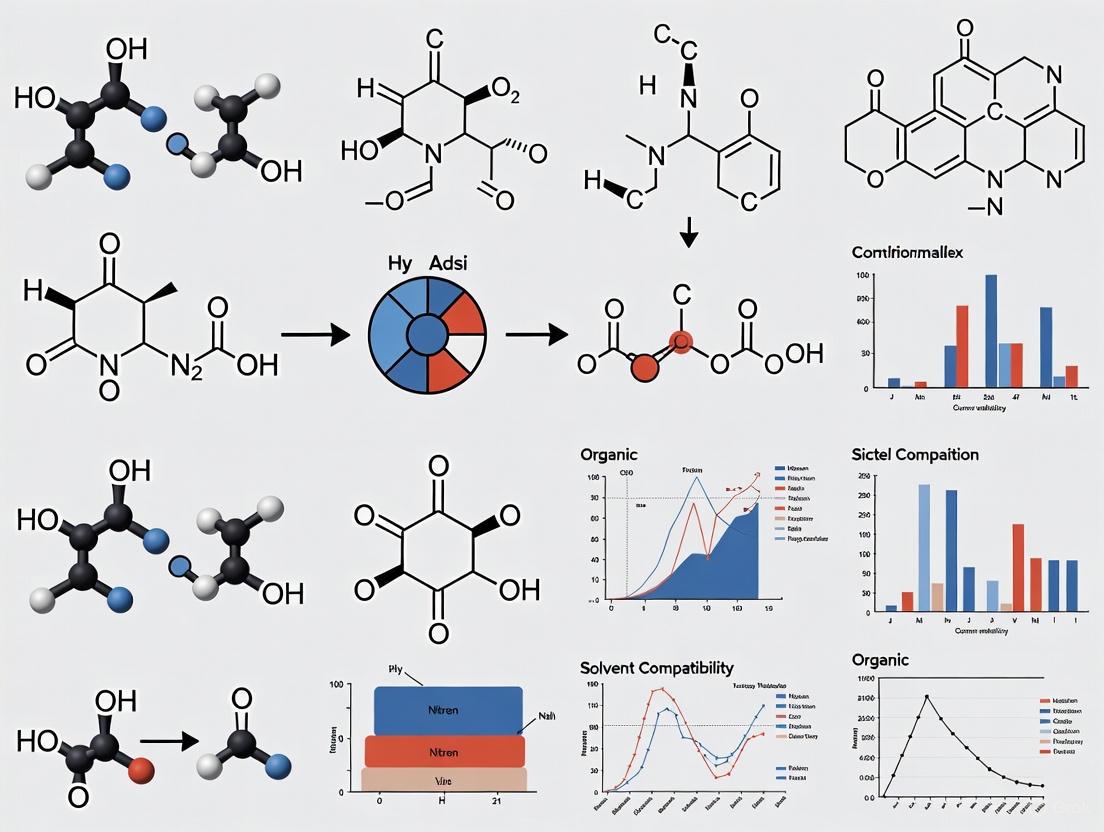

Overcoming Solvent Compatibility Challenges in Automated Liquid Handling: A Guide for Robust and Reproducible Science

Solvent compatibility remains a critical bottleneck in automated liquid handling, directly impacting data integrity, assay reproducibility, and operational efficiency in drug discovery and clinical research.

Overcoming Solvent Compatibility Challenges in Automated Liquid Handling: A Guide for Robust and Reproducible Science

Abstract

Solvent compatibility remains a critical bottleneck in automated liquid handling, directly impacting data integrity, assay reproducibility, and operational efficiency in drug discovery and clinical research. This article provides a comprehensive framework for scientists and lab professionals to overcome these challenges. It explores the foundational principles of solvent-fluid path interactions, presents methodological advances in hardware and chemistry, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and validates approaches through comparative case studies from recent literature. The goal is to equip researchers with the knowledge to build robust, resilient, and efficient automated workflows.

The Silent Saboteur: Understanding How Solvent Properties Disrupt Automated Liquid Handling

FAQs

Q1: How does liquid viscosity affect automated liquid handling performance? Viscosity, a fluid's internal resistance to flow, directly impacts liquid handling precision [1]. High-viscosity liquids (e.g., syrups) flow slower than low-viscosity liquids (e.g., water) due to stronger internal cohesive forces [2] [1]. In automated systems, this can cause slow dispensing, incomplete aspiration or delivery, and air bubbles, leading to significant volume inaccuracies [3] [4].

Q2: What are the signs of solvent volatility issues during pipetting? Volatility, a liquid's tendency to vaporize, causes issues through evaporation. Signs include a noticeable decrease in dispensed volume over time, droplet formation at the tip orifice before dispensing, and inconsistent reagent concentrations across a assay plate. These issues are exacerbated with warm reagents or low flashpoint solvents.

Q3: How can chemically aggressive solvents damage liquid handling systems? Chemically aggressive solvents can degrade critical components. They can dissolve or swell non-chemical resistant tubing and seals, cause corrosion of metal parts like pistons, and leave behind residues that clog fine nozzles and fluid paths. This damage leads to leaking, cross-contamination, and system failure [5].

Q4: Which automated liquid handling technology is best for viscous solvents? Positive displacement liquid handlers are often best for viscous solvents. They are liquid-class agnostic, meaning their performance is less affected by liquid properties, and are designed to handle a wider range of viscosities compared to air displacement systems, which can struggle with liquids over ~20 cP [3].

Q5: How do I troubleshoot inconsistent volume dispensing with my reagents? Inconsistent dispensing can be addressed systematically:

- Check Calibration: Regularly calibrate instruments using a precision balance and the specific reagent to verify volume accuracy [5] [4].

- Inspect Components: Check for and replace worn O-rings, seals, or damaged tips that can cause leaks [4].

- Optimize Method: Use a slower aspiration and dispensing speed, and implement a "pre-wetting" step by aspirating and dispensing the liquid several times before the actual transfer [4].

- Eliminate Bubbles: Use the instrument's priming function to purge air bubbles from the fluidic path [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Volume Inaccuracies with Viscous Liquids

- Problem: Delivered volumes are consistently less than the target volume.

- Solution: Use positive displacement technology and implement "reverse pipetting" or "pre-wetting" techniques. Manually calibrate the system for the specific viscous liquid [4].

Evaporation of Volatile Solvents

- Problem: Loss of solvent during aspiration, leading to concentrated reagents.

- Solution: Use low dead-volume tips, work in a temperature-controlled environment, and employ swift, smooth pipetting actions to minimize exposure time.

System Damage from Chemically Aggressive Solvents

- Problem: Leaking, cracked tubing, or loss of precision.

- Solution: Proactively identify solvent compatibility. Use systems with chemically inert fluid paths (e.g., PTFE tubing, FFKM seals) and ensure proper cleaning after use [5].

Air Bubbles in Samples

- Problem: Bubbles are introduced during aspiration, causing volumetric errors.

- Solution: Aspirate liquid at a slower, controlled rate with the pipette held vertically. For automated systems, optimize the aspiration speed in the method parameters. Use the priming function to clear bubbles from the system [5] [4].

Quantitative Data for Liquid Handling

Table 1: Liquid Property Ranges and Handling Recommendations

| Liquid Property | Low Range | Medium Range | High Range | Recommended ALH Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Viscosity | < 5 cP (e.g., Water, Acetone) | 5 - 100 cP (e.g., DMSO, Glycerol dilutions) | > 100 cP (e.g., Glycerol, Syrup) | Air Displacement (for low), Positive Displacement (for med/high) |

| Vapor Pressure | < 10 mmHg (e.g., Water, DMSO) | 10 - 200 mmHg (e.g., Ethanol, Acetonitrile) | > 200 mmHg (e.g., Diethyl Ether) | Systems with sealed reservoirs & low dead-volume tips |

| Chemical Aggression | Neutral (Aqueous buffers) | Moderate (Alcohols, Acetone) | High (Chlorinated solvents, Strong acids) | Systems with inert fluid paths (e.g., PTFE, PEEK) |

Data on vapor pressure and viscosity is representative and should be verified for specific solvents. ALH technology recommendations are generalized. [2] [3]

Table 2: Performance Specifications of Selected ALH Technologies

| Liquid Handling Technology | Mechanism | Viscosity Compatibility | Key Feature for Challenging Liquids |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Displacement Pipetting | Piston displaces air in a tip | Low to Medium (Up to ~20-25 cP) [3] | Disposable tips reduce cross-contamination [3]. |

| Positive Displacement | Piston moves liquid directly via syringe | Liquid-class agnostic (Wide range) [3] | High accuracy with viscous or volatile liquids [3]. |

| Non-Contact Diaphragm Pump | Diaphragm pushes liquid through a nozzle | Low to Medium (Up to ~20-25 cP) [3] | Isolated fluid path mitigates contamination risk [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Viscosity Tolerance Test for an ALH System

This protocol determines the maximum viscosity at which an automated liquid handler can maintain dispensing precision.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Automated Liquid Handler (e.g., positive displacement system)

- Glycerol-water solutions (0%, 10%, 20%, 50% v/v to create a viscosity range)

- Precision analytical balance (0.1 mg sensitivity)

- Low-evaporation microplates

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare glycerol-water solutions of known concentrations. Use a viscometer to confirm their viscosities at the assay temperature.

- System Priming: Load the liquid handler with the lowest viscosity solution (e.g., 0% glycerol). Prime the fluid path according to the manufacturer's instructions to remove air bubbles [5].

- Dispensing and Weighing: Program the handler to dispense a target volume (e.g., 10 µL) of the solution into a tared microplate well. Use the balance to measure the mass of the dispensed liquid. Repeat this at least 10 times per solution.

- Data Collection: Record the mass for each dispense. Convert mass to volume using the solution's density. Calculate the average volume, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation (CV%) for each viscosity level.

- Tolerance Threshold: The maximum tolerated viscosity is the highest value where the CV% remains below an acceptable threshold (e.g., <5%).

Protocol 2: Method for Testing Chemical Compatibility of Seals and Tubing

This protocol assesses the resistance of wetted components to chemically aggressive solvents.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Test solvents (e.g., DMSO, Acetone, Chloroform)

- Candidate seal and tubing materials (e.g., Viton, FFKM, PTFE)

- Controlled temperature incubator

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Baseline Measurement: Weigh and photograph each material sample. Measure any key mechanical properties (e.g., durometer hardness) if possible.

- Solvent Immersion: Immerse individual material samples in the test solvents in sealed vials. Include a control sample immersed in a neutral buffer.

- Incubation: Place the vials in an incubator at a defined temperature (e.g., 40°C to accelerate aging) for a set period (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours).

- Post-Test Analysis:

- Swelling/Shrinking: Remove, blot dry, and re-weigh samples. A significant mass change (>5%) indicates incompatibility.

- Visual Inspection: Examine for discoloration, cracking, or dissolution under a microscope.

- Functional Test: Install the tested materials in a liquid handler and check for leaks or performance drift.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Handling Challenging Solvents

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Displacement Tips | A tip containing a built-in piston that directly displaces liquid, eliminating an air interface. | Accurate aspiration and dispensing of viscous glycerol stocks or volatile organic solvents. |

| Chemically Inert Tubing (PTFE/PEEK) | Tubing made from polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or polyether ether ketone (PEEK) that resists a wide range of aggressive chemicals. | Creating a fluid path for acids, bases, or chlorinated solvents without risk of dissolution or leaching. |

| Perfluoroelastomer (FFKM) O-Rings | Seals made from a highly chemically resistant polymer, capable of withstanding aggressive solvents and extreme temperatures. | Replacing standard O-rings in dispensers and valves to prevent swelling and failure with DMSO or acetone. |

| Low Retention/Low Evaporation Microplates | Plates with specially treated well surfaces to minimize liquid adhesion and with seals to reduce vapor loss. | Storing and assaying volatile solvent libraries to maintain concentration and volume integrity. |

| Precision Balance | An instrument for accurate mass measurement, essential for system calibration and volume verification. | Gravimetric analysis to calibrate an ALH system's performance for a specific viscous reagent [4]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Core Fluid Path Technologies in Automated Liquid Handling

Automated liquid handling systems utilize different core technologies to move fluids, each with distinct mechanisms and compatibility profiles. Understanding these technologies is the first step in troubleshooting solvent-related issues.

What are the primary fluid path technologies used in automated liquid handlers?

The two predominant technologies are Air Displacement and Positive Displacement. A third category, Non-Contact Dispensing (which includes technologies like acoustic dispensing), offers an alternative that minimizes physical contact with samples [6] [7].

Positive Displacement Pumps move fluid by repeatedly enclosing a fixed volume and moving it mechanically through the system. This category includes both reciprocating (e.g., pistons, plungers, diaphragms) and rotary (e.g., gears, lobes, screws) designs [8]. In a liquid handler, this often involves a syringe and a disposable tip, where the piston moves the fluid directly, creating a tight seal. This makes them largely "liquid class agnostic," meaning their performance is less affected by the physical properties of the solvent, such as viscosity or vapor pressure [6].

Air Displacement Pumps function like a sophisticated automated pipette. A piston moves air within a sealed barrel, and this air pressure is used to aspirate and dispense liquid through a disposable tip. The liquid itself never enters the pump mechanism. However, this method is susceptible to the liquid's properties; differences in viscosity or vapor pressure from water can lead to inaccuracies [9].

Non-Contact Dispensing technologies, such as acoustic dispensers or micro-diaphragm pumps, transfer liquids without the dispense tip ever touching the target well or the liquid [6] [7]. This eliminates carryover contamination and is ideal for sterile applications or when working with sensitive cells. Micro-diaphragm pumps, for instance, use an isolated fluid path to achieve this [6].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these technologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Fluid Path Technologies

| Feature | Positive Displacement | Air Displacement | Non-Contact Dispensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Direct physical movement of fluid by a piston or diaphragm [8] | Movement of air to create pressure for liquid handling [9] | Acoustic energy or pressured-induced jet without tip contact [6] [7] |

| Liquid Class Compatibility | Agnostic; handles a wide range of viscosities (e.g., up to 25 cP in some systems) [6] | Sensitive to viscosity, vapor pressure, and surface tension [9] | Varies by technology; some are sensitive to properties like viscosity [6] |

| Contamination Risk | Low with disposable tips; risk of fluid contacting the piston in some designs | Low with disposable tips | Very low (no physical contact) [6] [7] |

| Typical Precision (CV) | <5% at 100 nL [6] | Varies; requires optimization for non-aqueous liquids | <2% at 100 nL for some micro-diaphragm pumps [6] |

| Best For | Viscous solvents, volatile solvents, accurate dosing [8] | Aqueous solutions, general-purpose pipetting | Sterile assays, sensitive cells, avoiding cross-contamination [6] |

Fluid Path Technology Classification

Solvent Compatibility and Chemical Resistance

What are the primary solvent compatibility concerns with different fluid path materials?

Solvent compatibility is a two-fold issue: it involves the chemical resistance of wetted materials and the physical impact of solvent properties on the dispensing mechanism.

1. Chemical Effects on Materials and Analytes: Solvents can damage pump components or, conversely, dissolve contaminants from them. More critically, the solvent can chemically alter the analytes you are trying to handle. Protic solvents like water, ethanol, and saline can participate in chemical reactions, potentially degrading reactive compounds in your sample [10]. For example, they can mediate the hydrolysis of polymers like polyurethane, leading to an inaccurate analysis of extractables and leachables [10].

2. Physical Properties and Dispensing Performance: Solvent properties directly impact the accuracy of air displacement systems.

- Viscosity: High-viscosity liquids flow less readily and may not be fully dispensed by air pressure within standard times, leading to under-dispensing.

- Vapor Pressure: Volatile solvents (high vapor pressure) can easily vaporize in the tip, forming bubbles that lead to "dripping tips" and inaccurate volumes [9].

- Surface Tension: This property affects how a liquid behaves during aspiration and dispense, including how well it wets the tip wall and forms a hanging drop.

The following table classifies common laboratory solvents and their associated challenges.

Table 2: Solvent Classification and Compatibility Challenges

| Solvent Type | Chemical Nature | Example Solvents | Primary Compatibility Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polar Protic | Reactive (O-H or N-H bonds); can act as a nucleophile or electrophile [10] | Water, Methanol, Ethanol, Saline, PBS Buffer, Acetic Acid [10] | Chemical degradation of analytes (e.g., polyurethanes, polyethers); participation in reactions [10] |

| Dipolar Aprotic | Polar but unreactive; lacks O-H/N-H bonds [10] | Acetone, Acetonitrile, Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Dimethyl Formamide (DMF), DMSO [10] | Potential for dissolving or swelling certain plastics and polymers; generally compatible with LCMS/GCMS analysis [10] |

| Non-Polar/Aprotic | Unreactive; low dielectric constant [10] | Hexane, Heptane, Cyclohexane, Toluene [10] | Can damage devices with lipophilic components (e.g., silicone); excellent for solubilizing oils, greases, and hydrocarbons [10] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Common Solvent and Fluid Path Questions

Q1: My air displacement liquid handler is dripping with a volatile organic solvent. What can I do? This is a classic issue caused by the solvent's high vapor pressure. As it vaporizes in the tip, pressure builds and forces liquid out [9].

- Solutions:

- Pre-wet Tips: Perform an aspirate and dispense cycle with the solvent before the actual transfer. This saturates the air space in the tip with solvent vapor, reducing further evaporation.

- Add an Air Gap: After aspirating your sample, aspirate a small volume of air. This creates a buffer that helps prevent droplets from trailing or dripping during the move [9].

- Use Positive Displacement Technology: If available, switch to a positive displacement system. Because the piston moves the liquid directly, it is virtually immune to problems caused by vapor pressure [8] [9].

Q2: How can I prevent cross-contamination when dispensing biological samples? Biological samples like blood, serum, or proteins can foul the fluid path, leading to carryover and inaccurate results [7].

- Solutions:

- Non-Contact Dispensing: This is the gold standard, as the tip never contacts the fluid in the receiving well [6] [7].

- Contamination-Free Sample Dispensing (Barrier Method): Use a protective barrier of a benign fluid (like high-purity water or a buffer) or an air segment to keep the sample from ever contacting the pump's internal mechanism [7].

- Disposable Tips and Fluid Paths: Always use disposable tips. For positive displacement systems, ensure the piston seal is tight and that system liquid is not mixing with the sample liquid [6] [9].

Q3: My assays with viscous reagents (e.g., glycerol solutions) are consistently under-dispensing. What is the cause? High-viscosity liquids require more time and energy to flow. Air displacement systems may not generate enough pressure or allow sufficient time for the liquid to be fully dispensed.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Liquid Handler Settings: Slow down the dispense speed significantly. Add a delay (e.g., "liquid tracking") after the dispense to allow the viscous fluid to fully drain from the tip.

- Use Positive Displacement: Positive displacement pumps are highly efficient with viscous fluids because they mechanically push the liquid out. Their efficiency often increases with viscosity [8] [6].

- Check for Bubbles: In positive displacement systems, ensure there are no bubbles in the line, as they will compress and reduce the dispensed volume [9].

Troubleshooting Common Liquid Handling Errors

The table below outlines specific errors, their likely causes, and proven solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Liquid Handling Errors

| Observed Error | Possible Source of Error | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Dripping tip or hangin drop from tip [9] | Difference in vapor pressure of sample vs. water used for instrument adjustment [9] | – Sufficiently prewet tips [9]- Add air gap after aspirate [9]- Switch to positive displacement technology |

| Droplets or trailing liquid during delivery [9] | Viscosity and other liquid characteristics different than water [9] | - Adjust aspirate/dispense speed [9]- Add air gaps and blow outs [9] |

| Incorrect aspirated volume [9] | Leaky piston/cylinder [9] | Regularly maintain system pumps and fluid lines [9] |

| Diluted liquid with each successive transfer [9] | System liquid is in contact with sample [9] | Adjust leading air gap [9] |

| First/last dispense volume difference in a sequential run [9] | Inherent to sequential dispense method and carryover [9] | Dispense first/last quantity into a reservoir or waste [9] |

| Severe peak deformation or splitting in chromatography after injection | Solvent mismatch/immiscibility between sample solvent and mobile phase [11] | Ensure sample solvent is miscible and of equal or lower elution strength than the initial mobile phase composition [11] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: In-House Solvent Compatibility Test

Before committing to a large-scale automated assay with a new solvent, a simple compatibility test can prevent instrument damage and failed experiments [12].

Goal: To define extraction conditions that will not damage the fluid path or alter the chemical composition of the sample [12] [10].

Materials:

- Device or material samples (as close to the finished product as possible)

- Candidate solvents (e.g., for simulation: hexane for non-polar, acetone for polar, distilled water for aqueous) [12]

- Non-reactive extraction vessels (e.g., clean glass jars with lids)

- Measuring cylinder

- pH paper or meter

- Warm location or incubator (e.g., 37°C, 50°C)

Procedure:

- Prepare the Device: Disassemble and cut the device/material into appropriate sections as per relevant standards (e.g., ISO 10993-12). Note any difficulties like brittleness or crumbling [12].

- Choose Solvents: Select at least one polar and one non-polar solvent to cover a range of chemical interactions [12].

- Exposure to Solvent: Place the prepared material pieces into each glass jar. Add a measured amount of solvent, enough to fully submerge the pieces. Cover the containers to prevent evaporation and place them in a warm location (e.g., 37°C) for 24-72 hours, agitating periodically if possible [12].

- Evaluate the Extract: After the exposure period, examine both the solvent and the device material for any of the following post-extraction changes [12]:

- Color Change

- Softening, Swelling, or Shrinking of the device

- Sediments or Precipitates

- pH Change (check with pH paper)

- Opacity Change

- Debris

- Dissolved Device

- Change in Total Volume of Liquid (indicating absorption)

Any observed changes indicate incompatibility and should be reported to the testing lab to determine alternate solvents or conditions [12].

Solvent Compatibility Test Workflow

Protocol: Implementing a Contamination-Free Barrier Method

This protocol uses a protective barrier to isolate biological or aggressive samples from the pump's internal mechanism [7].

Goal: To precisely dispense a biological sample without the sample contacting the pump internals, thereby preventing biofouling and cross-contamination.

Materials:

- Liquid handler with a precise syringe pump (e.g., sealed piston design)

- Appropriate tubing and dispense tip

- Barrier media (High Purity Water, Buffer Solution, or Air)

- Sample

Procedure (Liquid Barrier Method):

- Prime with Barrier Media: Fill the entire pump and fluid path with the chosen barrier media (e.g., high-purity water or a compatible buffer like PBS) [7].

- Aspirate Sample: Draw the biological sample into the tubing. The barrier media remains between the sample and the pump.

- Dispense Sample: The pump pushes the barrier media, which in turn pushes the sample out of the dispense tip. The sample never contacts the pump's internal components [7].

Procedure (Air Barrier Technique):

- Prime with Barrier Media: Fill the pump with a buffer or high-purity water [7].

- Create Air Barrier: Aspirate a precise volume of air into the fluid path, creating a compressible cushion [7].

- Aspirate Sample: Draw the biological sample into the tubing.

- Dispense Sample: The pump pushes the liquid barrier, which pushes the air barrier, which then pushes the sample out. This provides visual confirmation of the barrier's integrity [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials used to manage solvent compatibility and contamination in automated workflows.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fluid Path Management

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High Purity Water | Used as a chemically inert barrier fluid in contamination-free dispensing. Ideal when air bubbles must be avoided or with air-sensitive samples [7]. |

| Buffer Solutions (PBS, Saline) | Used as a biocompatible barrier fluid. Maintains pH and ionic strength, providing chemical compatibility with specific biological samples [7]. |

| Cottonseed Oil / Sesame Oil | Non-polar extraction vehicles used in biocompatibility testing (In-Vivo/In-Vitro models) to simulate the extraction of lipophilic compounds [12] [10]. |

| Hexane | A non-polar solvent used in analytical chemistry extractions to solubilize non-polar compounds like machine oils, lubricants, and long-chain hydrocarbons [12] [10]. |

| Acetone | A polar, dipolar aprotic solvent used in analytical chemistry extractions for a wide range of organic compounds [12] [10]. |

| Cycloolefin Microplates | Microplates with excellent chemical resistance to polar solvents (particularly DMSO), low water absorption, and high transparency for optical assays [13]. |

| Disposable Tips (Polypropylene) | Standard consumable for preventing cross-contamination between samples. Ensure material compatibility with aggressive solvents. |

| Sophoraflavanone H | Sophoraflavanone H, MF:C34H30O9, MW:582.6 g/mol |

| AH13 | AH13, MF:C34H30O8, MW:566.6 g/mol |

In automated liquid handling (ALH), solvent compatibility is not merely an operational detail but a foundational requirement for data integrity. The precise movement of liquids—aqueous buffers, organic solvents, or complex biological mixtures—is central to assays in drug discovery, genomics, and diagnostic development. When the chemical properties of a solvent are mismatched with the ALH system's materials or settings, the consequences are quantifiable and severe: systematic errors in volume delivery, contamination across samples (carryover), and ultimately, the failure of entire experimental campaigns. This guide dissects these failure mechanisms, providing researchers with a systematic framework for troubleshooting and resolution, directly supporting the broader thesis that overcoming solvent compatibility is a prerequisite for robust and reproducible automated research.

Core Concepts and Quantifiable Impacts

How Solvent Properties Drive Liquid Handling Performance

The physical and chemical properties of a solvent directly dictate its behavior within an automated liquid handler. Key properties include:

- Surface Tension and Viscosity: Affect how cleanly a liquid aspirates and dispenses, influencing the formation of droplets and the completeness of liquid ejection [14]. High-viscosity liquids require slower pipetting speeds to prevent air bubble formation [15].

- Vapor Pressure and Volatility: Highly volatile solvents (e.g., acetone, ether) can rapidly vaporize within pipette tips, leading to changes in the delivered volume and potential dripping [9] [16].

- Chemical Compatibility/Polarity: A solvent's polarity influences its "stickiness" and interaction with the plastic surfaces of pipette tips. Non-polar solvents are generally easier to manage, while polar solvents (e.g., methanol, DMSO) can exhibit "filming" or "wicking," where a thin layer of liquid creeps along the inner and outer surfaces of the tip, leading to carryover and volume inaccuracies [16]. Incompatible solvents can also chemically degrade consumables, compromising structural integrity.

Direct Consequences of Solvent Incompatibility

The mismatch between solvent properties and liquid handling parameters manifests in three primary, measurable ways:

- Poor Precision and Accuracy: Inaccurate volume delivery directly alters the concentration of critical reagents. One analysis notes that a continuous over-dispense of 20% for a high-throughput screen costing $0.10 per well could lead to an additional annual reagent cost of $750,000 [17].

- Carryover and Contamination: Solvent "filming" and inadequate washing of fixed tips can lead to analyte transfer from one sample to the next. This is a major cause of false positives/negatives in sensitive applications like PCR [14]. Research demonstrates that integrating a decontamination step with 0.17 M sodium hypochlorite for 0.2 seconds can reduce carryover of proteins like IgG and HBsAg to acceptable levels [18].

- Failed Assays and Economic Impact: The culmination of these errors is assay failure. Under-delivery of reagents can cause false negatives, potentially causing a promising drug candidate to be overlooked. Conversely, over-delivery can increase false positives, wasting resources on follow-up screenings [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

FAQ 1: My data shows inconsistent volumes and poor precision when handling organic solvents. What should I investigate?

- Possible Cause: Incorrect pipetting parameters and environmental factors are disrupting the liquid transfer.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Pipetting Parameters: For viscous liquids, use a lower flow rate to prevent air bubbles and a higher blowout volume to ensure complete ejection [15]. For volatile solvents, add a leading or trailing air gap to prevent dripping [9].

- Manage Static Charge: Static electricity can unpredictably disrupt low-volume solvent transfers. Use ionization bars to neutralize charge buildup; readings above 2 kilovolts have been shown to cause problems [16].

- Control Temperature: Ensure the laboratory environment is thermally stable, as temperature swings can affect liquid properties and volume delivery [16].

- Verify Tip Selection: Always use vendor-approved tips. Cheap, non-approved tips may have variable wettability and internal flash (residue), which directly impact delivery accuracy [17].

FAQ 2: I suspect significant carryover when using fixed tips with a series of different solvents. How can I minimize this?

- Possible Cause: Ineffective tip washing fails to remove residual solvent and analyte, leading to cross-contamination.

- Solutions:

- Implement a Robust Washing Protocol: For fixed tips, a rigorous washing routine is essential. One validated method involves exposing tips to 0.17 M sodium hypochlorite for 0.2 seconds, followed by a rinse with 2 mL of water. This 15-second procedure can reduce protein carryover to below clinically relevant levels [18].

- Consider Surface-Modified Tips: Emerging technologies, such as lubricant-infused pipette tips, create an omniphobic surface that significantly reduces sample adherence. One study showed these modified tips drastically reduced carryover residue of dyes, blood, and bacteria compared to standard polypropylene tips [14].

- Optimize Dispense Method: When sequentially dispensing, "waste" the first dispense of a multi-dispense cycle to eliminate the portion of liquid most affected by tip interaction. Using a "wet dispense" (dispensing into an existing liquid) can also help pull solution away from the tip, minimizing residue [9].

FAQ 3: My automated serial dilutions show significant deviation from the theoretical concentration. What is the root cause?

- Possible Cause: Insufficient mixing of the solution in the destination well before the next transfer, leading to inhomogeneity.

- Solutions:

- Validate Mixing Efficiency: Ensure the liquid handler's mixing step (e.g., aspirate/dispense cycles or on-deck shaking) is sufficient to create a homogenous solution. Inhomogeneity before transfer is a common cause of flawed serial dilution results [17] [9].

- Check for Sequential Dispense Errors: In protocols that involve aspirating a large volume and dispensing it sequentially across a plate, the first and last dispenses often transfer different volumes. Validate that the same volume is dispensed in each transfer, or dispense the first and last quantities into waste [9].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Performance Data of Liquid Handling Systems

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of different ALH technologies, which are critical for selecting the appropriate system for your solvents and volumes [3].

Table: Automated Liquid Handler Performance Characteristics

| Liquid Handler | Technology | Precision (CV) | Liquid Compatibility | Contamination Risk Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mantis | Micro-diaphragm Pump | < 2% at 100 nL | Up to 25 cP | Non-contact dispensing, isolated fluid path |

| Tempest | Micro-diaphragm Pump | < 3% at 200 nL | Up to 20 cP | Non-contact dispensing, isolated fluid path |

| F.A.S.T. | Positive Displacement | < 5% at 100 nL | Liquid class agnostic | Disposable tips |

| FLO i8 PD | Positive Displacement | < 5% at 0.5 µL | Liquid class agnostic | Disposable tips |

Validated Protocol for Carryover Reduction in Fixed Tips

This protocol, adapted from a published study, effectively minimizes protein carryover for liquid handlers with fixed, reusable tips [18].

- Objective: To reduce analyte carryover to levels that prevent false-positive detection in subsequent samples.

- Reagents: Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution, purified water.

- Procedure:

- Decontamination Step: Expose the pipette tips to a 0.17 M NaOCl solution for a duration of 0.2 seconds.

- Rinsing Step: Immediately following the decontamination, rinse the tips thoroughly with 2 mL of water to remove any residual decontaminant.

- Total Time: The entire washing routine takes approximately 15 seconds, making it suitable for high-throughput applications.

- Validation: This method was shown to lower carryover of IgG and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in human sera below relevant detection levels.

Workflow Diagram: Troubleshooting Solvent Incompatibility

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving common solvent-related issues in automated liquid handling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the appropriate materials is the first line of defense against solvent-related errors. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Solvent Handling

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (NaOCl) Solution | Effective decontaminant for reducing protein and peptide carryover in fixed tips [18]. | Use as part of a 15-second wash cycle (0.17 M for 0.2s) followed by a water rinse. |

| Lubricant-Infused Pipette Tips | Tips with an omniphobic surface that minimizes adhesion of viscous fluids and low-surface-tension liquids [14]. | Ideal for handling complex samples like blood, proteins, and organic solvents to reduce residue. |

| Vendor-Approved Disposable Tips | High-quality tips ensure consistent material properties, fit, and wettability for accurate volume transfer [17]. | Avoid cheap bulk tips which may have flash, variable diameter, and poor wetting properties. |

| Static Eliminator (Ionization Bar) | Neutralizes static charge buildup on plastic labware and tips, preventing disruption of low-volume liquid transfers [16]. | Critical for workflows involving volatile organic solvents. Maintain charge below 2 kV. |

| Chemical Compatibility Chart | Reference guide for determining the structural and functional stability of tip polymers against specific solvents [16]. | Essential for method development to prevent tip degradation and unwanted interactions. |

| Ophiopojaponin C | Ophiopojaponin C, MF:C46H72O17, MW:897.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Epichromolaenide | 3-Epichromolaenide, MF:C22H28O7, MW:404.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Solvent Compatibility in Automated Liquid Handling

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using solvents with automated liquid handlers, providing solutions to maintain compliance with NIH rigor and reproducibility standards.

Q1: My automated liquid handler is dripping with solvents like ethanol or acetone. What can I do?

- Cause: High vapor pressure solvents cause the air cushion in air-displacement pipettes to expand, forcing liquid out of the tip [19].

- Solutions:

Q2: How can I accurately pipette viscous liquids like glycerol without cutting the pipette tip?

- Cause: Cutting the pipette tip deforms and frays the orifice, leading to inaccurate volume delivery and potential plastic contamination [19]. High viscosity hinders liquid flow in air-displacement systems.

- Solutions:

Q3: How do I prevent foam formation when pipetting protein-rich solutions like BSA or cell culture medium?

- Cause: Foam forms during the blow-out step when air is introduced into the protein-rich sample [19].

- Solutions:

Q4: How can I be sure the fluid path materials in my instrument are compatible with my solvents?

- Cause: Chemical degradation of fluid path components (like seals, valves, tubing) can lead to failure, contamination, and inaccurate results [21].

- Solutions:

- Consult Charts: Use online chemical compatibility guides (e.g., Cole-Parmer Database) to check ratings for your specific solvents and instrument materials [21].

- Confirm Exact Materials: Identify the exact materials in your fluid path (e.g., PTFE, PFA, Borosilicate Glass, CTFE) and check compatibility with the exact chemical and its concentration [21] [22].

- Consider Conditions: Remember that compatibility can change with operating conditions like elevated temperature [21].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Solvent Compatibility for Automated Methods

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to validate solvent compatibility with your automated liquid handling system, ensuring data quality and reproducibility.

1. Pre-Experimental Planning (Authentication & Controls)

- Resource Authentication: As per NIH guidelines, document all key chemical resources, including solvent source, grade, purity, and catalog number in your Data Management Plan [23].

- Positive Controls: Include solvents known to be compatible with your system's fluid path to establish a baseline for performance.

2. Material Compatibility Assessment

- Identify Fluid Path Materials: Consult your instrument manual to identify all wetted materials (e.g., syringe barrels, plungers, valves). Example materials include:

- PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene)

- PFA (Perfluoroalkoxy alkane)

- Borosilicate Glass

- CTFE (Chlorotrifluoroethylene) [22]

- Cross-Reference with Chemical Compatibility Chart: Use a detailed chart to check the resistance rating of each material against your target solvent. The following table provides a sample of compatibility data for common laboratory solvents with materials found in instruments like the Hamilton Microlab 600 [22].

Table: Chemical Compatibility of Common Solvents with Fluid Path Materials

| Chemical | PTFE | PFA | Borosilicate Glass | CTFE (Kel-F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | A | A | A | A |

| Chloroform | A | A | A | B |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A | A | A | A |

| Ethanol | A | A | A | A |

| Glycerin | A | A | A | A |

| Hydrochloric acid (conc) | A | A | A | A |

| Sulfuric acid (conc) | A | A | A | A |

| Toluene | A | A | A | B |

| Legend: A=Excellent, B=Good, C=Moderate/Fair, D=Severe/Not Recommended [21] [22] |

3. Performance Validation Test

- Precision and Accuracy Check: Program the liquid handler to dispense the solvent in a volume relevant to your assay (e.g., 1 µL, 10 µL) across multiple replicates (n≥10).

- Gravimetric Analysis: Dispense the solvent into a sealed, tared microplate and measure the mass on a calibrated analytical balance. Calculate the dispensed volume using the solvent's density.

- Data Analysis: Determine the accuracy (deviation from target volume) and precision (Coefficient of Variation, CV%) of the dispenses. Compare results to manufacturer specifications and your assay requirements. Automated liquid handlers can achieve high precision, with some systems offering CVs of <5% at 100 nL [3].

4. Documentation for Rigor

- Detailed Metadata: Capture all (meta)data as per FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) [24]. This includes instrument model, fluid path materials, solvent identifier, calibration records, and environmental conditions.

- Reporting: Adhere to relevant minimum reporting standards where applicable (e.g., those listed on FAIRsharing.org) to ensure the reproducibility of your workflow [24].

System Selection and Workflow Diagrams

Selecting the right liquid handling technology is critical for success. The table below compares the two primary technologies for handling challenging solvents.

Table: Comparison of Automated Liquid Handling Technologies for Challenging Reagents

| Feature | Air Displacement | Positive Displacement |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | Air cushion | Piston in direct contact with liquid [20] |

| Best For | Routine aqueous solutions [20] | Viscous, volatile, or volatile liquids [19] [20] |

| Precision with Challenging Liquids | Low (affected by liquid properties) | High (immune to liquid properties) [19] |

| Contamination Risk | Mitigated by disposable tips | Mitigated by disposable tips/capillaries |

| Cost of Consumables | Lower | Higher (specialized tips) |

| Example Systems | Tecan Fluent, Agilent Bravo | Formulatrix F.A.S.T., Eppendorf ViscoTip [3] [19] |

The following diagrams outline the logical workflow for assessing solvent compatibility and troubleshooting common issues.

Diagram 1: Solvent Compatibility Assessment Workflow. This logic flow guides users from solvent identification to final approval, incorporating material checks and performance validation.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Common Solvent Handling Problems. This diagram maps specific problems, like dripping or foam, to their recommended solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and resources for ensuring solvent compatibility and reproducible automated liquid handling.

Table: Key Resources for Solvent-Compatible Automation

| Item / Resource | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Chemical Compatibility Database (e.g., Cole-Parmer) | Provides ratings on how specific chemicals interact with materials (PTFE, glass, etc.) to prevent component failure [21]. |

| Positive Displacement Liquid Handler | Automates dispensing of challenging liquids (viscous, volatile) with high accuracy by eliminating error-prone air cushions [3] [20]. |

| FAIRsharing.org Registry | A repository of reporting standards; using these standards ensures (meta)data is complete and reusable, fulfilling NIH FAIR principles [24]. |

| Investigation/Study/Assay (ISA) Framework | A structured tool for collecting and organizing experimental (meta)data, critical for rigor, reproducibility, and data sharing [24]. |

| Resource Authentication Plan | An NIH-recommended document to record the source and validation of key biological/chemical resources (e.g., solvents, antibodies) [23]. |

| Validated Solvents & Reagents | Chemicals that have been documented with source, purity, and lot number, as required for rigorous and reproducible experimental workflows [23]. |

| Qianhucoumarin E | Qianhucoumarin E, MF:C19H18O6, MW:342.3 g/mol |

| Stilbostemin N | Stilbostemin N, MF:C16H18O3, MW:258.31 g/mol |

Practical Solutions: Selecting Hardware and Designing Methods for Difficult Solvents

System Selection and Compatibility Guide

Q: What specifications should I look for in a tipless, non-contact dispenser to handle aggressive solvents and viscous liquids?

A: Selecting the right system is critical for success. Key specifications focus on chemical compatibility, precision with challenging fluids, and specialized hardware. The core components of a system designed for this purpose are illustrated below.

For aggressive solvents, the wetted materials are the most important factor. Look for systems featuring chemically resistant materials like Perfluoroelastomer (PFE) diaphragms and Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene (FEP) body components, which offer exceptional compatibility for aggressive solvents and corrosive reagents [25]. This hardware enables performance that meets critical benchmarks for viscosity handling and precision.

Table 1: Performance Specifications for Aggressive and Viscous Solvent Handling

| Parameter | Target Specification | Example Performance & Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| Volume Range | 0.1 µL to millilitres | From 100 nL, enabling reaction miniaturization [25] |

| Dispensing Precision | CV < 2% | As low as 0.2% CV for continuous flow, even with viscous fluids [25] |

| Viscous Liquid Handling | Capability for high viscosities | Accurate dispensing of 70% glycerol and 100% glycerol [25] |

| Chemical Compatibility | Resistance to aggressive solvents | PFE and FEP components for corrosive reagents [25] |

| Dead Volume | Minimal to conserve reagents | As low as 6 µL using pipette tips as reservoirs [25] |

Q: What common solvent types are compatible with these specialized systems?

A: Tipless non-contact dispensers with appropriate hardware can handle a wide range of challenging liquids, from volatile solvents to complex biological suspensions [25].

Table 2: Solvent and Reagent Compatibility Guide

| Solvent/Reagent Category | Examples | Compatibility & Handling Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Viscosity Reagents | 70% Glycerol, 100% Glycerol, DMSO, Mastermix | Handled accurately with continuous flow or high-viscosity chips [25] |

| Aggressive/Chemical Solvents | Corrosive reagents, aggressive chemicals | Compatible with systems using PFE diaphragms and FEP fluidic paths [25] |

| Bead & Cell Suspensions | Magnetic beads, primary neurons, suspension cells | Gentle dispensing action maintains viability and uniform dosing [25] |

| Volatile Viscous Liquids | Glycerol/PEG blends with ethanol or isopropanol | Requires reduced dispensing flow rate and air gaps to counter dripping [26] |

| Viscous Surfactants | Tween 20, Triton X-100 (up to 400 mPa) | Requires slower aspiration and dispensing flow rates [26] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Protocols

Q: My viscous reagents are dispensing inaccurately. What methodological adjustments can I make?

A: Inaccurate dispensing of viscous liquids is often related to flow control and technique. Follow this logic to diagnose and resolve the issue.

Implement these specific experimental protocols to address the root causes:

- Protocol for Reverse Pipetting: Draw more liquid into the dispenser than is needed, then dispense the desired volume, leaving the excess behind. This technique is particularly useful for reducing the formation of air bubbles and ensuring accurate volumes with viscous solutions [26].

- Protocol for Two-Step Dispensing: Initially dispense a portion of the liquid slowly to ensure accurate volume transfer, then dispense the remainder more rapidly. This two-phase approach ensures controlled release, minimizing air entrapment [26].

- Protocol for Flow Rate Adjustment: For viscous surfactant liquids and oils, significantly reduce the aspiration and dispensing flow rates. This provides ample time for the liquid to slide off the interior wall of the fluid path, ensuring a complete dispense [26].

Q: How do I prevent dripping when dispensing volatile viscous solvents?

A: Volatile viscous liquids (e.g., glycerol/PEG blends with ethanol or isopropanol) have high vapor pressure which causes dripping. To counteract this:

- Use the default aspiration flow rate.

- Reduce the dispensing flow rate to combat dripping from higher vapor pressure.

- Add an air gap after aspiration to create a buffer that prevents solvent escape [26].

Q: My system is experiencing premature wear when handling aggressive solvents. What should I check?

A: Premature wear indicates a chemical compatibility failure. Verify that your system is equipped with solvent-resistant components. Specifically, ensure the fluid path uses a Perfluoroelastomer (PFE) diaphragm and Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene (FEP) body, which are designed to deliver exceptional chemical compatibility for aggressive solvents and corrosive reagents, ensuring robustness and precision [25].

Experimental Validation and QC Methods

Q: What quality control procedures ensure my dispenser is performing accurately with these challenging liquids?

A: Implement a rigorous QC protocol using gravimetric analysis and integrated droplet verification.

- Gravimetric QC Protocol: Use an analytical balance to weigh dispensed samples of your target solvent. Gravimetric preparation relies on the much lower error of the balance compared to volumetric methods, allowing for over 90% solvent savings while generating the same analytical results [27]. Perform this check regularly to detect calibration drift.

- Droplet Detection QC: Utilize integrated QC stations that use LEDs and optical sensors to confirm proper chip function by detecting the presence of dispensed drops. This technology allows the system to automatically verify if drops are dispensed at the beginning and end of each run, providing confidence in dispense quality and traceability [25].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High Viscosity CF Chip | Designed to accurately dispense high-viscosity fluids like 100% glycerol [25]. |

| XL PFE Chip | A large-volume diaphragm chip with a PFE diaphragm and FEP body for aggressive chemical compatibility [25]. |

| Continuous Flow (CF) Chip | Enables bulk dispensing at rates >600 µL/sec for quick normalization and handling of viscous solvents [25]. |

| Low Retention Tips | (For tip-based systems) Crafted from unique polypropylene or hydrophobic coatings to minimize liquid adhesion, ensuring maximum sample recovery of precious viscous samples [26]. |

| Positive Displacement Tips | (For tip-based systems) Feature an integrated piston that directly interacts with the liquid, bypassing the air cushion for precise and complete dispensing of viscous or volatile liquids [26]. |

| Analytical Balance | For gravimetric quality control, verifying dispensing accuracy by weighing dispensed samples [27]. |

| Taiwanhomoflavone B | Taiwanhomoflavone B, MF:C32H24O10, MW:568.5 g/mol |

| Gambogellic Acid | Gambogellic Acid, MF:C38H44O8, MW:628.7 g/mol |

Automated liquid handling (ALH) systems are essential for assay development and optimization in modern laboratories, playing a critical role in diagnostics, drug discovery, genomics, and proteomics [3]. However, researchers face significant challenges with liquids that have unique physical properties, such as varied viscosity, surface tension, density, and vapor pressure [28] [29]. These characteristics directly impact how liquids behave during pipetting, necessitating precise calibration and system adjustments to ensure accurate transfers.

Traditional air displacement pipetting relies on a compressible air cushion to move liquids, requiring specific "liquid classes" – predefined parameters that account for a liquid's physical properties to guide mechanical actions like aspiration speed and dispensing timing [29]. Creating and optimizing these liquid classes demands substantial time and resources. This process becomes particularly problematic with volatile solvents (like DMSO, methanol, or acetone) that can evaporate into the air cushion, or viscous liquids (like glycerol or oils) that resist flow, leading to volume inaccuracies and compromised data integrity [29].

Positive displacement technology offers a fundamentally different approach that circumvents these challenges. Unlike air displacement systems, positive displacement pipetting operates without an air cushion, making it liquid class agnostic – it delivers accurate performance across a wide range of liquids without requiring parameter adjustments for different liquid properties [30]. This capability significantly simplifies method development, especially in workflows involving multiple solvent types or challenging reagents.

How Positive Displacement Technology Works

Fundamental Operating Principles

Positive displacement technology operates on a straightforward mechanical principle: it traps a fixed volume of liquid and forcibly displaces it from the inlet to the outlet [31] [32]. In the context of automated liquid handling, this means the piston responsible for moving the liquid comes into direct contact with the liquid itself [30]. This direct-contact, piston-based pipetting action eliminates the compressible air cushion used in air displacement systems, creating a direct mechanical link between the piston movement and liquid volume transferred.

The working process involves a repeating cycle: as the pump or pipettor operates, it creates an expanding cavity on the suction side, drawing fluid in. This cavity then seals, transporting the fluid to the discharge side where the cavity collapses, forcibly ejecting the fluid [32]. When operating at a constant speed, a positive displacement system consistently moves the same volume of liquid in each cycle, providing exceptional accuracy and predictable flow rates ideal for laboratory applications [31].

Comparison with Air Displacement Pipetting

The fundamental differences between positive displacement and air displacement technologies create distinct advantages and limitations for each approach:

Table: Comparison of Positive Displacement vs. Air Displacement Pipetting Technologies

| Feature | Positive Displacement | Air Displacement |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Contact | Piston directly contacts liquid [30] | Air cushion separates piston from liquid [29] |

| Liquid Class Requirements | Liquid class agnostic [3] [30] | Requires specific liquid classes [29] |

| Viscosity Handling | Excellent for viscous liquids [29] | Challenged by high viscosity [29] |

| Volatile Liquid Performance | Minimal evaporation loss [29] | Prone to evaporation and volume inaccuracies [29] |

| Cross-Contamination Risk | Low (with disposable tips/pistons) [30] | Managed through tip changes [33] |

| Typical Precision (CV) | <5% at 100 nL [3] | Varies significantly with liquid class |

Diagram: Technology Comparison - How piston implementation creates different outcomes

The critical distinction lies in how each technology manages the interface between the driving mechanism and the liquid. Positive displacement systems completely eliminate the air interface that causes many liquid-class-dependent errors, particularly with volatile solvents where vapor pressure issues lead to inaccuracies, and viscous liquids where resistance to flow affects volume delivery [29].

Key Advantages in Method Development

Simplified Protocol Development

Positive displacement technology dramatically reduces method development time by eliminating the need for liquid class optimization. Researchers can develop protocols without characterizing physical properties for each new reagent or creating extensive parameter sets to handle different solvent types [30]. This simplification is particularly valuable in early-stage research where reagent formulations may frequently change, or in high-throughput screening environments dealing with diverse compound libraries containing various solvents.

The technology's consistency across different liquid types also enhances protocol transferability between laboratories. Methods developed using positive displacement systems are more easily reproduced across different sites and instruments because they don't depend on locally-optimized liquid classes that can vary between systems and operators [33]. This promotes better collaboration and data consistency in multi-site research organizations.

Performance with Challenging Liquids

Positive displacement technology excels precisely where air displacement systems struggle most, offering particular advantages for:

Viscous Liquids: Substances like glycerol, polyethylene glycol, oils, and biological fluids resist flow in air displacement systems, often requiring significantly slowed aspiration and dispensing speeds. Positive displacement handles these materials effectively because the direct piston action physically pushes viscous liquids without the compressibility issues of an air cushion [29]. Systems can maintain coefficients of variation (CV) below 5% even for volumes greater than 20 μL with highly viscous materials [29].

Volatile Solvents: Organic solvents like DMSO, methanol, acetone, and ethanol have high vapor pressure that causes evaporation into the air cushion of traditional pipettors, leading to volume loss and concentration errors [29]. Positive displacement eliminates this issue by removing the air cushion entirely, preventing evaporation during the transfer process. This is particularly critical in drug discovery workflows where accurate compound transfer directly impacts assay results [33].

Complex Biological Samples: Samples containing proteins, surfactants, or other components that alter surface tension or foaming characteristics perform more consistently with positive displacement technology. The direct mechanical action minimizes foaming and provides consistent dispensing regardless of liquid composition [30] [28].

Table: Performance Comparison Across Liquid Types

| Liquid Type | Challenge | Positive Displacement Solution | Typical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Low viscosity, surface tension | Consistent performance without parameter adjustment | CV <2% for volumes >5μL [29] |

| Viscous Liquids | High resistance to flow | Direct mechanical displacement without air cushion | CV <5% for volumes >20μL [29] |

| Volatile Solvents | Evaporation into air cushion | No air space eliminates evaporation | Accurate dosing without volume loss [29] |

| Foaming Liquids | Tendency to create bubbles | Reduced turbulence from controlled displacement | Maintains sample integrity [28] |

Contamination Control and Miniaturization

The physical design of positive displacement systems provides inherent advantages for contamination-sensitive applications and volume-limited workflows:

Reduced Cross-Contamination: Most positive displacement liquid handlers use disposable tips or pistons that are replaced between samples, effectively preventing carryover [30]. This is particularly valuable in PCR setup, NGS library preparation, and other molecular biology applications where minute contaminants can compromise results.

Miniaturization Capabilities: By eliminating the dead volume often associated with air displacement systems and their required air gaps, positive displacement technology enables more reliable low-volume dispensing [3]. This allows researchers to reduce reaction volumes significantly – in some cases up to 50 times – conserving precious reagents and enabling high-density plate formats without sacrificing accuracy [29]. Systems like the Mantis and Tempest can accurately dispense volumes in the nanoliter range (100-200 nL) with precision CVs under 3% [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

Even with robust positive displacement technology, users may encounter operational challenges. This troubleshooting guide addresses the most common issues:

Problem: Inconsistent Dispensing Volumes

- Possible Cause: Air bubbles in the fluid path or tip.

- Solution: Prime the system several times before use. For manual systems, tap the tip to dislodge bubbles. Ensure proper immersion depth during aspiration (typically 2-3 mm below the surface) [33].

- Prevention: Use slower aspiration speeds for viscous liquids and avoid jerky movements during immersion.

Problem: Droplet Retention on Tip Exterior

- Possible Cause: Surface tension properties of the liquid.

- Solution: Use a steeper touch-off angle and longer post-dispense delay to allow complete liquid ejection [29]. Ensure the dispensing method (contact vs. non-contact) matches the application requirements.

- Prevention: For problematic liquids, consider using low-retention tips if available for your system.

Problem: Clogging with Particulate Samples

- Possible Cause: Particles in the sample blocking the fluid path.

- Solution: Centrifuge samples to remove particulates before loading. Use filters during sample preparation when possible.

- Prevention: For unavoidable particulates, use tips with larger orifice sizes or consider pre-filtration steps.

Problem: System Error Messages or Calibration Failures

- Possible Cause: Worn components or improper installation.

- Solution: Check manufacturer documentation for specific error codes. Verify all disposable components are properly seated. Perform routine maintenance as scheduled.

- Prevention: Follow recommended maintenance schedules and use only manufacturer-approved consumables.

Method Verification Protocols

Regular verification of liquid handling performance is essential for maintaining data integrity. These protocols are particularly important when working with critical reagents or when transitioning methods between systems:

Protocol 1: Gravimetric Verification

- Prepare purified water and a clean, tared microplate or tubes.

- Record environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) as they affect evaporation.

- Program the liquid handler to dispense specific volumes into multiple wells (≥8 replicates recommended).

- Weigh each dispense immediately using an analytical balance.

- Convert mass to volume using water's density at the recorded temperature.

- Calculate accuracy (% of target volume) and precision (%CV) across replicates.

- Compare results to manufacturer specifications and historical performance data.

Acceptance Criteria: For volumes ≥5 μL, precision should typically be <5% CV, with accuracy within ±5% of target volume [29].

Protocol 2: Photometric Verification (for Aqueous Solutions)

- Prepare a dye solution of known concentration (e.g., tartrazine or other suitable dye).

- Dispense the dye solution into a known volume of buffer.

- Measure absorbance using a plate reader and compare to standard curves.

- Calculate dispensed volumes based on concentration dilution.

Protocol 3: Serial Dilution Verification

- Prepare a concentrated solution of a compound with known absorbance characteristics.

- Perform a serial dilution series across a microplate.

- Measure absorbance at each dilution level.

- Compare measured values to expected theoretical concentrations.

- Assess mixing efficiency by consistency across replicates.

This protocol specifically verifies both volume transfer accuracy and mixing efficiency, which is critical for serial dilution applications [33].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What types of liquids are particularly well-suited for positive displacement technology?

Positive displacement excels with challenging liquids that typically cause problems for air displacement systems. This includes viscous liquids like glycerol and oils, volatile solvents like DMSO and acetone, foaming solutions, and liquids containing detergents or proteins that alter surface tension [30] [29]. The technology is essentially universal across liquid types, eliminating the need for different handling protocols.

Q2: How does positive displacement technology reduce cross-contamination risk?

Most systems use disposable tips or pistons that are replaced between samples, preventing any fluid path contact between different reagents [30]. This is superior to fixed-tip systems that require washing protocols, which may not completely eliminate carryover [33]. For non-contact dispensers, isolated fluid paths prevent contamination between different reagents [3].

Q3: Can positive displacement systems handle the high-throughput needs of screening laboratories?

Yes, modern positive displacement systems are designed for medium to high-throughput applications. Systems like the Tempest offer medium to high throughput, while the F.A.S.T. and FLO i8 PD liquid handlers provide medium to high throughput capabilities suitable for screening environments [3]. The technology's reliability with diverse solvents makes it particularly valuable for compound management and high-throughput screening operations.

Q4: What are the maintenance requirements for positive displacement systems?

Maintenance varies by system design. Tipless dispensers like the Mantis and Tempest have fluid paths that may require periodic cleaning or replacement [3]. Systems using disposable tips benefit from simpler maintenance as the wetted components are regularly replaced. Generally, positive displacement systems have fewer liquid-class-related maintenance issues but may require attention to mechanical components over time [30].

Q5: How does positive displacement technology impact experimental costs?

While consumables costs exist for disposable tips, the technology provides cost savings through reduced reagent consumption (enabling miniaturization), elimination of liquid class optimization time, and improved data quality that reduces repeat experiments [3] [29]. One study demonstrated a 60% reduction in assay reagent costs through miniaturization enabled by precise liquid handling [3].

Q6: What volume ranges can positive displacement systems handle?

Positive displacement technology covers a broad volume spectrum. For example, the Mantis system handles 100 nL to infinite volumes, while the FLO i8 PD manages 200 nL to 1 mL [3]. The technology is particularly robust at low volumes where air displacement systems struggle with evaporation and surface tension effects.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of positive displacement technology involves more than just the instrumentation. The table below outlines key reagents and materials essential for optimizing workflows:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Positive Displacement Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer-Approved Tips | Ensure precision and accuracy | Vendor-approved tips maintain performance specifications; off-brand tips may affect results [33] |

| DMSO-Compatible Components | Handle volatile solvents | Verify chemical compatibility for all fluid path components [29] |

| Viscous Liquid Standards | System verification | Glycerol solutions at various concentrations for performance validation [29] |

| Aqueous Dye Solutions | Volume verification | For gravimetric or photometric system calibration [33] |

| Cleaning Solutions | Decontamination | Appropriate solvents for flushing systems between different reagents [33] |

| PCR-Compatible Tips | Molecular biology applications | RNase/DNase-free tips for sensitive molecular workflows [30] |

Positive displacement technology represents a significant advancement in automated liquid handling by eliminating liquid class dependencies that complicate method development and introduce error sources. This technology simplifies workflows while improving performance with the most challenging liquids, from volatile organic solvents to viscous biochemical solutions.

For researchers developing assays involving multiple solvent types or transitioning methods between laboratories, positive displacement systems offer a more robust and reproducible platform that reduces optimization time and enhances data quality. By physically displacing fixed liquid volumes through direct piston action, these systems overcome fundamental limitations of air displacement pipetting, particularly for nanoliter-scale volumes where surface tension and evaporation effects are most pronounced.

As drug discovery and life science research increasingly rely on complex reagent systems and miniaturized assays, liquid class agnostic technologies will play a growing role in ensuring reproducible, high-quality results across diverse research environments.

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions for Automated Dispersion

| Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Dispersion/Precipitation | Bio-based solvent viscosity too high for dispenser [3] | Verify solvent viscosity is within instrument specification (e.g., < 25 cP for tipless dispensers) [3]. Pre-warm solvents to lower viscosity. |

| Clogged Dispenser Lines/Nozzles | Solvent evaporation in lines; particle formation from solvent breakdown | Implement regular flush cycles with a compatible "wash" solvent. Use non-contact dispensing technology where possible to isolate the fluid path [3]. |

| Inconsistent Dispensing Volumes | Solvent hygroscopicity altering density/viscosity; absorption of water from air | Ensure sealed solvent reservoirs. Use instrument protocols to purge lines before precise dispensing. Use positive displacement tips for volatile solvents [3]. |

| Irreproducible Experimental Results | Unaccounted solvent properties (e.g., vapor pressure, polarity) affecting chemistry [34] | Ensure sample is dissolved in the starting mobile phase composition to avoid solvent strength mismatch [34]. |

| System Errors/Communication Failure | Incompatibility between legacy automation infrastructure and new systems [35] | Check all hardware connections and software drivers. Consult automation provider for firmware updates or compatibility layers [35]. |

Method Development and Optimization Challenges

| Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Selectivity in Separation | Poor solvent blend selectivity for target analytes | Use a Bayesian optimization framework to efficiently explore the solvent mixture design space, balancing exploration and exploitation [36]. |

| Peak Tailing or Broadening | Basic compounds interacting with silanol groups; high extra-column volume [34] | Use high-purity silica columns. Add a competing base like triethylamine to the mobile phase. Use short, narrow-bore capillary connections [34]. |

| High Baseline Noise/Artifacts | Solvent impurities or high background absorption | Use high-purity (HPLC-grade) solvents. Employ thorough degassing to remove dissolved oxygen, which can cause quenching [34]. |

| Failed DoE Protocol Execution | Human error in complex liquid handling steps; manual pipetting inaccuracies [3] | Utilize automated liquid handlers (ALH) with user-friendly interfaces to execute complex Design of Experiments (DoE) protocols with high precision and reproducibility [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Solvent Compatibility and Selection

Q1: What are the key physical properties I need to check before using a bio-based solvent in my automated liquid handler? A1: The most critical properties are viscosity and vapor pressure.

- Viscosity: Must be within the operating range of your dispenser. For example, tipless dispensers like the Mantis can handle viscosities up to 25 cP [3]. High viscosity can lead to poor precision, clogging, and inaccurate volumes.

- Vapor Pressure: Highly volatile solvents can evaporate in lines or tips, leading to bubble formation and inaccurate dispensing, especially with positive displacement systems.

Q2: How can I quickly find an effective green solvent mixture for my specific application without exhaustive trial-and-error? A2: Machine learning approaches like Bayesian experimental design can streamline this process. This framework uses statistical models to intelligently guide experimentation [36]. It works in a "Design-Observe-Learn" cycle, sequentially selecting the most informative solvent mixtures to test, thereby converging on an optimal blend with far fewer experiments than traditional methods [36].

Q3: My bio-based solvent is causing peak tailing in my HPLC analysis. What should I do? A3: Peak tailing often indicates undesirable interactions with the column. First, ensure your sample is dissolved in a solvent compatible with the starting mobile phase [34]. If the problem persists, consider modifying the mobile phase by using a high-purity silica column or adding a competing base like triethylamine. For fundamental issues, you may need to select a different bio-based solvent with properties that reduce these interactions [34].

System Operation and Automation

Q4: What is the best way to transition from a traditional chlorinated solvent to a bio-based one in an automated workflow? A4: Adopt a staged, validated approach:

- Compatibility Check: Verify the new solvent works with all wetted parts of your automation (seals, tubing, etc.).

- Performance Benchmarking: Run a controlled experiment comparing the new solvent against the old one using key performance metrics (e.g., yield, purity, precision).

- Protocol Optimization: Adjust automated method parameters like mixing speed, incubation time, or dispense height to account for differences in density, viscosity, and surface tension.

- Full Validation: Once optimized, formally validate the new method to ensure reproducibility [37].

Q5: My automated system has stopped working after I switched to a new bio-based solvent. The error code is unclear. What are the first steps I should take? A5: Follow a systematic troubleshooting strategy [35]:

- Identify and Define: Clearly note the error message and when it occurs in the protocol.

- Gather Data: Check the system's activity logs and review the exact step that fails.

- List Possibilities: Common issues include solvent viscosity outside instrument specs, incompatible tubing, or a simple clog.

- Run Diagnostics: Perform a flush with a known-compatible solvent and inspect the fluidic path for blockages or leaks. If the issue persists, contact the equipment vendor's support team, as they are experts in resolving such hardware-software-solvent interactions [35].

Q6: How can I ensure my automated methods using bio-based solvents are reproducible when transferring them to another lab? A6: Key factors for successful technology transfer include:

- Detailed Documentation: Precisely document solvent suppliers, grades, and any pre-treatment steps.

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure the automated liquid handlers in both labs are calibrated for the specific bio-based solvents used.

- Standardized Protocols: Use automated liquid handling to eliminate manual pipetting variability, which is crucial for complex DoE protocols [3].

- Shared Data: Provide all raw data and model parameters if a machine-learning-guided solvent selection was used [36].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Bayesian Optimization for Solvent Selection

Automated Dispersion Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Materials for Automated Dispersion Experiments

| Item | Function & Relevance to Green Chemistry |

|---|---|

| Bio-Based Solvents (e.g., Lactates, Gluconates, Plant-Derived Alcohols) | Primary dispersion media. Derived from renewable resources (plants, vegetables), offering biodegradability, low toxicity, and reduced carbon footprint compared to petrochemical solvents [37]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler (ALH) | Enables precise, high-throughput dispensing of solvent blends. Essential for executing complex DoE protocols with reproducibility and minimal human error [3]. |

| Liquid-Handling Robot | Allows for batch automation of experiments, crucial for efficiently testing the multiple solvent mixtures suggested by machine learning algorithms [36]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | A machine learning framework that intelligently guides solvent selection by balancing the exploration of new mixtures with the exploitation of promising candidates, drastically reducing experimental workload [36]. |

| COSMO-RS (Conductor-like Screening Model for Real Solvents) | A physics-based model used to predict solvent properties. It can be integrated with machine learning to generate initial data or "fantasy samples" to improve the model when experimental data is scarce [36]. |

| HPLC/UHPLC System with MS Detection | Used for precise analysis and quantification of separation efficiency, impurity profiles, and reaction outcomes when testing the performance of new bio-based solvent systems [38] [34]. |

| High-Purity Silica or Polar-Embedded Columns | HPLC columns designed to minimize undesirable interactions (e.g., peak tailing) with basic compounds, which is critical when characterizing separations using novel solvent mixtures [34]. |

| Taccalonolide C | Taccalonolide C, MF:C36H46O14, MW:702.7 g/mol |

| 5-Epicanadensene | 5-Epicanadensene, MF:C30H42O12, MW:594.6 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Clogging in Positive-Pressure Filtration Systems

Problem: Filter membranes in a positive-pressure, centrifugation-free system are becoming clogged, leading to slow flow rates and reduced sample recovery.

Explanation: Clogging occurs when protein precipitates or other particulates accumulate on or within the filter membrane. In a standard vacuum or pressure setup, precipitates immediately contact the membrane upon loading. A specialized cartridge design can position the precipitate beneath the filter membrane. The system first draws the clarified supernatant through the membrane, with the precipitate only contacting it at the final compression stage, thereby preventing clogging [39].

Solution: