Principles of High-Throughput Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerating Reaction and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the core principles and advanced methodologies of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) for reaction and drug discovery.

Principles of High-Throughput Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Accelerating Reaction and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the core principles and advanced methodologies of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) for reaction and drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of HTS, including automation, miniaturization, and assay design. It delves into diverse screening approaches—from target-based to phenotypic—and offers practical strategies for assay optimization, robust statistical hit selection, and troubleshooting common pitfalls like false positives. Finally, the guide details rigorous hit validation protocols using counter, orthogonal, and comparative assays to ensure the selection of high-quality leads for further development, synthesizing these elements to highlight future directions in the field.

What is High-Throughput Screening? Core Concepts and Evolution

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a rapid assessment approach that utilizes robotic, automated, and miniaturized assays to quickly identify novel lead compounds from large libraries of structurally diverse molecules [1]. It represents a foundational methodology in modern drug discovery and reaction research, enabling the testing of thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds per day to accelerate the identification of promising chemical starting points [2] [1].

Core Principles and Key Aspects of HTS

The power of HTS stems from the integration of several core technological and methodological components. The process is designed to manage immense complexity while delivering reproducible and reliable data.

Automation and Robotics

At the heart of any HTS system is automation. Automated liquid-handling robots are capable of low-volume dispensing of nanoliter aliquots of sample, which minimizes assay setup times and provides accurate, reproducible liquid dispensing [1]. Modern systems are designed for remarkable versatility and reliability, accommodating both cell and biochemical assays and often functioning continuously for 20-30 hours [2]. Precision dispensing technologies, such as acoustic dispensing, ensure highly accurate compound delivery, which is critical for assay performance and data quality [2].

Assay Development and Miniaturization

HTS assays must be robust, reproducible, and sensitive to be effective [1]. A critical aspect of their design is suitability for miniaturization into 96-, 384-, and 1536-well plate formats, which drastically reduces reagent consumption and cost [1]. These assays undergo rigorous validation according to pre-defined statistical concepts to ensure their biological and pharmacological relevance before being deployed in a full-scale screen [1].

Compound Management and Library Design

The quality of an HTS output is intrinsically linked to the quality of the input. Compound libraries are crucial for generating high-quality starting points for drug discovery [2]. These libraries are stored in custom-built facilities with controlled low humidity and ambient temperature to ensure compound integrity [2]. Library design involves careful curation to insure chemical diversity and quality, often judged by filters such as the Rapid Elimination of SWILL (REOS) or Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filters [3]. Typical industrial screening libraries contain 1-5 million compounds, while academic libraries are often around 0.5 million compounds [3].

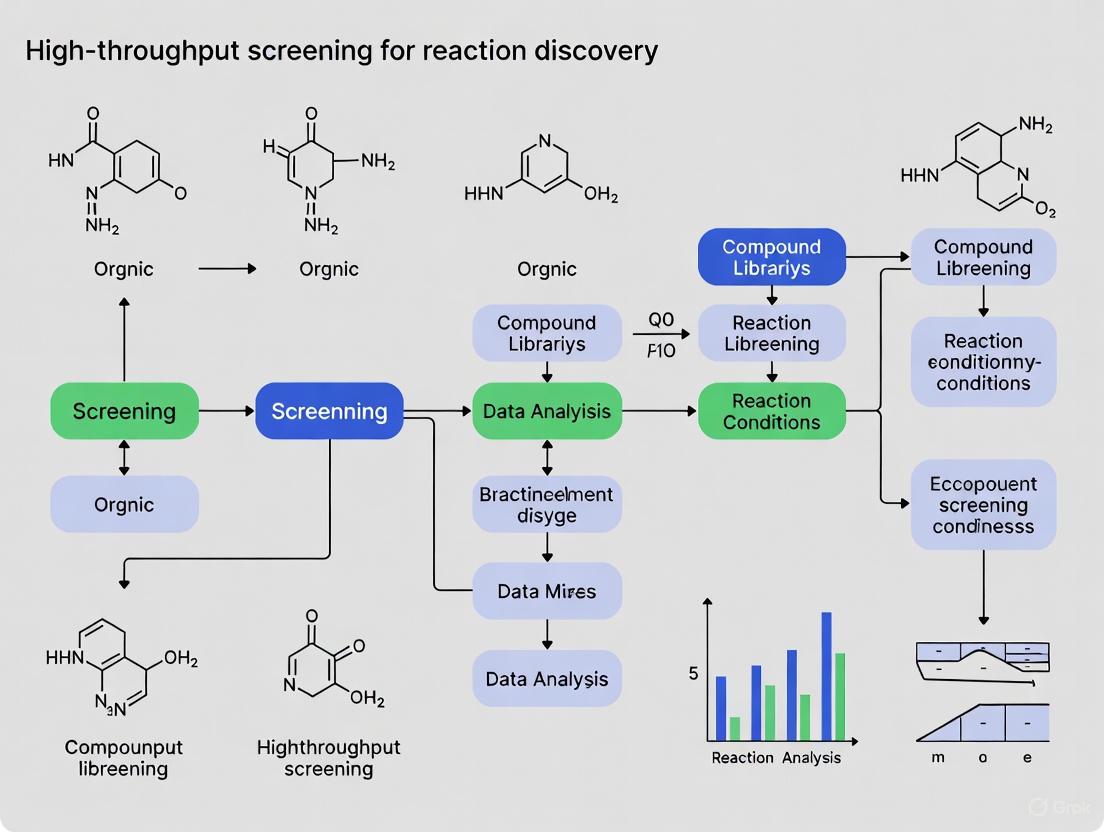

The HTS Workflow: From Assay to Hit

The HTS process is a multi-stage workflow designed to efficiently sift through vast chemical libraries to identify credible "hits" – compounds that show a desired effect on the target. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision points within a standard HTS workflow.

Stages of the HTS Workflow

Assay Development and Validation: The process begins with the development or transfer of a biologically relevant assay [2]. This assay is then meticulously validated in a pilot screen to test automation performance, reproducibility, and to provide an early estimate of hit rates. A common metric for this is the robust Z' factor, which quantifies the assay's quality and suitability for HTS [2].

Primary Screening: In the primary screen, each compound in the library is tested at a single concentration [2]. This phase is designed for speed and efficiency, rapidly surveying the entire chemical library to identify any compound that shows a signal above a predefined threshold.

Hit Confirmation and Cheminformatic Triage: The initial actives from the primary screen are subjected to a first cheminformatic triage [2]. This critical step uses computational tools to identify and filter out compounds likely to be false positives, such as pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) or promiscuous bioactive compounds [3]. This step requires expertise in medicinal chemistry and cheminformatics to prioritize the more promising chemical matter for follow-up [3].

Hit Profiling and Counter-Screening: The remaining potential hits are then profiled further. This involves testing in counter-screens and orthogonal assays designed to rule out non-specific effects or activity against unrelated targets [2] [1]. Confirmed hits are then advanced to potency assessments, where concentration-response curves (e.g., IC50 or EC50 values) are generated to quantify their activity [2].

Hit Validation and Prioritization: Compounds that advance to this final stage undergo additional quality control processes, such as analytical chemistry checks (e.g., LCMS) to verify compound identity and purity [2]. The final output is a curated list of validated hits with confirmed potency and structure, which serve as the starting points for further medicinal chemistry optimization [2] [3].

Detection Technologies and Data Analysis

HTS assays can be broadly subdivided into biochemical (cell-free) and cell-based methods, each with its own suite of detection technologies [1].

Detection Methodologies

- Biochemical Assays: These typically utilize purified targets like enzymes or receptors [1]. A common example is an enzyme inhibition assay, which might use a peptide substrate coupled to a fluorescent leaving group to quantify activity [1].

- Cell-Based Assays: These use whole cells to evaluate a compound's effect in a more physiologically complex environment. They can measure phenotypes like cell viability, reporter gene expression, or changes in second messengers [1].

- Emerging Methods: Mass spectrometry (MS)-based methods for unlabeled biomolecules are becoming more common, allowing for the direct detection of reaction products [1]. Techniques like Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) monitor changes in protein thermal stability upon ligand binding, which can indicate direct target engagement [1].

Data Management and Analysis

One of the fundamental challenges in HTS is the generation of false positive data, which can arise from assay interference, chemical reactivity, autofluorescence, or colloidal aggregation [1]. To address this, robust data analysis pipelines are essential.

- Software Platforms: HTS facilities leverage integrated informatics platforms and specialized software like Genedata Screener for processing, managing, and analyzing the large, complex datasets generated [2]. Plate barcodes are typically integrated with sample ID data to guarantee data fidelity [2].

- Triage Methods: Statistical quality control methods and machine learning (ML) models trained on historical HTS data are used to identify and rank HTS output, classifying compounds by their probability of success [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, technologies, and materials essential for executing a successful HTS campaign.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials in HTS

| Item/Reagent | Function & Application in HTS |

|---|---|

| LeadFinder Diversity Library [2] | A pre-designed, diverse collection of ~150,000 compounds with lead-like properties, used as a primary source for identifying novel chemical starting points. |

| Microplates (96 to 1536-well) [1] | Miniaturized assay platforms that enable high-density testing and significant reduction in reagent and compound consumption. |

| Fluorescence & Luminescence Kits [1] | Sensitive detection reagents used in a majority of HTS assays due to their high sensitivity, ease of use, and adaptability to automated formats. |

| Echo Acoustic Dispenser [2] | Non-contact liquid handling technology that uses sound energy to transfer nanoliter volumes of compounds with high accuracy and precision. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LCMS) [2] | An analytical chemistry technique used for rigorous quality control of compound library samples and for confirming the identity and purity of final hit compounds. |

| Genedata Screener Software [2] | A robust data analysis platform specifically designed for processing, managing, and interrogating large, complex HTS datasets. |

| Titian Mosaic SampleBank Software [2] | A compound management system that streamlines the ordering and tracking of assay plates, integrated with automated storage for efficient library management. |

Advanced Concepts: Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS)

Pushing the boundaries of throughput, Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS) can achieve throughputs of over 300,000 compounds per day [1]. This requires significant advances in microfluidics and the use of very high-density microwell plates with volumes as low as 1–2 µL [1]. The table below compares the key attributes of HTS and uHTS.

Table 2: Comparison of HTS and uHTS Capabilities [1]

| Attribute | HTS | uHTS | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (assays/day) | < 100,000 | >300,000 | uHTS is significantly faster. |

| Complexity & Cost | High | Significantly Greater | uHTS entails more complex instrumentation and higher costs. |

| Data Analysis Needs | High | Very High | uHTS may require AI to process its larger datasets. |

| Ability to Monitor Multiple Analytes | Limited | Limited | Both require miniaturized, multiplexed sensor systems for this capability. |

| False Positive/Negative Bias | Present | Present | uHTS does not inherently offer enhancements in reducing false results. |

High-Throughput Screening stands as a cornerstone technology in modern reaction discovery and drug development. By integrating automation, miniaturization, sophisticated data analysis, and high-quality compound libraries, HTS enables the systematic and rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces. Its success is not merely a function of scale but depends on a rigorous, multi-stage workflow designed to triage and validate true hits from a sea of potential artifacts. As technologies advance towards uHTS and incorporate more artificial intelligence, the principles of robust assay design, expert chemical triage, and data-quality focus will continue to underpin the effective application of HTS in scientific research.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) serves as an indispensable engine in modern drug discovery and reaction discovery research, enabling the rapid evaluation of thousands to millions of chemical compounds against biological targets. The power of contemporary HTS rests on three interdependent technological pillars: robotics and automation for precision and reproducibility, miniaturization for efficiency and scale, and sensitive detection for data quality and biological relevance. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core principles, detailing their implementation, synergy, and critical role in advancing discovery research.

Robotics and Automation: The Workhorse of HTS

Robotic systems form the backbone of HTS operations, transforming manual, low-throughput processes into industrialized, automated workflows. The primary objective is unattended, walk-away operation that maximizes throughput while minimizing human error and variability [4].

System Architecture and Key Components

A fully integrated robotic screening system, such as the one implemented at the NIH's Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), is designed for maximal efficiency and flexibility [4]. Its core components include:

- Robotic Arms: High-precision anthropomorphic arms (e.g., Stäubli) transport plates between system modules.

- Random-Access Plate Storage: Carousels provide on-line storage for thousands of assay and compound plates, enabling true random access for diverse screening protocols.

- Liquid Handling Systems: Multifunctional dispensers using solenoid valve technology handle reagents and compounds with high precision. A 1,536-pin array enables rapid compound transfer for high-density formats.

- Environmental Control: Multiple incubators with independent control of temperature, humidity, and COâ‚‚ are essential for cell-based assays.

- Detection Units: A variety of microplate readers (e.g., ViewLux, EnVision) are integrated to support diverse detection signals.

Enabling Quantitative HTS (qHTS)

The NCGC system was pivotal in pioneering the quantitative HTS (qHTS) paradigm [4]. Unlike traditional single-concentration screening, qHTS tests each compound across a range of seven or more concentrations, generating concentration-response curves (CRCs) for the entire library. This approach:

- Mitigates false positives and negatives common in single-point screens.

- Provides immediate data on compound potency and efficacy.

- Reveals complex biological responses through curve shape analysis. This robust, automated infrastructure has enabled the generation of over 6 million CRCs from more than 120 assays, demonstrating the transformative power of robotics in expanding the scope and quality of screening data [4].

Miniaturization: The Drive for Efficiency

Miniaturization is the practice of downsizing assay volumes to increase throughput and reduce reagent consumption, particularly those that are expensive or precious [5] [6]. It is a continually evolving, historical process that follows the progress of technology [5].

The Evolution of Assay Formats

The transition from 96-well to 384-well and 1536-well plate formats represents the standard trajectory of HTS miniaturization [7] [6]. The 1,536-well format is widely considered the next evolutionary step for primary screening assays, offering a 16-fold reduction in volume and reagent use compared to the 96-well standard [5]. This progression is driven by the need to screen increasingly large compound libraries efficiently.

Benefits and Quantitative Impact

The advantages of miniaturization are both economic and practical, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Impact of Assay Miniaturization

| Factor | 96-Well Format (Traditional) | 384-Well Format (Miniaturized) | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Usage (Example: iPSC-derived cells) | ~23 million cells for 3,000 data points [6] | ~4.6 million cells for 3,000 data points [6] | ~80% reduction in cell use, saving approximately $6,900 per screen [6] |

| Theoretical Throughput | Baseline | 4x higher than 96-well | Higher data output per unit time |

| Reagent Consumption | High | Significantly lower | Major cost savings, especially for expensive enzymes and antibodies [8] [6] |

Technical Challenges and Solutions

Miniaturization introduces specific technical challenges that require careful management:

- Liquid Handling: Precision is paramount. Issues such as tip clogging, high dead volume, and cross-contamination must be addressed with advanced acoustic dispensing and pressure-driven nanoliter dispensing systems [9].

- Evaporation: Small volumes are highly susceptible to evaporation, leading to edge-effects and variability. Proper use of sealed plates or humidity-controlled environments is critical [6].

- Biology in Small Volumes: Cell-based assays face added challenges in miniaturized formats, including uneven cell distribution, poor viability, and imaging artifacts. These require optimized assay conditions and specialized plates [6].

Sensitive Detection: The Key to Quality Data

Sensitive detection refers to an assay's ability to detect minimal biochemical changes, which directly determines the quality, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness of a screen [8]. It is the foundation for generating biologically relevant and reliable data.

The Critical Role of Assay Sensitivity

High sensitivity in detection provides multiple interconnected advantages:

- Reduced Reagent Consumption: Sensitive assays can detect product formation at low substrate turnover, allowing researchers to use up to ten times less enzyme than less sensitive methods. This can save tens of thousands of dollars in reagent costs for a single screen [8].

- Accurate Potency Determination (ICâ‚…â‚€): The accurate measurement of a compound's potency relies on keeping the enzyme concentration close to the inhibitor's ICâ‚…â‚€. High-sensitivity assays enable the use of low enzyme concentrations without compromising signal, allowing for accurate determination of sub-nanomolar ICâ‚…â‚€ values, which is vital for ranking compound potency [8].

- Physiologically Relevant Conditions: Sensitive assays enable experiments under initial-velocity conditions (substrate concentrations at or below the enzyme's Km), preserving authentic enzyme kinetics and generating more biologically meaningful data [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Low vs. High-Sensitivity Assays

| Factor | Low-Sensitivity Assay | High-Sensitivity Assay (e.g., Transcreener) |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Required | 10 mg | 1 mg |

| Cost per 100,000 wells | Very High | Up to 10x lower |

| Signal-to-Background | Marginal | Excellent (>6:1) |

| Ability to run under Km | Limited | Fully enabled |

| ICâ‚…â‚€ Accuracy | Moderate | High |

Detection Technologies and Metrics

A wide range of fluorescence-based detection technologies are available, each with unique advantages. These include fluorescence polarization (FP), time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET), fluorescence intensity (FI), and AlphaScreen [4] [10]. The performance of these technologies is quantified using key metrics:

- Z'-factor: A statistical measure of assay quality and robustness. Values between 0.5 and 1.0 indicate an excellent assay [8] [7].

- Signal-to-Background (S/B) Ratio: The difference between positive and negative control signals. A higher ratio indicates better detection capability [8].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest product concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background. For example, advanced HTS methods for virus detection can achieve an LOD of 10â´ genome copies per mL or lower [11].

Integrated Workflow and the Scientist's Toolkit

The three pillars of HTS are not isolated; they function as an integrated system. The following diagram and table outline a generalized HTS workflow and the essential tools that enable it.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Item | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (384-/1536-well) | The miniaturized vessel for hosting reactions. Choosing the right plate is critical for success, impacting evaporation, optical clarity, and cell adherence [6]. |

| Universal Biochemical Assays (e.g., Transcreener) | Antibody-based detection kits for common products (e.g., ADP, GDP). They offer flexibility across diverse enzyme classes (kinases, GTPases, etc.) and high sensitivity for low reagent consumption [8] [7]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Reagents | Include reporter molecules, viability indicators, and dyes for high-content imaging. Enable phenotypic screening in 2D or 3D culture systems [9] [7]. |

| qHTS Concentration-Response Plates | Pre-spotted compound plates with a serial dilution of each compound. They are fundamental for generating concentration-response curves in primary screening without just-in-time reformatting [4]. |

| Control Compounds | Well-characterized agonists/antagonists and inactive compounds. They are essential for normalizing data (% activity), calculating Z'-factor, and validating assay performance in every plate [12]. |

| Adenosine monophosphate | High-Purity Adenosine 5'-Monophosphate for Research |

| Fortical | Fortical (Calcitonin-salmon) |

The synergy between advanced robotics, relentless miniaturization, and highly sensitive detection defines the cutting edge of high-throughput screening. Robotics provides the unwavering precision and capacity required for complex paradigms like qHTS. Miniaturization delivers the radical efficiency necessary to sustainably leverage biologically relevant but expensive model systems. Finally, sensitive detection underpins the entire endeavor, ensuring that the data generated is of sufficient quality to drive confident decision-making in reaction discovery and drug development. As HTS continues to evolve with AI integration, complex 3D models, and even more sensitive readouts, these three pillars will remain the foundational supports for its progress.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and its advanced form, Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS), represent a foundational paradigm in modern drug discovery and reaction research. This methodology enables the rapid empirical testing of hundreds of thousands of biological or chemical tests per day through integrated automation, miniaturized assays, and sophisticated data analysis [13] [14]. The evolution from simple 96-well plates to uHTS has fundamentally transformed the operational principles of discovery research, shifting the focus from capacity alone to a balanced emphasis on quality, physiological relevance, and cost efficiency [13]. This whitepaper traces the technical history of this evolution, framing it within the core principles that guide contemporary high-throughput reaction discovery research.

The Historical Trajectory of HTS and Microplate Technology

The Origins: Microplate Invention and Early Adoption

The genesis of HTS is inextricably linked to the invention of the microplate. The first 96-well microplate was created in 1951 by Dr. Gyula Takatsy, a Hungarian microbiologist seeking a cost-efficient method to conduct serial dilutions for blood tests during an influenza outbreak [15]. He used calibrated spiral loops and glass plates with wells to perform multiple simultaneous tests. This concept was commercialized in 1953 by American inventor John Liner, who produced the first disposable 96-well plates, founding the company American Linbro and setting the stage for the standardized consumables essential to modern HTS [15]. A significant milestone was reached in 1974 when the microplate was first used for an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), demonstrating its utility for complex biological assays [15].

The Birth of Modern HTS

The conceptual application of HTS in the pharmaceutical industry began in the mid-1980s. A pivotal development occurred at Pfizer in 1986, where researchers substituted fermentation broths in natural products screening with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solutions of synthetic compounds, utilizing 96-well plates and reduced assay volumes of 50-100μL [16]. This transition from single test tubes to an array format, coupled with automated liquid handling, marked a fundamental shift. As shown in Table 1, this change dramatically increased throughput while reducing material use and labor [16]. Starting at a capacity of 800 compounds per week in 1986, Pfizer's process reached a steady state of 7,200 compounds per week by 1989 [17] [16]. By 1992, HTS was producing starting points for approximately 40% of Pfizer's discovery portfolio, proving its value as a core discovery engine [17] [16].

Table 1: The HTS Paradigm Shift in the Late 1980s

| Parameter | Traditional Screening | Early HTS |

|---|---|---|

| Format | Single tube | 96-well array |

| Assay Volume | ~1 mL | 50–100 µL |

| Compound Used | 5–10 mg | ~1 µg |

| Compound Source | Dry compounds, custom solutions | Compound file in DMSO solution |

| Throughput | 20–50 compounds/week/lab | 1,000–10,000 compounds/week/lab |

The Push for Higher Throughput and the Rise of uHTS

The 1990s witnessed an accelerated drive for higher throughput, fueled by the sequencing of the human genome and the expansion of corporate compound libraries [13]. The term "Ultra-High-Throughput Screening" was first introduced in a 1994 presentation, and by 1996, 384-well plates were being used in proof-of-principle applications, moving HTS from thousands of compounds per week to thousands of compounds per day [17]. The cut-off between HTS and uHTS is somewhat arbitrary, but uHTS is generally defined by the capacity to generate in excess of 100,000 data points per day [13] [17]. This era saw the development of dedicated uHTS systems, such as the EVOscreen system (Evotek, 1996) and the ANALYST (LJL Biosystems, 1997), which could achieve throughputs of ~70,000 assays per day [17]. By 1998, 384-well plates were widely used, and 1536-well plates were being tested [17]. The subsequent launch of fully integrated platforms, like Aurora Biosciences' system for Merck (2000) and the FLIPR Tetra system for ion channel targets (Molecular Devices, 2004), cemented uHTS as a standard industrial practice [17]. This evolution in throughput is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Evolution of Screening Throughput and Miniaturization

| Time Period | Key Development | Typical Throughput | Dominant Microplate Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Manual, tube-based testing | 10-100 compounds/week | Test Tubes |

| Mid-1980s | Birth of HTS with automation | Hundreds-7,000 compounds/week | 96-well |

| Mid-1990s | Adoption of 384-well plates | Tens of thousands of compounds/week | 384-well |

| Late 1990s | Advent of uHTS; 1536-well plates | >100,000 compounds/day | 384-well / 1536-well (emerging) |

| 2000s | Fully integrated robotic uHTS | >1,000,000 compounds/day | 1536-well |

Core Technological Enablers and Methodologies

Assay Formats and Detection Technologies

The success of HTS/uHTS hinges on robust, miniaturizable assay formats. The two primary categories are cell-free (biochemical) and cell-based assays [18].

- Biochemical Assays: These are used to investigate molecular interactions between a target (e.g., an enzyme, receptor) and test compounds. A common format is the competitive displacement fluorescence polarization (FP) assay. For example, in a screen for Bcl-2 family protein inhibitors, a fluorescein-labeled peptide that binds the target protein is used [19]. When bound, the peptide rotates slowly, producing high polarization. If a test compound displaces the peptide, the rotation speed increases, causing a measurable drop in polarization, thus identifying a "hit" [19].

- Cell-Based Assays: These are crucial for understanding cellular processes, transmembrane transport, and cytotoxicity [18] [20]. They allow researchers to investigate whole pathways and phenotypic changes in a more physiologically relevant context. A widely used technology is the FLIPR (Fluorescent Imaging Plate Reader) system, which is particularly adept at measuring fast kinetics in ion channel and GPCR (G-Protein Coupled Receptor) assays by detecting calcium flux or membrane potential changes in real-time [17].

Fluorescence-based techniques remain a primary detection method due to their high sensitivity, diverse range of fluorophores, and compatibility with miniaturization and multiplexing [20]. Luminescence and absorbance are also common readouts.

The Integrated HTS/uHTS Workflow

A modern uHTS campaign is a multi-step, integrated process. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages from library management to hit confirmation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of HTS/uHTS relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components essential for establishing a robust screening platform.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS/uHTS

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in HTS/uHTS |

|---|---|

| Microplates (96, 384, 1536-well) | The foundational labware for parallel sample processing. Higher density plates (e.g., 1536-well) are critical for uHTS miniaturization [13] [15]. |

| Compound Libraries in DMSO | Standardized collections of small molecules or natural product extracts stored in dimethyl sulfoxide, the universal solvent for HTS. These are the "screening deck" [16] [19]. |

| Fluorescent/Luminescent Probes | Essential reagents for detection. Examples include FITC-labeled peptides for FP assays [19] or dyes for cell viability and caspase activation [20] [19]. |

| Cell Lines (Primary, Immortalized, Stem Cells) | Biological systems for cell-based assays. The trend is toward using more physiologically relevant cells, including stem cell-derived neurons and 3D organoids [18] [20]. |

| Liquid Handling Reagents (Buffers, Enzymes, Substrates) | The core biochemical components of the assay, prepared in bulk and dispensed automatically to initiate reactions [19]. |

| Damascenone | β-Damascenone (2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-crotonyl-1,3-cyclohexadiene) |

| Gomisin A | Gomisin A, MF:C23H28O7, MW:416.5 g/mol |

Contemporary Trends and Future Directions

The field of HTS is currently at a crossroads, with a clear shift from a purely quantitative focus to a qualitative increase in screening content [13]. Key contemporary trends include:

- Quality over Throughput: Greater emphasis is placed on rigorous assay characterization, the use of physiologically relevant models, and early hit validation using orthogonal assay technologies to reduce attrition rates [13].

- The Rise of Phenotypic Screening and 3D Models: There is a growing use of target identification strategies following phenotypic screening and the implementation of more complex screening models, such as three-dimensional (3D) organoids [13] [18]. These 3D models, combined with microfluidic devices, aim to better recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment, narrowing the gap between screening results and clinical outcomes [18].

- Next-Generation Screening Paradigms: Techniques like Quantitative HTS (qHTS), which generates full concentration-response curves for all library compounds, are being adopted to provide richer pharmacological data early in the process [13] [14]. Furthermore, fragment-based screening (FBS) and affinity selection methodologies are being merged with HTS strategies to tackle difficult target classes like protein-protein interactions [13].

- Miniaturization Beyond Microplates: While the trend toward further miniaturization is slowing, advanced platforms like drop-based microfluidics are emerging, enabling millions of reactions in hours using picoliter volumes at a fraction of traditional costs [18] [14].

The journey from the 96-well plate to uHTS represents more than just a history of technological advancement; it reflects an evolving philosophy in reaction discovery research. The initial drive for quantitative increases in throughput has matured into a sophisticated discipline that strategically balances speed, cost, and quality. The core principles of HTS—miniaturization, automation, and parallel processing—remain fundamental, but their application is now more nuanced, project-specific, and integrated with other discovery tools like computational design and fragment-based approaches. As the field continues to evolve with 3D organoid models, microfluidics, and advanced data analytics, HTS/uHTS will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone of biomedical research, continually refining its principles to deliver better chemical starting points for drug discovery and beyond.

High-throughput screening (HTS) represents a fundamental paradigm in modern scientific discovery, enabling the rapid experimental conduct of millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [14]. This methodology leverages robotics, sophisticated data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways [14]. Within drug discovery and reaction discovery research, HTS provides the critical starting points for drug design and understanding the interaction roles within biological systems. The efficiency of HTS stems from its highly automated and parallelized approach, with systems capable of testing up to 100,000 compounds per day, and ultra-HTS (uHTS) pushing this capacity beyond 100,000 compounds daily [14]. The core terminology of HTS—encompassing hits, assays, libraries, and hit selection—forms the essential lexicon for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this field. A thorough grasp of these concepts is indispensable for designing effective screening campaigns and interpreting their results within a broader research thesis.

Core Terminology and Definitions

Hits

In HTS, a hit is a compound that exhibits a desired therapeutic or biological activity against a specific target molecule during a screening campaign [21]. Hits are the primary output of the initial screening phase and provide crucial initial information on the relationship between a compound's molecular structure and its biological activity [21]. Following discovery, hits undergo a rigorous confirmation process to verify their activity before advancing to the next stage. It is important to distinguish a "hit" from a "lead" compound. A hit demonstrates confirmed activity in a screening assay, whereas a lead compound is a validated hit that has been further optimized and possesses promising properties for development into a potential drug candidate, including acceptable potency, selectivity, solubility, and metabolic stability [21].

Assays

An assay is the experimental test or method used to measure the effect of compounds on a biological target. In HTS, assays are conducted in microtiter plates featuring grids of small wells, with common formats including 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144 wells [14]. The biological entity under study—such as a protein, cells, or animal embryo—is introduced into the wells, incubated to allow interaction with the test compounds, and then measured for responses using specialized detectors [14]. Assays are designed to be simple, automation-compatible, and suitable for rapid testing. A significant advancement is quantitative HTS (qHTS), which tests compounds at multiple concentrations to generate full concentration-response curves immediately, thereby providing richer data and lower false-positive/negative rates compared to traditional single-concentration HTS [22] [23].

Libraries

A screening library, or compound library, is a curated collection of substances stored in microtiter plates (stock plates) screened against biological targets [14]. These libraries can comprise small molecules of known structure, chemical mixtures, natural product extracts, oligonucleotides, or antibodies [23]. The contents of these libraries are carefully cataloged, and assay plates are created by transferring small liquid volumes from stock plates for experimental use [14]. Libraries serve as the source of chemical diversity for discovering novel active compounds. Beyond chemical libraries, other types include siRNA/shRNA libraries for gene silencing, cDNA libraries for gene overexpression, and protein libraries [24].

Hit Selection

Hit selection is the statistical and analytical process of identifying active compounds (hits) from the vast dataset generated by an HTS campaign [14]. This process involves differentiating true biological signals from background noise and systematic errors. The specific analytical methods depend on whether the screen is conducted with or without replicates. Key metrics used in hit selection include the z-score (for screens without replicates), t-statistic (for screens with replicates), and Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) [14]. SSMD is particularly valuable as it directly assesses the size of compound effects and is comparable across experiments [14]. Robust methods accounting for outliers, such as the z*-score and B-score, are also commonly employed [14].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Primary Screening Protocol

The primary screening protocol forms the foundational stage of HTS, designed to test all compounds in a library against a target to identify initial hits.

- Assay Plate Preparation: An assay plate is created by transferring nanoliter volumes of compounds from a stock library plate to an empty microtiter plate using robotic liquid handlers [14]. The specific plate format (e.g., 384 or 1536-well) is chosen based on the required throughput and reagent availability.

- Biological Reaction Setup: The biological target (e.g., enzymes, cells) is added to each well of the assay plate in a suitable buffer, often using automated dispensers [14]. Controls are included: positive controls (known activators/inhibitors) and negative controls (no compound or solvent only) are essential for quality control.

- Incubation and Reaction: The assay plate is incubated under optimal conditions (e.g., specific temperature, humidity) for a predetermined time to allow interaction between compounds and the biological target [14].

- Signal Detection: Following incubation, a detection method is applied. This varies by assay design and may involve measuring fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, or other physical properties using specialized plate readers [23] [24]. The reader outputs a grid of numerical values mapping to the signal from each well.

- Primary Hit Identification: Raw data is processed using hit selection algorithms. For single-concentration screens, simple methods like percent inhibition or z-score are often used initially to flag compounds exhibiting significant activity beyond a predefined threshold [14].

Hit Confirmation and qHTS Protocol

This protocol validates the initial hits and provides quantitative pharmacological data.

- Cherrypicking: Compounds identified as hits in the primary screen are transferred ("cherrypicked") from the stock library into new assay plates for retesting [14].

- Dose-Response Testing (qHTS): In qHTS, cherrypicked hits are tested across a range of concentrations (typically 8-15 points in a serial dilution) instead of a single concentration [22]. This is often performed directly in the primary screen in modern setups.

- Concentration-Response Curve Fitting: The dose-response data for each compound is fitted to a nonlinear model, most commonly the four-parameter Hill equation (Equation 1) [22]: Ri = E0 + (E∞ - E0) / (1 + exp{-h[log Ci - log AC50]}) where Ri is the response at concentration Ci, E0 is the baseline, E∞ is the maximal response, AC50 is the half-maximal effective concentration, and h is the Hill slope [22].

- Hit Confirmation and Prioritization: Compounds that produce robust concentration-response curves, with acceptable estimates for potency (AC50), efficacy (Emax), and curve quality, are confirmed as hits. They are then prioritized for the next stage based on these parameters and early assessment of selectivity and chemical tractability.

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Quality Control Metrics

Robust quality control (QC) is critical for ensuring HTS data reliability. Effective QC involves good plate design, selection of effective controls, and development of robust QC metrics [14]. Key metrics for assessing data quality and assay performance include:

Table 1: Key Quality Control Metrics for HTS Data Analysis

| Metric | Formula/Description | Application | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor [14] | 1 - (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| | Assay Quality | ≥ 0.5: Excellent assay0.5 > Z' > 0: MarginalZ' ≤ 0: Poor assay |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio [14] | μpositive / μnegative | Assay Robustness | Higher values indicate stronger signal detection |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio [14] | (μpositive - μnegative) / σ_negative | Assay Robustness | Higher values indicate cleaner signal |

| Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) [14] | (μpositive - μnegative) / √(σ²positive + σ²negative) | Data Quality | Assesses effect size and degree of differentiation between controls |

Hit Selection Methodologies

Hit selection methodologies vary based on screening design, particularly the presence or absence of replicates.

Table 2: Statistical Methods for Hit Selection in HTS

| Method | Application Context | Key Characteristics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| z-score [14] | Primary screens (no replicates) | Measures number of standard deviations from the mean; assumes all compounds have same variability as negative reference. | Sensitive to outliers; relies on strong assumptions about data distribution. |

| z*-score [14] | Primary screens (no replicates) | Robust version of z-score; less sensitive to outliers. | More reliable for real-world data with variability. |

| t-statistic [14] | Confirmatory screens (with replicates) | Uses compound-specific variability estimated from replicates. | Suitable with replicates; p-values affected by both sample size and effect size. |

| SSMD [14] | Both with and without replicates (calculations differ) | Directly measures size of compound effect; comparable across experiments. | Preferred for hit selection as it focuses on effect size rather than significance testing. |

| B-score [14] | Primary screens | Robust method that normalizes data for plate-level systematic errors. | Effective for removing spatial artifacts within plates. |

For screens with replicates, SSMD or t-statistics are appropriate as they can leverage compound-specific variability estimates. SSMD is particularly powerful because its population value is comparable across experiments, allowing consistent effect size cutoffs [14]. In qHTS, curve-fitting parameters from the Hill equation (AC50, Emax, Hill coefficient) are used for hit selection and prioritization, though careful attention must be paid to parameter estimate uncertainty, especially when the concentration range does not adequately define asymptotes [22].

Diagram 2: Hit Selection and Prioritization Logic

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful HTS implementation requires specialized materials and reagents designed for automation and miniaturization. The following toolkit details key components essential for establishing a robust HTS platform.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates [14] | The primary labware for conducting assays in a parallel format. | Available in 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144-well formats; made of optical-grade plastic for sensitive detection. |

| Compound Libraries [14] [23] | Collections of small molecules, natural products, or other chemicals screened for biological activity. | Carefully catalogued in stock plates; contents can be commercially sourced or internally synthesized. |

| Liquid Handling Robots [14] [24] | Automated systems for precise transfer of liquid reagents and compounds. | Enable creation of assay plates from stock plates and addition of biological reagents; critical for reproducibility and throughput. |

| Sensitive Detectors / Plate Readers [14] [23] | Instruments for measuring assay signals from each well in the microtiter plate. | Capable of various detection modes (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance); high-speed for processing many plates. |

| Assay Reagents | Biological components and chemicals used to configure the specific test. | Includes purified proteins, enzymes, cell lines, antibodies, fluorescent probes, and substrates specific to the target pathway. |

| qHTS Software [22] | Computational tools for analyzing concentration-response data and curve fitting. | Generate dose-response curves, calculate AC50, Emax, and Hill slope parameters for lead characterization and prioritization. |

The precise understanding of hits, assays, libraries, and hit selection forms the foundation of effective high-throughput screening. These core components create an integrated pipeline that transforms vast compound collections into validated starting points for reaction discovery and drug development. The evolution from traditional HTS to quantitative HTS (qHTS) and the application of robust statistical methods like SSMD have significantly enhanced the reliability and information content of screening data [14] [22]. As HTS technologies continue to advance with ever-greater miniaturization, automation, and computational power, the principles governing these key terminologies remain central to interpreting results and making informed decisions in research. Mastering this vocabulary and the underlying concepts enables scientists to design more effective screens, critically evaluate data quality, and successfully navigate the complex journey from hit identification to lead compound.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated, miniaturized approach that enables the rapid assessment of libraries containing thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds against biological targets [1]. In drug discovery and reaction discovery research, HTS serves as a powerful platform to identify novel lead compounds by rapidly providing valuable cytotoxic, immunological, and phenotypical information [25] [1]. The central workflow encompasses several integrated stages: compound library management, assay development, automated screening execution, and sophisticated data acquisition and analysis. This integrated system allows researchers to quickly identify potential hits (10,000–100,000 compounds per day) and implement "fast to failure" strategies to reject unsuitable candidates as quickly as possible [1]. The following sections provide an in-depth technical examination of each component within this critical pathway, with specific consideration for its application in reaction discovery research.

Compound Management and Library Preparation

Foundation of Screening Operations

An efficient and versatile Compound Management operation is fundamental to the success of all downstream processes in HTS and small molecule lead development [26]. This stage requires reliable yet flexible systems capable of incorporating paradigm changes in screening methodologies. At specialized centers such as the NIH Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), compound management systems have been uniquely tasked with preparing, storing, registering, and tracking vertically developed plate dilution series (inter-plate titrations) in 384-well format, which are subsequently compressed into 1536-well plates for quantitative HTS (qHTS) applications [26]. This qHTS approach involves assaying complete compound libraries at multiple dilutions to construct full concentration-response profiles, necessitating highly precise compound handling and tracking systems.

Practical Implementation Protocols

For practical implementation, compound libraries are typically prepared in 384-well compound plates ("source plates") [27]. When screening plates are prepared in-house, compounds are generally dissolved in HPLC-grade DMSO or similar solvents at a consistent, high concentration (e.g., 2 mM) [27]. The protocol involves:

- Compound Transfer: Using automated systems such as the BioMek FX pintool to transfer 100 nL of compound from source plates to cell culture plates [27].

- Tool Maintenance: Washing the pintool with solvent and blotting on filter paper three times using a sequence of HPLC grade solvents (DMSO, isopropyl alcohol, methanol) [27].

- Quality Control: Including compounds with known function as additional controls to verify compound transfer efficiency and biological system responsiveness [27].

Automated liquid-handling robots capable of low-volume dispensing of nanoliter aliquots have become essential for minimizing assay setup times while providing accurate and reproducible liquid dispensing [1]. This compound management foundation enables the handling of libraries exceeding 200,000 members as demonstrated in successful screening campaigns [26] [27].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Materials and Equipment for Compound Management and Screening

| Item | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precise transfer of nanoliter volumes of compounds and reagents [27] | BioMek FX pintool, Labcyte Echo [27] |

| Microplates | Standardized format for miniaturized assays [1] | 384-well and 1536-well plates [26] [27] |

| Plate Washer | Automated aspiration and dispensing for cell washing steps [27] | BioTek ELx405 Plate Washer [27] |

| Reagent Dispenser | Rapid and precise dispensing of reagents to plates [27] | BioTek MicroFlo, Thermo Fisher Multidrop Combi [27] |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintenance and stimulation of cells during screening [27] | RPMI 1640 with FBS and antibiotic-antimycotic [27] |

Assay Development and Experimental Design

Core Principles for Robust Assays

HTS assays must be robust, reproducible, and sensitive to effectively identify true hits amid thousands of data points [1]. The biological and pharmacological relevance of each assay must be rigorously validated, with methods appropriate for miniaturization to reduce reagent consumption and suitable for automation [1]. Contemporary HTS assays typically run in 96-, 384-, and 1536-well formats, utilizing automated liquid handling and signal detection systems that require full process validation according to pre-defined statistical concepts [1]. When adapting the core protocol for different targets, researchers must consider critical parameters including the timing of compound addition relative to stimulus and optimal incubation duration, which must be determined empirically for each biological system [27].

Classification of Screening Assays

HTS assays can be broadly subdivided into two principal categories:

- Biochemical Assays: These typically utilize enzymatic targets and measure changes in enzymatic activity through various detection methods [1]. For instance, HTS methods for novel histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors employ a peptide substrate coupled to a suitable leaving group that allows quantification of the HTS substrate activated by the HDAC enzyme [1].

- Cell-Based Assays: These utilize whole cells to measure phenotypic changes, protein expression, or secretion of biomarkers [25] [27]. For example, a protocol for screening immunomodulatory compounds uses human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) cultured in autologous plasma to model the human immune response, measuring cytokine secretion via AlphaLISA assays and cell surface activation marker expression via flow cytometry [25].

Experimental Design Considerations

When designing a screening campaign, investigators must strategically determine the number of compounds to screen and the number of replicates to include. For flow cytometry-based screens, the protocol is ideal for testing approximately ten to twelve 384-well plates at a time [27]. If two rows and two columns on each edge of the plate are excluded to accommodate controls and minimize edge effects, this allows for 240 test wells per plate, or about 2400 compounds per screen without replicates [27]. Ideally, assays should be performed with three replicates of each plate; however, when screening large compound libraries, replicates may be omitted at the risk of missing potential hits [27]. In such cases, all identified hits must be reanalyzed with three or more replicates at several concentrations for confirmation [27].

Automation and Screening Execution

Integrated Robotic Systems

The execution phase of HTS relies on integrated automation systems that combine robotic liquid handling, plate manipulation, and detection technologies. This automation enables the rapid processing of thousands of samples with minimal manual intervention, significantly reducing human error and increasing reproducibility. Compound management has evolved into a highly automated procedure involving compound storage on miniaturized microwell plates with integrated systems for compound retrieval, nanoliter liquid dispensing, sample solubilization, transfer, and quality control [1]. The precision of these systems is critical, as exemplified by protocols that utilize pintools to transfer 100 nL of compound from source plates to cell culture plates [27].

Detection Technologies and Measurement Approaches

Multiple detection technologies can be employed to measure biological responses in HTS assays:

- Fluorescence-Based Methods: These are among the most common due to their sensitivity, responsiveness, ease of use, and adaptability to HTS formats [1]. For instance, differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) monitors changes in fluorescence as a function of protein melting temperatures (T

), where ligand binding results in increased T values [1]. - Mass Spectrometry-Based Methods: These approaches for unlabeled biomolecules are becoming more prevalent in HTS, permitting compound screening in both biochemical and cellular settings [1].

- Flow Cytometry: This technology enables quantitative analysis of cell surface protein expression at single-cell resolution in high-throughput formats [27]. The HyperCyt autosampler system, for example, allows rapid sampling from 384-well plates for flow cytometric analysis [27].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from compound library preparation through data acquisition and hit identification:

HTS Central Workflow from Library to Data

Data Acquisition, Management, and Analysis

Addressing False Positives and Quality Control

One of the most significant challenges in HTS is the generation of false positive data, which can arise from multiple sources including assay interference from chemical reactivity, metal impurities, assay technology limitations, measurement uncertainty, autofluorescence, and colloidal aggregation [1]. To address these issues, several in silico approaches for false positive detection have been developed, generally based on expert rule-based approaches such as pan-assay interferent substructure filters or machine learning models trained on historical HTS data [1]. Statistical quality control methods for outlier detection are essential for addressing HTS variability, encompassing both random and systematic errors [1].

HTS Triage and Hit Prioritization

HTS triage involves the strategic ranking of HTS output into categories based on probability of success: compounds with limited, intermediate, or high potential [1]. This process requires integrated analysis of multiple data parameters, including efficacy, specificity, and cellular toxicity. For example, in a flow cytometry-based screen for PD-L1 modulators, data analysis involves processing through software such as FlowJo or HyperView, followed by statistical analysis in GraphPad Prism to identify significant changes in target expression compared to controls [27]. The application of cheminformatics systems such as Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) is often necessary to manage the substantial data volumes generated [1].

Quantitative Data Parameters

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in HTS Data Analysis

| Parameter | Typical Values/Ranges | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 10,000–100,000 compounds/day (HTS); >300,000 compounds/day (uHTS) [1] | Screening capacity measurement |

| Assay Formats | 96-, 384-, 1536-well plates [1] | Miniaturization level |

| Volume Dispensing | Nanoliter aliquots [1]; 100 nL compound transfer [27] | Liquid handling precision |

| Incubation Period | 72 hours for PBMC stimulation [25]; 3 days for THP-1 PD-L1 expression [27] | Cellular assay duration |

| Data Quality Threshold | Z' factor > 0.5 [1] | Assay robustness metric |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Adaptations

Specialized Screening Modalities

The core HTS workflow supports various specialized screening modalities with specific protocol adaptations:

- Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS): This approach achieves throughput of millions of compounds per day through advanced microfluidics and high-density microwell plates with typical volumes of 1–2 µL [1]. The development of miniaturized, multiplexed sensor systems that allow continuous monitoring of parameters like pH and oxygen concentration has addressed previous limitations in monitoring individual microwell environments [1].

- Functional Genomics Screening: HTS is used in functional genomics to identify biological functions of specific genes and metagenes through rapid analysis of large gene sets to identify those affecting specific diseases or biological pathways [1]. This application commonly utilizes RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing with DNA-encoded libraries [1].

- Immunomodulatory Compound Screening: This specialized application involves stimulating human PBMCs for 72 hours and measuring cytokine secretion via AlphaLISA assays alongside cell surface activation marker expression via flow cytometry [25]. This multiplexed readout workflow directly aids in phenotypic identification and discovery of novel immunomodulators and potential vaccine adjuvant candidates [25].

Protocol for Flow Cytometry-Based HTS

The following detailed protocol adapted from Zavareh et al. outlines a specific implementation for high-throughput small molecule screening using flow cytometry analysis of THP-1 cells:

- Plate Preparation: Cell culture microplates (384-well, sterile) are prepared with THP-1 cells suspended in complete media [27].

- Compound Addition: Using a BioMek FX pintool or similar system, transfer 100 nL of compound from source plates to cell culture plates [27].

- Stimulation: Add IFN-γ (or other relevant stimulus) to induce expression of the target protein (e.g., PD-L1) [27].

- Incubation: Incubate plates for three days at 37°C, 5% CO₂ [27].

- Staining: Centrifuge plates, wash cells with FACS buffer, and stain with specific antibodies (e.g., anti-PD-L1-PE) and viability dye [27].

- Fixation: Fix cells with formaldehyde solution [27].

- Data Acquisition: Analyze plates using a flow cytometer with autosampler (e.g., CyAn ADP with HyperCyt) [27].

- Data Analysis: Process data using specialized software (FlowJo, HyperView) and perform statistical analysis in GraphPad Prism [27].

This protocol has been successfully used to screen approximately 200,000 compounds and can be adapted to analyze expression of various cell surface proteins and response to different cytokines or stimuli [27].

The integrated workflow from compound library management to data acquisition represents a sophisticated technological pipeline that enables the rapid assessment of chemical and biological space for reaction discovery research. Each component—from the initial compound handling through the final data analysis—requires specialized equipment, validated protocols, and rigorous quality control measures to ensure reliable results. As HTS technologies continue to evolve toward even higher throughput and more complex multiplexed readouts, the fundamental principles outlined in this technical guide provide a foundation for researchers to implement and adapt these powerful screening methodologies for their specific discovery applications. The continued integration of advanced automation, miniature detection technologies, and sophisticated computational analysis promises to further enhance the efficiency and predictive power of high-throughput screening in both drug discovery and reaction optimization research.

Executing a Screen: Methodologies, Assay Types, and Practical Applications

High-throughput screening (HTS) represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of compounds to identify potential therapeutic candidates [1]. Within this field, two predominant strategies have emerged: target-based screening and phenotypic screening [28]. These approaches define fundamentally different philosophies for initiating the discovery process. Target-based strategies operate on a reductionist principle, focusing on specific molecular targets known or hypothesized to be involved in disease pathology [29]. In contrast, phenotypic strategies employ a more holistic, biology-first approach, searching for compounds that elicit a desired therapeutic effect in a cell, tissue, or whole organism without preconceived notions of the molecular mechanism [30] [31]. The choice between these pathways has profound implications for screening design, resource allocation, lead optimization, and ultimately, the probability of clinical success. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these methodologies, framed within the broader principles of HTS for reaction discovery research.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Target-Based Screening: A Mechanism-Driven Approach

Target-based screening is founded on the principle of designing compounds to interact with a specific, preselected biological target—typically a protein such as an enzyme, receptor, or ion channel—that has been validated to play a critical role in a disease pathway [28] [32]. This approach requires a deep understanding of disease biology to identify a causal molecular target. The screening process involves developing a biochemical assay, often in a cell-free environment, that can measure the compound's interaction with (e.g., inhibition or activation of) this purified target [29] [33].

A significant advantage of this method is its high efficiency and cost-effectiveness for screening vast compound libraries, as the assays are typically robust, easily miniaturized, and amenable to ultra-high-throughput formats [28] [29]. Furthermore, knowing the target from the outset significantly accelerates the lead optimization phase. Medicinal chemists can use structure-activity relationship (SAR) data to systematically refine the hit compound for enhanced potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties [29]. Prominent successes of this approach include imatinib (which inhibits the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia) and HIV antiretroviral therapies (such as reverse transcriptase and integrase inhibitors) that were developed based on precise knowledge of key viral proteins [32] [29].

Phenotypic Screening: A Biology-First Approach

Phenotypic screening empirically tests compounds for their ability to induce a desirable change in a disease-relevant phenotype, using systems such as primary cells, tissues, or whole organisms [30] [31]. The specific molecular target(s) and mechanism of action (MoA) can remain unknown at the outset of the campaign [28]. This approach is particularly powerful when the understanding of the underlying disease pathology is incomplete or when the disease involves complex polygenic interactions that are difficult to recapitulate with a single target [32].

A key strength of phenotypic screening is its ability to identify first-in-class medicines with novel mechanisms of action [30]. Because the assay is conducted in a biologically relevant context, hit compounds are already known to be cell-active and must possess adequate physicochemical properties (e.g., solubility, permeability) to elicit the observed effect [28] [34]. This can lead to the discovery of unexpected targets and MoAs, thereby expanding the "druggable genome" [30]. Notable successes originating from phenotypic screens include the cystic fibrosis correctors tezacaftor and elexacaftor, the spinal muscular atrophy drug risdiplam, and the antimalarial artemisinin [30] [32].

Strategic Comparison at a Glance

The table below provides a systematic, point-by-point comparison of the two screening strategies to inform strategic decision-making.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Target-Based and Phenotypic Screening Approaches

| Feature | Target-Based Screening | Phenotypic Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Reductionist; tests interaction with a known, purified molecular target [29] [33] | Holistic; tests for a desired effect in a biologically complex system (cells, tissues, organisms) [30] [31] |

| Knowledge Prerequisite | Requires a deep understanding of the disease mechanism and a validated molecular target [32] [29] | Does not require prior knowledge of a specific target; useful for probing complex or poorly understood diseases [28] [32] |

| Typical Assay Format | Biochemical assays using purified proteins (e.g., enzymatic activity, binding) [1] [33] | Cell-based or whole-organism assays (e.g., high-content imaging, reporter gene assays, zebrafish models) [31] [33] |

| Throughput & Cost | Generally very high throughput and more cost-effective per compound tested [28] [34] | Often lower throughput and more resource-intensive due to complex assay systems [28] [34] |

| Hit Optimization | Straightforward; guided by structure-activity relationships (SAR) with the known target [29] | Challenging; requires subsequent target deconvolution to enable rational optimization [30] [34] |

| Key Advantage | Precision, efficiency, and a clear path for lead optimization [32] | Identifies novel targets/MoAs and ensures cellular activity from the outset [28] [30] |

| Primary Challenge | Risk of poor clinical translation if the chosen target is not critically pathogenic [32] [29] | Time-consuming and technically challenging target identification (deconvolution) phase [30] [34] |

| Typical Output | Best-in-class drugs that improve upon existing mechanisms [34] | A disproportionate number of first-in-class drugs [30] [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for a Target-Based Biochemical HTS

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for a target-based high-throughput screen using a purified enzyme.

1. Assay Development and Validation:

- Target Preparation: Purify the recombinant protein (e.g., a kinase) to homogeneity. Confirm activity and stability under assay conditions [1].

- Assay Design: Establish a robust biochemical reaction, such as a kinase reaction transferring a phosphate group from ATP to a peptide substrate. To enable HTS, implement a detection method like fluorescence, luminescence, or mass spectrometry [1] [29]. Fluorescence-based methods are common due to their sensitivity and adaptability to HTS formats [1].

- Miniaturization and Validation: Scale down the assay to a 384-well or 1536-well microplate format. Validate the assay by calculating the Z'-factor (>0.5 is excellent) to confirm robustness and reproducibility, ensuring it is suitable for automation [1] [30].

2. Library Preparation and Screening:

- Compound Management: Prepare the compound library in DMSO and store it in microplates. Use automated liquid-handling robots to dispense nanoliter aliquots of each compound into the assay plates [1].

- Robotic Screening: The automated system adds the purified target, substrate, and cofactors (e.g., ATP) to the plates. After incubation, the detection reagent is added, and signals are read by a microplate reader [1].

3. Hit Triage and Confirmation:

- Data Analysis: Normalize data using controls and apply statistical methods (e.g., Z-score) to identify "hits"—compounds that show significant activity above a defined threshold [33]. Use cheminformatic filters to flag and remove pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) and other false positives [1] [28].

- Hit Confirmation: Re-test confirmed hits in dose-response experiments to determine potency (IC50 values). Use counter-screens to assess selectivity against related targets [1].

Figure 1: Workflow for a target-based high-throughput screen.

Protocol for a Phenotypic HTS

This protocol describes a phenotypic screen using a high-content, cell-based assay to identify compounds that reverse a disease-associated phenotype.

1. Development of a Disease-Relevant Model:

- Cell System Selection: Choose a physiologically relevant cell system. This could be a genetically engineered cell line, a patient-derived primary cell, or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cells [31] [34].

- Phenotype and Readout: Define a quantifiable, disease-relevant phenotype. Examples include:

- High-Content Imaging: Measure changes in neurite outgrowth in a neurodegenerative model, organelle morphology, or protein aggregation (e.g., amyloid-β in Alzheimer's models) [31].

- Reporter Gene Assay: Use a luciferase or GFP reporter under the control of a pathway-specific promoter (e.g., an innate immune or fibrotic pathway) [33].

2. Assay Implementation and Screening:

- Assay Optimization: Optimize cell seeding density, compound treatment time, and staining protocols (if applicable) to ensure a robust and reproducible signal-to-background ratio.

- Automated Screening: Seed cells in 384-well plates. Use robotics to transfer compound libraries. For imaging assays, use an automated high-content imager to capture multiple cellular features per well [34] [33].

- Data Acquisition: Extract quantitative data from images (e.g., fluorescence intensity, cell count, morphological parameters).

3. Hit Validation and Target Deconvolution:

- Hit Identification: Apply statistical methods like the B-score to correct for plate positional effects and identify active compounds [33].

- Validation: Confirm hits in secondary assays that model the disease through a different readout.

- Target Deconvolution: This is a critical, post-hoc step. Techniques include:

- Chemical Proteomics: Use immobilized hit compounds as bait to pull down interacting proteins from cell lysates, which are then identified by mass spectrometry [30] [35].

- Functional Genomics: CRISPR or RNAi screens to identify genes whose knockout or knockdown abrogates the compound's phenotypic effect [30] [34].

- Transcriptomics/Profiling: Compare the gene expression signature of the hit compound to signatures of compounds with known MoA [30].

Figure 2: Workflow for a phenotypic high-throughput screen.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing the screening protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS Campaigns

| Reagent / Material | Function and Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Libraries | Diverse collections of small molecules (e.g., 10,000 - 2,000,000+ compounds) used to identify "hits" [35] [1]. | Includes diverse synthetic compounds, natural products, and focused "chemo-genomic" libraries of known bioactives [35]. Drug-like properties are a key selection criterion. |

| Purified Target Proteins | Recombinant, highly purified proteins (enzymes, receptors) used as the core reagent in target-based biochemical assays [1]. | Requires validation of correct folding and activity. Purity is critical to minimize assay interference. |

| Disease-Relevant Cell Lines | Engineered cell lines, patient-derived cells, or iPSC-derived cells used to model disease phenotypes [31] [34]. | The choice of cell model is the most critical factor for phenotypic screening relevance (e.g., 3D cultures, co-cultures) [34]. |

| Detection Reagents | Probes that generate a measurable signal (fluorescence, luminescence) upon a biological event [1] [33]. | Examples: Fluorescent dyes for cell viability, antibody-based detection, luciferase substrates for reporter assays, and FRET probes for enzymatic activity. |

| Microtiter Plates | Standardized plates with 96, 384, or 1536 wells for performing miniaturized assays [1]. | Assay volume and detection method dictate plate selection (e.g., clear bottom for imaging, white for luminescence). |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotic systems that accurately dispense nano- to microliter volumes of compounds and reagents [1]. | Essential for ensuring reproducibility and throughput in both screening strategies. |

| High-Content Imagers | Automated microscopes coupled with image analysis software for extracting quantitative data from cell-based assays [34]. | Core technology for complex phenotypic screening, allowing multiparametric analysis. |

| MK-0608 | MK-0608, CAS:1001913-41-2, MF:C12H16N4O4, MW:280.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AS-252424 | AS-252424, CAS:1138220-19-5, MF:C14H8FNO4S, MW:305.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated and Future Perspectives

The historical dichotomy between target-based and phenotypic screening is increasingly giving way to a more integrated and synergistic paradigm [28] [34]. A powerful strategy involves using phenotypic screening to identify novel, high-quality hit compounds in a disease-relevant context, followed by target deconvolution to reveal the underlying molecular mechanism. This knowledge can then be used to deploy target-based assays for more efficient lead optimization and the development of subsequent best-in-class drugs [30] [34]. This combined approach leverages the strengths of both methods while mitigating their individual weaknesses.

Future directions in the field are being shaped by several technological advances. The use of more physiologically relevant models, such as 3D organoids, organs-on-chips, and coculture systems that incorporate immune components, is making phenotypic assays more predictive of clinical outcomes [34]. Advances in target deconvolution methods, particularly in chemical proteomics and computational analysis of multi-omics data, are reducing the major bottleneck in phenotypic discovery [30] [31]. Furthermore, the application of functional genomics (CRISPR) and machine learning/artificial intelligence is revolutionizing both approaches, enabling better target validation, library design, and data analysis [30] [34] [1]. For the modern drug discovery professional, mastery of both strategic paradigms—and the wisdom to know when and how to integrate them—is key to navigating the complex landscape of reaction discovery research and delivering transformative medicines.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a foundational approach in modern drug discovery and reaction discovery research, enabling the rapid testing of hundreds of thousands of compounds against biological targets [1]. The effectiveness of HTS campaigns depends critically on the selection of appropriate assay readout technologies, which transform biological events into quantifiable signals [36]. These readouts provide the essential data for identifying initial "hit" compounds from vast libraries, forming the basis for subsequent medicinal chemistry optimization and lead development [20]. This technical guide examines the four principal readout technologies—fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, and high-content imaging—within the context of HTS principles, providing researchers with the analytical framework necessary for informed technology selection.

The transition from traditional low-throughput methods to automated, miniaturized HTS has revolutionized early drug discovery [1]. Contemporary HTS implementations typically utilize microplates in 96-, 384-, or 1536-well formats, combined with automated liquid handling systems to maximize throughput while minimizing reagent consumption [36]. The choice of readout technology directly influences key screening parameters including sensitivity, dynamic range, cost, and susceptibility to artifacts [1]. Understanding the fundamental principles, applications, and limitations of each technology platform is therefore essential for designing robust screening campaigns that generate biologically meaningful data with minimal false positives and negatives [1].

Fundamental Principles and Technical Specifications

Fluorescence-Based Detection

Fluorescence detection operates on the principle of molecular fluorescence, where certain compounds (fluorophores) absorb light at specific wavelengths and subsequently emit light at longer wavelengths [20]. The difference between absorption and emission wavelengths is known as the Stokes shift. Fluorescence-based assays offer exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting analytes at concentrations as low as picomolar levels, and are amenable to homogeneous "mix-and-read" formats that minimize handling steps [36].

Several fluorescence detection modalities have been developed for HTS applications. Fluorescence Intensity (FI) measures the overall brightness of a sample and is widely used in enzymatic assays [36]. Fluorescence Polarization (FP) measures the rotation of molecules in solution by detecting the retention of polarization in emitted light; it is particularly valuable for monitoring molecular interactions such as receptor-ligand binding without separation steps [36]. Time-Resolved Fluorescence (TRF) and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) utilize lanthanide chelates with long fluorescence lifetimes to eliminate short-lived background fluorescence, significantly improving signal-to-noise ratios for challenging cellular targets [36]. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) measures non-radiative energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores when in close proximity, making it ideal for studying protein-protein interactions and conformational changes [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Fluorescence Detection Modalities

| Technology | Detection Principle | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Intensity (FI) | Measures total emitted light | Enzyme activity, cell viability | Simple implementation, low cost | Susceptible to compound interference |