Overcoming Temperature Control Challenges in Automated Reactors: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Solutions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of temperature control challenges in automated reactors, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Overcoming Temperature Control Challenges in Automated Reactors: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Solutions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of temperature control challenges in automated reactors, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental dynamics of different reactor types, from dead-time dominant to runaway processes, and examines traditional PID through advanced AI-driven control methodologies. The content delivers practical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like nonlinear dynamics and dead time, while offering comparative validation of control techniques from cascade control to CNN-LSTM-based Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC). The synthesis of these perspectives aims to equip readers with the knowledge to enhance process efficiency, ensure product quality, and accelerate development timelines in biomedical research and pharmaceutical production.

Understanding Reactor Dynamics: The Root of Temperature Control Challenges

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Reactor Thermal Response

Q1: How can I determine if my chemical reactor is operating in a runaway regime?

The divergence criterion is one of the most advanced techniques for identifying reactor runaway conditions. This sensitivity-based criterion states that when a reactor is operating in a parameter-sensitive region, even slight changes in operating conditions can produce large deviations in output parameters. According to this criterion, thermal runaway begins when the divergence of the system's dynamic response becomes positive [1].

To apply this method:

- Monitor temperature trajectories during operation

- Calculate the divergence value based on temperature measurements

- A positive divergence value indicates sensitive parameter regions where runaway is likely

- This method works for single and multiple reaction types across batch, semibatch, and continuous stirred-tank reactors [1]

Q2: What percentage of chemical industry incidents are caused by reaction runaway, and which reactions are highest risk?

Statistical analyses of chemical accidents reveal that reaction runaway represents a significant portion of reported incidents [1]:

| Region/Study Period | Runaway Incident Percentage | Most Prone Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Europe (Sale et al.) | 24% of 132 reported events | Not specified |

| France (1974-2014) | 25% of chemical incidents | Polymerization (34.9%), Decomposition (18.6%), Nitration (9.3%) |

| United Kingdom (1988-2013) | Not specified | Polymerization (33%), Decomposition (13.3%) |

| China (1984-2019) | Not specified | Organic chemical industry (57.2%) |

Q3: What practical safety reinforcement can prevent thermal runaway in battery systems?

For Li-ion batteries, a Safety Reinforced Layer (SRL) can dramatically reduce explosion risk. Recent research demonstrates that a roll-to-roll produced SRL positioned between the aluminum current collector and cathode reduces battery explosions from 63% to 10% in impact tests on 3.4-Ah pouch cells [2].

The SRL utilizes molecularly engineered polythiophene (PTh) with tailored side chains to trigger a Positive Temperature Coefficient (PTC) transition around 100°C [2]. Under normal operation, the SRL has negligible resistance, but during internal short circuits or temperature surges, its conductivity drops, interrupting current flow and preventing thermal runaway.

Q4: What simulation tools are available for analyzing reactor dynamic behavior?

MATLAB with Simulink provides a robust platform for reactor simulation and analysis [3] [4]. The workflow includes:

- Physical Modeling: Establishing models describing nuclear reaction processes, heat transfer, and fluid dynamics

- Parameter Extraction: Obtaining reactor parameters through experiment or theoretical calculation

- Steady-State Analysis: Calculating power distribution, temperature profiles, and neutron flux at stable operation

- Dynamic Analysis: Examining transient behaviors during accident scenarios

- Safety Analysis: Evaluating safety margins and predicting accident progression [3]

Specialized tools like NUSOLSIM (developed by Xi'an Jiaotong University) offer accident simulation capabilities specifically for pressurized water reactors, modeling primary circuit flow abnormalities and other accident scenarios [5].

Thermal Runaway Criteria Comparison

| Criterion Type | Basis | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry-Based | Analyzes geometric characteristics of temperature or heat-release trajectory | Simple visualization | Cannot indicate intensity or extent of thermal runaway |

| Sensitivity-Based | Characterizes changes in governing operating parameters | Can identify parameter-sensitive regions | More complex computation |

| Divergence Criterion | Chaos theory-inspired; tracks trajectory divergence | Accurate runaway boundary identification; convenient online monitoring with temperature measurements only | Requires precise temperature data |

Experimental Protocol: Applying Divergence Criterion for Runaway Detection

Objective: Assess thermal hazards and identify runaway conditions in exothermic reactions [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Reactor system with temperature monitoring capability

- Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) apparatus

- Adiabatic calorimetry equipment

- Data acquisition system

Methodology:

- Parameter Acquisition: Using DSC and adiabatic calorimetry, obtain thermodynamic parameters and temperature curves for the reaction system

- Model Development: Create a system model based on acquired parameters

- Divergence Monitoring: During reactor operation, calculate divergence based on temperature measurements:

- Monitor temperature trajectories

- Calculate rate of change in system sensitivity

- Track the divergence of nearby system trajectories

- Threshold Identification: Determine the point where divergence becomes positive, indicating transition to runaway conditions

- Verification: Compare model predictions with experimental data to validate accuracy

Application Example: For styrene polymerization, this protocol successfully identifies runaway conditions and enables implementation of preventive controls before dangerous temperature excursions occur [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Polythiophene-based SRL | Safety reinforced layer for Li-ion batteries; provides current interruption during voltage drops or overheating [2] |

| PDDHEO Copolymer | Molecularly engineered polythiophene with tailored PTC transition at ~100°C; optimized for solubility in manufacturing-safe solvents [2] |

| Carbon Additives | Facilitates doping/de-doping kinetics in SRL; maintains high conductivity under normal operation [2] |

| MATLAB/Simulink | Platform for reactor modeling, simulation, and protection system testing [3] [4] |

| NUSOLSIM Software | Specialized PWR accident simulation software for educational and research applications [5] |

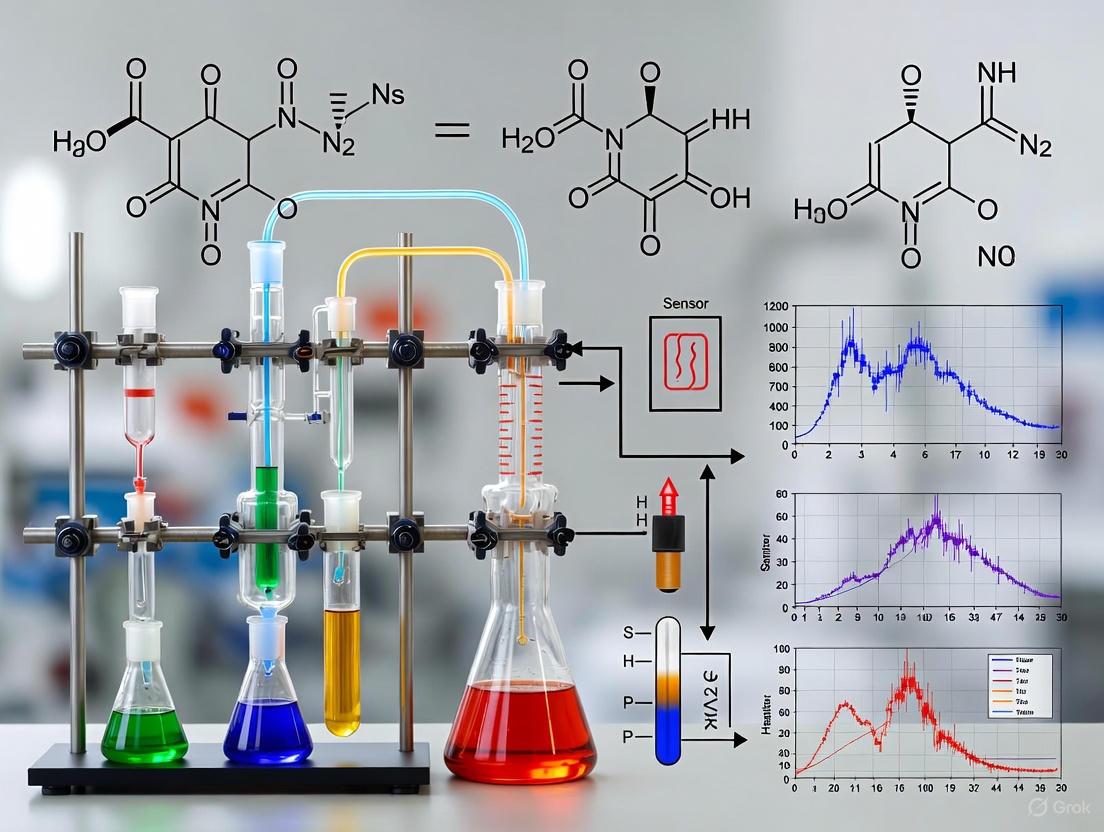

Workflow Diagram: Thermal Runaway Experimental Analysis

Thermal Runaway Mechanism Diagram

The Critical Impact of Dead Time on Control Stability and Performance

Core Concepts: Understanding Dead Time

What is dead time and how does it differ from other process delays?

Dead Time, also known as transportation lag or time delay, is a fundamental dynamic behavior in process control defined as the interval between a change in a process input and the first noticeable response in the measured output [6] [7]. For example, in temperature control, this is the delay between adjusting a heating valve and when the temperature sensor first detects any change [8].

This is distinctly different from lag time, which is the time (after dead time has elapsed) that the process variable takes to move 63.3% of its final value after a step change [9]. Dead time represents a period of complete non-response, where the controller effectively operates "blind" to the effects of its actions [6].

Table: Key Differences Between Dead Time and Dead Zone

| Aspect | Dead Time | Dead Zone |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Time delay before output changes | Input range with no output change |

| Primary Effect | Causes lag in system response | Causes insensitivity/sluggishness |

| Common Causes | Physical transport delay, sensor lag | Mechanical backlash, hysteresis |

| Measurement Unit | Time (seconds, minutes) | Percentage or signal units |

| Compensation Methods | Predictive control, tuning adjustments | Hysteresis compensation, tighter gains |

In temperature control for automated reactors, dead time arises from several physical and technical limitations:

- Physical Transport Delays: Time required for heated or cooled fluid to travel from control elements (valves, heaters) to the temperature sensor location [6] [10]. This is particularly significant in large reactor systems with extensive piping.

- Sensor Response Time: Thermal lag in temperature sensors (e.g., RTDs, thermocouples), especially when heavily shielded for harsh environments [10]. The mass of protective shielding adds considerable delay to temperature detection.

- Signal Processing & Computation: Digital control systems introduce delays through PLC/SCADA scan cycles, analog-to-digital conversions, and network communication latency [6].

- Final Control Element Response: Slow valve actuation, actuator hysteresis, or mechanical play in control linkages [6] [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosis and Quantification

How can I experimentally measure dead time in my reactor temperature control loop?

The step test method provides a straightforward experimental approach to quantify dead time using existing control system hardware [10]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Stabilization: Begin with the reactor at a steady operating temperature with controller in manual mode.

- Apply Step Change: Introduce a step change (typically 5-10%) to controller output (e.g., heating/cooling valve position).

- Data Recording: Continuously record both controller output and temperature measurement at high frequency (1-5 second intervals).

- Response Analysis: Identify two key time points in the data:

- Time when step change was applied to controller output

- Time when temperature first shows clear deviation from previous steady state

- Calculation: Compute dead time as the difference between these time points [10].

Table: Step Test Data Analysis for Dead Time Calculation

| Parameter | Example Value | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Step Initiation Time | 25.4 minutes | Moment of controller output change |

| First Response Time | 26.2 minutes | When PV shows clear, sustained deviation from baseline |

| Calculated Dead Time (θp) | 0.8 minutes | Difference: 26.2 - 25.4 min |

| Process Time Constant (Tp) | 3.2 minutes | Time to reach 63.3% of final temperature change |

| Process Gain (Kp) | -0.53°C/% | Ratio of PV change to CO change |

Critical Implementation Notes:

- Ensure the step change magnitude is sufficient to overcome normal process variability but not so large as to violate safety constraints

- Maintain all other process conditions constant during testing

- Repeat tests at different operating points to characterize dead time variability

- For processes with significant noise, apply filtering or use averaging to identify true response initiation

What are the characteristic symptoms of excessive dead time in control performance?

Excessive dead time manifests through specific observable patterns in control system behavior:

- Oscillatory Response: Continuous cycling around setpoint as controller overcorrects for perceived lack of response [6] [7]. The controller "thinks" its initial action was insufficient and applies more correction, leading to destructive overshoot.

- Slow Recovery from Disturbances: Sluggish response to process upsets due to necessary controller detuning [6]. The system takes longer to return to setpoint after unexpected deviations.

- Aggressive then Sluggish Behavior: Pattern where controller makes increasingly aggressive moves during dead time period, followed by excessive correction once process responds [7]. This resembles impatient shower temperature adjustment [7].

- Reduced Robustness: Increased sensitivity to process model inaccuracies and smaller stability margins [11]. Systems with significant dead time operate closer to instability limits.

Mitigation Strategies: Solutions and Compensations

What controller tuning adjustments are most effective for dead-time dominant processes?

For processes where dead time (θp) exceeds the time constant (Tp), conventional tuning rules fail, requiring specialized approaches:

The Fundamental Rule: "The longer the dead time, the slower the tune" [9]. This means reducing controller aggressiveness to accommodate the delay.

Ziegler-Nichols and Related Tuning Correlations: These classical methods incorporate dead time directly into tuning calculations, producing smaller controller gains and longer reset times as dead time increases [7]. The general form shows controller gain (Kc) inversely proportional to dead time: Kc ∠1/θp [10].

Table: Tuning Strategy Comparison for Dead-Time Dominant Processes

| Tuning Method | Approach | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| De-tuning (Conservative) | Reduce proportional gain, increase integral time | Processes with moderate, consistent dead time; operator comfort with sluggish response |

| Lambda Tuning | Set closed-loop time constant as multiple of dead time | Processes requiring consistent response shape; stability-priority applications |

| Cohen-Coon | Explicit dead-time compensation in tuning formulas | Dead-time dominant processes where moderate aggressiveness is acceptable |

| Smith Predictor | Model-based dead-time compensation | Processes with known, consistent dead time; high-performance requirements |

| Model Predictive Control | Optimization-based using process model | Complex processes with constraints; multiple interacting variables |

Implementation Guidance:

- Always start with more conservative (slower) tuning and gradually increase aggressiveness if needed

- For temperature control, initial tuning should achieve setpoint within approximately two dead time periods [9]

- Disable or minimize derivative action - it cannot compensate for dead time and typically worsens performance [9]

What advanced control strategies specifically address dead time compensation?

When dead time exceeds the process time constant (θp > Tp), advanced strategies become necessary:

Smith Predictor: This model-based approach uses an internal process model to predict the future system state, effectively "seeing ahead" of the delay [7]. The controller makes adjustments based on predictions rather than waiting for delayed measurements.

Implementation Requirements:

- Accurate process model (including dead time, time constant, and gain)

- Reasonably consistent process dynamics

- Minimal unmeasured disturbances

Model Predictive Control (MPC): MPC uses a dynamic process model to predict future behavior over a horizon and computes optimal control moves [6] [11]. It explicitly handles dead time through constraint management and multi-variable coordination.

Recent Advances: Current research focuses on data-driven modeling techniques, adaptive dead-time compensators for time-varying delays, and event-triggered controllers that reduce unnecessary control activity [11].

What physical modifications can reduce dead time at the source?

Before implementing complex control solutions, address fundamental physical sources of dead time:

- Sensor Relocation: Position temperature sensors closer to where heat transfer occurs to minimize transport delay [6]. Even small distance reductions can significantly impact dead time in slow-flow systems.

- Faster Response Instruments: Select temperature sensors with minimal thermal mass and faster time response [6] [8]. Replace heavily shielded sensors with appropriately rated faster-responding alternatives.

- Actuator Improvements: Upgrade control valves to reduce stiction and hysteresis [8]. Use smart positioners with feedback to minimize dead zone contributions.

- Pipework Optimization: Redesign piping to reduce distances between control elements and process vessels. Increase flow velocities where practical to reduce transport time.

- Signal Processing Enhancements: Reduce unnecessary filtering and optimize controller sample times [6]. Ensure scan rates are appropriate for the process dynamics.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much dead time is "acceptable" in reactor temperature control?

Acceptability depends on the relationship between dead time (θp) and process time constant (Tp) [10]:

- θp < Tp: Generally manageable with conventional PID control

- θp ≈ Tp: Challenging, requires careful tuning and possibly advanced strategies

- θp > Tp: Problematic, typically requires advanced control approaches

The absolute value matters less than this ratio. A 30-second dead time might be negligible in a batch process with a 2-hour time constant but catastrophic in a fast-acting continuous reactor.

Can dead time be completely eliminated from my process?

No, dead time is an inherent property of physical systems [6] [10]. The travel time of materials and finite response times of instruments fundamentally cannot be reduced to zero. The practical goal is minimization to levels where conventional control remains effective, or compensation when significant delays remain.

Why does derivative action not help with dead time?

Derivative action responds to the rate of change of the error signal. During dead time, there is zero rate of change because the process variable hasn't begun moving [9]. The derivative term receives no useful information and typically amplifies measurement noise, potentially worsening control performance.

How does dead time affect closed-loop stability?

Dead time directly reduces phase margin in control loops [11]. Each unit of dead time contributes additional phase lag that diminishes the stability margin. This forces conservative tuning (reduced gain), which compromises performance to maintain robustness. Systems with significant dead time operate closer to stability limits and are more sensitive to model inaccuracies.

What is the minimum possible dead time in a digital control system?

The minimum dead time equals the controller sample time (T) [10]. This represents the "measure, act, wait" cycle inherent in digital control. If model identification suggests dead time smaller than the sample time, apply the "θp,min = T" rule in tuning calculations [10].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Dead Time Analysis

Table: Key Research Tools for Dead Time Investigation and Compensation

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Process Step Testing | Experimental dead time quantification | Baseline assessment of existing control loops |

| First Order Plus Dead Time (FOPDT) Modeling | Dynamic process characterization | Controller tuning and Smith predictor implementation |

| Loop Tuning Software | Automated calculation of PID parameters | Initial tuning and performance optimization |

| Process Historian Analysis | Historical data mining for oscillation patterns | Troubleshooting existing loop performance issues |

| Control Valve Signature Analysis | Identification of mechanical dead zone | Differentiation between dead time and dead zone problems |

| Smart Temperature Transmitters | Reduced sensor lag through signal processing | Minimizing measurement-related dead time |

| Model Predictive Control Software | Advanced constraint handling with delay compensation | High-performance applications with significant dead time |

This technical support resource explores a core challenge in automated chemistry: how your choice of reactor—Plug Flow (PFR), Continuous Stirred-Tank (CSTR), or Batch—fundamentally dictates the strategy for achieving precise temperature control. For researchers in drug development and chemical synthesis, understanding this relationship is critical for ensuring reaction reproducibility, optimizing product quality, and maximizing the efficiency of automated high-throughput platforms [12] [13]. The following guides and FAQs address specific, common issues encountered during experiments, framed within the broader research context of managing thermal dynamics in automated systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Temperature Oscillations and Hotspots

Temperature instability is a common issue whose root cause often depends on your reactor type. Use this diagnostic workflow to identify and resolve the problem.

Diagnostic Steps:

For Plug Flow Reactors (PFRs):

- Symptom: Axial hotspots (a high-temperature zone at one point along the tube) or oscillating exit temperature.

- Investigation: Follow the PFR path in the diagram. Begin by checking the consistency of the reactant feed rate using a calibrated flowmeter. Any pulsation or fluctuation from the pump will directly cause temperature variations [14].

- Solution: If flow is unstable, service or replace the feed pump. If flow is stable, the issue is likely poor radial mixing. Inspect and clean internal static mixers or baffles to ensure efficient heat transfer across the reactor diameter and prevent localized runaway reactions [14].

For Batch Reactors:

- Symptom: Slow, large-amplitude temperature cycles or a sustained temperature differential between the reactor bulk and the jacket temperature reading.

- Investigation: Follow the Batch path in the diagram. First, verify that the agitator is operating at the set speed and that torque is sufficient for the current reaction viscosity. Poor mixing creates gradients [15].

- Solution: If mixing is inadequate, increase agitation speed or change the impeller type. If mixing is good, the control system's temperature sensor may be poorly calibrated or placed. Calibrate the sensor against a trusted standard and ensure it is positioned in a well-mixed zone of the reactor [16].

For Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactors (CSTRs):

- Symptom: Rapid, low-amplitude temperature fluctuations throughout the vessel.

- Investigation: Follow the CSTR path in the diagram. This symptom typically points to an external source. Analyze the temperature stability of the feed stream entering the CSTR; a poorly controlled pre-heater/cooler is a common culprit [17].

- Solution: Tune the temperature controller on the feed stream. If the feed is stable, confirm that perfect mixing is achieved, as even small stagnant zones can create thermal feedback loops that destabilize control [15].

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Conversion and Product Yield

When yield falls below expectations, the problem often stems from a mismatch between the reaction kinetics and the reactor's environment. The solution varies significantly by reactor type.

Diagnostic Steps:

In Batch Reactors:

- Problem: Inconsistent yield between batches or incomplete reaction.

- Solution: Ensure the temperature ramp rate is precisely controlled and reproducible. A deviation in the thermal profile can alter reaction pathways. Implement a controlled cooling and quenching step at the end of the reaction to prevent side reactions [14].

In PFRs:

- Problem: Lower-than-expected conversion.

- Solution: Confirm the reactor residence time. Calculate the space velocity and check for catalyst degradation or fouling that effectively reduces the active volume. For reactions with a strong thermal component, a single temperature setpoint may be insufficient; consider implementing a controlled axial temperature gradient to optimize the reaction path [14].

In CSTRs:

- Problem: Reduced yield and selectivity compared to batch experiments.

- Solution: Remember that a CSTR operates at the composition of the outlet stream, which is also the lowest reactant concentration. This can suppress the rate of the desired reaction. To overcome this, consider installing multiple CSTRs in series. This setup approaches the performance of a PFR, maintaining a higher average reactant concentration and improving overall yield [18] [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my highly exothermic reaction become unstable in my automated batch reactor, but seems controllable in a CSTR?

A1: This is due to a fundamental difference in process dynamics. A batch reactor operation is unsteady-state; as reactants are consumed and products form, the heat generation rate changes over time. For a highly exothermic reaction, this can lead to a true integrating or even runaway response, where any small temperature increase accelerates the reaction, releasing more heat in a dangerous positive feedback loop [17]. Control in a batch system is reactive. In contrast, a CSTR operates at a steady state with continuous feed and product removal. While a CSTR can also exhibit near-integrating or runaway responses for exothermic reactions, the constant inflow of cooler reactants and continuous mixing provides a more stable thermal mass and a mechanism for inherent temperature control, making it less prone to the unidirectional drift seen in batch systems [17].

Q2: We are scaling up a photochemical reaction from a small batch vessel to a continuous system. Which reactor type—PFR or CSTR—is better for maintaining consistent photon exposure and why?

A2: A Plug Flow Reactor (PFR) is generally superior for consistent photon exposure in photochemical reactions. In a PFR, each fluid element moves along the reactor length with minimal back-mixing, receiving a similar, well-defined dose of photons as it passes the light source. This results in a uniform reaction history [14]. In a CSTR, the contents are perfectly mixed, meaning some fluid elements may remain in the reactor for a very long time while others exit quickly. This leads to a broad distribution of photon exposure, with some molecules being over-exposed (potentially leading to degradation) and others under-exposed, reducing the overall efficiency and selectivity of the reaction [18] [15].

Q3: What is the most critical control parameter to optimize when transitioning a reaction from batch to a continuous PFR for pharmaceutical production?

A3: The most critical parameter is residence time and its distribution. In a batch reactor, all material reacts for the same amount of time. In a PFR, you must ensure that the flow rate and reactor volume combine to give the precise residence time needed for high conversion. Furthermore, you must minimize axial dispersion (back-mixing) in the PFR to maintain a sharp residence time distribution, which is key to achieving the high selectivity often required in pharmaceutical intermediates. This also simplifies scalability, as a PFR's performance is more predictable from lab to production scale [14].

Comparative Data Tables

The following tables summarize key quantitative and qualitative differences in control strategies across reactor types.

Table 1: Comparison of Reactor Control Dynamics and Tuning Strategies

| Parameter | Plug Flow Reactor (PFR) | Continuous Stirred-Tank (CSTR) | Batch Reactor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Dynamic Response | Moderate self-regulating [17] | Near-integrating or runaway (exothermic) [17] | True integrating or runaway [17] |

| Primary Temperature Control Tuning Objective | Minimize manipulated variable (MV) movement and overshoot [17]. | Minimize peak and integrated error for load disturbances [17]. | Minimize overshoot for setpoint changes and control batch end-point [17]. |

| Recommended PID Tuning | Maximize integral action; minimize proportional and derivative action [17]. | Maximize proportional and derivative action; minimize integral action [17]. | Use a 2DOF PID or setpoint lead-lag to prevent overshoot; may use no integral action for unidirectional drifts [17]. |

| Typical Applications | Large-scale, continuous production (e.g., petrochemicals), fast reactions [14] [15]. | Liquid-phase reactions, wastewater treatment, processes requiring rapid dilution [18] [15]. | Pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, small-scale R&D, fermentation [14] [12]. |

Table 2: Experimental Protocol Considerations for Temperature Control

| Consideration | Plug Flow Reactor (PFR) | Continuous Stirred-Tank (CSTR) | Batch Reactor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Thermal Challenge | Managing axial temperature profile & hotspots [14]. | Maintaining uniform temperature with continuous cold feed [18]. | Executing and controlling a precise temperature-time profile [14]. |

| Scale-up Consideration | Linear scaling is straightforward; maintain residence time [14]. | Scale by number of tanks in series or tank volume; mixing efficiency is critical [18]. | Scale-up is complex; heat transfer area-to-volume ratio decreases, risking heat buildup [14]. |

| Optimal For | High-temperature, high-pressure continuous processes [14]. | Reactions where concentration must be kept low to control selectivity [15]. | Reactions requiring long residence times and flexible, multi-step protocols [14] [12]. |

| Control Loop Dominant Dynamic | Can be dead-time dominant if using slow at-line analyzers [17]. | Dictated by the sign and degree of internal feedback from the reaction itself [17]. | Unsteady-state; composition and reaction rate change with time [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

When designing control strategies for automated reactors, the materials of construction are as important as the control logic. The table below lists key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Materials for Automated Laboratory Reactors

| Material or Solution | Function in Reactor Systems |

|---|---|

| Borosilicate Glass | The dominant material for laboratory-scale reactor vessels, offering exceptional resistance to thermal shock and chemical corrosion, making it suitable for reactions with rapid temperature changes [12]. |

| Dispersed Micron-Sized Photocatalyst | A reagent solution for photocatalytic continuous flow systems (e.g., CSTRs). The micron size prevents filter blockage, enabling long-term (e.g., >42 hour) continuous operation for applications like water purification [18]. |

| Erbia (Er₂O₃) / Integral Burnable Absorber | A neutron-absorbing material used in nuclear reactor control rods (a specialized reactor type) to manage core reactivity and power distribution over long operational cycles, analogous to a catalyst in chemical reactors [19]. |

| Stainless Steel (e.g., 316L) | Provides high mechanical strength and corrosion resistance for high-pressure reactions (e.g., hydrogenation) and industrial-scale applications [12]. |

| Dioctyl Terepthalate-d4 | Dioctyl Terepthalate-d4, MF:C24H38O4, MW:394.6 g/mol |

| 10-Deacetyl-7-xylosyl paclitaxel | 10-Deacetyl-7-xylosyl paclitaxel, MF:C50H57NO17, MW:944.0 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an endothermic and an exothermic reaction in the context of reactor temperature control?

An endothermic reaction absorbs energy from its surroundings in the form of heat, while an exothermic reaction releases energy as heat into its surroundings [20]. In a temperature-controlled reactor, an endothermic process will cause the system temperature to drop, whereas an exothermic process will cause it to rise [21]. This is critical for automated systems, as the internal feedback mechanism must apply heating or cooling accordingly to maintain the set temperature.

Q2: How can a self-optimizing reactor system distinguish between an endothermic and an exothermic event during an experiment?

Advanced systems use real-time analytical monitoring, such as inline NMR spectroscopy, to track reaction progress and yield independently of temperature changes [22]. By correlating changes in chemical conversion (observed via NMR) with temperature fluctuations in the reactor, the system's algorithm can determine the nature of the reaction and adjust parameters like heating or cooling flow rates to maintain stability.

Q3: Our automated reactor experiences unstable temperature control during a new exothermic reaction process. What are the first parameters to check?

The primary parameters to investigate are:

- Calibration of Temperature Sensors: Ensure probes are accurately reporting the internal temperature.

- Cooling Capacity and Responsiveness: Verify that the system's cooling mechanism can remove heat as rapidly as it is generated.

- Feedback Control Loop Gains (P, I, D): The algorithm's proportional, integral, and derivative parameters may be too aggressive or too sluggish for the reaction's kinetics, leading to temperature oscillations.

- Mixing Efficiency: Poor mixing can create local hot spots, causing inaccurate sensor readings and delayed control responses.

Q4: What does a typical experimental workflow for characterizing a novel reaction's thermal signature look like?

The workflow involves running the reaction in a calibrated, instrumented reactor (like a flow reactor) while monitoring both temperature and chemical conversion in real time. The data is fed to an optimization algorithm that maps the relationship between input parameters (e.g., reactant flow rates, temperature) and outputs (e.g., yield, heat flow) to determine if the reaction is net endothermic or exothermic under various conditions [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Sudden Temperature Excursion in Reactor

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immediate Action: Engage emergency cooling or halt reactant feed. | Halts the progression of the uncontrolled exothermic reaction. |

| 2 | Diagnosis: Check inline analytics (e.g., NMR, IR) data logs for a corresponding spike in conversion. | Confirms the temperature change is reaction-induced (exothermic) and not an equipment failure [22]. |

| 3 | Parameter Verification: Review the recent setpoint changes made by the optimization algorithm. | Identifies if an overly aggressive parameter shift triggered the excursion. |

| 4 | System Correction: Re-initialize the optimization algorithm with more conservative safety constraints and a slower learning rate. | Prevents a recurrence while allowing the experiment to continue safely. |

Problem: Inability to Maintain Target Temperature for an Endothermic Reaction

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Heating Power: Confirm the heating system is functional and has sufficient capacity. | Rules out a simple hardware failure. |

| 2 | Check Reaction Feed Rates: Ensure reactants are being supplied at the correct, stable rate. | A low feed rate may not be supplying enough material for the heater to counteract the endothermic effect. |

| 3 | Inspect Mixing: Ensure efficient mixing to guarantee even heat distribution and prevent cold zones. | Creates a uniform temperature field for accurate sensor readings and control. |

| 4 | Tune Control Loop: Adjust the PID controller to apply heating power more aggressively in response to a temperature drop. | Improves the system's ability to track the setpoint despite the continuous cooling effect of the reaction. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: Automated Optimization of a Flow Reactor

The following protocol, adapted from a study using inline NMR and Bayesian optimization, outlines how to characterize and optimize a reaction within an automated flow system [22].

Objective: To autonomously find the reaction parameters that maximize the yield of 3-acetyl coumarin via a Knoevenagel condensation.

Reagent Solutions:

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Salicylaldehyde | Primary reactant aldehyde. |

| Ethyl Acetoacetate | Reactant ketone. |

| Piperidine | Basic catalyst. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Solvent for reactants. |

| Acetone/Dichloromethane | Dilution solvent to prevent product precipitation before NMR analysis. |

Workflow:

- Feed Preparation: Two feed solutions are prepared. Feed 1 contains Salicylaldehyde and Piperidine catalyst in Ethyl Acetate. Feed 2 contains Ethyl Acetoacetate in Ethyl Acetate [22].

- Reactor Setup: Feeds are pumped via syringe pumps into a micromixer and then through a temperature-controlled capillary reactor where the reaction occurs [22].

- Inline Analysis: The reaction mixture is diluted and directed into a flow cell within a benchtop NMR spectrometer. A quantitative NMR (qNMR) protocol is automatically executed to measure conversion and yield [22].

- Feedback Loop: The measured yield is sent to the automation software. A Bayesian optimization algorithm uses this result to calculate and set new process parameters (e.g., flow rates of the two feeds) for the next experiment. The system repeats this loop until an optimal yield is achieved [22].

Quantitative Data Analysis via qNMR: Conversion and yield are calculated from the integrals of specific signals in the NMR spectrum [22]:

- Reference Integral (R): Aromatic protons (6.6 - 8.10 ppm). remains constant.

- Starting Material Integral (S1): Aldehyde proton of Salicylaldehyde (9.90 - 10.20 ppm).

- Product Integral (S2): Olefinic proton of 3-acetyl coumarin (8.46 - 8.71 ppm).

Formulae:

- Conversion (%) = [1 - (S1/R)] * 100%

- Yield (%) = (S2/R) * 100%

Reaction Energy Profiles

This diagram contrasts the energy pathways of endothermic and exothermic reactions, which is fundamental to understanding their temperature control challenges.

Automated Reactor Feedback Loop

This diagram illustrates the internal feedback and control logic of a self-optimizing reactor system, as described in the experimental protocol [22].

Advanced Control Strategies: From PID to AI-Driven Digital Twins

What are the core components of a PID controller and how do they function?

A PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controller is a feedback loop mechanism widely used in industrial control systems, including reactor temperature regulation. It calculates an "error" value as the difference between a desired setpoint (SP) and a measured process variable (PV), and applies a correction based on three distinct parameters [23].

- Proportional (P): The proportional term reacts to the current error. It produces an output that is proportional to the error value, multiplied by the proportional gain, Kp. A higher Kp results in a larger response to the current error, reducing rise time but potentially increasing overshoot and oscillations [24] [23].

- Integral (I): The integral term addresses the accumulated past error. It sums the error over time and multiplies it by the integral gain, Ki. Its primary function is to eliminate steady-state error, ensuring the process variable eventually reaches the setpoint. However, if set too high, it can cause significant overshoot and instability [24] [23].

- Derivative (D): The derivative term predicts future error based on its rate of change, multiplied by the derivative gain, Kd. This action dampens the controller's response, reducing overshoot and improving system stability. It is highly sensitive to noise in the measurement signal [24] [23].

What are the most frequent issues encountered with PID controllers in temperature control systems?

Troubleshooting a PID loop requires a systematic approach, beginning with simple checks before moving to complex diagnostics [25]. The table below summarizes common problems and their potential solutions.

Table 1: Common PID Controller Issues and Troubleshooting Steps

| Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillations | Overly aggressive P or I gains, mechanical issues, or electrical noise [24] [26]. | Monitor the process variable for consistent cycles. Check for loose sensor connections or faulty actuators [26]. | Retune the controller, reducing Kp and/or Ki. Ensure all mechanical connections are secure and use shielded cables for sensors [24] [27]. |

| Steady-State Error | Insufficient Integral action [26] [23]. | Observe if the process variable stabilizes below or above the setpoint. | Increase the Integral gain (Ki) to eliminate the offset [23]. |

| Slow Response | Overly conservative P and I gains [26]. | The system takes too long to reach the setpoint after a change. | Increase the Proportional gain (Kp) to speed up the response [23]. |

| Controller Won't Power On | Blown fuse, tripped breaker, faulty wiring, or engaged emergency stop [28] [25]. | Verify incoming power supply with a multimeter. Check all safety switches and fuses [28]. | Reset breakers or safety devices. Replace blown fuses. Check and secure all power connections [28]. |

| System Overheating | Sensor calibration drift, incorrect sensor placement, or a malfunctioning heating element [27]. | Cross-check sensor reading with a secondary probe. Inspect heaters and cooling components [27] [29]. | Recalibrate or reposition the sensor. Test heater continuity and ensure proper ventilation [27]. |

| Integral Windup | A sustained error causes the integral term to accumulate a very large value, leading to overshoot and a slow response when the error reverses [26]. | This often occurs when the controller output is saturated (e.g., a valve is fully open or closed) for an extended period. | Implement an anti-windup scheme in the controller, which typically involves disabling integral action when the output is saturated [26]. |

The following workflow provides a logical sequence for diagnosing a malfunctioning temperature control system:

PID Controller Troubleshooting Workflow

Tuning Rules and Algorithm Selection

What are the primary methods for tuning a PID controller?

Choosing the right tuning method depends on your system's dynamics, performance requirements, and available resources [30]. The main methodologies are:

- Manual Tuning: This involves adjusting the Kp, Ki, and Kd parameters based on trial and error and observing the system's response. It requires a skilled operator and can be time-consuming, but provides deep insight into the process behavior [30].

- Ziegler-Nichols Method: A classic empirical method that provides a systematic starting point for tuning. It involves finding the ultimate gain (Ku) that causes constant oscillation and the oscillation period (Pu), then calculating PID parameters using established rules [30] [23].

- Model-Based Tuning: This method uses a mathematical model of the system to simulate its behavior and predict optimal PID parameters. It can be highly accurate but requires a valid and often complex model of the process [31] [30].

- Auto-Tuning: Modern controllers often include auto-tuning features where software algorithms automatically adjust the PID parameters. This is typically the fastest and most convenient method, ideal for systems with unknown or complex dynamics [24] [30] [32].

How do I perform the Ziegler-Nichols tuning method?

The Ziegler-Nichols method is a widely used and effective tuning technique. The following protocol details the steps for the "ultimate cycle" method.

Experimental Protocol: Ziegler-Nichols Tuning

Objective: To determine the initial PID parameters (Kp, Ti, Td) for a stable and responsive control system.

Materials:

- The process to be controlled (e.g., reactor temperature system).

- PID controller with manual tuning capability.

- Data logging equipment to monitor the process variable (PV).

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Set the integral time (Ti) to infinity (effectively disabling the I term) and the derivative time (Td) to zero (disabling the D term). You are now using only proportional control [23].

- Increase Proportional Gain: With the system at a steady state, introduce a small setpoint change. Gradually increase the proportional gain (Kp) until the process variable exhibits sustained, constant oscillations. Caution: Ensure the oscillations remain bounded to avoid system damage [23].

- Record Critical Values: At the point of sustained oscillations:

- Record the value of Kp as the ultimate gain (Ku).

- Measure the period of the oscillations in seconds (or minutes) as the ultimate period (Pu) [23].

- Calculate Parameters: Use the Ziegler-Nichols table to calculate the initial PID parameters [23]:

Table 2: Ziegler-Nichols Tuning Parameters

| Control Type | Kp | Ti | Td |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 0.50 * Ku | - | - |

| PI | 0.45 * Ku | Pu / 1.2 | - |

| PID | 0.60 * Ku | 0.5 * Pu | Pu / 8 |

- Validation and Refinement: Implement the calculated parameters. The response will be aggressive with about 25% overshoot. Fine-tune the parameters manually to reduce overshoot or improve settling time for your specific application [23].

What other advanced tuning algorithms are available?

Beyond classic methods, several advanced algorithms can optimize PID performance, especially for complex or multi-loop systems.

Table 3: Advanced PID Tuning and Control Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|

| Cohen-Coon | Based on the process reaction curve; provides parameters for first and second-order systems [30]. | Systems with dominant time delays. |

| Internal Model Control (IMC) | Uses an internal model of the process to calculate controller parameters that provide a good balance between performance and robustness [31] [30]. | Systems with long time constants or integrating processes. |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) | An advanced control method that uses a dynamic model to predict future process behavior and compute optimal control actions, handling constraints explicitly [30]. | Complex, multi-variable, or highly constrained processes. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A machine learning technique that efficiently finds the global optimum of an unknown function. It is applied to automatic controller tuning through iterative closed-loop experiments [31]. | Tuning multi-loop PID controllers for MIMO processes with strong interactive behavior, where traditional methods struggle [31]. |

The relationships between different tuning methodologies and their applications can be visualized as follows:

PID Tuning Methodologies Overview

Auto-Tuning Features and Implementation

How does PID auto-tuning work, and what are the setup steps?

Auto-tuning automates the process of finding optimal PID parameters using built-in software algorithms, eliminating much of the guesswork from manual tuning [24]. Common algorithms work by perturbing the system—for example, by introducing a small step change or relay-induced oscillation—and analyzing the system's response to calculate appropriate P, I, and D values [24] [32].

Procedure for Activating Auto-Tune:

- System Preparation: Before initiating auto-tune, ensure your system is stable and has a sound mechanical foundation. Verify that all sensors and actuators are correctly connected and functioning, as inaccurate readings will lead to poor tuning results [24].

- Initial Parameters: Configure the controller with safe, conservative initial PID values. These do not need to be optimal but should provide a stable starting point for the auto-tuning process [24].

- Initiate Auto-Tune: Engage the auto-tuning function, often by placing the controller into a specific mode (e.g., "AT" or "Tune"). The controller will then perform its tuning sequence, which may take several minutes as it observes system dynamics [24] [32].

- Validation and Testing: Once auto-tuning is complete, the new parameters are typically saved automatically. It is crucial to test the system's performance by applying typical setpoint changes and disturbance rejections to validate the new settings. Make minor manual adjustments if necessary to fine-tune the response [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for a Temperature Control System

A reliable temperature control system for research reactors relies on several key components. The table below lists essential items and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Reactor Temperature Control

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Circulator | Provides heating/cooling fluid to the reactor jacket to maintain temperature [32]. | Look for models with auto-tuning PID functionality and a wide temperature range [32]. |

| PT100 Sensor (RTD) | A highly accurate temperature sensor that provides feedback to the PID controller [32]. | Offers better stability and accuracy than thermocouples for many lab applications [32]. |

| Thermocouple (J, K, T Type) | An alternative temperature sensor for a wide range of temperatures [32]. | Smaller size can be advantageous; may require a converter box for integration [32]. |

| Jacketed Reactor | A reactor designed with an external jacket to allow circulator fluid to flow around the vessel for uniform heat transfer [32]. | Ensures consistent temperature throughout the reaction volume. |

| Heat Transfer Fluid | The medium that transfers thermal energy between the circulator and the reactor. | Select a fluid with suitable viscosity, thermal stability, and low-temperature properties for your operating range [28]. |

| Shielded Cables | Used for connecting sensors to the controller to prevent electrical noise from interfering with the signal [27]. | Critical for avoiding noise that can disrupt PID control, especially the derivative term [27]. |

| Nepsilon-acetyl-L-lysine-d8 | Nepsilon-acetyl-L-lysine-d8, MF:C8H16N2O3, MW:196.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-Dihydro Tetrabenazine-d7 | trans-Dihydro Tetrabenazine-d7, MF:C19H29NO3, MW:326.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing Cascade and Split-Range Control for Complex Heat Transfer Systems

FAQs: Core Control Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between cascade and split-range control?

A1: Cascade and split-range control are advanced strategies that address different challenges. Cascade Control uses two linked controllers: a secondary controller (e.g., for coolant flow) regulates a fast-changing process variable, and a primary controller (e.g., for reactor temperature) manipulates the setpoint of the secondary controller to regulate the slow-changing, critical variable [33]. Split-Range Control uses a single controller to manipulate two or more final control elements (e.g., valves), typically to handle different operating ranges or phases of a process [33].

Q2: My reactor temperature is unstable. How can I determine if the controller is over-aggressive or if process disturbances are to blame?

A2: A simple and effective test is to place the temperature controller in manual mode and observe the process variable (PV) trend [34].

- If the PV continues to wander or worsens, the instability is likely due to process load fluctuations, and the controller may need to be tuned more aggressively.

- If the PV stabilizes, the controller's action was causing or amplifying the instability, indicating over-tuning [34].

Q3: What is the most common mistake in configuring a split-range control system?

A3: The most common error is setting the split point at 50% without considering the different sizes and flow characteristics of the two valves [33]. The split point should be calculated based on the valves' flow capacities (Cv) or actual flow rates to balance the process gain across the transition, ensuring consistent controller performance throughout the entire operating range [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Temperature Control in a Cascade Loop

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Action | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary temperature oscillates continuously | Over-tuned secondary (flow) controller | Place secondary controller in manual; if flow PV stabilizes, re-tune secondary loop [34]. | Re-tune secondary controller for less aggressive action. |

| Slow response to setpoint changes or process disturbances | Under-tuned primary controller or blocked final control element | Check if control valve is capable of stroking fully (e.g., not stuck at 80% open) [34]. "Bump" the process and observe response, consulting operations first [34]. | Re-tune primary controller; inspect, clean, or repair the control valve. |

| Temperature control is sluggish in one operating mode but not another | Incorrect split-point in a split-range subsystem | Perform valve characterization tests to determine actual flow curves for each valve [33]. | Calculate the correct split point using valve Cv or flow data and reconfigure the function blocks [33]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Heat Transfer Fluid and Hardware Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Action | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced heat transfer efficiency, high pressure drop | Fouling (mineral scale, sediment, organic matter) on heat exchanger surfaces [35] [36] | Review maintenance history; perform visual inspection during cleaning; measure temperature differentials and compare to design specs [35] [36]. | Implement a consistent water treatment program; clean the heat exchanger; consider installing a side-stream filtration system (10-20 micron) [35] [37]. |

| Fluid turns dark and thick; frequent strainer plugging | Oxidation or Thermal Cracking of heat transfer fluid [37] | Inspect fluid quality; check for exposure to air in the expansion tank at high temperatures; evaluate heater flow rates and temperatures [37]. | Drain and replace fluid; ensure expansion tank is sealed or has a nitrogen blanket; verify design flow rates are maintained through the heater [37]. |

| Leakage from heat exchanger | Corrosion, incorrect gaskets, or mechanical failure from poor service [36] | Perform a visual inspection for signs of corrosion, drips, or damaged components; conduct a pressure test to locate leaks [36]. | Replace damaged tubes; install correct gasket type and material; tighten connections to specified torque; clean mating surfaces before reassembly [36]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Determining the Correct Split Point for Dual Valves

Objective: To calculate and implement the optimal split point for a split-range control system, ensuring a linear relationship between controller output and total flow.

Materials:

- Control system with function generator (f(x)) blocks

- Two control valves of different sizes (e.g., for fine control and high capacity)

- Portable flow meter (or use installed flow meter)

- Data logging software or trend historian

Methodology:

- Isolate and Characterize Valves: With the process in a safe state, manually stroke each control valve from 0% to 100% open in 10% increments. At each step, record the valve position and the corresponding flow rate [33].

- Plot Flow Curves: Create a graph of flow rate (Y-axis) versus valve position (X-axis) for each valve.

- Calculate Split Point: Using the flow rates at a specific, high opening (e.g., 70% or 100% open) for both valves, calculate the ideal split point (SP) using the formula [33]: ( SP = \frac{Max\ Flow\ of\ Small\ Valve}{Max\ Flow\ of\ Small\ Valve + Max\ Flow\ of\ Large\ Valve} \times 100\% )

- Configure Control System: Program the function generators as follows [33]:

- f(x) for Small Valve: (0%, 0%) -> (SP, 100%)

- f(x) for Large Valve: (0%, 0%) -> (SP, 0%) -> (100%, 100%)

- Verify and Tune: Return to automatic control and test the system's response through the entire operating range. Retune the flow and temperature controllers as necessary.

Expected Outcome: The combined flow curve of the two valves will be significantly more linear, eliminating large process gain changes and enabling stable temperature control across all operating conditions [33].

Table: Example Split-Point Calculation Data

| Valve Description | Flow Coefficient (Cv) at 100% Open | Calculated Split Point (%) | Function Generator Configuration (X, Y pairs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Trim Valve (Fine Control) | 4 | ( SP = \frac{4}{4 + 46} \times 100\% = 8.0\% ) | f(x)1: (0,0) -> (8,100) |

| Large Trim Valve (High Capacity) | 46 | f(x)2: (0,0) -> (8,0) -> (100,100) |

Protocol 2: Field Check of Heat Exchanger Performance

Objective: To gather operational data to determine if a heat exchanger is transferring heat effectively or if fouling is the root cause of high temperatures.

Materials:

- Contact thermometers or use installed temperature indicators

- Pressure gauges

- Portable flow meter (if no installed meter is available)

Methodology:

- Under stable operating load, record the following data points [35]:

- Entering Cooling Water Temperature (

T_cw_in) - Leaving Cooling Water Temperature (

T_cw_out) - Entering Process Fluid Temperature (

T_p_in) - Leaving Process Fluid Temperature (

T_p_out) - Cooling Water Flow Rate (

F_cw) - Cooling Water Inlet and Outlet Pressures

- Entering Cooling Water Temperature (

- Calculate Key Metrics:

- Cooling Water ΔT:

T_cw_out - T_cw_in. Under normal conditions, this is typically ≈10°F to 15°F (6°C to 8°C) [35]. - Heat Load (Q):

Q = F_cw * Cp * (T_cw_out - T_cw_in)(where Cp is the fluid specific heat). - Pressure Drop: Compare the measured cooling water pressure drop across the HX to the design specification. A higher-than-normal drop may indicate tube blockages.

- Cooling Water ΔT:

Interpretation: If the cooling water ΔT is very small and the leaving process temperature is high, the heat exchanger may be fouled, preventing effective heat transfer. If the ΔT is large, the issue may be insufficient cooling water flow [35].

System Visualization

Diagram: Cascade and Split-Range Control Logic

Diagram: Split-Range Valve Characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment | Technical Specification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Flow Meter | Measures fluid flow rates in coolant lines for system characterization and valve profiling. | Key for split-point calculation. Ensure compatibility with process fluid and flow range [35]. |

| Calibrated Temperature Sensors (Thermocouples/RTDs) | Accurately measure inlet and outlet temperatures for both process and coolant streams. | Critical for calculating heat load and ΔT. Place close to heat exchanger ports [35]. |

| Data Logging Software | Records trends of PV, SP, and controller output over time for analysis. | Essential for diagnosing instability and verifying control loop performance post-tuning [34]. |

| Heat Transfer Fluid | Medium for transporting thermal energy to/from the reactor. | Select based on operating temperature range. Monitor for oxidation and thermal cracking [37]. |

| Parallel Filtration System | Removes particulates from heat transfer fluid to prevent fouling. | Use 10-20 micron filter media. A side-stream design allows for maintenance without shutdown [37]. |

| Function Generator (f(x) Block) | Configures the split-range logic in the control system. | Standard component in modern DCS/PLC systems. Configured with X-Y pairs to define valve response [33]. |

| (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me-C10-Br | (S,R,S)-AHPC-Me-C10-Br, MF:C34H51BrN4O4S, MW:691.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Beclometasone dipropionate-d6 | Beclometasone dipropionate-d6, MF:C28H37ClO7, MW:527.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This support center is designed for researchers and scientists implementing CNN-LSTM-based Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) for advanced reactor temperature regulation. The guidance is framed within the thesis context of addressing persistent challenges in automated reactors, such as handling exothermic reactions, nonlinear dynamics, and ensuring stability against thermal runaways [38] [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During the training of our CNN-LSTM model for the NMPC predictor, the validation loss plateaus early and the model fails to capture the reactor's dynamic response to coolant changes. What could be wrong? A: This is often related to inadequate training data or improper model architecture. Ensure your open-loop experimental data encompasses the full operational range, including extreme conditions like rapid heating or cooling phases [40] [41]. The data should capture the temporal dependencies of the exothermic reaction. Consider refining your hybrid architecture: the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) must be configured to effectively extract spatial features from sequential input data, while the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network requires sufficient memory cells to learn long-term temporal dependencies [42] [43]. Implementing a Bayesian Optimization (BO) framework for hyperparameter tuning can systematically improve model performance [44].

Q2: Our CNN-LSTM-NMPC controller shows excellent simulation performance but becomes computationally expensive and slow in real-time experimental application. How can we improve computational efficiency? A: This is a common hurdle when deploying deep learning-based NMPC. Consider adopting a "practical" NMPC approach. Instead of solving a complex Nonlinear Programming (NLP) problem online, use an iterative procedure that combines a nonlinear CNN-LSTM prediction with a local linearization of the model. This allows the optimization problem to be solved as a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem, which is computationally much faster [42]. Furthermore, investigate model simplification techniques or using a state-dependent ARX model whose coefficients are fitted by the CNN-LSTM network, leveraging its pseudo-linear structure for more efficient control law calculation [43].

Q3: When implementing the control, we experience a "snowballing" effect or temperature runaway after a disturbance, such as a feed flow increase. The condenser seems undersized. Is this a control or a design issue? A: This highlights a critical intersection of design and control. For autorefrigerated or evaporatively cooled reactors, conventional steady-state design heuristics can be insufficient. Research demonstrates that the condenser heat-transfer area required for dynamic stability can be an order of magnitude larger than that suggested by steady-state design to prevent temperature runaways, especially for systems with low conversion and high activation energy [38]. Your CNN-LSTM-NMPC can optimize the coolant flow, but it is bounded by the physical limits of your heat removal system. Re-evaluate your reactor and condenser design specifications concurrently with your control strategy.

Q4: How do we integrate the CNN-LSTM-NMPC controller with our existing reactor hardware (sensors, actuators, PLC)? A: Successful integration requires a layered approach. First, ensure robust data acquisition from high-precision temperature sensors (e.g., RTDs, thermocouples) [32] [45]. This data streams into your CNN-LSTM model running on a dedicated computational unit (e.g., an industrial PC or embedded system like Jetson Orin [41]). The NMPC algorithm calculates the optimal coolant flow rate or jacket temperature setpoint. This setpoint is then sent as a command signal to your final control element, typically a control valve or a variable speed pump for the coolant loop. A cascaded control structure can be beneficial, where the NMPC acts as a master controller providing a setpoint to a faster slave PID controller that directly manipulates the valve [39].

Q5: For a multi-purpose batch reactor, the process dynamics change significantly between different recipes. Can a single CNN-LSTM-NMPC controller handle this? A: A fixed model will struggle with this flexibility. You need an adaptive or learning-based strategy. One method is to train a robust CNN-LSTM model on a diverse dataset covering multiple operational scenarios. A more advanced solution is to integrate a Reinforcement Learning (RL) framework, such as an actor-critic method, with your NMPC. The RL agent can dynamically adjust the NMPC's weighting parameters or cost function based on real-time performance, allowing the controller to adapt to changing reaction kinetics and operating conditions [41]. This blends the predictive power of NMPC with the adaptive learning of RL.

The table below consolidates critical performance metrics and design findings from relevant studies on advanced reactor control.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Advanced Control Performance and Design Requirements

| Metric / Finding | Value / Result | System Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condenser area for dynamic stability | Can be >10x larger than steady-state design | Autorefrigerated reactor (prevents runaway) | [38] |

| Performance improvement with iterative PNMPCi-LSTM | 8% reduction in Integral Absolute Error (IAE) | Neutralization reactor setpoint tracking | [42] |

| Forecasting accuracy improvement (BO CNN-M-LSTM) | 8% better MAPE, 2% better NRMSE & R² vs. benchmarks | HVAC load forecasting (relevant for thermal management) | [44] |

| Coolant flow rate manipulation range | 0.25 to 0.75 mL/min | Lab-scale batch reactor experimental validation | [41] |

| Heater current input range | 4 to 20 mA | Lab-scale batch reactor experimental validation | [41] |

| Controlled temperature range | 0 to 100 °C (Reactor, Jacket, Coolant) | Lab-scale batch reactor | [41] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for CNN-LSTM-NMPC Implementation

This protocol outlines the steps for developing and validating a CNN-LSTM-NMPC controller for a bench-scale batch reactor, synthesizing methodologies from cited works [40] [42] [41].

1. System Identification & Data Acquisition:

- Setup: Instrument a jacketed batch reactor with a PT100 or thermocouple temperature sensor (T_r) and a flow meter/control valve on the coolant line [32] [45].

- Open-Loop Experiments: With the reactor charged with a representative solvent or reaction mixture, perform step tests and pseudo-random binary sequence (PRBS) tests by manipulating the coolant flow rate (Fc) and/or heater power (H). Record time-series data for inputs (Fc, H) and outputs (Tr, jacket temperature Tj).

- Data Preprocessing: Segment the data into training, validation, and test sets. Normalize all variables to a [0,1] or [-1,1] range to aid neural network training.

2. CNN-LSTM Model Development:

- Architecture Design: Construct a hybrid model. The initial CNN layer(s) (1D convolution) will extract local patterns and features from the sequential input window (e.g., past values of Fc, H, Tr). The output is then fed into an LSTM network layer(s) to capture temporal dynamics and long-term dependencies.

- Training: Train the model in a supervised manner to predict the future reactor temperature (T_r) over a prediction horizon. Use the preprocessed open-loop data. Employ Bayesian Optimization [44] to tune hyperparameters (number of filters, LSTM cells, learning rate).

- Validation: Evaluate the model's prediction accuracy on the unseen validation dataset using metrics like Mean Squared Error (MSE).

3. NMPC Formulation & Integration:

- Controller Design: Formulate the NMPC cost function to minimize the error between predicted T_r and its setpoint over the prediction horizon, with penalties on excessive control movement (coolant flow changes).

- Optimization: Implement the PNMPCi-LSTM algorithm [42]. At each control interval:

- Use the trained CNN-LSTM model to generate a base nonlinear prediction.

- Compute a local linearization of the CNN-LSTM model around the current state.

- Solve a QP problem to find the optimal sequence of coolant flow adjustments.

- Apply the first control action to the reactor.

- Constraints: Explicitly incorporate constraints on minimum/maximum coolant flow rate and reactor temperature for safety.

4. Real-Time Validation:

- Closed-Loop Testing: Implement the controller on a real-time platform (e.g., Python with control libraries, or compiled on an industrial PC). Conduct experiments to track a challenging temperature profile (e.g., ramp, hold, cool).

- Performance Assessment: Compare the performance against a well-tuned PID or linear MPC baseline in terms of setpoint tracking error (IAE), overshoot, and settling time after a disturbance [40] [39].

Visualization: Workflow and Diagnostics

Diagram 1: CNN-LSTM-NMPC Control Architecture Workflow

Diagram 2: Fault Diagnosis Decision Tree for Implementation Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Tools for CNN-LSTM-NMPC Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Jacketed Batch Reactor | Core vessel for conducting controlled chemical reactions. Provides a surface for heat exchange. | Glass or stainless steel, with ports for sensors and feed. |

| Precision Temperature Sensor | Accurate measurement of reactor temperature (T_r), critical for feedback and model training. | RTD (PT100): High accuracy and stability [32]. Thermocouple (Type J/K/T): Wide range, faster response [45]. |

| Coolant Circulation System | Provides manipulated variable for heat removal. Includes pump, reservoir, and heat exchanger/chiller. | Must have a variable speed pump or a control valve to adjust flow rate (F_c). |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Interfaces between physical sensors/actuators and the computational controller. | Converts analog signals (4-20 mA, mV) to digital data for the PC. |

| Computational Hardware | Runs the CNN-LSTM model and NMPC optimization in real-time. | Industrial PC or embedded AI platform (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson) for demanding models [41]. |

| Machine Learning Framework | Library for building, training, and deploying the CNN-LSTM model. | TensorFlow or PyTorch. |

| Model Predictive Control Toolbox | Solves the optimization problem at each control step. | CasADi, do-mpc, or custom Python code with cvxopt/osqp solvers. |

| Bayesian Optimization Library | Automates the tuning of neural network hyperparameters (layers, nodes, learning rate). | scikit-optimize, Optuna, or BayesianOptimization. |

| Mal-amido-PEG3-alcohol | Mal-amido-PEG3-alcohol, MF:C13H20N2O6, MW:300.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stigmasta-4,22,25-trien-3-one, (22E)- | Stigmasta-4,22,25-trien-3-one, (22E)-, MF:C29H44O, MW:408.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrating AI Digital Twins and Large Language Models for Real-Time Operational Guidance

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers using AI Digital Twins (DTs) and Large Language Models (LLMs) for real-time operational guidance, with a specific focus on temperature control challenges in automated reactor systems.

# Core Concepts and Architecture

What is the fundamental architecture for integrating LLMs with Digital Twins for real-time guidance?

The integration is typically structured in a multi-layer framework. The Interactive-DT framework, designed for Industry 5.0, outlines how LLMs can be embedded within a DT environment across three key layers [46]:

- Edge Layer: The LLM operates here to process real-time, unstructured data from sensors and lab equipment on-site, enabling immediate data pre-processing and alerting.

- DT Layer: The LLM interacts with the digital twin's virtual model, using the structured data to run simulations, identify anomalies, and generate explanatory insights.

- Service Layer: The LLM serves as a natural language interface for human operators, allowing them to query the system, receive summarized reports, and command the DT to run "what-if" scenarios for temperature optimization [46] [47].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow and information flow.

# Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: The LLM is generating implausible or physically impossible temperature control recommendations. How can we validate its outputs?

This is a known challenge where LLMs may produce "hallucinations" that violate the laws of physics [46].

- Solution: Implement a Digital Twin Constraint Engine. The digital twin model, which is grounded in the actual physics and chemistry of the reactor system, should be used to validate all LLM-generated recommendations before they are deployed [47]. The DT simulates the proposed action; if the simulation predicts a parameter (like temperature) will exceed a safe or feasible limit, the recommendation is rejected or flagged for human review.

- Methodology:

- Define Constraints: Explicitly code the operating limits of your reactor (e.g., max safe temperature, pressure limits, chemical compatibility) into the digital twin's logic.

- Pre-Deployment Simulation: Configure the system so that every control strategy proposed by the LLM is first run as a simulation in the digital twin.

- Feasibility Check: The digital twin checks the simulation results against the predefined constraints.

- Action Pathway: Only commands that pass this check are sent to the physical reactor. Failed commands are sent back to the LLM with an explanation, helping the model learn the system's constraints over time [47].

FAQ 2: Our digital twin's temperature simulations are drifting from the physical reactor's actual behavior. What could be causing this data mismatch?

Discrepancies between the virtual and physical twins often stem from issues in data quality, transmission, or model fidelity.

- Solution: A systematic validation of the entire data pipeline is required.

- Methodology:

- Calibrate Sensors: Physically verify the accuracy of all temperature sensors and transmitters in the reactor system.

- Check Connectivity: Investigate network stability. Use troubleshooting tools (e.g.,

TestNetin the Intelligent Hub for Windows Troubleshooting tool (HUBWTT) [48]) to validate that all required network ports are open and that there is no intermittent data loss from the edge to the cloud/DT server. - Inspect for Conflicting Controls: Check for scripts, Group Policy Objects (GPOs), or other management clients that might be applying unauthorized changes to system settings, creating conflicts between the DT's commands and other processes [48].

- Update the Model: The digital twin's underlying mathematical model may need recalibration to reflect catalyst decay, fouling, or other changes in the reactor's physical state.

FAQ 3: The system is suffering from "field blindness," where operators lack real-time visibility into temperature anomalies. How can we improve situational awareness?

This occurs when data is not synthesized and communicated effectively to human operators [49].

- Solution: Leverage the LLM as a real-time interface and analytics engine.

- Methodology:

- Implement LLM-Powered Monitoring: Use the LLM to continuously analyze the structured data stream from the digital twin [47].

- Set Alert Triggers: Program the LLM to recognize specific patterns, such as a rapid rate of temperature change or a persistent deviation from the setpoint.

- Generate Proactive Alerts: Instead of raw data, the LLM can generate natural language alerts (e.g., "Warning: Reactor 3 temperature is rising at 2°C/min and is projected to exceed the safe threshold in 5 minutes. Probable cause: cooling loop malfunction.").

- Natural Language Queries: Allow researchers to ask questions like, "What was the primary cause of the temperature spike in experiment B-24?" with the LLM providing a summarized answer from historical data [46] [47].

# Experimental Protocol for System Validation

Validating the LLM-DT Framework for Temperature Control in Catalytic Hydrogenation

This protocol outlines a method to test the efficacy of an integrated LLM-DT system in managing a common yet sensitive chemical process.

1. Hypothesis: An LLM-enhanced digital twin will provide more stable temperature control and generate more accurate root-cause analyses for thermal excursions compared to a traditional programmable logic controller (PLC).

2. Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials: The table below details the essential materials and their functions for this experiment.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Automated Laboratory Reactor (Borosilicate Glass, 0.5-2L) | Versatile vessel for performing hydrogenation; borosilicate glass offers thermal shock resistance [12]. |

| Substrate (e.g., Nitrobenzene) | Model compound for catalytic hydrogenation, a reaction sensitive to temperature and pressure. |

| Catalyst (e.g., Palladium on Carbon) | Heterogeneous catalyst to facilitate the hydrogenation reaction. |

| Temperature & Pressure Sensors | Provide real-time data on critical reaction parameters to the DT and LLM. |

| Digital Twin Software | A virtual model of the reactor, calibrated to simulate the hydrogenation reaction's thermodynamics. |

| Fine-Tuned LLM (e.g., modified open-source model) | The AI model trained on chemical engineering literature and reactor operational data to provide guidance. |

3. Workflow: The experimental and validation workflow is as follows.

4. Quantitative Metrics for Comparison: The table below outlines the key performance indicators (KPIs) to be measured.