The AI Revolution in Synthetic Chemistry: Accelerating Drug Discovery Through Automation and Machine Learning

This article explores the transformative integration of artificial intelligence and robotics into synthetic chemistry, a paradigm shift that is accelerating drug discovery and materials science.

The AI Revolution in Synthetic Chemistry: Accelerating Drug Discovery Through Automation and Machine Learning

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of artificial intelligence and robotics into synthetic chemistry, a paradigm shift that is accelerating drug discovery and materials science. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning from the foundational concepts and historical evolution of AI in chemistry to its cutting-edge methodological applications in molecular design and automated synthesis. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for deploying these technologies effectively, and concludes with a rigorous validation of their impact through comparative case studies and an examination of the evolving regulatory landscape. By synthesizing insights from academia and industry, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging AI-driven automation to navigate the vast chemical space and bring life-saving therapeutics to patients faster.

From Manual Flasks to AI Assistants: The Foundational Shift in Chemical Synthesis

The fundamental challenge confronting traditional chemistry in the 21st century is one of immense scale. The theoretically accessible chemical space containing potential drug-like molecules is estimated to be on the order of 10^60 compounds, a number so vast that it defies comprehensive exploration through conventional experimental means [1]. This astronomical size creates what researchers now term the "data bottleneck" - a critical limitation where the generation of high-quality, experimentally validated chemical data cannot possibly keep pace with the theoretical possibilities. While high-throughput screening (HTS) technologies represented a significant advancement, allowing testing of approximately 2 million compounds, this still only scratches the surface of what's chemically possible [2]. The bottleneck has profound implications for industries reliant on molecular discovery, particularly pharmaceuticals, where the traditional drug discovery process remains prohibitively lengthy and expensive, often requiring 10-12 years and costing $2-3 billion per approved therapy [2].

The emergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning promised to revolutionize this landscape by enabling virtual screening of massive chemical libraries. However, these AI models themselves face a fundamental constraint: they require large, well-curated, experimentally validated datasets for training, which simply do not exist for many emerging chemical domains [2]. This creates a circular dependency - AI needs data to find new chemicals, but generating that data requires knowing which chemicals to test. The situation is particularly acute for iterative design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles in drug discovery, where each cycle involves synthesizing and validating compounds against 15-20 chemical parameters (e.g., potency, selectivity, solubility, permeability, toxicity, pharmacokinetics), a process that typically consumes 3-5 years (approximately 26% of the total drug development timeline) [2]. This iterative optimization process suffers from high failure rates, with approximately 50% of projects failing to identify a viable drug candidate due to insurmountable molecular flaws discovered late in the process [2].

Table: The Scale Challenge in Chemical Exploration

| Methodology | Exploration Capacity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Synthesis | Dozens to hundreds of compounds | Extremely slow, resource-intensive |

| High-Throughput Screening | ~2 million compounds | Still infinitesimal compared to chemical space |

| Theoretical Chemical Space | 10^60 drug-like molecules | Physically impossible to explore exhaustively |

The Experimental Workflow: Traditional vs. AI-Augmented Approaches

The Traditional Chemistry Workflow

Traditional chemical discovery follows a linear, resource-intensive pathway that inherently limits exploration. The process typically begins with target identification and validation, followed by compound screening using methods like high-throughput screening (HTS) of available compound libraries. The initial "hits" identified then enter the iterative optimization phase, where medicinal chemists systematically modify structures to improve multiple parameters simultaneously. This requires manual synthesis of analogues, followed by biological testing across various assays, with each cycle taking weeks to months. The final stages involve lead optimization and preclinical development of candidate molecules. The critical limitation of this approach is its serial nature and heavy resource demands, which naturally restrict exploration to narrow chemical domains adjacent to known starting points, introducing significant human bias toward familiar chemical space [2].

AI-Augmented Discovery Workflows

Modern AI-augmented approaches fundamentally reshape this workflow through parallelization and prediction. A pioneering example comes from battery electrolyte research, where researchers developed an active learning framework that could explore a virtual search space of one million potential electrolytes starting from just 58 initial data points [1]. This methodology represents a paradigm shift from exhaustive exploration to intelligent, guided search. The process begins with a small seed dataset of experimentally validated compounds, which trains an initial predictive model. This model then prioritizes the most promising candidates from the virtual chemical space for experimental testing. Crucially, the results from these experiments are fed back into the model in an iterative loop, continuously refining its predictions and guiding the exploration toward optimal regions of chemical space [1].

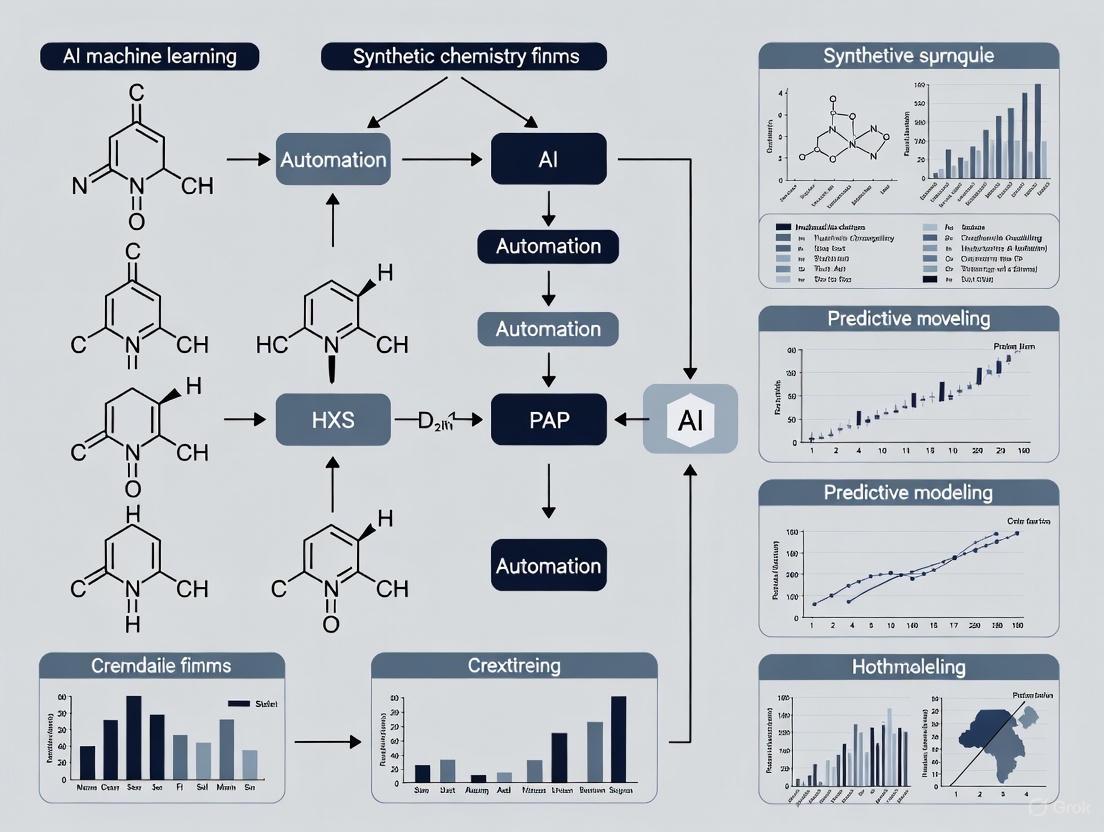

Diagram: AI-Augmented Chemical Discovery Workflow. This active learning cycle enables efficient navigation of vast chemical spaces with minimal experimental overhead.

This active learning methodology directly addresses the data bottleneck by maximizing the informational value of each experiment. Rather than testing compounds randomly or based solely on chemist intuition, the AI model quantifies uncertainty and prediction confidence, allowing researchers to strategically select compounds that will provide the most learning value. In the battery electrolyte study, this approach enabled the identification of four distinct new electrolyte solvents that rivaled state-of-the-art performance after testing only about 10 electrolytes per campaign across seven active learning cycles [1]. The key innovation is the tight integration of computational prediction with experimental validation, creating a virtuous cycle where each data point informs subsequent exploration decisions.

Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental validation of AI-predicted compounds requires sophisticated research reagents and analytical capabilities. The table below details essential components for conducting AI-guided chemical discovery in the context of battery electrolyte development and drug discovery.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for AI-Guided Chemical Discovery

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Anode-Free Lithium Metal Cells | Experimental platform for testing electrolyte performance | Battery electrolyte screening [1] |

| High-Throughput Biology Assays | Multi-parameter optimization of drug candidates | DMTA cycles in drug discovery [2] |

| Automated Synthesis Platforms | Rapid compound synthesis from digital designs | Integration with AI design tools [2] |

| Analytical Standards | Quality control and compound characterization | All synthetic chemistry applications [3] |

| Chemical Building Blocks | Modular components for compound synthesis | Library generation for exploration [3] |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Guided Discovery

Active Learning for Electrolyte Discovery

The protocol that enabled the discovery of novel battery electrolytes from minimal data involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of computational and experimental steps [1]:

Initial Data Curation: Compile a small seed dataset of 58 experimentally validated electrolytes with measured performance characteristics, focusing on cycle life as the primary metric.

Model Initialization: Train an initial machine learning model using the seed dataset, incorporating both predictive performance and uncertainty estimation. The model should be capable of mapping molecular structures to performance metrics.

Virtual Library Construction: Generate a virtual library of one million potential electrolyte candidates using structural variations of known high-performing compounds.

Candidate Prioritization: Use the trained model to screen the virtual library and prioritize 10-15 candidates for experimental testing based on either high predicted performance or high uncertainty (which provides maximal learning value).

Experimental Validation: Synthesize the prioritized candidates and construct actual battery cells for performance testing. Critical measurements include:

- Discharge capacity over multiple cycles

- Cycle life determination

- Stability metrics under operational conditions

Model Refinement: Incorporate the new experimental results into the training dataset and retrain the model. The expanded dataset should now enable more accurate predictions for subsequent cycles.

Iterative Exploration: Repeat steps 4-6 for 7 active learning campaigns, with each campaign testing approximately 10 electrolytes, progressively refining the model's understanding of the chemical space.

This protocol specifically addresses the data bottleneck by ensuring that each experimental data point provides maximum information gain, enabling efficient navigation of the vast chemical space with minimal experimental effort.

AI-Driven Drug Candidate Optimization

For drug discovery applications, the experimental protocol must address the multi-parameter optimization challenge [2]:

Target Identification: Utilize AI analysis of multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to identify promising drug targets, represented as amino acid sequences.

Structure Determination: Employ AI-based structure prediction tools (like AlphaFold) to determine the three-dimensional structure of target proteins, bypassing traditional experimental methods that typically require 6 months and $50,000-$250,000 per structure.

Compound Design: Use generative AI models to design novel compounds that bind to the target, optimizing for multiple parameters simultaneously including:

- Binding affinity (potency)

- Selectivity against related targets

- Solubility and permeability

- Metabolic stability and toxicity profile

Automated Synthesis: Implement automated synthesis platforms to rapidly produce the designed compounds, addressing the traditional bottleneck of manual synthesis.

High-Throughput Testing: Employ automated biological testing systems to evaluate compounds against the multiple optimization parameters in parallel.

Closed-Loop Learning: Feed experimental results back into the AI models to refine subsequent design cycles, creating an integrated design-make-test-analyze system.

The Role of AI in Overcoming Chemical Space Challenges

Active Learning and Minimal Data Approaches

The most significant advancement in overcoming the data bottleneck is the demonstration that AI models can effectively explore massive chemical spaces with minimal starting data. The battery electrolyte study proved that starting with just 58 data points, an active learning model could navigate a search space of one million potential electrolytes and identify four novel high-performing candidates [1]. This approach leverages several key AI strategies:

- Uncertainty Quantification: The model maintains estimates of prediction uncertainty, allowing researchers to strategically select compounds that will provide maximal information gain.

- Experimental Integration: Unlike purely computational approaches that rely on "computational proxies," this method directly incorporates real-world experimental results at each iteration, ensuring that predictions remain grounded in physical reality [1].

- Bias Reduction: AI models can suggest exploration of chemical regions that human researchers might overlook due to cognitive biases toward familiar structural motifs [1].

The critical innovation is the recognition that AI models don't require millions of data points to be useful - they can provide significant value even with minimal data, so long as the experimental design maximizes the information obtained from each data point.

Generative AI for Novel Chemical Exploration

Beyond simply navigating existing chemical spaces, generative AI models offer the potential to create fundamentally novel molecules beyond those documented in existing literature or databases [1]. This represents a shift from predictive to generative models, where AI can propose molecular structures that may never have been conceived by human chemists. The technical approaches enabling this capability include:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): These probabilistic generative models learn the underlying distribution of chemical space and can sample from this distribution to create novel compounds while maintaining desired chemical properties [4].

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Using a competitive framework between generator and discriminator networks, GANs can produce increasingly realistic molecular structures that satisfy multiple property constraints [4].

- Large Language Models (LLMs): Adapted for chemical applications, LLMs can generate novel molecular structures by treating chemical notations as a language, drawing on their training on vast chemical databases [4].

The ultimate promise of these generative approaches is to access regions of chemical space that have never been explored, potentially discovering entirely new classes of functional materials and therapeutic compounds with properties superior to anything currently known.

Quantitative Analysis of Methodologies

The comparative performance of traditional versus AI-augmented approaches reveals dramatic differences in efficiency and exploration capability. The data from multiple studies demonstrates that AI methodologies can achieve orders-of-magnitude improvement in exploration efficiency while requiring significantly fewer experimental resources.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Chemical Exploration Methodologies

| Methodology | Data Requirements | Exploration Efficiency | Experimental Overhead | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional HTS | 2M compound libraries | 0.000000000000001% of chemical space | 100% (full library screening) | ~0.01% hit rate [2] |

| Traditional DMTA | 50-100 compounds/cycle | Limited to local optimization | High (manual synthesis & testing) | ~50% project failure [2] |

| AI-Augmented Active Learning | 58 initial compounds | 4 hits from 1M space with 70 experiments | ~0.007% of virtual space tested [1] | ~5.7% success rate [1] |

The data reveals that the AI-augmented active learning approach achieves a 570-fold higher success rate compared to traditional HTS, while requiring orders of magnitude fewer experimental resources. This dramatic improvement stems from the guided, intelligent exploration strategy that focuses experimental effort on the most promising regions of chemical space, unlike the brute-force approach of traditional HTS.

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Multi-Objective Optimization

Current AI models for chemical discovery typically optimize for a single primary objective, such as battery cycle life or drug binding affinity [1]. However, real-world applications require simultaneous optimization of multiple parameters. Future advancements must address this multi-objective optimization challenge by developing AI systems that can balance competing constraints and identify optimal trade-offs across numerous performance metrics. For battery electrolytes, this means considering not just cycle life but also factors like safety, cost, temperature performance, and environmental impact [1]. Similarly, drug discovery requires balancing potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity within a single molecular entity [2].

Integration and Automation Infrastructure

The full potential of AI-guided chemical discovery can only be realized through tight integration with automated laboratory infrastructure. The future vision involves creating closed-loop discovery systems where AI models directly interface with automated synthesis and testing platforms, enabling rapid iterative design cycles without human intervention [2]. Key technological requirements include:

- Automated Synthesis Platforms: Robust systems capable of handling diverse chemical transformations and physical states (liquids, solids, gases, corrosive reagents) [2].

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Automated biological and physicochemical testing systems that can rapidly evaluate multiple performance parameters in parallel [2].

- Integrated Data Management: Unified platforms that seamlessly connect computational design, experimental execution, and results analysis.

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) specifically trained on chemical knowledge offers the potential for natural language interfaces to these automated systems, allowing scientists to frame discovery challenges in conversational terms and receive recommended experimental approaches [2].

Validation and Trust Frameworks

As AI plays an increasingly central role in chemical discovery, establishing robust validation frameworks becomes critical. Researchers have identified a "crisis of trust" in synthetic research methods, with concerns about data quality, algorithmic bias, and AI "hallucinations" generating unrealistic molecular proposals [5]. Addressing these concerns requires:

- Uncertainty Quantification: AI systems must provide calibrated confidence estimates for their predictions, enabling researchers to assess reliability.

- Experimental Grounding: Maintaining tight coupling between computational predictions and experimental validation, as demonstrated in the battery electrolyte study where every AI suggestion underwent physical testing [1].

- Bias Auditing: Regular assessment of AI systems for biases toward certain chemical classes or structural motifs.

- Hybrid Validation Approaches: Combining AI-generated insights with traditional experimental validation for high-stakes decisions [5].

The companies that ultimately thrive in this new paradigm will be those that embrace AI's potential for speed and scale while implementing the rigorous governance and critical oversight necessary to ensure the integrity and reliability of its outputs [5].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into chemistry represents a paradigm shift from knowledge-driven expert systems to data-intensive machine learning models, fundamentally accelerating research and discovery. This evolution began in the 1960s with DENDRAL, a groundbreaking project that established the core principles of knowledge-based systems for molecular structure elucidation [6]. For decades, the paradigm of encoding human expertise into computable rules guided AI's application in chemistry. The contemporary landscape, however, is dominated by machine learning (ML) and large language models (LLMs) that learn patterns directly from vast datasets, enabling predictive modeling and autonomous discovery at unprecedented scales [7] [8]. This whitepaper traces the technical journey from the heuristic reasoning of early expert systems to the modern machine learning frameworks that now power autonomous laboratories and AI-driven drug discovery, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists engaged in synthetic chemistry automation.

The DENDRAL Era: Pioneering Knowledge-Based Systems

System Architecture and the Plan-Generate-Test Paradigm

Initiated in 1965 at Stanford University, DENDRAL was designed to address a specific scientific problem: identifying unknown organic molecules by analyzing their mass spectra using knowledge of chemistry [6] [9]. Its primary aim was to study hypothesis formation and discovery in science, automating the decision-making process of expert chemists [6]. The system was built on a robust architecture centered on the plan-generate-test paradigm, which became a cornerstone for subsequent expert systems [6].

The CONGEN (CONGENerator) program formed the core of DENDRAL's generate phase, producing all chemically plausible molecular structures consistent with the input data [6]. A key innovation was the development of new graph-theoretic algorithms that could generate all graphs (representing molecular structures) with specified nodes and connection types (atoms and bonds). The team mathematically proved this generator was both complete (producing all possible graphs) and non-redundant (avoiding equivalent outputs like mirror images) [6]. This paradigm allowed DENDRAL to efficiently navigate the vast space of possible chemical structures by systematically constraining the problem space before generation and rigorously evaluating outputs.

Knowledge Engineering and Heuristic Programming

DENDRAL pioneered the concept of knowledge engineering, which involves structuring and encoding human expertise into machines to emulate expert decision-making [10]. The system employed heuristics—rules of thumb that reduce the problem space by discarding unlikely solutions—to replicate how human experts induce solutions to complex problems [6]. This approach represented a significant departure from previous general problem-solvers, instead focusing on domain-specific knowledge [11].

As Edward Feigenbaum, a key developer of DENDRAL, explained, heuristic knowledge constitutes "the rules of expertise, the rules of good practice, the judgmental rules of the field, the rules of plausible reasoning" [11]. By the 1970s, DENDRAL was performing structural interpretation at post-doctoral level, demonstrating that AI could achieve expert-level performance in specialized scientific domains [6]. The success of DENDRAL directly informed the development of other pioneering expert systems, most notably MYCIN for medical diagnosis of bacterial infections [12] [11].

Table 1: Key Components of the DENDRAL Expert System

| Component | Function | Technical Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Heuristic DENDRAL | Used mass spectra & knowledge base to produce possible chemical structures [6] | First system to automate chemical reasoning of organic chemists [6] |

| Meta-Dendral | Machine learning system that proposed rules of mass spectrometry [6] | Learned from structures & spectra to formulate new scientific rules [6] |

| CONGEN | Stood for "CONGENerator"; generated candidate chemical structures [6] | Graph-theoretic algorithms for complete, non-redundant structure generation [6] |

| Plan-Generate-Test | Basic organization of problem-solving method [6] | Used task-specific knowledge to constrain generator; tester discarded failed candidates [6] |

The Transition to Modern Machine Learning

From Rule-Based Systems to Data-Driven Learning

The transition from expert systems to modern machine learning was marked by a fundamental shift from encoding explicit knowledge to learning patterns directly from data. Early expert systems like DENDRAL relied on knowledge engineering, where human experts painstakingly encoded their domain knowledge into rules [10] [11]. While powerful for well-defined domains, this approach faced significant scalability limitations, as Feigenbaum identified knowledge acquisition as the "key bottleneck problem in artificial intelligence" [11].

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the emergence of statistical approaches and early machine learning techniques that gradually supplanted purely rule-based systems [11]. This shift was particularly evident in drug discovery, where Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models in the 1960s evolved into physics-based Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) platforms in the 1980s-90s, eventually culminating in today's deep learning applications [13]. The critical advancement was the recognition that machines could learn directly from data rather than relying solely on human-curated knowledge, enabling systems to discover patterns beyond human perception.

Key Technological Enablers

Several technological breakthroughs catalyzed the transition to modern machine learning approaches in chemistry. The exponential growth in computational power following Moore's Law enabled the processing of large chemical datasets that were previously intractable [10]. Concurrently, the development of sophisticated algorithms—particularly deep learning architectures like transformer neural networks and graph neural networks—revolutionized molecular property prediction and reaction outcome forecasting [8].

The semantic web and knowledge graph technologies provided a framework for representing complex chemical knowledge in machine-readable formats, facilitating data integration and interoperability across domains [10]. Projects like The World Avatar (TWA) demonstrate how modern knowledge systems can represent complex chemical concepts and enable reasoning across multiple scales and domains [10]. These technological advances collectively addressed the fundamental limitation of early expert systems—the knowledge acquisition bottleneck—by creating infrastructures where machines could learn directly from ever-expanding corpor of chemical data.

Table 2: Evolution of AI Approaches in Chemistry

| Era | Primary Approach | Key Technologies | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1980s | Knowledge-Based Systems [10] | Heuristic programming, Rule-based reasoning [6] | DENDRAL, MYCIN [6] [12] |

| 1980s-2000s | Statistical Learning [11] | QSAR, CADD platforms [13] | Schrödinger [13] |

| 2010s-Present | Deep Learning & AI Agents [8] | Graph neural networks, Transformers, Automated labs [7] [8] | AlphaFold, Synthia, IBM RXN [13] [8] |

Modern Machine Learning in Chemical Research

AI-Driven Synthesis and Reaction Planning

Contemporary AI systems have dramatically transformed synthetic chemistry through retrosynthesis tools that can propose viable synthetic pathways in minutes rather than the weeks traditionally required [8]. Platforms like Synthia (formerly Chematica) combine machine learning with expert-encoded reaction rules to design lab-ready synthetic routes, in one instance reducing a complex drug synthesis from 12 steps to just 3 [8]. Similarly, IBM's RXN for Chemistry uses transformer neural networks trained on millions of reactions to predict reaction outcomes with over 90% accuracy, accessible to chemists worldwide via cloud interfaces [8].

Beyond planning synthetic routes, AI systems now provide mechanistic insights through deep neural networks that analyze kinetic data to automatically identify likely reaction mechanisms [8]. These models have demonstrated robustness in classifying diverse catalytic mechanisms even with sparse or noisy data, streamlining and automating mechanistic elucidation that previously relied on tedious manual derivations [8]. The integration of active machine learning with experimental design represents a particularly promising approach, where algorithms selectively choose the most informative experiments to perform, dramatically accelerating research while reducing costs [14].

Accelerated Drug Discovery and Development

AI has fundamentally reshaped drug discovery by enabling predictive modeling of molecular properties and generative design of novel drug candidates. Modern machine learning models can accurately predict crucial molecular properties including biological activity, toxicity, and solubility, allowing researchers to triage huge compound libraries in silico before physical testing [8]. Open-source tools like Chemprop (using graph neural networks) and DeepChem have democratized access to these capabilities, enabling academic researchers to build QSAR models without extensive computer science backgrounds [8].

The emergence of generative models—including variational autoencoders and generative adversarial networks—has enabled the de novo design of molecular structures with desired properties, potentially uncovering candidate molecules unlike any existing compounds [8]. This approach has yielded tangible breakthroughs, with the first AI-designed drug candidates entering human clinical trials around 2020 [13] [8]. Companies like Insilico Medicine have demonstrated the accelerated potential of these approaches, advancing an AI-designed treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis into Phase 2 clinical trials in approximately half the typical timeline [13]. Frameworks such as SPARROW further enhance efficiency by automatically selecting molecule sets that maximize desired properties while minimizing synthetic complexity and cost [8].

Diagram 1: AI vs Traditional Drug Discovery Workflow: This diagram contrasts the iterative, human-driven traditional drug discovery process with the accelerated, data-driven AI approach, highlighting feedback loops and significantly reduced timelines.

Autonomous Laboratories and Large-Scale Collaboration

The integration of AI prediction with robotic laboratory automation represents the cutting edge of chemical research, creating self-driving labs that can design, execute, and analyze experiments with minimal human intervention [7] [13]. Researchers have demonstrated systems capable of running over 16,000 reactions and generating over one million compounds in massively parallel campaigns, a scale unimaginable through traditional methods [7]. This physical implementation of AI, sometimes termed "Physical AI," enables real-time experimental feedback and continuous model improvement [13].

Large-scale collaborative initiatives exemplify the modern approach to AI-driven chemistry. The NSF Center for Computer Assisted Synthesis (C-CAS), spanning 17 institutions, brings together experts in synthetic chemistry, computational chemistry, and computer science to accelerate reaction discovery and drug development [7]. Such collaborations develop and share computational tools that can be leveraged across the research community, creating a multiplicative effect on output [7]. Industrial partnerships, such as Google DeepMind's Isomorphic Labs collaborating with Novartis and Eli Lilly on joint research worth $3 billion, further demonstrate the substantial resources being deployed at the intersection of AI and chemistry [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Knowledge Engineering and System Implementation

The development of expert systems like DENDRAL followed a meticulous methodology for capturing and implementing chemical knowledge. The process began with knowledge acquisition, where domain experts (such as Carl Djerassi for mass spectrometry) worked closely with computer scientists to explicate their heuristic reasoning processes [6] [11]. This knowledge was then formalized through rule-based systems encoded in programming languages like Lisp, which offered the flexibility needed for symbolic AI processing [6].

The core technical methodology centered on the plan-generate-test paradigm [6]. In the planning phase, the system used mass spectrometry knowledge to derive constraints on possible molecular structures. The generation phase employed the CONGEN program with its graph-theoretic algorithms to produce all chemically plausible structures consistent with these constraints. Finally, the testing phase evaluated candidate structures against spectral data and chemical feasibility criteria, eliminating implausible solutions. This methodology ensured mathematical completeness while maintaining computational feasibility for complex molecular identification tasks.

Modern Machine Learning Implementation

Contemporary AI systems in chemistry typically follow a standardized protocol for model development and deployment. The process begins with data curation and preprocessing, assembling large datasets of chemical structures, reactions, and properties from sources like the USPTO patent database, ChEMBL, and PubChem [8]. These structures are converted into machine-readable representations, most commonly SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) strings or molecular graphs, with appropriate featurization capturing atomic and bond properties [8].

Model architecture selection depends on the specific task: transformer networks for reaction prediction, graph neural networks for molecular property prediction, and generative models (VAEs, GANs, or diffusion models) for de novo molecular design [8]. Training typically employs transfer learning where possible, fine-tuning models pretrained on large chemical databases for specific tasks [13]. The trained models are then integrated into automated workflows, often through cloud-based APIs (like IBM RXN) or embedded within robotic laboratory systems [7] [8]. Continuous learning is achieved through active learning loops where model predictions inform subsequent experiments, whose results then refine the model [14].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DENDRAL | Expert System [6] | First knowledge-based system for molecular structure identification [6] | Analyzing mass spectra to determine unknown organic structures [6] |

| Synthia (Chematica) | AI Retrosynthesis Tool [8] | ML-powered synthesis planning using expert-encoded rules [8] | Reducing synthetic steps for complex targets; route planning [8] |

| IBM RXN | Transformer Model [8] | Predicts reaction outcomes & suggests synthetic routes [8] | Cloud-based reaction prediction >90% accuracy [8] |

| AlphaFold | Deep Learning System [13] | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences [13] | Determining protein structures for drug target analysis [13] |

| Automated Reactors | Physical Hardware [7] | Robotic systems for high-throughput experimentation [7] | Running 16,000+ reactions in parallel for rapid data generation [7] |

| Knowledge Graphs | Data Structure [10] | Semantic representation of chemical knowledge & relationships [10] | Enabling interoperability and inference across chemical data [10] |

Visualization of System Architectures

DENDRAL Plan-Generate-Test Workflow

Diagram 2: DENDRAL Plan-Generate-Test Architecture: This workflow illustrates the core reasoning paradigm of early expert systems, showing how spectral data was processed through constrained generation and testing against a chemical knowledge base.

Modern AI-Driven Chemistry Workflow

Diagram 3: Modern AI-Driven Chemistry Pipeline: This architecture shows the integrated computational and experimental workflow of contemporary AI systems, highlighting the continuous learning cycle between digital design and physical automation.

The journey from DENDRAL's heuristic reasoning to today's deep learning systems represents a fundamental transformation in how artificial intelligence is applied to chemical research. The initial insight that "Knowledge IS Power" [11] established the foundation, while subsequent developments addressed the critical bottleneck of knowledge acquisition through data-driven learning [11]. Contemporary AI systems now function as collaborative partners to chemists, capable of designing novel molecules, predicting complex reaction outcomes, and autonomously executing experimental workflows [7] [8].

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: the expansion of multimodal AI that integrates diverse data types (protein structures, multi-omics, imaging) [13], the creation of virtual cell models and digital twins for personalized drug development [13], and increasingly sophisticated AI agents that provide real-time feedback and experimental guidance [13]. As these technologies mature, they promise to further compress development timelines and costs—potentially reducing the traditional 10-year, $10 million drug discovery cycle to one year at under $100,000 [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these AI tools and methodologies is no longer optional but essential for remaining at the forefront of chemical innovation and therapeutic advancement.

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), deep learning, and robotics is fundamentally transforming synthetic chemistry and drug development research. This integration moves beyond simple automation, creating intelligent systems capable of planning experiments, predicting outcomes, and executing complex laboratory tasks with superhuman precision and speed. In the context of synthetic chemistry automation, these technologies are enabling a shift from traditional, often empirical, methods to a data-driven paradigm where in-silico prediction and autonomous discovery are becoming standard practice. This technical guide examines the core AI technologies powering this revolution, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed understanding of the tools, methodologies, and experimental protocols that are redefining the modern laboratory.

Core AI and Machine Learning Technologies

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Architectures

At the heart of the modern AI-driven lab are specific ML and deep learning architectures, each tailored to address distinct challenges in chemical research.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These are particularly suited to chemical applications because they operate directly on molecular graphs, where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges. GNNs can learn from the structural information of molecules to predict properties such as biological activity, solubility, or toxicity, forming the backbone of modern Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models [8]. Tools like Chemprop implement these networks and have become a popular choice in academic settings for building predictive models [8].

Transformer Neural Networks: Originally developed for natural language processing, transformers have been successfully applied to chemical "languages," such as Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings. Trained on millions of reaction examples, models like those in IBM's RXN for Chemistry can predict reaction outcomes and suggest synthetic routes with reported accuracy exceeding 90% [8]. They learn the statistical likelihood of specific chemical transformations.

Generative Models: This class of models, including Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), is used for de novo molecular design. Instead of merely predicting properties, they generate novel molecular structures that optimize for desired characteristics, such as high binding affinity and low toxicity, exploring chemical space beyond human intuition [8].

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): A key challenge with many deep learning models is their lack of grounding in physical laws. Recent advancements focus on incorporating physical constraints. For instance, MIT's FlowER (Flow matching for Electron Redistribution) model uses a bond-electron matrix to explicitly conserve mass and electrons during reaction prediction, moving from "alchemy" to physically realistic outputs [15]. This approach ensures that predictions adhere to fundamental principles like the conservation of mass.

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The adoption of these technologies is driven by compelling quantitative data on their performance and impact on research efficiency. The following table summarizes key metrics.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Technologies in Chemistry and Drug Discovery

| Technology / Application | Reported Performance / Impact | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Retrosynthesis Planning | Route planning reduced from weeks to minutes [8]. | Synthia (formerly Chematica) platform |

| Reaction Outcome Prediction | >90% accuracy in predicting reaction products [8]. | IBM RXN for Chemistry (Transformer NN) |

| Drug Discovery Timeline | AI-designed drug candidate reached Phase I trials in ~2 years (approx. half the typical timeline) [8]. | Insilico Medicine (Generative AI) |

| Drug Discovery Cost & Time | Up to 40% time and 30% cost reduction to reach preclinical candidate stage [16]. | AI-enabled workflows for complex targets |

| Clinical Trial Success | Potential to increase probability of clinical success above traditional 10% rate [16]. | AI-driven candidate identification |

| Pharmaceutical Manufacturing | 1.5% yield increase and 2% reduction in Cost of Goods (COGS) within 3 months [17]. | Recordati case study (AI-powered analytics) |

| Market Adoption | 30% of new drugs projected to be discovered using AI by 2025 [16]. | Industry forecast |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing AI in the laboratory involves well-defined experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key applications.

Protocol: AI-Guided Retrosynthetic Planning

This protocol outlines the use of AI for planning the synthesis of a target molecule.

- Input Target Molecule: The process begins with a representation of the target molecule, typically as a SMILES string or a molecular structure file.

- Execute Retrosynthetic Analysis: The structure is input into a retrosynthesis planning tool (e.g., Synthia, IBM RXN). The AI, often using a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm integrated with a deep neural network, recursively proposes disconnections to generate a tree of possible synthetic routes [18].

- Route Scoring and Ranking: The proposed routes are scored based on learned criteria, which may include predicted yield, step count, cost of starting materials, safety, and historical precedent [8].

- Route Validation and Selection: The top-ranked routes are presented to the chemist for expert evaluation. The selected route may be further validated through quantum mechanical/machine learning (QM/ML) calculations to assess reaction feasibility [18].

- Execution in Automated Platform: The final synthetic route is translated into a machine-readable code (e.g., a JSON or Python script) that can be executed by a robotic synthesis platform, which controls liquid handlers, reactors, and purification systems.

Protocol: Predictive Model for Reaction Outcome

This protocol describes the creation of a model to predict the major product of a chemical reaction, based on approaches like the MIT FlowER model [15].

- Data Curation and Representation:

- Data Source: Gather a large dataset of known chemical reactions (e.g., from the U.S. Patent Office database) [15].

- Representation: Convert reactants and reagents into a bond-electron matrix, a method inspired by Ivar Ugi's work from the 1970s. This matrix explicitly represents atoms, bonds, and lone electron pairs, providing a foundation for conserving mass and electrons [15].

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Employ a flow matching model (a type of generative AI) that learns to transform the reactant matrix into the product matrix.

- Training Loop: The model is trained to predict the electron redistribution that occurs during the reaction, ensuring the conservation of atoms and electrons is hard-coded into the process, which massively increases prediction validity [15].

- Prediction and Validation:

- Input: A set of reactants and conditions are encoded into the bond-electron matrix representation.

- Output: The trained FlowER model generates the output matrix, which is decoded into the predicted product molecule(s).

- Validation: The prediction is compared against experimental data from the literature or validated through parallel laboratory experiments.

Protocol: AI-Optimized Clinical Trial Patient Recruitment

This protocol leverages AI to enhance the efficiency of patient recruitment in clinical trials.

- Data Aggregation: Aggregate and harmonize real-world data (RWD) from multiple sources, including Electronic Health Records (EHRs), genetic databases, and previous trial data.

- Criteria Modeling with NLP: Use Natural Language Processing (NLP) to parse complex clinical trial eligibility criteria from protocol documents and convert them into a structured, computable format [16].

- Patient Matching: Apply machine learning models (e.g., TrialGPT) to screen the aggregated patient data against the computable criteria. The models can identify eligible patients with high accuracy and also predict the likelihood of patient dropouts [16].

- Cohort Optimization and Reporting: The system generates a list of pre-qualified candidates and can provide analytics on cohort diversity and size. This allows trial designers to refine inclusion/exclusion criteria in near real-time to accelerate enrollment [16].

Visualization of AI-Lab Workflows

The integration of core AI technologies creates a cohesive and autonomous workflow for chemical discovery. The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships and data flow between these components.

Diagram 1: AI-Lab Integration Architecture. This diagram illustrates the flow from data and AI models to decision-making and physical execution in an automated lab, highlighting the continuous feedback loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

In the context of AI-driven synthetic chemistry, the "reagents" are often a combination of software tools, datasets, and robotic hardware. The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Essential "Reagent Solutions" for AI-Driven Laboratory Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Chemprop | Software Library | An open-source tool for training GNNs to predict molecular properties, enabling rapid in-silico screening of compound libraries [8]. |

| DeepChem | Software Library | A Python-based toolkit that democratizes deep learning for drug discovery, materials science, and biology, providing standardized models and datasets [8]. |

| Synthia | Software Platform | An AI-driven retrosynthesis tool that uses a combination of expert-encoded rules and ML to plan complex synthetic routes in minutes [8]. |

| IBM RXN for Chemistry | Cloud Service | Uses transformer networks trained on millions of reactions to predict reaction outcomes and propose synthetic pathways via a web interface [8]. |

| Digital Twin | Simulation Software | A virtual model of the physical lab that simulates workflows and equipment to identify inefficiencies and predict failures before real-world execution [19]. |

| Robotic Liquid Handlers | Laboratory Hardware | Automates precise liquid dispensing for high-throughput screening and sample preparation, integrating with LIMS for end-to-end traceability [19]. |

| Collaborative Robots (Cobots) | Laboratory Hardware | Works alongside technicians to handle hazardous materials or automate tedious tasks like ELISA assays and PCR setups, enhancing safety and throughput [19]. |

| Cloud-Based LIMS | Data Management Platform | The central digital hub for lab operations, enabling real-time data access, collaborative research, and integration with AI and IoT sensors [19]. |

| (+)-Alantolactone | (+)-Alantolactone, CAS:1407-14-3, MF:C15H20O2, MW:232.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Troxerutin | Troxerutin | Troxerutin, a semi-synthetic bioflavonoid. Explore its research applications in vascular health. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The integration of core AI technologies—spanning specialized machine learning architectures, robotics, and data management systems—is creating a new foundation for research in synthetic chemistry and drug development. These are not standalone tools but interconnected components of an emerging "self-driving lab." The quantitative improvements in speed, cost, and success rates are already demonstrating significant value. As these technologies continue to mature, particularly with advances in physical grounding and generalizability, their role will shift from being supportive tools to becoming central, collaborative partners in the scientific discovery process. For researchers, engaging with these technologies is no longer a speculative endeavor but a critical step toward leading the future of accelerated and intelligent discovery.

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with synthetic chemistry is heralding a new era of automation and accelerated discovery. This transformation is underpinned by several foundational computational concepts that are critical for researchers and drug development professionals to master. Chemical space represents the universe of all possible compounds, a domain so vast that its systematic exploration is impossible through traditional means alone. Retrosynthesis provides the logical framework for deconstructing complex target molecules into viable synthetic pathways. In-silico prediction encompasses the suite of computational tools that simulate molecular behavior and properties, acting as a high-throughput digital laboratory. Framed within the context of AI and ML research, these concepts are not merely supportive tools but are becoming core drivers of synthetic chemistry automation, enabling the transition from human-led, iterative experimentation to AI-guided, predictive design. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these pillars, detailing their definitions, methodologies, and their integrated application in modern, data-driven chemical research.

Defining Chemical Space

Chemical space is a cornerstone concept in cheminformatics, defined as the multi-dimensional property space spanned by all possible molecules and chemical compounds that adhere to a given set of construction principles and boundary conditions [20]. It is a conceptual library of conceivable molecules, most of which have never been synthesized or characterized.

Theoretical and Empirical Dimensions

The theoretical chemical space, particularly for pharmacologically active molecules, is astronomically large. Estimations place its size at approximately 10^60 potential molecules, a number derived from applying constraints such as the Lipinski rule of five (e.g., molecular weight <500 Da) and limiting constituent atoms to Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur (CHONS) [20] [21]. This number dwarfs the count of known compounds, highlighting the immense potential for discovery.

In contrast, the empirical chemical space consists of molecules that have been synthesized and cataloged. As of October 2024, over 219 million unique molecules had been assigned a Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) Registry Number, while databases like ChEMBL contain biological activity data for about 2.4 million distinct compounds [20]. This stark disparity between the theoretical and known chemical spaces, often visualized as a near-infinite ocean with only a drop of water explored, is the primary motivation for developing computational methods to navigate it efficiently [21].

Table 1: Scale of Chemical Space

| Type of Chemical Space | Estimated Size | Key Characteristics & Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Drug-Like Space | ~10^60 molecules [20] | Based on Lipinski's rules; typically limited to CHONS elements; max ~30 atoms [20]. |

| Known Drug Space (KDS) | Defined by marketed drugs [20] | A subspace defined by the molecular descriptors of successfully marketed drugs [20]. |

| Empirical Space (Cataloged) | 219 million molecules (CAS) [20] | Real, synthesized compounds that have been registered and characterized. |

| Empirical Space (Bioactive) | 2.4 million molecules (ChEMBL) [20] | Compounds with associated experimentally determined biological activity data. |

Navigation and Exploration with AI

Systematic exploration of chemical space is performed using in-silico databases of virtual molecules and structure generators that create all possible isomers for a given molecular formula [20]. The core challenge is the non-unique mapping between chemical structures and molecular properties, meaning structurally different molecules can exhibit similar properties. AI and ML transform this exploration by enabling rapid virtual screening of billions of molecules. For instance, physics-based platforms coupled with ML can evaluate billions of molecules per week in silico, drastically outperforming traditional lab-based methods that might synthesize only 1,000 compounds per year [21]. This allows researchers to triage vast regions of chemical space and focus laboratory efforts on the most promising candidates.

Retrosynthesis: The Strategic Planning of Syntheses

Retrosynthetic analysis is a problem-solving technique for planning organic syntheses by working backward from a target molecule to progressively simpler, commercially available starting materials [22] [23]. Formalized and popularized by E.J. Corey, it is a cornerstone of synthetic organic chemistry.

Core Principles and Key Terminology

The process involves mentally deconstructing the target molecule through a series of disconnections—the conceptual breaking of bonds. The idealized molecular fragments resulting from a disconnection are called synthons, which correspond to real, purchasable reagents or synthetic equivalents [23]. The objective is to simplify the target structurally until readily available compounds are identified, thereby defining a practical synthetic pathway [22].

Table 2: Key Terminology in Retrosynthetic Analysis

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Target Molecule | The desired final compound whose synthesis is being planned [23]. |

| Disconnection | A retrosynthetic step involving the breaking of a bond to form simpler precursors [23]. |

| Synthon | An idealized fragment resulting from a disconnection [22] [23]. |

| Synthetic Equivalent | The actual, commercially available reagent that performs the function of the idealized synthon in the forward reaction [23]. |

| Transform | The reverse of a synthetic reaction; the formalized process of converting a product back into its starting materials [23]. |

| Retron | A minimal molecular substructure that enables the application of a specific transform [23]. |

The AI Revolution in Retrosynthetic Planning

Traditional retrosynthetic analysis is a demanding intellectual exercise that relies heavily on a chemist's deep knowledge and intuition. However, the problem suffers from a combinatorial explosion of possible routes; a three-step synthesis with 100 options per step yields a million possibilities, making manual navigation daunting [22].

AI has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge. Two primary computational approaches are now prevalent:

- Expert Rule-Based Systems: These systems, such as Synthia, use human-encoded chemical reaction rules and heuristics to propose disconnections. They are highly reliable and grounded in established chemical knowledge [22].

- Data-Driven/Machine Learning Systems: Tools like IBM RXN for Chemistry use transformer neural networks trained on massive reaction datasets (e.g., the USPTO database containing over 1.9 million reactions) to predict reaction outcomes and propose synthetic routes [8] [24]. These models can achieve over 90% accuracy and often suggest novel strategies [8].

The impact is profound, reducing route planning time from "weeks to minutes" and in some cases streamlining complex drug syntheses from 12 steps down to 3, dramatically cutting cost and development time [22] [8]. These AI tools are increasingly integrated with robotic synthesis systems, paving the way for fully autonomous, "self-driving" laboratories [22] [7].

In-Silico Prediction: The Digital Laboratory

In-silico prediction refers to the use of computer simulations to model chemical structures, predict molecular properties, and forecast biological activity. This digital toolkit is essential for prioritizing which molecules to synthesize and test physically, thereby streamlining the research and development pipeline.

Key Methodologies and Applications

The core methodologies of in-silico prediction include:

- Molecular Docking: A structure-based drug design technique that predicts the preferred orientation (binding pose) of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to its target protein (receptor). It is used for virtual screening to estimate binding affinity and identify potential lead compounds [25] [26]. Software platforms like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) are commonly used for this purpose [26].

- ADMET Prediction: Tools like SwissADME predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profiles of molecules. Key parameters include gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, blood-brain barrier penetration, and inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, which are critical for determining a compound's drug-likeness and potential for success [26] [27].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: A computational quantum mechanical method used to investigate the electronic structure of molecules. DFT is employed to optimize molecular geometries, calculate electronic properties, and analyze stability, providing deep insights into structure-activity relationships [25] [27].

Integrated Workflow in Modern Drug Discovery

These in-silico methods are rarely used in isolation. A typical integrated workflow for a novel compound begins with synthesis and structural characterization (e.g., via NMR, MS). This is followed by in-vitro biological assays to determine initial efficacy. Then, in-silico studies are conducted in parallel to rationalize the findings and predict broader applicability: docking simulations explain the mechanism of action at the atomic level, ADMET predictions assess pharmacokinetic suitability, and DFT calculations provide electronic-level insights [25] [26] [27]. This cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation dramatically accelerates the optimization of lead compounds.

Table 3: Core In-Silico Prediction Methods and Their Functions

| Method | Primary Function | Common Tools / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Predicts binding orientation and affinity of a ligand to a protein target. | MOE, AutoDock Vina [26]. |

| ADMET Prediction | Forecasts pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of a molecule. | SwissADME [26]. |

| DFT Calculations | Models electronic structure, optimizes geometry, and analyzes molecular properties. | Software packages using B3LYP/6-31+G level of theory [27]. |

| Virtual Screening | Rapidly computationally tests large libraries of compounds against a biological target. | Chemprop, DeepChem [8]. |

Case Study: Integrated Application in Hybrid Molecule Development

The development of novel chromone-isoxazoline conjugates as antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agents provides a robust, real-world example of these concepts in action [25].

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis and Characterization

Objective: To synthesize and evaluate the bioactivity of novel chromone-isoxazoline hybrid molecules.

Synthesis Methodology:

- Preparation of Dipolarophile: Allylchromone 3 is synthesized from chromone aldehyde and aminoaldehyde precursors as a key intermediate [25].

- Generation of 1,3-Dipole: Arylnitrile oxides are generated in situ through the dehalogenation of the corresponding aldoximes using triethylamine as a base [25].

- 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition: The key reaction involves combining the allylchromone 3 with the arylnitrile oxide in dichloromethane at ambient temperature. This reaction proceeds smoothly to yield the target chromone-isoxazoline hybrids (5a-e) as 3,5-disubstituted regioisomers [25].

Structural Characterization:

- Spectroscopy: Structures are confirmed using ¹H-NMR and ¹³C-NMR spectroscopy. Key diagnostic signals include an AB system for the diastereotopic protons of the isoxazoline's C4' (δ ~3.21 & 3.58 ppm) and a methine proton (CH5') around δ ~5.08 ppm, confirming the isoxazoline ring formation [25].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Used to confirm molecular mass.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Unambiguously determines the solid-state structure, confirming the compound crystallizes in the monoclinic system (Space Group: P2â‚/c) [25].

Biological Evaluation and In-Silico Analysis

In-Vitro Assays:

- Antibacterial Activity: Evaluated against Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella aerogenes, E. coli, Salmonella Typhi) using disk diffusion, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) assays. Results showed promising efficacy compared to the standard antibiotic chloramphenicol [25].

- Anti-inflammatory Activity: Assessed via the inhibition of the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) enzyme. Compound 5e was the most active, with an IC₅₀ value of 0.951 ± 0.02 mg/mL [25].

In-Silico Studies:

- Molecular Docking: Simulations revealed the specific interactions between the synthesized molecules and target proteins (e.g., 5-LOX), providing a mechanistic rationale for the observed anti-inflammatory activity [25].

- ADMET Predictions: These studies forecasted favorable drug-likeness, including high GI absorption and minimal CYP enzyme inhibition, supporting the compounds' potential as drug candidates [25].

- DFT Calculations: Geometry optimization and analysis of electronic properties were performed to understand the structural and electronic basis of the compounds' activity and stability [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Synthesis and Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| 5-Methylisoxazole-4-carboxylic Acid | A core heterocyclic building block for derivatization via amide bond formation [26]. | Serves as a parent molecule for creating a library of 12 derivatives with antimicrobial and anticancer properties [26]. |

| Chromone Aldehyde | A key precursor for constructing the chromone pharmacophore in molecular hybridization [25]. | Used in the synthesis of the allylchromone dipolarophile for 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition [25]. |

| Benzyl Bromides | Alkylating agents used to introduce benzyl groups onto heterocyclic scaffolds [27]. | Various substituted benzyl bromides were conjugated to a pyrimidine intermediate to create molecular diversity in novel hybrids [27]. |

| Morpholine | A versatile heterocycle used to improve pharmacokinetic properties and introduce biological activity [27]. | Joined to the C-6 position of a benzylated pyrimidine ring to create novel pyrimidine-morpholine anticancer hybrids [27]. |

| Triethylamine (TEA) | A commonly used base to scavenge acids (e.g., HBr) generated during reactions like alkylation or cycloaddition [25]. | Used as a base in the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction to generate the nitrile oxide and accept protons [25]. |

| Mueller-Hinton Agar | A standardized growth medium used for antimicrobial susceptibility testing via the disk diffusion method [26]. | Used to evaluate the antibacterial potential of synthesized 5-methylisoxazole derivatives against pathogens like P. aeruginosa and S. aureus [26]. |

| Docosapentaenoic acid | Docosapentaenoic Acid (DPA) | High-purity Docosapentaenoic acid for research. Explore its role in cardiovascular, neuro, and inflammation studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| CDK9-IN-30 | CDK9-IN-30, MF:C16H20FNO3, MW:293.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The disciplines of chemical space exploration, retrosynthesis, and in-silico prediction are rapidly maturing and converging into a unified, AI-driven workflow for synthetic chemistry and drug discovery. Initiatives like the multi-institutional NSF Center for Computer Assisted Synthesis (C-CAS) exemplify this trend, bringing together experts from synthetic chemistry, computer science, and AI to create tools that can predict reaction outcomes "within a minute" and scale experimentation to tens of thousands of reactions [7]. The ultimate goal is a profound acceleration of the research cycle, potentially reducing development time from a decade to a single year and slashing costs from millions to below $100,000 [7]. As these computational methodologies become more deeply integrated with automated robotic systems, they form the backbone of the emerging "self-driving lab," marking a fundamental shift towards a more predictive, efficient, and innovative era in chemical research. For today's researchers and drug development professionals, proficiency in these key concepts is no longer optional but essential for leading the next wave of discovery.

AI in Action: Methodologies Powering Automated Synthesis and Molecular Design

The field of synthetic chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, transitioning from reliance on expert intuition and trial-and-error approaches to data-driven, intelligence-guided processes. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are now pivotal in reshaping the landscape of molecular design, offering unprecedented capabilities in predicting reaction outcomes, optimizing selectivity, and accelerating catalyst discovery [28] [29]. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in the development of robust predictive models for reaction outcome, yield, and selectivity forecasting—tasks that have long challenged conventional computational methods and human expertise alone. These AI-powered tools seamlessly integrate data-driven algorithms with fundamental chemical principles to redefine molecular design, promising accelerated research, enhanced sustainability, and innovative solutions to chemistry's most pressing challenges [28] [30].

The integration of AI throughout the molecular catalysis workflow fosters innovation at every stage, from retrosynthetic analysis that proposes optimal synthetic routes to AI-guided catalyst design informed by chemical knowledge and historical data [29]. In reaction studies, AI significantly accelerates the optimization of conditions and delineates reaction scope and limitations. Furthermore, advanced autonomous experimentation enables chemists to perform experiments with markedly greater efficiency and reproducibility [29]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions driving this transformation, with particular focus on applications relevant to drug development professionals and research scientists.

Core Methodologies in AI-Based Reaction Prediction

Representation Approaches for Chemical Reactions

A fundamental challenge in applying AI to chemistry lies in selecting appropriate mathematical representations for molecules and reactions. The choice of representation significantly influences model performance, interpretability, and generalizability [31].

Table 1: Molecular and Reaction Representation Methods in AI Chemistry

| Representation Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Compatible Model Architectures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Fingerprints | Binary vectors indicating presence/absence of specific substructures [32] | Fast computation; well-established | May lose certain chemical information due to limited predefined substructures [32] | Random Forest, Feedforward Neural Networks |

| SMILES Strings | Text-based notation of molecular structure [31] | Simple, compact string representation | Does not explicitly encode molecular graph topology | Transformer Models, Sequence-to-Sequence Models |

| 2D Molecular Graphs | Atoms as nodes, bonds as edges in a graph structure [32] [31] | Naturally represents molecular topology | Limited to explicit structural information only | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) |

| 3D Conformations | Atomic coordinates in 3D space [31] | Captures stereochemistry and conformational effects | Computationally expensive to generate | 3D-CNNs, Specialized GNNs |

| Reaction Fingerprints (e.g., DRFP) | Binary fingerprints derived from reaction SMILES via hashing [32] | Easy to build for reactions | May lose nuanced chemical information | Standard Classifiers, Regression Models |

| Quantum-Mechanical (QM) Descriptors | Electronic/steric parameters from DFT calculations [32] | High interpretability; mechanism-informed | Requires deep mechanistic understanding; computationally intensive [32] | Random Forest, Multivariate Regression |

| Bond-Electron Matrix | Represents electrons and bonds in a reaction [15] | Enforces physical constraints (mass/charge conservation) [15] | Less common; requires specialized model architectures | Flow Matching Models (e.g., FlowER [15]) |

For reaction prediction tasks, researchers must also decide how to represent the complete reaction context, including solvents, catalysts, and other condition-specific factors. While there is little standardization in representing these categorical reaction conditions, concatenation of molecular representations of all components remains a common approach [31].

Emerging Architectures and Physical Constraint Integration

Early attempts to harness large language models (LLMs) for reaction prediction faced significant limitations, primarily because they were not grounded in fundamental physical principles, leading to violations of conservation laws [15]. A groundbreaking approach developed at MIT addresses this critical limitation through the FlowER (Flow matching for Electron Redistribution) model, which uses a bond-electron matrix based on 1970s work by chemist Ivar Ugi to explicitly track all electrons in a reaction [15]. This representation uses nonzero values to represent bonds or lone electron pairs and zeros to represent their absence, ensuring conservation of both atoms and electrons throughout the prediction process [15].

The GraphRXN framework represents another significant architectural advancement, utilizing a modified communicative message passing neural network to generate reaction embeddings without predefined fingerprints [32]. This graph-based model directly takes two-dimensional reaction structures as inputs and processes each molecular graph through three key steps: message passing, information updating, and readout using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) to aggregate node vectors into a graph vector [32]. The resulting molecular feature vectors are then aggregated into a final reaction vector through either summation or concatenation operations.

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Implementation

Protocol: Implementing the GraphRXN Framework

The GraphRXN methodology provides a universal graph-based neural network framework for accurate reaction prediction, particularly when integrated with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data [32].

Experimental Workflow:

- Input Preparation: Represent each reaction component (reactants, products) as a directed molecular graph G(V,E) with node features (Xv, ∀v∈V) and edge features (Xev,w, ∀ev,w∈E) [32].

- Message Passing: For each node v at step k, obtain an intermediate message vector mk(v) by aggregating the hidden state of its neighboring edges at the previous step hk-1(eu,v).

- Information Updating: Concatenate the previous hidden state hk-1(v) with the current message mk(v) and process through a communicative function to obtain the current node hidden state hk(v).

- Edge State Update: For each edge ev,w at step k, calculate its intermediate message vector mk(ev,w) by subtracting the previous edge hidden states hk-1(ev,w) from the hidden state of its starting node hk(v). Add the initial edge state h0(ev,w) and weighted vector W•mk(ev,m), then apply a ReLU activation function to form the current edge state hk(ev,w) [32].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 for K iterations to capture sufficient molecular context.

- Node Embedding: After K iterations, obtain the message vector m(v) by aggregating hidden states hK(eu,v) of neighboring edges. Combine m(v), current node hidden state hK(v), and initial node information x(v) through a communicative function to form the final node embedding h(v).

- Readout: Use a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) to aggregate node vectors into a graph vector, with the feature vector length typically set to 300 bits [32].

- Reaction Vector Formation: Aggregate molecular feature vectors into one reaction vector by either summation or concatenation (GraphRXN-sum and GraphRXN-concat respectively).

- Model Training: Correlate reaction features with the output (e.g., yield, selectivity) via a dense layer neural network, using HTE data for training and validation.

Protocol: Implementing Physical Constraint Integration with FlowER

The FlowER system addresses a critical limitation in previous AI models by incorporating physical constraints such as conservation of mass and electrons [15].

Experimental Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Curate a dataset of atom-mapped reactions, such as the USPTO database containing over a million chemical reactions. Note that certain metals and catalytic reactions may be underrepresented and require expansion [15].

- Bond-Electron Matrix Representation: Represent each reaction using the Ugi bond-electron matrix system, where nonzero values represent bonds or lone electron pairs and zeros represent absence thereof [15].

- Model Architecture: Implement a flow matching architecture specifically designed for electron redistribution, ensuring that the model tracks all chemicals and how they transform throughout the entire reaction process from start to end.

- Training: Train the model to predict electron flow and bond transformations while strictly adhering to conservation principles.

- Validation: Evaluate model performance using both quantitative metrics (accuracy, validity) and qualitative assessment by expert chemists. The model should demonstrate the ability to generalize to previously unseen reaction types while maintaining physical realism [15].

- Application: Deploy the trained model for predicting reactivity, mapping out reaction pathways, and assisting in reaction discovery for applications in medicinal chemistry, materials discovery, and electrochemical systems [15].

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Assessment

Rigorous evaluation of AI models for reaction prediction requires multiple metrics to assess accuracy, validity, and practical utility. The following table summarizes performance data across key methodologies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI Reaction Prediction Models

| Model/Approach | Key Architecture | Dataset | Primary Task | Reported Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GraphRXN [32] | Graph Neural Network (Message Passing) | In-house HTE Buchwald-Hartwig data | Yield Prediction | R² = 0.712 (on in-house data) | Learns reaction features directly from graph structures without predefined fingerprints |

| FlowER [15] | Flow Matching with Bond-Electron Matrix | USPTO (1M+ reactions) | Reaction Outcome Prediction | "Massive increase in validity and conservation"; matching or better accuracy vs. existing approaches [15] | Ensures mass and electron conservation; provides realistic predictions |

| Graph-Convolutional Networks [18] | Graph-Convolutional Neural Networks | Not specified | Reaction Outcome Prediction | "High accuracy" with interpretable mechanisms [18] | Offers model interpretability alongside predictions |

| ML with QM Descriptors [32] | Random Forest with DFT-calculated descriptors | Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling | Yield Prediction | "Good prediction performance" [32] | High interpretability; mechanism-informed |

| Multiple Fingerprint Features (MFF) [32] | Multiple fingerprint features concatenation | Various enantioselectivity datasets | Enantioselectivity & Yield Prediction | "Good results" for enantioselectivities and yields [32] | Comprehensive molecular representation |

Beyond these quantitative metrics, the FlowER system demonstrates capability in generalizing to previously unseen reaction types while maintaining physical realism—a critical advancement for practical deployment in pharmaceutical and materials research [15]. Template-based methods for retrosynthesis have demonstrated remarkable practical utility, with systems like Chemitica generating synthetic routes that experienced chemists cannot distinguish from literature-reported routes in Turing tests [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of AI-driven reaction prediction requires both computational tools and experimental resources for training data generation and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI Reaction Prediction

| Item/Resource | Function/Role | Application Context | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [32] | Generates high-quality, consistent reaction data with both successful and failed examples | Data generation for model training; validation of AI predictions | Critical for building forward reaction prediction models; ensures data integrity |

| USPTO Database [15] [31] | Provides large-scale reaction data from U.S. patents (~1 million reactions) | Training data for retrosynthesis and reaction outcome prediction | Contains atom-mapped reactions; may underrepresent certain reaction classes |

| Reaxys/SciFinder [29] | Comprehensive databases of published reactions and experimental data | Traditional retrosynthetic planning; data source for template extraction | Limited to recorded reactions; may not guide novel transformations |