Cross-Validation in Organic Chemistry: Foundational Principles, Methodological Applications, and Best Practices for Robust Analytical Methods

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation of analytical methods in organic chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Cross-Validation in Organic Chemistry: Foundational Principles, Methodological Applications, and Best Practices for Robust Analytical Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation of analytical methods in organic chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles defining cross-validation and its role within the method lifecycle. The scope covers methodological applications across chromatographic and ligand binding assays, strategic troubleshooting for method transfer and optimization, and comparative frameworks for assessing method equivalency and regulatory compliance. Synthesizing recommendations from global harmonization consortia and contemporary research, this resource aims to equip scientists with the practical knowledge to ensure data integrity and reliability in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research.

Understanding Cross-Validation: Core Concepts and Regulatory Landscape in Analytical Chemistry

In the realm of organic chemistry and drug development, ensuring the reliability of analytical methods and predictive models is paramount. This guide objectively compares three critical quality assurance processes: cross-validation, method transfer, and partial validation. Cross-validation primarily assesses the equivalence of two different methods or the same method across laboratories, ensuring result consistency. Method transfer qualifies a receiving laboratory to execute an existing validated method. Partial validation confirms the suitability of a modified, previously validated method. Understanding their distinct protocols, applications, and acceptance criteria is essential for robust analytical practices in research and regulatory submissions.

In organic chemistry research, particularly in pharmaceutical development, analytical methods undergo a lifecycle from development and validation to routine use and eventual transfer or modification. Validation is a continuous process, and cross-validation, method transfer, and partial validation represent specific, interrelated activities within this lifecycle [1]. These procedures ensure that methods produce reliable, reproducible data when applied to support pharmacokinetic studies, bioequivalence assessments, and reaction optimization [1] [2]. While they share the common goal of establishing method reliability, their purposes, protocols, and positions in the method lifecycle differ significantly. A clear understanding of these distinctions is crucial for researchers and scientists to maintain regulatory compliance and data integrity.

Core Definitions and Comparative Framework

What is Cross-Validation?

Cross-validation is a comparative process used to demonstrate the equivalence of results obtained under different testing conditions. According to bioanalytical guidelines, cross-validation is necessary when comparing the performance of two or more different analytical methods or when the same method is used in two or more different laboratories [2]. Its primary goal is to ensure that results from different sources are comparable and consistent. For instance, in a regulated environment, results from cross-validation studies should not differ by more than 15% for quality control samples [2].

In machine learning, which is increasingly applied to organic chemistry problems such as predicting reaction yields or optimal conditions, cross-validation is a statistical technique for evaluating how a predictive model will generalize to an independent dataset [3]. It is primarily used for model validation and selection to prevent overfitting. Common techniques include Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) and k-folds Cross-Validation [3].

What is Method Transfer?

Method transfer is "the documented process that qualifies a laboratory (the receiving unit) to use an analytical test procedure that originates in another laboratory (the transferring unit)" [4] [5]. It is a specific activity that allows the implementation of an existing, validated method in a new laboratory environment, whether internal or external [1]. The principle goal is to demonstrate that the method is appropriately transferred and remains validated at the receiving laboratory [1].

What is Partial Validation?

Partial validation is "the demonstration of assay reliability following a modification of an existing bioanalytical method that has previously been fully validated" [1]. The extent of validation required depends entirely on the nature and significance of the modification made to the original method [1] [2]. It can range from a single intra-assay precision and accuracy experiment to a nearly full validation [1].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Analytical Procedures

| Feature | Cross-Validation | Method Transfer | Partial Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Demonstrate equivalence between methods or laboratories [2]. | Qualify a receiving lab to perform an existing method [4]. | Confirm reliability after a method modification [1]. |

| Typical Trigger | Use of different methods for the same study; same method used across labs [2]. | Method moved from R&D to QC, or between manufacturing sites [5]. | Change in method conditions, matrix, or instrumentation [1] [2]. |

| Scope of Work | Comparison of results from two sets of conditions on identical samples [2]. | Documented process often involving comparative testing or co-validation [5]. | Risk-based evaluation of specific validation parameters [1]. |

| Key Outcome | Data comparability within pre-defined limits (e.g., ≤15% difference) [2]. | Receiving laboratory is qualified for routine use [4]. | Demonstrated suitability of the modified method [1]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Standard Protocols for Cross-Validation

The protocol for a cross-validation study involves analyzing the same set of quality control (QC) samples and incurred study samples under the different conditions being compared (e.g., two different methods or two laboratories) [2]. The results are then statistically compared. Acceptance criteria are not universally fixed but must be scientifically justified; a common benchmark is that results should not differ by more than 15% for QCs [2].

In machine learning for chemistry, k-folds cross-validation is a standard protocol. The dataset is partitioned into 'k' subsets of equal size. The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold. This process is repeated k times, with each fold used exactly once as the validation set. The results are then averaged to produce a single performance estimate [3]. This is computationally efficient and provides a robust measure of model performance.

Standard Protocols for Method Transfer

The protocol for method transfer requires a pre-approved plan detailing objectives, materials, analytical procedures, and acceptance criteria [4]. A common approach is comparative testing, where both the transferring and receiving laboratories analyze homogeneous samples from the same lot, and the results are compared [5]. Another streamlined strategy is co-validation, where the receiving laboratory is involved as part of the validation team from the beginning, performing the method validation simultaneously with the transferring lab. This integrates method validation and transfer into a single, accelerated activity [5].

Table 2: Example Method Transfer Acceptance Criteria (Chromatographic Assays)

| Performance Characteristic | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|

| Precision | Coefficient of variation (CV) within a pre-defined limit (e.g., ≤15%) [1]. |

| Accuracy | Results within a pre-defined percentage of the known value (e.g., ±15%) [1]. |

| System Suitability | Meets criteria set in the method (e.g., retention time, peak shape, resolution) [4]. |

| Intermediate Precision | Demonstration of precision by different analysts on different days [4]. |

Standard Protocols for Partial Validation

The protocol for partial validation is not fixed and is determined via a risk-based assessment of the change made. The parameters evaluated are selected based on the potential impacts of the modifications [1]. For example:

- A change to the mobile phase (e.g., a major pH change) may require re-assessment of specificity, accuracy, and precision [1].

- A change in sample preparation (e.g., from protein precipitation to solid-phase extraction) would likely require a partial validation of accuracy, precision, and recovery [1].

- A change in matrix or species may require evaluation of all parameters except for long-term stability [2].

Case Studies in Organic Chemistry Research

Cross-Validation in Photocatalytic Reaction Prediction

A 2025 study demonstrated cross-validation through domain adaptation in photocatalysis. Knowledge of the catalytic behavior of organic photosensitizers (OPSs) from photocatalytic cross-coupling reactions (source domain) was successfully transferred to improve predictions for a [2+2] cycloaddition reaction (target domain) [6]. This cross-validation of predictive models across different reaction types allowed for accurate prediction of photocatalytic activity with only ten training data points, showcasing its power in accelerating catalyst exploration for organic synthesis [6].

Method Transfer & Partial Validation in Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling

Research in 2022 explored model transfer between different nucleophile types in Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. This work functions as an analog to analytical method transfer. The study found that a model trained on reactions using benzamide as a nucleophile could make excellent predictions (ROC-AUC = 0.928) for reactions of phenyl sulfonamide, a mechanistically similar nucleophile [7] [8]. However, the same model performed poorly (ROC-AUC = 0.133) when applied to pinacol boronate esters, which follow a different mechanism [7] [8]. This highlights that successful "transfer" depends on fundamental chemical similarity. When the source and target domains are too different, it constitutes a major change, potentially requiring what in analytical terms would be a full or partial re-validation of the approach [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for conducting the validation experiments described in this guide, particularly in an organic chemistry context.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation Protocols |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides an accepted reference value for determining method accuracy and for use in comparative testing during method transfer [4]. |

| Homogeneous Sample Lots | Essential for method transfer via comparative testing to ensure any observed differences are due to laboratory performance, not sample variability [5]. |

| Critical Reagents (e.g., specific ligands, catalysts) | In ligand binding assays or catalytic reaction optimization, consistent reagent lots are vital for successful method transfer and cross-validation [1] [7]. |

| Standardized Solvents and Mobile Phases | Ensures reproducibility of chromatographic methods and reaction conditions during transfer and partial validation [1]. |

| Stable Quality Control (QC) Samples | Used to assess precision and accuracy in all validation types and to demonstrate system suitability during routine analysis [1] [2]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

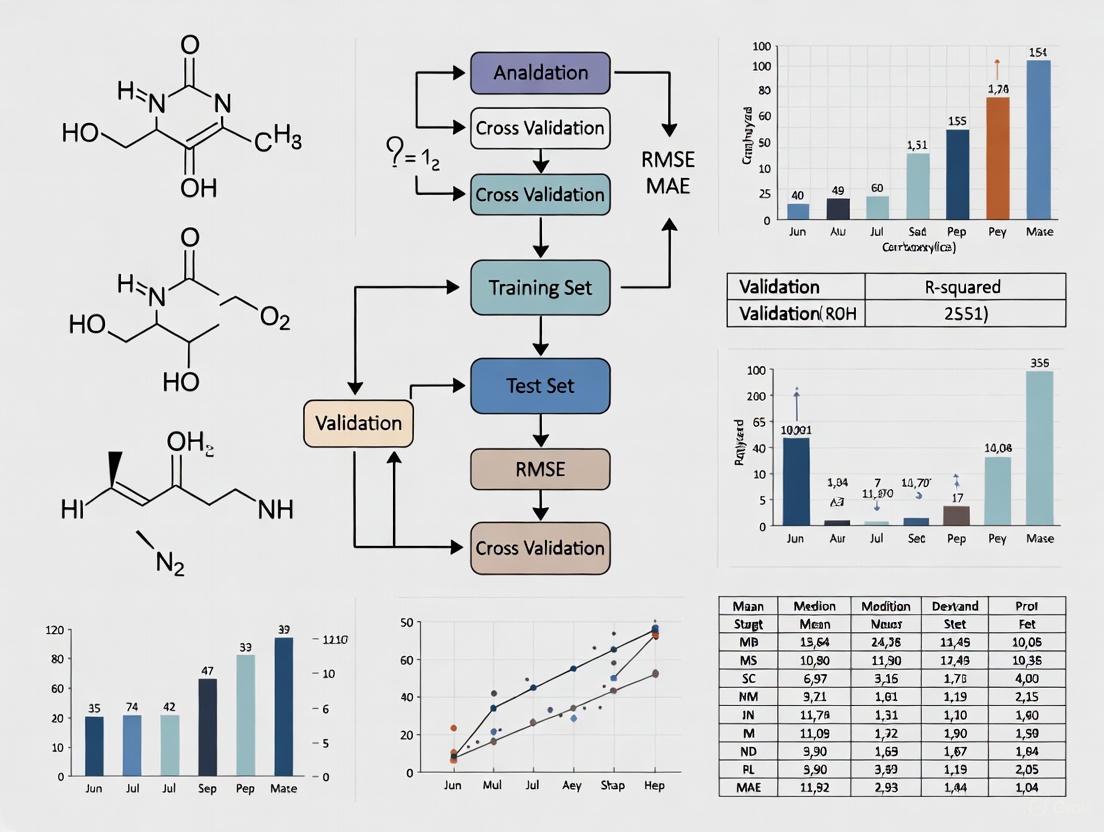

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathways and relationships between cross-validation, method transfer, and partial validation within the analytical method lifecycle.

Cross-validation, method transfer, and partial validation are distinct but complementary processes in the lifecycle of an analytical method. Cross-validation ensures equivalence, method transfer enables deployment, and partial validation manages change. For researchers in organic chemistry and drug development, selecting the correct procedure depends on a clear understanding of the specific objective: comparing different conditions, implementing a method in a new location, or adapting a method to a modified form. Applying these concepts with their appropriate protocols, as outlined in this guide, ensures scientific rigor, regulatory compliance, and the generation of reliable data critical to research and development.

The Role of Cross-Validation in the Bioanalytical Method Lifecycle

In modern drug development, the generation of reliable pharmacokinetic (PK) data is paramount, and this reliability hinges on the performance of bioanalytical methods. As a drug development program progresses, a single bioanalytical method may be deployed across multiple laboratories or may undergo significant platform changes. Cross-validation serves as the critical assessment that demonstrates equivalency between two or more validated bioanalytical methods, ensuring that data generated across different sites, studies, or platforms can be compared with confidence [9]. This process forms an essential component of the broader analytical procedure lifecycle, which encompasses initial design, development, validation, and ongoing performance verification [10].

Within the global bioanalytical community, cross-validation is formally defined as a comparison of two bioanalytical methods necessary when two or more methods are used to generate data within the same study or when data generated using different analytical techniques in different studies are included in a regulatory submission [1] [11]. This distinguishes it from method transfer (implementing an existing method in a new laboratory) and partial validation (modifying an existing method), though all three activities form part of the continuous lifecycle of method development and improvement [1]. The fundamental objective of cross-validation is to establish that different methods or the same method在不同操作环境下 produce comparable results, thereby maintaining the integrity of data throughout the drug development pipeline.

Experimental Design and Protocols for Cross-Validation

Core Experimental Strategy and Acceptance Criteria

The cross-validation strategy developed at Genentech, Inc. provides a robust framework for assessing method equivalency. This approach utilizes incurred study samples (samples from dosed subjects) rather than spiked quality controls, as they better represent the actual chemical environment of study samples [9]. The protocol involves selecting approximately 100 incurred samples that cover the applicable range of concentrations, typically based on four quartiles of in-study concentration levels [9].

Each selected sample is assayed once by both bioanalytical methods being compared. The equivalency of the two methods is then assessed using a pre-specified acceptability criterion: the two methods are considered equivalent if the percent differences in the lower and upper bound limits of the 90% confidence interval (CI) are both within ±30% [9]. This statistical approach provides a standardized benchmark for decision-making, ensuring that any observed differences between methods are not clinically or analytically significant.

For studies involving multiple laboratories, cross-validation with spiked matrix and subject samples should be conducted at each site to establish inter-laboratory reliability [11]. This is particularly crucial when sample analyses within a single study are conducted at more than one site or when different analytical techniques are used across different studies that will be included in a regulatory submission [11].

Statistical Analysis and Data Characterization

Beyond the primary equivalence testing, comprehensive statistical analysis is essential for thorough method characterization. The Genentech approach incorporates quartile by concentration analysis using the same ±30% acceptability criterion, which helps identify potential concentration-dependent biases [9]. Additionally, researchers create a Bland-Altman plot of the percent difference of sample concentrations versus the mean concentration of each sample to help further characterize the data and visualize any systematic trends or outliers [9].

The statistical rigor applied to cross-validation continues to evolve. Recent approaches have incorporated advanced frameworks like the High-Throughput Experimentation Analyzer (HiTEA), which utilizes orthogonal statistical methods including random forests, Z-score analysis of variance (ANOVA-Tukey), and principal component analysis (PCA) to draw out hidden chemical insights from comparative data [12]. These advanced statistical techniques can identify subtle relationships between method components and outcomes that might otherwise remain undetected.

Case Studies in Cross-Validation

Inter-Laboratory Cross-Validation

The application of cross-validation between different laboratories using the same bioanalytical method represents one of the most common scenarios in global drug development programs. A documented case study involving the analysis of lenvatinib, a novel multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, demonstrates this approach effectively [13]. In this study, seven bioanalytical methods by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were developed across five laboratories to support global clinical studies.

Each laboratory initially validated their method according to established bioanalytical guidelines. For the subsequent inter-laboratory cross-validation, quality control (QC) samples and clinical study samples with blinded lenvatinib concentrations were assayed to confirm comparable assay data across sites [13]. The results demonstrated that accuracy of QC samples was within ±15.3% and percentage bias for clinical study samples was within ±11.6%, confirming that lenvatinib concentrations in human plasma could be reliably compared across laboratories and clinical studies [13].

Cross-Platform Method Cross-Validation

Another critical application of cross-validation occurs when transitioning between different analytical platforms during the drug development cycle. A documented case study describes the cross-validation of a PK bioanalytical method platform change from enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to multiplexing immunoaffinity (IA) liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (IA LC-MS/MS) [9]. Such platform changes often become necessary as projects advance from early discovery to later development stages, where different performance characteristics may be required.

The experimental approach for such platform comparisons follows the same fundamental principles of using incurred samples across the analytical range and applying the ±30% confidence interval criterion for equivalence. This ensures that historical data generated using the original method remains valid and comparable to data generated using the new platform, maintaining continuity throughout the development program.

Table 1: Cross-Validation Experimental Parameters and Acceptance Criteria

| Parameter | Protocol Specification | Acceptance Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Incurred matrix samples [9] | Representative of study samples |

| Sample Size | ~100 samples [9] | Covering applicable concentration range |

| Concentration Range | Four quartiles of in-study levels [9] | Low, medium, and high concentrations |

| Statistical Analysis | 90% confidence interval of mean percent difference [9] | Limits within ±30% |

| Additional Analyses | Quartile analysis; Bland-Altman plot [9] | Same criterion; visual bias assessment |

Cross-Validation Within the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle

The bioanalytical method lifecycle encompasses three primary stages: procedure design and development, procedure performance qualification (validation), and procedure performance verification (ongoing monitoring) [10]. Cross-validation serves as a crucial bridge between these stages, particularly when methods evolve or are deployed in new contexts.

The traditional linear view of method development, validation, and transfer is giving way to a more integrated lifecycle approach that emphasizes continuous improvement and knowledge management [10]. In this model, cross-validation represents a strategic activity that maintains data comparability across method changes or multiple site implementations. This approach aligns with the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) concept, which defines the intended purpose of the analytical procedure and provides the foundation for all subsequent lifecycle activities [10].

The Global Bioanalytical Consortium (GBC) emphasizes that validation is a continuous process, with method transfer, partial validation, and cross-validation forming part of a lifecycle of continuous development and improvement of analytical methods [1]. This perspective recognizes that methods naturally evolve throughout drug development, and cross-validation provides the mechanism to ensure data integrity throughout these evolutionary changes.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Cross-Validation Studies

Successful cross-validation studies require careful selection and standardization of research reagents and materials to ensure meaningful comparisons between methods. The following table outlines key reagents and their functions in cross-validation experiments:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Cross-Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Cross-Validation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Incurred Study Samples | Biological samples from previously dosed subjects [9] | Better represents actual study samples than spiked QCs; covers metabolic profile |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Spiked samples at known concentrations [13] | Verify method performance during comparison studies |

| Reference Standards | Certified analyte materials of known purity and concentration [11] | Must be consistent between methods/labs for valid comparison |

| Internal Standards | Compounds for signal normalization [13] | Critical for mass spectrometry methods; must be consistent |

| Matrix Lots | Biological fluid from appropriate species [1] | Should be from same species and anticoagulant (if applicable) |

| Critical Reagents | Antibodies, enzymes, binding proteins [1] | For ligand binding assays; lot differences can significantly impact results |

For ligand binding assays, special attention must be paid to critical reagents, as differences in reagent lots between laboratories or methods can significantly impact results [1]. When two internal laboratories share the same critical reagents, validation requirements may be reduced; however, when different critical reagents are used, more extensive validation is typically required [1].

Cross-validation represents an indispensable component of the bioanalytical method lifecycle, providing the statistical and experimental framework to ensure data comparability when methods are used across multiple laboratories or when method platforms evolve during drug development. The standardized approach utilizing incurred samples, statistical confidence intervals, and comprehensive data characterization has proven effective in both inter-laboratory and cross-platform scenarios.

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to globalize and analytical technologies advance, the role of cross-validation will only grow in importance. By implementing rigorous cross-validation protocols, researchers and drug development professionals can maintain data integrity throughout the method lifecycle, ensuring that pharmacokinetic and toxicokinetic data generated across different sites, studies, and platforms can be reliably compared for regulatory submission and scientific decision-making.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is a pivotal organization that brings together regulatory authorities and the pharmaceutical industry to standardize the technical requirements for drug registration. Its mission is to ensure that safe, effective, and high-quality medicines are developed and registered efficiently across different regions [14]. By creating consensus-based guidelines, the ICH provides a unified framework that facilitates the mutual acceptance of clinical data by regulatory authorities in its member jurisdictions, thereby streamlining global drug development [15]. This harmonization is crucial for researchers and scientists engaged in cross-validation of analytical methods, as it establishes internationally recognized standards for data quality and integrity.

This guide objectively compares key ICH guidelines, focusing on their scope, application, and recent updates, particularly the newly finalized ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice guideline. The comparison is framed within the context of analytical method validation, providing a clear understanding of the regulatory landscape that governs pharmaceutical research and development.

Comparison of Key ICH Guidelines

The table below summarizes the core purpose, scope, and current status of major ICH guidelines relevant to drug development, providing a structured comparison for professionals.

Table 1: Comparison of Key ICH Guidelines for Drug Development

| Guideline Number | Guideline Title | Core Purpose and Scope | Key Updates / Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICH M3(R2) [16] | Non-clinical Safety Studies | Recommends international standards for non-clinical safety studies to support human clinical trials and marketing authorization for pharmaceuticals. | Active; to be read in conjunction with its Q&A document. |

| ICH E6(R3) [14] [17] [18] | Good Clinical Practice (GCP) | International ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve human subjects. | Final version issued Jan 2025; Principles & Annex 1 effective July 2025; Annex 2 expected late 2025. |

| ICH E8(R1) [17] | General Considerations for Clinical Studies | Describes internationally accepted principles and practices in the design and conduct of clinical studies to promote study quality. | Serves as a foundation for other guidelines like E6(R3). |

Detailed Analysis of ICH E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice

Key Changes and Modernized Approach

The ICH E6(R3) guideline, finalized in January 2025, marks a significant evolution from the E6(R2) version, which had become increasingly outdated [18]. This revision aims to be a "future-proof" framework, incorporating flexibility to support a broad range of modern trial designs and technological innovations [14] [18]. A key structural change is its organization into an overarching principles document, Annex 1 (for interventional clinical trials), and Annex 2 (for non-traditional interventional trials) [17]. This new structure is designed to ensure the guideline's continued relevance amid ongoing technological and methodological advancements [17].

The following diagram illustrates the structure and interconnectedness of the ICH E6(R3) guideline components.

Core Principles and Regulatory Impact

The principles of ICH E6(R3) are interdependent and must be considered in their totality to assure ethical trial conduct and the reliability of trial results [17]. The guideline promotes a risk-based and proportionate approach, encouraging "fit-for-purpose" solutions rather than a one-size-fits-all methodology [17]. It places a stronger emphasis on the perspective of study participants, considering their experience in trial design and conduct, and provides more detailed guidance on the informed consent process, including the use of technology [18].

Regulatorily, while the EMA has set an effective date of July 23, 2025, for the Principles and Annex 1, the guideline is still pending adoption by other ICH member nations [18]. The FDA has issued a draft guidance to accompany E6(R3) but includes a disclaimer that it represents the agency's "current thinking" and is not legally binding [18]. This modernized guideline is intended to support efficient, high-quality clinical trials across regions through a flexible, harmonized framework [14].

Experimental Protocols and Cross-Validation in Analytical Chemistry

Method Validation Workflow

In the context of ICH guidelines, cross-validation of analytical methods is critical for ensuring data reliability, especially when methods are transferred between laboratories or when multiple methods are used within a single study. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for cross-validation, reflecting the quality-by-design principles embedded in modern ICH guidelines like E6(R3).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting robust analytical method validation, aligning with the ICH principle of ensuring reliable and reproducible results.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Cross-Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides a substance of known purity and identity to establish method accuracy, precision, and calibration curves. Serves as the benchmark for all comparative analyses. |

| Chromatographic Columns | Essential for separation techniques like HPLC/UPLC; different columns (C18, C8, HILIC) are tested to confirm method specificity and robustness across platforms. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents are critical for minimizing background noise and ion suppression in mass spectrometric detection, ensuring method sensitivity and reproducibility. |

| Stability Test Solutions | Prepared samples placed under accelerated stress conditions (e.g., heat, light, pH) to validate the method's ability to detect and quantify degradation products. |

| System Suitability Test Kits | Pre-defined mixtures used to verify that the analytical system (instrument, reagents, and operator) is performing adequately before the validation run. |

The ICH guidelines, particularly the newly updated ICH E6(R3), provide a dynamic and harmonized framework for global drug development. The evolution towards more flexible, risk-based approaches underscores the importance of critical thinking and proportionality in both clinical trials and the supporting analytical chemistry work. For researchers and scientists, a deep understanding of these guidelines is not merely a regulatory obligation but a foundation for scientific excellence. By integrating these principles—such as quality-by-design and fit-for-purpose strategies—into the cross-validation of analytical methods, professionals can ensure the generation of reliable, high-quality data that meets rigorous international standards, thereby accelerating the development of safe and effective pharmaceuticals.

When is Cross-Validation Required? Scenarios for Inter-Laboratory and Inter-Method Comparison

Cross-validation serves as a critical bridge in scientific research, ensuring that analytical methods produce consistent, reliable, and trustworthy data. In organic chemistry and drug development, the need for cross-validation arises in two primary scenarios: when a method is transferred between laboratories and when the fundamental method platform is changed. This guide objectively compares the performance of analytical methods across these different scenarios, providing the experimental protocols and data evaluation criteria essential for confirming method equivalency.

Defining Cross-Validation in an Analytical Context

In analytical chemistry, cross-validation is the assessment of two or more bioanalytical methods to show their equivalency [9]. This process is distinct from the initial method validation and is crucial for verifying that a method produces consistent results when used by different laboratories, analysts, or equipment, or when the method itself undergoes significant modification [19]. It is a specific activity designed to manage the complex life cycle of analytical methods, which often diverge and evolve as they are applied to different species, populations, or laboratory settings [1].

Failing to cross-validate can lead to erroneous results, regulatory findings, and compromised decision-making about product safety or efficacy [19]. The core objective is to ensure inter-laboratory reproducibility and confirm method reliability across different settings, which is vital for the credibility of analytical results in pharmaceutical, food, and environmental testing [19].

Key Scenarios Requiring Cross-Validation

Scenario 1: Inter-Laboratory Comparison (Method Transfer)

Method transfer is defined as a specific activity that allows the implementation of an existing analytical method in another laboratory [1]. This is required when a pharmacokinetic (PK) bioanalytical method needs to be run in more than one laboratory to support a drug development program [9].

- Internal Transfer: This occurs between laboratories within the same organization that share common operating philosophies, infrastructure, and management systems. The degree of testing required is less extensive.

- External Transfer: This involves transferring a method to a completely external receiving laboratory. The testing requirements are more rigorous and approximate a full validation [1].

Scenario 2: Inter-Method Comparison (Method Platform Change)

As a drug development program progresses, a PK bioanalytical method format may change, and a new method platform may be validated and implemented [9]. This scenario involves cross-validating two different, but fully validated, bioanalytical methods. A common example in organic chemistry and drug development is the transition from an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to a more specific and sensitive multiplexing immunoaffinity liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (IA LC-MS/MS) method [9].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Validation

Protocol for Inter-Laboratory Comparison (Method Transfer)

The experimental approach for method transfer varies significantly based on the type of assay and the relationship between the laboratories. The following table summarizes the recommended activities as per the Global Bioanalytical Consortium [1].

Table 1: Experimental Protocol Requirements for Method Transfer

| Transfer Type | Assay Technology | Minimum Experimental Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Transfer | Chromatographic Assays | Two sets of accuracy and precision data over 2 days using freshly prepared calibration standards; LLOQ QC assessment required. |

| Internal Transfer | Ligand Binding Assays (with same critical reagents) | Four sets of inter-assay accuracy and precision runs on four different days; QCs at LLOQ and ULOQ; dilution QCs. |

| External Transfer | All Types (Chromatographic & Ligand Binding) | Full validation including accuracy, precision, bench-top stability, freeze-thaw stability, and extract stability (if appropriate). |

Protocol for Inter-Method Comparison

For comparing two different method platforms, a robust strategy developed by Genentech, Inc. utilizes incurred study samples for a direct comparison [9]. The detailed methodology is as follows:

- Sample Selection: One hundred incurred study samples are selected to cover the applicable range of concentrations, based on four quartiles (Q1-Q4) of in-study concentration levels.

- Sample Analysis: Each of the 100 samples is assayed once by each of the two bioanalytical methods being compared.

- Statistical Analysis for Equivalency:

- The percent difference in concentration for each sample between the two methods is calculated.

- The 90% confidence interval (CI) for the mean percent difference is computed.

- Acceptance Criterion: The two methods are considered equivalent if the lower and upper bound limits of the 90% CI are both within ±30% [9].

- Additional Analysis: A quartile-by-concentration analysis using the same ±30% criterion may also be performed to check for concentration-dependent biases. A Bland-Altman plot of the percent difference of sample concentrations versus the mean concentration of each sample is created to further characterize the data [9].

Comparative Experimental Data and Outcomes

The application of the above protocols generates quantitative data that allows for an objective comparison of method performance.

Table 2: Representative Cross-Validation Data for an Inter-Method Platform Change

| Sample Concentration Quartile | Mean Concentration (ng/mL) Method A (ELISA) | Mean Concentration (ng/mL) Method B (IA LC-MS/MS) | Mean % Difference | Within ±30% Criterion? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (Low) | 15.2 | 14.8 | -2.6% | Yes |

| Q2 (Medium-Low) | 155.5 | 149.3 | -4.0% | Yes |

| Q3 (Medium-High) | 855.0 | 898.0 | +5.0% | Yes |

| Q4 (High) | 1850.0 | 1750.0 | -5.4% | Yes |

| Overall | - | - | -2.8% (90% CI: -5.5% to +0.1%) | Yes |

In this representative data set, the overall 90% confidence interval for the mean percent difference falls entirely within the pre-specified ±30% acceptance range. The quartile analysis also shows no significant bias at any concentration level, leading to the conclusion that the two methods are equivalent and the platform change from ELISA to IA LC-MS/MS is justified [9].

Workflow Visualization for Cross-Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for planning and executing a cross-validation study, integrating the key scenarios and protocols described.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful cross-validation in organic chemistry and bioanalysis relies on specific, high-quality materials. The following table details key reagents and their functions in these studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Cross-Validation |

|---|---|

| Incurred Study Samples | Biological samples (e.g., plasma, serum) from dosed subjects that contain the analyte and its metabolites; considered the gold standard for assessing method comparability as they reflect the real study matrix [9]. |

| Control Matrix | The biological fluid (e.g., human plasma) free of the analyte, used to prepare calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples [1]. |

| Freshly Prepared Matrix Calibration Standards | A series of samples with known analyte concentrations, used to construct the calibration curve. Fresh preparation is recommended for validation and transfer batches to ensure accuracy [1]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known concentrations of the analyte (typically at Low, Medium, and High levels) prepared in the control matrix. They are used to monitor the accuracy and precision of the analytical method during the cross-validation study [1]. |

| Critical Reagents (for Ligand Binding Assays) | Unique components such as specific antibodies, antigens, or enzyme conjugates. Their lot-to-lot consistency is crucial, and using the same lot is often required for internal method transfers [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (for LC-MS/MS) | A chemically identical version of the analyte labeled with a heavy isotope (e.g., ²H, ¹³C). It is added to all samples to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency [1] [20]. |

Cross-validation is a scientific necessity and a regulatory expectation for ensuring data integrity in organic chemistry research and drug development. It is explicitly required during two critical junctures: the transfer of an analytical method from one laboratory to another and the change from one analytical method platform to another. By adhering to structured experimental protocols—such as the method transfer guidance for different laboratory types or the robust 100-sample strategy for method platform changes—researchers can generate conclusive quantitative data to demonstrate method equivalency. This rigorous process, supported by clear acceptance criteria and statistical tools, minimizes risk and builds confidence in the data that underpins critical decisions in scientific research and product development.

In pharmaceutical development and organic chemistry research, the reliability of analytical data is paramount. Method validation provides objective evidence that a laboratory test is fit for its intended purpose, ensuring that measurements are trustworthy and reproducible [21]. This process has evolved significantly since the 1980s, with numerous guidelines now standardizing the approach to validation across international regulatory bodies [21]. Within this framework, specific performance characteristics must be rigorously evaluated to demonstrate method competency.

The terms accuracy, precision, specificity, and ruggedness represent fundamental validation parameters that collectively define the quality and reliability of an analytical method. Understanding their precise definitions, interrelationships, and assessment methodologies is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who must ensure product safety, efficacy, and quality [22]. These parameters form the foundation of a robust analytical procedure, whether it is a targeted method for a specific analyte or the increasingly prevalent non-targeted methods (NTMs) used in fields like food authenticity and fraud detection [23].

This guide explores these critical validation parameters within the context of cross-validation studies, where methods are compared to determine their respective strengths, limitations, and suitability for specific applications in organic chemistry and pharmaceutical research.

The Role of Cross-Validation in Analytical Chemistry

Cross-validation, in the context of analytical method validation, refers to techniques for assessing how the results of a statistical analysis or analytical method will generalize to an independent data set [24]. It is primarily used to estimate how accurately a predictive model will perform in practice and to flag problems like overfitting or selection bias [24]. In a practical laboratory setting, this often involves partitioning a sample of data into complementary subsets, performing the analysis on one subset (the training set), and validating the analysis on the other subset (the validation set or testing set) [24].

For chromatographic methods and other analytical techniques, cross-validation principles are applied when comparing methods or when ensuring a method remains valid when transferred between laboratories or instruments. This process is crucial for establishing that analytical methods provide consistent, reliable data regardless of minor variations in experimental conditions or operator technique.

Defining the Core Validation Parameters

Accuracy

Accuracy is defined as the closeness of test results to the true value [22]. It measures the exactness of an analytical method and is typically expressed as the percentage of recovery of a known amount of analyte spiked into a sample matrix [21] [22]. In chromatographic method validation, accuracy is often demonstrated by spiking a placebo of the sample matrix with the external standard and showing how much has been recovered [22]. For drug substance analysis, accuracy should be established across the specified range of the analytical procedure [21].

Precision

Precision refers to the degree of agreement among individual test results when a procedure is applied repeatedly to multiple samplings of a homogeneous sample [22]. It expresses the random error of an analytical method and is usually measured as the standard deviation or coefficient of variation (relative standard deviation) of a series of measurements [22]. Precision has three distinct levels:

- Repeatability: Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time (intra-assay precision).

- Intermediate Precision (formerly referred to as Ruggedness): Precision results from within-laboratory variations due to random events such as different days, analysts, equipment, and so forth [22]. Experimental design should be employed so that the effects of these individual variables can be monitored.

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories (as in collaborative studies).

The transition in terminology from "ruggedness" to "intermediate precision" reflects the evolving standardization of validation language across the field [22].

Specificity

Specificity is the ability of a method to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [21] [22]. In chromatographic analyses, specificity ensures that peaks are free from interference and represent only the analyte of interest. The related term selectivity is often used to describe the ability of the method to discriminate the analyte of interest from other compounds in the sample mixture [21]. While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, specificity implies an absolute ability to distinguish the target analyte, whereas selectivity refers to the degree to which a method can determine particular analytes in mixtures without interference from other components.

Ruggedness (Intermediate Precision)

Ruggedness, now more commonly referred to as intermediate precision in regulatory guidelines, represents the precision of a method under normal operational variations within the same laboratory [22]. This includes changes such as different analysts, different days, different equipment, and other modified environmental or operational conditions. Establishing ruggedness demonstrates that a method produces reproducible results when repeated under various, but typical, laboratory conditions, thus indicating its reliability during routine use [22].

Comparative Analysis of Spectrophotometric and UFLC-DAD Methods

A recent study directly compared spectrophotometric and Ultra-Fast Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection (UFLC-DAD) methods for quantifying metoprolol tartrate (MET) in commercial tablets, providing exemplary experimental data for comparing these validation parameters [21].

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents: MET standard (≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich), ultrapure water, commercial tablets containing 50 mg and 100 mg of MET. All chemicals were of pro analysis grade and used without further purification [21].

Instrumentation and Conditions:

- Spectrophotometric Method: Absorbance was recorded at the maximum absorption wavelength of MET (λ = 223 nm) using an appropriate spectrophotometer.

- UFLC-DAD Method: Method optimization was performed before validation. The UFLC system was coupled with a DAD detector, offering shorter analysis time, increased peak capacity, and lower consumption of samples and solvents compared to conventional HPLC [21].

Sample Preparation: The appropriate mass of MET was measured and dissolved in proper volume of ultrapure water to prepare basic MET solution and standard solutions for constructing calibration curves. All solutions were protected from light and stored in a dark place [21]. MET was extracted from commercial tablets for analysis.

Validation Procedure: Both methods were validated for specificity/selectivity, sensitivity, linearity, dynamic range, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), accuracy, precision, and robustness following established validation guidelines [21]. Statistical comparison was performed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) at a 95% confidence level.

Quantitative Comparison of Validation Parameters

Table 1: Comparison of Validation Parameters for Spectrophotometric and UFLC-DAD Methods for MET Quantification [21]

| Validation Parameter | Spectrophotometric Method | UFLC-DAD Method | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Determined through recovery studies | Determined through recovery studies | Both methods demonstrated acceptable accuracy with recovery percentages within predefined limits |

| Precision | Good for 50 mg tablets | Excellent for both 50 mg and 100 mg tablets | UFLC-DAD showed superior precision, particularly for higher concentration formulations |

| Specificity | Limited; susceptible to interference from tablet excipients | High; effectively separated MET from other components | UFLC-DAD's chromatographic separation provided significantly better specificity |

| LOD & LOQ | Higher (less sensitive) | Lower (more sensitive) | UFLC-DAD demonstrated superior sensitivity for detecting and quantifying low analyte levels |

| Linearity Range | Narrower dynamic range | Wider dynamic range | UFLC-DAD accommodated a broader concentration range while maintaining linearity |

| Analysis Time | Faster single measurements | Shorter chromatographic run times | UFLC offered advantages in speed despite more complex instrumentation |

| Sample Volume | Required larger amounts | Lower consumption of samples and solvents | UFLC-DAD was more efficient in sample utilization |

| Application Scope | Limited to 50 mg tablets due to concentration limits | Applied to both 50 mg and 100 mg tablets | UFLC-DAD offered broader applicability across different dosage strengths |

Statistical Assessment and Environmental Impact

The study employed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) at a 95% confidence level to determine if there were significant differences between the concentrations of MET obtained by UFLC-DAD and the spectrophotometric method [21]. The results indicated that both methods provided statistically comparable results for the 50 mg tablets, suggesting that the simpler and more cost-effective spectrophotometric approach could be suitable for quality control of this dosage form.

Additionally, the greenness of both methods was evaluated using the Analytical GREEnness metric approach (AGREE) [21]. This assessment revealed that the spectrophotometric method generally had a better environmental profile than the UFLC-DAD method, highlighting an important consideration for modern laboratories striving to implement more sustainable analytical practices.

Experimental Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between the key validation parameters and the cross-validation process in analytical method development:

Validation Parameter Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation [21] [22]

| Item | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard (e.g., MET ≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich) | Serves as the primary standard for method calibration and accuracy determination; provides known purity analyte [21] [22]. | Must be of high chemical purity and well-characterized; used to prepare calibration standards and spiked samples for recovery studies. |

| Ultrapure Water (UPW) | Used as solvent for preparing standard solutions and sample extracts [21]. | Minimizes interference from impurities; essential for maintaining method specificity and baseline stability in chromatographic analyses. |

| Chromatographic Column (UFLC) | Stationary phase for compound separation in chromatographic methods [21]. | Critical for achieving specificity through resolution of analyte from potential interferents; column chemistry and dimensions impact efficiency. |

| Blank Matrix | Used to assess specificity and potential matrix effects [22]. | Should represent the sample matrix without the analyte; helps identify interference and establish baseline signals. |

| Internal Standard (where applicable) | Improves accuracy and precision by correcting for analytical variability [22]. | Ideally an isotopically labeled analog of the analyte; should mimic analyte behavior throughout sample preparation and analysis. |

| Quality Control Samples | Monitor method performance during validation and routine use [22]. | Prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations within the calibration range; used to establish precision and accuracy over time. |

The comparative analysis of spectrophotometric and UFLC-DAD methods for MET quantification demonstrates the critical importance of thoroughly evaluating accuracy, precision, specificity, and ruggedness during method validation [21]. While UFLC-DAD generally offers superior specificity, sensitivity, and a broader dynamic range, the spectrophotometric method provides a cost-effective, simpler alternative that may be fit-for-purpose for certain applications, such as quality control of specific dosage forms [21].

This comparison highlights that method selection should be based on a comprehensive understanding of all validation parameters in relation to the analytical requirements, rather than presuming one technological approach is universally superior. Furthermore, the incorporation of cross-validation techniques and statistical tools like ANOVA provides a robust framework for making informed decisions about method suitability and reliability [21] [24]. As the field advances, particularly with the emergence of non-targeted methods, these fundamental validation principles continue to provide the foundation for ensuring analytical data quality in pharmaceutical research and organic chemistry [23].

Implementing Cross-Validation: Protocols for Chromatographic and Ligand Binding Assays

Cross-validation serves as a critical methodology for establishing the reliability and transferability of analytical methods and predictive models in organic chemistry research and drug development. As the field increasingly adopts artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for predicting chemical properties and reaction outcomes, rigorous validation frameworks ensure these tools perform robustly across different laboratories and experimental conditions [25]. Cross-validation methodologies provide essential safeguards against overfitting and help researchers quantify expected performance on future unknown samples, which is particularly crucial in regulated bioanalysis and predictive chemistry applications [26] [27]. This guide examines current approaches, comparing their implementation requirements, statistical foundations, and suitability for different research contexts in organic chemistry.

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Validation Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Validation Approaches in Analytical Chemistry

| Approach | Primary Application Context | Sample Set Requirements | Acceptance Criteria | Statistical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated Bioanalysis (ICH M10 Framework) | Pharmacokinetic assays between laboratories [28] | n>30 samples spanning concentration range [28] | ±20% mean accuracy (MHLW); Debate on pass/fail criteria vs. statistical assessment [28] [27] | Deming regression, Concordance Correlation Coefficient, Bland-Altman plots [28] |

| Multivariate Classification Validation | Organic feed classification using analytical fingerprints [26] | Representative sample sets with defined scope | Expected accuracy derived from probability distributions (e.g., 96% for organic feed) [26] | Kernel density estimates, permutation tests, cross-validation/external validation probability distributions [26] |

| ML Model Cross-Validation | Photocatalyst recommendation systems [29] | >36,000 literature examples [29] | ~90% accuracy for correct photocatalyst suggestion [29] | Train-test splits, cross-validation on large datasets [29] |

Table 2: Method Selection Guide Based on Research Context

| Research Context | Recommended Approach | Key Implementation Considerations | Regulatory Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated Bioanalysis (Drug Development) | ICH M10 Framework with Statistical Assessment | Involve clinical pharmacology and biostatistics teams in design [28] | MHLW, EMA, FDA guidelines [28] [27] |

| Chemical Property Prediction | Multivariate Classification with Probability Distributions | Define explicit scope and purpose; Assess analytical repeatability in probabilistic units [26] | Research context-dependent; Peer-review standards [26] |

| Reaction Outcome Prediction | Combined Cross-Validation & External Validation | Use large, diverse datasets (>30,000 examples); Combine with external validation sets [29] [26] | Academic research standards; FAIR data principles [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Validation

Inter-Laboratory Cross-Validation for Regulated Bioanalysis

The ICH M10 guideline establishes a standardized framework for bioanalytical method cross-validation when data from multiple laboratories are combined for regulatory submission [28]. This protocol is essential for drug development professionals establishing method reliability across sites.

Sample Set Preparation:

- Prepare quality control (QC) samples at multiple concentrations spanning the analytical range

- Ensure n>30 samples to adequately characterize bias and variation [28]

- Include minimum of 16 compounds with metabolites to assess cross-reactivity [27]

Experimental Execution:

- Transfer fully validated bioanalytical methods (typically LC/MS/MS) from original to receiving laboratory

- Maintain similar methodological parameters between sites while accounting for legitimate technical differences

- Analyze cross-validation samples alongside freshly prepared QC samples at both sites [27]

Statistical Assessment:

- Apply Deming regression and Concordance Correlation Coefficient to quantify agreement

- Generate Bland-Altman plots to visualize bias between methods [28]

- Calculate 90% confidence interval (CI) of mean percent difference of concentrations

- Assess concentration bias trends by evaluating slope in concentration percent difference vs. mean concentration curve [28]

Multivariate Classification Validation for Chemical Analysis

For organic chemical analysis using multivariate classification methods (e.g., discriminating organic from conventional feed), a probabilistic validation approach is recommended [26].

Sample Set Design:

- Construct representative sample sets that explicitly define method scope and purpose

- Ensure adequateness of sample sets for intended classification task

- Include sufficient samples for cross-validation and external validation sets [26]

Methodology:

- Apply permutation tests to assess model significance

- Quantify analytical repeatability in the method's probabilistic units

- Use kernel density estimates to generalize probability distributions for meaningful interpolation [26]

Performance Assessment:

- Combine cross-validation and external validation set probability distributions

- Derive expected correct classification rate for future samples (e.g., 96% accuracy for organic feed recognition)

- Combine qualitative and quantitative aspects into a validation dossier stating performance for defined scope [26]

Machine Learning Model Validation in Organic Chemistry

For AI/ML models in organic chemistry (e.g., photocatalyst recommendation, reaction outcome prediction), cross-validation follows distinct protocols tailored to data-driven approaches [29].

Dataset Requirements:

- Utilize extensive datasets (>36,000 literature examples) for training [29]

- Implement appropriate train-test splits to avoid data leakage

- Ensure dataset diversity covers intended chemical space [30]

Validation Framework:

- Perform cross-validation under varied split strategies to assess robustness

- Evaluate using domain-specific accuracy metrics (~90% for photocatalyst recommendation) [29]

- Conduct experimental validation on out-of-box reactions to test real-world performance [29]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Cross-Validation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Cross-Validation | Application Context | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Benchmark analytical performance across methods/labs [27] | Regulated bioanalysis | Spiked QC samples at multiple concentrations [28] |

| Reference Standards | Establish calibration and quantify bias between methods [27] | All quantitative analysis | Certified reference materials with known purity [27] |

| Chemical Descriptors | Enable ML model training and prediction [31] | AI/ML in chemistry | Topological indices (Estrada, Wiener, Gutman) [31] |

| Diverse Solvent Systems | Assess method robustness across reaction conditions [25] | Organic synthesis optimization | Wide range of solvents with different polarities [25] |

| Cross-Validation Samples | Directly compare method performance [27] | Inter-laboratory studies | Identical samples analyzed at multiple sites [27] |

Statistical Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Emerging Standards for Acceptance Criteria:

The field is currently transitioning from rigid pass/fail criteria toward nuanced statistical assessments, particularly in regulated bioanalysis [28]. Two competing approaches demonstrate this evolution:

Prescriptive Approach: Nijem et al. propose standardized acceptance criteria where the 90% CI of mean percent difference falls within ±30%, followed by assessment of concentration-dependent bias trends [28]

Contextual Approach: Fjording et al. argue that pass/fail criterion is inappropriate, emphasizing that clinical pharmacology and biostatistics teams should define context-specific criteria based on intended data use [28]

Statistical Analysis Methods:

Key Considerations for Statistical Interpretation:

- Inter-laboratory variability may introduce bias not attributable to analytical methods themselves, often manifesting as random (not concentration-dependent) deviation [27]

- Probability distributions provide more insightful performance assessment than binary classification results for multivariate classification [26]

- Combined cross-validation and external validation distributions offer the best estimate for future method performance [26]

Cross-validation methodologies continue to evolve across organic chemistry research domains, with distinct approaches required for regulated bioanalysis, multivariate chemical classification, and machine learning applications. While acceptance criteria remain context-dependent, the field shows a clear trend toward sophisticated statistical assessment over simplistic pass/fail criteria. Researchers must carefully select cross-validation designs that align with their specific research context, regulatory requirements, and intended use of resulting data. As AI/ML technologies further transform organic chemistry, robust cross-validation frameworks will become increasingly crucial for validating predictive models and ensuring their reliable application to critical challenges in medicine, materials, and energy research.

In the field of organic chemistry research and drug development, the reliability of analytical data is paramount. Chromatographic assays, particularly Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), serve as cornerstone techniques for the identification and quantification of chemical entities [32]. The credibility and regulatory acceptance of results generated by these techniques hinge on rigorous method validation, a process that demonstrates the method's suitability for its intended purpose [33] [34]. This guide focuses on the core validation parameters of precision, accuracy, and linearity, providing a comparative analysis of assessment protocols for LC-MS and GC-MS platforms.

The importance of validation is underscored by stringent global regulatory requirements. As noted in a 2025 webinar on HPLC method validation, to meet US EPA or FDA requirements, a method must meet many stringent requirements. The more important of these specific analytical methods are method validation and instrument validation. To not do so is a non-compliance in which any data is not usable or reportable [33]. Within the framework of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, precision, accuracy, and linearity form the foundational trilogy that assures the quality and reliability of analytical data in pharmaceutical analysis and beyond [34] [35].

Core Principles: Precision, Accuracy, and Linearity

Defining the Key Validation Parameters

Precision describes the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions. It is typically expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) and investigated at three levels: repeatability (intra-assay), intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst, inter-instrument), and reproducibility [36] [34]. High precision indicates low random error in the measurements.

Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between the value which is accepted either as a conventional true value or an accepted reference value and the value found [34]. It is often reported as percentage recovery of a known, spiked amount of analyte in the sample matrix (e.g., placebo or biological fluid) and reflects the trueness of the method, quantifying systematic error [36].

Linearity of an analytical method is its ability (within a given range) to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample [36] [34]. It is demonstrated by plotting a calibration curve and assessing its fit using the correlation coefficient (r) or coefficient of determination (r²).

The Interrelationship of Validation Parameters

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequential relationship between these core validation parameters and their role in establishing a reliable analytical method.

Comparative Data Tables for Validation Parameters

Acceptance Criteria for GC-MS and LC-MS Assays

Table 1: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Precision, Accuracy, and Linearity in Chromatographic Assays

| Parameter | Sub-category | GC-MS Acceptance Criteria | LC-MS Acceptance Criteria | Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Repeatability | RSD < 2% [36] | RSD < 2-3% [34] [37] | ICH [35] |

| Intermediate Precision | RSD < 3% [36] | RSD < 3-5% [34] | ICH [34] | |

| Accuracy | Recovery (%) | 98-102% [36] | 98-102% (Pharmaceutical); 90-110% (Biological) [35] | ICH [34] |

| Linearity | Correlation (r) | ≥ 0.999 [36] | ≥ 0.999 [35] [37] | ICH [34] |

| Coefficient (r²) | ≥ 0.998 [35] | ≥ 0.998 [35] | ICH [35] |

Experimental Design for Parameter Assessment

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Assessing Precision, Accuracy, and Linearity

| Parameter | Experimental Design | GC-MS Example | LC-MS Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Repeatability: 6 replicates at 100% test concentration.Intermediate Precision: Different day/analyst/instrument. | Analysis of paracetamol/metoclopramide; RSD < 3.6% [35] | Untargeted metabolomics using Q Exactive HF Orbitrap; RSD evaluation across runs [37] |

| Accuracy | Spike and recover known analyte amounts into sample matrix (placebo, plasma). Calculate % recovery. | Recovery of paracetamol from tablets: 102.87%; from plasma: 92.79% [35] | Recovery studies for progesterone in gel formulation [34] |

| Linearity | Analyze minimum of 5 concentrations (e.g., 50-150% of target). Plot response vs. concentration. | Paracetamol: 0.2-80 µg/mL, r²=0.9999 [35] | Progesterone: demonstrated via "amount injected vs. peak area" plot [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a GC-MS Assay Validation

The following protocol is adapted from a recent green GC-MS method for the simultaneous analysis of paracetamol and metoclopramide in pharmaceuticals and plasma [35].

Instrumental Conditions:

- GC System: Agilent 7890 A GC.

- Column: 5% Phenyl Methyl Silox (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm).

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow rate of 2 mL/min.

- MS Detector: Agilent 5975 C inert mass spectrometer with Triple Axis Detector.

- Ionization Mode: Electron Impact (EI).

- Data Acquisition: Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) at m/z 109 for paracetamol and m/z 86 for metoclopramide.

Procedures for Key Parameters:

- Linearity: Prepare serial dilutions of a standard stock solution in ethanol to obtain concentrations ranging from 0.2–80 µg/mL for paracetamol and 0.3–90 µg/mL for metoclopramide. Inject each concentration in triplicate. Plot the mean peak area versus the analyte concentration and perform linear regression analysis [35].

- Accuracy (Recovery): For pharmaceutical analysis, grind and homogenize tablets. For plasma analysis, use medication-free human plasma. Spike the matrix with known quantities of the analytes at low, medium, and high concentrations within the linear range. Process and analyze these samples. Calculate the percentage recovery by comparing the measured concentration to the spiked concentration [35].

- Precision: Assay three concentration levels (low, medium, high) of the analytes with six replicates each within the same day (intra-day precision) and on three different days (inter-day precision). Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD%) for the measured concentrations at each level [35].

Protocol for an LC-MS/MS Assay Validation

This protocol draws from validated methods used in pharmaceutical analysis and untargeted metabolomics [37] [34].

Instrumental Conditions:

- LC System: UHPLC system (e.g., Vanquish Neo, i-Series, or Infinity III).

- Column: Appropriate C18 or specialized column (e.g., bio-inert for proteins).

- Mobile Phase: Binary or ternary gradient, commonly acetonitrile/water or methanol/water, often with a modifier like formic acid.

- MS Detector: Triple quadrupole (QQQ) for targeted analysis (e.g., Sciex 7500+, Shimadzu LCMS-TQ) or high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap) for untargeted work.

- Ionization: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), positive or negative mode.

Procedures for Key Parameters:

- Linearity and Range: Prepare a calibration curve with a minimum of five standard solutions covering the expected range, from the lower limit of quantitation (LOQ) to 120-150% of the working concentration. Analyze each level in duplicate or triplicate. Evaluate the linearity by the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line [36] [34].

- Precision (Repeatability and Intermediate Precision): Perform a minimum of six injections of a homogeneous sample at 100% test concentration. For intermediate precision, have a different analyst repeat the analysis on another instrument on a separate day. Report the RSD for the results [36] [34].

- Accuracy: For drug substance analysis, use a placebo mixture spiked with known amounts of the analyte. For complex matrices like in metabolomics, use a stable isotope-labeled internal standard if available. The stable isotope–assisted approach enables the detection of only truly plant-derived compounds and can be helpful in identifying and correcting matrix effects [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Chromatographic Assay Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | High-purity reference compounds for calibration and quantification. | Critical for establishing accuracy and linearity; purity should be certified [34] [35]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | e.g., ¹³C-labeled analogs of analytes. | Used in stable isotope–assisted methods to correct for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation, improving accuracy and precision [37]. |

| HPLC/Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, water) for mobile phase and sample preparation. | Minimizes background noise and system contamination, crucial for robust performance [34] [35]. |

| Chromatography Columns | The physical medium where separation occurs (e.g., C18, phenyl, chiral stationary phases). | Column selection (chemistry, dimensions, particle size) is a primary factor in achieving separation [38] [39]. |

| Sample Preparation Materials | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, filters, vials. | Essential for cleaning up complex samples (e.g., plasma, tissue) to reduce matrix effects and protect the instrument [35]. |

Technological Advancements and Future Directions

The field of chromatographic method development and validation is being transformed by data science and automation. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are now being deployed to manage the complexity of method development, particularly for techniques like 2D-LC where optimizing a method can span several months [39]. A notable innovation is the "Smart HPLC Robot," a hybrid system that uses a digital twin and AI to autonomously optimize HPLC methods after a short calibration phase, drastically reducing manual work, material use, and experimental time [39].

Furthermore, data-driven approaches like surrogate optimization are streamlining processes in complex setups such as online supercritical fluid extraction–supercritical fluid chromatography (SFE–SFC). These techniques help streamline the optimization process by requiring fewer experimental steps, while accommodating more variables than conventional design strategies [39]. In mass spectrometry, recent introductions like the Sciex 7500+ MS/MS and ZenoTOF 7600+ systems offer enhanced resilience, faster scanning speeds, and improved user serviceability, pushing the boundaries of sensitivity and throughput in quantitative and qualitative analyses [38].

The rigorous assessment of precision, accuracy, and linearity is non-negotiable for generating reliable and regulatory-compliant data from LC-MS and GC-MS assays. While the fundamental principles and acceptance criteria are well-defined and largely consistent across techniques, the specific experimental protocols must be tailored to the analytical platform (GC-MS vs. LC-MS) and the sample matrix (pure API, formulation, or complex biological fluid). The ongoing integration of AI and machine learning promises to accelerate the method development and validation lifecycle, enhancing both efficiency and robustness. For researchers in drug development and organic chemistry, a deep understanding of these protocols is essential for ensuring the quality and integrity of their analytical results.

Ligand binding assays (LBAs) are indispensable tools in biotherapeutics development, enabling the quantification of drugs, biomarkers, and immunogenic responses. Their effectiveness, however, is heavily influenced by three interconnected pillars: the quality of critical reagents, the validation of dilutional linearity via parallelism, and the management of matrix effects. This guide objectively compares leading LBA platforms and methodologies, providing a framework for their cross-validation within analytical chemistry and drug development workflows.

Critical Reagents: The Foundation of Assay Performance

Critical reagents, such as antibodies, target proteins, and labeled detection molecules, are the core components that define the specificity, sensitivity, and robustness of any LBA. Their consistent performance is paramount for generating reliable data across the drug development lifecycle.

Comparative Platform Performance and Reagent Dependency

The choice of detection platform can accentuate or mitigate challenges related to reagent quality. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of common LBA platforms, which are intrinsically linked to the reagents used.

Table 1: Comparison of Common LBA Detection Platforms and Their Reliance on Reagents

| Detection Platform | Signal Output | Key Reagent Considerations | Typical Sensitivity | Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric (e.g., ELISA) [40] | Optical Density | Enzyme-antibody conjugates (e.g., HRP), TMB substrate. Susceptible to matrix interference. | Moderate | 2-3 logs |

| Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) [41] [40] | Relative Light Units | Ruthenium chelate labels; requires specific buffers and cleaning agents. High sensitivity reduces reagent consumption. | High | >3 logs |

| Time-Resolved Fluorescence (TRF) [40] | Relative Light Units | Lanthanide chelates (e.g., Europium); long emission half-life reduces background. | High | >3 logs |

| Luminescence [40] | Relative Light Units | Luminol or other chemiluminescent substrates. | Moderate to High | 3 logs |

| Bioluminescence (e.g., SDR Assay) [42] | Relative Light Units | NanoLuc luciferase or HiBiT/LgBiT fusion proteins; function-independent, gain-of-signal readout. | Very High | Varies by target |

No single platform consistently outperforms all others across every assay protocol [41]. The optimal choice depends on the required sensitivity, the affinity of the critical reagents, and the assay format. For instance, while ECL platforms often provide high sensitivity, this is contingent upon the quality of the ruthenium-labeled reagents [40].

Advanced Reagent Technologies

Innovations in reagent technology are continuously pushing the boundaries of LBA capabilities:

- Recombinant Antibodies: Engineered for greater consistency, specificity, and affinity, leading to more accurate and reliable assays [43].

- Single-Molecule Assays: Technologies like digital ELISA and Simoa (Single Molecule Array) use recombinant antibodies and signal amplification to achieve ultra-low detection limits, revolutionizing biomarker detection [43].