Accuracy and Precision in Organic Chemistry: A Modern Framework for Method Evaluation, AI Integration, and Regulatory Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating accuracy and precision in modern organic chemistry methods, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Accuracy and Precision in Organic Chemistry: A Modern Framework for Method Evaluation, AI Integration, and Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating accuracy and precision in modern organic chemistry methods, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It bridges foundational statistical concepts with cutting-edge applications in machine learning and high-throughput experimentation (HTE). The content explores methodological implementations, from traditional comparison studies to AI-driven predictive models for kinetics and synthesis. It offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls in method validation and optimization. Finally, it details rigorous validation protocols and comparative study designs aligned with regulatory standards like ICH Q2(R2), ensuring data reliability for biomedical and clinical research applications.

Core Principles: Defining Accuracy, Precision, and Bias in Chemical Measurement

In organic chemistry methods research, the evaluation of analytical techniques and predictive models hinges on robust, quantifiable metrics. The terms accuracy, precision, and recall are fundamental to this process, each providing a distinct lens through which scientists can assess performance. While accuracy and precision are long-established concepts in analytical chemistry, recall is increasingly vital with the integration of machine learning into chemical research. Understanding the distinction between these metrics is not merely academic; it directly impacts the reliability of research outcomes in drug development and other chemical fields. Accuracy refers to the closeness of a measurement to its true value, precision describes the reproducibility of measurements, and recall quantifies the ability to identify all relevant positive instances in a dataset. This guide provides a structured comparison of these metrics, grounded in the context of organic chemistry research, to empower scientists in selecting the right tools for method validation and evaluation.

Defining the Metrics: Core Concepts and Chemical Context

Accuracy

In analytical chemistry, accuracy signifies the closeness of agreement between a measured value and its true value. As defined by the International Vocabulary of Basic and General Terms in Metrology (VIM), it is a "qualitative concept" describing how close a measurement result is to the true value, which is inherently indeterminate [1]. Accuracy is often estimated through quantitative error analysis, where error is defined as the difference between the measured result and a conventional true value or reference value [1]. In laboratory practice, a common technique for determining accuracy is the spike recovery method, where a known quantity of a target analyte is added to a sample matrix, and the analytical method's ability to recover the added amount is measured [1]. For chemical measurements, accuracy can be influenced by various factors, including extraction efficiency, analyte stability, and the adequacy of chromatographic separation [1].

Precision

Precision describes the agreement among a set of replicate measurements under specified conditions, reflecting their reproducibility [1] [2]. The VIM further distinguishes precision using the terms repeatability (agreement under identical conditions) and reproducibility (agreement under changed conditions) [1]. Precision is typically expressed statistically through measures like standard deviation or deviation from the arithmetic mean of the dataset [2]. A critical principle in analytical chemistry is that good precision does not guarantee good accuracy, as high-precision measurements can still be biased by unaccounted systematic errors [2]. In the context of machine learning for chemical research, such as predicting reaction outcomes, precision translates to the reliability of a model's positive predictions [3].

Recall

Recall, also known as sensitivity, is a metric paramount in classification tasks. It measures the proportion of actual positive cases that a model correctly identifies [4]. Recall is crucial when the cost of missing a positive instance (false negative) is high [5] [4]. For example, in a chemical context, this could involve a model screening for potentially toxic compounds or identifying promising drug candidates from a large library; missing a true positive could have significant safety or financial implications. A model with high recall effectively minimizes false negatives, ensuring that most relevant instances are captured, even at the potential cost of including some false positives [4].

The table below summarizes the core definitions, mathematical formulas, and primary chemical applications of accuracy, precision, and recall.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Chemical Applications of Accuracy, Precision, and Recall

| Metric | Core Question | Mathematical Formula | Primary Chemical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | How close is a measurement to the true value? [1] | (Established via error analysis: Error = Measured Value - True Value [1]) | Validation of quantitative analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, ICP); determining systematic error (bias) [1]. |

| Precision | How reproducible are the measurements? [2] | Standard Deviation or other measures of data spread [2] | Assessing repeatability and reproducibility of analytical protocols; quality control of instrument performance [1] [2]. |

| Recall | Of all the actual positives, how many did we find? [4] | Recall = TP / (TP + FN) [4] | Evaluating AI-based screening models (e.g., for reaction prediction or compound bioactivity) where missing a positive is costly [6] [4]. |

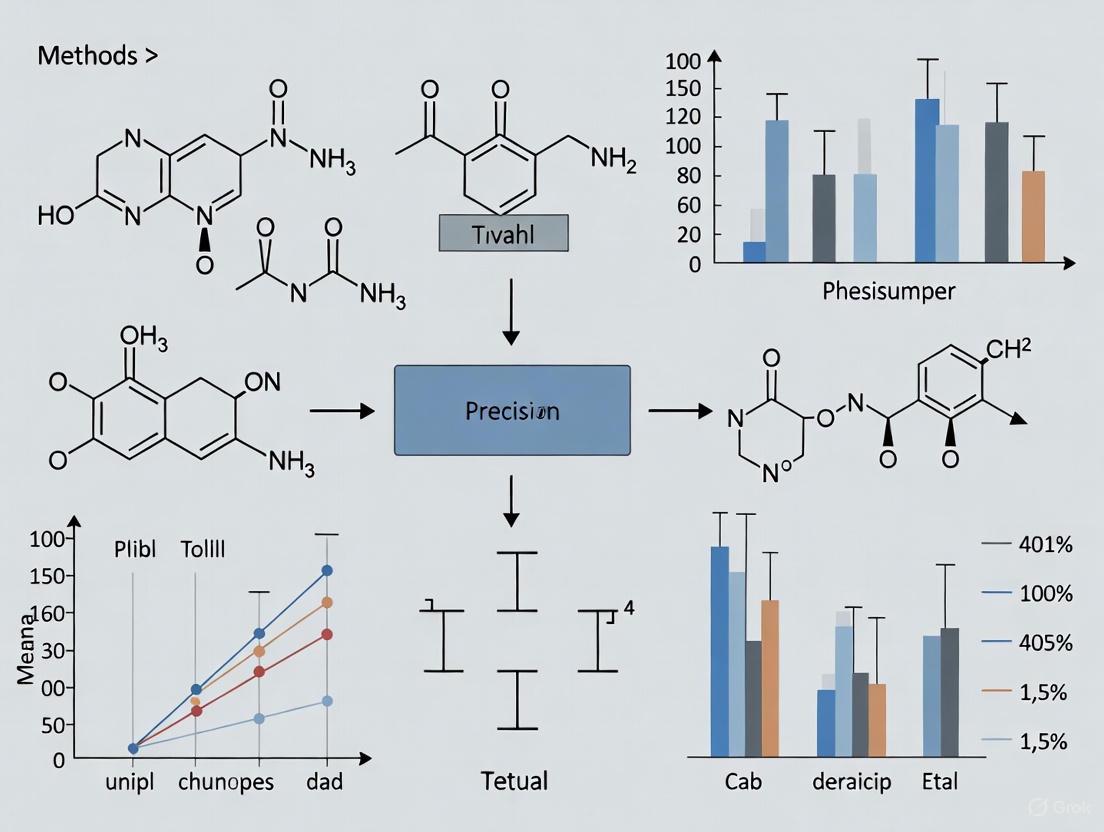

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflows associated with evaluating and applying these three metrics in a chemical research context.

Diagram 1: Evaluation Workflow for Chemical Methods

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Protocol for Determining Accuracy via Spike Recovery

The spike recovery experiment is a standard practice for estimating the accuracy of a quantitative analytical method in natural products and pharmaceutical chemistry [1].

- Step 1: Obtain Reference Material: Secure a certified reference material (CRM) or a standard of the target analyte with a verified purity declaration [1].

- Step 2: Prepare Samples: Prepare multiple samples of the matrix (e.g., botanical raw material). The matrix should ideally contain the target analyte naturally. Prepare parallel sets: one unspiked and one spiked with a known amount of the pure reference material [1].

- Step 3: Spike Concentration: The FDA guidance suggests spiking the matrix at 80%, 100%, and 120% of the expected analyte concentration to assess accuracy across a relevant range. Perform each level in triplicate [1].

- Step 4: Analysis and Calculation: Analyze both spiked and unspiked samples following the full analytical procedure (extraction, chromatography, etc.). The theoretical amount in the spiked sample is the sum of the naturally occurring analyte (from the unspiked analysis) plus the amount added. The percentage recovery is calculated as: (Amount Found in Spiked Sample / Theoretical Amount) × 100% [1].

Protocol for Assessing Precision

Precision is evaluated by measuring the dispersion of results from repeated measurements [2].

- Step 1: Define Conditions: Specify the conditions for the test—either repeatability (same instrument, analyst, location, short time period) or reproducibility (changed conditions such as different analysts, instruments, or days) [1].

- Step 2: Perform Replicate Measurements: Carry out a sufficient number of replicate measurements (n) of a homogeneous sample under the specified conditions. A minimum of 6-10 replicates is common for estimating standard deviation reliably.

- Step 3: Calculate Statistical Measures: Calculate the standard deviation and the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the replicate measurements. A smaller standard deviation indicates higher precision [2].

Protocol for Calculating Recall in a Chemical Classification Model

Recall is calculated from the confusion matrix of a binary classification model's output [3] [4].

- Step 1: Define Positive Class: Define the "positive" class relevant to the chemical problem (e.g., "biologically active compound," "successful reaction pathway").

- Step 2: Generate Confusion Matrix: After running the model on a test dataset with known labels, tabulate the results into a confusion matrix, which counts:

- Step 3: Apply Formula: Calculate Recall using the formula: Recall = TP / (TP + FN) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions required for the experiments and validation procedures discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Validation

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | A substance with one or more properties certified by a validated procedure, providing a traceable standard to establish accuracy and calibrate instruments [1]. |

| Chromatographic Standards | High-purity chemical compounds used to create calibration curves for quantitative analysis, essential for both accuracy and precision determination [1]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Sample | A stable, homogeneous sample analyzed alongside test samples to monitor the analytical method's performance and ensure ongoing precision and absence of systematic error [1] [2]. |

| Appropriate Matrix Blanks | Samples of the material being analyzed that are devoid of the target analyte (or have a known low background). Used in spike recovery experiments to determine accuracy [1]. |

| Calibrated Volumetric Ware | Precisely calibrated glassware (e.g., pipettes, flasks) critical for preparing accurate solutions and standards, directly impacting measurement precision and accuracy [1] [2]. |

| QL-X-138 | QL-X-138, CAS:1469988-63-3, MF:C25H19N5O2, MW:421.4 g/mol |

| DM1-SMe | DM1-SMe, MF:C36H50ClN3O10S2, MW:784.4 g/mol |

Understanding Bias and Repeatability in Method-Comparison Studies

In the development and validation of organic chemistry methods, researchers and drug development professionals frequently need to determine whether a new analytical method can satisfactorily replace an established one. This fundamental question is addressed through method-comparison studies, which systematically evaluate the equivalence of two measurement procedures. The core clinical—and by extension, analytical—question is one of substitution: Can one measure a given analyte with either Method A or Method B and obtain the same results? The answer hinges on rigorously assessing the bias (systematic difference) and repeatability (random variation) between the two methods [7].

The terminology used in such studies is often inconsistent in the literature, making clarity essential. Bias refers to the mean overall difference in values obtained with two different methods. Repeatability, a key aspect of precision, describes the degree to which the same method produces the same results on repeated measurements under identical conditions. It is a necessary, but insufficient, condition for agreement between methods; if one or both methods do not give repeatable results, assessing their agreement is meaningless [7]. This guide provides a structured comparison of performance evaluation in method-comparison studies, complete with experimental protocols and data interpretation frameworks.

Core Principles: Bias, Precision, and Repeatability

Foundational Concepts

- Bias: The mean difference between values obtained from a new method and an established one. When differences are calculated as (new method minus established method), a positive bias indicates the new method gives higher values, on average. Bias estimates systematic error or inaccuracy [7] [8] [9].

- Precision: The closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions. It is a measure of random error [7] [10].

- Repeatability: A specific measure of precision under conditions where independent test results are obtained with the same method on identical test items in the same laboratory by the same operator using the same equipment within short intervals of time [10].

- Accuracy: The combination of both trueness (inverse of bias) and precision. A method is accurate if it is both unbiased and precise [10].

The Relationship Between Concepts

The relationship between accuracy, trueness (bias), and precision is foundational. The total error of an individual result is the sum of a random component (related to precision) and a systematic component (bias). A method can be precise but inaccurate if it has a significant bias, or unbiased but inaccurate if it is imprecise [10]. The following conceptual diagram illustrates this relationship and the experimental workflow for a method-comparison study:

Experimental Design for Method-Comparison Studies

Key Design Considerations

A well-designed experiment is crucial for obtaining reliable results in a method-comparison study [7] [9]. Several key factors must be considered:

- Selection of Measurement Methods: The two methods must measure the same analyte or property. Comparing a method measuring blood glucose with one measuring oxygen saturation, for example, is inappropriate, even if the results are clinically correlated [7].

- Timing of Measurement: Measurements should be made simultaneously or nearly simultaneously to ensure both methods are measuring the same quantity. The definition of "simultaneous" depends on the stability of the analyte. For stable analytes, sequential measurements within a short time frame may be acceptable, with the order of measurement randomized to eliminate sequence effects [7].

- Number of Measurements: A sufficient number of paired measurements is needed to decrease the likelihood of chance findings and to ensure data are normally distributed, validating the use of standard bias and precision statistics. A minimum of 40 patient specimens is recommended, with 100 or more being preferable to identify unexpected errors due to interferences or sample matrix effects [8] [9].

- Conditions of Measurement: The study should be conducted over the entire physiological or analytically relevant range of values for which the methods will be used. Using a large sample size and repeated measures across changing conditions helps achieve this objective [7]. The experiment should cover multiple days (at least 5) and multiple analytical runs to mimic real-world conditions and incorporate routine sources of variation [8] [9].

Sample and Data Collection Protocol

The following table summarizes the key experimental parameters for a robust method-comparison study:

Table 1: Experimental Design Parameters for Method-Comparison Studies

| Parameter | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Minimum of 40, preferably 100-200 specimens [8] [9] | Provides reliable estimates, detects outliers and matrix effects |

| Concentration Range | Cover the entire clinically/analytically meaningful range [7] [9] | Ensures evaluation across all relevant conditions |

| Measurement Replication | Duplicate measurements for both methods are ideal [8] | Minimizes random variation; identifies sample mix-ups |

| Study Duration | At least 5 different days, multiple analytical runs [8] [9] | Captures intermediate precision (day, operator, calibration effects) |

| Sample Stability | Analyze within 2 hours of each other, or within known stability window [8] | Prevents differences due to sample degradation |

| Sample Sequence | Randomize sample sequence for analysis [9] | Avoids carry-over effects and time-dependent biases |

Data Analysis and Statistical Procedures

Visual Data Inspection

The first step in data analysis is visual inspection of the data patterns using graphs, which can reveal outliers, artifacts, and the overall relationship between the methods [7] [9].

- Scatter Plots: A scatter diagram plots the values from the established method (x-axis) against the values from the new method (y-axis). This helps visualize the variability and agreement between the methods across the measurement range. The plot should be inspected for gaps in the data range, the presence of outliers, and the general linearity of the relationship [9].

- Bland-Altman Plots: Also known as difference plots, these are a key tool for assessing agreement. The average of each pair of measurements ( (Method A + Method B)/2 ) is plotted on the x-axis, and the difference between the methods ( (Method B - Method A) ) is plotted on the y-axis. This plot allows for direct visualization of the bias (the mean difference) and the limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 standard deviations of the differences) [7]. The plot makes it easy to see if the differences are random and whether their magnitude is related to the concentration of the analyte.

Statistical Calculations

After visual inspection, statistical calculations are used to quantify the bias and agreement.

- Bias and Precision Statistics: The overall bias is calculated as the mean of the differences between the two methods. The standard deviation (SD) of these differences is a measure of their variability. The limits of agreement are defined as Bias ± 1.96 SD, representing the range within which 95% of the differences between the two methods are expected to fall [7].

- Regression Analysis: For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression is preferable. It provides an equation (Y = a + bX) that describes the relationship between the methods, where the slope (b) indicates a proportional difference, and the y-intercept (a) indicates a constant difference. The systematic error at any critical decision concentration (X~c~) can be calculated as SE = (a + bX~c~) - X~c~ [8].

- Inappropriate Statistics: Correlation coefficient (r) is often misused in method-comparison studies. A high correlation only indicates a strong linear association, not agreement. Two methods can be perfectly correlated yet have a large, clinically unacceptable bias. Similarly, t-tests are not ideal, as they may detect statistically significant but clinically irrelevant differences with large sample sizes, or fail to detect relevant differences with small sample sizes [9].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the statistical analysis workflow:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and tools required for conducting a rigorous method-comparison study.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Method-Comparison Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides the highest metrological quality reference value with stated uncertainty for assessing trueness and bias [10]. | CRM with certified analyte concentration and uncertainty statement. |

| Reference Materials (RMs) | Well-characterized material used for accuracy assessment when a CRM is not available [10]. | Laboratory-characterized material; proficiency testing material. |

| Stable Patient/Test Specimens | The core sample used for the paired comparison. Must be stable for the duration of the analysis of both methods [8]. | Human serum; processed reaction mixtures; synthesized compound solutions. |

| Statistical Software | Used for data analysis, graphical presentation, and calculation of bias, precision, and limits of agreement [7] [9]. | MedCalc; R; Python (with SciPy/StatsModels); specialized CLSI-compliant software. |

| Calibration Standards | To ensure both the established and new methods are properly calibrated before and during the comparison study. | Traceable to national/international standards where possible. |

| Rapamycin-d3 | Rapamycin-d3, MF:C51H79NO13, MW:917.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HJC0152 | HJC0152, MF:C15H14Cl3N3O4, MW:406.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Interpreting Results and Making Decisions

The final step is to interpret the statistical findings in the context of the analytical problem. The calculated bias and limits of agreement must be compared against pre-defined, clinically or analytically acceptable limits. These acceptability criteria should be based on the effect of analytical performance on clinical outcomes, biological variation of the measurand, or state-of-the-art performance [9]. If the estimated bias and the limits of agreement fall within the acceptable range, the two methods can be considered equivalent for the intended purpose. If the bias or the range of disagreements is too large, the methods cannot be used interchangeably, and the new method may require further investigation or refinement [7] [8].

The process of accuracy assessment culminates in a statistical comparison that considers both the laboratory's mean value and the uncertainty of the reference value. A method is deemed to have no significant bias if the calculated statistic ( t{cal} = \frac{| \bar{x}{lab} - x{ref} |}{\sqrt{s{lab}^2/n{lab} + u{ref}^2}} ) is less than the critical t-value for a chosen significance level (α) [10]. This structured approach to interpretation ensures that decisions regarding method adoption are based on objective, statistically sound evidence.

The Role of Confusion Matrix Metrics (TP, TN, FP, FN) in Classification of Reaction Outcomes

In organic chemistry methods research, the accurate prediction of reaction outcomes is paramount for accelerating drug development and material discovery. As machine learning (ML) models become integral to this process, robust evaluation frameworks are essential to distinguish truly predictive models from those that are merely accurate by chance. The confusion matrix, a simple yet powerful diagnostic tool, provides this framework by breaking down predictions into four fundamental categories: True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) [11] [12]. This decomposition moves beyond simplistic accuracy metrics, offering chemists a detailed understanding of where a model succeeds and fails. Within the broader thesis of accuracy and precision evaluation, the confusion matrix offers a nuanced view essential for applications where the cost of a false positive (e.g., pursuing a non-viable reaction pathway) differs greatly from that of a false negative (e.g., overlooking a high-yielding reaction) [13]. This guide objectively compares the performance of different modeling strategies as measured by confusion matrix-derived metrics, providing researchers with the data needed to select and refine predictive tools for synthetic planning.

Core Concepts: Deconstructing the Confusion Matrix

The Anatomy of a Confusion Matrix

A confusion matrix is a specific table layout that visualizes the performance of a classification algorithm [11]. For a binary classifier—such as predicting whether a reaction will be "successful" or "unsuccessful"—the matrix is a 2x2 grid defined as follows:

- True Positive (TP): The model correctly predicts a positive outcome. Example: A reaction that is experimentally successful is predicted to be successful. [12] [14]

- True Negative (TN): The model correctly predicts a negative outcome. Example: A failed reaction is predicted to be unsuccessful. [12] [14]

- False Positive (FP): The model incorrectly predicts a positive outcome. Example: A failed reaction is incorrectly predicted to be successful. This is also known as a Type I error [12] [15].

- False Negative (FN): The model incorrectly predicts a negative outcome. Example: A successful reaction is incorrectly predicted to fail. This is also known as a Type II error [12] [15].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a model's predictions, the ground truth, and the four outcomes of the confusion matrix.

Key Metrics Derived from the Confusion Matrix

The raw counts of TP, TN, FP, and FN are used to calculate critical performance metrics that address different evaluation needs [11] [16] [15].

- Accuracy: Overall, how often the classifier is correct.

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)[12] [14] - Precision: When the model predicts a positive, how often is it correct? This measures the quality of positive predictions.

Precision = TP / (TP + FP)[16] [12] - Recall (Sensitivity): When the actual outcome is positive, how often do we predict positive? This measures the model's ability to capture all positive instances.

Recall = TP / (TP + FN)[16] [12] - Specificity: When the actual outcome is negative, how often do we predict negative?

Specificity = TN / (TN + FP)[16] [12] - F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both concerns. This is especially useful for imbalanced datasets [16] [14].

F1-Score = 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall)[12]

Performance Comparison of Classification Strategies in Reaction Prediction

Different modeling approaches for reaction outcome prediction offer varying performance profiles, as quantified by confusion matrix metrics. The table below summarizes experimental data from comparative studies, providing a clear overview of model efficacy.

Table 1: Performance comparison of different modeling approaches on various reaction datasets.

| Model / Strategy | Reaction Dataset | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consensus QSAR (Majority Voting) [17] | Androgen Receptor (AR) Binding (4,040 molecules) | NER*: ~80% (est. from fig.)Sensitivity (Sn): ~64% (median)Specificity (Sp): ~88% (median) | *Non-Error Rate (NER) or Balanced Accuracy = (Sn + Sp)/2. Consensus of 34 individual models showed higher accuracy and broader chemical space coverage than individual models. |

| Individual QSAR Models [17] | Androgen Receptor (AR) Binding | NER: ~75% (median)Sensitivity (Sn): ~64% (median)Specificity (Sp): ~88% (median) | Individual models showed high variability. Top-performing single models (NER >80%) had limited applicability domain (coverage 13-69%). |

| Graph Neural Network (GraphRXN) [18] | Buchwald-Hartwig Amination (Public HTE) | R²: >0.71 (vs. baseline)Accuracy: Superior to baseline models (exact values not provided) | A graph-based framework using molecular structures as input. Evaluated on public high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data. |

| Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) [19] | Buchwald-Hartwig Cross-Coupling (3,955 reactions) | R²: ~0.71Performance: Comparable to GNNs | Combines neural networks with Gaussian processes. Provides predictive performance similar to GNNs but with the added advantage of uncertainty quantification. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

To ensure the fair and objective comparison of predictive models as shown in Table 1, standardized experimental protocols for dataset preparation, model training, and performance evaluation are critical.

Data Sourcing and Curation

- Public High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Datasets: Studies often use publicly available datasets, such as those for Buchwald-Hartwig amination reactions [18] [19]. These datasets contain thousands of reactions with consistent experimental measurements, including both successful and failed reactions, which is crucial for building robust binary classifiers [18].

- Collaborative Project Data: Large-scale collaborative projects, like the Collaborative Modeling Project of Androgen Receptor Activity (CoMPARA), generate specialized datasets. For example, the CoMPARA project provided data on 4,040 molecules for AR binding, agonism, and antagonism, which was used to train and evaluate over 20 individual QSAR models and their consensus [17].

- In-House HTE Data: Some research groups use robotic platforms to generate their own high-quality, consistent datasets for specific reaction types, which are then used for internal model training and validation [18].

Model Training and Validation Framework

A rigorous methodology is required to obtain the performance metrics listed in Table 1.

- Data Splitting: The available data is randomly split into three sets: a training set (~70-80%) for model development, a validation set (~10-15%) for hyperparameter tuning, and a held-out test set (~10-20%) for the final, unbiased evaluation of performance [19].

- Model Training: Individual models (e.g., QSAR, GNNs) are trained on the training set. For consensus strategies, predictions from multiple individual models are aggregated using methods like majority voting [17].

- Performance Calculation: The trained model makes predictions on the test set. These predictions (e.g., "active"/"inactive") are compared against the experimental ground truth to populate the confusion matrix [11]. Metrics like Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy are then calculated from the TP, TN, FP, and FN counts.

- Cross-Validation: To ensure reliability, the process of splitting and evaluation is often repeated multiple times (e.g., 10 independent runs), with the final performance reported as an average across these runs [19].

Table 2: Key computational and experimental reagents for building and evaluating reaction outcome predictors.

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Reaction Outcome Prediction | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors [19] | Non-learned numerical representations of molecular structure (e.g., electronic, spatial properties). Used as input for traditional ML models. | Concatenated descriptors for reactants served as input for Deep Kernel Learning models [19]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., Morgan/ECFP, DRFP) [19] | Sparse, high-dimensional bit vectors that encode molecular structure or reaction transforms. | DRFP fingerprints generated from reaction SMILES were used as input for yield prediction models [19]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [18] [19] | Deep learning models that learn feature representations directly from molecular graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges). | The GraphRXN framework uses GNNs to learn from 2D reaction structures for forward reaction prediction [18]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [18] | A technique for performing a large number of experiments in parallel, generating consistent and high-quality data for model training. | Used to generate in-house datasets of Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling reactions to train and validate GraphRXN [18]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) [17] | An assessment of whether a prediction for a given molecule can be considered reliable based on the model's training data. | Used to filter predictions from individual QSAR models, improving consensus model reliability [17]. |

The deployment of confusion matrix metrics provides an indispensable, granular framework for evaluating the performance of classification models in organic chemistry. By moving beyond accuracy to examine precision, recall, and specificity, researchers can select models that are not just statistically accurate but also functionally fit for purpose—whether that purpose is to avoid costly false positives in lead optimization or to minimize false negatives in reaction discovery. As the data demonstrates, strategies like consensus modeling and advanced deep learning architectures offer significant performance benefits. The continued integration of these robust evaluation practices with high-quality experimental data will be crucial for advancing the precision and reliability of predictive methods in synthetic organic chemistry and drug development.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three foundational statistical measures—Standard Deviation, Confidence Intervals, and Limits of Agreement—used to evaluate the accuracy and precision of analytical methods in organic chemistry research.

Defining the Statistical Measures

The following table summarizes the core purpose, key characteristics, and primary context for each of the three statistical measures.

| Measure | Core Purpose | Key Characteristics | Primary Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation | Quantifies the variability or dispersion of data points around the mean. [20] | - Describes precision (random error).- Single value for a dataset.- Population parameter (σ) or sample estimate (s). | Used internally to assess the repeatability of a single method. |

| Confidence Interval (CI) | Estimates a range that is likely to contain the true population parameter (e.g., the mean). [20] | - Accounts for sampling error.- Width depends on sample size and confidence level.- Used for hypothesis testing. | Infers the true value from sample data; expresses uncertainty in an estimate. |

| Limits of Agreement (LoA) | Estimates the interval within which most differences between two measurement methods are expected to lie. [21] | - Assesses agreement between two methods.- Captures both systematic bias and random error.- Result is a range of differences. | Method comparison studies to assess interchangeability or total error. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Confidence Interval for a Mean Value

Confidence Intervals (CIs) are used to express the uncertainty in a sample estimate, such as the mean result of repeated experiments. A 95% CI means that if the same study were repeated many times, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true population mean. [20]

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Data Collection: Perform the analytical measurement (e.g., concentration assay) on a representative sample

nnumber of times. - Calculate Sample Mean (( \bar{x} )) and Standard Deviation (s):

- Mean: ( \bar{x} = \frac{\sum xi}{n} )

- Standard Deviation: ( s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum (xi - \bar{x})^2}{n-1} )

- Determine the Critical Value: For a 95% CI and a sample size of

n=40, use the Z-distribution (approximation for large n). The critical Z-value for 95% confidence is 1.960. [20] - Calculate the Standard Error (SE): ( SE = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} )

- Compute the Margin of Error (MoE): ( MoE = Z_{\alpha/2} \times SE )

- Determine the Confidence Interval:

- Lower Limit: ( \bar{x} - MoE )

- Upper Limit: ( \bar{x} + MoE )

Example from a simulated dataset: [20]

- Objective: Estimate the true mean weight of a synthesized compound.

- Data:

n = 40, mean (\bar{x}) = 72.5 mg, standard deviation (s) = 8.4 mg. - Calculation:

SE = 8.4 / √40 ≈ 1.33MoE = 1.960 * 1.33 ≈ 2.61- 95% CI = (72.5 - 2.61, 72.5 + 2.61) = (69.89, 75.11) mg

This workflow outlines the key steps to calculate a confidence interval for a sample mean, from data collection to the final range.

Limits of Agreement for Method Comparison

The Limits of Agreement (LoA), popularized by Bland and Altman, is a method to assess the agreement between two measurement techniques. It is crucial for evaluating if a new, cheaper, or faster method can replace an established one. [22] [23]

Key Underlying Assumptions of the LoA Method: [22]

- The two measurement methods have the same precision (equal measurement error variances).

- The precision is constant across the measurement range (homoscedasticity).

- The systematic difference (bias) between the methods is constant.

Experimental Protocol:

- Paired Data Collection: Measure the same set of

nsamples or subjects using both Method A (e.g., a reference method) and Method B (the new method). - Calculate Differences: For each pair

i, compute the difference: ( di = Method{B,i} - Method_{A,i} ). Method A is typically treated as the reference. [22] - Compute Mean Difference (Bias) and Standard Deviation of Differences:

- Mean Difference (( \bar{d} )): Estimates the systematic bias between methods.

- Standard Deviation of Differences (( s_d )): Quantifies the random variation around this bias.

- Calculate the Limits of Agreement:

- Upper LoA: ( \bar{d} + 1.96 \times sd )

- Lower LoA: ( \bar{d} - 1.96 \times sd )

- Visualization with a Bland-Altman Plot: Create a scatter plot with the mean of the two methods ( \frac{(MethodA + MethodB)}{2} ) on the x-axis and the difference ( (MethodB - MethodA) ) on the y-axis. Plot ( \bar{d} ) and the Upper and Lower LoA as horizontal lines.

Example from environmental analysis: [23]

- Objective: Assess if a cost-effective GC-QqQ-MS/MS method can replace standard GC-HR/MS for analyzing PCDDs/Fs in soil.

- Data: 90 paired soil samples.

- Statistical Analysis: Bland-Altman analysis and Passing-Bablok regression were performed.

- Result: The concentration range of 98.2 to 1760 pg/g showed good agreement between the two methods at the 95% confidence level, suggesting they may be interchangeable for regulatory monitoring. [23]

Critical Considerations and Limitations

Understanding the limitations of each method is vital for their correct application in chemical research.

- Confidence Intervals describe the uncertainty in an estimate of a population parameter (like the mean) based on a sample. They do not describe the variability of individual data points, for which the standard deviation is used. [20]

- Limits of Agreement have strong, often violated, assumptions. If the two methods have different precisions, or if the bias between them is not constant (e.g., it changes proportionally with the magnitude of measurement), the standard LoA method can be misleading. [22] If these assumptions are violated, alternative statistical methods that require repeated measurements from at least one method must be used. [22]

- Aleatoric Uncertainty defines the irreducible error inherent in a system. In chemistry, this is often set by experimental noise and inter-laboratory variability. For example, solubility (( \log S )) measurements are considered to have an aleatoric limit of 0.5-1.0 log units, meaning no predictive model can be reliably more accurate than this threshold using existing data. [24]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and statistical tools required for conducting the experiments and analyses described in this guide.

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard Material | A substance with a known, highly certain property value (e.g., purity, concentration); serves as the benchmark for method comparison studies. [25] |

| Internal Standard (for MS methods) | A compound added to samples in mass spectrometry to correct for variability during sample preparation and instrument analysis, improving precision. [23] |

| GC-HR/MS (Gas Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) | The reference method in our example; represents the "gold standard" against which the performance of a new method (GC-QqQ-MS/MS) is compared. [23] |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python with SciPy) | Used to perform complex calculations, generate Bland-Altman plots, run regression analyses, and compute confidence intervals accurately. [20] |

| Curated Chemical Database (e.g., BigSolDB) | A high-quality, structured dataset used to train and validate predictive models and understand the inherent noise (aleatoric uncertainty) in chemical measurements. [24] |

| Everolimus-d4 | Everolimus-d4, MF:C53H83NO14, MW:962.2 g/mol |

| A-1331852 | A-1331852, MF:C38H38N6O3S, MW:658.8 g/mol |

Modern Methodologies: Implementing AI and HTE for Enhanced Prediction

Leveraging High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Robust Data Generation

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has undergone an outstanding evolution in the past two decades, establishing itself as a transformative methodology that accelerates reaction discovery and optimization in organic chemistry and drug development [26]. This approach fundamentally shifts the paradigm from traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) experimentation to the parallelized investigation of chemical reactions through miniaturization and automation [27] [26]. Within the critical context of accuracy and precision evaluation in organic chemistry methods research, HTE provides a robust framework for generating reliable, reproducible, and statistically significant datasets. By enabling researchers to explore a vastly expanded experimental parameter space while maintaining stringent control over reaction conditions, HTE delivers unprecedented insights into reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and optimization pathways that were previously inaccessible through conventional methods [26] [28]. The pharmaceutical industry has been an early adopter of these methodologies, recognizing HTE's potential to derisk the drug development process by enabling the testing of a maximal number of relevant molecules under carefully controlled conditions [26]. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of HTE with machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence promises to further enhance its predictive capabilities and experimental efficiency [27] [28].

Fundamental HTE Methodologies and Workflows

Core Experimental Design Principles

The implementation of HTE follows meticulously designed workflows that ensure comprehensive exploration of chemical reaction parameters. A standard HTE campaign typically involves screening reactions in a plate-based format, such as 96-well or 1536-well plates, with reaction volumes ranging from microliters to milliliters [26] [29]. This miniaturization enables significant reductions in material requirements, time investment, and chemical waste while facilitating the parallel execution of dozens to hundreds of experiments [26]. Experimental designs are carefully constructed to investigate multiple variables simultaneously, including catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, temperatures, and concentrations, providing a multidimensional understanding of reaction optimization landscapes [29].

A key innovation in practical HTE implementation is the development of "end-user plates" – pre-prepared plates containing reagents, catalysts, or ligands stored under controlled conditions [29]. These standardized plates dramatically reduce the activation barrier for HTE adoption by allowing chemists to simply add their specific substrates and initiate experiments without tedious weighing and preparation steps. For instance, Domainex has developed end-user plates for common transformations like Suzuki-Miyaura cross-couplings, featuring six different palladium pre-catalysts with combinations of bases and solvents in a 24-well format [29]. This approach balances experimental diversity with practical accessibility, enabling non-HTE specialists to leverage high-throughput methodologies as a "first-port-of-call" for reaction optimization [29].

Analytical and Data Processing Methodologies

The generation of robust data through HTE relies heavily on advanced analytical technologies and standardized processing protocols. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) has emerged as the analytical cornerstone of HTE workflows, enabling rapid characterization of reaction outcomes with cycle times as short as two minutes per sample [29]. The integration of internal standards, such as N,N-dibenzylaniline or biphenyl, allows for precise quantification and normalization of analytical results across large experimental sets, mitigating confounding effects from instrumental variability [26] [29].

Data analysis is increasingly supported by computational tools that automate processing and visualization. Open-source software like PyParse, a Python tool specifically designed for analyzing UPLC-MS data from high-throughput experiments, enables scientist-guided automated data analysis with standardized output formats [29]. This facilitates the transformation of raw analytical data into actionable insights through intuitive visualizations like heatmaps, which clearly identify optimal reaction conditions based on metrics such as "corrP/STD" (corrected product to internal standard ratio) [29]. The systematic storage of all experimental parameters and outcomes in structured formats additionally creates valuable datasets for training machine learning models to predict optimal reaction conditions [29] [28].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions in HTE Workflows

| Reagent/Resource | Function in HTE | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Buchwald Generation 3 Pre-catalysts [29] | Single-component Pd source and ligand system for cross-coupling reactions | Suzuki-Miyaura, Buchwald-Hartwig aminations |

| Specialized Ligands (monodentate alkylphosphines, bi-aryl phosphines, ferrocene-derived bis-phosphines) [29] | Tunable reactivity and selectivity for metal-catalyzed transformations | Cross-couplings, C-H functionalizations |

| End-User Plates [29] | Pre-prepared catalyst plates stored under inert conditions | Rapid setup of common reaction types without repeated weighing |

| UPLC-MS with Internal Standards [26] [29] | High-throughput analysis and quantification of reaction outcomes | Parallel reaction monitoring and yield determination |

| Diverse Solvent/Base Systems [29] | Exploration of reaction medium effects on yield and selectivity | 4:1 organic solvent/water mixtures (t-AmOH, 1,4-dioxane, THF, toluene) |

Figure 1: Standard HTE Workflow for Reaction Optimization

Quantitative Evaluation of HTE Performance

Comparative Analysis of HTE vs. Traditional Optimization

The advantages of HTE over traditional OVAT approaches become quantitatively evident when examining key performance metrics across multiple optimization criteria. A comprehensive evaluation conducted by chemists from academia and pharmaceutical industries assessed both methodologies across eight critical aspects, revealing HTE's superior capabilities in generating robust, reproducible data [26].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of HTE vs. Traditional OVAT Optimization

| Evaluation Metric | HTE Approach | Traditional OVAT Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy [26] | High (precise variable control, minimized bias) | Moderate (susceptible to human error) |

| Reproducibility [26] | High (systematic protocols, traceability) | Variable (operator-dependent) |

| Parameter Exploration | Multidimensional screening | Limited sequential screening |

| Material Efficiency [29] | Micromole to nanomole scale | Gram to milligram scale |

| Time Investment | Concentrated (parallel processing) | Extended (sequential experiments) |

| Data Richness | Comprehensive dataset | Limited data points |

| Success Prediction | Enabled (ML training data) | Intuition-based |

| Negative Result Value | Documented and utilized | Often unreported |

The accuracy advantage of HTE stems from precise control of variables through parallelized systems and robotics, where parameters such as temperature, catalyst loading, and solvent composition remain consistent across experiments, significantly reducing human error [26]. This controlled environment, combined with real-time monitoring using integrated analytical tools, provides more accurate measurements of both reaction kinetics and product distributions [26]. The reproducibility of HTE further enhances data robustness by minimizing operator-induced variations and enabling consistent experimental setups across multiple runs, a critical factor for translating laboratory results to industrial processes [26].

Case Study: HTE in Flortaucipir Synthesis Optimization

The application of HTE to optimize a key step in the synthesis of Flortaucipir, an FDA-approved imaging agent for Alzheimer's diagnosis, demonstrates the quantitative benefits of this approach in a practical context [26]. Through a systematically designed HTE campaign conducted in a 96-well plate format, researchers achieved comprehensive optimization of critical reaction parameters that would have been prohibitively time-consuming using traditional methods.

The Flortaucipir case study exemplifies how HTE enables "failing fast" – quickly identifying non-viable synthetic routes before substantial resources are invested [29]. This approach contrasts sharply with traditional optimization, where the limited exploration of parameter space often leads to suboptimal conditions that may fail during scale-up or when applied to analogous compounds [26]. The reliable datasets generated through HTE not only facilitate immediate reaction optimization but also contribute to broader scientific knowledge by documenting both successful and failed experiments, creating valuable information for predictive model development [26] [28].

HTE Applications in Drug Development and Validation

Enhancing Preclinical Analytical Development

The principles of HTE extend beyond synthetic chemistry to enhance accuracy and precision in preclinical drug development, particularly through advanced analytical techniques. Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) have become indispensable tools in preclinical research, offering superior sensitivity, selectivity, and throughput for compound characterization and bioanalysis [30].

These analytical HTE approaches enable rapid screening of chemical libraries to identify lead compounds, precise quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological matrices, and comprehensive evaluation of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties [30]. The implementation of high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) further advances these capabilities by providing exceptional sensitivity and accuracy for analyzing complex matrices, effectively mitigating signal suppression issues and enabling differentiation and quantification of low-abundance analytes even in the presence of endogenous compounds [31]. This enhanced analytical precision is particularly valuable for understanding complex biological processes such as drug transporter inhibition, where precise time profiles are crucial for accurate toxicological assessments [31].

Meeting Regulatory Standards Through Robust Data Generation

The robust data generation capabilities of HTE directly support regulatory compliance in drug development by ensuring data meets the stringent accuracy and precision requirements of agencies like the FDA and EMA. Regulatory expectations mandate complete analytical method validation according to ICH guidelines, including specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness demonstrations [30]. HTE methodologies facilitate this compliance through standardized protocols, comprehensive documentation, and built-in quality control measures.

The regulatory shift from primarily valuing sensitivity to emphasizing accuracy represents a transformative change in toxicological assessments, further elevating the importance of HTE approaches [31]. This focus on precise target analysis is particularly critical as the field transitions from traditional small-molecule drugs to complex biotherapeutics, especially for rare diseases [31]. HTE supports this transition through approaches grounded in Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), employing advanced analytical techniques to mitigate matrix effects and provide reliable preclinical toxicology data that withstands regulatory scrutiny [31] [30].

Figure 2: HTE Role in Regulatory Approval Pathway

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The integration of HTE with machine learning and artificial intelligence represents the most promising future direction for further enhancing accuracy and precision in organic chemistry research [27] [28]. As HTE platforms generate increasingly large and standardized experimental datasets, these become valuable training resources for predictive algorithms that can potentially guide experimental design before laboratory work begins [29] [28]. The long-term goal is developing reaction models that can predict optimal conditions, ultimately reducing the experimental burden while improving outcomes [29].

Current research focuses on transforming HTE into a "fully integrated, flexible, and democratized platform that drives innovation in organic synthesis" [27]. This includes developing customized workflows, diverse analysis methods, and improved data management practices for greater accessibility and shareability [27]. As these technologies become more widespread and user-friendly, HTE is poised to transition from a specialized tool in pharmaceutical industry to a standard methodology across academic and industrial research settings, fundamentally changing how chemical research is conducted and accelerating the discovery and development of novel molecular entities [26] [28].

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling of Free Energy and Reaction Kinetics

The accurate prediction of free energy and reaction kinetics is a cornerstone of modern organic chemistry and drug development, directly impacting the efficiency of molecular design and synthetic planning. Traditional computational methods, particularly Density Functional Theory (DFT), have long served as the workhorse for simulating reactions but often struggle with a critical trade-off between computational cost and chemical accuracy, especially for complex systems in solution [32] [33]. The emergence of Machine Learning (ML) offers a paradigm shift, enabling the development of models that can achieve high precision at a fraction of the computational expense. This guide provides an objective comparison of current methodologies, categorizing them into traditional DFT, pure ML potentials, and hybrid approaches, and evaluates their performance against experimental and benchmark data within a rigorous accuracy and precision framework.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Methodologies

This section compares the core methodologies for predicting free energy and reaction kinetics, summarizing their fundamental principles, key performance metrics, and ideal use cases.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodologies for Free Energy and Reaction Kinetics Prediction

| Methodology | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Reported Performance on Key Metrics | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computes electronic structure via exchange-correlation functionals [34]. | Gaussian, ORCA, Schrödinger [35] [34] | Barrier Height MAE: ~2-4 kcal/mol [33]Cost: High (hours/days for TS optimizations) [32] | Reaction mechanism elucidation; single-point energy calculations on pre-optimized structures [32]. |

| Universal ML Interatomic Potentials (UIPs) | Purely data-driven potential energy surface (PES) prediction [32]. | ANI-1ccx [32] | Barrier Height MAE: Subpar vs. coupled cluster [32]Cost: Very Low (orders of magnitude faster than DFT) [32] | High-speed screening of molecular properties; systems within well-covered chemical space [32]. |

| Δ-Learning Hybrid Methods | ML corrects a fast baseline QM method (e.g., semi-empirical) to a high-level target [32]. | AIQM1, AIQM2 [32] | Barrier Height MAE: AIQM2 approaches gold-standard coupled cluster accuracy [32]Cost: Low (near semi-empirical speed) [32] | Large-scale reaction dynamics; transition state search; robust organic reaction simulations [32]. |

| Mechanistic/ML Hybrid Models | Uses DFT-calculated TS features as inputs for ML models trained on experimental kinetics [33]. | Custom workflows (e.g., predict-SNAr) [33] | Barrier Height MAE: 0.77 kcal/mol for SNAr [33]Cost: Moderate (requires DFT-level TS calculation) | Accurate prediction for specific reaction classes with limited experimental kinetic data [33]. |

Performance Benchmarking Data

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of different methods based on benchmark studies, highlighting their accuracy in predicting key thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarking of Computational Methods

| Method | Reaction Energy MAE (kcal/mol) | Barrier Height MAE (kcal/mol) | Reference Level | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIQM2 | At least at DFT level, often approaches coupled cluster [32] | At least at DFT level, often approaches coupled cluster [32] | Coupled Cluster (Gold Standard) [32] | Enabled thousands of high-quality reaction trajectories overnight; revised DFT-based product distribution for a bifurcating pericyclic reaction [32]. |

| Hybrid ML-DFT (for SNAr) | Information Missing | 0.77 (on external test set) [33] | Experimental Kinetic Data [33] | Achieved 86% top-1 accuracy in regioselectivity prediction on patent data without explicit training for this task [33]. |

| Traditional DFT | Varies significantly with functional | Struggles with absolute barriers for ionic reactions in solution [33] | Coupled Cluster / Experiment [32] [33] | Performance highly dependent on functional and solvation model; can be "not even wrong" for some solution-phase ionic reactions [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

To ensure the reliability of predictive models, rigorous validation against experimental or high-level computational benchmarks is essential. The following protocols detail standard procedures for training and evaluating models for reaction kinetics prediction.

Protocol for Developing a Hybrid ML-DFT Model

This protocol, adapted from a study on nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr), outlines the steps for creating a hybrid model that leverages DFT-derived descriptors to predict experimental activation barriers [33].

- Data Curation: Collect high-quality experimental kinetic data (e.g., rate constants) for the reaction class of interest. For the SNAr study, 449 rate constants were converted to activation energies (ΔG‡) via the Eyring equation [33].

- Reaction Featurization:

- Input: Reaction SMILES strings [33].

- Mechanistic Calculation: Use an automated workflow (e.g., predict-SNAr) to locate reactants, products, and the rate-determining transition state (TS) using a combination of semi-empirical and DFT methods [33].

- Descriptor Calculation: Extract quantum-mechanical features from the optimized structures. Key descriptors include [33]:

- Electrostatic Potentials: Surface average electrostatic potential (VÌ„s) of nucleophilic and electrophilic atoms as "hard" descriptors of nucleophilicity and electrophilicity.

- Orbital Energies: HOMO and LUMO energies of the nucleophile and electrophile as "soft" descriptors.

- Bonding & Sterics: Bond orders and partial charges at the reaction center.

- Solvation Features: Solvent parameters and calculated solvation energies.

- Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm: Train a model, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), using the calculated features as inputs and the experimental activation energies as targets [33].

- Validation: Perform a train-test split (e.g, 80-20) to evaluate the model on held-out data. GPR provides error bars for each prediction, which is valuable for risk assessment [33].

- Performance Evaluation: Report the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on the test set to quantify accuracy. The SNAr model achieved an MAE of 0.77 kcal/mol, meeting the threshold for "chemical accuracy" [33].

Diagram 1: Hybrid ML-DFT model training and validation workflow.

Protocol for Large-Scale Reaction Simulation with AIQM2

AIQM2 is a foundational model that can be used "out-of-the-box" for diverse reaction simulations without further retraining. This protocol describes its application to a large-scale reaction dynamics study [32].

- System Setup:

- Define the initial geometry of the reactant(s).

- Specify the level of theory as AIQM2 within the simulation software (e.g., MLatom).

- Transition State Optimization:

- Use AIQM2 to locate and optimize transition state structures. AIQM2 has demonstrated high accuracy in TS optimizations and barrier heights, at least at the level of DFT and often approaching coupled-cluster accuracy [32].

- Reaction Dynamics:

- Initialize molecular dynamics trajectories from the transition state region (post-TS MD).

- Propagate thousands of trajectories using AIQM2 to compute the forces. Its speed, which is orders of magnitude faster than common DFT, makes this computationally feasible [32].

- Analysis:

- Analyze the trajectories to determine product distribution (branching ratios).

- Calculate reaction rates and compare with experimental or benchmark data.

Diagram 2: AIQM2 reaction simulation workflow for large-scale dynamics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details key software, datasets, and computational tools that function as essential "reagents" in the virtual laboratory for AI-driven reaction prediction.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for AI-Driven Reaction Prediction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Free Energy/Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIQM2 | AI-Enhanced QM Method | Provides coupled-cluster level accuracy at semi-empirical cost for energy and force calculations [32]. | Core engine for high-fidelity reaction dynamics and barrier height prediction [32]. |

| MLatom | Software Platform | An open-source framework for running AIQM2 and other ML-driven atomistic simulations [32]. | Enables practical application of AIQM2 for reaction modeling [32]. |

| GFN2-xTB | Semi-Empirical QM Method | Fast, robust geometry optimization and baseline calculation for large systems [32] [34]. | Serves as the baseline method in the AIQM2 Δ-learning scheme [32]. |

| Gaussian/ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Code | Performs traditional DFT and post-Hartree-Fock calculations for reference data and featurization [35] [34]. | Generates training features for hybrid models and provides benchmark results [33]. |

| Experimental Kinetics Dataset | Curated Data | A collection of reaction rate constants/barriers for a specific reaction class (e.g., SNAr) [33]. | Essential ground truth for training and validating predictive regression models [33]. |

| Reactant & Transition State Structures | Molecular Geometry Data | 3D atomic coordinates of key points on the reaction pathway. | Fundamental inputs for calculating quantum mechanical descriptors and training MLIPs [33]. |

| AICAR phosphate | AICAR phosphate, MF:C9H17N4O9P, MW:356.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PE859 | PE859, MF:C28H24N4O2, MW:448.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of AI and machine learning with computational chemistry is fundamentally advancing the predictive modeling of free energy and reaction kinetics. While traditional DFT remains a valuable tool, hybrid approaches like AIQM2 and mechanistic ML models demonstrate a superior balance of speed and accuracy, often achieving near-chemical accuracy critical for guiding experimental research. The choice of methodology depends on the specific application: Δ-learning methods like AIQM2 are ideal for universal, robust reaction exploration, while targeted hybrid models excel in delivering extreme precision for specific reaction classes with limited data. The continued development and validation of these tools, supported by standardized benchmarking and experimental protocols, promise to further narrow the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality in organic chemistry and drug development.

The process of ligand screening is pivotal in developing efficient transition metal catalysis, a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry and pharmaceutical development. Conventionally, identifying an optimal ligand from vast molecular libraries has relied on experimental trial-and-error cycles, requiring substantial time and laboratory resources [36] [37]. This case study examines the emerging methodology of Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening (VLAS) as a computational alternative, evaluating its performance against traditional approaches within a critical framework of accuracy and precision essential to organic chemistry methods research.

The VLAS strategy represents a paradigm shift toward in silico ligand screening based on transition state theory, potentially streamlining the catalyst design process and enabling discoveries beyond the scope of chemical intuition [37]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities and validation metrics of this approach is crucial for its informed application in accelerating discovery workflows while maintaining rigorous standards of reliability.

VLAS Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Core Principles and Virtual Ligand Design

The VLAS methodology centers on using computationally efficient approximations to simulate ligand effects without modeling each atom explicitly. Researchers have developed a virtual ligand, denoted as PCl*₃, which parameterizes both electronic and steric effects of monodentate phosphorus(III) ligands using only two key metrics [36] [38]. This simplified description enables rapid evaluation across a broad spectrum of potential ligand properties, creating a comprehensive "contour map" that visualizes optimal combinations of steric and electronic characteristics for specific catalytic reactions [37].

The fundamental innovation lies in replacing resource-intensive atomistic calculations with a parameter-based approach that captures essential chemical features while dramatically reducing computational overhead. This virtual parameterization was rigorously verified against values calculated for corresponding real ligands, establishing a foundation for predictive accuracy [37].

Experimental Workflow and Implementation

The experimental protocol for VLAS follows a systematic workflow that transforms virtual screening results into practical catalyst designs. The process begins with virtual ligand parameterization, where researchers develop approximations describing steric and electronic effects with single parameters [37]. This is followed by reaction pathway evaluation across multiple virtual ligand cases with differing parameter combinations [38]. Computational results are then synthesized into a steric-electronic contour map that identifies optimal regions for ligand performance [37]. Finally, researchers design computer models of real ligands based on parameters extracted from the contour map for computational validation [37].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The VLAS methodology relies on specialized computational tools and theoretical frameworks that constitute the essential "research reagents" for in silico catalyst optimization.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for VLAS Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Role in VLAS Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Ligand PCl*₃ | Computational Model | Parameterizes steric/electronic effects | Core screening entity that replaces physical ligands |

| Quantum Chemical Calculations | Computational Method | Calculates reaction energy profiles | Assesses how ligand effects perturb reaction pathways |

| Steric-Electronic Contour Map | Analytical Tool | Visualizes optimal ligand parameter spaces | Identifies promising ligand characteristics for target reactions |

| Transition State Theory | Theoretical Framework | Describes reaction rates and pathways | Foundation for predicting catalytic activity and selectivity |

| Artificial Force Induced Reaction (AFIR) | Computational Method | Predicts reaction pathways | Combined with VLAS for comprehensive reaction discovery |

Accuracy and Precision Assessment Framework

Validation Metrics for Computational Methods

In analytical chemistry, accuracy measures the closeness of experimental values to true values, while precision measures the reproducibility of individual measurements [1] [39]. For computational methods like VLAS, establishing accuracy requires demonstrating that virtual screening predictions correlate strongly with experimental outcomes for known systems. Precision in VLAS would manifest as consistent predictions across multiple computational trials and similar chemical spaces.

The spike recovery method commonly used in natural product studies provides a useful analogy for validation, where a known amount of constituent is added to a matrix and recovery percentage determines accuracy estimates [1]. For purely computational methods, similar approaches can be implemented using benchmark systems with established experimental data.

Regulatory perspectives emphasize that analytical methods "must be accurate, precise, and reproducible" to bear the weight of scientific and regulatory scrutiny [1]. The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) further defines fitness for purpose as the "degree to which data produced by a measurement process enables a user to make technically and administratively correct decisions for a stated purpose" [1].

VLAS Performance Evaluation

In the test case of rhodium-catalyzed hydroformylation of terminal olefins, the VLAS method demonstrated promising accuracy by designing phosphorus(III) ligands with computationally predicted high linear or branched selectivities that matched well with values computed for models of real ligands [37] [38]. This successful prediction of selectivity outcomes for a selectivity-determining step indicates the method's potential accuracy for optimizing stereochemical outcomes in catalysis.

The precision of VLAS stems from its systematic parameterization approach, which reduces random variability compared to traditional experimental screening where numerous factors can introduce uncertainty. However, the method's fundamental precision depends on the quality of the parameterization and the transferability of the virtual ligand model across different catalytic systems.

Comparative Performance Analysis

VLAS vs. Traditional Experimental Screening

Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening offers distinct advantages and limitations when compared to conventional ligand screening approaches, with significant implications for research efficiency and resource allocation.

Table 2: Performance Comparison: VLAS vs. Traditional Screening Methods

| Performance Metric | VLAS Approach | Traditional Experimental Screening | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | High throughput of virtual parameter space | Limited by synthetic and testing capacity | VLAS enables broader exploration of chemical space |

| Resource Requirements | Primarily computational resources | Significant laboratory materials and personnel | VLAS reduces physical resource burden |

| Time Efficiency | Rapid parameter space mapping (days) | Extended trial-and-error cycles (weeks/months) | VLAS dramatically accelerates initial screening |

| Accuracy | Promising for selectivity prediction | Direct experimental measurement | Traditional methods provide empirical validation |

| Precision | Systematic parameterization reduces variability | Subject to experimental variability | VLAS offers more consistent screening parameters |

| Exploratory Capability | Can identify unconventional designs beyond intuition | Limited to existing ligand libraries or synthetic feasibility | VLAS enables discovery of novel ligand architectures |

VLAS vs. Other Computational Screening Methods

The computational catalysis landscape includes various in silico approaches, each with distinct methodological frameworks and performance characteristics.

Table 3: VLAS Comparison with Alternative Computational Methods

| Methodology | Computational Efficiency | Accuracy Domain | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening (VLAS) | High efficiency through parameterization | Strong for selectivity prediction in transition metal catalysis | Limited to parameterized ligand classes |

| Full Quantum Chemical Screening | Low efficiency due to computational intensity | High accuracy for well-defined systems | Limited to small ligand sets |

| QSAR/QSPR Models | Moderate to high efficiency | Variable accuracy depending on training data | Requires extensive experimental data for training |

| Molecular Dynamics Approaches | Low to moderate efficiency | Strong for thermodynamic properties | Limited for reaction kinetics prediction |

Experimental Data and Case Study Results

Hydroformylation Catalysis Case Study

In the demonstration case studying the selectivity-determining step of rhodium-catalyzed hydroformylation of terminal olefins, the VLAS method enabled design of phosphorus(III) ligands with potentially high linear or branched selectivities [36] [38]. The contour maps generated from virtual ligand screening visually identified trends in what ligand types would produce highly selective reactions, successfully predicting selectivity values that matched well with those computed for real ligand models [37].

This case study exemplifies how the VLAS method provides guiding principles for rational ligand design rather than merely selecting from existing libraries. The research confirmed that "the selectivity values predicted via the VLA screening method matched well with the values computed for the models of real ligands, showing the viability of the VLA screening method to provide guidance that aids in rational ligand design" [37].

Integration with Broader Computational Workflows

The VLAS methodology shows particular promise when integrated with complementary computational approaches. Corresponding author Satoshi Maeda notes that "by combining this method with our reaction prediction technology using the Artificial Force Induced Reaction method, a new computer-driven discovery scheme of transition metal catalysis can be realized" [37]. This integration represents a movement toward comprehensive in silico reaction design and optimization platforms.

Beyond the chemical catalysis domain, similar VLA (Vision-Language-Action) concepts are demonstrating value in robotics and embodied AI systems, where unifying action models with world models has shown mutual performance enhancement [40]. This parallel development in different fields suggests the broader potential of virtual-assisted screening approaches across scientific domains.

Virtual Ligand-Assisted Screening represents a significant advancement in computational catalyst design, offering a structured framework for navigating complex ligand parameter spaces with improved efficiency over traditional screening methods. While the approach shows promising accuracy in predicting selectivity outcomes, as demonstrated in hydroformylation catalysis, its broader validation across diverse reaction classes remains an important area for continued research.

For drug development professionals and research scientists, VLAS offers a powerful tool for accelerating early-stage catalyst optimization while reducing resource expenditures. The method's strength lies in its ability to provide rational design principles and identify promising regions of chemical space prior to resource-intensive experimental work. As with all computational methods, appropriate validation and understanding of limitations remain essential for effective implementation.

The continuing integration of VLAS with complementary computational approaches, including reaction prediction technologies and machine learning platforms, promises to further enhance its accuracy and scope, potentially establishing new paradigms for computer-driven discovery in transition metal catalysis and beyond.

Community-Engaged Test Sets and Open Competitions for Democratizing ML in Chemistry

The integration of machine learning (ML) into chemistry promises to revolutionize the discovery of new molecules and materials. However, a significant bottleneck has been the development of ML models that are not only computationally efficient but also chemically accurate and broadly applicable. Community-engaged test sets and open competitions are emerging as powerful paradigms to address these challenges, fostering collaboration and accelerating innovation. These initiatives democratize access to cutting-edge research by crowdsourcing solutions from a global community of data scientists, thereby generating diverse approaches to complex chemical problems. This guide objectively compares key platforms and datasets shaping this landscape, evaluating their performance, experimental protocols, and utility for researchers in organic chemistry and drug development. The analysis is framed within the critical context of accuracy and precision evaluation, essential for developing reliable ML tools that can predict chemical properties and reactions with the rigor required for scientific and industrial application [41].

Comparative Analysis of Open Platforms and Datasets

The ecosystem for open, community-driven ML in chemistry has been recently enriched by large-scale public datasets and targeted competitive challenges. The table below compares two prominent examples: the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset and the University of Illinois Kaggle Competition.

Table 1: Comparison of Community-Engaged Chemistry ML Initiatives

| Feature | Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) Dataset [42] [43] | Illinois Kaggle Competition on Molecular Photostability [41] |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Initiative | Large-scale, open-access dataset for general ML model training. | Focused, time-bound prediction competition. |

| Primary Goal | Provide foundational data to train ML models for quantum-accurate molecular simulations. | Crowdsource the best ML models to predict the photostability of specific small molecules. |