Automated Synthesis in Academia: Accelerating Discovery and Democratizing Research

This article explores the transformative impact of automated synthesis technologies on academic research labs.

Automated Synthesis in Academia: Accelerating Discovery and Democratizing Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of automated synthesis technologies on academic research labs. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive guide from foundational concepts to real-world validation. We cover the core technologies powering modern labs—robotics, AI, and the Internet of Things—and detail their practical application in workflows like high-throughput experimentation and self-driving laboratories. The article also addresses common implementation challenges, offers optimization strategies, and presents compelling case studies and metrics that demonstrate significant gains in research speed, cost-efficiency, and innovation. The goal is to equip academic scientists with the knowledge to harness automation, fundamentally reshaping the pace and scope of scientific discovery.

The Automated Lab Revolution: Core Concepts and Technologies

The concept of the "Lab of the Future" represents a fundamental transformation in how scientific research is conducted, moving from traditional, manual laboratory environments to highly efficient, data-driven hubs of discovery. This revolution is characterized by the convergence of automation, artificial intelligence, and connectivity to accelerate research and development like never before. By 2026, these innovations are poised to completely reshape everything from drug discovery to diagnostics, creating environments where scientists are liberated from repetitive tasks and empowered to focus on creative problem-solving and breakthrough discoveries [1].

The transition to these advanced research environments aligns with the broader industry shift termed "Industry 4.0," driven by technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), data analytics, and machine learning that are transforming life sciences research [2]. This evolution goes beyond merely digitizing paper processes—it represents a fundamental rethinking of how scientific data flows through an organization, enabling a "right-first-time" approach that dramatically improves speed, agility, quality, and R&D efficiency [1]. For academic research labs specifically, the implementation of automated synthesis and data-driven methodologies offers unprecedented opportunities to enhance research productivity, reproducibility, and impact.

Core Technologies Powering the Modern Laboratory

The Lab of the Future is built upon several interconnected technological foundations that together create an infrastructure capable of supporting accelerated scientific discovery.

Automation and Robotics

Automation and robotics handle routine tasks like sample preparation, pipetting, and data collection, significantly reducing human error while freeing scientists to focus on more complex analysis and innovation [1]. In 2025, automation is becoming more widely deployed within laboratories, particularly in processes like manual aliquoting and pre-analytical steps of assay workflows [2]. Robotic arms and automated pipetting systems are now commonplace, allowing for precise and repeatable processes that enable high-throughput screening and more reliable experimental results [3]. Studies show that automated systems can significantly reduce sample mismanagement and storage costs in laboratory environments [1].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and machine learning are transforming laboratory operations by assisting with data analysis, pattern recognition, experiment planning, and suggesting next experimental steps [1]. These technologies excel in processing large datasets, detecting latent patterns, and generating predictive insights that traditional methods struggle to uncover [4]. Beyond automating tasks, AI enables more sophisticated applications; for instance, AI-driven robotic systems can learn from data and optimize laboratory processes by adjusting to changing conditions in real-time [1]. In research impact science, machine learning models have been used to forecast citation trends, analyze collaboration networks, and evaluate institutional research performance through big data analytics [4].

Data Management and Connectivity

The Internet of Things (IoT) and enhanced connectivity are revolutionizing how laboratory equipment communicates and shares data. Smart laboratory equipment, enabled by IoT technology, allows scientists to monitor, control, and optimize laboratory conditions in real-time [1]. This connectivity significantly improves the efficiency of lab-based processes, ultimately allowing professionals to focus more time on delivering collaborative research [2]. Additionally, cloud computing provides secure data management and analysis capabilities that are transforming how research is conducted and shared [1]. Modern laboratories are increasingly adopting advanced Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) that streamline data management, enhance collaboration, and ensure regulatory compliance [3].

Advanced Analytics and Visualization

With laboratories managing vast volumes of complex data, advanced analytics and visualization tools are becoming essential for identifying trends, streamlining operations, and improving research decision-making [1] [2]. When combined with AI, these technologies help transform laboratory operations by reducing costs and enhancing compliance with regulatory standards [1]. By analyzing complex datasets, they can identify potential workflow bottlenecks or underperforming processes, allowing personnel to address inefficiencies that might otherwise be missed [2]. The emerging field of "augmented analytics" represents the next evolution of these tools, democratizing analytics by letting non-technical researchers uncover patterns with AI-driven nudges [5].

Virtual and Augmented Reality

Visualization tools like augmented reality are enhancing what researchers see with digital information, such as safety procedures and batch numbers [1]. Meanwhile, virtual reality allows aspects of the lab to be accessed remotely for purposes such as training, creating controlled learning environments that minimize resource wastage [1]. These technologies are creating environments where virtual and physical components work together seamlessly, enabling researchers to simulate biological processes, test hypotheses, and plan experiments virtually before conducting physical experiments [1].

Table 1: Core Technologies in the Lab of the Future

| Technology | Primary Function | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Automation & Robotics | Handles routine tasks and sample processing | High-throughput screening, sample preparation, complex assay workflows |

| AI & Machine Learning | Data analysis, pattern recognition, experimental planning | Predictive modeling, experimental optimization, knowledge extraction from literature |

| IoT & Connectivity | Equipment communication and data sharing | Real-time monitoring of experiments, equipment integration, remote lab management |

| Cloud Computing & Data Management | Secure data storage, management, and collaboration | Centralized data repositories, multi-site collaboration, data sharing and version control |

| Advanced Analytics & Visualization | Data interpretation and trend identification | Workflow optimization, experimental insight generation, research impact assessment |

Implementation Framework: From Manual to Automated Synthesis

Transitioning to a Lab of the Future requires a strategic approach that addresses technical, operational, and cultural dimensions. Research indicates that laboratories evolve along a digital maturity curve—from basic, fragmented digital systems toward fully integrated, automated, and predictive environments [6].

Assessing Digital Maturity Levels

According to a recent survey of biopharma R&D executives, laboratories fall into six distinct maturity levels [6]:

- Digitally Siloed (31%): Reliance on multiple electronic lab notebooks and laboratory information management systems with limited integration or automation

- Connected (34%): Data centralized and partially integrated with some automated lab processes in place

- Predictive (11%): Seamless integration between wet and dry lab environments where AI, digital twins, and automation work together

Notably, only 11% of organizations have achieved a fully predictive lab environment where AI, automation, digital twins, and well-integrated data seamlessly inform research decisions [6]. This progression represents more than just technological upgrades; it signals a fundamental shift in how scientific research is conducted [6].

Strategic Implementation Roadmap

Successful implementation begins with establishing a comprehensive lab modernization roadmap aligned with broader R&D strategy [6]. This involves:

Developing a Clear Vision: Translating strategic objectives into a detailed roadmap that links investments and capabilities to defined outcomes, delivering both short-term gains and long-term transformational value [6]

Building Robust Data Foundations: Implementing connected instruments that link laboratory devices to enable seamless, automated data transfer into centralized cloud platforms [6]. This includes developing flexible, modular architecture that supports storage and management of various data modalities (structured, unstructured, image, and omics data) [6]

Creating Research Data Products: Converting raw data into curated, reusable research data products that adhere to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to accelerate scientific insight generation [6]

Focusing on Operational Excellence: Establishing clear success measures tied to quantitative metrics or KPIs such as reduced cycle times, improved portfolio decision-making, and fewer failed experiments [6]

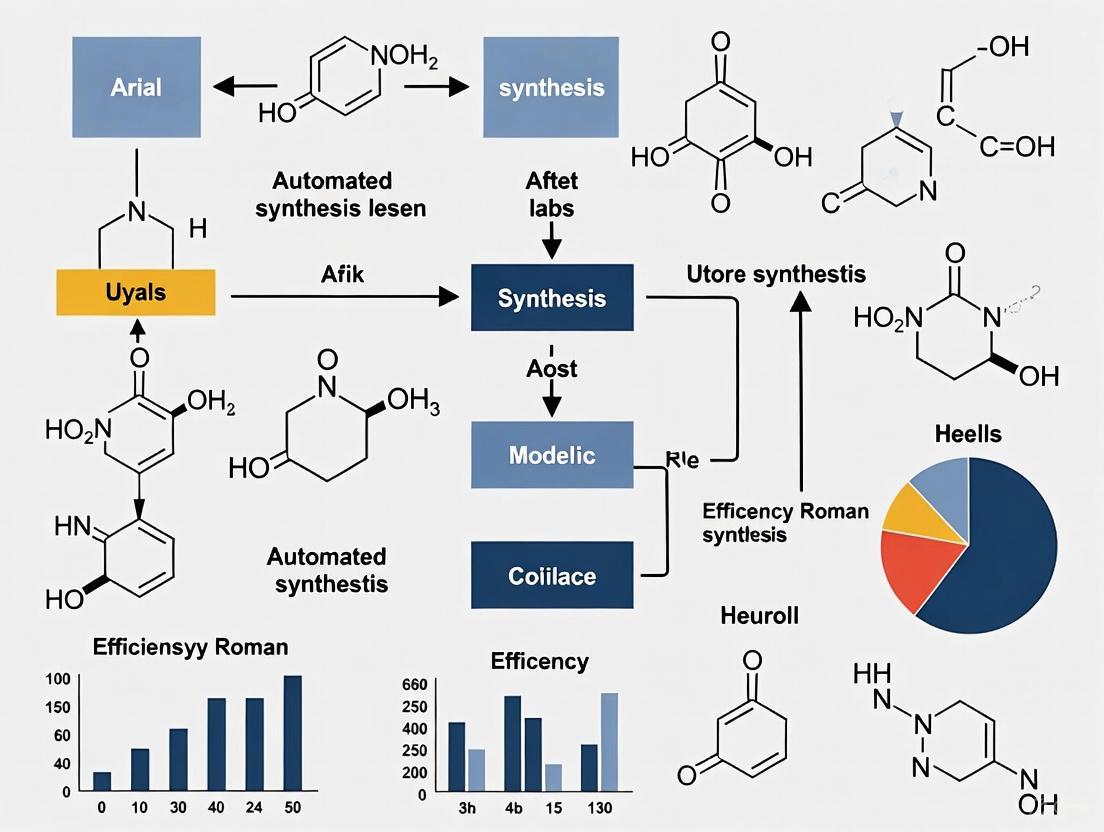

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow of a modern, data-driven laboratory, highlighting the continuous feedback loop between physical and digital research activities:

Experimental Protocol for Automated Synthesis

Implementing automated synthesis in academic research requires both technological infrastructure and methodological adjustments. The following protocol outlines a generalized approach that can be adapted to specific research domains:

Protocol: Implementation of Automated Synthesis Workflow

Workflow Analysis and Optimization

- Map existing experimental processes to identify bottlenecks and automation opportunities

- Define standardized operating procedures for repetitive tasks

- Establish quality control checkpoints and validation metrics

Instrument Integration and Connectivity

- Implement IoT-enabled smart instruments with automated data capture capabilities

- Establish laboratory information management system (LIMS) to centralize experimental data

- Configure application programming interfaces (APIs) for seamless data flow between instruments and data repositories

Automated Experiment Execution

- Program robotic systems for routine sample preparation and handling

- Implement automated synthesis platforms with predefined reaction parameters

- Configure real-time monitoring systems for reaction progress tracking

Data Management and Curation

- Establish automated data pipelines from instruments to centralized databases

- Implement metadata standards following FAIR principles

- Create curated research data products for specific research needs

Analysis and Iteration

- Apply machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition in experimental results

- Utilize predictive modeling to optimize subsequent experiment parameters

- Implement continuous improvement cycles based on accumulated data

This methodological framework enables the creation of a closed-loop research system where physical experiments inform computational models, which in turn guide subsequent experimental designs—dramatically accelerating the pace of discovery [1] [6].

Quantitative Benefits and Performance Metrics

The transformation to automated, data-driven laboratories delivers measurable improvements across multiple dimensions of research performance. According to a Deloitte survey of biopharma R&D executives, organizations implementing lab modernization initiatives report significant operational benefits [6]:

Table 2: Measured Benefits of Laboratory Modernization Initiatives

| Performance Metric | Improvement Reported | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Throughput | 53% of organizations reported increases | Deloitte Survey (2025) [6] |

| Reduction in Human Error | 45% of organizations reported reductions | Deloitte Survey (2025) [6] |

| Cost Efficiencies | 30% of organizations achieved greater efficiencies | Deloitte Survey (2025) [6] |

| Therapy Discovery Pace | 27% noted faster discovery | Deloitte Survey (2025) [6] |

| Sample Processing Speed | >50% increase in specific applications | Animal Health Startup Case Study [1] |

| Error Reduction | 60% reduction in human errors in sample intake | Animal Health Startup Case Study [1] |

Beyond these immediate operational benefits, laboratory modernization contributes to broader research impacts. Survey data indicates that more than 70% of respondents who reported reduced late-stage failure rates and increased Investigational New Drug (IND) approvals attributed these outcomes to lab-of-the-future investments guided by a clear strategic roadmap [6]. Nearly 60% of surveyed R&D executives expect these investments to result in an increase in IND approvals and a faster pace of drug discovery over the next two to three years [6].

The implementation of automation also creates important secondary benefits by freeing researchers from repetitive tasks. With routine tasks streamlined, personnel can dedicate more attention to higher-value activities such as experimental design, data interpretation, and collaborative problem-solving [2]. This shift in focus from manual operations to intellectual engagement represents a fundamental enhancement of the research process itself.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

The transition to automated synthesis environments requires specialized reagents and materials designed for compatibility with robotic systems and high-throughput workflows. The following toolkit outlines essential solutions for modern research laboratories:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Function | Automation-Compatible Features |

|---|---|---|

| Prefilled Reagent Plates | Standardized reaction components | Barcoded, pre-aliquoted in plate formats compatible with automated liquid handlers |

| Lyophilized Reaction Masters | Stable, ready-to-use reaction mixtures | Long shelf life, reduced storage requirements, minimal preparation steps |

| QC-Verified Chemical Libraries | Diverse compound collections for screening | Standardized concentration formats, predefined quality control data, barcoded tracking |

| Smart Consumables with Embedded RFID | Reagent containers with tracking capability | Automated inventory management, usage monitoring, and expiration tracking |

| Standardized Buffer Systems | Consistent reaction environments | Pre-formulated, pH-adjusted, filtered solutions with documented compatibility data |

These specialized reagents and materials are critical for ensuring reproducibility, traceability, and efficiency in automated research environments. By incorporating standardized, quality-controlled reagents designed specifically for automated platforms, laboratories can minimize variability and maximize the reliability of experimental results.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

The transformative impact of laboratory modernization is evident across multiple research sectors, from academic institutions to pharmaceutical companies. These real-world implementations demonstrate the practical benefits and challenges of transitioning to data-driven research environments.

Academic Research Transformation

Professor Alán Aspuru-Guzik at the University of Toronto and colleagues developed a "self-driving laboratory" where AI controls automated synthesis and validation in a cycle of machine-learning data analysis [1]. Meanwhile, Andrew I. Cooper and his team at the Materials Innovation Factory (University of Liverpool) published results from an AI-directed robotics lab that optimized a photocatalytic process for generating hydrogen from water after running about 700 experiments in just 8 days [1]. In a recent advancement reported in November 2024, Cooper's team at Liverpool developed 1.75-meter-tall mobile robots that use AI logic to make decisions and perform exploratory chemistry research tasks to the same level as humans, but much faster [1]. These academic examples demonstrate how the Lab of the Future is democratizing access to advanced research capabilities, potentially accelerating the pace of scientific discovery across disciplines.

Pharmaceutical Industry Implementation

Eli Lilly's Autonomous Lab debuted a self-driving lab at its biotechnology center in San Diego, representing the culmination of a 6-year project [1]. This facility includes over 100 instruments and storage for more than 5 million compounds. The Life Sciences Studio puts the company's expertise in chemistry, in vitro biology, sample management, and analytical data acquisition in a closed loop where AI controls robots that researchers can access via the cloud [1]. James P. Beck, the head of medicinal chemistry at the center, notes that "The lab of the future is here today," though he acknowledges that closing the loop requires addressing "a multifactorial challenge involving science, hardware, software, and engineering" [1].

Small Research Organization Success

A Bay Area-based animal health startup implemented automation in their sample intake processes, resulting in a 60% reduction in human errors and over a 50% increase in sample processing speed [1]. Their use of QR code-based logging enabled automated accessioning and seamless linking of samples to specific experiments, eliminating manual errors and ultimately leading to more accurate research outcomes [1]. As one lab technician explained: "Managing around 350 samples a week is no small task. By integrating with our database, we automated bulk sample intake and metadata updates, saving time and enhancing data accuracy by eliminating manual data entry" [1].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture of a self-driving laboratory system, showing how these various components integrate to create a continuous research cycle:

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

As laboratory technologies continue to evolve, several emerging trends are poised to further transform research practices and capabilities in the coming years.

The Shift to Data-Centric Ecosystems

One of the most significant transformations will be the pivot from electronic lab notebook (ELN)-centric workflows to data-centric ecosystems [1]. This represents more than digitizing paper processes—it's a fundamental rethinking of how scientific data flows through organizations. As Dr. Hans Bitter from Takeda noted, organizations need to embrace standardization that enables end-to-end digitalization across the R&D lifecycle to generate predictive knowledge across functions and stages [1]. This approach will dramatically improve speed, agility, quality, and R&D efficiency through "right-first-time" experimentation.

Advanced AI Integration and Cognitive Systems

Laboratories will increasingly deploy cognitive systems capable of autonomous decision-making and experimental design [1]. These systems will leverage multiple AI approaches, including:

- Generative AI for molecular design and hypothesis generation

- Reinforcement learning for iterative experimental optimization

- Causal AI for understanding underlying mechanisms and relationships

- Explainable AI (XAI) to provide transparent reasoning for AI-derived insights [5]

As these technologies mature, we can expect a shift from AI as a tool for analysis to AI as an active research partner capable of designing and executing complex research strategies.

Enhanced Connectivity and Remote Operation

The rise of remote and virtual laboratories is making laboratory access more flexible and widespread [3]. Virtual labs utilize cloud-based platforms to simulate experiments, allowing researchers to conduct studies without physical constraints, while remote labs enable collaboration across geographical boundaries, making it easier for scientists to share resources and expertise [3]. This trend is particularly impactful for educational institutions and research organizations with limited physical infrastructure, fostering global collaboration and innovation.

Sustainable Laboratory Practices

Sustainability is becoming an increasingly important focus for modern laboratories [2]. By purchasing energy-efficient equipment, reducing waste, and adopting greener processes, labs are implementing changes that align with environmental goals while offering long-term savings [2]. Automation contributes significantly to these sustainability efforts through optimized resource utilization, reduced reagent consumption, and minimized experimental repeats. The adoption of electronic laboratory notebooks and digital workflows has already demonstrated significant environmental benefits; according to recent statistics, the utilization of EHRs for 8.7 million patients has resulted in the saving of 1,044 tons of paper and avoided 92,000 tons of carbon emissions [2].

The modern "Lab of the Future" represents a fundamental paradigm shift from manual processes to integrated, data-driven research ecosystems. By leveraging technologies including automation, artificial intelligence, advanced data management, and connectivity, these transformed research environments deliver measurable improvements in efficiency, reproducibility, and discovery acceleration. For academic research laboratories, the adoption of automated synthesis methodologies offers particular promise for enhancing research productivity while maintaining scientific rigor.

The transformation journey requires careful planning and strategic implementation, beginning with a clear assessment of current capabilities and a roadmap aligned with research objectives. Success depends not only on technological adoption but also on developing robust data governance practices, fostering cultural acceptance, and continuously evaluating progress through relevant metrics.

As laboratory technologies continue to evolve, the most significant advances will likely come from integrated systems where physical and digital research components work in concert, creating continuous learning cycles that accelerate the pace of discovery. By embracing these transformative approaches, research organizations can position themselves at the forefront of scientific innovation, capable of addressing increasingly complex research challenges with unprecedented efficiency and insight.

The convergence of Robotics, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT) is fundamentally reshaping scientific research, particularly in academic labs focused on drug development. This transition from manual, discrete processes to integrated, intelligent systems enables an unprecedented paradigm of automated synthesis. By leveraging interconnected devices, autonomous robots, and AI-driven data analysis, research laboratories can achieve new levels of efficiency, reproducibility, and innovation. This whitepaper details the core technologies powering this shift, provides a quantitative analysis of the current landscape, and offers a practical framework for implementation to accelerate scientific discovery.

The traditional model of academic research, often characterized by labor-intensive protocols and standalone equipment, is rapidly evolving. The fusion of Robotics, AI, and IoT is creating a new infrastructure for scientific discovery. This integrated ecosystem, often termed the Internet of Robotic Things (IoRT) or AIoT (AI+IoT), allows intelligent devices to monitor the research environment, fuse sensor data from multiple sources, and use local and distributed intelligence to determine and execute the best course of action autonomously [7] [8]. In the context of drug development, this enables "automated synthesis"—where the entire workflow from chemical reaction setup and monitoring to purification and analysis can be orchestrated with minimal human intervention, enhancing speed, precision, and the ability to explore vast chemical spaces.

Core Technologies and Their Convergence

The Internet of Things (IoT) and Intelligent Connectivity

IoT forms the sensory and nervous system of the modern automated lab. It involves a network of physical devices—"things"—embedded with sensors, software, and other technologies to connect and exchange data with other devices and systems over the internet [8] [9].

- Intelligent Connectivity: In a research setting, this includes smart sensors monitoring reaction parameters (temperature, pH, pressure), networked analytical instruments, and connected actuators. These devices generate voluminous data that provides the raw material for actionable insights and informed decision-making [7].

- Edge Computing: To manage this data deluge and reduce latency, edge computing solutions process data closer to its source (e.g., in the lab) rather than sending it to a centralized cloud. This is critical for applications requiring real-time or near-real-time control and response, such as maintaining precise environmental conditions in a bioreactor [7].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning

AI acts as the brain of the automated lab, transforming raw data into intelligence and enabling predictive and autonomous capabilities.

- Machine Learning and Generative AI: Machine learning algorithms analyze historical and real-time experimental data to optimize reaction conditions, predict compound properties, and identify promising drug candidates [7]. Furthermore, Generative AI models can propose novel molecular structures with desired properties, vastly accelerating the initial discovery phase [9].

- AI Agents: A significant trend is the rise of AI agents—systems based on foundation models capable of planning and executing multi-step workflows autonomously [10]. In a lab context, an AI agent could plan a complex synthetic route and then orchestrate the robotic equipment to carry it out.

Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Robotics provides the mechanical means to interact with the physical world. The shift is from simple, pre-programmed automation to intelligent, adaptive systems.

- From Automation to Autonomy: Traditional robotics is characterized by repetitive, pre-programmed tasks. Next-generation systems integrate AI, machine vision, and advanced sensors to become adaptive, flexible, and capable of learning from their environment [11] [12].

- Collaborative Robots (Cobots) and Humanoids: Cobots are designed to work safely alongside human researchers, handling tedious or hazardous tasks like solvent dispensing or sample management [11]. The industry is also advancing towards humanoid robots, which are predicted to become significant in structured environments like labs for tasks that require manipulation of equipment designed for humans [12].

The Converged Ecosystem: IoRT and Digital Twins

The true power emerges from the integration of these technologies. The Internet of Robotic Things (IoRT) is a paradigm where collaborative robotic things can communicate, learn autonomously, and interact safely with the environment, humans, and other devices to perform tasks efficiently [8].

A key enabling technology is the Digital Twin—a virtual replica of a physical lab, process, or robot. Over 90% of the robotics industry is now using or piloting digital twins [12]. Researchers can use a digital twin to simulate and optimize an entire experimental protocol—testing thousands of variables and identifying potential failures—before deploying the validated instructions to the physical robotic system. This saves immense time and resources and serves as a crucial safety net for high-stakes research [12].

Quantitative Analysis of Technology Adoption and Impact

The adoption of these core technologies is accelerating across industries, including life sciences. The following tables summarize key quantitative data that illustrates current trends, adoption phases, and perceived benefits.

Table 1: Organizational Adoption Phase of Core Technologies (2025)

| Technology | Experimenting/Piloting Phase | Scaling Phase | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative AI | ~65% [10] | ~33% [10] | Innovation, operational efficiency [10] |

| AI Agents | 39% [10] | 23% (in 1-2 functions) [10] | Automation of complex, multi-step workflows |

| Robotics | Data Not Available | Data Not Available | Labor shortages, precision, safety [13] [11] |

| Digital Twins | 51.7% [12] | 39.4% [12] | De-risking development, optimizing performance |

Table 2: Impact and Perceived Benefits of AI Adoption

| Impact Metric | Reported Outcome | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Enterprise-level EBIT Impact | 39% of organizations report any impact [10] | Majority of impact remains at use-case level [10] |

| Catalyst for Innovation | 64% of organizations [10] | AI enables new approaches and services |

| Cost Reduction | Most common in software engineering, manufacturing, IT [10] | Also applicable to lab operations and R&D |

| Revenue/Progress Increase | Most common in marketing, sales, product development [10] | In research, translates to faster discovery cycles |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Automated Synthesis Workflow

This section outlines a detailed methodology for deploying a converged Robotics, AI, and IoT system for automated chemical synthesis.

Protocol Objective

To autonomously synthesize a target small molecule library, leveraging an IoRT framework for execution and a digital twin for simulation and optimization.

Materials and Equipment (The Scientist's Toolkit)

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials for Automated Synthesis

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Modular Robotic Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses microliter-to-milliliter volumes of reagents and solvents; the core actuator for synthesis. |

| IoT-Enabled Reactor Block | A reaction vessel with integrated sensors for real-time monitoring of temperature, pressure, and pH. |

| AI-Driven Spectral Analyzer | An instrument (e.g., HPLC-MS, NMR) connected to the network for automated analysis of reaction outcomes. |

| Digital Twin Software Platform | A virtual environment to simulate and validate the entire robotic synthesis workflow before physical execution. |

| AI/ML Model (e.g., Generative Chemistry) | Software to propose novel synthetic routes or optimize existing ones based on chemical knowledge graphs and data. |

| Centralized Data Lake | A secure repository for all structured and unstructured data generated by IoT sensors, robots, and analyzers. |

Detailed Methodology

Workflow Digitalization and Simulation:

- Define the target molecule and all potential synthetic pathways.

- Develop a digital twin of the entire process in the simulation platform. This includes virtual models of the robotic arms, liquid handlers, and reactors.

- Simulate the workflow to identify optimal reagent addition sequences, mixing speeds, and temperature ramps. The system flags potential physical bottlenecks or instrument conflicts.

AI-Guided Route Optimization:

- Input the target molecule and available starting materials into the generative chemistry AI.

- The AI model proposes and ranks several synthetic routes based on predicted yield, step count, and cost.

- The highest-ranked route is selected and fed into the digital twin for final validation.

Physical Execution via IoRT:

- The validated protocol is deployed to the physical lab equipment.

- The robotic liquid handler prepares reagents and sets up reactions in the IoT-enabled reactors.

- IoT sensors continuously stream environmental data back to the central control system.

Real-Time Monitoring and Adaptive Control:

- The AI agent monitors the incoming sensor data.

- Using pre-defined rules or machine learning models, the system detects deviations from the expected parameters (e.g., an exothermic spike) and makes micro-adjustments (e.g., modulating coolant flow) to maintain the trajectory towards the desired product.

Automated Analysis and Iteration:

- Upon completion, an automated sampler injects a aliquot from the reaction mixture into the spectral analyzer.

- The analysis results (e.g., purity, yield) are automatically fed back into the central data lake.

- This data is used to update the AI models, closing the loop and continuously improving the system's performance for future synthesis.

System Architecture and Workflow Visualization

The logical flow of information and control in an automated synthesis lab is illustrated below. This diagram depicts the continuous cycle from virtual design to physical execution and learning.

Automated Synthesis System Flow. This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow where the virtual layer (AI, Digital Twin) designs and validates a protocol. The validated instructions are sent to the physical layer (Robotics, IoT) for execution. IoT sensors continuously stream data back to a central data repository, which is used to update and refine the AI models, creating a closed-loop, self-improving system.

The synthesis of Robotics, AI, and IoT is not a future prospect but a present-day enabler of transformative research. For academic labs and drug development professionals, embracing this integrated approach through automated synthesis platforms is key to tackling more complex scientific challenges, enhancing reproducibility, and accelerating the pace of discovery. While implementation requires strategic investment and cross-disciplinary expertise, the potential returns—in terms of scientific insight, operational efficiency, and competitive advantage—are substantial. The future of research lies in intelligent, connected, and autonomous systems that empower scientists to explore further and faster.

The Rise of Self-Driving Labs (SDLs) and Autonomous Experimentation

Self-Driving Labs (SDLs) represent a transformative paradigm in scientific research, automating the entire experimental process from hypothesis generation to execution and analysis. These labs integrate robotic systems, artificial intelligence (AI), and data science to autonomously perform experiments based on pre-defined protocols, significantly accelerating the pace of discovery while reducing human error and material costs [14]. In the context of academic research, particularly in fields like drug discovery and materials science, SDLs address growing challenges posed by complex global problems that require more rigorous, efficient, and collaborative approaches to experimentation [15].

The primary difference between established high-throughput laboratories and SDLs lies in the judicious selection of experiments, adaptation of experimental methods, and development of workflows that can integrate the operation of multiple tools [15]. This automation of experimental design provides the leverage for expert knowledge to efficiently tackle increasingly complex, multivariate design spaces required by modern scientific problems. By acting as highly capable collaborators in the research process, SDLs serve as nexuses for collaboration and inclusion in the sciences—helping coordinate and optimize grand research efforts while reducing physical and technical obstacles of performing research manually [15].

Core Principles and Technical Architecture

Defining Characteristics of SDLs

Self-Driving Labs typically comprise two core components: a suite of digital tools to make predictions, propose experiments, and update beliefs between experimental campaigns, and a suite of automated hardware to carry out experiments in the physical world [15]. These components work jointly toward human-defined objectives such as process optimization, material property optimization, compound discovery, or self-improvement.

The fundamental shift SDLs enable is the transition from traditional, often manual experimentation to a continuous, closed-loop operation where each experiment informs the next without human intervention. This creates a virtuous cycle of learning and discovery that dramatically compresses research timelines. Unlike traditional high-throughput approaches that merely scale up experimentation, SDLs implement intelligent experiment selection to maximize knowledge gain while minimizing resource consumption [15].

Technical Architecture and Workflow

The technical architecture of a comprehensive SDL system involves multiple integrated layers that work in concert to enable autonomous experimentation. The Artificial platform exemplifies this architecture with its orchestration engine that automates workflow planning, scheduling, and data consolidation [14].

Table: Core Components of an SDL Orchestration Platform

| Component | Function | Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Web Apps | User-facing interfaces for lab management | Digital twin, workflow managers, lab operations hub |

| Services | Backend computational power | Orchestration, scheduling, data records |

| Lab API | Connectivity layer | GraphQL, gRPC, REST protocols |

| Adapters | Communication protocols | HTTPS, gRPC, SiLA, local APIs |

| Informatics | Integration with lab systems | LIMS, ELN, data lakes |

| Automation | Hardware interface | Instrument drivers, schedulers |

The workflow within an SDL follows a structured pipeline that can be visualized as follows:

This workflow demonstrates the closed-loop nature of SDLs, where each experiment informs subsequent iterations through AI model updates, creating a continuous learning system that rapidly converges toward research objectives.

Key Implementation Frameworks and Platforms

Whole-Lab Orchestration Systems

Modern SDL platforms like Artificial provide comprehensive orchestration and scheduling systems that unify lab operations, automate workflows, and integrate AI-driven decision-making [14]. These platforms address critical challenges in orchestrating complex workflows, integrating diverse instruments and AI models, and managing data efficiently. By incorporating AI/ML models like NVIDIA BioNeMo—which facilitates molecular interaction prediction and biomolecular analysis—such platforms enhance drug discovery and accelerate data-driven research [14].

The Artificial platform specifically enables real-time coordination of instruments, robots, and personnel through its orchestration engine that handles planning and request management for lab operations using a simplified dialect of Python or a graphical interface [14]. This approach streamlines experiments, enhances reproducibility, and advances discovery timelines by eliminating manual intervention bottlenecks.

Specialized SDL Platforms for Drug Discovery

In drug discovery, specialized SDL platforms like ChemASAP (Automated Synthesis and Analysis Platform for Chemistry) have been developed to build fully automated systems for chemical reaction processes focused on producing and repurposing therapeutics [16]. These platforms utilize the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle—a hypothesis-driven framework aimed at optimizing compound design and performance through iterative improvement.

The ChemASAP platform integrates advanced tools for miniaturization and parallelization of chemical reactions, accelerating experiments by a factor of 100 compared to manual synthesis [16]. This dramatic acceleration is achieved through a digital infrastructure built over many years to generate and reuse machine-readable processes and data, representing an investment of over €4 million, highlighting the significant but potentially transformative resource commitment required for SDL implementation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The DMTA Cycle in Practice

The core experimental framework driving many SDLs in drug discovery is the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle [16]. This iterative process forms the backbone of autonomous experimentation for molecular discovery:

Design Phase: AI models propose new candidate compounds or materials based on previous experimental results and molecular property predictions. For example, models might suggest molecular structures with optimized binding affinity or specified physical properties.

Make Phase: Automated synthesis systems physically create the designed compounds. The ChemASAP platform, for instance, utilizes automated chemical synthesis workflows to execute this step without human intervention [16].

Test Phase: Robotic systems characterize the synthesized compounds for target properties—such as biological activity, solubility, or stability—using high-throughput screening assays and analytical instruments.

Analyze Phase: AI algorithms process the experimental data, extract meaningful patterns, update predictive models, and inform the next design cycle, closing the autonomous loop.

This methodology creates a continuous learning system where each iteration enhances the AI's understanding of structure-property relationships, progressively leading to more optimal compounds.

Virtual Screening Workflows

SDLs increasingly integrate in silico methodologies with physical experimentation. Virtual screening allows researchers to rapidly evaluate large libraries of chemical compounds computationally, prioritizing only the most promising candidates for physical synthesis and testing [14]. This hybrid approach significantly reduces material costs and experimental timelines.

The experimental protocol for integrated virtual and physical screening typically involves:

- Molecular Library Preparation: Curating and preparing extensive virtual compound libraries.

- AI-Prioritization: Using AI models like NVIDIA BioNeMo to predict molecular properties, interactions, and potential efficacy.

- Synthesis Prioritization: Selecting top candidates from virtual screening for physical synthesis.

- Experimental Validation: Automating the synthesis and testing of prioritized compounds.

- Model Refinement: Using experimental results to refine AI models for improved future predictions.

This workflow demonstrates how SDLs effectively bridge computational and experimental domains, leveraging the strengths of each to accelerate discovery.

Quantitative Benefits and Performance Metrics

Accelerated Discovery Timelines

The implementation of SDLs has demonstrated substantial reductions in discovery timelines across multiple domains. The following table summarizes key performance metrics reported from various SDL implementations:

Table: SDL Performance Metrics and Acceleration Factors

| Application Domain | Reported Acceleration | Key Metrics | Source Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Synthesis | 100x faster than manual synthesis | Experimental screening cycles | ChemASAP [16] |

| Material Discovery | Thousands of experiments autonomously | Energy absorption efficiency discovered | BEAR DEN [17] |

| Drug Discovery | Reduced R&D costs and failure rates | Automated DMTA cycles | Artificial Platform [14] |

| Polymer Research | Rapid parameter optimization | Thin film fabrication | BEAR DEN [17] |

These metrics highlight the transformative efficiency gains possible through SDL implementation. For example, the Bayesian experimental autonomous researcher (BEAR) system at Boston University combined additive manufacturing, robotics, and machine learning to conduct thousands of experiments, discovering the most efficient material ever for absorbing energy—a process that would have been prohibitively time-consuming using traditional methods [17].

Enhanced Reproducibility and Data Quality

Beyond acceleration, SDLs provide significant improvements in experimental reproducibility and data quality. As noted by researchers, "You see robots, you see software—it's all in the service of reproducibility" [17]. The standardized processes and automated execution in SDLs eliminate variability introduced by human operators, ensuring that experiments can be faithfully replicated.

This enhanced reproducibility is particularly valuable in academic research where replication of results is fundamental to scientific progress. Furthermore, the comprehensive data capture inherent to SDLs creates rich, structured datasets that facilitate meta-analyses and secondary discoveries beyond the original research objectives.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The effective operation of Self-Driving Labs requires both physical components and digital infrastructure. The following table details key resources and their functions within SDL ecosystems:

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDL Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in SDL |

|---|---|---|

| Orchestration Software | Artificial Platform, Chemspyd, PyLabRobot | Manages workflow planning, scheduling, and integration of lab components [14] [15] |

| AI/ML Models | NVIDIA BioNeMo, Custom Bayesian Optimization | Predicts molecular properties, optimizes experimental design, analyzes results [17] [14] |

| Automation Hardware | Robotic liquid handlers, automated synthesizers | Executes physical experimental steps without human intervention [15] [16] |

| Data Management Systems | LIMS, ELN, Digital Twin platforms | Tracks experiments, manages data provenance, enables simulation [14] |

| Modular Chemistry Tools | PerQueue, Jubilee, Open-source tools | Facilitates protocol standardization and method transfer between systems [15] |

These resources form the foundational infrastructure that enables SDLs to operate autonomously. The integration across categories is crucial—for instance, AI models must seamlessly interface with both data management systems and automation hardware to create closed-loop experimentation.

Implementation Roadmap for Academic Labs

Deployment Models for Academic Research

Academic institutions can leverage different SDL deployment models, each with distinct advantages and challenges. The centralized approach creates shared facilities that provide access to multiple research groups, concentrating expertise and resources [15]. Conversely, distributed approaches establish specialized platforms across different research groups, enabling customization and niche applications.

A hybrid model may be particularly suitable for academic environments, where individual laboratories develop and test workflows using simplified automation before submitting finalized protocols to a centralized facility for execution [15]. This approach balances the flexibility of distributed development with the efficiency of centralized operation.

The implementation considerations for academic SDLs can be visualized as follows:

Addressing Implementation Challenges

Successful SDL implementation requires addressing several critical challenges. Data silos—discrete sets of isolated data—hinder AI performance by limiting training data availability [14]. Strategic initiatives for data sharing and standardized formats are essential to overcome this limitation.

Additionally, integrating AI models with diverse and often noisy experimental data requires robust computational pipelines capable of handling complex workflows, standardizing data preprocessing, and maintaining reproducibility [14]. Without such infrastructure, AI-driven insights may suffer from inconsistencies, reducing their reliability.

Finally, workforce development is crucial, as SDLs require interdisciplinary teams combining domain expertise with skills in automation, data science, and AI. Academic institutions must adapt training programs to prepare researchers for this evolving research paradigm.

Self-Driving Labs represent a fundamental shift in how scientific research is conducted, moving from manual, discrete experiments to automated, continuous discovery processes. For academic research labs, SDLs offer the potential to dramatically accelerate discovery timelines, enhance reproducibility, and tackle increasingly complex research questions that defy traditional approaches.

The ongoing development of platforms like Artificial and ChemASAP demonstrates the practical feasibility of SDLs across multiple domains, from drug discovery to materials science [14] [16]. As these technologies mature and become more accessible through centralized facilities, distributed networks, or hybrid models, they promise to democratize access to advanced experimentation capabilities.

The future of SDLs will likely involve greater human-machine collaboration, where researchers focus on high-level experimental design and interpretation while automated systems handle routine execution and data processing. This paradigm shift has the potential to not only accelerate individual research projects but to transform the entire scientific enterprise into a more efficient, collaborative, and impactful endeavor.

For academic labs willing to make the substantial initial investment in SDL infrastructure, the benefits include increased research throughput, enhanced competitiveness for funding, and the ability to address grand challenges that require scale and complexity beyond traditional experimental approaches. As the technology continues to advance, SDLs are poised to become essential tools in the academic research landscape, ultimately accelerating the translation of scientific discovery into practical applications that address pressing global needs.

The integration of automated synthesis platforms represents a fundamental transformation in academic and industrial research methodology, bridging the critical gap between computational discovery and experimental realization. This paradigm shift is redefining the very nature of scientific investigation across chemistry, materials science, and drug development by introducing unprecedented levels of efficiency, data integrity, and researcher safety. The transition from traditional manual methods to automated, data-driven workflows addresses long-standing bottlenecks in research productivity while simultaneously elevating scientific standards through enhanced reproducibility and systematic experimentation.

The emergence of facilities like the Centre for Rapid Online Analysis of Reactions (ROAR) at Imperial College London exemplifies this transformation, providing academic researchers with access to high-throughput robotic platforms previously available only in industrial settings [18]. Similarly, groundbreaking initiatives such as the A-Lab for autonomous materials synthesis demonstrate how the fusion of robotics, artificial intelligence, and computational planning can accelerate the discovery of novel inorganic compounds at unprecedented scales [19]. These platforms are not merely automating existing processes but are enabling entirely new research approaches that leverage massive, high-quality datasets for machine learning and predictive modeling.

Efficiency: Accelerating the Research Lifecycle

Automated synthesis platforms deliver dramatic efficiency improvements by significantly reducing experimental timelines and eliminating manual bottlenecks throughout the research lifecycle. This acceleration manifests across multiple dimensions of the experimental process, from initial discovery to optimization and validation.

High-Throughput Experimentation

The core efficiency advantage of automation lies in its capacity for highly parallel experimentation. Traditional "one-at-a-time" manual synthesis has been a fundamental constraint on research progress, particularly in fields requiring extensive condition screening. Automated systems transcend this limitation by enabling the simultaneous execution of numerous experiments. For instance, the robotic platforms at ROAR can dispense reagents into racks carrying up to ninety-six 1 mL vials, enabling researchers to explore vast parameter spaces in a single experimental run [18]. This parallelization directly translates to dramatic time savings, with studies indicating that AI-powered literature review tools alone can reduce review time by up to 70% [20].

The economic impact of this acceleration is substantial, particularly when considering the opportunity cost of researcher time. By automating repetitive tasks like reagent dispensing, mixing, and reaction monitoring, these systems free highly trained scientists to focus on higher-value cognitive work such as experimental design, data interpretation, and hypothesis generation.

Table 1: Efficiency Gains Through Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Efficiency Metric | Traditional Approach | Automated Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Setup Time | 15-30 minutes per reaction | Simultaneous setup for 96 reactions | ~50-100x faster |

| Literature Review | Days to weeks | Hours to days | Up to 70% reduction [20] |

| Data Extraction & Documentation | Manual, error-prone | Automated, systematic | Near-instantaneous |

| Reaction Optimization | Sequential iterations | Parallel condition screening | Weeks reduced to days |

Continuous Operation and Resource Optimization

Beyond parallelization, automated systems provide continuous operational capability unaffected by human constraints such as fatigue, scheduling limitations, or the need for repetitive task breaks. The A-Lab exemplified this capacity by operating continuously for 17 days, successfully realizing 41 novel compounds from a set of 58 targets during this period [19]. This uninterrupted operation enables research progress at a pace impossible to maintain with manual techniques.

These systems also achieve significant resource optimization through miniaturization and precision handling. By operating at smaller scales with exact control over quantities, automated platforms reduce reagent consumption and waste generation. As ROAR's director notes, "We've spent a decade miniaturizing high-throughput batch chemistry so we can run more combinations with similar amounts of material" [18]. This miniaturization is particularly valuable when working with expensive, rare, or hazardous compounds where traditional trial-and-error approaches would be prohibitively costly.

Diagram 1: Automated Synthesis Workflow

Data Quality: The Foundation for Reproducible, Data-Driven Science

Automated synthesis platforms fundamentally enhance scientific data quality by ensuring systematic data capture, standardized execution, and comprehensive documentation. This rigorous approach to data generation addresses critical shortcomings in traditional experimental practices that have long hampered reproducibility and meta-analysis in scientific research.

Standardization and Reproducibility

The reproducibility crisis affecting many scientific disciplines stems partly from inconsistent experimental execution and incomplete methodological reporting. Automated systems overcome these limitations through precise control of reaction parameters and systematic recording of all experimental conditions. As Benjamin J. Deadman, ROAR's facility manager, notes: "Synthetic chemists in academic labs are not collecting the right data and not reporting it in the right way" [18]. Automation addresses this directly by capturing comprehensive metadata including exact temperatures, timings, environmental conditions, and reagent quantities that human researchers might omit or estimate inconsistently.

This standardized approach enables true experimental reproducibility both within and across research groups. By encoding protocols in executable formats rather than natural language descriptions, automated systems eliminate interpretation variances that can alter experimental outcomes. The resulting consistency is particularly valuable for multi-institutional collaborations and long-term research projects where personnel changes might otherwise introduce methodological drift.

Data Structure and Machine Readability

Beyond standardization, automated platforms generate data in structured, machine-readable formats suitable for computational analysis and machine learning applications. This represents a critical advancement over traditional lab notebooks and published procedures, which typically present information in unstructured natural language formats. As emphasized in research on self-driving labs, "the vast majority of the knowledge that has been generated over the past centuries is only available in the form of unstructured natural language in books or scientific publications rather than in structured, machine-readable and readily interoperable data" [21].

The A-Lab exemplifies this structured approach by using probabilistic machine learning models to extract phase and weight fractions from X-ray diffraction patterns, with automated Rietveld refinement confirming identified phases [19]. This end-to-end structured data pipeline enables the application of sophisticated data science techniques and creates what the A-Lab researchers describe as "actionable suggestions to improve current techniques for materials screening and synthesis design" [19].

Table 2: Data Quality Dimensions Enhanced by Automation

| Data Quality Dimension | Traditional Limitations | Automated Solutions | Downstream Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness | Selective recording of "successful" conditions; missing metadata | Comprehensive parameter logging; full experimental context | Enables robust meta-analysis; eliminates publication bias |

| Precision | Subjective measurements; estimated quantities | High-precision instrumentation; exact digital records | Reduces experimental noise; enhances statistical power |

| Structure | Unstructured narratives; inconsistent formatting | Standardized schemas; machine-readable formats | Facilitates data mining; enables machine learning |

| Traceability | Manual transcription errors; incomplete provenance | Automated data lineage; sample tracking | Ensures reproducibility; supports regulatory compliance |

Active Learning and Optimization

A particularly powerful aspect of automated synthesis platforms is their capacity for closed-loop optimization through active learning algorithms. These systems can autonomously interpret experimental outcomes and propose improved follow-up experiments, dramatically accelerating the optimization process. The A-Lab employed this approach through its Autonomous Reaction Route Optimization with Solid-State Synthesis (ARROWS3) algorithm, which "integrates ab initio computed reaction energies with observed synthesis outcomes to predict solid-state reaction pathways" [19].

This active learning capability enabled the A-Lab to successfully synthesize six targets that had zero yield from initial literature-inspired recipes [19]. The system continuously built a database of pairwise reactions observed in experiments—identifying 88 unique pairwise reactions—which allowed it to eliminate redundant experimental pathways and focus on promising synthetic routes [19]. This knowledge-driven approach to experimentation represents a fundamental advance over simple brute-force screening.

Diagram 2: Active Learning Optimization Cycle

Safety: Protecting Researchers and Environments

Automated synthesis platforms provide substantial safety advantages by minimizing direct human exposure to hazardous materials and operations while implementing engineered safety controls at the system level. This protection is particularly valuable in research involving toxic, radioactive, or highly reactive substances where manual handling presents significant risks.

Hazard Mitigation Through Engineering Controls

The fundamental safety principle of automation is the substitution of hazardous manual operations with engineered controls. This approach is exemplified in automated radiosynthesis modules used for producing radiopharmaceuticals, which "reduce human error and radiation exposure for operators" [22]. By enclosing hazardous processes within controlled environments, these systems protect researchers from direct contact with dangerous substances while simultaneously providing more consistent safety outcomes than procedural controls and personal protective equipment alone.

This engineered approach to safety extends beyond radiation to encompass chemical hazards including toxic compounds, explosive materials, and atmospheric sensitivities. The A-Lab specifically handled "solid inorganic powders" which "often require milling to ensure good reactivity between precursors," a process that can generate airborne particulates when performed manually [19]. By automating such powder handling operations, the system mitigates inhalation risks while maintaining precise control over processing parameters.

Enhanced Process Control and Monitoring

Automated systems further enhance safety through continuous monitoring and precise parameter control that exceeds human capabilities. These platforms can integrate multiple sensor systems to track conditions in real-time and implement automatic responses to deviations that might precipitate hazardous situations. This constant vigilance is particularly valuable for reactions requiring strict control of temperature, pressure, or atmospheric conditions where human monitoring would be intermittent and potentially unreliable.

The comprehensive data logging capabilities of automated systems also contribute to safety by creating detailed records of process parameters and any deviations. This information supports thorough incident investigation and root cause analysis when anomalies occur, enabling continuous improvement of safety protocols. The ability to precisely replicate validated safe procedures further reduces the likelihood of operator errors that might lead to hazardous situations.

Implementation Guide: Integrating Automation into Research Workflows

Successfully integrating automated synthesis platforms into academic research environments requires careful consideration of both technical and human factors. The following guidelines draw from established facilities and emerging best practices in the field.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing automated synthesis requires both hardware infrastructure and specialized software tools that collectively enable autonomous experimentation. The table below details essential components of a modern automated synthesis toolkit.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function & Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature Synthesis AI | GPT-5, Llama-3.1, Custom transformers [23] [21] | Generates initial synthesis recipes using NLP trained on published procedures | Balance between performance and computational requirements; hosting options (cloud vs. local) |

| Active Learning Algorithms | ARROWS3, Bayesian optimization [19] | Proposes improved synthesis routes based on experimental outcomes | Integration with existing laboratory equipment; data format compatibility |

| Robotic Platforms | Unchained Labs, Custom-built systems [18] [19] | Automated dispensing, mixing, and transfer of reagents and samples | Compatibility with common laboratoryware; modularity for method development |

| Analysis & Characterization | XRD with ML analysis, Automated Rietveld refinement [19] | Real-time analysis of reaction products; phase identification | Data standardization; calibration requirements; sample preparation automation |

| Data Management | Custom APIs, Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) | Experimental tracking; data provenance; results communication | Interoperability standards; data security; backup protocols |

Experimental Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

The following detailed methodology outlines the protocol used by the A-Lab for autonomous materials synthesis, providing a template for implementing similar workflows in academic research settings [19]:

Target Identification and Validation:

- Identify target materials through computational screening (e.g., Materials Project, Google DeepMind databases)

- Apply air stability filters to exclude targets predicted to react with O₂, CO₂, or H₂O

- Verify that targets are new to the system (not in training data for recipe generation algorithms)

Initial Recipe Generation:

- Generate up to five initial synthesis recipes using natural language processing models trained on literature data

- Propose synthesis temperatures using ML models trained on heating data from literature

- Select precursors based on target "similarity" to known compounds with established syntheses

Automated Synthesis Execution:

- Employ automated powder dispensing and mixing stations for sample preparation

- Transfer samples to alumina crucibles using robotic arms

- Load crucibles into box furnaces for heating under programmed temperature profiles

- Allow samples to cool automatically before robotic transfer to characterization stations

Automated Product Characterization and Analysis:

- Grind samples into fine powders using automated grinding stations

- Acquire X-ray diffraction patterns using automated diffractometers

- Extract phase and weight fractions using probabilistic ML models trained on experimental structures

- Confirm phase identification through automated Rietveld refinement

Active Learning and Optimization:

- Report weight fractions to laboratory management system

- For targets with <50% yield, invoke active learning algorithm (ARROWS3) to design improved synthesis routes

- Consult database of pairwise reactions to eliminate redundant experimental pathways

- Prioritize intermediates with large driving forces to form target materials

- Continue iterative optimization until target is obtained as majority phase or all synthesis options exhausted

Addressing Implementation Challenges

Despite their significant benefits, automated synthesis platforms present implementation challenges that must be strategically addressed:

Skills Gap: Most PhD students in synthetic chemistry have little or no experience with automated synthesis technology [18]. Successful implementation requires comprehensive training programs that integrate automation into the chemistry curriculum.

Resource Allocation: High-throughput automated synthesis machines can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, making them potentially prohibitive for individual academic labs [18]. Centralized facilities like ROAR provide a cost-effective model for broader access [18].

Data Integration: Legacy data from traditional literature presents interoperability challenges due to unstructured formats and incomplete reporting [21]. Successful implementation requires structured data capture from the outset and potential retrofitting of historical data.

Workflow Re-engineering: Traditional research processes must be rethought to fully leverage automation capabilities. As ROAR's director emphasizes, "It's about changing the mind-set of the whole community" [18].

Automated synthesis platforms represent a transformative advancement in research methodology, offering dramatic improvements in efficiency, data quality, and safety. By integrating robotics, artificial intelligence, and computational planning, these systems enable research at scales and precision levels impossible to achieve through manual methods. The successful demonstration of autonomous laboratories like the A-Lab—synthesizing 41 novel compounds in 17 days of continuous operation—provides compelling evidence of this paradigm shift's potential [19].

As these technologies continue to evolve, their integration into academic research environments will likely become increasingly seamless and accessible. The emerging generation of chemists and materials scientists trained in these automated approaches will further accelerate this transition, ultimately making automated synthesis suites as ubiquitous in universities as NMR facilities are today [18]. This technological transformation promises not only to accelerate scientific discovery but to fundamentally enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and safety of chemical and materials research across academic and industrial settings.

The integration of automated synthesis technologies is fundamentally transforming academic research, enabling the rapid discovery of novel materials and chemical compounds. While the benefits are substantial—dramatically increased throughput, enhanced reproducibility, and liberation of researcher time for high-level analysis—widespread adoption faces significant hurdles. This technical guide examines the primary barriers of cost, training, and cultural resistance within academic settings. It provides a structured framework for overcoming these challenges, supported by quantitative data, real-world case studies, and actionable implementation protocols. By addressing these obstacles strategically, academic labs can harness the full potential of automation to accelerate the pace of scientific discovery.

The modern academic research laboratory stands on the brink of a revolution, driven by the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced data analytics. Often termed "Lab 4.0" or the "self-driving lab," this new paradigm represents a fundamental shift from manual, labor-intensive processes to automated, data-driven discovery [1]. The core value proposition for academic institutions is multifaceted: automation can significantly reduce experimental cycle times, minimize human error, and unlock the exploration of vastly larger experimental parameters than previously possible.

In fields from materials science to drug discovery, the impact is already being demonstrated. For instance, the A-Lab at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory successfully synthesized 41 novel inorganic compounds over 17 days of continuous operation—a task that would have taken human researchers months or years to complete [19]. Similarly, the application of AI in evidence synthesis for systematic literature reviews has demonstrated a reduction in workload of 55% to 75%, freeing up researchers for more critical analysis [24]. These advances are not merely about efficiency; they represent a fundamental enhancement of scientific capability, allowing researchers to tackle problems of previously intractable complexity. The following sections detail the specific barriers and provide a pragmatic roadmap for integration.

Quantifying the Barriers: Cost, Training, and Culture

A strategic approach to adopting automated synthesis requires a clear understanding of the primary obstacles. The following table summarizes the key challenges and their documented impacts.

Table 1: Key Adoption Barriers and Their Documented Impacts

| Barrier Category | Specific Challenges | Quantified Impact / Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Cost | High initial investment in robotics, automation systems, and software infrastructure [1]. | Creates significant entry barriers, particularly for smaller or less well-funded labs [1]. |

| Training & Expertise | Lack of personnel trained to work with AI and robotic systems; steep learning curve [1]. | Surveys indicate many organizations struggle with training, leaving engineers and researchers unprepared for the transition [1]. |

| Cultural Resistance | Skepticism toward new technologies; perception of limited creative freedom; preference for traditional manual methods [1]. | Lab personnel may perceive automation as limiting their autonomy, leading to resistance and slow adoption of new workflows [1]. |

| Implementation & Integration | Challenges in integrating new technologies with existing ("legacy") equipment and workflows [1]. | Compatibility issues can complicate implementation, creating technical debt and slowing down processes [1]. |

| Operational Efficiency | Time-consuming manual work in traditional synthesis and data analysis [25]. | 60.3% of researchers cite "time-consuming manual work" as their biggest pain point in research processes [25]. |

Strategic Solutions for Overcoming Barriers

Mitigating Financial Hurdles

The high initial cost of automation can be a formidable barrier. However, several strategies can make this investment more accessible:

- Pursue Open-Source and Affordable Platforms: The development of low-cost, open-source platforms is a game-changer for academia. For example, one research group has created an open and cost-effective autonomous electrochemical setup, providing all designs and software freely to democratize access to self-driving laboratories [26]. This approach can reduce capital expenditure by an order of magnitude compared to commercial alternatives.

- Phased Implementation and Modular Design: Instead of a complete lab overhaul, labs can adopt a phased approach. Start by automating a single, high-volume process (e.g., sample preparation or specific screening protocols) using modular systems that can be expanded over time [1] [27]. This spreads the cost over a longer period and allows for proof-of-concept validation.

- Highlight Long-Term ROI and Grant Potential: Emphasize the long-term return on investment through increased throughput, reduced reagent waste, and fewer experimental repeats [1]. The compelling data from early adopters (e.g., a 60% reduction in human errors and over 50% increase in processing speed [1]) can be leveraged in grant applications to secure dedicated funding for instrumentation.

Developing a Robust Training and Support Ecosystem

The skills gap is a critical barrier. A successful transition requires an intentional investment in human capital.

- Implement Progressive Upskilling: Move away from one-time training sessions. Develop a continuous learning path that begins with basic digital literacy, advances to specific instrument operation, and culminates in data science and AI interpretation skills. This mirrors the finding that effective AI adoption integrates tools into collaborative workflows rather than simply replacing human elements [25].

- Establish Internal Knowledge-Sharing Networks: Create a community of practice or "power users" within the lab or department. These individuals can provide peer-to-peer support, troubleshoot common issues, and help disseminate best practices, reducing the burden on a single expert [1].

- Leverage Vendor Training and Resources: When procuring equipment, negotiate for comprehensive, hands-on training from the vendor. Furthermore, explore the growing number of instructional short courses and workshops offered by conferences and universities, which are designed to provide in-depth, technical education on these emerging topics [28].

Managing Cultural and Organizational Change

Technology adoption is, at its core, a human-centric challenge. Overcoming cultural inertia is essential.

- Foster a Culture of "Augmented Intelligence": Frame AI and automation as tools that augment, not replace, researcher expertise. The A-Lab exemplifies this, where AI proposes recipes, but the underlying logic is grounded in human knowledge and thermodynamics [19]. Position these tools as a means to liberate scientists from repetitive tasks, allowing them to focus on creative problem-solving and experimental design [1].

- Demonstrate Value with Pilot Projects: Launch a small-scale, high-visibility pilot project with a clear objective. A successful demonstration that quickly generates publishable results or solves a long-standing lab problem is the most powerful tool for winning over skeptics.

- Champion the Shift to Data-Centric Science: Actively promote the transition from traditional, notebook-centric work to a data-centric ecosystem. This involves rethinking how scientific data flows through an organization and is a fundamental cultural shift that underpins the lab of the future [1].

Case Study & Experimental Protocol: The A-Lab

Background and Workflow

The A-Lab (Autonomous Laboratory) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory provides a groundbreaking, real-world example of overcoming adoption barriers to achieve transformative results. Its mission was to close the gap between computational materials prediction and experimental realization using a fully autonomous workflow [19].

The following diagram visualizes the A-Lab's core operational cycle, illustrating the integration of computation, robotics, and AI-driven decision-making.

Diagram 1: A-Lab Autonomous Synthesis Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To autonomously synthesize and characterize novel, computationally predicted inorganic powder compounds.

Methodology:

Target Identification & Feasibility Check:

- Input: Targets are selected from large-scale ab initio phase-stability databases (e.g., the Materials Project) [19].

- Action: The system filters for air-stable compounds predicted to be on or near the thermodynamic convex hull of stability.

Recipe Proposal (AI-Driven):

- Input: The target compound's chemical formula.

- Action 1 (Literature Inspiration): A natural language processing (NLP) model, trained on vast synthesis literature, proposes initial precursor combinations and a synthesis temperature based on analogy to known, similar materials [19].