Beyond Trial and Error: A Practical Guide to Factorial Design for Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to factorial design, a powerful statistical methodology for optimizing chemical processes and pharmaceutical development.

Beyond Trial and Error: A Practical Guide to Factorial Design for Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to factorial design, a powerful statistical methodology for optimizing chemical processes and pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it contrasts the limitations of the traditional One-Variable-At-a-Time (OVAT) approach with the efficiency of systematic experimental designs. The content covers foundational principles, practical implementation workflows, and advanced strategies for troubleshooting and validating multi-factor experiments. Drawing on recent case studies from synthetic chemistry and pharmaceutical stability testing, the guide demonstrates how factorial design can significantly reduce experimental costs, uncover critical factor interactions, and accelerate development timelines while ensuring robust, data-driven outcomes.

Why Move Beyond One-Variable-at-a-Time? The Foundational Principles of Factorial Design

In the field of chemical research, the optimization of reactions and processes is a fundamental and time-consuming endeavor. Traditionally, this critical stage has been dominated by the One-Variable-At-a-Time (OVAT) approach, a methodology where a single variable is altered while all others are held constant until an apparent optimum is found [1] [2]. While intuitively simple, this method possesses severe inherent limitations that compromise both the efficiency and reliability of the optimization process. This document frames these limitations within the broader context of introducing factorial design, a statistical approach that systematically captures the complex interactions OVAT misses. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the pitfalls of OVAT is the first step toward adopting more powerful and efficient optimization strategies.

Core Limitations of the OVAT Approach

The OVAT methodology, though widely used, suffers from two critical and interconnected flaws: profound inefficiency and a fundamental inability to detect interaction effects between variables.

Experimental Inefficiency and the "Local Optima" Problem

The OVAT approach is notoriously inefficient. As each variable is investigated sequentially, the number of required experiments grows linearly with the number of variables [2]. For example, exploring just three variables at three different levels each requires a minimum of 33 = 27 experiments in a full factorial design, but an OVAT approach would typically require many more, as the path to the optimum is not direct. More critically, OVAT is highly prone to finding local optima—a good set of conditions within a limited explored space—rather than the global optimum—the best possible set of conditions across the entire experimental domain [1] [2]. This occurs because OVAT treats the complex, multi-dimensional experimental landscape as a series of one-dimensional slices, failing to map the terrain comprehensively.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of OVAT and Factorial Design for a Three-Factor Optimization

| Feature | OVAT Approach | Factorial Design (2³) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Number of Experiments | Often > 3 per variable (e.g., 9-15+) | 8 (for a two-level design) | [3] [2] |

| Ability to Detect Interactions | No | Yes | [1] [4] |

| Risk of Finding Local Optima | High | Low | [1] [2] |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low (less information per experiment) | High (more information per experiment) | [1] |

| Reported Efficiency Gain | Baseline | >2x more efficient | [1] |

The Critical Blind Spot: Missing Interaction Effects

The most significant limitation of OVAT is its inability to detect interaction effects [1] [2] [4]. An interaction occurs when the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor. In synthetic chemistry, this is commonplace; for instance, the optimal temperature for a reaction may be different at high catalyst loading than at low catalyst loading.

- Main Effects: The individual effect of a single variable on the response [4].

- Interaction Effects: The combined effect of two or more variables that is not explained by their main effects alone [4]. Treating variables as independent, as OVAT does, can lead to erroneous conclusions and a suboptimal final process. A condition identified as optimal for one variable may, in combination with another, lead to a poor outcome, a nuance OVAT is blind to. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how OVAT and factorial designs explore experimental space and account for interactions.

Case Study: OVAT Failure in Radiochemistry Optimization

A compelling example of OVAT's limitations comes from the field of radiochemistry, specifically in the development of Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination (CMRF) reactions for synthesizing PET tracers [1].

Experimental Protocol: CMRF Optimization

This case study involved optimizing the synthesis of a novel tracer, [18F]pFBC, which had proven difficult to optimize using OVAT.

- Objective: Maximize the radiochemical conversion (%RCC) of the CMRF reaction of an arylstannane precursor.

- Key Variables Investigated: The study screened several potential factors, including:

- Temperature: The reaction temperature.

- Reaction Time: The duration of the reaction.

- Stoichiometry: The molar equivalents of the copper mediator and precursor.

- Solvent Composition: The ratio and identity of solvent components [1].

- Methodology Comparison:

- OVAT Protocol: Each variable was altered sequentially while others were held constant. This required a large number of experiments and failed to yield a robust, high-performing synthesis protocol.

- DoE Protocol: A factorial screening design was first used to identify the most significant factors (e.g., temperature and copper stoichiometry). This was followed by a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) study to model the complex, non-linear behavior of these key factors and locate the true global optimum [1].

- Outcome: The DoE approach successfully identified critical interactions and optimized the synthesis with more than a two-fold greater experimental efficiency than the traditional OVAT approach [1].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for DoE Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Relevance to DoE |

|---|---|---|

| Copper Mediator | Facilitates the 18F-fluorination of arylstannane precursors. | A key variable whose stoichiometry and identity can be optimized. |

| Arylstannane Precursor | The molecule to be radiolabeled with Fluorine-18. | The substrate; its purity and structure are fixed, but its concentration is a key factor. |

| Solvent (e.g., DMF, MeCN) | The reaction medium. | Solvent composition and ratio are critical variables to test for their main and interaction effects. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., JMP, MODDE) | Software for designing experiments and analyzing results. | Crucial for generating the experimental matrix and performing multiple linear regression on the data. |

The One-Variable-At-a-Time approach, while simple, is an inadequate tool for optimizing complex chemical systems. Its inefficiency and, more importantly, its blindness to critical variable interactions lead to suboptimal processes, wasted resources, and a lack of fundamental understanding of the reaction mechanism. The alternative—factorial design and the broader framework of Design of Experiments (DoE)—provides a structured, statistical, and vastly superior methodology [1] [2]. By simultaneously varying factors, DoE maps the entire experimental landscape, revealing the interaction effects that OVAT misses and efficiently guiding researchers to the true global optimum. For any researcher serious about robust and efficient process optimization, transitioning from OVAT to factorial design is not just an option; it is a necessity.

In scientific research, particularly in chemistry and pharmaceutical development, understanding how multiple variables simultaneously influence an outcome is crucial. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, where only a single variable is altered while others are held constant, present significant limitations for understanding complex systems. These approaches fail to detect interaction effects between factors, which can lead to incomplete or misleading conclusions about how a system truly functions [5]. R.A. Fisher famously argued against this limited approach, stating that "Nature... will best respond to a logical and carefully thought out questionnaire; indeed, if we ask her a single question, she will often refuse to answer until some other topic has been discussed" [5].

Factorial design addresses these limitations by systematically investigating how multiple factors—and their interactions—affect a response variable. In a full factorial experiment, all possible combinations of the levels of all factors are studied [5]. This comprehensive approach enables researchers to:

- Determine the individual (main) effect of each factor on the response [6]

- Identify and quantify interaction effects that occur when the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor [6]

- Develop predictive models that accurately describe system behavior across a range of conditions [7]

The application of factorial design is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, where it has been used to efficiently screen multiple antiviral drugs and identify optimal combinations for suppressing viral infections with minimal cytotoxicity [7].

Core Concepts and Terminology

Fundamental Definitions

- Factors: The independent variables or inputs being studied in an experiment (e.g., temperature, concentration, catalyst type). Factors are the main categories explored when determining the cause of changes in the response variable [4].

- Levels: The specific values or settings at which each factor is tested (e.g., for temperature: 50°C and 70°C). A level represents one subdivision within a factor [4].

- Response Variable: The dependent variable or measured output that is influenced by the factors (e.g., reaction yield, purity, reaction rate).

- Treatment Combination: A unique experimental condition formed by combining one level from each factor [5].

- Main Effect: The average change in the response variable when a factor moves from its low level to its high level, averaged across all levels of other factors [6] [8]. It represents the individual contribution of a single factor to the overall response.

- Interaction Effect: Occurs when the effect of one factor on the response variable depends on the level of another factor [6]. Interactions indicate that factors are not acting independently on the response.

Types of Factorial Designs

Factorial designs are classified based on their structure and complexity:

Table 1: Classification of Common Factorial Designs

| Design Type | Structure | Number of Runs | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | k factors at s levels each | s^k | Comprehensive study of all main effects and interactions |

| 2^k Factorial | k factors at 2 levels each | 2^k | Screening designs to identify important factors [8] |

| Fractional Factorial | k factors at 2 levels each | 2^(k-p) | Screening many factors when resources are limited [7] |

| Mixed-Level | Factors with different numbers of levels | Varies | Studies where factors naturally have different numbers of levels of interest |

Notation Systems

Several notation systems are used in factorial designs to efficiently represent factor levels and treatment combinations [5]:

- Numeric Coding (0,1): Low level = 0, High level = 1

- Geometric Coding (-1,+1): Low level = -1, High level = +1

- Yates Notation: Lowercase letters indicate the high level of factors [8]

Table 2: Notation Systems for a 2^2 Factorial Design

| Factor A | Factor B | Numeric (0,1) | Geometric (-1,+1) | Yates Notation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 00 | - - | (1) |

| High | Low | 10 | + - | a |

| Low | High | 01 | - + | b |

| High | High | 11 | + + | ab |

Advantages of Factorial Designs

Factorial designs offer significant advantages over traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) experimental approaches [5]:

Statistical Efficiency: Factorial designs provide more information per experimental run than OFAT experiments. They can identify optimal conditions faster and with similar or lower cost than studying factors individually.

Interaction Detection: The ability to detect interactions between factors is perhaps the most critical advantage. When the effect of one factor differs across levels of another factor, this cannot be detected by OFAT experiments. Use of OFAT when interactions are present can lead to serious misunderstanding of how the response changes with the factors [5].

Broader Inference Space: Factorial designs allow the effects of factors to be estimated across multiple levels of other factors, yielding conclusions that remain valid across a wider range of experimental conditions.

A compelling industrial example from bearing manufacturer SKF illustrates these advantages. Engineers tested three factors (cage design, heat treatment, and outer ring osculation) in a 2×2×2 factorial design. The experiment revealed an important interaction: while cage design alone had little effect, the combination of specific heat treatment and osculation settings increased bearing life fivefold—a discovery that had been missed in decades of previous testing using OFAT approaches [5].

Types of Effects and Their Interpretation

Main Effects

A main effect represents the average change in the response when a factor moves from its low level to its high level, averaged across all levels of other factors [6]. In a 2^k design, the main effect of a factor is calculated as the difference between the average response at its high level and the average response at its low level [8].

For factor A, this is expressed as: [ A = \bar{y}{A^+} - \bar{y}{A^-} ] Where (\bar{y}{A^+}) is the average of all observations where A is at its high level, and (\bar{y}{A^-}) is the average of all observations where A is at its low level [8].

Interaction Effects

An interaction effect occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor [6]. Interactions come in different forms with distinct interpretations:

- Spreading Interaction: Occurs when a factor has an effect at one level of another factor but little or no effect at another level [6]. The lines on an interaction plot are not parallel, but they do not cross.

- Crossover Interaction: Occurs when a factor has effects in opposite directions at different levels of another factor [6]. The lines on an interaction plot cross each other.

Interactions can be visualized by plotting the average response for each combination of factor levels. When the lines connecting these means are not parallel, an interaction is present.

Simple Effects

When significant interactions are detected, researchers often conduct simple effects analyses to understand the nature of the interaction [6]. A simple effect analysis examines the effect of one independent variable at each level of another independent variable. For example, if an A×B interaction is significant, researchers would examine:

- The effect of A at each level of B

- The effect of B at each level of A

This approach provides greater insight into the specific conditions under which factors influence the response variable.

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

Planning a Factorial Experiment

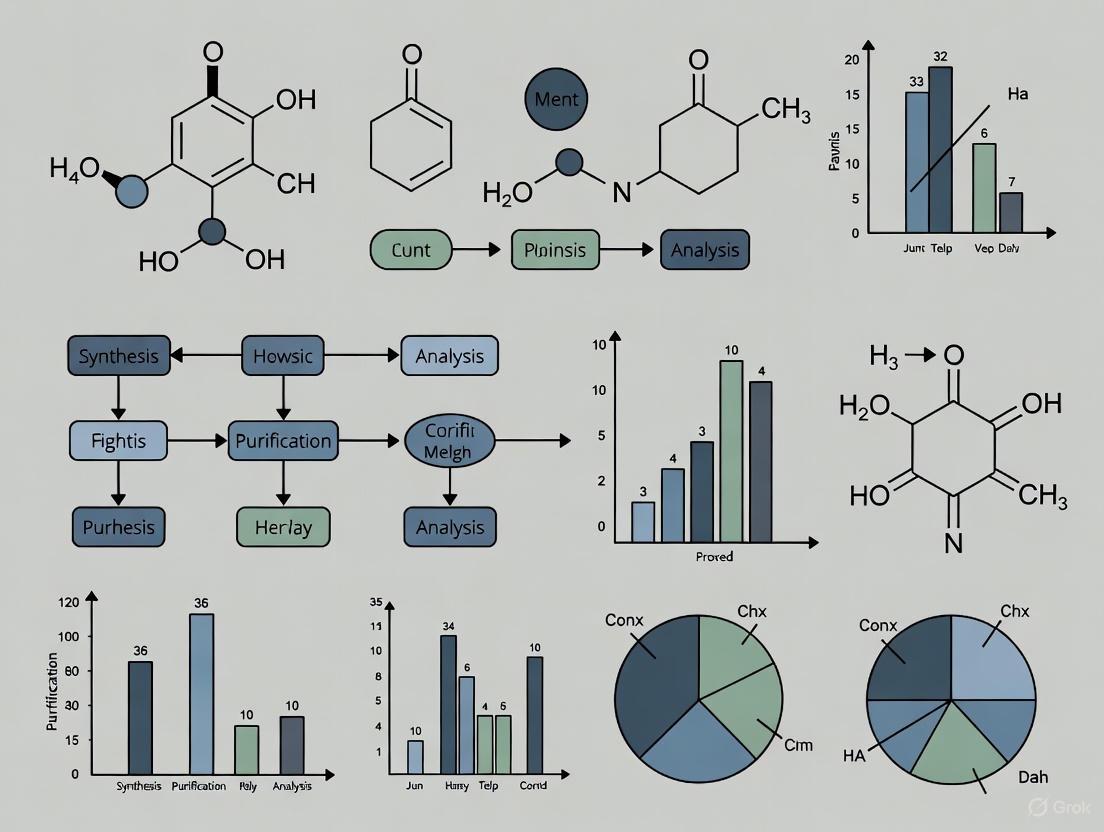

Figure 1: Factorial Design Experimental Workflow

Detailed Methodological Protocol

Based on an antiviral drug combination study [7], the following protocol provides a framework for implementing factorial designs in chemical and pharmaceutical research:

Step 1: Factor and Level Selection

- Identify all potentially influential factors based on prior knowledge, theoretical understanding, or preliminary experiments

- For screening experiments, select a minimum of two levels for each factor (typically high and low values representing a realistic range of interest)

- For quantitative factors, choose levels that span the region of operability and interest

- Document the rationale for factor and level selection

Step 2: Experimental Design Construction

- For a small number of factors (typically ≤4), consider a full factorial design to estimate all main effects and interactions

- For a larger number of factors (typically ≥5), employ fractional factorial designs to reduce the number of experimental runs while still estimating main effects and lower-order interactions [7]

- For a 2^(k-p) fractional factorial design, carefully select the generator(s) to control the aliasing pattern (which effects are confounded with each other)

Step 3: Replication and Randomization

- Include sufficient replicates to ensure adequate statistical power for detecting effects of practical importance

- For 2^k designs with n replicates, the total number of runs is n×2^k

- Randomize the order of experimental runs to minimize the impact of lurking variables and time-related effects

Step 4: Data Collection

- Establish standardized procedures for conducting each experimental run and measuring responses

- Implement quality control measures to ensure consistency across all runs

- Record all relevant experimental conditions and observations

Step 5: Statistical Analysis

- Calculate main effects and interaction effects

- Conduct statistical tests to determine which effects are statistically significant

- Create appropriate visualizations (effect plots, interaction plots, etc.)

- Develop a mathematical model relating the factors to the response

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Calculating Effects in 2^k Factorial Designs

In a 2^k factorial design, effects are calculated using contrasts of the treatment combination totals [8]. The general formula for an effect is:

[ \text{Effect} = \frac{\text{Contrast}}{2^{(k-1)}n} ]

Where the "Contrast" is the sum of the treatment combination totals multiplied by their corresponding contrast coefficients (+1 or -1), and n is the number of replicates.

For a 2^2 design with n replicates, the main effects and interaction effect can be calculated as follows [8]:

- Main effect of A: ( A = \frac{a + ab - (1) - b}{2n} )

- Main effect of B: ( B = \frac{b + ab - (1) - a}{2n} )

- AB interaction: ( AB = \frac{ab + (1) - a - b}{2n} )

Where (1), a, b, and ab represent the total of all observations for each treatment combination.

Statistical Testing and Model Evaluation

After calculating effects, statistical tests determine which effects are statistically significant. The t-statistic for testing an effect is:

[ t = \frac{\text{Effect}}{\sqrt{\frac{MSE}{n2^{k-2}}}} ]

Which follows a t-distribution with 2^k(n-1) degrees of freedom [8].

Several statistics help evaluate the overall model:

- S: Represents the standard deviation of the distance between the data values and the fitted values. Lower S values indicate the model better describes the response [9].

- R²: The percentage of variation in the response explained by the model [9].

- Adjusted R²: Modified version of R² that accounts for the number of predictors in the model, making it more appropriate for comparing models with different numbers of predictors [9].

- Predicted R²: Indicates how well the model predicts responses for new observations. A predicted R² substantially less than R² may indicate overfitting [9].

Analyzing Interactions

When interactions are present, they should be interpreted before main effects, as interactions can alter the meaning of main effects [6]. For example, in a study on caffeine and verbal test performance, researchers found a crossover interaction: introverts performed better without caffeine, while extraverts performed better with caffeine. The main effects of caffeine and personality were not significant when averaged across all conditions, masking the important interaction effect [6].

Case Study: Antiviral Drug Combination Screening

A study investigating six antiviral drugs against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1) demonstrates the practical application of factorial designs in pharmaceutical research [7]. The researchers faced the challenge of evaluating an impossibly large number of potential drug combinations (117,649 for six drugs at seven dosage levels each) and employed sequential fractional factorial designs to efficiently identify promising drug combinations.

Research Objective: Identify which of six antiviral drugs (Interferon-alpha, Interferon-beta, Interferon-gamma, Ribavirin, Acyclovir, and TNF-alpha) and their interactions most effectively suppress HSV-1 infection.

Experimental Approach: The researchers used a sequential approach [7]:

- Initial screening with a two-level fractional factorial design

- Follow-up experiment using a blocked three-level fractional factorial design to address model inadequacy and refine optimal dosages

Experimental Design and Results

The initial experiment used a 2^(6-1) fractional factorial design with 32 runs (half the number of a full 2^6 design) [7]. The generator F = ABCDE was used, creating a Resolution VI design that allowed estimation of all main effects and two-factor interactions under the assumption that four-factor and higher interactions were negligible.

Table 3: Key Findings from Antiviral Drug Screening Study [7]

| Factor | Drug Name | Relative Effect Size | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| D | Ribavirin | Largest | Most significant effect on minimizing virus load |

| A | Interferon-alpha | Moderate | Contributing factor to virus suppression |

| B | Interferon-beta | Moderate | Contributing factor to virus suppression |

| C | Interferon-gamma | Moderate | Contributing factor to virus suppression |

| E | Acyclovir | Moderate | Contributing factor to virus suppression |

| F | TNF-alpha | Smallest | Negligible effect on minimizing virus load |

The analysis identified Ribavirin as having the largest effect on minimizing viral load, while TNF-alpha showed the smallest effect [7]. The fractional factorial approach enabled researchers to test only 32 of the 64 possible combinations in the initial screening while still obtaining meaningful information about main effects and two-factor interactions.

Optimization and Follow-up

When the initial two-level experiment showed evidence of model inadequacy, researchers conducted a follow-up experiment using a blocked three-level fractional factorial design [7]. This allowed them to:

- Estimate curvature effects that cannot be detected in two-level designs

- Refine drug dosage recommendations

- Develop contour plots to visualize optimal drug combinations

The sequential application of different factorial designs provided an efficient strategy for first screening important factors and then optimizing their levels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Factorial Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Antiviral Drugs (e.g., Ribavirin, Acyclovir) | Direct therapeutic agents against viral targets | Virology research, drug combination studies [7] |

| Interferons (alpha, beta, gamma) | Immunomodulatory proteins with antiviral activity | Studying immune response in antiviral therapies [7] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Host environment for viral replication studies | In vitro assessment of antiviral efficacy [7] |

| Viral Load Assay Kits | Quantification of viral replication | Primary response measurement in antiviral studies [7] |

| Statistical Software (e.g., Minitab, R) | Experimental design and data analysis | Effect calculation, model fitting, and visualization [9] |

Advanced Concepts and Extensions

Fractional Factorial Designs

When studying many factors, full factorial designs require prohibitively large numbers of experimental runs. Fractional factorial designs address this by strategically testing only a fraction of the full factorial combinations [7]. The key considerations for fractional factorial designs include:

- Resolution: Determines the degree of aliasing (confounding) between effects. Higher resolution designs confound main effects with higher-order interactions [7].

- Aliasing Structure: The pattern of which effects are confounded with each other. For example, in a 2^(6-1) design with generator F = ABCDE, main effects are aliased with five-factor interactions [7].

- Sequential Experimentation: Often, fractional factorial designs are used in initial screening, followed by more focused experiments on the important factors identified.

Response Surface Methodology

After identifying important factors through factorial screening experiments, response surface methodology (RSM) can be employed to find optimal factor settings. RSM typically uses central composite designs or Box-Behnken designs to fit quadratic models that can identify maxima, minima, and saddle points in the response surface.

Figure 2: Sequential Experimentation Strategy

Factorial designs provide a powerful framework for systematically studying multiple factors and their interactions in chemical and pharmaceutical research. By simultaneously varying multiple factors, these designs enable efficient exploration of complex experimental spaces and detection of interactions that would be missed in one-factor-at-a-time approaches. The case study on antiviral drug combinations demonstrates how sequential application of factorial designs—from initial screening to optimization—can yield meaningful insights while conserving resources.

As research questions grow increasingly complex, the strategic implementation of factorial designs and their extensions will continue to play a critical role in advancing scientific understanding and technological innovation across chemistry, pharmaceutical development, and related fields.

In chemistry research, particularly in areas such as analytical method development and process optimization, a factorial design is a highly efficient class of experimental designs that investigates how multiple factors simultaneously influence a specific outcome, known as the response variable [10] [5]. This approach allows researchers to obtain a large amount of information from a relatively small number of experiments, making it especially valuable when experimental runs are limited or costly [10]. Unlike the traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach, factorial designs enable the study of interaction effects between factors, which OFAT experiments cannot detect and whose absence can lead to serious misunderstandings of how a system behaves [5].

The methodology was pioneered by statistician Ronald Fisher, who argued in 1926 that "complex" designs were more efficient than studying one factor at a time. He suggested that "Nature... will best respond to a logical and carefully thought out questionnaire; indeed, if we ask her a single question, she will often refuse to answer until some other topic has been discussed" [5]. This philosophy is particularly pertinent in chemical systems where factors such as pH, temperature, and concentration often interact in complex ways.

Core Terminology and Definitions

Fundamental Concepts

- Factor: An independent variable that is deliberately manipulated by the researcher to determine its effect on the response variable. In chemistry, examples include pH, temperature, catalyst concentration, and mobile phase composition [10] [4].

- Level: The specific values or settings at which a factor is maintained during the experiment. For a two-level design, these are typically designated as "low" and "high" and can be coded as -1 and +1 or 0 and 1 [10] [5].

- Response: The dependent variable or the outcome being measured in the experiment. This is the quantitative result that is hypothesized to change as the factor levels are varied. Examples include chemical yield, purity, reaction rate, or chromatographic retention [10] [4].

- Treatment Combination: A unique experimental condition formed by combining one level from each factor. In a full factorial design, every possible treatment combination is tested [5].

- Cell Mean: The expected or average response to a given treatment combination, often denoted by the Greek letter μ (mu) [5].

Design Notation

Factorial experiments are described by the number of factors and the number of levels for each factor [5]. The notation is typically a base raised to a power:

- The base indicates the number of levels for each factor.

- The exponent indicates the number of factors.

Table 1: Common Factorial Design Notations

| Design Notation | Number of Factors | Levels per Factor | Total Treatment Combinations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2² | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 2³ | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| 2⁴ | 4 | 2 | 16 |

| 2×3 | 2 | 2 and 3 | 6 |

For example, a 2³ factorial design has three factors, each at two levels, resulting in 2×2×2=8 unique experimental conditions [10] [5]. This design is common in initial screening experiments in chemical research.

Main Effects and Interaction Effects

Main Effects

A main effect is the effect of a single independent variable on the response variable, averaging across the levels of all other independent variables in the design [6] [11]. Thus, there is one main effect to estimate for each factor included in the experiment.

In a two-factor design, the main effect for Factor A is the difference between the average response at the high level of A and the average response at the low level of A, computed by averaging over all levels of Factor B [6]. The presence of a main effect indicates a consistent, overarching influence of that factor on the outcome, regardless of the settings of other factors.

Interaction Effects

An interaction effect occurs when the effect of one independent variable on the response depends on the level of another independent variable [6] [11]. In other words, the impact of one factor is not consistent across all levels of another factor. Interactions are a central reason for using factorial designs, as they cannot be detected or estimated in one-factor-at-a-time experiments [5].

Interactions can be understood through everyday examples, such as drug interactions, where the combination of two drugs produces an effect that is different from the simple sum of their individual effects [6]. In chemistry, a classic example is found in kinetics, where three-component rate expressions (e.g., Rate = k[A][B][C]) represent a three-way interaction [10].

Types of Interactions

- Spreading Interaction: One independent variable has an effect at one level of a second variable but has a weak or no effect at another level of the second variable [6]. The effect of one factor "spreads" or changes magnitude across the levels of another.

- Crossover Interaction: One independent variable has effects at both levels of a second variable, but the effects are in opposite directions [6]. This is visually represented by non-parallel lines that cross over each other on an interaction plot.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A Typical Workflow for a 2² Factorial Design

The following workflow, modeled on standard practices in chemical and pharmaceutical research [10] [11], outlines the key steps for planning, executing, and analyzing a simple two-factor experiment.

Detailed Protocol: A Pharmaceutical Case Study

This protocol is adapted from a hypothetical study investigating factors affecting the yield of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [11].

1. Objective Definition:

- Primary Objective: To determine the effects of reaction temperature (Factor A) and catalyst concentration (Factor B) on the percentage yield of API.

- Response Variable: Percentage yield (a continuous variable), measured by HPLC analysis.

2. Factor and Level Selection:

- Factor A (Temperature): Low Level (60°C), High Level (80°C)

- Factor B (Catalyst Concentration): Low Level (1 mol%), High Level (2 mol%)

- This creates a 2² design with 4 treatment combinations.

3. Experimental Plan and Randomization:

- The four treatment combinations are: (60°C, 1%), (60°C, 2%), (80°C, 1%), (80°C, 2%).

- To avoid confounding from lurking variables, the run order of these four conditions should be fully randomized.

- Replication: Each treatment combination is run in triplicate (n=3), leading to a total of 12 experimental runs.

4. Execution and Data Collection:

- For each run, the reaction is set up in a controlled laboratory reactor according to the specified levels of temperature and catalyst.

- After reaction completion, the crude product is isolated, and the percentage yield is determined via a standardized HPLC method.

5. Data Analysis:

- Data are analyzed using a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) [11].

- The two-way ANOVA tests three null hypotheses simultaneously:

- There is no main effect for Factor A (Temperature).

- There is no main effect for Factor B (Catalyst Concentration).

- There is no interaction effect between A and B (A×B).

- The results of the ANOVA provide F-statistics and p-values for each of these three effects.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Example Data Set and Calculations

Table 2: Hypothetical Data for a 2² Factorial Experiment in API Synthesis

| Temperature | Catalyst Concentration | Replicate 1 Yield (%) | Replicate 2 Yield (%) | Replicate 3 Yield (%) | Cell Mean (μ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60°C (Low) | 1% (Low) | 65.0 | 67.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 |

| 60°C (Low) | 2% (High) | 70.0 | 72.0 | 71.0 | 71.0 |

| 80°C (High) | 1% (Low) | 78.0 | 80.0 | 79.0 | 79.0 |

| 80°C (High) | 2% (High) | 85.0 | 87.0 | 86.0 | 86.0 |

Calculating Main Effects:

- Main Effect of Temperature: Average yield at high temp - Average yield at low temp = [(79 + 86)/2] - [(66 + 71)/2] = (82.5) - (68.5) = +14.0%

- Main Effect of Catalyst: Average yield at high catalyst - Average yield at low catalyst = [(71 + 86)/2] - [(66 + 79)/2] = (78.5) - (72.5) = +6.0%

Calculating Interaction Effect:

- The temperature effect at low catalyst is: 79 - 66 = 13

- The temperature effect at high catalyst is: 86 - 71 = 15

- The interaction effect is half the difference of these simple effects: (15 - 13)/2 = +1.0

- A positive interaction suggests that the effect of temperature is slightly stronger when catalyst concentration is high.

Visualizing Effects

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the core concepts of a factorial experiment and the statistical results obtained from its analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for a Factorial Experiment in Chemical Synthesis

| Item | Function/Justification |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Starting Materials | Ensures reproducible reaction outcomes and minimizes variability introduced by impurities. |

| Catalysts (e.g., Metal complexes, Enzymes) | The factor under investigation; purity and precise quantification are critical. |

| Solvents (Anhydrous, HPLC Grade) | Provides the reaction medium; consistent grade prevents unintended side reactions. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., API Reference Standard) | Essential for calibrating analytical instruments (HPLC, GC) to ensure accurate response measurement. |

| Internal Standards (for Quantitative Analysis) | Used in chromatographic analysis to improve the accuracy and precision of yield calculations. |

| Buffer Solutions (for pH-controlled experiments) | Used to maintain pH at a specific level when it is a controlled factor in the experiment. |

Advanced Concepts and Variations

Fractional Factorial Designs

When the number of factors increases, a full factorial design can become prohibitively large. A fractional factorial design (FrFD) is a balanced subset (e.g., one-half, one-quarter) of a full factorial design [10] [12]. This approach allows researchers to screen a large number of factors efficiently with fewer experimental runs, but it comes at a cost: aliasing [12].

Aliasing, or confounding, occurs when there are insufficient experiments to estimate all potential model terms independently. This means that some effects (e.g., a main effect and a two-factor interaction) are mathematically blended and cannot be separated [12]. The resolution of a fractional factorial design describes the degree of aliasing [12]:

- Resolution III: Main effects are aliased with two-factor interactions.

- Resolution IV: Main effects are clear, but two-factor interactions are aliased with each other.

- Resolution V: Main effects and two-factor interactions are clear of each other.

Beyond Two-Level Designs: Curvature and Center Points

Two-level factorial designs are limited to fitting linear (straight-line) effects and interactions; they cannot detect curvature in the response surface, which would require a factor to be tested at three or more levels [10] [12]. To check for curvature, researchers often add center points—experimental runs at the mid-point of each factor's range [12]. If the average response at the center points is significantly different from the average of the factorial points, it suggests curvature is present, indicating the need for a more complex model, such as a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design [12].

Mastering the core terminology of factorial designs—factors, levels, responses, main effects, and interaction effects—is fundamental for chemists and pharmaceutical scientists seeking to optimize processes and understand complex systems. The structured approach of factorial experimentation provides a powerful and efficient methodology for extracting maximum information from experimental data, moving beyond the limitations of one-factor-at-a-time studies. By correctly designing, executing, and analyzing these experiments, researchers can not only determine the individual impact of key variables but also uncover the critical interactions that often drive chemical phenomena, leading to more robust and profound scientific insights.

In the empirical world of chemistry research, from pharmaceutical development to process optimization, understanding the complex interplay of multiple variables is paramount. Factorial design is a cornerstone statistical method that moves beyond the traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach, enabling researchers to efficiently determine the effects of several independent variables (factors) and their interactions on a response variable simultaneously [4] [13]. This methodology provides a structured, mathematical framework for deconstructing the model behind any observed experimental response, offering a powerful "statistical equation" for discovery.

The limitations of the OFAT approach are significant; it fails to detect interactions between factors and can be inefficient and time-consuming [13]. In contrast, a factorial design tests all possible combinations of the factors and their levels. For example, with two factors, such as reaction temperature and catalyst concentration, each set at two levels (e.g., high and low), a full factorial experiment would consist of 2 x 2 = 4 unique experimental conditions [14]. This comprehensive approach allows chemists to not only assess the individual (main) effect of each factor but also to determine if the effect of one factor (e.g., temperature) depends on the level of another factor (e.g., catalyst concentration)—a phenomenon known as an interaction effect [13] [14]. The ability to detect and quantify these interactions is one of the most critical advantages of factorial design, as they are common in complex chemical systems [4].

The Mathematical Foundation of the Model

The statistical model that deconstructs an experimental response in a factorial design is built upon fundamental concepts of quantitative analysis. In any measurement, scientists must distinguish between accuracy (closeness to the true value) and precision (the reproducibility of a measurement) [15]. The precision of replicate measurements is quantified using the sample standard deviation ((s)), which provides an estimate of the dispersion of the data around the sample mean [16] [15].

For a finite set of (n) replicate measurements, the sample mean ((\bar{x})) and sample standard deviation ((s)) are calculated as follows [16] [15]:

Sample Mean ((\bar{x})): (\bar{x} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} xi}{n}) The average value of the replicate measurements.

Sample Standard Deviation ((s)): (s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}}) *The average spread of the measurements around the mean._

These parameters are essential for reporting results in a scientifically meaningful way, typically in the format: Result = (\bar{x} \pm \Delta), where (\Delta) is the confidence interval [15]. The confidence interval, calculated using the estimated standard deviation and a critical value from the (t)-distribution ((t)), provides a range within which the true population mean is expected to lie with a certain level of probability (e.g., 95%) [15]. This formal reporting acknowledges the inherent uncertainty in all experimental data.

Core Statistical Measures for Reporting

The following table summarizes the key quantitative measures used to describe a set of experimental data.

Table 1: Key Statistical Measures for Data Analysis in Chemistry

| Measure | Symbol | Formula | Interpretation in the Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Mean | (\bar{x}) | (\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} xi}{n}) | The central tendency or average value of the measured response (e.g., average yield from replicate syntheses). |

| Sample Variance | (s^2) | (\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}) | The average of the squared deviations from the mean, representing the spread of the data. |

| Sample Standard Deviation | (s) | (\sqrt{s^2}) | The most common measure of precision or dispersion of the measurements, in the same units as the mean. |

| Confidence Interval (95%) | (\Delta) | (\pm t \cdot \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}) | The range around the mean where there is a 95% probability of finding the "true" value, assuming no systematic error [15]. |

The Factorial Design Framework

Fundamental Concepts and Notation

A factorial experiment is defined by its treatment structure, which is built from several key components [13] [14]:

- Factor: A major independent variable (e.g., temperature, pressure, concentration, catalyst type).

- Level: A specific subdivision or setting of a factor (e.g., 50°C and 80°C for a temperature factor).

- Experimental Run/Treatment: A unique combination of the levels of all factors.

- Main Effect: The consistent, primary effect of a single factor averaged across the levels of all other factors [4] [14].

- Interaction Effect: Occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor [13] [14]. This indicates that the factors are not independent in their influence on the outcome.

The design is denoted as (k^m), where (m) is the number of factors and (k) is the number of levels for each factor. The most basic and widely used design is the 2² factorial, involving two factors, each with two levels (e.g., low and high) [13]. The total number of experimental runs required for a full factorial design is the product of the levels of all factors. For example, a 2³ design (three factors, two levels each) requires 8 runs, while a 3² design (two factors, three levels each) requires 9 runs [13].

Types of Factorial Designs

The choice of a specific factorial design depends on the number of factors to be investigated and the resources available.

- Full Factorial Design: The most comprehensive approach, it includes all possible combinations of the levels of all factors [13]. While it provides complete information on all main effects and interactions, the number of runs grows exponentially with the number of factors (e.g., 2⁴ = 16 runs, 2⁵ = 32 runs), making it impractical for a large number of factors [13].

- Fractional Factorial Design: A carefully chosen subset (fraction) of the runs in a full factorial design [13]. This approach is highly efficient and is used when the number of factors is large, as it significantly reduces the experimental workload. The trade-off is that some interaction effects, particularly higher-order ones, may become confounded (aliased) with main effects or other interactions [13].

Experimental Protocol for a 2^k Factorial Design

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for planning, executing, and analyzing a two-level factorial experiment, a common and powerful tool in chemical research.

Step 1: Define the Objective and Select Factors

Clearly state the research question. Identify the response variable (the measured outcome, e.g., percent yield, purity, reaction rate) and the key factors to be investigated. Select realistic low and high levels for each factor based on prior knowledge or screening experiments [13].

Step 2: Construct the Design Matrix

Create a matrix that lists all the unique experimental runs. For a 2² design, this is a table with four rows. The matrix systematically lays out the conditions for each run.

Table 2: Design Matrix for a 2² Factorial Experiment

| Standard Order | Run Order | Factor A: Temperature (°C) | Factor B: Catalyst (mol%) | Response: Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Randomized | Low (e.g., 50) | Low (e.g., 1.0) | y₁ |

| 2 | Randomized | Low (50) | High (e.g., 2.0) | y₂ |

| 3 | Randomized | High (e.g., 80) | Low (1.0) | y₃ |

| 4 | Randomized | High (80) | High (2.0) | y₄ |

Step 3: Randomize and Execute Experiments

Randomize the run order (as shown in Table 2) to protect against the influence of lurking variables and systematic errors. Perform the experiments according to the randomized schedule, carefully controlling all non-investigated parameters.

Step 4: Calculate Main and Interaction Effects

The main effect of a factor is the average change in response when that factor is moved from its low to its high level. For Factor A (Temperature): ( \text{Effect}A = \frac{(y3 + y4)}{2} - \frac{(y1 + y_2)}{2} )

The interaction effect (AB) measures whether the effect of one factor depends on the level of the other. It is calculated as half the difference between the effect of A at the high level of B and the effect of A at the low level of B [4] [14]. ( \text{Effect}{AB} = \frac{(y4 - y3)}{2} - \frac{(y2 - y1)}{2} = \frac{(y1 + y4) - (y2 + y_3)}{2} )

Step 5: Perform Statistical Analysis

Use analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the statistical significance of the calculated effects. This analysis tests whether the observed effects are larger than would be expected due to random experimental variation (noise) alone. Effects with p-values below a chosen significance level (e.g., α = 0.05) are considered statistically significant.

Interpreting Outcomes and Visualizing Effects

The results of a factorial experiment can reveal different underlying relationships between the factors and the response. These relationships are best understood through interaction plots.

Types of Experimental Outcomes

- Null Outcome: The response is the same across all combinations of factor levels. The factors have no detectable effect on the response [14].

- Main Effects Only: A factor has a consistent, independent effect on the response. For example, increasing temperature might always increase yield, regardless of the catalyst level. The lines on an interaction plot will be parallel, indicating no interaction [4] [14].

- Interaction Effects: The effect of one factor is different at different levels of another factor. For instance, a certain catalyst might be highly effective only at a high temperature. This is represented by non-parallel lines on an interaction plot [14]. A "crossover" interaction occurs when the superior level of one factor changes depending on the level of the other factor [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Success in chemical experimentation relies on the precise selection and use of high-quality materials. The following table details key reagents and their functions in a typical context, such as a catalytic reaction study, which could be investigated via factorial design.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Reaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function in Experiment | Critical Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst | Increases the rate of the chemical reaction without being consumed. The factor under investigation. | High purity, well-defined particle size and morphology (e.g., Pd/C, Zeolite). Stability under reaction conditions is critical. |

| Substrate/Reactant | The primary chemical(s) undergoing transformation. | High purity (e.g., >99%) to minimize side reactions. Concentration is often a key factor in the design. |

| Solvent | The medium in which the reaction takes place. Can influence reaction rate, mechanism, and selectivity. | Anhydrous grade if moisture-sensitive. Polarity and protic/aprotic nature can be a factor. |

| Acid/Base Additive | Modifies the reaction environment (pH), which can dramatically impact catalyst activity and selectivity. | Concentration and type (e.g., weak vs. strong acid) are potential factors. |

| Analytical Standard | A pure compound used to calibrate instrumentation (e.g., HPLC, GC) for accurate quantification of yield and purity. | Certified Reference Material (CRM) is ideal for high accuracy. |

| Internal Standard | Added in a constant amount to all analytical samples to correct for instrument variability and sample preparation errors. | Must be inert, well-resolved from other components, and similar in behavior to the analyte. |

Advanced Concepts and Experimental Workflow

For more complex systems, fractional factorial and other advanced designs (e.g., Response Surface Methodology) are employed. These designs build upon the principles of full factorial designs to efficiently explore a greater number of factors or to model curved (non-linear) response surfaces [13].

The entire process, from design to conclusion, can be summarized in a single integrated workflow.

In the field of synthetic chemistry, the optimization of chemical reactions has traditionally been dominated by the One-Variable-At-a-Time (OVAT) approach. While intuitive, this method treats variables as independent entities, requiring a minimum of three experiments per variable (high, middle, low) and systematically fails to capture interaction effects between factors such as temperature, concentration, and catalyst loading [2]. Consequently, the OVAT method often leads to erroneous conclusions about true optimal conditions and probes only a minimal fraction of the possible chemical space, resulting in suboptimal conditions and wasted resources [2].

Design of Experiments (DoE), and factorial design in particular, presents a paradigm shift. Factorial design is a structured approach that examines how various elements and their combinations influence a particular outcome [17]. By evaluating multiple factors simultaneously according to a predetermined statistical plan, DoE allows scientists to uncover the individual impacts of each element and, crucially, their interactions [2] [4]. This methodology has become a workhorse in the chemical industry due to its profound benefits, which include significant material and time savings, as well as a more profound, mechanistic understanding of chemical processes [2]. Despite these advantages, its adoption in academic settings has been slow, often perceived as complex and statistically demanding [2]. This whitepaper details these core benefits within the context of modern chemistry research and drug development.

Core Benefits of Implementing Factorial Design

Material and Cost Savings

The efficiency of factorial designs directly translates into a reduction in the number of experiments required to understand a multi-variable system, which conserves valuable reagents and materials.

- Reduced Experimental Footprint: A full factorial design with

kfactors at 2 levels contains2^kunique experiments. While this can grow with added factors, the use of fractional factorial designs allows researchers to study a large number of factors with only a fraction of the runs of a full factorial, maximizing information while minimizing resource consumption [2] [12]. For example, a fractional factorial design can screen 5 factors with just 16 or even 8 experiments, depending on the resolution required [12]. - Focused Resource Deployment: By using statistical power across the entire design to evaluate factors, DoE avoids the sequential, and often redundant, experimentation of OVAT. This means that expensive or scarce reagents are used only in a strategically chosen set of experiments, yielding the highest possible information return on investment [2]. This is particularly critical in early-stage drug development where novel compounds are available in limited quantities.

Table 1: Experimental Count Comparison: OVAT vs. Factorial Design for 4 Variables

| Optimization Method | Number of Experiments | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|

| One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) | A theoretically undefined, often large number as variables are optimized sequentially [2] | Main effects only; misses critical interaction effects between variables [2] |

| Full Factorial Design (2^4) | 16 | All main effects and all two-way, three-way, and four-way interactions [4] |

| Fractional Factorial Design (Resolution V) | 8 | All main effects and two-factor interactions are clear of other two-factor interactions [12] |

Time Reduction and Enhanced Efficiency

The streamlined experimental workflow of DoE directly accelerates research and development timelines.

- Parallel Experimentation: Unlike the sequential nature of OVAT, a factorial design is planned in advance, allowing researchers to set up and run multiple experiments in parallel. This dramatically shrinks the total calendar time needed from initial investigation to optimized conditions [2].

- Elimination of Redundant Steps: The statistical framework of DoE helps identify insignificant variables early in the optimization process. This allows chemists to shrink the variable space and focus subsequent efforts only on the factors that truly matter, avoiding wasted time on optimizing irrelevant parameters [2]. Furthermore, the ability to optimize multiple responses simultaneously (e.g., yield and enantioselectivity) in a single design eliminates the need for separate, time-consuming optimization campaigns for each response [2].

Deeper Process Understanding

Beyond resource and time savings, the most significant advantage of factorial design is the depth of process understanding it provides.

- Detection of Interaction Effects: Factorial designs are uniquely powerful for detecting and characterizing interactions, which occur when the effect of one factor depends on the level of another factor [4]. For instance, a specific catalyst might only deliver high yield at a particular temperature range, an effect completely invisible to OVAT. Capturing these interactions is critical for developing a robust and well-understood process [2].

- Systematic Modeling of Chemical Space: The data from a factorial design is used to build a mathematical model that relates the experimental factors to the response(s). This model can include main effects, interaction effects, and with more advanced designs like response surface methodologies (RSM), quadratic (curvature) effects [2]. This model provides a comprehensive map of the chemical space, revealing not just a single optimum but a functional understanding of how the system behaves across a wide range of conditions [2].

- Informed Risk Mitigation: With a model that captures interactions and nonlinear effects, scientists can make better predictions about process performance and identify regions of operational space that are robust to small, unavoidable variations in factor settings (e.g., slight temperature fluctuations). This is foundational for developing scalable and reliable manufacturing processes in the pharmaceutical industry [18].

Quantitative Performance of Different Factorial Designs

The choice of factorial design can influence the effectiveness of an optimization campaign. A recent large-scale simulation study evaluated over 150 different factorial designs for multi-objective optimization, providing quantitative performance insights.

Table 2: Performance of Different Factorial Designs in Complex System Optimization

| Design of Experiments Type | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance & Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Central-Composite Design (CCD) | Includes factorial points, axial points, and center points to model curvature [18]. | Best overall performance for optimizing complex systems; recommended when resources allow for a comprehensive model [18]. |

| Full / Fractional Factorial | Screens main effects and interactions efficiently; resolution determines clarity of effects [12]. | Ideal for initial screening to identify vital factors; higher resolution (e.g., Resolution V) is preferred to avoid confounding interactions [18] [12]. |

| Taguchi Design | Efficiently handles categorical factors with many levels [18]. | Effective for identifying optimal levels of categorical factors but found to be less reliable overall than CCD for final optimization [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Implementation

Implementing a successful DoE study in synthetic chemistry involves a logical sequence of steps. The following workflow and detailed protocol provide a roadmap for researchers.

Step-by-Step Detailed Methodology

- Define Objective and Responses: The first step is to determine the key outcome(s) or response(s) to be optimized. In synthetic method development, this is typically chemical yield and/or selectivity factors (e.g., enantiomeric excess, diastereomeric ratio) [2]. A major benefit of DoE is the ability to optimize multiple responses systematically within a single framework [2].

- Select Factors and Ranges: Identify all independent variables (factors) that may influence the reaction. Common factors in synthesis include temperature, catalyst loading, ligand stoichiometry, concentration, and reaction time [2]. For each factor, define feasible upper and lower limits based on chemical knowledge and practical constraints (e.g., solvent boiling point). The choice of range is critical, as ranges that are too narrow may miss an optimum, while overly broad ranges could lead to uninformative failed reactions [2].

- Choose an Experimental Design: Select a design type that aligns with the study's goal.

- Screening: For evaluating many factors to identify the most important ones, use a Fractional Factorial Design (e.g., Resolution V to clearly estimate main effects and two-factor interactions) [12].

- Optimization: For finding the precise optimum of a smaller number of vital factors, use a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like a Central-Composite Design (CCD), which can model curvature [2] [18].

- Incorporating Center Points: Adding replicate experiments at the center point of the design allows for checking for curvature and provides an estimate of pure experimental error [12].

- Execute Experiments and Analyze Data: Perform the experiments as specified by the design matrix, ensuring randomization to avoid confounding from lurking variables. Analyze the data using statistical software to fit a model, typically a linear model for screening designs or a quadratic model for RSM. The software output will include ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) tables to identify statistically significant effects and interaction plots to visualize how factors influence each other [2] [12].

- Validate Optimal Conditions: The model will predict one or more sets of factor settings that should optimize the responses. It is essential to run confirmation experiments at these predicted optimal conditions to verify the model's accuracy and ensure the process performs as expected in the lab [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successfully applying factorial design requires both laboratory materials and specialized software tools.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Software for DoE Implementation

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Names | Function & Application in DoE |

|---|---|---|

| Common Reaction Factors | Temperature, Catalyst Loading, Ligand Stoichiometry, Concentration, Solvent [2] | The independent variables whose effects on yield or selectivity are systematically explored in the experimental design. |

| Statistical Software | Design-Expert, JMP, Minitab, Stat-Ease 360 [19] [17] | Provides a user-friendly interface to generate design matrices, analyze response data, fit mathematical models, create visualizations (contour/3D plots), and find optimal conditions via multi-response optimization [19] [17]. |

| Advanced AI Tools | Quantum Boost [17] | Utilizes AI to further reduce the number of experiments required to reach an optimization objective, building on classical DoE principles [17]. |

Advanced Visualization and Data Interpretation

Effective interpretation of factorial design results relies heavily on statistical graphics that transform data into actionable insights.

- Interaction Plots: These plots are fundamental for visualizing interaction effects. When two lines on the plot are non-parallel, it indicates a potential interaction, meaning the effect of one factor depends on the level of another [4].

- Response Surface and Contour Plots: For optimizations involving RSM, 3D surface plots and their corresponding 2D contour plots provide a visual map of the response across the experimental region. These plots make it easy to locate optimum conditions (peaks or valleys on the surface) and understand the shape of the response, such as the presence of a ridge or a saddle point [19].

- Pareto Charts and Half-Normal Plots: These charts are used in the analysis of screening designs to quickly identify which factors have statistically significant effects on the response, helping to separate the vital few factors from the trivial many [12].

The adoption of factorial design represents a significant leap forward from traditional OVAT optimization. The documented benefits are substantial: a drastic reduction in the number of experiments leads to direct material cost-savings and time-savings in experimental setup and analysis. More importantly, the methodology provides a complete understanding of variable effects and their interactions, offering a systematic and robust approach to optimizing complex chemical systems with multiple, sometimes competing, objectives [2]. As the field of chemoinformatics continues to evolve, the ability of synthetic chemists to interface with and utilize these predictive models and computer-assisted designs will become increasingly critical for accelerating research, particularly in demanding fields like drug development [2].

Implementing Factorial Design: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Chemical and Pharmaceutical Applications

In the realm of chemical synthesis and process development, the initial and most critical step is the precise definition of the optimization goal. This decision fundamentally guides all subsequent experimental design, data analysis, and resource allocation. Historically, chemists relied on empirical, one-variable-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, which are inefficient and often fail to capture complex interactions between parameters [20]. The adoption of structured experimental design, particularly factorial design, represents a paradigm shift towards a more systematic and efficient research methodology [12] [4]. Factorial designs allow researchers to simultaneously investigate the effects of multiple factors (e.g., temperature, concentration, catalyst type) and their interactions on one or more response variables [4]. This guide, situated within a broader thesis on introducing factorial design to chemistry research, will dissect the four primary optimization goals in chemical synthesis—yield, selectivity, purity, and stability—detailing their definitions, interrelationships, measurement protocols, and how they serve as the foundational responses in a designed experiment.

Core Optimization Goals: Definitions and Quantitative Benchmarks

Each optimization goal represents a distinct dimension of reaction performance. The target is often defined by the specific application, such as maximizing yield for a bulk chemical intermediate or prioritizing selectivity for a complex pharmaceutical molecule with multiple stereocenters.

Table 1: Core Optimization Goals in Chemical Synthesis

| Goal | Definition | Key Metric(s) | Typical Target Range (Varies by Application) | Primary Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | The amount of target product formed relative to the theoretical maximum amount, based on the limiting reactant. | Percentage Yield, Space-Time Yield (STY) [20] | Process Chemistry: >90%; Discovery/Complex Molecules: >50% | NMR, GC, HPLC with internal standard |

| Selectivity | The preference of a reaction to form one desired product over other possible by-products (e.g., regioisomers, enantiomers). | Selectivity (%) , Enantiomeric Excess (e.e.), Diastereomeric Ratio (d.r.) | API Synthesis: Often >99% e.e.; Fine Chemicals: >90% selectivity | Chiral HPLC/GC, NMR, LC-MS |

| Purity | The proportion of the desired compound in a sample relative to all other components (impurities, solvents, residual catalysts). | Area Percentage (HPLC/GC), Weight Percent | Final API: >99.0%; Intermediate: >95.0% | HPLC, GC, NMR, Elemental Analysis |

| Stability | The ability of the product or reaction system to maintain its chemical integrity and performance over time or under specific conditions. | Degradation Rate, Shelf-life, Turnover Frequency (TOF) / Number (TON) for catalysts [21] | Catalyst: TON >10,000; Drug Substance: Shelf-life >24 months | Forced Degradation Studies, Accelerated Stability Testing, Recyclability Tests [21] |

Interrelationships and Trade-offs: A Multi-Objective Perspective

These goals are frequently interdependent and can involve significant trade-offs. For instance, conditions that maximize yield (e.g., higher temperature, longer time) may promote side reactions, reducing selectivity and purity [20]. A factorial design is exceptionally powerful for mapping these complex trade-offs. By running a structured set of experiments varying multiple factors, researchers can build a statistical model that reveals how factors influence each goal and identify a "sweet spot" or Pareto frontier that balances multiple objectives [20]. For example, a study optimizing a catalytic hydrogenation might use a factorial design to understand how temperature and pressure affect both yield and selectivity, ultimately finding conditions that give a 95% yield with 99% selectivity, rather than 98% yield with only 90% selectivity.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Measurement

Accurate quantification of these goals is non-negotiable. Below are generalized protocols for key measurement techniques referenced in the search results.

Protocol A: Quantifying Yield and Selectivity via Quantitative NMR (qNMR)

- Internal Standard Preparation: Precisely weigh a known amount of a chemically inert, pure compound (e.g., 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene) that has a non-overlapping NMR signal with your reaction mixture.

- Sample Preparation: Combine a precise aliquot of your crude or purified reaction mixture with the internal standard in an NMR tube using a deuterated solvent.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a standard ¹H NMR spectrum with sufficient relaxation delay (e.g., 5 x T1) to ensure quantitative integration [22].

- Calculation:

- Yield:

Yield (%) = [(I_product / N_product) / (I_standard / N_standard)] * (MW_product / MW_standard) * (mass_standard / mass_limiting_reagent) * 100%(WhereI= integral,N= number of protons giving the signal,MW= molecular weight). - Selectivity: Compare integrals of signals corresponding to the desired product versus isomeric by-products.

- Yield:

Protocol B: Assessing Catalytic Stability via Turnover Frequency (TOF) Measurement Adapted from photochemical stability assessment in solid-state catalysis [21].

- Reaction Setup: Conduct the model reaction (e.g., nitroarene hydrogenation) under standardized conditions (catalyst loading, substrate concentration, light intensity, temperature).

- Initial Rate Measurement: Use an inline analytical method (e.g., GC) to track product formation within the first few minutes of the reaction, ensuring conversion is low (<10%) to measure initial kinetics.

- TOF Calculation:

TOF (h⁻¹) = (moles of product formed) / (moles of catalytic sites * reaction time in hours). - Recyclability Test: Upon reaction completion, recover the catalyst (e.g., by filtration for solid catalysts [21]), wash, and dry. Re-use the catalyst in a fresh batch of reactants under identical conditions. Repeat for multiple cycles while monitoring yield or TOF to assess stability loss.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization Studies

| Item/Reagent | Function/Explanation | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Nanocluster Catalyst (e.g., 12R-Pd-NCs) | Drives photoactivated solid-state reactions; its asymmetric defect structure enhances visible light absorption for efficient, selective transformations under mild conditions [21]. | Custom synthesis as described for solid-state amine synthesis [21]. |

| Deuterated NMR Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | Essential for qNMR analysis, providing a lock signal for the spectrometer and avoiding interfering proton signals from the solvent [22]. | Commercial suppliers. |

| Internal Standards for qNMR | Provides a reference for absolute quantification of product concentration in complex mixtures [22]. | 1,3,5-Trimethoxybenzene, maleic acid. |

| Chiral HPLC/GC Columns | Critical for separating and quantifying enantiomers to measure enantioselectivity (e.e.) [22]. | Polysaccharide-based (e.g., Chiralcel OD-H), cyclodextrin-based columns. |

| Chemical & Products Database (CPDat) | A public database aggregating chemical use and product composition data; useful for identifying safer solvents or chemicals with known functional roles during condition scoping [23]. | U.S. EPA CPDat v4.0 [23]. |

| Spectroscopic Databases (e.g., SDBS, Aldrich Library) | Reference libraries for comparing and identifying spectral data (NMR, IR, MS), crucial for verifying product purity and identity [22]. | Spectral Database for Organic Compounds (SDBS) [22]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Facilitates the generation and statistical analysis of factorial and response surface designs, turning experimental data into predictive models [12]. | Tools like Design-Expert, JMP. |

Visualizing the Optimization Framework within Factorial Design

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical flow from goal definition through experimental optimization.

Diagram 1: From Goals to Factorial Design (97 chars)

Diagram 2: Automated Experiment-Optimization Cycle (99 chars)

In conclusion, clearly defining yield, selectivity, purity, and stability is the indispensable first step in any chemical development project. By integrating these defined metrics as responses within a factorial design framework, researchers can move beyond intuitive guessing to a data-driven exploration of the chemical parameter space. This approach, now frequently enhanced by machine learning algorithms like Bayesian optimization [24] [20], systematically uncovers complex factor interactions and Pareto-optimal solutions, ultimately accelerating the development of efficient, selective, and sustainable chemical processes.

Within the structured framework of a factorial design for chemistry research, the selection of critical factors and the definition of their experimental ranges constitute the most pivotal strategic decision. A factorial design investigates how multiple factors simultaneously influence a specific response variable, such as chemical yield, purity, or reaction rate [5]. Unlike inefficient one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, factorial designs allow for the efficient estimation of both main effects and crucial interaction effects between factors [25] [26]. The power and efficiency of any factorial experiment—be it a full factorial or a fractional factorial design—are fundamentally constrained by the choices made in this step [10]. Selecting too many factors leads to prohibitively large experiments, while choosing too few may omit key variables. Similarly, ranges that are too narrow may miss detectable effects, and ranges that are too broad may be unsafe or produce unreliable models [12]. This guide provides a detailed methodology for making these critical choices, forming the core of a practical experimental plan.

Methodology for Selecting Critical Factors

The process of factor selection is iterative and should be driven by both fundamental chemical knowledge and practical experimental constraints.

Source and Categorization of Potential Factors

Begin by brainstorming all variables that could plausibly affect the response of interest. These typically fall into two categories:

- Quantitative Factors: Variables expressed on a numerical scale (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration, pressure, time, flow rate).

- Qualitative Factors: Variables representing distinct categories (e.g., type of catalyst, solvent identity, source of raw material, equipment model).

For a screening experiment, it is common to start with a list of 4-7 potential factors [12]. In drug development, this could include parameters like reaction temperature, catalyst loading, solvent polarity, and stoichiometric ratio.

Criteria for Selecting "Critical" Factors

Not all potential factors are equally worthy of inclusion in a designed experiment. Apply the following filters to identify the critical ones:

- Relevance to Research Objective: Does prior knowledge (literature, mechanistic understanding, preliminary data) strongly suggest the factor influences the response?

- Controllability: Can the factor be set and maintained at a specific level with acceptable precision during the experiment?

- Potential for Interaction: Is there a scientific hypothesis that the effect of this factor depends on the level of another (e.g., the optimal temperature may depend on the solvent used)? Factorial designs are uniquely powerful for detecting such interactions [5] [25].

- Practical and Economic Constraints: What is the cost or difficulty of varying the factor? The goal is to gain maximum information with a manageable number of experimental runs [10].

Systematic Screening for High-Throughput Selection

When the list of potential factors is large (>5), a two-stage approach is recommended. First, use a highly fractionated factorial design (e.g., a Resolution III Plackett-Burman design) or other screening design to identify which factors have a significant main effect [10] [12]. Subsequently, these critical few factors can be investigated in greater detail, including their interactions, in a higher-resolution design (e.g., a full factorial or Resolution V fractional factorial) [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical decision process for factor selection:

Protocol for Setting Realistic and Informative Ranges (Levels)

Once critical factors are selected, defining their "low" and "high" levels (in a two-level design) is crucial. The levels should be spaced far enough apart to elicit a measurable change in the response, yet remain within safe and operable limits.

Principles for Quantitative Factors

- Base on Process Knowledge: The range should span the region of operational interest. For example, if a reaction is typically run between 20°C and 60°C, these might be chosen as the low and high levels.

- Avoid Extreme Conditions: Ranges should not extend to regions where side reactions dominate, equipment fails, or safety is compromised.

- Consider Linearity Assumption: Standard 2-level factorial designs assume a linear effect of the factor across the chosen range. If strong curvature is suspected, the inclusion of center points is essential to detect it [25] [12].

- Document Justification: The rationale for each range (e.g., "solubility limit at 0.5M", "catalyst deactivation above 80°C") must be recorded.

Defining Levels for Qualitative Factors

For qualitative factors (e.g., Solvent A vs. Solvent B), the "levels" are simply the distinct categories to be compared. The choice should represent meaningful alternatives (e.g., polar protic vs. polar aprotic solvent).

Quantitative Data Reference Table

The table below summarizes typical factors and realistic ranges in chemical and pharmaceutical development contexts, synthesized from common experimental practices.