Optimizing Organic Reaction Yields with Machine Learning: From Data to Discovery

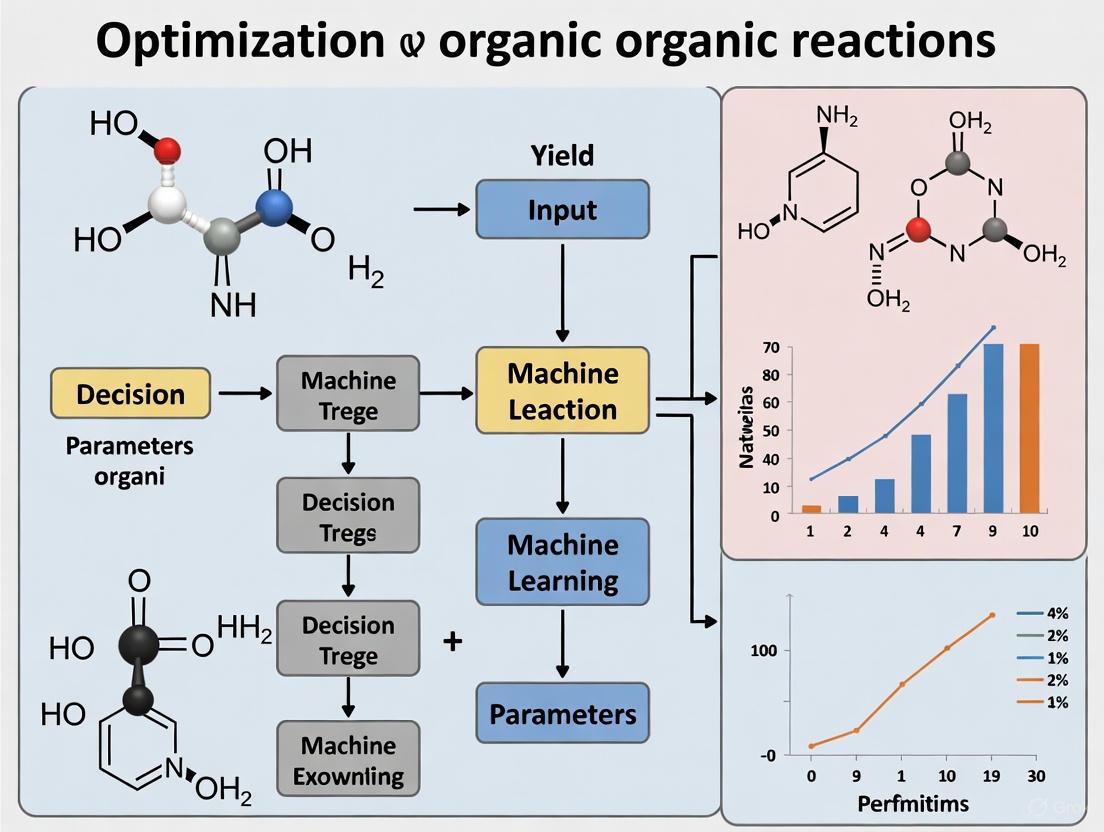

This article explores the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) on optimizing yields in organic synthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Optimizing Organic Reaction Yields with Machine Learning: From Data to Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) on optimizing yields in organic synthesis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational shift from traditional one-variable-at-a-time methods to data-driven approaches, detailing the integration of ML with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms for rapid parameter screening. The content provides a practical guide for troubleshooting ML models and optimizing reactions, and it examines rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of ML-driven versus traditional outcomes. By synthesizing these facets, the article serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging ML to accelerate research, improve sustainability, and unlock novel chemical discoveries.

The New Paradigm: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Organic Synthesis

The Limitations of Traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental weakness of the one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach? OVAT optimization fails to account for interactions between variables. In complex organic syntheses, parameters like temperature, catalyst amount, and solvent concentration often interact in non-linear ways. By changing only one variable while keeping others fixed, OVAT methods cannot detect these synergistic or antagonistic effects, potentially missing the true optimal conditions and leading to suboptimal reaction yields [1] [2].

Q2: How does OVAT compare to multivariate methods in finding global optima? OVAT is highly prone to finding local optima rather than the global optimum. Since it explores the parameter space sequentially rather than holistically, it often gets trapped in a local performance peak. Multivariate optimization methods, especially AI-guided approaches, simultaneously explore multiple dimensions of the parameter space, significantly increasing the probability of locating the global optimum for your reaction [2] [3].

Q3: Why is OVAT particularly inefficient for optimizing reactions with many parameters?

The inefficiency grows exponentially with parameter count. For a reaction with n parameters, OVAT must explore each dimension separately, requiring significantly more experiments to achieve comparable optimization. This makes it practically infeasible for complex reactions with multiple categorical and continuous variables, where multivariate approaches can screen variables simultaneously using sophisticated experimental designs [4] [2].

Q4: What types of critical insights does OVAT miss compared to modern optimization techniques? OVAT fails to reveal:

- Interaction effects between variables (e.g., how temperature and catalyst loading jointly affect yield)

- The shape of the response surface across the parameter space

- True optimal regions that exist between tested variable levels

- Comprehensive understanding of reaction robustness [2]

Modern machine learning-guided optimization creates predictive models of the entire parameter space, identifying not just single optimum points but optimal regions and interaction patterns [1] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Suboptimal Yields Despite Extensive OVAT Optimization

Symptoms: You've systematically optimized each parameter individually but cannot achieve the reported yields from literature or your yield plateaus below theoretical maximum.

Diagnosis: This typically indicates significant variable interactions that OVAT cannot detect. The true optimum exists in a region of parameter space where multiple variables are simultaneously adjusted.

Solution:

- Transition to Design of Experiments (DoE): Implement a screening design (such as Plackett-Burman or fractional factorial) to identify the most influential parameters and their key interactions [2].

- Apply Response Surface Methodology: Once key variables are identified, use central composite or Box-Behnken designs to model the nonlinear response surface [2].

- Validate with Confirmation Experiments: Run 3-5 confirmation experiments at the predicted optimum to verify the model's accuracy.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of OVAT vs. Multivariate Optimization Performance

| Metric | OVAT Approach | Multivariate Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Experiments required (for 5 parameters) | 25-30 | 16-20 |

| Ability to detect interactions | None | Comprehensive |

| Probability of finding global optimum | Low (est. 30-40%) | High (est. 85-95%) |

| Experimental time requirement | High | Reduced by 30-50% |

| Robustness information | Limited | Comprehensive [4] [2] |

Problem: Unreproducible or Sensitive Reaction Outcomes

Symptoms: Reaction performance varies significantly between batches despite apparently identical conditions. Small deviations in parameters cause large yield fluctuations.

Diagnosis: OVAT has likely identified a locally optimal but narrow and unstable operating point rather than a robust optimum.

Solution:

- Implement Robustness Testing: Use DoE to deliberately vary parameters around your current conditions and measure the effects on yield and selectivity.

- Identify Critical Process Parameters: Determine which variables have the greatest impact on performance variability.

- Locate Robust Operating Regions: Use contour plots and response surface models to find regions where yield remains high despite normal parameter fluctuations [2].

- Apply Bayesian Optimization: For particularly complex spaces, implement AI-guided optimization that explicitly balances performance with robustness [3].

Problem: Inefficient Resource Utilization During Optimization

Symptoms: Spending excessive time and materials on optimization with diminishing returns. Difficulty justifying optimization resource allocation for new reactions.

Diagnosis: OVAT's sequential nature creates inherent inefficiency in experimental resource utilization.

Solution:

- Adopt High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Implement parallel experimentation using automated platforms like Chemspeed SWING systems or custom HTE rigs [1].

- Implement Machine Learning-Guided Optimization: Use algorithms like Bayesian optimization to intelligently select the most informative next experiments based on all accumulated data [5] [3].

- Utilize Closed-Loop Systems: Deploy fully automated optimization platforms where AI algorithms directly control robotic fluid handling systems, reducing human intervention and increasing throughput [1].

Diagram: OVAT Limitations vs. Multivariate Advantages - This flowchart visualizes the core limitations of the OVAT approach compared to key advantages offered by multivariate optimization methods.

Experimental Protocol: Transitioning from OVAT to Multivariate Optimization

Objective: Systematically replace OVAT methodology with efficient multivariate optimization for yield optimization of organic reactions.

Step 1: Parameter Screening

- Identify 5-8 potentially influential continuous and categorical variables

- Use fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design to screen for significance

- Execute 12-16 experiments based on the screening design

- Statistically analyze results to identify 3-4 most critical parameters [2]

Step 2: Response Surface Modeling

- For the critical parameters identified in Step 1, implement a response surface design

- Central composite design for continuous variables or D-optimal design for mixed variables

- Execute 20-30 experiments to model the response surface

- Build mathematical models relating parameters to yield and selectivity [2]

Step 3: AI-Guided Optimization (Advanced)

- For complex spaces with >4 critical parameters, implement machine learning guidance

- Use Bayesian optimization with Gaussian process regression

- Iteratively run 4-8 experiments per cycle based on acquisition function

- Continue until convergence to optimum (typically 4-6 cycles) [3]

Step 4: Validation and Robustness Testing

- Run 5-7 confirmation experiments at predicted optimum

- Validate model accuracy and performance

- Test robustness by varying parameters within expected operational ranges

- Document design space and establish control strategy

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization Workflows

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemspeed SWING Platform | Automated parallel reaction execution | Enables 96-well plate screening; ideal for categorical variable optimization [1] |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithms | Intelligent experiment selection | Balances exploration/exploitation; available in platforms like CIME4R [3] |

| MEDUSA Search Engine | Mass spectrometry data analysis | ML-powered analysis of HRMS data for reaction discovery [6] |

| CIME4R Platform | Visual analytics for RO data | Open-source tool for analyzing optimization campaigns and AI predictions [3] |

| High-Throughput Batch Reactors | Parallel reaction screening | Custom or commercial systems for simultaneous parameter testing [1] |

Advanced Solution: Implementing AI-Guided Optimization

For research groups transitioning beyond basic multivariate optimization, AI-guided approaches offer the next evolutionary step:

Implementation Steps:

- Data Infrastructure: Establish structured data collection using platforms like CIME4R that capture all experimental parameters and outcomes [3].

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate machine learning algorithms based on your data characteristics:

- Random Forests: For smaller datasets (<100 experiments)

- Gaussian Process Regression: For continuous parameter spaces

- Neural Networks: For very large datasets (>1000 experiments) [5]

- Closed-Loop Integration: Connect AI prediction systems with automated laboratory equipment for fully autonomous optimization [1] [7].

- Human-AI Collaboration: Use visual analytics tools to understand model predictions and maintain scientific oversight [3].

Key Benefits:

- Reduces experimental burden by 40-60% compared to OVAT

- Uncovers complex non-linear relationships inaccessible to human intuition

- Creates predictive models that accelerate future reaction development

- Enables simultaneous optimization of multiple objectives (yield, selectivity, cost) [5] [3]

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers applying Core ML to organic reaction optimization.

Core ML Tools & Conversion

Q1: What is the recommended method for converting a PyTorch model to Core ML?

For Core ML Tools version 4 and newer, you should use the Unified Conversion API. The previous method, onnx-coreml, is frozen and no longer updated [8] [9].

Q2: My pre-trained Keras model is from TensorFlow 1 (TF1). How can I convert it?

The coremltools.keras.convert converter is deprecated. For older Keras.io models using TF1, the recommended workaround is to export it as a TF1 frozen graph def (.pb) file first, then convert this file using the Unified Conversion API [8] [9].

Q3: How can I define a new Core ML model from scratch?

You can use the MIL builder API, which is similar to torch.nn or tf.keras APIs for model construction [8] [9].

Troubleshooting Common Errors

Q4: I am encountering high numerical errors after model conversion. How can I fix this? For neural network models, set the compute unit to CPU during conversion or when loading the model to use a higher-precision execution path [8] [9].

Q5: I get an "Unsupported Op" error during conversion. What should I do?

First, ensure you are using the newest version of Core ML Tools. If the error persists, file an issue on the coremltools GitHub repo. A potential workaround is to write a translation function from the missing operation to existing MIL operations [8] [9].

Q6: How do I handle image preprocessing when converting a torchvision model?

Preprocessing parameters differ but can be translated by setting the scale and bias for an ImageType [8] [9].

Model Inspection & Optimization

Q7: How can I find or change the input and output names of my converted model? Input and output names are automatically picked up from the source model. You can inspect them after conversion [8] [9]:

Use the rename_feature API to update these names.

Q8: How can I make my model accept flexible input shapes to run on the Apple Neural Engine?

Specify a flexible input shape using EnumeratedShapes. This allows the model to be optimized for a finite set of input shapes during compilation [8].

Q9: Why should I use Core ML Tools' optimize.torch for quantization instead of PyTorch's defaults?

PyTorch's default quantization settings are not optimal for the Core ML stack and Apple hardware. Using coremltools.optimize.torch APIs ensures the correct settings are applied automatically for optimal performance [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools for ML in Reaction Optimization

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reaction Dataset | Curated data containing reactants, products, and reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, catalyst) used to train ML models. |

| Graph-Based Representation | Represents molecules as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges), allowing models to learn structural relationships [10]. |

| Elementary Step Classifier | An ML model component that identifies fundamental reaction steps (e.g., bond formation/breaking), crucial for mechanism prediction [10]. |

| Reactive Atom Identifier | An ML model component that detects which atoms are actively involved in a reaction step, providing atomic-level insight [10]. |

| Attention Mechanism | A model component that helps visualize and identify the most relevant parts of a molecule during a prediction, aiding interpretability [10]. |

| Core ML Tools | Apple's framework for converting and deploying pre-trained models from PyTorch or TensorFlow onto Apple devices [8] [9] [11]. |

| Unified Conversion API | The primary API in Core ML Tools for converting models from various frameworks (TensorFlow 1/2, PyTorch) into the Core ML format [8] [9]. |

| 2-Methoxy-5-sulfamoylbenzoic Acid-d3 | 2-Methoxy-5-sulfamoylbenzoic Acid-d3 |

| PK 11195 | PK 11195, CAS:85340-56-3, MF:C21H21ClN2O, MW:352.87 |

Table 2: Core ML Tools Version Highlights

| Version | Key Features & Changes |

|---|---|

| coremltools 7 | Added more APIs for model optimization (pruning, quantization, palettization) to reduce storage, power, and latency [9]. |

| coremltools 6 | Introduced model compression utilities and enabled Float16 input/output types [8] [9]. |

| coremltools 5 | Introduced the .mlpackage directory format and a new ML program backend with a GPU runtime [8] [9]. |

| coremltools 4 | Major upgrade introducing the Unified Conversion API and Model Intermediate Language (MIL) [8] [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Workflow for Building an ML Model for Reaction Prediction

This diagram outlines the key steps in developing a machine learning model to predict and optimize organic chemical reactions.

Protocol: Converting a Pre-trained Model for On-Device Inference

Objective: To convert a machine learning model, trained on chemical reaction data, into the Core ML format for deployment and prediction on Apple devices.

Materials:

- A pre-trained model (e.g., from PyTorch or TensorFlow).

- Python environment with

coremltoolsinstalled. - Example input data for tracing the model.

Method:

- Preparation: Install the latest version of

coremltoolsusing pip. - Load Source Model: Load your pre-trained model in its original framework.

- Trace with Example Input: Prepare an example input that matches the shape and type your model expects. This is required for the converter to trace the model's execution path.

- Perform Conversion: Use the

coremltools.convert()API. For PyTorch models, pass the model and the example input. For TensorFlow 2 (tf.keras) models, pass the model directly. - Save the Model: Save the converted model with the

.mlpackageextension. - Integrate into Xcode: Drag the saved

.mlpackagefile into your Xcode project. You can now use the generated Swift classes to make predictions in your app.

Protocol: Implementing a Custom Node Color Function for Model Decision Visualization

Objective: To enhance the interpretability of a decision tree model (or similar) by customizing the colors of nodes in its visualization, making it easier to identify patterns related to reaction outcomes.

Materials:

- A trained Scikit-learn decision tree model.

- Python environment with

matplotlibandsklearn.

Method:

- Plot the Basic Tree: Use

plot_treewithfilled=Trueto generate the initial visualization. - Define a Color Function: Create a function that maps node values (like class purity or regression value) to specific hex color codes.

- Apply Custom Colors: While

plot_treedoesn't directly accept a color function, you can access the plotted nodes after the fact and modify their colors based on your function. - Ensure Readability: Calculate the luminance of your chosen background color and set the text color to white or black dynamically for optimal contrast [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main types of machine learning models used for reaction outcome prediction? Machine learning models for reaction outcome prediction are broadly categorized into global and local models [13]. Global models are trained on extensive, diverse datasets (like Reaxys or the Open Reaction Database) covering many reaction types. They are useful for general condition recommendation in computer-aided synthesis planning. Local models are specialized for a specific reaction family (like Buchwald-Hartwig coupling) and are typically trained on high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data to fine-tune parameters like catalysts, solvents, and concentrations for optimal yield and selectivity [13].

2. My model's yield predictions are inaccurate, especially for new reaction types. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. The accuracy of yield prediction is fundamentally bounded by the limitations of current chemical descriptors [14]. With diverse chemistries, even advanced models may struggle to exceed ~65% accuracy for binary (high/low) yield classification [14]. Potential solutions include:

- Using Learned Representations: Shift from hand-crafted fingerprints to deep learning models (like Graph Neural Networks or Transformers) that learn relevant features directly from molecular structures (SMILES or graphs), which can improve performance [15] [16].

- Incorporating Uncertainty: Employ models like Deep Kernel Learning (DKL), which combine the representation learning of neural networks with the uncertainty quantification of Gaussian processes. This helps identify when the model is making low-confidence predictions on unfamiliar data [15].

- Ensuring Data Quality: Verify your dataset includes failed experiments (zero yields) to avoid models that are biased towards successful reactions [13].

3. How can I reliably optimize a reaction using machine learning? For optimization, Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy, especially when combined with a surrogate model that provides uncertainty estimates [15] [13]. The workflow is:

- Initial Data: Collect a small initial dataset of experiments.

- Model Training: Train a model like a DKL-based surrogate on this data [15].

- Suggestion: Use BO to suggest the next experiment by balancing exploration (trying conditions with high uncertainty) and exploitation (trying conditions predicted to give high yield).

- Iteration: Run the suggested experiment, add the result to the dataset, and retrain the model iteratively until the optimal conditions are found. This method is more efficient than traditional "one factor at a time" approaches [13].

4. How do I represent a chemical reaction for a machine learning model? The choice of representation depends on the data and task.

- Non-learned Representations: These are fixed, hand-crafted features.

- Molecular Descriptors: Electronic and spatial properties from calculations like DFT, concatenated for all reactants [15].

- Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints): Sparse bit vectors representing molecular structure [15] [14].

- Reaction Fingerprints (e.g., DRFP): Binary fingerprints generated from reaction SMILES to encode the structural change [15].

- Learned Representations: The model learns optimal features from raw data.

- SMILES Strings: Treated as text and processed with language models [16].

- Molecular Graphs: Represent atoms and bonds as nodes and edges, processed with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). Advanced methods like RAlign explicitly model atomic correspondence between reactants and products to better capture the reaction transformation [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization to New Data

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Data Mismatch and Selection Bias.

- Solution: Ensure your training data is representative. Public databases often only report successful conditions, creating bias [13]. Where possible, incorporate internal data that includes "failed" experiments. Using a more diverse dataset, such as the emerging Open Reaction Database (ORD), can also help [13].

- Cause 2: Inadequate Molecular Representation.

- Solution: Transition from traditional fingerprints to a learned representation. Implement a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn features directly from molecular graphs, which can capture more nuanced chemical information [15] [16]. For reaction-specific tasks, consider architectures like RAlign that model the reaction center [16].

Problem: High Uncertainty in Predictions

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inherent Limitations of the Model.

- Solution: Adopt a model designed for uncertainty quantification. Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) is ideal for this, as it provides reliable uncertainty estimates for its predictions, which is crucial for Bayesian Optimization [15].

- Cause 2: Sparse or High-Dimensional Input Data.

- Solution: When using high-dimensional fingerprints, a DKL model can use a neural network to learn a lower-dimensional, more meaningful embedding before the Gaussian process makes its prediction, improving reliability [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Deep Kernel Learning Model for Yield Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps to build a DKL model for predicting reaction yield, as described in the literature [15].

1. Data Preparation

- Input Representation: Choose an input representation. For a DKL model, this can be either:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the data into training (70%), validation (10%), and test (20%) sets. Standardize the yield values based on the training set mean and variance [15].

2. Model Architecture Setup

- Feature Learning Backbone:

- For non-learned inputs, use a Feed-Forward Neural Network (FFNN) with two fully-connected layers [15].

- For molecular graph inputs, use a Message-Passing Neural Network (MPNN). Use a Set2Set model for the graph-level readout to create an invariant representation, then sum the graph vectors of individual reactants to form the final reaction representation [15].

- Gaussian Process Layer: The output from the neural network backbone serves as the input for the base kernel of the GP layer, which produces the final prediction and its uncertainty [15].

3. Model Training

- Objective Function: Train the entire model end-to-end by jointly optimizing all neural network parameters and GP hyperparameters. This is done by maximizing the log marginal likelihood of the Gaussian Process [15].

- Validation: Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning.

4. Prediction

- At test time, compute the posterior predictive distribution of the GP. The mean of this distribution is the predicted yield, and the variance represents the uncertainty of the prediction [15].

The workflow for this protocol, integrating both data paths, is as follows:

Protocol 2: Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Condition Optimization

This protocol uses a DKL model as a surrogate for Bayesian Optimization to find optimal reaction conditions [15] [13].

1. Initial Experimental Design

- Perform a small set of initial experiments (e.g., 10-20) selected via a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) to cover the condition space broadly.

2. Surrogate Model Training

- Train a DKL model on the available experimental data (initial set plus all subsequent experiments). The DKL model will learn to predict reaction outcome (e.g., yield) based on the input conditions.

3. Acquisition Function Maximization

- Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which leverages the mean and variance predictions from the DKL model, to propose the next experiment. This function balances exploration and exploitation.

4. Iteration

- Run the experiment proposed in Step 3.

- Add the new input-yield data point to the training set.

- Retrain/update the DKL model with the expanded dataset.

- Repeat steps 2-4 until a satisfactory yield is achieved or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance of Machine Learning Models on Reaction Prediction Tasks

| Model / Approach | Input Representation | Key Strength | Reported Performance / Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest [14] | RDKit Descriptors, Fingerprints | Good performance with non-learned features | ~65% accuracy for binary yield classification on diverse datasets [14]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [15] [16] | Molecular Graphs | Learns features directly from structure | Comparable performance to other deep learning models; can lack uncertainty quantification [15]. |

| Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) [15] | Descriptors, Fingerprints, or Graphs | Combines NN feature learning with GP uncertainty | Significantly outperforms standard GPs; provides comparable performance to GNNs with uncertainty estimation [15]. |

| RAlign Model [16] | Molecular Graphs with reactant-product alignment | Explicitly models reaction centers and atomic correspondence | Achieved 25% increase in top-1 accuracy for condition prediction on USPTO dataset vs. strong baselines [16]. |

Table 2: Common Chemical Reaction Databases for Training ML Models

| Database | Size (Approx.) | Key Characteristics | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaxys [13] | ~65 million reactions | Extensive proprietary database | Proprietary |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [13] | ~1.7 million+ | Open-source initiative to standardize chemical synthesis data | Open Access |

| SciFindern [13] | ~150 million reactions | Large proprietary database | Proprietary |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Datasets (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig) [13] | < 10,000 reactions | Focused on specific reaction families; includes failed experiments | Often available in papers or ORD |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Machine Learning-Driven Reaction Optimization Workflow

| Item | Function in the Experiment / Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotics | Enables the rapid and automated collection of large, consistent datasets on reaction outcomes under varying conditions, which is crucial for training local models [13]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) Software | An optimization strategy that uses a surrogate model to intelligently propose the next experiment, efficiently navigating a complex condition space to find the optimum [13]. |

| Surrogate Model (e.g., DKL) | A machine learning model that approximates the reaction landscape; it is fast to evaluate and provides uncertainty, making it the core of the BO loop [15]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Framework | Software libraries (e.g., PyTor Geometric, DGL-LifeSci) that allow for the construction of models that learn directly from molecular graph structures [15] [16]. |

| Differentiable Reaction Fingerprint (DRFP) | A hand-crafted reaction representation that can be used as input to models when learned representations are not feasible, often yielding strong performance [15]. |

| cis-4-Nonenal | cis-4-Nonenal|Volatile Reference Standard|RUO |

| cyclo(L-Phe-L-Val) | cyclo(L-Phe-L-Val), CAS:35590-86-4, MF:C14H18N2O2, MW:246.308 |

The accumulation of large-scale experimental data in research laboratories presents a significant opportunity for a paradigm shift in chemical discovery. Traditional approaches require conducting new experiments to test each hypothesis, consuming substantial time, resources, and chemicals. However, a new strategy is emerging: leveraging existing, previously acquired high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data to test new chemical hypotheses without performing additional experiments [6]. This approach is particularly powerful when combined with machine learning (ML) to navigate tera-scale datasets, enabling the discovery of novel organic reactions and optimization of yields from archived experimental results [6]. This technical support center provides guidance for researchers aiming to implement this innovative methodology within their machine learning-driven organic chemistry research.

Technical Foundations: MS Data and ML Integration

Mass Spectrometry Data Fundamentals

Mass spectrometry generates information on the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions, with the fundamental equation expressed as:

[ \frac{m}{z} = \frac{m}{ze} ]

where (m) is the ion mass, (z) is the charge number, and (e) is the elementary charge [17]. The resolution of a mass spectrometer, which defines its ability to distinguish between ions with similar m/z ratios, is given by:

[ R = \frac{m}{\Delta m} ]

where (\Delta m) is the mass difference between two distinguishable ions [17].

Mass spectrometry data can be acquired in different modes. In profile mode (continuum mode), the instrument records a continuous signal, while centroided data results from processing that integrates Gaussian regions of the continuum spectrum into single m/z-intensity pairs, significantly reducing file size [18]. For chromatographically separated samples, data becomes three-dimensional, incorporating retention time, m/z, and intensity [18].

Machine Learning Powered Search Engine

The MEDUSA Search engine represents a cutting-edge approach to navigating tera-scale MS datasets [6]. Its machine learning-powered pipeline employs a novel isotope-distribution-centric search algorithm augmented by two synergistic ML models, all trained on synthetic MS data to overcome the challenge of limited annotated spectra [6].

Table: Key Components of the ML-Powered Search Engine

| Component | Function | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-distribution-centric algorithm | Searches for isotopic patterns in HRMS data | Reduces false positive detections |

| ML regression model | Estimates ion presence threshold based on query formula | Enables automated decision making |

| ML classification model | Filters false positive matches | Improves detection accuracy |

| Synthetic data training | Generates isotopic patterns and simulates measurement errors | Eliminates need for extensive manual annotation |

The search process operates through a multi-level architecture inspired by web search engines to achieve practical search speeds across tera-scale databases (e.g., >8 TB of 22,000 spectra) [6]. This system can confirm the presence of hypothesized ions across diverse chemical applications, supporting "experimentation in the past" by revealing transformations overlooked in initial manual analyses [6].

ML-Powered Workflow for Reaction Discovery

Troubleshooting Guides

Data Quality and Preprocessing Issues

Q: Why is my MS data preprocessing yielding inconsistent features across samples?

A: Inconsistent feature detection typically stems from improper peak alignment or parameter settings during data reduction from raw spectra to feature tables.

Solution 1: Verify Centroiding Process Ensure consistent centroiding across all files. Use post-acquisition centroiding with ProteoWizard's msconvert or R package MSnbase if instrument software centroiding is inconsistent [18]. Consistent centroiding transforms continuous profile data into discrete "stick" spectra, reducing file size and standardizing downstream processing [18].

Solution 2: Optimize Peak Picking Parameters For LC-MS data, adjust the centWave algorithm parameters in XCMS, specifically the

peakwidth(min/max peak width in seconds) andmzdiff(minimum m/z difference for overlapping peaks) based on your chromatographic system's performance [18]. For direct infusion MS, use MassSpecWavelet's continuous wavelet transform-based peak detection viafindPeaks.MSWin XCMS [18].Solution 3: Implement Robust Alignment Use XCMS grouping functions with density-based alignment to correct retention time drift across samples. Adjust bandwidth (bw) and minFraction parameters to balance alignment stringency and feature detection sensitivity [18].

Q: How can I improve isotopic distribution matching in my search algorithm?

A: Effective isotopic distribution matching is crucial for accurate molecular formula assignment and reaction discovery.

Solution 1: Enhance Theoretical Pattern Accuracy Incorporate instrument-specific resolution parameters when generating theoretical isotopic distributions. Account for the relationship between isotopic distribution information and false positive rates, as incomplete distribution matching significantly increases erroneous detections [6].

Solution 2: Optimize Similarity Metrics Implement cosine distance as your similarity metric between theoretical and experimental isotopic distributions, as used in the MEDUSA Search engine [6]. Establish formula-dependent thresholds rather than universal cutoffs, as optimal thresholds vary with molecular composition [6].

Solution 3: Augment with ML Classification Train a machine learning classification model on synthetic data to distinguish true isotopic patterns from false positives, focusing on patterns that narrowly miss similarity thresholds but exhibit physiochemical plausibility [6].

Machine Learning and Data Analysis Challenges

Q: Why does my ML model fail to generalize well to new MS datasets?

A: Poor generalization typically results from training data limitations or feature representation issues.

Solution 1: Utilize Synthetic Data Augmentation Generate synthetic MS data with constructed isotopic distribution patterns from molecular formulas, then apply data augmentation to simulate instrument measurement errors [6]. This approach addresses the annotated training data bottleneck without requiring extensive manual labeling [6].

Solution 2: Implement Adaptive Feature Engineering Instead of fixed m/z tolerance, use adaptive mass error correction based on observed calibration data. Incorporate additional dimensions like retention time predictability or collision cross-section (for IMS data) to improve feature representation [18].

Solution 3: Apply Transfer Learning Pre-train models on large synthetic datasets, then fine-tune with limited experimental data from your specific instrument and application domain. This approach is particularly effective for neural network architectures [6].

Q: How can I validate reaction discoveries from archived data without new experiments?

A: Implement a multi-modal validation strategy that maximizes information from existing data.

Solution 1: Orthogonal Data Correlation Search for complementary evidence in other analytical data (NMR, IR) that may have been collected simultaneously with your MS data. Even limited orthogonal data can provide crucial structural verification [6].

Solution 2: Tandem MS Validation Extract and examine MS/MS fragmentation patterns from data-dependent acquisition scans in your archived data. Characteristic fragmentation pathways provide structural evidence supporting novel reaction discoveries [6].

Solution 3: Hypothesis-Driven Searching Instead of purely exploratory analysis, generate specific reaction hypotheses based on chemical principles (e.g., BRICS fragmentation or multimodal LLMs) [6], then test these hypotheses systematically in your archived data. This approach increases the likelihood of chemically plausible discoveries.

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

Q: How can I design experiments today to maximize future data mining potential?

A: Strategic experimental design ensures that current data remains valuable for future mining efforts.

Solution 1: Standardize Metadata Collection Implement consistent sample annotation using standardized metadata templates. Structure data using Bioconductor's SummarizedExperiment or similar frameworks that align quantitative data with feature and sample annotations [18].

Solution 2: Maximize Data Comprehensiveness Even when focusing on specific target compounds, employ full-scan HRMS methods rather than targeted approaches alone. This captures byproducts and unexpected species that may become relevant in future mining efforts [6].

Solution 3: Implement FAIR Data Principles Ensure all datasets adhere to Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) principles [6]. Maintain detailed records of experimental conditions, as these contextual details are essential for meaningful retrospective analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the most critical parameters for successful mining of existing MS data? A: The most critical parameters are mass accuracy (<5 ppm for HRMS), consistent chromatographic alignment (<0.2 min RT shift), comprehensive metadata annotation, and standardized data formats that enable cross-study analysis [18].

Q: How much historical data is needed to make reaction discovery feasible? A: While benefits accrue with any dataset, meaningful discovery typically requires tera-scale databases (e.g., >8 TB across thousands of spectra) representing diverse chemical transformations. The MEDUSA approach has demonstrated success with 22,000 spectra datasets [6].

Q: Can I apply these methods to low-resolution mass spectrometry data? A: While possible, low-resolution data significantly limits discovery potential due to reduced molecular formula specificity. High-resolution instruments (≥50,000 resolution) are strongly recommended for untargeted mining applications [6].

Q: What computational resources are required for tera-scale MS data mining? A: Efficient mining requires multi-level search architectures with optimized algorithms. The MEDUSA Search engine can process tera-scale databases in "acceptable time" on appropriate hardware, though specific requirements depend on implementation [6].

Q: How do we avoid false discoveries when mining existing data? A: Implement stringent statistical validation with false discovery rate correction, orthogonal verification where possible, chemical plausibility assessments, and ML-based false positive filtering [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Resources for ML-Driven MS Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein/peptide degradation during sample prep | Use EDTA-free formulations; PMSF recommended [19] |

| HPLC Grade Solvents | Minimize background contamination and ion suppression | Use filter tips and dedicated glassware to avoid contaminants [19] |

| Trypsin/Lys-C Enzymes | Protein digestion for proteomic studies | Adjust digestion time or use double digestion for optimal peptide sizes [19] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Create training data for ML models | Generate isotopic patterns and simulate instrument error [6] |

| FAIR-Compliant Databases | Store and share experimental data | Enable data findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reuse [6] |

Workflow Visualization: Data Mining Pipeline

MS Data Mining Pipeline

The strategic mining of existing mass spectrometry data represents a powerful approach to accelerating chemical discovery while reducing experimental costs and environmental impact. By implementing robust troubleshooting protocols, standardized experimental designs, and machine-learning-enhanced search strategies, researchers can unlock the hidden potential in their archived data. This methodology supports the discovery of novel reactions, such as the heterocycle-vinyl coupling process in Mizoroki-Heck reactions [6], while aligning with green chemistry principles by minimizing new resource consumption. As mass spectrometry capabilities continue to advance and datasets grow exponentially, these data mining approaches will become increasingly essential tools for innovative research in organic chemistry and drug development.

ML in Action: Integrating High-Throughput Tools and Algorithms for Reaction Optimization

FAQs: Optimizing Automated Workflows for Yield Prediction

FAQ 1: What are the most suitable AI robotics platforms for automating high-throughput experimentation in organic synthesis?

The choice of platform depends on your specific needs, such as the scale of operations, budget, and required level of AI integration. The table below summarizes key platforms suitable for research and development.

| Platform/Tool | Best For | Key AI/ML Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Isaac Sim [20] | Simulation & AI training | Photorealistic, physics-based simulation for training computer vision models; GPU acceleration. | Requires high-end GPU infrastructure; has a steeper learning curve. |

| ROS 2 (Robot Operating System 2) [20] | Research & development | Open-source flexibility with a large library of packages; cross-platform support. | Limited built-in AI, requiring third-party integration; can be complex for large-scale deployments. |

| Google Robotics AI Platform [20] | AI-heavy robotics | Deep learning integration with TensorFlow; reinforcement learning environments; cloud AutoML. | Heavily cloud-dependent; still evolving for industrial applications. |

| OpenAI Robotics API [20] | Research & prototyping | Integration with large language models (e.g., GPT) for natural language control; reinforcement learning. | Considered experimental for large-scale use; requires significant ML expertise. |

| AWS RoboMaker [20] | Cloud robotics | Large-scale robot fleet simulation; integration with the broader AWS cloud ecosystem. | Ongoing operational costs; tied to the AWS cloud environment. |

FAQ 2: Our ML model for reaction yield prediction is performing poorly on new, diverse reaction types. How can we improve its generalizability?

Poor generalization often occurs when a model has been trained on a narrow dataset (e.g., a single reaction class) and cannot handle the complexity of diverse chemistries. The log-RRIM (Yield Prediction via Local-to-global Reaction Representation Learning and Interaction Modeling) framework was specifically designed to address this challenge [21].

- Root Cause: Models that treat an entire reaction as a single SMILES string (sequence-based models) often struggle to distinguish the distinct roles of reactants and reagents and can overlook the impact of small but critical molecular fragments [21].

- Recommended Solution: Implement a local-to-global learning process.

- Local Representation: Learn molecule-level representations for each reaction component (reactants, reagents, products) individually. This ensures small fragments are given appropriate attention.

- Interaction Modeling: Explicitly model the interactions between these components. The

log-RRIMframework, for instance, uses a cross-attention mechanism between reagents and reaction center atoms to simulate how reagents influence bond-breaking and formation, which directly affects yield [21]. - Global Aggregation: Aggregate this information for the final yield prediction. This structured approach more accurately reflects chemical reality and has demonstrated superior performance on datasets with diverse reaction types [21].

FAQ 3: Our automated experiments are failing without clear error messages. What is a systematic way to diagnose these issues?

Troubleshooting automated ML and robotics experiments requires a structured approach to isolate the problem.

- Check the Job Status: Begin by checking the failure message in your platform's job overview or status section [22].

- Drill into the Logs: For more detailed information, navigate to the logs of the failed job. The

std_log.txtfile is a standard location for detailed error logs and exception traces [22]. - Inspect Pipeline Workflows: If your automation uses a pipeline, identify the specific failed node (often marked in red) and check its individual logs and status messages [22].

- Validate the Simulation: If you are using a simulation platform like NVIDIA Isaac Sim, ensure that the photorealistic physics and parameters accurately reflect your real-world lab setup. Discrepancies here can lead to failures when moving to physical robots [20].

FAQ 4: How can we effectively predict reaction yields before running physical experiments?

Accurate yield prediction saves significant time and resources. The field has evolved through several methodological approaches:

- Traditional Machine Learning: Early methods used Random Forest or SVM models on handcrafted chemical descriptors (e.g., DFT calculations, fingerprints). These often produced unsatisfactory results, as the descriptors and models were insufficient to capture the complexity of reactions [21].

- Sequence-Based Models (e.g., YieldBERT, T5Chem): These models use SMILES strings and transformer architectures. While an improvement, they can overlook the roles of small fragments and reactant-reagent interactions by treating the entire reaction as a single sequence [21].

- Graph-Based Models (e.g., log-RRIM): The current state-of-the-art uses Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to represent molecules as graphs, naturally capturing structural information. The most advanced models, like

log-RRIM, add a local-to-global learning process and explicit interaction modeling (e.g., cross-attention) between reactants and reagents, leading to significantly higher prediction accuracy, especially for medium-to-high-yielding reactions [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Yield Prediction Accuracy on Diverse Reaction Datasets

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Resolution | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| High error when predicting yields for reaction types not in the training data. | Model lacks capacity to understand molecular interactions and roles; trained on a too-narrow dataset. | Adopt a graph-based model with local-to-global representation learning and explicit interaction modeling, such as the log-RRIM framework [21]. |

Evaluate the model on a held-out test set containing diverse reaction types from sources like the USPTO database. Compare Mean Absolute Error (MAE) before and after implementation. |

| Model performance is good on a single reaction class but fails on others. | Sequence-based model is overlooking critical small fragments and reagent effects. | Re-train the model using a architecture that processes reactants and reagents separately before modeling their interaction. | Analyze the model's attention mechanisms to confirm it is focusing on the correct, chemically relevant parts of the reaction [21]. |

Issue 2: Failed Orchestration Between ML Inference and Robotic Execution

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Resolution | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| A robotic arm fails to execute a synthesis step despite the ML model suggesting high yield. | Data format mismatch between the ML model's output and the robot's control API; incorrect calibration. | Implement a robust "translation layer" or adapter that seamlessly converts ML output (e.g., a list of actions) into commands compatible with the robotics platform (e.g., ROS 2 messages) [20]. | Perform a dry-run of the automated workflow using simulated outputs. Use orchestration tools (e.g., AWS RoboMaker, Azure ML pipelines) to monitor the hand-off between the ML and robotics modules [20] [22]. |

| The physical reaction yield is consistently lower than the model's prediction. | Simulation-to-reality gap; the simulation environment does not perfectly model real-world physics and chemistry. | Fine-tune the physics parameters in your simulation platform (e.g., NVIDIA Isaac Sim) and use digital twin technology where possible to better mirror the physical lab environment [20]. | Run a calibration set of well-understood reactions to quantify the sim-to-real gap and iteratively adjust the simulation parameters. |

Experimental Protocols for Yield Prediction Model Validation

Protocol 1: Validating a Novel Yield Prediction Model Using a Diverse Dataset

This protocol outlines the steps to benchmark a new ML model for reaction yield prediction against established baselines.

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Obtain a standardized, publicly available dataset known for diverse reaction types, such as the US Patent (USPTO) database [21].

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring that reactions in the test set are not present in the training set (scaffold split).

Model Training and Fine-Tuning:

- Implement the candidate model (e.g., the

log-RRIMarchitecture) and established baseline models (e.g.,YieldBERT,T5Chem). - Train each model on the training set. For transformer-based models, this typically involves fine-tuning a pre-trained base model on the specific yield prediction task [21].

- Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning and to select the best-performing model checkpoint.

- Implement the candidate model (e.g., the

Performance Evaluation:

- Use the held-out test set to generate final performance metrics.

- Primary Metric: Calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between the predicted and experimental yields.

- Secondary Analysis: Perform a segment analysis to evaluate if the model performs consistently across different yield ranges (e.g., low, medium, high yield) and reaction classes [21].

Interaction Analysis:

- To validate that the model is learning chemically meaningful interactions, analyze the attention weights in the model's cross-attention layers. The model should assign higher attention to atoms in the reaction center that are interacting with specific reagents [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and hardware tools essential for building automated workflows for organic reaction optimization.

| Item / Tool | Function / Application | Relevance to Automated Workflows |

|---|---|---|

log-RRIM Model [21] |

A graph transformer-based model for accurate reaction yield prediction. | The core AI component that predicts the outcome of a proposed reaction, guiding the automated platform on which experiments to run. |

| NVIDIA Isaac Sim [20] | A photorealistic, physics-based simulation platform. | Allows for training and testing robotic procedures and computer vision models in a safe, virtual environment before real-world deployment. |

| ROS 2 (Robot Operating System 2) [20] | Open-source robotics middleware. | Provides the communication backbone for integrating various hardware components (robotic arms, sensors) with the central ML model. |

| Chemical Reaction Optimization Wand (CROW) [23] | A predictive tool for translating reaction conditions to higher temperatures. | Can be integrated into the ML workflow to propose alternative, more efficient reaction conditions (time/temperature) to the robotic system. |

| BERT-based Classifiers (e.g., PubMedBERT) [24] | Deep learning models for identifying high-quality clinical literature. | Can be adapted to automatically curate and extract relevant chemical reaction data from vast scientific literature to expand training datasets. |

| BODIPY FL prazosin | BODIPY FL prazosin, CAS:175799-93-6, MF:C28H32BF2N7O3, MW:563.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Uncaric acid | Uncaric acid, CAS:123135-05-7, MF:C30H48O5, MW:488.69912 | Chemical Reagent |

Automated Yield Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of an automated platform for optimizing organic reaction yields, from hypothesis to validation.

Troubleshooting Automated Experimentation

This diagram outlines a systematic procedure for diagnosing failures in an automated experimentation loop.

Troubleshooting Guides

Closed-Loop Optimization Workflow Failure

Problem: The automated, closed-loop reaction optimization platform fails to converge on optimal conditions or stops proposing new experiments.

Solution:

- Verify Data Fidelity: Ensure that the high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platform's analytical tools are correctly calibrated and that the data processing algorithms are accurately mapping collected data points to the target objectives, such as yield or selectivity [25].

- Inspect the ML Algorithm: Check the configuration of the machine learning (ML) optimization algorithm. For Bayesian optimization, ensure that the acquisition function is correctly balanced between exploration and exploitation. Frameworks like BoFire are specifically designed for such real-world chemistry applications [26].

- Review Experimental Boundaries: Confirm that the defined search space (e.g., ranges for continuous factors like temperature and time, and constraints for mixture factors) accurately reflects physical and chemical realities. Incorrect constraints can prevent the algorithm from finding viable solutions [27] [26].

Mixture Design Configuration Error

Problem: Errors occur when setting up a mixture design with multiple components, such as the component proportions not summing correctly to the specified total [27].

Solution:

- Use Dedicated Software Features: Utilize the mixture design feature in DoE software (e.g., JMP). Set the total mixture sum and use linear constraints to enforce that the sum of individual components equals this total [27].

- Leverage Advanced Frameworks: For complex formulations with constraints (e.g., a paint mixture limited to 5 out of 20 possible compounds), use a framework like BoFire that supports

NChooseKconstraints and inter-point equality constraints for batch processing [26].

Poor Model Performance and Prediction Accuracy

Problem: The ML model guiding the optimization makes poor predictions, leading to inefficient experiment selection.

Solution:

- Augment Training Data: If labeled experimental data is scarce, use synthetic data for initial model training. This approach has been successfully used to train models for tasks like isotopic distribution recognition in mass spectrometry data [6].

- Re-evaluate Feature Space: Ensure that the model's input features (e.g., chemical descriptors, reaction conditions) are relevant and correctly encoded. For molecular factors, use appropriate representations like SMILES strings [26].

- Switch from Global to Local Models: A global model trained on a broad reaction database can suggest general conditions. For fine-tuning a specific reaction, develop a local model that iteratively learns from the data generated during the optimization campaign itself [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core advantage of combining DoE with ML for reaction optimization? A1: The integration allows for the synchronous optimization of multiple reaction variables within a high-dimensional parameter space. ML models predict reaction outcomes and guide the selection of subsequent experiments, which are executed by automated platforms. This closed-loop approach finds global optimal conditions much faster than traditional one-variable-at-a-time or pure trial-and-error methods, significantly reducing experimentation time and resource consumption [25] [28] [26].

Q2: How do I transition from an initial space-filling design to a targeted ML-driven optimization? A2: A stepwise strategy is recommended. First, use a classical DoE method like a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to gather initial data across the entire experimental domain. This provides a broad overview of the reaction landscape. Then, seamlessly transition to a predictive strategy (e.g., Bayesian Optimization) which uses a surrogate model to suggest experiments that are most likely to improve the objectives, such as maximizing yield or hitting a target purity [26].

Q3: Our optimization has multiple, sometimes conflicting, objectives (e.g., maximize yield and minimize cost). How can ML handle this?

A3: Multi-objective optimization algorithms are designed for this purpose. In frameworks like BoFire, you can define multiple objectives (e.g., MaximizeObjective, CloseToTargetObjective). The optimizer can then use a posteriori approaches, such as qParEGO, to approximate the Pareto front. This front represents all optimal compromises between your objectives, allowing you to choose the best balance for your needs [26].

Q4: We have terabytes of historical HRMS data. Can this be used for reaction discovery without new experiments? A4: Yes. Advanced ML-powered search engines, like MEDUSA Search, can decipher tera-scale high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data. By generating reaction hypotheses and searching for corresponding ions in archived data, these tools can discover previously unknown reaction pathways and transformations, making data reuse a powerful and sustainable strategy for discovery [6].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard closed-loop workflow for organic reaction optimization integrating DoE and ML, as described in the search results [25] [28].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential tools and platforms for implementing a DoE and ML-driven optimization strategy.

| Category | Item/Platform | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Synthesis Platforms | Chemspeed SWING [25], Custom Mobile Robots [25] | Enables high-throughput, parallel reaction execution under varied conditions with minimal human intervention. |

| DoE & BO Software | BoFire [26], JMP [27] | Defines experimental domains, generates initial designs (e.g., space-filling), and performs Bayesian Optimization. |

| Data Analysis Engines | MEDUSA Search [6] | ML-powered analysis of large-scale analytical data (e.g., HRMS) for reaction discovery and hypothesis testing. |

| Reaction Vessels | Microtiter Well Plates (96/48/24-well) [25], 3D-Printed Reactors [25] | Provides parallel reaction vessels for batch screening; custom reactors enable specialized conditions. |

| Analytical Integration | In-line/Online NMR [29], HRMS [6] | Provides real-time or rapid offline data on reaction outcome for feedback to the ML model. |

This technical support document outlines how the systematic application of Design of Experiment (DoE) methodologies and Machine Learning (ML) can overcome common yield limitations in catalytic hydrogenation, a critical reaction in organic synthesis for pharmaceutical development. Achieving high yield and purity is often hampered by complex, interdependent variables. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches are inefficient for navigating this complexity and can miss critical optimal conditions. This guide details a real-world case where these tools were leveraged to increase the yield of a prostaglandin intermediate from 60% to 98.8%, providing a framework for researchers to address similar challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use DoE instead of my traditional OFAT approach for hydrogenation optimization?

A traditional OFAT approach, where only one variable is changed while others are held constant, is inefficient and often fails to identify optimal conditions because it cannot account for interaction effects between variables. For example, the optimal temperature for a reaction may depend on the catalyst loading. DoE is a structured methodology that allows for the simultaneous variation of all relevant factors. This enables the creation of a mathematical model that can:

- Identify critical factors and their interactions affecting yield and selectivity.

- Optimize multiple responses (e.g., yield, purity, minimal byproducts) simultaneously.

- Significantly reduce the total number of experiments required, saving time and resources.

Q2: My hydrogenation reaction produces a high yield but also a stubborn Ullmann-type dimer side product. How can I tackle this specific issue?

The formation of Ullmann-type side products, as encountered in the prostaglandin intermediate case, is a classic surface-mediated reaction on the catalyst [30]. DoE is particularly powerful for solving this. Your experimental design should include factors known to influence surface-mediated reactions. The analysis will reveal which parameters (e.g., water content in the solvent, catalyst activation status, stirring rate) most significantly impact the dimerization side reaction versus the desired hydrogenation pathway. The model can then guide you to a operational window that maximizes main product yield while suppressing the dimer formation.

Q3: I have a large amount of historical catalytic hydrogenation data. How can Machine Learning help me?

Machine Learning can transform your historical data into a predictive model for catalyst performance. ML algorithms can identify complex, non-linear relationships between catalyst properties, reaction conditions, and outcomes that are difficult for humans to discern. For instance, ML models like Gradient Boosted Regression Trees (GBRT) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have been used successfully to predict key performance indicators like CO2 conversion and methanol selectivity in hydrogenation reactions with high accuracy (R² > 0.94) [31]. This allows for in-silico screening of catalysts and conditions, drastically accelerating the discovery and optimization process.

Q4: What kind of data do I need to start applying ML to my hydrogenation research?

To build a robust ML model, you need a dataset where each experiment (or data point) is characterized by:

- Input Features (Descriptors): These describe the reaction setup. Examples include catalyst composition (metal, support, particle size), catalyst calcination temperature [31], reaction temperature, pressure, concentration, and properties of the substrate.

- Output (Target Variable): This is the result you want to predict, such as reaction yield, conversion, selectivity for a particular product, or impurity level.

Q5: Can DoE and ML be used together?

Absolutely. They are complementary tools. A well-executed DoE study generates high-quality, structured data that is ideal for training an ML model. The initial DoE model can be a linear or quadratic polynomial, while the ML model can capture more complex relationships from the same data. Furthermore, an ML model trained on broad historical data can be used to suggest promising regions for a subsequent, more focused DoE study.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Hydrogenation Issues

Problem 1: Low Yield and High Byproduct Formation

- Symptoms: The desired product yield is low. Chromatography shows multiple, hard-to-separate side products.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Sub-optimal core reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst loading).

- Solution: Employ a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) DoE to map the relationship between these factors and your responses (yield, byproduct level). This will help you find the true optimum.

- Cause: Catalyst is promoting undesired parallel pathways (e.g., dimerization).

- Solution: As in the featured case study, use a DoE to understand the factors driving the side reaction. The solution may involve adjusting the solvent system (e.g., water content) or using a differently pretreated catalyst [30].

Problem 2: Poor Catalyst Selectivity

- Symptoms: Hydrogenation of a specific functional group (e.g., alkene) does not proceed with high chemoselectivity, reducing other sensitive groups.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Catalyst type and form are not suitable for the required selectivity.

- Solution: Consider using selective catalysts like Lindlar's catalyst for the partial hydrogenation of alkynes to cis-alkenes [32]. Use ML models to screen binary alloys or metal combinations for their predicted adsorption energies and selectivity [33].

- Cause: Reaction is proceeding too quickly/harshly.

- Solution: Use DoE to find gentler conditions (lower temperature, pressure) that favor the desired selective pathway. Explore transfer hydrogenation with donors like isopropanol or formic acid, which can offer superior selectivity for certain substrates like carbonyls [34].

Problem 3: Slow or Stalled Reaction

- Symptoms: Low conversion even after extended reaction times.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Catalyst is deactivated (poisoned or sintered).

- Solution: Use a DoE to study catalyst pretreatment and activation procedures. Investigate factors like calcination temperature, which ML models have shown to be highly significant for catalyst activity [31].

- Cause: Mass transfer limitations (common in heterogeneous catalysis).

- Solution: A DoE can include factors like stirring speed to diagnose mass transfer issues. If the model shows stirring speed is a significant factor, the reaction is likely mass-transfer limited, and you should focus on improving agitation or reactor design.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Case Study: DoE Protocol for Prostaglandin Intermediate Hydrogenation

This protocol is adapted from the successful optimization of a lactone hydrogenation, where Ullmann dimerization was a key side reaction [30].

1. Objective: Maximize yield of intermediate 2 while minimizing the formation of Ullmann dimer side product.

2. Catalyst & Reaction:

- Substrate: Lactone (3).

- Catalyst: A heterogeneous palladium-based catalyst.

- Reaction: Catalytic hydrogenation.

3. DoE Workflow:

- Step 1: Screening Design. A fractional factorial design was used to screen multiple potential factors efficiently.

- Step 2: Optimization Design. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was used to model the response surface and locate the optimum.

- Step 3: Analysis. Response data (yield, dimer %) was fitted to a second-order polynomial model. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to identify statistically significant effects.

4. Key Factors and Levels Investigated:

- Catalyst age/activation status (e.g., fresh vs. recycled, pre-treatment method)

- Water content in the solvent mixture (% v/v)

- Reaction temperature (°C)

- Hydrogen pressure (bar)

- Catalyst loading (mol%)

5. Outcome: The DoE model identified water content and catalyst status as the most significant factors controlling the side reaction. By optimizing these and other factors, the yield was increased to 98.8% with suppressed dimer formation.

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow of the integrated DoE and ML optimization process.

Table 1: Summary of ML Model Performance in Predicting Hydrogenation Catalytic Activity [31]

| Machine Learning Model | R² for CO2 Conversion | R² for Methanol Selectivity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosted Regression Trees (GBRT) | 0.95 | 0.95 | Outperformed other models; high predictive accuracy. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 0.94 | 0.95 | High accuracy; revealed catalyst composition and calcination temperature as most significant inputs. |

| Random Forest Regression | <0.90 (inferred) | <0.90 (inferred) | Good performance, but lower than top performers. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | <0.90 (inferred) | <0.90 (inferred) | Moderate performance for this dataset. |

Table 2: Key Factors and Optimization Outcomes from Case Study [30]

| Factor / Outcome | Initial/Baseline Condition | Optimized Condition | Impact on Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Content | Non-optimized | Precisely controlled optimum | Major factor in suppressing Ullmann dimer side reaction. |

| Catalyst Status | Non-optimized | Specific activation/loading | Critical for maximizing activity and minimizing side reactions. |

| Reaction Yield | ~60% | 98.8% | Primary target metric successfully achieved. |

| Side Product (Dimer) | Significant | Minimized | Purity and efficiency dramatically improved. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Catalytic Hydrogenation Research

| Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (Pd/C, Pt/C, Raney Ni, Ru/Al₂O₃) | The workhorses of hydrogenation. Choice depends on substrate and required selectivity (e.g., Pd for alkenes, Ru for aromatics). Supports like carbon or alumina influence activity [32] [30]. |

| Homogeneous Catalysts (Wilkinson's Catalyst, Crabtree's Catalyst) | Offer high selectivity and are crucial for asymmetric hydrogenation. Often used in fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis [32]. |

| Hydrogen Donors (Isopropanol, Formic Acid, Ammonia Borane) | Essential for Transfer Hydrogenation, a safer alternative to Hâ‚‚ gas. Isopropanol dehydrogenates to acetone; formic acid provides irreversible hydrogenation [34]. |

| Chiral Ligands (e.g., (S)-iPr-PHOX, Josiphos derivatives) | Used with metal catalysts to induce asymmetric hydrogenation, creating single enantiomer products vital for pharmaceutical efficacy [32]. |

| Binary Alloy Catalysts (e.g., Cu-Ni, Ru-Pt, Rh-Ni) | Can exhibit superior activity and selectivity compared to pure metals. ML models are highly effective for screening these [33]. |

| DoE Software | Platforms like JMP, Minitab, or Design-Expert are essential for designing experiments and performing statistical analysis of the results. |

| ML Libraries (Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Python libraries used to build, train, and deploy predictive models for catalyst and reaction optimization [31] [33]. |

| BPR1K871 | BPR1K871, MF:C25H28ClN7O2S, MW:526.1 g/mol |

| Avibactam sodium hydrate | Avibactam sodium hydrate, MF:C7H12N3NaO7S, MW:305.24 g/mol |

The following diagram maps the critical decision points when selecting a hydrogenation strategy, incorporating modern ML and DoE approaches.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q: My crude macrocyclization reaction mixture leads to inconsistent OLED device performance. What should I check? A: Inconsistencies often stem from uncontrolled variance in the reaction mixture. To resolve this:

- Verify Machine Learning Input Features: Ensure all reaction parameters you are optimizing (e.g., temperature, catalyst concentration, reactant stoichiometry) are being accurately recorded and fed into the ML model. Noisy input data leads to unreliable predictions [35] [25].

- Profile the Crude Mixture: Use high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to characterize the composition of your crude product batches. Inconsistent device performance can be traced to variations in the ratio of different methylated cyclo-meta-phenylene ([n]CMP) products, which the ML model may be sensitive to [35] [6].

- Audit the Automated Platform: If using a high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platform, ensure the liquid handling system is calibrated correctly. Inaccurate dispensing of reagents, especially in low volumes, will introduce significant errors [25] [1].

Q: The ML model suggests reaction conditions that seem counter-intuitive, resulting in a complex crude mixture. Should I purify the material before device fabrication? A: A core finding of this research is that purification is not always necessary and can even be detrimental. The optimal device performance, with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 9.6%, was achieved using a specific optimal crude mixture, surpassing the performance of purified materials [35] [36]. The ML model is likely identifying conditions where synergistic effects between components in the mixture enhance charge transport or emissive properties in the final device. Proceed with fabricating the device using the crude material as directed by the "from-flask-to-device" methodology.

Q: How can I improve the efficiency of the optimization campaign for a new macrocyclic host material? A:

- Implement a Structured Workflow: Adopt a closed-loop optimization workflow that integrates Design of Experiments (DoE), high-throughput experimentation, and machine learning. This systematic approach minimizes the number of experiments needed to find a global optimum [25] [1] [37].

- Leverage HTE Platforms: Utilize commercial HTE platforms (e.g., Chemspeed, Unchained Labs) or custom-built automated systems to rapidly execute the experiments suggested by the ML algorithm. This allows for the parallel synthesis and screening of hundreds of reaction conditions [25] [1].

- Define a Multi-Target Objective: Instead of optimizing for chemical yield alone, configure your ML algorithm to optimize for multiple objectives simultaneously, such as device EQE, driving voltage, and cost of materials, to find the best balanced solution [1] [37].

FAQs on Methodology and Process

Q: Why is the macrocyclization reaction for OLED materials well-suited for ML-driven optimization? A: The synthesis of methylated [n]CMPs involves a high-dimensional parameter space, including factors like reaction time, temperature, catalyst load, and reactant concentrations. The relationship between these parameters and the final device performance is complex and non-linear. Machine learning excels at navigating such complex spaces and uncovering non-intuitive relationships that would be difficult to find using traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches [25] [1] [6].

Q: What is the role of high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) in this workflow? A: HRMS plays two critical roles:

- Reaction Optimization: It provides rapid analytical data on the composition of crude reaction mixtures, which is essential for training the ML model by correlating reaction conditions with chemical output [25].

- Reaction Discovery: Advanced ML-powered search engines can decipher tera-scale archives of historical HRMS data to discover previously unknown reaction products or pathways, generating new hypotheses for optimization without new experiments [6].

Q: Can this "from-flask-to-device" approach be applied to other organic electronic materials? A: Yes, the methodology is generalizable. The principle of using ML to directly link synthetic reaction conditions to device performance metrics, thereby bypassing energy-intensive purification steps, can be applied to the development of other organic semiconductors, such as those used in transistors or solar cells. The key requirement is having a robust high-throughput device fabrication and testing pipeline [35] [36].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: ML-Optimized Macrocyclization for OLEDs

This protocol outlines the procedure for optimizing a macrocyclization reaction yielding methylated [n]cyclo-meta-phenylenes ([n]CMPs) and directly using the crude product in an Ir-doped OLED device.

1. Hypothesis and Initial Design of Experiments (DoE)

- Define the parameter space for the macrocyclization reaction. Key variables typically include: catalyst concentration, ligand ratio, reaction temperature, reaction time, and solvent composition [35] [25].

- Use a DoE methodology (e.g., factorial design) to generate an initial set of reaction conditions. This initial dataset provides the foundation for the machine learning model [25] [1].

2. High-Throughput Reaction Execution

- Utilize an automated HTE platform (e.g., a robotic system like Chemspeed SWING) to set up parallel reactions in a 96-well plate format according to the DoE matrix [25] [1].

- The platform should accurately dispense reagents, including the starting materials, catalyst, and solvents.

- Carry out reactions under the specified conditions (e.g., heating, stirring). After the set time, the reactions are quenched, and the crude mixtures are ready for analysis. No purification is performed [35].

3. Data Collection and Analysis

- Analyze each crude reaction mixture using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) to characterize the product distribution [6].

- Prepare OLED devices via spin-coating using the crude reaction mixtures as the host material, doped with an Ir-based phosphorescent emitter (e.g., Ir(ppy)₃) [35] [38].

- Test the completed devices to measure key performance metrics, primarily the External Quantum Efficiency (EQE). Record supporting data such as driving voltage and current efficiency [35] [38].

4. Machine Learning and Model Training

- Correlate the input reaction parameters with the output device performance data (EQE). This creates a predictive model [35] [25].