Automated vs Manual Substrate Scope Evaluation: Accelerating Discovery in Drug Development

Evaluating substrate scope is a critical, yet resource-intensive step in drug discovery and development.

Automated vs Manual Substrate Scope Evaluation: Accelerating Discovery in Drug Development

Abstract

Evaluating substrate scope is a critical, yet resource-intensive step in drug discovery and development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern automated methods, such as High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and AI-driven platforms, in contrast to traditional manual approaches. We explore the foundational principles of substrate scope assessment, detail the workflow integration and practical applications of automated systems, address key troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and present rigorous validation and comparative frameworks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how digitalization and automation are overcoming traditional bottlenecks, enhancing data quality, and accelerating the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle, ultimately paving the way for more efficient and predictive discovery pipelines.

Defining Substrate Scope: Core Concepts and Challenges in Modern Chemistry

The Critical Role of Substrate Scope in SAR and Lead Optimization

In the rigorous journey from a bioactive hit to a clinically viable drug candidate, understanding and exploiting Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) is paramount. A central, yet sometimes underappreciated, component of SAR analysis is the comprehensive evaluation of a compound's substrate scope—the range of structurally related analogs that can be synthesized, tested, and iteratively optimized to improve key properties such as potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics. This guide compares the experimental and computational methodologies for exploring substrate scope, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of evaluating automated versus manual approaches in modern drug discovery.

The Imperative for Broad Substrate Scope Exploration

Natural products (NPs) and synthetic hits alike rarely possess ideal drug-like properties from the outset [1]. Their optimization requires systematic modification, which hinges on the ability to generate diverse analogs (i.e., a broad substrate scope) to map the SAR landscape [1]. Traditionally, this has been the domain of manual, hypothesis-driven medicinal chemistry. However, the rise of automated and computational platforms promises to accelerate this mapping by rationally guiding synthetic efforts or virtually exploring chemical space [2] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Paradigms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of primary approaches for expanding substrate scope in SAR campaigns.

Table 1: Comparison of Substrate Scope Exploration Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Typical Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diverted Total Synthesis [1] | Chemical synthesis from common intermediates to generate diverse core analogs. | Enables deep-seated, non-trivial modifications to complex scaffolds. | Time-consuming, resource-intensive, requires expert synthetic design. | Discrete analogs for bioassay; qualitative SAR trends. |

| Late-Stage & Semisynthesis [1] | Functionalization of a natural or advanced synthetic intermediate. | More efficient than total synthesis; good for exploring peripheral modifications. | Limited to chemically accessible sites on the pre-formed core. | Focused libraries; localized SAR data. |

| Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) Engineering [1] | Genetic manipulation of microbial pathways to produce natural product variants. | Accesses "evolutionarily pre-screened" chemical space; can produce challenging analogs. | Limited to biosynthetically tractable changes; host-dependent yields. | Natural product analogs; insights into biosynthetic SAR. |

| DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Screening [4] | Combinatorial synthesis of vast libraries tethered to DNA tags for affinity selection. | Ultra-high-throughput experimental screening of billions of compounds. | Hits often require significant optimization (truncation, linker removal); property ranges can be broad [4]. | Enriched hit sequences; initial structure-property data of binders. |

| Computational In Silico Screening & Modeling [2] [5] | Use of docking, pharmacophore models, or ML to predict activity and guide synthesis. | Rapid, low-cost virtual exploration of vast chemical space; provides rational design hypotheses. | Dependent on model accuracy and training data; requires experimental validation. | Predicted active compounds; prioritized synthetic targets; QSAR models. |

| Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) [3] | Closed-loop automation integrating robotics, AI planning, and automated analysis. | Accelerates empirical optimization cycles; reduces human labor and bias. | High initial integration complexity; currently limited to defined reaction schemes or formulations [3]. | Optimized reaction conditions or material properties; high-throughput experimental SAR. |

The molecular property evolution from hit to lead offers a clear metric for comparing outcomes. An analysis of DNA-encoded library (DEL) campaigns shows that while initial DEL hits tend toward higher molecular weight (MW ~533) compared to High-Throughput Screening (HTS) hits (MW ~410), the optimizable subset undergoes property refinement. Successful leads from DEL hits showed consistent improvements in efficiency metrics like Ligand Efficiency (LE) and Lipophilic Ligand Efficiency (LLE), even as absolute MW and cLogP changes varied, indicating diverse successful optimization tactics such as truncation or polarity addition [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Protocol for Divergent Synthesis in SAR Studies (Based on Migrastatin Analogs) [1]

- Objective: To systematically generate a library of complex natural product analogs with variations at multiple sites to study antitumor activity.

- Methodology:

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Identify key strategic bond disconnections in the target NP (e.g., Migrastatin) that lead to a common synthetic intermediate.

- Intermediate Diversification: Design synthetic routes from this common intermediate that allow for the incorporation of different building blocks at designated diversification points.

- Parallel Synthesis: Execute the divergent synthetic pathways in parallel to produce the target analog library.

- Purification & Characterization: Purify all analogs to homogeneity using chromatographic techniques (e.g., HPLC). Characterize structures using NMR and high-resolution mass spectrometry.

- Biological Evaluation: Test all analogs in relevant bioassays (e.g., cell migration or proliferation assays) to generate biological data.

- Outcome: A set of structurally defined analogs enabling the construction of a detailed SAR matrix, identifying regions critical for activity and those amenable to modification for improving stability or reducing toxicity [1].

2. Protocol for Machine Learning-Guided Substrate Scope Prediction (ESP Model) [5]

- Objective: To predict novel enzyme-substrate pairs across diverse enzyme families, virtually expanding the substrate scope for biocatalysis or target engagement studies.

- Methodology:

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of experimentally confirmed enzyme-substrate pairs from public databases (e.g., UniProt). Use only high-confidence, experimentally validated pairs for core training data [5].

- Negative Data Augmentation: For each positive pair, sample small molecules structurally similar (Tanimoto similarity 0.75-0.95) to the true substrate from a curated metabolite pool to create putative negative examples [5].

- Feature Representation:

- Enzymes: Encode protein amino acid sequences using a task-specific fine-tuned transformer model (e.g., modified ESM-1b) to generate informative numerical embeddings [5].

- Substrates: Encode small molecules using graph neural networks (GNNs) to generate molecular fingerprints capturing structural and functional features [5].

- Model Training: Train a gradient-boosted decision tree model (e.g., XGBoost) on the combined enzyme and substrate feature vectors to classify pairs as likely substrates or non-substrates.

- Validation & Prediction: Validate model accuracy on a held-out test set of known pairs. Use the trained model to score new enzyme-small molecule combinations, generating a ranked list of predicted novel substrates for experimental testing.

- Outcome: A predictive tool that identifies plausible substrate candidates, focusing experimental characterization efforts and revealing non-obvious aspects of enzyme promiscuity and SAR [5].

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow

The most effective SAR strategies integrate computational and experimental approaches in a feedback loop [1]. The following diagram illustrates this synergistic workflow for substrate scope exploration and lead optimization.

Diagram 1: Integrated SAR Exploration Feedback Loop

Diagram 2: Spectrum of Substrate Scope Research Methods

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Substrate Scope and SAR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in SAR Studies | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Diversified Building Block Libraries | Provide the chemical variety to instantiate a broad substrate scope during synthesis. | Used in diverted total synthesis or DEL construction to introduce structural diversity at designated points [1] [4]. |

| Engineered Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) | Act as biological "factories" to produce natural product analogs that may be synthetically challenging. | Mining and engineering BGCs to generate new NP variants for biological testing and SAR analysis [1]. |

| DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries | Serve as a source of ultra-high-diversity hit compounds with linked genotype-phenotype information. | Screening billions of compounds against a protein target to identify initial hit chemotypes and preliminary SAR [4]. |

| ESP-type Machine Learning Model [5] | A computational tool to predict enzyme-substrate relationships, virtually expanding testable substrate scope. | Prioritizing which potential substrate analogs to synthesize or which enzymes might process a novel scaffold. |

| Curated Bioactivity Datasets | Provide the essential ground-truth data for training predictive QSAR or ML models. | Used to train models like ESP or other CADD tools to recognize patterns linking chemical structure to biological activity [5]. |

The critical path in lead optimization is paved by the breadth and intelligence of substrate scope exploration. While traditional synthetic methods provide depth and certainty for specific scaffolds, automated and computational methods—from DELs and ML predictions to the emerging paradigm of self-driving labs—offer unprecedented breadth and speed [3] [4] [5]. The future of efficient SAR analysis does not lie in choosing one paradigm over the other but in strategically integrating them. A synergistic workflow, where computational models prioritize targets for focused manual synthesis and experimental data continuously refines predictive algorithms, represents the most powerful toolkit for researchers and drug developers to navigate the complex SAR landscape and accelerate the delivery of optimized drug candidates [1].

In the modern drug discovery landscape, the medicinal chemist remains indispensable, with chemical intuition and deep literature knowledge forming the cornerstone of the design and development process. This expertise, built on experience and human cognition, is the primary driver for discovering leads and optimizing them into clinically useful drug candidates [6]. While technological advancements provide powerful tools, the chemist's ability to creatively process large sets of chemical descriptors, pharmacological data, and pharmacokinetic parameters is irreplaceable [6]. This guide objectively evaluates the performance of these traditional, expert-driven methods, framing the analysis within the critical research context of evaluating substrate scope across different methodological approaches.

Core Comparison: Manual vs. Automated Methodologies

The choice between manual and automated methods is not about selecting a universally "better" option, but rather about understanding two different paradigms, each with distinct strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases [7]. The following comparison outlines their fundamental characteristics.

Table 1: Head-to-Head Comparison of Manual and Automated Experimental Methods

| Feature | Traditional Manual Methods | Automated Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Driver | Human expert (Medicinal Chemist) [6] | Software & Robotics [7] |

| Primary Strength | Creativity, adaptability, and discovery of complex, novel solutions [7] [6] | Speed, scalability, and reproducibility [7] |

| Key Weakness | Labor-intensive, slower, and subject to individual experience [7] | Lacks contextual awareness and cannot understand business logic or chemical intuition [7] [6] |

| Optimal Use Case | Lead optimization, understanding SAR, and tackling unprecedented chemical problems [6] | High-throughput screening, routine checks, and generating large-scale baseline data [7] |

| Data Output | Deep, context-aware insights with minimal false positives [7] | Broad, signature-based data that often requires manual validation of false positives [7] |

| Cost & Time Profile | High cost and time investment per experiment [7] | High initial setup, but low marginal cost and time per experiment after [7] |

Quantitative Data: Performance and Variability

Quantitative comparisons from related scientific fields highlight critical differences in output and reliability between manual and automated techniques. These findings underscore the importance of methodological choice based on the desired outcome.

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparison from Segmentation Studies

| Metric | Manual Segmentation | Automated Segmentation | Relative Percentage Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain SUVmean | 4.19 ± 0.02 [8] | 5.99 ± 0.03 [8] | +30.05% [8] |

| Brain SUVmax | 10.76 ± 0.06 [8] | 11.75 ± 0.07 [8] | +8.43% [8] |

| Cerebellum SUVmean | 6.00 ± 0.03 [8] | 5.47 ± 0.02 [8] | -9.69% [8] |

| Cerebellum SUVmax | 8.23 ± 0.04 [8] | 9.20 ± 0.04 [8] | +10.54% [8] |

| IHC Analysis (κ statistic) | Human Observer Baseline [9] | ScanScope XT vs. Observer [9] | κ = 0.855 - 0.879 [9] |

| IHC Analysis (κ statistic) | Human Observer Baseline [9] | ACIS III vs. Observer [9] | κ = 0.765 - 0.793 [9] |

Experimental Protocols in Detail

Protocol for Manual Analysis in Medicinal Chemistry

The manual process led by a medicinal chemist is an objective-driven, iterative cycle of design and analysis [6].

- Hypothesis Generation: The chemist develops a testable hypothesis based on chemical intuition, prior experience, and a comprehensive review of the scientific literature [6].

- Compound Design & Synthesis: A lead compound is designed, often by analoging from known substrates, and synthesized manually or in small batches.

- Biological Testing: The synthesized compound undergoes targeted in vitro and in vivo assays to determine its activity, potency, and selectivity.

- Data Analysis & SAR Establishment: The chemist analyzes the results to establish a Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR), using their expertise to interpret nuances and outliers that automated systems might miss [6].

- Iterative Optimization: The cycle repeats, with the chemist using the newly gained insights to refine the hypothesis and design the next, improved compound [6].

Protocol for Automated High-Throughput Experimentation

Automated methods follow a standardized, linear workflow designed for maximum throughput and reproducibility [10].

- Library Design & Plate Mapping: A large library of candidate materials or compounds is designed and mapped onto multi-well plates using computational planning tools.

- Robotic Dispensing & Synthesis: Robotic liquid handlers and automated synthesizers prepare or plate the compounds into the predefined array format with minimal human intervention [10].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): The entire library is subjected to parallelized assays, often using automated readouts like fluorescence or absorbance.

- Data Collection & Primary Analysis: Instrument software automatically collects raw data (e.g., intensity values) and performs initial processing (e.g., normalization, background subtraction).

- Hit Identification: Results are analyzed against predefined activity thresholds to identify "hits" for further investigation.

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points in the manual, intuition-driven drug discovery process.

Diagram 1: Manual Drug Discovery Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential reagents and materials central to conducting experimental research in this field, particularly within a manual or traditional methodology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Core Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Microarray (TMA) | Enables high-throughput evaluation of protein expression across hundreds of tissue samples on a single slide, maximizing reproducibility [9]. | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) detection of differential antigen expression in cancer samples [9]. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Antibodies | Detect spatial and temporal localization of specific antigens (e.g., pAKT, pmTOR) in preserved tissue samples [9]. | Determining tumor progression and aggressiveness by visualizing protein expression patterns [9]. |

| Common Solvents (DMSO, etc.) | Universal solvents for dissolving chemical compounds for in vitro biological testing and stock solution preparation. | Creating millimolar stock solutions of novel lead compounds for cell-based assays. |

| Cell Culture Media & Reagents | Provide the necessary nutrients and environment to maintain cell lines for in vitro toxicity and efficacy testing. | Growing cancer cell lines to test the cytotoxic effects of newly synthesized molecules. |

| Radioactive Tracers (e.g., ¹⁸F-FDG) | Allow for the sensitive quantification of metabolic activity and target engagement in biological systems using PET/CT [8]. | Measuring metabolic changes in brain tumors in response to drug treatment [8]. |

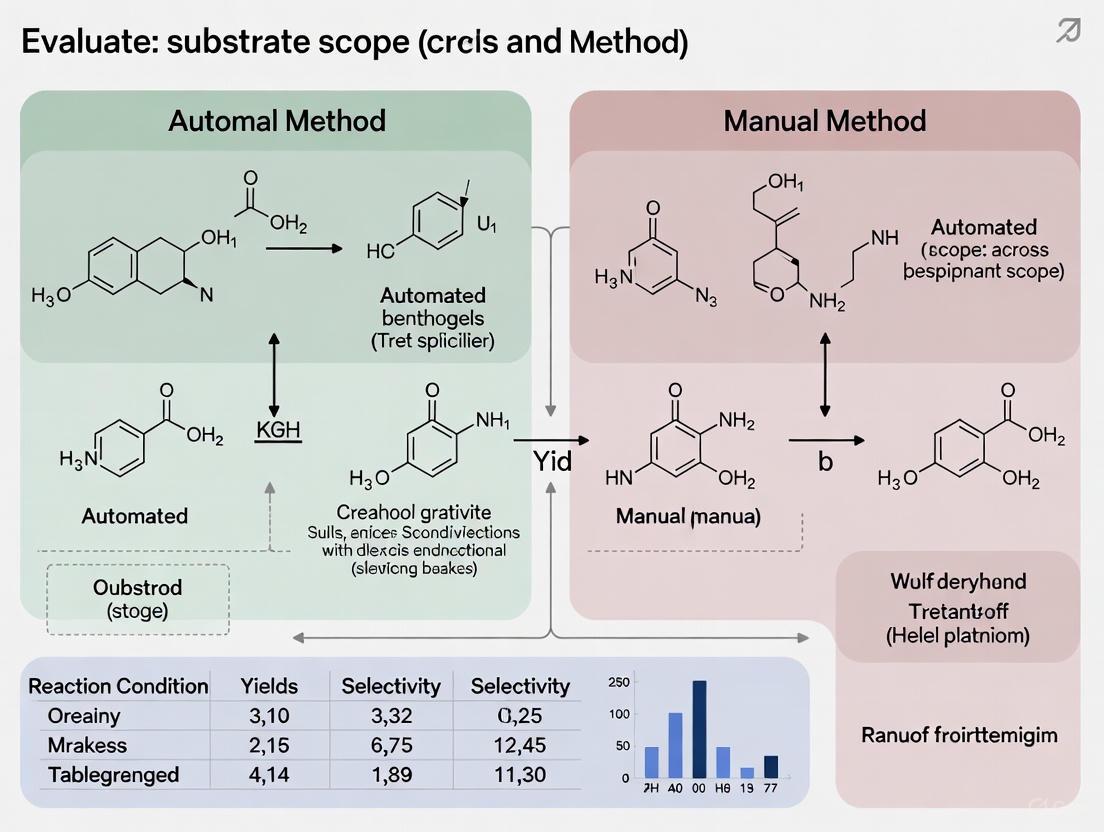

The Synthesis Bottleneck in the Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) Cycle

The "Make" phase, dedicated to compound synthesis, is widely recognized as the primary bottleneck in the iterative Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle for drug discovery [11] [12]. This stage is often manual, labor-intensive, and low-throughput, creating a significant drag on the pace of research. A critical part of this synthetic challenge is establishing the substrate scope of a reaction—understanding which substrates a protocol can and cannot be applied to. The methodologies for this evaluation are rapidly evolving, shifting from traditional, biased manual approaches to more standardized, data-driven automated strategies [13].

Traditional vs. Standardized Substrate Scope Evaluation

The conventional process for evaluating a reaction's substrate scope has been largely manual. A chemist selects a series of substrates believed to demonstrate the reaction's utility, often based on commercial availability and an expectation of high yield [13]. This approach introduces two significant biases:

- Selection Bias: The tendency to prioritize substrates that are easily accessible or predicted to perform well [13].

- Reporting Bias: The common practice of omitting low-yielding or unsuccessful results from publications [13].

These biases limit the expressiveness of scope tables and reduce chemist confidence in a method's true generality and limitations [13]. Consequently, many newly published reactions never transition to industrial application [13].

A modern, standardized strategy leverages unsupervised machine learning to mitigate these biases. This method involves mapping the chemical space of industrially relevant molecules (e.g., from the Drugbank database) using an algorithm like UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) [13]. Potential substrate candidates are then projected onto this universal map, enabling the selection of a minimal, structurally diverse set of substrates that optimally represent the broader chemical space of interest. This data-driven selection provides a more objective and comprehensive benchmark of a reaction's applicability and limits [13].

Table 1: Core Comparison of Manual vs. Standardized Substrate Scope Evaluation

| Feature | Traditional Manual Approach | Standardized Data-Driven Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Basis | Chemical intuition, expected yield, & commercial availability [13] | Unsupervised learning & diversity maximization within a defined chemical space (e.g., drug-like space) [13] |

| Inherent Biases | High (Selection and Reporting bias) [13] | Low (Algorithmically driven to minimize bias) [13] |

| Primary Goal | Showcase successful applications and robustness [13] | Unbiased evaluation of general applicability and discovery of limitations [13] |

| Number of Substrates | Often large and redundant (20-100+) [13] | Small and highly representative (e.g., ~15) [13] |

| Information Gained | Limited expressiveness of true generality [13] | Broad knowledge of reactivity trends with minimal experiments [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

The following protocols detail how both manual and automated methodologies are typically executed in a research setting, focusing on the critical "Make" phase for substrate scope analysis.

Protocol 1: Manual Substrate Scope Evaluation

This traditional protocol relies heavily on the chemist's expertise for the design, execution, and analysis of reactions.

- Literature & Database Search: The chemist manually searches databases like SciFinder and Reaxys for relevant reaction precedents and commercially available substrate candidates [11].

- Substrate Selection: A set of substrates is chosen based on the chemist's knowledge of steric, electronic, and functional group properties, often influenced by availability and predicted success [13].

- Reaction Setup: Reactions are typically set up in parallel but manually in individual reaction vessels (e.g., vials or round-bottom flasks) [14].

- Execution & Monitoring: The reactions are run and monitored serially, often using techniques like Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LCMS). Throughput is limited by LCMS run times, which can be over one minute per sample [12].

- Work-up & Purification: Each reaction is worked up (quenched, extracted, concentrated) and purified manually, using techniques like flash chromatography. This is a major time sink [14].

- Analysis & Characterization: The purified products are characterized (e.g., NMR, LCMS) to confirm structure and yield, and the results are documented [11].

Protocol 2: Automated & Standardized Substrate Scope Evaluation

This modern protocol integrates automation and machine learning at key stages to increase throughput and reduce bias.

- Algorithmic Substrate Selection:

- A broad list of potential substrates is compiled from supplier catalogs.

- A pre-trained UMAP model, built on a relevant chemical space (e.g., drug molecules), projects these candidates onto a diversity map [13].

- A clustering algorithm (e.g., Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering) selects a defined number of substrates (e.g., 15) from different clusters to ensure maximal diversity and representation [13].

- High-Throughput Experimental (HTE) Setup: Automated liquid handlers are used to dispense substrates, reagents, and catalysts into well plates (e.g., 96- or 384-well format), executing the reaction setup in parallel [12].

- Rapid Reaction Analysis: Instead of serial LCMS, high-throughput analysis techniques are employed. For example, direct mass spectrometry methods can analyze samples in approximately 1.2 seconds each, allowing a 384-well plate to be analyzed in about 8 minutes [12].

- Integrated Purification & Analysis: Automated purification systems, such as flash chromatography systems, are linked with the synthesis platform to streamline the process between "Make" and "Analyze" [12].

- Data Integration & Model Refinement: All experimental outcomes—successes and failures—are recorded in a FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) database. This data is used to refine predictive AI models for future cycles, creating a continuous learning loop [11].

Workflow Comparison & System Integration

The diagrams below illustrate the logical flow and key decision points for the traditional and modern automated substrate evaluation workflows.

Workflow Comparison: Manual vs. Automated Substrate Evaluation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The shift towards automated and data-driven substrate evaluation relies on a suite of computational and hardware tools.

Table 2: Essential Tools for Modern Substrate Scope Research

| Tool / Solution | Function | Role in Substrate Scope Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) | A non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithm for visualizing and clustering high-dimensional data [13]. | Maps the chemical space of drug-like molecules to enable unbiased, diverse substrate selection [13]. |

| Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) | A class of molecular fingerprints that capture circular atom environments in a molecule, encoding substructural information [13]. | Featurizes molecules into a numerical representation that UMAP and other ML models can process [13]. |

| Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) | AI-powered software that uses retrosynthetic analysis and machine learning to propose viable synthetic routes for target molecules [11] [15]. | Accelerates the "Make" step by generating synthetic pathways for the diverse substrates selected for scope testing [11]. |

| Quantitative Condition Recommendation Models (e.g., QUARC) | Data-driven models that predict not only chemical agents but also quantitative details like temperature and equivalence ratios [15]. | Provides executable reaction conditions for proposed synthetic routes, bridging the gap between planning and automated execution [15]. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Robots | Hardware systems that automate the dispensing of liquids into well plates [12]. | Enables high-throughput, parallel setup of numerous substrate scope reactions, increasing throughput and reproducibility [12]. |

| Direct Mass Spectrometry | An analytical technique that bypasses chromatography to directly introduce samples into a mass spectrometer [12]. | Drastically reduces analysis time per sample (to ~1.2 seconds), enabling near-real-time feedback on reaction success/failure in HTS campaigns [12]. |

The synthesis bottleneck in the DMTA cycle, particularly the evaluation of substrate scope, is being addressed through a fundamental shift from manual, experience-driven processes to integrated, data-driven, and automated workflows. The move towards standardized substrate selection using unsupervised learning mitigates long-standing biases and provides a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of a reaction's utility [13]. When this is combined with automated synthesis and rapid analysis platforms [12], and powered by predictive AI models for synthesis planning and condition recommendation [11] [15], the "Make" phase is transformed from a major bottleneck into a rapid, informative, and iterative component of modern drug discovery.

In the evaluation of substrate scope—a fundamental step in chemical reaction development and drug discovery—researchers have traditionally relied on manual experimentation. However, the emergence of automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) presents a powerful alternative. This guide objectively compares these two approaches, focusing on the critical challenges of time, cost, and reproducibility, and is supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

The following table summarizes the core differences between manual and automated scoping across the key challenges.

| Challenge | Manual Scoping | Automated (HTE) Scoping |

|---|---|---|

| Time | Time-intensive, sequential testing; low throughput [16] | Rapid, parallel execution; high throughput [16] [17] |

| Experimental Duration | Days to weeks for a full substrate scope [16] | Hours to days for the same scope [17] |

| Cost | Lower initial investment; higher long-term labor costs [18] | High initial capital outlay; lower cost-per-data-point long-term [17] [18] |

| Reproducibility | Prone to human error and procedural drift [19] [20] | High precision and consistency; minimizes human variability [19] [17] |

| Data Quality | Subject to inconsistent record-keeping [21] | Inherently structured, machine-readable data supporting FAIR principles [17] |

Experimental Data: A Quantitative Comparison

Case Study: Isolation of Mononuclear Cells (MNCs)

A study directly comparing manual and automated methods for isolating MNCs from bone marrow—a critical step in obtaining Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs)—provides concrete, quantitative data on efficacy and reproducibility [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Source: 17 bone marrow samples from patients aged 18-65.

- Manual Method: Density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS in 50 mL tubes. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 300g and 21°C. The MNC layer was carefully collected and washed [19].

- Automated Method: The same density gradient separation was performed using the Sepax S-100 automated cell processing system with the DGBS/Ficoll CS-900 kit [19].

- Downstream Analysis: Isolated MNCs from both methods were cultured to obtain MSCs. Analyses included cell counting (Sysmex XN-20), colony-forming unit (CFU) assays, and phenotypic characterization [19].

Results Summary:

| Metric | Manual Isolation | Automated Isolation (Sepax) |

|---|---|---|

| MNC Yield | Baseline for comparison | Slightly higher [19] |

| CFU Formation | Standard yield | No significant difference [19] |

| MSC Characteristics (Phenotype, Differentiation) | Standard quality | No significant difference [19] |

| Key Reproducibility Note | Subject to technician skill and consistency | Enhanced process control and consistency under GMP conditions [19] |

The experimental data shows that while automation can improve yield and reproducibility, both methods are capable of producing cells with equivalent biological functionality.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure clarity and practical utility, here are the detailed methodologies for both manual and automated approaches as applied in chemical substrate scoping.

Protocol 1: Manual Substrate Scoping

This traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach is the baseline for comparison [17].

- Reaction Setup: A chemist sets up individual reactions sequentially in round-bottom flasks or vials. For each substrate, the specific quantities of substrate, catalyst, ligand, and solvent are measured and added using manual pipettes or syringes.

- Reaction Execution: Each reaction vessel is placed on a separate hot/stir plate or in an individual heating block. The reaction is allowed to proceed for the designated time.

- Workup and Quenching: Reactions are quenched manually one-by-one, often by adding a quenching solvent or aqueous solution.

- Analysis: Each sample is prepared for analysis (e.g., by dilution) and analyzed sequentially via techniques like Gas Chromatography (GC) or Liquid Chromatography (LC).

- Data Recording: The chemist manually records yields and observations in a laboratory notebook or spreadsheet.

Protocol 2: Automated High-Throughput Substrate Scoping

This protocol leverages automation and miniaturization for parallel processing [16] [17].

- Experimental Design: An "Experiment Designer" agent or software is used to define the array of substrates and conditions to be tested in a microtiter plate (MTP) format [16].

- Liquid Handling: An automated liquid handler (e.g., Hamilton, Beckman Coulter) dispenses nanoliter to microliter volumes of substrates, catalysts, and solvents into the wells of an MTP.

- Reaction Execution: The entire MTP is placed in a single, environmentally controlled unit (e.g., an agitator/heater) that ensures uniform temperature and stirring for all reactions simultaneously.

- Automated Quenching & Analysis: The MTP is transferred to an automated system that quenches all reactions in parallel. An autosampler (e.g., a robotic pallet) then introduces the samples sequentially into a high-speed GC-MS or LC-MS for analysis.

- Data Processing: A "Result Interpreter" or data analysis software automatically processes the chromatographic data, calculates yields or conversion rates, and compiles the results into a structured database or spreadsheet [16].

Workflow Visualization

The diagrams below illustrate the logical flow and key decision points for both manual and automated scoping methodologies.

Diagram 1: Manual Scoping Workflow

Diagram 2: Automated Scoping Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and instruments used in automated high-throughput scoping campaigns, as referenced in the experimental data.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (MTP) | The foundational platform for miniaturized, parallel reactions, typically with 96, 384, or 1536 wells [17]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precisely dispenses nanoliter to microliter volumes of reagents and substrates into MTP wells, enabling high-speed, accurate setup [16] [17]. |

| Ficoll-Paque PLUS | Density gradient medium used for the isolation of mononuclear cells (MNCs) from bone marrow or blood samples in biological studies [19]. |

| High-Throughput GC-MS/LC-MS | Analytical instruments equipped with autosamplers to rapidly analyze dozens to hundreds of samples from an MTP with minimal delay [16] [17]. |

| Sepax S-100 System | An automated, closed-system cell processor used for the reproducible isolation of cells under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions [19]. |

| LLM-Based Agents (e.g., Experiment Designer) | Artificial intelligence agents that assist in designing HTE campaigns, interpreting complex spectral data, and recommending next steps [16]. |

The evidence demonstrates that manual and automated scoping methods are not simply replacements for one another but represent different tools for different phases of research. Manual methods retain value for early-stage, exploratory work with low initial costs. However, for comprehensive, reproducible, and efficient substrate scope evaluation—particularly in contexts like drug development where data quality and speed are paramount—automated HTE offers a transformative advantage. The integration of AI and robotics is steadily reducing the barriers to adoption, making robust, data-driven reaction evaluation an increasingly accessible standard for researchers [16] [22] [17].

Implementing Automation: HTE, AI, and Multiplexed Platforms in Action

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) represents a fundamental shift in research methodology, leveraging miniaturization and parallelization to accelerate scientific discovery. This approach utilizes lab automation, specialized equipment, and informatics to conduct large numbers of experiments rapidly and efficiently [23]. Within drug discovery and materials science, HTE has transformed traditional sequential, manual processes into highly parallelized, automated workflows, enabling the evaluation of thousands of experimental conditions in the time previously required for a handful [24]. This guide objectively compares the performance of automated HTE methodologies against conventional manual techniques, focusing on critical parameters such as throughput, reproducibility, data quality, and resource utilization. The evaluation is framed within the essential research context of assessing substrate scope—a task where the comprehensive and reliable data provided by HTE is indispensable for drawing meaningful conclusions about reactivity and function across diverse chemical or biological space.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

The superiority of automated HTE systems over manual methods is demonstrated across multiple performance metrics. The following tables summarize quantitative comparisons from key experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Automated vs. Manual IHC Analysis in Tissue Microarray Evaluation

| Analysis Method | Parameter Measured | Correlation/Agreement (κ index) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ScanScope XT (Aperio) | % Positive Pixels/Nuclei | κ = 0.855 - 0.879 vs. observers | Good correlation with human observers [9] |

| ACIS III (Dako) | % Positive Pixels/Nuclei | κ = 0.765 - 0.793 vs. observers | Satisfactory correlation with human observers [9] |

| ScanScope XT (Aperio) | Labeling Intensity (pAKT, pmTOR) | Correlation Index: 0.851 - 0.946 | Better intensity identification than ACIS III [9] |

| ACIS III (Dako) | Labeling Intensity (pAKT) | Correlation Index: 0.680 - 0.718 | Variable correlation with human observers [9] |

| ACIS III (Dako) | Labeling Intensity (pmTOR) | Correlation Index: ~0.225 | Poor correlation in some cases [9] |

| Manual Observation | Inter-observer Variability | Inherently subjective and time-consuming | Baseline for comparison [9] |

Table 2: Impact of Sample Size (Replicates) on Parameter Estimation in Simulated qHTS Data

| True AC50 (μM) | True Emax (%) | Number of Replicates (n) | Mean & [95% CI] for AC50 Estimates | Mean & [95% CI] for Emax Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | 25 | 1 | 7.92e-05 [4.26e-13, 1.47e+04] | 1.51e+03 [-2.85e+03, 3.1e+03] |

| 0.001 | 25 | 3 | 4.70e-05 [9.12e-11, 2.42e+01] | 30.23 [-94.07, 154.52] |

| 0.001 | 25 | 5 | 7.24e-05 [1.13e-09, 4.63] | 26.08 [-16.82, 68.98] |

| 0.001 | 100 | 1 | 1.99e-04 [7.05e-08, 0.56] | 85.92 [-1.16e+03, 1.33e+03] |

| 0.001 | 100 | 5 | 7.24e-04 [4.94e-05, 0.01] | 100.04 [95.53, 104.56] |

| 0.1 | 50 | 1 | 0.10 [0.04, 0.23] | 50.64 [12.29, 88.99] |

| 0.1 | 50 | 5 | 0.10 [0.06, 0.16] | 50.07 [46.44, 53.71] |

Table 3: Operational Efficiency Gains from HTE Automation and Miniaturization

| Performance Metric | Manual Methods | Automated HTE Methods | Reference/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispensing Speed (96-well plate) | Minutes (manual pipetting) | ~10 seconds | I.DOT Liquid Handler [24] |

| Dispensing Speed (384-well plate) | >10 minutes | ~20 seconds | I.DOT Liquid Handler [24] |

| Liquid Handling Volume | Microliter range, higher error | Nanoliter range (e.g., 10 nL), precise | Enables miniaturization [24] |

| Data Reproducibility | Subject to intra-/inter-observer variability | High, not subject to human fatigue | κ > 0.75 with observers [9] |

| Reagent Conservation | Higher volumes, more waste | Up to 50% savings | I.DOT Liquid Handler [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Automated Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Analysis for Protein Expression

This protocol, adapted from a comparative study, details the steps for automated analysis using systems like the ScanScope XT and ACIS III, contrasting them with manual scoring [9].

- Sample Preparation: Tissue Microarrays (TMAs) are constructed using a 1-mm punch from representative areas of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks. Sections are deparaffinized by incubation at 60°C for 24 hours, followed by immersion in xylene and hydration in a graded ethanol series [9].

- Immunohistochemistry Staining:

- Antigen Retrieval: Slides are incubated in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker for 30 minutes.

- Blocking: Endogenous peroxidase is blocked with 10% H₂O₂.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Sections are incubated with primary antibodies (e.g., pAKT, pmTOR at 20 µg/ml) diluted in 1% BSA/PBS for 18 hours at 4°C.

- Secondary Detection: Staining is performed using a two-step procedure (e.g., Advance HRP, Dako) with incubations at 37°C.

- Color Development: Slides are incubated with a DAB substrate solution, followed by counterstaining with Harris hematoxylin and mounting [9].

- Manual Analysis (Control Method): Two qualified observers independently score TMA spots. The percentage of positively stained cells is categorized (0-4), and staining intensity is graded (0-3). A Quickscore (0-7) is generated by summing the two scores, introducing subjectivity [9].

- Automated Analysis:

- ScanScope XT: The internal algorithm classifies each pixel by intensity (0-3) and calculates the percentage of positive pixels. An HSCORE is computed using the formula: HSCORE = Σ(i × Pi), where Pi is the percentage of positive pixels and i is the pixel staining intensity [9].

- ACIS III: The system performs analysis based on automatically chosen "hotspots," calculating a score from the percentage of immunopositive cells and staining intensity [9].

- Statistical Analysis: Agreement between manual observers and automated systems is evaluated using weighted κ statistics [9].

Protocol: Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) and Data Fitting

This protocol outlines the process for generating and analyzing concentration-response data, a cornerstone of HTE in drug discovery.

- Assay Miniaturization and Setup: Experiments are conducted in low-volume microtiter plates (e.g., 1536-well format with <10 µl per well). Automated liquid handlers (e.g., I.DOT Liquid Handler) dispense compounds, cells, and reagents at nanoliter scales to create concentration series across the plate [25] [24].

- Data Acquisition: High-sensitivity detectors measure the biological response (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) for each well across the titration series [25].

- Concentration-Response Curve (CRC) Fitting: The resulting data for each compound is fit to a nonlinear model, most commonly the Hill equation (HEQN) (Logistic form): ( Ri = E0 + \frac{(E{\infty} - E0)}{1 + \exp{-h[\log Ci - \log AC{50}]}} ) where ( Ri ) is the measured response at concentration ( Ci ), ( E0 ) is the baseline response, ( E{\infty} ) is the maximal response, ( AC_{50} ) is the half-maximal effective concentration, and ( h ) is the Hill slope [25].

- Data Visualization and Analysis: Specialized software, such as the

qHTSWaterfallR package, is used to create 3-dimensional visualizations of the entire dataset (e.g., potency vs. efficacy vs. compound ID) to identify patterns and active compounds [26]. Parameter estimates (( AC{50} ), ( E{max} )) are used to rank and prioritize compounds for further investigation [25].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow and key differences between manual and automated HTE methodologies.

Diagram 1: Manual vs. Automated HTE Workflow Comparison

Diagram 2: ML and HTE Synergy Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful HTE relies on a suite of specialized tools and reagents that enable miniaturization, automation, and data analysis.

Table 4: Key Reagents, Equipment, and Software for HTE

| Category | Item | Function in HTE |

|---|---|---|

| Lab Automation | Liquid Handling Robots (e.g., I.DOT, Hamilton, Tecan) | Precisely dispenses nanoliter-to-microliter volumes of compounds, cells, and reagents into high-density microtiter plates, enabling parallelization [24]. |

| Lab Automation | Microtiter Plates (96-, 384-, 1536-well) | The physical platform for miniaturized assays, allowing thousands of reactions to be performed in parallel [25] [24]. |

| Assay Reagents | Cell-Based Assay Reagents (e.g., luciferase substrates, viability dyes) | Report on biological activity in cellular assays. Miniaturization conserves these often costly reagents [24]. |

| Assay Reagents | purified enzymes & substrates | Essential for biochemical high-throughput screens to identify modulators of enzyme activity. |

| Chromatography | Miniaturized Chromatographic Columns | Used in high-throughput downstream process development for biomolecules, allowing parallel purification screening on liquid handling stations [27]. |

| Informatics & Analysis | Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) & LIMS | Captures experimental data and metadata in a FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) compliant manner, which is crucial for managing HTE data [23]. |

| Informatics & Analysis | Data Analysis Software (e.g., qHTSWaterfall R package) |

Visualizes and analyzes complex multi-parameter qHTS data, facilitating interpretation and hit identification [26]. |

| Informatics & Analysis | Hill Equation Modeling | The standard nonlinear model used to fit concentration-response data and derive key parameters (AC50, Emax, Hill slope) for compound ranking and characterization [25]. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) with HTE is poised to further revolutionize research practices. The synergy between ML and HTE creates a virtuous cycle: HTE generates the large, high-quality datasets required to train robust ML models, which in turn predict promising experimental areas, leading to more efficient and informative HTE campaigns [23] [28]. This feedback loop, illustrated in Diagram 2, is paving the way for autonomous, self-optimizing laboratories [28].

Despite its advantages, HTE presents significant data analysis challenges. The parameter estimates from nonlinear models like the Hill equation can be highly variable if the experimental design is suboptimal, for example, if the concentration range fails to define the upper or lower asymptote of the response curve [25]. This underscores the need for careful experimental design and robust data analysis pipelines. Furthermore, managing the immense volume of data generated requires a FAIR-compliant informatics infrastructure to fully capture and leverage the value of HTE data [23].

In conclusion, the objective comparison of performance data clearly demonstrates that automated HTE methods, built on the pillars of miniaturization and parallelization, provide substantial advantages over manual techniques in terms of speed, data quality, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness. As these technologies continue to converge with advanced computational methods, their role in accelerating discovery across the life and material sciences will only become more pronounced.

AI-Powered Synthesis Planning and Substrate Prediction Tools

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into chemical synthesis planning and substrate prediction represents a paradigm shift in how researchers design molecules, plan synthetic routes, and discover enzyme substrates. AI-powered Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools leverage machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms to analyze vast chemical reaction databases, predict synthetic pathways, and optimize reaction conditions with unprecedented speed and accuracy [29]. This technological transformation is particularly vital in pharmaceuticals, where AI-CASP tools are reducing drug discovery timelines by 30-50% in preclinical phases and significantly lowering development costs [30].

Parallel to synthesis planning, AI-driven substrate prediction has emerged as a powerful approach for mapping enzyme-substrate relationships, a task traditionally hampered by expensive and time-consuming experimental characterizations [5]. Machine learning models now enable researchers to efficiently predict which small molecules specific enzymes act upon, supporting critical applications in drug discovery, bio-engineering, and metabolic pathway analysis [5] [31]. The convergence of these technologies—AI-powered synthesis planning and substrate prediction—is creating unprecedented opportunities for accelerating research and development across chemical and pharmaceutical domains.

Comparative Analysis of AI Synthesis Planning Tools

Market Landscape and Adoption Trends

The AI in CASP market has demonstrated explosive growth, reflecting its increasing importance in research and development. According to recent market analyses, the global AI in CASP market was valued between $2.13 billion (2024) and $3.1 billion (2025), with projections reaching $68-82 billion by 2034-2035, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 38-41% [30] [29]. This remarkable growth trajectory underscores the rapid integration of AI technologies into chemical synthesis workflows across multiple industries.

North America currently dominates the market, accounting for 38.7-42.6% of the global share, driven by substantial investments in advanced chemical synthesis technologies and robust federal funding for AI-based biomedical research [30] [29]. The United States alone accounted for $0.83 billion in 2024, expected to grow to $23.67 billion by 2034 [29]. Meanwhile, the Asia-Pacific region is emerging as the fastest-growing market, stimulated by increasing adoption of AI-driven drug discovery and innovations in combinatorial chemistry and neural network-based reaction prediction [30].

Table 1: Global AI in Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning Market Overview

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2034/2035 Projection | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | $2.13-3.1 billion | $68.06-82.2 billion | 38.8-41.4% | Rising R&D costs, need for faster discovery cycles |

| Software Segment Share | 65.5-65.8% by 2035 | Proprietary AI platforms and algorithms [30] [29] | ||

| North America Share | 38.7-42.6% | Advanced R&D infrastructure, pharmaceutical investment [30] [29] | ||

| Drug Discovery Application | 75.2% market share | Therapeutic development acceleration [29] |

Key Tool Capabilities and Performance Metrics

AI-powered synthesis planning tools employ diverse technological approaches, from template-based models to transformer-based architectures, each with distinct capabilities and performance characteristics. Tools like AiZynthFinder utilize Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithms with template-based models to generate multistep retrosynthesis predictions [32]. Recent advancements have introduced human-guided synthesis planning via prompting, allowing chemists to specify bonds to break or freeze during retrosynthesis, thereby incorporating valuable prior knowledge into the AI-driven process [32].

The performance of these tools is increasingly validated through both computational benchmarks and real-world applications. For instance, a novel strategy combining a disconnection-aware transformer with multi-objective search in AiZynthFinder demonstrated a significant improvement in satisfying bond constraints for targets in the PaRoutes dataset (75.57% vs. 54.80% for standard search) [32]. This capability is particularly valuable when planning joint synthesis routes for similar compounds where common disconnection sites can be identified across molecules.

Table 2: Leading AI-Powered Synthesis Planning Tools and Capabilities

| Tool/Platform | Key Technology | Unique Capabilities | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| AiZynthFinder | Template-based models, MCTS | Human-guided retrosynthesis via prompting, frozen bonds filter [32] | Multistep retrosynthesis for pharmaceutical compounds |

| Disconnection-Aware Transformer | Transformer architecture | Bond tagging for specified disconnections, SMILES string processing [32] | Targeted disconnection of specific molecular bonds |

| Chemistry42 | Generative AI models | Novel chemical structure design, antibiotic candidate identification [30] | de novo molecule design, drug discovery |

| ESP (Enzyme Substrate Prediction) | Gradient-boosted decision trees, protein embeddings | Cross-enzyme family substrate prediction, negative data augmentation [5] | Enzyme-substrate relationship mapping |

Comparative Analysis of Substrate Prediction Methods

Machine Learning Approaches for Substrate Identification

Substrate prediction has evolved from enzyme family-specific models to general frameworks capable of predicting enzyme-substrate pairs across diverse protein families. The ESP (Enzyme Substrate Prediction) model represents a significant advancement in this domain, achieving over 91% accuracy on independent and diverse test data [5]. This model employs a customized, task-specific version of the ESM-1b transformer model to create informative protein representations, combined with graph neural networks (GNNs) to generate molecular fingerprints of small molecules [5]. A gradient-boosted decision tree model is then trained on the combined representations, enabling high-accuracy predictions across widely different enzyme families.

Alternative approaches include the K-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm combined with mRMR-IFS feature selection method, which has demonstrated 89.1% prediction accuracy for substrate-enzyme-product interactions in metabolic pathways [31]. This method utilizes 160 carefully selected features spanning ten categories, including elemental analysis, geometry, chemistry, amino acid composition, and various physicochemical properties to represent the main factors governing substrate-enzyme-product interactions [31].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Substrate Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESP Model [5] | 91% | Transformer-based protein representations, GNN molecular fingerprints | General applicability across enzyme families, minimal false negatives | Limited to ~1400 metabolites in training set |

| KNN with mRMR-IFS [31] | 89.1% | 160 features from 10 categories (elemental, geometric, physicochemical) | Effective for metabolic pathway predictions | Older method, potentially less accurate than newer approaches |

| ML-Hybrid for PTMs [33] | 37-43% validation rate | Peptide array data, ensemble models | Successful for post-translational modification prediction | Lower validation rate compared to small molecule methods |

| Conventional In Vitro [33] | 7.5% precision (SET8) | Peptide permutation arrays, motif generation | Direct experimental evidence | Low throughput, high cost, time-consuming |

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Rigorous experimental validation is crucial for assessing the real-world performance of substrate prediction tools. In the development of the ESP model, researchers created a high-quality dataset with approximately 18,000 experimentally confirmed positive enzyme-substrate pairs, comprising 12,156 unique enzymes and 1,379 unique metabolites [5]. To address the lack of negative examples in public databases, the team implemented a data augmentation strategy, sampling negative training data only from enzyme-small molecule pairs where the small molecule is structurally similar to a known true substrate (similarity scores between 0.75 and 0.95) [5].

For post-translational modification (PTM) prediction, a ML-hybrid approach combining machine learning with enzyme-mediated modification of complex peptide arrays demonstrated a significant performance increase over conventional in vitro methods [33]. This method correctly predicted 37-43% of proposed PTM sites for the methyltransferase SET8 and sirtuin deacetylases SIRT1-7, compared to much lower precision rates for conventional permutation array-based prediction [33]. The integration of high-throughput experiments to generate data for unique ML models specific to each PTM-inducing enzyme enhanced the capacity to predict substrates, streamlining the discovery of enzyme activity.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for AI-Guided Synthesis Planning

The experimental workflow for AI-guided synthesis planning typically begins with target molecule specification, followed by the application of retrosynthesis algorithms to generate potential synthetic routes. In human-guided approaches, chemists can provide input on specific bonds to break or freeze as prompts to the tool [32]. The frozen bonds filter then excludes any single-step predictions that violate these constraints, while the broken bonds score favors routes satisfying the bonds to break constraints early in the search tree [32].

A key advancement in this domain is the integration of disconnection-aware transformers with template-based models in a multistep retrosynthesis framework. This approach allows for reliable propagation of disconnection site tagging to subsequent steps in the synthesis route, enabling the system to handle cases where several steps may be required to break the specified bonds [32]. The multi-objective Monte Carlo Tree Search (MO-MCTS) algorithm then balances multiple objectives, including standard expansion scores and the novel broken bonds score, to generate synthetic routes that satisfy user constraints while maintaining synthetic feasibility.

AI Synthesis Planning Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow combining human prompting with multi-objective search algorithms and multiple prediction models for constrained synthesis planning.

Protocol for Substrate Prediction Validation

The experimental validation of substrate predictions typically follows a rigorous workflow combining computational prediction with experimental verification. For enzyme-substrate prediction, the process begins with constructing a comprehensive dataset of known enzyme-substrate pairs from databases like UniProt and KEGG [5] [31]. The ESP model, for instance, was trained on 18,351 enzyme-substrate pairs with experimental evidence for binding, complemented by 274,030 enzyme-substrate pairs with phylogenetically inferred evidence [5].

Negative examples are generated through data augmentation by randomly sampling small molecules similar to known substrates (similarity scores 0.75-0.95) but assigned as non-substrates [5]. This approach challenges the model to distinguish between similar binding and non-binding reactants while minimizing false negatives by sampling only from metabolites likely to occur in biological systems.

For PTM substrate prediction, the ML-hybrid approach begins with synthesizing a representative PTM proteome using peptide arrays, which are then subjected to in vitro enzymatic activity assays [33]. The resulting data trains machine learning models augmented by generalized PTM-specific predictors, creating ensemble models unique to each enzyme that demonstrate enhanced predictive accuracy in cell models.

Substrate Prediction & Validation Workflow: This diagram outlines the comprehensive process from data collection and augmentation through model training to experimental validation of substrate predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of AI-powered synthesis planning and substrate prediction requires specific research reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit for scientists working in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Powered Synthesis and Substrate Prediction

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays | High-throughput representation of protein segments for PTM analysis [33] | Identification of SET8 methylation sites, SIRT deacetylation sites [33] | Customizable sequences, compatible with various modification assays |

| Molecular Descriptors (ChemAxon) | Numerical representation of compound structures [31] | Prediction of substrate-enzyme-product interactions in metabolic pathways [31] | 79+ molecular descriptors reflecting physicochemical/geometric properties |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Generation of task-specific molecular fingerprints [5] | Creating small molecule representations for ESP model [5] | Captures molecular structure and properties in machine-readable format |

| Transformer Models (ESM-1b) | Protein sequence representation learning [5] | Enzyme feature extraction for substrate prediction [5] | Creates maximally informative protein representations from primary sequence |

| Retrosynthesis Transformers | Single-step retrosynthesis prediction [32] | Disconnection-aware molecular fragmentation [32] | SMILES-based processing enabling bond tagging and constrained synthesis |

| Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) | Exploration of synthetic route space [32] | Multi-step retrosynthesis in AiZynthFinder [32] | Balances exploration and exploitation in synthetic pathway generation |

The comprehensive analysis of AI-powered synthesis planning and substrate prediction tools reveals a consistent pattern of advantages for automated approaches over traditional manual methods across multiple performance metrics. Automated synthesis methods demonstrate superior robustness and repeatability compared to manual techniques, while significantly reducing operator radiation exposure in radiopharmaceutical applications [34]. Furthermore, standardized automation enhances compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines, facilitating the translation of research discoveries into clinically applicable products [34].

In substrate prediction, machine learning models like ESP achieve prediction accuracies exceeding 91%, dramatically reducing the experimental characterization burden required to map enzyme-substrate relationships [5]. The ML-hybrid approach for PTM substrate identification correctly predicts 37-43% of proposed modification sites, representing a 5-6 fold improvement in precision compared to conventional in vitro methods [33]. These performance advantages translate into significant time and cost savings, with AI-driven approaches reducing drug discovery timelines by 30-50% in preclinical phases [30].

However, challenges remain in balancing scalability with security in AI-driven synthesis platforms and addressing the high development costs of durable AI systems with uncertain reimbursement pathways [30]. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing the explainability of AI recommendations, improving integration with laboratory automation systems, and expanding the scope of predictable reactions and substrates. As these technologies mature, they are poised to become indispensable components of the research toolkit, fundamentally transforming how scientists approach molecular design and synthesis in both academic and industrial settings.

Substrate-Multiplexed Screening with Automated Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The comprehensive evaluation of enzyme substrate scope is a fundamental challenge in biochemistry, drug development, and biocatalysis. Traditional one-substrate-at-a-time approaches create significant bottlenecks in characterizing enzyme function, engineering promiscuous catalysts, and identifying selective inhibitors. Substrate-multiplexed screening (SUMS) coupled with automated mass spectrometry analysis represents a paradigm shift in enzymatic assay methodology. This approach allows researchers to simultaneously probe enzyme activity against dozens or even hundreds of substrates in a single reaction vessel, dramatically accelerating the functional characterization of enzymes. The automated mass spectrometry workflow enables rapid, label-free detection of multiple reaction products without the need for chromogenic or fluorescent reporters. This guide provides an objective comparison between substrate-multiplexed screening and traditional manual methods, supported by experimental data from recent studies, to inform researchers about the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of these competing approaches in modern enzyme research.

Technology Comparison: Multiplexed vs. Traditional Methods

Key Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of substrate screening methodologies

| Methodology | Throughput (Reactions) | Substrates per Reaction | Time per Sample | Quantitation Capability | Label-Free | Information Richness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate-Multiplexed MS | 38,505 reactions in single study [35] | 40-453 substrates [35] [36] | 10-20 seconds (direct infusion) [37] | Product ratios reflect catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) [38] | Yes [37] | High (multiple simultaneous readouts) [38] |

| Traditional Single-Substrate | Limited by individual assays | 1 | 600-1200 seconds (LC-MS) [37] | Direct absolute quantitation possible | Possible, but often uses labels | Low (single readout) |

| Fluorescence-Based HTS | ~30000 droplets/second (FADS) [37] | 1 (typically) | ~3.6×10⁻⁴ seconds [37] | Limited to fluorescent products | No | Low to moderate |

| Colorimetric Microplates | Moderate (plate-based) | 1 | ~8 seconds [37] | Limited to chromogenic products | No | Low |

Experimental Workflows

Table 2: Comparison of experimental protocols and requirements

| Aspect | Substrate-Multiplexed MS | Traditional Manual Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Pooled substrates (40 compounds/reaction) [35] | Individual substrate reactions |

| Enzyme Source | Clarified E. coli lysate [35] | Purified enzymes or lysates |

| Reaction Scale | 10 μM substrates, 83 μM UDP-glucose [35] | Variable, often higher concentrations |

| Detection Method | LC-MS/MS with data-dependent acquisition [35] | Various (MS, fluorescence, absorbance) |

| Data Analysis | Automated computational pipeline with cosine scoring [35] | Manual or semi-automated analysis |

| Validation | Purified enzyme assays on selected hits [35] | Built-in to primary screen |

Experimental Protocols for Substrate-Multiplexed Screening

Core Methodological Framework

The following protocols are compiled from recent implementations of substrate-multiplexed screening with automated MS analysis across different enzyme classes:

Glycosyltransferase Profiling Protocol [35]:

- Enzyme Preparation: Clone 85 Arabidopsis family 1 glycosyltransferases into E. coli expression vector pET28a. Express enzymes in E. coli and use clarified lysate as enzyme source without purification.

- Substrate Library Design: Select 453 natural products based on presence of nucleophilic functional groups (hydroxyl, amine, thiol, aromatic ring). Divide into pools of 40 compounds with unique molecular weights.

- Multiplexed Reactions: Incubate individual GT lysates with UDP-glucose donor and 40 substrate candidates overnight. Use GFP-expressing lysate as negative control.

- MS Analysis: Analyze crude reaction mixtures via LC-MS/MS with data-dependent acquisition using inclusion lists containing all possible single- and double-glycosylation products.

- Automated Data Processing: Extract mass features and compare to reference spectra using computational pipeline. Apply cosine score threshold of 0.85 for positive identification.

Prenyltransferase Screening Protocol [36]:

- Homolog Library: Construct sequence similarity network of 5,000 PT-homologous sequences and select 46 representatives covering phylogenetic diversity.

- Whole-Cell Screening: Express PT homologs in E. coli in 96-well plate format. Use as whole-cell catalysts without purification.

- Substrate Competition: Incubate with mixture of most common native substrates (DMAPP/GPP as donors, Trp/Tyr as aromatic acceptors).

- Isomer Discrimination: Develop LC-MS assay to distinguish between prenylated Trp and Tyr isomers based on retention time and mass.

- Activity Assignment: Identify novel activities based on product masses and chromatographic behavior compared to standards.

SUMS for Protein Engineering Protocol [38]:

- Library Design: Create site-saturation mutagenesis and random mutagenesis libraries targeting active site residues.

- Substrate Cocktail Design: Combine multiple substrates at concentrations reflecting engineering goals (equimolar for broad scope, biased for specific activity).

- Screening Conditions: Run reactions beyond initial velocity regime to capture heuristic reactivity readouts relevant to synthesis applications.

- Product Ratio Analysis: Monitor changes in product profiles to identify mutations that alter substrate specificity or promiscuity.

- Validation: Correlate multiplexed results with traditional Michaelis-Menten parameters for selected variants.

Automation and Data Processing

A critical advantage of substrate-multiplexed screening is the automated analysis of complex product mixtures:

Figure 1: Automated MS Data Analysis Workflow. The computational pipeline processes raw mass spectrometry data through feature extraction, spectral matching, and similarity scoring to automatically identify enzymatic products [35].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for substrate-multiplexed screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Library | Diverse substrate collection | MEGx library (453 compounds) [35] |

| Enzyme Expression System | Heterologous enzyme production | E. coli expression vectors (pET28a) [35] |

| Nucleotide Sugar Donors | Glycosyltransferase co-substrate | UDP-glucose (83 μM in reactions) [35] |

| Prenyl Donors | Prenyltransferase co-substrates | DMAPP, GPP [36] |

| LC-MS Solvents | Chromatography separation | HPLC-grade methanol, water, acetonitrile |

| Reference Spectral Library | Product identification | MassBank of North America (MoNA) [35] |

| Automated Liquid Handling | High-throughput screening | Robotic systems for 384-well plates [39] |

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Quantitative Assessment of Method Efficacy

Throughput and Efficiency Metrics:

- The glycosyltransferase study screened 85 enzymes against 453 substrates in multiplexed batches of 40, totaling 38,505 reactions [35]. This represents a >40x reduction in experimental time compared to individual reactions.

- Direct infusion ESI-MS methods achieve analysis speeds of 10-20 seconds per sample, compared to 600-1200 seconds for standard LC-MS [37].

- Multiplexed serology via mass cytometry enabled 36,960 tests in 400 nL of sample volume [40], demonstrating exceptional miniaturization potential.

Data Quality and Validation:

- Comparison with previous single-substrate studies showed ~70% agreement in reaction outcomes despite different experimental conditions [35].

- Automated pipeline identified 4,230 putative reaction products (3,669 single glycosides, 561 double glycosides) using stringent cosine score threshold of 0.85 [35].

- Validation with purified enzymes confirmed lysate-based screening results, demonstrating method reliability [35].

Specificity Profiling Capabilities:

- SUMS revealed widespread promiscuity and strong preference for planar, hydroxylated aromatic substrates among family 1 glycosyltransferases [35].

- Prenyltransferase screening identified PriB as exceptionally promiscuous and discovered first bacterial Tyr O-prenyltransferase [36].

- Engineering campaigns using SUMS identified mutations that simultaneously improved activity on multiple substrates [38].

Substrate-multiplexed screening with automated mass spectrometry analysis represents a transformative methodology for enzyme characterization, profiling, and engineering. The quantitative data presented in this comparison guide demonstrates clear advantages in throughput, efficiency, and information content compared to traditional manual methods. While the approach requires specialized instrumentation and computational infrastructure, the dramatic acceleration in substrate scope assessment makes it particularly valuable for enzyme engineering, metabolic pathway discovery, and drug metabolism studies. As mass spectrometry technology continues to advance and become more accessible, substrate-multiplexed approaches are poised to become standard practice for comprehensive enzymatic analysis in academic and industrial research settings.

This case study examines a high-throughput, automated platform for functionally characterizing plant Family 1 glycosyltransferases (GTs), profiling 85 enzymes against a diverse library of 453 natural product substrates [41]. The study serves as a pivotal reference point within the broader thesis of evaluating substrate scope determination, contrasting scalable, multiplexed automated methods with traditional, low-throughput manual approaches. The following guide objectively compares the performance of this automated platform against conventional methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Experimental Protocol: The Automated, Multiplexed Screening Platform

The core methodology represents a paradigm shift from one-enzyme, one-substrate manual assays to a massively parallel, automated workflow [41].

- Enzyme Library Preparation: 85 Family 1 GTs from Arabidopsis thaliana were subcloned from a synthetic library into a pET28a vector for expression in Escherichia coli [41].

- Expression and Lysate Preparation: Enzymes were expressed in E. coli, and clarified bacterial lysates served as the enzyme source, bypassing time-consuming protein purification steps. Pilot studies confirmed lysate activity was comparable to purified enzyme [41].

- Substrate Library Design: A library of 453 potential acceptor substrates was curated from a commercial natural product collection (MEGx library). Selection was based on the presence of nucleophilic functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, amine) required for glycosylation [41].

- Substrate Multiplexing: To maximize throughput, substrates were pooled into sets of 40 compounds each, with unique molecular weights to enable distinct detection by mass spectrometry (MS). Each GT lysate was reacted with one pool of 40 substrates and the sugar donor UDP-glucose [41].

- High-Throughput Reaction and Analysis: Reactions were performed combinatorially, resulting in 38,505 individual reaction screenings. Post-incubation, crude mixtures were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using data-dependent acquisition targeted with inclusion lists for all potential glycosylation products [41].

- Automated Data Processing: A dedicated computational pipeline was developed to identify glycosides from complex MS data. It extracted mass features and compared experimental MS/MS spectra to a reference library using a cosine similarity score. A stringent threshold (cosine score ≥0.85) was applied to minimize false positives, leading to the identification of 4,230 putative reaction products [41].

The automated screen generated a dataset of unprecedented scale, revealing fundamental insights into GT function.

Table 1: Summary of High-Throughput Screening Output

| Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Total Possible Reactions Screened | 38,505 | Demonstrates the massive scale enabled by multiplexing. |

| Putative Glycosylation Products Identified | 4,230 (3,669 single, 561 double) | Reveals widespread enzymatic activity and promiscuity. |

| Key Substrate Preference Identified | Planar, hydroxylated aromatic compounds | Provides a functional rule predictive for uncharacterized GTs. |

| Validation Agreement with Prior Study [41] | ~70% (582 overlapping reactions) | Confirms reliability despite different experimental conditions. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Automated Multiplexed vs. Traditional Manual Methods

| Aspect | Automated, Multiplexed Platform (This Study) | Traditional Manual Characterization |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Extremely High: 85 enzymes x 453 substrates screened combinatorially. | Very Low: Typically one enzyme, one substrate, one reaction at a time. |

| Data Generation Speed | Rapid: Near 40,000 reactions assessed in a single screening campaign. | Slow: Pace limited by purification, individual assay setup, and analysis. |

| Substrate Scope Discovery | Systematic & Broad: Unbiased detection of activity across a vast chemical space, identifying promiscuity. | Targeted & Narrow: Often hypothesis-driven, may miss unexpected activities. |

| Resource Intensity | High initial setup (library cloning, method development); low marginal cost per additional data point. | Consistently high per data point (purification, reagents, labor). |

| Primary Output | Large-scale functional dataset; patterns and preferences (e.g., for planar phenolics) emerge from data. | Detailed kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for specific enzyme-substrate pairs. |

| Best Suited For | Gene discovery, functional landscape mapping, initial activity screening, identifying broad specificity. | Mechanistic studies, detailed enzymology, validating specific interactions. |

Discussion: Validating the Automated Approach within the Methodological Thesis

This case study provides compelling evidence for the advantages of automation in substrate scope profiling, while also highlighting contexts where manual methods remain essential.

- Scale and Discovery Power: The platform's ability to query nearly 40,000 reactions is inconceivable with manual methods [41]. This scale directly led to the discovery of a strong overall substrate preference for planar, hydroxylated aromatics among Family 1 GTs—a pattern difficult to discern from piecemeal manual studies [41].