Advanced Electrophoresis Techniques for Biomolecule Separation: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

This comprehensive article explores the fundamental principles, diverse methodologies, practical applications, and emerging trends in electrophoresis for biomolecule separation.

Advanced Electrophoresis Techniques for Biomolecule Separation: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This comprehensive article explores the fundamental principles, diverse methodologies, practical applications, and emerging trends in electrophoresis for biomolecule separation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts of slab gel, capillary, and microchip techniques; detailed protocols for nucleic acid and protein analysis; systematic troubleshooting for common experimental artifacts; and comparative validation with innovative alternatives. The content synthesizes current innovations, including automation, AI integration, and microfluidics, providing both theoretical knowledge and practical guidance to enhance experimental efficiency and accuracy in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Core Principles and Evolution of Electrophoresis Technology

The field of biomolecule separation was fundamentally transformed by the pioneering work of Arne Tiselius, who in 1937 demonstrated that charged particles could be separated using an electrical field [1] [2]. His development of moving-boundary electrophoresis represented the first systematic method for separating complex biological mixtures based on charge differences, earning him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1948 [3]. This breakthrough initiated a technological evolution that has progressed through increasingly sophisticated separation methodologies, culminating in today's integrated microfluidic systems [1] [4].

The journey from Tiselius' original apparatus to modern microfluidic devices reflects a continuous pursuit of higher resolution, faster analysis, and greater automation. Where early electrophoresis used liquid media susceptible to diffusion and convection, the subsequent introduction of solid supporting matrices like filter paper, agarose, and polyacrylamide gel dramatically improved resolution by stabilizing separated components into discrete zones [1] [2]. This evolution has positioned electrophoresis as an indispensable tool in molecular biology, proteomics, and clinical diagnostics, enabling everything from DNA sequencing to protein fingerprinting [1].

Historical Milestones in Electrophoresis Development

The Tiselius Era and Moving-Boundary Electrophoresis

Arne Tiselius's groundbreaking work built upon earlier observations of electrokinetic phenomena dating back to 1807 by Strakhov and Reuß, who noted that clay particles in water would migrate under a constant electric field [1]. Tiselius's key innovation was the refinement of these principles into a practical analytical tool. His apparatus, developed with support from the Rockefeller Foundation, employed optical detection of moving boundaries using schlieren techniques to visualize separated components in solution [1].

The Tiselius method suffered from significant limitations—it could not achieve complete separation of similar compounds and provided limited resolution due to gravitational effects and diffusion in liquid media [1] [2]. Despite these constraints, it successfully demonstrated that serum proteins could be separated into different fractions, laying the foundation for subsequent advances in protein analysis [3]. Tiselius himself recognized these limitations and later coined the term "zone electrophoresis" in 1950 to describe emerging methods that used solid or gel matrices to separate compounds into discrete bands [1].

The Zone Electrophoresis Revolution

The 1940s and 1950s witnessed a paradigm shift from moving-boundary to zone electrophoresis techniques, which addressed fundamental limitations of the Tiselius apparatus. The introduction of solid supporting matrices including filter paper, cellulose acetate, and various gels enabled complete separation of components into stable, discrete zones [1] [2]. This period marked the transition of electrophoresis from a specialized analytical technique to a broadly accessible laboratory tool.

A critical advancement came in 1955 when Oliver Smithies introduced starch gel electrophoresis, which provided significantly improved resolution for protein separation [1]. This was followed by the development of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), which offered precise control over pore size through adjustable cross-linking densities [1] [2]. The introduction of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins and impart a uniform charge-to-mass ratio further revolutionized protein analysis, enabling separation based primarily on molecular weight [2] [5].

Capillary and Microfluidic Electrophoresis

The 1980s and 1990s saw the emergence of capillary electrophoresis (CE), which addressed several limitations of slab gel methods [4] [6]. By performing separations within narrow-bore capillaries, CE leveraged efficient heat dissipation to enable application of very high voltages (typically 10-30 kV), resulting in faster separations with superior resolution [2] [4]. The technique also facilitated direct on-line detection through various detection methods including UV-Vis absorbance and laser-induced fluorescence [4].

The most recent evolutionary stage has been the integration of electrophoresis principles with microfluidic technology, creating lab-on-a-chip devices that miniaturize and automate complex analytical workflows [7] [4]. First proposed in the early 1990s, these systems manipulate small fluid volumes (microliter to picoliter range) within channels less than 1 millimeter wide [7] [6]. The convergence of electrophoresis with microfluidics has enabled unprecedented levels of automation, parallelization, and integration of multiple processing steps from sample preparation to final detection [7] [8].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Electrophoresis Techniques

| Time Period | Dominant Technology | Key Innovations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930s-1940s | Moving-boundary electrophoresis | Tiselius apparatus, schlieren optics | Serum protein separation |

| 1950s-1960s | Zone electrophoresis | Starch gels, polyacrylamide gels, cellulose acetate | Protein fractionation, clinical diagnostics |

| 1970s-1980s | Advanced gel electrophoresis | SDS-PAGE, isoelectric focusing, 2D electrophoresis | Molecular biology, proteomics, DNA separation |

| 1990s-2000s | Capillary electrophoresis | High voltage separation, on-column detection | Pharmaceutical analysis, genetic analysis |

| 2000s-Present | Microfluidic electrophoresis | Lab-on-a-chip, integrated systems, digital microfluidics | Point-of-care diagnostics, high-throughput screening, single-cell analysis |

Fundamental Principles and Technical Considerations

Core Principles of Electrophoresis

All electrophoresis techniques share the fundamental principle that charged particles will migrate in response to an applied electric field [2] [5]. The direction and velocity of migration depend on the net charge, size, and shape of the molecule, as well as the properties of the separation medium [4]. In gel electrophoresis, the matrix acts as a molecular sieve, retarding larger molecules while allowing smaller ones to migrate more rapidly [9] [5].

Several critical factors influence electrophoretic separation efficiency. The electrophoretic mobility (μ) of a molecule is directly proportional to its net charge and inversely proportional to its size and the viscosity of the medium [2] [5]. Buffer conditions including pH and ionic strength significantly impact separation by altering the charge state of molecules and affecting current flow and heating [4] [5]. Optimal ionic strength is essential, as high ionic strength increases current and heat generation, while low ionic strength reduces resolution due to diminished current flow [5].

Key Technical Components

All electrophoresis systems share common core components, though their implementation varies across different platforms. These include:

- Power supply: Provides the electrical field necessary for particle migration, with voltage requirements ranging from 100-150 V for conventional slab gels to thousands of volts for capillary systems [9] [5].

- Buffer system: Carries current and maintains stable pH conditions throughout separation [2] [5]. Common buffers include TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) and TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) for nucleic acids, and various Tris-based buffers for proteins [9].

- Support medium: Provides the matrix for separation, with choice of medium depending on application requirements [2] [5].

- Detection system: Visualizes and quantifies separated components, ranging from simple staining and UV transillumination to sophisticated in-line detectors for capillary systems [9] [5].

Table 2: Common Support Media in Electrophoresis

| Medium Type | Typical Applications | Resolution | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agarose gel | DNA/RNA separation, large proteins | Moderate | Easy to use, non-toxic, pore size 0.1-0.5% |

| Polyacrylamide gel | Proteins, small DNA fragments, sequencing | High | Adjustable pore size, can be toxic |

| Cellulose acetate | Clinical protein analysis, hemoglobin variants | Good | Rapid separation, minimal sample interaction |

| Capillary | Various analytes with UV/fluorescence detection | Very High | Fast, automated, requires specialized instrumentation |

| Microfluidic chip | Diverse applications with integrated processing | High to Very High | Miniaturized, automated, low sample consumption |

Modern Electrophoresis Techniques and Applications

Slab Gel Electrophoresis Methods

Despite the emergence of more advanced technologies, traditional slab gel electrophoresis remains widely employed in research and clinical laboratories due to its simplicity, low cost, and ability to process multiple samples simultaneously [4]. Key variants include:

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis is the method of choice for separating nucleic acids ranging from 100 base pairs to over 25 kilobases [9]. The pore size of agarose gels is determined by the agarose concentration (typically 0.7%-2%), with lower percentages providing better resolution for larger DNA fragments and higher percentages optimizing separation of smaller fragments [9]. Agarose gels are simple to prepare and are typically run at moderate voltages (1-10 V/cm) for 30 minutes to several hours [9].

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) provides superior resolution for proteins and small nucleic acids [2] [5]. The cross-linked structure of polyacrylamide creates a more uniform molecular sieve with precisely controllable pore sizes determined by the ratio of acrylamide to bis-acrylamide [2]. SDS-PAGE denatures proteins and masks their native charge, enabling separation based primarily on molecular weight [2] [5]. Native PAGE preserves protein structure and biological activity, separating based on both size and charge [2].

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis combines isoelectric focusing (separation based on isoelectric point) with SDS-PAGE (separation based on molecular weight) to achieve extremely high resolution for complex protein mixtures [2] [5]. This technique can resolve thousands of proteins in a single analysis and has been instrumental in proteomics research [5].

Capillary Electrophoresis

Capillary electrophoresis represents a significant advancement over slab gel methods, offering faster analysis, higher resolution, and automated operation [4]. In CE, separation occurs within narrow-bore capillaries (typically 25-100 μm internal diameter) filled with buffer or separation matrix [4]. The high surface-to-volume ratio enables efficient heat dissipation, allowing application of very high electric fields (100-500 V/cm) without excessive heating [4]. This results in rapid separations (often minutes instead of hours) with exceptional resolution [4].

CE systems typically incorporate on-column detection methods such as UV-Vis absorbance, laser-induced fluorescence, or mass spectrometry, enabling real-time monitoring and quantification of separated components [4]. The technique finds extensive application in pharmaceutical analysis, clinical diagnostics, and genetic analysis [4].

Microfluidic Electrophoresis Systems

Microfluidic electrophoresis represents the current state-of-the-art, integrating separation capabilities with other analytical functions on miniaturized chips [7] [4]. These lab-on-a-chip devices typically feature networks of microchannels, chambers, and valves that enable precise manipulation of fluid volumes in the microliter to picoliter range [7]. The microscale dimensions confer several advantages including minimal reagent consumption, rapid analysis times, and portability [7].

Key variants of microfluidic electrophoresis include:

- Continuous-flow microfluidics: Manipulates streams of fluid through permanently open channels for applications such as chemical reactions and separations [7].

- Droplet-based microfluidics: Generates and manipulates discrete picoliter-volume droplets, each serving as an isolated microreactor ideal for digital PCR and single-cell analysis [7] [8].

- Digital microfluidics: Controls individual droplets through electrowetting on an array of electrodes, enabling programmable, pump-free fluid handling [8].

- Paper-based microfluidics: Utilizes capillary action in patterned paper channels for ultra-low-cost diagnostic devices suitable for resource-limited settings [7].

Microfluidic electrophoresis systems have found particularly valuable application in point-of-care diagnostics, where their compact size, rapid analysis, and automation capabilities enable sophisticated testing outside central laboratories [7] [8]. Commercial applications include infectious disease testing, blood glucose monitoring, and COVID-19 detection [7].

Comparative Analysis of Electrophoresis Techniques

The various electrophoresis platforms offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different applications and operational contexts. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for selecting the appropriate method for specific research or diagnostic needs.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Electrophoresis Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Analysis Speed | Throughput | Cost | Ease of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slab Gel Electrophoresis | Moderate to High | Slow (1-4 hours) | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | High | Fast (5-30 minutes) | Low to Moderate | High | High (automated) |

| Microchip Electrophoresis | High to Very High | Very Fast (1-10 minutes) | High | Moderate to High | High |

| Isotachophoresis | Moderate | Moderate (10-30 minutes) | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

Slab gel electrophoresis remains popular for applications requiring visual comparison of multiple samples, educational use, and situations where cost is a primary concern [4]. However, it is relatively labor-intensive, difficult to automate, and provides limited quantitative capabilities compared to more advanced platforms [4].

Capillary electrophoresis offers superior resolution and quantification capabilities, particularly for complex mixtures, and enables full automation of the separation and detection process [4]. Its limitations include higher instrument costs and reduced ability to process multiple samples in parallel compared to slab gels [4].

Microfluidic electrophoresis provides the highest level of integration and automation, enabling consolidation of multiple processing steps onto a single platform [7] [4]. These systems excel in applications requiring minimal sample volume, rapid analysis, and portability [7]. Current limitations include higher development complexity and challenges in scaling up manufacturing [7] [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Standard Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for DNA Separation

This protocol describes the fundamental method for separating DNA fragments using agarose gel electrophoresis, a cornerstone technique in molecular biology laboratories [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Agarose powder: Polysaccharide matrix that forms a porous gel for size-based separation [9].

- TAE or TBE buffer (1x): Carries current and maintains stable pH; Tris-acetate-EDTA or Tris-borate-EDTA [9].

- DNA loading dye: Contains dense agents (e.g., glycerol) to help samples sink into wells and tracking dyes to monitor migration progress [9].

- Ethidium bromide solution (10 mg/mL): Fluorescent nucleic acid stain for DNA visualization under UV light; handle with care as it is a mutagen [9].

- DNA molecular weight ladder: A mixture of DNA fragments of known sizes for calibrating and estimating the size of unknown fragments [9].

Equipment:

- Gel casting tray and well combs

- Gel electrophoresis box and power supply

- Microwave oven or hot plate

- UV transilluminator or gel documentation system

Procedure:

- Prepare Agarose Gel Solution: Weigh the appropriate amount of agarose for the desired gel concentration (e.g., 1.0 g for a 1% gel in 100 mL of 1x TAE buffer). A 1% gel is suitable for separating 0.5-10 kb DNA fragments [9].

- Melt Agarose: Mix agarose powder with 1x TAE buffer in a heat-resistant flask. Microwave in short bursts (30-45 seconds) until the agarose is completely dissolved, swirling gently between bursts to ensure even heating. Exercise caution to avoid boil-overs [9].

- Cool Solution: Allow the melted agarose solution to cool to approximately 50-60°C (comfortable to hold in bare hands) to prevent warping the casting tray [9].

- Add Stain (if desired): For post-staining, the gel can be cast without stain. For integrated staining, add ethidium bromide to a final concentration of 0.2-0.5 μg/mL and mix thoroughly. Wear appropriate PPE [9].

- Cast the Gel: Place the well comb in the casting tray. Pour the cooled agarose solution into the tray, ensuring no bubbles form near the comb. Allow the gel to solidify completely at room temperature for 20-30 minutes [9].

- Set Up Electrophoresis: Once solidified, carefully remove the comb and place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber. Submerge the gel completely with 1x TAE buffer [9].

- Load Samples: Mix DNA samples with 6x loading dye. Carefully load the DNA ladder and samples into the wells [9].

- Run Electrophoresis: Connect the lid, ensuring the correct polarity (DNA migrates toward the positive anode - "Run to Red"). Apply a voltage of 80-150 V. Run until the tracking dye has migrated 75-80% of the gel length [9].

- Visualize DNA: Turn off the power. If the gel was not pre-stained, carefully transfer it to a staining solution containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/mL) for 20-30 minutes, followed by a brief destaining step in water. Visualize the DNA bands using a UV transilluminator [9].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor Resolution of Bands: Run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer period, load less DNA, or adjust the agarose concentration for the fragment sizes being separated [9].

- Smiled Bands: Often caused by uneven heating; ensure the gel is fully submerged in buffer and consider running at a lower voltage [9].

Protocol: Microfluidic Electrophoresis Chip Operation

This protocol outlines the general workflow for performing an electrophoretic separation using a commercial microfluidic chip system, such as those used for protein or nucleic acid analysis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer or LabChip systems).

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Proprietary Gel-Matrix Polymer: Contains a replaceable sieving polymer and fluorescent dye for on-chip separation and detection [7].

- Proprietary DNA/RNA or Protein Marker: Used as an internal size standard for accurate fragment sizing and quantification.

- Ionic Buffer/Sieving Buffer: Provides the conductive medium for electrophoresis within the microchannels.

- Sample Buffer: Contains a proprietary dye and denaturants (if required) to prepare the sample for injection.

Equipment:

- Microfluidic Chip (e.g., DNA, RNA, or Protein chip)

- Chip Priming Station

- Microfluidic Instrumentation (includes chip reader, software, and voltage controllers)

- IKA Vortex Mixer

- Magnetic Spin Vac

- Pipettes and specific tips

Procedure:

- Chip and Reagent Preparation: Remove the gel matrix, dyes, and chips from storage and allow them to warm to room temperature. Vortex the gel matrix and spin down. Label the chip appropriately [7].

- Chip Priming: Pipette the gel matrix into the appropriate well. Position the chip in the priming station and close the lid. Press the plunger and hold for exactly 60 seconds. Release the plunger slowly. Confirm that the plunger has moved back to the start position, indicating the chip has been properly filled [7].

- Load Buffers and Samples: Pipette the ionic buffer/sieving buffer into the designated buffer wells. Pipette the marker into all sample wells and any unused wells. Pipette the prepared samples (mixed with sample buffer) into the designated sample wells. Ensure no bubbles are introduced [7].

- Chip Processing: Place the chip securely into the instrument adapter. Close the lid and start the run via the associated software. The instrument automatically applies voltages for sample injection, separation, and detection via a laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detector [7].

- Data Analysis: After the run is complete (typically 20-40 minutes), the software automatically generates an electrophoretogram for each sample, displays a virtual gel image, and provides sizing and concentration data based on the internal standard [7].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor Sensitivity: Ensure reagents are at room temperature and have not expired. Check that the chip was primed correctly and that no bubbles are blocking the microchannels [7].

- Inaccurate Sizing: Ensure the correct ladder/marker was used and that it was loaded properly. Check for degraded samples [7].

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Electrophoresis techniques have become indispensable across diverse scientific and clinical domains. In genomics and molecular biology, agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis remain fundamental for analyzing PCR products, restriction digests, and nucleic acid purity [9] [4]. Capillary electrophoresis has become the gold standard for Sanger sequencing and fragment analysis for genetic testing [4] [6].

In proteomics, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis enables comprehensive analysis of complex protein mixtures, while capillary electrophoresis coupled with mass spectrometry provides high-resolution separation and identification of peptides and proteins [4] [6]. Clinical diagnostics relies heavily on electrophoresis for serum protein analysis, hemoglobin variant detection, and immunofixation electrophoresis for identifying monoclonal gammopathies [2] [5].

Emerging trends point toward increasing integration, miniaturization, and intelligence in electrophoresis systems. The convergence of microfluidics with artificial intelligence is enabling automated image analysis, pattern recognition, and data interpretation from complex electrophoretic separations [8]. The development of organ-on-a-chip platforms that incorporate electrophoretic analysis capabilities is creating new opportunities for drug screening and disease modeling in physiologically relevant environments [7] [8].

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing multi-omics integration, where electrophoretic separations are seamlessly coupled with downstream genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses. Advances in materials science are yielding new polymer matrices with enhanced separation properties and reduced environmental impact [8]. As these technologies continue to evolve, electrophoresis will maintain its central role in advancing our understanding of biological systems and improving human health.

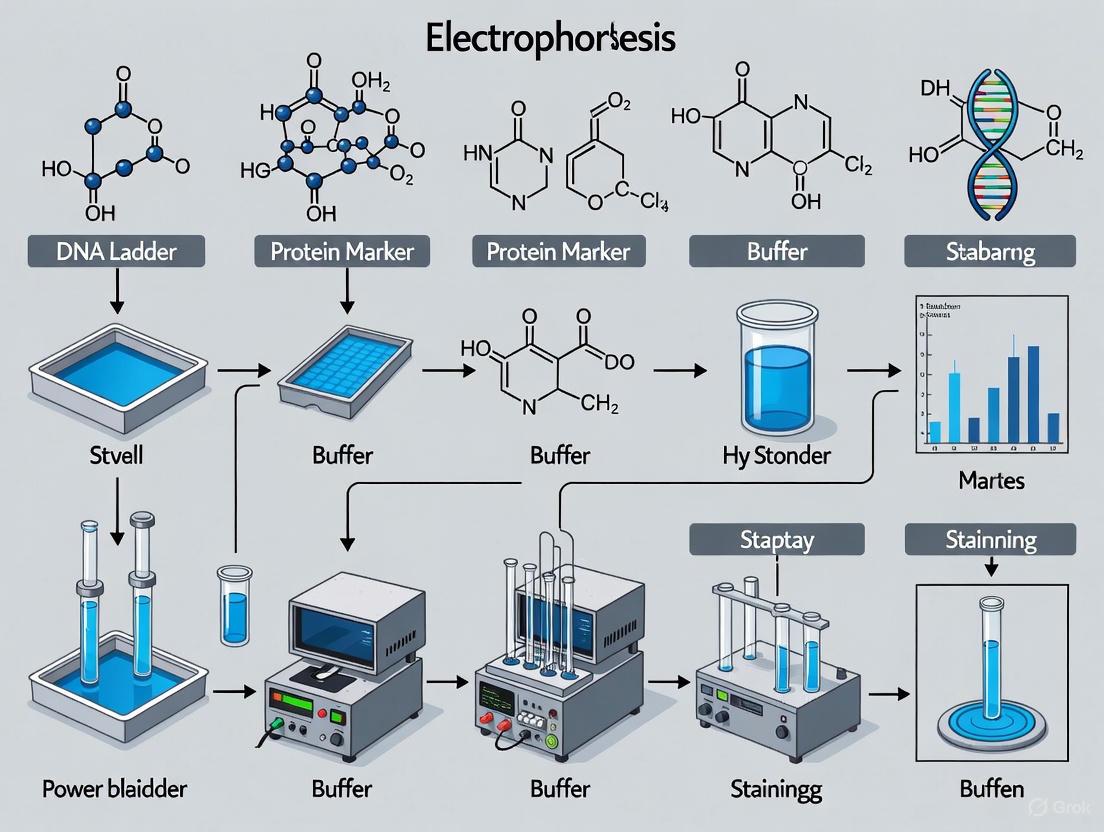

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for agarose gel and microfluidic electrophoresis protocols

Diagram 2: Historical timeline of key developments in electrophoresis technology

Electrophoresis remains a cornerstone technique in biochemical research and clinical diagnostics for the separation and analysis of complex biomolecules. The technique, first demonstrated by Tiselius in 1937, exploits the differential migration of charged particles under the influence of an electric field [5]. The fundamental separation mechanisms governing electrophoretic mobility rely on three core biomolecular properties: charge, size, and shape [5] [4]. A comprehensive understanding of these dynamics is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to select appropriate methodologies, optimize separation conditions, and accurately interpret analytical results for molecules ranging from nucleic acids and proteins to novel biopharmaceutical entities.

This article details the principles and protocols underpinning these separation mechanisms, providing a structured framework for their application in modern biomolecular research.

Core Principles of Electrophoretic Separation

The rate of migration (electrophoretic mobility) of a molecule in an electric field is determined by a balance between the driving force of the electric field and the retarding frictional forces of the medium. The dynamics of this process are governed by several interrelated factors [5] [4].

- Charge: The net charge of a molecule is the primary driver of its electrophoretic mobility. Positively charged cations migrate toward the negative cathode, while negatively charged anions migrate toward the positive anode [5]. The charge of a biomolecule like a protein is highly dependent on the pH of the buffer relative to the molecule's isoelectric point (pI) [4].

- Size: For molecules of similar charge, smaller entities experience less drag and migrate faster through the gel matrix or capillary medium. This inverse relationship between size and mobility is the basis for molecular weight determination [5] [10].

- Shape: The three-dimensional conformation of a molecule affects the frictional drag it experiences. Globular proteins, with their compact structures, exhibit faster mobility compared to fibrous proteins of similar molecular weight [5].

Other critical factors fine-tuning the separation include the strength of the electrical field, the buffer's pH and ionic strength, and the properties of the supporting medium (e.g., pore size) [5] [4]. The following table summarizes the influence of these key parameters.

Table 1: Factors Affecting Electrophoretic Mobility

| Factor | Effect on Mobility | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Net Charge | Directly proportional | Higher charge increases migration speed; controlled by buffer pH [5]. |

| Size/Mass | Inversely proportional | Larger molecules migrate slower; basis for molecular weight analysis [5]. |

| Molecular Shape | Impacts frictional drag | Globular shapes migrate faster than fibrous molecules of similar mass [5]. |

| Electric Field Strength | Directly proportional | Higher voltage speeds up migration but can generate excessive heat [5]. |

| Buffer Ionic Strength | Complex effect | Higher ionic strength increases current but can slow migration and generate heat [5] [4]. |

| Support Medium Pore Size | Impacts molecular sieving | Smaller pores retard larger molecules more effectively; gel concentration controls pore size [5]. |

Key Electrophoresis Techniques and Mechanisms

Different electrophoresis techniques leverage the core principles of charge, size, and shape in distinct ways to achieve specific analytical goals. The workflow below illustrates the decision pathway for selecting the appropriate technique based on research objectives and sample properties.

Diagram 1: Technique selection workflow for common electrophoresis methods.

Gel Electrophoresis: Molecular Sieving

Gel electrophoresis separates molecules primarily by size using a porous gel matrix as a molecular sieve. The two most common media are agarose and polyacrylamide.

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Utilized for separating larger molecules like nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). Agarose gels have larger pores, allowing for the resolution of nucleic acid fragments from dozens to thousands of base pairs [11] [10]. The separation is based on the fact that DNA is uniformly negatively charged, so migration distance is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the molecular weight.

- Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE): Provides finer resolution for smaller molecules, including proteins and small nucleic acids. Its smaller, more uniform pore size allows for the separation of molecules with very slight size differences [5] [10]. A critical variant is SDS-PAGE, where the anionic detergent SDS binds to proteins, masking their native charge and conferring a uniform negative charge-to-mass ratio. SDS also denatures proteins, giving them a uniform rod-like shape. This eliminates the effects of charge and shape, allowing separation based purely on polypeptide chain mass [5].

Capillary Electrophoresis: Electrokinetic Separation

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) performs separations within a narrow-bore fused-silica capillary filled with buffer. The primary separation mechanism is a combination of electrophoretic mobility (governed by a molecule's charge-to-size ratio) and electroosmotic flow (EOF), a bulk flow of buffer solution induced by the charged capillary wall [4] [10]. CE offers high resolution, rapid analysis (often in minutes), automation, and requires only nanoliter sample volumes. It is widely applied in clinical diagnostics (e.g., hemoglobin analysis), pharmaceutical quality control, and DNA sequencing [12] [10].

Isoelectric Focusing: Charge-Based Separation

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) separates molecules based solely on their isoelectric point (pI). The technique uses a gel matrix containing a pH gradient established by ampholytes. When an electric field is applied, molecules migrate until they reach the pH region where their net charge is zero (their pI), at which point migration ceases [5]. This technique provides exceptionally high resolution for separating protein charge variants, such as those with different post-translational modifications.

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis combines IEF and SDS-PAGE to achieve the highest resolution for complex protein mixtures. Proteins are first separated based on their pI by IEF in one dimension. The entire gel strip is then applied to a polyacrylamide gel and subjected to SDS-PAGE in the second dimension, separating the proteins by molecular mass [5]. This orthogonal separation method allows for the resolution of thousands of proteins from a single sample.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major Electrophoresis Techniques

| Technique | Primary Separation Mechanism | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarose Gel | Size (Molecular sieving) | DNA/RNA fragment analysis, PCR verification [11] [10] | Simple, cost-effective, good for large fragments [10] | Lower resolution, manual, qualitative/semi-quantitative [10] |

| SDS-PAGE | Size (Mass of polypeptide chains) | Protein purity, molecular weight estimation, Western blot [5] [10] | Eliminates charge/shape effects, reproducible, widely used [5] | Requires protein denaturation, not for native charge analysis |

| Isoelectric Focusing (IEF) | Charge (Isoelectric point) | Separation of protein isoforms, charge variant analysis [5] | Extremely high resolution for charge-based separation [5] | Requires specific pH gradients, not for size analysis |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Size-to-charge ratio & Electroosmotic Flow | Clinical diagnostics (hemoglobin, serum proteins), DNA sequencing, high-throughput QC [4] [10] | High resolution, fast, automated, low sample volume, quantitative [10] | Higher instrument cost, more complex operation than gel [12] |

| 2D Electrophoresis | Charge (1D) & Size (2D) | Proteomics, complex protein mixture analysis [5] | Highest resolution, can separate thousands of proteins [5] | Technically challenging, time-consuming, low throughput |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: SDS-PAGE for Protein Separation

This protocol describes the standard method for separating proteins by molecular weight using a vertical gel electrophoresis system [5] [11].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials: Table 3: Essential Materials for SDS-PAGE

Item Function Vertical Gel Electrophoresis System Apparatus to hold gel and buffer, provide electrical field [11] Polyacrylamide Gel Support medium with precise pore size for molecular sieving [5] Power Supply Provides controlled electrical current/voltage [11] SDS-PAGE Running Buffer Carries current, maintains pH during run [11] Laemmli Sample Buffer Contains SDS (denatures, confers charge), glycerol (adds density), dye (tracking) [5] Protein Ladder (Molecular Weight Marker) Reference for estimating sample protein sizes [11] Staining Solution (e.g., Coomassie) Visualizes separated protein bands post-run [11] Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with Laemmli sample buffer. Heat denature at 95-100°C for 5 minutes to fully denature proteins and ensure uniform SDS binding [5] [11].

- Gel and Buffer Setup: Assemble the vertical gel apparatus. Pour the running buffer into the upper and lower chambers, ensuring the gel is fully submerged. Remove the comb from the gel to expose the wells [11].

- Sample Loading: Using a micro-pipette, carefully load equal volumes of prepared samples and protein ladder into designated wells. Record the loading order [11].

- Electrophoresis Run: Attach the lid to the apparatus, connecting the electrodes to the power supply. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150 V) until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel (typically 45-90 minutes). Voltage can be optimized for resolution and speed [11].

- Protein Visualization: After the run, turn off the power supply. Disassemble the apparatus and carefully remove the gel. Stain the gel with Coomassie Blue or a fluorescent protein stain to visualize the separated bands. Destain as needed, then image the gel using a digital imager or scanner for analysis [11].

Protocol: Capillary Electrophoresis for Nucleic Acid Analysis

This protocol outlines the general workflow for analyzing DNA fragments using capillary electrophoresis, common in genetic testing and sequencing applications [4] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Capillary Electrophoresis Instrument

- Fused-Silica Capillary

- Separation Matrix (e.g., polymer solution)

- Run Buffer (Electrolyte)

- DNA Size Standard

- Sample Tray and Vials

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Instrument Setup: Install the capillary and initialize the instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prime the capillary with the appropriate separation polymer and run buffer [10].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute DNA samples and internal size standards in the recommended buffer. Transfer the samples to the instrument's sample vials and place them in the designated tray [10].

- Automated Run Sequence: Program the instrument method, specifying injection parameters (pressure or voltage), separation voltage, temperature, and detection settings. The instrument will automatically perform the following steps [10]:

- Electrokinetic Injection: A brief electric field is applied to inject a nanoliter-volume plug of the sample into the capillary.

- Separation: A high voltage (e.g., 5-15 kV) is applied. DNA fragments, which are negatively charged, migrate toward the anode. The polymer matrix acts as a sieve, separating fragments by size.

- On-Column Detection: As separated DNA fragments pass through a detector (typically laser-induced fluorescence) at the end of the capillary, they are detected in real-time.

- Data Analysis: The detector generates an electropherogram, a plot of signal intensity versus migration time. Software converts migration times to fragment sizes based on the internal standard and provides quantitative data on peak area and height [10]. The entire process, from injection to data output, is typically completed in under 30 minutes.

Applications in Biomolecular Research and Drug Development

The precise separation capabilities of electrophoresis techniques make them indispensable across diverse scientific disciplines.

- Genomics and Molecular Biology: Agarose gel electrophoresis is fundamental for analyzing PCR products, restriction digests, and nucleic acid quality control. Capillary electrophoresis is the gold standard for DNA sequencing and fragment analysis (e.g., STR profiling in forensics) [12] [10].

- Proteomics and Biomarker Discovery: 2D electrophoresis remains a powerful tool for profiling complex protein mixtures from cells or tissues, facilitating the discovery of disease-specific biomarkers. SDS-PAGE is a routine step in Western blotting for protein detection and quantification [5] [4].

- Clinical Diagnostics: Electrophoresis is used to separate serum proteins for diagnosing conditions like monoclonal gammopathies and to analyze hemoglobin variants for disorders such as sickle cell disease [5] [10].

- Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Analysis: Electrophoresis techniques are critical for quality control and stability testing of biologics. CE and SDS-PAGE are used to assess drug purity, detect degradation products, and characterize charge heterogeneity of therapeutic proteins like monoclonal antibodies [12] [4] [13].

The separation of biomolecules by electrophoresis is governed by the fundamental dynamics of charge, size, and shape. Mastery of these principles allows researchers to leverage a versatile toolkit—from the classical gel-based methods to advanced automated capillary systems—to solve complex analytical challenges. As research in genomics, proteomics, and biopharmaceuticals advances, these electrophoresis techniques will continue to be vital for driving discovery, ensuring diagnostic accuracy, and maintaining the quality and safety of novel therapeutics.

Electrophoresis is a cornerstone technique in biomolecular research, enabling the separation, analysis, and purification of DNA, RNA, and proteins based on size, charge, and shape. Its applications span critical areas from disease diagnosis and drug development to the elucidation of fundamental molecular pathways [14]. The reproducibility, resolution, and success of any electrophoretic separation are fundamentally dependent on three essential components: the buffer system, the support medium, and the power supply. This application note details the functions, selection criteria, and advanced methodologies for these core components, providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed protocols to optimize their electrophoresis workflows.

The Buffer System: Foundation for Separation

The electrophoresis buffer is an electrolyte solution that serves multiple critical functions: it provides the ions necessary to carry the electrical current, establishes a stable pH to ensure biomolecules maintain their charge, and contributes to the overall ionic strength and conductivity of the system [15] [16].

Composition and Function of Key Buffers

Different buffers are optimized for specific applications. The table below summarizes the properties of common electrophoresis buffers.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Gel Electrophoresis Buffers

| Buffer | Full Name & Key Components | Useful pH Range | pKa (25°C) | Conductivity & Heat Generation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAE | Tris-Acetate-EDTA [16] | 7.5 - 9.0 [17] | 7.8 - 8.2 [17] | Higher conductivity, more heat [16] | Larger DNA fragments (>1 kb); DNA recovery post-electrophoresis [16] |

| TBE | Tris-Borate-EDTA [16] | Not explicitly stated | Not explicitly stated | Lower conductivity, less heat, allows higher voltage [16] | Smaller DNA fragments (<1 kb); high-resolution separations [16] |

| Tricine | N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]glycine [14] | 7.4 - 8.8 [17] | 8.0 - 8.3 [17] | Used in low-conductivity BGE for CE [14] | Peptide and protein separation; capillary electrophoresis [17] |

| Bicine | N,N-Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)glycine [17] | 7.6 - 9.0 [17] | 8.1 - 8.5 [17] | Not explicitly stated | Specialized protein separations (e.g., membrane proteins) [17] |

| CHES | 2-(Cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid [17] | 9.7 - 11.1 [17] | 10.2 - 10.6 [17] | Not explicitly stated | Capillary electrophoresis at alkaline pH [17] |

The Critical Role of Conductivity

The ionic strength of the buffer determines its conductivity, which directly impacts the electric field strength and heat generation during a run. Managing conductivity is crucial. High-conductivity buffers, such as Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), are often necessary to maintain biomolecular interactions under physiological conditions. However, when used in capillary electrophoresis (CE) with a low-conductivity Background Electrolyte (BGE), they can cause significant artifacts like peak broadening, splitting, and distortion, ultimately reducing measurement accuracy in binding assays [14]. Conversely, low-conductivity buffers like Tris-Borate or Sodium Borate (SB) allow for higher applied voltages and faster run times with reduced Joule heating [16].

Best Practice: For consistent results, the ionic system of the gel casting buffer and the running buffer should be matched or closely compatible to maintain steady pH and field strength [15].

Support Media: The Separation Matrix

The support medium, or gel matrix, provides a porous structure through which biomolecules migrate. The choice of medium depends on the size of the molecules being separated and the required resolution.

- Agarose Gels: Derived from seaweed, agarose forms a porous matrix with large pore sizes, making it ideal for separating large nucleic acid fragments (from dozens to thousands of base pairs). It is typically used at concentrations between 0.5% and 2% [15] [16].

- Polyacrylamide Gels (PAGE): These gels are formed through the polymerization of acrylamide monomers into a cross-linked mesh-like matrix with much smaller pores than agarose. They are the preferred medium for separating proteins and small nucleic acids with high resolution. The pore size can be precisely controlled by adjusting the concentration of acrylamide and the cross-linker [18].

The matrix functions as a molecular sieve, allowing smaller molecules to migrate faster while larger molecules are retarded [18]. In techniques like SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, ensuring separation is based almost exclusively on molecular weight [18].

Power Systems: Driving the Separation

The power supply is the engine of electrophoresis, providing the stable electrical current necessary for driving the separation of biomolecules. Its performance is a critical determinant of experimental reproducibility [19] [20].

Operational Modes

Power supplies operate in three primary modes, each suited to different applications:

Table 2: Operational Modes of Electrophoresis Power Supplies

| Mode | Principle | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Voltage | Voltage remains fixed; current and power can fluctuate [19]. | DNA separation on agarose gels [19]. | Simple and reliable for standard runs [19]. |

| Constant Current | Current remains fixed; voltage and power can fluctuate [19]. | Protein separation (SDS-PAGE) [19]. | Maintains uniform migration rate and prevents band distortion ("smiling") from uneven heating [19]. |

| Constant Power | Power (the product of V and I) remains fixed; voltage and current fluctuate [19]. | Sensitive separations requiring strict temperature control [19]. | Prevents sample degradation by ensuring a consistent rate of heat generation [19]. |

Technical Specifications and Market Trends

When selecting a power supply, key specifications to consider include voltage/current range, power output (in watts), and the number of outputs for running multiple gels simultaneously [19]. The market for high-current power supplies is evolving, with a projected growth from USD 689.2 million in 2025 to USD 1,020.2 million by 2035, driven by expanding molecular biology workflows [21]. Modern units are increasingly featuring programmable interfaces, safety interlocks (e.g., lid interrupts), overheating protection, and integration with laboratory information management systems for enhanced reproducibility and data tracking [21] [19] [20].

Advanced Application: A Protocol for Studying Biomolecular Interactions via Capillary Electrophoresis

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) is a powerful tool for quantifying biomolecular interactions, such as aptamer-protein binding, due to its high speed, low sample consumption, and adaptability [14]. The following protocol outlines a method for studying these interactions, even under challenging high-conductivity conditions.

Background and Principle

Methods like Affinity Probe Capillary Electrophoresis (APCE) and Nonequilibrium Capillary Electrophoresis of Equilibrium Mixtures (NECEEM) involve introducing pre-equilibrated ligand-target mixtures into the capillary. If the free and bound species have different electrophoretic mobilities, they can be separated and quantified to determine binding parameters such as the dissociation constant (Kd) [14]. A major challenge arises when the sample buffer has higher conductivity than the BGE, leading to peak distortions and reduced accuracy. This protocol includes strategies to mitigate these effects [14].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Aptamer-Protein Binding Assay

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| FAM-labeled DNA Aptamer | The fluorescently labeled ligand (e.g., a 29mer thrombin-binding aptamer) whose binding is being studied [14]. |

| Target Protein | The target molecule (e.g., thrombin or Human Serum Albumin) [14]. |

| Low-Conductivity BGE | Background Electrolyte (e.g., 30 mM Tricine buffer). Low conductivity is preferred for faster separations and reduced Joule heating [14]. |

| High-Conductivity Sample Buffer | Sample buffer (e.g., 1x PBS or 2x Tris-Glycine) used to maintain physiological or binding-compatible conditions [14]. |

| CE Instrument with LIF Detection | A capillary electrophoresis system equipped with a Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) detector for sensitive detection of labeled aptamers [14]. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key steps of the capillary electrophoresis binding assay.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Reconstitute the FAM-labeled DNA aptamer (e.g., 5′-FAM-AGT CCG TGG TAG GGC AGG TTG GGG TGA CT-3′) in Tris-EDTA buffer [14].

- Heat-cycling: Prior to sample preparation, heat the aptamer in its sample buffer to 95°C for 3 minutes, then allow it to cool to room temperature. This step ensures a consistent secondary structure [14].

- Prepare a series of samples with a constant concentration of aptamer and varying concentrations of the target protein (e.g., thrombin) in a high-conductivity sample buffer (e.g., 1x PBS).

- Incubation: Allow the samples to incubate at room temperature for 1 hour to reach binding equilibrium [14].

Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Use a capillary filled with a low-conductivity BGE, such as 30 mM Tricine [14].

- Injection: Inject the equilibrated sample mixture into the capillary. Critical Note: To minimize artifacts caused by the conductivity mismatch, use a short injection time to reduce the length of the high-conductivity sample plug [14].

- Separation: Apply a separation voltage. The local electric field is inversely related to local conductivity, meaning the high-conductivity sample plug will create a low-field zone, potentially causing de-stacking and band broadening [14].

Data Analysis and Quantification:

- Traditional Peak Analysis: If the separation is successful and produces distinct peaks for the free aptamer and the aptamer-protein complex, quantify the areas under these peaks [14].

- Alternative "De-stacked" Fraction Analysis: Under large conductivity mismatches (e.g., PBS sample buffer vs. Tricine BGE), distinct peaks may not form. The sample zone becomes broad and indistinct. In this case, an alternative method is to quantify the fraction of aptamer that has "escaped" the diffuse sample zone as a sharp, de-stacked peak. This fraction can be correlated with the binding parameters [14].

- Fitting Binding Data: Plot the fraction bound (or the de-stacked fraction) against the target protein concentration and fit the data to an appropriate binding model (e.g., Hill equation) to determine the dissociation constant (Kd) and the Hill coefficient (n) [14].

Integrated Workflow and Technological Advancements

A modern electrophoresis workflow integrates the three core components with advanced instrumentation for data capture and analysis. Gel documentation systems, essential for recording results, now feature high-resolution CCD cameras, broad dynamic range, and sensitive detection for various stains and blots [18] [22]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence is revolutionizing data interpretation. The AI-powered tool GelGenie can automatically identify bands in gel images via segmentation, surpassing the capabilities of traditional software in both ease-of-use and versatility, and providing results that quantitatively match manual analyses [23].

The synergy of optimized buffers, appropriate support media, a stable power supply, and advanced analysis tools ensures that electrophoresis remains a robust, reproducible, and indispensable technique in biomolecular research and drug development.

Gel electrophoresis remains a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry laboratories worldwide for the separation of biomolecules such as nucleic acids and proteins [24]. The fundamental principle of this technique involves the movement of charged molecules through a porous matrix under the influence of an electric field, separating them based on size, charge, or conformation. The fidelity and reproducibility of an experiment fundamentally depend on the careful selection of the appropriate gel matrix [24]. The two primary matrices employed for this purpose are agarose and polyacrylamide. While both serve as molecular sieves, their unique physical and chemical properties dictate their specific suitability for different classes of macromolecules and experimental objectives [24] [25]. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of agarose and polyacrylamide gels, framed within the context of biomolecule separation research, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in making an informed selection tailored to their specific needs.

Fundamental Properties and Separation Mechanisms

Agarose Gels: Structure and Sieving Properties

Agarose is a polysaccharide polymer extracted from seaweed genera such as Gelidium and Gracilaria [26]. It consists of repeated agarobiose (L- and D-galactose) subunits [26]. The gel matrix is formed by non-covalent association of linear polysaccharide chains, which, upon cooling, form a three-dimensional lattice with relatively large and non-uniform pores [24] [26]. The pore size is influenced by the agarose concentration, with lower percentages (e.g., 0.5%) producing larger pores suitable for separating very large molecules, and higher percentages (e.g., 2%) yielding smaller pores for resolving smaller fragments [24] [9]. The leading model for DNA movement through an agarose gel is "biased reptation," whereby the leading edge of the DNA molecule moves forward and pulls the rest of the molecule along [26]. Agarose gels are particularly valued for their ease of preparation, non-toxic nature, and ability to separate large DNA fragments ranging from 100 base pairs (bp) to 25 kilobase pairs (kbp) and beyond [24] [26].

Polyacrylamide Gels: Structure and Sieving Properties

In contrast, polyacrylamide gel is a synthetic polymer formed through a chemical polymerization reaction involving acrylamide monomers and a crosslinker, most commonly N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (bis-acrylamide) [24]. Acrylamide monomers form long chains, while bis-acrylamide connects these chains to create a tight, highly ordered, and uniform three-dimensional mesh [24]. The key advantage of polyacrylamide gels is the precise control over pore size, which can be finely tuned by adjusting the total monomer concentration (%T) and the crosslinker ratio (%C) [24]. A higher %T results in a denser matrix with smaller pores, offering superior resolution for smaller molecules, allowing separation of proteins or nucleic acids with very minimal mass differences [24]. It is critical to note that unpolymerized acrylamide is a potent neurotoxin, requiring strict safety protocols including gloves and a lab coat during handling and preparation [24] [27].

Comparative Analysis of Physical Properties

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Agarose and Polyacrylamide Gels

| Property | Agarose Gel | Polyacrylamide Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Polysaccharide from seaweed [24] | Synthetic polymer of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide [24] |

| Polymerization | Physical, non-covalent association upon cooling [24] | Chemical, free radical-driven polymerization [24] |

| Pore Size | Large, non-uniform [24] | Small, uniform, and tunable [24] |

| Typical Pore Control | Adjusted via agarose concentration [24] | Precisely tuned via %T and %C [24] |

| Toxicity | Non-toxic [24] | Neurotoxic monomer (acrylamide) [24] [27] |

| Typical Gel Format | Horizontal slabs [26] | Vertical slabs [24] |

Applications in Biomolecule Separation

Applications of Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

The primary application of agarose gel electrophoresis is the separation of nucleic acids, specifically double-stranded DNA and RNA [24] [26]. Given the large size of most DNA fragments, the flexible and large-pored structure of agarose is ideally suited for their migration. DNA molecules, which are negatively charged due to their phosphate backbone, migrate toward the positive anode, with smaller fragments moving more quickly through the matrix than larger ones [26]. The concentration of the agarose gel is critical for achieving optimal separation, as shown in Table 2 [27]. Agarose gel electrophoresis is the standard method for applications such as genotyping, verifying PCR amplification products, plasmid DNA purification, and DNA quantification [24] [9]. For separating very large chromosomal DNA fragments (e.g., >25-50 kb), a specialized technique called Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) is used, which involves periodically changing the direction of the electric field [24] [26].

Applications of Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is the matrix of choice for separating proteins and very small nucleic acids [24]. The tight, uniform pores provide the high resolution necessary to resolve molecules with small mass differences. For protein analysis, the most common form is Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE), where the detergent SDS denatures proteins and imparts a uniform negative charge, ensuring separation is based almost exclusively on molecular weight [24]. For the analysis of proteins in their native, folded state, non-denaturing or Native PAGE is used [24]. Furthermore, polyacrylamide gels are indispensable for resolving very short DNA or RNA fragments (e.g., primers, siRNAs, microRNAs) or for techniques requiring single-base-pair resolution, such as in SNP analysis or Sanger sequencing [24] [27]. Specialized variants like Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) are powerful tools for studying intact protein complexes, such as the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes and their superstructures [28].

Table 2: Optimal Gel Concentrations for Size-Based Separation

| Agarose Gels | Polyacrylamide Gels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| % Agarose | Optimum Resolution (bp) | % Acrylamide | Optimum Resolution (bp) |

| 0.5% | 1,000 - 30,000 [27] | 3.5% | 1,000 - 2,000 [27] |

| 0.7% | 800 - 12,000 [27] | 5.0% | 80 - 500 [27] |

| 1.0% | 500 - 10,000 [27] | 8.0% | 60 - 400 [27] |

| 1.2% | 400 - 700 [27] | 12.0% | 25 - 150 [27] |

| 1.5% | 200 - 500 [27] | 15.0% | 25 - 150 [27] |

| 2.0% | 100 - 500 [24] [9] | 20.0% | 6 - 100 [27] |

Orthogonal and Emerging Techniques

While gel-based methods are foundational, capillary electromigration methods represent a powerful orthogonal and complementary approach for protein analysis [29] [30]. Techniques such as Capillary Zone Electrophoresis (CZE) and Capillary Isoelectric Focusing (CIEF) offer high separation efficiency, automation, and minimal sample consumption, making them particularly valuable in biopharmaceutical quality control, especially for monoclonal antibodies and their biosimilars [29]. Furthermore, innovative methods are continuously being developed to enhance the capabilities of traditional gels. For instance, a recent advancement describes a facile and sensitive immune PAGE with online fluorescence imaging (PAGE-FI), which allows for rapid, specific, and quantitative detection of a target protein directly within the gel, overcoming the limitations of complex Western blot procedures [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for DNA Analysis

This protocol is adapted from standard laboratory methods for casting and running a 1% agarose gel [26] [9].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Prepare the Gel Mold: Place the gel casting tray on a level surface. Insert a well comb of the desired size and thickness, ensuring it does not touch the bottom of the tray [26] [9].

- Prepare Agarose Solution: Weigh 1.0 g of agarose powder and add it to 100 mL of 1x TAE (or TBE) buffer in a heat-resistant Erlenmeyer flask. The flask should not be more than one-third full to prevent boiling over [9].

- Dissolve Agarose: Microwave the mixture in short bursts (30-45 seconds), swirling gently between intervals until the agarose is completely dissolved and the solution appears clear. Caution: The solution will be very hot and may eruptively boil. Use appropriate protection. [9].

- Cool the Solution: Allow the molten agarose to cool on the benchtop until the flask is comfortable to hold (approx. 50-60°C). This prevents warping of the casting tray and reduces evaporation of the staining dye [26] [9].

- Add Nucleic Acid Stain (Optional): For post-staining, skip this step. For in-gel staining, add a mutagenic dye like ethidium bromide (EtBr) to a final concentration of 0.2-0.5 µg/mL and swirl to mix evenly. Caution: EtBr is a known mutagen. Wear gloves, a lab coat, and eye protection. Alternatively, use safer, non-mutagenic fluorescent dyes like SYBR Safe or GelRed. [26] [9] [27].

- Cast the Gel: Slowly pour the molten agarose into the prepared gel mold, avoiding air bubbles. If bubbles form, they can be moved to the edge with a pipette tip. Let the gel solidify completely at room temperature for 20-30 minutes. It will appear opaque and firm when ready [26] [9].

- Load Samples: Once solidified, carefully remove the comb and place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber. Cover the gel with the same running buffer (1x TAE/TBE) used for casting. Mix DNA samples with a 6X gel loading dye. Load a DNA molecular weight ladder into the first lane, then load your samples into subsequent lanes [26] [9].

- Run Electrophoresis: Connect the electrodes to the power supply (black to cathode, red to anode). Run the gel at 80-150 V until the dye front has migrated 75-80% of the way down the gel. A typical run time is 1-1.5 hours [9].

- Visualize DNA: Turn off the power supply. If not stained in-gel, follow the destaining protocol. Using a UV transilluminator or gel documentation system, visualize the DNA bands. Caution: Wear UV-protective eyewear. [26] [9].

Protocol: SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for Proteins

This protocol outlines the key steps for protein separation using a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, typically using a pre-cast gel for convenience and safety.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute protein samples in an appropriate SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or DTT). Heat the samples at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to fully denature the proteins [24] [31].

- Set Up Gel Apparatus: For pre-cast gels, remove the tape from the bottom and carefully remove the comb. Place the gel into the vertical electrophoresis module. Fill the inner and outer chambers with the recommended running buffer (e.g., 1x Tris-Glycine-SDS) [31].

- Load Samples: Using a gel-loading pipette tip, slowly load the denatured protein samples and a pre-stained protein molecular weight marker into the wells [31].

- Run Electrophoresis: Attach the lid, connecting the electrodes to the correct terminals. Run the gel at a constant voltage as recommended by the gel manufacturer (e.g., 150-200 V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [24].

- Protein Detection: After electrophoresis, proteins can be visualized using various staining methods. Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining is common for general purposes, while silver staining offers higher sensitivity. For specific detection, the gel can be used for Western blotting [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose | Forms the porous matrix for nucleic acid separation [26]. | Choose concentration based on target DNA size; low EEO (Electroendosmosis) grade is preferred for sharp bands [26] [27]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer mesh for high-resolution separation of proteins and small nucleic acids [24]. | Potent neurotoxin in monomeric form. Use gloves and mask when handling powder; pre-mixed solutions or pre-cast gels are safer [24] [27]. |

| TAE or TBE Buffer | Provides the conducting ionic medium for electrophoresis and maintains stable pH [9] [27]. | TBE provides sharper bands, especially for small DNA, but borate can inhibit downstream enzymes. TAE is more common for standard DNA gels [27]. |

| DNA/Protein Ladder | A mix of fragments of known sizes used as a reference to estimate the size of unknown samples [26] [9]. | Essential for accurate size determination. Choose a ladder with a range that covers your fragments of interest. |

| Gel Loading Dye | Contains a visible dye to track migration and glycerol/sucrose to increase sample density for well loading [26] [9]. | Common dyes: Bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol. Their migration varies with gel type and concentration [27]. |

| Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) | Intercalating dye that fluoresces under UV light, allowing visualization of nucleic acids [26] [9]. | Known mutagen. Requires careful handling and disposal. Safer alternatives (e.g., SYBR Safe, GelRed) are recommended [26] [27]. |

| Coomassie Blue/Silver Stain | Stains proteins for visualization in polyacrylamide gels [31]. | Coomassie is less sensitive; silver staining offers high sensitivity but is more complex [31]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and imparts a uniform negative charge per unit mass [24]. | Critical for SDS-PAGE to ensure separation is based solely on molecular weight, not native charge or shape [24]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the chemical polymerization of acrylamide gels [27]. | APS should be fresh or aliquoted and stored at -20°C for efficient and complete polymerization [27]. |

Concluding Remarks

The choice between agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis is a foundational decision that impacts the entire experimental process, from sample preparation to data analysis [24]. Agarose gels, with their robust and easily-prepared matrix, excel in the separation of large nucleic acids, making them the workhorse for most DNA and RNA analyses in research and diagnostics. In contrast, polyacrylamide gels, with their fine-tuned pore structure, are the superior choice for high-resolution separation of proteins and small nucleic acid fragments. This selection is not merely a technicality but a strategic consideration that balances the size of the target molecules, the required resolution, and laboratory safety considerations. By making an informed choice, researchers can streamline their workflows, enhance the reliability of their results, and push the boundaries of molecular analysis in basic research and drug development.

Within biomolecule separation research, electrophoresis is a foundational technique whose resolution and efficacy are profoundly influenced by three key physicochemical parameters: pH, ionic strength, and temperature. The controlled manipulation of these factors is critical for developing robust, reproducible, and high-resolution analytical methods for proteins, nucleic acids, and other charged species. This application note details the quantitative effects of these parameters and provides standardized protocols for their optimization, framed within the context of advanced electrophoresis techniques for drug development and life science research.

The separation of charged particles in an electric field is governed by their electrophoretic mobility, which is directly affected by the molecule's net charge, size, and shape, as well as the properties of the surrounding medium [5]. The pH of the background electrolyte (BGE) determines the ionization state of both the analytes and the capillary or gel matrix, the ionic strength governs current flow and heat generation, and temperature impacts buffer viscosity and biomolecule stability. A systematic understanding of their interplay is a prerequisite for successful method development in techniques ranging from capillary electrophoresis (CE) to gel-based analyses [32].

Quantitative Effects of Key Parameters

The following tables summarize the core effects and optimal ranges for pH, ionic strength, and temperature in electrophoresis.

Table 1: Core Effects of Key Parameters on Electrophoretic Separation

| Parameter | Primary Effect | Impact on Resolution | Consequence of Improper Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Determines the net charge and ionization state of analytes and the capillary wall [32] [5]. | Directly controls selectivity and migration velocity; critical for separation tuning [32]. | Altered migration order, poor peak shape, adsorption to capillary wall, incomplete separation. |

| Ionic Strength | Controls the electrical conductivity, current, and Joule heating [32] [5]. | Higher ionic strength can enhance efficiency by reducing band broadening from diffusion, but excess causes high current and heat [32]. | Excessive Joule heating leading to band broadening; low ionic strength reduces resolution and can cause peak distortion. |

| Temperature | Affects buffer viscosity, analyte diffusion, and reaction rates (e.g., in SDS-PAGE) [32] [5]. | Stabilized temperature is vital for high efficiency; reduces viscosity for faster analysis and consistent mobility [32]. | Band broadening due to thermal gradients, decreased reproducibility, and inconsistent migration times. |

Table 2: Optimizing Parameter Ranges for Different Techniques

| Technique / Analyte | Recommended pH Range | Recommended Ionic Strength | Recommended Temperature Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary Electrophoresis (General) | pH dictates analyte charge. For acids, use higher pH; for bases, use lower pH to increase net charge [32]. | 20-100 mM for standard BGEs; balance between efficiency and heat generation [32]. | Active cooling (forced-air or liquid) is essential; voltage is optimized to maintain stable current [32]. |

| Isoelectric Focusing | Uses a stable pH gradient; analytes migrate to their isoelectric point (pI) [5]. | Determined by ampholyte concentration; must form a stable gradient. | Controlled to prevent gradient disruption and ensure reproducible pI migration. |

| SDS-PAGE | Typically run at alkaline pH (e.g., Tris-glycine, pH ~8.3-8.8) for uniform negative charge on proteins [5]. | Buffer concentration affects migration sharpness and Laemmli buffer system stability. | Often run with cooling to manage heat from high voltages, preventing gel distortion. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (DNA) | Neutral to alkaline pH (e.g., TAE or TBE, pH ~8.0) to maintain DNA negative charge [9]. | Standardized in TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA) or TBE (89 mM Tris-borate, 2 mM EDTA) [9]. | Often run at room temperature; for high voltages, cooling may be applied to prevent gel melting. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of BGE pH and Ionic Strength

This protocol is designed for developing a new CE or gel electrophoresis method where the optimal BGE composition is unknown.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Background electrolyte components (e.g., Tris, Borate, Phosphate)

- HCl and NaOH for pH adjustment

- Analytic standards

- Deionized water

- Capillary electrophoresis system or gel electrophoresis apparatus

- pH meter

II. Procedure

- Prepare BGE Stock Solutions: Prepare a concentrated stock solution (e.g., 200 mM) of your chosen buffer.

- Create pH Series: Dilute the stock to an intermediate ionic strength (e.g., 50 mM). Divide into aliquots and adjust each to a different pH across a relevant range (e.g., pH 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0) using HCl or NaOH.

- Create Ionic Strength Series: At the pH that shows the best initial separation, prepare a series of BGEs with varying ionic strengths (e.g., 20, 50, 75, 100 mM) by diluting the stock solution.

- Execute Electrophoresis Runs: For each BGE condition, perform the separation using identical samples, injection parameters, and voltage settings.

- Analyze Data: Record migration times, peak areas, and resolution between critical analyte pairs. Plot resolution as a function of pH and ionic strength to identify optimal conditions.

Protocol 2: Assessing and Controlling for Joule Heating Effects

This protocol outlines a voltage study to determine the maximum operating voltage before Joule heating degrades separation.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Optimized BGE from Protocol 1

- Capillary electrophoresis system with active temperature control

II. Procedure

- Set Constant Temperature: Stabilize the capillary cartridge at a standard temperature (e.g., 25 °C).

- Run Voltage Gradient: Using the optimized BGE, run the same standard sample at increasing voltages (e.g., 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 kV).

- Monitor Current: Record the current at each voltage setting. A linear current-voltage relationship indicates minimal Joule heating. A non-linear increase signals significant heating.

- Evaluate Performance: For each run, calculate the efficiency (theoretical plates) for a key analyte. Observe peak shape and baseline resolution.

- Determine Optimal Voltage: Select the voltage that provides the best compromise between analysis speed, efficiency, and resolution, while maintaining a stable, linear current profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrophoresis Method Development

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Key Property |

|---|---|---|

| Background Electrolyte (BGE) Salts | Carries current and maintains pH; choice of ion affects electroosmotic flow (EOF) and analyte mobility [32] [5]. | Tris-borate, Tris-acetate, Phosphate. |

| Capillary Coating (Dynamic) | Additive adsorbed to the capillary wall to suppress analyte-wall interactions and stabilize/alter EOF [32]. | Polybrene (for positive coating), hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (neutral). |

| Chiral Selectors | Added to BGE to separate enantiomers via formation of transient diastereomeric complexes [32]. | Cyclodextrins (α-, β-, γ- and derivatives). |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents | Introduces a pseudostationary phase for separating neutral molecules (e.g., in Micellar Electrokinetic Chromatography) [32]. | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS). |

| Organic Modifiers | Added to BGE to alter selectivity, hydrophobicity, and viscosity [32]. | Methanol, Acetonitrile. |

| Ultrapure Agarose | Gel matrix for separating larger biomolecules like DNA and proteins; low sulfate content minimizes electroendosmosis [9] [5]. | < 0.1% sulfate content. |

| Polyacrylamide | Gel matrix for high-resolution separation of proteins and nucleic acids; pore size is tunable [5]. | Formed from acrylamide and bis-acrylamide. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Electrophoresis Method Development Workflow

Parameter Interrelationships in Electrophoresis

The field of biomolecule separation is undergoing a transformative shift, moving from traditional manual techniques toward highly integrated, automated microfluidic platforms. Conventional electrophoresis, while foundational, often involves sequential, labor-intensive processes prone to user-induced variability and contamination [5] [33]. Microfluidics, the science of manipulating small fluid volumes in micrometer-scale channels, directly addresses these limitations by enabling the miniaturization and integration of entire laboratory workflows onto single chips, known as Lab-on-a-Chip (LOC) devices [7] [8]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is further advancing these systems from simple automation to intelligent platforms capable of real-time decision-making and optimization [34]. This evolution is critical for applications demanding high reproducibility and throughput, such as drug discovery, point-of-care diagnostics, and personalized medicine [7] [8] [34]. This article explores these emerging trends, providing detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing automated microfluidic systems in biomolecule research.

From Traditional Electrophoresis to Integrated Microsystems

Limitations of Conventional Platforms

Traditional gel electrophoresis, a workhorse technique for separating nucleic acids and proteins, relies on a multi-step process: gel preparation, sample loading, electrophoresis, and visualization [11]. This workflow presents several challenges:

- Operator Dependency: Manual sample handling, gel pouring, and buffer preparation introduce significant variability, reducing inter-experiment reproducibility [33].

- Time and Resource Intensity: Processes like hand-casting gels and extended run times can be lengthy, while the volumes of samples and reagents required are relatively large [11].

- Analytical Bottlenecks: Post-separation analysis often requires additional manual steps, such as staining, de-staining, and band quantification, which are difficult to scale for high-throughput applications [5] [11].

Microfluidic integration consolidates these disparate steps into a seamless, automated workflow, directly confronting the limitations of conventional methods [33].

Principles of Microfluidic Electrophoresis

At the microscale, fluid behavior is governed by unique physical principles. The Reynolds number is low, resulting in laminar flow, where fluids move in parallel layers without turbulent mixing [7]. This enables precise spatial control of samples within microchannels. Furthermore, the high surface-to-volume ratio enhances heat dissipation, allowing for the application of higher electric fields, which dramatically accelerates separation times compared to standard gel boxes [7] [8]. Capillary electrophoresis (CE), a precursor to more complex microsystems, leverages these principles in narrow bore tubes, separating molecules based on their charge-to-size ratio with high efficiency and speed [5] [35].

Intelligent Microfluidics and Automated Platforms

The convergence of microfluidics with advanced control systems and AI has given rise to a new generation of "intelligent" platforms that transcend simple automation.

AI and Machine Learning Integration

AI and ML algorithms are being deployed to enhance nearly every aspect of microfluidic operation, moving systems toward autonomous decision-making [34]. Key applications include:

- Real-time Analysis and Classification: Deep learning models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), can process image data from within microchannels to classify cells or analyze results without manual intervention. For instance, CNNs have classified thousands of cells per second (e.g., leukemia cells, RBCs) with over 96% accuracy, and have been used to predict tumor cell viability in drug susceptibility testing based on morphological changes [34].

- Predictive Fluid Dynamics: AI-driven simulations can predict fluid behavior within complex channel geometries much faster than traditional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models, aiding in the design and control of devices [34].

- Generative Design: AI can autonomously generate and optimize microfluidic chip designs to maximize performance metrics such as mixing efficiency or separation resolution while minimizing material use [34].

- Process Optimization: Reinforcement learning (RL) has been applied to optimize the operation of components like peristaltic micropumps, improving critical parameters such as maximum flow rate [34].

Automated "Sample-to-Answer" Systems