Combatting Evaporation in Microtiter Plates: A Complete Guide for Reliable High-Throughput Screening

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of evaporation in microtiter plate-based assays.

Combatting Evaporation in Microtiter Plates: A Complete Guide for Reliable High-Throughput Screening

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on addressing the critical challenge of evaporation in microtiter plate-based assays. It covers the foundational science behind evaporation and its detrimental effects on data integrity, explores a range of practical containment and environmental control methods, offers advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies to combat the 'edge effect,' and presents validation techniques and comparative analyses of solutions to ensure scalable and reproducible results in biomedical research.

Understanding the Evaporation Problem: How Microplate Evaporation Compromises Data Integrity

Evaporation is a critical, yet often overlooked, challenge in laboratories that use microtiter plates. For researchers in drug development and cell-based assays, uncontrolled evaporation compromises data integrity, reduces reproducibility, and can lead to costly experimental failures. This guide details why small volumes are particularly vulnerable and provides actionable strategies to mitigate these risks in your work.

FAQs: Understanding Evaporation in Microtiter Plates

Why is evaporation a particularly critical issue for small-volume cultures?

Evaporation is critical in small-volume cultures because the loss of even a minute amount of liquid leads to significant changes in the composition of the culture medium. This is especially true for long cultivation periods or when working with microtiter plates [1]. The consequences include [1] [2]:

- Increase in osmolarity, creating a stressful environment for cells.

- Higher concentrations of salts and ions, which can become toxic.

- Changes to oxygen solubility, altering the fundamental conditions for cell growth.

- Increased viscosity, which can affect fluid dynamics and assay readings. Critically, evaporation rates are often inconsistent across a microtiter plate, with higher losses typically occurring in the perimeter wells, a phenomenon known as the "edge effect" [2] [3]. This variation compromises the statistical validity of screening processes and Design of Experiment (DoE) studies, as the conditions in each well are no longer comparable [1].

What is the "edge effect" and how can I prevent it?

The "edge effect" is the phenomenon where the wells around the perimeter of a microtiter plate experience higher rates of evaporation compared to the inner wells. This results in varying volumes, solute concentrations, and evaporation rates across the plate, which can alter cell viability and skew assay results [2].

Prevention Strategies:

- Humidification: Maintain at least 95% humidity within the incubator to minimize the driving force for evaporation [2].

- Workflow Efficiency: Limit the number of times and the duration for which the incubator door is opened to maintain a stable environment [2].

- Physical Barriers: Use microplates specifically designed with a moat surrounding the outer wells. This moat can be filled with a sterile liquid to act as a buffer zone, effectively reducing the edge effect [2].

- Specialized Seals: Employ advanced sealing solutions, such as self-closing slit seals, which are designed to prevent evaporation without the use of adhesives, thereby reducing contamination risk [4].

How can I accurately measure and compensate for evaporation in long-term cultures?

For long-term fed-batch cultures, it is necessary to quantitatively measure and actively compensate for evaporated liquid to maintain consistent conditions. One established method uses the concentration of sodium ions (Na+) as an evaporation marker [3].

Experimental Protocol: Using Sodium Ion Concentration to Measure Evaporation

Principle: The concentration of Na+ correlates strongly with liquid volume loss because it is not consumed by cells in significant amounts during culture. A correlation between evaporation and the concentration of Na+ was found (R² = 0.95) in a batch culture with GS-CHO cells [3].

Procedure:

- Measure Initial Conditions: Determine the initial liquid volume (V₀) and the initial sodium ion concentration ([Na]₀) in your culture medium.

- Monitor During Culture: At designated time points, take samples from the culture and measure the current sodium ion concentration ([Na]t) using an analyzer like a Bioprofile FLEX [3].

- Calculate Evaporated Volume: Use the following formula to calculate the volume of liquid that has evaporated (V_Evap) [3]: VEvap = V₀ - ( V₀ · [Na]₀ / [Na]t )

- Compensate: Based on the calculated V_Evap, add an appropriate volume of sterile distilled water to the culture to restore the original working volume and concentration. Implementation of this method in a fed-batch cultivation reduced relative liquid loss after 15 days from 36.7% without corrections to 6.9% with corrections [3].

What are the different types of humidification systems for incubator shakers?

Humidification systems work by increasing the humidity inside the incubation chamber, which reduces the rate of evaporation from your cultures. The main types are summarized in the table below [1]:

| System Type | How It Works | Relative Humidity | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Water Bath | A free-standing container of water placed in the chamber adds moisture through evaporation. | Uncontrolled | Low cost; quickly set up. | High risk of contamination (mold); condensation is likely; no control [1]. |

| Direct Steam Humidification | Water droplets are flash-vaporized in a hot pod and steam is released into the chamber. | Controlled increase up to ~85% | Hygienic (no open water); conditions are reproducible and loggable; reduces condensation with a heated door [1]. | One-sided control (can only add humidity) [1]. |

| Bidirectional Humidity Control | Can add humidity via steam or remove it by blowing in dry, filtered air. | Precise control over a broad range | "Gold standard"; ensures condensation-free operation even at low temperatures; highly reproducible [1]. | High-end system [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Evaporation and Edge Effect in Microtiter Plates

Symptoms:

- Noticeable decrease in liquid volume, especially in outer wells.

- Increased variability in assay results between inner and outer wells.

- Crystallization or increased viscosity of media in perimeter wells.

Solutions:

- Verify Incubator Humidity: Check and calibrate your incubator's humidity control system. Ensure humidity is maintained at ≥95% [2].

- Use a Sealing Solution: Replace standard lids or seals with anti-evaporation seals. RAPID Slit Seal is a gamma-sterilized, self-closing seal that prevents evaporation even after being punctured by autosamplers or pipette tips, without using adhesive [4].

- Employ a Protective Barrier: Place microtiter plates inside a sealed box with a hydrated atmosphere or use a specialized microplate box with an air filter to create a protected microenvironment [1].

- Upgrade Your Hardware: If your research heavily relies on small-volume, long-duration shakes, consider upgrading to an incubator shaker with bidirectional humidity control for the most precise and reproducible environmental control [1].

Problem: Inconsistent Cell Growth and Productivity in Small Volumes

Symptoms:

- Cell growth is inhibited or stops prematurely.

- Protein or metabolite productivity is lower than expected.

- High and variable osmolarity readings in culture samples.

Solutions:

- Monitor Electrolytes: Implement the sodium ion method described above to quantitatively track evaporation and make corrective water additions [3].

- Review Shaking Parameters: Evaluate if the shaking speed is too high, which can increase air flow and evaporation. Test if a slightly reduced speed (within an acceptable range for oxygenation) mitigates volume loss without affecting cell growth [3].

- Assess Sealing Mats: If using adhesive seals, ensure they are applied correctly and are designed for minimal evaporation. Consider that traditional seals may not be as effective as newer self-closing technologies [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent & Material Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Bidirectional Humidity Incubator Shaker | Provides precise control over chamber humidity, both adding and removing moisture to maintain a setpoint and prevent condensation [1]. |

| RAPID Slit Seal | A self-closing, reusable seal that prevents evaporation even after repeated puncturing, eliminating the need for adhesives and reducing contamination risk [4]. |

| Nunc Edge Well Plate | A specialized microplate with a built-in moat around the outer wells that can be filled with liquid to create a buffer zone against evaporation, directly combating the edge effect [2]. |

| Sodium Ion Analyzer | An instrument (e.g., Bioprofile FLEX) used to measure sodium ion concentration in culture medium, enabling the indirect calculation of evaporated volume [3]. |

| Microtiter Plate Box | A sealed container that holds the microplate, creating a separate humidified chamber to minimize evaporation without a full incubator humidification system [1]. |

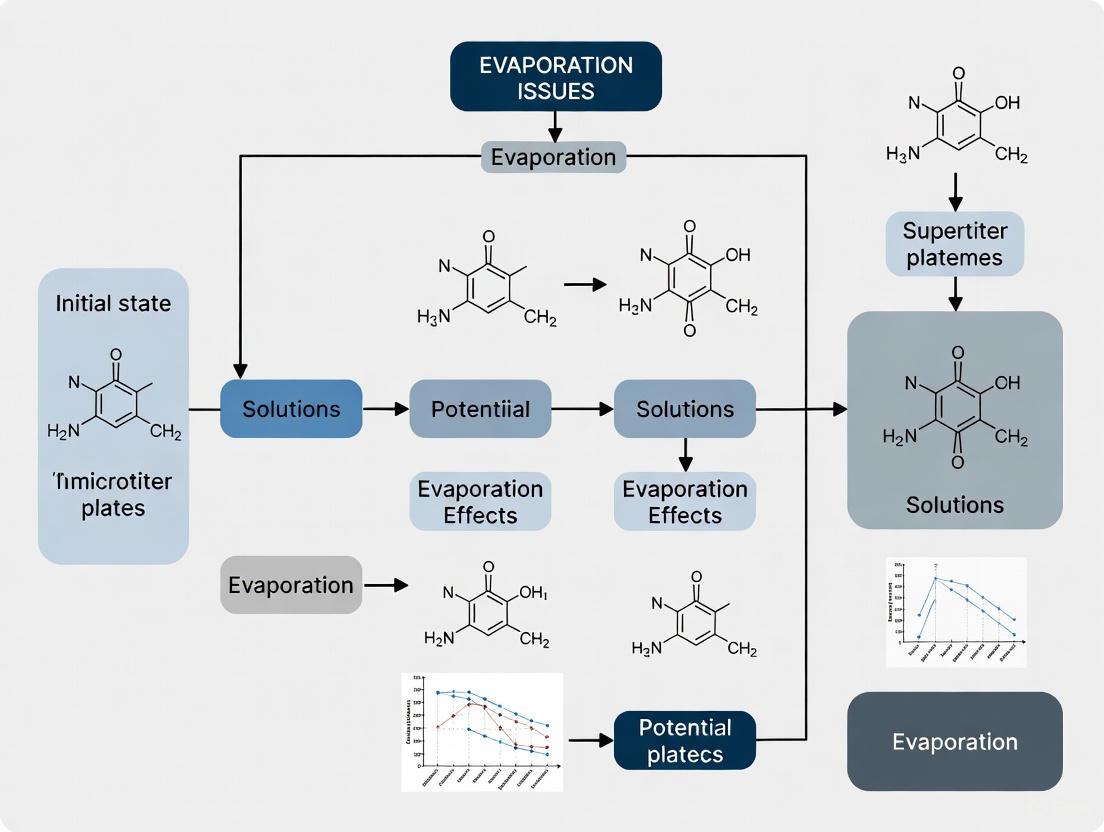

Experimental Workflows for Evaporation Management

The following diagrams outline logical workflows for preventing evaporation and for measuring it quantitatively when prevention alone is insufficient.

Workflow for Preventing Evaporation

Workflow for Measuring and Correcting Evaporation

Troubleshooting Guide: Evaporation-Related Issues

FAQ: Why do the perimeter wells of my microtiter plate show different activity than interior wells? This common issue, known as the "edge effect," occurs because perimeter wells are not completely surrounded by other wells, leading to different thermal conditions and increased evaporation rates. This evaporation concentrates solutes and increases osmolarity in outer wells, which can significantly impact cellular processes and lead to inconsistent data across the plate. [5]

FAQ: How does evaporation physically affect my assay reagents? Evaporation causes volume loss, which leads to two primary effects:

- Increased solute concentration: As the aqueous solvent evaporates, all dissolved compounds become more concentrated.

- Increased osmolarity: The higher concentration of solutes increases the osmotic pressure of the solution. [6] For sensitive biological systems like mouse embryonic cells, an osmolarity shift of just 5% can modify development and even lead to cell death. [6] [7]

FAQ: What temperature-related artifacts should I watch for in cell-based assays? Temperature differences throughout a screening campaign can introduce artifacts. Incubator-induced artifacts and variations in cell-plating conditions during room temperature incubation can affect assay consistency. These thermal variations compound evaporation effects, particularly in automated high-throughput systems. [8]

Quantitative Impact Data

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Evaporation on Biological Systems

| Biological System | Parameter Measured | Impact Level | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Embryonic Cells [6] [7] | Osmolarity Shift | >5% causes modified growth/cell death | Development studies |

| Microbial Growth [9] | Optimal Growth Osmolality | 1.0–1.6 Osmol/kg | Vibrio natriegens cultivation |

| Passive Pumping Microchannel [6] | Evaporation-Induced Flow Rate | Rivals diffusive transport | Microfluidic cell culture |

Table 2: Effective Evaporation Control Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Humidity Environment [6] [7] | Reduces vapor pressure gradient | Long-term cell culture | Can lead to condensation |

| Plate Sealing Films [10] [11] | Creates physical vapor barrier | High-throughput screening | Requires optical clarity for detection |

| Oil Overlay (e.g., Paraffin) [10] | Blocks air-liquid interface | Small volumes in well plates | Incompatible with COP/COC plates |

| Perimeter Well Buffer [5] | Sacrificial evaporation sources | Critical concentration assays | Reduces available test wells |

| Robust pH Buffering [9] | Counters acidification from concentration | Bacterial cultures with overflow metabolism | e.g., 300mM MOPS at pH 8.0 |

Experimental Protocols for Evaporation Control

Protocol: Establishing a Humidified Environment for Long-Term Assays

Background: Creating a humidified chamber is among the least invasive methods to control evaporation, as it minimizes direct interaction with the fluid of interest. [7]

Materials:

- Sealed container (e.g., Omnitray)

- Sacrificial water reservoirs

- Humidity sensor (optional)

Method:

- Place sacrificial water around the microtiter plate within a closed container.

- The total evaporation rate in the chamber is the sum of evaporation from all sources. The fraction of liquid lost from your assay wells depends on the ratio of their evaporation surface area to the total evaporation surface area of all water sources. [7]

- For a sealed, homogeneous chamber, the initial evaporation required to saturate the air can be calculated as Vloss = ΔCsat-i × Vair / ρwater. [7]

- Equilibrium is typically reached quickly (e.g., 15 minutes in a 90mL container with one hundred 10μL drops at 25°C). [7]

Protocol: Optimizing Mineral Media for Bacterial Culture in Small Scale

Background: Mineral media designed for fermenters with pH regulation often perform poorly in unregulated small-scale cultivations. This protocol optimizes conditions for Vibrio natriegens but principles apply broadly. [9]

Materials:

- MOPS buffer

- Sodium chloride

- Glucose carbon source

Method:

- pH Buffering: Use a minimum of 300mM MOPS buffer for media containing 20g/L glucose at an initial pH of 8.0. For lower glucose (10g/L), 180mM MOPS is sufficient. [9]

- Sodium Concentration: Supplement with 7.5–15g/L sodium chloride, lower than traditionally recommended ranges, to reduce industrial corrosion issues. [9]

- Osmolality Control: Maintain osmolality between 1.0–1.6 Osmol/kg for optimal growth. [9]

- Validation: Under these optimized conditions, V. natriegens achieved a growth rate of 1.97 ± 0.13 1/h at 37°C, the highest reported rate for this organism on mineral medium. [9]

Evaporation Mechanisms and Mitigation Workflow

Evaporation Causes and Mitigation Pathways

Experimental Setup for Humidity Control

Humidity Control Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Evaporation and Osmolarity Management

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| MOPS Buffer [9] | Maintains pH under acidification from metabolic by-products | Bacterial cultures with glucose overflow metabolism that produces acetate |

| Sodium Chloride [9] | Provides essential sodium ions for halophilic organisms | Marine bacterial cultures like Vibrio natriegens |

| Paraffin Oil [10] | Forms protective overlay to prevent evaporation | Plate reader applications requiring long measurement times |

| Polyolefin Sealing Tape [10] | Optically clear adhesive seal for microplates | qPCR and fluorescence-based assays requiring thermal cycling |

| Glycerol [7] | Reduces vapor pressure of aqueous solutions | Long-term storage of sensitive biological samples |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) [12] | Solvent for compounds with low aqueous solubility | Preparation of Traditional Chinese Medicine monomer stock solutions |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the edge effect in microplate assays?

The edge effect is a phenomenon where wells located at the perimeter of a microplate (such as 96-well, 384-well, or 1536-well plates) yield different results compared to wells in the center. This occurs due to variations in the micro-environment across the plate, primarily caused by increased evaporation in the outer wells. This leads to changes in reagent concentration, osmolarity, pH, and ultimately affects cell metabolism, viability, and assay readouts [13] [14]. The effect can cause greater standard deviations, compromise data reliability, and even lead to assay failure [13].

What are the primary causes of the edge effect?

The main causes are evaporation and thermal gradients.

- Evaporation: Outer wells are more exposed, leading to a higher rate of solvent evaporation than in the insulated center wells. This is more pronounced in assays with long incubation times and in plates with a higher number of wells (like 384 or 1536) due to their lower sample volumes [13] [15].

- Thermal Gradients: Temperature inconsistencies across a microplate during incubation can create an edge effect, particularly in temperature-sensitive assays [13].

How does the edge effect impact cell-based assays?

The edge effect can significantly alter the outcomes of cell-based assays. Evaporation from outer wells leads to:

- Increased concentration of salts and media components, altering osmolarity [15].

- Shifts in pH, which can affect gene and protein expression [16].

- Reduced cell metabolic activity and growth. Studies have shown reductions of over 35% in metabolic activity in outer wells compared to central wells [14] [17]. These inconsistencies result in poor well-to-well uniformity, negatively impacting the reproducibility of downstream applications like ELISA, PCR, and Western blots [16].

Can using a specific brand of microplate reduce the edge effect?

Yes, the brand and design of the microplate can significantly influence the severity of the edge effect. Independent research has demonstrated that different manufacturers' plates show different levels of evaporation and well-to-well homogeneity. For example, one study found that Greiner plates showed better homogeneity (16% reduction in outer wells) compared to VWR plates (35% reduction) under the same conditions [14] [17]. Some manufacturers also produce plates with specialized designs, such as built-in moats to hold a buffer liquid around the outer wells, to mitigate the effect [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies to Reduce the Edge Effect

The following table summarizes the most effective strategies to minimize or eliminate the edge effect in your experiments.

| Strategy | Description | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Use Sealing Materials | Apply a low-evaporation lid, breathable sterile tape (for cell culture), or foil sealing tape (for biochemical assays) to create a physical barrier against evaporation [13] [15]. | All assay types, especially long-term incubations. |

| Hydrate Outer Wells | Fill the outer perimeter wells with a sterile liquid like water, PBS, or culture media (without cells) to create a humidified buffer zone [18] [2]. | Cell-based and biochemical assays. |

| Optimize Incubation Conditions | Maintain high incubator humidity (≥95%), limit door openings, and avoid stacking plates to ensure stable temperature and humidity [18] [2]. | Cell culture assays. |

| Select Specialized Plates | Use plates specifically designed to combat evaporation, such as those with a "moat" for buffer or advanced lid designs that ensure uniform gas and temperature flow [2] [16]. | Labs frequently running sensitive or long-term assays. |

| Reduce Assay Time | Shorten the total assay duration to limit the time available for evaporation to occur [13] [15]. | Assays where runtime can be optimized. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Impact on Cell Metabolic Activity

The following table summarizes data from a study investigating the edge effect on SW480 colorectal cancer cells cultured for 72 hours in different 96-well plates. Metabolic activity was measured using an MTS assay [14] [17].

| Well Location | VWR Plate (Reduction vs. Center) | Greiner Plate (Reduction vs. Center) |

|---|---|---|

| Corner Wells | 34% ± 2% [14] | 26% ± 4% [14] |

| Outer Row | 35% ± 3% [14] | 16% ± 8% [14] |

| 2nd Row | 25% ± 5% [14] | 7% ± 7% [14] |

| 3rd Row | 10% ± 5% [14] | 1% ± 6% [14] |

| Center Wells | Baseline (0%) | Baseline (0%) |

Protocol: Testing Edge Effect Mitigation by Adding Buffer Between Wells

This protocol is adapted from a published study that successfully improved well homogeneity [14].

Objective: To determine if adding a liquid buffer between wells reduces evaporation and the edge effect.

Materials:

- Greiner 96-well plate (or another brand with depressions between wells) [14]

- Sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or water

- Cell culture media and cell line of interest

- Multichannel pipette

Method:

- Seed Cells: Seed your cells into the 96-well plate according to your standard experimental protocol.

- Add Buffer: Using a multichannel pipette, carefully fill the spaces between all wells of the plate with sterile PBS. Take care to avoid contamination of the cell-containing wells.

- Incubate and Measure: Incubate the plate under normal conditions for your assay. Proceed with your desired endpoint measurement (e.g., MTS assay, absorbance reading).

- Data Analysis: Compare the data from the outer, second, and third rows of wells to the central wells. The study showed that this method yielded no statistically significant reduction in growth for corner and outer wells, effectively eliminating the edge effect [14].

Causation Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence of how the edge effect arises and its ultimate consequences on experimental data.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents used to study and mitigate the edge effect, as cited in experimental research.

| Item | Function in Context | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Breathable Sealing Tape | Allows gas exchange while reducing evaporation; essential for long-term cell culture [13]. | Sealing a 96-well plate during a 72-hour cell incubation [13] [15]. |

| Low-Evaporation Lid | Specially designed lids that minimize vapor loss while permitting gas exchange [13] [16]. | Used in incubations for both cell-based and biochemical assays to maintain well humidity [13]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | A sterile, isotonic buffer used to hydrate the outer wells or spaces between wells without affecting cell growth [14] [18]. | Creating a humidified buffer zone around the experimental wells to minimize evaporation gradients [14]. |

| Nunc Edge Plate | A specialized microplate with a built-in moat surrounding the outer wells that can be filled with liquid [2]. | Providing a simple and effective physical barrier against evaporation for sensitive assays [2]. |

| MTS Assay Reagent | A colorimetric method to measure cell metabolic activity and proliferation [14]. | Quantifying the reduction in metabolic activity in edge wells compared to center wells [14] [17]. |

Consequences for Reproducibility and Scalability in High-Throughput Screening

In high-throughput screening (HTS), the ability to generate reproducible and scalable data is paramount for successful drug discovery and research. A critical, yet often overlooked, challenge that directly undermines these goals is evaporation in microtiter plates. This technical guide addresses how evaporation-induced effects compromise results and provides actionable troubleshooting protocols to enhance data quality.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Evaporation and Its Consequences

FAQ 1: How does evaporation in microtiter plates lead to the "edge effect," and what impact does this have on my screening results?

Evaporation in microtiter plates causes the "edge effect," a phenomenon where the outer perimeter wells of a plate experience a higher rate of evaporation than the central wells [2] [15]. This occurs because the edge wells are less insulated [15].

The consequences for your data are significant [2]:

- Altered Assay Conditions: Evaporation increases the concentration of salts, ions, and reagents in the remaining medium, leading to changes in osmolarity, oxygen solubility, and medium viscosity [1].

- Reduced Cell Viability: In cell-based assays, these changes in the local environment can cause a drop in cell health and viability [15].

- Increased Data Variability: The gradient of conditions from the center to the edge of the plate causes uneven assay performance. This increases the Coefficient of Variation (CV) values and severely impacts assay robustness (Z-factor), potentially leading to false positives/negatives and failed assays [15].

FAQ 2: What are the most effective strategies to minimize evaporation and the edge effect in my assays?

A multi-pronged approach is the most effective way to combat evaporation. The following table summarizes the core strategies:

Table 1: Strategies to Minimize Evaporation and the Edge Effect

| Strategy | Description | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Humidification [1] | Actively control humidity within the incubator (e.g., using direct steam or bidirectional systems) to maintain levels at or above 95% relative humidity (rH). | Directly addresses the root cause by saturating the ambient air, drastically reducing evaporation rates. |

| Physical Sealing [15] | Use low-evaporation lids, breathable sterile sealing tapes (for cell culture), or clear foil heat seals (for biochemical assays). | Creates a physical barrier that prevents water vapor from escaping the well. |

| Specialized Consumables [2] | Use microplates specifically designed with moats or barrier walls around the outer wells to act as a buffer zone. | Engineered to eliminate the environmental disparity between edge and center wells. |

| Workflow Optimization [15] | Limit the number of times the incubator door is opened and, where possible, reduce the total assay runtime. | Minimizes fluctuations in the incubation environment and limits the time available for evaporation to occur. |

The logical relationship between the root cause and these mitigation strategies can be visualized as follows:

FAQ 3: Beyond evaporation, what other factors threaten reproducibility in high-throughput cell-based screening?

Evaporation is one part of a broader reproducibility challenge. Other critical factors include:

- Biological Reagent Variability: Consistency in starting biological materials is crucial. Using traditional cell differentiation methods can lead to variable cell populations. opti-ox deterministic cell programming is an example of a technology designed to overcome this by producing uniform human iPSC-derived cells, ensuring high lot-to-lot consistency [19].

- Technical and Protocol Complexity: Manual cell culture processes like seeding, feeding, and passaging are labor-intensive and prone to operator-induced variability, especially with complex organoid models [20].

- Data Management and False Positives: HTS generates massive datasets where false positives can arise from assay interference (e.g., chemical reactivity, autofluorescence, or colloidal aggregation). Employing machine learning and cheminformatic triage strategies is essential to identify these false signals [21].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol: Validating an Evaporation Control Strategy

This protocol provides a method to quantitatively assess the effectiveness of different sealing methods or microplate designs.

1. Objective To compare the performance of a standard microplate lid against a specialized low-evaporation seal by measuring evaporation rates and the resulting impact on a cell viability assay.

2. Materials

- Cell culture medium

- Cell line of interest

- Standard 96-well microplate

- Standard microplate lid (control)

- Low-evaporation lid or breathable sealing tape (test)

- Incubator with humidity control

- Precision scale (optional, for gravimetric analysis)

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., MTT, CellTiter-Glo)

3. Methodology

- Step 1: Plate Setup: Seed cells uniformly in all wells of multiple plates according to your standard protocol. Include a column of medium-only wells for background subtraction.

- Step 2: Apply Sealing Methods: Apply the standard lid to one set of plates (Control Group) and the low-evaporation seal to another set (Test Group).

- Step 3: Incubation: Place all plates in the same incubator, ensuring humidity is set to ≥95% rH. Incubate for the duration of your typical assay.

- Step 4: Evaporation Measurement (Gravimetric): Weigh the medium-only wells at the start (T~0~) and end (T~end~) of the experiment using a precision balance. Calculate the percentage volume loss:

((Weight_T0 - Weight_Tend) / Weight_T0) * 100. - Step 5: Assay Readout: After the incubation period, perform a cell viability assay according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Step 6: Data Analysis:

- Plot the evaporation rate for edge wells vs. center wells for both groups.

- Calculate the Z'-factor for the entire plate under both conditions to compare assay robustness.

- Statistically compare the CV of the viability signal between edge and center wells for both groups.

Protocol: Integrating Automated Humidity Control

Automation is key to scalable and reproducible HTS. This protocol outlines steps for leveraging an automated incubator system.

1. Objective To implement and validate a automated humidification system for long-term cultivation, minimizing evaporation without manual intervention.

2. Materials

- Incubator shaker with integrated bidirectional humidity control system [1].

- Sterile water reservoir.

- Microtiter plates with cells or assays.

3. Methodology

- Step 1: System Initialization: Ensure the humidification system's water reservoir is filled with sterile water. Power on the system and allow it to stabilize.

- Step 2: Set-Point Configuration: Program the incubator to maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C) and a relative humidity set point of 95% rH or higher via the bioprocess software [1].

- Step 3: Load Experiment: Place your prepared microtiter plates into the incubator.

- Step 4: Initiate Monitoring: Start the software logging function to record the humidity and temperature every 15 minutes for the duration of the run.

- Step 5: System Validation:

- Data Logging: Verify in the log that humidity was maintained within a tight range (e.g., 95% ± 2%) throughout the run.

- Result Confirmation: At the end of the run, check for visible condensation on the plate lids or well walls. Its absence indicates successful condensation-free operation [1].

- Assay Assessment: Proceed with your experimental readout. Compare the well-to-well consistency of results with previous runs without controlled humidification.

The performance of different humidification systems can be compared based on key operational parameters. Bidirectional control represents the "gold standard" for precision [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Humidification System Performance

| System Type | Max Relative Humidity | Control Principle | Contamination Risk | Condensation Risk | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Water Bath | Uncontrolled | Passive evaporation | High | High | Low |

| Direct Steam | ~85% | Active, one-sided (increase only) | Low | Moderate (reduced by heated door) | High |

| Bidirectional Control | 95% + | Active, two-sided (increase/decrease) | Very Low | Very Low | Very High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Using consistently engineered consumables is a foundational step for reproducible screening.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Reproducibility

| Product / Technology | Function | Key Benefit for Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Nunc Edge Well Plate [2] | Microplate with a moat for buffer liquid. | Physically blocks edge effect, allowing use of all wells in a plate. |

| PermeaPad [22] | Biomimetic barrier in a 96-well format for permeability studies. | Provides a consistent, animal-free alternative to variable cell-based barriers. |

| SpecPlate [22] | High-precision UV/Vis plate with meniscus-free, enclosed chambers. | Eliminates pipetting and meniscus-related variability for accurate absorbance. |

| ioCells [19] | Human iPSC-derived cells produced via deterministic programming (opti-ox). | Provides a highly consistent and defined cell population, reducing biological variability. |

| High-Throughput Genome Releaser (HTGR) [23] | Device for rapid, buffer-free DNA extraction via mechanical squashing. | Enables fast, efficient, and consistent template preparation for PCR screening. |

Evaporation in microtiter plates is a pervasive technical challenge with direct and severe consequences for the reproducibility and scalability of high-throughput screening. By understanding its mechanisms and implementing a systematic approach combining environmental control, specialized consumables, and robust protocols, researchers can significantly enhance data quality, reduce costly artifacts, and build a more reliable foundation for drug discovery and scientific advancement.

Evaporation Control in Practice: Containment and Environmental Solutions

In microtiter plate-based research, evaporation is a pervasive challenge that can critically compromise data integrity. It leads to changes in solute concentration, alters reaction kinetics, and is a primary cause of the "edge effect," where wells on the perimeter of a plate show significant variability compared to central wells [15] [24]. Selecting the appropriate plate seal is a fundamental step in mitigating this risk. This guide provides a detailed comparison of three common sealing solutions—adhesive seals, heat sealing films, and breathable tapes—to help you secure your samples and ensure the reliability of your experimental results.

FAQ: Understanding Microplate Seals

1. What is the primary function of a microplate seal? Microplate seals are designed to protect well contents from evaporation, contamination, and leakage during assay processing, incubation, or storage [25] [26] [27]. By creating a barrier, they maintain sample volume and concentration, which is essential for assay reproducibility and accuracy.

2. How does evaporation cause the "edge effect"? The "edge effect" is a phenomenon where wells on the outer circumference of a microplate exhibit different evaporation rates and results compared to the inner wells. This occurs because the edge wells are less insulated, leading to increased evaporation that changes the concentration of salts and reagents [15] [24]. This results in higher coefficient of variation (CV) values and can impact assay robustness or even cause assay failure.

3. Can I use any clear seal for a fluorescence-based qPCR assay? No, not all clear seals are suitable. For qPCR and other fluorescence assays, you must use seals specifically designed with high optical clarity to permit maximum fluorescence transmission without interference [28]. Standard clear seals may not have the required optical properties and can lead to inaccurate data collection.

4. My samples are sensitive to light. What type of seal should I use? For light-sensitive samples, aluminum foil seals are the best choice. They effectively block incoming light, shielding sensitive samples like fluorophores and preventing sample degradation [25] [26].

5. I need frequent access to my samples. Which seal is most suitable? Pierceable seals are designed for this purpose. They allow you to access the well contents with a pipette tip or robotic probe without removing the entire seal, facilitating multiple access points while maintaining a secure seal against contamination between accesses [25] [29].

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Applications

| Feature | Adhesive Seals | Heat Sealing Films | Breathable Tapes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | PCR, short-term storage, general assays [28] [27] | qPCR, long-term storage, sensitive assays [25] [28] | Cell culture, tissue culture, any application requiring gas exchange [25] [15] |

| Sealing Mechanism | Pressure-sensitive adhesive [25] [27] | Heat-activated fusion [25] | Gas-permeable membrane [25] |

| Ease of Application | Easy; manual or with a roller [25] [29] | Requires a heat-sealing machine [25] [28] | Easy; manual or with a roller [25] |

| Ease of Removal | Easy to peel, may leave residue [26] [27] | Semi-permanent, not removable [28] | Easy to peel [25] |

| Optical Clarity | Good (varies by product) [27] | High; often designed for optical assays [25] | Typically clear |

| Typical Temp. Range | -80°C to 120°C [25] | -80°C to 110°C [25] | -80°C to 110°C [25] |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations

| Seal Type | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Seals | Cost-effective; no special equipment needed; ideal for high-throughput workflows [26] [27] | Seal integrity may be compromised under extreme conditions; may leave adhesive residue [26] [27] |

| Heat Sealing Films | Hermetic, high-integrity seal; superior evaporation prevention; best for long-term storage and automation [25] [28] [27] | Requires dedicated sealing equipment; not removable; consistent heat profile needed [28] [27] |

| Breathable Tapes | Allows essential gas exchange (e.g., CO2/O2) for cell growth; prevents contamination [25] [15] | Less effective at controlling evaporation; not for liquid or vapor-proof sealing [27] |

Troubleshooting Common Seal-Related Issues

Problem 1: Significant Evaporation and Edge Effects

- Potential Cause: An ineffective seal or the wrong seal type for the assay conditions.

- Solution:

- For biochemical assays, switch to a heat seal or an impermeable adhesive foil seal, which provide the most robust barrier against evaporation [15].

- Ensure the seal is applied correctly using a hand roller to create even pressure across all wells [29] [10].

- For cell-based assays, use a breathable seal and ensure the incubator has adjustable humidity, set close to 100% relative humidity, to minimize evaporation [24].

Problem 2: Contamination in Wells

- Potential Cause: A broken seal or improper application, allowing contaminants to enter.

- Solution:

- Visually inspect the seal after application to ensure it is fully sealed around the edges of each well [28] [29].

- When removing adhesive seals, peel slowly from one corner using a steady motion to avoid splashing or pulling contaminants across the plate [29]. Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) during removal.

Problem 3: Poor Fluorescence Signal in qPCR

- Potential Cause: Using a standard clear seal instead of an optically clear seal.

- Solution: Always use seals specifically rated for fluorescence or qPCR to ensure they do not autofluoresce or block the signal [28].

Problem 4: Difficulties in Removing Heat Seals

- Potential Cause: Heat seals are designed to be semi-permanent.

- Solution: Heat seals are generally not intended to be removed. For applications requiring sample access, choose a peelable heat seal foil or use pierceable adhesive seals instead [25] [28].

Workflow and Selection Guide

Diagram: Microplate Seal Selection Workflow

Diagram: Procedure for Applying a Self-Adhesive Seal

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Self-Adhesive Seals | Versatile, easy-to-use seals for a wide range of applications including PCR and short-term sample storage [29] [27]. |

| Heat Sealing Films | Provide a hermetic seal for demanding applications like qPCR and long-term sample storage, requiring a dedicated heat sealer [25] [27]. |

| Breathable Seals | Allow gas exchange while preventing contamination; essential for cell and tissue culture applications [25] [15]. |

| Foil Seals | Provide a light-proof and airtight seal, ideal for light-sensitive samples and long-term cold storage (≤ -80°C) [25] [28] [26]. |

| Pierceable Seals | Enable repeated access to well contents by pipette tips or robotic probes without breaking the overall seal [25]. |

| Hand Roller / Applicator | A tool used to apply even pressure when placing adhesive seals, ensuring a tight seal and removal of air bubbles [28] [29] [10]. |

| Heat Sealing Machine | Equipment required to apply heat seals, providing consistent and reliable semi-permanent seals [25] [28]. |

Utilizing Low-Evaporation Lids and Specialized Microplate Designs

Troubleshooting Guides

G1: Uneven Cell Distribution and Spheroid Formation

- Problem: Inconsistent Multicellular Tumor Spheroid (MCTS) size and shape across the microplate, particularly between edge and center wells.

- Questions to Ask:

- Is the cell suspension being agitated during seeding to prevent settling?

- Was the plate centrifuged after seeding to ensure even cell distribution at the bottom of the wells?

- Root Cause: Uneven cell seeding due to cell settling during the process or improper distribution technique.

- Solution:

G2: Excessive Evaporation in Edge Wells

- Problem: Significant and uneven media loss, especially from the perimeter wells of the microplate, leading to increased variability in assay results.

- Questions to Ask:

- Is the microplate being used with a standard lid or an evaporation-reducing lid?

- How often is the incubator door opened, and for how long?

- Root Cause: Evaporation is exacerbated in edge wells and in incubators with fluctuating humidity levels.

- Solution:

- Use an Evaporation-Reducing Environment Lid: Employ a specialized lid where the side reservoirs are filled with a liquid like sterile water or 5% DMSO [30].

- Optimize Incubator Use: Maintain a stable incubator environment with 95% humidity and avoid opening the door for extended periods [30].

- Automated Systems: For automated systems, choose instruments with built-in evaporation control functions that can maintain sample stability for over 16 hours [31].

G3: Poor Data Reproducibility in High-Throughput Screening

- Problem: High well-to-well variability compromises the reliability and significance of data from drug screening assays.

- Questions to Ask:

- Are the MCTSs being cultured using the liquid overlay technique without further modifications?

- Is the assay duration long enough to require multiple medium changes?

- Root Cause: Uncontrolled evaporation leads to variations in reagent concentration and MCTS growth conditions.

- Solution:

- Adopt Modified Protocols: Implement detailed technical improvements to the liquid overlay technique to increase scalability and reproducibility [30].

- Integrated Automation: Utilize automated microplate handlers that can process plates with lids, providing a sterile environment and preventing evaporation during high-throughput operations [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

F1: What is the primary function of a low-evaporation microplate lid?

A low-evaporation lid is designed to minimize the loss of culture medium from microplate wells during incubation. It typically features reservoirs or channels on its sides that can be filled with liquid (e.g., sterile water or 5% DMSO). This creates a humidified chamber above the plate, drastically reducing the evaporation rate from the wells, particularly those on the outer edges. This leads to more consistent culture conditions and improved experimental reproducibility [30].

F2: How does evaporation impact my MCTS-based assays?

Evaporation causes uneven medium loss across the plate. This results in:

- Increased well-to-well variation in MCTS morphology and growth.

- Changes in reagent and compound concentration, which can alter the apparent efficacy or toxicity of tested drugs.

- Compromised data from pharmacological tests, making results less reliable and difficult to interpret [30].

F3: Can I use any lid with liquid reservoirs to reduce evaporation?

While the principle is similar, it is crucial to use lids specifically designed for your microplate type and size (e.g., 384-well TC-treated plates). Proper fit ensures effective humidity control and prevents contamination. The liquid should be added carefully to the side reservoirs without spilling into the central area or the wells themselves, as excessive liquid can lead to seepage and cross-contamination [30].

F4: Besides specialized lids, what other strategies can reduce evaporation?

- Automated Systems with Evaporation Control: Some modern analytical instruments incorporate built-in evaporation control features to maintain sample concentration during long runs [31].

- Automated Plate Handling: Using systems that can handle lidded plates minimizes exposure to non-humidified air during transfer and measurement steps [32].

- Optimized Incubator Conditions: Using a rotation incubator and maintaining high, stable humidity levels further reduces media loss [30].

The following table summarizes quantitative data related to evaporation effects and the performance of mitigation strategies in microplate-based research.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Evaporation and Mitigation Strategies

| Parameter | Standard Lid / Incubator | Evaporation-Reducing Lid / Rotating Incubator | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaporation-induced CV (Coefficient of Variation) | Significantly higher well-to-well variation | "Much lower" coefficient of variation (CV) | MCTS formation reproducibility in 384-well plates [30] |

| Unattended Run-time with Stable Concentration | Information not available in search results | >16 hours | Bio-layer interferometry (BLI) systems with evaporation control [31] |

| Minimum Sample Volume | Information not available in search results | As low as 40 µL | Compatible volume for 96- and 384-well plates in BLI systems [31] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Low-Evaporation Workflow for MCTS Formation

This protocol details the steps for preparing and using evaporation-reducing lids and agarose-coated plates for reproducible Multicellular Tumor Spheroid (MCTS) culture.

Materials and Reagents

- Low-evaporation environment lid for your microplate format.

- Low-melting point agarose

- Serum-free culture medium

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HCT116 cells)

- Tissue-culture treated microplates (e.g., 384-well)

- Sterile water or 5% DMSO

Procedure

Prepare Agarose-Coated Plates:

- Dissolve 0.75 g of low-melting point agarose in 100 mL of serum-free culture medium [30].

- Heat the solution to dissolve the agarose completely, then autoclave and filter-sterilize it [30].

- Using a reagent dispenser, coat the wells of a 384-well TC-treated microplate with 15 µL of the sterile, molten agarose solution [30].

- Allow the agarose to cool and gel for 15-20 minutes at room temperature. The coated plates can be stored at 4°C for up to two weeks [30].

Prepare the Evaporation-Reducing Lid:

- Using a pipette, slowly add approximately 4 mL of sterile water or 5% DMSO into one of the short-side reservoirs of the environment lid [30].

- Repeat for the reservoir on the opposite side. Critical: Ensure the liquid in the two sides does not merge in the center, leaving a gap for gas exchange [30].

Seed Cells and Initiate Culture:

- Create a single-cell suspension at the desired density (e.g., 2.5×10⁴ cells/mL) [30].

- Seed cells into the agarose-coated plate. For multiple plates, keep the cell suspension agitated to prevent settling [30].

- Let the plate rest at room temperature for 30 minutes, then centrifuge at 4×g for 15 minutes to pellet cells evenly [30].

- Fill the plate's main liquid reservoir with sterile water, replace the standard lid with the prepared evaporation-reducing lid, and place the plate in a stable, humidified (95%) rotating incubator at 37°C [30].

Post-Processing and Analysis:

- After MCTS formation (e.g., 4 days), use an automated plate washer for gentle medium exchange, empirically adjusting the washer manifold's Z-height to avoid disturbing the spheroids [30].

- Image MCTSs using a high-content imaging system with a 4X air objective [30].

- Analyze images using semi-automated software to measure parameters like cross-sectional area, long/short axis, and perimeter [30].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for addressing evaporation issues in microplate-based assays, integrating the use of specialized lids and designs.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Low-Evaporation Microplate Assays

| Item | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Evaporation Environment Lid | Creates a humidified micro-environment above the plate to minimize media loss. | Features side reservoirs for holding sterile water or DMSO; allows for gas exchange [30]. |

| Low-Melting Point Agarose | Used for coating plates in the liquid overlay technique (LOT) to create a non-adherent surface for 3D spheroid formation. | Forms a hydrogel that prevents cell attachment; can be sterilized by autoclaving and filtration [30]. |

| Tissue-Culture Treated Microplates | The base platform for cell culture and assay execution. | Surface-treated for optimal cell growth; available in 96- and 384-well formats for high-throughput screening [30]. |

| Automated Microplate Handler | For integrated, high-throughput workflows, reducing manual handling and exposure to dry air. | Can handle lidded plates; provides a sterile environment and prevents evaporation [32]. |

| Analytical System with Evaporation Control | For running long-duration, unattended analyses (e.g., binding kinetics). | Built-in functionality to maintain analyte concentration over extended periods (e.g., >16 hours) [31]. |

In the realm of life sciences research, particularly in applications using microtiter plates, the precise control of humidity is not a luxury but a fundamental necessity. Evaporation of culture medium from small-volume wells leads to significant shifts in osmolarity, concentration of salts and ions, and oxygen solubility. These undefined changes introduce substantial artifacts, compromising the statistical validity and reproducibility of screening processes and Design of Experiment (DoE) studies [1]. Active humidification systems are engineered specifically to counteract these effects by maintaining a high-humidity environment within incubation shakers, thereby preserving the integrity of your experimental conditions.

Understanding Humidification Systems

Types of Humidification Systems

Researchers have several options for controlling evaporation, each with distinct mechanisms and performance characteristics.

- Open Water Bath (Passive Humidification): This simple approach involves placing a free-standing tray of water inside the incubation chamber. The water evaporates naturally, raising the relative humidity. While cost-effective and quick to set up, it offers no active control. This often leads to condensation on the chamber walls and door, and the standing water presents a significant contamination risk for cultures [1].

- Direct Steam Humidification (Active): This system provides active, one-sided control to increase humidity. It works by flash-vaporizing single water droplets in a heated pod and introducing the hygienic steam directly into the incubation chamber. This allows for precise regulation, logging, and saving of humidity setpoints, often up to 85% relative humidity (rh). To mitigate condensation, these systems typically include a heated door panel [1].

- Bidirectional Humidity Control (Active High-End): Representing the "gold standard," this system can both increase and decrease the humidity level inside the chamber. Humidification works similarly to the direct steam method. Dehumidification is achieved by blowing ambient, dry air through a sterile filter into the chamber. This allows for precise selection of a specific humidity setpoint across a broad range and ensures condensation-free operation, even at low incubation temperatures [1] [33]. Some systems, like those using Peltier elements, can control humidity within a range of 50% to 85% rh [33].

Comparative Analysis of Humidification Systems

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these different humidification approaches for easy comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Humidification Systems in Incubator Shakers

| System Type | Control Mechanism | Typical Humidity Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Water Bath [1] | Passive evaporation | Uncontrolled | Low cost, simple setup | High contamination risk, condensation, no control |

| Direct Steam Humidification [1] | Active, one-sided (humidify only) | Up to ~85% rh | Controlled, reproducible conditions; reduced contamination risk; data logging | Cannot lower humidity; may not prevent all condensation |

| Bidirectional Humidity Control [1] [33] | Active, two-sided (humidify & dehumidify) | e.g., 50% - 85% rh (varies by tech) | Precise setpoint control; condensation-free operation; "gold standard" for reproducibility | Higher cost, more complex system |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation requires the right tools. The following table details key materials and reagents essential for managing evaporation and ensuring sterility in microtiter plate-based research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Evaporation Control

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plate Box [1] | A sealed container with a filter that creates a localized humidified microenvironment, drastically reducing evaporation without a full incubator humidification system. | Cultivation in microtiter and deep-well plates; provides a sterile barrier when loaded under a clean bench. |

| Anti-Evaporation Oil [34] | A gas-permeable silicone oil overlaid onto culture medium. It is highly permeable to O₂ and CO₂ but effectively blocks water vapor loss. | Long-term live-cell imaging studies; low-volume culture experiments where even minor evaporation is critical. |

| Humidity Standard (e.g., Lithium Chloride) [33] | A certified solution used to generate a known relative humidity in a closed chamber for the calibration of a humidity sensor. | Regular calibration of an incubator shaker's humidity probe to ensure measurement accuracy. |

| Cell Culture Media Supplements (e.g., N2, B27) [35] | Chemically defined formulations that provide known quantities of survival factors, hormones, and proteins, replacing variable serum. | Maintaining strict control over the cellular environment; serum-free cell culture. |

| Bicarbonate Buffer [35] | A buffer system in culture media that maintains physiological pH (around 7.4) in a 5% CO₂ environment. | Standard cell culture in CO₂ incubators. |

| HEPES Buffer [35] | An additional chemical buffer added to culture media to maintain pH stability during extended periods of manipulation outside a CO₂ incubator. | Experiments requiring cells to be outside the incubator (e.g., during microscopy or manipulation). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Humidification

1. Why is a simple water bath insufficient for reliable microtiter plate screening? An open water bath provides passive, uncontrolled humidity. This leads to inconsistent evaporation rates across a microtiter plate, causing well-to-well variation in medium concentration. This variability compromises the statistical validity of high-throughput screening data. Furthermore, the standing water is a breeding ground for mold and bacteria, posing a high contamination risk [1].

2. My experiments require temperatures below ambient. How can I prevent condensation when using humidity? Condensation occurs when the chamber air, cooled by the walls, reaches its dew point. Bidirectional humidity control systems are specifically designed for this. They can actively dehumidify the chamber air by introducing dry, filtered air, maintaining the desired humidity setpoint without condensation, even at low temperatures [1].

3. What is the target relative humidity for effectively preventing evaporation in an incubator shaker? Optimal relative humidity within an incubation system should be within the range of 90% to 95% [34]. This high humidity level is crucial for artifact-free results, as it minimizes evaporation from cell culture vessels, preventing undefined concentration of salts, nutrients, and waste products.

4. How does evaporation physically harm my cell cultures? Evaporation does not just remove water. It leads to:

- Increased Osmolarity: Concentrates solutes, stressing cells and affecting proliferation and metabolism [1] [36].

- Altered Ion/Growth Factor Concentration: Shifts the chemical environment away from the designed medium formulation [1] [36].

- Changes in Oxygen Solubility: Can affect cellular respiration and metabolic pathways [1]. Cells are highly sensitive to these changes, which can induce stress responses, alter gene expression, and even trigger apoptosis [34].

5. How often should I calibrate the humidity sensor on my incubator shaker, and how is it done? Calibration frequency should follow the manufacturer's recommendations, but it is good practice before critical long-term studies. The process is user-performable. It requires a certified moisture meter or a calibration device with a humidity standard (e.g., a specific lithium chloride solution that generates a known %rh). This standard is applied to the sensor in a small chamber, and the reading is adjusted to match the known value via software [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problems and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Humidification System Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Checks |

|---|---|---|

| High Evaporation Loss | 1. Humidity setpoint too low.2. Water reservoir is empty or faulty refill.3. Door seal is damaged or chamber door is not fully closed.4. Sensor out of calibration. | 1. Increase humidity setpoint to >90% rh.2. Refill the water reservoir and check the auto-refill function.3. Inspect the door seal and ensure the door is properly sealed.4. Re-calibrate the humidity sensor [33]. |

| Excessive Condensation | 1. Humidity setpoint is too high for the current chamber temperature.2. Malfunction in dehumidification function (for bidirectional systems).3. Door heater not functioning. | 1. Slightly lower the humidity setpoint.2. Service the dehumidification unit.3. Check and service the door heating system [1] [33]. |

| Contamination of Cultures | 1. Contaminated water in the reservoir or humidification system.2. Contamination from an open water bath.3. Non-sterile humidification steam. | 1. Use sterile, distilled water and follow manufacturer decontamination protocols for the water system [37].2. Replace open baths with active, hygienic steam humidification [1].3. Ensure the humidification system includes a thermal sterilization cycle for the vapor [37]. |

| Inaccurate Humidity Reading | 1. Sensor drift over time.2. Sensor contamination.3. Faulty sensor or electronics. | 1. Perform a full calibration of the humidity sensor [33].2. Clean the sensor according to the user manual.3. Contact technical support for sensor replacement. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Evaporation Rates in Microtiter Plates

Aim: To empirically determine the evaporation rate from microtiter plates under different incubator shaker humidification settings.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Prepare a solution of distilled water with a low-concentration visible dye (e.g., phenol red) or a sterile, non-volatile tracer. This allows for easy visualization and prevents microbial growth.

- Plate Setup: Using a multi-channel pipette, fill all wells of a standard 96-well microtiter plate with an identical, precise volume (e.g., 200 µL) of the prepared solution. Seal the plate with a lid.

- Initial Weighing: Accurately weigh the sealed plate using an analytical balance and record this initial mass (M_initial).

- Experimental Groups: Place the plate in the incubator shaker. Run the experiment for a set duration (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours) under different test conditions:

- Group A: No active humidification (control).

- Group B: Active humidification set to 70% rh.

- Group C: Active humidification set to 90% rh.

- Group D: Plate housed inside a microtiter plate box within the shaker [1].

- Final Weighing: After the set duration, remove the plate, allow it to cool to room temperature in a dry environment (to prevent condensation on the outside), and weigh it again (M_final).

- Calculation: Calculate the total fluid loss for each plate: Evaporation (µL) = (Minitial - Mfinal) / Density of water. Assume the density of water is 1 g/mL for conversion. Divide the total loss by the number of wells to estimate average evaporation per well.

This protocol provides quantitative data to validate the effectiveness of your humidification system and optimize parameters for specific applications.

System Workflows and Logical Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of selecting the appropriate humidification strategy based on experimental needs, culminating in the advanced operation of a bidirectional control system.

The diagram below details the operational logic of a feedback-controlled active humidification system, such as those used in advanced incubators or live-cell imaging stage top systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "edge effect" in microplate assays and how does it relate to evaporation? The "edge effect" is a phenomenon where the medium in the outer wells of a microplate evaporates during incubation. This leads to varying well volumes, changes in reagent concentration, and altered evaporation rates, which can significantly compromise cell viability and skew assay results [2].

Q2: How can I prevent evaporation in my microplate assays? Several effective methods can minimize evaporation:

- Use Proper Seals: Apply optically clear, adhesive sealant films firmly over the entire plate, ensuring contact with all well rims. Use a sealing applicator for best results [38] [10].

- Maintain Humidity: Incubate plates in a humidified environment (at least 95% humidity) [2].

- Reduce Incubator Openings: Limit the number of times the incubator door is opened to maintain a stable environment [2].

- Use Specialized Plates: Consider using microplates with a built-in moat around the outer wells that can be filled with a sterile liquid to create a buffer zone against evaporation [2].

- Cover with Oil: For some applications, adding a layer of paraffin or silicon oil on top of the sample can prevent evaporation. Ensure the oil is compatible with your plate material and assay [10].

Q3: My assay signal is inconsistent across the plate. Could evaporation be the cause? Yes, differential evaporation from wells, particularly those on the perimeter, is a common cause of signal inconsistency. Evaporation changes concentrations and volumes, leading to high well-to-well variability. Using a plate seal and controlling incubation conditions are critical to mitigate this [39].

Q4: How does temperature control affect assay reproducibility? Temperature is critical for enzymatic and cell-based assays. Fluctuations in lab temperature or heat from the microplate reader's internal motors can create gradients across the plate, leading to poor precision and variable data. Active cooling technology in plate readers can help maintain a consistent, user-defined temperature for more reliable results [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Evaporation and Edge Effects

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable data & high edge well variation | Differential evaporation from outer wells [2] [39]. | Use a plate seal; incubate in >95% humidity; use microplates with a protective moat [2]. |

| Low amplification or signal in qPCR | Sample evaporation leading to underfilled wells and poor heat transfer [38]. | Do not exceed recommended fill volumes; avoid underfilling wells to minimize headspace [38]. |

| Signal inconsistency across the plate | Warped plates or poorly fitted plate seals causing uneven evaporation [39]. | Check plates for defects; ensure seals are applied properly and cover the plate completely [39]. |

| Unexpected signal gradients | Plate temperature not equilibrated with the reader before measurement [39]. | Equilibrate the plate for at least 30 minutes next to the instrument prior to reading [39]. |

Table 2: Optimizing Incubation Time and Temperature

The following table summarizes key findings from optimized protocols where adjustments to time and temperature significantly improved assay performance.

| Assay Type | Original Protocol | Optimized Protocol | Key Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase Activity | Single measurement at 20°C [41]. | Four time-point measurements at 37°C [41]. | Reproducibility improved up to 4-fold (interlab CV 16-21%); activity increased 3.3-fold [41]. | |

| Resazurin Microplate Assay (REMA) for Anti-MRSA/MSSA | 24-hour incubation; 6.75 mg/mL dye [42]. | 5-hour incubation; 0.01 mg/mL dye [42]. | Reaction time reduced from 18 hours to 1 hour; efficient and fast results [42]. | |

| Cell Viability (3D Spheroid Cultures) | 10 min - 3 hr incubation (for 2D cells) [43]. | 5 - 10 hr incubation (for 3D spheroids) [43]. | Maximized signal and stayed within the linear range of the assay [43]. |

Experimental Protocols

1. Objective: To provide a standardized, reproducible method for measuring α-amylase activity in fluids and enzyme preparations.

2. Key Adjustments from Original Protocol:

- Temperature: Increased from 20°C to a more physiologically relevant 37°C.

- Measurements: Changed from a single-point to a multi-time-point measurement.

- Definition of Activity: One unit liberates 1.0 mg of maltose from starch in 3 minutes at pH 6.9 at 37°C.

3. Materials:

- Enzyme sources: Human saliva, porcine pancreatin, porcine pancreatic α-amylase.

- Substrate: Potato starch solution.

- Detection: Quantification of reducing sugars as maltose equivalents using a colorimetric reaction.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer or microplate reader; water bath, shaking water bath, or thermal shaker set to 37°C.

4. Procedure:

- Prepare a dilution series of your enzyme sample.

- Incubate the enzyme with starch substrate at 37°C for a defined period.

- Stop the reaction and quantify the reducing sugars produced at four different time points.

- Generate a standard curve using maltose.

- Calculate the enzyme activity based on the rate of maltose production.

1. Objective: To rapidly determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of antibiotics against bacteria like MRSA and MSSA.

2. Key Optimizations:

- Dye Concentration: Reduced resazurin dye concentration from 6.75 mg/mL to 0.01 mg/mL.

- Incubation Time: Shortened the incubation period before reading from 18-24 hours to 5 hours.

3. Materials:

- Bacterial strains (e.g., MRSA, MSSA).

- Cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth.

- Antibiotics for testing (e.g., oxacillin, vancomycin).

- Resazurin dye stock solution (0.01 mg/mL).

- 96-well microtiter plates.

- Microplate reader.

4. Procedure:

- Perform a two-fold serial dilution of the antibiotic in a 96-well plate.

- Inoculate each well with a standardized bacterial suspension.

- Incubate the plate for 5 hours at 35±2°C.

- Add the optimized concentration of resazurin dye (0.01 mg/mL) to each well.

- Incubate for 1 hour or until a color change is visible.

- Read the optical density using a microplate reader. A color change from blue (oxidized) to pink/purple (reduced) indicates bacterial growth.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evaporation Control and Assay Optimization

| Item | Function | Example / Key Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Sealant Films | Seals microplates to prevent evaporation and contamination; optically clear for fluorescence reading [10]. | Polyolefin silicone tape (e.g., Nunc Sealing Tape) [10]. |

| Plate Seal Applicator | Ensures sealant film is applied evenly and firmly for a complete seal on all wells [38]. | Hand-held roller applicator. |

| Humidified CO2 Incubator | Maintains a high-humidity environment (≥95%) to minimize evaporation from plates during long-term culture [2]. | |

| Specialized Microplates | Plates designed with a moat around the edge wells to be filled with liquid, creating a buffer against evaporation [2]. | Thermo Scientific Nunc Edge Plate. |

| Paraffin or Silicon Oil | Creates a physical barrier over samples in wells to prevent evaporation; ideal for high-temperature applications [10]. | Must be compatible with plate material (avoid paraffin oil with COP/COC plates) [10]. |

| Microplate Reader with Active Cooling | Prevents internal heat buildup and maintains a consistent, user-definable temperature for the entire plate, reducing thermal gradients [40]. | Technology such as Tecan's Te-Cool [40]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Logical workflow for troubleshooting and resolving evaporation-related issues in microtiter plate assays, leading to more reliable data.

Advanced Troubleshooting: Proven Strategies to Minimize Edge Effect and Evaporation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is evaporation a significant problem in microtiter plate assays? Evaporation causes two major issues that compromise assay integrity. First, it leads directly to the loss of liquid volume, which can concentrate reagents and samples, altering reaction kinetics and leading to inaccurate results [44]. One study found that highly permeable sealing tapes resulted in liquid loss of up to 25% of the initial filling volume after just 8 hours at 37°C [44]. Second, the process of evaporative cooling can induce substantial temperature gradients within the plate, with measured deviations of up to 3.8°C from the set point, which in turn can cause enzyme activity variation of about 20% [44] [45]. This is particularly problematic for high-throughput screening and long-term cell culture, such as spheroid formation, where consistency across all wells is essential [46].

2. Which part of the microtiter plate is most affected by evaporation? Evaporation-induced "edge effects" primarily impact the outer perimeter wells of a microtiter plate [45] [46]. These wells are more exposed to ambient air currents and temperature fluctuations, leading to greater well-to-well variability compared to the more protected inner wells. This effect can ruin the reproducibility of an entire plate by creating a systematic error pattern.

3. How can I reduce evaporation when working with nanolitre-volume droplets? For nanolitre-volume assays, specialized plate lids with small apertures can drastically reduce evaporation. One study demonstrated that custom-designed snap-on lids, which cover over 90% of the plate's surface area, can reduce the rate of evaporation by 63% to 82% [47]. These lids feature small openings that are large enough for pipetting or acoustic droplet ejection but small enough to shield the droplets from room air, thereby preserving the droplet for a sufficient time to set up the experiment.

4. Does the choice of microplate sealant really matter? Yes, the choice of sealant is critical and involves a key trade-off. Research has shown that commercial sealing tapes are often inadequate, failing to fulfill the simultaneous requirements for aerobic microbial cultivation. Some seals are highly impermeable to water vapor but are also impermeable to oxygen, thereby suffocating aerobic cultures [44]. Conversely, seals that permit sufficient oxygen transfer can allow excessive water evaporation. Therefore, the seal must be selected based on the specific gas exchange needs of the assay.

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Evaporation

Gravimetric Method for Direct Evaporation Measurement

The gravimetric method is a direct and reliable technique for quantifying evaporation by measuring mass loss over time.

- Principle: The mass of a liquid lost from a microplate well is directly equivalent to the volume evaporated. By periodically measuring the mass of the entire plate or individual wells, you can calculate the evaporation rate.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Fill the microplate wells with a known volume of ultrapure water or your assay buffer. Include all planned sealants or lids.

- Initial Weighing: Use an analytical balance with high precision (e.g., 0.1 mg) to record the initial mass (M₀) of the entire plate.

- Incubation: Place the plate in the assay environment (e.g., incubator, reader) under standard operational conditions (temperature, humidity).

- Periodic Weighing: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours), remove the plate and record its mass (Mₜ). Ensure the plate is briefly cooled to room temperature before weighing to avoid convection currents affecting the balance.

- Calculation: Calculate the cumulative evaporation or evaporation rate.

- Cumulative Evaporation (%) at time t =

[(M₀ - Mₜ) / M₀] × 100% - Evaporation Rate (mg/h) =

(M₀ - Mₜ) / t

- Cumulative Evaporation (%) at time t =

Key Consideration: This method was used to reveal significant performance differences between 12 commercially available sealing tapes [44]. It provides a direct, whole-plate measurement but does not easily resolve individual well differences.

Assessing Evaporation via Temperature Measurement

Since evaporative cooling is a direct consequence of evaporation, monitoring well temperature can serve as a sensitive, non-invasive proxy for evaporation.

- Principle: As liquid evaporates, it absorbs heat energy from the remaining solution, causing its temperature to drop. The magnitude of this temperature drop correlates with the rate of evaporation.

- Procedure using a Dye-Based Indicator:

- Select a Thermometric Dye: Use a temperature-sensitive absorbance dye like cresol red, which has a reported accuracy of ±0.16°C [45].

- Prepare Solution: Add a low, non-interfering concentration of the dye to your standard assay buffer.

- Plate Setup: Fill the wells of your microplate with the dye solution.

- Measurement: Place the plate in a temperature-controlled microplate reader. Monitor the absorbance of the dye at its temperature-sensitive wavelength over time. The measured absorbance can be converted to temperature using a pre-established calibration curve.

- Data Interpretation: Wells experiencing higher evaporation rates will show lower steady-state temperatures. This method can map spatial temperature profiles across a plate, revealing edge effects and deviations of over 2°C [45]. It is excellent for identifying thermal gradients but is an indirect measure of volume loss.

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from key studies on evaporation control methods.

Table 1: Efficacy of Different Evaporation Control Methods

| Method | Experimental Context | Key Quantitative Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Lids with Apertures | Vapor-diffusion crystallization with nanolitre volumes | Reduced evaporation rate by 63% to 82% | [47] |

| Commercial Sealing Tapes | Aerobic microbial cultivation in MTPs, 8h at 37°C | Liquid loss of up to 25% of initial volume | [44] |

| Evaporative Cooling | Enzyme activity assays in 96-well MTPs | Temperature deviations of up to 2.2-3.8°C | [44] [45] |

| Aperture Size Reduction (from 0.88mm to 0.44mm) | CrystalQuick X plate with plate lids | Increased evaporation reduction from 81% to 90% | [47] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Evaporation Management

Table 2: Key Reagent and Material Solutions for Managing Evaporation

| Item | Function/Benefit | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Balance | Precisely measures mass loss in the gravimetric method. | Essential for direct quantification of evaporation; requires high precision (0.1 mg or better). |

| Thermometric Dye (e.g., Cresol Red) | Acts as a non-invasive optical thermometer to detect evaporative cooling. | Allows for spatial and temporal mapping of temperature profiles within a plate [45]. |

| Custom 3D-Printed Plate Lids | Covers most of the plate surface, leaving small apertures for access, to drastically reduce evaporation. | Highly effective for nanolitre-volume assays and vapor-diffusion experiments [47]. |

| Low-Profile Sealing Tapes | Creates a vapor-tight seal over the plate. | Critical: Must be selected for a balance of low water vapor permeability and sufficient oxygen transfer if needed [44]. |

| Half-Area or Small-Volume Microplates | Reduces the surface-area-to-volume ratio, which can help minimize evaporative loss. | An alternative to 384-well plates for assay miniaturization with less handling complexity [48] [49]. |