Overcoming Temperature Control Challenges in Parallel Reactors: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article addresses the critical temperature control challenges faced by researchers and drug development professionals when using parallel reactor systems.

Overcoming Temperature Control Challenges in Parallel Reactors: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article addresses the critical temperature control challenges faced by researchers and drug development professionals when using parallel reactor systems. It explores the foundational principles of heat management, presents current methodological solutions for high-throughput experimentation, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common pitfalls, and provides a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of different reactor technologies. The insights are geared towards enhancing reproducibility, efficiency, and success rates in pharmaceutical synthesis and bioprocess development.

Why Temperature Precision is a Bottleneck in Parallel Reactor Systems

The Critical Impact of Temperature on Reaction Kinetics and Product Integrity

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Poor Reaction Reproducibility in Parallel Systems

Problem: Inconsistent yield or selectivity across reactors in a parallel system.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-uniform temperature distribution | Measure and log the actual temperature in each reactor vessel simultaneously. | Calibrate all heating/cooling blocks. Use a single, well-mixed thermal bath for all reactors. |

| Inadequate temperature control precision | Monitor temperature stability over time in an empty reactor using a high-precision probe. | Switch to a system with superior temperature control (e.g., Peltier-based) and smaller temperature fluctuations [1]. |

| Varied heating/cooling rates | Time how long each reactor takes to reach a setpoint temperature from ambient. | Ensure consistent fill volumes and vessel material across all reactors. Standardize the ramp rate in the control software. |

Guide 2: Addressing Unexpected Reaction Outcomes and Degradation

Problem: Formation of new impurities, decreased yield, or product decomposition.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Localized overheating (hot spots) | Compare outcome between conventional and microwave heating (if feasible). | Implement focused heating methods or use catalysts that lower activation energy to avoid excessive bulk heating [2]. |

| Exceeding compound thermal stability limit | Perform a thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of the starting materials and product. | Lower the reaction temperature and extend reaction time, or use a catalyst to facilitate the reaction at a milder temperature [3]. |

| Shift in chemical equilibrium | Determine if the reaction is exothermic or endothermic. Measure yield at different temperatures. | For exothermic reactions, lower the temperature to favor the product side, as per Le Châtelier’s principle [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does a small temperature change sometimes cause a large change in my reaction rate? The relationship between temperature and reaction rate is exponential, not linear, as described by the Arrhenius equation ((k = A \cdot e^{-Ea/RT})). A modest temperature increase provides a greater proportion of molecules with enough energy to surpass the activation energy ((Ea)), dramatically increasing the successful collisions and thus the reaction rate [3].

Q2: In a parallel reactor block, how can I ensure every vessel is at the same temperature? Achieving perfect uniformity is challenging. To maximize it, use reactors designed for temperature control uniformity, ensure consistent reaction volume and vessel type in all positions, and employ a calibration routine to map any block variations. Advanced systems use individual temperature sensors and control loops for each vessel to correct for positional differences [1].

Q3: My reaction is exothermic. How should I manage temperature control? Exothermic reactions can lead to dangerous runaways. Always use a temperature probe in the reaction mixture, not just the bath. Set up cooling, not heating, to be the primary control action. Program the reactor to trigger an alarm or stop reagent addition if the temperature exceeds a safe threshold. Scale-up should be done with extreme caution as heat dissipation becomes more difficult [3].

Q4: What are the best practices for transferring a reaction from a single reactor to a parallel system? The key is to ensure thermal equivalence, not just matching the setpoint. Characterize the heating/cooling rate and temperature stability of your single reactor. Then, mimic these profiles in the parallel system. Pay close attention to mixing efficiency, as it affects heat transfer. Finally, run a validation experiment to confirm reproducibility across all parallel positions [1] [4].

Quantitative Data on Thermal Configurations

The choice of flow configuration in reactor design critically impacts temperature distribution and performance. The table below summarizes findings from a comparative thermal-hydraulic analysis in a Dual Fluid Reactor mini demonstrator, illustrating trade-offs relevant to chemical reactor design [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Parallel and Counter Flow Configurations

| Feature | Parallel Flow Configuration | Counter Flow Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Lower, as the temperature gradient decreases along the flow path [5]. | Higher, maintains a more consistent and significant temperature gradient across the entire exchanger [5]. |

| Temperature Distribution | Gradual temperature equalization along the flow path; can lead to local hot spots [5]. | More uniform coolant temperature distribution; reduces risk of localized overheating [5]. |

| Flow Dynamics & Swirling | Can generate intense swirling in fuel/coolant pipes [5]. | Reduces swirling effects, leading to a more streamlined flow [5]. |

| Mechanical Stress | Higher mechanical stress and pressure drop due to swirling [5]. | Lower mechanical stress and pressure drop, enhancing structural stability [5]. |

| Typical Application | Simpler systems where gradual heat exchange is acceptable [5]. | High-temperature systems, cryogenic processes, and applications requiring efficiency and material safety [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Temperature Uniformity in a Parallel Reactor Block

Objective: To map and verify the temperature uniformity across all positions in a parallel reactor system.

Materials:

- Parallel reactor station with temperature control

- High-precision, calibrated temperature probes (one per reactor position)

- Data logging system

- Heat transfer fluid (if applicable)

Methodology:

- Setup: Fill all reactor vessels with an identical volume of a inert solvent with similar thermal properties to your reaction mixture.

- Instrumentation: Place a temperature probe in the center of the liquid in each vessel, ensuring consistent depth.

- Data Collection:

- Set the reactor system to a common target temperature (e.g., 50°C, 100°C).

- Start the data loggers and begin heating.

- Record the temperature in each vessel every 30 seconds until all vessels have reached the setpoint and stabilized for 30 minutes.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the average temperature across all vessels at the end of the stabilization period.

- Determine the range (min, max) and standard deviation of the temperatures.

- A well-performing system should have a standard deviation of less than 0.5°C.

Protocol 2: Determining the Optimal Temperature for a Catalytic Reaction

Objective: To efficiently identify the temperature that maximizes yield and selectivity for a given reaction using a parallel and automated approach.

Materials:

- 96-well photoreactor or equivalent parallel reaction system [4]

- Stock solutions of catalyst, ligands, and substrates

- Automated liquid handling system (optional but recommended)

- GC-MS or HPLC for analysis

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Use a machine learning framework (e.g., Minerva) or a structured design-of-experiments (DoE) approach to define a set of experiments that varies temperature along with other key parameters like catalyst loading and solvent ratio [4].

- Parallel Execution:

- Use an automated system to dispense reagents into the reaction vessels according to the experimental design.

- Set each vessel to its designated temperature as per the DoE matrix.

- Initiate the reactions simultaneously and allow them to run for the set duration.

- Analysis & Modeling:

- Quench the reactions and analyze the samples for yield and selectivity.

- Input the results into the ML model or statistical software.

- The model will predict the optimal combination of parameters, including temperature, to maximize the desired objectives [4].

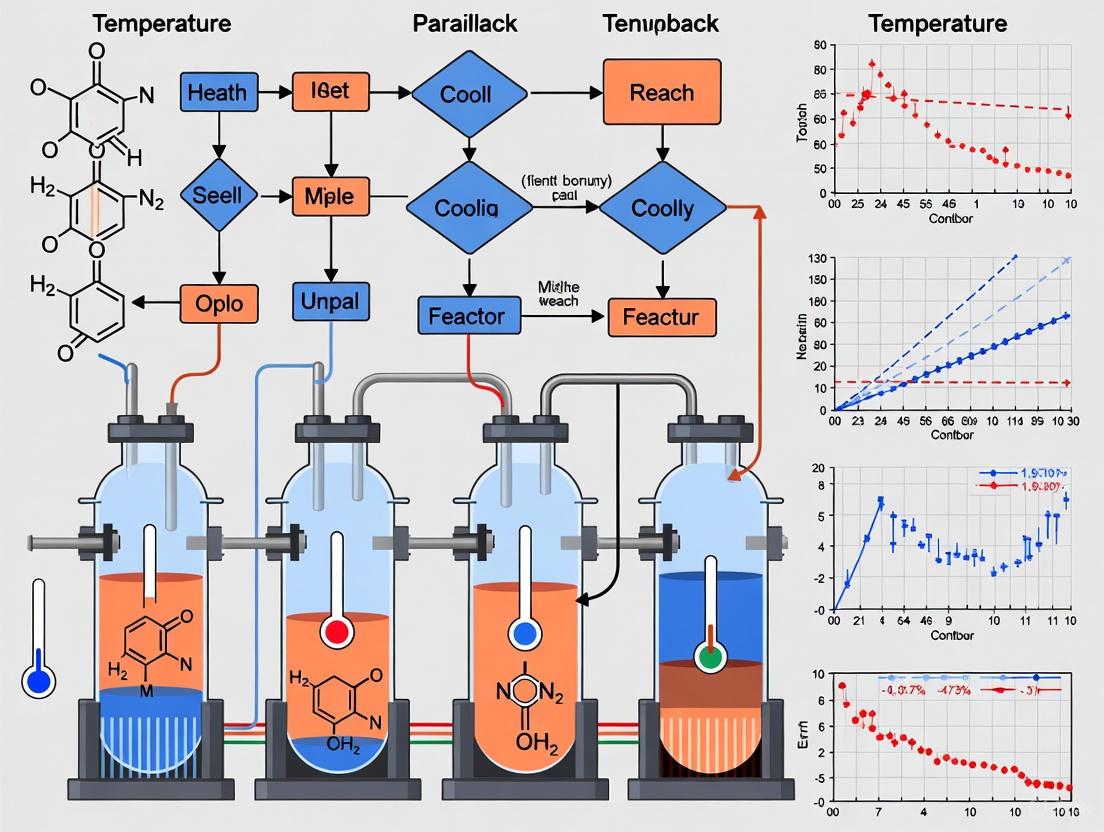

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines a systematic logic for troubleshooting temperature-related issues in parallel reactors.

Diagram 1: Temperature Troubleshooting Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Temperature-Controlled Parallel Reactor Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Temperature-Controlled Modular Photoreactor | Enables precise control of internal reaction temperature (e.g., from -20°C to +80°C) for both batch and flow processes, ensuring remarkable reproducibility [1]. |

| High-Temperature Laboratory Furnace | Used for synthesis, calcination, and thermal treatments that require precise control of reaction conditions at very high temperatures [3]. |

| Precision Circulators/Chillers | Maintains accurate temperature control for cooling or heating external reactor jackets, ensuring thermodynamic equilibrium and reproducibility [3]. |

| Zeolite-based Catalysts with Metallic Antennas | Porous materials (e.g., zeolite with indium ions) that can be excited by tuned microwaves to focus thermal energy at specific active sites, enabling lower bulk reaction temperatures and higher efficiency [2]. |

| Machine Learning Optimization Software (e.g., Minerva) | A computational framework that uses algorithms like Bayesian optimization to efficiently navigate complex reaction spaces and identify optimal temperature parameters alongside other variables from high-throughput data [4]. |

| Drying Ovens & Incubators | Provide uniform heating for sample preparation and stable environments for biological or chemical long-term stability studies under defined conditions [3]. |

| Napyradiomycin C1 | Napyradiomycin C1, CAS:103106-20-3, MF:C25H28Cl2O5, MW:479.4 g/mol |

| Tuftsin | Tuftsin (TKPR) Tetrapeptide | Macrophage Activator |

FAQs: Addressing Common Thermal Management Questions

What causes temperature overshoot in my reactor, and how can I prevent it? Temperature overshoot often occurs in systems with a long thermal lag between the heater and thermocouple, and when using heating elements designed for much higher temperatures than the setpoint [6]. This is common when working below 150°C with reactors built for higher-temperature operations (up to 350°C) [6]. To prevent it, you can perform an autotune of your controller's PID algorithm, which optimizes control parameters for less overshoot and oscillation. For setpoints below 125°C, improving heat dissipation by using a fan on the vessel during autotuning can help the process succeed [6].

Why does my reactor overheat and burn out? Reactor overheating typically stems from three core issues: poor cooling design, harmonic-induced losses from electrical equipment, and material degradation [7].

- Poor Cooling: Blocked airflow ducts or dust-clogged radiators can reduce cooling efficiency by 40% or more, leading to drastic temperature spikes [7].

- Harmonic Losses: Nonlinear loads like variable frequency drives can generate harmonics, increasing copper losses by 25-40% and causing excessive heating [7].

- Material Degradation: Aged insulation or dust layers trap heat and can accelerate failure [7]. Implementing smart cooling systems and harmonic filters are key solutions [7].

My stirring speed oscillates and won't reach its setpoint. Could this affect temperature control? Yes, unstable stirring directly impacts temperature control by causing uneven mixing and heat distribution. Oscillation before reaching a speed setpoint is often a result of the PID control algorithm in the Motor Control Module (MCM) [6]. To resolve this, ensure the Local/Remote switch is in "Remote" mode and the Motor power switch is always "On" to prevent controller windup [6]. Also, verify that your hardware, like the pulley system, can mechanically support the desired speed [6].

The High Limit Alarm has tripped. What should I check? A tripped High Limit Alarm interrupts power to the heater as a safety measure. You should check these conditions [6]:

- Thermocouple Connection: Check for an interrupted connection by wiggling the thermocouple and extension wire. A faulty component will cause the display to show errors or unrealistic temperatures.

- Pressure Connection: Ensure the pressure transducer is connected and reading correctly.

- Alarm Setpoints: Verify that the process temperature or pressure has not exceeded the configured alarm setpoints (AL1.H for temperature).

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide to Temperature Overshoot and Control Instability

Symptoms: Temperature consistently exceeds the setpoint before stabilizing, continuous oscillation around the setpoint, or inability to maintain a stable temperature [6].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Sensor Input: Check that the Primary Temperature meter is not displaying "No Cont," which indicates a broken thermocouple or faulty wiring [6].

- Check Heater Power: Confirm the heater switch is in Position 1 (low) or 2 (high) and that the High Limit Alarm has not tripped [6].

- Inspect for Fouling: Reactor fouling creates an insulating layer on internal walls and heat exchangers, significantly reducing heat transfer efficiency and leading to control issues [8].

Solutions:

- Perform Controller Autotune: Run the built-in autotune function on your temperature controller. This allows the system to characterize its thermal response and calculate optimal PID values [6]. Note: Autotuning is most successful at temperatures above 150°C. For lower temperatures, using a fan to cool the vessel can help the autotune process complete. [6]

- Implement Advanced Control Algorithms: Upgrade to systems that use adaptive control, model predictive control (MPC), or fuzzy logic for better handling of complex, nonlinear processes [9].

- Ensure Efficient Heat Transfer: Integrate efficient thermal management systems, such as jacketed reactors with circulation loops, to ensure precise regulation and uniform heat distribution [9].

Guide to Reactor Overheating and Burnout

Symptoms: Persistent high operating temperatures, unusual noise from reactors or transformers, burning smell, tripped breakers, or inter-turn shorts [7].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Inspect Cooling Systems: Look for blocked airflow paths and dust accumulation on radiators. A layer of dust as thin as 3-5mm can reduce cooling efficiency by 40% [7].

- Analyze Power Quality: Use a power quality analyzer to check for harmonic distortion (Total Harmonic Distortion, or THD). THD levels above 5% can indicate significant harmonic-related heating [7].

- Check Insulation Integrity: Look for aged or cracked insulation, which can lead to partial discharge activity spiking by 300% at elevated temperatures, accelerating failure [7].

Solutions:

- Upgrade Cooling Systems: Implement CFD-optimized airflow designs, liquid cooling (e.g., fluorinated immersion cooling dissipating up to 3000W/m²), or self-cleaning radiators to reduce dust buildup by 80% [7].

- Install Harmonic Mitigation: Use filter reactors to neutralize 2nd to 50th harmonics, which can reduce THD from 28% to 4% and cut losses by 35% [7].

- Use Advanced Materials: Replace conventional cores with low-loss amorphous alloy cores to significantly reduce magnetic losses and heat generation [7].

Quantitative Data on Reactor Overheating Causes and Solutions

The table below summarizes core failure causes and the performance of implemented solutions based on industrial case studies [7].

| Core Cause | Impact | Solution | Result & ROI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Cooling Design (e.g., dust accumulation >200mg/m³) | Cooling efficiency reduced by 40%; Winding temperature spike from 85°C to 135°C [7] | Liquid cooling + Self-cleaning radiators [7] | Temperature reduced from 135°C to 85°C; ROI: 2 years [7] |

| Harmonic-Induced Losses (from VFDs, arc furnaces) | Copper losses increased by 25%-40%; THD up to 35% [7] | Amorphous alloy cores + Active harmonic filters [7] | Annual savings of €500,000; ROI: 1.5 years [7] |

| Material Degradation (aged insulation, environmental stress) | Partial discharge activity increased by 300% at 110°C [7] | Plasma coating + Smart monitoring systems [7] | Replacement costs reduced by 70%; ROI: 3 years [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Autotuning a Reactor Temperature Controller

Purpose: To optimize the PID parameters of a temperature controller, minimizing overshoot and improving stability, particularly after system changes or when working at a new temperature setpoint.

Materials:

- Parr 4848 or 4838 controller (or equivalent with autotune functionality) [6]

- Reactor system with calibrated thermocouple

- Cooling fan (optional, for low-temperature autotuning) [6]

Methodology:

- Setup: Ensure the reactor is properly assembled and filled with a representative solvent or reaction mixture for the intended experiments. Verify that the thermocouple is correctly inserted and the heater is operational.

- Initialization: On the controller, navigate to the temperature control menu and select the autotune function. Enter the desired target setpoint temperature.

- Execution: Start the autotune process. The controller will now apply full power to the heater and observe the rate of temperature rise. It will then cycle the power to observe the cooling characteristics. Do not interrupt this process. [6]

- Troubleshooting:

- If autotune fails or aborts, it is often because the system takes too long to cool down, causing the algorithm to timeout. This is common for setpoints below 150°C. [6]

- Solution: Position a fan to blow air on the external surface of the reactor vessel to enhance heat dissipation and repeat the autotune. [6]

- Validation: Once autotune is complete, set the controller to the same target temperature and observe the heating profile. A well-tuned system should reach the setpoint with minimal overshoot (<2°C) and no sustained oscillation.

Protocol: Characterizing Thermal Uniformity in a Parallel Reactor System

Purpose: To assess and map the temperature profile across multiple reactors in a parallel setup, identifying the presence and severity of "heat islands" (hot or cold spots).

Materials:

- Parallel reactor system (e.g., Parr Parallel Reactor System or similar) [10]

- Multiple calibrated temperature probes (PT100 sensors or thermocouples) [9]

- Data logging software (e.g., JULABO EasyTEMP or equivalent) [9]

- Heat transfer fluid and circulation system (e.g., JULABO Presto circulator) [9]

Methodology:

- Instrumentation: Place a primary temperature sensor in each reactor vessel as per standard operation. For a detailed map, introduce additional calibrated sensors at different locations within a select vessel (e.g., near the walls, at the center, near the liquid surface).

- System Configuration: Connect the circulation system to the reactor jackets and set all reactors to the same target temperature. Ensure the stirring speed is identical and sufficient across all vessels.

- Data Acquisition: Start the data logging software. Initiate the heating ramp and hold the system at the target temperature for a sustained period (e.g., 60-90 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Record the temperature from all sensors at regular intervals. Calculate the average temperature and standard deviation for each reactor and for the system as a whole at steady state.

- Interpretation: Identify any reactors that consistently run hotter or colder than the setpoint. A standard deviation of more than 1-2°C between identical reactors under the same conditions indicates significant thermal imbalance, requiring calibration or hardware inspection.

System Diagrams and Workflows

Troubleshooting Logic for Thermal Overshoot

Advanced Reactor Temperature Control System

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and technologies crucial for managing thermal challenges in parallel reactor environments.

| Item | Function & Relevance to Thermal Challenges |

|---|---|

| PT100 Sensor / Thermocouple | High-precision temperature sensor providing critical feedback for control loops. Essential for accurate PV (Process Variable) measurement to prevent overshoot. [9] |

| PID Controller with Autotune | The brain of the system. Uses a Proportional-Integral-Derivative algorithm to adjust heater power. Autotune functionality is vital for automatically optimizing PID parameters to suit a specific reactor's thermal dynamics. [6] [9] |

| Circulating Bath / Heater Chiller | Provides precise heating or cooling fluid to reactor jackets. Maintains a stable thermal environment and is critical for dissipating excess heat from exothermic reactions. [9] |

| Amorphous Alloy Cores | Advanced core material for reactors and inductors. Significantly reduces magnetic core losses (harmonic-induced heating), a common cause of burnout in electrical components. [7] |

| Active Harmonic Filter | Mitigates harmonic distortion from non-linear loads (e.g., VFDs). Reduces harmonic-induced copper and core losses by up to 40%, preventing premature overheating. [7] |

| Anti-Fouling Additives | Chemical additives that inhibit the deposition of scale and polymers on reactor walls. Help maintain optimal heat transfer efficiency by preventing fouling, a major cause of temperature control issues. [8] |

| Self-Cleaning Radiators | Cooling components with auto-purge technology. Reduce dust buildup by up to 80%, maintaining cooling efficiency and extending maintenance cycles. [7] |

| Phospholine | Phospholine, CAS:124123-09-7, MF:C25H40NO8P, MW:513.6 g/mol |

| Cardenolide B-1 | Cardenolide B-1, MF:C30H44O8, MW:532.7 g/mol |

In pharmaceutical research and development, particularly in fields utilizing parallel reactors for drug synthesis and formulation, maintaining the cold chain—an uninterrupted temperature-controlled supply chain from product manufacture to patient administration—is not merely a logistical concern but a fundamental prerequisite for product efficacy and patient safety [11]. A temperature excursion, defined as an exposure of a product to temperatures outside its specified stability range (typically 2°C to 8°C for refrigerated items) during storage or transit, can compromise the chemical and physical stability of temperature-sensitive active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and final drug products [11] [12]. For researchers, such excursions can invalidate experimental results, ruin valuable samples, and set back development timelines significantly.

The integrity of the cold chain is especially critical given the rise of biologics, cell and gene therapies, and mRNA vaccines, which are particularly susceptible to temperature variations [11]. Exposure outside recommended ranges can induce protein aggregation or denaturation—chemical changes often undetectable visually—or manifest as visible alterations in viscosity or color [11]. The consequences range from a complete loss of potency and reduced efficacy to the formation of harmful degradation products, posing a direct risk to patient safety and resulting in substantial economic and resource wastage [11] [12].

Experimental Investigation: Quantifying the Excursion

Methodology: Simulating a Power Outage

To understand the real-world impact of a common laboratory incident—a power outage—on stored medications, a simulated study was conducted using a specialized medication refrigerator (model ESCO HR1-140T) [11].

- Equipment Setup: The refrigerator was filled with expired medications to simulate standard operating conditions. Temperature was monitored using:

- The refrigerator's inbuilt platinum sensor probe (PT100).

- Two additional TempTale Ultra data loggers (NIST calibrated, accuracy ±0.5°C). One was placed on the bottom shelf, and a second was placed inside a closed insulin medication box on the middle shelf to simulate the micro-environment of a packaged drug [11].

- Experimental Procedure: The refrigerator was switched off at the power outlet after confirming all monitors were within 2°C to 8°C. Temperatures were recorded from 25 minutes prior to the simulated outage, throughout a 2.5-hour power loss period, and until all monitors consistently returned to the safe range for 15 minutes. The refrigerator's built-in probe logged data at 5-minute intervals, while the TempTale loggers recorded at 1-minute intervals [11].

Key Quantitative Findings

The data revealed a critical lag between the refrigerator's air temperature and the temperature experienced by medications themselves, particularly during the recovery phase.

Table 1: Mean Time to Temperature Excursion (>8°C) and Recovery (<8°C)

| Monitoring Device Location | Time to >8°C (Power Loss) | Time to <8°C (Power Restored) |

|---|---|---|

| Refrigerator Built-in Probe | 12.5 minutes | 17.5 minutes |

| Data Logger on Shelf | 23 minutes | 89 minutes |

| Data Logger in Medication Box | 26 minutes | 70.5 minutes |

This data demonstrates that while medications are somewhat buffered and take almost twice as long to breach the cold chain, they take four to five times longer to cool down to a safe temperature once power is restored [11]. This indicates that relying solely on the refrigerator's built-in probe can be misleading, as it may show a safe temperature long before the medications themselves have stabilized, creating a hidden risk.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental process and the key finding of the temperature lag.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers handling temperature-sensitive materials in parallel reactor experiments and downstream processing, having the right tools is essential for ensuring cold chain integrity.

Table 2: Essential Cold Chain Materials and Their Functions

| Item | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Validated Cold Chain Packaging | Pre-qualified shippers or containers that have been tested to maintain a specific temperature range for a defined duration, protecting contents during transport or temporary storage outside primary refrigeration [12]. |

| Specialized Medication Refrigerator | Pharmaceutical-grade units with calibrated, inbuilt temperature probes and alarms designed for stable temperature control, as opposed to household refrigerators which are not fit for this purpose [11]. |

| Calibrated Data Loggers (e.g., TempTale Ultra) | Independent, high-accuracy temperature monitoring devices that can be placed alongside or inside sensitive materials to provide a more accurate reading of the actual temperature experienced by the product [11]. |

| Battery Backup Systems | Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) for critical refrigerators and freezers to maintain operation during short-term power outages, provided they are regularly maintained [11]. |

| Sanggenol P | Sanggenol P, MF:C30H36O6, MW:492.6 g/mol |

| Tobramycin | Nebramycin Reagent|Antibiotic Complex|RUO |

Troubleshooting Common Temperature Excursions

Problem: Power outage or refrigerator mechanical failure.

- Immediate Action: Keep refrigerator doors closed. The internal temperature will often remain stable for a short period.

- Assessment: Use independent data loggers to determine the actual temperature and duration of the exposure experienced by the research materials, as the refrigerator's built-in probe may not be reliable [11].

- Prevention: Connect the refrigerator to a maintained battery backup system. Ensure the refrigerator undergoes regular scheduled maintenance [11].

Problem: Customs or shipping delays for imported temperature-sensitive reagents.

- Immediate Action: Utilize real-time monitoring to track the shipment's location and temperature. Contact the logistics provider to expedite clearance.

- Assessment: If a delay is anticipated, confirm the packaging's validated duration and have a contingency plan.

- Prevention: Pre-clear shipments where possible. Use shipping solutions validated for extended durations and establish contingency plans with alternate clearance routes [12].

Problem: Incorrect handling or packaging leading to internal temperature drift.

- Immediate Action: Upon receipt, immediately check the temperature indicator and transfer materials to a controlled environment.

- Assessment: If an excursion is confirmed, quarantine the materials and assess their stability based on available data.

- Prevention: Use qualified packaging and train all personnel on correct handling protocols, including proper conditioning of thermal packs and sealing of containers. Conduct stress tests with dummy shipments [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a temperature excursion for refrigerated pharmaceuticals? A1: For many institutions, a cold chain breach is defined as exposure to temperatures outside 2°C to 8°C for longer than 15 minutes. This guideline, originally for vaccines, is often adopted for all refrigerated medications in the absence of specific drug-level guidance [11].

Q2: If the refrigerator display shows the temperature is back to normal after a brief outage, are my research samples safe? A2: Not necessarily. The experimental data shows that while the refrigerator's air temperature may recover quickly (e.g., 17.5 minutes), the temperature of medications inside their packaging can take over an hour to return to a safe range [11]. Always consult independent data loggers placed with the samples before deeming them stable.

Q3: What are the hidden, micro-level threats to cold chain integrity? A3: Beyond obvious equipment failure, major risks include:

- Customs Delays: Shipments stuck in non-temperature-controlled warehouses [12].

- Last-Mile Delivery Delays: Packages left in non-controlled environments due to traffic or miscommunication [12].

- Packaging Failures: Incorrect conditioning of thermal packs, improper sealing, or mishandling by personnel [12].

Q4: Can a temperature excursion affect a drug's stability even if no visual changes are apparent? A4: Yes. Degradation from temperature exposure can involve chemical changes like protein denaturation or aggregation that are undetectable by visual inspection but can significantly reduce a product's potency and safety [11].

The logical relationships between the causes of temperature excursions, their hidden nature, and the ultimate consequences for research and patient safety are summarized in the following diagram.

Troubleshooting Guide: Temperature Control in Parallel Reactor Systems

This guide addresses common temperature control challenges encountered in parallel reactor research, providing targeted solutions to ensure data integrity and experimental reproducibility.

Q1: Why are the outlet temperatures across my parallel reactor streams not uniform, and how can I fix it?

Problem: Non-uniform outlet temperatures in parallel streams can lead to inconsistent reaction results, coke formation in high-temperature passes, and potentially dangerous tube rupture [13].

Solution: Implement a Difference Control Technique (DCT) to actively manage the temperature differences between streams [13].

- Root Cause: Uneven heating is often caused by disturbances in fuel gas pressure to individual burners or inherent flow maldistribution, creating a vicious cycle where a higher temperature leads to coking, which reduces flow and drives the temperature even higher [13].

- Actionable Protocol:

- Design Controllers: Implement a control system that regulates the temperature difference between pairs of reactor streams. For a four-reactor system, this involves controllers for the difference between streams 1 and 2 (C12) and streams 3 and 4 (C34) [13].

- Manipulate Inlet Flowrate: Use the petroleum inlet flowrate to each stream as the manipulated variable to control its temperature, decoupling this control loop from other system variables [13].

- Verify System Performance: This method provides effective decoupling from other control loops and does not require a high level of expertise to implement [13].

Q2: How can I maintain a precise gas feed distribution when the catalyst pressure drop changes during a long-term experiment?

Problem: Catalyst pressure drop or blockages that develop over time can disrupt the precision of gas feed distribution, especially in small-scale testing systems [14]. A higher inlet pressure in one reactor will reduce its feed supply while increasing flow to others [14].

Solution: Utilize a system equipped with individual Reactor Pressure Control (RPC) and a high-precision microfluidic flow distributor [14].

- Root Cause: Traditional systems that rely on physical flow restrictors (like capillaries) cannot automatically compensate for dynamic changes in reactor pressure drop [14].

- Actionable Protocol:

- Employ Microfluidic Distribution: Use a proprietary microfluidic distributor chip, which guarantees a flow distribution precision of < 0.5%RSD between channels, eliminating manual calibration of capillaries [14].

- Activate Reactor Pressure Control (RPC): The RPC module measures and precisely controls the individual pressure at each reactor's inlet. It uses a control valve at the reactor exit to compensate for pressure drop changes, ensuring all reactors maintain an equal inlet pressure [14].

- Monitor Pressure Data: Continuously record the pressure drop over each reactor. An increasing pressure drop provides early warning of potential catalyst plugging [14].

Q3: What is the maximum heating performance I can expect from a parallel reactor block, and how do reactor vessel properties affect it?

Problem: The maximum achievable temperature and the speed at which a reactor can be heated (ramping rate) are not universal; they depend on the reactor block's design, the type of reactor vessel, and the solvent volume [15].

Solution: Understand the performance specifications of your system and design experiments within its characterized limits.

- Root Cause: Different reactor materials (e.g., glass vs. stainless steel) and solvent volumes have varying thermal masses and heat transfer properties, which directly impact heating performance [15].

- Actionable Protocol:

- Select Appropriate Control Mode:

- Reference Characterized Performance: The table below summarizes key performance data from a characterization study of a parallel reactor system [15].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key metrics for heating performance and flow distribution precision derived from the cited experimental characterizations.

| Metric | Performance Value | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Heating Ramping Rate [15] | Up to +6 °C/min | Achievable in Heat/Cool Reactor mode across the system's full temperature range. |

| Max. Reactor-Circulator Temp. Difference [15] | +90 °C | For 50 mL - 150 mL glass and high-pressure reactors with adequate solvent volume. |

| Max. Reactor-Circulator Temp. Difference (Small Reactors) [15] | +80 °C | For a 16 mL high-pressure reactor with only 8 mL solvent volume. |

| Overall Reactor Temperature Range [15] | 80 °C | Possible between different reactors on the same block (e.g., from +10°C to +90°C above circulator). |

| Optimal Stable Ramping Rate [15] | +4 °C/min or lower | Provides greater stability and consistency with no significant overshoot. |

| Flow Distribution Precision [14] | < 0.5% RSD | Guaranteed between reactor channels using a microfluidic flow distributor chip. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Metrics

Protocol 1: Characterizing Maximum Heating Performance and Ramping Rates

This methodology is adapted from a study on a parallel reactor block [15].

- Objective: To determine the maximum temperature difference achievable between the reactor contents and the heating circulator, and to identify the maximum stable ramping rate.

- Materials:

- Parallel reactor block (e.g., PolyBLOCK 8) with multiple reactor positions.

- Heating circulator (e.g., Huber Unistat 430).

- Reactor vessels of varying materials (glass, SS316) and volumes (e.g., 16 mL, 50 mL, 150 mL).

- Solvent (e.g., Silicone oil Huber P20-275).

- Control software (e.g., labCONSOL).

- Procedure:

- Place different reactor types in the block positions as detailed in Table 1.

- Fill reactors with a defined volume of solvent and set stirring to a fixed rate (e.g., 400 rpm).

- In the software, execute a multi-step heating plan:

- Heat from 40°C to 120°C with a circulator temperature of 30°C.

- Set circulator to 60°C and reactor temperature to 70°C.

- Heat from 70°C to 150°C with a circulator temperature of 60°C.

- Set circulator to 90°C and reactor temperature to 100°C.

- Heat from 100°C to 180°C with a circulator temperature of 90°C.

- Test different ramping rates (e.g., +2°C/min, +4°C/min, +6°C/min) to assess stability and overshoot.

- Record the time taken for the reactor temperature to stabilize at each setpoint and the maximum temperature difference sustained between the reactor and the circulator.

Protocol 2: Implementing Difference Control for Outlet Temperature Uniformity

This method is based on an application in a preheat furnace with four parallel streams [13].

- Objective: To maintain identical outlet temperatures across multiple parallel reactor streams by controlling the difference in temperature between them.

- Materials:

- A multi-stream reactor or furnace system.

- Temperature sensors for each outlet stream.

- A control system (e.g., a Distributed Control System - DCS) capable of implementing difference controllers.

- Actuators to manipulate the inlet flowrate to each stream.

- Procedure:

- System Modeling: For a system with four streams, structure the control around difference controllers. The core idea is to regulate the difference between streams 1 & 2 and streams 3 & 4 [13].

- Controller Design: The control system should calculate the temperature difference between designated stream pairs (e.g., T1 - T2) and use a controller (like a PI controller) to adjust the inlet flowrate of one stream to drive this difference to zero [13].

- Implementation and Tuning: Apply the difference control system to the process. The design provides inherent decoupling, simplifying controller tuning, which can be done without requiring advanced expertise [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Microfluidic Flow Distributor Chip [14] | Provides high-precision distribution of a common gas feed to multiple parallel reactor channels, ensuring flow uniformity (<0.5% RSD) without manual calibration. |

| Reactor Pressure Control (RPC) Module [14] | Actively measures and controls individual reactor inlet pressures, compensating for catalyst pressure drop changes during long tests to maintain feed distribution precision. |

| Silicone Oil (e.g., Huber P20-275) [15] | A heat transfer fluid with a broad liquid phase temperature range, suitable for characterizing reactor heating performance across a wide temperature spectrum. |

| SS316 High-Pressure Reactors [15] | Metal reactors rated for high pressure (e.g., 200 bar), used for reactions requiring elevated pressures and characterized for their heating performance. |

| Glass Reactors with PTFE Lids [15] | Used for general synthesis and laboratory work at standard pressures; their heating and cooling dynamics are characterized against metal reactors. |

| Fursultiamine | Fursultiamine, CAS:10238-39-8, MF:C17H26N4O3S2.ClH |

| Huperzine C | Huperzine C, CAS:147416-32-8, MF:C15H18N2O, MW:242.32 g/mol |

Workflow Diagram: Achieving Temperature Stability & Uniformity

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving core temperature control challenges in parallel reactors, integrating the solutions discussed in this guide.

Modern Systems and Control Strategies for Robust Thermal Management

Within the broader context of a thesis on temperature control challenges in parallel reactor research, this technical support center addresses the core operational difficulties faced by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. A foundational challenge in this field is maintaining both accuracy (the closeness of a measured value to a known standard) and precision (the closeness of multiple measurements to each other) across all reactor channels [14]. The choice between stand-alone block reactors and circulator-assisted systems significantly impacts how these challenges are managed, especially concerning temperature uniformity and fluid distribution. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to support robust experimental outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of System Types

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the two main parallel reactor platform designs.

| Feature | Stand-Alone Blocks | Circulator-Assisted Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Core Operating Principle | Individual heating/cooling elements per reactor block. | Single central circulator distributes thermal fluid to all reactors. |

| Typical Temperature Range | Often limited by the built-in element's capacity. | Broad range, dependent on circulator and fluid capabilities [16]. |

| Temperature Uniformity | Risk of significant gradients between independent blocks. | Inherently higher; relies on fluid flow and system design for homogeneity [14]. |

| Complexity & Footprint | Higher per-reactor complexity; potentially larger footprint. | Centralized complexity (the circulator); often more compact reactor bank. |

| Key Vulnerability | Component failure in one block affects only that unit. | Circulator failure compromises the entire system. |

| Representative Example | Multi-block well-plate style systems. | Tubing-based reactor banks fed by a central thermal unit [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Problem 1: Poor Reproducibility Between Reactor Channels

Observed Symptom: High variance in reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, conversion) across different channels of the same parallel system, even under nominally identical set conditions.

Q: What are the most common root causes for poor inter-channel reproducibility?

- A: The primary causes often relate to uneven distribution of reaction conditions. Key factors to investigate are:

- Precision vs. Accuracy in Fluid Flow: Verify that the total fluid flow to the system is accurate (correct total volume) and that it is precisely distributed between reactors. A common design uses a microfluidic distributor chip to achieve a precision of < 0.5% RSD [14].

- Catalyst Bed Pressure Drop: If a catalyst is used, its packing can cause varying pressure drops in different reactors. This can disrupt the flow distribution in systems without individual pressure control, as a higher inlet pressure in one reactor will reduce its feed supply [14].

- Temperature Gradients: Ensure the thermal block or circulator fluid provides uniform heating/cooling to all reactor positions.

- A: The primary causes often relate to uneven distribution of reaction conditions. Key factors to investigate are:

Q: How can I troubleshoot a suspected flow distribution issue?

- A: Follow this experimental protocol:

- Calibration Check: Run a calibration experiment with a standard mixture or a non-reactive tracer through all reactor channels simultaneously.

- Analyze Output: Use your standard analytical method (e.g., HPLC) to measure the output concentration or flow rate from each channel.

- Calculate RSD: Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of the results across all channels. An RSD significantly higher than the system's specification (e.g., >0.5%) indicates a distribution problem.

- Inspect Hardware: Manually check for blockages in capillaries or distributor chips. In advanced systems, consult the individual reactor pressure drop records, which can provide clues about plugging behavior [14].

- A: Follow this experimental protocol:

Problem 2: Temperature Control Instability

Observed Symptom: Temperature readings fluctuate excessively or fail to reach the setpoint in one or more reactors, leading to inconsistent reaction kinetics.

Q: Why would temperature be unstable in a circulator-assisted system but stable in stand-alone blocks?

- A: Instability in a central circulator system points to issues with the thermal fluid loop. This can include:

- Air Bubbles: Bubbles trapped in the fluid circuit act as insulators and cause erratic temperature control.

- Low Fluid Level: Inadequate fluid volume reduces the system's thermal capacity and stability.

- Failing Pump: A weakening pump cannot maintain consistent fluid flow through all reactors.

- Faulty Valves: Malfunctioning control valves can cause improper fluid mixing or bypass.

- A: Instability in a central circulator system points to issues with the thermal fluid loop. This can include:

Q: What is a step-by-step method to verify temperature sensor accuracy?

- A: Implement this validation protocol:

- Independent Reference: Place a calibrated, traceable thermometer or thermocouple into a reactor vessel filled with a standard solvent.

- Setpoint Test: Set the reactor system to a series of target temperatures covering your typical operating range (e.g., 25°C, 50°C, 100°C).

- Equilibration and Measurement: Allow the system to stabilize at each setpoint. Record the reading from the independent reference sensor and compare it to the value reported by the reactor's internal sensor.

- Document Deviations: Note any consistent offsets or drifts. Calibrate the internal sensors if deviations exceed the required accuracy for your experiments (e.g., < ±0.5°C).

- A: Implement this validation protocol:

Problem 3: Reactor Channel Blockage

Observed Symptom: A sharp pressure increase in one channel, accompanied by zero or significantly reduced fluid flow.

Q: What is the safest procedure to unblock a reactor channel?

- A: A systematic and safe unblocking procedure is critical:

- System Depressurization: Isolate the affected channel and carefully release any built-up pressure.

- Disassembly: Remove the reactor from the block.

- Solvent Flushing: Attempt to flush the blockage with a strong solvent compatible with the system materials (e.g., DMF, DMSO, or aqueous acids/bases). Reverse flushing can be more effective.

- Ultrasonic Bath: If solvent flushing fails, place the disassembled reactor or its components in an ultrasonic bath for 10-15 minutes.

- Mechanical Clearing: As a last resort, use a fine, soft wire to carefully probe and clear the obstruction, taking extreme care not to scratch internal surfaces.

- A: A systematic and safe unblocking procedure is critical:

Q: How can I prevent blockages in future experiments?

- A: Proactive measures are key:

- Filtration: Always filter all liquid reagents and solutions before introducing them to the reactor system.

- In-Line Filters: Install appropriate in-line filters between the reagent reservoirs and the reactor inlet.

- System Monitoring: Use a platform that provides real-time pressure drop monitoring across each reactor, as this can provide early warning of plugging behavior before a complete blockage occurs [14].

- A: Proactive measures are key:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Microfluidic Flow Distributor Chip | A core component in advanced systems that precisely splits a common feed flow into multiple parallel streams with high accuracy (<0.5% RSD) [14]. |

| Individual Reactor Pressure Controller (RPC) | Actively measures and controls pressure at each reactor's inlet and outlet. It compensates for drifting pressure drops to maintain precise flow distribution and provides data on catalyst plugging [14]. |

| Mass Flow Controller (MFC) | Provides accurate total flow to the entire reactor system. It is the first step in ensuring correct reagent delivery [14]. |

| Chemical Tracers (for calibration) | Inert compounds used in validation experiments to measure system performance, such as flow distribution precision and mixing efficiency, without running an actual reaction. |

| In-line Filters | Placed before reactor inlets to remove particulates from reagents, preventing capillary or reactor blockages. |

| Thermal Calibration Standard | A calibrated thermometer or thermocouple used for the independent verification of the reactor system's temperature sensors. |

| Ibutilide | Ibutilide |

| Chlorphenesin Carbamate | Chlorphenesin Carbamate, CAS:126632-50-6, MF:C10H12ClNO4, MW:245.66 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: System Performance Validation

Before commencing critical research experiments, validate your parallel reactor platform's performance using this detailed methodology.

Objective: To quantitatively assess the precision (reproducibility) and accuracy (correctness of conditions) of all channels in a parallel reactor system.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare a standard solution of a non-reactive chemical tracer in a suitable solvent.

- System Priming: Load the solution into the reagent reservoir and prime the entire fluidic path.

- Experimental Run: Initiate the system to run the standard solution through all reactor channels simultaneously. Operate at a defined set of conditions relevant to your work (e.g., specific flow rate, temperature, and pressure).

- Sample Collection: Collect output from each reactor channel after the system has stabilized.

- Analysis: Analyze the samples using a calibrated analytical method (e.g., HPLC, GC) to determine the concentration of the tracer in each channel.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate Precision: Compute the mean and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of the tracer concentration across all channels. The RSD is a direct measure of the system's flow distribution precision.

- Assess Accuracy: Compare the mean measured tracer concentration to the known prepared concentration. The percent difference indicates the accuracy of the total fluid delivery system.

Workflow and System Diagrams

Parallel Reactor Platform Workflow

Troubleshooting Flow Distribution

Within the broader research on temperature control challenges in parallel reactor systems, selecting the appropriate heating mode is a fundamental decision that directly impacts experimental reproducibility, reaction efficiency, and scalability. The two primary control strategies—Constant Reactor Temperature and Heat/Cool Ramp profiles—serve distinct purposes and are suited to different experimental requirements. This guide provides a detailed comparison, supported by experimental data and troubleshooting protocols, to assist researchers in optimizing their temperature control parameters for more reliable and reproducible outcomes in pharmaceutical development and chemical synthesis.

Comparative Analysis: Control Modes at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of the two control modes, based on experimental characterization studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Temperature Control Modes

| Feature | Constant Reactor Temperature Mode | Heat/Cool Reactor Ramp Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Heats reactor contents to a specified setpoint as quickly as possible [17] | Changes the reactor temperature at a defined, controlled rate [17] |

| Heating Speed | Faster; reached 80°C in ~20 minutes in water studies (avg. ~4°C/min) [17] | Slower; took ~28 minutes to reach 80°C at 2°C/min [17] |

| Temperature Overshoot | Minimal overshoot observed [17] | More prone to overshoot without active cooling [17] |

| Best Application | Standard reactions where the final temperature is critical, and fast heat-up is desired | Temperature-sensitive reactions; processes requiring predictable, linear thermal profiles |

System Architecture and Experimental Protocols

A typical PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) temperature control system, common in advanced reactor blocks, consists of several key components working together [18]:

- Temperature Sensor: Measures the current process temperature (e.g., thermocouple, RTD) and provides feedback.

- PID Controller Unit: The "brain" that compares the sensor reading to the setpoint and calculates a corrective output using its algorithm.

- Actuator: The component that physically adjusts the heat input (e.g., heating element, cooling valve).

- Power Supply: Provides the electrical energy needed to run the controller and actuator.

The schematic below illustrates the logical flow of information and control within this system.

Characterizing Heating Performance: A Sample Experimental Methodology

The following protocol, adapted from a characterization study of the PolyBLOCK 8 parallel reactor block, provides a template for evaluating temperature control performance in your own system [17].

Objective: To characterize the temperature control capabilities of a parallel reactor block using different control modes and solvents.

Key Materials & Equipment:

- Parallel reactor block (e.g., PolyBLOCK 8) [17]

- Control software (e.g., labCONSOL) [17]

- Reactor vessels of different materials and volumes (e.g., 50-150 mL glass, 16-50 mL SS316) [17]

- Solvents covering a range of boiling points and heat capacities (e.g., Water, Methanol, Silicone Oil) [17]

- Active cooling unit (e.g., silicone oil circulator like Huber Unistat) [17]

- PTFE Rushton impellers (for glass) and SS316 anchor impellers (for metal reactors) [17]

Experimental Procedure:

- Setup: Place different reactor types in the block positions. Fill with a defined volume of solvent.

- Agitation: Set a constant stirring speed (e.g., 400 rpm via magnetic drive) [17].

- Plan Configuration:

- For Constant Reactor Mode: Program a step directly to the target temperature (e.g., 80°C).

- For Heat/Cool Ramp Mode: Program a ramp to the target temperature at a defined rate (e.g., 2°C/min).

- Data Collection: Execute the plan and use the software to record the actual reactor temperature over time.

- Analysis: Compare heat-up times, stability at setpoint, and presence of overshoot for the different modes and solvents.

Key Experimental Observations:

- The material and volume of the reactor had a negligible impact on temperature control performance [17].

- Attaching an active cooling circulator significantly reduced or eliminated temperature overshoots, especially in the ramp mode [17].

- Methanol (low boiling point) heated rapidly, while Silicone oil (wide operating range) allowed testing of higher setpoints [17].

Troubleshooting Common Temperature Control Issues

Problem: Temperature Overshoot in Ramp Mode

- Cause: The system's inherent thermal inertia is not compensated for during heating.

- Solution: Integrate an active cooling source (e.g., a silicone oil circulator). Studies show this can drastically reduce or eliminate overshoot [17].

Problem: Inconsistent Heating Between Reactor Positions

- Cause: Variations in stirring efficiency, sensor calibration, or block contact.

- Solution: Ensure uniform stirring and vessel placement. The characterization data showed high consistency across positions when the same plan was run [17].

Problem: Slow Heating Rate for High-Volume Reactions

- Cause: The power output of the heating block is insufficient for the thermal mass.

- Solution: Utilize the Constant Reactor Temperature mode, which is designed to apply maximum power to reach the setpoint as quickly as possible [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a Heat/Cool Ramp over Constant Reactor Temperature?

- Use a ramp profile when your reaction or reactants are sensitive to rapid temperature changes, or when your experimental protocol requires a predictable, linear temperature increase (e.g., mimicking specific process conditions). The Constant Reactor mode is best for achieving a stable target temperature in the shortest time [17].

Q2: How does active cooling improve my temperature control?

- Active cooling is crucial for mitigating temperature overshoot by quickly removing excess heat. It is particularly important for achieving accurate control in ramp modes and for processes requiring rapid cool-downs [17].

Q3: Are my results transferable between different reactor types (e.g., glass vs. metal)?

- Experimental data suggests that temperature control performance is largely unaffected by reactor material or volume. This indicates that reaction temperature profiles can be reliably scaled between different reactor setups [17].

Q4: What is the role of PID in these control modes?

- The PID controller is the logic behind the modes. It continuously calculates the difference between the setpoint and measured temperature, then adjusts the power to the heater (and cooler) to minimize this error. The "P," "I," and "D" terms determine how aggressively and steadily the system responds [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Temperature Control Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Silicone Oil (e.g., Huber P20-275) | High-boiling solvent for testing high-temperature setpoints; wide operating range [17]. |

| Methanol | Low-boiling point solvent (64.7°C) for testing low-temperature control and system responsiveness [17]. |

| Deionized Water | A common, safe, and polar solvent for general system characterization and baseline performance tests [17]. |

| Silicone Oil Circulator (e.g., Huber Unistat) | Provides active cooling to eliminate temperature overshoot and enables rapid cooling phases [17]. |

| PTFE Rushton Impellers | Provide efficient mixing in glass reactors, ensuring homogenous temperature distribution [17]. |

| SS316 Anchor Impellers | Used for mixing in metal (SS316) high-pressure reactors [17]. |

| Plantaricin A | Plantaricin A, CAS:131463-18-8, MF:C46H75N11O14S, MW:1038.2 g/mol |

| Dimeric coniferyl acetate | Dimeric coniferyl acetate, CAS:184046-40-0, MF:C24H26O8 |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Microtiter Plate Assays

This section addresses common experimental challenges encountered when working with microtiter plates, with a specific focus on temperature control issues relevant to parallel reactor research.

Problem: High Background Signal

High background noise can obscure true signals and compromise data accuracy in high-throughput screening.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Temperature Control Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient washing [19] [20] | Increase wash steps and ensure complete fluid removal by inverting the plate and tapping forcefully [20]. | Ensure wash buffers are at the correct, consistent temperature to prevent protein re-binding. |

| Non-specific antibody binding [19] [21] | Use a suitable blocking buffer (e.g., BSA, casein, or serum) and ensure a proper block step is included [19] [21]. | Blocking efficiency can be temperature-dependent; follow incubation temperature protocols precisely. |

| Substrate contamination or light exposure [20] [22] | Prepare substrate immediately before use, protect from light, and use fresh solutions [20]. | Contaminating enzymes may have different temperature optima, exacerbating background. |

| Incomplete reaction stopping [19] [21] | Read the plate immediately after adding the stop solution to prevent continued color development [19]. | Reaction kinetics are temperature-dependent; delayed reading at room temperature can increase background. |

Problem: High Variation Between Replicates

Poor reproducibility between technical replicates makes data unreliable and statistical analysis difficult.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Temperature Control Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Pipetting errors [19] [21] | Use calibrated pipettes, manufacturer-recommended tips, and proper technique. Visually check volumes [21]. | Temperature affects liquid viscosity and evaporation, influencing pipetting accuracy. |

| Inconsistent incubation temperature [19] [20] | Avoid stacking plates during incubation to ensure uniform heat distribution. Use a calibrated incubator [20]. | This is a direct parallel to temperature distribution challenges in parallel reactor systems. |

| Incomplete or inconsistent washing [20] [22] | Use an automated plate washer or standardized manual technique. Add soak steps to improve removal of unbound material [20]. | |

| Edge effects [19] [20] | Seal plates completely with a fresh sealer during incubations. Use a uniform room temperature surface [19]. | Caused by uneven temperature across the plate, directly mirroring thermal gradient issues in multi-reactor arrays. |

Problem: Weak or No Signal

A weak signal can lead to false negatives and reduces the dynamic range of an assay.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Temperature Control Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents not at room temperature [20] | Allow all reagents to sit on the bench for 15-20 minutes before starting the assay [20]. | Cold reagents can slow initial reaction kinetics, reducing binding events during fixed incubation times. |

| Incorrect plate reader settings [19] [23] | Ensure the plate reader is set to the correct wavelength and that the focal height is optimized [19] [23]. | |

| Expired or improperly stored reagents [20] | Confirm expiration dates and storage conditions (typically 2-8°C). Do not use expired reagents [20]. | Temperature fluctuations during storage degrade reagent stability, a key concern for any sensitive material. |

| Capture antibody didn't bind to plate [20] | Ensure an ELISA plate (not a tissue culture plate) is used. Verify coating buffer and incubation conditions [20]. | Antibody adsorption during plate coating is a temperature- and time-sensitive process. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the critical factors for minimizing edge effects in microtiter plates, and how do they relate to parallel reactor design?

Edge effects, where outer wells behave differently from inner wells, are often caused by temperature gradients and evaporation [19] [20]. To minimize them:

- Do not stack plates during incubation to ensure uniform heat distribution [19].

- Seal the plate completely with a plate sealer to prevent evaporation [20].

- Use a uniform, temperature-stable surface and ensure the incubator is properly calibrated [19].

> > Temperature Control Parallel: This is a direct analog to maintaining uniform temperature across multiple miniature reactors in a parallel system. In both setups, inconsistent thermal profiles lead to variable reaction kinetics and poor data quality.

Q2: How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio in a fluorescent microplate assay?

- Optical Settings: Use the appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths and a high number of flashes per measurement to reduce variability [23].

- Blocking: Use an effective blocking buffer to reduce non-specific binding (noise) [19].

- Washing: Implement thorough and consistent washing protocols to remove unbound reagent [20] [22].

- Well-Scanning: For unevenly distributed samples (e.g., adherent cells), use the plate reader's well-scanning function (orbital or matrix) instead of a single point measurement to get a more representative signal [23].

Q3: Our assay results are inconsistent from day to day. What should I investigate?

Day-to-day variation often stems from environmental or procedural inconsistencies.

- Reagent Temperature: Always pre-equilibrate all reagents to room temperature before starting the assay [20].

- Incubation Timers: Strictly adhere to recommended incubation times; use a calibrated timer.

- Reagent Preparation: Double-check calculations and pipetting when preparing dilutions. Use fresh standard curve dilutions each time [19] [20].

- Instrument Calibration: Regularly check the calibration of pipettes, incubators, and plate readers.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validating a Robust Microplate-based ELISA

This protocol is essential for ensuring your assay provides reliable data before committing valuable screening samples.

Key Materials:

- Microplate: 96-well ELISA plate (not tissue culture plate) [20].

- Blocking Buffer: e.g., Protein-based blocker like StabilGuard, BSA, or casein [19] [21].

- Wash Buffer: PBS or TBS with a detergent like Tween-20 [21].

- Plate Reader: A calibrated microplate reader capable of absorbance (e.g., 450 nm for TMB substrate) [20].

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the core steps of a sandwich ELISA protocol, highlighting stages where temperature control is most critical.

Detailed Steps:

- Plate Coating: Dilute capture antibody in a recommended buffer (e.g., PBS). Add to wells and incubate overnight at 4°C or as optimized [21].

- Blocking: Aspirate coating solution. Add blocking buffer (e.g., 5-10% BSA) and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature to cover any remaining protein-binding sites [21].

- Assay Run: Following the workflow above:

- Sample/Standard Incubation: Add samples and standards to wells. Incubate at the specified temperature (e.g., 37°C or room temp) for the recommended time. This is a critical temperature-sensitive binding step.

- Washing: Wash wells 3-4 times with wash buffer. Invert the plate and tap firmly on absorbent paper to remove residual liquid [20].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add the detection antibody. Incubate as per step 3a. This is another critical temperature-sensitive step.

- Washing: Repeat the washing procedure.

- Substrate Incubation: Add enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB). Incubate in the dark for the exact time specified. Color development kinetics are highly temperature-dependent.

- Stop and Read: Add stop solution (e.g., acid) and read the absorbance immediately on a plate reader [19] [20].

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Miniaturized Reaction in a 384-Well Format

This protocol outlines the process for transitioning an assay to a higher-density format to increase throughput.

Key Materials:

- Microplate: 384-well plate (color chosen for detection mode: white for luminescence, black for fluorescence) [23].

- Liquid Handler: Automated or manual pipette capable of accurately dispensing low volumes (1-50 µL).

- Plate Reader: A reader capable of measuring from 384-well plates, ideally with auto-focus and well-scanning capabilities [23].

Workflow: The process of assay miniaturization requires careful attention to liquid handling and environmental control to ensure reproducibility.

Detailed Steps:

- Establish Robust 96-Well Assay: Before miniaturization, ensure the assay is robust in a 96-well format. Calculate the Z'-factor; a value between 0.5 and 1.0 indicates an excellent assay for screening [24].

- Reaction Mixture: In a master mix tube, combine all reaction components except the test compound or variable agent. This ensures consistency and reduces pipetting error. Keep the mixture on ice or at room temperature as required by the protocol.

- Plate Dispensing:

- Use a liquid handler or calibrated multichannel pipette to dispense the master mix into the 384-well plate. The recommended fill volume is typically one-third of the maximum well volume to prevent meniscus effects and cross-contamination [23].

- Add the test compounds or variable agents. Use tips with aerosol filters to prevent contamination [22].

- Initiation and Incubation:

- Gently centrifuge the plate to bring all liquid to the bottom and remove bubbles.

- Seal the plate with an optical plate sealer to prevent evaporation.

- Incubate at the precise temperature required for the reaction. The small volumes make the assay highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, akin to miniature reactors.

- Detection:

- Read the plate using the appropriate detection mode (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence).

- For uneven samples, use the plate reader's well-scanning function (orbital or matrix) instead of a single center-point read to improve data accuracy [23].

- Analyze the data, checking the coefficient of variation (CV) between replicates. A CV of less than 10% is typically desirable.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used to optimize microtiter plate assays and overcome common challenges.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Stabilizers & Blockers (e.g., StabilCoat, StabilGuard) [19] | Minimize non-specific binding (background) and stabilize dried capture proteins on the plate surface over time. | Essential for reducing false positives and extending assay shelf-life. Choice of blocker (BSA, casein) can affect specific assays [21]. |

| Sample/Assay Diluents (e.g., MatrixGuard) [19] | Provide an optimal matrix for diluting standards and samples, reducing matrix interferences and the risk of false positives. | Using a diluent that matches the standard curve matrix minimizes dilutional artifacts and improves recovery [22]. |

| TMB Substrate | A chromogenic substrate for Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) enzyme, producing a blue color that turns yellow when stopped. | The reaction is time- and temperature-sensitive. Use a clear, colorless substrate immediately before use and stop the reaction promptly [19] [20]. |

| Plate Sealers | Adhesive films used to cover plates during incubation steps. | Prevent evaporation, contamination, and well-to-well cross-talk. Use a fresh sealer each time the plate is opened; reusing sealers can introduce contaminants and cause variability [19] [20]. |

| Wash Buffers | Typically phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or tris-buffered saline (TBS) with a mild detergent (e.g., Tween-20). | Removes unbound reagents and decreases background. Incomplete washing is a primary cause of high background and poor replicate data [20] [21]. |

| Peimine | Peimine, CAS:135636-54-3, MF:C27H45NO3, MW:431.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Des-Gly10,D-Ala6,Pro-NHEt9)-LHRH | (Des-Gly10,D-Ala6,Pro-NHEt9)-LHRH, CAS:148029-26-9, MF:C56H78N16O12, MW:1167.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Temperature is one of the most critical operating parameters in bioprocesses, exerting a profound influence on microbial growth rates, enzyme activity, and product formation. In parallelized bioreactor systems, which are increasingly used to accelerate bioprocess development, maintaining precise and uniform temperature control across all reactors presents significant technical challenges. The temperature optimum can vary substantially within a single microbial or enzymatic system, differing for growth versus product formation, or for enzyme activity versus stability [25]. Effective temperature profiling and control strategies are therefore essential for optimizing these complex biological systems, particularly when scaling from milliliter-scale screening experiments to production-scale bioreactors.

Core Principles of Bioprocess Temperature Optimization

Fundamental Kinetic Relationships

Temperature affects bioprocesses through its direct impact on enzyme kinetics and catalyst stability. The relationship between temperature and reaction rates typically follows Arrhenius-type behavior, with reaction rates increasing with temperature until a critical point is reached where enzyme deactivation occurs. For processes with parallel deactivation of enzymes, optimal temperature control must balance the activation energies of the desired reaction against those leading to catalyst deactivation [26]. Mathematical modeling of these relationships enables the determination of stationary optimal temperature profiles that minimize process duration while maximizing conversion or yield.

Challenges in Parallel Reactor Systems

Parallel bioreactor systems introduce specific temperature control challenges that differ from single-reactor operations. These include:

- Heat transfer limitations at small scales (mL-volume) where surface-to-volume ratios are high

- Cross-reactor temperature gradients due to positioning within incubation units

- Metabolic heat generation variations between reactors with different biological content

- Evaporative cooling effects that become more significant at small scales

- Integration of monitoring systems that can track temperature in real-time across multiple reactors

These challenges necessitate specialized equipment and methodologies to ensure that temperature remains a controlled variable rather than an uncontrolled source of experimental variation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Temperature Control Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent performance between parallel reactors | Temperature gradients across reactor block, uneven heat distribution, varying evaporation rates [25] | Validate temperature uniformity across all positions using fluorescence thermometry; implement reactor randomization strategies; use sealing films to minimize evaporation differences |

| Premature decline in enzyme activity or microbial growth | Temperature-induced catalyst deactivation, denaturation of enzymes at elevated temperatures [26] | Determine optimal temperature profile that balances reaction rate against deactivation; implement temperature profiling to identify stability thresholds; consider thermal-tolerant enzyme variants |

| Irreproducible reaction kinetics between runs | Inaccurate temperature sensors, sensor drift over time, improper calibration [27] [28] | Implement quarterly sensor calibration with NIST-traceable standards; replace sensors showing drift >±0.5°C; use redundant sensor systems for critical applications |

| Unexpected metabolic shifts or byproduct formation | Suboptimal temperature conditions stressing microbial systems, temperature-induced regulatory changes [25] | Perform comprehensive temperature profiling to identify optimal ranges for both growth and product formation; monitor metabolic byproducts at different temperatures |

| Contamination correlated with temperature changes | Temperature excursions promoting contaminant growth, compromised seals under thermal cycling [29] | Validate sterilization cycles at actual operating temperatures; replace O-rings and seals regularly (every 10-20 cycles); implement strict aseptic procedures during inoculation |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most accurate method for temperature measurement in microtiter plate-based screening?

A: Fluorescence thermometry using a combination of Rhodamine B and Rhodamine 110 provides highly accurate, well-resolved temperature measurements. This method involves adding these fluorescent dyes to each well and calibrating the fluorescence ratio against known temperatures. The technique offers superior spatial resolution compared to infrared methods and can be integrated with commercial online monitoring systems like the BioLector [25].

Q2: How can I identify whether temperature gradients are affecting my parallel reactor results?

A: Conduct a temperature mapping study by placing calibrated sensors in multiple reactor positions under normal operating conditions. For microtiter plates, use fluorescence thermometry to simultaneously measure temperature across all wells. Significant deviations (>0.5°C) indicate problematic gradients. Additionally, running identical biological controls in different positions can reveal position-dependent performance variations [25].

Q3: What temperature control strategy is most effective for enzymes subject to parallel deactivation?

A: Implement an optimal temperature profile that begins at upper temperature constraints to maximize initial reaction rates, then follows a stationary optimal trajectory, and potentially ends at lower temperature constraints to preserve enzyme activity during later stages. This approach minimizes process duration while maintaining high conversion levels [26].

Q4: How often should temperature sensors be calibrated in bioreactor systems?

A: For research-grade systems, quarterly calibration is recommended using NIST-traceable standards at 3-4 critical set points spanning your typical operating range. Sensors showing drift exceeding ±0.5°C should be replaced immediately. Additionally, validation should be performed after any maintenance or system modifications [28].