Beyond Trial and Error: A Practical Guide to DoE vs OFAT for Optimizing Organic Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between the traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach and the systematic Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology in organic synthesis and drug development.

Beyond Trial and Error: A Practical Guide to DoE vs OFAT for Optimizing Organic Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between the traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach and the systematic Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology in organic synthesis and drug development. Tailored for researchers and development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both methods, outlines practical steps for implementing DoE, and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios. Through a validation and comparative lens, it demonstrates how DoE can lead to more efficient, robust, and insightful optimization of reaction conditions, ultimately saving time and resources while uncovering critical interaction effects that OFAT misses. The discussion is extended to include the emerging role of machine learning in augmenting DoE strategies.

OFAT vs DoE: Understanding the Core Principles and Historical Context

In the rigorous world of organic synthesis research, where the optimization of reaction conditions is paramount to achieving high yields and purity, the One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach has long served as a foundational experimental methodology. Also known as one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) or monothetic analysis, OFAT represents the classical strategy for investigating the effects of process variables on a desired outcome [1]. This method involves systematically testing individual factors—such as temperature, catalyst loading, or solvent choice—while maintaining all other parameters at constant levels [2]. Despite the emergence of more sophisticated statistical approaches like Design of Experiments (DOE), OFAT continues to hold intuitive appeal for many researchers, particularly in early-stage investigations where factor relationships are not well characterized [3].

Within the broader context of DOE versus OFAT methodologies in organic synthesis, understanding the precise definition, mechanics, and appropriate applications of OFAT is crucial for research scientists and drug development professionals. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of the OFAT approach, detailing its procedural framework, intuitive advantages, and significant limitations when applied to complex, multi-factorial chemical systems where factor interactions often dictate experimental outcomes [4].

Historical Context and Definition

The OFAT method has a long history of application across diverse scientific fields including chemistry, biology, engineering, and manufacturing [2]. As one of the earliest formalized experimental strategies, it gained widespread adoption due to its conceptual simplicity and straightforward implementation, allowing researchers to isolate the effect of individual variables without requiring complex experimental designs or advanced statistical analysis techniques [2].

OFAT is fundamentally defined as a method of designing experiments involving the testing of factors, or causes, one at a time instead of multiple factors simultaneously [1]. The core principle rests on the ceteris paribus condition—"all other things being equal"—whereby a single factor is varied across a range of values while rigorously maintaining all other parameters at fixed, constant levels [5]. This systematic isolation enables the experimenter to attribute any observed changes in the response variable directly to the manipulated factor, creating a clear, causal narrative that aligns closely with conventional scientific reasoning.

The OFAT Methodological Framework

Core Procedural Steps

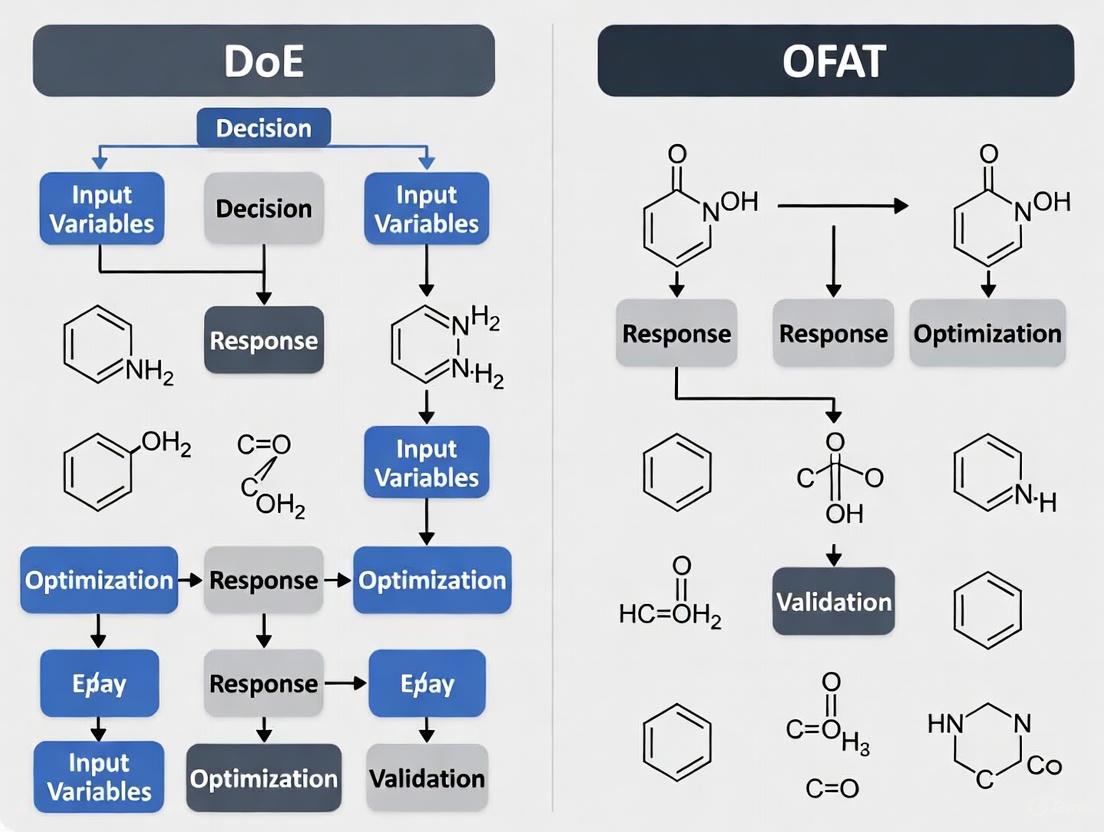

The execution of a standard OFAT investigation follows a sequential, linear pathway as illustrated in Figure 1 and detailed in the procedural steps below.

- Define the Response Variable and Potential Factors: Clearly identify the primary outcome to be optimized (e.g., reaction yield, purity, reaction time) and select the input factors hypothesized to influence this outcome [3].

- Establish Baseline Conditions: Fix all factors at predetermined constant levels that typically represent current standard operating conditions or literature values [2].

- Select a Single Factor to Investigate: Choose one variable to methodically vary while holding others constant [5].

- Vary the Selected Factor Across Defined Levels: Systematically adjust the chosen factor through a series of predetermined values (e.g., temperature: 30°C, 50°C, 70°C) [2].

- Measure the Response at Each Factor Level: Execute experiments and record the output response for each variation of the factor [2].

- Reset the Factor to Baseline Level: Return the manipulated factor to its original value before proceeding to investigate the next factor [2].

- Repeat Process Sequentially: Iterate steps 3-6 for each additional factor included in the investigation [2].

- Analyze Individual Factor Effects: Compile results to determine the apparent optimal level for each factor based on its individual performance [5].

- Identify Optimal Conditions: Combine the seemingly optimal levels for each factor to propose a global optimum for the system [5].

Representative Experimental Protocol

The following detailed protocol exemplifies a typical OFAT application in optimizing a hypothetical Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction, a transformation highly relevant to pharmaceutical development [4].

Objective: Maximize reaction yield (%) of a Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction between bromobenzene and 4-fluorophenylboronic acid.

Fixed Baseline Conditions:

- Bromobenzene: 2 mmol

- 4-fluorophenylboronic acid: 2.4 mmol

- Solvent: DMSO (5 mL)

- Catalyst: K₂PdCl₄ (1 mol%)

- Ligand: PPh₃ (0.2 mmol)

- Base: NaOH (4 mmol)

- Temperature: 60°C

- Reaction time: 24 hours

OFAT Experimental Sequence:

Temperature Optimization (Baseline: 60°C)

- Conduct reactions at: 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, 80°C

- Maintain all other factors at baseline conditions

- Analyze yields: Identify apparent optimal temperature (e.g., 70°C)

- Reset temperature to 60°C before proceeding

Catalyst Loading Optimization (Baseline: 1 mol%)

- Conduct reactions at: 0.5 mol%, 1 mol%, 2 mol%, 5 mol%

- Maintain all other factors at baseline conditions (including temperature at 60°C)

- Analyze yields: Identify apparent optimal catalyst loading (e.g., 2 mol%)

- Reset catalyst loading to 1 mol% before proceeding

Solvent Optimization (Baseline: DMSO)

- Conduct reactions with: DMSO, MeCN, DMF, Toluene

- Maintain all other factors at baseline conditions

- Analyze yields: Identify apparent optimal solvent (e.g., MeCN)

- Reset solvent to DMSO before proceeding

Continue Sequentially through remaining factors (base, ligand, concentration, etc.)

Proposed Optimal Conditions: Combine individual optimal levels (70°C, 2 mol% catalyst, MeCN solvent, etc.) as the presumed global optimum.

The Intuitive Appeal of OFAT

Despite its statistical limitations, OFAT maintains several compelling advantages that explain its persistent adoption in research environments, particularly among non-specialists and during preliminary investigations.

Table: Advantages of the OFAT Approach

| Advantage | Description | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Simplicity | Straightforward methodology that aligns with conventional scientific training [6] | Accessible to researchers without advanced statistical background [1] |

| Minimal Planning Overhead | Requires no complex experimental design or statistical software [3] | Ideal for rapid preliminary investigation of new chemical spaces [3] |

| Clear Data Interpretation | Direct cause-effect attribution for individual factors [5] | Simplifies communication of results to interdisciplinary teams |

| Adaptive Experimentation | Allows real-time modification of experimental plan based on emerging results [5] | Researcher can adjust factor ranges or abandon unproductive directions |

| Low Infrastructure Requirement | Implementable with standard laboratory equipment and practices [2] | No specialized software, statistical expertise, or automation systems needed [3] |

The intuitive logic of OFAT aligns closely with conventional scientific training, where variables are traditionally isolated to establish causal relationships [6]. This methodological familiarity lowers implementation barriers, especially in situations where data generation is inexpensive and abundant [1]. Furthermore, OFAT provides researchers with direct control over the experimental sequence, allowing for real-time adjustments based on observational insights—a flexibility that aligns with the iterative nature of exploratory chemistry [5].

Limitations in Complex Chemical Systems

While OFAT offers intuitive appeal and operational simplicity, its methodological constraints become particularly problematic when applied to complex, multi-factorial organic syntheses where factor interactions frequently determine system behavior.

Table: Key Limitations of OFAT in Organic Synthesis

| Limitation | Impact on Experimental Outcomes | Statistical Principle Violated |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to Detect Interactions | Misses synergistic/antagonistic effects between factors [2] [1] | Factor non-additivity |

| Inefficient Resource Utilization | Requires more experiments for equivalent precision [1] | Experimental inefficiency |

| Risk of False Optima | May identify suboptimal conditions due to unmeasured interactions [5] | Response surface misunderstanding |

| Limited Experimental Space Coverage | Explores only a small fraction of possible factor combinations [2] | Incomplete factor space exploration |

| No Experimental Error Estimation | Provides no inherent measure of variability or significance [2] | Lack of replication principle |

The failure to capture interaction effects represents the most significant limitation of OFAT in complex chemical systems. As demonstrated in a 2025 study published in Scientific Reports, catalytic systems "often involve multiple factors that interact synergistically or antagonistically" [4]. When OFAT ignores these interactions by varying factors individually, it risks developing "suboptimal systems" that fail to account for the true complexity of the reaction landscape [4].

This methodological shortcoming is quantitatively demonstrated in a comparative study between OFAT and minimum runs resolution-IV methods for enhancing polysaccharide production, where the statistical approach resulted in a 7.3-9.2% increase in yield compared to OFAT-optimized conditions [7]. Similarly, OFAT's requirement for "more runs for the same precision in effect estimation" makes it statistically inefficient compared to factorial designs [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials commonly investigated using OFAT approaches in optimization studies for cross-coupling reactions, along with their experimental functions [4].

Table: Key Research Reagents in Cross-Coupling Reaction Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | OFAT Investigation Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphine Ligands | PPh₃, P(4-F-C₆H₄)₃, P(4-OMe-C₆H₄)₃, P(t-Bu)₃ [4] | Modifies catalyst activity and selectivity | Electronic effects (vCO), steric bulk (Tolman's cone angle) [4] |

| Palladium Catalysts | K₂PdCl₄, Pd(OAc)₂ [4] | Facilitates cross-coupling through catalytic cycles | Catalyst loading (mol%), precursor type [4] |

| Solvents | DMSO, MeCN, DMF, Toluene [4] | Medium for reaction, influences solubility and stability | Polarity, donor/acceptor characteristics, dielectric constant [4] |

| Bases | NaOH, Et₃N [4] | Scavenges acid byproduct, activates boronic acid | Base strength, stoichiometry, nucleophilicity [4] |

| Aryl Halides | Bromobenzene, Iodobenzene [4] | Electrophilic coupling partner | Electronic effects, steric hindrance, leaving group ability |

| Nucleophiles | Phenylacetylene, 4-fluorophenylboronic acid, butylacrylate [4] | Nucleophilic coupling partner | Steric and electronic properties, stoichiometry |

Comparative Analysis: OFAT versus Statistical DoE

Understanding the fundamental differences between OFAT and Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches is essential for selecting an appropriate optimization strategy. The following table summarizes key distinctions based on methodological characteristics and output capabilities [2] [5].

Table: Direct Comparison of OFAT and DoE Methodologies

| Characteristic | OFAT Approach | DoE Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Manipulation | One factor varied at a time [5] | Multiple factors varied simultaneously [5] |

| Experimental Sequence | Sequential, linear progression [5] | Structured, parallel investigation [2] |

| Number of Experiments | Determined by experimenter [5] | Determined by statistical design [5] |

| Interaction Detection | Cannot estimate interactions between factors [2] [1] | Systematically estimates and quantifies interactions [2] |

| Precision of Estimation | Lower precision for the same number of runs [1] | Higher precision through orthogonal designs [1] [5] |

| Optimal Condition Identification | High risk of false optima in complex systems [5] | Higher probability of identifying true optimum [2] |

| Experimental Space Coverage | Limited coverage along single-dimensional paths [2] | Comprehensive coverage of multi-dimensional space [2] |

| Statistical Foundation | Based on intuitive, direct comparison | Founded on randomization, replication, and blocking principles [2] |

| Curvature Detection | Cannot reliably detect curvature in response [5] | Can detect and model curvature (e.g., via central composite designs) [2] |

| Data Analysis Framework | Simple direct comparison | Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), response surface methodology [2] |

The comparative inefficiency of OFAT becomes mathematically evident as factor count increases. For example, investigating k factors at L levels each requires L×k experimental runs in OFAT, while a full factorial DoE would require L^k runs—initially seeming to favor OFAT. However, fractional factorial and other optimized designs can extract equivalent or superior information with run counts comparable to or even lower than OFAT while capturing interactions that OFAT necessarily misses [1].

The One-Factor-at-a-Time approach represents a historically significant and intuitively accessible methodology for experimental optimization in organic synthesis. Its systematic isolation of variables, conceptual clarity, and minimal statistical requirements continue to make it appropriate for preliminary investigations and systems where factor interactions are known to be negligible [1]. However, for the complex, multi-factorial reaction systems typical of modern drug development—where interaction effects significantly influence outcomes—OFAT's limitations in efficiency, interaction detection, and optimization reliability present substantial constraints [4].

Within the broader framework of DoE versus OFAT methodologies, informed researchers must recognize that while OFAT offers a comfortable starting point for exploration, statistical DoE approaches provide a more comprehensive, efficient, and statistically rigorous pathway for optimizing complex chemical systems, particularly when augmented with modern machine learning techniques that further reduce experimental burdens [8]. The appropriate selection between these methodologies ultimately depends on the system complexity, resource constraints, and optimization goals specific to each research endeavor.

In the development of new synthetic methodology, chemists have traditionally relied on the One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) approach for reaction optimization. This method involves varying a single parameter while keeping all others constant, proceeding through sequential iterations. While intuitively simple, this approach treats variables as independent entities, operating under the assumption that optimal conditions can be found through isolated parameter adjustments [9] [10].

However, this assumption proves problematic in complex chemical systems where factor interactions significantly influence outcomes. OFAT optimization often leads to erroneous conclusions about true optimal conditions because it fails to explore the multi-dimensional "reaction space" where combinations of parameter settings can produce synergistic effects unobservable through isolated variation [9]. As illustrated in Figure 1, OFAT may identify a local optimum while completely missing the global optimum that exists in a different region of the experimental landscape. This fundamental limitation results in suboptimal processes that consume excessive time and resources while delivering inferior results [10] [4].

Table 1: Comparison of OFAT and DoE Approaches to Reaction Optimization

| Characteristic | OFAT Approach | DoE Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration of Factor Interactions | Cannot detect interactions | Systematically identifies and quantifies interactions |

| Number of Experiments | Increases linearly with factors | Increases logarithmically with factors |

| Resource Efficiency | Low (high material consumption) | High (optimized information per experiment) |

| Statistical Reliability | Limited, requires repetition | Built-in reproducibility assessment |

| Optimum Identification | Often finds local optimum | Identifies global optimum |

| Multi-Response Optimization | Sequential, often conflicting | Simultaneous optimization possible |

Fundamental Principles of Design of Experiments

What is Design of Experiments?

Design of Experiments (DoE) represents a paradigm shift in experimental approach, moving from sequential isolation to parallel investigation of multiple factors. DoE is a structured, efficient approach to experimentation that employs statistical techniques to investigate potentially significant factors and determine their cause-and-effect relationship on experimental outcomes [11]. When a relationship between experimental parameters (factors) and results exists, DoE can detect and quantify this correlation, enabling researchers to design optimal and robust processes [11].

The core principle of DoE involves identifying important factors and selecting at least two reasonable levels for each factor. After defining these factor levels, experiments are performed according to a specific experimental design. The significance of each factor is then assessed using statistical analysis of the experimental data, leading to objective, data-driven conclusions about process optimization [4].

The Statistical Foundation of DoE

The statistical framework of DoE models process responses through a mathematical equation that accounts for various types of effects. For a system with multiple input variables (x₁, x₂, x₃, etc.), the response (e.g., chemical yield) can be represented as:

Response = β₀ + β₁x₁ + β₂x₂ + β₃x₃ + ... + β₁₂x₁x₂ + β₁₃x₁x₃ + ... + β₁₁x₁² + β₂₂x₂² + ...

Where:

- β₀ represents the base constant (overall mean response)

- β₁x₁, β₂x₂, etc. are the main effects of each variable

- β₁₂x₁x₂, β₁₃x₁x₃, etc. capture two-factor interaction effects

- β₁₁x₁², β₂₂x₂², etc. account for quadratic (curvature) effects [10]

Different experimental designs incorporate different combinations of these terms. Fractional factorial designs typically capture only main effects, while full factorial designs add interaction terms. Response surface methodologies include squared terms to model curvature and identify true optimal conditions within the experimental domain [10].

Figure 1: The DoE Optimization Workflow - A systematic approach to process optimization

Key Experimental Designs and Their Applications

Screening Designs: Identifying Influential Factors

Screening designs help researchers identify which factors among many potential variables have significant effects on the response. These designs are particularly valuable in early stages of method development when numerous factors may be under consideration.

Plackett-Burman Design (PBD) is a widely used screening approach that allows investigation of up to n-1 factors in only n experiments, where n is a multiple of four [4]. For example, a 12-run Plackett-Burman design can efficiently screen 11 factors. In each experimental run, factors are set at two levels (low: -1 and high: +1), enabling researchers to quickly identify the most influential parameters for further optimization [4]. This efficiency makes PBD particularly valuable when working with expensive reagents or time-consuming analyses.

Definitive Screening Design (DSD) represents a more recent advancement that can screen multiple factors while retaining the ability to detect curvature and some two-factor interactions [12]. These designs are especially useful when the relationship between factors and responses may not be purely linear.

Response Surface Methodologies: Mapping the Optimization Landscape

Once significant factors have been identified through screening designs, response surface methodologies (RSM) provide powerful tools for locating optimal conditions and understanding the response landscape.

Central Composite Design (CCD) is the most popular RSM approach, comprising a factorial or fractional factorial design augmented with center points and axial points [12]. This arrangement allows estimation of all main effects, two-factor interactions, and quadratic terms, providing a complete picture of the response surface. CCDs can identify stationary points (maxima, minima, or saddle points) and characterize the nature of these regions [12].

Box-Behnken Design (BBD) offers an efficient alternative to CCD, requiring fewer experimental runs while still capturing quadratic effects. BBDs are rotatable designs that place experimental points on a sphere within the factor space, making them particularly useful when extreme factor combinations may be problematic or impossible to run [4].

Table 2: Common Experimental Designs and Their Applications in Synthetic Chemistry

| Design Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | Tests all possible combinations of factor levels | Initial method scouting, 2-4 factor systems | Captures all interactions, Comprehensive | Number of runs grows exponentially (2ᵏ) |

| Fractional Factorial | Tests fraction of full factorial combinations | Screening many factors (5+), Initial phase optimization | Highly efficient, Identifies key drivers | Confounds interactions (aliasing) |

| Plackett-Burman | Two-level screening design with n runs for n-1 factors | Rapid screening of many factors, Identifying active factors | Extreme efficiency, Minimal runs | Only main effects, No interactions |

| Central Composite | Three-level design with factorial, axial and center points | Response surface mapping, Final optimization | Captures curvature, Locates optimum | Higher number of runs required |

| Box-Behnken | Three-level spherical design without corner points | Response surface mapping, When extremes are problematic | Efficient for quadratic models, No extreme conditions | Poor estimation of pure quadratic terms |

| Taguchi Arrays | Orthogonal arrays with inner/outer design structure | Robust parameter design, Noise factor incorporation | Addresses variability, Process robustness | Complex analysis, Controversial statistics |

DoE in Practice: Implementation in Synthetic Chemistry

The DoE Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

Successful implementation of DoE follows a systematic workflow that maximizes information gain while minimizing experimental effort:

Define Clear Objectives: Determine which responses will be optimized (yield, selectivity, purity, etc.) and whether the goal is screening, optimization, or robustness testing [10].

Identify Factors and Ranges: Select process parameters to investigate and establish feasible ranges based on chemical knowledge and practical constraints [10].

Select Appropriate Design: Choose an experimental design aligned with objectives, considering the number of factors, resources, and desired information [10].

Execute Randomized Experiments: Perform experiments in randomized order to minimize confounding from uncontrolled variables [4].

Analyze Results Statistically: Use statistical software to identify significant factors, interactions, and build predictive models [10].

Verify and Validate: Confirm model predictions with additional experiments and validate optimal conditions [10].

Case Study: DoE in Cross-Coupling Reactions

A recent study demonstrated the power of Plackett-Burman design for screening key factors in palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, including Mizoroki-Heck, Suzuki-Miyaura, and Sonogashira-Hagihara transformations [4]. The investigation systematically evaluated five critical factors:

- Electronic effect of phosphine ligands (measured by vCO stretching frequency)

- Tolman's cone angle (steric bulkiness) of phosphine ligands

- Catalyst loading (1-5 mol%)

- Base strength (Et₃N vs. NaOH)

- Solvent polarity (DMSO vs. MeCN)

The PBD design enabled researchers to efficiently rank factor importance across different reaction types, revealing which parameters most significantly influenced yield in each transformation. This systematic approach provided deeper insight into catalyst behavior while minimizing experimental effort [4].

Advanced Application: Integrating DoE with Machine Learning

Cutting-edge applications now combine DoE with machine learning (ML) to further enhance optimization capabilities. A recent study optimized a macrocyclization reaction for organic light-emitting devices (OLEDs) by correlating five reaction factors with device performance [13]. The integrated "DoE + ML" approach employed:

- Taguchi's orthogonal arrays (L18 design) to efficiently explore the 5-factor, 3-level experimental space

- Support vector regression (SVR) to build predictive models of device performance

- Leave-one-out cross-validation to assess model accuracy and select the best predictor

- Grid search of the predictive model to identify optimal reaction conditions [13]

This integrated methodology successfully identified reaction conditions that produced crude materials yielding OLED devices with 9.6% external quantum efficiency - outperforming devices fabricated using purified materials [13].

Figure 2: Integrated DoE-ML Workflow - Combining strategic experimentation with predictive modeling

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DoE Implementation

Successful DoE implementation requires careful selection of reagents and materials that enable efficient exploration of experimental space. The following table summarizes key reagent categories and their strategic roles in DoE studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DoE Implementation in Organic Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in DoE Studies | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Systems | K₂PdCl₄, Pd(OAc)₂, Ni(cod)₂ | Vary metal source and loading to optimize catalytic activity | Loading levels (e.g., 1-5 mol%), Precursor solubility, Compatibility with ligands [4] [13] |

| Ligand Architectures | Phosphines (PPh₃, XPhos), N-Heterocyclic carbenes | Modulate steric and electronic properties to tune selectivity | Electronic effect (vCO), Tolman cone angle, Ligand:metal ratio [4] |

| Solvent Systems | DMSO, MeCN, DMF, Water, green solvents | Explore solvent space based on polarity, H-bonding, sustainability | Use solvent maps (PCA), Consider solvent properties, Environmental impact [9] |

| Base Additives | Et₃N, NaOH, K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃ | Screen base strength and solubility for deprotonation steps | Nucleophilicity vs. basicity, Solubility in reaction medium, Byproduct formation [4] |

| Substrate Variations | Aryl halides with different electronic/steric properties | Test substrate scope under optimized conditions | Electronic effects, Steric hindrance, Functional group tolerance [9] |

Design of Experiments represents a fundamental shift from traditional, empirical approaches to a systematic, statistical framework for process optimization. By simultaneously investigating multiple factors and their interactions, DoE enables researchers to uncover complex relationships that remain invisible to OFAT approaches. The methodology delivers not only optimized conditions but also deeper process understanding, revealing how factors interact to influence key responses.

The integration of DoE with emerging technologies like machine learning and high-throughput experimentation further enhances its power, creating synergistic methodologies that accelerate research while conserving precious resources [14] [13]. As the chemical industry faces increasing pressure to develop sustainable, efficient processes, adopting DoE as a standard practice provides researchers with a powerful framework for navigating complex experimental landscapes and delivering robust, optimized synthetic methodologies.

For synthetic chemists accustomed to traditional approaches, the initial investment in learning DoE principles yields substantial returns in experimental efficiency, process understanding, and ultimately, the development of superior chemical processes with reduced time and resource investment.

In the realm of organic synthesis research, the pursuit of optimal reaction conditions presents a significant challenge. Traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approaches, where only one variable is altered while all others remain constant, have historically dominated experimental practice [15]. While intuitively straightforward, OFAT methodologies possess inherent limitations, most notably their inability to detect interactions between factors—the scenario where the effect of one factor depends on the level of another [16] [2]. In complex chemical systems, where such interactions are prevalent, OFAT can lead to suboptimal conclusions and inefficient use of resources [4].

Design of Experiments (DOE) provides a superior, systematic framework grounded in statistical principles [17]. It enables researchers to simultaneously investigate the impact of multiple input factors on a desired output response, thereby capturing the true, interconnected nature of chemical processes [15] [16]. This whitepaper delineates the core terminology of DOE, framing it within the critical comparison with OFAT and illustrating its application through contemporary examples in organic synthesis and drug development. Adopting DOE empowers scientists to build robust, predictive models for their reactions, ultimately accelerating the development of synthetic routes and pharmaceutical processes [13] [18].

Core Terminology of Design of Experiments (DOE)

Foundational Concepts

Design of Experiments (DOE): A branch of applied statistics concerning the planning, conduction, analysis, and interpretation of controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [17]. It is a systematic method that allows for multiple input factors to be manipulated simultaneously, determining their effect on a desired output [17].

Factor: A process input an investigator manipulates to cause a change in the output [19]. Also defined as an independent variable that can be set to a specific level [17]. In chemical synthesis, common factors include temperature, pressure, catalyst loading, solvent polarity, and reaction time [4].

Level: The specific value or setting that a factor is set to for an experimental run [17]. For example, a temperature factor might have levels of 50°C (-1) and 100°C (+1) in a screening design [17].

Response: The output(s) of a process or the outcome being measured and analyzed in an experiment [19]. In organic synthesis, this is typically yield, purity, selectivity, or a performance metric like device efficiency [13].

Effect: A measure of how changing the settings of a factor changes the response [19]. For a factor with two levels, the effect is calculated as the difference between the average response at the high level and the average response at the low level [17].

Treatment Combination: The specific combination of the levels of several factors in a given experimental trial, also known as a "run" [19].

Advanced Terminology

Interaction: Occurs when the effect of one factor on a response depends on the level of another factor(s) [19]. Interactions are ubiquitous in complex bioprocessing and chemical systems but are impossible to detect using OFAT approaches [15] [16].

Randomization: A principle where the experimental runs are performed in a random sequence to minimize the impact of lurking variables and systematic biases, thereby enhancing the validity of the statistical analysis [17] [2].

Replication: The repetition of a complete experimental treatment, including the setup [17]. Replication allows for the estimation of experimental error and improves the precision of the estimated effects [2] [19].

Blocking: A schedule for conducting treatment combinations such that effects due to a known change (e.g., different raw material batches, operators) become concentrated in the levels of the blocking variable. Blocking is achieved by restricting randomization to isolate a systematic effect and prevent it from obscuring the main effects [17] [19].

Aliasing (or Confounding): When the estimate of an effect also includes the influence of one or more other effects (usually high-order interactions) [19]. This occurs in fractional factorial designs where not all combinations are tested, but can be designed to be unproblematic if the higher-order interaction is non-existent or insignificant [19].

Center Points: Experimental points at the center value of all factor ranges, often added to a design to check for curvature in the response [16] [19].

OFAT vs. DOE: A Conceptual and Practical Comparison

The OFAT Methodology and Its Limitations

The One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach involves varying a single factor while keeping all other factors constant, observing the response, and then repeating this process for each subsequent factor [2] [20]. Its perceived advantages are simplicity and ease of implementation, requiring no specialized statistical training [18] [20].

However, OFAT has severe limitations in complex systems like organic synthesis, including:

- Inability to Detect Interactions: This is the most critical flaw. OFAT assumes factors are independent, but in chemistry, factors like temperature and catalyst often interact. An OFAT experiment cannot reveal if a catalyst performs better at a specific temperature [15] [16].

- Inefficient Resource Use: OFAT requires a large number of experiments to explore the same space, especially as factors increase, making it time-consuming and costly [2] [4].

- Risk of Misleading Optima: By missing interactions, OFAT can easily identify a suboptimal set of conditions, as demonstrated in a case where OFAT found a maximum yield of 86% while DOE, capturing the interaction, found a true maximum of 92% [16].

- Limited Scope: OFAT only investigates a single path through the experimental region and may completely miss the global optimum [2].

The DOE Approach and Its Strategic Advantages

Design of Experiments (DOE) systematically varies multiple factors simultaneously according to a pre-determined mathematical plan [17]. This approach offers several strategic advantages, which are summarized in the table below and contrasted with OFAT.

Table 1: A systematic comparison of OFAT and DOE methodologies.

| Aspect | OFAT (One-Factor-at-a-Time) | DOE (Design of Experiments) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Varies one factor at a time while holding others constant [2]. | Systematically varies multiple factors simultaneously according to a statistical plan [17]. |

| Detection of Interactions | Cannot detect interactions between factors [16] [2]. | Explicitly models and quantifies interaction effects between factors [15] [19]. |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires many runs for multiple factors, leading to inefficient use of resources [4]. | High; extracts maximum information from a minimal number of runs, saving time and materials [15] [18]. |

| Statistical Validity | Low; no inherent estimation of experimental error or statistical significance [2]. | High; incorporates principles of randomization, replication, and blocking for reliable, defensible results [17] [2]. |

| Primary Goal | Understand the individual effect of each factor in isolation. | Model the entire system, including main effects and interactions, for optimization and prediction [16]. |

| Optimal Scope | Simple systems with few, likely independent, factors [20]. | Complex systems with multiple, potentially interacting factors [15] [13]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how OFAT and DOE explore an experimental space with two factors, Temperature and pH.

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Synthesis

Case Study 1: Optimizing a Macrocyclization Reaction for OLED Performance

A 2025 study by Ikemoto et al. provides a sophisticated example of using DOE coupled with machine learning (ML) to optimize a macrocyclization reaction, where the response was not just chemical yield but the final performance of an organic light-emitting device (OLED) [13].

- Objective: To correlate reaction conditions in the flask directly with OLED device performance (External Quantum Efficiency, EQE), thereby eliminating energy-consuming purification steps [13].

- Factors and Levels: Five factors were investigated, each at three levels [13]:

- Equivalent of Ni(cod)₂ (M)

- Dropwise addition time of monomer (T)

- Final concentration of monomer (C)

- % content of bromochlorotoluene in monomer (R)

- % content of DMF in solvent (S)

- Experimental Design: An L18 Taguchi orthogonal array was used, requiring only 18 experimental runs to efficiently explore the five-factor, three-level space [13].

- Response: The External Quantum Efficiency (EQE) of the fabricated OLED was measured in quadruplicate for each of the 18 reaction conditions [13].

- Analysis and Optimization: Machine learning models (Support Vector Regression was selected as best) were trained on the data to build a predictive map of EQE across the entire five-dimensional parameter space. The model successfully predicted an optimal condition that achieved a high EQE of 9.6%, surpassing the performance of devices made with purified materials [13].

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for the OLED macrocyclization case study [13].

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Dihalotoluene Monomer (1) | The starting material for the Yamamoto-type macrocyclization reaction. |

| Ni(cod)₂ Catalyst | The transition metal catalyst that mediates the C-C coupling to form the macrocyclic products. |

| Phosphine Ligands | Likely used as stabilizing ligands for the nickel catalyst (inferred from analogous procedures). |

| DMF (Solvent) | A polar aprotic solvent; its ratio was a key factor in the DoE. |

| Ir Emitter (3) | The dopant in the emission layer of the OLED device. |

| TPBi (2) | An electron transport material, sublimated to form the electron transport layer. |

Case Study 2: Screening Factors in Cross-Coupling Reactions

A 2025 proof-of-concept study in Scientific Reports applied a Plackett-Burman Design (PBD) to screen key factors in three fundamental cross-coupling reactions: Mizoroki-Heck, Suzuki-Miyaura, and Sonogashira-Hagihara [4].

- Objective: To efficiently screen and rank the influence of multiple factors on reaction success, overcoming the limitations of OFAT in complex catalytic systems [4].

- Factors and Levels: Five real factors were screened at two levels (high +1, low -1) using a 12-run PBD, which also included dummy factors to estimate experimental error [4]:

- Ligand Electronic Effect (vCO)

- Ligand Tolman's Cone Angle

- Catalyst Loading (1 mol% vs. 5 mol%)

- Base (Triethylamine vs. Sodium Hydroxide)

- Solvent Polarity (DMSO vs. MeCN)

- Experimental Design: A 12-run Plackett-Burman design, which is a highly efficient screening design used to identify the most influential factors from a large pool with minimal experiments [4].

- Response: The conversion or yield of the respective cross-coupled product.

- Analysis and Outcome: Statistical analysis of the results identified the most influential factors for each type of coupling reaction. This provides a data-driven basis for focusing subsequent, more detailed optimization studies (e.g., using Response Surface Methodology) on the few critical factors [4].

The workflow for a typical DoE-driven project in synthesis is summarized below.

The transition from OFAT to DOE represents a paradigm shift from a linear, isolated view of experimentation to a holistic, systems-level approach. For researchers in organic synthesis and drug development, mastering the core terminology of factors, levels, responses, and effects is the first step toward unlocking the full power of DOE [19].

As demonstrated by contemporary research, DOE is not merely a statistical tool but a critical strategic asset [13] [4]. It enables the efficient exploration of complex chemical spaces, reveals crucial interactions that OFAT blindly misses, and builds predictive models that lead to truly optimal outcomes—higher yields, superior product performance, and more sustainable processes with reduced waste and resource consumption [13] [18]. In an era of increasing process complexity and pressure for innovation, the adoption of DOE is no longer optional but essential for cutting-edge research and development.

Historical Use and Inherent Limitations of the OFAT Methodology

Within organic synthesis research, reaction optimization is a fundamental activity aimed at identifying experimental conditions that maximize yield, purity, or other critical response variables. The choice of optimization strategy profoundly impacts the efficiency, cost, and ultimate success of research and development, particularly in fields such as pharmaceutical development. The One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) methodology represents a traditional approach to this challenge, characterized by its sequential modification of experimental variables [21]. This article situates the historical use and inherent limitations of OFAT within the broader thesis of its comparison to modern Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies, providing researchers with a critical technical appraisal of its role in contemporary scientific practice.

Historical Use of OFAT in Experimental Science

The OFAT Methodology and Its Traditional Application

The OFAT approach is defined as an experimental procedure wherein a scientist iteratively performs experiments by fixing all process factors except one [21]. After identifying the best value for that single factor, that value is fixed while a subsequent set of experiments is executed to optimize another factor. This cycle continues until each factor has been optimized individually, at which point the scientist arrives at a presumed optimum set of reaction conditions [21]. This methodology has a long history of application across chemistry, biology, engineering, and manufacturing [2].

Its historical popularity stemmed from its straightforward implementation, as it could be conducted without complex mathematical modeling and aligned intuitively with how many scientists learned to conduct experiments during their training [21] [2]. In many cases, it served as a default technique, particularly in academic research settings where exposure to more advanced statistical optimization techniques was limited [21].

Table: Characteristic Steps in a Traditional OFAT Optimization Campaign

| Step | Action | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select baseline operating conditions for all factors. | Establish a starting point for optimization. |

| 2 | Vary one factor across a range of values while holding all others constant. | Identify the value of that single factor that gives the best response. |

| 3 | Fix the optimized factor at its new "best" value. | Lock in the gain for that variable. |

| 4 | Repeat steps 2 and 3 for each subsequent factor. | Sequentially optimize all variables of interest. |

| 5 | Implement the final combination of individually optimized factors. | Presume this represents the global optimum for the system. |

Representative Case Study: OFAT in Organic Synthesis

A representative example of OFAT application in organic synthesis can be found in the work of Abtahi and Tavakol (cited in [21]) for the synthesis of bioactive propargylamine scaffolds. Their optimization procedure followed a classic OFAT pattern:

- The temperature and reaction time were initially fixed while the reaction media and catalyst were optimized to obtain the highest yield.

- The optimized media and catalyst were then fixed, and the temperature and reaction time were optimized.

- Finally, with all other factors fixed, the catalyst loading was optimized. This procedure achieved a 75% yield in the model reaction, and the identified conditions were subsequently applied to several substrates, yielding 38–91% [21]. This case illustrates the stepwise, sequential nature of the OFAT approach and its capability to deliver functional, albeit potentially suboptimal, results.

Inherent Limitations of the OFAT Approach

Despite its historical prevalence and intuitive appeal, the OFAT methodology possesses several critical limitations that render it inefficient and potentially misleading for optimizing complex systems, especially in organic synthesis where factor interactions are common.

Failure to Capture Interaction Effects

The most significant drawback of the OFAT approach is its fundamental assumption that factors are independent. The method fails to capture interaction effects between variables [21] [22] [2]. In reality, chemical reaction outputs are exclusively nonlinear responses where factors often exhibit synergistic or antagonistic effects [21]. For instance, the ideal temperature for a reaction may depend on the catalyst loading, but OFAT cannot detect this relationship because when temperature is varied, the catalyst loading is held constant. By ignoring these interactions, OFAT frequently misidentifies the true optimal reaction conditions and can lead to a suboptimal understanding of the chemical process itself [21] [23].

Gross Inefficiency and Resource Intensiveness

OFAT is a highly inefficient experimental strategy. Varying each factor individually while holding others constant requires a substantially larger number of experimental runs to explore the parameter space compared to multivariate approaches like DoE [22] [2]. This leads to greater consumption of time, materials, and financial resources. Furthermore, with the increased number of experimental runs comes an elevated risk of experimental error or uncontrolled variability, which can compromise the reliability and reproducibility of the results [2].

Inability to Systematically Explore the Design Space

The OFAT approach is inherently limited in its ability to explore the entire experimental region or factor space. It only investigates factor levels along a single, narrow path and does not provide a comprehensive map of the response surface [2]. Consequently, there is a high probability that OFAT will converge on a local optimum rather than the global optimum, as it cannot "see" beyond the immediate path it is following [23]. This is particularly problematic in complex chemical systems with multiple peaks and valleys in the response landscape.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of OFAT and DoE for a Three-Factor, Two-Level Experiment

| Aspect | OFAT Approach | Full Factorial DoE (2³) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Experimental Runs | 10 (e.g., 4+3+3) | 8 |

| Information Gained | Main effects only; no interaction effects. | All main effects and all interaction effects. |

| Experimental Error Estimate | Typically not available without replication. | Can be obtained via center points. |

| Optimal Conditions Identified | Likely suboptimal due to ignored interactions. | Statistically validated global optimum. |

| Resource Efficiency | Low | High |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, narrow path of an OFAT optimization compared to the comprehensive exploration of a DoE factorial design, highlighting why OFAT can miss the true optimum.

The Modern Alternative: Design of Experiments (DoE)

Fundamental Principles of DoE

Design of Experiments (DoE) is a systematic, multivariate approach to experimentation that addresses the core limitations of OFAT. Its power derives from several key statistical principles [2]:

- Simultaneous Variation: Multiple factors are varied at once according to a structured experimental design (e.g., factorial designs), allowing for the efficient exploration of a large parameter space.

- Interaction Effects: DoE models explicitly include and can quantify the interaction effects between factors, providing a more accurate representation of the system's behavior [21] [2].

- Statistical Robustness: The methodology is built on foundational principles of randomization (to minimize bias), replication (to estimate experimental error), and blocking (to account for known sources of variability) [2].

Key Methodologies in DoE for Optimization

DoE encompasses a suite of methodologies tailored to different experimental goals, from initial screening to final optimization.

- Factorial Designs: These are the cornerstone of DoE. Full or fractional factorial designs allow researchers to study the main effects of several factors and their interactions simultaneously. The data is typically analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine the statistical significance of each effect [2].

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): When the goal is to find optimal conditions, RSM is employed. This technique uses sequential experiments (e.g., the method of steepest ascent) to rapidly move from a starting point to the vicinity of the optimum [24] [25]. Once near the optimum, more elaborate designs like Central Composite Designs (CCD) or Box-Behnken Designs (BBD) are used to fit a second-order polynomial model. This model can precisely locate the optimum settings, whether for maximizing yield, minimizing impurities, or achieving a target specification [24] [26].

The workflow below contrasts the logical progression of a DoE-based optimization campaign with the OFAT approach, demonstrating its iterative and model-based nature.

Transitioning from OFAT to DoE requires familiarity with both conceptual tools and practical software resources.

Table: Essential Tools for Modern Experimental Optimization

| Tool Category | Example | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| DoE Software | JMP, MODDE, Design-Expert [21] | Provides a user-friendly interface for generating optimal experimental designs and analyzing the resulting data statistically. |

| Statistical Programming Environments | R, MATLAB, Python [21] | Offer extensive libraries/packages for custom design generation and advanced statistical analysis, providing greater flexibility. |

| Automated Experimentation Platforms | Automated synthesis reactors, high-throughput screening systems [21] | Enable the rapid execution of the many experiments defined by a DoE protocol, drastically reducing time and labor. |

| Experimental Design Types | Full/Fractional Factorial, Central Composite, Box-Behnken, Plackett-Burman [21] [24] [23] | Blueprints for experimentation. Each is tailored to a specific goal, such as screening many factors or optimizing a few critical ones. |

The historical use of the OFAT methodology is rooted in its simplicity and accessibility, and it can yield functional results in simple systems with minimal factor interactions. However, for the complex, multivariate systems typical of modern organic synthesis and drug development, its inherent limitations—particularly the failure to capture interaction effects, its gross inefficiency, and its inability to locate a true global optimum—render it obsolete. The paradigm shift towards Design of Experiments is justified by a compelling body of evidence. DoE provides a structured, statistically rigorous framework that delivers superior optimization outcomes with a more efficient use of precious resources. For researchers committed to rigorous and efficient scientific discovery, embracing and mastering DoE is not merely an option but a professional necessity.

In the pursuit of innovation within organic synthesis and drug development, the methodology for optimizing reaction conditions stands as a critical determinant of efficiency and success. For decades, the One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) approach has been the ubiquitous, intuition-driven training in synthetic laboratories [3]. This method involves systematically varying a single parameter while holding all others constant, an process that is straightforward but inherently flawed for complex, multifactorial systems. In contrast, Design of Experiments (DoE) represents a fundamental shift towards a systematic, statistical framework that actively explores interactions between multiple variables simultaneously [13] [27]. This whitepaper argues that for modern research involving complex pathways—such as multi-step syntheses for pharmaceuticals or functional materials—transitioning from OFAT to DoE is not merely beneficial but essential. The core thesis is that DoE provides a robust, data-driven foundation for understanding complex systems, ultimately accelerating discovery, improving resource efficiency, and yielding more reliable and optimized outcomes where OFAT falls short [8].

The Critical Limitations of the OFAT Approach

The OFAT method, while useful for simple reactions with linear pathways, reveals significant deficiencies when applied to complex organic systems.

- Inefficiency and Inaccuracy: OFAT requires investigating every possible combination of parameters independently, leading to an exponential growth in required experiments. This process is "sometimes inaccurate and inefficient to achieve optimization in a real sense" [3]. It fails to account for interactions between factors, meaning the true optimum condition, often residing in the interplay of variables, can be easily missed.

- Inability to Model Interactions: The most significant flaw of OFAT is its blindness to factor interactions. In complex organic reactions, the effect of changing temperature may depend entirely on the solvent or catalyst used. OFAT cannot detect or quantify these critical interactions, leading to suboptimal conclusions and a poor understanding of the reaction landscape.

- High Resource Burden: The trial-and-error nature of OFAT, reliant on chemist intuition, consumes disproportionate amounts of time, valuable starting materials, and laboratory resources, especially as the number of relevant variables increases.

The DoE Framework: A Systematic Foundation for Complex Systems

DoE is a class of statistical methods designed to construct a model that relates input parameters to desired outputs (e.g., yield, purity, device performance) [3]. Its principles directly address the shortcomings of OFAT:

- Multifactorial Exploration: DoE is designed to vary multiple factors simultaneously according to a structured plan (e.g., factorial or fractional factorial designs). This allows for the efficient estimation of both main effects and, crucially, interaction effects between factors [27].

- Structured Efficiency: Through principles like randomization, replication, and blocking, DoE ensures reliable, statistically sound results while minimizing the number of required experimental runs [28]. Screening designs, such as Plackett-Burman or definitive screening designs, are specifically tailored to efficiently identify the most influential variables from a large set, saving considerable resources [27].

- Model-Based Prediction: The outcome of a well-executed DoE is a predictive model (often a polynomial response surface) of the system. This model allows researchers to understand the relationship between factors, visualize the response landscape, and pinpoint optimal regions with a degree of confidence impossible with OFAT.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Comparison Between OFAT and DoE Methodologies

| Aspect | One-Factor-At-a-Time (OFAT) | Design of Experiments (DoE) | Source / Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires testing all combinations of levels. Number of runs = Π (Levels for each factor). | High; uses structured arrays to maximize information. Runs can be a fraction of full factorial. | [3] [27] |

| Ability to Detect Interactions | None. Cannot quantify how one factor's effect changes with another's level. | Explicitly models and quantifies 2-factor and higher-order interactions. | [13] [27] |

| Underlying Approach | Intuition-based, sequential trial-and-error. | Statistical, model-based, and parallel. | [3] [8] |

| Optimal Solution Reliability | Low; may find local, not global, optimum due to ignored interactions. | High; maps the response surface to identify robust optima. | [13] [8] |

| Best Application Context | Simple systems with 1-2 known critical variables and negligible interactions. | Complex systems with multiple variables where interactions are suspected. | [13] [27] |

Case Study in Integration: DoE + Machine Learning for "From-Flask-to-Device" Optimization

A seminal example of DoE's power in complex systems is its integration with machine learning (ML) for optimizing organic light-emitting device (OLED) performance directly from reaction conditions, bypassing traditional purification [13]. This "from-flask-to-device" approach illustrates the paradigm shift.

Experimental Objective: To correlate the conditions of a Yamamoto macrocyclization reaction (producing a mixture of methylated [n]cyclo-meta-phenylenes) directly with the external quantum efficiency (EQE) of a fabricated OLED, eliminating separation steps.

Detailed Experimental Protocol (DoE + ML Workflow):

- Factor & Level Selection: Five reaction factors were identified: equivalent of Ni(cod)2 (M), addition time (T), final concentration (C), % content of bromochlorotoluene (R), and % content of DMF in solvent (S). Each was assigned three levels [13].

- DoE Matrix Construction: An L18 (2^1 × 3^7) Taguchi orthogonal array was selected to cover the 5-factor, 3-level design space with only 18 experimental runs [13].

- Execution & Data Collection: The 18 reactions were performed under the specified conditions. The crude mixtures were minimally worked up and used directly to fabricate double-layer OLEDs. The EQE of each device was measured in quadruplicate [13].

- Machine Learning Model Training: The dataset of 18 data points linking (M, T, C, R, S) to EQE was used to train three ML models: Support Vector Regression (SVR), Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [13].

- Model Validation & Prediction: Models were evaluated via leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). The SVR model showed the lowest mean squared error (MSE = 0.0368) and was selected. It was used to generate a predictive heatmap across the five-dimensional parameter space [13].

- Validation & Outcome: The SVR model predicted an optimal EQE of 11.3% at specific conditions. A validation experiment at those conditions yielded an EQE of 9.6 ± 0.1%, confirming the model's predictive power and surpassing the performance of devices made from purified materials (~0.9% EQE) [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Results from OLED Optimization Case Study [13]

| Metric | Value / Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| DoE Runs | 18 experiments (L18 array) | Efficiently explored 5 factors at 3 levels each. |

| Best ML Model | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Selected based on lowest LOOCV MSE (0.0368). |

| Predicted Optimal EQE | 11.3% | Identified via grid search on SVR model. |

| Experimentally Validated EQE | 9.6% ± 0.1% | Confirmed model accuracy and optimal condition. |

| EQE using Purified Materials | ~0.9% | Highlighted superiority of the DoE-optimized crude mixture. |

Visualizing the Methodological Shift

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical and procedural differences between OFAT and DoE, as well as the integrated DoE+ML workflow.

OFAT Sequential Process

DoE Parallel Model-Based Process

DoE+ML Adaptive Optimization Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for DoE-Driven Synthesis

The following table details key research reagents and solutions central to the featured OLED case study and broadly applicable in DoE-driven organic synthesis optimization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DoE in Organic Synthesis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Optimization | Example from Case Study [13] |

|---|---|---|

| Taguchi Orthogonal Arrays | Pre-defined statistical matrices that allow balanced, efficient testing of multiple factors at multiple levels with minimal runs. | L18 array used to design 18 experiments for 5 factors at 3 levels. |

| DoE Software (JMP, Minitab, etc.) | Tools to design experiments, randomize run order, analyze results, fit models, and visualize response surfaces. | Used for generating and analyzing the initial experimental design. |

| Machine Learning Platforms (Python/scikit-learn) | Environments for building predictive models (SVR, PLSR, MLP) from DoE data to enable interpolation and optimization. | SVR model trained to predict EQE from reaction conditions. |

| Automated Reactor/Sampling Systems | Enables precise control over reaction parameters (time, temp, addition) and automated sampling for high-throughput data generation. | Critical for executing the DoE matrix consistently and for self-optimization setups. |

| High-Throughput Analytics (HPLC, GC-MS) | Rapid analytical techniques to quantify yields, purity, or product distribution for many samples generated by a DoE. | MALDI-MS used to analyze product distribution in macrocyclization. |

| Nickel(0) Catalyst (e.g., Ni(cod)₂) | Transition metal catalyst for cross-coupling reactions; a critical factor whose loading is optimized. | Factor M: Equivalent of Ni(cod)₂ in Yamamoto macrocyclization. |

| Mixed Halide Substrates | Starting materials where halide ratio can influence reaction kinetics and product distribution. | Factor R: % content of bromochlorotoluene in substrate 1. |

| Solvent Blends | Mixed solvent systems used to tune reaction environment, solubility, and kinetics. | Factor S: % content of DMF in solvent mixture. |

The transition from OFAT to DoE represents more than a change in technique; it is a fundamental shift towards a data-centric, systems-thinking philosophy in research. For professionals in organic synthesis and drug development, where systems are inherently complex and resources precious, this shift is crucial. DoE provides a rigorous framework to efficiently decode multifactorial interactions, build predictive models, and arrive at robust, high-performing solutions. When augmented with machine learning—creating an adaptive, iterative optimization loop—its power is magnified, potentially reducing experimental burden by 50-80% compared to conventional approaches [8]. As demonstrated in the "from-flask-to-device" optimization, this integrated methodology can unlock novel, high-performance materials and processes that traditional, sequential methods would never reveal. Embracing DoE is, therefore, an indispensable step in advancing scientific innovation and maintaining competitive edge in modern research.

Implementing DoE in the Lab: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Synthetic Chemists

In organic synthesis research, the journey from a conceptual molecule to a successfully synthesized compound is paved with critical decisions made at the experimental design stage. The foundational choice between One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) and Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies fundamentally shapes the efficiency, reliability, and ultimate success of research outcomes. While OFAT represents the traditionally taught approach—varying one factor while holding all others constant—modern complex chemical systems increasingly reveal its limitations in capturing the interactive effects that govern synthetic outcomes [6] [2]. This guide provides a structured framework for researchers to strategically define experimental goals and select factors within the context of DoE versus OFAT approaches, enabling more efficient navigation of multi-dimensional parameter spaces in organic synthesis and drug development.

The paradigm is steadily shifting toward DoE, particularly as high-throughput experimentation (HTE) and machine learning transform reaction optimization [29]. This transition is especially critical in pharmaceutical development, where flawed experimental approaches contribute significantly to drug candidate failures [30]. By establishing clear experimental goals and strategic factor selection from the outset, researchers can avoid the "blank spots" in experimental space that plague OFAT approaches and instead build comprehensive models that capture the true complexity of chemical systems.

Understanding OFAT and DoE: Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Approach

OFAT, also known as One Variable at a Time (OVAT), represents the classical experimental approach wherein researchers examine the effect of a single factor while maintaining all other parameters at constant levels [2]. The procedural sequence involves: (1) establishing baseline conditions for all factors; (2) selecting one factor to vary across its range of interest; (3) measuring responses while keeping other factors rigidly fixed; (4) returning the varied factor to baseline before investigating the next factor; and (5) repeating this process sequentially for all factors of interest [2].

This method gained historical prominence due to its straightforward implementation and intuitive interpretation, requiring no advanced statistical knowledge for initial execution [2]. In traditional laboratory settings, OFAT aligned well with manual experimentation practices where physical setup modifications made simultaneous factor changes practically challenging. However, this apparent simplicity masks fundamental limitations in capturing the complexity of modern chemical synthesis.

Design of Experiments (DoE) Methodology

DoE represents a systematic, statistically-grounded framework for simultaneously investigating multiple factors and their interactions [2]. Rooted in principles of randomization, replication, and blocking, DoE employs structured experimental designs—such as factorial, response surface, and screening designs—to efficiently explore complex factor spaces [2] [31].

The fundamental advantage of DoE lies in its ability to decouple individual factor effects from their interactions through carefully constructed experimental arrays. Rather than exploring a single dimensional axis at a time, DoE investigates points across the entire experimental space, enabling researchers to build mathematical models that predict responses for any factor combination within the studied ranges [31]. This approach has become increasingly accessible through specialized software platforms that facilitate design generation and statistical analysis.

Comparative Analysis: OFAT versus DoE

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of OFAT and DoE approaches

| Characteristic | OFAT | DoE |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Variation | Sequential | Simultaneous |

| Interaction Detection | Cannot detect interactions | Explicitly models interactions |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low (requires many runs) | High (maximizes information per run) |

| Statistical Foundation | Limited | Robust (randomization, replication, blocking) |

| Model Building Capability | Limited to individual factors | Comprehensive mathematical models |

| Optimization Approach | Local optimization along single dimensions | Global optimization across design space |

| Resource Utilization | Inefficient use of resources | Efficient resource allocation |

Table 2: Advantages and disadvantages of OFAT and DoE

| OFAT | DoE |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Advantages |

| • Widely taught and understood [6] | • Systematic coverage of experimental space [6] |

| • Straightforward implementation [6] | • Efficient resource use [6] [2] |

| • Simple interpretation for single factors | • Identifies interaction effects [2] |

| • Enables mathematical modeling of responses [31] | |

| Disadvantages | Disadvantages |

| • Limited coverage of experimental space [6] | • Minimum entry barrier of approximately 10 experiments [6] |

| • Fails to identify interactions [6] [2] | • May require experiments anticipated to "fail" [6] |

| • May miss optimal solutions [6] | • Requires statistical knowledge for implementation |

| • Inefficient use of resources [6] [2] | • Initial learning curve for experimental design |

The critical limitation of OFAT emerges most prominently in its inability to detect factor interactions, which are fundamental to complex chemical systems [2]. Simulation studies demonstrate that OFAT finds the true process optimum only 20-30% of the time, even in simple two-factor systems [32]. This statistical blindness comes with significant resource costs—a process with 5 continuous factors requires 46 experimental runs using OFAT, while an equivalent DoE can characterize the same space in just 12-27 runs [32].

Defining Experimental Goals in Organic Synthesis

Aligning Goals with Methodological Selection

The strategic selection between OFAT and DoE begins with precise articulation of experimental goals. Different objectives in organic synthesis demand distinct methodological approaches, with OFAT retaining limited applicability for simple characterizations, while DoE delivers superior performance for optimization and modeling tasks.

Preliminary Factor Screening: In early exploratory stages where the objective is identifying influential factors from a large candidate set, DoE screening designs (e.g., fractional factorials, Plackett-Burman) provide dramatically superior efficiency. While OFAT might theoretically screen factors sequentially, it risks missing critical interactions and requires substantially more experimental runs [2].

Reaction Optimization: For optimizing yield, selectivity, or other critical responses, DoE unequivocally outperforms OFAT. The simultaneous factor variation in DoE enables researchers to model response surfaces and locate optimal conditions, including complex interactive effects that OFAT cannot detect [2] [32]. Pharmaceutical industry reports indicate DoE reduces assay development timelines by 30-70% compared to OFAT approaches [30].

Robustness Testing: When establishing operational ranges for process robustness, DoE provides comprehensive understanding of factor effects across the design space, whereas OFAT only characterizes individual factor axes, potentially missing failure modes that occur from specific factor combinations [2].

Reaction Discovery: Emerging applications of HTE combined with DoE principles enable accelerated reaction discovery by broadly exploring chemical space [14]. While OFAT relies heavily on serendipity and researcher intuition, structured experimental designs systematically probe diverse condition combinations, increasing opportunities for novel reactivity discovery.

Experimental Goal Framework

Experimental Goal Classification and Methodology Selection Workflow

Strategic Factor Selection for Effective Experimentation

Categorizing Factor Types

Strategic factor selection begins with comprehensive categorization of potential variables that may influence the synthetic process. In organic synthesis, factors typically fall into three primary classifications:

Continuous Factors: These variables span a measurable range and can be set to any value within operational limits. Examples include temperature (°C), concentration (mol/L), reaction time (hours), catalyst loading (mol%), and pressure (atm). Continuous factors are ideally suited for response surface modeling and optimization in DoE, whereas OFAT tests only discrete points along these continua.

Categorical Factors: These variables represent distinct states or types rather than numerical values. Common categorical factors in organic synthesis include solvent type (DMSO, THF, MeCN), catalyst identity (Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd(dba)₂, Ni(COD)₂), ligand class (phosphine, amine, N-heterocyclic carbene), and substrate class (aryl halides, alkyl halides). DoE handles categorical factors efficiently through structured designs, while OFAT requires complete re-optimization for each category.

Process Parameters: These factors relate to experimental execution rather than chemical composition, including addition rate (slow/fast), mixing intensity (RPM), order of addition, and quenching method. Such parameters often exhibit significant interactions with chemical factors, making them particularly poorly suited for OFAT investigation.

Factor Selection Methodology

The process of selecting factors for experimental design follows a structured approach:

Brainstorming Phase: Compile an exhaustive list of potentially influential factors through literature review, mechanistic considerations, and experimental observation. At this stage, inclusivity is preferable to premature exclusion.

Preliminary Risk Assessment: Classify each factor based on prior knowledge and mechanistic understanding into high, medium, and low influence categories. This assessment guides strategic allocation of experimental resources.

Factor Prioritization: Apply the Pareto principle to identify the vital few factors that likely account for the majority of response variation. Techniques such as cause-and-effect diagrams and failure mode effects analysis can support this prioritization.

Experimental Design Integration: Select the appropriate experimental design based on the number and type of prioritized factors. Screening designs efficiently handle large factor sets (8-20 factors), while optimization designs focus on detailed characterization of critical factors (3-6 factors).

Research Reagent Solutions for Organic Synthesis Experimentation

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for organic synthesis experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Design | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Libraries | Systematic variation of catalyst identity and loading | Enable categorical factor screening; particularly valuable in transition-metal catalyzed reactions |

| Solvent Suites | Investigation of solvent effects on reaction outcome | Cover diverse polarity, coordination, and protic/aprotic characteristics |

| Substrate Arrays | Evaluation of substrate scope and generality | Designed with systematic electronic and steric variation |

| Additive Sets | Identification of beneficial additives for yield or selectivity improvement | Include bases, acids, salts, and ligands in structured arrays |

| High-Throughput Experimentation Platforms | Miniaturization and parallelization for efficient condition screening [14] | Enable testing of hundreds to thousands of conditions with minimal reagent consumption |

| Automated Synthesis Systems | Standardization and reproducibility of experimental execution [14] | Reduce operational variability, especially valuable for reaction discovery |

Implementing DoE: Practical Protocols for Organic Synthesis

Preliminary Screening Designs

For initial factor screening where the objective is identifying influential factors from a larger set, two-level fractional factorial designs provide maximum efficiency. The implementation protocol includes:

Design Specification: Select 6-12 potentially influential factors for initial screening. For 6 factors, a resolution IV fractional factorial design (2^(6-1)) requiring 32 experimental runs preserves the ability to detect all main effects unconfounded by two-factor interactions.

Factor Range Selection: Establish scientifically reasonable ranges for each factor based on literature precedent and mechanistic considerations. Wider ranges increase effect detection power but must remain within operational limits.

Randomization Protocol: Execute experimental runs in computer-generated random order to mitigate confounding from lurking variables and time-dependent effects [2].

Response Measurement: Quantify critical responses for each run, typically including conversion, yield, and selectivity metrics. Analytical methods should provide sufficient precision to detect meaningful differences.

Statistical Analysis: Apply analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify statistically significant factors (p < 0.05) and model the relationship between factors and responses.

Response Surface Methodology for Optimization

For detailed optimization of critical factors identified through screening, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) provides comprehensive characterization:

Experimental Design Selection: Central Composite Designs (CCD) or Box-Behnken Designs (BBD) efficiently model quadratic response surfaces. For 3 factors, a CCD requires 20 runs (8 factorial points, 6 axial points, 6 center points), while a BBD requires 15 runs.