Counter-Flow vs. Parallel-Flow Reactors: A Thermal Performance Comparison for Advanced Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations in chemical reactors, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Counter-Flow vs. Parallel-Flow Reactors: A Thermal Performance Comparison for Advanced Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations in chemical reactors, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles governing each design, examines advanced methodological approaches including CFD and machine learning for performance analysis, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate issues like thermal hotspots and catalyst deactivation. Through a comparative validation of thermal efficiency, mixing characteristics, and operational stability across various reactor types, this review synthesizes critical insights to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing reactor designs for enhanced synthesis efficiency, improved safety, and superior product yield in biomedical applications.

Core Principles: Understanding Flow Dynamics and Heat Transfer Mechanisms

In the field of thermal sciences, the efficient transfer of heat between fluid streams is a critical function across numerous industries, including power generation, chemical processing, and advanced nuclear systems. The configuration of fluid paths within a heat exchanger—specifically whether they move in the same or opposite directions—profoundly influences the system's thermal efficiency, temperature distribution, and structural longevity [1] [2]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of parallel-flow and counter-flow configurations, framing the analysis within contemporary thermal performance reactor research. It synthesizes fundamental definitions with experimental data and methodologies to support researchers, scientists, and engineers in making informed design decisions for advanced thermal systems.

Fundamental Definitions and Basic Principles

Parallel-Flow Configuration

A parallel-flow, or cocurrent, heat exchanger is characterized by both the hot and cold fluids entering the unit from the same end and traveling in the same direction toward the opposite exit [3] [2]. This arrangement results in a large temperature difference at the inlet, which decreases significantly along the flow path as the fluids approach thermal equilibrium [4]. The primary advantage of this configuration is its ability to produce more uniform wall temperatures, which can reduce thermal stress in certain applications [1]. However, a major thermodynamic limitation is that the outlet temperature of the cold fluid can never exceed the outlet temperature of the hot fluid [2].

Counter-Flow Configuration

In a counter-flow, or countercurrent, heat exchanger, the hot and cold fluids enter the unit from opposite ends and flow in opposite directions [3] [2]. This arrangement maintains a more consistent temperature differential between the two fluids across the entire length of the exchanger [5]. This consistent driving force for heat transfer makes the counter-flow design the most thermally efficient common configuration [5] [3]. A key advantage is that the outlet temperature of the cold fluid can approach, and in theory even exceed, the inlet temperature of the hot fluid, allowing for greater temperature changes in the fluids [4] [2].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The fundamental differences in flow direction lead to distinct performance characteristics, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Parallel-Flow and Counter-Flow Configurations

| Performance Characteristic | Parallel-Flow Configuration | Counter-Flow Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Efficiency | Lower; temperature difference decays along the flow length [1] [4]. | Higher; more uniform temperature difference enables maximum heat transfer [1] [5] [2]. |

| Outlet Temperature Potential | Cold fluid outlet temperature cannot exceed hot fluid outlet temperature [2]. | Cold fluid outlet temperature can approach the inlet temperature of the hot fluid [4] [2]. |

| Thermal Stress Profile | Large temperature difference at inlet creates significant thermal stress [4] [2]. | More uniform temperature difference minimizes thermal stresses throughout the exchanger [1] [2]. |

| Structural & Flow Dynamics | Simpler flow management [1]. Can induce swirling flows and mechanical stress in reactor cores [6]. | More complex flow management [5]. Promotes more uniform velocity distribution and reduces swirling [6]. |

| Ideal Application | Bringing two fluids to nearly the same temperature; applications where moderate heat transfer is sufficient and simplicity is desired [1] [4]. | Maximizing heat transfer efficiency; applications requiring high thermal performance and tight temperature approaches [6] [5]. |

Experimental Data and Research in Advanced Reactor Systems

Recent experimental and computational studies in advanced nuclear reactors provide quantitative data on the performance of these flow configurations under high-performance conditions.

A comparative Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) study of a Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR) mini demonstrator analyzed both parallel and counter-flow arrangements. The research employed a variable turbulent Prandtl number model to accurately simulate the behavior of the liquid metal coolant, which has a uniquely low Prandtl number [6].

Table 2: Experimental Results from Dual Fluid Reactor Mini Demonstrator Study [6]

| Parameter | Parallel-Flow Configuration | Counter-Flow Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Supports efficient heat transfer. | Higher heat transfer efficiency. |

| Flow Uniformity | Generates intense swirling in fuel pipes. | More uniform flow velocity. |

| Mechanical Stress | Increased stress due to swirling. | Reduced mechanical stress. |

| Temperature Distribution | Gradual heat exchange, smoother thermal gradients. | Maintains a stable temperature gradient, reducing risk of localized hotspots. |

| Swirling Effects | Significant swirling effects present. | Significantly reduced swirling effects. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Nuclear Reactor Core Analysis

The experimental data in Table 2 was generated through a rigorous computational protocol, which can be summarized as follows:

- Computational Model Setup: The study modeled a DFR mini demonstrator core containing 7 fuel pipes and 12 coolant pipes. To optimize computational resources, a quarter of the domain was simulated by leveraging geometric symmetry. Parameters and dimensions were selected to match typical values in DFR studies [6].

- Governing Equations: The simulation solved the time-averaged mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations for incompressible flow. The key equations included:

- Continuity:

∂ρ/∂t + ∂(ρU_i)/∂x_i = 0 - Momentum:

∂(ρU_i)/∂t + ∂(ρU_j U_i)/∂x_j = -∂p/∂x_i + ∂/∂x_j [μ(∂U_i/∂x_j + ∂U_j/∂x_i) - ρu'_i u'_j] - Energy:

∂(ρT)/∂t + ∂(ρU_j T)/∂x_j = ∂/∂x_j [(Γ + Γ_t) ∂T/∂x_j][6]

- Continuity:

- Turbulence and Low-Prandtl Modeling: A critical aspect of the methodology was accurately modeling the low-Prandtl number liquid metal coolant. The study incorporated a variable turbulent Prandtl number (

Pr_t) model, using the empirical correlationPr_t = 0.85 + 0.7 / Pe_t, wherePe_tis the turbulent Péclet number. This approach was validated in prior work to improve prediction accuracy for liquid metals [6]. - Analysis and Comparison: With the model established, researchers simulated and analyzed both flow configurations, comparing results for temperature gradients, velocity profiles, swirling effects, and resultant mechanical stresses on the reactor core structure [6].

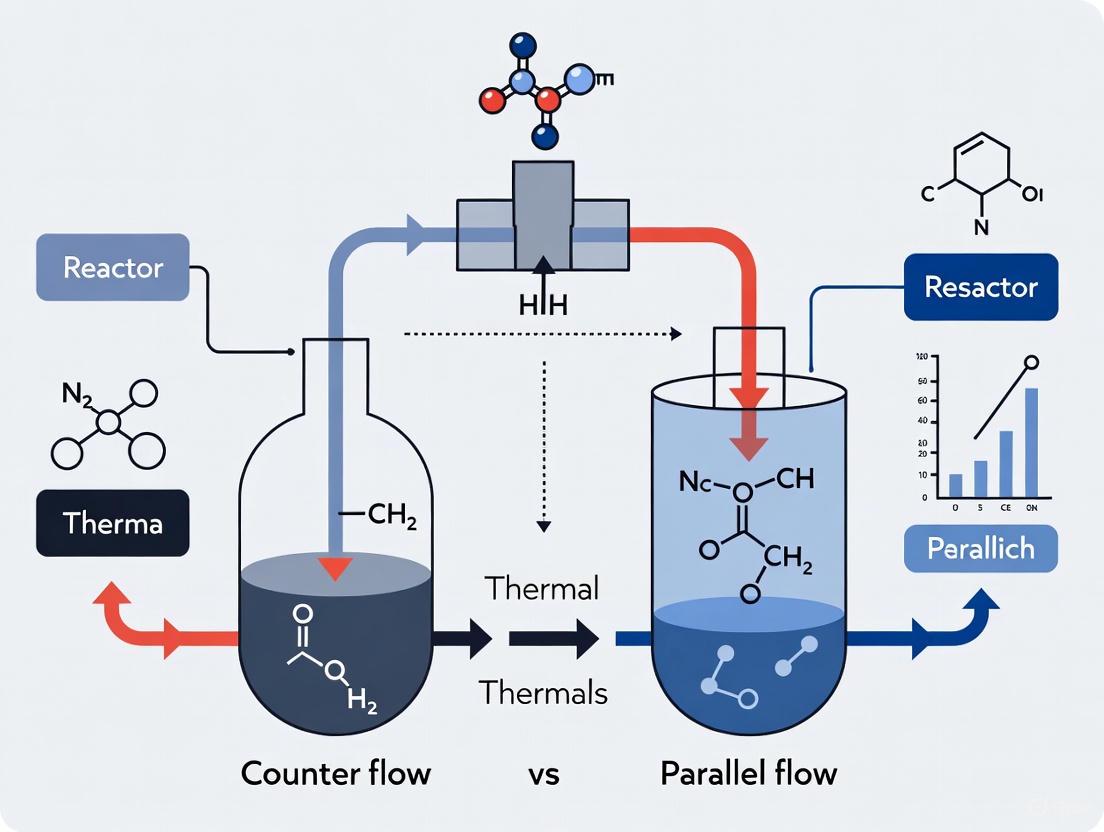

Diagram 1: The consistent temperature gradient in counter-flow (top) allows the cold fluid to reach a higher outlet temperature. In parallel-flow (bottom), the temperature difference diminishes significantly along the flow path, limiting the cold fluid's temperature rise [4] [2].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Thermal-Flow Analysis

The experimental and computational analysis of flow configurations relies on a suite of specialized tools and concepts.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Thermal-Flow Research

| Item / Concept | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) | A primary tool for simulating complex heat transfer and fluid flow dynamics in virtual prototypes, reducing the need for costly physical experiments [6]. |

| Variable Turbulent Prandtl Number Model | An advanced CFD modeling technique crucial for accurately simulating heat transfer in fluids with low Prandtl numbers, such as liquid metals used in advanced reactors [6]. |

| Log Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD) | The driving temperature gradient for heat exchange in a system. Calculating the LMTD is a fundamental step in the design and performance analysis of heat exchangers [2]. |

| Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger | A common hardware design that can be configured for either parallel or counter-flow. It consists of a series of tubes enclosed in a shell, providing a versatile platform for comparative studies [3] [2]. |

| Goodness Factor (j/f) | A performance metric used in microchannel heat exchanger (MCHE) research that balances the Colburn j-factor (heat transfer) against the fanning friction factor (flow resistance) [7]. |

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for conducting a comparative analysis of parallel and counter-flow configurations, illustrating the steps from model setup to final performance evaluation.

The choice between parallel-flow and counter-flow configurations is a fundamental design decision with significant implications for thermal system performance. While parallel-flow offers simplicity and uniform wall temperatures, counter-flow provides superior thermal efficiency, a more favorable temperature profile, and reduced mechanical stresses in high-performance applications like advanced nuclear reactors [6] [1] [2]. The experimental data and methodologies outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to evaluate these configurations against the specific requirements of their systems, whether for power generation, chemical processing, or thermal management in scientific equipment.

In thermal engineering, the Log Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD) is a critical concept used to determine the temperature driving force for heat transfer in flow systems, particularly in heat exchangers [8]. It represents a logarithmic average of the temperature difference between the hot and cold streams at each end of an exchange system and is fundamental to calculating the heat transfer rate in various exchanger configurations [9] [8]. For any given heat exchanger with constant area and heat transfer coefficient, a larger LMTD value directly correlates with greater heat transfer [8]. The method arises straightforwardly from analyzing heat exchangers with constant flow rates and fluid thermal properties, providing engineers with a powerful tool for thermal design and performance evaluation across numerous industries, including pharmaceutical processes where precise temperature control is paramount [8].

The fundamental formula for calculating LMTD is expressed as:

LMTD = (ΔT₁ - ΔT₂) / ln(ΔT₁/ΔT₂)

where ΔT₁ and ΔT₂ represent the temperature differences between the hot and cold fluids at the two ends of the heat exchanger [9] [8]. This logarithmic mean always remains less than the arithmetic mean temperature difference, with the discrepancy increasing as the difference between ΔT₁ and ΔT₂ widens [10]. The LMTD method enables researchers to account for the non-linear temperature profiles that develop along the heat exchanger length, which is particularly important in pharmaceutical applications where precise thermal management can affect reaction kinetics and product quality [9].

Theoretical Foundations: Temperature Gradients and Heat Transfer Fundamentals

The derivation of the LMTD method stems from applying Newton's Law of Cooling, which states that the heat transfer rate is related to the instantaneous temperature difference between hot and cold media [10]. In a practical heat transfer process, this temperature difference varies with position and time, necessitating an integrated approach to calculate the effective mean temperature difference [10]. The mathematical derivation assumes that the local exchanged heat flux at any point along the heat exchanger (z) is proportional to the local temperature difference [8]:

q(z) = α(T₂(z) - T₁(z)) = αΔT(z)

where α represents the heat transfer coefficient. The temperature gradients of both fluids follow Fourier's law, and when summed together, they yield a differential equation that can be solved to arrive at the LMTD expression [8]. This derivation reveals why the LMTD is more physically accurate than a simple arithmetic mean for systems with exponential temperature change along the flow path [9].

The LMTD method, however, operates under several important assumptions that define its limitations: constant fluid specific heat, constant heat transfer coefficient, negligible heat losses to the environment, no phase change during heat transfer, and steady-state operation [8]. Additionally, the method neglects changes in kinetic and potential energy [8]. In pharmaceutical research applications, where fluid properties may vary with temperature or composition, these limitations become significant, and modifications to the classical LMTD method may be necessary for accurate predictions [11].

Comparative Analysis: Counter-flow vs. Parallel-flow Configurations

Fundamental Operational Differences

The primary distinction between counter-flow and parallel-flow heat exchangers lies in the relative direction of the hot and cold fluid streams. In parallel-flow (or co-current) configurations, both fluids enter from the same end and flow in the same direction, resulting in large temperature differences at the inlet that decrease exponentially along the flow path [9]. Conversely, in counter-flow configurations, the fluids enter from opposite ends and flow in opposite directions, maintaining a more uniform temperature difference across the entire length of the exchanger [9]. This fundamental operational difference has profound implications for thermal efficiency and temperature gradients, which are critical considerations in pharmaceutical reactor design where thermal homogeneity affects reaction yields and product consistency.

The temperature difference terms ΔT₁ and ΔT₂ are defined differently for each configuration. For parallel-flow arrangements:

ΔT₁ = Tₕᵢ - T꜀ᵢ (inlet primary and secondary fluid temperature difference)

ΔT₂ = Tₕₒ - T꜀ₒ (outlet primary and secondary fluid temperature difference) [9] [10]

For counter-flow arrangements:

ΔT₁ = Tₕᵢ - T꜀ₒ (inlet primary and outlet secondary fluid temperature difference)

ΔT₂ = Tₕₒ - T꜀ᵢ (outlet primary and inlet secondary fluid temperature difference) [9] [10]

These differing definitions directly impact the resulting LMTD value and consequently the heat exchanger performance.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Data

Experimental and numerical studies consistently demonstrate the superior performance of counter-flow configurations over parallel-flow designs across multiple performance metrics. Recent research investigating a three-chambered parallel plate heat exchanger using cold ionanofluid and hot oil revealed significant differences in thermal performance [12]. The counter-flow design achieved approximately 76.23% thermal enhancement at Reynolds number (Re) = 1, compared to 70.07% for the parallel-flow configuration under identical conditions [12]. This performance advantage persisted across various flow conditions, with the counter-flow configuration exhibiting superior overall performance and more uniform temperature distribution [12].

Table 1: Performance comparison between counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations

| Performance Metric | Counter-flow | Parallel-flow | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal enhancement at Re = 1 | 76.23% | 70.07% | [12] |

| Maximum temperature efficiency in air-to-air units | 70-90% | 50-70% | [13] |

| Temperature distribution | More uniform | Less uniform | [12] |

| Optimal performance index (η) at Re = 1, φ = 0.025 | 33972.3 (predicted) 34020.03 (actual) | Lower than counter-flow | [12] |

The thermodynamic advantage of counter-flow configurations becomes particularly evident when examining the temperature distribution along the heat exchanger length. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analysis has demonstrated that longer heat exchangers improve effectiveness by allowing more time for thermal exchange and larger heat exchange surface area [14]. In these extended configurations, the inherent advantage of counter-flow designs becomes more pronounced, with these units maintaining higher temperature differences across the entire length compared to parallel-flow units [14]. This characteristic is especially valuable in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes requiring precise temperature control along the entire reaction path.

Table 2: LMTD calculation examples for counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations

| Configuration | Hot Fluid (°C) | Cold Fluid (°C) | ΔT₁ (°C) | ΔT₂ (°C) | LMTD (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel-flow | Inlet: 80, Outlet: 60 | Inlet: 0, Outlet: 20 | 80 | 40 | 57.7 | [10] |

| Counter-flow | Inlet: 80, Outlet: 40 | Inlet: 20, Outlet: 50 | 30 | 20 | 24.7 | [9] |

| Steam heating water (counter-flow) | 134 (constant) | Inlet: 20, Outlet: 50 | 114 | 84 | 98.2 | [10] |

Advanced LMTD Formulations and Modern Challenges

Limitations of Classical LMTD Method

While the classical LMTD method provides a robust foundation for heat exchanger analysis, it often fails to accurately model real-world systems where its underlying assumptions are violated. This limitation is particularly evident in systems using zeotropic refrigerant mixtures, where temperature glide during phase change and significant pressure drops along the flow path create complex thermodynamic behavior [11]. Conventional methods that omit pressure drop and temperature glide effects can yield substantial errors—often underestimating or overestimating the mean temperature difference and overall effectiveness by more than 10% in counter-flow and similar margins in parallel-flow arrangements under strong glide conditions [11].

The problem with classical approaches is that they assume idealized conditions: constant fluid properties, negligible pressure drop, and isothermal phase change [11]. In pharmaceutical applications, where complex fluid mixtures and precise thermal control are common, these assumptions are frequently invalid. Zeotropic mixtures experience temperature glide during phase change, where the saturation temperature varies with vapor quality even under constant pressure, while pressure drop further shifts the saturation point, causing refrigerant temperature to vary along the flow direction [11]. These factors create significant departures from the constant-temperature phase change assumptions inherent to classical models.

Modified LMTD and ε-NTU Approaches

Recent research has addressed these limitations through analytical reformulations of both LMTD and effectiveness-NTU (ε-NTU) methods that explicitly incorporate pressure drop and temperature glide effects [11]. These modified approaches introduce dimensionless correction parameters that quantify glide intensity and pressure-induced saturation temperature variation, providing closed-form solutions for parallel-flow, counter-flow, and cross-flow configurations [11]. The modified effectiveness-NTU method offers particularly significant improvements, with corrections reaching up to 40% depending on glide magnitude and heat capacity ratio [11].

In cross-flow systems, which are common in pharmaceutical ventilation and environmental control systems, the combined influence of glide and pressure drop causes non-monotonic deviations reaching 30% under high-glide, high-pressure-drop conditions [11]. A curvature-based evaluation of temperature profiles offers additional insight into the thermodynamic asymmetries that distort classical predictions [11]. This advanced framework applies to both single- and two-phase regimes, providing a unified, accurate, and analytically tractable tool for heat exchanger design under realistic pharmaceutical processing conditions [11].

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

CFD Analysis of Heat Exchanger Performance

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing heat exchanger performance, enabling researchers to visualize temperature distributions, flow patterns, and thermal gradients that are difficult to measure experimentally. One established protocol involves employing 2D CFD simulations to analyze the impact of pipe length on efficiency and LMTD of double-pipe heat exchangers while maintaining constant flow rates, inlet temperatures, and fluid properties [14]. This methodology reveals that heat exchanger efficiency and LMTD in both parallel and counter-flow configurations are significantly influenced by pipe length, with longer heat exchangers improving heat transfer effectiveness by allowing more time for thermal exchange, larger heat exchange surface area, and achieving more uniform temperature distribution [14].

The CFD methodology typically involves creating a detailed geometric model of the heat exchanger, generating a appropriate mesh, applying boundary conditions (inlet temperatures, flow rates, material properties), solving the governing equations for fluid flow and heat transfer (Navier-Stokes equations and energy equation), and validating results against experimental data [14] [12]. For advanced applications involving nanofluids or specialized materials, additional characterization of fluid properties may be necessary. These simulations provide invaluable insights for optimizing heat exchanger configurations for specific pharmaceutical applications where space constraints and thermal efficiency must be balanced.

Experimental Analysis of Air-to-Air Heat Exchangers

Experimental evaluation of heat exchanger performance typically involves precisely controlled laboratory setups that measure thermal efficiency under balanced and unbalanced flow conditions. A representative experimental protocol for air-to-air heat exchangers involves testing units like the Recair Sensitive RS160, Core ERV366, and custom prototypes under both balanced and unbalanced flow conditions while measuring temperature efficiency [13]. The experimental setup typically includes temperature sensors at all inlets and outlets, flow control valves, flow meters, data acquisition systems, and environmental controls to maintain consistent testing conditions [13].

The standard experimental procedure involves:

- Establishing balanced flow conditions where exhaust and supply air mass flows are balanced within 3%

- Systematically creating unbalanced conditions by varying flow rates beyond the 3% threshold

- Measuring temperature efficiency as η = (Tsupplyout - Tsupplyin) / (Texhaustin - Tsupplyin)

- Repeating measurements across a range of flow rates and imbalance ratios

- Comparing results against theoretical predictions [13]

These experiments have demonstrated that flow imbalance significantly impacts thermal efficiency, with commercially available units like the RS160 maintaining performance better than others as flow rates increase [13]. Even small differences in thermal efficiency under balanced airflow conditions transform into significant differences under unbalanced conditions, highlighting the importance of testing under realistic operating scenarios [13].

Nanofluid and Ionanofluid Thermal Performance Testing

Advanced thermal performance testing involving nanofluids and ionanofluids follows more specialized protocols to evaluate their enhanced heat transfer capabilities. One recently developed methodology focuses on a three-chambered parallel plate heat exchanger using cold ionanofluid (a mixture of graphene nanoparticles and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate ionic liquid) in the top and bottom channels and hot oil in the middle channel [12]. The experimental approach involves solving the governing Navier-Stokes and energy balance equations numerically using the finite element method while observing the impact of different Reynolds numbers and solid concentrations on fluid velocity and temperature fields [12].

This protocol includes comprehensive data analysis using the surface response method, including ANOVA, sensitivity analysis, and optimization testing [12]. The methodology enables researchers to calculate key performance parameters such as heat transfer rates, pressure drop, fanning friction, synergy number, thermal enhancement efficiency, and thermal performance index [12]. For pharmaceutical applications where precise temperature control of complex fluids is required, such advanced testing provides critical data for system optimization.

Research Reagents and Technical Tools for Thermal Analysis

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for heat exchanger performance studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionanofluids | Enhanced heat transfer fluids with improved thermal properties | Graphene nanoparticles in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate ionic liquid | [12] |

| Nanofluids | Working fluids with suspended nanoparticles for improved thermal conductivity | Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) in water | [12] |

| Ionic liquids | Base fluids with unique thermal characteristics for specialized applications | Trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium-based ionic liquids | [12] |

| Thermal oils | Standard heat transfer medium for comparative studies | Mineral-based or synthetic thermal oils | [12] |

| Zeotropic refrigerants | Complex fluid mixtures for studying temperature glide effects | Commercial refrigerant blends | [11] |

| Plate materials | Heat transfer surfaces with specific thermal properties | Stainless steel plates (0.2mm thickness) | [12] |

The comprehensive analysis of temperature gradients and LMTD reveals significant implications for pharmaceutical thermal system design and optimization. The demonstrated thermodynamic advantage of counter-flow configurations provides a fundamental design principle for reactors, heat recovery systems, and temperature control units throughout pharmaceutical manufacturing processes. The consistent findings across multiple studies—that counter-flow arrangements achieve higher temperature efficiency, more uniform temperature distribution, and superior overall performance—offer valuable guidance for engineers designing systems where precise thermal management directly impacts product quality, reaction efficiency, and process economics [14] [13] [12].

Advanced LMTD formulations that account for real-world complexities like temperature glide and pressure drop represent a significant evolution in heat exchanger modeling, particularly relevant to pharmaceutical applications involving complex fluid mixtures [11]. The integration of CFD analysis with experimental validation creates a powerful methodology for optimizing heat exchanger performance before physical prototyping [14] [12]. Furthermore, emerging heat transfer fluids like ionanofluids offer promising avenues for enhancing thermal performance in specialized applications where conventional fluids reach their limitations [12]. These combined advances in fundamental understanding, modeling capabilities, and materials science continue to push the boundaries of what's possible in pharmaceutical thermal system design, enabling more efficient, precise, and reliable temperature control in critical manufacturing processes.

Characteristic Flow Patterns and Swirling Effects in Different Geometries

The thermal performance of reactor systems is fundamentally governed by their internal flow patterns and heat transfer characteristics. Within the context of advanced reactor design, the comparison between counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations is critical, as the choice directly impacts efficiency, safety, and operational stability. This guide provides an objective comparison of these configurations, with a specific focus on characteristic flow patterns—particularly swirling effects—and their consequent thermal-hydraulic performance. The analysis is framed within broader research on nuclear reactors and chemical processes, leveraging experimental data and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) studies to offer a definitive resource for researchers and engineers in drug development, chemical engineering, and nuclear energy.

Comparative Analysis: Counter-Flow vs. Parallel-Flow Configurations

The primary distinction between counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations lies in the relative direction of the hot and cold fluid streams. In a parallel-flow system, both fluids move in the same direction, leading to a large temperature difference at the inlet that decreases along the flow path. In a counter-flow system, the fluids move in opposite directions, maintaining a more uniform temperature difference across the entire heat exchanger length, which enables higher thermal efficiency [6] [15].

Table 1: Comparative Thermal-Hydraulic Performance of Flow Configurations

| Performance Parameter | Parallel-Flow Configuration | Counter-Flow Configuration | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Lower; decreasing temperature gradient along flow path [6]. | Higher; maintains a more consistent temperature gradient [6] [16]. | |

| Outlet Temperature Approach | Cold fluid outlet temperature cannot approach hot fluid inlet temperature closely [15]. | Cold fluid can exit at a temperature higher than the hot fluid outlet temperature [15] [16]. | |

| Temperature Distribution | Can lead to higher temperature gradients and localized hot spots [6]. | Promotes more uniform temperature distribution, reducing thermal stress [6]. | |

| Flow Dynamics & Swirling | Generates intense swirling in fuel pipes, enhancing local heat transfer but increasing mechanical stress [6]. | Reduces swirling effects, leading to more uniform flow velocity and lower mechanical stress [6]. | |

| System Complexity | Generally simpler flow path [6]. | Can involve more complex header design [6]. | |

| Typical Applications | Suitable for processes requiring gentle heating/cooling (e.g., pharma, food) [15]. | Used in high-efficiency applications (e.g., nuclear reactors, cryogenics) [6] [17]. |

Beyond the fundamental differences in flow direction, the resulting flow patterns, especially swirling, critically influence system performance. Swirling flow is a secondary motion characterized by fluid rotation around the main axis of flow. It can be intentionally induced by devices like twisted tape inserts to enhance heat transfer by disrupting the boundary layer [18], or it can occur unintentionally due to inlet geometry, as seen in some reactor designs [6].

In a Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR) mini demonstrator study, CFD analysis revealed that the flow configuration directly impacts the intensity and effect of swirling:

- Parallel-Flow: The fuel enters the pipes at a sharp angle with high momentum, generating intense swirling. This enhances local, turbulent heat transfer but simultaneously increases mechanical stress on components and can lead to uneven wear [6].

- Counter-Flow: The fuel takes an extended path through the collection zone before entering the pipes. This path significantly reduces swirling effects, resulting in a more uniform velocity profile and lower mechanical stresses, thereby enhancing structural longevity [6].

The benefit of reduced swirling in counter-flow configurations is a key factor in its favor for applications where equipment safety and durability are paramount, such as in nuclear reactors.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To objectively compare the performance of different flow geometries, researchers employ rigorous experimental and computational protocols. The following methodologies are commonly cited in the literature.

Protocol 1: Comparative Thermal-Hydraulic CFD Analysis

This protocol, derived from a study on a Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR), uses CFD to directly compare counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations within the same geometry [6].

- 1. Objective: To analyze heat transfer characteristics, velocity distribution, temperature gradients, and swirling effects for both configurations.

- 2. Computational Model Setup:

- Geometry: A 1/4 sector of the reactor core is modeled leveraging geometric symmetry to conserve computational resources.

- Mesh: A structured mesh is generated, with refinement applied near pipe walls to resolve boundary layers.

- Fluids Model: The liquid metal coolant (e.g., liquid lead) is modeled accounting for its uniquely low Prandtl number. A variable turbulent Prandtl number model is used, based on the empirical correlation by Kays:

Prt = 0.85 + 0.7 / Pet, wherePetis the turbulent Peclet number [6].

- 3. Boundary Conditions:

- Inlet: Mass flow inlet conditions are defined for coolant and fuel.

- Outlet: Pressure outlet conditions are set.

- Walls: No-slip conditions and constant heat flux are applied.

- 4. Simulation & Analysis:

- The Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations are solved with an appropriate turbulence model.

- Post-processing quantifies key parameters: temperature fields, velocity vectors (to identify swirling), wall shear stress (to infer mechanical stress), and overall heat transfer coefficients.

Protocol 2: Experimental Heat Transfer Enhancement with Pulsating Flow

This experimental protocol investigates the compound effect of flow configuration and active flow pulsation on heat exchanger performance [17].

- 1. Objective: To determine the heat transfer enhancement and coefficient of performance (COP) improvement achieved by pulsating flow in a tube-in-tube heat exchanger.

- 2. Experimental Setup:

- Apparatus: A tube-in-tube heat exchanger test rig is integrated with a pulsation generation system.

- Instrumentation: Thermocouples measure inlet and outlet temperatures of both hot and cold streams. Flow meters monitor flow rates, and pressure transducers measure pressure drops.

- 3. Experimental Procedure:

- Baseline Test: The system is first tested with continuous parallel flow to establish a baseline.

- Configuration Tests: Tests are repeated with (a) continuous counter-flow and (b) counter pulsating flow.

- Data Recording: For each test, temperatures, flow rates, and pressure drops are recorded under steady-state conditions.

- 4. Data Analysis:

- Parameters calculated include:

- Overall heat transfer coefficient (U)

- Sensible heat rejection

- Heat exchanger effectiveness

- Coefficient of Performance (COP)

- Performance of continuous counter-flow and counter pulsating flow are compared against the parallel-flow baseline.

- Parameters calculated include:

Protocol 3: Solid-Liquid Mixing in a Swirling Flow Reactor (SFR)

This protocol utilizes CFD to study the mixing capacities of a novel Swirling Flow Reactor, relevant for chemical processes like heterogeneous catalysis [19].

- 1. Objective: To assess the effectiveness of particle suspension and mixing homogeneity in a reactor using swirling flow technology.

- 2. Computational Model:

- Multiphase Approach: The Eulerian-Eulerian (E-E) approach is coupled with the Kinetic Theory of Granular Flow (KTGF) to model the dense solid-liquid suspension.

- Turbulence Model: The RNG k-ε model is applied for its proven effectiveness in simulating turbulent swirling flows.

- Geometry: A specially designed reactor inlet nozzle forms a Coanda wall jet to wash particles from the bottom.

- 3. Analysis:

- Mixing Homogeneity: The degree of mixing is quantified by a homogeneity index (H) derived from the axial particle distribution.

- Flow Structures: Spectral Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (SPOD) is used to identify and reconstruct dominant coherent vortex structures, such as the double helical vortex core, which are responsible for the mixing.

Visualization of Flow Patterns and Performance

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental differences in flow configuration and the associated swirling phenomena that govern thermal performance.

Fundamental Flow and Temperature Profiles

Swirling Flow Patterns and Thermal Impact

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental and computational studies provide quantitative data on the performance differences between flow configurations and the impact of flow intensification techniques.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Enhancement with Pulsating Counter-Flow Data from experimental study on tube-in-tube heat exchanger [17]

| Performance Metric | Continuous Parallel Flow (Baseline) | Continuous Counter Flow | Counter Pulsating Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid Temperature Reduction | Baseline | 10% improvement | 20% improvement |

| Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient (U) | Baseline | 57.5% increase | 75% increase |

| Sensible Water Heat Rejection | Baseline | 10.03% increase | 19.78% increase |

| Effectiveness | Baseline | 4.55% increase | 10.6% increase |

| Coefficient of Performance (COP) | Baseline | 4.52% increase | 13.4% increase |

Table 3: Swirling Flow Intensifier Performance Data from studies on heat transfer intensification [18]

| Parameter | Standard Pipe (No Swirler) | Channel with Tape Swirler | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friction Factor (λ) | Baseline | Significantly higher | Depends on Re and swirler geometry (s/d) [18]. |

| Nusselt Number (Nu) | Baseline | Can be doubled or more | Heat transfer enhancement ratio depends on Re, Pr, and s/d [18]. |

| Effectiveness Criterion | 1.0 | > 1.0 | Evaluated based on combined heat transfer increase and pressure drop penalty [18]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Flow & Heat Transfer Studies

| Item | Function & Application | Example Context / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Metals (e.g., Lead, LBE) | High-temperature reactor coolant. | Used in DFR studies for high thermal conductivity and low Prandtl number, posing unique modeling challenges [6]. |

| Tape Swirlers | Passive heat transfer intensifiers. | Twisted tape inserts create swirling flow to disrupt the thermal boundary layer, enhancing heat transfer in pipes [18]. |

| Eulerian-Eulerian Multiphase Model | CFD approach for solid-liquid mixing. | Models dense particle suspensions (e.g., 20 vol%) in chemical reactors by treating particles as a continuous phase [19]. |

| Kinetic Theory of Granular Flow (KTGF) | Supplementary model for particle dynamics. | Used with Eulerian-Eulerian models to account for particle-particle collisions in dense suspensions [19]. |

| Variable Turbulent Prandtl Model | CFD correction for low-Pr fluids. | Critical for accurate simulation of heat transfer in liquid metals, where the turbulent Prandtl number is not constant [6]. |

| Spectral Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (SPOD) | Data analysis method for flow structures. | Identifies and reconstructs dominant, coherent swirling vortices in turbulent flows from CFD or experimental data [19]. |

| RNG k-ε Turbulence Model | A common turbulence closure model in RANS CFD. | Applied for simulating turbulent swirling flows with a proven balance of accuracy and computational cost [19] [18]. |

The selection of flow configuration is a fundamental aspect of thermal reactor and heat exchanger design, directly impacting efficiency, operational stability, and capital cost. This guide provides a comparative analysis of counter flow and parallel flow arrangements across a spectrum of scales, from macro-scale industrial reactors to compact microchannel designs. Understanding the performance characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each configuration enables researchers and engineers to make informed decisions tailored to specific application requirements, whether in chemical processing, nuclear energy, drug development, or electronics cooling.

The thermal performance of these systems is governed by the temperature difference between hot and cold streams along the flow path. In parallel flow (or co-current flow), both fluids move in the same direction, leading to a large initial temperature difference that decreases exponentially along the length of the exchanger [1]. In counter flow (or countercurrent flow), fluids enter from opposite ends, maintaining a more uniform and favorable temperature gradient across the entire exchanger, which typically results in higher thermal efficiency [1]. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in flow direction and the resulting characteristic temperature profiles.

Fundamental Thermal Performance Comparison

The underlying flow mechanics of counter and parallel flow configurations create distinct thermal performance profiles. Quantitative data from various experimental studies consistently demonstrates the efficiency advantage of counter flow arrangements.

Table 1: Comparative Thermal-Hydraulic Performance of Flow Configurations

| Performance Metric | Counter Flow | Parallel Flow | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Rate Increase | +6.5% [20] | Baseline | Zigzag PCHE with LN/EG fluids |

| Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient (U) Increase | +57.5% (Standard)+75% (Pulsating) [17] | Baseline | Tube-in-Tube Heat Exchanger |

| Effectiveness (ɛ) Increase | +4.55% (Standard)+10.6% (Pulsating) [17] | Baseline | Tube-in-Tube Heat Exchanger |

| Fluid Temperature Reduction | 10% (Standard)20% (Pulsating) [17] | Baseline | Tube-in-Tube Heat Exchanger |

| Flow Uniformity & Stress | More uniform velocity profile, reduced mechanical stress [6] | Significant swirling effects, higher mechanical stress [6] | Dual Fluid Reactor (Liquid Lead Coolant) |

| Coefficient of Performance (COP) Increase | +4.52% (Standard)+13.4% (Pulsating) [17] | Baseline | Air Conditioning/Refrigeration System |

Key Performance Analysis

- Thermal Efficiency: The superior heat transfer performance of counter flow configurations is primarily due to the maintenance of a more favorable log mean temperature difference (LMTD) across the entire length of the heat exchanger. This allows for greater temperature changes in the fluids and more complete heat recovery from the hot stream [1].

- Flow Dynamics: In complex systems like nuclear reactors, parallel flow can induce significant swirling effects within fuel pipes due to entry at sharp angles with high momentum. Counter flow arrangements promote more uniform flow distribution, reducing mechanical stress on components and enhancing operational longevity [6].

- Performance Enhancement: The application of active techniques like pulsating flow can significantly augment the performance of both configurations, with counter flow systems showing greater absolute improvement in key metrics like overall heat transfer coefficient and effectiveness [17].

Macro-Scale Industrial Applications

At the macro-scale, flow configuration selection critically impacts the efficiency, safety, and economics of large industrial processes.

Nuclear Reactors: Dual Fluid Reactor Case Study

Advanced nuclear reactor designs like the Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR) represent a demanding application where thermal-hydraulic performance is paramount.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Materials in Nuclear Thermal-Hydraulics

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Lead/Lead-Bismuth Eutectic (LBE) | Primary coolant in advanced nuclear reactors [6] | Low Prandtl number (~0.025), high thermal conductivity, requires specialized modeling [6] |

| Molten Salt/Fuel Salt | Fuel carrier in dual-fluid reactor designs [6] | High-temperature operation, efficient heat transfer |

| Pd-Ag (Palladium-Silver) Alloy Membrane | Hydrogen-permeable membrane in reactor systems [21] | High hydrogen permeability/selectivity, good mechanical stability at high temperatures [21] |

| CuO/ZnO/Al₂O₃ Catalyst | Catalytic hydrogenation of CO to methanol [21] | Commercial methanol synthesis catalyst |

Experimental Protocol: Detailed Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations are used to analyze thermal-hydraulic behavior. The model incorporates a variable turbulent Prandtl number to accurately capture heat transfer in liquid metal coolants with low Prandtl numbers. The governing equations (mass, momentum, and energy conservation) are solved using finite-volume methods, often leveraging geometric symmetry to optimize computational resources [6].

Findings: In the DFR mini demonstrator, the counter flow configuration yielded higher heat transfer efficiency and a more uniform flow velocity, while simultaneously reducing swirling and mechanical stresses compared to parallel flow. This translates to enhanced reactor safety and potential for longer component lifespan [6].

Chemical Process Industries: Methanol Synthesis Reactor

The flow configuration in chemical reactors directly influences conversion efficiency, catalyst life, and product yield.

Experimental Protocol: A one-dimensional dynamic plug flow model for a two-stage hydrogen permselective membrane reactor was developed, incorporating catalyst deactivation kinetics. The model compares co-current (parallel) and counter-current flow of fresh synthesis gas in the tube side relative to the reacting material in the shell side [21].

Findings:

- Counter-Current Configuration: Achieved a higher conversion of CO and a higher hydrogen permeation rate through the Pd-Ag membrane. This configuration provides more hydrogen in the later sections of the reactor where it is most needed to shift the equilibrium-limited reactions [21].

- Co-Current Configuration: Resulted in longer catalyst life by maintaining higher activity levels, as hydrogen is provided more abundantly in the initial reactor sections [21].

The choice between configurations thus represents a trade-off between maximum conversion efficiency and catalyst longevity. The following workflow diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting a flow configuration in industrial-scale applications.

Meso and Micro-Scale Applications

As system dimensions decrease to the micro-scale, the fundamental principles of flow configuration remain valid, but additional physical phenomena and constraints become significant.

Printed Circuit Heat Exchangers

Printed Circuit Heat Exchangers are compact, diffusion-bonded heat exchangers with channel diameters typically between 0.5 mm and 2 mm, finding applications in LNG vaporization, supercritical CO₂ cycles, and aerospace systems [20] [22].

Experimental Protocol: Performance evaluation of a zigzag PCHE under ultra-low temperature conditions using Liquid Nitrogen (LN) and Ethylene Glycol (EG) as working fluids. Local temperature distributions and the effect of varying inlet mass flow rates were investigated, comparing both parallel and counter flow conditions [20].

Findings: Under counter flow conditions, the heat transfer rate and vaporization effect increased by 6.5% and 6.1%, respectively, compared to parallel flow. The internal temperature distribution was also found to be biased toward the hot side [20].

Microchannel Heat Exchangers

Microchannel Heat Exchangers (MCHXs) are fluidic devices with channels of hydraulic diameter below 1 mm, used in microelectronics cooling, micro-reactors, and fuel cells [23] [24]. At this scale, non-continuum effects can become important.

Experimental Protocol: Numerical investigation of a counter flow microchannel heat exchanger (CFMCHE) using a finite-volume method and the SIMPLE algorithm. The analysis includes slip flow boundary conditions (velocity-slip and temperature jump) at the channel walls, which are significant in micro-scale flows characterized by Knudsen numbers (Kn) in the range 0.001 ≤ Kn ≤ 0.1 [23].

Findings:

- The effectiveness of the CFMCHE decreases with increasing Reynolds number (Re), Knudsen number (Kn), and aspect ratio (α) [23].

- Nusselt number (Nu), indicative of convective heat transfer performance, decreases with increasing Knudsen number due to the temperature jump at the wall [23].

- Unlike macro-scale heat exchangers, using a higher conductivity material does not continually increase effectiveness. For conductivity ratios (Kr) above a certain value (e.g., Kr > 90), effectiveness becomes independent of wall material [23].

Table 3: Key Parameters and Their Effects in Microchannel Heat Exchangers

| Parameter | Effect on Performance | Design Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Knudsen Number (Kn) | ↑ Kn → ↓ Effectiveness, ↓ Nusselt Number [23] | Critical in rarefied gas flows; dictates the need for slip-flow models. |

| Thermal Conductivity Ratio (Kr) | ↑ Kr → ↑ Effectiveness, plateaus after Kr ~ 90 [23] | Material selection beyond a certain conductivity offers diminishing returns. |

| Reynolds Number (Re) | ↑ Re → ↓ Effectiveness, ↑ Pressure Drop [23] [24] | Trade-off between heat transfer and pumping power. |

| External Heat Transfer | Can increase or decrease fluid effectiveness [24] | Requires careful thermal isolation or integration in system design. |

The comparative analysis across scales confirms the general thermal performance superiority of counter flow configurations in most applications, achieving 5-75% higher efficiency metrics depending on the system and operating conditions. However, parallel flow retains relevance where simpler mechanical design, mitigation of initial thermal stress, or specific catalyst lifetime requirements are prioritized [1] [21].

The selection of an optimal flow configuration is a multi-faceted decision. As systems scale down, additional factors like slip flow, axial conduction, external heat transfer, and fabrication constraints become increasingly critical [23] [24]. Future trends point toward the use of hybrid configurations and active enhancement techniques like pulsating flow, combined with advanced modeling and optimization using machine learning, to push the performance boundaries of both counter and parallel flow systems across all scales.

Implementation and Analysis: CFD, Experimental Methods, and Pharmaceutical Applications

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for High-Fidelity Thermal-Hydraulic Simulation

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as an indispensable tool for high-fidelity thermal-hydraulic analysis in advanced nuclear reactor systems. By solving complex conservation equations for mass, momentum, and energy, CFD provides unprecedented insight into phenomena that are difficult or impossible to capture with traditional system codes. This capability is particularly valuable for optimizing heat exchanger configurations, where the choice between parallel and counter-flow arrangements significantly impacts overall reactor safety and efficiency. Within the context of Generation IV nuclear systems, including Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) and advanced concepts like the Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR), CFD enables researchers to virtually prototype designs, identify thermal hotspots, and validate performance before physical testing [6] [25]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of CFD applications for analyzing parallel and counter-flow configurations in nuclear thermal-hydraulic systems, supported by experimental validation data and detailed methodological approaches.

Theoretical Foundations: Flow Configuration Physics

Fundamental Flow Configuration Characteristics

In thermal-hydraulic systems, the relative direction of fluid streams fundamentally determines heat transfer performance. Parallel flow (or cocurrent flow) configurations involve both hot and cold fluids moving in the same direction, while counter-flow (or countercurrent) configurations arrange fluids to move in opposite directions [1]. This directional difference creates distinct temperature gradient profiles along the heat exchange path.

In parallel flow, the maximum temperature difference exists only at the inlet, decreasing exponentially along the flow path as fluids approach thermal equilibrium. This configuration inherently limits the maximum possible temperature change to approximately 50% of the initial temperature difference between fluids [26]. The rapidly diminishing driving force for heat transfer makes parallel flow less efficient for applications requiring substantial heat recovery.

In counter-flow, the temperature difference between hot and cold fluids remains more consistent throughout the entire exchange length. While the initial temperature difference may be smaller than in parallel flow, this differential is maintained as the hot fluid continuously encounters progressively colder fluid from the opposite direction [26]. This sustained driving force enables counter-flow configurations to theoretically achieve up to 100% of the initial temperature differential, making them significantly more efficient for high-performance applications [26].

Implications for Nuclear Reactor Applications

In nuclear systems, these fundamental characteristics translate directly to operational performance and safety margins. The more uniform temperature distribution in counter-flow configurations reduces thermal stresses and minimizes the risk of localized hotspots that can compromise structural materials [6] [1]. Additionally, the higher efficiency of counter-flow arrangements allows for more compact heat exchanger designs or reduced pumping power for equivalent heat transfer duties—critical considerations in nuclear plant economics and safety.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Quantitative Findings

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics between parallel and counter-flow configurations

| Performance Parameter | Parallel Flow | Counter Flow | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Moderate | 20-30% higher [6] | DFR mini demonstrator with liquid lead coolant [6] |

| Temperature Distribution | Gradual equalization with higher gradient at inlet | Consistent gradient maintained along entire length [1] | Industrial shell and tube heat exchangers [1] |

| Flow Uniformity | Moderate, with localized swirling | More uniform velocity distribution [6] | DFR mini demonstrator CFD simulations [6] |

| Swirling Effects | Intense in specific fuel pipes | Significantly reduced [6] | DFR with liquid metal coolant [6] |

| Mechanical Stress | Higher due to swirling and temperature differentials | Reduced stress on components [6] | DFR structural analysis [6] |

| Thermal Stress Risk | Higher at inlet due to dramatic temperature differential | More consistent wall temperatures [1] | Industrial heat exchanger applications [1] |

| Hotspot Risk | Elevated potential for localized overheating | Reduced risk due to stable temperature gradient [6] | Dual Fluid Reactor core analysis [6] |

Table 2: Numerical modeling considerations for different coolant types

| Modeling Aspect | Liquid Metal Coolants | Water Coolants | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prandtl Number | Uniquely low (e.g., liquid lead) [6] | Higher | Requires specialized turbulence models |

| Turbulent Prandtl Model | Variable Prandtl number model essential [6] | Standard models often sufficient | Accurate prediction of thermal boundary layer |

| Validation Case | DFR mini demonstrator [6] | MOTEL SMR facility [25] | Different validation approaches required |

| Near-Wall Treatment | Critical for heat transfer accuracy | Less sensitive with higher Pr | Resolution requirements more demanding for liquid metals |

Recent research on the Dual Fluid Reactor mini demonstrator reveals that while both parallel and counter-flow configurations support efficient heat transfer, they exhibit distinct performance characteristics. Counter-flow arrangements demonstrate approximately 20-30% higher heat transfer efficiency while simultaneously reducing swirling effects in fuel pipes by creating a more uniform flow velocity distribution [6]. This reduction in swirling directly translates to lower mechanical stresses on reactor components, potentially extending operational lifespan.

The MOTEL test facility experiments for Small Modular Reactors further highlight the importance of flow configuration selection, demonstrating that significant power gradients between core regions can provoke substantial cross-flow mixing effects, particularly in the upper core section [25]. These phenomena are more readily managed in counter-flow configurations, which naturally maintain more stable temperature gradients throughout the core region.

CFD Methodologies for Nuclear Thermal-Hydraulics

Governing Equations and Physical Models

CFD analysis of nuclear thermal-hydraulic systems solves the fundamental conservation equations of fluid dynamics and energy transport. The time-averaged mass conservation equation is expressed as:

[ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial (\rho Ui)}{\partial xi} = 0 ]

The momentum conservation equation follows:

[ \frac{\partial (\rho Ui)}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial (\rho Uj Ui)}{\partial xj} = -\frac{\partial P}{\partial xi} + \frac{\partial}{\partial xj} \left[ \mu \left( \frac{\partial Ui}{\partial xj} + \frac{\partial Uj}{\partial xi} \right) - \rho \overline{u'i u'j} \right] + \rho g_i ]

The energy conservation equation completes the system:

[ \frac{\partial (\rho T)}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial (\rho Uj T)}{\partial xj} = \frac{\partial}{\partial xj} \left[ \left( \frac{\lambda}{Cp} + \frac{\mut}{\sigmat} \right) \frac{\partial T}{\partial xj} - \rho \overline{u'j T'} \right] ]

For liquid metal coolants with characteristically low Prandtl numbers, standard turbulence models require modification. The DFR simulations incorporated a variable turbulent Prandtl number model using the Kays correlation:

[ Prt = 0.85 + \frac{0.7}{Pet} \quad \text{with} \quad Pet = \frac{vt}{v} Pr ]

This approach has demonstrated improved prediction accuracy for molten lead and lead-bismuth eutectic coolants compared to constant Prandtl number models [6].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Table 3: CFD validation experiments for nuclear thermal-hydraulic applications

| Experimental Facility | Reactor Type | Key Measurements | Validation Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFR Mini Demonstrator [6] | Dual Fluid Reactor | Temperature gradients, velocity profiles, swirling effects | Liquid metal coolant behavior, flow configuration performance |

| MOTEL Test Facility [25] | Small Modular Reactor (SMR) | Core temperature distribution, cross-flow mixing | Asymmetric power distribution effects, natural circulation |

| NACIE-UP Loop [6] | Lead-Bismuth Eutectic System | Heat exchanger performance, temperature stability | Liquid metal counter-flow configuration |

| Vertical Dry Cask Simulator [27] | Dry Storage Cask | Peak cladding temperature, air mass flow rate | Spent fuel storage thermal performance |

CFD validation for nuclear applications requires specialized "CFD-grade" experiments that provide comprehensive data matching the predictive capabilities of modern simulations. According to OECD/NEA guidelines, such experiments must include well-documented initial and boundary conditions, local measurements of multiple flow variables, and thorough uncertainty quantification [28]. The U.S. NRC's validation of ANSYS Fluent for dry cask simulations exemplifies this approach, incorporating uncertainty quantification following ASME V&V 20-2009 standards and demonstrating favorable agreement for peak cladding temperature predictions within calculated validation uncertainties [27].

The European McSAFER research project employed the MOTEL integral test facility to generate validation data for SMR-relevant conditions, imposing asymmetric and ring-shaped radial core power distributions to provoke cross-flows in buoyancy-driven coolant flow [25]. These experiments provided valuable data for validating both CFD and subchannel codes, with ANSYS CFX simulations showing good agreement with measurements while revealing additional details of core flow characteristics.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Nuclear CFD

Table 4: Essential computational and experimental tools for nuclear thermal-hydraulic CFD

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFD Software | ANSYS Fluent [6] [27] | General-purpose thermal-hydraulic simulation | DFR analysis, dry cask simulations [6] [27] |

| CFD Software | ANSYS CFX [25] [29] | Specialized for nuclear applications | MOTEL facility simulation, MNR analysis [25] [29] |

| System Codes | RELAP5 [29] | System-level safety analysis | Coupled with CFD for boundary conditions |

| System Codes | CATHARE [29] | System-level thermal-hydraulics | Whole plant transient analysis |

| Subchannel Codes | CTF [25] | Core-level thermal analysis | SMR core design validation |

| Experimental Facilities | MOTEL Test Facility [25] | Integral SMR performance testing | Asymmetric power distribution studies |

| Experimental Facilities | NACIE-UP [6] | Liquid metal heat transfer | Counter-flow configuration validation |

| Turbulence Models | Variable Prandtl Model [6] | Liquid metal heat transfer | DFR with molten lead coolant |

| Turbulence Models | SST Model [29] | Near-wall accuracy | MNR pool temperature simulation |

The selection of appropriate computational tools depends heavily on the specific analysis requirements. For detailed component-level analysis where complex flow phenomena dominate, CFD provides the highest fidelity and is increasingly required for regulatory submissions, as demonstrated in NUREG-2238 for dry cask storage systems [27]. For system-level analysis or rapid scoping studies, system codes and subchannel approaches offer practical alternatives, though with limitations in capturing complex three-dimensional phenomena.

Recent advances have focused on coupling methodologies, where CFD provides detailed component models that inform boundary conditions for system-level codes. This approach was demonstrated in the analysis of the NACIE-UP facility through a novel CFX-RELAP5 code coupling [6], leveraging the strengths of both approaches while mitigating their respective limitations.

CFD has matured into an essential technology for high-fidelity thermal-hydraulic simulation in nuclear applications, providing unique insights into complex flow phenomena that directly impact reactor safety and performance. The comparative analysis of parallel and counter-flow configurations demonstrates that while both arrangements can achieve efficient heat transfer, counter-flow configurations generally offer superior performance through higher efficiency, reduced mechanical stresses, and more stable temperature distributions. These advantages are particularly valuable in advanced reactor systems utilizing liquid metal coolants, where accurate prediction of thermal phenomena requires specialized turbulence modeling approaches.

Validation remains paramount for building confidence in CFD predictions, with "CFD-grade" experiments providing the essential foundation for demonstrating predictive capability within quantified uncertainty bounds. As nuclear systems continue to evolve toward more compact and efficient designs, the role of CFD in optimizing thermal-hydraulic performance will only increase, supported by ongoing development of specialized physical models, improved numerical methods, and comprehensive experimental validation programs.

Advanced Modeling Techniques for Low Prandtl Number Fluids and Molten Metals

The thermal-hydraulic design of advanced nuclear reactors, such as the Generation IV Dual Fluid Reactor (DFR), relies heavily on accurate performance predictions for heat exchangers and core components. These systems often utilize liquid metals or molten salts as coolants, characterized by their low Prandtl numbers, and operate under either parallel or counter flow configurations. The Prandtl number, representing the ratio of momentum diffusivity to thermal diffusivity, is a key fluid property that drastically alters heat transfer characteristics. For liquid metals, Prandtl numbers are typically on the order of 10-2, resulting in thermal boundary layers that are significantly thicker than their momentum counterparts. This review provides a comparative analysis of advanced modeling techniques essential for simulating these complex fluids, with a specific focus on their application in evaluating the thermal performance of counter-flow versus parallel-flow configurations in nuclear reactor systems.

Thermal Performance Comparison: Counter-Flow vs. Parallel-Flow Configurations

The choice between counter-flow and parallel-flow arrangements presents a significant design trade-off, impacting heat transfer efficiency, temperature distributions, and mechanical stresses within reactor components.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Comparative Thermal-Hydraulic Performance in a Dual Fluid Reactor Mini Demonstrator [6]

| Performance Parameter | Counter-Flow Configuration | Parallel-Flow Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer Efficiency | Higher | Lower |

| Flow Velocity Uniformity | More uniform | Less uniform |

| Swirling Effects in Fuel Pipes | Significantly reduced | Intense, leading to enhanced local heat transfer but increased mechanical stress |

| Temperature Gradient | Maintains a consistent, stable gradient | Gradual equalization, leading to a decreasing gradient along the flow path |

| Mechanical Stress on Components | Reduced | Increased due to swirling and potential for thermal fatigue |

| Risk of Localized Hotspots | Lower | Higher |

Fundamental Principles of Flow Configurations

The performance differences stem from fundamental thermodynamic principles. In a parallel-flow (or cocurrent) heat exchanger, both the hot and cold fluids enter from the same end and move in the same direction. This setup initially creates a large temperature difference, which rapidly decreases along the flow path as the fluids approach thermal equilibrium. This logarithmic temperature profile inherently limits the maximum potential temperature change to 50% of the initial differential [30].

In contrast, a counter-flow (or countercurrent) arrangement reverses the direction of one fluid stream. The hot fluid enters at one end and encounters the already-warmed cold fluid from the opposite end. While the initial temperature difference is smaller, this differential is maintained throughout the entire heat exchange process. As the hot fluid cools, it continuously interacts with progressively colder fluid, enabling a theoretical maximum cooling/heating potential of 100% of the initial temperature difference [30]. This leads to a more uniform temperature difference across the exchanger, enhancing overall thermal efficiency and reducing the risk of thermal stress caused by dramatic inlet temperature differentials [1].

Advanced Modeling Techniques for Low Prandtl Number Fluids

Accurately simulating the heat transfer behavior of liquid metals and molten salts requires moving beyond standard turbulence models, which are often calibrated for fluids like water with Prandtl numbers around unity.

Limitations of Standard Models

The Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) approach with the Simple Gradient Diffusion Hypothesis (SGDH) has been a standard practice in computational fluid dynamics (CFD). However, the SGDH is known to yield inaccurate results for low-Prandtl-number fluids because it does not adequately capture the physics of turbulent heat transport when thermal diffusion dominates over viscous effects [31]. This challenge is exacerbated in the mixed convection regime, crucial for passive heat removal in advanced reactors, where buoyancy effects significantly influence turbulence and heat transfer [32].

Advanced Turbulent Heat Flux Models

To overcome these limitations, several advanced modeling approaches have been developed:

Variable Turbulent Prandtl Number Model: This method replaces the constant turbulent Prandtl number typically used in SGDH with a variable one. For instance, the empirical correlation by Kays (

Prt = 0.85 + 0.7/Pet) has been successfully applied in CFD studies of liquid lead coolant in a DFR mini demonstrator, significantly improving the accuracy of heat transfer predictions [6].Algebraic Heat Flux Model (AHFM): The AHFM provides a more sophisticated framework for calculating the turbulent heat flux. Recent research has focused on developing a local formulation of the AHFM, where its coefficients are automatically computed from local turbulence parameters rather than global flow parameters like Reynolds number. This automatization is particularly advantageous for transient analyses or complex flow configurations and has been validated against Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) data, showing superior performance in predicting the mean temperature field of low-Prandtl-number fluids compared to the SGDH [31].

Data-Driven RANS Framework: The NEAMS Integration Research Project (IRP) has pioneered a data-driven (DD) framework for Reynolds stress and turbulent heat flux prediction based on polynomial tensor representation. This DD framework has demonstrated satisfactory performance over traditional k-τ models in both forced and mixed convection cases involving non-unitary Prandtl flows [32].

High-Fidelity Simulations

Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS): DNS resolves all turbulent scales without modeling, providing fundamental insight and benchmark data for model development. DNS is extensively used to study low- and high-Prandtl mixed convection in canonical flows, illuminating the effect of buoyancy on turbulence and heat transfer [32]. For multiphase flows, interface-resolved DNS is employed to analyze heat transport in systems like drop-laden liquid metal turbulence, capturing finite-size effects, deformation, and topological changes of interfaces [33].

First-Principles Molecular Dynamics (FPMD): FPMD simulations use quantum mechanical interactions to probe the thermophysical properties and microstructural evolution of molten salts from first principles. This technique has been effectively used, coupled with experimental validation, to investigate properties like density, specific heat capacity, viscosity, and ion diffusion coefficients in NaCl-KCl-CaCl2 (NKC) molten salts at high temperatures (873–1173 K), where experimental measurements face severe challenges due to increased corrosion and decreased data acquisition accuracy [34].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Validating advanced models requires high-quality experimental data. The following protocols outline key methodologies cited in contemporary research.

Protocol 1: Comparative Thermal-Hydraulic Analysis via CFD

This protocol was used to compare counter-flow and parallel-flow configurations in a Dual Fluid Reactor mini demonstrator (MD) [6].

- Geometric Modeling: Create a 3D model of the reactor core. To optimize computational resources, leverage geometric symmetry (e.g., simulating only a quarter of the full domain).

- Mesh Generation: Discretize the computational domain with a structured or unstructured mesh, ensuring sufficient resolution in boundary layers.

- Physics Setup:

- Fluid Properties: Define the liquid metal coolant (e.g., liquid lead) and fuel as materials with appropriate thermophysical properties.

- Boundary Conditions: Set mass flow inlets, pressure outlets, and thermal conditions for both fuel and coolant channels, ensuring directions are opposed for counter-flow and aligned for parallel-flow simulations.

- Turbulence and Heat Transfer Model: Select a Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) model. Critically, incorporate a variable turbulent Prandtl number model (e.g., the Kays correlation) to accurately capture the low-Prandtl-number heat transfer.

- Solution and Analysis: Run the simulation to a converged steady-state. Analyze results for temperature fields, velocity profiles, swirling effects, and heat transfer coefficients to compare the performance of the two configurations.

Protocol 2: Thermophysical Property Determination via FPMD and Experiment

This protocol describes a combined simulation and experimental approach to obtain high-temperature property data for molten salts, as applied to NKC salt [34].

- Sample Preparation: Procure high-purity (>99.5 wt%) salts. Mix in the desired molar ratio, load into a crucible, and heat above the melting point under an inert argon atmosphere for several hours to homogenize.

- Experimental Measurement:

- Thermal Analysis: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to determine the melting point and enthalpy of fusion.

- Specific Heat Capacity: Measure the isobaric specific heat capacity (

cp) experimentally within the accessible temperature range.

- FPMD Simulation:

- Setup: Construct a model system of the molten salt composition within a periodic simulation box.

- Calculation: Perform first-principles molecular dynamics simulations over the target temperature range (e.g., 873–1173 K).

- Property Extraction: From the trajectory, calculate properties such as density, specific heat capacity, viscosity, radial distribution functions, and ion self-diffusion coefficients.

- Validation and Data Supplementation: Compare FPMD results with experimental measurements to validate the method. Use the validated FPMD model to supplement experimental data at higher temperatures where measurements are challenging.

FPMD-Experimental Workflow for determining thermophysical properties of molten salts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials, Software, and Databases for Low-Prandtl-Number Fluid Research

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Lead / LBE | Low-Prandtl-number coolant (Pr ~ 0.025); high thermal conductivity. | Primary coolant in advanced fast reactors (e.g., DFR, LBE-cooled reactors) [6]. |

| Molten Salts (e.g., NKC) | Heat transfer and storage fluid; good thermal stability at high temperatures. | Coolant and fuel salt in Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs), thermal energy storage [34]. |

| Yamdb Database | An open database providing easily accessible thermophysical property correlations for liquid metals and molten salts [35]. | Rapid retrieval of temperature-dependent properties (density, viscosity) for CFD simulations and system design. |

| Algebraic Heat Flux Model (AHFM) | Advanced turbulence model for accurate prediction of turbulent heat flux in low-Prandtl-number fluids [31]. | Improving the accuracy of RANS-based CFD simulations for liquid metal coolant systems. |

| Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) | A high-fidelity simulation technique that resolves all scales of turbulence without modeling. | Generating benchmark data for model development and studying fundamental heat transfer mechanisms [33] [32]. |

| First-Principles Molecular Dynamics (FPMD) | A simulation method using quantum mechanical interactions to compute material properties from first principles. | Predicting thermophysical properties and microstructural evolution of molten salts at high temperatures [34]. |

The optimization of heat exchanger and reactor core designs for advanced nuclear systems hinges on a deep understanding of counter-flow and parallel-flow thermal performance. As demonstrated in studies of the Dual Fluid Reactor, counter-flow configurations generally offer superior heat transfer efficiency and more favorable thermal stress profiles. However, accurately predicting this performance for liquid metals and molten salts demands a move beyond standard CFD modeling techniques. The adoption of advanced approaches, such as variable Prandtl number models, Algebraic Heat Flux Models, and high-fidelity simulations like DNS and FPMD, is crucial for capturing the unique heat transfer characteristics of low-Prandtl-number fluids. The continued development and validation of these modeling techniques, supported by robust experimental data and specialized material databases, are essential for advancing the safety, efficiency, and reliability of next-generation nuclear reactors.

Model Selection Logic for simulating low-Prandtl-number fluid systems.

Experimental Setups and Validation Protocols in Research-Scale Reactors