Beyond Throughput: A Researcher's Guide to Performance Metrics for Autonomous Chemistry Platforms

Autonomous chemistry platforms are revolutionizing research and development by accelerating discovery and optimizing complex processes.

Beyond Throughput: A Researcher's Guide to Performance Metrics for Autonomous Chemistry Platforms

Abstract

Autonomous chemistry platforms are revolutionizing research and development by accelerating discovery and optimizing complex processes. However, effectively deploying these systems requires a deep understanding of their performance beyond simple metrics like throughput. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to evaluate autonomous chemistry platforms. We explore the foundational metrics—from degrees of autonomy to operational lifetime—detail the algorithms and hardware that drive real-world applications, address key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and provide a guide for the comparative validation of different systems. This guide aims to empower professionals to select, implement, and optimize autonomous platforms to maximize their impact in biomedical and clinical research.

Defining the Core: Essential Performance Metrics for Self-Driving Labs

The field of chemical and materials science research is undergoing a fundamental transformation through the adoption of self-driving labs (SDLs), which integrate automated experimental workflows with algorithm-driven experimental selection [1]. These autonomous systems can navigate complex and exponentially expanding reaction spaces with an efficiency unachievable through human-led manual experimentation, enabling researchers to explore larger and more complicated experimental systems [1]. Determining what digital and physical features are germane to a specific study represents a critical aspect of SDL design that must be approached quantitatively, as every experimental space possesses unique requirements and challenges that influence the design of the optimal physical platform and algorithm [1].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of autonomy levels in experimental platforms, from basic piecewise systems to fully closed-loop operations, with supporting experimental data and performance metrics specifically framed within autonomous chemistry platform research. We objectively compare system performance across different autonomy levels and provide detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in recent literature, offering drug development professionals and researchers a framework for selecting appropriate autonomous strategies for their specific experimental challenges.

Defining the Spectrum of Autonomy

The degree of autonomy in experimental systems can be classified into distinct levels based on the extent of human intervention required [1]. This classification provides a crucial framework for comparing platforms across different studies, as metrics such as optimization rate are not necessarily indicative of an SDL's capabilities across different experimental spaces [1].

Hierarchical Levels of Autonomous Operation

Piecewise Systems (Algorithm-Guided): Characterized by complete separation between platform and algorithm, where human scientists must collect and transfer experimental data to the experimental selection algorithm, then transfer the algorithm-selected conditions back to the physical platform for testing [1]. These systems are particularly useful for informatics-based studies, high-cost experiments, and systems with low operational lifetimes, as human scientists can manually filter erroneous conditions and correct system issues as they arise [1].

Semi-Closed-Loop Systems: Require human intervention for some process loop steps while maintaining direct communication between the physical platform and experiment-selection algorithm [1]. Typically, researchers must either collect measurements after the experiment or reset aspects of the experimental system before continuing studies [1]. This approach is most applicable to batch or parallel processing, studies requiring detailed offline measurement techniques, and high-complexity systems that cannot conduct experiments continuously in series [1].

Closed-Loop Systems: Operate without human intervention to carry out experiments, with the entirety of experimental conduction, system resetting, data collection and analysis, and experiment-selection performed autonomously [1]. These challenging-to-create systems offer extremely high data generation rates and enable otherwise inaccessible data-greedy algorithms such as reinforcement learning and Bayesian optimization [1].

Self-Motivated Experimental Systems: Represent the highest autonomy level, where systems define and pursue novel scientific objectives without user direction [1]. These platforms merge closed-loop capabilities with autonomous identification of novel synthetic goals, completely replacing human-guided scientific discovery [1]. No platform has yet achieved this autonomy level [1].

Performance Metrics for Autonomous Systems

Quantifying SDL performance requires multiple complementary metrics that collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of capabilities across different experimental contexts [1].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Self-Driving Labs

| Metric Category | Definition | Measurement Approach | Significance in Platform Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of Autonomy | Level of human intervention required for operation | Classification into piecewise, semi-closed, closed-loop, or self-motivated systems | Determines labor requirements and suitability for different experiment types |

| Operational Lifetime | Duration a system can operate continuously | Demonstrated unassisted/assisted lifetime and theoretical unassisted/assisted lifetime | Indicates scalability and suitability for extended experimental campaigns |

| Throughput | Rate of experimental data generation | Theoretical maximum and demonstrated sampling rates under actual experimental conditions | Identifies data generation bottlenecks and capacity for dense data spaces |

| Experimental Precision | Reproducibility of experimental results | Standard deviation of unbiased replicates of single conditions | Impacts algorithm performance and data quality for reliable conclusions |

| Material Usage | Consumption of reagents and materials | Total quantity of materials, high-value materials, and environmentally hazardous substances used | Affects safety, cost, and environmental impact of experimental campaigns |

Complementary Performance Indicators

Beyond the core metrics outlined in Table 1, several additional factors critically influence autonomous system performance:

Orthogonal Analytics: Combining multiple characterization techniques is essential to capture the diversity inherent in modern organic chemistry and to mitigate uncertainty associated with relying solely on unidimensional measurements [2]. For example, one modular autonomous platform combines ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) and benchtop NMR spectroscopy to achieve a characterization standard comparable to manual experimentation [2].

Algorithmic Decision-Making: The efficacy of autonomous experiments hinges on both the quality and diversity of analytical data inputs and their subsequent autonomous interpretation [2]. Unlike catalyst optimization focusing on a single figure of merit, exploratory synthesis rarely involves measuring and maximizing a single parameter, presenting more open-ended problems from an automation perspective [2].

Many-Objective Optimization: Advanced applications like polymer nanoparticle synthesis require navigation of complex parameter spaces with multiple competing objectives, including monomer conversion, molecular weight distribution, particle size, and polydispersity index [3]. This increased problem complexity requires careful algorithmic consideration and evaluation of multiple machine learning approaches [3].

Comparative Analysis of Autonomous Platforms

Recent implementations across chemistry domains demonstrate how different autonomy levels address specific research requirements, with varying performance outcomes.

Table 2: Comparison of Recent Autonomous Platform Implementations

| Platform Type | Autonomy Level | Key Components | Experimental Throughput | Application Domain | Key Performance Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Robot Platform [2] | Closed-loop | Mobile robots, automated synthesis platform, UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR | Not explicitly quantified | Structural diversification, supramolecular host-guest chemistry, photochemical synthesis | Enabled autonomous identification of supramolecular assemblies; shared existing lab equipment with humans |

| Polymer Nanoparticle SDL [3] | Closed-loop | Tubular flow reactor, at-line GPC, inline NMR, at-line DLS | 67 reactions with full analyses in 4 days | Polymer nanoparticle synthesis via PISA | Unprecedented many-objective optimization (monomer conversion, molar mass, particle size, PDI) |

| Microfluidic Rapid Spectral System [1] | Not specified | Microdroplet reactor, spectral sampling | Demonstrated: 100 samples/hour; Theoretical: 1,200 measurements/hour | Colloidal atomic layer deposition reactions | Operational lifetime: demonstrated unassisted = 2 days, demonstrated assisted = 1 month |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Modular Robotic Workflow for Exploratory Synthesis

A recently published modular autonomous platform for general exploratory synthetic chemistry exemplifies closed-loop operation through a specific experimental protocol [2]:

- Synthesis Module: Utilizes a Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer for automated chemical synthesis [2].

- Sample Handling: On completion of synthesis, the ISynth synthesizer takes aliquots of each reaction mixture and reformats them separately for MS and NMR analysis [2].

- Mobile Transportation: Mobile robots handle samples and transport them to appropriate instruments (UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR) [2].

- Data Acquisition: Customizable Python scripts autonomously acquire data after sample delivery, with results saved in a central database [2].

- Decision-Making: A heuristic decision-maker processes orthogonal NMR and UPLC-MS data, applying binary pass/fail grading based on experiment-specific criteria determined by domain experts [2].

- Iteration: The decision-maker instructs the ISynth platform which experiments to perform next, completing the autonomous synthesis-analysis-decision cycle [2].

This workflow successfully demonstrated structural diversification chemistry and autonomous identification of supramolecular host-guest assemblies, with reactions required to pass both orthogonal analyses to proceed to the next step [2].

Many-Objective Optimization for Polymer Nanoparticles

A self-driving laboratory platform for many-objective optimization of polymer nanoparticle synthesis implements the following experimental protocol [3]:

- Initialization: Inputs and their limits are established, with initialization experiments selected within these limits using frameworks like Latin Hypercube Sampling or Design of Experiments [3].

- Experimental Execution: Selected experiments are performed using a tubular flow reactor system [3].

- Orthogonal Analysis: Reactions are characterized using inline benchtop NMR spectroscopy (monomer conversion), at-line gel permeation chromatography (molecular weight information), and at-line dynamic light scattering (particle size information) [3].

- Algorithmic Processing: Input variable-objective pairs are provided to cloud-based machine learning algorithms (TSEMO, RBFNN/RVEA, EA-MOPSO) which generate new experimental conditions [3].

- Closed-Loop Iteration: Steps 2-4 repeat autonomously until criteria are fulfilled or user intervention halts the process [3].

This approach accounted for an unprecedented number of objectives for closed-loop optimization of a synthetic polymerisation and enabled algorithm operation from different geographical locations to the reactor platform [3].

Visualization of Autonomous Workflows

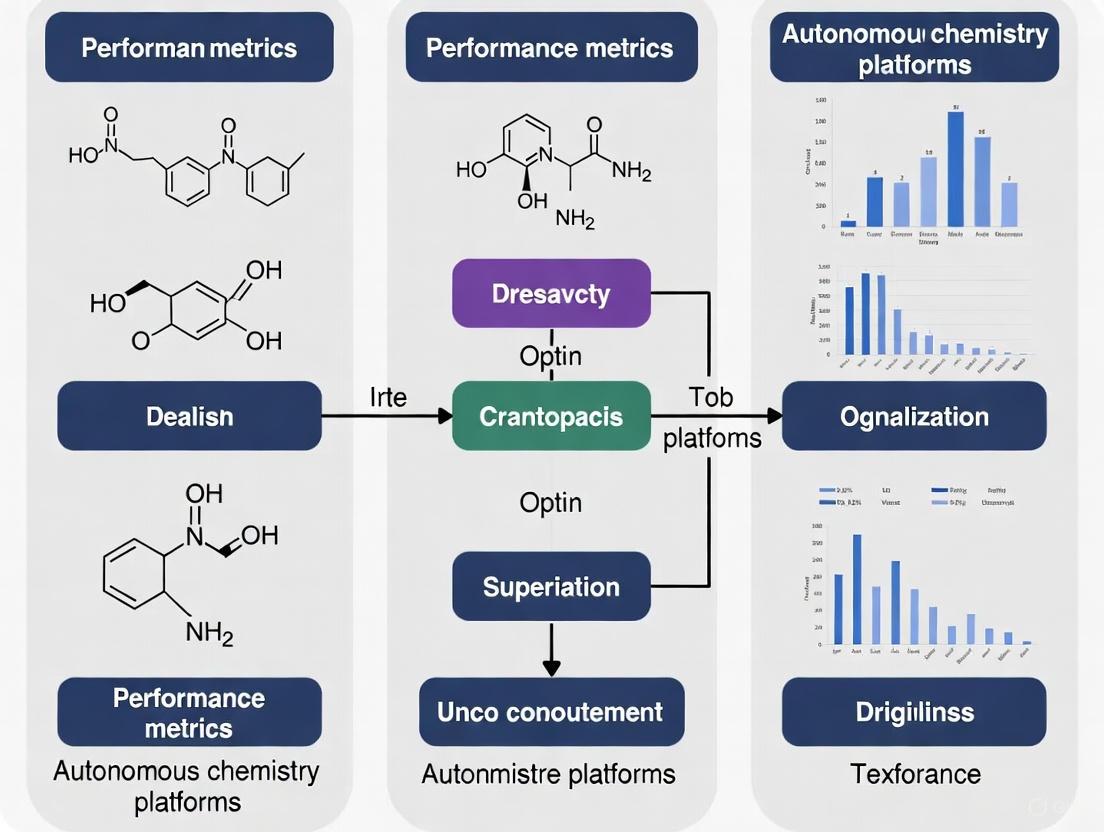

Figure 1: Spectrum of Experimental Autonomy Levels. This diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between different autonomy levels in self-driving laboratories, from basic piecewise systems requiring complete human mediation between platform and algorithm to fully closed-loop systems operating without human intervention. The highest level of self-motivated systems represents future capability where platforms autonomously define scientific objectives.

Figure 2: Closed-Loop Autonomous Experimentation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of closed-loop autonomous experimentation, highlighting the integration of orthogonal analysis techniques and algorithmic decision-making. The workflow continues until optimization criteria are met, with all experimental data stored in a central database for model training and analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Platform Components

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function in Autonomous Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Platforms | Chemspeed ISynth synthesizer [2], Tubular flow reactors [3] | Automated execution of chemical reactions with precise control over parameters |

| Analytical Instruments | Benchtop NMR spectroscopy [2] [3], UPLC-MS [2], GPC [3], DLS [3] | Provide orthogonal characterization data for comprehensive reaction assessment |

| Mobile Robotics | Free-roaming mobile robots with multipurpose grippers [2] | Enable modular laboratory design through sample transport between instruments |

| Algorithmic Frameworks | Thompson sampling efficient multi-objective optimization (TSEMO) [3], Radial basis function neural network/reference vector evolutionary algorithm (RBFNN/RVEA) [3] | Drive experimental selection through machine learning and optimization approaches |

| Cloud Computing Infrastructure | Cloud-based machine learning frameworks [3] | Enable remote algorithm operation and collaboration across geographical locations |

| Specialized Reactors | Microfluidic reactors [1], Microdroplet reactors [1] | Facilitate high-throughput experimentation with minimal material usage |

The spectrum of autonomy in experimental systems—from piecewise to closed-loop operation—offers researchers a range of options tailored to specific experimental requirements, with each level presenting distinct advantages for different research scenarios. As evidenced by recent implementations across chemical synthesis and materials science, the selection of appropriate autonomy level depends critically on factors including experimental complexity, characterization requirements, available resources, and research objectives. The continuing evolution of autonomous platforms, particularly through integration of orthogonal analytics, advanced decision-making algorithms, and modular robotic components, promises to further accelerate research discovery across chemical and materials science domains while providing the comprehensive data generation essential for navigating complex experimental parameter spaces.

Within the rapidly evolving field of autonomous chemistry platforms, such as self-driving labs (SDLs), the accurate quantification of a system's operational lifetime is paramount for assessing its practicality, scalability, and economic viability [1] [4]. Operational lifetime moves beyond simple durability, serving as a critical performance metric that directly impacts data generation capacity, labor costs, and the platform's suitability for long-duration exploration of complex chemical spaces [1]. This comparison guide objectively dissects the fundamental distinction between theoretical and demonstrated operational lifetime, a framework essential for evaluating and comparing autonomous platforms within a broader thesis on performance metrics for chemical research acceleration [4].

Core Concepts and Definitions

For autonomous platforms, "operational lifetime" is specifically defined as the duration a system can function and conduct experiments without mandatory external intervention [1]. This concept is deliberately bifurcated into two complementary metrics:

- Theoretical Lifetime: Represents the maximum potential operational duration under idealized conditions, assuming no failures of hardware or software, and an uninterrupted supply of all necessary resources (e.g., materials, energy, computational power). It defines the absolute upper boundary of a platform's capability [1].

- Demonstrated Lifetime: Refers to the empirically verified operational duration achieved during an actual experimental campaign or study. It accounts for real-world constraints such as unforeseen technical failures, material degradation (e.g., precursor decomposition, reactor fouling), and necessary maintenance pauses [1].

A further critical subclassification is the distinction between assisted and unassisted lifetimes, which quantifies the level of human intervention required. For instance, a platform may have a demonstrated unassisted lifetime of two days (e.g., limited by precursor stability), but with daily manual replenishment of that precursor, its demonstrated assisted lifetime could extend to one month [1].

Performance Comparison: Theoretical vs. Demonstrated in Practice

The following table synthesizes quantitative data and comparisons from research on autonomous systems and related fields, highlighting the critical gap between theoretical potential and demonstrated reality.

Table 1: Comparison of Theoretical and Demonstrated Operational Performance Across Systems

| System / Study Focus | Theoretical Lifetime / Performance | Demonstrated Lifetime / Performance | Key Limiting Factors (Affecting Demonstrated Lifetime) | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Driving Lab (SDL) - Microfluidic Platform | Functionally indefinite (assuming continuous resource supply) | Unassisted: ~2 daysAssisted: Up to 1 month | Degradation of a specific precursor every two days; reactor fouling over longer periods [1]. | Chemistry/Materials Science SDL [1] |

| Perovskite Solar Cell (PSC) - Triple-Cation (Cs/MA/FA) | Estimated via reliability models under accelerated aging. | Mean Time to Failure (MTTF): >180 days in ambient conditions. | Environmental stress (humidity, heat); chemical phase instability of perovskite layer [5]. | Energy Device Stability Testing [5] |

| Perovskite Solar Cell (PSC) - Single MA Cation | Not explicitly stated, but implied lower than triple-cation. | MTTF: Significantly less than 180 days (∼8x less stable than triple-cation). | High susceptibility to moisture and thermal degradation [5]. | Comparative Control Study [5] |

| SDL - Steady-State Flow Experiment | Limited by reaction time per experiment (e.g., ~1 hour/experiment idle time). | Data throughput defined by sequential experiment completion. | Mandatory idle time waiting for individual reactions to reach completion before characterization [6]. | Conventional autonomous materials discovery [6] |

| SDL - Dynamic Flow Experiment | Continuous, near-theoretical data acquisition limited only by sensor speed. | ≥10x more data than steady-state mode in same period; identifies optimal candidates on first post-training try [6]. | Engineering challenge of real-time, in-situ characterization and continuous flow parameter variation [6]. | Advanced "streaming-data" SDL for inorganic materials [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Lifetime Assessment

The quantification of operational lifetime, particularly the demonstrated component, relies on rigorous, domain-appropriate experimental protocols.

Protocol 1: Mean Time to Failure (MTTF) Analysis for Energy Materials This method, adapted from reliability engineering, is used to project the operational lifetime of devices like solar cells [5].

- Sample Preparation & Baseline Testing: Fabricate devices (e.g., triple-cation and single-cation PSCs) under controlled conditions. Measure initial performance metrics (e.g., Power Conversion Efficiency - PCE) [5].

- Accelerated Aging Stress Tests: Subject cohorts of devices to constant, high-stress environmental conditions. Common stressors include:

- Performance Monitoring: At regular intervals, remove samples and measure key performance parameters (e.g., PCE, fill factor) to track degradation.

- Failure Definition & Data Fitting: Define a failure criterion (e.g., PCE dropping below 80% of initial value). Record time-to-failure for each sample. Use statistical models (e.g., Weibull analysis) to fit the failure time data and calculate the Mean Time to Failure (MTTF), which serves as the demonstrated lifetime under the test conditions [5].

- Theoretical Lifetime Projection: Use the degradation kinetics observed under accelerated stress to model and extrapolate a theoretical lifetime under standard operating conditions.

Protocol 2: Demonstrated Lifetime for a Continuous-Flow Self-Driving Lab This protocol assesses the practical operational limits of an autonomous chemistry platform [1].

- System Calibration & Initialization: Calibrate all robotic components, sensors, and analytical instruments. Load the platform with initial stocks of all necessary chemical precursors, solvents, and consumables.

- Unassisted Operational Test: Initiate a closed-loop, autonomous experimental campaign. The system must run without any human intervention (no refilling, cleaning, or hardware adjustments). The demonstrated unassisted lifetime is the continuous duration until the system halts due to a depleted resource (e.g., a specific precursor), a clog, a sensor fault, or a software error [1].

- Assisted Operational Test: Initiate a new campaign where a minimal, predefined human intervention is allowed at regular intervals (e.g., replenishing a volatile solvent every 24 hours). The demonstrated assisted lifetime is the total duration of successful operation until a failure occurs that is not addressed by the scheduled intervention [1].

- Theoretical Lifetime Calculation: Calculate the theoretical lifetime based on the total volume of all loaded materials divided by the minimum consumption rate per experiment, assuming zero hardware failures and perfect software execution.

Visualization of Performance Metrics and Assessment Workflow

Figure 1: SDL Performance Metrics & Lifetime Framework

Figure 2: Operational Lifetime Assessment Workflow

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials for SDL Lifetime Studies

| Item / Category | Function in Lifetime Quantification | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Reactor Systems | Core physical platform for continuous, automated synthesis. Enables precise control over reaction parameters and material usage, directly impacting theoretical lifetime via reagent volumes [1] [6]. | Continuous-flow chips with inline mixing and heating zones. |

| Stable Precursor Libraries | Chemical reagents with verified long-term stability under operational conditions. Critical for extending demonstrated unassisted lifetime by preventing degradation-induced stoppages [1]. | Stabilized organometallic solutions for nanomaterials synthesis; anhydrous, oxygen-free solvents. |

| In-situ/Inline Characterization | Sensors (spectrophotometers, mass specs) integrated into the flow path. Enable real-time analysis for dynamic flow experiments, maximizing data throughput and informing algorithm decisions without stopping the system [6]. | Fiber-optic UV-Vis probes; miniaturized mass spectrometers. |

| Automated Material Handling | Robotic liquid handlers, solid dispensers, and sample changers. Manage replenishment of resources in assisted lifetime modes and enable continuous operation [1] [7]. | XYZ Cartesian robots with pipetting arms; vibratory powder feeders. |

| Reliability Testing Chambers | Environmental chambers for accelerated aging studies (e.g., of resulting materials like solar cells). Provide controlled stress conditions (temp, humidity) to empirically determine device-level demonstrated lifetime [5]. | Temperature/Humidity chambers with electrical monitoring feeds. |

| Algorithm & Scheduling Software | The "brain" of the SDL. Machine learning models (Bayesian Optimization, RL) select experiments. Scheduling algorithms must account for resource levels and maintenance needs to optimize operational longevity [1] [7]. | Custom Python workflows integrating libraries like Phoenix, BoTorch. |

| Benchmarking Datasets & Models | Large-scale computational datasets (e.g., OMol25) and pre-trained AI models. Provide prior knowledge to reduce the number of physical experiments needed, indirectly conserving materials and extending effective platform utility [8]. | Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset; universal Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) [8]. |

Within the broader research landscape of performance metrics for autonomous chemistry platforms, a critical evaluation lies in quantifying throughput—the rate at which experiments are performed and data is generated. This guide objectively compares the theoretical maximum throughput claimed by various platforms and technologies against their practically demonstrated performance in peer-reviewed literature, providing a framework for researchers to assess real-world capabilities.

Theoretical Frameworks and Practical Realities of Throughput

The concept of throughput in automated chemistry is multidimensional, encompassing the speed of synthesis, analysis, and the iterative design-make-test-learn (DMTL) cycle [9] [2]. Theoretical maximum throughput is often derived from engineering specifications: the number of parallel reactors, the speed of liquid handling robots, or the cycle time of an analytical instrument. For instance, ultra-high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms claim the ability to run 1536 reactions simultaneously [10]. In flow chemistry, theoretical throughput is calculated from reactor volume and minimum residence time, enabling claims of intensified, continuous kilogram-per-day production [11].

However, practically demonstrated throughput is invariably lower and is the true metric of platform efficacy. This practical ceiling is imposed by several universal bottlenecks:

- Sample Preparation & Logistics: Time required for reagent dispensing, plate sealing, and transport between modules [2].

- Analysis Time: Even with rapid analytics like UPLC-MS, queueing and acquisition times for hundreds of samples significantly limit cycle time [2].

- Decision-Making Overhead: The computational or heuristic processing time required to analyze results and plan the next experiment [12] [2].

- System Reliability: Downtime from clogging (in flow systems), robotic errors, or instrument calibration [11] [10].

The following table synthesizes data from key platforms and approaches, contrasting their theoretical potential with documented real-world performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Theoretical vs. Practical Throughput in Autonomous Chemistry Platforms

| Platform / Technology Type | Theoretical Maximum Throughput (Claimed or Calculated) | Practically Demonstrated Throughput (Documented) | Key Limiting Factors (from experiments) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate-Based Ultra-HTE [10] | 1536 reactions per plate; simultaneous. | ~1000-1500 reactions per day, including setup & analysis. | Spatial bias in wells, evaporation, analysis queueing, liquid handling precision. |

| Integrated Flow Chemistry for Scale-up [11] | Process intensification: e.g., ~6.6 kg/day for a photoredox reaction based on reactor kinetics. | 100g scale validated before successful kilo-scale run (97% conversion). | Pre-flow optimization required (DoE, stability studies), risk of clogging with heterogeneous mixtures. |

| Mobile Robot-Enabled Modular Lab [2] | Parallel synthesis in a Chemspeed ISynth (e.g., 24-96 reactions/batch) with on-demand NMR/UPLC-MS. | A full DMTL cycle for a batch of 6 reactions required several hours, dominated by analysis/decision time. | Sample transport by robots, sequential use of shared analytical instruments, heuristic decision-making time. |

| AI-Driven Nanomaterial Optimization Platform [12] | A* algorithm for rapid parameter space search; commercial PAL system for automated synthesis/UV-vis. | 735 experiments to optimize Au nanorods across a multi-target LSPR range (600-900 nm). | Iteration time per cycle (synthesis + characterization), algorithm convergence speed, need for targeted TEM validation. |

| Autonomous Photoreaction Screening [11] | 384-well microtiter plate photoreactor for simultaneous screening. | Initial screen of catalysts/bases, followed by iterative optimization in 96-well plates for 110 compounds. | Light penetration uniformity, heating effects, need for follow-up scale-up and purification (LC-MS). |

Experimental Protocols for Throughput Validation

To critically evaluate throughput claims, standardized assessment methodologies are essential. Below are detailed protocols derived from key studies that practically measure platform performance.

Protocol 1: End-to-End DMTL Cycle Time Measurement (Adapted from Mobile Robotic Platform [2])

- Objective: Measure the total hands-off time required to complete one full Design-Make-Test-Learn cycle for a batch of parallel reactions.

- Methodology:

- Design: Pre-load a set of reagent combinations for a divergent synthesis (e.g., amines + isothiocyanates).

- Make: Initiate parallel synthesis in an automated synthesizer (e.g., Chemspeed ISynth).

- Test: Upon completion, the platform automatically prepares aliquots. Mobile robots transport samples to UPLC-MS and benchtop NMR. Analysis runs sequentially.

- Learn: A heuristic decision-maker processes orthogonal NMR/MS data. Reactions passing both analyses are flagged for scale-up.

- Throughput Metric: Total clock time from synthesis initiation to the generation of a validated "hit" list for the next round. This metric reveals bottlenecks in inter-module logistics and analysis queueing.

Protocol 2: Flow Chemistry Scale-up Throughput Verification (Adapted from Photoredox Fluorodecarboxylation [11])

- Objective: Document the practical pathway and time from microfluidic screening to gram/kilogram-scale production.

- Methodology:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Perform initial condition screening in a 96-well plate photoreactor to identify hits (photocatalyst, base, reagent).

- Batch Validation & DoE: Validate hits in batch reactors, then use Design of Experiments (DoE) for optimization.

- Flow Translation & Stability: Conduct stability studies of reaction components to define feed solutions. Transfer to a lab-scale flow photoreactor (e.g., Vapourtec UV150) for initial small-scale (2g) validation.

- Gradual Scale-up: Systematically increase pump rates and reactor volume while monitoring conversion (e.g., via inline PAT). Record the maximum sustained output (g/h or kg/day) at >95% conversion.

- Throughput Metric: The final, reliably demonstrated mass output per unit time (e.g., 6.56 kg/day), which is often less than the theoretical maximum calculated from initial microfluidic kinetics.

Protocol 3: Algorithmic Optimization Efficiency Test (Adapted from A* Algorithm for Nanomaterial Synthesis [12])

- Objective: Compare the number of experiments required by different AI/search algorithms to reach a defined material property target.

- Methodology:

- Target Definition: Set a specific, measurable target (e.g., Au nanorod LSPR peak at 850 nm ± 10 nm with minimum FWHM).

- Parameter Space Definition: Discretize key synthesis variables (e.g., concentration of ascorbic acid, AgNO₃, seed volume).

- Closed-Loop Run: Employ the autonomous platform (e.g., PAL DHR system) with integrated UV-vis. Initiate searches using different algorithms (A*, Bayesian Optimization, Optuna) from the same starting point.

- Termination: Run until one algorithm achieves the target. If all achieve it, compare the number of experimental iterations required.

- Throughput Metric: "Experiments-to-Solution" — a crucial metric for AI-driven platforms where the speed of learning, not just physical execution, defines throughput.

Visualization of Workflows and Decision Metrics

The core operational and conceptual frameworks discussed can be visualized through the following diagrams.

Autonomous Chemistry Platform Core Workflow

Throughput Metric Evaluation and Decision Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of any throughput metric depends on the consistent performance of core reagents and materials. Below is a table of essential solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Autonomous Chemistry Workflows

| Item / Reagent | Function in Throughput Experiments | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Photoredox Catalyst (e.g., Flavin-based) [11] | Enables photochemical transformations in HTE and flow; homogeneity is critical to prevent clogging in flow scale-up. | Used in the fluorodecarboxylation reaction optimized from plate to kg-scale flow [11]. |

| Gold Seed Solution (e.g., CTAB-capped Au nanospheres) [12] | The foundational material for the seeded growth of anisotropic Au nanorods; consistency is vital for reproducible LSPR optimization. | Core reagent in the autonomous A* algorithm-driven optimization of Au NR morphology [12]. |

| Surfactant Solution (e.g., Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide - CTAB) [12] | Directs the morphology and stabilizes the colloid during nanomaterial synthesis; concentration is a key optimization parameter. | A primary variable discretized in the algorithmic search for Au NR synthesis parameters [12]. |

| Deuterated Solvent for NMR (e.g., DMSO-d⁶) [2] | Provides the lock signal and solvent for automated benchtop NMR analysis in orthogonal characterization workflows. | Essential for the mobile robot-transported analysis in the modular autonomous platform [2]. |

| UPLC-MS Grade Solvents & Columns [2] | Ensure high-resolution, reproducible separation and ionization for rapid, reliable analysis within the DMTL cycle. | Critical for the UPLC-MS component of the Test phase in autonomous workflows [2]. |

A rigorous assessment of autonomous chemistry platforms must move beyond theoretical specifications. As evidenced by comparative data, practical throughput is governed by the slowest step in an integrated workflow—often analysis or decision-making—and by the reproducibility of chemical reactions themselves [12] [10] [2]. The most informative performance metric is therefore a composite statement: the Theoretical Maximum (Practically Demonstrated) throughput, such as "1536-well capability (~1000 expts/day)" or "Flow reactor potential of 6.6 kg/day (validated at 1.23 kg/run)." For AI-driven platforms, the "Experiments-to-Solution" metric is equally critical [12]. Researchers and developers should adopt the standardized validation protocols outlined herein to generate comparable, realistic data, driving the field from speculative capacity to demonstrated, reliable performance.

The Critical Role of Experimental Precision and its Impact on AI Algorithms

In the rapidly evolving field of autonomous chemistry, the synergy between experimental precision and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms has emerged as a critical determinant of success. Self-driving labs (SDLs) represent a transformative paradigm shift, integrating automated robotic platforms with AI to execute closed-loop "design-make-test-analyze" cycles that accelerate scientific discovery [7]. These systems promise to navigate the vast complexity of chemical spaces with an efficiency unattainable through traditional manual experimentation. However, the performance of the AI algorithms driving these platforms—including Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms, and reinforcement learning—is fundamentally constrained by the quality and precision of the experimental data they receive [1]. Experimental precision, defined as the unavoidable spread of data points around a "ground truth" mean value quantified through standard deviation of unbiased replicates, therefore serves as the foundational element upon which reliable autonomous discovery is built [1]. Without sufficient precision, even the most sophisticated algorithms struggle to distinguish meaningful signals from noise, potentially leading to false optima, inefficient exploration, and ultimately, unreliable scientific conclusions. This article examines the intricate relationship between experimental precision and AI algorithm performance within autonomous chemistry platforms, providing researchers with quantitative frameworks and methodological guidelines to optimize their experimental systems.

Quantifying Precision: Metrics and Methodologies

Defining Experimental Precision in Autonomous Systems

In the context of autonomous laboratories, experimental precision represents the reproducibility and reliability of measurements obtained from automated platforms. The standard methodology for quantifying this essential metric involves conducting unbiased replicates of a single experimental condition set and calculating the standard deviation across these measurements [1]. To prevent systematic bias and ensure accurate precision characterization, researchers should employ specific sampling strategies, such as alternating the test condition with random condition sets before each replicate, which better simulates the actual conditions encountered during optimization processes [1]. This approach helps account for potential temporal drifts in instrument response or environmental factors that might artificially inflate precision estimates if replicates were performed sequentially.

The critical importance of precision stems from its direct impact on an AI algorithm's ability to discern meaningful patterns within experimental data. As noted in research on performance metrics for self-driving labs, "high data generation throughput cannot compensate for the effects of imprecise experiment conduction and sampling" [1]. This establishes precision not as a secondary concern but as a primary constraint on overall system performance, one that must be carefully characterized and optimized before deploying resource-intensive autonomous experimentation campaigns.

The Precision-Throughput Tradeoff in Experimental Design

A fundamental challenge in designing autonomous experimentation platforms lies in balancing the competing demands of precision and throughput. While high-throughput systems can generate vast quantities of data rapidly, they often do so at the expense of measurement precision, particularly when utilizing rapid spectral sampling or parallelized experimentation approaches [1]. Research indicates that this tradeoff is not merely operational but fundamentally impacts algorithmic performance, as "sampling precision has a significant impact on the rate at which a black-box optimization algorithm can navigate a parameter space" [1].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics that must be considered alongside precision when evaluating autonomous experimentation platforms:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Autonomous Experimentation Platforms

| Metric | Description | Impact on AI Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Precision | Standard deviation of unbiased replicates of a single condition [1] | Determines signal-to-noise ratio; affects convergence rate and optimization efficiency [1] |

| Throughput | Number of experiments performed per unit time (theoretical and demonstrated) [1] | Limits exploration density; affects ability to navigate high-dimensional spaces [1] |

| Operational Lifetime | Duration of continuous operation (assisted and unassisted) [1] | Determines scale of possible experimentation campaigns; affects parameter space coverage [1] |

| Degree of Autonomy | Level of human intervention required (piecewise, semi-closed, closed-loop) [1] | Impacts labor requirements and experimental consistency; affects data quality [1] |

| Material Usage | Quantity of materials consumed per experiment [1] | Constrains exploration of expensive or hazardous materials; affects experimental scope [1] |

Impact of Precision on AI Algorithm Performance

Algorithmic Sensitivity to Experimental Noise

The performance of optimization algorithms commonly deployed in autonomous laboratories exhibits varying degrees of sensitivity to experimental imprecision. Bayesian optimization (BO), a dominant approach in SDLs due to its sample efficiency, relies on accurate surrogate models to approximate the underlying response surface and strategically select informative subsequent experiments [7]. When experimental precision is low, the noise overwhelms the signal, causing the algorithm to struggle with distinguishing true optima from stochastic fluctuations. This directly impacts the convergence rate and may lead to premature convergence on false optima [1]. Similarly, genetic algorithms (GAs), which have been successfully applied to optimize crystallinity and phase purity in metal-organic frameworks, depend on accurate fitness evaluations to guide the selection and crossover operations that drive evolutionary improvement [7]. In high-noise environments, selection pressure diminishes, and the search degenerates toward random exploration.

The relationship between precision and algorithmic performance has been systematically studied through surrogate benchmarking, where algorithms are tested on standardized mathematical functions with controlled noise levels simulating experimental imprecision [1]. These studies consistently demonstrate that "high data generation throughput cannot compensate for the effects of imprecise experiment conduction and sampling" [1]. This finding underscores the critical nature of precision as a foundational requirement rather than an optional optimization. The following diagram illustrates how experimental precision impacts the core learning loop of an autonomous laboratory:

Diagram 1: Precision Impact on AI Learning Loop

Quantitative Analysis of Precision Effects

The impact of experimental precision on optimization efficiency can be quantified through specific performance metrics that are critical for comparing autonomous platforms. Studies utilizing surrogate benchmarking have demonstrated that even modest levels of experimental noise can significantly degrade optimization performance, sometimes requiring up to three times more experimental iterations to achieve the same target objective value compared to low-noise conditions [1]. This performance degradation manifests in several key metrics: optimization rate (improvement in objective function per unit time or experiment), sample efficiency (number of experiments required to reach target performance), and convergence reliability (percentage of optimization runs that successfully identify global or satisfactory local optima).

The relationship between precision and algorithmic performance is particularly crucial in chemical and materials science applications where experimental noise arises from multiple sources, including reagent purity, environmental fluctuations, instrumental measurement error, and process control variability. For example, in a closed-loop optimization of colloidal atomic layer deposition reactions, precision in droplet volume, temperature control, and timing directly influenced the Bayesian optimization algorithm's ability to navigate the multi-dimensional parameter space efficiently [1]. The following table compares the performance of different AI algorithms under varying precision conditions based on data from autonomous chemistry studies:

Table 2: AI Algorithm Performance Under Varying Precision Conditions

| AI Algorithm | Application Example | High Precision Conditions | Low Precision Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization | Photocatalyst selection [7], inorganic powder synthesis [7] | Rapid convergence (≤20 iterations); reliable global optimum identification [1] [7] | Slow convergence (≥50 iterations); premature convergence on local optima [1] |

| Genetic Algorithms | Metal-organic framework crystallinity optimization [7] | Efficient exploration of high-dimensional spaces; clear fitness gradient [7] | Loss of selection pressure; random search characteristics [1] |

| Random Forest | Predictive modeling for materials synthesis [7] | High prediction accuracy (R² > 0.9); reliable experimental exclusion [7] | Poor generalization; high variance in predictions [1] |

| Bayesian Neural Networks (Phoenics) | Thin-film materials optimization [7] | Faster convergence than Gaussian Processes [7] | Increased uncertainty; conservative exploration [1] |

Methodologies for Precision Enhancement

Experimental Design for Precision Optimization

Enhancing experimental precision begins with deliberate design choices that minimize variability at its source. Research in autonomous laboratories has identified several foundational strategies for precision optimization. First, platform designers should implement automated calibration protocols that run at regular intervals, using standardized reference materials to account for instrumental drift over time. Second, environmental control systems that maintain stable temperature, humidity, and atmospheric conditions eliminate significant sources of experimental variance, particularly in sensitive chemical and materials synthesis processes. Third, redundant measurement strategies, such as multiple sampling from the same reaction vessel or parallel measurement using complementary techniques, can help quantify and reduce measurement uncertainty.

A critical methodology for precision characterization involves conducting "variability mapping" experiments early in the autonomous platform development process. This entails running extensive replicate experiments across the anticipated operational range of the platform to establish precision baselines under different conditions [1]. The resulting precision maps inform both the algorithm selection and the confidence intervals that should be applied to experimental measurements during optimization. As noted in performance metrics research, "characterization of the precision component is critical for evaluating the efficacy of an experimental system" [1]. This systematic approach to precision characterization represents a foundational step in developing reliable autonomous discovery platforms.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The pursuit of experimental precision in autonomous chemistry platforms requires carefully selected reagents and materials that ensure reproducibility and minimize introduced variability. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for high-precision autonomous experimentation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Precision Autonomous Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Autonomous Platform | Precision Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and validation of analytical instruments [1] | Traceable purity standards; certified uncertainty measurements |

| High-Purity Solvents | Reaction medium for chemical synthesis [7] | Low water content; certified impurity profiles; batch-to-batch consistency |

| Characterized Catalyst Libraries | Screening and optimization of catalytic reactions [7] | Well-defined composition; controlled particle size distribution |

| Stable Precursor Solutions | Reproducible feedstock for materials synthesis [1] | Degradation resistance; concentration stability over operational lifetime |

| Internal Standard Solutions | Quantification and normalization of analytical signals [1] | Chemical inertness; distinct detection signature; predictable response |

Case Studies: Precision-Driven Discoveries

Autonomous Platforms in China: A Paradigm of Precision

Recent advances in autonomous laboratories in China demonstrate the critical relationship between experimental precision and AI algorithm performance. These platforms have progressed from simple iterative-algorithm-driven systems to comprehensive intelligent autonomous systems powered by large-scale models [7]. In one implementation, researchers developed a microdroplet reactor for colloidal atomic layer deposition reactions that achieved high precision through meticulous fluidic control and real-time monitoring [1]. This system demonstrated the importance of precision in achieving reliable autonomous operation, with the platform maintaining continuous operation for up to one month through careful precision management, including regular precursor replenishment to combat degradation-induced variability [1].

The integration of automated theoretical calculations, such as density functional theory (DFT), with experimental autonomous platforms represents another precision-enhancing strategy [7]. This "data fusion" approach provides valuable prior knowledge that guides experimental design and enhances adaptive learning capabilities [7]. By combining high-precision theoretical predictions with carefully controlled experimental validation, these systems create a virtuous cycle of improvement where each informs and refines the other. The resulting continuous model updating and refinement exemplifies how precision at both computational and experimental levels drives accelerated discovery in autonomous chemistry platforms.

Algorithmic Adaptations to Precision Constraints

Beyond improving experimental precision, researchers have developed algorithmic strategies that explicitly account for precision limitations. Bayesian optimization algorithms, for instance, can incorporate noise estimates directly into their acquisition functions, allowing them to balance the exploration-exploitation tradeoff while considering measurement uncertainty [1]. Similarly, genetic algorithms can be modified to maintain greater population diversity in high-noise environments, preventing premature convergence that might result from spurious fitness assessments [7]. These algorithmic adaptations represent a crucial frontier in autonomous research, enabling effective operation even when precision cannot be further improved due to fundamental experimental constraints.

The relationship between precision and algorithm selection is illustrated in the following diagram, which guides researchers in matching algorithmic strategies to experimental precision conditions:

Diagram 2: Algorithm Selection Based on Precision

Experimental precision stands not as a peripheral concern but as a central determinant of success in autonomous chemistry platforms. The relationship between precision and AI algorithm performance is quantifiable, significant, and non-negotiable for researchers seeking to deploy reliable autonomous discovery systems. As the field progresses toward increasingly distributed autonomous laboratory networks and more complex experimental challenges, the systematic characterization and optimization of precision will only grow in importance [7]. Future developments will likely focus on real-time precision monitoring and adaptive algorithmic responses, creating systems that can dynamically adjust their operation based on measured variability. Furthermore, as autonomous platforms tackle increasingly complex chemical spaces and multi-step syntheses, precision management across sequential operations will emerge as a critical research frontier. For researchers and drug development professionals, investing in precision characterization and optimization represents not merely technical refinement but a fundamental requirement for harnessing the full potential of AI-driven autonomous discovery.

In the rapidly evolving field of autonomous chemistry, self-driving laboratories (SDLs) represent a transformative integration of artificial intelligence, automated robotics, and advanced data analytics [7] [13]. These systems promise to accelerate materials discovery by autonomously executing iterative design-make-test-analyze (DMTA) cycles [14]. While much attention has focused on algorithmic performance and throughput capabilities, material usage emerges as an equally critical metric spanning cost, safety, and environmental dimensions [1].

Material consumption directly influences the operational viability and sustainability of SDL platforms. As noted in Nature Communications, "When working with the number of experiments necessary for algorithm-guided research and navigation of large, complex parameter spaces, the quantity of materials used in each trial becomes a consideration" [1]. This consideration extends beyond mere economics to encompass safer handling of hazardous substances and reduced environmental footprint through miniatureized workflows [1] [15]. The emergence of "frugal twins" – low-cost surrogates of high-cost research systems – further highlights the growing emphasis on accessibility and resource efficiency in autonomous experimentation [16].

This guide provides a comprehensive assessment of material usage across contemporary SDL platforms, comparing performance through standardized metrics, experimental data, and implementation frameworks to inform researcher selection and optimization strategies.

Performance Metrics Framework for Material Usage Assessment

Multidimensional Metrics Framework

Evaluating material usage in SDLs requires a structured approach encompassing quantitative and qualitative dimensions. As established in literature, three primary categories form the assessment framework [1]:

- Economic Impact: Total material costs, consumption of high-value reagents, and operational expenditures per experimental cycle.

- Safety Profile: Quantities of hazardous materials handled, exposure risk potential, and containment requirements.

- Environmental Footprint: Waste generation volume, resource consumption efficiency, and green chemistry principles adherence.

These metrics collectively determine the sustainability and practical implementation potential of autonomous platforms across academic, industrial, and resource-constrained settings [16] [17].

Material Flow in Autonomous Experimentation

The material consumption patterns in SDLs follow distinct operational paradigms, primarily dictated by the chosen hardware architecture. The diagram below illustrates the fundamental material flow through a closed-loop SDL system.

Material Flow in a Closed-Loop Self-Driving Laboratory

This flow architecture enables precise tracking of material utilization at each process stage, facilitating optimization opportunities at synthesis, characterization, and waste management nodes [1] [15].

Comparative Analysis of SDL Platforms and Material Efficiency

Platform-Specific Material Usage Profiles

SDL implementations vary significantly in their material consumption patterns based on architectural choices, reactor designs, and operational paradigms. The following table synthesizes quantitative and characteristic data from peer-reviewed implementations.

Table 1: Material Usage Comparison Across SDL Platforms

| Platform Type | Cost Range (USD) | Reaction Volume | Key Material Efficiency Features | Reported Waste Reduction | Safety Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Chemistry SDLs [6] [15] | $450 - $5,000 | Microscale (μL-mL) | Continuous operation, real-time analytics, minimal dead volume | ≥10x vs. batch systems [6] | Automated hazardous material handling, small inventory |

| Batch Chemistry SDLs [16] [2] | $300 - $30,000 | Macroscale (mL-L) | Parallel processing, reusable reaction vessels | Moderate (2-5x) vs. manual | Enclosed environments, reduced researcher exposure |

| Educational "Frugal Twins" [16] [17] | $50 - $1,000 | Variable | Open-source designs, low-cost components, modularity | High (educational focus) | Low-risk operation, minimal hazardous materials |

| Mobile Robot Platforms [2] | $5,000 - $30,000 | Macroscale (mL-L) | Shared equipment utilization, flexible workflows | Moderate (through reuse) | Robots handle hazardous operations |

Architectural Impact on Material Consumption

The fundamental architecture of SDL platforms dictates their intrinsic material efficiency characteristics. Two predominant paradigms—flow chemistry and batch systems—demonstrate markedly different consumption profiles.

Table 2: Architectural Comparison: Flow vs. Batch SDLs

| Parameter | Flow Chemistry SDLs | Batch Chemistry SDLs |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent Consumption | μL-mL per experiment [15] | mL-L per experiment [2] |

| Solvent Usage | Minimal (continuous recycling possible) | Significant (cleaning between runs) |

| Throughput vs. Material Use | High throughput with minimal material [6] | Throughput limited by material requirements |

| Reaction Optimization Efficiency | ~1 order of magnitude improvement in data/material [6] | Moderate improvement over manual |

| Characterization Material Needs | In-line analysis (minimal sampling) | Ex-situ sampling (significant material diversion) |

| Scalability Impact | Direct translation from discovery to production | Significant re-optimization often required |

Flow chemistry platforms exemplify material-efficient design through their foundational principles: "reaction miniaturization, enhanced heat and mass transfer, and compatibility with in-line characterization" [15]. The recent innovation of dynamic flow experiments has further intensified these advantages, enabling "at least an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency and reducing both time and chemical consumption compared to state-of-the-art self-driving fluidic laboratories" [6].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Methodologies for Material Usage Assessment

Standardized experimental protocols enable direct comparison of material efficiency across SDL platforms. The following methodologies represent best practices derived from recent literature.

Dynamic Flow Intensification Protocol

Objective: Quantify material efficiency gains through continuous flow experimentation [6]. Materials: Precursor solutions, solvent carriers, microfluidic reactor, in-line spectrophotometer. Procedure:

- Establish continuous variation of chemical mixtures through microfluidic system

- Implement real-time monitoring with spectral sampling at 0.5-second intervals

- Compare data points per unit material against steady-state flow experiments

- Measure total precursor consumption for equivalent parameter space exploration Validation: "Dynamic flow experiments yield at least an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency and reducing both time and chemical consumption" [6].

Low-Cost Electrochemical Platform Protocol

Objective: Assess open-source SDL components for accessible material-efficient experimentation [17]. Materials: Custom potentiostat, automated synthesis platform, coordination compound precursors. Procedure:

- Implement modular automation platform with online electrochemical analysis

- Execute campaign reacting metal ions with ligands to form coordination compounds

- Compare cost and material usage against commercial alternatives

- Quantify database generation efficiency (measurements per unit material) Outcome: Generation of "400 electrochemical measurements" with open-source hardware demonstrating comparable performance to commercial systems at reduced cost [17].

Case Study: Sustainable Metal-Organic Framework Synthesis

Objective: "Finding environmental-friendly chemical synthesis" by replacing nitrate salts with chloride alternatives in Zn-HKUST-1 metal-organic frameworks [18]. Experimental Workflow:

- LLM-based literature analysis to establish baseline synthesis conditions

- Robotic synthesis optimization with reduced environmental impact precursors

- Automated characterization and classification of crystalline products Material Efficiency Outcomes: Successful synthesis from ZnCl2 precursors demonstrating "the promise to accelerate the discovery of new Green Chemistry processes" with reduced environmental hazard [18].

The experimental workflow for this green chemistry optimization exemplifies the integration of material efficiency with environmental considerations.

Green Chemistry MOF Synthesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing material-efficient SDLs requires specific hardware and software components optimized for minimal consumption while maintaining experimental integrity.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Material-Efficient SDLs

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function | Material Efficiency Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Reactors | Continuous flow chips, tubular reactors [6] [15] | Miniaturized reaction environment | μL-scale volumes, continuous processing |

| In-Line Analytics | UV-Vis flow cells, IR sensors, MEMS-based detectors [6] [15] | Real-time reaction monitoring | Non-destructive analysis, minimal sampling |

| Open-Source Instrumentation | Custom potentiostats, 3D-printed components [16] [17] | Low-cost alternatives to commercial equipment | Accessibility, custom optimization for minimal consumption |

| Modular Robotic Systems | Mobile robots, multipurpose grippers [2] | Flexible equipment operation | Shared resource utilization, reduced dedicated hardware |

| Algorithmic Controllers | Bayesian optimization, multi-fidelity learning [1] [7] | Experimental selection and planning | Fewer experiments to solution, intelligent material allocation |

Comprehensive assessment of material usage in self-driving laboratories reveals significant disparities across platform architectures, with flow-based systems consistently demonstrating superior efficiency in cost, safety, and environmental impact. The emergence of standardized performance metrics [1] enables direct comparison between systems, while open-source platforms [17] and "frugal twins" [16] increasingly democratize access to material-efficient experimentation.

Future advancements will likely focus on intensified data acquisition strategies like dynamic flow experiments [6], further reducing material requirements while increasing information density. Similarly, the integration of mobile robotic systems [2] promises more flexible equipment sharing, potentially reducing redundant instrumentation across laboratories. As these technologies mature, material usage metrics will become increasingly central to SDL evaluation, reflecting broader scientific priorities of sustainability, accessibility, and efficiency in chemical research.

From Theory to Practice: Algorithms and Hardware in Action

In the drive to accelerate scientific discovery, autonomous laboratories are transforming research by integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with robotic experimentation. These self-driving labs (SDLs) operate on a closed-loop "design-make-test-analyze" cycle, where AI decision-makers are crucial for selecting which experiments to perform next [19] [20]. The choice of optimization algorithm directly impacts the efficiency with which an SDL can navigate complex, multi-dimensional chemical spaces—such as reaction parameters, catalyst compositions, or synthesis conditions—to achieve goals like maximizing yield, optimizing material properties, or discovering new compounds [21] [22].

Among the many available strategies, Bayesian Optimization (BO), Genetic Algorithms (GAs), and the A* Search have emerged as prominent, yet philosophically distinct, approaches. Each algorithm embodies a different paradigm for balancing the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of promising areas, leading to significant differences in performance, sample efficiency, and applicability [12] [23]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three AI decision-makers, framing their performance within the broader thesis of developing metrics for autonomous chemistry platforms. We summarize quantitative benchmarking data, detail experimental protocols from key studies, and provide resources to inform their application.

Core Algorithmic Principles and Comparison

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of the three AI decision-makers.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of AI Decision-Makers for Chemical Optimization

| Algorithm | Core Principle | Typical Search Space | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Uses a probabilistic surrogate model and an acquisition function to balance exploration and exploitation [21]. | Continuous & Categorical | Highly sample-efficient; handles noisy evaluations well; provides uncertainty estimates [21] [22]. | Computational cost grows with data; can be trapped by local optima in high dimensions [24]. |

| Genetic Algorithms (GAs) | A population-based evolutionary algorithm inspired by natural selection, using mutation, crossover, and selection operators [23]. | Continuous, Categorical, & Discrete | Good for global search; handles large, complex spaces; inherently parallelizable [23]. | Can require many function evaluations; performance depends on hyperparameters like mutation rate [23]. |

| A* Search | A graph search and pathfinding algorithm that uses a heuristic function to guide the search towards a goal state [12]. | Discrete & Well-Defined | Guarantees finding an optimal path if heuristic is admissible; highly efficient in discrete spaces [12]. | Requires a well-defined, discrete parameter space and a problem-specific heuristic [12]. |

Performance Benchmarking in Chemical Workflows

Quantitative benchmarking is essential for evaluating the real-world performance of these algorithms. The metrics of Acceleration Factor (AF) and Enhancement Factor (EF) are commonly used. AF measures how much faster an algorithm is relative to a reference strategy to achieve a given performance, while EF measures the improvement in performance after a given number of experiments [19]. A survey of SDL benchmarking studies reveals a median AF of 6 for advanced algorithms like BO over methods like random sampling [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison from Experimental Case Studies

| Algorithm | Application Context | Reported Performance | Comparison & Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization | Enzymatic reaction condition optimization in a 5-dimensional design space [22]. | Robust and accelerated identification of optimal conditions across multiple enzyme-substrate pairings. | Outperformed traditional labor-intensive methods; identified as the most efficient algorithm after >10,000 simulated campaigns [22]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (Paddy) | Benchmarking across mathematical functions, neural network hyperparameter tuning, and molecular generation [23]. | Robust performance across all benchmarks, avoiding early convergence and bypassing local optima. | Performed on par or outperformed BO (Ax/Hyperopt) in several tasks, with markedly lower computational runtime [23]. |

| A* Search | Comprehensive parameter optimization for synthesizing multi-target Au nanorods (Au NRs) [12]. | Targeted Au NRs with LSPR peaks under 600-900 nm across 735 experiments. | Outperformed Bayesian optimizers (Optuna, Olympus) in search efficiency, requiring "significantly fewer iterations" [12]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Benchmarking Protocol

To ensure fair comparisons, a consistent benchmarking methodology should be followed [19]:

- Define the Objective: A scalar or multi-objective function must be defined, such as reaction yield, material performance metric, or product purity.

- Run Parallel Campaigns: An active learning campaign using the test algorithm (e.g., BO) and a reference campaign (e.g., random sampling or human-directed experimentation) are conducted.

- Measure Progress: The best performance observed, ( y^_{AL}(n) ) and ( y^_{ref}(n) ), is recorded as a function of the number of experiments, ( n ).

- Calculate Metrics: The Acceleration Factor (AF) and Enhancement Factor (EF) are calculated using the formulas below, providing a quantitative measure of efficiency and improvement [19].

[ AF = \frac{n{ref}(y{AF})}{n{AL}(y{AF})}, \quad EF = \frac{y{AL}(n) - y{ref}(n)}{y^* - \text{median}(y)} ]

Detailed Methodologies from Cited Studies

Experiment 1: Multi-objective Reaction Optimization using Bayesian Optimization

- Objective: To optimize a chemical reaction for multiple objectives, such as high space-time yield (STY) and a low E-factor (environmental impact factor) [21].

- Algorithm: BO with the TSEMO (Thompson Sampling Efficient Multi-Objective) acquisition function.

- Workflow: The process begins with a small set of initial experiments. A Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model is then constructed from this data. The TSEMO acquisition function proposes the next set of reaction conditions (e.g., residence time, temperature, concentration) expected to most improve the multi-objective Pareto front. These experiments are conducted automatically, and the results are used to update the GP model. The loop repeats until convergence or exhaustion of the experimental budget [21].

- Outcome: The study successfully obtained Pareto-optimal frontiers for a case study reaction after 68-78 iterations, demonstrating BO's capability in handling complex, multi-objective chemical optimization [21].

Experiment 2: Nanomaterial Synthesis Optimization using the A* Algorithm

- Objective: To find synthesis parameters that produce Au nanorods (Au NRs) with a longitudinal surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) peak within a specific range (600-900 nm) [12].

- Algorithm: The heuristic A* search algorithm.

- Workflow: The platform uses a GPT model for initial literature mining to retrieve synthesis methods. Users edit or call automation scripts based on these methods. The PAL robotic platform executes the synthesis and characterizes the products via UV-Vis spectroscopy. The synthesis parameters and characterization data are fed to the A* algorithm, which calculates and proposes updated parameters for the next experiment. This closed-loop continues until the criteria are met [12].

- Outcome: The A* algorithm comprehensively searched the parameter space for Au NRs in 735 experiments and outperformed Bayesian optimizers (Optuna, Olympus) in search efficiency [12].

Experiment 3: Chemical Space Exploration using the Paddy Evolutionary Algorithm

- Objective: To benchmark the performance of the Paddy algorithm against BO and other optimizers for various chemical and mathematical tasks [23].

- Algorithm: The Paddy Field Algorithm (PFA), an evolutionary algorithm.

- Workflow: The Paddy algorithm operates in a five-phase process: (a) Sowing: Randomly initializes a population of seeds (parameter sets). (b) Selection: Evaluates the seeds and selects the top-performing plants. (c) Seeding: Calculates the number of seeds each selected plant generates based on its fitness. (d) Pollination: Reinforces the density of selected plants by eliminating seeds in low-density regions. (e) Sowing: Generates new parameter values for the pollinated seeds via Gaussian mutation from their parent plants. This cycle repeats until convergence [23].

- Outcome: Paddy demonstrated robust versatility and maintained strong performance across all optimization benchmarks, including hyperparameter tuning for a solvent classification neural network and targeted molecule generation, often matching or exceeding the performance of Bayesian optimization with lower runtime [23].

Workflow Diagrams

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The "research reagents" for an autonomous laboratory extend beyond chemicals to include the computational and hardware components that form the platform's core.

Table 3: Essential Components of an Autonomous Laboratory

| Component | Function & Role | Example Systems / Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Robot | Automates precise dispensing and mixing of reagents in well-plates or vials. | Opentrons OT-2, Chemspeed ISynth [12] [22] [20]. |

| Robotic Arm | Transports labware (well-plates, tips, reservoirs) between different stations. | Universal Robots UR5e [22]. |

| In-line Analyzer | Provides rapid, automated characterization of reaction products. | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, UPLC-MS, benchtop NMR [12] [22] [20]. |

| Software Framework | The central "nervous system" that integrates hardware control, data management, and executes the AI decision-maker. | Python-based frameworks, Summit, ChemOS [21] [22] [7]. |

| Electronic Lab Notebook | Manages experimental metadata, procedure definitions, and stores all results for permanent documentation and analysis. | eLabFTW [22]. |

| AI Decision-Maker | The "brain" that proposes the most informative next experiment based on all prior data. | Bayesian Optimization, Genetic Algorithms, A* Search [21] [12] [23]. |

The Rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) for Literature Mining and Experimental Planning

Within the broader thesis on performance metrics for autonomous chemistry platforms, Large Language Models (LLMs) have emerged as transformative agents. They are redefining the paradigm of scientific research by automating two foundational pillars: extracting structured knowledge from vast literature and planning complex experimental workflows [25] [26]. This guide objectively compares the capabilities of leading LLMs and specialized agents in these domains, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Performance Comparison of LLMs in Scientific Information Extraction

A critical task for autonomous research is accurately mining entities and relationships from scientific texts. The performance of general-purpose LLMs is benchmarked against specialized models below.

Table 1: Performance of LLMs in Materials Science Literature Mining (NER & RE Tasks) [25]

| Model / Approach | Task | Primary Metric (F1 Score / Accuracy) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based Baseline (SuperMat) | Named Entity Recognition (NER) | 0.921 F1 | Baseline for complex material expressions. |

| GPT-3.5-Turbo (Zero-shot) | NER | Lower than baseline | Failed to outperform baseline. |

| GPT-3.5-Turbo (Few-shot) | NER | Limited improvement | Showed only minor gains with examples. |

| GPT-4 & GPT-4-Turbo (Few-shot) | Relation Extraction (RE) | Surpassed baseline | Remarkable reasoning with few examples. |

| Fine-tuned GPT-3.5-Turbo | RE | Outperformed all models | Best performance after task-specific fine-tuning. |

| Specialized BERT-based models | NER | Competitive | Better suited for domain-specific entity extraction. |

Table 2: Benchmark Performance of Leading LLMs (Relevant Subsets) [27] [28]

| Model | Best in Reasoning (GPQA Diamond) | Best in Agentic Coding (SWE Bench) | Key Context Window |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 3 Pro | 91.9% | 76.2% | 10M tokens |

| GPT-5.1 | 88.1% | 76.3% | 200K tokens |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 87.0% | 80.9% | 200K tokens |

| GPT-4o | N/A | N/A | 128K tokens |

| Implication for Chemistry | Correlates with complex, graduate-level QA [28]. | Essential for automating experimental control and data analysis [29]. | Larger windows aid in processing long documents. |

The data indicates a clear dichotomy: while specialized or fine-tuned models currently excel at precise entity extraction, advanced general-purpose LLMs like GPT-4 and Claude Opus demonstrate superior relational reasoning and code-generation capabilities, which are crucial for planning [25] [27] [28].

Experimental Protocols for Autonomous Agent Evaluation

The performance of LLM-driven agents is validated through structured experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key tasks cited in leading research.

Objective: To evaluate an agent's ability to design accurate chemical synthesis procedures by retrieving and integrating information from the internet.

- Agent Setup: Instantiate a planner module (e.g., GPT-4) with tools for web search (GOOGLE), code execution (PYTHON), and documentation search.

- Task Prompting: Provide the agent with a plain-text prompt: "Provide a detailed synthetic procedure for compound [X]."

- Tool Execution: The agent autonomously decomposes the task: generates search queries, browses chemical databases and publications via the web search module, and validates stoichiometry or conditions via code execution.

- Output Generation: The agent returns a step-by-step procedure including reagents, quantities, equipment, and safety notes.

- Evaluation: A domain expert scores the output on a scale of 1-5 for chemical accuracy and procedural detail. A score ≥3 is considered a pass.

Objective: To demonstrate an LLM agent's capacity to manage the entire chemical synthesis development cycle.

- Agent Assembly: Deploy six specialized GPT-4-based agents: Literature Scouter, Experiment Designer, Hardware Executor, Spectrum Analyzer, Separation Instructor, Result Interpreter.

- Literature Mining & Conditioning: The Literature Scouter agent queries a connected academic database (e.g., Semantic Scholar) with a natural language request (e.g., "methods to oxidize alcohols to aldehydes using air"). It extracts and summarizes recommended procedures and conditions.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Design & Execution: The Experiment Designer agent receives the target transformation and designs a substrate scope screening experiment. The Hardware Executor translates this design into code to control automated liquid handlers (e.g., Opentrons OT-2).

- Analysis & Optimization: The Spectrum Analyzer (e.g., interpreting GC-MS data) and Result Interpreter agents evaluate outcomes. Based on feedback, the Experiment Designer can propose new condition optimization rounds.