Overcoming Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Experimentation: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Data and Reliable Discovery

Spatial bias presents a significant and pervasive challenge in high-throughput screening (HTS) and multiwell plate assays, threatening data quality and the validity of hit identification in drug discovery.

Overcoming Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Experimentation: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Data and Reliable Discovery

Abstract

Spatial bias presents a significant and pervasive challenge in high-throughput screening (HTS) and multiwell plate assays, threatening data quality and the validity of hit identification in drug discovery. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete framework for understanding, identifying, correcting, and validating solutions for spatial bias. We explore the foundational sources of bias, from liquid handling to environmental gradients, and detail advanced correction methodologies including median filters and model-based approaches. The content further tackles troubleshooting for complex bias patterns and offers a critical comparison of validation techniques to ensure unbiased, high-quality data, ultimately safeguarding the drug discovery pipeline from costly false leads and enhancing the reliability of scientific outcomes.

Understanding Spatial Bias: The Hidden Enemy in High-Throughput Data

Understanding Spatial Bias in High-Throughput Screening

Spatial bias is a major challenge in high-throughput screening (HTS) technologies, representing systematic errors that negatively impact data quality and hit selection processes [1]. This bias manifests as non-random patterns in experimental data correlated with physical locations on assay plates, leading to increased false positive and false negative rates during hit identification [1].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Spatial Bias: A systematic error in high-throughput experiments where measurements are influenced by the physical location of samples on the experimental platform (e.g., micro-well plates), rather than solely reflecting biological truth [1].

High-Throughput Screening (HTS): A drug discovery technique that rapidly conducts millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological experiments using robotic handling systems, liquid handling systems, and data mining tools to assess biological or biochemical activity of compounds [1].

Key Spatial Bias Patterns

Table 1: Common Spatial Bias Patterns in HTS

| Pattern Type | Description | Common Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Edge Effects | Systematic over or under-estimation of signals in perimeter wells, particularly plate edges | Reagent evaporation, temperature gradients, cell decay [1] |

| Row/Column Effects | Consistent patterns along specific rows or columns | Pipetting errors, liquid handling system malfunctions [1] |

| Additive Bias | Constant value added or subtracted from measurements regardless of signal intensity | Reader effects, time drift in measurement [1] |

| Multiplicative Bias | Bias proportional to the signal intensity | Variation in incubation time, reagent concentration differences [1] |

| Gradient Patterns | Continuous changes in measurements across the plate | Temperature gradients, evaporation gradients [1] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Spatial bias in HTS arises from multiple technical and procedural factors [1]:

- Reagent evaporation: Uneven evaporation across plates, particularly affecting edge wells

- Liquid handling errors: Pipette calibration issues or malfunctioning liquid handling systems

- Time-dependent effects: Measurement time drift between different wells or plates

- Environmental factors: Temperature gradients, uneven heating, or cooling across plates

- Biological variability: Cell decay or uneven cell distribution across wells

- Reader effects: Instrument-based measurement variations across the plate

FAQ 2: How can I quickly identify if my experiment is affected by spatial bias?

Perform these diagnostic checks [1]:

- Visual inspection: Plot raw measurements using heatmaps arranged in plate layout

- Statistical testing: Apply Mann-Whitney U test or Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test to compare edge versus interior well measurements

- Pattern recognition: Look for systematic row, column, or edge patterns rather than random distributions

- Control analysis: Examine control well performance across plate locations

- Assay comparison: Check if similar patterns appear across multiple plates in the same assay

FAQ 3: What is the difference between additive and multiplicative spatial bias?

Table 2: Additive vs. Multiplicative Spatial Bias

| Characteristic | Additive Bias | Multiplicative Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Model | Constant value added to measurements: observed = true + bias |

Value multiplied with measurements: observed = true × bias |

| Impact on Data | Affects all measurements equally regardless of signal intensity | Impact scales with signal intensity |

| Visual Pattern | Uniform shift across affected regions | Proportional scaling across affected regions |

| Common Causes | Reader baseline drift, background interference | Variation in reagent concentration, incubation time effects [1] |

| Correction Approach | Median polishing, B-score method [1] | Normalization methods, robust Z-scores [1] |

FAQ 4: Which statistical methods are most effective for spatial bias correction?

Based on comparative studies of ChemBank datasets, the following methods show effectiveness [1]:

- For plate-specific bias: Additive and multiplicative PMP (Plate Model Pattern) algorithms

- For assay-specific bias: Robust Z-score normalization

- Traditional methods: B-score correction for row/column effects, Well Correction for location-specific biases

- Combined approach: PMP algorithms followed by robust Z-score normalization provides optimal results

Simulation studies show the combined PMP with robust Z-score approach yields higher hit detection rates and lower false positive/negative counts compared to B-score or Well Correction methods alone [1].

Experimental Protocols for Bias Identification and Correction

Protocol: Comprehensive Spatial Bias Assessment

Purpose: Systematically identify and characterize spatial bias in HTS data [1]

Materials:

- Raw HTS measurement data with plate layout information

- Statistical software (R, Python with appropriate packages)

- Visualization tools for heatmap generation

Procedure:

- Data Organization: Arrange data according to physical plate layout (rows × columns)

- Visualization: Generate heatmaps of raw measurements for each plate

- Pattern Identification: Document any systematic spatial patterns (edge effects, row/column trends, gradients)

- Statistical Testing:

- Apply Mann-Whitney U test (α=0.01 or 0.05) to compare edge vs. interior wells

- Use Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test for distribution comparisons

- Bias Classification: Determine if patterns indicate additive or multiplicative bias

- Assay Consistency: Check if similar patterns appear across multiple plates in the same assay

Interpretation: Consistent spatial patterns across multiple plates suggest assay-specific bias, while plate-specific patterns indicate technical variations in individual plates [1].

Protocol: Spatial Bias Correction Using PMP and Robust Z-Scores

Purpose: Effectively correct both plate-specific and assay-specific spatial biases [1]

Materials:

- HTS data with identified spatial bias

- Computational resources for statistical processing

- R or Python environment with custom scripts for PMP algorithms

Procedure:

- Plate-Specific Correction:

- Apply additive PMP algorithm for constant bias patterns

- Apply multiplicative PMP algorithm for proportional bias patterns

- Determine appropriate model using goodness-of-fit metrics

Assay-Specific Correction:

- Calculate robust Z-scores using median and median absolute deviation

- Apply across all plates within the same assay

Hit Identification:

- Use μp - 3σp threshold for hit selection, where μp and σp are the mean and standard deviation of corrected measurements in plate p

- Validate hits with control well performance

Quality Assessment:

- Generate post-correction heatmaps to verify bias removal

- Compare hit lists before and after correction

- Assess false positive/negative rates using control compounds

Validation: The method should improve true positive rates and reduce false positive/negative counts compared to uncorrected data or single-method approaches [1].

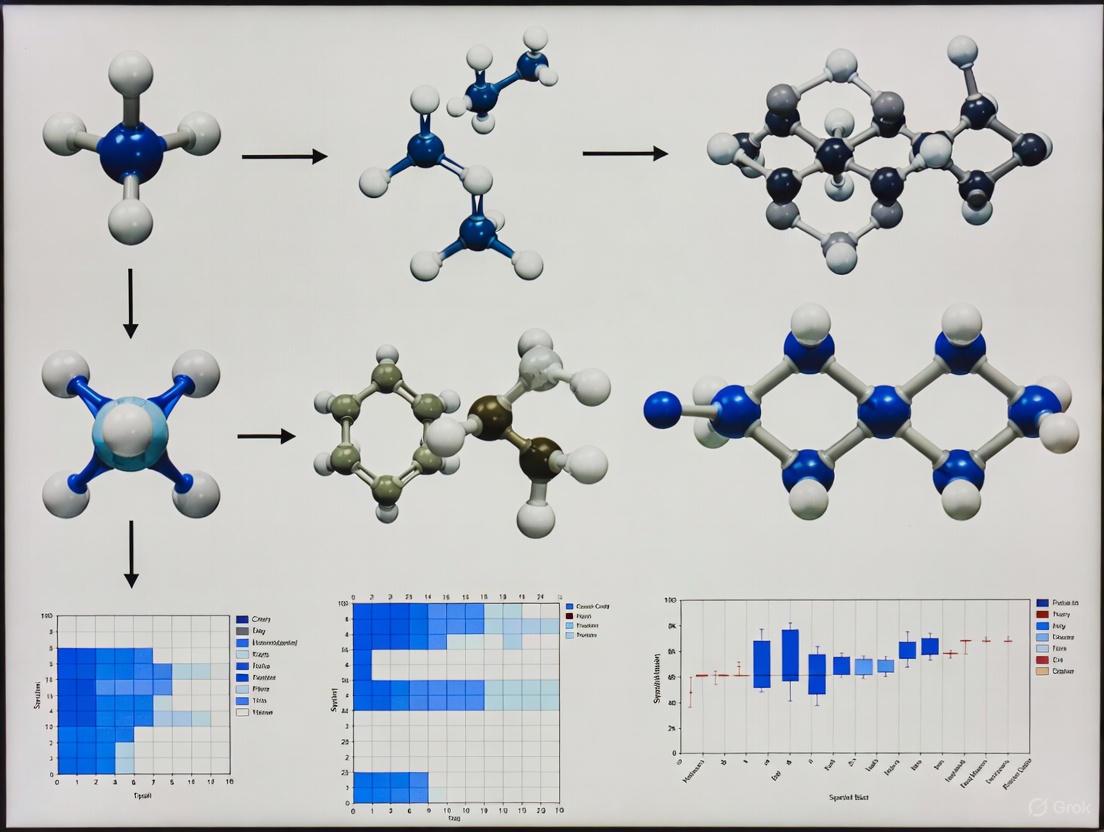

Visualization of Spatial Bias Concepts

Spatial Bias Identification Workflow

Spatial Bias Correction Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Spatial Bias Management

| Item | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Z-score Normalization | Corrects assay-specific spatial bias using median and MAD instead of mean and SD | More resistant to outliers than standard Z-score; applicable across multiple plates [1] |

| PMP Algorithms | Corrects plate-specific spatial bias using additive or multiplicative models | Requires pre-identification of bias type; effective for individual plate correction [1] |

| B-score Method | Traditional row/column effect correction using median polish | Well-established but may be insufficient for complex bias patterns [1] |

| Well Correction | Addresses location-specific biases in specific well positions | Useful for systematic well-specific errors [1] |

| Mann-Whitney U Test | Statistical test for identifying significant spatial patterns (α=0.01 or 0.05) | Detects significant differences between well groups (edge vs. interior) [1] |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test | Distribution comparison test for spatial bias detection | Identifies differences in measurement distributions across plate regions [1] |

| Heatmap Visualization | Graphical identification of spatial patterns | Essential for initial bias assessment and pattern recognition [1] |

| SPATA2 Framework | Comprehensive spatial transcriptomics analysis in R | Provides Spatial Gradient Screening algorithm for gradient detection [2] |

| LSGI Framework | Local Spatial Gradient Inference for transcriptomic data | Identifies spatial gradients in complex tissues without prior grouping [3] |

| GNE-555 | GNE-555, MF:C26H34N6O3, MW:478.59 | Chemical Reagent |

| Valeriandoid B | Valeriandoid B |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common sources of spatial bias in HTS? The most frequent sources are liquid handling errors, edge-well evaporation, and time-dependent effects (time drift) caused by factors like reagent evaporation, cell decay, pipette malfunctions, and variation in incubation times [1]. These issues often create systematic row or column effects, particularly on plate edges, leading to over or under-estimation of true signals [1].

How can I identify spatial bias that traditional quality control metrics miss? Traditional control-based metrics like Z-prime and SSMD can miss spatial artifacts affecting sample wells [4]. A complementary approach is to use the Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) metric, which evaluates deviations between observed and fitted dose-response values directly from drug-treated wells [4]. Plates with high NRFE values show significantly lower reproducibility among technical replicates [4].

My HTS data shows clear row and column effects. What correction methods are available? Robust statistical methods are essential for correction. The additive or multiplicative Platemodel Pattern (PMP) algorithm, used in conjunction with robust Z-scores, has been shown to effectively correct both assay-specific and plate-specific spatial biases [1]. The B-score method is another well-known plate-specific correction technique [1].

Does the type of plate I use influence spatial bias? Yes, the microtiter plate format itself can introduce bias. A major consideration is spatial bias due to discrepancies between center and edge wells, which can result in uneven stirring and temperature distribution [5]. This is particularly pronounced in applications like photoredox chemistry [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Liquid Handling Artifacts

- Symptoms: Striping patterns (clear column-wise or row-wise effects) in plate heat maps [4]. Irregular, non-sigmoidal dose-response curves [4].

- Root Causes: Pipette calibration errors, clogged tips, or inconsistencies in liquid dispensing systems [1].

- Solutions:

- Prevention: Implement a rigorous, regular calibration schedule for all liquid handlers. Use dye tests to verify dispensing accuracy and precision across the entire plate.

- Detection: Visually inspect plate heat maps for systematic column or row patterns. Use the NRFE metric to identify artifacts that control wells might not reveal [4].

- Correction: Apply plate-specific bias correction methods such as the B-score or the PMP algorithm [1].

Problem 2: Edge-Well Evaporation

- Symptoms: Strong edge effects, where outer wells show consistently higher or lower signals compared to the center of the plate [1]. This is often due to increased evaporation leading to higher compound concentrations [4].

- Root Causes: Uneven evaporation across the plate due to temperature gradients or inadequate humidity control during incubation [1] [5].

- Solutions:

- Prevention: Use plates with proper seals. Ensure environmental controls in incubators and storages are functioning correctly (maintain high humidity). Consider using specialized microplates designed to minimize evaporation.

- Detection: Plot the signal intensity versus well position to identify systematic differences between edge and interior wells.

- Correction: Apply spatial bias correction algorithms. In some cases, excluding the outermost ring of wells from analysis may be necessary.

Problem 3: Time Drift and Read-time Effects

- Symptoms: A gradual increase or decrease in signal strength correlated with the time a plate was read or processed [1]. This can appear as a gradient across the plate.

- Root Causes: Reader effects, reagent degradation, or cell decay during the time interval between processing the first and last well on a plate [1].

- Solutions:

- Prevention: Optimize assay protocols to minimize time between plate setup and reading. Allow for sufficient temperature equilibration before reading.

- Detection: Plot the measured signal against the time of reading for each well to identify temporal trends.

- Correction: Normalize data using robust statistical methods that account for time-dependent trends. The PMP algorithm can be configured to model and correct for such drift [1].

Quantitative Data on Bias Impact and Detection

Table 1: Impact of Spatial Bias on Hit Detection Rates (Simulation Data)

| Bias Correction Method | True Positive Rate (at 1% Hit Rate) | False Positives & Negatives (per assay) |

|---|---|---|

| No Correction | Low | High |

| B-score | Moderate | Moderate |

| Well Correction | Moderate | Moderate |

| PMP + Robust Z-score (α=0.05) | Highest | Lowest |

Source: Adapted from simulation study in Scientific Reports [1]

Table 2: NRFE Quality Tiers and Reproducibility Impact (Experimental Data)

| NRFE Quality Tier | NRFE Value | Impact on Technical Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| High Quality | < 10 | High reproducibility; recommended for reliable data |

| Borderline | 10 - 15 | Moderate reproducibility; requires additional scrutiny |

| Low Quality | > 15 | 3-fold lower reproducibility; exclude or carefully review |

Source: Analysis of >100,000 duplicate measurements from the PRISM study [4]

Experimental Protocols for Bias Identification

Protocol 1: Detecting Systematic Artifacts Using NRFE

This protocol uses the Normalized Residual Fit Error to identify spatial artifacts missed by traditional QC [4].

- Data Collection: Obtain raw dose-response measurements from your HTS run, ensuring plate layout information is available.

- Curve Fitting: Fit a dose-response model (e.g., a sigmoidal curve) to the data for each compound on the plate.

- Calculate Residuals: For each well, calculate the residual—the difference between the observed value and the fitted value from the curve.

- Compute NRFE: Normalize the residuals using a binomial scaling factor to account for response-dependent variance. The specific calculation is:

NRFE = (sum of squared normalized residuals / degrees of freedom)^0.5[4]. - Quality Assessment: Flag plates with an NRFE > 15 as low-quality and plates with NRFE between 10-15 as borderline, following the established tiers [4].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Between Additive and Multiplicative Bias

This methodology helps determine the correct model (additive or multiplicative) for applying the PMP correction algorithm [1].

- Plate Visualization: Create a heat map of the raw plate measurements to visually inspect the spatial pattern.

- Statistical Testing: Apply both the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test to the plate data.

- Model Selection: The results of these tests, using a significance threshold (e.g., α=0.01 or α=0.05), indicate whether the spatial bias present in the plate better fits an additive or a multiplicative model [1].

- Application of Correction: Apply the appropriate version of the PMP algorithm (additive or multiplicative) based on the statistical test results to normalize the plate data [1].

Quality Control Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for HTS Bias Mitigation

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| 384 or 1536-well Microtiter Plates | Standard platform for miniaturized HTS; spatial bias like edge effects must be monitored [1] [5]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotic systems for precise reagent dispensing; require regular calibration to prevent liquid handling artifacts [1]. |

| Plate Seals | Used to minimize evaporation in edge wells during incubation steps [4]. |

| Control Wells (Positive/Negative) | Essential for calculating traditional QC metrics (Z-prime, SSMD) to detect assay-wide failure [4]. |

| plateQC R Package | A specialized software tool that implements the NRFE metric and provides a robust toolset for detecting spatial artifacts [4]. |

| B-score & PMP Algorithms | Statistical methods implemented in software (e.g., R) for correcting identified plate-specific spatial biases [1]. |

| Chlorahololide D | Chlorahololide D |

| 1,4-Epidioxybisabola-2,10-dien-9-one | 1,4-Epidioxybisabola-2,10-dien-9-one, CAS:170380-69-5, MF:C15H22O3, MW:250.33 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

What is spatial bias and why is it a problem in my HTS data?

Spatial bias is a systematic error in high-throughput screening (HTS) data where specific well locations on a microtiter plate (e.g., on the edges or in specific rows/columns) show artificially increased or decreased signals. This is a major challenge because it can lead to both false positives (inactive compounds mistakenly identified as hits) and false negatives (active compounds that are missed), increasing the cost and time of drug discovery [6].

How can I quickly check my plates for spatial bias?

You can visualize your plate data using a heat map. Systematic patterns, such as a gradient of signal from one side of the plate to the other, or consistently high or low signals in the edge wells, are a clear indicator of spatial bias [6]. The diagram below illustrates the workflow for diagnosing and correcting this bias.

What's the difference between additive and multiplicative spatial bias?

The correction method you should use depends on the type of bias affecting your data [6].

| Bias Type | Mathematical Model | Description | Common Assay Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Bias | f(x) = µ + R<sub>i</sub> + C<sub>j</sub> + ε<sub>ij</sub> |

The systematic error is a fixed value added to or subtracted from the true signal. | Various HTS assays |

| Multiplicative Bias | f(x) = µ × R<sub>i</sub> × C<sub>j</sub> + ε<sub>ij</sub> |

The systematic error is a factor that multiplies the true signal. | High-Content Screening (HCS) [6] |

What statistical methods can I use to correct spatial bias?

The following table summarizes established methods for correcting spatial bias. Research shows that using a combination of plate-specific and assay-specific corrections yields the best results, with one method demonstrating superior performance in hit detection [6].

| Method | Scope of Correction | Principle | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive/Multiplicative PMP + Robust Z-Score [6] | Plate & Assay | Uses pattern recognition for plate-specific bias, then robust Z-scores for assay-wide correction. | Highest hit detection rate, lowest false positives/negatives [6]. |

| B-Score [6] | Plate | Uses two-way median polish to remove row and column effects. | A well-known plate-specific method. |

| Well Correction [6] | Assay | Corrects systematic error from specific well locations across all plates in an assay. | An effective assay-specific technique. |

| Interquartile Mean (IQM) Normalization [7] | Plate & Well | Normalizes plate data using the mean of the middle 50% of values; can also correct positional effects. | Effective for intuitive visualization and reducing plate-to-plate variation. |

Detailed Protocol: Correcting Spatial Bias Using the PMP and Robust Z-Score Method

This protocol is designed to correct both plate-specific and assay-specific spatial biases in a 384-well plate HTS setup, based on the method shown to be highly effective in simulation studies [6].

Plate-Specific Bias Correction

Objective: To identify and remove row and column effects from each individual plate.

- Step 1: Model Selection. Test whether the data on each plate fits an additive, multiplicative, or no-bias model. This can be done using statistical tests like the Mann-Whitney U test or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test to compare the distribution of signals in biased versus unbiased rows/columns [6].

- Step 2: Additive Bias Correction. If an additive model is identified, correct the measurement in row i and column j using the following model [6]:

>

x_ij(corrected) = (x_ij - R_i - C_j) / (1 + ε_ij)...whereR_iandC_jare the estimated biases for row i and column j, andε_ijis a small Gaussian noise term. - Step 3: Multiplicative Bias Correction. If a multiplicative model is identified, correct the data using the model [6]:

>

x_ij(corrected) = x_ij / (R_i * C_j) + ε_ij

Assay-Wide Bias Correction

Objective: To correct for systematic errors that persist in the same well location across all plates in the entire screening campaign.

- Step 4: Apply Robust Z-Score Normalization. For each well across all plates, calculate a robust Z-score using the median and the median absolute deviation (MAD) to minimize the influence of outliers [6]:

>

Z_robust = (x - median(X)) / MAD...whereXis the set of all measurements in the same well position across the assay.

Hit Identification

- Step 5: Select Hits. After correction, compounds can be selected as hits if their robust Z-score exceeds a predefined threshold (e.g.,

μ_p - 3σ_pfor inhibitors, whereμ_pandσ_pare the mean and standard deviation of the corrected measurements on platep) [6].

How much can bias correction improve my hit discovery?

Simulation studies comparing different methods demonstrate that comprehensive correction significantly improves outcomes. The following table summarizes the performance of various methods when the hit rate was 1% and bias magnitude was 1.8 standard deviations [6].

| Correction Method | True Positive Rate (Approx.) | Total False Positives & Negatives (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| No Correction | 40% | 165 |

| B-Score | 65% | 90 |

| Well Correction | 72% | 75 |

| PMP + Robust Z-Score (α=0.05) | ~87% | ~40 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful HTS and spatial bias correction rely on specific materials and tools. The table below lists essential items for setting up and analyzing a pyruvate kinase qHTS experiment, a model system for evaluating HTS performance [8].

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Pyruvate Kinase (PK) Enzyme | The well-characterized biological target used in the model qHTS assay to identify activators and inhibitors [8]. |

| Luciferase-based Coupled Assay | Indirectly measures PK-generated ATP via luminescence, allowing detection of both inhibitors and activators in a homogenous format [8]. |

| Ribose-5-Phosphate (R5P) | A known allosteric activator of PK; used as a positive control for activation on every screening plate [8]. |

| Luteolin | A flavonoid identified as a PK inhibitor; used as a positive control for inhibition on every screening plate [8]. |

| Compound Library (e.g., 60,000+ compounds) | The collection of small molecules screened against the target to discover novel modulators [8]. |

| 1536-Well Plates | The miniaturized assay format essential for high-throughput screening, allowing thousands of compounds to be tested in a single experiment [8]. |

| Euptox A | Euptox A, CAS:79491-71-7, MF:C15H20O2, MW:232.32 g/mol |

| Tsugafolin | Tsugafolin |For Research Use |

FAQs

Bias can arise from many physical and technical factors in the screening process [6]:

- Reagent evaporation from edge wells.

- Cell decay over the time it takes to read a plate.

- Liquid handling errors or pipette malfunctions.

- Variation in incubation time for different wells or plates.

- Reader effects from the detector itself.

Can I use a simple normalization method for a quick check?

Yes, for a rapid assessment and normalization, the Interquartile Mean (IQM) method is effective and intuitive [7].

- For each plate, order all data points by ascending value.

- Calculate the mean of the middle 50% of these ordered values (the interquartile mean).

- Normalize all data on the plate by this IQM to reduce plate-to-plate variation.

- To correct positional bias, you can calculate the IQM for each specific well position across all plates (IQMW) and use it for a second level of normalization [7].

My hit rate seems low and my actives are clustered on the plate. What should I do?

This is a classic sign of spatial bias. You should [6]:

- Immediately stop and validate your current "hit" list.

- Re-inspect the raw data from your screening run using plate heat maps to confirm the spatial pattern.

- Apply a rigorous bias correction method (like the PMP protocol above) to your entire dataset.

- Re-select your hits from the corrected data. This should de-prioritize clustered false positives and reveal previously masked false negatives.

FAQs: Understanding Spatial Bias

What is the fundamental difference between assay-specific and plate-specific bias?

Assay-specific bias is a systematic error that consistently appears across all plates within a given high-throughput screening (HTS) or high-content screening (HCS) experiment. In contrast, plate-specific bias is a systematic error that appears only on a single, individual plate within an assay [1]. Correcting for both is critical for selecting quality hits [1].

What are the common causes of these biases in HTE plates?

Spatial bias arises from various procedural and environmental sources. These include reagent evaporation, cell decay, pipetting errors, liquid handling malfunctions, incubation time variation, time drift during measurement, and reader effects [1]. These factors often manifest as row or column effects, particularly on plate edges [1].

How can I visually distinguish between an additive and multiplicative bias pattern?

There is a key methodological difference. Statistical tests, such as the Mann-Whitney U test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test, are required to formally determine whether the bias fits an additive or multiplicative model [1]. Visually, both can create similar row/column patterns, but multiplicative bias scales with the underlying signal intensity.

Why is correctly identifying the bias type crucial for data correction?

Using an incorrect model for bias correction can increase error rates. Methods designed for additive bias, like the standard B-score, are ineffective against multiplicative bias [9]. Applying a multiplicative correction (e.g., PMP algorithm) to data with additive bias, or vice-versa, can lead to a higher number of false positives and false negatives during hit identification [9] [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Type of Spatial Bias

Follow this workflow to systematically identify the nature of spatial bias in your dataset.

Steps:

Visual Inspection & Pattern Recognition:

- Action: Plot the raw measurement data for all plates in the assay, ideally as heatmaps or surface plots.

- Assay-Specific Bias: Look for a consistent spatial pattern (e.g., a gradient from left-to-right or top-to-bottom) that is present across the majority of plates [1].

- Plate-Specific Bias: Look for strong spatial patterns that appear in one or a few plates but are absent in others [1].

- No Bias: Data appears randomly distributed across the well locations with no discernible systematic pattern.

Statistical Confirmation:

- Action: Use statistical tests to formally determine if the bias is additive or multiplicative. Research indicates that the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sample test can be used for this purpose [1].

- Interpretation: The tests help select the appropriate correction model (additive or multiplicative) for the subsequent bias removal step [1].

Guide 2: Implementing a Bias Correction Protocol

This protocol integrates methods for removing both assay-specific and plate-specific biases, which can be either additive or multiplicative [9] [1].

Detailed Methodology:

Step 1: Correct for Plate-Specific Bias

- For Additive Bias: Apply the B-score method, which uses a two-way median polish to remove row and column effects [1] [10].

- For Multiplicative Bias: Apply a multiplicative model, such as the PMP (Polished Mean Plate) algorithm designed for this bias type. This method effectively corrects for systematic errors that scale with the signal [9] [1].

Step 2: Correct for Assay-Specific Bias

- Action: Apply Robust Z-score normalization to the plate-corrected data. This step removes systematic error from biased well locations that are consistent across the entire assay, standardizing the data for final analysis [1].

Step 3: Validate Corrected Data

- Action: Re-inspect the corrected plate maps to ensure spatial patterns are removed. Recalculate assay quality metrics like the Z'-factor [11]. A successful correction should yield data that is ready for robust hit identification using thresholds like μp - 3σp (mean of plate minus three standard deviations) [1].

Performance Data & Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of different bias correction methods from simulation studies, demonstrating the importance of using the correct approach.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bias Correction Methods in HTS [1]

| Correction Method | Handles Multiplicative Bias? | Average True Positive Rate (at 1% Hit Rate) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction | No | Lowest | Serves as a baseline; highlights need for correction. |

| B-score (Additive) | No | Low | Industry standard for additive, plate-specific bias [10]. |

| Well Correction | No | Moderate | Effective for assay-specific bias. |

| Additive/Multiplicative PMP + Robust Z-score | Yes | Highest | Integrates plate and assay-specific correction; flexible for bias type. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Z-score | A normalization technique that minimizes the impact of outliers, used for assay-specific bias correction. | Critical step for standardizing data across an entire screening campaign after plate-specific effects are removed [1]. |

| B-score Algorithm | A statistical method using two-way median polish to remove additive row and column effects from individual plates. | The industry standard for correcting additive, plate-specific spatial bias [1] [10]. |

| PMP (Polished Mean Plate) Algorithm | A method designed to detect and remove multiplicative spatial bias from screening plates. | Essential when systematic error is not additive but scales with the underlying signal intensity [9] [1]. |

| AssayCorrector (R package) | An implemented program for detecting and removing multiplicative spatial bias. | Available on CRAN, providing a practical tool for researchers to apply the PMP methodology [9]. |

| Z'-factor | A key metric for assessing the quality and robustness of an HTS assay by comparing the separation between positive and negative controls. | Used to validate assay performance before and after bias correction [11]. |

| Methyl 4-O-feruloylquinate | Methyl 4-O-feruloylquinate, CAS:195723-10-5, MF:C18H22O9, MW:382.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Borapetoside E | Borapetoside E, MF:C27H36O11, MW:536.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Definitions and Core Concepts

What are additive and multiplicative biases in the context of HTS? In high-throughput screening (HTS), spatial bias refers to systematic errors that consistently distort measurements across multiwell plates. Additive and multiplicative biases describe two fundamental ways this distortion occurs.

- Additive Bias: A constant value is added to or subtracted from the true measurement, independent of the signal's magnitude. It represents an absolute error. The correction involves subtracting the estimated bias amount [12] [13].

- Multiplicative Bias: The true measurement is multiplied by a factor, meaning the error is proportional to the signal's strength. It represents a relative error. The correction involves dividing by the estimated bias factor [12] [13].

The mathematical relationship is often expressed as:

- Additive Model: ( y = x + c )

- Multiplicative Model: ( y = m \times x ) ...where ( x ) is the true value, ( y ) is the measured value, and ( c ) and ( m ) are the additive and multiplicative biases, respectively [13].

Identification and Diagnosis

How can I identify which type of bias is affecting my assay? Diagnosing the type of spatial bias is a critical first step. The table below outlines the characteristic patterns and recommended diagnostic tests.

Table 1: Diagnostic Patterns for Additive vs. Multiplicative Bias

| Feature | Additive Bias | Multiplicative Bias |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Pattern | Consistent over- or under-estimation in specific rows/columns, often plate edges [6]. | Signal strength varies proportionally across the plate [6]. |

| Effect on Signal | Constant absolute error, regardless of true signal intensity [12]. | Error scales with true signal intensity; higher signals have larger absolute errors [12]. |

| Visual Clue on Plots | A constant gap between expected and observed measurements over time [13]. | A widening or narrowing gap between expected and observed measurements as values change [13]. |

| Recommended Test | Mann-Whitney U test or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on plate rows/columns [6]. | Statistical tests for interaction effects at row-column intersections [14]. |

Correction Methodologies

What are the standard protocols for correcting these biases? Correction methods must be matched to the identified bias type. The following workflows are established for HTS data analysis.

Protocol for Additive Bias Correction

- Spatial Trend Identification: Fit a two-way (row-column) median polish or robust regression model to the plate measurements to estimate the background spatial trend [6].

- B-Score Calculation (Traditional Method): For each well, calculate the residual after removing the row and column median effects. Normalize these residuals by the plate's median absolute deviation (MAD) [6]. The formula is: ( B_{score} = \frac{{Residual}}{{MAD}} )

- Additive PMP Algorithm (Advanced Method): Apply a parametric model that estimates an additive effect for each biased row and column. The measured value ( y{ij} ) in row *i* and column *j* is modeled as: ( y{ij} = μ + Ri + Cj + ε{ij} ) ...where ( μ ) is the plate mean, ( Ri ) is the row effect, ( Cj ) is the column effect, and ( ε{ij} ) is random noise [6] [14].

- Validation: After correction, the plate should exhibit no significant spatial pattern in the residuals when tested with the Mann-Whitney U or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (at a significance threshold of α=0.01 or α=0.05) [6].

Protocol for Multiplicative Bias Correction

- Model Specification: Use a model that accounts for multiplicative interactions. The measured value can be modeled as: ( y{ij} = μ \times Ri \times Cj + ε{ij} ) ...where the effects multiply rather than add [6] [14].

- Logarithmic Transformation (Optional): Transform the data using a log transformation, which converts multiplicative effects into additive ones. The standard additive correction protocol can then be applied, followed by an exponential transformation to convert data back to the original scale.

- Multiplicative PMP Algorithm: Directly apply a multiplicative parametric model to estimate the scaling factors for affected rows and columns [6].

- Re-normalization: Apply a post-correction normalization, such as robust Z-scores, to ensure data quality and comparability across plates [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Bias Correction Methods in HTS Simulation

| Correction Method | True Positive Rate (at 1% Hit Rate) | False Positives & Negatives (per Assay) | Key Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Correction | Low | High | - |

| B-Score (Additive) | Moderate | Moderate | Purely additive spatial effects [6]. |

| Well Correction | Moderate | Moderate | Assay-specific biased well locations [6]. |

| PMP + Robust Z-Score | Highest | Lowest | Can handle both additive and multiplicative biases [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can my assay be affected by both additive and multiplicative biases simultaneously? Yes, real-world HTS data can be complex. A linear model that combines both effects (( y = mx + c )) is often the most robust approach for correction, as it can capture biases that have both additive and multiplicative components [13]. The AssayCorrector program, available in CRAN, implements models that account for such interactions [14].

Q2: What are the most common sources of these biases in the lab? Additive bias is often linked to background fluorescence or reader effects. Multiplicative bias frequently stems from systematic issues like reagent evaporation, pipetting inaccuracies in stock solution volumes, or cell decay over the plate processing time [6].

Q3: After correction, how do I validate that the bias has been successfully removed? Validation should include both spatial and statistical checks:

- Visual Inspection: Generate a heatmap of the corrected plate data. The spatial pattern (e.g., edge effects) should be eliminated.

- Statistical Testing: Re-run the Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests on the corrected data. The tests should no longer be significant at your chosen threshold (e.g., α=0.05), indicating no detectable spatial structure remains [6].

- Hit List Comparison: Compare the hit list from the corrected data with one from uncorrected data. A well-corrected assay should show a reduction in hits clustered in biased regions [6].

Q4: Are there field-specific considerations for different HTS technologies? Yes, the dominant bias type can vary by technology. Homogeneous assays may be more prone to additive biases from plate reader effects, while cell-based assays (high-content screening) are often more affected by multiplicative biases from cell seeding inconsistencies [6] [14]. It is crucial to analyze historical data from each specific technology platform in your lab to understand its typical bias profile.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Spatial Bias Analysis and Correction

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Bias Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| AssayCorrector (R package) | Implements novel additive and multiplicative spatial bias models for various HTS technologies [14]. | Primary software for advanced bias detection and correction. |

| Robust Z-Score Normalization | A statistical method using median and MAD, resistant to outliers [6]. | Post-correction normalization to improve data quality and hit selection. |

| B-Score Scripts | Traditional scripts for median polish and residual normalization [6]. | Standard additive bias correction. |

| ImageJ | Free software for image analysis and quantification [15]. | Essential for analyzing high-content screening (HCS) data. |

| ChemBank Database | Public database of small-molecule screens providing experimental data for analysis [6]. | Source of real HTS data for testing and validating correction methods. |

Spatial Bias Correction Methods: From B-Score to Advanced Algorithms

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is spatial bias in High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and why is it a problem? Spatial bias is a systematic error that negatively impacts experimental high-throughput screens. Its sources include reagent evaporation, cell decay, liquid handling errors, pipette malfunction, and variation in incubation times [1]. This bias often manifests as row or column effects, particularly on the edges of microtiter plates, leading to over-estimation or under-estimation of true signals [1]. If not corrected, spatial bias increases false positive and false negative rates during hit identification, which lengthens and increases the cost of the drug discovery process [1].

Q2: How do I know if my HTS data is affected by spatial bias? Spatial bias can be both assay-specific (a consistent bias pattern across all plates in a given assay) and plate-specific (a unique bias pattern on an individual plate) [1]. Visually inspecting raw data heatmaps for each plate is a good first step. Look for clear patterns, such as intensity gradients from one side of the plate to another, or specific rows/columns that consistently show higher or lower signals than the plate median.

Q3: What is the fundamental difference between the B-score and Well Correction techniques? The core difference lies in their approach and scope:

- B-score is primarily a plate-specific correction method. It removes row and column effects within individual plates to isolate compound-specific effects [1].

- Well Correction is an assay-specific correction technique. It removes systematic error from biased well locations by using data from the entire assay to normalize specific well positions [1].

Q4: When should I use B-score over Well Correction, and vice versa? The choice depends on the nature of the bias in your experiment.

- Use B-score when spatial bias manifests as strong row and column effects within individual plates. It is highly effective for correcting plate-specific patterns like those caused by edge effects [1].

- Use Well Correction when certain well locations (e.g., specific coordinates like A1, B1, etc.) are consistently biased across all plates in an entire assay. This is suitable for systematic errors stemming from a fixed source, such as a consistently malfunctioning pipette tip [1].

- For comprehensive correction, a combined approach can be used. Research indicates that applying a plate-specific method (like an additive/multiplicative model) followed by an assay-specific method (like robust Z-scores) yields the highest hit detection rate and the lowest false positive and false negative count [1].

Q5: What are the limitations of these correction methods? No method is perfect. Over-correction is a potential risk, which can remove genuine biological signals along with the noise. The B-score assumes that the majority of compounds in a row or column are inactive, and its performance can degrade if this assumption is violated. Well Correction relies on having a sufficient number of plates in an assay to reliably estimate the baseline for each well location. Ultimately, corrected data should always be validated with follow-up experiments.

Detailed Methodologies

B-Score Correction Protocol [1]

The B-score is a robust statistical method for normalizing plate data based on median polish. The workflow involves the following steps:

Model the Data: For each plate, the measured value of a compound in row i and column j is modeled as:

- Additive Model: ( Y{ij} = μ + Ri + Cj + ε{ij} )

- Multiplicative Model: ( Y{ij} = μ * Ri * Cj + ε{ij} ) Where ( μ ) is the plate mean, ( Ri ) is the row effect, ( Cj ) is the column effect, and ( ε_{ij} ) is the residual error.

Apply Median Polish: This iterative process robustly estimates the row (( Ri )) and column (( Cj )) effects by successively subtracting row and column medians from the data matrix until the changes become negligible.

Calculate Residuals: The residual for each well is calculated as ( ε{ij} = Y{ij} - (μ + Ri + Cj) ) for the additive model.

Normalize Residuals: The B-score is computed by normalizing the residuals using a robust measure of dispersion, the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD).

- ( \text{B-score}{ij} = ε{ij} / ( \text{MAD} * \text{constant} ) ) Where the constant is typically 1.4826, making MAD a consistent estimator for the standard deviation of a normal distribution.

Well Correction Normalization Protocol [1]

Well Correction addresses systematic errors that are consistent for specific well locations across an entire assay.

Compile Well Location Data: For each specific well location (e.g., all wells at position A1 across all plates in the assay), gather all the measurement values.

Calculate Assay-Specific Statistics: Compute the median (( \tilde{M}_{loc} )) and MAD for the distribution of values at each specific well location.

Normalize Each Well: Apply a robust Z-score normalization to each measurement based on its well location's statistics.

- ( \text{Well-Corrected Score}{ij} = ( Y{ij} - \tilde{M}{loc} ) / ( \text{MAD}{loc} * \text{constant} ) ) This process centers and scales the data for each well position across the assay, removing the location-specific bias.

Comparison of Techniques and Performance

The table below summarizes the properties of B-score and Well Correction based on an analysis of experimental small molecule assays from the ChemBank database [1].

| Feature | B-Score | Well Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | Plate-specific correction [1] | Assay-specific correction [1] |

| Bias Model | Additive or Multiplicative [1] | Additive |

| Core Function | Removes row and column effects via median polish [1] | Normalizes specific well locations using data from all plates [1] |

| Key Statistical Measures | Plate median, Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) [1] | Assay-wide median and MAD for each well location [1] |

| Hit Selection Threshold | μp - 3σp (per plate) is common post-correction [1] | μp - 3σp (per plate) is common post-correction [1] |

Simulated Performance Data [1] A simulation study compared the hit detection performance of different methods on synthetic HTS data with known hits and bias rates. The results demonstrated the superiority of a combined approach that addresses both plate and assay-specific biases.

| Correction Method | True Positive Rate (Example) | False Positive/Negative Count (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| No Correction | Low | High |

| B-Score Only | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Well Correction Only | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| PMP + Robust Z-scores (Combined) | Highest | Lowest |

Note: The simulated data assumed 384-well plates, a fixed bias magnitude of 1.8 SD, and a hit percentage ranging from 0.5% to 5% [1]. The combined method (PMP for plate-specific bias and robust Z-scores for assay-specific bias) outperformed both B-score and Well Correction individually [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The table below lists key resources used in typical HTS campaigns where spatial bias correction is critical.

| Item | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (96, 384, 1536-well) | The miniaturized platform for conducting thousands of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological experiments in parallel [1]. |

| Chemical Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules, siRNAs, or shRNAs screened against biological targets to discover potential drug candidates (hits) [1]. |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Robotic and automated systems for precise reagent addition and compound transfer, a common source of spatial bias if malfunctioning [1]. |

| Target Biological Reagents | Purified enzymes, cell lines, or other biological materials representing the disease target used to assay compound activity. |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorescent, luminescent, or colorimetric probes used to quantify the biological response or interaction being measured. |

| Arabinan polysaccharides from Sugar beet | Arabinan polysaccharides from Sugar beet, MF:C23H38NO19Na |

| cis-9,10-Epoxy-(Z)-6-henicosene | cis-9,10-Epoxy-(Z)-6-henicosene|CAS 105016-20-4 |

Systematic spatial errors, such as gradient vectors and periodic row/column bias, are common challenges in High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) plates. These distortions, arising from variations in robotic handling, instrumentation, and environmental conditions, can significantly reduce data quality and hinder hit identification in critical areas like drug screening [16]. The 5x5 Hybrid Median Filter (HMF) is a nonparametric local background estimation tool designed to mitigate these specific types of intraplate systematic error, thereby improving dynamic range and statistical confidence in your experimental results [16].

What is the difference between a standard median filter and a hybrid median filter?

A standard median filter for a 5x5 kernel works by taking all 25 values in the 5x5 window, ranking them, and selecting the middle value. In contrast, the 5x5 Hybrid Median Filter (HMF) is a more sophisticated operator that first separates the pixels in its kernel into distinct components—typically a cross-shaped pattern and a diagonal or rectangular pattern [16]. It then calculates the median for each component independently. The final output value is the median of these component medians. This multi-step process makes the HMF particularly effective at preserving sharp edges and corners while removing noise and correcting for spatial background distortions, a common requirement in HTE plate analysis [16].

Troubleshooting Common HMF Implementation Issues

FAQ: My background correction appears insufficient, and some spatial bias remains after applying the standard 5x5 HMF. What should I do?

The standard 5x5 HMF is highly effective against gradient vectors but may not fully correct strong periodic patterns like row or column bias [16].

- Problem Identification: Profile your raw MTP data using regional statistics to classify the specific error type. Is it a continuous gradient, a distinct row/column pattern, or a combination of both? [16]

- Solution: Alternative Filter Kernels: For pronounced row-wise or column-wise periodic errors, consider applying a dedicated 1x7 Median Filter (MF) or a Row/Column 5x5 HMF (RC 5x5 HMF) specifically designed for these patterns [16].

- Advanced Workflow: Serial Filtering: For complex error patterns involving multiple distortion types, apply corrective filters in a serial workflow. First, use a 1x7 MF to remove row/column bias, then apply the standard 5x5 HMF to correct any remaining gradient vectors. This progressive correction can significantly improve dynamic range and reduce background variation [16].

FAQ: How should I handle plates with control wells that have extreme values, as the HMF is distorting them?

Control wells, such as positive controls with inherently high signals, can be perceived as outliers and improperly corrected if included in the standard HMF background calculation [16].

- Solution: Modified HMF Kernel: Implement a special HMF kernel for regions containing control wells. This kernel should be constructed to exclude elements belonging to the control group when estimating the background. For example, in the STD 5x5 HMF layout, the median of the cross-elements can be replaced by the median of the elements not belonging to the center, diagonal, or cross in the kernel [16].

- Implementation: Segment your plate data. Apply the standard 5x5 HMF to compound and negative control wells, while applying the modified HMF kernel to positive control wells to ensure their values are not skewed by the filter [16].

FAQ: The perturbations in my corrected data are too easily detectable. How can I improve their imperceptibility?

Enhancing the imperceptibility of corrections, a concept supported by research in adversarial example generation, involves smoothing out obvious noise while preserving the underlying data structure [17].

- Solution: Post-Processing Smoothing: Apply a median filter specifically to the generated perturbations or the corrected data array. The median filter is a nonlinear filter that effectively eliminates high-frequency noise while preserving edge information, leading to a result that more closely resembles the original, unbiased data structure without compromising the corrective action [17].

- Technical Parameters: As implemented in image processing, a median filter smoothes noise by calculating the median value within a sliding window (e.g., 3x3 or 5x5 kernel) centered at each pixel position. A larger kernel results in stronger smoothing but may cost some detail [18]. The

MLMAD(Median Of Least Median Absolute Deviation) method can provide an even stronger smoothing effect by accounting for pixel deviation from the median, which helps flatten areas according to the kernel size [18].

Experimental Protocols for HMF Application

Protocol 1: Correcting a Primary Screen with Gradient Vector Errors

This protocol is based on the successful application of a 5x5 HMF to a 236,441-compound primary screen for hepatic lipid droplet formation conducted in a 384-well format [16].

1. Objective: To mitigate systematic spatial distortions (gradient vectors) in a high-content imaging screen and improve the assay dynamic range and hit confirmation rate [16].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: Hepatocytes.

- Stains: BODIPY 493/503 (lipid dye) and DAPI (nuclear dye), both from Invitrogen [16].

- Instrumentation: Opera QEHS high-throughput imaging system (PerkinElmer) with a 20x 0.45NA air objective [16].

- Software: CyteSeer (Vala Sciences) for image analysis with the "Lipid Droplets" algorithm; CBIS (Cheminnovation) for data deposition and initial normalization; Spotfire (TIBCO) for statistical evaluation; Matlab (The Mathworks) for customized batch HMF processing [16].

3. Workflow:

4. Key Data Analysis: The HMF correction's effectiveness is measured by the reduction in background signal variation and the subsequent improvement in screening statistics.

Table 1: Performance Metrics Before and After HMF Correction in a Primary Screen [16]

| Metric | Uncorrected Data | HMF Corrected Data | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound % Inhibition (SD) | 9.33 (25.25) | -1.15 (16.67) | Reduced background signal & variability |

| Negative Control (SD) | 0 (13.79) | 0 (9.65) | Tighter control distribution |

| Z' Factor | 0.43 | 0.54 | Enhanced assay quality rating |

| Z Factor | -0.01 | 0.34 | Moved from "no room for hit selection" to feasible |

Protocol 2: Designing and Applying Custom Filters for Periodic Error

This protocol addresses systematic errors that the standard 5x5 HMF cannot properly correct, such as striping or quadrant patterns [16].

1. Objective: To design and apply ad hoc median filter kernels (1x7 MF and RC 5x5 HMF) to reduce periodic error patterns in simulated or experimental MTP data arrays [16].

2. Materials:

- Software: A computational environment capable of array mathematics and custom median filter implementation (e.g., Matlab, Python with NumPy/SciPy) [16].

- Data: Simulated MTP data arrays with introduced periodic error for validation [16].

3. Workflow:

4. Filter Design Specifications:

- 1x7 Median Filter (MF): Targets strong row-wise periodic bias. The kernel samples 7 wells in a single row, and the correction value is derived from the simple median of this list [16].

- Row/Column 5x5 HMF (RC 5x5 HMF): Targets both row and column bias simultaneously. The kernel and its component selection are optimized for this specific pattern [16].

- Correction Calculation: For each well

n, the corrected valueCnis calculated asCn = (G / Mh) * n, whereGis the global median of the entire MTP dataset, andMhis the hybrid median (or median) derived from the filter's component medians [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Software for HMF-Based Spatial Bias Correction

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BODIPY 493/503 | Fluorescent dye for visualizing lipid droplets in cell-based assays [16]. | Invitrogen; excitation/emission ~493/503 nm. |

| DAPI | Fluorescent nuclear stain for cell counting and normalization in high-content screening [16]. | Invitrogen; excitation/emission ~358/461 nm. |

| Opera QEHS System | High-throughput, high-content confocal imager for cell-based assays in microtiter plates [16]. | PerkinElmer; typically used with 20x to 63x objectives. |

| CyteSeer Software | Image analysis software for extracting quantitative features from cellular images [16]. | Vala Sciences; uses "Lipid Droplets" algorithm. |

| STD 5x5 HMF Algorithm | Core algorithm for background estimation and correction of gradient-type spatial errors [16]. | Custom implementation in Matlab or Python. |

| 1x7 MF / RC 5x5 HMF | Specialized filter kernels for correcting periodic row/column bias not fully addressed by the standard HMF [16]. | Applied serially or individually based on error pattern. |

| Median Filter (for Smoothing) | A nonlinear filter used to smooth out high-frequency noise in corrected data, enhancing imperceptibility [17] [18]. | Kernel size (3x3, 5x5) and type (Median, MLMAD) are key parameters [18]. |

| Telacebec | Telacebec, CAS:1334719-95-7, MF:C29H28ClF3N4O2, MW:557.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anilazine | Anilazine | Anilazine analytical standard for research. A triazine fungicide for lab use. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

In High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) plates research, spatial bias presents a significant challenge for data accuracy and reliability. This technical support center provides methodologies for identifying and correcting complex spatial bias patterns, specifically row/column effects and localized artifacts, using specialized median filter kernels. The following guides and protocols will equip researchers with practical tools to enhance data quality in drug discovery and development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is spatial bias in HTE plates and why is it a problem? Spatial bias refers to systematic errors that cause measurements from specific locations on an HTE plate (such as certain rows, columns, or edges) to be consistently higher or lower than their true values. This bias arises from sources including reagent evaporation, liquid handling errors, plate reader effects, and cell decay [6]. It increases false positive and false negative rates during hit identification, compromising data quality and potentially leading to costly errors in the drug discovery pipeline [6].

How can a 1x7 median filter kernel correct row-specific bias? A 1x7 median filter kernel is specifically designed to address row-wise artifacts. This horizontal kernel operates by sliding across each row of your data, examining a window of 7 adjacent wells. For each position, it replaces the center well's value with the median of the seven values in the window [19]. This process effectively smooths out sudden, anomalous spikes or dips within a row while preserving genuine edge responses and step changes that span multiple wells. It is particularly effective against "streaking" defects that manifest along specific rows.

When should I use a 7x1 column filter instead of a row filter? A 7x1 vertical median filter kernel should be deployed when you observe column-specific artifacts in your plate data. These often result from systematic errors in liquid handling across a column or from time-drift effects during reading [6]. The filter operates similarly to the row filter but processes data vertically, replacing each well value with the median of its value and the six immediately above and below it in the same column. This preserves row-based patterns while eliminating column-specific noise.

What are the limitations of median filtering for spatial bias correction? Median filtering is highly effective for impulse noise (e.g., single-well dropouts or spikes) but has limitations. It can suppress fine-scale, genuine biological signals if the kernel width is too large relative to the signal features. Furthermore, it requires careful handling of plate boundaries; at the edges of the plate, there are not enough neighboring wells to fill the kernel, which can be addressed by methods like zero-padding, boundary value repetition, or window shrinking [19]. It is also less effective for correcting smoothly varying, large-scale background gradients.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Persistent Edge Effects After Standard Filtering

Symptoms: The first and last rows and/or columns of the plate continue to show systematically biased measurements even after applying a standard 3x3 median filter.

Solution: Apply a Combined Asymmetric Filtering Strategy

- Diagnose the Pattern: First, visualize your plate data using a heatmap to confirm that the bias is predominantly on the top/bottom edges (rows) or left/right edges (columns).

- Apply Directional Filters:

- For strong row-edge effects, apply a 1x7 median filter. This will specifically target noise patterns running horizontally across the plate [19].

- For strong column-edge effects, apply a 7x1 median filter to address vertical patterns.

- Sequential Processing: If both row and column edge effects are present, apply the 1x7 and 7x1 filters sequentially. The order can be tested on a representative plate to see which yields the best result.

- Validate: Compare the distribution of a control compound across the plate before and after correction. The p-value from a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test between edge and interior well intensities should increase, indicating no significant spatial bias remains [6].

Problem 2: Differentiating True Hits from Spatial Bias

Symptoms: Putative "hit" wells are clustered in specific spatial patterns, making it difficult to determine if they represent genuine biological activity or are artifacts of spatial bias.

Solution: Implement a Multi-Step Normalization and Filtering Protocol

- Plate-Specific Bias Correction: First, correct for plate-wide spatial trends using an established method like the B-score or the Additive/Multiplicative PMP (Plate Model Pattern) algorithm. The PMP algorithm is particularly effective as it can handle both additive and multiplicative bias models commonly found in HTS data [6].

- Residual Noise Removal: Apply a 1x7 or 7x1 median filter to the corrected data from step 1. This will remove any residual, high-frequency impulse noise that the plate-level correction might have missed [19].

- Hit Selection: Finally, calculate robust Z-scores for the filtered and corrected data. Select hits based on a statistically derived threshold (e.g., μp - 3σp for each plate 'p') [6]. This integrated approach significantly improves the true positive rate and reduces false positives compared to using any single method alone.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting Row/Column Bias with 1x7 and 7x1 Median Filters

Purpose: To eliminate row-wise or column-wise spatial bias from HTE plate data using directional median filters.

Materials:

- Raw numerical data from an HTE plate (e.g., 96, 384, or 1536-well format)

- Computational environment (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy, R, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Data Import: Load the plate data into a 2D matrix in your computational environment.

- Boundary Handling Selection: Choose a method for handling the top and bottom three rows (for 7x1) or left and right three columns (for 1x7) where a full kernel cannot be applied. A recommended approach is boundary value repetition, where the first and last valid values are repeated to create virtual wells that pad the boundary [19].

- Kernel Application:

- For row-wise correction, traverse each row of the matrix. For each well, consider a 1x7 window centered on it. Replace the center value with the median of the seven values in the window.

- For column-wise correction, traverse each column. For each well, consider a 7x1 window and replace the center value with the median.

- Output: The resulting matrix is the bias-corrected plate data.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Integrated Workflow for Multiplicative Spatial Bias

Purpose: To correct for complex spatial bias that follows a multiplicative model, which is common in assays affected by signal-dependent artifacts.

Materials:

- Raw HTE plate data

- Software capable of implementing PMP algorithms and median filtering (e.g., R, Python with custom scripts)

Procedure:

- Bias Model Identification: Test the plate data to determine if the spatial bias is additive or multiplicative. This can be done by visually inspecting the relationship between the mean and variance of signals across the plate, or by fitting both models and selecting the better-fitting one [6].

- Apply Multiplicative PMP Correction: Use the Multiplicative PMP algorithm to model and remove the plate-specific spatial trend. This involves estimating a smooth bias field that is multiplied by the underlying true signal [6].

- Apply Median Filter: Pass the PMP-corrected data through a 1x7 or 7x1 median filter (as dictated by the residual noise pattern) to remove any remaining salt-and-pepper noise [19].

- Normalize Data: Calculate robust Z-scores for the final corrected data to standardize values across different plates and assays [6].

- Hit Calling: Identify hits based on a predefined threshold applied to the normalized scores (e.g., Z-score < -3 or > 3).

Integrated Correction Workflow:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Different Median Filter Kernels on Synthetic HTS Data

This table compares the efficacy of various filter kernels in correcting spatial bias, using a simulation where true hits (~1%) were introduced into an HTS dataset with a known bias magnitude of 1.8 SD. Performance is measured by the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the total count of false results (False Positives + False Negatives). Data was generated based on the simulation methodology described in [6].

| Filter Kernel Size | Bias Model Corrected | Average True Positive Rate (%) | Average Total False Hits Per Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Filter | Multiplicative | 52.1 | 185 |

| 3x3 Median | Multiplicative | 68.5 | 112 |

| 1x7 / 7x1 Median | Multiplicative | 79.3 | 74 |

| 5x5 Median | Multiplicative | 75.6 | 89 |

| B-score Only | Additive | 65.8 | 121 |

Table 2: Computational Performance of Median Filters on Image Data

This table provides a benchmark of the execution time for different median filter kernels on a standard image size (1920x1080 pixels), illustrating the computational load. Performance data is adapted from NVIDIA's PVA platform documentation [20].

| Kernel Size | Image Format | Execution Time (ms) | Relative Cost vs 3x3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3x3 | U8 | 0.220 | 1.0x |

| 3x3 | U16 | 0.405 | 1.8x |

| 5x7 | U8 | ~2.9 (est.) | ~13.2x |

| 5x5 | U8 | 2.172 | 9.9x |

| 5x5 | U16 | 4.106 | 18.7x |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spatial Bias Correction Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 384-well Microtiter Plates | The standard platform for HTS assays; spatial bias patterns (edge effects, row/column trends) are routinely observed and corrected in data from these plates [6]. |

| Control Compounds | Inactive compounds used to map the background signal and spatial bias pattern across the plate, essential for validating the success of bias correction methods [6]. |

| Robust Z-Score Normalization | A statistical method used to normalize plate data after initial filtering; it uses the median and median absolute deviation (MAD) to minimize the impact of outliers (hits) on the normalization parameters [6]. |

| Virtual Plate Software | An analytical tool that collates selected wells from different plates into a new, virtual plate. This allows the rescue and analysis of compound wells that failed due to technical issues and facilitates easier review of hit data [21]. |

| High-Content Screening (HCS) Imaging Systems | Automated microscopy systems that generate the rich, image-based data often requiring advanced filtering and analysis to account for technical variability and spatial bias [21]. |

| Senfolomycin A | Senfolomycin A, CAS:101411-69-2, MF:C29H36N2O16S, MW:700.7 g/mol |

| Slimes and Sludges, cobalt refining | Slimes and Sludges, cobalt refining, CAS:121053-29-0, MF:C10H8ClNOS |

Troubleshooting Guide: Spatial Analysis in HTE Plates

Q: Our High-Throughput Experiment (HTE) data shows inconsistent replicate results. Traditional quality control metrics pass, but we suspect spatial artifacts. How can we identify these issues?

A: This is a common problem where traditional control-based quality metrics (like Z-prime or SSMD) fail to detect spatial artifacts affecting drug wells. Implement the Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) metric, a control-independent QC method that analyzes systematic errors in dose-response data by examining deviations between observed and fitted values across all compound wells [4].

- Recommended Thresholds: Based on large-scale pharmacogenomic dataset analysis (GDSC, PRISM, FIMM) [4]:

- NRFE < 10: Acceptable quality.

- NRFE 10–15: Borderline quality; requires scrutiny.

- NRFE > 15: Low quality; exclude or carefully review.

- Solution: Integrate NRFE with traditional metrics. This orthogonal approach can flag plates with issues like column-wise striping or edge effects that traditional methods miss, improving cross-dataset correlation [4].

Q: After confirming no spatial artifacts, how do we systematically test for significant spatial autocorrelation in our HTE readouts?

A: Use Global Moran's I, a common index for assessing spatial autocorrelation in areal data. It quantifies whether similar observations are clustered, dispersed, or randomly distributed across your plate [22].

- Interpretation: Moran's I values range from approximately -1 to 1.

- Significantly above E[I] = -1/(n-1): Positive spatial autocorrelation (clustering of similar values).

- Significantly below E[I]: Negative spatial autocorrelation (dispersion of similar values).

- Around E[I]: Random spatial pattern [22].

- Testing Significance: Use the

moran.test()function in R (from thespdeppackage) to calculate a z-score and p-value, or use a Monte Carlo approach (moran.mc()) to assess significance against a randomization distribution [22].

Q: We've detected significant global spatial autocorrelation. How can we pinpoint the specific locations or plate regions driving this pattern?

A: Apply Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA), specifically the local version of Moran's I. This statistic decomposes the global spatial pattern to provide a local measure of similarity between each well's value and those of its neighbors, identifying significant hot-spots or cold-spots of spatial clustering [22].

Q: Our dataset has many correlated readouts, making spatial patterns hard to interpret. How can we simplify this before spatial autocorrelation analysis?

A: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) as a preprocessing step. PCA reduces data dimensionality by transforming correlated variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components that capture most of the variance. You can then perform spatial autocorrelation analysis on the leading PCs to identify spatial bias in the most dominant patterns of your data [23].

Q: What are the essential computational tools and reagents for implementing this spatial analysis pipeline?

A: The following tools and packages are essential for the methodologies described.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

spdep R Package |

Provides functions for spatial dependence testing, including moran.test() and moran.mc(). |

Calculating Global and Local Moran's I [22]. |

| NRFE Metric | A quality control metric based on normalized residual fit error from dose-response curves. | Detecting systematic spatial artifacts in drug wells missed by traditional QC [4]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A statistical technique for reducing data dimensionality to simplify analysis. | Identifying dominant, uncorrelated patterns in complex HTE data before spatial analysis [23]. |

| Graph-based Clustering (e.g., Louvain) | An algorithm for clustering data points into distinct groups based on connectivity. | Partitioning data into transcriptionally or response-based distinct regions for analysis [23]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detecting Spatial Artifacts with NRFE

- Data Preparation: Compile raw data from your HTE plate, ensuring well locations (e.g., row, column) are recorded.

- Dose-Response Fitting: Fit a dose-response model (e.g., a four-parameter logistic curve) to the data for each compound-cell line combination on the plate.

- Calculate NRFE: Compute the Normalized Residual Fit Error. This metric evaluates deviations between observed and fitted values, applying a binomial scaling factor to account for response-dependent variance [4].

- Apply Thresholds: Classify plate quality using established NRFE thresholds (NRFE < 10: acceptable; 10-15: borderline; >15: poor). Plates with high NRFE should be reviewed for spatial artifacts like striping or gradient effects [4].

Protocol 2: Testing for Global Spatial Autocorrelation with Moran's I

- Define Spatial Weights: Create a spatial weights list that defines the proximity between different wells on your HTE plate. This can be done using

spdepin R, for example, by defining neighbors based on contiguity or distance [22]. - Run Global Moran's I Test: Use the

moran.test()function, passing your numeric data vector (e.g., a PC score or viability readout) and the spatial weights list. - Specify Hypothesis: Set the

alternativeargument to "greater" to test for positive spatial autocorrelation [22]. - Interpret Results: Examine the output for the Moran's I statistic, its expected value under no autocorrelation, and the p-value. A p-value below your significance level (e.g., 0.05) indicates significant spatial autocorrelation [22].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the integrated spatial analysis approach.

Spatial Analysis Workflow for HTE Plates

The next diagram classifies the types of spatial patterns you may encounter in your analysis.

Spatial Autocorrelation Pattern Types

Spatial bias presents a significant obstacle in High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), systematically compromising data quality and leading to increased false positive and false negative rates during hit identification [1]. This bias manifests as consistent pattern errors across plates due to factors including reagent evaporation, pipetting inconsistencies, and incubation time variations [1]. In drug discovery, where HTE platforms routinely process hundreds of thousands of compounds daily, uncorrected spatial bias can misdirect entire research campaigns, wasting valuable resources and time [1] [24].

This case study examines the integrated application of Plate-specific Pattern (PMP) correction algorithms and robust Z-scores to effectively overcome spatial bias. We demonstrate this methodology through a real-world scenario, supported by detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and visual workflows designed for practicing scientists.

Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Integrated Bias Correction Workflow

The successful correction of spatial bias follows a systematic, two-stage process. The workflow below outlines the complete procedure from raw data to validated hits:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Bias Correction

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Spatial Bias Identification and Correction