Automated Synthesis Platforms in Organic Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Automated synthesis platforms represent a paradigm shift in organic chemistry, integrating robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-throughput experimentation to accelerate molecular discovery.

Automated Synthesis Platforms in Organic Chemistry: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

Automated synthesis platforms represent a paradigm shift in organic chemistry, integrating robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-throughput experimentation to accelerate molecular discovery. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, detailing how these systems use robotic equipment and software control to perform chemical synthesis, thereby increasing efficiency, reproducibility, and safety. We explore the foundational concepts and historical evolution of these platforms, examine the core hardware and software methodologies driving current applications in drug discovery and materials science, and address key challenges in optimization and reproducibility. Finally, we evaluate the performance and real-world impact of these systems through comparative analysis and case studies, offering a forward-looking perspective on their role in advancing biomedical research.

The Foundations of Automated Synthesis: From Concept to Core Components

Automated synthesis represents a paradigm shift in organic chemistry and materials research, transitioning the practice of chemical synthesis from a manual, artisanal process to a machine-driven, reproducible workflow. In the context of a broader thesis on "What is an automated synthesis platform in organic chemistry research," this technical guide examines the core components that define these systems. An automated synthesis platform integrates robotic hardware for physical experimentation with sophisticated software control systems that orchestrate the entire research process, from experimental planning to execution and analysis [1]. These platforms have evolved from simple automated reactors to fully autonomous laboratories that can operate with minimal human intervention, significantly accelerating the pace of chemical discovery and development, particularly in fields such as drug development where rapid synthesis of novel compounds is crucial [1] [2].

The fundamental distinction in this field lies between automation (machines executing predefined tasks) and autonomy (systems making independent decisions based on experimental data) [3]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the robotic systems and software control architectures that enable this transition, with specific technical details, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand or implement these technologies.

Core Components of Automated Synthesis Platforms

Robotic Systems and Hardware Configuration

The physical implementation of automated synthesis requires specialized robotic systems that replicate and extend the capabilities of human chemists. These systems can be categorized into two primary architectural approaches: integrated fixed systems and modular mobile platforms.

Integrated fixed systems typically combine synthesis, analysis, and purification modules within a single unified platform. Examples include commercially available synthesizers like the Chemspeed ISynth, which incorporate reagent storage, reactors, and sometimes inline analytical capabilities in a fixed configuration [3]. These systems benefit from optimized workflows but lack flexibility for reconfiguration.

In contrast, modular platforms use mobile robots that transport samples between standalone instruments. This approach was notably demonstrated by Dai et al., where free-roaming robots connected a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer, UPLC-MS, and benchtop NMR into a cohesive workflow [3]. This architecture allows researchers to incorporate standard laboratory equipment without extensive modification, enabling shared use with human operators and greater flexibility in analytical capabilities.

The hardware configuration of any automated synthesis platform typically consists of four essential modules [1]:

- Reagent storage and dispensing systems that store starting materials and automatically dispense precise volumes according to programmed parameters.

- Reactor modules where chemical transformations occur, with capabilities for temperature control, mixing, and reaction monitoring.

- Purification modules for isolating desired products from crude reaction mixtures.

- Analytical instrumentation for characterizing reaction outcomes, most commonly liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Table 1: Quantitative Capabilities of Robotic Synthesis Platforms

| Platform Type | Throughput (Reactions/Day) | Analytical Techniques | Synthesis Capabilities | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Mobile Robot Platform | Limited only by robot mobility | UPLC-MS, Benchtop NMR | Exploratory synthesis, supramolecular chemistry, photochemistry | [3] |

| High-Throughput Screening Robot | ~1,000 reactions | UV-Vis spectroscopy | Reaction optimization, network mapping | [4] |

| Solid-State A-Lab Platform | ~3 materials/day | XRD, ML-based phase identification | Inorganic material synthesis | [2] |

Software Control and Architecture

Software systems form the cognitive core of automated synthesis platforms, transforming them from mere automated equipment to intelligent research tools. These software components perform two primary functions: monitoring and analyzing the synthesis process, and designing synthesis strategies while guiding hardware operations [1].

The evolution of these control systems has progressed from simple scripted protocols to artificial intelligence-driven planning tools. Modern platforms employ a layered architecture where high-level synthesis planning interfaces with low-level hardware control. Steiner et al. demonstrated this approach with the "Chemputer" system, which uses a chemical description language (XDL) to create hardware-agnostic synthesis procedures that can be executed across different robotic platforms [5].

More recently, orchestration architectures like ChemOS 2.0 have been developed to manage the complexity of self-driving laboratories. This architecture treats the entire laboratory as an "operating system," efficiently coordinating communication, data exchange, and instruction management among modular components [6]. It combines ab initio calculations, experimental orchestration, and statistical algorithms to guide closed-loop operations for materials discovery.

For synthesis planning, computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) tools have become increasingly sophisticated. Early rule-based systems have been largely superseded by data-driven approaches using machine learning models trained on extensive reaction databases. Systems such as ASKCOS and Synthia use neural network models to propose plausible synthetic routes for target molecules, considering both chemical feasibility and practical considerations like reagent availability [5] [7].

Recent Technological Advances

Mobile Robotic Systems for Exploratory Chemistry

A significant advancement in automated synthesis is the development of mobile robotic systems that can operate standard laboratory equipment in shared research spaces. Dai et al. demonstrated this approach using free-roaming robots that transport samples between a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer, UPLC-MS, and benchtop NMR spectrometer [3]. This architecture creates a modular workflow where robots physically connect otherwise independent instruments, allowing existing laboratory equipment to be incorporated into automated workflows without monopolization or extensive redesign.

This platform addressed the challenge of exploratory synthesis where reaction outcomes are not easily reduced to a single optimization metric. Unlike previous systems focused on optimizing known reactions, this approach enables discovery-oriented research where multiple potential products might form, such as in supramolecular chemistry or reaction screening. The system uses a heuristic decision-maker that processes orthogonal analytical data (UPLC-MS and NMR) to make human-like decisions about which reactions to advance, scale up, or discard [3].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

The integration of artificial intelligence has transformed automated synthesis platforms from programmable equipment to autonomous research assistants. AI systems in chemistry perform multiple critical functions: predicting reaction outcomes, controlling chemical selectivity, planning synthesis routes, accelerating catalyst discovery, and driving material innovation [8].

Large Language Models (LLMs) have recently emerged as powerful controllers for automated synthesis platforms. Systems such as Coscientist and ChemCrow demonstrate that LLM-based agents can autonomously design, plan, and execute complex chemical experiments [2]. These systems leverage the reasoning capabilities of foundation models like GPT-4, enhanced with specialized chemical tools for tasks such as literature search, procedure planning, and hardware control [9].

Ruan et al. developed an LLM-based reaction development framework (LLM-RDF) comprising six specialized agents: Literature Scouter, Experiment Designer, Hardware Executor, Spectrum Analyzer, Separation Instructor, and Result Interpreter [9]. This system can guide the entire synthesis development process, from initial literature search to substrate scope screening, reaction optimization, and final product purification, demonstrating the potential for end-to-end automation of chemical research.

Self-Driving Laboratories and Continuous Workflows

The convergence of robotic hardware and AI software has enabled the creation of self-driving laboratories (SDLs) – fully integrated systems that continuously plan, execute, and learn from experiments without human intervention. ChemOS 2.0 represents an orchestration architecture specifically designed for such SDLs, coordinating communication, data exchange, and instruction management among modular laboratory components [6].

These systems implement complete design-make-test-analyze cycles, where computational models propose experiments, robotic systems execute them, analytical instruments characterize the results, and AI algorithms interpret the data to plan subsequent iterations. This closed-loop approach has been successfully demonstrated in both organic synthesis and materials science. The A-Lab platform for solid-state materials synthesis exemplifies this capability, having autonomously synthesized 41 of 58 target inorganic compounds over 17 days of continuous operation [2].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Advanced Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Platform | AI/Control Method | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot Platform | Heuristic decision-maker | Exploratory organic synthesis | Autonomous multi-day campaigns for supramolecular assembly | [3] |

| LLM-RDF | GPT-4-based multi-agent system | Reaction development & optimization | End-to-end synthesis development for multiple reaction types | [9] |

| A-Lab | Active learning with ML analysis | Solid-state materials | 71% success rate (41/58 compounds) in autonomous synthesis | [2] |

| Hyperspace Mapping Robot | UV-Vis with spectral unmixing | Reaction condition mapping | ~1,000 reactions per day, yield estimates within 5% accuracy | [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis Using Mobile Robots

The methodology for autonomous exploratory synthesis developed by Dai et al. provides a comprehensive example of integrated robotic and software control [3]. This protocol can be adapted for various discovery-oriented synthesis applications:

Workflow Initialization: The researcher defines the chemical space to explore (starting materials, reaction types) and establishes experiment-specific pass/fail criteria for the heuristic decision-maker based on domain knowledge.

Reaction Execution: The automated synthesis platform (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) prepares reaction mixtures in parallel according to the experimental design, handling liquid transfers, mixing, and temperature control.

Sample Preparation and Transport: Following synthesis, the platform aliquots each reaction mixture and reformats it for MS and NMR analysis. Mobile robots then transport these samples to the respective analytical instruments.

Orthogonal Analysis: The UPLC-MS system separates components and provides mass data, while the benchtop NMR spectrometer collects structural information. Both instruments operate using standard protocols and consumables.

Data Processing and Decision Making: The heuristic decision-maker processes both datasets, applying pass/fail criteria to each technique. For a reaction to proceed, it must typically pass both analyses. The algorithm then selects successful reactions for replication (to confirm reproducibility) or scale-up for further elaboration.

Iterative Cycle: The system continues through multiple synthesis-analysis-decision cycles, mimicking human decision protocols to explore the chemical space autonomously.

This protocol is particularly valuable for supramolecular chemistry and other complex synthesis areas where multiple products can form, as it can identify and characterize successful reactions without predefining a single target compound.

Protocol for High-Throughput Reaction Hyperspace Mapping

For reaction optimization and mechanism elucidation, the high-throughput hyperspace mapping approach developed by the researchers behind citation [4] provides a methodology for efficiently exploring multidimensional parameter spaces:

Experimental Design: Define an N-dimensional grid of reaction conditions (e.g., varying concentrations, temperatures, stoichiometries) to systematically explore the parameter space.

Robotic Execution: The robotic platform automatically prepares reactions according to the experimental design matrix, using precise liquid handling capabilities to ensure reproducibility.

UV-Vis Spectral Acquisition: For each reaction condition, the system acquires UV-Vis absorption spectra at predetermined time points. This rapid analysis (approximately 8 seconds per spectrum) enables characterization of thousands of conditions.

Bulk Chromatographic Separation: Combine crude reaction mixtures from all hyperspace points and separate by preparative chromatography to isolate all reaction products formed across the entire condition space.

Component Identification: Identify isolated fractions using traditional spectroscopic methods (NMR, MS) to establish the "basis set" of possible reaction products.

Spectral Unmixing: Construct calibration curves for each identified component and use vector decomposition techniques to fit the complex UV-Vis spectra from each reaction condition to linear combinations of reference spectra.

Anomaly Detection: Apply the Durbin-Watson statistic to detect systematic deviations between experimental and fitted spectra, identifying regions of unexpected reactivity or novel products.

Hyperspace Reconstruction: Map the yields of all identified products across the multidimensional parameter space, revealing complex relationships between conditions and outcomes.

This protocol enables comprehensive reaction characterization at a scale impractical with manual methods, providing detailed mechanistic insights and optimization guidance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of automated synthesis platforms requires both physical components and computational tools. The following table details essential elements for establishing automated synthesis capabilities:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Component | Type | Function | Examples/Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Synthesizer | Hardware | Precise reagent dispensing, reaction control under various conditions | Chemspeed ISynth, commercial microwave vial systems [3] [5] |

| Mobile Robot Agents | Hardware | Sample transport between instruments, operating equipment | Free-roaming robots with multipurpose grippers [3] |

| UPLC-MS System | Analytical | Separation and mass-based identification of reaction components | Commercial UPLC-MS with automated sampling [3] |

| Benchtop NMR | Analytical | Structural elucidation of reaction products | 80 MHz benchtop NMR spectrometer [3] |

| Chemical Databases | Software | Reaction knowledge for synthesis planning and validation | Reaxys, Open Reaction Database, USPTO patent collections [5] [7] |

| Synthesis Planners | Software | Retrosynthetic analysis and route proposal | ASKCOS, Synthia, AiZynthFinder [5] [7] |

| Orchestration Platforms | Software | Coordinating hardware, data flow, and experiment sequences | ChemOS 2.0, custom Python frameworks [3] [6] |

| LLM-Based Agents | Software | Natural language interaction, experimental design, decision-making | Coscientist, ChemCrow, LLM-RDF [9] [2] |

| CY-09 | CY-09, MF:C19H12F3NO3S2, MW:423.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TH5487 | TH5487, MF:C19H18BrIN4O2, MW:541.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Automated synthesis platforms represent the culmination of decades of advancement in both robotic hardware and software control systems. The integration of mobile robotic systems with AI-driven decision-making has transformed these platforms from simple automated tools to autonomous research partners capable of exploratory chemistry and discovery. The core definition of an automated synthesis platform in organic chemistry research encompasses physically robust robotic systems for experiment execution coupled with intelligent software that plans, analyzes, and learns from experimental data.

As these technologies continue to evolve, several challenges remain, including the need for more generalized hardware architectures, improved error handling and recovery, better uncertainty quantification in AI models, and standardized data formats to facilitate knowledge sharing [2]. Nevertheless, the current state of automated synthesis already demonstrates remarkable capabilities to accelerate chemical research, reduce manual labor, and explore chemical spaces that would be impractical through traditional manual approaches.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these systems' components and capabilities is increasingly essential for leveraging their potential. The frameworks, protocols, and architectures described in this technical guide provide a foundation for implementing and advancing automated synthesis in both academic and industrial settings, ultimately accelerating the discovery and development of new molecules and materials.

The field of organic chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from manual, artisanal practices to a data-driven, automated science. The concept of an automated synthesis platform in organic chemistry research represents an integrated system that combines hardware (robotics, fluidic systems, reactors) with sophisticated software (artificial intelligence, machine learning, data analytics) to plan, execute, and optimize the synthesis of molecular structures with minimal human intervention [10] [11]. This evolution began with specialized instruments designed for a single class of molecules and has progressed toward intelligent systems capable of autonomous decision-making for broad synthetic challenges. This whitepaper traces the historical trajectory of automated synthesis from its origins in peptide chemistry to the contemporary landscape of AI-driven platforms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical framework for understanding this rapidly advancing field.

The Foundations: Early Automation in Peptide Synthesis

The genesis of automated synthesis can be traced to a specific challenge in biochemical research: the labor-intensive process of constructing peptide chains. In the 1960s, Robert Bruce Merrifield pioneered the first automated system in organic chemistry with his development of solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) [10]. This groundbreaking methodology established the core architectural principles that would influence subsequent automation efforts.

Technical Framework of Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis

The SPPS system automated molecular assembly by addressing a fundamental bottleneck: purification after each reaction step. Its experimental protocol was built on several key innovations:

- Solid Support: The C-terminus of the growing peptide chain was covalently attached to an insoluble polymer resin, enabling facile separation of the anchored peptide from soluble reagents and by-products through simple filtration and washing.

- Protective Group Strategy: The N-terminus was protected with a temporary protecting group (initially t-Boc, later Fmoc), allowing for sequential, directional chain elongation.

- Cyclic Automation: The setup automated the repetitive cycle of deprotection (removal of the N-terminal protecting group), washing, acylation (coupling of the next amino acid), and washing again [10].

This "build on a resin" approach meant that the synthesis machine could be programmed to pump relevant reagents and solvents into the reaction vessel, mix them with the resin, and remove them in the correct sequence. While revolutionary, this early automation was domain-specific, primarily addressing the linear assembly of a single class of biomolecules through well-established coupling chemistry.

The Expansion: Toward Broad Synthetic Automation

For decades after Merrifield's innovation, organic synthesis remained predominantly manual. The high variability of organic reactions, the diversity of required equipment, and differences in techniques across laboratories created significant barriers to automation [10]. A new wave of innovation began to address these challenges, moving beyond peptides to enable the synthesis of more diverse small molecules.

Enabling Technologies for Broader Automation

The expansion of automation capabilities was fueled by parallel advancements in several key areas:

- Flow Chemistry Platforms: Flow-based synthetic systems provided precise control over reaction parameters including temperature, reaction time, and composition, overcoming many reproducibility issues of batch chemistry [10]. For example, Gilmore and coworkers developed an automated multistep synthesizer that arranged multiple continuous flow modules around a central core, capable of providing both linear and convergent synthetic processes without manual reconfiguration [10].

- Modular Hardware Systems: Platforms like the Chemputer, developed by Cronin's group, introduced a new paradigm by using a chemical programming language to standardize and automate bench-scale techniques [10]. This system could translate synthetic procedures from publications into executable commands for robotic hardware.

- Integrated Analytical Monitoring: The incorporation of inline monitoring techniques, such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, provided real-time feedback on reaction progress, facilitating post-reaction analysis and enabling future closed-loop optimization [10].

Table 1: Key Technology Platforms in the Expansion of Synthetic Automation

| Platform/Technology | Key Innovation | Synthetic Scope | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis | Polymer-supported synthesis & cyclic automation | Peptides | [10] |

| Radial Flow Synthesizer | Continuous flow modules around a central core | Small molecule libraries (e.g., Rufinamide derivatives) | [10] |

| The Chemputer | Chemical description language driving robotic execution | Pharmaceutical compounds | [10] |

| Automated Micro-fluidic Platform | High-throughput experimentation with single-droplet screening | Electroorganic process discovery | [10] |

The Revolution: Integration of Artificial Intelligence

The most significant transformation in automated synthesis began with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), creating systems that could not only execute predefined procedures but also plan and optimize synthetic routes. This marked the transition from automated to increasingly autonomous platforms [10] [12].

AI-Driven Retrosynthesis and Reaction Planning

AI has fundamentally revolutionized the foundational organic chemistry practice of retrosynthetic analysis. Platforms such as IBM RXN, AiZynthFinder, and Synthia now leverage algorithms trained on millions of published chemical reactions to rapidly generate viable synthetic pathways [13]. These systems can identify unconventional yet viable reaction routes that might be overlooked by human intuition, significantly expanding the accessible synthetic space.

Coley et al. demonstrated a landmark integration where a computer-aided synthesis program, informed by millions of published reactions, directed a modular continuous flow platform that automatically reconfigured a robotic arm to execute the synthesis [10] [12]. This system successfully planned and synthesized 15 pharmaceutical compounds, including ACE inhibitors and NSAIDs, showcasing the power of combining AI planning with robotic execution.

Machine Learning for Reaction Optimization

Beyond pathway planning, ML algorithms now optimize reaction conditions through iterative, data-driven experimentation. Grzybowski, Burke, and colleagues developed an iterative machine learning system that employed a closed-loop workflow to identify optimal conditions for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions [10]. The system used machine-learned data to prioritize and select subsequent reactions for testing, with robotic experimentation ensuring precision and reproducibility.

In a dramatic demonstration of throughput, Cooper's group developed an AI-integrated mobile robot that autonomously conducted 688 reactions over eight days to systematically explore ten different reaction variables [10]. This scale of parallel experimentation generates the high-quality datasets necessary to train accurate predictive models for chemical reactivity.

The Emergence of Hybrid Organic-Enzymatic Planning

The most recent innovations involve combining organic synthesis with enzymatic catalysis. The ChemEnzyRetroPlanner platform, introduced in 2025, represents this cutting-edge direction [7]. It is an open-source hybrid synthesis planning platform that features:

- Hybrid Retrosynthesis Planning: Combining traditional organic transformations with biocatalytic steps.

- RetroRollout* Search Algorithm: A advanced search algorithm that outperforms existing tools in planning synthesis routes for organic compounds and natural products [7].

- In silico Validation: Computational assessment of enzyme active sites to validate proposed biocatalytic steps.

- Large Language Model Integration: Leveraging models like Llama3.1 to autonomously activate hybrid synthesis strategies for diverse scenarios [7].

This platform exemplifies the trend toward more holistic synthesis planning that leverages the complementary strengths of organic and enzymatic catalysis to achieve more efficient and sustainable synthetic strategies.

The Modern Automated Synthesis Platform: Architecture and Components

The contemporary automated synthesis platform represents a tightly integrated ecosystem of hardware, software, and data analytics. The architecture functions as a cohesive unit to enable end-to-end molecular design and production.

System Architecture and Workflow

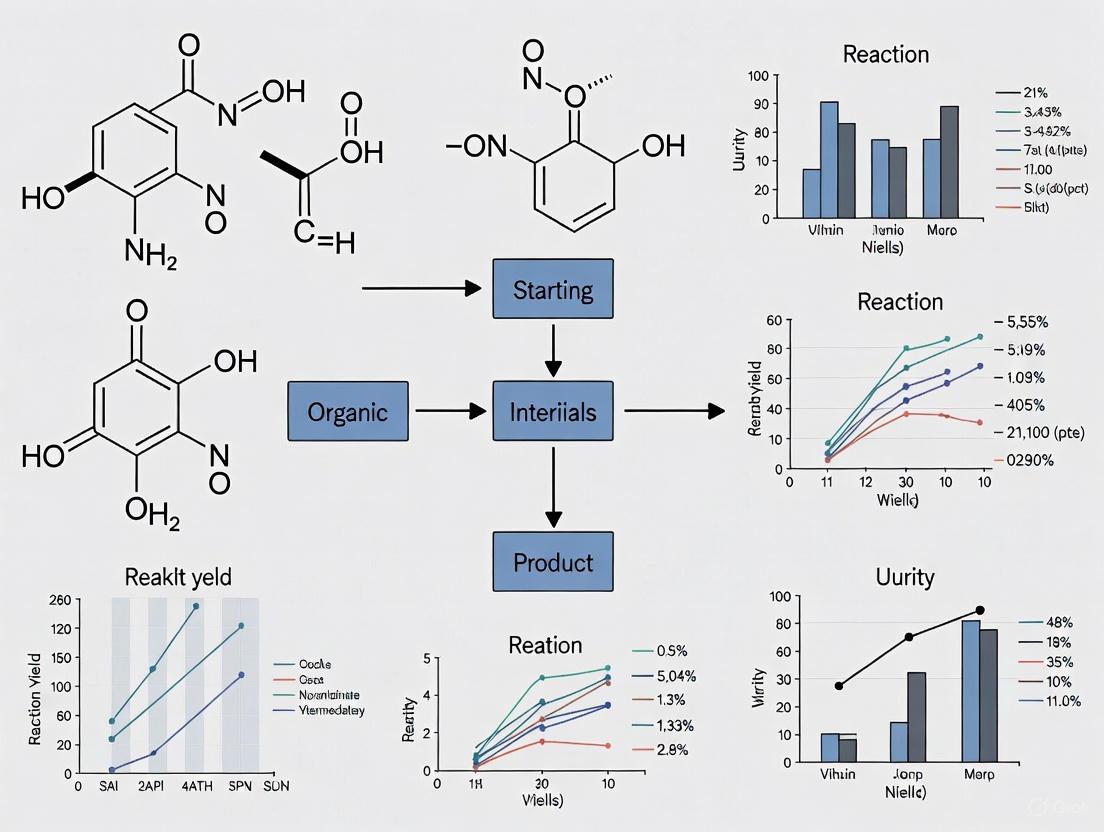

The following diagram illustrates the information flow and core components of a modern AI-driven automated synthesis platform:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Modern automated platforms rely on specialized reagents and materials that enable reproducible, high-throughput experimentation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Automated Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Automated Synthesis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Supports (Resins) | Provides insoluble matrix for immobilized synthesis; enables filtration-based purification | Solid-phase peptide synthesis, oligomer synthesis |

| TIDA (Tetramethyl N-methyliminodiacetic acid) | ||

| Supports C-Csp3 bond formation in automated small molecule synthesis | Iterative cross-coupling for diverse small molecules [10] | |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries | Facilitates ultra-high-throughput screening by tagging compounds with DNA barcodes | Hit identification in drug discovery [14] |

| Commercial Building Blocks | Standardized, quality-controlled chemical precursors for reliable automation | Access to diverse chemical space (5000+ blocks) [10] |

| Specialized Catalysts (e.g., Cobalt) | Enables specific bond formations in automated assembly strategies | 2D and 3D molecular construction [10] |

| GSK963 | GSK963, MF:C14H18N2O, MW:230.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IWR-1 | IWR-1, MF:C25H19N3O3, MW:409.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: AI-Driven Synthesis

The following workflow details the experimental methodology for a contemporary AI-driven synthesis, as exemplified by platforms from Coley et al. and Jiang et al. [10]:

Target Specification and AI Planning: The process begins with the digital input of the target molecule's structure. The AI planning module (e.g., CASP software) performs a retrosynthetic analysis using reaction databases containing millions of transformations. It generates multiple synthetic routes with ranked feasibility scores, including specific reaction conditions, catalysts, and potential by-products.

Human Expert Refinement: A synthetic chemist reviews the AI-proposed routes, applying practical knowledge to address limitations such as stereochemical outcomes, solvent compatibility with hardware, and substrate solubility concerns. This human-AI collaboration refines the "chemical recipe file."

Robotic Execution: The finalized protocol is translated into machine commands for the robotic platform. In a flow chemistry setup, this involves:

- Configuration of reactor modules (temperature, volume)

- Priming of solvent and reagent lines

- Calibration of pumping systems for precise reagent delivery

- Execution of sequential reactions with intermediate processing

Real-Time Monitoring and Feedback: Integrated analytical tools (e.g., inline IR, NMR) monitor reaction progress, detecting intermediates and by-products. This real-time data collection provides immediate quality control and process verification.

Purification and Compound Handling: Post-reaction, the system directs purification through integrated chromatography or catch-and-release techniques, culminating in final compound isolation in standardized formats suitable for downstream testing.

Data Capture and Machine Learning: All experimental parameters and outcomes are automatically logged in a structured database. This information feeds back into the machine learning models, continuously improving the system's predictive accuracy and performance - a critical step toward fully autonomous operation [10] [11].

Current Capabilities and Quantitative Performance

Modern platforms have demonstrated significant measurable advances in synthetic efficiency and scope. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from representative systems:

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Platform/System | Synthetic Output | Yield/Efficiency | Key Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burke's Molecular Assembly | 14 diverse classes of small molecules | N/A | 5000+ commercial building blocks accessible | [10] |

| Coley's AI-Flow Platform | 15 compounds (NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors) | 342-572 mg/h | Automated planning & execution | [10] [12] |

| Wang's Electrocatalyst Testing | 109 copper-based bimetallic catalysts | 942 effective tests | 55 hours for complete screening | [10] |

| Cooper's Mobile Robot | Systematic condition screening | 688 reactions | 8 days autonomous operation | [10] |

| Tiny Tides Peptide Synthesis | Peptide-PNA conjugates | Efficient conjugation | Fast-flow platform | [10] |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

As the field advances toward truly autonomous synthesis, several challenges and future directions emerge. Current limitations include handling poor solubility compounds that clog flow systems, managing reactions requiring subambient temperatures, and achieving reliable prediction of stereochemical outcomes [12]. Future developments will likely focus on several key areas:

- Closed-Loop Optimization: Full integration of planning, execution, and analysis with minimal human intervention, where platforms can independently redesign synthetic strategies based on experimental failures [11].

- Advanced Purification Integration: Incorporating automated purification protocols directly into synthesis workflows, moving beyond reaction execution to complete molecule production [12].

- Hardware Miniaturization and Flexibility: Developing more compact, reconfigurable platforms that can fit standard laboratory spaces while accommodating diverse synthetic methodologies [10].

- Sustainability Focus: Leveraging AI to prioritize synthetic routes that minimize waste, energy consumption, and hazardous materials, aligning with green chemistry principles [13] [15].

The progression from specialized peptide synthesizers to general AI-driven platforms represents a fundamental shift in organic chemistry research methodology. This evolution has expanded from automating manual tasks to augmenting chemical intelligence itself, potentially redefining the role of the synthetic chemist from hands-on executor to strategic director of automated systems. As these platforms become more accessible and robust, they promise to accelerate discovery across pharmaceuticals, materials science, and beyond, while simultaneously addressing pressing challenges in sustainability and efficiency.

An automated synthesis platform represents a paradigm shift in chemical research, integrating robotics, software control, and often artificial intelligence (AI) to perform chemical synthesis with minimal human intervention [16]. These systems transform the traditional, manual trial-and-error approach into a streamlined, data-driven discovery process. At its core, such a platform is a robotic system capable of executing sequential experimental steps—from reagent dispensing and reaction setup to workup, analysis, and data logging—based on computer-devised or AI-generated plans [16] [10]. Framed within a broader thesis on modernizing organic chemistry, these platforms are not merely tools for automation but are foundational to realizing the vision of self-driving laboratories, where closed-loop systems autonomously design, execute, and analyze experiments to optimize reactions or discover new molecules [17] [18].

The convergence of high-throughput experimentation (HTE), modular hardware, and intelligent software defines the modern automated platform. HTE, characterized by the miniaturization and parallelization of reactions, serves as a critical engine for these systems, enabling the rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces [19]. When coupled with AI for planning and analysis, these platforms evolve into autonomous discovery engines [20] [17]. This technical guide delves into the three core benefits that make automated synthesis platforms indispensable for contemporary researchers and drug development professionals: unparalleled efficiency, robust reproducibility, and enhanced laboratory safety.

Core Benefit I: Dramatically Enhanced Experimental Efficiency

Automated synthesis platforms accelerate research by orders of magnitude through parallelization, continuous operation, and intelligent optimization, liberating scientists from repetitive tasks.

Parallelization and High-Throughput Experimentation

The fundamental efficiency gain comes from executing numerous reactions simultaneously. High-throughput experimentation (HTE) methodologies enable the testing of hundreds to thousands of reaction conditions in parallel using microtiter plates or multi-reactor arrays [19]. This contrasts starkly with the traditional "one variable at a time" (OVAT) approach. For instance, the PolyBLOCK platform allows 4 or 8 independent reaction zones to run concurrently under different conditions [21]. Ultra-HTE pushes this further, allowing for 1536 simultaneous reactions, vastly accelerating data generation [19]. This capability is crucial for applications like library synthesis for drug discovery, reaction condition optimization, and substrate scope exploration [19].

24/7 Unattended Operation and Resource Optimization

Robotic platforms operate continuously without fatigue. As noted in descriptions of intelligent platforms, coordination via robotic arms and scheduling systems enables "7*24 hour automated synthesis," overcoming human limitations of time and shift work [22]. This non-stop operation significantly compresses project timelines. Furthermore, automation enables precise miniaturization of reactions, consuming sub-milligram to milliliter quantities of valuable substrates and reagents. This reduces material costs and waste generation while allowing exploration of chemical space with scarce compounds [19].

Intelligent Optimization and Closed-Loop Workflows

Integration with AI and machine learning (ML) creates a powerful feedback loop. The platform can execute an experiment, analyze the results via in-line analytics, and use an optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms) to decide the next best experiment to run [17] [23] [18]. This closed-loop "design-make-test-analyze" cycle efficiently navigates complex, multi-parameter spaces to find optimal conditions or new discoveries with far fewer iterations than manual approaches. For example, a mobile robotic chemist used Bayesian optimization to autonomously run 688 experiments over eight days, thoroughly mapping a photocatalytic reaction space [10].

Table 1: Quantitative Efficiency Gains from Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Efficiency Metric | Traditional Manual | Automated/HTE Platform | Key Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactions per Day | Dozens (limited by chemist) | Hundreds to >1,500 (Ultra-HTE) | [19] |

| Operation Hours | ~8-12 hours/day | 24 hours/day, 7 days/week | [22] |

| Optimization Cycle Time | Days to weeks per iteration | Hours to days for full closed-loop campaign | [23] [18] |

| Material Consumption per Reaction | Often 10s-100s of mg | Micro- to nanoscale (e.g., MTP wells) | [19] |

Core Benefit II: Superior Reproducibility and Data Integrity

Automation mitigates human error and variability, ensuring consistent execution and generating high-quality, standardized data essential for scientific rigor and machine learning.

Standardization of Experimental Protocols

Manual experimentation is prone to technique-based variability between and even within researchers. Automated platforms execute precisely coded protocols consistently every time. Reagents are dispensed with high volumetric accuracy (e.g., liquid handling with ±1% accuracy [22]), stirring rates are controlled, and temperatures are maintained uniformly [21]. This eliminates subtle variations in addition speed, mixing efficiency, or temperature ramps that can impact yield and selectivity. The Chemputer platform uses a chemical programming language (χDL) to encode synthesis procedures as unambiguous, executable code, ensuring perfect protocol transfer [18].

Mitigation of Spatial and Operational Bias

In HTE, factors like uneven temperature or light distribution across a microtiter plate can cause "spatial bias" [19]. Advanced platforms address this through improved hardware design. Furthermore, automation eliminates operational biases such as inconsistent timing or order of steps. The integrated use of low-cost sensors (temperature, pH, color) provides continuous process monitoring, creating a "process fingerprint" that can be used to validate reproducibility across runs [18].

FAIR Data Generation and Management

Automated platforms are intrinsically data-generating machines. Every action, sensor reading, and analytical result is digitally recorded, creating comprehensive datasets. This aligns with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles, which are key to establishing HTE's utility [19]. Structured, high-quality data from automated systems is the ideal feedstock for training machine learning models, enabling predictive chemistry and further accelerating discovery [19] [17]. The database-centric architecture of autonomous laboratories ensures all data is stored, managed, and readily available for analysis [17].

Experimental Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization of a Catalytic Reaction This generic protocol, based on described systems [23] [18], exemplifies how reproducibility and efficiency are integrated.

- Platform Setup: Configure a robotic platform (e.g., liquid handler, reactor block) integrated with an in-line or at-line analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis, GC). Define a hardware graph linking all components.

- Procedure Encoding: Write the base reaction procedure (e.g., "add catalyst, stir, heat, add substrate, quench") in a dynamic chemical programming language like χDL [18]. Designate variables to optimize (e.g., catalyst loading, temperature, residence time).

- Optimization Configuration: Select an optimization algorithm (e.g., Bayesian Optimization, Phoenics). Define the objective function (e.g., maximize HPLC yield, minimize byproduct formation).

- Closed-Loop Execution: a. The system prepares the first set of conditions from an initial design or algorithm suggestion. b. It executes the reaction procedure robotically. c. An automated sample aliquot is transferred to the analytical instrument. d. The result is quantified and fed to the optimization algorithm. e. The algorithm suggests the next set of conditions. f. The loop (a-e) repeats for a set number of iterations or until convergence.

- Data Logging: All parameters, sensor telemetry, raw analytical data, and processed results are automatically saved to a structured database with timestamps and metadata.

Core Benefit III: Enhanced Laboratory Safety and Risk Mitigation

Automation creates a safer work environment by reducing direct human exposure to hazards and enabling proactive risk management through real-time monitoring.

Minimization of Human Exposure to Hazards

A primary safety benefit is the physical separation of the chemist from the chemical process. Robotic systems handle pyrophoric, toxic, corrosive, or sensitizing reagents, perform reactions under high pressure or with dangerous gases, and manage highly exothermic processes [16]. This drastically reduces the risk of inhalation, skin contact, or exposure to reactive incidents. As stated, automation leads to "security, and safety, all resulting from decreased human involvement" [16].

Real-Time Process Monitoring and Adaptive Control

Integrated sensors allow for real-time reaction monitoring, enabling the system to detect and respond to unsafe conditions. For example, a temperature sensor can monitor an exothermic oxidation. The dynamic programming can pause reagent addition if a temperature threshold is exceeded, preventing thermal runaway, and only resume once the temperature is back within a safe range—a task demonstrated for scale-up safety [18]. Color, pH, and conductivity sensors provide additional layers of process awareness.

Handling of Critical Operations and Failure Detection

Automated platforms can reliably execute safety-critical operations like slow additions, handling of air-sensitive materials under inert atmosphere, and operations at extreme temperatures (-80°C to +200°C) [19] [21]. Vision systems or liquid sensors can detect hardware failures, such as syringe breakage or blockages, and alert operators or initiate safe shutdown procedures [18]. This proactive failure management prevents accidents that might result from undetected equipment faults during manual operation.

Table 2: Safety-Enhancing Features of Automated Platforms

| Safety Hazard | Manual Risk | Automated Mitigation Strategy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to Toxic/Reagents | Direct handling risk | Robotic dispensing and enclosure | [16] [22] |

| Exothermic Runaway | Relies on human vigilance | Real-time temperature feedback with adaptive pause/control | [18] |

| Air-Sensitive Chemistry | Complex Schlenk techniques | Integrated inert atmosphere gloveboxes or purged systems | [19] |

| High-Pressure Reactions | Potential for vessel failure | Automated reactors with pressure sensors and relief, remote operation | [21] |

| Repetitive Strain Injury | From manual pipetting/weighing | Complete elimination of repetitive manual tasks | [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components of an Automated Synthesis Platform

Building or utilizing an automated platform involves a suite of integrated hardware and software solutions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Platform Components

| Component Category | Specific Item/Technology | Function in the Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Execution | Parallel Reactor Block (e.g., PolyBLOCK) | Provides multiple independently controlled reaction vessels for HTE [21]. |

| Continuous Flow Reactor Modules | Enables precise control of time, temperature, and mixing for fast or hazardous reactions [24] [10]. | |

| Liquid/Solid Handling | Automated Liquid Handling Workstation | Precisely dispenses liquid reagents with sub-microliter accuracy for assay setup and miniaturization [22]. |

| Automated Powder Dispensing System | Accurately weighs and dispenses solid catalysts, substrates, and reagents (e.g., ±0.3mg accuracy) [22]. | |

| Process Monitoring | In-line Spectrophotometers (UV-Vis, Raman, FTIR) | Provides real-time reaction monitoring for kinetics and endpoint detection [18]. |

| Low-Cost Sensors (Temperature, pH, Color) | Monitors process conditions for safety, control, and creating process fingerprints [18]. | |

| Analysis & Decision | Integrated Analytical Instruments (HPLC, GC, MS) | Automatically analyzes reaction outcomes to quantify yield, purity, and selectivity [18] [22]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | AI algorithm that intelligently selects the next experiment to maximize information gain or objective performance [17] [23]. | |

| Programming & Control | Chemical Programming Language (e.g., χDL) | Encodes synthetic procedures in a hardware-agnostic, executable format for reproducibility [18]. |

| Robot Operating System (ROS) / Custom Middleware | Controls robotic arms, coordinates hardware modules, and schedules tasks [22]. | |

| Data Management | Chemical Science Database / ELN | Stores structured FAIR data from experiments, essential for ML and knowledge management [19] [17]. |

| GNE 220 | GNE 220, MF:C25H26N8, MW:438.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anemarsaponin E | Anemarsaponin E, CAS:244779-38-2, MF:C46H78O19, MW:935.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Automated Synthesis Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow and architecture of a closed-loop automated synthesis platform.

Diagram 1: Closed-Loop Self-Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Modular Architecture of an Intelligent Synthesis Platform

Automated synthesis platforms are transformative instruments in organic chemistry research, fundamentally redefining the pace, reliability, and safety of molecular discovery and process development. As detailed in this guide, their core benefits are interdependent: efficiency is achieved through parallel HTE and non-stop operation; reproducibility is guaranteed by precise robotic execution and FAIR data practices; and safety is enhanced by removing personnel from hazards and introducing intelligent process control. Framed within the broader thesis of modernizing chemical research, these platforms represent the critical infrastructure necessary to realize the full potential of AI-driven discovery, continuous manufacturing, and the vision of the self-driving laboratory. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these platforms is no longer a futuristic concept but a strategic imperative to accelerate innovation, ensure robust results, and maintain a competitive edge.

In organic chemistry research, an automated synthesis platform is a integrated system that uses robotic hardware, software control, and data analytics to perform chemical synthesis with minimal human intervention. These platforms transform traditional manual processes into streamlined, reproducible workflows, accelerating discovery in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to materials science. The efficiency and reliability of these systems hinge on the seamless integration of four core technical modules: reagent storage, reactors, purification, and analytics. This technical guide examines the architecture, function, and interoperability of these key modules, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding and implementing automated synthesis solutions.

Core Technical Modules

Reagent Storage and Handling

The reagent storage and handling module serves as the foundation of any automated synthesis platform, ensuring precise, on-demand delivery of chemical starting materials. This system must maintain chemical integrity while providing robotic access to diverse building blocks.

Architecture and Specifications: Modern platforms employ chemical inventories capable of storing millions of compounds [5]. These systems typically utilize sample plates, vials, or cartridges arranged in modular racks with environmental controls (e.g., inert gas atmosphere, cooling, or desiccation) to preserve reagent stability. For instance, the Synple 2 system uses pre-packed reaction cartridges to standardize and simplify reagent delivery [25]. Liquid handling is achieved through precision syringe pumps or ink-jet type dispensers capable of transferring volumes from microliters to hundreds of milliliters with accuracy exceeding 99% [16].

Integration Requirements: Effective reagent storage modules interface directly with platform control software to track inventory levels, monitor reagent stability, and coordinate with synthesis planning algorithms. The ChemEnzyRetroPlanner exemplifies this integration, using AI-driven decision-making to select appropriate building blocks from available inventory for hybrid organic-enzymatic synthesis [7].

Reactor Systems and Reaction Execution

Reactor modules provide the controlled environments where chemical transformations occur. These systems vary in configuration, temperature range, and scalability, directly impacting the breadth of chemistries a platform can perform.

Configuration Types: Automated platforms primarily use two reactor paradigms:

- Batch Reactors: Discrete reaction vessels (e.g., microwave vials, round-bottom flasks) operating in parallel. The PolyBLOCK system, for example, features 4 or 8 independently controlled zones with temperature ranges from -40°C to +200°C and compatibility with vessels from 1 mL to 500 mL [26].

- Flow Reactors: Continuous-flow systems where reagents mix and react in tubular reactors, offering advantages in heat transfer and safety for exothermic reactions [5] [27].

Process Control Parameters: Advanced reactor modules provide independent control over critical reaction parameters including temperature (with precision of ±0.5°C), agitation (mechanical or magnetic stirring from 250-1500 rpm), pressure (from vacuum to high-pressure for hydrogenation), and atmosphere (inert gas purging for air-sensitive chemistry) [26] [5].

Implementation Example: In the synthesis of molecular rotaxanes using the Chemputer platform, reactors maintained precise temperature control throughout a 60-hour automated sequence involving 800 base steps, demonstrating the reliability required for complex molecular machine assembly [28].

Purification Systems

Purification modules isolate and refine reaction products between synthetic steps, representing a significant technical challenge in full automation. Without effective purification, multi-step syntheses cannot proceed autonomously.

Purification Modalities: Platforms typically incorporate multiple purification techniques to handle diverse chemical outcomes:

- Liquid Chromatography: Both analytical and preparative High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are workhorse techniques. The Mitsubishi robot-integrated platform described by Sutherland et al. seamlessly transfers samples from synthesis to purification to analysis stations [27] [29].

- Catch-and-Release Methods: Specialized purification strategies like the iterative MIDA-boronate coupling platform use selective immobilization to purify products [5].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography: Particularly valuable for biomolecules and molecular machines, as demonstrated in the automated rotaxane synthesis where it complemented silica gel chromatography [28].

Technical Challenges: Automated purification faces hurdles in universal application, as optimal conditions vary significantly between chemical systems. Platforms address this through method libraries and adaptive programming that tailores purification protocols to specific compound characteristics [5].

Analytical and Monitoring Systems

Analytical modules provide real-time feedback on reaction progress and product quality, enabling the platform to make autonomous decisions about subsequent steps. This represents the "sensory" system of automated synthesis.

In-line Analysis Technologies:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS): The most widely implemented technique for reaction monitoring and product identification in automated platforms [5].

- On-line NMR Spectroscopy: Provides structural elucidation capabilities, as implemented in the Chemputer platform for monitoring rotaxane formation [28].

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Used particularly in conjunction with high-throughput screening systems for substrate scope studies [9].

Data Integration: Advanced platforms like the LLM-based reaction development framework (LLM-RDF) incorporate specialized "Spectrum Analyzer" and "Result Interpreter" agents that automatically process analytical data to quantify yields, confirm identities, and recommend subsequent actions [9]. The integration of corona aerosol detection (CAD) offers potential for universal calibration curves without compound-specific standards [5].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and technologies for each module:

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Core Automated Synthesis Modules

| Module | Key Technologies | Performance Parameters | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Storage | Chemical inventories, pre-packed cartridges, precision liquid handlers | Storage for millions of compounds [5], volume accuracy >99%, nanoliter to milliliter transfer [16] | Synple 2 cartridges [25], Eli Lilly's 5-million compound inventory [5] |

| Reactor Systems | Parallel batch reactors, continuous flow reactors, temperature & agitation control | -40°C to +200°C range [26], 250-1500 rpm agitation, independent zone control | PolyBLOCK [26], Chemputer [28], flow chemistry platforms [27] |

| Purification | Preparative HPLC, size exclusion chromatography, catch-and-release methods | Automated fraction collection, solvent switching, method libraries for different compound classes | Mitsubishi robot-integrated HPLC [27], size exclusion in rotaxane synthesis [28] |

| Analytics | LC/MS, on-line NMR, GC, CAD | Real-time monitoring, structural elucidation, yield quantification without standards | Chemputer with on-line NMR [28], LLM-RDF Spectrum Analyzer [9] |

Integrated Workflow and System Operation

The power of automated synthesis platforms emerges from the seamless integration of these four core modules into a coordinated workflow. This integration enables the transition from isolated automated tasks to true autonomous synthesis.

Module Interoperability and Data Flow

Successful platform operation requires both physical sample transfer between modules and digital communication of results and instructions. The following diagram illustrates the information and material flow between core modules in a typical automated synthesis platform:

Figure 1: Automated synthesis platform workflow showing material flow (green arrows) and decision pathways (red arrows).

This workflow demonstrates how platforms function as integrated systems rather than discrete modules. For instance, in the LLM-RDF platform, analytical results from the "Spectrum Analyzer" directly inform the "Result Interpreter," which can then instruct the "Experiment Designer" to modify reaction conditions in an iterative optimization cycle [9].

Experimental Protocol: Automated Substrate Scope Investigation

To illustrate these modules working in concert, consider this detailed methodology for automated substrate scope screening, adapted from the LLM-RDF platform's investigation of copper/TEMPO-catalyzed aerobic alcohol oxidation [9]:

Objective: Rapidly evaluate reaction performance across diverse alcohol substrates to establish methodology applicability.

Experimental Workflow:

- Literature Scouter Agent Activation: The process initiates with the Literature Scouter agent querying the Semantic Scholar database to identify relevant synthetic methodologies and extract detailed experimental procedures for the target transformation [9].

- Experiment Design: The Experiment Designer agent translates literature procedures into executable experimental plans, defining substrate arrays (typically 24-96 substrates), control samples, and reaction condition variations. The agent addresses practical automation challenges such as solvent volatility and catalyst stability [9].

- Hardware Execution: The Hardware Executor implements the designed experiments using parallel reactor systems (e.g., PolyBLOCK) with precisely controlled parameters: temperature (25-70°C), oxygenation (bubbling air or O₂), agitation (750 rpm), and reaction time (4-24 hours) [9] [26].

- Reaction Monitoring: At predetermined intervals, automated liquid handlers transfer aliquots from reaction vessels to the analytics module for GC or LC/MS analysis to track reaction progression [9].

- Data Interpretation: The Spectrum Analyzer processes chromatographic data, while the Result Interpreter quantifies conversion and yield, compares performance across substrates, and identifies structural features correlating with success [9].

Key Technical Considerations:

- Solvent Selection: Address high MeCN volatility by alternative solvent screening or sealed reactor modifications [9].

- Catalyst Stability: Prepare Cu(I) catalyst stock solutions immediately before use or develop stabilized formulations [9].

- Analysis Calibration: Implement internal standards for accurate quantification in high-throughput screening mode.

This comprehensive protocol demonstrates how integrated modules transform a traditionally labor-intensive process into an automated, data-rich investigation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of automated synthesis requires both specialized equipment and carefully selected chemical materials. The following table details key reagent solutions and their functions in automated platforms:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

| Reagent/Category | Function in Automated Synthesis | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Libraries | Pre-formulated catalyst stocks for high-throughput screening; enables rapid reaction optimization | Cu/TEMPO catalyst system for aerobic oxidation [9]; palladium/nickel catalysts for ethylene polymerization [16] |

| Building Block Collections | Diverse chemical starting points for combinatorial synthesis and library generation; stored in platform-compatible formats | Pre-packed cartridges for Synple 2 system [25]; MIDA-boronates for iterative cross-coupling [5] |

| Specialized Solvents | Tailored solvent systems addressing automation challenges like volatility, viscosity, and compatibility with analytical flow paths | Low-volatility alternatives to MeCN for open-cap vial reactions [9]; degassed solvents for oxygen-sensitive chemistries [16] |

| Enzyme Preparations | Biocatalytic components for hybrid organic-enzymatic synthesis; requires stabilization for automated handling | Enzymes for chemoenzymatic pathways in ChemEnzyRetroPlanner [7]; enzyme degassing for oxygen-tolerant RAFT polymerization [16] |

| Derivatization Agents | Compounds that facilitate analysis or purification, such as chromophores for detection or tags for catch-and-release | Internal standards for GC/LC quantification [9]; functional handles for purification (e.g., MIDA-boronates) [5] |

| Mc-MMAD | Mc-MMAD, MF:C51H77N7O9S, MW:964.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LY2510924 | LY2510924, MF:C62H88N14O10, MW:1189.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Automated synthesis platforms represent a paradigm shift in organic chemistry research, transforming the art of chemical synthesis into an engineering discipline governed by precise digital control. The four core modules—reagent storage, reactors, purification, and analytics—function not as isolated components but as an integrated system whose collaborative efficiency exceeds the sum of its parts. As these platforms continue to evolve through advancements in AI-driven synthesis planning [7], LLM-based experimental execution [9], and increasingly sophisticated robotic hardware [28], they promise to redefine the pace and possibilities of molecular innovation. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this modular architecture provides both a framework for evaluating existing platforms and a blueprint for contributing to their future development.

Platforms in Action: Hardware, Software, and Real-World Applications

Automated synthesis platforms represent a paradigm shift in organic chemistry research, transitioning the laboratory from a manually-driven, artisanal environment to a data-rich, digitally-controlled discovery engine. In the context of drug development, these platforms are instrumental in accelerating the Design-Make-Test-Analyse (DMTA) cycle, where the synthesis ("Make") phase has traditionally been a significant bottleneck [30]. An automated synthesis platform integrates robotic hardware, various reactor configurations, and intelligent software to perform chemical reactions with minimal human intervention. This enables researchers and scientists to achieve higher throughput, improved reproducibility, and enhanced safety while exploring complex chemical space more efficiently [31] [20]. The core of these systems lies in the interplay between the robotic hardware that handles materials and the reactors where chemical transformations occur, with batch and flow systems representing the two predominant architectural philosophies.

Robotic Hardware for Automated Synthesis

The physical automation of synthetic procedures is achieved through a diverse array of robotic hardware. These components handle tasks ranging from liquid handling and solid dispensing to sample transport and reaction execution.

A significant advancement is the use of mobile robotic agents that operate equipment in a human-like way. These free-roaming robots can transport samples between physically separated synthesis and analysis modules, connecting a synthesizer to instruments like liquid chromatography–mass spectrometers (UPLC-MS) and benchtop nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers without requiring extensive laboratory redesign [3]. This creates a modular, scalable workflow where robots share existing equipment with human researchers.

At the heart of the synthesis module are automated synthesis platforms, such as the Chemspeed ISynth, which provide core capabilities for reagent dispensing, mixing, and temperature control in a controlled atmosphere [3]. For end-to-end workflow automation, platforms like those from Synple Chem combine synthesizers with pre-packaged reagent cartridges. Users simply add starting materials and select a cartridge; the instrument then manages reaction execution, work-up, and product separation or purification [31].

Complementing these are robotic process automation (RPA) systems, which are software-based bots that emulate human actions for digital tasks. In a synthesis context, this can include data migration, extracting information from structured and unstructured formats, and generating reports. Unlike traditional automation that requires deep system integration, RPA operates at the user interface level, offering rapid deployment and flexibility [32].

Table 1: Key Robotic Hardware Components in Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Hardware Component | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot Agents | Sample transportation and instrument operation | Free-roaming; uses multipurpose grippers; operates shared equipment in standard labs [3]. | Transporting reaction mixtures from synthesizer to UPLC-MS and NMR. |

| Automated Synthesis Platforms (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth) | Core reaction execution | Automated liquid/solid dispensing; temperature control; inert atmosphere [3]. | Parallel synthesis of compound libraries (e.g., ureas, thioureas). |

| Reagent Cartridge Systems (e.g., Synple Chem) | Simplified reagent integration | Pre-packaged, kit-based reagents for specific reaction types; enables fully automated, cartridge-based workflows [31]. | Reductive amination, amide formation, Suzuki coupling, Boc protection. |

| Software Bots (RPA) | Digital workflow automation | Manages digital tasks; operates at UI level; low-code deployment [32]. | Data migration, report generation, inventory updates. |

Reactor Configuration: Batch vs. Flow Systems

The reactor is the core component where the chemical reaction takes place, and its configuration fundamentally shapes the capabilities and limitations of an automated platform. The two primary reactor types are batch and continuous flow systems, each with distinct operational principles, advantages, and ideal use cases.

Batch Reactors

Batch reactors are closed vessels where reactants are charged initially, mixed, and left to react for a specified time before the products are discharged [33]. This makes them an unsteady-state operation where composition changes with time, though the composition is uniform throughout the vessel at any single instant [33].

The design and performance of an ideal batch reactor are governed by its material balance equation. For a limiting reactant A, the time required to achieve a conversion ( XA ) is given by: [ t = N{A0} \int{0}^{XA} \frac{dXA}{(-rA)V} ] where ( N{A0} ) is the initial moles of A, ( -rA ) is the rate of disappearance of A, and ( V ) is the reaction volume [33]. For constant-density systems (constant volume), this simplifies to: [ t = C{A0} \int{0}^{XA} \frac{dXA}{-rA} \quad \text{or} \quad t = -\int{C{A0}}^{CA} \frac{dCA}{-rA} ] where ( C_{A0} ) is the initial concentration of A [33].

Batch reactors are particularly well-suited for multistep syntheses and the production of moderate quantities of multiple products, as they allow for complex reaction sequences to be performed in a single vessel [34]. Their flexibility makes them ideal for exploratory chemistry and supramolecular chemistry, where outcomes can be unpredictable and involve complex product mixtures [3]. Modern automated batch systems, such as the iChemFoundry platform, enable high-throughput experimentation by running numerous small-scale batch reactions in parallel [20].

Flow Reactors

In contrast, flow reactors (including Plug Flow Reactors, PFRs) operate as continuous systems where reactants are continuously fed into one end of the reactor and products are continuously withdrawn from the other. They are characterized by a steady-state operation and minimal back-mixing [35].

Flow systems offer several distinct advantages, particularly for reaction scalability. Once a reaction is optimized at a small scale in a flow system, it is often easier to scale up production simply by running the reactor for a longer period, a concept known as "numbering up" [35]. They also provide superior heat and mass transfer capabilities, making them excellent for highly exothermic reactions or reactions involving gaseous reagents [35]. Furthermore, they enable unique chemical pathways, such as the use of short-lived intermediates, and facilitate inline purification and analysis, supporting fully continuous, integrated processes [20].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: Batch vs. Flow Reactor Configurations

| Parameter | Batch Reactor | Flow Reactor (e.g., PFR) |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Mode | Closed system, unsteady-state [33] | Continuous feed, steady-state [35] |

| Residence Time | Fixed time per batch; determined by kinetics [33] | Determined by flow rate and reactor volume [35] |

| Scalability | Scale-up requires larger vessels; can pose heat/mass transfer challenges | Easier scalability through "numbering up"; consistent performance [35] |

| Heat/Mass Transfer | Can be limited by stirring and vessel size; potential for hot spots | Excellent due to high surface-to-volume ratio [35] |

| Flexibility & Versatility | High; suitable for complex, multi-step reactions and exploratory chemistry [3] [34] | Lower per reactor; often dedicated to a specific reaction type |

| Process Intensity | Low to moderate | High |

| Automation Integration | Ideal for parallel synthesis of different compounds [20] | Ideal for continuous, integrated production of a single compound |

Experimental Protocols for Automated Synthesis

Implementing automated synthesis requires robust experimental protocols that leverage the capabilities of robotic hardware and reactor systems. The following methodologies illustrate key applications.

Protocol for Autonomous Exploratory Synthesis Using Mobile Robots

This protocol, adapted from a published workflow for supramolecular and structural diversification chemistry, uses mobile robots for general exploratory synthesis [3].

- Workflow Setup: A modular platform is established with physically separated synthesis (Chemspeed ISynth) and analysis (UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR) modules. Mobile robots are configured for sample transport between modules.

- Reaction Execution: The automated synthesizer is instructed to perform the parallel synthesis of a compound library (e.g., attempting the synthesis of three ureas and three thioureas through combinatorial condensation).

- Automated Sampling and Reformating: Upon reaction completion, the synthesizer automatically takes an aliquot of each reaction mixture and reformats it separately for MS and NMR analysis.

- Sample Transport and Analysis: Mobile robots transport the prepared samples to the respective instruments (UPLC-MS and NMR). Data acquisition is performed autonomously via customizable Python scripts, and results are saved to a central database.

- Heuristic Decision-Making: A heuristic decision-maker, pre-programmed with experiment-specific pass/fail criteria by a domain expert, processes the orthogonal UPLC-MS and NMR data. It assigns a binary grade to each reaction.

- Autonomous Progression: Based on the decision-maker's output (e.g., reactions must pass both analyses), the system autonomously instructs the synthesizer on the next set of experiments, such as scaling up successful reactions for further elaboration.

Protocol for High-Throughput Substrate Scope Screening in Batch

This protocol utilizes an LLM-based reaction development framework (LLM-RDF) to lower the barrier for high-throughput screening (HTS) in batch reactors [9].

- Experiment Design: The Experiment Designer agent, prompted by a natural language request from a chemist, designs the HTS experiment. This includes selecting a diverse set of substrates and formulating reaction conditions based on literature data.

- Automated Execution: The Hardware Executor agent translates the experimental design into machine-readable instructions for an automated HTS platform, which executes the parallel batch reactions in open-cap vials or well-plates.

- Analysis and Interpretation: Reaction outcomes are monitored, for example, by gas chromatography (GC). The Spectrum Analyzer agent processes the raw chromatographic data. The Result Interpreter agent then analyzes the processed data to determine reaction success (e.g., conversion, yield) and identifies trends in the substrate scope.

- Iteration: The interpreted results can be fed back to the Experiment Designer to plan subsequent iterative rounds of screening or optimization.

System Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflows and architectural relationships in automated synthesis platforms.

Workflow for Autonomous Robotic Synthesis

Diagram Title: Autonomous Robotic Synthesis Workflow

LLM-Agent Driven Screening Workflow

Diagram Title: LLM-Agent Driven Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of automated synthesis, particularly with cartridge-based systems, relies on specialized reagents and materials designed for integration with robotic platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

| Reagent Solution / Material | Function in Automated Synthesis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-packed Reagent Cartridges | Contains precise quantities of reagents for specific reaction types [31]. | Enables "kit-based" workflow; eliminates manual weighing; ensures reproducibility and saves time. |

| Pre-weighted Building Blocks | Cherry-picked compounds from a vendor's stock for custom library synthesis [30]. | Reduces labor-intensive in-house weighing and dissolution; minimizes errors; shipped rapidly. |

| Virtual Building Block Catalogues | Vast collections of synthesizable compounds not held in physical stock (e.g., Enamine MADE) [30]. | Drastically expands accessible chemical space; relies on pre-validated synthetic protocols. |

| Solid Supported Reagents | Reagents immobilized on an insoluble polymer matrix. | Simplifies workup and purification via filtration; amenable to flow chemistry [31]. |

| Customized Catalyst Systems | Highly engineered catalysts for use in catalytic reactors [35]. | Optimized pore structure and surface area for improved reaction rates and selectivity. |

| AGI-24512 | AGI-24512, MF:C24H24N4O2, MW:400.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ROCK-IN-11 | ROCK-IN-11, MF:C22H20N4O4S, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of AI and Synthesis Planning Software (CASP)

In modern organic chemistry research, an automated synthesis platform is an integrated system that combines computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) software, robotic laboratory equipment, and advanced data analytics to accelerate the design and execution of chemical synthesis. These platforms represent a paradigm shift from traditional, labor-intensive chemical research to a data-driven, automated workflow [36]. The core function of such a platform is to address the critical bottleneck in fields like drug discovery: while AI can rapidly design promising molecules, the physical creation of these compounds often remains slow and resource-intensive [37]. By leveraging artificial intelligence, these systems can predict viable synthetic routes, optimize reaction conditions, and physically carry out chemical reactions with minimal human intervention, thereby dramatically increasing the speed and efficiency of molecular construction [38].

The integration of AI and automation is transforming organic chemistry from an artisanal practice reliant on expert intuition and trial-and-error into an engineering discipline characterized by predictability, reproducibility, and high throughput [36]. This transformation is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, where the ability to rapidly synthesize and test target compounds can significantly shorten the timeline for bringing new therapeutics to market [24].

Core Components of an Automated Synthesis Platform

An automated synthesis platform is a sophisticated ecosystem comprising several interconnected technological components. Each plays a vital role in the seamless operation of the end-to-end process, from digital design to physical molecule.

AI-Powered Synthesis Planning Software (CASP)

The "brain" of the platform is the Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) software. Modern CASP tools utilize advanced AI algorithms to perform retrosynthetic analysis, deconstructing a target molecule into progressively simpler precursors until commercially available starting materials are identified [36]. These systems primarily operate using two methodological approaches: