Batch vs Flow Automated Synthesis: A Strategic Comparison for Modern Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of batch and flow automated synthesis platforms for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Batch vs Flow Automated Synthesis: A Strategic Comparison for Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of batch and flow automated synthesis platforms for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, key application methodologies across photochemistry, hydrogenation, and handling of hazardous reagents, along with practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The content also addresses the critical framework for validation and offers a direct comparative analysis to guide platform selection, highlighting how these technologies accelerate early-phase discovery and enable more efficient, safer scale-up.

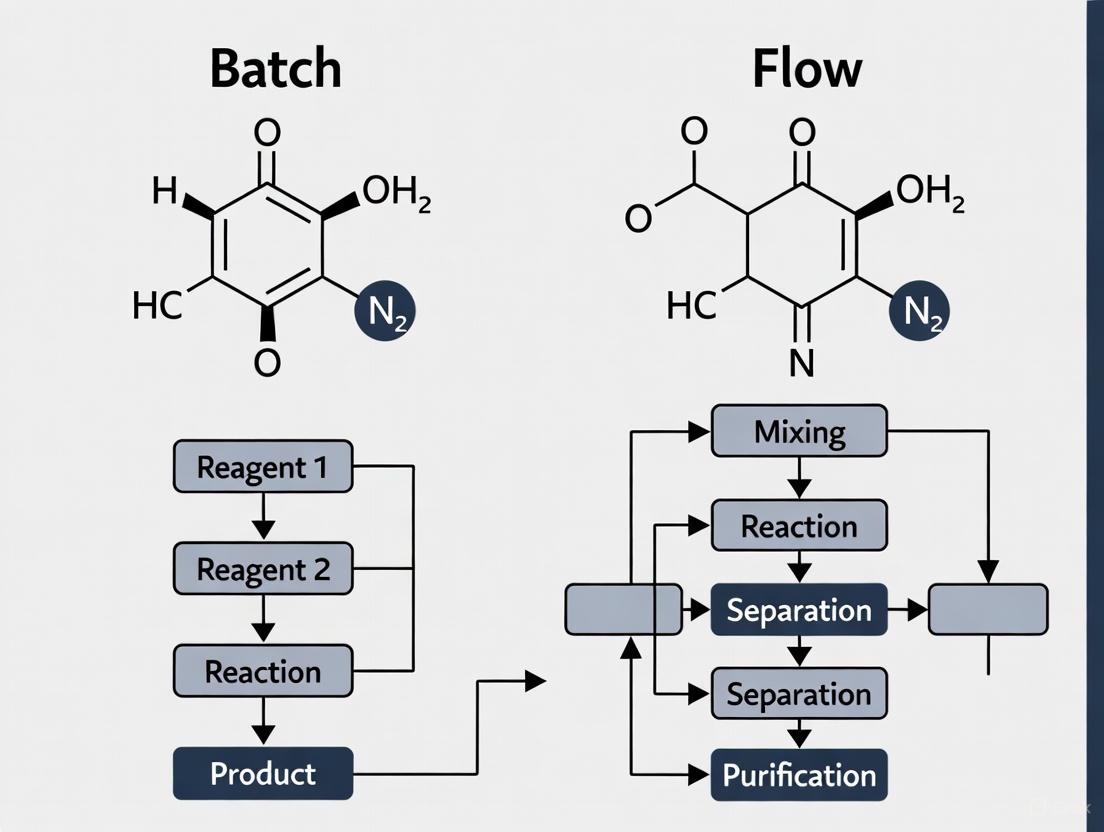

Batch and Flow Chemistry Explained: Core Principles and System Setup

The evolution of chemical synthesis, particularly in the demanding field of drug discovery, is increasingly defined by a paradigm shift from traditional discrete batch processes towards integrated continuous flow systems. Within the context of automated synthesis platforms, this comparison is not merely about reactor choice but about fundamentally different philosophies for conducting and scaling chemical research and development. This guide objectively compares these two platforms, underpinned by experimental data and protocols from current research.

Core Definitions and Philosophical Framework

Batch Processing is defined as a discrete manufacturing method where a specific quantity of materials is processed as a single group through each step of a synthetic sequence. The process has a defined start and endpoint; subsequent batches must wait until the current one is completed [1] [2] [3]. In a laboratory or pilot-scale context, this translates to reactions conducted in flasks or jacketed reactors, where the entire reaction volume exists as a discrete entity for a defined period [4].

Flow Chemistry (Continuous Processing), in contrast, involves the continuous movement of reagents through a network of tubes, mixers, and reactors. The product is formed in an ongoing stream without discrete start/stop points for the reaction itself [4] [2]. The output volume is limited only by operational time, not vessel size [4]. This continuous system is inherently more compatible with automation, offering excellent homogeneity and control over reaction parameters at any given moment [5] [4].

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics

The following table synthesizes quantitative and qualitative data comparing batch and flow platforms within automated synthesis contexts.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Batch vs. Flow Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Metric | Batch Process (Discrete) | Flow Chemistry (Continuous) | Key Supporting Evidence / Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production Rate & Volume | Suitable for small to medium volumes. Slower due to stop/start cycling and limited vessel capacity [2] [3]. | Designed for high-throughput and large-scale output. Enables uninterrupted production, leading to higher throughput and shorter processing times [2] [3]. | Flow systems can achieve kilogram-scale production per day (e.g., 6.56 kg/day for a photoredox reaction) [5]. |

| Flexibility & Customization | High flexibility. Equipment can be reconfigured between batches for different products, ideal for niche markets and variable demand [2] [3]. | Lower inherent flexibility. Systems are often optimized for a specific type of chemistry or product; changes require significant reconfiguration [2] [3]. | Batch HTE excels in parallel substrate scoping (e.g., 110 compounds synthesized in microtiter plates) [5]. |

| Quality Control (QC) | QC is typically performed at the end of a batch. Adjustments are made between batches based on inspection results [2] [3]. | QC is integrated via real-time Process Analytical Technology (PAT). Automated systems allow for immediate correction during production [5] [2]. | Inline/real-time PAT in flow enables more efficient HTE workflows with less material and intervention [5]. |

| Equipment & Maintenance | Generally simpler, smaller equipment. Easier to maintain but may experience more wear from frequent start/stop cycles [2] [3]. | More sophisticated, complex equipment designed for prolonged operation. Requires robust, proactive maintenance to avoid costly downtime [2] [3]. | Commercial automated flow platforms (e.g., Vapourtec) and bespoke systems are widely reported [5]. |

| Cost Structure | Lower initial setup cost but higher unit cost due to lower production rates, frequent cleaning, and setup [1] [2] [3]. | Higher initial investment but lower unit cost at scale due to higher efficiency, reduced downtime, and lower cleaning costs [1] [2] [3]. | Economic viability is scale-dependent; batch is favored for high-value, low-volume specialty chemicals [2]. |

| Safety Profile | Larger volumes of reactive material present at one time, posing greater risks with exothermic or hazardous chemistry [5]. | Superior safety. The "miniaturization" effect means only a small volume is reactive at any moment, enabling safe use of hazardous reagents [5] [4]. | Flow allows safe handling of alkyl lithium, azides, and diazo compounds [5]. |

| Scalability & Translation | Scale-up is non-linear ("scale-out"). Optimized conditions in small batches often require extensive re-optimization for larger vessels due to changes in heat/mass transfer [5]. | Linear scale-up ("scale-out" or "numbering up"). Conditions are preserved by increasing runtime or parallelizing reactors, minimizing re-optimization [5] [4]. | A photoredox fluorodecarboxylation was optimized in microliter plates, then directly scaled to 100g and 1.23kg in flow with minimal re-optimization [5]. |

| Synthetic Scope & Process Windows | Limited by solvent boiling points and challenges with efficient mixing/heat transfer for very fast or highly exothermic reactions. | Enables access to extreme process windows (high T/P). Improved mass/heat transfer allows exploration of challenging chemistry [5]. | Pressurized flow systems enable the use of solvents at temperatures far above their atmospheric boiling points [5]. |

| Integration with AI & Automation | Well-suited for parallel, discrete "Make" steps in AI-driven Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycles, especially for library synthesis [6] [7]. | Ideal for closed-loop, autonomous optimization and end-to-end multistep synthesis. Digitally controlled platforms can execute AI-proposed conditions directly [8] [9]. | LLM-based agents can control end-to-end flow synthesis development, from literature search to scale-up [8]. Automated platforms link generative AI with robotics for synthesis [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening (HTE) for Photoredox Fluorodecarboxylation (Batch-to-Flow Translation)

This protocol exemplifies the complementary use of batch HTE for discovery and flow for translation and scale-up [5].

- Objective: Discover and optimize conditions for a flavin-catalyzed photoredox fluorodecarboxylation.

- Batch HTE Screening:

- Setup: A 96-well plate photoreactor.

- Variables Screened: 24 photocatalysts, 13 bases, 4 fluorinating agents.

- Method: Reactions are conducted in parallel in ~300 µL wells with consistent light wavelength and solvent.

- Analysis: Reactions are quenched and analyzed by LC-MS or NMR to identify "hits."

- Batch Validation & Optimization: Hits are validated in a larger batch reactor. A Design of Experiments (DoE) approach is used to optimize concentrations, stoichiometry, and time.

- Flow Translation & Scale-Up:

- Small-Scale Flow: Optimal conditions are transferred to a commercial photochemical flow reactor (e.g., Vapourtec UV150) on a 2g scale to confirm feasibility.

- Scale-Up: A custom two-feed flow setup is used. Key flow parameters (residence time, light intensity, temperature) are optimized.

- Production: The process is run continuously, scaling linearly with time to produce 1.23 kg at 92% yield.

Protocol 2: End-to-End Autonomous Reaction Development using LLM-Agents and Automated Flow

This protocol demonstrates a fully integrated, continuous-system approach to synthesis development [8].

- Objective: Autonomously develop a synthetic procedure for copper/TEMPO-catalyzed aerobic alcohol oxidation.

- Agents & Platform: An LLM-based Reaction Development Framework (LLM-RDF) with six specialized agents (Literature Scouter, Experiment Designer, Hardware Executor, etc.) controls an automated high-throughput screening (HTS) flow/ batch platform and analytics.

- Workflow:

- Literature Search: The "Literature Scouter" agent queries databases (e.g., Semantic Scholar) to identify and summarize relevant methodologies.

- Experiment Design: The "Experiment Designer" agent, given the target transformation and constraints, designs a substrate scope and condition screening campaign.

- Automated Execution: The "Hardware Executor" agent translates the design into instrument commands, executing the HTS on the automated platform (e.g., running reactions in open-cap vials for aerobic oxidation).

- Analysis & Interpretation: The "Spectrum Analyzer" and "Result Interpreter" agents process GC/MS data, calculate yields, and identify trends.

- Optimization & Scale-Up: Based on results, the system can iteratively design new experiments for kinetic studies or optimization, finally executing a scale-up run in flow.

Visualization of Workflows and Logical Relationships

Diagram 1: Synthesis Development Pathways in Modern Research

Diagram 2: End-to-End Automated Synthesis Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Tools for Modern Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Relevance to Batch/Flow Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Plates (96/384-well) | Enables parallel reaction screening of catalysts, reagents, and substrates in discrete, nanomole to micromole volumes [5]. | Batch HTE cornerstone. Used for initial "brute force" exploration of chemical space. |

| Modular Photochemical Flow Reactor (e.g., with LED arrays) | Provides efficient, uniform irradiation for photoredox chemistry with precise control of residence time and light intensity [5] [4]. | Flow specialty. Solves light penetration issues of batch photochemistry, enabling safe and scalable photochemical synthesis. |

| Automated Synthesis Platform with Robotic Liquid Handling | Executes precise reagent dispensing, mixing, and reaction setup for both plate-based batch and flow feed preparation. Integrates with AI design modules [6] [8]. | Cross-platform enabler. Automates the "Make" step in DMTA cycles for both paradigms. |

| In-line Process Analytical Technology (PAT) (e.g., FlowIR, UV) | Provides real-time monitoring of reaction progress, enabling immediate feedback and control, crucial for optimization and ensuring product consistency [5] [9]. | Flow advantage. Integral to continuous quality control and closed-loop autonomous optimization systems. |

| Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) Software | Uses AI/ML models to propose retrosynthetic pathways and predict reaction conditions from vast chemical databases [7] [9]. | Cross-platform planning tool. Informs route selection for both discrete batch and continuous flow execution. |

| Make-on-Demand (MADE) Building Block Catalogs | Virtual libraries of synthesizable compounds (e.g., >1 billion) providing access to vast chemical space without physical inventory, speeding up the sourcing step [7]. | Critical for "Design." Supports the exploration of novel chemical matter in both batch and flow synthesis campaigns. |

| Structured Reaction Data (FAIR Principles) | Machine-readable, well-annotated data on reactions (including failures) used to train predictive AI models and enable digital workflows [7] [9]. | Foundational for digitization. Essential for advancing both batch HTE analysis and autonomous flow chemistry systems. |

In the realm of automated synthesis for research and drug development, two principal methodologies dominate: the established approach of batch chemistry and the increasingly prominent flow chemistry [10]. The choice between them often centers on a fundamental trade-off. Batch chemistry is celebrated for its flexibility and simplicity, offering a straightforward, adaptable environment for exploratory research and multi-step reactions [4] [10]. In contrast, flow chemistry excels in providing superior control and safety, enabling precise management of reaction parameters and safer handling of hazardous processes [4] [5]. This guide objectively compares these platforms, providing structured data and experimental protocols to inform the selection process for scientists and development professionals.

Core Conceptual Comparison

The foundational difference lies in how reactions are conducted. Batch chemistry processes a set volume of material in a single vessel, making it a closed system. Flow chemistry, however, involves the continuous pumping of reagents through a reactor, representing an open system where reaction time is translated into residence time within the reactor space [4] [11].

This structural difference dictates their inherent strengths. Batch systems are inherently multifunctional; a standard round-bottom flask can accommodate a vast array of reaction types without reconfiguration [11]. Flow systems, with their improved heat and mass transfer from smaller reactor dimensions, offer unparalleled process intensification, allowing access to otherwise dangerous or inefficient chemistry [5] [11].

The Case for Batch Chemistry: Flexibility and Simplicity

Key Strengths and Characteristics

Batch chemistry's advantages make it the default choice for many research and development labs.

- Simple Setup and Operation: Most laboratories are inherently equipped for batch reactions, requiring only standard glassware, stirrers, and heating mantles [4] [10]. There is no need for specialized pumps or tubing systems.

- Exceptional Flexibility: It is ideal for exploratory synthesis where reaction conditions may need mid-course adjustments or for multi-step sequences that benefit from being contained in a single vessel [10]. This makes it suitable for a wide range of reaction types without re-engineering the setup.

- Low Initial Cost: The per-reaction cost is typically lower at small scales due to the use of existing, common lab equipment and the absence of specialized flow components [4] [10].

Experimental Context and Data

In practice, batch chemistry is frequently employed in the early stages of drug discovery. For instance, in medicinal chemistry, researchers often need to synthesize a library of analogous compounds by varying reagents or catalysts. A batch platform allows a chemist to run multiple parallel reactions in separate vials on a single stirrer hotplate, enabling rapid screening of reaction conditions with minimal setup time [4].

Table 1: Key Strengths of Batch Chemistry Platforms

| Strength | Description | Typical Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Setup [4] [10] | Uses common laboratory glassware & equipment. | Multi-parallel synthesis in vials or round-bottom flasks on a magnetic stirrer hotplate. |

| Operational Flexibility [10] | Easy mid-reaction adjustments; suitable for diverse, multi-step reactions. | Exploratory synthesis in drug discovery where reaction pathways are not fully defined. |

| Cost-Effectiveness [4] | Lower initial investment for low-throughput applications. | Academic research labs and small-scale custom synthesis. |

| Well-Established Protocols [10] | Extensive historical data and regulatory familiarity. | Process development for pharmaceutical filings based on traditional methods. |

The Case for Flow Chemistry: Control and Safety

Key Strengths and Characteristics

Flow chemistry addresses several key limitations of batch processing, particularly for optimized and scaled-up reactions.

- Enhanced Process Control: Flow systems provide precise, automated control over critical reaction parameters such as residence time, temperature, and mixing efficiency [10] [5]. This leads to highly consistent and reproducible results.

- Improved Safety Profile: By containing only a small volume of reactive material at any given time, flow reactors minimize the risks associated with exothermic reactions, high-pressure conditions, or the use of hazardous reagents [10] [5].

- Efficient and Seamless Scale-Up: Scaling a reaction from milligram to kilogram scale often simply involves running the flow process for a longer duration or operating multiple reactors in parallel, without the need to re-optimize the core reaction parameters [12] [5].

Experimental Context and Data

A compelling application of flow chemistry is in solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). A 2025 study demonstrated that Fast-Flow SPPS (FF-SPPS) outperforms traditional batch methods by packing the solid support in a static reactor and continuously flowing reagents through it [12]. This configuration eliminates back-mixing, allows for uniform heating to prevent aggregation, and enables real-time monitoring of reaction progress. The study reported that FF-SPPS could achieve effective couplings using only 1.2 equivalents of expensive amino acids, significantly reducing costs and waste compared to batch methods [12]. Furthermore, syntheses optimized at a 50 µmol scale were directly scaled to a 15 mmol scale without re-optimization, producing identical crude purities [12].

Table 2: Key Strengths of Flow Chemistry Platforms

| Strength | Description | Typical Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Precise Process Control [10] [5] | Excellent homogeneity & control over residence time, temperature, and pressure. | Photochemical reactions [5] and cryogenic reactions [10] requiring exact conditions. |

| Inherent Safety [10] [5] | Small in-process volume mitigates risks of exotherms and hazardous reagents. | Reactions involving azides, alkyl lithiums, or high-pressure conditions [5]. |

| Efficient Scale-Up [12] [5] | Scale-up by increasing runtime ("numbering up") without re-optimization. | Direct scale-up from lab-scale optimization to pilot-scale production, as in peptide synthesis [12]. |

| Process Intensification [5] [11] | Enables reactions in wider, safer process windows (high T/P). | High-temperature hydrogenations with short residence times, impossible in batch [11]. |

Direct Comparison: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

Side-by-Side Factor Comparison

The following table provides a consolidated, direct comparison of batch and flow platforms across critical factors for lab and production environments.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Batch vs. Flow Chemistry Platforms

| Factor | Batch Chemistry | Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible for mid-reaction adjustments [10] | Precise, automated control of parameters [10] |

| Scalability | Challenging; often requires re-optimization [10] | Seamless; scale by increasing runtime [12] |

| Safety | Higher risk for exothermic/hazardous reactions [10] | Safer; minimal reactive volume at any time [10] |

| Initial Cost | Lower (uses standard lab equipment) [4] [10] | Higher (requires pumps, reactors, sensors) [10] |

| Operational Cost | Higher per-batch downtime and cleaning [10] | Higher productivity and consistent quality [10] |

| Reagent Efficiency | Often requires excess reagents [12] | Can operate with near-stoichiometric reagents [12] |

| Reaction Optimization | Suitable for parallel screening of discrete conditions [4] | Ideal for dynamic, data-rich optimization of continuous variables [13] |

| Suitability for Solids | Generally good for reactions with solids [4] | Can be challenging, risk of reactor clogging [4] |

Workflow and Logical Relationship

The decision between batch and flow chemistry often follows a logical pathway based on the reaction characteristics and project goals. The following diagram visualizes this decision-making logic.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of either batch or flow chemistry requires specific materials and equipment. The following table details key components for a flow chemistry setup, particularly for high-throughput experimentation and optimization as highlighted in recent literature [5].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for a Flow Chemistry Platform

| Item | Function | Example in Application |

|---|---|---|

| Peristaltic or HPLC Pumps | Precisely meter and transport reagents through the flow system at a constant rate. | Used in a two-feed setup for a photoredox fluorodecarboxylation reaction to achieve kilo-scale production [5]. |

| Tubular/Microreactor | The core reaction channel where chemistry occurs; provides high surface-to-volume ratio. | A Vapourtec UV150 photoreactor with narrow tubing was used for efficient light penetration in a photochemical reaction [5]. |

| Variable Bed Flow Reactor (VBFR) | A specialized reactor for solid-phase synthesis that automatically adjusts volume as resin swells/shrinks. | Key component in Fast-Flow SPPS for synthesizing peptides like GLP-1, enabling direct scale-up from µmol to mmol scale [12]. |

| In-line Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Analyzes reaction stream in real-time (e.g., via IR, UV, NMR) for immediate feedback and control. | Quantitative in-line monitoring of Fmoc deprotection in FF-SPPS provides immediate insight into reaction progress [12]. |

| Back Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Maintains a consistent pressure within the flow system, allowing solvents to be heated above their boiling points. | Enables the use of solvents at temperatures far exceeding their atmospheric boiling points, accelerating reaction rates [5]. |

| Heating/Cooling Unit | Precisely controls the temperature of the reactor (e.g., a metal coil in a heated/cooled block). | Pre-heating of amino acids in FF-SPPS accelerates reaction kinetics and prevents aggregation [12]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Photoredox Reaction in Flow

This protocol is adapted from a reported procedure for a flavin-catalyzed photoredox fluorodecarboxylation, which was optimized via high-throughput screening and successfully scaled up in flow to kilogram output [5].

Objective

To safely and efficiently scale up a photoredox fluorodecarboxylation reaction from gram to kilogram scale using a continuous flow chemistry platform.

Methodology

- Step 1: High-Throughput Screening (Batch): Initial screening of 24 photocatalysts, 13 bases, and 4 fluorinating agents was conducted in a 96-well plate photoreactor to identify optimal reaction conditions. This identified a superior homogeneous photocatalyst that avoided clogging issues in subsequent flow steps [5].

- Step 2: Flow Reaction Setup: A two-feed flow system was assembled.

- Feed Solution A: Contains the substrate and the identified homogeneous photocatalyst.

- Feed Solution B: Contains the base and the fluorinating agent.

- The two feeds are merged using a T-mixer and then pumped through a commercially available photochemical flow reactor (e.g., Vapourtec UV150).

- Step 3: Parameter Optimization & Data Collection: The flow process was optimized by adjusting key parameters:

- Residence Time: Controlled by the combined flow rate of the two feeds and the reactor volume.

- Light Power Intensity: Varied to maximize conversion.

- Water Bath Temperature: The temperature of the reactor's cooling jacket was fine-tuned. Time-course 1H NMR data were collected to monitor conversion during optimization [5].

- Step 4: Scale-Up: The optimized conditions were maintained, and the process was simply run for a longer duration to achieve the desired output of 1.23 kg of product.

This protocol exemplifies the power of combining high-throughput screening with flow chemistry. The transition from microtiter plate screening to a kilogram-scale manufacturing process was achieved with minimal re-optimization, demonstrating flow chemistry's superior control and scalability for photochemical reactions [5].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics of batch and flow chemistry platforms, essential tools for modern research and drug development. It synthesizes current experimental data and practical methodologies to inform equipment selection and process development.

Core Concepts and Comparative Benefits

Batch and flow reactors represent two fundamentally different approaches to chemical synthesis. A batch reactor processes a set volume of material at a time, with reactions taking place in a single vessel like a round-bottom flask or a jacketed reactor system [4]. In contrast, a flow reactor is a continuous system where reagents are pumped through a tube or a channel, with the output limited only by operational time [4] [14].

The table below summarizes their inherent advantages, which guide their application in different research and development contexts.

| Feature | Batch Reactors | Flow Reactors |

|---|---|---|

| Setup & Flexibility | Generally easier to set up; great for parallel reactions [4] | More complex initial setup; enables automation [4] |

| Cost Consideration | Less expensive at any given scale [4] | Higher initial investment [4] |

| Handling Solids | Better for working with solids [4] | Can be prone to clogging [15] |

| Safety Profile | Larger reaction volume presents greater inherent risk [4] | Smaller reactive volume at any one time improves safety [4] |

| Scale-Up | Limited by vessel volume; can require re-optimization [4] [12] | Easier linear scale-up by running longer; often direct [4] [12] |

| Heat & Mass Transfer | Limited by vessel size and stirring efficiency [15] | Excellent due to high surface-to-volume ratio [14] |

| Specialty Chemistry | Standard equipment for most reactions | Fantastic for photochemistry and high-temperature/pressure reactions [4] [5] |

Experimental Performance Data and Protocols

Direct, comparative experimental data is crucial for evidence-based decision-making. The following section presents quantitative findings from studies that evaluated identical chemical reactions in both batch and flow modes.

Case Study: Selective Hydrogenation of Halogenated Nitroarenes

Selective hydrogenation is a critical transformation in fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis. The following table compiles results from a study comparing the hydrogenation of ortho-chloronitrobenzene (o-CNB) to ortho-chloroaniline (o-CAN) over supported metal catalysts in batch and continuous flow reactors [15].

Table 2: Catalytic Performance in Batch vs. Flow Hydrogenation of o-CNB

| Catalyst | Operation Mode | Pressure (atm) | Temperature (°C) | Selectivity to o-CAN (%) | Reaction Rate (mol/(mol~met~*h)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/C | Batch Liquid | 12 | 150 | 86 | 2910 |

| Au/TiO₂ | Batch Liquid | 12 | 150 | 100 | 167 |

| Au/TiO₂ | Continuous Gas | 1 | 150 | 100 | 12 |

Experimental Protocol

- Reaction System: Hydrogenation of o-chloronitrobenzene (o-CNB).

- Objective: To compare catalyst selectivity and activity between reactor types.

- Batch Method: Reactions were performed in a 100 mL stainless steel stirred autoclave. The reactor was charged with catalyst and o-CNB in ethanol, purged with H₂, and then pressurized and heated with vigorous stirring [15].

- Flow Method: A fixed-bed glass reactor with a 15 mm inner diameter was used. The catalyst was packed into the tube, and reagents were fed continuously in the gas phase at atmospheric pressure [15].

- Key Parameters Monitored: Substrate conversion and product selectivity (for o-CAN, aniline, and nitrobenzene) were analyzed, likely via gas chromatography (GC) or HPLC [15].

Data Interpretation

The data shows that while Pd/C in batch mode offers a much higher reaction rate, it suffers from significant dehalogenation, producing an undesirable 13% aniline byproduct. In contrast, Au/TiO₂ achieves perfect 100% selectivity in both modes but with vastly different reaction rates. The flow mode, operating at ambient pressure, provides a safer and more selective pathway, albeit with a lower activity, which can be compensated for by longer catalyst contact times.

Case Study: Peptide Synthesis - Batch SPPS vs. Fast-Flow SPPS

Solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical research. A comparative study of traditional batch SPPS and Fast-Flow SPPS (FF-SPPS) reveals significant performance differences [12].

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Peptide Synthesis

| Parameter | Batch SPPS | Fast-Flow SPPS (Vapourtec) |

|---|---|---|

| Resin Arrangement | Stirred freely in vessel | Packed in a static reactor |

| Typical Amino Acid Equivalents | Often requires large excess | Effective with 1.2 equivalents |

| Solvent Usage | Higher volume | ~70 mL per mmol per cycle |

| Crude Purity | Normal distribution of deletion impurities | Higher crude purity; target peptide favored |

| Scale-Up | Requires re-optimization | Direct from µmol to mmol scale |

| Process Monitoring | Offline analysis | Real-time, in-line monitoring of deprotection |

Experimental Protocol

- Reaction System: Synthesis of a model peptide, GLP-1.

- Objective: To demonstrate the efficiency and scalability of FF-SPPS.

- FF-SPPS Method: The resin is packed into a Variable Bed Flow Reactor (VBFR). Amino acid solutions, pre-heated and activated, are pumped sequentially through the static resin bed. The VBFR automatically adjusts its volume to accommodate resin swelling and shrinkage [12].

- Key Parameters Monitored: The system used in-line sensors to track Fmoc deprotection in real-time and monitored reactor volume changes to detect aggregation. A synthesis optimized at a 50 µmol scale was directly scaled to a 30 mmol scale without re-optimization [12].

Hardware and Methodology Deep Dive

Understanding the specific hardware components and their integration is key to leveraging these technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key components and reagents used in advanced flow chemistry setups, referencing the experimental protocols from the search results.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Flow Chemistry

| Item | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Jacketed Batch Reactor | Provides temperature control for batch reactions via a circulating fluid. | Used for benchmark hydrogenation reactions with Pd/C catalyst [4] [15]. |

| Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) | Ideal for reactions requiring efficient mixing and steady-state data collection. | A 2.65 mL m-CSTR was used for kinetic studies of imine synthesis [16]. |

| Static Mixer / Tubular Reactor | Provides continuous flow with no moving parts; excellent for plug-flow conditions. | Used for photoredox reactions and scaling peptide synthesis [4] [5]. |

| Packed Bed Reactor | A tube filled with heterogeneous catalyst or resin for solid-phase synthesis. | Used for gas-phase hydrogenation and Fast-Flow SPPS [12] [15]. |

| Syringe Pumps | Deliver precise and continuous flow rates of reagents. | Employed in the m-CSTR RTD and photoredox fluorodecarboxylation studies [16] [5]. |

| In-situ Raman Spectrometer | Provides real-time, quantitative reaction monitoring. | Integrated with the m-CSTR to track imine synthesis kinetics [16]. |

| Variable Bed Flow Reactor (VBFR) | Automatically adjusts volume to accommodate resin swelling/shrinkage in flow SPPS. | Key hardware enabling the scalability and efficiency of FF-SPPS [12]. |

Experimental Workflow for Reactor Characterization and Kinetic Studies

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for setting up a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) and using it for kinetic studies, as demonstrated in the imine synthesis case study [16].

The choice between batch and flow chemistry is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more suitable for a specific application. The following diagram provides a logical framework for this decision, synthesized from the analyzed literature [4] [15].

In conclusion, batch reactors remain the versatile and cost-effective choice for many traditional lab-scale reactions, particularly when working with solids or when existing equipment and protocols are adequate. Flow reactors, including microreactors and CSTRs, excel in process intensification, safety, and scalability, offering superior control and opening new avenues in chemical space. The optimal choice is dictated by the specific chemical, operational, and economic constraints of the project.

In the development of automated synthesis platforms, a fundamental distinction lies in the process architecture: batch systems, characterized by dynamic concentration gradients, versus continuous flow systems, defined by their steady-state operation. This divergence is not merely operational but influences every aspect of process development, from reaction selectivity and safety to scalability and control strategies. Within the pharmaceutical industry and research laboratories, the choice between these paradigms significantly impacts development timelines, product quality, and economic viability [17] [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these inherent characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their platform selection process.

Core Conceptual Comparison

Batch Processing with Concentration Gradients: In traditional batch chemistry, all reactants are combined at the initiation of the reaction within a single vessel. This creates a system where reactant concentrations are initially high and continuously decrease as the reaction progresses, while product concentrations increase. This dynamic environment is defined by transient concentration and temperature profiles [17] [18]. A significant drawback is potential back-mixing, where finished product can contact fresh reagents, leading to decreased selectivity and yield as by-products form [18].

Continuous Flow with Steady-State Operation: In continuous flow chemistry, reactants are constantly pumped into a reactor, and products are continuously withdrawn. After an initial start-up period, the system reaches a steady state, where concentrations and temperature at any given point in the reactor remain constant over time [18] [19]. This ensures that every molecule of product experiences identical reaction conditions as it travels through the reactor, promoting uniform product quality and simplifying process control [17] [10].

Quantitative Comparison of Process Characteristics

The table below summarizes key quantitative and qualitative differences between batch and flow chemistry based on inherent process characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Batch and Flow Process Characteristics

| Characteristic | Batch Process | Continuous Flow Process |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration Profile | Dynamic gradients; high-to-low reactant concentrations [17] | Constant, steady-state concentrations during operation [19] |

| Mixing & Heat Transfer | Limited by vessel size and agitator; poor heat transfer can create hot spots [10] | Superior heat transfer due to high surface-to-volume ratio; efficient mixing [18] [20] |

| Residence Time Distribution | Broad; all molecules have varying reaction times | Narrow and precisely controlled by flow rate [10] |

| Process Control & Monitoring | Off-line sampling or mid-reaction adjustments; unsteady-state operation [10] | Facilitates real-time, in-line monitoring with Process Analytical Technology (PAT) [19] [21] |

| Reaction Selectivity & Yield | Can be compromised by local concentration gradients and poor heat transfer | Often improved through precise control of reaction parameters [22] |

| Safety | Large volume of hazardous materials present at once; risk of runaway reactions [10] | Small reactor hold-up volume minimizes risk; enables inherently safer design [17] [22] |

| Scale-up Methodology | Non-linear; requires re-optimization due to changing mixing/heat transfer dynamics [10] | Linear; often achieved by numbering up (parallel reactors) or prolonged operation [10] [4] |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

Mesalazine API Synthesis: A Model for PAT Integration

The synthesis of Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) demonstrates the application of advanced process control in a multistep flow process, enabling real-time quantification of species and dynamic control.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multistep Flow Synthesis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in the Process |

|---|---|

| 2-chlorobenzoic acid (2ClBA) | Starting material for the synthetic sequence [21] |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) in H₂SO₄ | Nitrating agent for the first transformation [21] |

| Isopropyl Acetate (iPrOAc) | Solvent for liquid-liquid extraction after nitration [21] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Reagent for hydrolysis and acid-base extraction [21] |

| Heterogeneous Catalyst (CSMs) | Catalytic Static Mixers for the hydrogenation step [21] |

| In-line NMR Spectrometer | Monitors nitration reaction and quantifies species via Indirect Hard Modeling (IHM) [21] |

| In-line IR & UV/Vis Spectrometers | Monitor hydrolysis and hydrogenation steps, respectively [21] |

| Membrane Separators | Enable continuous, small-volume phase separations [21] |

Experimental Protocol:

- Process Setup: A continuous flow system was assembled with modules for nitration, hydrolysis, and hydrogenation, integrated with in-line PAT tools (NMR, IR, UV/Vis) and membrane separators [21].

- Nitration and Monitoring: 2ClBA and nitrating acid were pumped through a microreactor. The effluent was quenched and extracted with iPrOAc/H₂O. The organic phase was analyzed by in-line NMR before a subsequent base extraction [21].

- Data Processing: An Indirect Hard Model (IHM) was applied to the complex NMR data, allowing real-time quantification of the desired product (5N-2ClBA), starting material, and a regioisomer impurity (3N-2ClBA) with high accuracy [21].

- Dynamic Control: The PAT data revealed a real-time process deviation: acid carry-over from the first separator was partially neutralizing the NaOH stream. The system was designed to automatically adjust the NaOH input concentration to compensate for this, maintaining the process at the desired steady state [21].

Photoredox Fluorodecarboxylation

This case highlights a hybrid approach using High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for screening, followed by flow for scale-up.

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial HTE Screening: Reactions were conducted in a 96-well plate-based photoreactor to rapidly screen 24 photocatalysts, 13 bases, and 4 fluorinating agents [5].

- Batch Validation & DoE: Promising "hits" from the screen were validated in a batch reactor and further optimized using a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach [5].

- Transfer to Flow: The optimized conditions were transferred to a continuous flow photoreactor. Parameters such as residence time and light intensity were fine-tuned, enabling a smooth scale-up from a 2-gram to a 1.23-kilogram output, demonstrating the scalability of the steady-state flow process [5].

Visualization of Process Characteristics and Control

The following diagrams illustrate the core differences in concentration profiles and a advanced process control workflow for steady-state operation.

Diagram 1: Concentration profiles in batch versus flow processes. The batch process shows a dynamic temporal profile, while the flow process maintains a constant spatial profile at steady state.

Diagram 2: A feedback control loop for maintaining steady-state operation. This data-driven approach uses real-time analytics and model-based control to automatically correct deviations.

The choice between batch and flow chemistry is not a matter of superiority, but of aligning the process technology with the project's goals. Batch processing, with its inherent concentration gradients, offers flexibility and simplicity for early-stage research, low-volume production, and reactions involving significant solids [10] [4]. However, continuous flow chemistry provides a paradigm of control through steady-state operation. Its advantages in safety, scalability, reproducibility, and integration with modern PAT and control strategies make it exceptionally suitable for optimized, high-volume production, and for managing hazardous chemistries [17] [10] [22].

A growing trend involves leveraging the strengths of both: using batch-like HTE for rapid initial reaction screening and discovery, followed by transfer to a continuous flow platform for process intensification and scalable production [5]. As the chemical industry moves towards greater digitization and automation, the ability of flow chemistry to generate consistent, high-quality data and maintain precise control under steady-state conditions positions it as a cornerstone of modern, data-driven pharmaceutical development and manufacturing [19] [20] [21].

Automated Synthesis in Action: Key Applications in Pharmaceutical R&D

Photochemistry, which uses light to drive chemical reactions, is a powerful tool in modern synthetic chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry for constructing complex molecules. However, its potential has long been constrained by fundamental limitations of traditional batch reactors. The emergence of continuous flow photochemistry represents a transformative approach that directly addresses these core challenges, enabling unprecedented control, efficiency, and scalability for light-driven chemical transformations.

The central problem with traditional batch photochemistry lies in the inherent inefficiency of light penetration. In round-bottom flasks, light cannot penetrate evenly; only the outer layers of the solution receive adequate irradiation, while the core remains under-irradiated. This phenomenon, governed by the Beer-Lambert Law, becomes progressively worse as reaction scale increases, leading to inconsistent reaction outcomes, prolonged reaction times, and significant formation of by-products through over-irradiation of outer layers [23] [24]. Additionally, safety concerns regarding UV lamp hazards and unpredictable reactive intermediates in bulk solutions have further limited widespread adoption of photochemical methods in industrial settings [24].

Flow photochemistry fundamentally reengineers this process by circulating reactants through narrow, transparent channels where they receive uniform irradiation. This review provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional batch and modern flow photochemistry platforms, examining their respective capabilities through quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to guide researchers and development professionals in selecting optimal technologies for their photochemical applications.

Fundamental Principles: How Flow Overcomes Batch Limitations

The Physics of Light Penetration

The core advantage of flow photochemistry stems from its ability to overcome the light penetration constraints that plague batch systems. In traditional batch photoreactors, light intensity decreases exponentially as it travels through the reaction medium according to the Beer-Lambert Law. This results in a steep photon gradient where molecules near the vessel walls receive intense irradiation while those in the center remain in relative darkness [23]. The consequence is simultaneous under-irradiation and over-irradiation within the same vessel, leading to poor selectivity, extended reaction times, and product decomposition [23] [24].

Flow reactors address this fundamental limitation through miniaturization of the optical path. By reducing reactor dimensions to millimeter or sub-millimeter scales, the distance light must travel through the reaction medium is dramatically shortened, ensuring nearly uniform photon flux throughout the entire reaction volume [23]. This precise control over light exposure enables highly reproducible reaction conditions that are maintained consistently throughout the reaction process and during scale-up.

Enhanced Mass and Heat Transfer

Beyond improved photonic efficiency, flow photochemistry provides superior mass and heat transfer characteristics compared to batch systems. The confined dimensions of flow reactors create high surface-area-to-volume ratios that facilitate rapid heat exchange, effectively dissipating heat generated by exothermic reactions or from the light source itself [25] [24]. This precise temperature control is particularly valuable for photochemical transformations involving thermally sensitive intermediates or products.

Similarly, the streamlined flow patterns within microreactors enable efficient mixing and reduced diffusion paths, ensuring homogeneous concentration distributions throughout the reaction process. This combination of uniform illumination, temperature control, and mixing creates an optimized environment for photochemical transformations that is virtually impossible to achieve in conventional batch reactors [23].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Batch vs. Flow Photochemistry

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

The theoretical advantages of flow photochemistry translate into measurable performance improvements across multiple critical parameters. The table below summarizes direct comparisons between batch and flow approaches based on experimental data from the literature:

Table 1: Performance comparison between batch and flow photochemistry

| Parameter | Batch Photochemistry | Flow Photochemistry | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Penetration | Exponential decay with path length | Uniform throughout reactor | Beer-Lambert law [23] |

| Path Length | Centimeters (cm) | Sub-millimeter to millimeter (mm) | Microreactor dimensions [23] |

| Surface Area:Volume | Low (5-100 m⁻¹) | Very high (100-10,000 m⁻¹) | Microreactor design [25] |

| Temperature Control | Limited, gradient formation | Precise, uniform heating/cooling | Enhanced heat transfer [25] [24] |

| Reaction Time | Hours (h) | Minutes to seconds (min/s) | Reduced irradiation time [5] [24] |

| Scalability | Nonlinear, requires re-optimization | Linear, numbering-up or prolonged operation | Scale-up strategies [23] |

| Safety Profile | Bulk hazardous intermediates | Small volume of intermediates at any time | Process intensification [25] [20] |

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Scale-Up

A compelling example of flow photochemistry's advantages comes from the development and scale-up of a flavin-catalyzed photoredox fluorodecarboxylation reaction [5]. Researchers initially employed high-throughput experimentation (HTE) using 96-well plate-based reactors to screen 24 photocatalysts, 13 bases, and 4 fluorinating agents. After identifying optimal conditions, the process was transferred to a Vapourtec UV-150 flow photoreactor, achieving 95% conversion on a 2g scale [5].

Through systematic optimization of flow parameters including light power intensity, residence time, and temperature, the process was successfully scaled to produce 1.23 kg of the desired product at 97% conversion and 92% yield, corresponding to a throughput of 6.56 kg per day [5]. This case demonstrates how flow photochemistry enables direct scale-up from screening to production without re-optimization, a significant advantage over batch processes where scale-up typically requires extensive re-optimization and faces substantial photon efficiency challenges.

Experimental Platforms and Methodologies

Flow Photochemistry Setup and Workflow

A typical flow photochemistry system consists of several integrated components that work together to create a continuous, controlled photochemical process. The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflow and component relationships in a standardized flow photochemistry setup:

Diagram Title: Flow Photochemistry System Components

The experimental workflow begins with preparation of reagent solutions, which are then pumped through the system at precisely controlled flow rates. These solutions meet in a mixing unit before entering the photochemical reactor, where they are exposed to controlled irradiation for a specific residence time. The product stream exiting the reactor can be monitored in real-time using integrated Process Analytical Technology (PAT) before final collection [24] [26].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Implementing a robust flow photochemistry system requires specific components designed to handle the unique demands of photochemical transformations. The table below details essential materials and their functions based on established platforms:

Table 2: Essential research reagents and components for flow photochemistry

| Component | Specification | Function | Example Products/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Reactor | UV-transparent tubing (FEP, PFA, quartz) | Contains reaction mixture with optimal light penetration | Vapourtec UV-150 [24] |

| Light Source | LEDs or mercury lamps with specific wavelengths | Provides controlled irradiation for photochemical reactions | Interchangeable LED arrays (365-650 nm) [24] |

| Precision Pump | High-accuracy syringe or piston pumps | Controls reagent flow rates and residence times | Commercially available flow systems [5] |

| Temperature Controller | Peltier coolers or heating jackets | Maintains precise reaction temperature | Integrated cooling in UV-150 [24] |

| Process Analytics | Inline FTIR, UV-Vis, or NMR | Real-time reaction monitoring and yield prediction | Inline FTIR systems [26] |

| Safety Enclosure | Light-proof casing with interlocks | Contains UV radiation and protects operators | Commercial reactor safety features [24] |

Protocol: Automated Optimization with Real-Time Analytics

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with flow photochemistry to create autonomous optimization platforms. One notable approach combines inline Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy with neural network models for real-time yield prediction and reaction optimization [26].

The methodology involves:

- Spectral Library Generation: FTIR spectra of pure starting materials and products are measured to create a reference library.

- Linear Combination Training: Simulated reaction spectra are generated through linear combinations of reference spectra corresponding to different conversion levels.

- Model Training: A neural network is trained on these simulated spectra to predict reaction yields from real-time FTIR measurements.

- Closed-Loop Optimization: The trained model guides an automated system to continuously adjust reaction parameters (flow rate, temperature, concentration) toward optimal performance [26].

This integrated approach dramatically reduces optimization time and enables adaptive control of photochemical processes, maintaining optimal performance even in the face of variable input conditions or catalyst degradation.

Application Spectrum and Industrial Adoption

Photochemical Transformations Enabled by Flow

Flow photochemistry has demonstrated particular utility for several challenging photochemical transformations that are difficult to execute reliably in batch systems. These include:

Photoredox Catalysis: Transition metal (e.g., Ir, Ru) or organic photocatalysts that undergo single-electron transfer processes under visible light irradiation [23] [24]. The precise control of flow systems minimizes catalyst decomposition and improves selectivity in these radical-mediated transformations.

[2+2] Cycloadditions: Photochemical cycloadditions that often require UV irradiation and benefit from the short, uniform path lengths in flow reactors to prevent side reactions and improve yields [24].

Singlet Oxygen Generation: Photosensitized production of singlet oxygen for oxidation reactions, where flow systems provide efficient gas-liquid mixing and controlled irradiation times [24].

Halogenation Reactions: UV-promoted bromination or chlorination that can be safely contained in flow systems with minimal risk of over-halogenation [24].

Complex Molecule Synthesis: Multi-step sequences involving photochemical steps, such as the synthesis of vitamin D analogues and pharmaceutical intermediates [24].

The integration of photochemistry with other activation modes in flow, such as electrochemical or thermal activation, further expands the synthetic toolbox available to researchers [23]. These integrated approaches enable reaction sequences that would be challenging or impossible to perform using traditional batch methods.

Industrial Implementation and Scale-Up Strategies

Flow photochemistry has gained significant traction in industrial settings, particularly within pharmaceutical and specialty chemical sectors. Companies including Pfizer and Merck have integrated flow reactors into their research and development pipelines, reporting yield improvements up to 30% and reduced development timelines compared to batch processes [27].

Three primary scale-up strategies have emerged for flow photochemistry:

Numbering-Up: Parallel operation of multiple identical reactor units to increase production capacity without changing reaction conditions [23].

Prolonged Operation: Continuous operation of a single reactor for extended periods (hours to days) to accumulate product [5].

Smart Dimensioning: Hybrid approach that increases reactor dimensions while preserving the beneficial micro-environment for photochemistry [23].

The successful kilogram-scale production of pharmaceutical intermediates, as demonstrated in the fluorodecarboxylation case study [5], highlights the industrial viability of flow photochemistry for manufacturing applications. Regulatory support for continuous manufacturing from agencies like the U.S. FDA has further accelerated adoption in regulated industries [27].

The transition from batch to flow photochemistry represents a fundamental shift in how photochemical processes are designed, optimized, and scaled. By addressing the core limitations of light penetration, heat management, and scalability inherent to batch systems, flow photochemistry enables more efficient, reproducible, and controllable photochemical transformations.

The integration of flow platforms with advanced analytics, machine learning, and automation creates a powerful ecosystem for photochemical reaction development that aligns with the evolving needs of modern chemical research and manufacturing. As the technology continues to mature, flow photochemistry is poised to become the standard approach for implementing photochemical transformations across academic, pharmaceutical, and industrial settings, ultimately expanding the synthetic toolbox available for creating complex molecular architectures.

The strategic selection of reactor technology is fundamental to advancing synthetic chemistry, particularly for high-pressure gas-liquid reactions like hydrogenation. Within the broader research context of comparing batch versus flow automated synthesis platforms, this guide provides an objective performance comparison of these two paradigms. Continuous flow chemical synthesis is recognized for possessing attributes that grant it superiority over batch processes in several respects, notably in safety and process intensification [9]. The drive to digitize and automate synthesis aims to push these enabling technologies further into a more efficient modern chemical world [9]. While batch processing has been the traditional backbone of laboratory and industrial synthesis, continuous flow in compact reactors presents a compelling alternative, especially for reactions involving gases like hydrogen. This guide will compare the performance of these systems based on key operational and safety parameters, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

High-pressure reactors for gas-liquid reactions are primarily categorized into batch and continuous flow systems, each with distinct configurations and operating principles.

High-Pressure Batch Reactors

Batch reactors are characterized by their contained vessel design, where all reactants are loaded simultaneously, and the reaction proceeds over time.

- Stirred Tank Reactors (Autoclaves): These are the most common type, where an agitator system mixes the gas and liquid phases within a pressurized vessel. A special sparger at the bottom is often used to introduce hydrogen gas into the system, and they are ideal for small-capacity plants and slow, selective processes [28]. They are available in a wide range of sizes, from benchtop units like the Asynt compact reactors [29] to large industrial systems.

- Loop Reactors: In this design, reactants and catalyst are vigorously circulated through a venturi loop, resulting in a high-speed spontaneous reaction. These systems typically include a candle filter to separate the catalyst from the reaction products and are better suited for full hydrogenation with low residence time [28].

Compact Continuous Flow Reactors

Continuous flow reactors process reagents in a steady stream, offering a fundamentally different approach with several sub-types.

- Tubular Reactors (Single Towers): In these systems, the liquid feedstock and hydrogen gas are fed continuously from one end of a tower, and the hydrogenated material is discharged from the other. They are typically preferred for large-capacity plants and are the only type that supports full automation [28].

- Tube-in-Tube Membrane Reactors: This innovative design features a semipermeable Teflon AF-2400 inner tube within an outer housing. The reactive gas diffuses through the gas-permeable membrane, achieving rapid gas-liquid mass transfer rates (on the order of 10-30 seconds) without direct contact between the gas and liquid streams [30]. This creates a well-defined interface, circumventing issues like surface rippling and enabling precise kinetic studies.

Performance Comparison: Batch vs. Flow Reactors

The table below summarizes a direct, objective comparison of key performance indicators for batch and flow reactors in the context of high-pressure gas-liquid reactions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Batch and Continuous Flow Reactors for Gas-Liquid Reactions

| Performance Indicator | Batch Reactors | Continuous Flow Reactors |

|---|---|---|

| General Safety | Relies on pressure relief valves and rupture discs; larger volume poses greater risk [18] [31]. | Small hold-up volume; pressure relief stops pumps, minimizing risk (inherently safer design) [9] [17] [18]. |

| Pressure & Temperature Control | Controlled via internal controllers and safety heads with rupture discs [32]. | Precisely controlled using back pressure regulators (BPRs) and mass flow controllers (MFCs) [33]. |

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Lower surface-area-to-volume ratio; can lead to hot spots and requires lower temperature coolants [18]. | High surface-area-to-volume ratio; excellent heat transfer allows use of higher temperature coolants [17] [18]. |

| Mass Transfer Efficiency | Can be limited; depends on agitator design and gas introduction method [31]. | Excellent due to small dimensions; enables approach to kinetic rate limit [17] [30]. |

| Reaction Time Scale | Minutes to hours (e.g., diphenhydramine HCl: 5h batch vs. 15min flow) [9]. | Seconds to minutes; significantly faster than batch [9]. |

| Footprint & Inventory | Larger footprint; full raw material inventory committed at start [18]. | Compact (10-20% of batch); low in-process inventory [18]. |

| Solids Handling | Generally handles solids well. | A significant inherent technical challenge; can clog systems [17]. |

| Catalyst Consumption | Minimizes nickel catalyst consumption in hydrogenation [28]. | Catalyst is often packed in a fixed bed; continuous consumption in homogeneous systems. |

| Ease of Scale-Up | Linear scale-up can be challenging due to changing heat/mass transfer [31]. | Numbered-up by running multiple units in parallel; more straightforward [17]. |

| Automation & Digitization | Extensive manual preparation steps; less compatible with full automation [18]. | Highly amenable to automation and machine-learning-driven optimization [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Reactor Performance Analysis

Protocol: Determination of Fast Gas-Liquid Reaction Kinetics in a Tube-in-Tube Flow Reactor

This protocol, adapted from Zhang et al., details how to measure intrinsic reaction kinetics in flow, providing data for objective reactor comparison [30].

- Objective: To determine the kinetic rate constant (k) for a fast gas-liquid reaction under pseudo-first-order conditions.

- Principle: A tube-in-tube reactor with a Teflon AF-2400 membrane provides a well-defined gas-liquid interface. By measuring the steady-state gas uptake flux at different liquid flow rates and applying a film theory model, the kinetic parameters can be deconvoluted from mass transfer resistances.

- Materials & Setup:

- Reactor: Tube-in-tube reactor with inner Teflon AF-2400 tubing (O.D. 0.8 mm, I.D. 0.6 mm) inside an outer PTFE tube, length 0.7 m.

- Pumping System: Syringe pump for liquid feed.

- Gas Delivery: Regulated gas cylinder with a thermal mass flow meter.

- Pressure Control: Back pressure regulator (BPR) on liquid outlet.

- Environment: Stirred water bath for isothermal operation.

- Procedure:

- Degassing: Degas the liquid feed to remove dissolved air.

- System Setup: Pressurize the gas side using the inlet regulator. Close the gas outlet shut-off valve so the gas pressure is controlled solely by the inlet regulator. Set the liquid side pressure using the BPR.

- Data Collection: For a constant liquid flow rate, allow the system to reach steady state. Record the constant gas flux (FG) measured by the flow meter.

- Parameter Variation: Repeat the measurement at multiple liquid flow rates.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the gas mass transfer flux (NA) from the measured FG.

- Determine the overall mass transfer coefficient (K) using the equation derived from the Danckwerts model:

N_A = K H P_A(where H is Henry's constant and P_A is gas pressure). - Deconvolute the liquid-side mass transfer coefficient with reaction (kL') from the overall coefficient using the resistance-in-series model.

- Calculate the Hatta number (Ha) and subsequently the pseudo-first-order rate constant (k') and the second-order rate constant (k).

Protocol: Gas-Liquid Mass Transfer Study using Digital Holographic Interferometry

This protocol describes a method for visualizing and quantifying mass transfer, which is critical for evaluating and scaling up both batch and flow reactors [34].

- Objective: To visualize the formation of the diffusion layer and estimate physico-chemical parameters (e.g., diffusion coefficients, kinetic constants) during gas-liquid absorption.

- Principle: The absorption of a gas into a liquid changes the liquid's refractive index. Digital holographic interferometry visualizes these changes, allowing quantitative analysis of the concentration field near the gas-liquid interface.

- Materials & Setup:

- Absorption Cell: A Hele-Shaw cell (two transparent plates separated by a narrow gap ~1.9 mm).

- Imaging: A Mach-Zehnder interferometer to visualize refractive index variations.

- Image Processing: A custom code to extract quantitative data from interferograms.

- Procedure:

- Calibration: Determine a calibration curve correlating solution concentration to refractive index using a refractometer.

- Experiment: Inject the liquid solution into the cell and introduce the gas. Use the interferometer to record the bending of interference fringes over time.

- Modeling: Propose a 1-D mass transfer model coupling diffusion and reaction in the liquid phase.

- Data Analysis:

- Image Processing: Convert the recorded fringe patterns into 2D maps of refractive index variation.

- Parameter Estimation: Use a non-linear least-square fitting method to compare experimental results with the model simulation and estimate key physico-chemical parameters.

Visualization of Reactor Systems and Safety

To elucidate the core concepts and safety architectures of these systems, the following diagrams provide a clear visual comparison.

Diagram 1: Batch reactor safety and control systems include passive and active pressure relief devices and internal monitoring sensors [29] [31] [32].

Diagram 2: Continuous flow reactor pressure is precisely controlled by a back pressure regulator, with hydrogen gas metered in via a mass flow controller [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting high-pressure gas-liquid reactions safely and effectively in a research setting.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for High-Pressure Gas-Liquid Reactions

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium on Carbon (Pd/C) | A common heterogeneous catalyst for hydrogenation reactions [31]. | Can be pyrophoric; requires careful handling and inert storage [31]. |

| Raney Nickel | A versatile, high-activity catalyst for hydrogenations [31]. | Highly pyrophoric; stringent safety protocols for storage and disposal are required [31]. |

| Teflon AF-2400 Tubing | A gas-permeable membrane used in tube-in-tube reactors to achieve high mass transfer [30]. | Enables precise kinetic studies by creating a defined gas-liquid interface [30]. |

| Back Pressure Regulator (BPR) | A valve used to maintain precise pressure in a continuous flow system [33]. | Critical for controlling reactor pressure and ensuring consistent reaction conditions [33]. |

| Stainless Steel (316/17-4-PH) | Standard material of construction for high-pressure reactor vessels [32]. | Offers durability, corrosion resistance, and the ability to withstand high temperatures and pressures [29] [32]. |

| Mass Flow Controller (MFC) | A device that measures and controls the flow rate of a gas [33]. | Essential for the safe and accurate delivery of hydrogen gas in both batch and flow systems [33] [31]. |

The objective comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that both batch and continuous flow reactors have distinct roles in the landscape of automated synthesis for high-pressure gas-liquid reactions. Batch reactors offer versatility and are well-suited for small-scale production, process development, and reactions involving solids. In contrast, continuous flow reactors excel in safety, process intensification, heat and mass transfer efficiency, and are inherently more suited for full automation and digitization [9] [17] [18].

The choice between these technologies is not a simple binary decision but a strategic one. It must be guided by the specific reaction requirements, production scale, safety considerations, and long-term process economics. As the field moves towards increasingly digitized and automated platforms, the integration of flow reactors with machine-learning-driven optimization and computer-aided synthesis planning is poised to become a cornerstone of modern chemical research and pharmaceutical development [9].

In synthetic chemistry, the pursuit of novel molecules and more efficient processes often hinges on the ability to work with highly reactive intermediates. These species, including organolithium compounds, diazonium salts, and organic azides, enable transformations inaccessible through stable reagents but present significant safety and handling challenges. The choice of reaction platform—traditional batch versus continuous flow—fundamentally influences how chemists manage these reactive species, impacting not only safety but also yield, selectivity, and scalability. Flow chemistry has emerged as a powerful tool for handling such intermediates, leveraging miniaturization, enhanced mixing, and precise control to access novel chemical space while mitigating risks associated with these energetic species [5] [35]. This guide objectively compares both platforms across key reaction classes critical to pharmaceutical and fine chemical development, providing experimental data to inform platform selection.

Technical Comparison of Synthesis Platforms

The fundamental differences between batch and flow reactors create distinct advantages and limitations for handling reactive intermediates. Batch reactors, the traditional tool of synthetic chemists, process a discrete volume of material in a single vessel, offering simplicity and flexibility for reaction screening [10] [4]. Continuous flow reactors pump reagents through confined channels or tubes, enabling continuous product output [10]. This continuous operation provides superior heat and mass transfer due to high surface-area-to-volume ratios, a critical factor for controlling fast, exothermic reactions [5] [36].

For reactive intermediates, the small hold-up volume (typically milliliters) in flow reactors minimizes the accumulation of hazardous species, inherently improving process safety [17]. Furthermore, flow systems enable precise control over reaction parameters including residence time, temperature, and mixing, allowing intermediates to be generated and consumed under optimized conditions that are often unattainable in batch [5]. This is particularly valuable for photochemical reactions, where flow reactors provide uniform irradiation of the reaction mixture, overcoming light penetration issues inherent to batch photochemistry [5] [36].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Batch and Flow Platforms for Reactive Intermediates

| Characteristic | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Reactor Volume | Discrete, large volume (mL to L) | Continuous, small hold-up volume (µL to mL) |

| Heat Transfer | Limited, prone to hot spots | Excellent, efficient heat dissipation |

| Mixing Efficiency | Dependent on stirrer speed/reactor design | Superior, rapid mixing via miniaturization |

| Process Control | Adjustable mid-reaction but less precise | Highly precise control of time, temperature, and mixing |

| Safety Profile | Higher risk due to larger reagent inventory | Inherently safer; minimal accumulation of hazardous materials |

| Handling Solids | Generally straightforward | Challenging, can lead to clogging |

Comparative Analysis by Reaction Class

Organolithium Chemistry

Organolithium reagents are powerful nucleophiles used widely in carbon-carbon bond formation, but their high reactivity and thermal instability necessitate cryogenic conditions and careful handling in batch processes [36]. Flow chemistry transforms this paradigm by leveraging rapid mixing and short residence times to safely handle these species at significantly higher temperatures.

Experimental Protocol (Flow): A solution of the starting material (e.g., an aryl halide) and a solution of n-BuLi in hexanes are separately loaded into syringes or pumps. The streams are combined in a T-mixer or a microreactor chip at a controlled temperature (-20°C to 0°C). The resulting organolithium intermediate flows through a residence time unit (e.g., a coiled tube) for a precisely defined period (seconds to minutes) before being quenched in-line with an electrophile solution (e.g., an aldehyde, ketone, or DMF). The outlet stream is collected and worked up to isolate the product [36].

Representative Data: In a direct comparison, a reaction using n-BuLi that yielded only 32% in a batch reactor at -78°C was successfully carried out in flow at a considerably warmer -20°C, achieving a 60% yield. This demonstrates flow's ability to provide both safer operation and superior throughput [36].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Organolithium Reactions

| Parameter | Batch Process | Flow Process |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Temperature | -78°C | -20°C to 0°C |

| Reaction Scale | Limited by cooling efficiency | Easily scalable by numbering-up or prolonged operation |

| Mixing Efficiency | Moderate, depends on stirring | Very high, rapid micromixing |

| Yield (Example) | 32% | 60% |

| Safety | Risk of thermal runaway in large scale | Inherently safer; small volume of reactive intermediate |

Diazotization and Diazonium Chemistry

Diazonium salts, valuable intermediates for introducing halogens, cyano, and hydroxyl groups, are notoriously unstable and can decompose explosively in their solid form or in concentrated solutions [37] [38]. Batch synthesis requires slow, careful addition of reagents and intensive cooling to minimize risks. Flow chemistry addresses these challenges by generating diazonium intermediates on-demand and consuming them immediately, preventing dangerous accumulation.

Experimental Protocol (Flow): A solution of the aromatic amine in acid (e.g., HCl) and a solution of sodium nitrite in water are pumped via separate inlets into a primary reactor (e.g., a microreactor or tube) maintained at 0-5°C. The resulting diazonium salt stream is immediately mixed in-line with a solution of the nucleophile (e.g., CuBr for bromination, KI for iodination, or HBF4 for the Balz-Schiemann reaction). This second mixture passes through a heated reactor to facilitate the substitution or coupling reaction. The outlet is collected for workup [36].

Representative Data: A specific diazotization reaction that provided only a 56% yield in batch was scaled in flow to produce 1 kg of product in 8 hours with a 90% yield, showcasing dramatic improvements in both efficiency and safety [36].

Diagram 1: Flow setup for diazotization and subsequent reaction, enabling safe on-demand handling of unstable diazonium salts.

Azide Chemistry

Organic azides are essential for click chemistry and the synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles, but they are potentially explosive, shock-sensitive, and toxic [5] [36]. Batch processes often suffer from slow mass transfer when using aqueous sodium azide with organic substrates. Flow chemistry enables the instantaneous generation and consumption of azides, or the safe handling of organic azide reagents in small volumes.

Experimental Protocol (Flow - Telescoped Synthesis): A solution of an alkyl halide or sulfonate and a solution of sodium azide in water are pumped into a microreactor. The high interfacial area enables rapid and safe phase-transfer azidation. The resulting stream containing the organic azide can be directly telescoped into a subsequent reactor (e.g., for a Curtius rearrangement or a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition) without isolation, minimizing the need to handle or concentrate the energetic intermediate [36].

Representative Data: While quantitative yield comparisons are not provided in the search results, the academic and industrial literature consistently reports that flow processes for azide transformations achieve high yields with significantly improved safety profiles, allowing for the scaling of reactions that would be considered too hazardous in batch [5] [17].

Table 3: Safety and Handling Comparison for Energetic Intermediates

| Intermediate | Primary Hazard | Batch Handling | Flow Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organolithium | Pyrophoric, moisture-sensitive | Slow addition, strict anhydrous conditions, cryogenics | On-demand use, small volumes, higher possible temperatures |

| Diazonium Salts | Explosive upon drying or heating | Slow diazotization, strict T < 5°C, no accumulation | On-demand generation and immediate consumption |

| Organic Azides | Shock-sensitive, toxic | Cautious addition, avoidance of isolation/concentration | In-situ generation and telescoping without isolation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of flow chemistry for reactive intermediates relies on a suite of specialized equipment and reagents that differ from traditional batch setups.

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Flow Chemistry with Reactive Intermediates

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Microreactor / Chip Reactor | Provides high surface-area-to-volume ratio for rapid heat transfer and mixing. | Safe handling of exothermic organolithium formations and diazotizations [36]. |

| Tubular/Coil Reactor | Offers near-plug flow behavior for precise control over reaction kinetics; used in photochemistry. | Uniform irradiation in photochemical reactions [5] [36]. |

| Packed-Bed Reactor | Contains immobilized catalysts or reagents for heterogeneous reactions. | Hydrogenations or enzymatic transformations with simplified catalyst recycling [36]. |

| Precision Pumps | Deliver consistent, pulse-free flow of reagents for stable process conditions. | Essential for all continuous flow processes to maintain precise stoichiometry [36]. |

| Back Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Maintains system pressure, preventing degassing and allowing solvents to be heated above their boiling points. | Accessing high-temperature process windows safely [36]. |

| In-line Analytics (e.g., FTIR) | Provides real-time reaction monitoring for process control and optimization. | Enables closed-loop optimization of reaction parameters [26]. |