Flow Chemistry vs Batch Organic Synthesis: A Modern Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of flow chemistry and batch synthesis for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Flow Chemistry vs Batch Organic Synthesis: A Modern Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of flow chemistry and batch synthesis for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational principles, practical applications across pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals, and addresses key challenges like solids handling and process optimization. Leveraging the latest trends, including the integration of automation and machine learning, it offers a validated framework for process selection to enhance efficiency, safety, and scalability in organic synthesis.

Understanding the Core Principles: Batch and Flow Chemistry Defined

What is Batch Chemistry? The Traditional Workhorse of Organic Synthesis

Batch chemistry is the traditional and foundational method of chemical synthesis, where all reactants are combined and reacted within a single vessel for a predetermined period under controlled conditions [1]. This approach is characterized by a distinct start and end point for each reaction cycle; after the reaction is complete, the product is isolated, and the vessel is cleaned before the next batch begins [1] [2]. For decades, batch chemistry has been the default methodology across pharmaceutical R&D, specialty chemical development, and academic research, serving as the workhorse that enables flexible and customizable synthesis of complex molecules [1].

Its central role in organic synthesis is anchored in its simplicity and adaptability, allowing chemists to perform everything from early-stage exploratory reactions to multi-step synthesis of sophisticated target compounds. Despite the emergence of alternative technologies like continuous flow chemistry, batch processing remains deeply entrenched in laboratory and industrial practice due to its well-established protocols, extensive historical data, and regulatory familiarity [1] [3].

Core Principles and Methodology

The Batch Process Workflow

The batch reaction process follows a systematic, sequential workflow. The following diagram outlines the key stages from initial setup to final product isolation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Equipment and Reagents

A standard batch chemistry setup requires specific equipment and reagents to execute reactions effectively. The table below details these essential components and their functions.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Batch Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Vessels | Round-bottom flasks, jacketed reactor systems (e.g., ReactoMate) [4] | Contain the reaction mixture; jacketed systems allow for precise temperature control. |

| Heating/Mixing | Hotplates, overhead stirrers, magnetic stirrers, recirculating heaters [4] | Provide energy for reactions and ensure homogeneous mixing of reactants. |

| Temperature Control | Heating mantles, recirculating chillers, DrySyn blocks [4] | Maintain consistent reaction temperature for optimal yield and selectivity. |

| Reagent Addition | Addition funnels, syringe pumps | Enable controlled, dropwise addition of reagents during the reaction. |

| Atypical Reactors | Photoreactors (e.g., Lighthouse) [4], parallel synthesis platforms (e.g., DrySyn multi) [4] | Facilitate specialized reactions like photochemistry or high-throughput experimentation. |

Experimental Protocols

General Procedure for a Standard Batch Reaction

Title: General Procedure for a Standard Batch Organic Synthesis Reaction

Principle: This protocol outlines the fundamental steps for executing a typical organic synthesis reaction in a batch reactor, ensuring reproducibility and control over reaction parameters.

Materials and Equipment:

- Round-bottom flask (appropriately sized for reaction volume)

- Magnetic stir bar or overhead stirrer

- Heating mantle or oil bath with temperature control

- Reflux condenser (if heating above ambient temperature)

- Addition funnel or syringe pump

- Inert atmosphere source (e.g., N₂ or Ar gas) if required

- Relevant solvents, reactants, catalysts, and reagents

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Assemble the round-bottom flask containing a stir bar. Attach the flask to the reflux condenser and ensure all joints are secure. If needed, equip the system with an inert gas inlet.

- Charging Reactants: Charge the flask with the solvent and primary reactants. If using an inert atmosphere, purge the system with inert gas for 5-10 minutes.

- Initiating Reaction: Begin stirring and bring the reaction mixture to the target temperature using the heating mantle/oil bath.

- Reagent Addition: For reagents that require controlled addition, use the addition funnel or syringe pump to add them dropwise to the reaction mixture over the specified period.

- Reaction Monitoring: Maintain the target temperature and stirring for the duration of the reaction. Monitor reaction progress using Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) or in-situ Process Analytical Technology (PAT) probes at regular intervals.

- Quenching: Once the reaction is complete (as determined by monitoring), cool the reaction mixture to room temperature. Quench the reaction by adding a quenching agent (e.g., water for acid/base reactions) or by simply stopping agitation and heating.

- Work-up: Transfer the mixture to a separatory funnel for liquid-liquid extraction if necessary. Isolate the organic layer.

- Purification: Purify the crude product using standard techniques such as distillation, recrystallization, or column chromatography.

- Cleaning: Clean the reactor and all glassware thoroughly before the next use.

Protocol for High-Throughput Batch Screening

Title: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in Batch Mode

Principle: This protocol leverages parallel batch reactors in microtiter plates (MTPs) to rapidly screen a large number of reaction variables (e.g., catalysts, ligands, solvents) simultaneously, accelerating reaction optimization and discovery [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Microtiter plates (MTPs), typically 96-well format

- Automated liquid handling system

- Parallel synthesis reactor block (e.g., DrySyn multi) [4]

- Multi-position magnetic stirrer hotplate

- Sealing mats or caps for MTPs (especially for air-sensitive reactions)

- Automated analysis system (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Design the experiment using strategic methods (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to efficiently explore the multi-dimensional chemical space of variables [5] [6].

- Plate Preparation: Use the automated liquid handler to dispense precise volumes of solvents, substrates, and reagents into individual wells of the MTP according to the experimental design.

- Reaction Execution: Seal the plate and place it on the pre-heated parallel synthesis reactor block. Initiate stirring and maintain the target temperature for the specified reaction time.

- Quenching and Dilution: After the reaction time, use the automated system to add a quenching solvent to each well to stop the reaction and dilute the samples for analysis.

- Analysis and Data Processing: Transfer aliquots from each well to the automated analysis system (e.g., HPLC) to determine conversion and yield. Compile the results into a dataset for analysis, often aided by machine learning algorithms to identify optimal conditions [5].

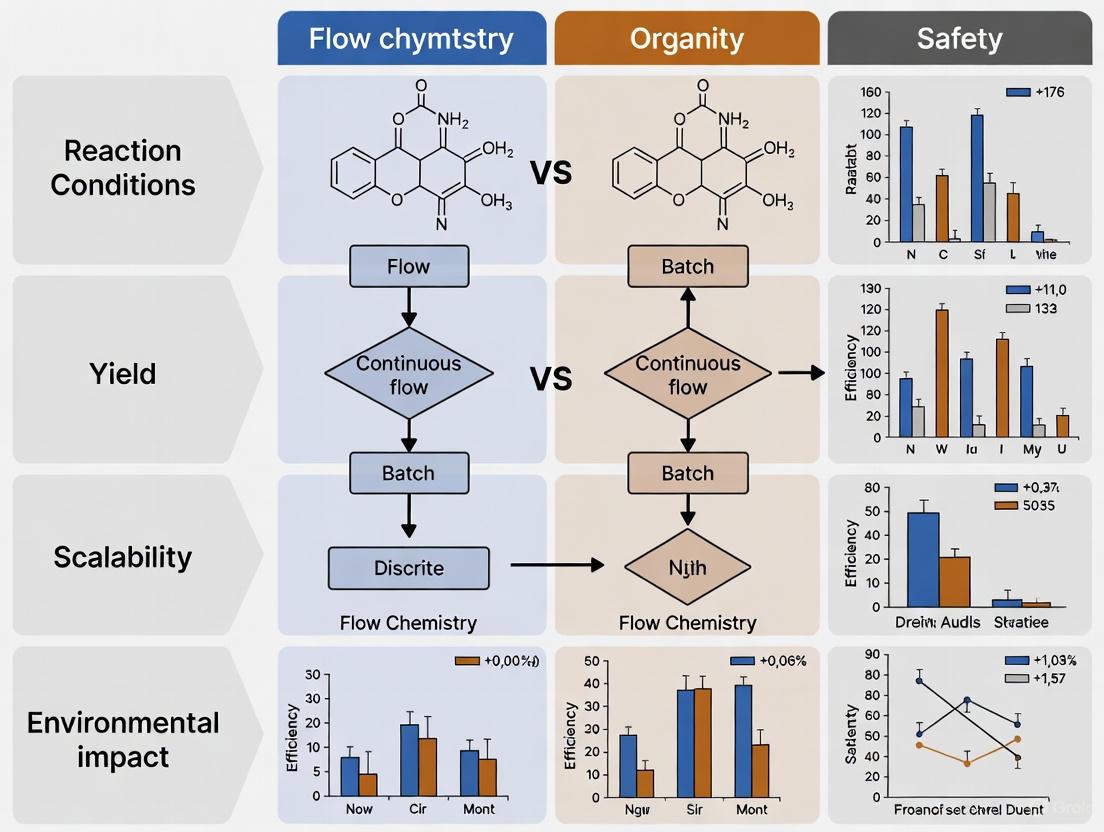

Comparative Analysis: Batch vs. Flow Chemistry

The selection between batch and continuous flow chemistry is a critical decision in process development. The following table provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison based on key performance metrics.

| Factor | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible mid-reaction adjustments possible [1]. | Superior, precise control of residence time, temperature, and mixing [1] [3]. |

| Scalability | Challenging; scale-up requires re-engineering and often re-optimization [1]. | Seamless; scaling often involves longer run times or numbering up reactors [1] [7]. |

| Safety | Higher risk for exothermic or hazardous reactions due to large volumes [1] [7]. | Inherently safer; small reactor volume minimizes risk [1] [3]. |

| Initial Cost | Lower; utilizes standard lab glassware and equipment [1]. | Higher; requires specialized pumps, reactors, and sensors [1]. |

| Productivity | Limited by downtime for cleaning and resetting between batches [1] [2]. | Continuous, high-throughput operation with minimal downtime [1]. |

| Handling Solids | Excellent; well-suited for reactions involving solids or slurries [4]. | Problematic; high risk of clogging microreactors [3]. |

| Reaction Time | Suitable for long reactions (hours/days). | Ideal for fast reactions, but residence times can be extended. |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

Batch chemistry maintains a dominant position in specific stages of pharmaceutical research and development, where its strengths are most valuable.

- Exploratory Synthesis and Medicinal Chemistry: In early drug discovery, the flexibility to rapidly test new molecular entities and make on-the-fly adjustments to reaction conditions is paramount. Batch chemistry is ideal for this purpose, allowing medicinal chemists to synthesize diverse compound libraries and optimize lead structures in a highly adaptable manner [1].

- Multi-Step Synthesis of Complex Molecules: The synthesis of complex Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) often involves multiple sequential steps, some of which may require long reaction times or involve solid intermediates. The ability to perform each step in a dedicated batch reactor, with isolation and purification of intermediates, provides a logical and straightforward synthesis route [1].

- High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Optimization: As detailed in Protocol 3.2, batch-based HTE is a powerful tool for simultaneously screening a vast array of catalysts, ligands, and solvents to find optimal conditions for a specific reaction, generating rich data sets for machine learning and process understanding [5].

Batch chemistry remains an indispensable tool in the synthetic chemist's arsenal. Its simplicity, flexibility, and well-understood principles solidify its status as the traditional workhorse of organic synthesis, particularly in research environments that prioritize adaptability and exploratory work. The methodology is perfectly suited for multi-step synthesis, early-stage drug discovery, and situations involving heterogeneous mixtures or solids.

While continuous flow chemistry offers compelling advantages in safety, control, and scalability for optimized, production-oriented processes, it does not render batch processing obsolete. Instead, the two approaches are increasingly viewed as complementary technologies. A modern, efficient research and development workflow often employs batch chemistry for initial discovery and reaction scoping, followed by a transfer to continuous flow for process intensification and larger-scale manufacturing of critical intermediates and final APIs [1] [3]. Understanding the strengths and limitations of batch processing is, therefore, fundamental to making informed decisions on process selection in organic synthesis.

Flow chemistry, also known as continuous flow chemistry, is a modern chemical synthesis approach where reactants are continuously pumped through a reactor system, allowing reactions to occur as the materials flow along a defined path [1] [8]. This methodology represents a fundamental shift from traditional batch processing, where reactions occur in a single contained vessel. In flow chemistry, chemical transformations take place within the confines of typically narrow tubing or specialized microreactors, with reactants and products moving steadily through the system [9]. This continuous processing technique provides enhanced control over reaction parameters including residence time, temperature, pressure, and mixing efficiency, enabling chemists to access novel chemical spaces and improve process safety and sustainability [8] [10].

The growing adoption of flow chemistry across pharmaceutical development, fine chemical synthesis, and academic research stems from its unique ability to address limitations inherent in traditional batch processes [1]. By providing precise manipulation of reaction conditions and enabling seamless scalability, flow chemistry has emerged as a powerful tool for modern chemical research and development, particularly suited for hazardous reactions, photochemistry, and processes requiring extreme temperatures or pressures [8].

Fundamental Principles and Comparison with Batch Processing

Core Principles of Flow Chemistry

Flow chemistry operates on several fundamental principles that differentiate it from batch processing. The continuous movement of reaction mixtures through confined channels allows for precise control over reaction time, known as residence time, by adjusting flow rates and reactor volume [8]. The high surface area-to-volume ratio in flow reactors enables efficient heat transfer, critical for managing exothermic or cryogenic reactions [11] [10]. Additionally, the small internal dimensions promote rapid mixing via diffusion, while system pressurization permits operation at temperatures significantly above the normal boiling point of solvents, dramatically accelerating reaction rates [11] [8].

Flow Chemistry vs. Batch Chemistry: A Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the key differences between flow chemistry and traditional batch chemistry approaches:

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison between batch and continuous flow chemistry

| Factor | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible mid-reaction adjustments [1] | Precise, automated control of parameters [1] |

| Scalability | Challenging; often requires re-optimization [1] | Seamless scale-up via numbering-up or increased runtime [1] [8] |

| Safety | Higher risk for hazardous reactions due to large volumes [1] | Enhanced safety; small reactor volumes minimize risk [1] [8] |

| Heat/Mass Transfer | Limited by vessel size and stirring efficiency [1] | Excellent due to high surface-to-volume ratio [11] [10] |

| Reaction Time | Determined by kinetics and operator | Precisely controlled via flow rate and reactor volume [8] |

| Equipment Cost | Lower initial investment; standard lab glassware [1] | Higher initial investment; specialized pumps and reactors [1] |

| Productivity | Limited by batch downtime and cleaning [1] | Continuous, high-throughput operation [1] |

| Process Windows | Limited by solvent boiling point and safety | Enables extreme conditions (high T/P) [11] [8] |

Key Equipment and Reactor Configurations

A typical flow chemistry system consists of several core components: pumps for fluid delivery, tubing or manifolds for fluid guidance, a reactor unit where the chemical transformation occurs, and often a back-pressure regulator to maintain system pressure [8]. Additional elements may include in-line purification devices, analytical instruments for real-time monitoring (Process Analytical Technology or PAT), and product collection units [12].

Types of Flow Reactors

The choice of reactor is critical and depends on the specific chemical transformation being performed. The most common reactor types are detailed in the table below:

Table 2: Overview of common flow reactor types and their applications

| Reactor Type | Key Characteristics | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Microreactors (Chip Reactors) | Micrometer-range channels; high surface-area-to-volume ratio [8] | Highly exothermic reactions; hazardous transformations (e.g., diazo, azide chemistry) [8] |

| Tubular/Coil Reactors | Made of PFA, PTFE, or stainless steel; versatile and durable [8] | Photochemistry; general synthesis; provides near-plug flow behavior [8] |

| Packed-Bed Reactors | Filled with solid catalyst or immobilized enzyme particles [8] | Heterogeneous catalysis (e.g., hydrogenation); biotransformations [8] |

| Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors (CSTRs) | Hybrid approach; agitator for mixing [8] | Reactions involving slurries and viscous multiphase systems [8] |

Experimental Protocols in Flow Chemistry

General Protocol for Setting Up a Flow Reaction

This protocol provides a foundational workflow for configuring and executing a standard flow chemistry reaction.

Principle: To safely and efficiently perform a chemical transformation in a continuous flow system by precisely controlling reaction parameters including residence time, temperature, and stoichiometry [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Flow Chemistry Components

Table 3: Key equipment and reagents for flow chemistry experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Syringe or HPLC Pumps | Precisely deliver reagents at defined flow rates. | Ensure chemical compatibility and required pressure range. |

| Tubing (PFA, PTFE, Stainless Steel) | Conduits for reagent flow and reactor core. | Select material based on chemical compatibility, temperature, and pressure. |

| T-Mixers or Y-Mixers | Combine multiple reagent streams efficiently. | Enable rapid mixing at point of confluence. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Maintains system pressure above ambient. | Prevents solvent boiling/degassing; essential for high-T reactions. |

| Temperature-Controlled Bath/Block | Heats or cools the reactor. | Ovens, cryostats, or heating blocks provide precise thermal control. |

| In-line Analytics (e.g., IR, UV) | Monitors reaction progress in real-time (PAT). | Enables immediate feedback and automated optimization [12]. |

| Reaction Solvents & Reagents | High-purity chemicals dissolved at known concentrations. | Solutions must be homogeneous and particulate-free to prevent clogging. |

Procedure:

- System Assembly: Connect the reagent reservoirs to the pumps using appropriate tubing. Link the pump outlets to a mixing tee or Y-mixer. Attach the mixer outlet to the reactor (e.g., a coiled tube). Connect the reactor outlet to the back-pressure regulator, followed by the product collection vessel [8].

- System Priming and Pressurization: Fill the reagent syringes or pumps with your solutions, ensuring no air bubbles are present. Prime the system by flowing solvent through all components at a moderate flow rate. Set the desired pressure on the back-pressure regulator and allow the system to stabilize.

- Parameter Setting and Equilibration: Set the reactor temperature using the heating/cooling unit. Calculate the combined total flow rate required to achieve the target residence time based on the reactor's internal volume. Initiate the flow of reagents at the calculated rates and allow the system to reach steady state, as indicated by stable pressure and a consistent product stream.

- Reaction Execution and Collection: Collect the pre-run output until steady state is confirmed. Begin collecting the product fraction in a clean, labeled vessel. Monitor system pressure and temperature throughout the run.

- System Shutdown and Cleaning: Once complete, switch the reagent feed to a clean solvent to flush the entire system. Continue flushing until the effluent is clear and no residual product is detected by in-line analytics or TLC.

Notes: Always conduct a risk assessment before performing new reactions. For reactions generating solids, consider using sonication or CSTRs to mitigate clogging [8]. The system's dead volume should be accounted for when determining collection times.

Protocol for a Telescoped Multi-Step Synthesis in Flow

Principle: To integrate multiple synthetic steps into a single, continuous process without isolating intermediates, thereby increasing efficiency, reducing waste, and improving handling of unstable species [8].

Procedure:

- Reactor Configuration: Design a flow system where the output of the first reactor is directly fed into one or more subsequent reactors. This may involve adding in-line quenching, extraction, or reagent addition modules between reaction steps.

- Individual Step Optimization: First, optimize each synthetic step independently in flow to determine the ideal residence time, temperature, and concentration for each stage.

- System Integration: Connect the optimized modules in series. Introduce the starting materials into the first reactor. The resulting intermediate stream is then directed through the necessary workup modules (if any) and into the second reaction stage.

- Balancing and Synchronization: Adjust the flow rates of all input streams to ensure stoichiometric balance across the entire telescoped system. The residence times of each stage must be synchronized so that the intermediate from the first step enters the second step at the correct rate.

- Monitoring and Collection: Use in-line PAT tools (e.g., IR, UV) at critical points to monitor the formation of intermediates and the final product. Collect the combined output once the entire system has reached a steady state.

Notes: Telescoping is highly effective for reactions with hazardous intermediates (e.g., diazonium salts, organolithiums), as it minimizes their accumulation [8]. An example from the literature shows a telescoped borohydride reduction and oxidation achieving an 82% overall yield in flow, compared to 45% in batch [8].

Applications and Case Studies in Drug Development

Flow chemistry has demonstrated significant impact in pharmaceutical research and development, enabling safer, more efficient, and scalable synthetic processes.

Handling Hazardous and Energetic Reactions

Flow chemistry excels in managing reactions deemed too dangerous for conventional batch scale-up. A prominent example is the safe handling of diazotization reactions. In batch, diazonium intermediates can accumulate and decompose explosively. In flow, these intermediates are generated on-demand and immediately consumed in the next step, minimizing accumulation. One reported diazotization reaction yielded 90% and produced 1 kg of product in 8 hours using flow, compared to a 56% yield in batch [8]. Similarly, flow systems safely manage the use of highly reactive organolithium reagents by employing rapid mixing and short residence times, allowing some reactions to proceed at higher temperatures (-20°C in flow vs. -78°C in batch) while improving yields (60% in flow vs. 32% in batch) [8].

Industrial Implementation: Apremilast Continuous Manufacturing

A landmark case study is the development of a continuous flow process for manufacturing Apremilast, an API for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Dr. Hsiao-Wu Hsieh and his team at Amgen were awarded the 2025 OPR&D Outstanding Publication of the Year Award for this work [13]. The project successfully addressed sustainability and supply chain issues by implementing flow and green chemistry principles. The continuous manufacturing process established a new workflow that laid the foundation for future lab automation applications and cross-disciplinary collaboration, demonstrating flow chemistry's viability for commercial API production [13].

Photochemical and High-Temperature Transformations

Flow reactors are uniquely suited for photochemistry because their narrow channels ensure uniform light penetration, unlike batch reactors where light intensity diminishes rapidly from the surface. This allows for efficient scaling of photochemical reactions, such as a bromination that was scaled to 1.1 kg in 90 minutes with a 75% yield [8]. Furthermore, the ability to pressurize flow systems allows solvents to be heated well above their atmospheric boiling points. This enables dramatic rate acceleration and unique reactivity, such as a thermal deprotection performed at 250°C that would not be feasible in standard batch glassware [8].

Within the ongoing scientific discourse comparing flow chemistry with batch organic synthesis, the distinct and enduring advantages of batch systems remain highly relevant for research and development. Batch chemistry, defined as the method where all reactants are combined in a single vessel and the reaction proceeds over a set period, is characterized by its non-interactive and pre-scheduled nature [14] [1]. While continuous flow methods offer compelling benefits for scaled production and hazardous reactions, batch processing provides unparalleled flexibility and simplicity, making it the foundational tool for exploratory synthesis, reaction discovery, and small-scale production in the laboratory [1] [4]. This application note details these inherent advantages, providing structured data and protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in effectively leveraging batch systems.

Key Advantages: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

The choice between batch and flow chemistry is often dictated by the project's stage and goals. The following analysis summarizes the core strengths of batch systems that make them indispensable in a research environment.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Batch and Flow Chemistry Characteristics

| Factor | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible mid-reaction adjustments [1] | Precise, automated control of residence time and temperature [1] |

| Scalability | Challenging at large scale; requires re-optimization [1] | Seamless scale-up by increasing run time or flow rates [1] [4] |

| Initial Setup & Cost | Lower initial cost; simple glassware and stirrers [1] [4] | Higher initial investment for specialized pumps and reactors [1] |

| Operational Flexibility | High; suitable for diverse reaction types and multi-step sequences [1] | Limited; best for specific, optimized reaction conditions [15] [1] |

| Ease of Use & Maintenance | Simple setup and straightforward maintenance [1] [16] | Complex setup requiring expertise in fluid dynamics [1] |

Table 2: Inherent Advantages of Batch Processing Systems

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Flexibility | Allows for real-time adjustments of temperature, mixing, and stepwise reagent addition [1]. | Ideal for exploratory synthesis and optimizing reactions where the pathway is not fully known [1]. |

| Implementation Simplicity | Utilizes well-understood equipment (e.g., round-bottom flasks, stirrer hotplates) with minimal specialized training required [4] [16]. | Reduces barriers to entry, accelerates method development, and allows scientists to focus on chemistry rather than engineering [17] [16]. |

| Facility of Parallelization | Enables multiple reactions to be conducted simultaneously in separate vessels [4]. | Dramatically increases throughput for screening catalysts, reagents, or substrates in early-stage discovery [12]. |

| Quality Control & Debugging | Quality checks can be conducted at the end of each batch, with adjustments made before the next run [15]. | Simplifies troubleshooting and ensures consistent, high-quality outcomes for critical intermediates [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Leveraging Batch Advantages

The following protocols exemplify how the flexibility and simplicity of batch systems can be applied in common research scenarios.

Protocol: Parallel Screening of Reaction Conditions in Batch

This methodology is ideal for rapidly exploring a wide chemical space, such as screening photocatalysts or ligands, a technique widely used in high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [12].

1. Research Objective: To identify the optimal catalyst and base for a model photoredox fluorodecarboxylation reaction [12].

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Materials for Parallel Screening

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Jacketed Reactor Systems (e.g., Datum/Atom) | Provides temperature control for multiple parallel reactions [4]. |

| Magnetic Stirrer Hotplate | Ensures homogeneous mixing within each reaction vessel [4]. |

| DrySyn Multi Position Blocks | Allows for running reactions in vials or round-bottom flasks in parallel on a single hotplate [4]. |

| Multi-Well Plate (96-well) | Serves as a miniature reaction vessel for high-density screening [12]. |

| Lighthouse or Illumin8 Photoreactor | Provides consistent irradiation for parallel photochemical reactions [4]. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Reaction Setup. In a dry, inert atmosphere, prepare separate vials or wells in a multi-well plate for each condition to be tested.

- Step 2: Reagent Dispensing. To each vessel, add the constant substrates (e.g., carboxylic acid, fluorinating agent). Then, add different combinations of photocatalyst and base to the various vessels according to the experimental design.

- Step 3: Reaction Initiation. Seal the reaction vessels and place them on the pre-equilibrated parallel stirrer hotplate. Initiate the reactions by turning on the stirring and the light source.

- Step 4: Monitoring and Quenching. After the predetermined reaction time, quench all reactions simultaneously by removing the light source and cooling the block.

- Step 5: Analysis. Analyze the conversion and yield for each well using analytical techniques such as LC-MS or NMR [12].

Protocol: Multi-Step Synthesis with In-Process Control in Batch

This protocol highlights the flexibility of batch systems for complex, multi-step synthetic sequences.

1. Research Objective: To synthesize a complex drug-like molecule through a sequential three-step process (alkylation, deprotection, cyclization).

2. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 4: Essential Materials for Multi-Step Synthesis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Round-Bottom Flasks (Various Sizes) | Primary reaction vessel for each synthetic step. |

| Overhead Stirrer | Provides efficient mixing for larger volume reactions. |

| Heating Mantle & Recirculating Chiller | Enables precise temperature control from cryogenic to reflux conditions. |

| In-situ FTIR or Sampling Port | Allows for real-time reaction monitoring and endpoint determination [1]. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Alkylation. Conduct the first reaction (alkylation) in a batch reactor. Use in-situ monitoring to confirm reaction completion.

- Step 2: Work-up and Intermediate Isolation. Without transferring to a new system, perform a standard aqueous work-up (quenching, extraction, washing) on the crude reaction mixture. Isolate the intermediate product via filtration or solvent evaporation.

- Step 3: In-Process Adjustment. Based on the yield and purity analysis of the intermediate, the chemist can adjust the stoichiometry or conditions for the subsequent deprotection step—a key flexibility advantage.

- Step 4: Subsequent Steps. The intermediate is then subjected to the deprotection and cyclization steps in the same or a similarly configured batch reactor, with the ability to modify parameters at each stage based on observed outcomes [1].

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for a batch-based screening campaign and the decision pathway for selecting a batch system.

Batch Screening Workflow

Batch System Selection Guide

Within the modern research landscape, both batch and flow chemistry hold critical roles. Batch organic synthesis, with its inherent flexibility for real-time intervention and simplicity of setup and operation, remains the cornerstone of exploratory chemistry, reaction discovery, and initial optimization [1] [4]. Its capacity for parallelization and straightforward quality control makes it exceptionally powerful for the high-throughput experimentation that drives early-stage drug development [12] [15]. By understanding and leveraging these fundamental advantages, researchers and scientists can make informed strategic decisions, employing batch systems to efficiently navigate the complexities of synthetic organic chemistry.

Within the ongoing research discourse comparing flow chemistry to batch organic synthesis, this application note details the fundamental strengths of continuous flow systems. Flow chemistry, defined as the performance of chemical reactions in a continuously flowing stream within a tubular reactor, offers paradigm-shifting advantages over traditional batch processing for specific applications in pharmaceutical research and development [18] [19]. By leveraging enhanced physical parameters, flow systems provide synthetic chemists and process engineers with superior tools for reaction control, process safety, and product consistency. This document provides a quantitative and practical examination of these strengths, supported by structured data and actionable protocols for implementation in a research setting.

Quantifying the Advantages: Flow vs. Batch

The operational benefits of flow chemistry stem from fundamental engineering principles, primarily the high surface-to-volume ratio of flow reactors. The table below summarizes the core performance differentiators.

Table 1: Core Performance Comparison Between Standard Batch and Flow Reactors

| Performance Parameter | Batch Reactor (e.g., 100 mL flask) | Continuous Flow Reactor (e.g., 2 mm tube) | Impact and Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface-to-Volume Ratio [20] | ~80 m²/m³ | ~2,000 m²/m³ | Enables orders-of-magnitude faster heat exchange, preventing hot spots and runaways. |

| Typical Temperature Range [1] | -20 °C to 150 °C | Can significantly exceed 150 °C | Access to novel process windows (e.g., superheated solvents) for faster reaction kinetics. |

| Typical Pressure Range [1] [21] | < 5 bar | 20 - 200 bar | Enables use of gaseous reactants and solvents above their boiling points. |

| Mixing Efficiency [19] [20] | Slower, convection-dependent | Millisecond to second mixing via diffusion | Excellent for fast reactions; prevents side reactions dependent on mixing time. |

| Reactor Utilization [20] | ~30% (GMP environment) | Can exceed 90% | Eliminates downtime for cleaning, filling, and heating/cooling between batches. |

| Inventory of Hazardous Material [18] [1] | Large (full batch volume) | Small (only within reactor at any time) | Intrinsically safer process design; mitigates consequences of a runaway reaction. |

Fundamental Strength 1: Unparalleled Reaction Control

Enhanced Heat and Mass Transfer

The small channel diameters in flow reactors lead to exceptionally high surface-to-volume ratios, facilitating rapid heat transfer [19]. This allows for nearly isothermal reaction conditions, even for highly exothermic transformations like nitrations or organometallic reactions, which are challenging to control in batch [18] [19]. Furthermore, the small dimensions drastically reduce the path for diffusion, leading to mixing on the millisecond scale. This is critical for reactions where the reaction time is shorter than the mixing time, a domain known as "flash chemistry" [19].

Precise Parameter Management

Flow chemistry provides independent control over critical reaction parameters. Residence time, the duration the reaction mixture spends in the reactor, is precisely tuned by adjusting the flow rate and reactor volume [21]. Temperature can be controlled with high accuracy along the entire reactor length. Pressure, regulated by a back-pressure regulator (BPR), keeps solvents in the liquid phase at elevated temperatures and increases the solubility of gases in liquid-phase reactions, accelerating reaction rates [22] [21].

Figure 1: Control Logic of a Flow Chemistry System. Key parameters are managed by specific hardware components to precisely govern reaction kinetics.

Fundamental Strength 2: Inherent Process Safety

The small reactor volume in flow systems, typically on the milliliter scale, drastically reduces the inventory of hazardous materials at any given moment [1] [20]. This "inherently safer design" principle means that even if a reaction runs away, the small volume limits the potential energy release and consequences [18]. This enables researchers to safely handle hazardous intermediates, such as azides, diazo compounds, or reactive organolithium species, which might be deemed too risky to produce on a large scale in batch [12]. Furthermore, the excellent thermal control prevents the accumulation of heat that can lead to thermal runaways. Gaseous reagents can be generated and consumed in-line, avoiding the storage and handling of large quantities of gases [19].

Experimental Protocol 1: Safe Synthesis of a Hazardous Intermediate

Aim: To demonstrate the safe generation and immediate consumption of an organolithium intermediate in flow, a process typically requiring cryogenic conditions in batch.

Background: Organolithium reagents are highly reactive but can undergo deleterious side-reactions (e.g., deprotonation of the electrophile) if mixing is not efficient. Flow chemistry provides the rapid mixing and heat transfer needed to outpace these side reactions safely [19].

Materials:

- Syringe or piston pumps (x2)

- T-mixer (or other suitable static mixer)

- Tubing reactor (e.g., PTFE, PFA, or stainless steel)

- Back-pressure regulator (BPR)

- Cooling bath (if required)

- Collection vessel

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protocol 1

| Item | Function | Specifics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pumps [22] [21] | Precise delivery of reagents. | Syringe pumps for pulse-free flow; piston pumps for high pressure. Chemically resistant wetted parts. |

| Tubing Reactor [22] [21] | The environment where the reaction occurs. | Material: PTFE/PFA for chemical resistance, stainless steel for high pressure/temperature. Diameter influences mixing. |

| Static Mixer [22] [21] | Ensures rapid and homogeneous mixing of streams. | E.g., T-mixer, staggered herringbone micromixer. Critical for fast reactions. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) [22] [21] | Maintains system pressure. | Prevents degassing, increases boiling points, and enhances gas solubility. Can be static or adjustable. |

| Temperature Control Unit [21] | Heats or cools the reactor. | Oven, heating bath, or cooling bath. Provides precise temperature management. |

Procedure:

- Setup: Assemble the flow system as shown in Figure 2. Use chemically compatible tubing and fittings. Pressurize the system with an inert solvent to check for leaks.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate solutions of the starting material (e.g., an aryl halide) in an anhydrous solvent and the base (e.g., tert-butyllithium in hexanes).

- Priming: Load the solutions into the pumps and prime the lines to displace the inert solvent.

- Reaction Execution: Start both pumps simultaneously at the predetermined flow rates to achieve the desired stoichiometry and residence time. The reaction occurs upon mixing in the T-mixer and within the subsequent tubing reactor.

- Quenching & Collection: The reaction stream is directed through the BPR and immediately quenched into a collection vessel containing a quenching agent or directly into a second flow module containing the electrophile.

Key Advantages Demonstrated:

- Safety: The total volume of the reactive organolithium species in the reactor at any time is minimal (microliters to milliliters).

- Control: Residence time is precisely controlled, preventing decomposition.

- Selectivity: Millisecond mixing outcompetes unwanted side-reactions, leading to higher yields and purity [19].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Safe Organolithium Chemistry in Flow.

Fundamental Strength 3: Exceptional Product Consistency

The continuous nature of flow processing ensures that every volume element of the reaction mixture experiences identical conditions of time, temperature, and mixing [18] [3]. This eliminates the batch-to-batch variability common in traditional reactors, where slight differences in heating/cooling rates, mixing efficiency, or reagent addition can lead to significant differences in product quality and yield [23]. The consistent product quality reduces the need for extensive re-processing or purification and simplifies regulatory reporting [20]. Scalability is also more linear and predictable; moving from laboratory discovery to industrial production often involves increasing the runtime or operating reactors in parallel, rather than re-engineering the process for a larger vessel, which often introduces new mixing and heat transfer challenges [18] [1].

Experimental Protocol 2: High-Consistency Gas-Liquid Reaction

Aim: To perform a photochemical Giese-type alkylation using gaseous methane, showcasing enhanced mass transfer and consistent output in flow.

Background: Gas-liquid reactions are often limited by poor mass transfer due to the low solubility of gases in solvents. In batch, this leads to slow, inefficient, and inconsistent reactions. Flow chemistry overcomes this by using pressure to increase gas solubility and creating a large, consistent interfacial area for mass transfer [19].

Materials:

- Liquid pump (syringe or piston)

- Mass Flow Controller (MFC) for gas

- Photoreactor (e.g., a fluoropolymer or glass coil around a light source)

- Back-pressure regulator (BPR)

- Gas-liquid separator (optional)

Procedure:

- Setup: Assemble the flow system as shown in Figure 3. Ensure the photoreactor is compatible with the required wavelength of light.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the alkene substrate and photocatalyst (e.g., tetrabutylammonium decatungstate) in a suitable solvent mixture.

- System Pressurization: With the BPR set to the desired pressure (e.g., 45 bar), start the liquid pump and MFC to establish a steady flow of both liquid and gas phases.

- Reaction Execution: The gas-liquid stream enters the photoreactor, where it is irradiated. The high pressure forces the gaseous reagent into the liquid phase, and the segmented flow pattern ensures efficient mass transfer.

- Depressurization and Collection: The output stream passes through the BPR, which drops the pressure to ambient. The product is collected in a liquid state, and any excess gas is vented safely.

Key Advantages Demonstrated:

- Consistency: Continuous operation and controlled parameters yield a product with uniform quality over time.

- Mass Transfer: The flow regime dramatically improves gas-liquid contact, enabling reactions that are impractical in batch [19].

- Process Window: Allows access to high-pressure and high-temperature conditions safely, accelerating reaction rates.

Figure 3: Experimental Workflow for a High-Pressure Gas-Liquid Photochemical Reaction in Flow.

For researchers engaged in organic synthesis for drug development, the transition from traditional batch methods to continuous flow chemistry represents a significant paradigm shift. This shift requires a fundamental reconceptualization of key reaction parameters, moving from a time-dependent process to a space-dependent one [24]. Within the context of flow chemistry versus batch organic synthesis, understanding the translation of "reaction time" into "residence time" and the critical role of flow rates is essential for harnessing the full potential of flow-based technologies, including improved control, safety, and scalability [1] [25]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these parameters and offers practical protocols for their implementation in a research setting.

Comparative Analysis of Key Parameters

The core difference between batch and flow processing can be understood by comparing how key variables are defined and controlled. Table 1 summarizes the direct comparison of these fundamental parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Technical Parameters in Batch vs. Flow Chemistry

| Parameter | Batch Chemistry | Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Time Metric | Reaction time (clock time) [24] | Residence Time (τ) [24] |

| Definition | Time the vessel is stirred under fixed conditions [24] | τ = V / q, where V is reactor volume and q is total flow rate [24] [26] |

| Control Mechanism | Kinetics controlled by reagent exposure time [24] | Kinetics controlled by flow rates of reagent streams [24] [27] |

| Stoichiometry | Set by molar ratio of reagents added to the vessel [24] | Set by the ratio of flow rates and molarities of reagent streams [24] [25] |

| Heat & Mass Transfer | Limited by vessel size and stirring efficiency; can create gradients [1] | Enhanced due to high surface-area-to-volume ratio and rapid diffusion mixing [24] [25] [28] |

| Concentration Profile | Varies over time at a fixed point in space [24] [27] | Defined within space (the reactor) and is constant at steady state [24] [27] |

| Scalability | Complex scale-up; often requires re-optimization [1] | Simplified scale-up; often by increasing run time or flow rates [1] [25] |

The Concept of Residence Time Distribution

A critical concept in flow chemistry that has no direct analog in batch is the Residence Time Distribution (RTD). In an ideal batch reactor, all molecules experience the same reaction time. In a flow system, however, fluid dynamics mean that not all molecules spend the same amount of time in the reactor zone [26] [29]. This results in a distribution of residence times.

The RTD is vital for product quality and impurity control. A narrow RTD ensures that all product molecules experience similar reaction conditions, preventing situations where some material is under-reacted (short residence time) while other material is over-reacted (long residence time), which can lead to increased impurity profiles [26]. Reactor design—such as using a series of Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors (CSTRs) or structured plug flow reactors—can be optimized to achieve a narrower RTD, thereby intensifying throughput and improving selectivity [26] [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Residence Time in a Tubular Flow Reactor

This protocol outlines the methodology for calculating and establishing the residence time in a simple coil reactor, which is foundational for any flow chemistry experiment.

Principle: The mean residence time (τ) is defined as the reactor volume (V) divided by the total volumetric flow rate (q) of all combined reagent streams: τ = V / q [24] [26].

Equipment & Materials:

- Flow chemistry system comprising:

Procedure:

- Reactor Volume Determination: Calculate the internal volume (V) of the coil reactor based on its internal diameter and length.

- System Priming: Prime the entire flow path, including pumps, mixer, and reactor, with a suitable solvent. Ensure the system is liquid-filled and free of gas bubbles by applying back-pressure [28].

- Define Target Residence Time: Select a desired residence time (τ) for the reaction, for example, 5 minutes.

- Calculate Flow Rates: Based on the known reactor volume (V) and target residence time (τ), calculate the required total flow rate (q): q = V / τ. For example, for a 10 mL reactor and a 5-minute residence time, q = 10 mL / 5 min = 2 mL/min.

- Set Individual Flow Rates: Program the pumps to deliver the individual reagent streams such that their sum equals the total flow rate (q). The ratio of these individual flows will control the stoichiometry of the reaction [24] [25].

- Initiate Reaction and Collection: Start the pumps and begin collecting the effluent from the system. Note that the system will take some time to reach a steady state, where product composition becomes constant [24] [27]. Discard the product collected during this initial equilibration period.

Protocol 2: Investigating Reaction Kinetics by varying Flow Rate

This protocol describes a method for rapidly probing reaction kinetics by systematically varying the residence time through flow rate adjustments.

Principle: By varying the total flow rate (q) through a reactor of fixed volume (V), the residence time (τ) is directly altered. Observing the change in conversion or yield with residence time provides key kinetic data [28].

Equipment & Materials:

- Same as Protocol 1.

- In-line or at-line analytical tool (e.g., HPLC, GC, NMR) [12].

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Establish the flow system as described in Protocol 1, using the reagents for the reaction under investigation.

- Define Flow Rate Range: Select a range of total flow rates (q) that will provide a series of residence times (τ). For instance, if V = 10 mL, a flow rate of 10 mL/min gives τ = 1 min, 5 mL/min gives τ = 2 min, and so on.

- Automated Screening: If using an automated system, program a sequence of experiments where the flow rate is stepped through the predefined range. Each condition should be maintained long enough to reach a new steady state and collect a representative sample [12].

- Sample Collection and Analysis: For each residence time, collect the product stream. Analyze each sample using an appropriate analytical method to determine conversion and selectivity.

- Data Analysis: Plot the results (e.g., conversion vs. residence time) to understand the reaction kinetics and identify the optimal residence time for maximum yield or selectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Transitioning from batch to flow requires familiarity with specific equipment and its function. Table 2 details the key components of a typical flow chemistry setup.

Table 2: Key Components of a Flow Chemistry System

| Component | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Pumps | To deliver reproducible quantities of solvents and reagents at a precisely controlled flow rate [24] [30]. | Types include syringe, peristaltic, or piston pumps. Accuracy is critical for controlling stoichiometry and residence time. |

| Mixing Unit (T-piece/Static Mixer) | The primary point where separate reagent streams are combined [24] [30]. | Efficient mixing is vital to initiate the reaction correctly. Static mixers provide superior mixing compared to a simple T-piece. |

| Flow Reactor | Provides the residence time and controlled environment (temp, pressure) for the reaction to occur [24]. | Can be coil (for single-phase) [30], packed bed (for catalysts) [24] [30], or photoreactor [24] [12]. Material (e.g., PTFE, steel) must be chemically compatible. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) | Controls the system pressure by providing a restriction at the outlet [24] [28]. | Essential for preventing outgassing, maintaining a liquid-filled system for pumps, and enabling use of solvents above their boiling points. |

| Heating/Cooling Unit | Maintains the reactor at a precise, constant temperature [24]. | The high surface-area-to-volume ratio allows for excellent and rapid heat transfer. |

| In-line Analytics | To monitor reaction progress in real-time [12]. | Includes in-line IR, UV, or MS. Enables rapid feedback and process control. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual and practical workflow for transitioning a reaction from batch to flow, emphasizing the shift from a time-based to a space-based paradigm and the key parameters involved.

Flow Chemistry Parameter Workflow

Mastering the concepts of residence time and flow rate control is fundamental for researchers aiming to leverage continuous flow chemistry in organic synthesis and drug development. This parameter shift from batch's reaction time enables superior control over reaction kinetics, safety, and selectivity. The experimental protocols and toolkit detailed in this application note provide a foundation for scientists to begin translating batch reactions into efficient, scalable, and more reproducible flow processes, ultimately accelerating research and development timelines.

Practical Applications: Where Flow and Batch Chemistry Excel

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly embracing continuous flow chemistry as a transformative technology for the synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). This shift is driven by the need to overcome limitations inherent in traditional batch processing, including manufacturing issues that can lead to critical drug shortages [31]. Flow chemistry involves the continuous pumping of reactants through a reactor system, enabling precise control over reaction parameters and facilitating continuous product collection [1]. This approach offers substantial advantages for API synthesis, including enhanced process control, improved safety profiles when handling hazardous intermediates, superior heat and mass transfer characteristics, and more straightforward scalability from laboratory to production scale [31] [1]. The closed nature of flow systems also protects operators from direct contact with potent or dangerous compounds, a significant consideration in pharmaceutical manufacturing [31]. This article details specific case studies on the flow synthesis of Valsartan and Imatinib, providing detailed protocols and data to exemplify these advantages within the broader context of a thesis comparing flow and batch organic synthesis.

Case Study 1: Multistep Continuous Flow Synthesis of a Valsartan Precursor

Background and Rationale

Valsartan is a widely prescribed angiotensin II receptor blocker used for treating hypertension and chronic heart failure [32]. The traditional synthetic route, first patented by Ciba-Geigy in 1991, suffered from a poor overall yield of less than 10% and involved highly toxic organotin reagents, leading to potential API contamination [32]. Recent recalls of valsartan generics due to carcinogenic nitrosamine impurities have further highlighted the need for robust, alternative synthesis methods [32]. A continuous flow approach addresses these issues by enabling precise control over reaction conditions, minimizing human exposure to hazardous substances, and ensuring higher process consistency [32] [31].

Synthetic Strategy and Workflow

The developed continuous process synthesizes a key valsartan precursor through a three-step, telescoped sequence [32]:

- N-Acylation: Reaction of boronic acid pinacol ester (11) with valeryl chloride.

- Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling: The key step, coupling intermediate 12 with 2-halobenzonitrile (7b-c).

- Methyl Ester Hydrolysis: Conversion of the biphenyl ester 5 to the final precursor acid 13.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these steps into a continuous process.

Key Experimental Protocol

Objective: To synthesize a valsartan precursor (13) via a three-step continuous flow process [32].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Boronic acid pinacol ester (11) | Core building block bearing the protected boronic ester functionality. |

| Valeryl chloride | Acylating agent for the first N-acylation step. |

| 2-Halobenzonitrile (7b-c) | Coupling partner in the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling. |

| Heterogeneous Pd-catalyst (Ce0.20Sn0.79Pd0.01O2-δ) | Catalyst for the key Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling, packed into a fixed-bed reactor. |

| Base (e.g., K2CO3) | Provides the basic environment necessary for the Suzuki coupling and hydrolysis steps. |

| Aqueous Solvent System (EtOH:H2O) | Reaction medium for the cross-coupling; water hydrolyzes the boronic ester in-line to the more reactive boronic acid. |

| Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) tubing | Material for constructing coil reactors, chosen for chemical resistance. |

| HPLC column hardware | Serves as the housing for the packed-bed catalyst (Plug & Play reactor). |

| Syringe or HPLC pumps | Provide precise, continuous feeding of reagent solutions. |

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Configure the system comprising two coil reactors (for N-acylation and hydrolysis) and one packed-bed reactor (PBR) for the cross-coupling.

- N-Acylation (Step 1): Pump solutions of boronic ester 11 and valeryl chloride through a T-mixer into the first coil reactor. Use a residence time of 3 minutes at 50 °C. The output is intermediate 12.

- Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling (Step 2): Combine the output stream from Step 1 directly with a stream of 2-halobenzonitrile 7b-c. Pass the combined stream through the PBR containing the heterogeneous Pd-catalyst. Use a residence time of 15 minutes at 75 °C in an EtOH:H2O (7:3) solvent mixture. The output is biphenyl ester 5.

- Methyl Ester Hydrolysis (Step 3): Combine the output stream from Step 2 with an aqueous basic solution (e.g., NaOH). Pass the mixture through the second coil reactor at 60 °C with a residence time of 10 minutes to saponify the ester.

- Collection and Work-up: Collect the effluent and acidify to precipitate the product. Filter and dry to obtain the pure valsartan precursor 13.

Results and Data Analysis

The optimized continuous flow process demonstrated significant performance metrics, as summarized below.

Table 1: Quantitative Data for Valsartan Precursor Flow Synthesis [32]

| Process Metric | Performance Data |

|---|---|

| Overall Yield | Up to 96% |

| Key Step (Suzuki) Catalyst | Ce0.20Sn79Pd0.01O2-δ |

| Reactor Types Used | Coil reactors (Steps 1 & 3) + Packed-Bed Reactor (Step 2) |

| Key Advantage vs. Legacy Batch | Avoids toxic tin reagents; eliminates potential API contamination. |

Case Study 2: Flow-Based Synthesis of Imatinib

Background and Rationale

Imatinib (marketed as Gleevec) is a revolutionary therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia and gastro-intestinal stromal tumors [31]. Its synthesis in continuous flow showcases the technology's applicability to complex, multi-step API manufacturing, moving away from traditional batch-wise production [33]. The flow synthesis was developed to improve efficiency and control in the preparation of this critical life-saving drug [33].

Synthetic Strategy

While the search results confirm the existence of a flow-based synthesis for Imatinib [31] [33], the specific reaction steps and intermediates are not detailed in the provided excerpts. The synthesis likely involves a sequence of reactions, such as condensations and cyclizations, to construct the complex molecular architecture of Imatinib from simpler building blocks. The general approach would leverage the standard advantages of flow chemistry, such as precise residence time control and handling of unstable intermediates.

Key Experimental Protocol

Objective: To synthesize the API Imatinib via a continuous flow process [33].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- Note: Specific reagents are not listed in the provided search excerpts. The materials would include the necessary aromatic amines, heterocyclic carboxylic acids or derivatives, and other building blocks required to form the core structure of Imatinib.

- Solvents: Appropriate anhydrous solvents for the specific reactions (e.g., DMF, THF, MeCN).

- Reagents: Coupling agents, bases, and catalysts as required by the specific synthetic route.

- Pumps: Syringe or piston pumps for precise reagent delivery.

- Tubing Reactors: Chemically resistant tubing (e.g., PFA, PTFE) of various volumes for reaction steps.

- Heating Units: Ovens or oil baths to maintain required reaction temperatures.

Procedure: The general procedure for a multi-step flow synthesis, as applied to Imatinib, involves:

- System Configuration: Assembling a series of pumps, mixing tees, and reactor coils in a sequence that matches the synthetic route.

- Solution Preparation: Dissolving starting materials in suitable solvents at predetermined concentrations.

- Continuous Processing: Pumping the reactant solutions through the flow system. The streams meet at mixing tees and then pass through heated reactor coils, where each chemical transformation occurs.

- In-line Monitoring and Quenching: Optionally, using in-line analytics (e.g., IR, UV) to monitor reaction progress. The output stream may be quenched in-line or collected for off-line workup.

- Isolation: The crude Imatinib collected from the flow system is typically isolated and purified using standard techniques like crystallization or chromatography to achieve pharmaceutical purity.

Comparative Analysis: Flow vs. Batch Synthesis

The case studies for Valsartan and Imatinib, along with other examples from the literature, provide a strong foundation for comparing flow and batch methodologies in a thesis context. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics.

Table 2: Flow vs. Batch Chemistry Comparative Analysis [31] [1]

| Factor | Batch Chemistry | Continuous Flow Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Process Control | Flexible mid-reaction adjustments. | Superior precise, automated control over time and temperature. |

| Scalability | Challenging; often requires re-optimization. | Seamless; often scaled by increasing run time or numbering up. |

| Safety | Higher risk with exothermic or hazardous reactions. | Enhanced safety via small reactor volumes and contained environment. |

| Productivity | Limited by batch downtime (cleaning, filling). | Continuous, high-throughput operation. |

| Product Quality | Potential for batch-to-batch variability. | High consistency and reproducibility. |

| Environmental Impact | Typically higher solvent and energy use per kg of product. | Often lower environmental footprint (Process Intensification). |

Advanced Flow Chemistry Tool: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

Beyond experimental optimization, computational methods are playing an increasing role in flow process development. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulates fluid flow, heat transfer, and chemical reactions within a reactor. A study on the flow synthesis of a Dolutegravir intermediate demonstrated that CFD simulations could accurately identify the most significant factors affecting product yield (residence time and temperature), showing strong correlation with experimental results [34]. This approach can significantly reduce the time and material resources required for initial process screening and optimization.

The case studies of Valsartan and Imatinib provide compelling evidence for the integration of continuous flow chemistry into the modern API synthesis toolkit. The Valsartan process, achieving a 96% overall yield in a telescoped three-step sequence, demonstrates how flow chemistry can rectify the shortcomings of traditional batch routes, offering a safer, more efficient, and higher-yielding alternative [32]. The synthesis of Imatinib further confirms the technology's relevance for complex, high-value pharmaceuticals [33]. When framed within a thesis on flow versus batch synthesis, these examples powerfully illustrate the core advantages of flow chemistry: enhanced process control, inherent safety, easier scalability, and superior overall efficiency. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to evolve, the adoption of enabling technologies like flow chemistry, supported by advanced tools such as CFD, is poised to become the standard for the next generation of drug manufacturing.

Leveraging Flow for Hazardous Reactions and Unstable Intermediates

Within the broader debate comparing flow chemistry to traditional batch organic synthesis, the ability to safely and efficiently handle hazardous reactions and unstable intermediates represents a pivotal advantage of continuous flow systems. In batch processing, the limitations of round-bottom flasks often lead to challenges with heat and mass transfer, making exothermic reactions dangerous and fast, selectivity-sensitive reactions difficult to control [35]. Flow chemistry, which involves the continuous pumping of reagents through a dedicated reactor [8], directly addresses these shortcomings. By offering superior control over reaction parameters and minimizing the inventory of hazardous substances, flow technology unlocks new synthetic possibilities and enhances safety in research and development, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry [35] [36].

This application note provides a detailed examination of how flow chemistry mitigates the risks associated with challenging transformations. It offers structured protocols, quantitative performance comparisons, and visual guides to empower researchers in implementing these techniques.

Key Advantages for Hazardous Chemistry

The fundamental properties of flow reactors—specifically their high surface-area-to-volume ratio and continuous operation—confer several critical benefits for managing hazardous reactions and unstable intermediates [36].

- Enhanced Safety: The small reactor volumes in continuous flow systems drastically reduce the inventory of hazardous substances present at any given moment. This inherent containment minimizes the risks associated with potential uncontrolled decomposition or explosions [8]. For instance, unstable intermediates like diazonium salts can be generated and consumed on-demand, preventing their dangerous accumulation [37] [8].

- Superior Thermal Control: The high surface-to-volume ratio of microreactors enables extremely efficient heat transfer [35]. This allows for the safe management of highly exothermic reactions by preventing the formation of "hot spots" and mitigating the risk of thermal runaways, which are common challenges in batch reactors [35] [36]. Consequently, reactions requiring cryogenic conditions in batch can often be performed at significantly higher, more practical temperatures in flow [37].

- Precise Reaction Control: Flow systems provide unparalleled control over residence time and mixing. By using static mixers and microreactors, mixing times can be reduced to the millisecond range, allowing chemists to outpace very rapid, undesired side reactions such as anionic Fries rearrangements or the decomposition of organolithium intermediates [35]. This precise control directly translates to improved selectivity and yield.

Table 1: Comparison of Flow vs. Batch Performance for Hazardous Reactions

| Reaction Type | Batch Performance | Flow Performance | Key Flow Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organolithium Chemistry [37] | Requires cryogenic conditions (e.g., -78 °C); significant impurity formation. | Can be run at room temperature (+20 °C); >96% conversion; impurities <0.1%. | Excellent heat transfer prevents runaway exotherms, enabling safer operation at higher temperatures. |

| Diazotization [8] | 56% yield; risk of explosion from intermediate accumulation. | 90% yield; 1 kg product in 8 hours. | On-demand generation and immediate consumption of unstable diazonium intermediate. |

| Photochemical Bromination [8] | Challenges with uneven light penetration and scaling. | 1.1 kg in 90 min with 75% yield. | Superior light penetration in narrow channels ensures uniform irradiation. |

| Hydride Reduction [8] | Prone to side reactions and exotherm control issues. | 96% isolated yield with suppressed side reactions. | Superior thermal control and mixing efficiency. |

| Gas-Liquid Reactions (e.g., Alkane functionalization) [35] | Mass transfer limited; slow and inefficient. | Enabled by pressurized flow; 42% yield for methane functionalization. | Pressurization increases gas solubility; enhanced mass transfer. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Safe Handling of Organolithium Reagents

This protocol is adapted from a case study where a highly exothermic n-BuLi reaction was successfully translated from batch to flow, achieving high conversion at ambient temperature [37].

1. Reaction Scheme: Lithiation of a Key Starting Material (KSM) followed by carboxylation with CO₂.

2. Objective: To execute a lithiation-carboxylation sequence safely at room temperature, minimizing impurity formation and reducing solvent consumption compared to batch processing.

3. Experimental Setup & Workflow:

4. Materials & Equipment:

- Reactors: Two microreactors (e.g., PFA or stainless steel coil reactors).

- Pumping System: Two HPLC pumps for liquid feeds (KSM and n-BuLi).

- Gas Introduction System: A method for introducing and controlling CO₂ flow (e.g., a mass flow controller).

- Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR): To maintain pressure within the system.

- Reagents: Key Starting Material (KSM), n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi) in hexane, anhydrous solvent for KSM, and carbon dioxide (CO₂) gas.

5. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Solution Preparation: Dissolve the KSM in a suitable anhydrous solvent. Load this solution and the commercial n-BuLi/hexane solution into separate reservoirs for the HPLC pumps. 2. System Priming & Stabilization: Prime the pumps and flow lines with their respective solvents. Start the pumps and set the flow rates according to the desired stoichiometry and residence time. For the case study, the overall residence time was less than 1 minute [37]. 3. Reaction Execution: With the pumps running, pass the reaction mixture through the first microreactor (R1) where lithiation occurs. The outlet stream from R1 is immediately mixed with a stream of CO₂ in the second microreactor (R2) to form the carboxylic acid product. 4. Product Collection & Workup: The resulting mixture exits through the BPR and is collected in a suitable vessel. The product can be isolated using standard work-up procedures (e.g., quenching, extraction, and purification).

6. Key Parameters & Optimization Notes:

- Temperature: The reaction was successfully conducted at +20 °C (ambient temperature), whereas batch required cryogenic conditions below -50 °C [37].

- Residence Time: The total residence time for both steps was optimized to be under 1 minute.

- Result: This flow process achieved an IPC conversion of >96% with all known and unknown impurities well controlled below 0.1%.

- Green Chemistry Benefits: The flow process reduced solvent consumption by approximately 50% and utility costs by about 70% compared to the batch process [37].

Protocol 2: Management of Unstable Diazonium Intermediates

This protocol outlines the on-demand generation and immediate consumption of a diazonium intermediate, a class of compounds known for their explosive potential in batch [8].

1. Reaction Scheme: Diazotization of an aniline followed by a subsequent coupling (e.g., azo-coupling) or functionalization reaction.

2. Objective: To safely generate a diazonium intermediate and react it in a telescoped process without isolation, achieving higher yield and throughput than batch methods.

3. Experimental Setup & Workflow:

4. Materials & Equipment:

- Reactors: Two microreactors or tubular coils.

- Pumping System: Three HPLC or syringe pumps for the aniline/acid mixture, NaNO₂ solution, and coupling partner.

- Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR): To maintain system pressure and prevent gas bubble formation.

- Temperature Control: Chillers or heaters to maintain the diazotization at a low temperature (e.g., 0-5 °C).

5. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the aniline starting material in a dilute aqueous acid (e.g., HCl). Prepare separate aqueous solutions of sodium nitrite (NaNO₂) and the coupling partner. 2. System Assembly & Cooling: Set up the flow system as shown in the diagram. Cool the diazotization microreactor (R1) to 0-5 °C using a cooling bath or Peltier cooler. 3. Reaction Execution: Start all three pumps. The aniline/acid stream and NaNO₂ solution are combined in the first microreactor (R1) to generate the diazonium salt. The outlet of R1 is immediately mixed with the stream of the coupling partner in the second reactor (R2). The residence time in R2 is controlled to allow complete reaction. 4. Product Collection: The final mixture is passed through a BPR and collected. The desired product (e.g., an azo dye) can be isolated by filtration or extraction.

6. Key Parameters & Optimization Notes:

- Safety: The diazonium intermediate is generated in small quantities and consumed immediately, minimizing accumulation. This is the core safety feature of the flow process [8].

- Yield & Productivity: The flow process achieved a 90% yield, a significant improvement over the 56% obtained in batch. Furthermore, it enabled the production of 1 kg of product in just 8 hours [8].

- Residence Time: Residence times in the diazotization reactor are typically kept short (seconds to a few minutes) to minimize decomposition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of flow chemistry for hazardous reactions relies on a set of core components and tools. Understanding the function of each element is crucial for designing and troubleshooting a flow system.

Table 2: Essential Components of a Flow Chemistry Setup for Hazardous Reactions

| Item | Function & Description | Relevance to Hazardous Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Microreactor / Chip Reactor [8] | A reactor with micro-scale channels; offers extremely high surface-to-volume ratio. | Enables rapid heat exchange to control exotherms and fast mixing to outpace side reactions. |

| Tubular/Coil Reactor [8] | Versatile, durable reactor made of PFA, PTFE, or steel; provides near-plug flow behavior. | Ideal for photochemistry (uniform light penetration) and general use with corrosive reagents. |

| Packed-Bed Reactor (PBR) [8] | A tube packed with heterogeneous catalyst (e.g., for hydrogenation) or immobilized enzymes. | Simplifies catalyst handling and recycling, and allows safe use of gases like H₂ in a continuous stream. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator (BPR) [35] [8] | A device that maintains a set pressure upstream in the flow system. | Essential for keeping gaseous reagents in solution (e.g., CO, H₂, light alkanes) and preventing bubble formation. |

| HPLC/Syringe Pumps [8] | Pumps that deliver precise and pulseless flows of reagents. | Critical for maintaining accurate stoichiometry and stable residence times, ensuring reproducible results. |

| Static Mixer Elements [35] | Components integrated into the flow path that enhance fluid mixing by splitting and recombining streams. | Achieves millisecond mixing, crucial for reactions where reaction time is shorter than mixing time (e.g., organolithium chemistry). |

The transition from batch to flow chemistry represents a paradigm shift in how synthetic chemists approach hazardous reactions and unstable intermediates. As demonstrated through the protocols and data herein, flow technology provides a robust framework for enhancing safety, improving efficiency, and achieving superior reaction control. The ability to conduct organolithium chemistry at ambient temperature, manage explosive diazonium intermediates at scale, and seamlessly telescope multi-step processes underscores the transformative potential of continuous flow systems. For researchers in drug development and fine chemical synthesis, adopting these methodologies not only mitigates risk but also accelerates the entire development pipeline, from early R&D to scaled-up production. Integrating flow chemistry as a core component of the synthetic toolbox is a decisive step towards more sustainable, safe, and productive research.

Within the broader context of flow chemistry versus batch organic synthesis research, continuous flow methods have emerged as a transformative platform for performing chemical transformations that are challenging, inefficient, or hazardous in traditional batch reactors. While batch chemistry remains the default method for many research applications due to its simplicity and flexibility, continuous flow chemistry provides superior control, safety, and scalability for specialized reactions [1]. This application note details specific protocols and advantages for implementing three key classes of enabling reactions—photochemical, electrochemical, and high-pressure transformations—within continuous flow systems, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical research and development.

The fundamental principle underlying flow chemistry's advantage for these reaction classes stems from enhanced mass and heat transfer characteristics in narrow tubing or microreactors, precise residence time control, and the ability to safely handle reactive intermediates and extreme conditions that would be problematic in conventional batch vessels [12] [38]. These technical capabilities align with growing industry demands for green chemistry principles, including reduced solvent consumption, minimized waste generation, and improved energy efficiency [38] [39].

Comparative Analysis: Flow vs. Batch for Advanced Transformations

Table 1: Systematic comparison of reaction capabilities in batch versus flow chemistry

| Reaction Parameter | Batch Reactors | Continuous Flow Reactors |

|---|---|---|

| Photochemical Efficiency | Poor light penetration; non-uniform irradiation [40] | Uniform light distribution; controlled path length [12] [40] |

| Temperature Control | Limited heat transfer in large volumes [1] | Excellent heat transfer due to high surface-to-volume ratio [1] [38] |

| Pressure Management | Limited to reactor pressure rating; safety concerns [1] | Easily pressurized; enhanced safety with small volumes [41] [39] |

| Reaction Scale-Up | Often requires re-optimization; heat/mass transfer limitations [1] [12] | Seamless scale-up via prolonged operation or numbered-up systems [1] [38] |

| Handling Hazardous Intermediates | Accumulation in large volumes increases risk [1] | In-situ generation and immediate consumption; minimal inventory [12] [41] |

| Process Safety | Higher risk for exothermic or high-pressure reactions [1] | Superior safety profile due to small reactor volume [1] [38] |

| Reaction Optimization | Sequential experimentation; plate-based HTE with limitations [12] | Continuous parameter adjustment; integration with PAT and AI [12] [38] |