From Milligram to Kilogram: A Modern Guide to Scaling Up Optimized Organic Reactions

Scaling up optimized laboratory reactions to industrial production is a critical, high-risk step in drug development and fine chemical manufacturing.

From Milligram to Kilogram: A Modern Guide to Scaling Up Optimized Organic Reactions

Abstract

Scaling up optimized laboratory reactions to industrial production is a critical, high-risk step in drug development and fine chemical manufacturing. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and development professionals, addressing the foundational principles, modern methodologies, and practical challenges of process scale-up. It explores the paradigm shift from traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization to data-driven approaches leveraging high-throughput experimentation (HTE) and machine learning (ML). The content covers essential troubleshooting strategies for common scale-up issues and emphasizes rigorous validation techniques to ensure process robustness, safety, and economic viability from the kilo lab to commercial manufacturing.

The Scale-Up Paradigm: Bridging the Gap Between Lab and Plant

The transition of a chemical synthesis from laboratory milligram scale to industrial kilogram production, known as scale-up, represents a critical phase in the development of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and specialty materials. This process involves far more than simply using larger vessels; it requires a fundamental re-evaluation of reaction parameters, safety protocols, and purification strategies to ensure the process is robust, cost-efficient, and reproducible at larger scales [1]. Within the broader context of scaling up optimized organic reactions, this shift from discovery to production presents unique interdisciplinary challenges that span chemical engineering, process chemistry, and metabolic engineering. The successful translation of a synthetic route is a key determinant in reducing the time and cost of bringing promising molecules to market [2].

Key Challenges in Scale-Up

Scaling up chemical reactions introduces a new dimension of complexity that is often negligible at small scales. The primary challenges can be categorized as follows.

Heat and Mass Transfer

The most significant difference upon scale-up is the decreasing surface-area-to-volume ratio in larger reactors. In small-scale laboratory glassware, heat generated by a reaction can be dissipated efficiently. In large vessels, heat accumulation becomes a serious risk, potentially leading to thermal runaway reactions, decomposition, or the formation of hazardous side products [3]. Similarly, mass transfer limitations can affect the efficiency of mixing, leading to concentration gradients and inconsistent reaction rates. The use of overhead stirrers is recommended for larger, thicker mixtures to prevent hot spots and ensure consistent mixing, as magnetic stir bars become ineffective [3].

Reaction Reproducibility and Heterogeneity

A reaction that performs flawlessly in milligrams may fail entirely when scaled. As noted in a scale-up synthesis of Nannocystin A, a vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction became unreproducible at a 5-gram scale, with yields dropping from an acceptable level to 10-20% for reasons not immediately apparent [4]. This highlights the capricious nature of some transformations under different physical conditions. Furthermore, in bioreactors, culture heterogeneity can occur, where cells experience varying microenvironments (e.g., differing nutrient and oxygen levels) throughout the vessel, leading to inconsistent performance [2].

Safety and Hazard Management

The consequences of a runaway reaction or equipment failure are magnified with larger quantities of materials. Scale-up reactions account for a number of laboratory accidents annually [3]. A comprehensive Reaction Risk Assessment is essential before scaling any reaction. This includes reviewing scientific literature, SDSs, and consulting resources like Bretherick's Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards [3]. Key safety considerations include:

- Venting and Headspace: Reaction vessels should be at least twice the volume of all added substances to allow for pressure release and massive gas evolution [3].

- Temperature Monitoring and Control: Using a thermocouple to monitor the internal reaction temperature is critical, as it can differ significantly from the external oil bath. Heating mantles with probes are preferred over oil baths for large-scale reactions [3].

- Solvent and Reagent Selection: Safer alternatives should be considered, such as replacing peroxide-forming THF with 2-MeTHF, or diethyl ether with tert-butyl methyl ether [3].

Process Economics and Environmental Impact

At an industrial scale, the cost of raw materials, waste disposal, and processing time become paramount. The intense use of toxic solvents in the synthesis of materials like Metal Organic Frameworks (MOMs) imposes significant environmental and production hazards, making them less competitive compared to cheaper alternatives like zeolites [5]. Process optimization must therefore focus on atom economy, solvent recycling, and minimizing purification steps.

Table 1: Summary of Key Scale-Up Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Manifestation at Scale | Potential Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Transfer | Thermal runaway, decomposition | Use of internal temperature probes; jacketed reactors for cooling; controlled reagent addition [3]. |

| Mixing & Mass Transfer | Reaction heterogeneity; hot spots; inconsistent yields | Use of overhead stirring; computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling; redesign of reactor internals [2] [3]. |

| Reproducibility | Unpredictable yield drop; new impurity profiles | Rigorous front-run testing with new reagent lots; "scale-down" simulation to identify sensitive parameters [2] [4]. |

| Safety | Increased potential for explosive events; toxic gas release | Reaction Risk Assessment; incremental scale-up (max 3-fold per step); adequate vessel headspace [3]. |

| Economic & Environmental Cost | High solvent consumption; expensive purification | Solvent substitution; route re-design to avoid sensitive intermediates; use of scavengers for cleaner workups [1] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Scale-Up

The following protocol, inspired by the multi-gram synthesis of Nannocystin A, outlines a systematic approach to scaling a challenging chemical transformation.

Protocol: Keck Asymmetric Vinylogous Aldol Reaction for C-C Bond Formation

Background: This protocol was developed to replace an unreliable Kobayashi vinylogous Mukaiyama aldol reaction during the scale-up synthesis of a key fragment of Nannocystin A. The original method suffered from irreproducible yields (5-20%) upon scaling to 5 grams, likely due to sensitivity to the Lewis acid (TiCl4) and reactant decomposition [4]. The Keck method using Ti(OiPr)₄ and (R)-BINOL provided a more robust and safer alternative.

Objective: To reproducibly couple aldehyde 21 with vinylketene silyl acetal 25 on a 20-gram scale to produce adduct 26 with high enantioselectivity [4].

Materials and Equipment:

- Reagents: Aldehyde 21, Silyl Acetal 25, Titanium(IV) isopropoxide (Ti(OiPr)₄), (R)-BINOL, anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM), Molecular Sieves (4Å).

- Glassware: Oven-dried multi-neck round-bottom flask (minimum 5x reaction volume).

- Equipment: Overhead mechanical stirrer, thermocouple probe, dual-manifold Schlenk line for inert atmosphere, dry ice/acetone cooling bath (-78 °C).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Inert Atmosphere Setup: Assemble the reaction flask equipped with an overhead stirrer shaft and a thermocouple under a positive pressure of nitrogen or argon.

- Chiral Complex Formation: Charge the flask with (R)-BINOL (1.1 equiv) and activated 4Å molecular sieves. Add anhydrous DCM (0.1 M relative to BINOL) and cool the mixture to -78 °C. Add Ti(OiPr)₄ (1.0 equiv) dropwise via syringe. Stir the resulting mixture vigorously for 30 minutes at -78 °C to form the active chiral titanium-BINOL complex.

- Aldehyde Addition: Dissolve aldehyde 21 (1.0 equiv) in a minimal volume of anhydrous DCM. Add this solution dropwise to the stirring chiral complex at -78 °C.

- Silyl Acetal Addition: Dissolve silyl acetal 25 (1.5 equiv) in anhydrous DCM. Add this solution dropwise to the reaction mixture, maintaining the temperature at -78 °C.

- Reaction Monitoring: Stir the reaction at -78 °C for 30 minutes, then allow the cooling bath to warm to 0 °C over 1-2 hours. Continue stirring at 0 °C for 8-10 hours. Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS.

- Quenching: Once complete, carefully quench the reaction by adding a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate (or Rochelle's salt) dropwise with vigorous stirring.

- Work-up: Warm the mixture to room temperature. Separate the organic layer and extract the aqueous layer with DCM (3x). Combine the organic extracts, wash with brine, dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product 26 by flash column chromatography on silica gel.

Analysis: The expected yield is >55% with an enantiomeric excess (e.e.) of 85%. The product 26 can be advanced to the next synthetic step (e.g., methylation with Ag₂O and CH₃I) [4].

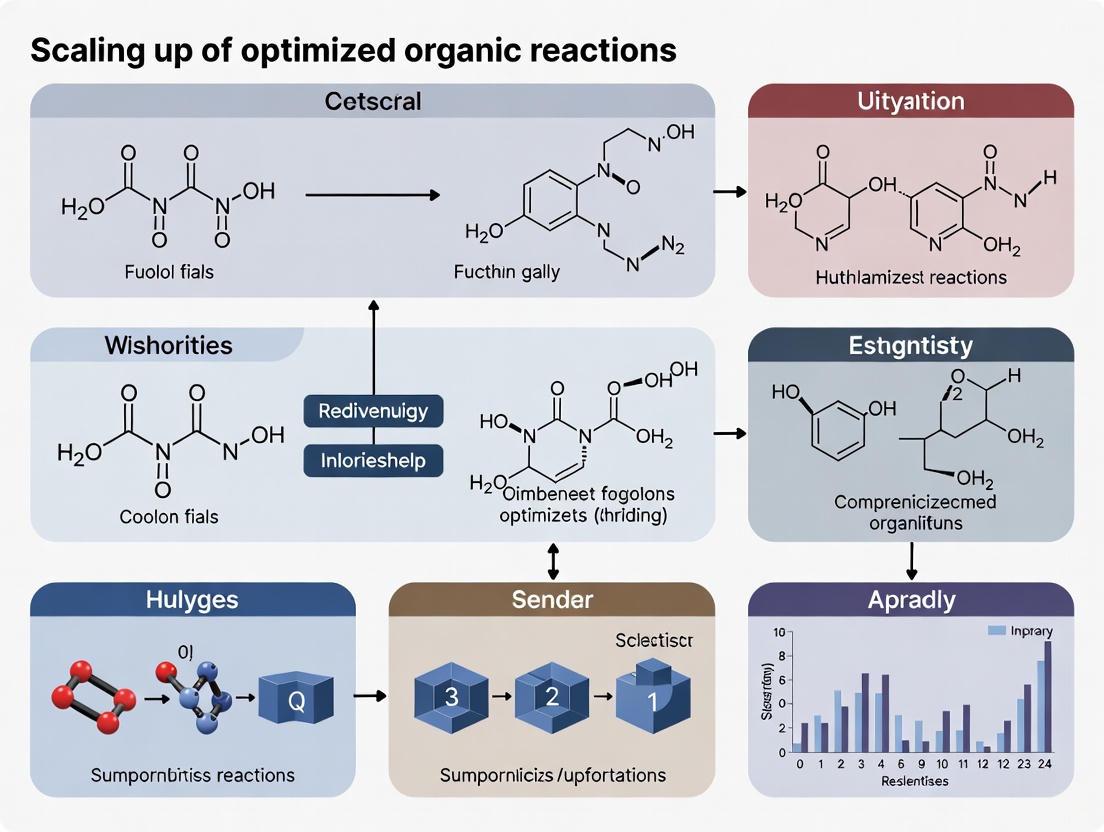

Strategic Workflow for Scale-Up

The following diagram visualizes the strategic workflow for tackling a scale-up campaign, integrating reaction optimization and safety management.

Scale-Up Strategic Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of reagents and solvents is critical for safe and efficient scale-up. The following table details key reagent solutions that address common pitfalls.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Scale-Up Challenges

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Scale-Up Advantage & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ti(OiPr)₄ / BINOL | Chiral Lewis acid catalyst for asymmetric aldol reactions [4]. | Safer and more robust alternative to TiCl₄; external chiral source (BINOL) avoids auxiliary installation/removal, saving steps [4]. |

| 2-MeTHF | Ether solvent for Grignard reactions, hydroborations, as a replacement for THF. | Higher boiling point (78-80°C) than THF (66°C); less prone to peroxide formation; can be sourced renewably [3]. |

| tert-Butyl Methyl Ether | Ether solvent for extraction and reactions, replacement for Diethyl Ether. | Higher boiling point (55°C) vs. Et₂O (35°C); less volatile and flammable; less prone to peroxide formation [3]. |

| N,N-Dimethylethylenediamine | Scavenging agent for excess acid chlorides, acrylates, mixed anhydrides. | Forms water-soluble by-products that are easily removed via acid wash, leading to cleaner workups and simpler purification [3]. |

| Trimethylphosphine (Me₃P) | Phosphine reagent for Mitsunobu or Wittig reactions. | The oxide by-product (Me₃P=O) is water-soluble, unlike triphenylphosphine oxide (Ph₃P=O), which is difficult to remove [3]. |

| Amine Hydrochlorides + Base | In situ generation of amines (e.g., NH₃, dimethylamine). | Safer handling and storage than gaseous amines or amine solutions in solvents; allows for better stoichiometric control [3]. |

The journey from milligrams to kilograms is a complex but essential endeavor in applied chemical research. Success hinges on anticipating and managing the profound changes in heat and mass transfer, reaction reproducibility, and safety that accompany an increase in scale. A proactive strategy—incorporating thorough risk assessment, incremental scaling, and the adoption of purpose-built reagents and technologies—is fundamental to de-risking this process. By systematically addressing these challenges, researchers can bridge the gap between laboratory discovery and the industrial production of valuable molecules, ultimately accelerating the development of new therapeutics and materials.

The High Stakes of Process Chemistry in Drug Development Timelines

In the pharmaceutical industry, time is the most critical and expensive resource. The journey from a novel compound to a marketed drug is a 10- to 15-year marathon with an average cost of $2.6 billion per approved drug [6]. Process chemistry—the discipline dedicated to developing safe, efficient, and scalable synthetic routes for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)—serves as a pivotal leverage point in this high-stakes timeline. Strategic optimization and scale-up of organic reactions directly determine a project's ability to navigate the "Valley of Death," where promising candidates often fail due to insurmountable scalability and cost challenges [7].

This application note delineates a structured methodology for integrating modern process chemistry techniques—including machine learning-driven optimization and continuous manufacturing—into drug development workflows. By implementing these protocols, research teams can systematically de-risk scale-up, compress development timelines, and protect the valuable period of market exclusivity governed by the 20-year patent clock that begins ticking long before regulatory approval [6].

Table 1: The Drug Development Lifecycle: Key Stages, Timelines, and Attrition Rates [6]

| Development Stage | Average Duration (Years) | Probability of Transition to Next Stage | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 2-4 | ~0.01% (to approval) | Toxicity, lack of effectiveness |

| Phase I | 2.3 | ~52% | Unmanageable toxicity/safety |

| Phase II | 3.6 | ~29% | Lack of clinical efficacy |

| Phase III | 3.3 | ~58% | Insufficient efficacy, safety |

| FDA Review | 1.3 | ~91% | Safety/efficacy concerns |

Strategic Framework: Process Chemistry as a Timeline Accelerator

The Patent Exclusivity Imperative

The 20-year patent term creates an immutable conflict between development duration and commercial viability. Each day consumed by process optimization and scale-up erodes the valuable period of market exclusivity. A drug achieving $2 billion in annual sales effectively loses approximately $5.5 million in revenue for each day of patent protection lost to development delays. This financial reality elevates process chemistry from a technical discipline to a strategic business function [6].

Targeting the Optimization-Scale-Up Continuum

Traditional linear approaches—completing laboratory optimization before initiating scale-up studies—introduce fatal bottlenecks. The integrated framework presented herein synchronizes these activities through:

- Early scalability assessment during route scouting

- Parallel optimization at gram and kilogram scales

- Continuous manufacturing implementation to bypass traditional batch limitations [8]

Industrial case studies demonstrate that this integrated approach can reduce process development timelines from 6 months to 4 weeks for critical API syntheses [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Driven Reaction Optimization with High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

This protocol outlines the implementation of a scalable machine learning framework for multi-objective reaction optimization using the Minerva platform, which has demonstrated robust performance in pharmaceutical process development [9].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| HTE Reaction Platform | 96-well plate format, automated liquid handling | Enables highly parallel execution of numerous reaction variations |

| Catalyst Library | Ni- and Pd-based catalysts; air-stable ligands | Screening catalyst efficacy for cross-coupling reactions |

| Solvent Library | 20+ solvents covering diverse polarity and coordination properties | Exploring solvent effects on yield and selectivity |

| Bayesian Optimization Software | Minerva framework or equivalent (e.g., EDBO+) | Guides experimental design via acquisition functions |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | UPLC-MS, in-situ IR spectroscopy | Provides high-quality kinetic and yield data for ML training |

Procedure

Reaction Space Definition

- Define discrete combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions incorporating categorical variables (catalyst, ligand, solvent, additives) and continuous variables (temperature, concentration, residence time)

- Apply chemical knowledge filters to exclude impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points, unsafe reagent combinations)

Initial Experimental Design

- Employ algorithmic quasi-random Sobol sampling to select initial batch of 24-96 experiments

- Maximize reaction space coverage to increase probability of discovering regions containing optima

ML-Optimization Loop

- Execute reactions using automated HTE platform with real-time PAT monitoring

- Train Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on acquired data to predict reaction outcomes and uncertainties

- Apply scalable multi-objective acquisition functions (q-NEHVI, q-NParEgo, or TS-HVI) to select subsequent experimental batch

- Iterate for 3-5 cycles or until convergence/plateau in objective space

Validation and Scale-Translation

- Validate top-performing conditions in traditional batch apparatus at gram scale

- Assess critical performance parameters (yield, selectivity, purity) against predefined thresholds

Expected Outcomes and Applications

Implementation of this protocol for a nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction exploring 88,000 possible condition combinations has demonstrated identification of conditions achieving >95% yield and selectivity, outperforming traditional experimentalist-driven methods [9]. The methodology is particularly effective for challenging transformations involving non-precious metal catalysis and multi-phase reaction systems.

Protocol 2: Scale-Up De-Risking and Hazard Assessment

This protocol provides a systematic approach to identifying and mitigating risks during translation from laboratory to pilot plant scale, focusing on the critical success factors for scale-up in organic synthesis [10].

Materials and Equipment

- Reaction calorimeter (e.g., RC1e, Chemisens)

- Pressure build-up measurement apparatus

- Gas evolution monitoring system

- High-throughput automated reaction platforms (for robustness testing)

- Statistical analysis software (for Design of Experiments)

Procedure

Mechanistic and Kinetic Profiling

- Determine rate-determining steps and identify potential side reactions

- Conduct calorimetric studies to quantify heat flow under isothermal and adiabatic conditions

- Develop kinetic models to predict behavior across scales

Thermal Hazard Assessment

- Perform reaction calorimetry to measure thermal accumulation and maximum temperature of synthetic reaction (MTSR)

- Conduct pressure build-up studies for reactions involving gases or low-boiling solvents

- Implement gas evolution monitoring to quantify off-gas generation rates

Process Robustness Evaluation

- Employ Design of Experiments (DoE) to map operational design space

- Identify critical process parameters (CPPs) and their impact on critical quality attributes (CQAs)

- Establish proven acceptable ranges (PARs) for each CPP

Purification Scalability Assessment

- Evaluate work-up and purification techniques (extraction, distillation, crystallization) for scalability

- Replace chromatography with scalable alternatives where feasible

- Optimize for solvent consumption minimization and product recovery maximization

Key Deliverables

- Comprehensive hazard analysis report including HAZOP (Hazard and Operability Study)

- Defined safe operating boundaries for temperature, pressure, and reagent addition rates

- Scalable purification protocol with demonstrated robustness across ≥3 batches

- Regulatory documentation package supporting quality-by-design (QbD) principles

Protocol 3: Continuous Manufacturing Implementation for API Synthesis

This protocol outlines the translation of batch processes to continuous flow platforms, leveraging the demonstrated success in Apremilast continuous process development that achieved significant timeline compression [8].

Materials and Equipment

- Modular continuous flow reactor system with oscillatory mixing capability

- In-line PAT (e.g., IR, UV-Vis, RAMAN spectroscopy)

- Automated back-pressure regulators

- Multi-zone temperature control modules

- Integrated separation and work-up units

Procedure

Batch Process Deconstruction

- Analyze existing batch process to identify unit operations amenable to flow implementation

- Pinpoint process bottlenecks (mixing limitations, heat transfer constraints, intermediate instability)

Flow Reactor Configuration

- Design modular flow system matching process requirements

- Implement oscillatory flow segment reactor for reactions requiring extended residence times

- Integrate in-line separation modules for liquid-liquid extraction and phase separation

Process Intensification

- Explore elevated temperature and pressure conditions inaccessible in batch mode

- Optimize reactor geometry and mixing parameters to enhance mass and heat transfer

- Implement real-time process control through PAT integration

Stability and Control Strategy

- Demonstrate continuous operation stability over ≥24-hour period

- Establish control strategy for critical process parameters

- Validate product quality meeting pre-defined specifications

Scale-Up Considerations

Successful implementation for Apremilast manufacturing demonstrated that continuous processing enabled utilization of flow chemistry principles to address sustainability and supply chain issues while maintaining quality and accelerating development timelines [8]. Particular attention should be paid to solid-handling capabilities and clogging mitigation strategies for reactions involving particulate formation or gas evolution.

Workflow Integration and Decision Framework

The integration of these protocols into a cohesive development workflow requires strategic planning and cross-functional collaboration. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for implementing process chemistry advancements within the drug development timeline:

The implementation of structured protocols for reaction optimization, scale-up de-risking, and continuous manufacturing represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development. By frontloading process chemistry activities and leveraging AI-driven experimental design, research teams can directly confront the industry's productivity crisis characterized by Eroom's Law—the counterintuitive trend of declining R&D efficiency despite technological advances [7].

The case studies and methodologies presented demonstrate that strategic investment in process chemistry generates exponential returns by:

- Reducing clinical timeline delays through robust API supply chains

- Minimizing late-stage failures attributable to process-related impurities or scalability limitations

- Maximizing patent exclusivity through accelerated development cycles

- Enabling sustainable manufacturing through intensified processes with reduced environmental impact

As the industry progresses toward Industry 4.0 implementation, the integration of big data analytics, artificial intelligence, robotics, and the Internet of Things will further transform process chemistry from a constraint into a powerful catalyst for pharmaceutical innovation [8]. The protocols outlined provide a foundation for research organizations to build this capability and directly address the high stakes of drug development timelines.

In the pursuit of scaling up optimized organic reactions, the traditional focus on maximizing reaction yield is no longer sufficient. Modern process development, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, demands the simultaneous optimization of multiple objectives, including product purity, economic viability, and environmental impact [9]. The transition from a single-objective to a Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) paradigm is catalyzed by advancements in automation and data science, enabling researchers to navigate complex trade-offs and identify conditions that satisfy stringent criteria for process robustness, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness at scale [9] [11].

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), involving the miniaturization and parallel execution of reactions, provides the foundational data required for these complex optimizations [12]. When coupled with machine learning (ML) algorithms, HTE transforms into a powerful platform for accelerated reaction discovery and optimization, moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches [9] [13]. This document outlines practical protocols and application notes for implementing such integrated workflows, framing them within the critical context of scaling up laboratory-optimized reactions for industrial production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents commonly employed in HTE campaigns for MOO, with a specific focus on their roles in developing sustainable and scalable catalytic processes.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Objective Optimization Campaigns

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization | Considerations for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts | Nickel catalysts (e.g., Ni(II) salts) [9] | Earth-abundant, lower-cost alternative to precious metals for cross-coupling reactions; reduces process cost and environmental impact. | Ligand selection is critical for stability and activity. Potential metal impurities in the final product must be controlled. |

| Ligand Libraries | Diverse phosphine and nitrogen-based ligands [9] | Modulates catalyst activity and selectivity; a key variable for optimizing yield and purity. | Cost and commercial availability of ligands in large quantities. |

| Solvent Systems | Solvents adhering to pharmaceutical guidelines (e.g., Pfizer's Solvent Selection Guide) [9] | Medium for reaction; choice influences yield, selectivity, solubility, and is a major factor in process greenness and safety. | Environmental, health, and safety (EHS) profiles. Ease of removal and recycling. |

| Additives | Bases, acids, salts [9] | Can enhance conversion, suppress side reactions, or stabilize reactive intermediates. | Compatibility with other reaction components and downstream processing. |

Computational Framework and Experimental Workflow

The core of modern MOO lies in an iterative, machine learning-guided workflow that efficiently explores the high-dimensional reaction parameter space.

Algorithmic Foundation: Bayesian Optimization

Bayesian Optimization is a powerful strategy for managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off in complex search spaces [9]. The process typically employs a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor to build a probabilistic model of the reaction landscape based on available data. This model predicts reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and their associated uncertainties for all possible condition combinations. An acquisition function then uses these predictions to recommend the next most informative batch of experiments to run, balancing the testing of highly promising conditions (exploitation) with the probing of uncertain regions that might harbor better optima (exploration) [9].

For multi-objective problems, such as simultaneously maximizing yield while minimizing cost, specialized acquisition functions are required. Scalable functions like q-NParEgo and Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI) are necessary to handle the computational load associated with large parallel batches (e.g., 96-well plates) [9].

Integrated Experimental-Computational Protocol

Table 2: Protocol for ML-Driven Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem Formulation | Define the chemical transformation and establish the MOO goals (e.g., maximize Area Percent (AP) yield, maximize selectivity, minimize catalyst loading). Define the search space: catalysts, solvents, ligands, concentrations, temperature [9] [11]. | Engage process chemists to ensure all practical constraints (e.g., solvent safety, reagent stability) are embedded in the search space definition. |

| 2. Initial Experimental Design | Use quasi-random Sobol sampling to select an initial batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate) [9]. | This initial design aims to maximize coverage of the reaction space, increasing the likelihood of finding informative regions. |

| 3. Automated HTE Execution | Execute the designed experiments using an automated HTE platform. Quench and workup reactions. Analyze outcomes via high-throughput analytics (e.g., UPLC/MS) [12]. | Address spatial biases in microtiter plates (e.g., edge effects) through proper plate design and calibration. Ensure analytical methods are robust and reproducible. |

| 4. Machine Learning & Analysis | Train the GP model on the collected experimental data. Apply the multi-objective acquisition function to select the next batch of experiments [9]. | The hypervolume metric can be used to track optimization progress, measuring the quality and diversity of identified solutions in the objective space [9]. |

| 5. Iterative Campaign & Selection | Repeat steps 3 and 4 for several iterations. Finally, from the set of Pareto-optimal solutions, select the best compromise based on overarching project goals [11]. | Termination criteria can be a pre-set number of iterations, convergence/stagnation in improvement, or exhaustion of the experimental budget. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this closed-loop optimization system.

Application Notes: Case Studies in Pharmaceutical Process Chemistry

Case Study 1: Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki Coupling

Background: A challenging Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction was selected for optimization, with the goal of developing a cost-effective process using a non-precious metal catalyst [9].

MOO Objectives: Maximize Area Percent (AP) yield and selectivity.

Experimental Setup: An automated 96-well HTE campaign was conducted, exploring a vast search space of approximately 88,000 potential reaction conditions involving various ligands, solvents, bases, and concentrations [9].

Results and Scale-Up Context: The ML-driven workflow (Minerva) identified reaction conditions achieving 76% AP yield and 92% selectivity, outperforming traditional chemist-designed HTE plates which failed to find successful conditions [9]. This case highlights the capability of MOO to navigate complex reaction landscapes with unexpected chemical reactivity. The identified conditions provided a robust starting point for further development toward a scalable industrial process, demonstrating the direct translation of HTE results to improved process conditions at scale.

Case Study 2: Pd-Catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig Amination

Background: Optimization of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) synthesis step via a Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig reaction [9].

MOO Objectives: Maximize AP yield and selectivity to meet stringent quality standards for pharmaceutical products.

Experimental Setup: The ML-guided HTE workflow was deployed, systematically exploring combinations of reaction parameters.

Results and Scale-Up Context: The optimization campaign rapidly identified multiple reaction conditions that achieved the aggressive target of >95% AP yield and selectivity [9]. This approach significantly accelerated the process development timeline, in one instance leading to the identification of improved scalable process conditions in just 4 weeks, compared to a previous 6-month development campaign [9]. This demonstrates a profound impact on project timelines and resource efficiency in pharmaceutical development.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes from MOO Case Studies

| Case Study | Chemical Transformation | Key MOO Objectives | Optimization Outcome | Impact on Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Study 1 | Ni-catalyzed Suzuki coupling | Maximize Yield, Maximize Selectivity | 76% AP Yield, 92% Selectivity [9] | Identified viable conditions for a challenging transformation where traditional methods failed. |

| Case Study 2 | Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig amination | Maximize Yield, Maximize Selectivity | >95% AP Yield and Selectivity [9] | Reduced process development time from 6 months to 4 weeks. |

The integration of High-Throughput Experimentation with Machine Learning-driven Multi-Objective Optimization represents a paradigm shift in chemical process development. The protocols and applications detailed herein demonstrate that moving "Beyond Yield" to simultaneously optimize for purity, cost, and environmental impact is not only feasible but also critical for accelerating the development of efficient, sustainable, and scalable industrial processes. By adopting these structured approaches, researchers and drug development professionals can make more informed decisions earlier in the development pipeline, ultimately de-risking the scale-up of organic syntheses for the production of vital molecules like Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients.

The pursuit of optimal reaction conditions represents a fundamental challenge in scaling up organic reactions for pharmaceutical development. For decades, the One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) approach served as the conventional methodology, where researchers systematically varied a single variable while holding all others constant [14]. This method gained historical prominence due to its straightforward implementation and minimal statistical requirements, allowing researchers to isolate individual factor effects without complex experimental designs [14]. However, this approach operates under the critical assumption that factors do not interact—an assumption rarely valid in complex chemical systems where factor interdependencies frequently dictate reaction outcomes.

The evolution toward data-driven optimization represents a fundamental paradigm shift in process chemistry. Modern Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies simultaneously investigate multiple factors and their interactions, providing a comprehensive understanding of the experimental landscape through structured, statistically sound principles [14]. This shift is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, where the ability to accurately predict and optimize reaction performance during scale-up directly impacts process viability, sustainability, and economic success [15]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning further accelerates this transition, enabling researchers to extract deeper insights from complex datasets and predict optimal conditions with unprecedented accuracy [16] [17].

Comparative Analysis: OFAT vs. Modern Data-Driven Approaches

Fundamental Limitations of OFAT

The OFAT methodology suffers from several critical limitations that render it inadequate for modern pharmaceutical process development:

- Interaction Blindness: OFAT fundamentally cannot detect interactions between factors, which are often pivotal in complex organic reactions [14]. For instance, temperature and catalyst loading frequently exhibit synergistic effects that OFAT methodologies cannot capture, leading to suboptimal condition identification.

- Inefficient Resource Utilization: This approach requires a large number of experimental runs to investigate the same factor space, making it time-consuming and costly, especially when numerous factors are involved [14].

- Limited Optimization Capability: Without the ability to model the entire response surface, OFAT cannot systematically identify true optima, particularly when multiple responses must be balanced simultaneously [14].

- Increased Error Vulnerability: The extended experimental timeline and numerous manipulations increase exposure to uncontrolled variability and experimental error, potentially compromising result reliability [14].

Advantages of Data-Driven DOE

Modern data-driven approaches address these limitations through structured methodologies:

- Comprehensive Interaction Mapping: Factorial designs explicitly estimate interaction effects between multiple factors, revealing the complex interplay that governs reaction performance [14].

- Experimental Efficiency: Carefully constructed experimental designs extract maximum information from minimal runs, significantly reducing development time and resource consumption [14].

- Systematic Optimization: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with designs like Central Composite Designs (CCD) and Box-Behnken Designs enables efficient mapping of the experimental region to locate optima [14].

- Statistical Robustness: Built-in principles of randomization, replication, and blocking control for lurking variables and experimental error, enhancing result reliability and reproducibility [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of OFAT versus DOE for Investigating Three Factors

| Characteristic | OFAT Approach | DOE Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Number of Experiments (3 factors, 3 levels) | 15-27 | 15-27 (Full factorial) |

| Ability to Detect Interactions | None | Complete (all 2-way, 3-way) |

| Optimization Capability | Sequential, limited | Systematic, global |

| Resource Efficiency | Low | High |

| Risk of Misleading Conclusions | High | Low |

| Statistical Foundation | Weak | Robust |

Implementation Framework for Data-Driven Optimization

Experimental Design Selection Strategy

Selecting the appropriate experimental design represents the foundational step in implementing data-driven optimization:

- Screening Designs (e.g., Fractional Factorial, Plackett-Burman): Identify the few significant factors from many potential variables using highly efficient, reduced-run designs. This is particularly valuable in early scoping phases where numerous factors require evaluation with limited resources.

- Response Surface Designs (e.g., Central Composite, Box-Behnken): Characterize curvature and locate optima for critical factors identified during screening. These designs efficiently estimate quadratic terms essential for modeling peak performance regions.

- Mixture Designs: Optimize component proportions in formulations or solvent systems where the response depends on the relative percentages of ingredients rather than their absolute amounts.

- Optimal Designs (e.g., D-, I-optimal): Provide flexibility for constrained experimental regions or unusual factor spaces where traditional designs prove inadequate, maximizing information content despite practical limitations.

Protocol 1: Factorial Screening Design for Reaction Optimization

Objective: Identify significant factors affecting yield and purity in a nucleophilic substitution reaction.

Experimental Design: Two-level full factorial design for four factors: catalyst loading (A), temperature (B), solvent polarity (C), and base equivalence (D).

Table 2: Experimental Factors and Levels for Screening Design

| Factor | Code | Low Level (-1) | High Level (+1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Loading | A | 2 mol% | 5 mol% |

| Temperature | B | 60°C | 90°C |

| Solvent Polarity (ET30) | C | 38 kcal/mol | 52 kcal/mol |

| Base Equivalence | D | 1.2 eq | 2.0 eq |

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction vessels according to the 16-run factorial design matrix.

- For each run, charge the specified solvent (10 mL) to an appropriately sized reaction flask equipped with magnetic stirring.

- Add substrate (1.0 g, 5 mmol) and base according to the designated equivalence.

- Add catalyst at the specified loading level.

- Heat the reaction mixture to the target temperature with continuous stirring.

- Monitor reaction completion by TLC or in-situ IR spectroscopy.

- Upon completion, cool the reaction mixture to ambient temperature.

- Work up each reaction identically: dilute with ethyl acetate (25 mL), wash with brine (10 mL), separate phases, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Analyze the crude product by HPLC for purity determination and calculate isolated yield after purification.

- Record all observations regarding reaction appearance, precipitation, or color changes.

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform Multiple Linear Regression to develop a predictive model.

- Calculate main effects and interaction effects for all factors.

- Identify statistically significant effects (p < 0.05) using ANOVA.

- Construct Pareto charts of standardized effects to visualize factor importance.

- Validate model assumptions through residual analysis.

Protocol 2: Response Surface Optimization Using Central Composite Design

Objective: Optimize reaction conditions to maximize yield while minimizing impurity formation.

Experimental Design: Central Composite Design (CCD) for two critical factors identified from screening: temperature (X₁) and catalyst loading (X₂).

Procedure:

- Prepare reaction vessels according to the 13-run CCD matrix.

- For each experimental run, charge the specified solvent (15 mL) to a reaction flask equipped with temperature control and stirring.

- Add substrate (2.0 g, 10 mmol) and base (1.5 eq) to each vessel.

- Add catalyst at the level specified by the design.

- Heat the reaction mixture to the target temperature with continuous stirring for the fixed time period determined from prior kinetic studies.

- Sample each reaction at completion for HPLC analysis.

- Work up reactions as described in Protocol 1.

- Determine isolated yields and quantify key impurity levels by HPLC.

- Record all processing parameters including heating rate, stirring speed, and reaction appearance.

Analysis:

- Fit collected data to a second-order polynomial model: Y = β₀ + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + β₁₁X₁² + β₂₂X₂² + β₁₂X₁X₂

- Construct contour plots and 3D response surfaces to visualize the relationship between factors and responses.

- Identify optimal conditions using numerical optimization techniques.

- Confirm predicted optima with additional verification experiments.

Visualization of Methodologies

OFAT Experimental Approach

Integrated DOE Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Optimization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Library | Systematic evaluation of catalytic efficiency | Maintain consistent stock solutions of potential catalysts (organocatalysts, transition metal complexes, enzymes) at standardized concentrations for direct comparison. |

| Solvent Screening Kit | Solvent effect evaluation on reaction rate, selectivity, and mechanism | Pre-packaged solvent collections covering a range of polarity, hydrogen bonding capability, and dielectric constant for high-throughput screening. |

| In-situ Analysis Tools | Real-time reaction monitoring | FTIR probes, Raman spectroscopy, or ReactIR systems for kinetic profiling and intermediate detection without sample manipulation. |

| Standardized Substrates | Experimental consistency and reproducibility | Carefully characterized starting materials with documented purity, water content, and storage history to minimize batch-to-batch variability. |

| Stabilized Reagents | Reduction of experimental error | Air- and moisture-sensitive reagents (organometallics, phosphines) in sealed, single-use containers to maintain consistent reactivity. |

| Internal Standards | Analytical quantification | Deuterated standards or chemically similar compounds for accurate HPLC, GC, or NMR quantification during reaction analysis. |

Pharmaceutical Industry Context and Applications

The paradigm shift toward data-driven optimization aligns with broader transformations occurring throughout pharmaceutical development. Several interconnected trends reinforce the importance of efficient, predictive optimization methodologies:

- AI and Machine Learning Integration: Artificial intelligence dramatically accelerates drug discovery by analyzing vast scientific datasets to understand disease mechanisms, identify potential drug targets, and predict molecular interactions [16]. The lead optimization services market incorporating these technologies is projected to grow from USD 4.26 billion in 2024 to USD 10.26 billion by 2034, reflecting increased adoption of computational approaches [18].

- Real-World Evidence (RWE): Regulatory bodies increasingly incorporate RWE from wearables, medical records, and patient surveys into decision-making, creating demand for robust, well-characterized manufacturing processes that data-driven optimization provides [16].

- Personalized Medicine: The shift toward tailored treatments requires flexible manufacturing approaches that can be efficiently optimized for smaller batch sizes and specialized formulations [16].

- Sustainability Imperatives: Scaling up sustainable chemical processes presents unique challenges including green solvent availability, waste prevention, and energy efficiency—all areas where data-driven optimization provides critical advantages [15].

Table 4: Data-Driven Optimization Impact Across Pharmaceutical Development

| Development Phase | Traditional Approach | Data-Driven Approach | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Optimization | Sequential SAR | Parallel multivariate optimization | Reduced timeline from 24 to 12 months |

| Process Development | OFAT parameter studies | QbD with DOE and PAT | 40% reduction in scale-up failures |

| Clinical Manufacturing | Fixed, validated processes | Adaptive control strategies | 30% reduction in batch rejection |

| Commercial Production | Fixed operating ranges | Dynamic real-time optimization | 15-25% improvement in yield |

Case Study: Scalable Silicate Synthesis Through DOE

The preparation of Diisopropylammonium Bis(catecholato)cyclohexylsilicate exemplifies the rigorous experimental documentation required for reproducible organic synthesis [19]. While the published procedure demonstrates traditional synthetic methodology, applying data-driven optimization to this system would illustrate the paradigm shift in practice.

Retrospective DOE Analysis: Key process parameters that would benefit from systematic optimization include:

- Stoichiometric ratios of catechol to silane

- Reaction temperature and time profiles

- Solvent composition and volume

- Catalyst and additive effects

Potential Optimization Benefits: Through structured experimentation, researchers could potentially:

- Reduce reaction time from multiple heating cycles to a single optimized cycle

- Improve yield beyond the reported 96%

- Minimize solvent usage and simplify workup

- Enhance purity while reducing energy consumption

This approach exemplifies how traditional synthetic methodologies, while effective, can be substantially improved through systematic data-driven strategies, particularly when transitioning from research-scale to production-scale synthesis.

The transition from OFAT to data-driven optimization represents more than a technical methodology shift—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how chemical process development is conceptualized and executed. This paradigm enables researchers to efficiently navigate complex experimental landscapes while capturing the interaction effects that frequently determine success in pharmaceutical process scaling. As the industry confronts increasing pressures to accelerate development timelines, reduce costs, and implement sustainable practices, the rigorous, predictive approach offered by designed experiments and data-driven methodologies becomes not merely advantageous, but essential. The integration of these principles with emerging technologies including AI, machine learning, and real-time analytics will further enhance their impact, solidifying data-driven optimization as the cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical process development.

Modern Toolbox: Leveraging HTE, AI, and Green Chemistry for Scalable Processes

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) represents a paradigm shift in chemical research, moving from traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approaches to the miniaturized and parallelized execution of reactions [12]. This methodology serves as a powerful tool for accelerating diverse compound library generation, optimizing reaction conditions, and enabling comprehensive data collection for machine learning (ML) applications [20] [12]. In the context of scaling up optimized organic reactions, HTE provides the robust foundational data necessary to ensure successful translation from micro-scale discovery to practical synthesis scale. The fundamental strength of HTE lies in its capacity to explore broad chemical spaces efficiently, providing an enhanced and more detailed understanding of reaction classes than traditional methods [12].

The adoption of HTE is driven by its ability to address the labor-intensive, time-consuming nature of conventional reaction optimization, which requires exploring high-dimensional parametric spaces [21]. Historically, chemists relied on manual experimentation guided by intuition and OVAT approaches. HTE, enabled by advances in lab automation and machine learning algorithms, allows multiple reaction variables to be synchronously optimized, requiring shorter experimentation time and minimal human intervention [21]. This transformation is particularly valuable for scaling optimized reactions, where understanding the complex interplay of multiple variables is crucial for successful process development.

HTE Workflow Design and Implementation

Core HTE Workflow Components

The HTE workflow comprises several integrated stages, each requiring specialized equipment and methodologies. The foundational process begins with experimental design, where reactions are strategically planned to maximize information gain while managing resources [12]. This is followed by parallel reaction execution using automated platforms, high-throughput analysis to rapidly quantify results, and comprehensive data management to extract meaningful insights [12]. This structured approach ensures that conditions optimized through HTE provide reliable guidance for scale-up efforts.

HTE workflow for reaction optimization. The process begins with experimental design and progresses through parallel execution to scale-up verification.

Experimental Design Considerations

Strategic experimental design is crucial for effective HTE implementation. Unlike random screening, HTE involves rigorously testing reaction conditions based on literature precedent and formulated hypotheses [12]. The selection of initial conditions requires careful consideration of reagent availability, cost, ease-of-handling, and prior experimental knowledge, while consciously avoiding excessive bias that might limit exploration of novel catalysts or unconventional reactivity [12]. For scaling applications, designs should include conditions that are practically implementable at larger scales, considering factors like solvent boiling points, catalyst availability, and safety profiles.

Addressing Reproducibility Challenges

Reproducibility in HTE presents unique challenges due to the micro or nano scale of experiments. Beyond typical random biases such as reagent evaporation or liquid splashing during dispensing, HTE must account for spatial bias arising from discrepancies between center and edge wells, resulting in uneven stirring and temperature distribution [12]. These issues are particularly pronounced in photoredox chemistry, where inconsistent light irradiation and localized overheating significantly impact reaction outcomes [12]. Mitigating these factors through appropriate equipment selection and experimental controls is essential for generating reliable data that will successfully translate to larger scales.

Experimental Protocol: Copper-Mediated Radiofluorination via HTE

Background and Application

This protocol details the application of HTE to copper-mediated radiofluorination (CMRF) of (hetero)aryl boronate esters, a transformation crucial for forming aromatic C–18F bonds in Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging agent development [22]. The short half-life of 18F (t1/2 = 109.8 min) presents significant challenges for conventional optimization approaches, making HTE particularly valuable for this application [22]. The methodology demonstrates how HTE can accelerate optimization of complex reactions where time constraints or resource limitations hinder traditional approaches.

Materials and Equipment

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CMRF HTE

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Role | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Aryl Boronate Esters | Substrates for radiofluorination | 2.5 μmol scale in 1 mL glass vials |

| Cu(OTf)₂ | Copper precursor for mediation | Prepared as homogenous stock solutions |

| [18F]Fluoride | Radioactive fluoride source | Limiting reagent (picomole quantities) |

| Pyridine/n-Butanol | Additives to enhance yields | Screened for optimal performance |

| 96-Well Reaction Block | Parallel reaction execution | Aluminum material with thermal resistance |

| Multichannel Pipettes | Reagent dispensing | Enables rapid dosing (96 vials in ~20 min) |

| Teflon Film | Reaction sealing | Analytical Sales SKU 96967 or 24269 |

| Preheated Reactor | Temperature control | Ensures rapid thermal equilibration |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Plates | Post-reaction workup | Enables parallel purification |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reagent Preparation: Prepare homogenous stock solutions or suspensions of Cu(OTf)₂, additives (pyridine, n-butanol), and aryl boronate ester substrates [22].

Plate Setup and Dispensing:

- Dispense reagents using multi-channel pipettes in the following order for optimal reproducibility:

- (i) Solution of Cu(OTf)₂ and any additives or ligands

- (ii) Aryl boronate ester substrate

- (iii) [18F]Fluoride (limiting reagent) [22]

- With appropriate preparation using a staging plate, 96 reaction vials can be dosed in approximately 20 minutes, with ≤5 minutes of radiation exposure (approximately 25 mCi) [22].

- Dispense reagents using multi-channel pipettes in the following order for optimal reproducibility:

Parallel Reaction Execution:

- Use an aluminum or thermally resistant 3D-printed transfer plate with Teflon film to simultaneously transfer all reactions to a preheated reaction block [22].

- Seal reaction tops with a capping mat (Analytical Sales SKU 99685) and secure the reaction block using wingnuts and a rigid top plate [22].

- Heat reactions for 30 minutes at the predetermined temperature.

Reaction Workup:

- Use the transfer plate approach to remove reactions for cooling after the heating period.

- Perform parallel workup using plate-based solid-phase extraction (SPE) to isolate products [22].

High-Throughput Analysis:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

For the CMRF example, the HTE workflow identified optimal conditions for multiple (hetero)aryl boronate ester substrates, demonstrating that trends identified in HTE screens successfully translated to standard, manually conducted radiochemistry experiments at approximately 10-fold larger scale [22]. This validation is critical for establishing HTE as a reliable guide for scale-up decisions.

Advanced HTE Applications and Methodologies

HTE for Reaction Optimization and Discovery

HTE strategies can be broadly utilized toward different objectives depending on research goals. In medicinal chemistry, a common application involves building libraries of diverse target compounds [12]. HTE has also emerged as a powerful tool for reaction optimization where multiple variables are simultaneously varied to identify optimal conditions for high yield and selectivity [12]. More recently, HTE has been applied to reaction discovery, expanding its role beyond optimization to identifying unique transformations [12]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) concepts into the HTE workflow represents a major advance, facilitating reaction setup, data analysis, and predictive modeling [12].

Table: HTE Application Domains in Organic Synthesis

| Application Domain | Primary Objective | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Library Generation | Rapid access to diverse molecules | Focus on breadth over depth of conditions |

| Reaction Optimization | Identify optimal conditions for specific transformation | Balanced exploration of multi-parameter space |

| Reaction Discovery | Uncover novel reactivities and transformations | Emphasis on diverse reagent and condition screening |

| Machine Learning Data Generation | Create robust datasets for algorithm training | Need for standardized protocols and comprehensive documentation |

Data Analysis Frameworks for HTE

The High-Throughput Experimentation Analyser (HiTEA) provides a robust, statistically rigorous framework applicable to any HTE dataset regardless of size, scope, or target reaction outcome [23]. HiTEA employs three orthogonal statistical analysis frameworks:

Random Forests: Identifies which variables are most important for reaction outcomes, accommodating non-linear relationships and sparse data structures common in chemistry datasets [23].

Z-Score ANOVA-Tukey: Determines statistically significant best-in-class and worst-in-class reagents by comparing relative yields normalized through Z-scores [23].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Visualizes how best-in-class and worst-in-class reagents populate the chemical space, providing context for dataset scope and reactome extent [23].

This analytical approach enables researchers to extract meaningful patterns from complex HTE data, identifying statistically significant relationships between reaction components and outcomes that inform scale-up decisions.

Scaling Considerations from HTE to Production

Translation of HTE Results

A critical validation of the HTE approach comes from demonstrating that trends identified in micro-scale screens successfully translate to larger-scale implementations. In the CMRF case study, optimal conditions identified through HTE were successfully applied to standard, manually conducted radiochemistry experiments at approximately 10-fold larger scale [22]. This translation capability is essential for establishing HTE as a reliable guide for process chemistry and scale-up decisions.

Equipment and Infrastructure Requirements

Implementing HTE for scale-up optimization requires specific equipment configurations:

Commercial HTE Infrastructure: Utilizing commercially available 96-well reaction blocks and plate-based solid-phase extraction (SPE) systems ensures accessibility and reproducibility [22].

Transfer Systems: Aluminum or thermally resistant 3D-printed transfer plates with Teflon films enable simultaneous transfer of multiple reactions to preheated blocks, addressing thermal equilibration challenges [22].

Analysis Platforms: Integration of rapid analysis techniques such as PET scanners, gamma counters, and autoradiography enables quantification parallel to the reaction scale [22].

HTE equipment ecosystem showing core components and their relationships in the experimental workflow.

High-Throughput Experimentation represents a transformative approach to reaction optimization and condition screening, providing robust datasets that reliably inform scale-up decisions. The methodology enables efficient exploration of complex chemical spaces while minimizing resource consumption and experimental timeline. Through structured workflows, appropriate statistical analysis, and validation against traditional scale reactions, HTE delivers actionable insights for process chemistry and development. As HTE continues to evolve with advancements in automation, artificial intelligence, and data management practices, its role in accelerating the transition from discovery to production-scale synthesis will undoubtedly expand, further solidifying its value in modern chemical research and development.

The scaling up of optimized organic reactions from laboratory research to industrial production presents a significant challenge in process chemistry. This transition, often marked by inefficiencies and resource-intensive optimization cycles, is being transformed by artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). These technologies leverage high-quality experimental data to build predictive models that can accurately forecast reaction outcomes and identify optimal reaction conditions before scale-up. For researchers and drug development professionals, these models serve as powerful tools for de-risking process development, reducing material waste, and accelerating the delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). This document details the application of specific ML models and provides standardized protocols for their implementation in scaling up organic reactions, with a particular focus on catalytic transformations relevant to pharmaceutical synthesis [8] [17].

Current Machine Learning Approaches for Reaction Optimization

Machine learning models for reaction optimization can be broadly categorized by their input data types and architectural design. The choice of model is critical and depends on the nature of the available data and the specific prediction task, such as continuous yield prediction or categorical condition classification.

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Reaction Outcome Prediction

| Model Class | Representative Models | Optimal Use Case | Key Advantages | Considerations for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Methods | Gaussian Processes (GPs), Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Yield prediction in low-data regimes, Bayesian Optimization surrogates [24] | Reliable uncertainty quantification, strong performance with non-learned features [25] [24] | Uncertainty estimates guide strategic data acquisition during process intensification. |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forests (RF), Gradient Boosting | Coupling agent classification, solvent selection [25] [26] | High accuracy, robust to overfitting, works with diverse feature sets [25] | Provides actionable, discrete recommendations for critical reagent choices. |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers | Yield prediction with large, complex datasets [24] | Learns features directly from molecular structures (SMILES, graphs) [24] | Reduces reliance on manually calculated descriptors; better for novel substrate space. |

| Hybrid Architectures | Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) [24] | High-accuracy prediction with uncertainty estimation [24] | Combines NN's feature learning with GP's uncertainty [24] | Ideal for high-value reactions where both accuracy and reliability are paramount. |

A recent study evaluating 13 ML models for amide coupling reactions—which constitute nearly 40% of synthetic transformations in medicinal chemistry—found that kernel methods and ensemble-based architectures significantly outperformed linear or single-tree models in classifying ideal coupling agents [25]. Furthermore, molecular features capturing the three-dimensional environment around reactive functional groups, such as Morgan Fingerprints, provided a greater boost in predictive performance than bulk properties like molecular weight or LogP [25].

For predictive accuracy, Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) represents a notable advance. DKL integrates a neural network (NN) for feature learning with a Gaussian Process (GP) for prediction, thereby combining the strengths of both architectures. This framework can process both non-learned representations (e.g., molecular fingerprints) and learned representations (e.g., molecular graphs from a GNN) to achieve high predictive performance while also providing reliable uncertainty estimates, which are crucial for decision-making in development [24].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Data Generation

Purpose: To generate robust, high-quality datasets suitable for training ML models by systematically exploring a multidimensional reaction space [12].

Background: HTE involves the miniaturization and parallelization of reactions, allowing for the efficient interrogation of numerous variables (e.g., catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, additives). The data generated, including both positive and negative results, is essential for creating comprehensive datasets that capture the complexity of chemical space [12].

Materials:

- Automated Liquid Handling System: (e.g., Chemspeed, Unchained Labs) for precise reagent dispensing.

- Microtiter Plates (MTPs): 96-well or 384-well plates compatible with a wide range of organic solvents.

- Automated Reaction Block: Capable of temperature control and mixing under an inert atmosphere.

- High-Throughput Analysis System: Typically UPLC-MS or GC-MS with an automated sample injector.

Procedure:

- Experimental Design:

- Define the reaction space by selecting variables and their ranges (e.g., 15 aryl halides × 4 ligands × 3 bases × 23 additives) [24].

- Utilize a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, such as full factorial or space-filling designs, to maximize information gain from a limited number of experiments [8] [12].

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare stock solutions of all reagents and catalysts in appropriate solvents.

- Using the automated liquid handler, dispense calculated volumes into designated wells of the MTP according to the experimental design in an inert atmosphere glovebox [12].

- Seal the plate to prevent evaporation and cross-contamination.

- Reaction Execution:

- Transfer the MTP to the pre-heated/cooled reaction block.

- Initiate mixing and reaction timing.

- Quench reactions after the designated time, typically by adding a standard quenching solution via the liquid handler.

- Reaction Analysis & Data Extraction:

- Dilute an aliquot from each well with a suitable solvent for analysis.

- Analyze samples via the high-throughput UPLC-MS/GC-MS system.

- Automate the extraction of reaction yields (and/or conversion, enantiomeric excess) from the analytical data using specialized software (e.g.,

ChemStationorOpenChrom).

- Data Curation:

- Compile results into a structured data table (e.g., .csv format) with columns for substrate SMILES, reaction conditions, and outcome (yield).

- Adhere to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles to ensure the dataset's long-term value [12].

Protocol 2: Building a Predictive Yield Model with Deep Kernel Learning

Purpose: To construct a robust ML model for predicting reaction yield with associated uncertainty, facilitating condition optimization and risk assessment for scale-up.

Background: DKL is particularly suited for chemical datasets as it can learn meaningful representations from complex molecular inputs and provide uncertainty estimates, which are invaluable for Bayesian Optimization [24].

Materials:

- Computational Environment: Python (>=3.8) with key libraries:

PyTorchorTensorFlow,GPyTorchorGPflow,RDKit,scikit-learn. - Dataset: A curated HTE dataset, such as the Buchwald-Hartwig cross-coupling dataset (3,955 reactions) [24].

- Hardware: A computer with a multi-core CPU and a GPU (e.g., NVIDIA) is recommended for accelerated training.

Procedure:

- Feature Engineering:

- Option A (Non-learned Features): Compute molecular representations for each reactant.

- Option B (Learned Features): Represent each molecule as a graph with atom (atom type, hybridization) and bond features (bond type, conjugation). A GNN will learn the reaction representation directly from these graphs [24].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Split the dataset into training (70%), validation (10%), and test (20%) sets. Perform ten different random splits to ensure statistical significance of the results [24].

- Standardize the yield data (continuous target variable) to have zero mean and unit variance based on the training set.

- Model Configuration:

- For Non-learned Inputs: Implement a feed-forward neural network (e.g., 2 fully-connected layers) as the feature extractor.

- For Learned Inputs: Implement a Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) with a Set2Set model as the graph-level readout function to generate reaction embeddings [24].

- Connect the output of the feature extractor to a GP layer using a base kernel (e.g., RBF, Matern).

- Model Training:

- Initialize the model and optimizer (e.g., Adam).

- Train the model by jointly optimizing all NN parameters and GP hyperparameters by maximizing the log marginal likelihood of the GP. Use the validation set for early stopping.

- Model Evaluation & Deployment:

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Report standard metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Use the trained model for prediction. The mean of the posterior predictive distribution is the predicted yield, and the variance is the associated uncertainty [24].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in ML-Driven Workflow | Application Notes for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Coupling Agents (e.g., Carbodiimides, Uronium salts) [25] | Key variable for classification models in amide bond formation. | Model recommendations (e.g., carbodiimide-based) inform cost-effective and scalable reagent selection. |

| Ligand Libraries (e.g., BINAP, XPhos derivatives) | Crucial for optimizing catalytic cross-couplings (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig) [24]. | HTE-ML identifies optimal ligand for specific substrate pairs, critical for catalyst performance on scale. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) [8] | Enables real-time data collection for continuous processes, enriching ML datasets. | Inline IR/NMR provides high-resolution kinetic data for model refinement in continuous manufacturing. |

| Continuous Flow Reactors [8] | Provides a controlled environment for generating consistent, automatable data. | Addresses sustainability and supply chain issues; data from flow reactors is ideal for ML and automation. |

The integration of machine learning, particularly predictive models with uncertainty quantification like Deep Kernel Learning, with high-throughput experimentation creates a powerful, data-driven framework for scaling up organic reactions. The protocols outlined provide researchers with a concrete pathway to generate high-quality data and build reliable models. This approach moves process chemistry away from reliance on serendipity and intuition and towards a more efficient, predictive science. By leveraging these tools, scientists and drug development professionals can de-risk the scale-up process, optimize resource allocation, and significantly accelerate the development of robust synthetic processes, ultimately shortening the timeline from discovery to manufacturing [8] [24] [17].

Green chemistry, formally defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances, provides a critical framework for developing sustainable industrial processes [27]. The twelve principles of green chemistry established by Paul Anastas and John Warner offer a systematic approach to addressing environmental impacts across the chemical lifecycle, from design to disposal [28]. For researchers scaling up organic reactions, particularly in pharmaceutical development, integrating these principles enables the creation of synthetic routes that are not only environmentally responsible but also economically advantageous through reduced waste treatment costs, improved safety profiles, and more efficient resource utilization.

The pharmaceutical industry faces particular challenges in process scale-up where economic viability must be balanced against increasingly stringent environmental regulations. This application note details practical methodologies and metrics for implementing green chemistry principles in process development, with a focus on techniques that enhance sustainability while maintaining economic competitiveness. By adopting these approaches, researchers and drug development professionals can advance the transition toward more sustainable chemical manufacturing.

Core Green Chemistry Principles for Process Development

Foundational Framework

The twelve principles of green chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing safer, more efficient chemical processes [27] [28]. For scaling optimized organic reactions, several principles take on particular significance:

- Prevention of Waste: Designing chemical syntheses to prevent waste generation rather than treating or cleaning up waste after it is formed

- Atom Economy: Designing syntheses to maximize incorporation of all starting materials into the final product, minimizing byproduct formation [28]

- Reduction of Hazardous Chemicals: Developing processes that use and generate substances with minimal toxicity to humans and the environment

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: Selecting solvents that minimize environmental impact while maintaining reaction efficiency [29]

- Energy Efficiency: Conducting reactions at ambient temperature and pressure whenever possible

- Catalytic Processes: Preferring catalytic reactions over stoichiometric ones to minimize waste [28]

These principles align with the federal Pollution Prevention Act of 1990, which establishes pollution prevention as national policy in the United States [27].

Quantitative Green Metrics

Evaluating process sustainability requires quantitative metrics that enable objective comparison of alternative synthetic routes. Three essential metrics for assessing green chemistry performance include:

- Atom Economy: Calculated as (molecular weight of desired product / molecular weight of all reactants) × 100%, measuring how efficiently a reaction utilizes starting atoms [28]

- Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME): Determined as (mass of desired product / total mass of all reactants) × 100%, providing a practical measure of material utilization

- Optimum Efficiency: A comprehensive metric that combines yield, atom economy, and stoichiometric factors to evaluate overall process efficiency [29]

These metrics provide critical data for decision-making during process optimization and scale-up, allowing researchers to quantify improvements in sustainability.

Advanced Methodologies for Sustainable Reaction Optimization

Machine Learning-Driven Reaction Optimization

Artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) have emerged as powerful tools for accelerating green reaction optimization. Bayesian optimization techniques efficiently navigate complex reaction landscapes, balancing multiple objectives such as yield, selectivity, and sustainability criteria [9]. The Minerva ML framework demonstrates robust performance with experimental data-derived benchmarks, efficiently handling large parallel batches, high-dimensional search spaces, and reaction noise present in real-world laboratories [9].

For pharmaceutical process development, ML-driven workflows have successfully optimized challenging transformations such as nickel-catalyzed Suzuki couplings and Buchwald-Hartwig aminations, identifying conditions achieving >95% yield and selectivity while reducing development timelines from months to weeks [9]. These approaches leverage Gaussian Process regressors to predict reaction outcomes and uncertainties, enabling data-driven experimental design that minimizes resource consumption while maximizing information gain.

Figure 1: Machine Learning Workflow for Reaction Optimization. This workflow integrates high-throughput experimentation with Bayesian optimization to efficiently identify optimal reaction conditions while minimizing experimental resources.

Data Mining Existing Experimental Datasets

Leveraging existing experimental data represents a particularly sustainable approach to reaction discovery and optimization. MEDUSA Search, a machine learning-powered search engine, enables mining of tera-scale high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data to identify previously unknown chemical transformations without conducting new experiments [30]. This "experimentation in the past" approach applies sophisticated algorithms to detect reaction products in archived HRMS data, significantly reducing chemical consumption and waste generation associated with traditional screening methods.

The MEDUSA platform employs a novel isotope-distribution-centric search algorithm augmented by two synergistic ML models, enabling rigorous investigation of existing data to support chemical hypotheses without additional laboratory work [30]. This methodology has successfully identified previously undescribed transformations, including heterocycle-vinyl coupling processes in Mizoroki-Heck reactions, demonstrating how historical data can yield new chemical insights with minimal environmental impact.

Solvent Selection and Replacement Strategies