&D. It details the foundational principles of these systems, which leverage mobile robots to integrate standard laboratory equipment into autonomous workflows. The content covers key methodological applications in areas like structural diversification and supramolecular chemistry, supported by case studies. It also addresses critical challenges in system integration, AI decision-making, and optimization, providing a troubleshooting guide for researchers. Finally, the article validates this approach through performance benchmarks, comparative analysis with traditional automation, and a discussion of its growing market adoption, offering scientists and drug development professionals a comprehensive resource for leveraging this disruptive technology.

The New Lab Assistants: Understanding Modular Robotics and Autonomous Discovery

Defining Modular Robotic Systems vs. Traditional Lab Automation

The landscape of laboratory science, particularly in exploratory fields like synthetic chemistry and drug development, is undergoing a fundamental transformation. The traditional model of automation, characterized by large, fixed, and dedicated systems, is being challenged by a new paradigm: modular robotic systems. This shift is driven by the need for greater flexibility, adaptability, and efficiency in research environments where objectives and protocols evolve rapidly. In the specific context of exploratory synthetic chemistry, where reactions can yield multiple potential products and require diverse analytical techniques, the limitations of traditional automation become particularly constraining [1]. This technical guide delineates the core distinctions between these two approaches, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to make informed strategic decisions about automating their laboratories. The move towards modularity represents more than a technical upgrade; it is a conceptual shift from automation as a static tool to automation as a dynamic, integrated partner in the discovery process.

Core Definitions and Conceptual Frameworks

Traditional Lab Automation

Traditional lab automation encompasses systems designed to automate specific, well-defined laboratory processes. These systems are often characterized by their fixed configuration and dedicated function. They can be categorized into several levels of complexity:

- Manual Systems: These involve basic instruments that enhance precision but rely heavily on human operation, such as electronic pipettors and basic spectrophotometers [2].

- Stand-Alone Automation (Modular): These systems automate a single process or a group of related processes, such as automated pipetting systems or plate readers. They offer flexibility as they can be used independently or later integrated with other systems [2].

- Total Laboratory Automation (TLA): TLA systems represent the highest degree of traditional automation, integrating several different processes and instruments into a single, coordinated system. They are commonly used in high-throughput environments like clinical diagnostic labs to automate the entire workflow from sample receipt to result reporting [2].

A key feature of traditional systems, especially TLA, is their reliance on bespoke engineering and physically integrated analytical equipment. This often leads to the proximal monopolization of equipment, forcing decision-making algorithms to operate with limited analytical information [1].

Modular Robotic Systems

Modular robotic systems are composed of discrete, integrated units—or modules—that can function independently or dock with one another to form a composite entity with different capabilities. In a laboratory context, this philosophy translates to a distributed and scalable network of robotic agents and specialized instruments that can be physically and digitally reconfigured for different tasks.

Each module is self-contained, with its own computing, sensing, or actuation capabilities [3]. The system's core strength lies in its interoperability; mobile robotic agents can transport samples between physically separated synthesis and analysis modules, such as an automated synthesizer, a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS), and a benchtop NMR spectrometer, all located anywhere in the laboratory [1]. This architecture allows robots to share existing laboratory equipment with human researchers without monopolizing it or requiring extensive redesign, creating a workflow that closely mimics human experimentation protocols [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Traditional vs. Modular Automation Systems

| Characteristic | Traditional Lab Automation | Modular Robotic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| System Architecture | Fixed, centralized, and often linear | Flexible, distributed, and networked |

| Integration Level | Tightly coupled, bespoke engineering | Loosely coupled, vendor-agnostic orchestration |

| Scalability | Difficult and expensive; often requires a new system | Incremental and flexible; modules can be added as needed |

| Typical Workflow | High-throughput, repetitive, well-defined tasks | Exploratory, variable, and adaptable protocols |

| Interaction with Humans | Replaces human effort in specific tasks | Collaborates with humans, sharing space and equipment |

| Data Handling | Often siloed within the system | Integrated through central dashboards and advanced analytics [4] |

A Detailed Comparison in Practice

The theoretical distinctions between traditional and modular automation manifest concretely in laboratory operations, impacting everything from physical setup to data utilization.

Workflow and Physical Integration

In a Traditional TLA system, the workflow is linear and confined to a fixed track or conveyor system that links integrated instruments. This creates a highly efficient assembly line for a specific, unchanging process. However, it is inherently inflexible; modifying the workflow to include a new analytical technique or to change the process order can require significant mechanical and software re-engineering.

In contrast, a Modular Robotic system employs a hub-and-spoke or free-roaming model. As demonstrated in a Nature publication, a synthesis laboratory was integrated into an autonomous laboratory using mobile robots that operate equipment and make decisions in a human-like way [1]. The workflow is modular, combining mobile robots, an automated synthesis platform, a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer, and a benchtop NMR spectrometer as separate modules. Mobile robots handle sample transportation between these distributed stations, allowing for dynamic and non-linear workflows [1]. This setup is inherently expandable, as other instruments can be added to the network by simply programming the mobile robots to access them.

Decision-Making and Autonomy

The level of autonomy is a critical differentiator. Most traditional automated systems excel at automation—the execution of pre-programmed, repetitive tasks. The decisions about the workflow are made by researchers who set the parameters beforehand.

Modular robotic systems, particularly in advanced implementations, are capable of autonomy. This implies that the system can not only execute tasks but also record and interpret analytical data and make decisions based on them [1]. For example, in an exploratory synthesis workflow, a heuristic decision-maker can process orthogonal NMR and UPLC-MS data, autonomously giving a pass/fail grade to each reaction and selecting successful ones for further study and scale-up, all without human intervention [1]. This closed-loop operation, where the outcome of an experiment directly informs the subsequent step, is a hallmark of advanced modular systems.

Adaptability and Economic Considerations

Adaptability is perhaps the most significant advantage of modular systems. They are designed for change, capable of being reconfigured for new research projects, which is ideal for exploratory chemistry and early-stage drug discovery. Traditional TLA systems are built for stability and peak efficiency in a single, high-volume process, making them more suited to late-stage development and clinical diagnostics.

From an economic perspective, the initial investment for a full-scale modular system can be high. However, its flexibility protects the investment over time, as it can be adapted rather than replaced when research needs change. Traditional TLA requires a massive capital outlay for a system that may become obsolete if the research pipeline shifts. Furthermore, modular systems can leverage existing laboratory equipment, whereas TLA often requires purchasing dedicated, integrated versions of these instruments [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Application and Economic Factors

| Factor | Traditional Lab Automation | Modular Robotic Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Application | High-throughput screening, clinical diagnostics, repetitive quality control | Exploratory synthesis, protocol development, multi-step complex reactions |

| Initial Investment | Very high for TLA; lower for stand-alone modules | High, but can be phased |

| Cost of Reconfiguration | Very high | Relatively low |

| Data Utilization | Siloed; used for immediate process control | Integrated; used for real-time decision-making and long-term learning [4] |

| Return on Investment | Justified by massive, repetitive throughput | Justified by accelerated discovery and research flexibility |

Experimental Protocols in Exploratory Synthetic Chemistry

The application of modular robotic systems is best understood through specific experimental protocols. The following workflow, derived from a published autonomous laboratory, exemplifies the integration of modular hardware and heuristic decision-making [1].

Protocol: Autonomous Divergent Synthesis and Analysis

Objective: To perform a multi-step synthesis, autonomously identify successful reactions using orthogonal analysis techniques, and scale up only the successful pathways for further elaboration.

Materials and Equipment:

- Synthesis Module: Chemspeed ISynth automated synthesizer [1].

- Analysis Modules: Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer (UPLC-MS) and an 80-MHz benchtop NMR spectrometer [1].

- Transportation: Mobile robotic agents with multipurpose grippers.

- Reagents: Appropriate amines, isothiocyanates, isocyanates, and solvents for the desired reactions.

Methodology:

- Synthesis Initiation: The host computer instructs the Chemspeed ISynth to perform the parallel synthesis of precursor molecules, for example, three ureas and three thioureas via combinatorial condensation [1].

- Sample Reformating: Upon reaction completion, the ISynth synthesizer takes an aliquot of each reaction mixture and reformats it into standard vials for MS and NMR analysis.

- Robotic Transport: A mobile robot collects the vials and transports them to the location of the UPLC-MS and NMR instruments. Electric actuators on the instrument doors allow for automated access.

- Autonomous Analysis: The robotic agent loads the samples into each instrument. Customizable Python scripts control data acquisition, and the results are saved in a central database.

- Heuristic Decision-Making: A decision-making algorithm processes the orthogonal UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR data. Based on experiment-specific pass/fail criteria defined by a domain expert (e.g., presence of a desired mass peak, cleanliness of NMR spectrum), it gives a binary grade to each reaction.

- Closed-Loop Action: Reactions that pass both analyses are automatically selected for scale-up within the ISynth platform. The scaled-up products are then used as substrates for the next stage of the divergent synthesis, repeating the analysis-decision-action cycle.

This protocol highlights the key differentiator: the tight integration of physical manipulation and intelligent data interpretation to create a truly autonomous discovery engine.

Visualization of Workflow

The following diagram, generated using Graphviz, illustrates the logical flow and decision points within the autonomous modular robotic system described in the protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for a Modular System

Building or implementing a modular robotic system for exploratory chemistry requires a suite of core components, both hardware and software.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a Modular Robotic Laboratory

| Component | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robotic Agent | Provides physical linkage between discrete modules; transports samples and tools. | Free-roaming robot with a multipurpose gripper for handling vials and operating instrument doors [1]. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform | Executes chemical reactions autonomously; handles liquid and solid dosing, heating, and stirring. | Chemspeed ISynth platform [1]. |

| Orthogonal Analysis Instruments | Provides complementary data for robust characterization and decision-making. | UPLC-MS for mass and purity data; Benchtop NMR for structural information [1]. |

| Laboratory Orchestration Software | The central nervous system; provides vendor-agnostic scheduling and control for all hardware. | Software platforms that offer drivers for diverse laboratory hardware and link data to central dashboards [4]. |

| Heuristic Decision-Maker | Algorithmically interprets analytical data and makes context-based "go/no-go" decisions. | A customizable rules-based system that processes UPLC-MS and NMR data against expert-defined criteria [1]. |

| Digital Record-Keeping System | Automates record-keeping, manages workflows, and enables data mining. | Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) or Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) [4]. |

| Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate | Erythromycin Ethylsuccinate, CAS:41342-53-4, MF:C43H75NO16, MW:862.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lactose octaacetate | Lactose octaacetate, MF:C28H38O19, MW:678.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between traditional lab automation and modular robotic systems is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the laboratory's primary mission. Traditional TLA remains the champion of unmatched efficiency and reproducibility in stable, high-volume, and well-defined processes, such as those in clinical diagnostics.

However, for the frontier of exploratory synthetic chemistry and drug discovery, where the path is not linear and the outcomes are not guaranteed, modular robotic systems offer a transformative advantage. Their core strengths—flexibility, adaptability, and intelligent autonomy—align perfectly with the needs of modern research. By mimicking the multifaceted approach of a human scientist and freeing researchers from repetitive tasks, modular systems accelerate the journey from hypothesis to discovery. They represent not just an incremental improvement in laboratory technology, but a fundamental re-imagining of the experimental process itself, poised to unlock new levels of innovation in science and medicine.

The advent of modular robotic systems is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of exploratory synthetic chemistry research. By integrating three core technological pillars—mobile robots, automated synthesis platforms, and orthogonal analytics—these systems create a flexible, scalable, and efficient framework for autonomous chemical discovery. This paradigm shifts research from traditional, linear, human-centric workflows to continuous, closed-loop cycles that dramatically accelerate the design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) process. The modularity of this approach allows researchers to leverage existing laboratory instrumentation without costly, bespoke engineering, making advanced automation more accessible [1] [5]. This technical guide details the components, integration methodologies, and experimental protocols that underpin these systems, providing a blueprint for their implementation in modern research and development environments, particularly in drug discovery and materials science.

In exploratory synthetic chemistry, the challenge of navigating vast chemical spaces is compounded by the reliance on manual, time-consuming, and often irreproducible experimental procedures. Modular robotic systems address these limitations through a decentralized architecture where physically distinct, specialized modules are connected via mobile robotic agents. This stands in contrast to traditional, hardwired automated systems where synthesis and analysis equipment are permanently integrated, which can be inflexible and expensive [1] [6].

The core philosophy of the modular approach is embodied intelligence, where mobile robots act as the physical link between discrete stations for synthesis and analysis, mimicking the sample transportation and handling tasks of a human researcher [6] [7]. This architecture is inherently scalable; new analytical instruments or synthesis workstations can be incorporated by simply updating the robot's navigation and operation protocols, without redesigning the entire laboratory infrastructure [1]. Furthermore, it promotes resource sharing, as the same high-value analytical equipment (e.g., NMR spectrometers) can be used by both robotic and human researchers, maximizing utility and return on investment [1]. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow within such a system.

Core Component 1: Mobile Robots as a Physical Link

Mobile robots serve as the dynamic, physical backbone of the modular system, replacing fixed conveyor belts or hardwired connections. Their primary function is to bridge the physical gaps between automated synthesis stations and a diverse array of characterization instruments.

Technical Specifications and Capabilities

- Navigation and Mobility: These robots are typically free-roaming, capable of navigating standard laboratory environments to access instruments located anywhere in the facility [1]. They are equipped with sophisticated sensors to avoid obstacles and ensure safe operation alongside human researchers.

- Sample Handling: Robots are fitted with multipurpose grippers designed to handle standard laboratory consumables, such as vials and sample plates [1]. This allows them to perform precise tasks including:

- Collecting aliquots from the synthesis platform.

- Transporting samples to different analytical instruments.

- Loading and unloading samples into the UPLC-MS autosampler and NMR spectrometer.

- System Architecture: Implementation can involve multiple task-specific robots for high-throughput environments or a single multi-purpose robot to minimize equipment redundancy and cost [1]. An example from a proven setup uses two mobile robots for sample transport and instrument operation, but successfully demonstrates that a single agent can also perform all required tasks [1].

Experimental Protocols for Integration

Integrating mobile robots requires a structured approach to ensure seamless operation:

- Instrument Access Modification: Minor physical modifications, such as installing electric actuators on automated synthesis platform doors, are necessary to grant robots automated entry and exit [1].

- Workflow Orchestration: A central control software (host computer) must be deployed to orchestrate the entire workflow. This software sends commands to the robots, directing their movement and task execution based on the predefined experimental sequence [1].

- Protocol Development: Domain experts should develop analytical and synthesis routines using the control software's interface, which requires no specialized robotics programming skills, thereby enhancing accessibility [1].

Core Component 2: Automated Synthesis Platforms

The synthesis module is responsible for the precise and reproducible execution of chemical reactions. In modular systems, these platforms are operated by, rather than permanently connected to, the mobile robots.

Platform Specifications

- Primary Equipment: The Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer is a commonly used platform in documented systems [1] [5]. These systems are designed for automated, parallel chemical synthesis under programmable conditions.

- Environmental Control: They provide precise control over critical reaction parameters such as temperature, pressure, stirring, and irradiation, which is essential for reproducibility and for establishing structure-property relationships [5].

- Automated Sampling: A key feature is the ability to automatically take aliquots from ongoing reactions and reformat them into vials suitable for subsequent analysis by MS and NMR [1].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in a typical automated synthesis platform for exploratory chemistry, as demonstrated in the synthesis of ureas and thioureas [1].

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Automated Synthesis Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application in Automated Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Alkyne Amines | Core building blocks for combinatorial library synthesis, enabling structural diversification [1]. |

| Isothiocyanates | Electrophilic reagents for the automated synthesis of thiourea derivatives [1]. |

| Isocyanates | Electrophilic reagents for the automated synthesis of urea derivatives [1]. |

| Cu/TEMPO Catalyst | Dual catalytic system for autonomous optimization of aerobic alcohol oxidation reactions [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Essential for preparing samples for NMR analysis within the automated workflow [1]. |

| Standard LC Solvents | Required for sample dilution, chromatography, and purification steps (e.g., acetonitrile) [1] [5]. |

Core Component 3: Orthogonal Analytics

Orthogonal analytics refers to the use of multiple, complementary characterization techniques to obtain a comprehensive and unambiguous assessment of reaction outcomes. This is a critical feature that mirrors expert human decision-making.

Analytical Instrumentation

The combination of Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS) and Benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy provides a powerful duo for autonomous analysis [1] [5].

- UPLC-MS provides information on molecular weight, purity, and reaction conversion.

- Benchtop NMR (e.g., 80 MHz) offers insights into molecular structure, functional groups, and reaction progress.

- The use of unmodified, commercial benchtop NMR spectrometers is a key aspect of the modular philosophy, allowing them to be shared with other workflows or human researchers [1].

Data Acquisition and Processing

- Automated Data Capture: After sample delivery by the mobile robot, customizable Python scripts autonomously initiate data acquisition on the instruments [1].

- Structured Data Outputs: To ensure interoperability and machine-readability, analytical data is saved in structured formats such as ASM-JSON (Allotrope Simple Model), JSON, or XML [5]. This structured data is then saved in a central database for processing by the decision-maker.

Table 2: Comparison of Orthogonal Analytical Techniques in Modular Systems

| Technique | Key Data Output | Role in Decision-Making | Throughput in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| UPLC-MS | Molecular weight, chromatographic purity, semi-quantification. | Detects presence/absence of target mass; assesses reaction cleanliness. | High; often the first-line analysis. |

| Benchtop NMR | Molecular structure, functional group transformation, reaction progress. | Confirms structural identity and monitors conversion via spectral changes. | Medium; provides confirmatory data. |

| Additional Analytics (e.g., SFC) | Enantiomeric excess (ee), chiral purity. | Resolves and quantifies stereoisomers in the screening path [5]. | Conditional; used if chirality is a factor. |

Integrated Workflow and Decision-Making

The true power of a modular system is realized when the three core components are seamlessly integrated into a closed-loop workflow, governed by an intelligent decision-making module.

The Autonomous Workflow Cycle

The end-to-end process, depicted in the diagram below, operates as a continuous cycle:

Decision-Making Algorithms: From Heuristics to AI Agents

The system's "brain" can be implemented through different levels of sophistication:

- Heuristic Decision-Maker: This rule-based system processes UPLC-MS and NMR data using expert-defined criteria. It assigns a binary pass/fail grade to each reaction based on both analytical streams. For example, a reaction might need to show both the correct mass in MS and the expected spectral change in NMR to be considered a "pass" and proceed to scale-up [1]. This "loose" heuristic approach remains open to novel discoveries without being overly constrained by pre-defined objectives.

- Large Language Model (LLM) Agents: More advanced systems employ LLM-based agents (e.g., based on GPT-4) as a central planner. These systems, such as the LLM-based reaction development framework (LLM-RDF), can coordinate multiple sub-agents (e.g., Literature Scouter, Experiment Designer, Result Interpreter) to manage the entire process [8]. They use techniques like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to access up-to-date literature and tool-calling to interact with robotic platforms and data analysis software [8]. This enables more flexible and general-purpose autonomous research.

Case Study & Experimental Protocol

Case Study: Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis and Screening [1]

This case study demonstrates the application of a modular robotic system in the exploratory synthesis of ureas/thioureas and the investigation of supramolecular host-guest chemistry.

Objective: To autonomously synthesize a library of compounds, identify successful reactions, validate reproducibility, and, in the case of supramolecular systems, even assay function (host-guest binding).

Detailed Methodology:

Synthesis Setup:

- The Chemspeed ISynth platform is loaded with starting materials: three alkyne amines and one isothiocyanate or isocyanate.

- The platform is programmed to perform parallel condensations to synthesize three ureas and three thioureas combinatorially.

Automated Sampling and Analysis:

- Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer automatically takes aliquots and reformats them for MS and NMR analysis.

- A mobile robot collects the sample vials and transports them to the UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR instruments.

Orthogonal Characterization:

- UPLC-MS Analysis: The system acquires chromatographic and mass spectrometric data for each sample.

- NMR Analysis: The robot loads the sample into the benchtop NMR, which acquires a 1H NMR spectrum.

Data Processing and Decision:

- The heuristic decision-maker processes the data:

- MS Data: Checked against a precomputed m/z lookup table for expected products.

- NMR Data: Analyzed using dynamic time warping to detect reaction-induced spectral changes.

- Reactions that pass both MS and NMR criteria are flagged as successful.

- The heuristic decision-maker processes the data:

Autonomous Follow-up Actions:

- The system automatically initiates reproducibility checks by re-running successful reactions.

- Confirmed hits are then scaled-up for further elaboration or functional testing.

- In the supramolecular chemistry example, the system proceeded to autonomously conduct a host-guest binding assay to evaluate the function of the synthesized assembly.

The integration of mobile robots, automated synthesis platforms, and orthogonal analytics represents a transformative, modular architecture for exploratory synthetic chemistry. This paradigm enables scalable, flexible, and highly efficient research workflows that closely mimic—and in some aspects surpass—the multifaceted decision-making processes of expert human chemists. By closing the DMTA loop with minimal human intervention, these systems significantly accelerate the discovery of new molecules and materials, as evidenced by their successful application in drug discovery and supramolecular chemistry. Future advancements will hinge on developing more robust and generalizable AI decision-makers, standardizing data formats and hardware interfaces, and creating even more fault-tolerant systems. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, modular robotic systems are poised to become a cornerstone of modern chemical research infrastructure.

The paradigm of robotic systems in research is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from static automation to adaptive autonomy. Where traditional automated systems execute predetermined protocols with high precision but limited adaptability, autonomous laboratories represent a revolutionary leap forward. These systems integrate embodied intelligence with robotic hardware to form closed-loop research environments capable of iterative experimentation and intelligent decision-making without human intervention [6]. This shift is particularly transformative for exploratory synthetic chemistry, where the vastness of chemical space and the complexity of structure-property relationships have traditionally constrained the pace of discovery. The emergence of AI as the central decision-making "brain" enables robotic platforms to navigate this complexity, transforming them from mere tools into active research partners that can generate hypotheses, design experiments, and interpret results in the pursuit of novel chemical entities.

Fundamental Architecture of an Autonomous Laboratory

An autonomous laboratory is an advanced robotic platform equipped with embodied intelligence, enabling it to execute experiments, interact with robotic systems, and manage data to effectively close the predict-make-measure discovery loop [6]. This integrated system relies on several synergistic core elements that work together to create a seamless, closed-loop research environment for synthetic chemistry.

Core Element 1: The Chemical Science Database

The chemical science database serves as the foundational knowledge repository for the autonomous system. It manages and organizes diverse, multimodal chemical data, providing essential support for experimental design, prediction, and optimization [6]. These databases integrate:

- Structured data from proprietary databases (e.g., Reaxys, SciFinder) and open-access platforms (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem).

- Unstructured data extracted from scientific literature, patents, and experimental reports using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques and toolkits like ChemDataExtractor and ChemicalTagger [6].

- Knowledge graphs (KGs) that provide a structured representation of data, with modern construction methods leveraging large language models (LLMs) for superior performance and enhanced interpretability [6].

Core Element 2: Large-Scale Intelligent Models

Intelligent models form the analytical core of the autonomous laboratory, enabling data processing, outcome prediction, and informed decision-making at each experimental stage [6]. These include:

- Advanced Optimization Algorithms: Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for handling large variable spaces in catalyst discovery; Bayesian optimization to minimize experimental trials; and the SNOBFIT algorithm combining local and global search strategies [6].

- Predictive Modeling: Random forest models and Gaussian processes trained iteratively on prior data to forecast experimental outcomes and exclude suboptimal paths [6].

- Iterative Theory-Experiment Fusion: Integration of automated theoretical calculations (e.g., density functional theory) to provide valuable prior knowledge and enhance adaptive learning capabilities [6].

Core Element 3: Automated Experimental Platforms

Robotic hardware systems provide the physical implementation layer, executing synthetic and analytical procedures with precision and reproducibility. These platforms include:

- Robotic manipulators for solid and liquid handling.

- Continuous flow reactors for reaction optimization.

- In-line analytical instruments (e.g., HPLC, NMR, MS) for real-time reaction monitoring.

- Mobile robotic chemists capable of autonomously conducting high-throughput experimentation [6].

Core Element 4: Integrated Management and Decision Systems

The control architecture orchestrates all components through a unified software environment that manages:

- Experimental workflow execution and scheduling.

- Data flow between databases, AI models, and robotic platforms.

- Closed-loop operation by analyzing results and initiating subsequent experiments.

- Resource allocation and safety protocols.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of AI Algorithms Used in Autonomous Laboratories

| Algorithm Type | Key Strengths | Common Applications | Convergence Efficiency | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization | Excellent for sample-efficient optimization | Reaction optimization, catalyst selection | High with limited data | Moderate |

| Genetic Algorithms (GAs) | Effective with large variable spaces | Materials discovery, formulation optimization | Gradual but thorough | Moderate to High |

| Random Forest | Handles heterogeneous data well | Property prediction, experimental outcome forecasting | Fast training | Low to Moderate |

| Gaussian Processes | Provides uncertainty estimates | Process optimization, thin-film materials | High with small datasets | High computational cost |

| Reinforcement Learning | Learns optimal actions through trial and feedback [9] | Autonomous navigation, complex task learning | Slow initial, improves with time | High |

Implementation Framework for Synthetic Chemistry

The Closed-Loop Workflow for Exploratory Synthesis

The autonomous discovery cycle operates through an integrated predict-make-measure-analyze loop specifically adapted for synthetic chemistry research:

AI-Driven Reaction Prediction: The system selects target molecules or materials based on multi-objective optimization (e.g., yield, selectivity, cost) using prior knowledge from chemical databases and predictive models.

Automated Synthesis Protocol Generation: AI generates executable synthetic protocols, including reagent selection, stoichiometry, solvent systems, and reaction conditions, often using tools like SYNTHIA or AiZynthFinder [6].

Robotic Reaction Execution: Automated platforms perform the synthesis using precisely controlled liquid handling, reactor systems, and environmental control.

In-Line Analysis and Characterization: Integrated analytical instruments (HPLC, UV-Vis, NMR, MS) provide real-time reaction monitoring and characterization.

Data Analysis and Model Refinement: Machine learning models analyze results, update predictive models, and refine understanding of structure-property relationships, informing the next cycle of experimentation.

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Optimization of Catalytic Reactions

Objective: To autonomously discover and optimize a homogeneous catalytic system for asymmetric synthesis using a closed-loop robotic platform.

Materials:

- Robotic Liquid Handling System: equipped with inert atmosphere capability

- In-line HPLC-MS: for reaction monitoring and enantioselectivity determination

- Microplate Reactor Array: with temperature control (-20°C to 150°C) and stirring capability

- Chemical Reagents: Catalyst libraries, substrate variants, solvent options

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Bayesian optimization algorithm selects initial reaction conditions based on prior knowledge, exploring catalyst structure, solvent, temperature, and concentration parameter space.

Automated Setup: Robotic platform prepares reaction mixtures in microplate reactors under inert atmosphere, executing liquid transfers with precision.

Reaction Execution: Reactions proceed with controlled heating/stirring for predetermined times or until monitored completion.

Real-time Analysis: In-line HPLC-MS samples each reaction at multiple timepoints, quantifying conversion and enantiomeric excess.

Data Integration: Analytical results are automatically processed and fed into the optimization algorithm.

Iterative Optimization: AI model updates its understanding of the reaction landscape and selects the most informative subsequent experiments to maximize enantioselectivity and yield.

Termination: The loop continues until convergence to optimal conditions or exceeding a predefined performance threshold.

Key Performance Metrics:

- Convergence rate to optimal conditions

- Number of experiments required

- Final achieved enantioselectivity and yield

- Model prediction accuracy throughout process

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Synthetic Chemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Autonomous System | Storage & Handling Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Libraries | Ligand classes (BINOL, BINAP, Salen), metal complexes (Pd, Ru, Rh) | Exploration of structure-activity relationships in reaction optimization | Inert atmosphere, temperature-controlled storage |

| Substrate Collections | Functionalized building blocks with varying electronic and steric properties | Systematic investigation of substrate scope and selectivity | Standard temperature, humidity control |

| Solvent Systems | Polar protic, polar aprotic, non-polar with varying coordination ability | Optimization of reaction medium for solubility and selectivity | Anhydrous conditions, inert atmosphere |

| Activating Agents | Peptide coupling reagents, bases, oxidants, reductants | Facilitation of specific bond-forming transformations | Moisture-sensitive storage conditions |

Case Studies in Autonomous Chemical Research

Advanced Implementation: The A-Lab for Materials Discovery

The A-Lab, developed by DeepMind, represents a cutting-edge implementation of autonomous materials research. This system utilizes computational tools, literature data, machine learning, and active learning to plan and interpret the outcomes of experiments performed by robotics, specifically addressing challenges associated with handling and characterizing solid inorganic powders [6]. The lab successfully synthesizes and characterizes novel inorganic materials with minimal human intervention by:

- Leveraging predictive models like the GNoME intelligent model for crystal structure prediction, which has expanded the number of known stable materials nearly tenfold [6].

- Employing active learning to continuously refine synthesis strategies based on experimental outcomes.

- Integrating automated characterization techniques, particularly powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), with AI-driven pattern analysis to assess synthesis success.

Chinese Advances in Autonomous Laboratories

Research in China has demonstrated significant progress in autonomous laboratories, evolving from simple iterative-algorithm-driven systems to comprehensive intelligent autonomous systems powered by large-scale models [6]. Key developments include:

- Mobile robotic chemists capable of autonomously conducting high-throughput photocatalyst selection, outperforming humans through Bayesian optimization [6].

- Fully autonomous solid-state workflows involving multiple robots for powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) experiments [6].

- Integrated AI-chemical platforms that enable self-driving chemical discovery within individual laboratories, closing the loop between prediction, synthesis, and characterization.

Future Directions and Challenges

The continued evolution of autonomous laboratories faces several technical and conceptual challenges that represent opportunities for further research and development:

Data Quality and Standardization

The performance of AI-driven approaches relies on large amounts of high-quality, structured data. However, most available experimental data suffers from significant issues including non-standardization, fragmentation, and poor reproducibility [6]. Automated robotic platforms are being rapidly developed specifically to generate high-quality experimental data in a standardized and high-throughput manner to address this fundamental limitation.

Distributed Autonomous Laboratory Networks

Most current autonomous laboratories operate in isolation with limited inter-lab communication. The next evolutionary stage involves developing these intelligent systems into distributed networks that can achieve seamless data and resource integration across multiple laboratories [6]. Such networks would enable:

- Collaborative experimentation across geographical boundaries

- Shared learning between different robotic platforms

- Standardized data protocols for chemical research

- Cloud-based resource sharing for specialized instrumentation

Algorithmic Advances for Chemical Intelligence

Future algorithmic development needs to address several key challenges:

- Multi-objective optimization balancing competing priorities (yield, cost, safety, sustainability)

- Transfer learning between different chemical domains

- Uncertainty quantification in predictive models

- Explainable AI for interpretable chemical insights

- Integration of scientific knowledge with data-driven approaches

Ethical and Safety Considerations

As autonomous systems make more decisions without human intervention, rigorous safeguards and transparent algorithms become essential to ensure trust and fairness in research outcomes [10]. Key considerations include:

- Safety protocols for unexpected chemical reactions

- Ethical AI design prioritizing safe and beneficial outcomes

- Transparent decision-making processes for regulatory compliance

- Intellectual property frameworks for AI-generated discoveries

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Autonomous vs. Traditional Laboratory Approaches

| Performance Metric | Traditional Laboratory | Autonomous Laboratory | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Throughput | 5-10 reactions/day | 100-1000 reactions/day | 20-100x |

| Data Generation Quality | Variable, operator-dependent | Standardized, reproducible | Significant improvement |

| Optimization Convergence | 20-50 iterations | 5-15 iterations | 3-5x faster |

| Resource Consumption | Higher (manual optimization) | Lower (targeted experiments) | 30-50% reduction |

| Operational Timeframe | Limited by human schedule | 24/7 continuous operation | 3-5x increase |

The shift from automation to autonomy represents a fundamental transformation in chemical research methodology, with AI emerging as the central decision-making "brain" that enables true discovery without constant human guidance. This paradigm shift addresses core challenges in exploratory synthetic chemistry by allowing researchers to navigate vast chemical spaces more efficiently, elucidate complex structure-property relationships more effectively, and accelerate the transition from fundamental research to practical application. As autonomous laboratories evolve from individual implementations to distributed networks, they hold the potential to dramatically accelerate scientific discovery across pharmaceutical development, materials science, and sustainable chemistry. The integration of embodied intelligence with robotic experimentation platforms marks the beginning of a new era in chemical research, one where human scientists are augmented by AI partners capable of conceptualizing and executing research strategies at scale and with precision previously unimaginable.

The field of synthetic chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional manual operations to increasingly automated and intelligent systems. This evolution began with dedicated, task-specific automation and has progressed to the era of mobile robotic chemists that operate with a degree of autonomy reminiscent of human researchers. This transition is critical for exploratory synthetic chemistry, where the ability to rapidly test hypotheses and characterize diverse products accelerates discovery. The move toward modular robotic systems represents a paradigm shift in laboratory workflows, enabling seamless integration of synthesis, analysis, and decision-making processes. These systems leverage artificial intelligence and advanced robotics to share existing laboratory equipment with human researchers without monopolizing instruments or requiring extensive redesign, thereby bridging the gap between traditional automation and fully autonomous experimentation [1]. This whitepaper traces the historical trajectory from the earliest forms of solid-phase synthesis to contemporary mobile robotic chemists, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical examination of the methodologies, protocols, and architectures driving this revolution.

Traditional organic synthesis has historically relied on highly trained chemists performing labor-intensive manual operations, leading to challenges with inconsistent reproducibility and limited efficiency. The first major breakthrough in automation arrived in the 1960s with Merrifield's solid-phase peptide synthesis, which automated molecular assembly by attaching peptide chains to a resin and using protective groups to enable sequential reagent addition and removal [11]. For decades, this represented the state of the art in chemical automation—effective for specialized applications but limited in scope and flexibility.

The 21st century witnessed accelerated innovation, beginning with platforms for iterative cross-coupling (e.g., Burke's work using TIDA-supported C-Csp3 bond formation) and advanced flow-based synthesis (e.g., Gilmore's automated multistep synthesizer with inline NMR and IR monitoring) [11]. A significant milestone was the development of the Chemputer by Cronin's group, which used a chemical description language (XDL) to standardize and automate synthetic procedures extracted from scientific literature, demonstrating the assembly of pharmaceuticals with superior yields and purity compared to manual methods [12] [11]. This evolution culminated in the recent emergence of mobile robotic chemists—such as the system described by Burger et al., which autonomously performed 688 reactions over eight days—and AI-integrated platforms like Jiang's AI-Chemist, which encompasses the entire process from synthetic planning to execution and machine learning [11]. These systems mark the transition from stationary, dedicated automation to flexible, mobile systems capable of operating in dynamic laboratory environments.

Table: Major Historical Developments in Automated Synthesis

| Time Period | Key Development | Representative Technology | Primary Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | Solid-Phase Synthesis | Merrifield's Peptide Synthesizer | Automation of sequential synthesis on a solid support |

| Early 2000s | Iterative Cross-Coupling | Automated Synthesis Machines | C-C bond formation with commercial building blocks |

| 2010s | Flow Chemistry & Inline Analysis | Radial Flow Synthesizers | Continuous flow processes with real-time monitoring |

| 2018-2020 | Chemical Programming | Chemputer Platform | Standardization via chemical description language (XDL) |

| 2020-Present | Mobile Robotic Chemists | Autonomous Mobile Robots | Free-roaming robots using multiple characterization techniques |

Core Principles of Modern Modular Robotic Systems

Modern modular robotic systems for exploratory synthetic chemistry are built upon several foundational principles that distinguish them from earlier automation approaches. These principles enable the flexibility and intelligence required for autonomous discovery in complex chemical spaces.

Modularity and Distributed Instrumentation

Contemporary systems employ a modular workflow where physically separated synthesis and analysis modules are connected by mobile robots for sample transportation and handling [1]. This architecture differs fundamentally from bespoke automated equipment with hard-wired characterization techniques. Instead, mobile robots act as the physical linkage between independent modules—such as automated synthesis platforms, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometers (UPLC-MS), and benchtop nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers—allowing instruments to be shared with human researchers and located anywhere in the laboratory [1]. This distributed approach creates an inherently expandable system that can incorporate additional instruments as needed, limited only by laboratory space constraints.

Orthogonal Analytical Characterization

Unlike automated systems designed to maximize a single figure of merit (e.g., yield), exploratory synthesis requires characterization capable of identifying diverse potential products. Modern systems address this by combining multiple characterization techniques—typically UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR—to achieve a standard comparable to manual experimentation [1]. This orthogonal approach is essential for capturing the diversity inherent in modern organic chemistry and mitigates the uncertainty associated with unidimensional measurements. For example, in supramolecular chemistry, self-assembly processes can produce complex product mixtures that require multimodal data for unambiguous identification [1].

Autonomous Decision-Making with Heuristic Reasoning

True autonomy requires systems that can interpret analytical data and make decisions without human intervention. Modern platforms employ heuristic decision-makers that process orthogonal measurement data to select successful reactions for further study [1]. These algorithms apply experiment-specific pass/fail criteria to both MS and NMR analyses, combining the results to determine subsequent workflow steps. This "loose" heuristic approach remains open to novelty and chemical discovery, unlike optimization-focused algorithms that might overlook unexpected results [1]. The system also automatically checks the reproducibility of screening hits before scale-up, mimicking human experimental protocols.

Technical Architectures and Methodologies

Mobile Robotic Platforms for Distributed Workflows

The architecture of modern autonomous laboratories centers around mobile robotic agents that navigate laboratory environments to operate equipment and transport samples. These systems represent a significant advancement over fixed-base robots, which lack mobility to interact with spatially distributed instruments [13]. Recent implementations include both robots equipped with linear translational tracks and wheeled platforms, with the latter offering greater workspace accessibility [13].

A key technical challenge involves addressing the navigation inaccuracies inherent to mobile bases, which can compromise precision-critical manipulation tasks. Solutions include tactile-based localization methods (e.g., cube-mounted location systems) that achieve high accuracy but require static infrastructure, and vision-based methods (e.g., fiducial markers, LIDAR, learning-based keypoint detection) that offer greater adaptability for dynamic workflows [13]. These mobile systems physically integrate instruments without requiring extensive modification—typically needing only simple adaptations like automated doors for robot access [1].

The LIRA Module: Closed-Loop Error Detection and Correction

The LIRA (Localization, Inspection, and Reasoning) module represents a recent advancement in addressing the open-loop manipulation problem common in self-driving laboratories (SDLs) [13]. Unlike traditional robotic manipulation that assumes flawless execution, LIRA provides real-time error detection and correction through vision-language models (VLMs).

Table: Technical Components of the LIRA Module

| Component | Function | Implementation | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localization | Precise positioning for manipulation tasks | Vision-based with calibration board; uses ArUco marker pose detection | High localization accuracy; 10x reduction in localization time [13] |

| Inspection | Automated visual error detection | Fine-tuned Vision-Language Model (VLM) on chemistry lab dataset | 97.9% success rate in error inspection [13] |

| Reasoning | Decision-making for error recovery | Natural language processing of visual inputs | Enables dynamic adaptation to workflow variations |

| Edge Computing | Real-time processing | Server layer on edge device | Reduces manipulation time by 34% in solid-state workflows [13] |

LIRA's architecture comprises three layers: (1) a robot client interface integrated into existing workflow scripts, (2) a communication layer managing data exchange over local networks using SOAP and Flask protocols, and (3) a server layer on an edge device providing computational power for real-time image processing and VLM execution [13]. The system operates through a structured workflow: after a mobile robot navigates to a station, the arm moves to a predefined position for visual calibration, the client sends an ArUco pose request, and a 6×1 vector representing the marker pose is returned to update manipulation-related frames [13]. During task execution, inspection requests formulated as input prompts are transmitted with camera images to LIRA, which returns inspection and reasoning results to guide subsequent actions.

Integrated Synthesis Platforms with Real-Time Feedback

Advanced synthesis platforms like the Chemspeed ISynth and Chemputer form the core of modern automated synthesis workflows. These systems integrate reagent storage, reaction preparation modules, multiple reactor configurations, and purification systems in coordinated architectures [1] [12]. The Chemputer, for example, uses the chemical description language XDL to provide methodological instructions for individual synthetic steps, integrating automation with bench-scale techniques through natural language processing algorithms [12] [11].

A critical advancement in these platforms is the incorporation of real-time analytical feedback from techniques including on-line NMR, liquid chromatography, and infrared spectroscopy [12]. This enables dynamic adjustment of process conditions during reaction progression. For instance, in the synthesis of [2]rotaxane molecular machines, integrated on-line NMR and liquid chromatography provided feedback that informed adjustments throughout the divergent four-step synthesis and purification process, which averaged 800 base steps over 60 hours [12].

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Workflows

Protocol: Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis Using Mobile Robots

This protocol outlines the methodology for conducting autonomous exploratory synthesis using mobile robotic systems, based on the workflow described by [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Mobile robotic platform with manipulator

- Automated synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth)

- UPLC-MS system

- Benchtop NMR spectrometer

- Central control software and database

Procedure:

- Workflow Initialization:

- Program the synthesis sequence in the automated synthesis platform

- Define experiment-specific pass/fail criteria for MS and NMR analyses in the heuristic decision-maker

- Initialize parameters for robotic manipulation (station names, target names, fiducial marker IDs)

Synthetic Execution:

- Execute parallel synthesis operations in the automated synthesis platform

- Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer takes aliquots of each reaction mixture

- Reformats samples separately for MS and NMR analysis

Sample Transportation and Analysis:

- Mobile robots transport samples to appropriate instruments (UPLC-MS and NMR)

- Implement automated data acquisition using customizable Python scripts

- Save resulting data to a central database

Data Analysis and Decision-Making:

- Process UPLC-MS and ¹H NMR data using heuristic algorithms

- Apply binary pass/fail grading to each analysis based on predefined criteria

- Combine results from orthogonal analyses to determine subsequent workflow steps

- Select successful reactions for scale-up or further elaboration

- Automatically verify reproducibility of screening hits before progression

Iterative Cycle:

- Execute subsequent synthesis operations based on decision-maker instructions

- Continue synthesis-analysis-decision cycles without human intervention

Applications:

- Structural diversification chemistry

- Supramolecular host-guest chemistry

- Photochemical synthesis

- Library synthesis for drug discovery

Protocol: Closed-Loop Error Correction Using LIRA

This protocol details the implementation of the LIRA module for real-time error detection and correction in autonomous workflows [13].

Materials and Equipment:

- LIRA edge computing module

- Camera system mounted on robotic manipulator

- Calibration board with fiducial markers

- Client-server communication infrastructure

Procedure:

- System Initialization:

- Navigate mobile robot to target station

- Move robotic arm to predefined calibration position

- Initialize communication between robot client and LIRA server

Visual Localization:

- Capture image of workspace using onboard camera

- Send ArUco pose request to LIRA server via network

- Receive 6×1 vector representing marker pose

- Update manipulation-related frames based on pose data

Task Execution and Monitoring:

- Execute manipulation task (e.g., vial placement, instrument operation)

- At critical error-prone points, capture current workspace image

- Formulate inspection request as natural language prompt

Inspection and Reasoning:

- Transmit image and prompt to LIRA server

- Process input using fine-tuned VLM

- Return inspection results and reasoning to client

Error Recovery:

- Apply InspectionHandler to interpret LIRA response

- Execute appropriate corrective action based on reasoning results

- Repeat inspection until successful task completion

- Proceed to next workflow step

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Modern autonomous systems have demonstrated significant performance improvements across multiple metrics compared to traditional automated approaches. The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from recent implementations:

Table: Performance Metrics of Autonomous Chemistry Platforms

| Platform/Technology | Key Performance Metric | Result | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot with LIRA Module [13] | Error Inspection Success Rate | 97.9% | Enables closed-loop error correction in dynamic environments |

| Mobile Robot with LIRA Module [13] | Manipulation Time Reduction | 34% decrease | Faster task completion through optimized localization |

| LIRA Localization [13] | Localization Time | 10x reduction | High-speed calibration for workflow efficiency |

| Autonomous Mobile Robot [1] | Analytical Techniques | UPLC-MS + NMR | Orthogonal characterization comparable to manual standards |

| Chemputer Rotaxane Synthesis [12] | Process Steps | 800 steps over 60 hours | Manages complex multi-step synthesis autonomously |

| AI-Chemist Platform [11] | Functional Scope | End-to-end operation | Manages synthesis planning, execution, and machine learning |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Synthesis Workflows

| Item | Function | Application Example | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkyne Amines (1-3) [1] | Building blocks for combinatorial condensation | Parallel synthesis of ureas and thioureas | Used with isothiocyanates/isocyanates for library generation |

| Isothiocyanate (4) & Isocyanate (5) [1] | Electrophilic coupling partners | Structural diversification chemistry | React with alkyne amines to form diverse scaffolds |

| Tetramethyl N-methyliminodiacetic acid (TIDA) [11] | Supporting ligand for C-C bond formation | Automated synthesis of small molecules | Enables C-Csp3 bond formation in synthesis machines |

| ArUco Fiducial Markers [13] | Visual reference for robot localization | Precision manipulation tasks | Enables high-accuracy positioning in vision-based systems |

| Commercial Building Blocks [11] | Diverse starting materials | Automated synthesis with >5000 options | Supports creation of numerous small molecule targets |

| Chlorophyll a | Chlorophyll a Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Azure B | Azure B, CAS:1231958-32-9, MF:C15H16ClN3S, MW:305.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution from solid-phase synthesis to mobile robotic chemists represents a fundamental transformation in how chemical research is conducted. Modern modular robotic systems have demonstrated the capability to perform complex, multi-step syntheses with integrated analytical characterization and decision-making, significantly advancing the field of exploratory synthetic chemistry. These systems address critical challenges in reproducibility, efficiency, and discovery throughput that have long constrained traditional manual approaches.

Future developments in autonomous chemistry will likely focus on several key areas: improved seamless integration of synthetic platforms with analytical instruments and computational systems; enhanced AI-driven synthesis planning that more effectively captures existing chemical knowledge; development of more user-friendly interfaces and universal chemical programming languages; and creation of more compact, affordable systems accessible to a broader range of laboratories [11]. As these technologies mature, organic chemists will be increasingly liberated from repetitive experimental tasks, allowing greater focus on creative strategic questions—what to synthesize and why—rather than the mechanics of synthesis execution [11]. This shift promises to accelerate scientific discovery and open new frontiers in molecular design and development.

Diagram: Autonomous Chemistry Workflow

Diagram: LIRA Closed-Loop Error Correction

From Theory to Bench: Implementing Modular Workflows for Complex Chemistry

In the evolving landscape of exploratory synthetic chemistry, the demand for more adaptive, efficient, and intelligent research systems has never been greater. This whitepaper details a specialized workflow architecture designed to meet this challenge by integrating synthesis, analysis, and decision cycles within a framework of modular robotic systems. The core thesis is that a purpose-built workflow architecture, leveraging modularity and automation, can create a self-optimizing research platform capable of accelerating discovery, particularly in pharmaceutical development. By treating the research process not as a series of discrete steps but as a continuous, data-driven cycle, this system promises to enhance reproducibility, enable real-time adaptation, and maximize the utility of both human and robotic resources.

Core Workflow Concepts & Typology

A workflow is fundamentally a sequence of tasks organized to achieve a specific outcome, serving as a roadmap that guides a process from inception to completion [14]. In the context of automated research, selecting the appropriate workflow type is critical for success.

- Sequential Workflow: This model executes a series of steps in a strict, linear sequence, where each task must be completed before the next can begin [14] [15]. It is best suited for straightforward, well-defined synthetic pathways where the process is predictable and requires no deviation.

- State Machine Workflow: This model incorporates loops and decision points, allowing the process to move between different states based on specific outcomes or analytical results [14] [15]. It is essential for exploratory research, as it can adapt to failed reactions or unexpected data by branching to alternative synthesis or purification paths.

- Rules-Driven Workflow: This model automates tasks based on predetermined business rules or logical criteria, often expressed as "if-then" statements [14] [15]. In a chemistry context, this could automatically trigger a different workup procedure if analysis detects a particularly stubborn impurity.

These workflow models are orchestrated by a Workflow Management System (WMS), a software solution designed to define, execute, monitor, and optimize business processes [16]. The primary purpose of a WMS is to increase organizational efficiency by automating workflows, reducing manual intervention, and ensuring consistent execution [16]. Its key features include a process modeler for designing workflows, a workflow engine for execution, task management for assignment and tracking, and robust integration tools to connect with other laboratory instruments and software [16].

System Architecture of a Workflow Management System

The functionality of a WMS is grounded in its underlying architecture, which determines its scalability, flexibility, and integration potential. For a research environment requiring high adaptability, certain architectural patterns are more suitable.

- Microservices Architecture: This approach structures the WMS as a collection of small, independent services, each responsible for a discrete function [16]. This is ideal for modular robotic systems, as services for "Synthesis Control," "Analytical Data Processing," or "Decision Logic" can be developed, scaled, and updated independently. This aligns with the modular philosophy, allowing the overall system to remain agile and resilient [16].

- Event-Driven Architecture: This architecture centers on the production, detection, and reaction to events, making the system highly responsive to real-time changes [16]. In a laboratory setting, an event could be "Reaction Completed," "MS Data Ready," or "Purity Threshold Met," which then automatically triggers the next step in the workflow, such as initiating a purification or starting a subsequent reaction.

The core components of a WMS architecture that bring these models to life include [16]:

- Process Definition: The foundation where business processes are mapped into a digital format using standards like Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN).

- Execution Engine: The heart of the system that interprets process definitions and manages the execution of workflow instances.

- Task Management: Ensures that work is assigned to the correct resources (human or robotic) and is completed in the correct order.

- Integration Layer: Allows the WMS to communicate with other systems and databases via APIs and connectors, creating a cohesive laboratory ecosystem.

Integration with Modular Robotic Systems

Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems are autonomous kinematic machines with variable morphology. Beyond conventional actuation, sensing, and control, these robots can deliberately change their shape by rearranging the connectivity of their parts to adapt to new circumstances, perform new tasks, or recover from damage [17]. This capability aligns perfectly with the needs of exploratory synthetic chemistry, where the optimal physical configuration of laboratory hardware may need to change for different reaction sequences or purification techniques.

The motivation for integrating these systems is twofold: functional advantage and economic advantage [17]. Functionally, a modular robotic system is more robust and adaptive than a fixed-configuration system. It can reassemble to form new morphologies better suited to new tasks. Economically, a single set of mass-produced modules can create a wide array of complex machines, potentially lowering overall costs [17].

From an architectural perspective, these systems are often classified as follows [17]:

- Lattice Architecture: Modules connect at points in a virtual grid, similar to atoms in a crystal. This simplifies mechanical design and reconfiguration planning.

- Chain Architecture: Modules are not confined to a grid and can reach any point in space, offering greater versatility but increased computational complexity for planning.

- Hybrid Architecture: Combines advantages of both lattice and chain architectures.

A key research focus in this field is the automatic synthesis of both robot design and controllers, enabling a reactive control policy that can generalize to new, unseen robot designs formed from the modules [18]. This capability is critical for a chemistry platform that must constantly adapt its physical form.

<100: Modular Robotic Workflow

Application in Synthetic Chemistry Workflows

The integration of workflow architecture and modular robotics finds a powerful application in modern synthetic chemistry, particularly with the adoption of flow chemistry. Flow chemistry offers significant advantages over traditional batch processes, including improved mass and heat transfer, enhanced safety, increased efficiency, and superior scalability [19].

A typical organic chemistry workflow involves multiple steps, from initial literature review and synthesis planning to the execution of reactions, work-up, purification, and isolation of the final compound [20]. This multi-step process is an ideal candidate for automation and optimization through a state-machine workflow model.

For instance, the synthesis of complex pharmaceuticals like Verubecestat showcases the power of flow chemistry, where efficient mixing in flow reactors enhances selectivity and yield [19]. Furthermore, flow chemistry enables multi-step synthesis by integrating multiple reactions into a continuous process, which reduces the need for intermediate purification and significantly improves overall efficiency [19]. The continuous synthesis of the antibiotic Linezolid demonstrates this potential for enhanced efficiency, safety, and scalability [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and equipment essential for implementing automated synthesis workflows.

Table: Essential Materials for Automated Synthesis Workflows

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Microwave Reactor | Used for organic synthesis to rapidly heat reaction mixtures, often reducing reaction times from hours to minutes [20]. |

| Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) | A critical analytical tool for reaction monitoring, identifying compounds, and assessing reaction completion and purity [20]. |

| Automated Flash Purification System | Purifies complex reaction mixtures using a solid media and solvents to separate components; often includes UV, ELSD, or mass detection to isolate target compounds [20]. |

| Phase Separators & Drying Cartridges | Cartridge-based tools used during the work-up to separate liquid phases (e.g., organic and aqueous) and scavenge water from the solution [20]. |

| High-Speed Evaporator | Rapidly removes solvent from a sample after extraction or purification to isolate a solid or oil product [20]. |

| Photocatalyst (e.g., decatungstate) | Enables photochemical reactions under flow conditions, allowing for transformations like C(sp³)–H bond amination that are challenging in batch [19]. |

| AChE/BChE-IN-1 | AChE/BChE-IN-1, CAS:39669-35-7, MF:C8H13NO2, MW:155.19 g/mol |

| (+)-Sparteine sulfate pentahydrate | (+)-Sparteine sulfate pentahydrate, MF:C15H38N2O9S, MW:422.5 g/mol |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides a detailed, generalized methodology for a self-optimizing chemical synthesis loop, integrating the concepts of workflow management and modular robotics.

Protocol: Automated Multi-Step Synthesis with Real-Time Analysis and Decision Making

Objective: To autonomously synthesize a target organic compound through a multi-step pathway, with in-line analysis and decision cycles that adapt the process based on yield and purity thresholds.

Workflow Model: State Machine

Prerequisites:

- Modular flow chemistry system with reconfigurable reactor modules.

- In-line analytical instrumentation (e.g., LC/MS, IR).

- Integrated WMS with a rules engine capable of executing BPMN-defined processes.

Methodology:

Process Definition & Robot Configuration:

- The target molecule and its synthetic pathway (e.g., a two-step sequence with an intermediate purification) are defined within the WMS using a visual process modeler [16].

- The WMS instructs the modular robotic system to configure itself into the required morphology (e.g., assembling a sequence of reactor, mixer, and heater modules for the first synthetic step) [17].

Synthesis Execution & Reaction Monitoring:

- The workflow engine initiates the process, controlling pumps to introduce reagents into the flow system [16].

- Reaction parameters (temperature, pressure, flow rate) are continuously monitored and controlled by the WMS.

- Upon completion of the residence time, the reaction stream is automatically diverted to the in-line LC/MS for analysis [20].

Analysis & Decision Cycle:

- The analytical data is processed in real-time. The WMS's rules engine evaluates the data against pre-defined criteria.

- Rule 1 (Synthesis Success):

IF(Yield of Intermediate > 80% AND Major Impurity < 5%)THEN(Proceed to Step 2 Purification). - Rule 2 (Synthesis Failure):

IF(Yield of Intermediate < 80%)THEN(Trigger Reconfiguration & Re-synthesis). The system may reconfigure modules to adjust reactor volume or temperature and repeat the step [17].

Purification & Isolation:

- If the synthesis is successful, the WMS reconfigures the robotic platform for purification, connecting the output to an automated flash chromatography system [20].

- The purified intermediate is analyzed again (LC/MS). If purity thresholds are met, it is evaporated and re-dissolved for the next step [20]. If not, the workflow may branch to an alternative purification method.

Iteration and Final Output:

- Steps 2-4 are repeated for subsequent synthetic steps, with the workflow state machine navigating the path based on analytical results at each stage.

- The final, purified compound is isolated, and data from the entire process is logged for reproducibility and future optimization.

The logical flow of this adaptive protocol, driven by analytical results, can be visualized as follows:

<100: Experimental Protocol Flow

Data Visualization and Reporting

Effective data visualization is critical for researchers to quickly understand the outcomes of automated experiments and make informed decisions. The choice of visualization depends on the type of data being presented.

- Quantitative Data: Data that can be represented numerically. This is divided into:

- Discrete Data: Characterized by a small number of distinct possible responses (e.g., number of reaction attempts). Bar charts are ideal for this data type [21].

- Continuous Data: Characterized by many different possible values (e.g., reaction yield, temperature, purity percentage). Histograms are used when visualizing the distribution of a continuous dataset [21].

Table: Data Visualization Selection Guide

| Data Type | Example in Chemistry Context | Recommended Visualization |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative/Categorical | Types of catalysts used, success/failure status of reactions | Bar Chart [22] [21] |

| Quantitative Discrete | Number of synthetic steps, number of modules in a robot configuration | Bar Chart [22] [21] |

| Quantitative Continuous | Reaction yield distribution across 100 experiments, purity measurements of final products | Histogram [21] |

| Relationship (Categorical vs. Quantitative) | Final yield achieved by different robotic configurations | Bar Chart [21] |

| Performance Benchmarking | Actual yield vs. target yield for a series of compounds | Bullet Chart [22] |

For reporting and dashboard creation within the WMS, bar charts and column charts are universally useful for comparing values across categories due to their simplicity and ease of understanding [22]. For more specific tasks, such as benchmarking the performance of a synthetic route against a target yield, a bullet chart is a space-efficient and effective choice [22].

The integration of a robust workflow architecture with modular robotic systems presents a paradigm shift for exploratory synthetic chemistry research. This technical guide has outlined how state-machine and rules-driven workflows, executed by a microservices-based WMS, can direct the physical actions of self-reconfiguring robots to create a closed-loop, adaptive research platform. The result is a system that not only automates repetitive tasks but also intelligently navigates the inherent uncertainties of chemical synthesis. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting this architecture translates to accelerated discovery cycles, enhanced reproducibility, and a more efficient use of resources, ultimately pushing the boundaries of what is possible in synthetic chemistry.