Greenness Assessment of Organic Analytical Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Sustainable Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of greenness assessment for organic analytical methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Greenness Assessment of Organic Analytical Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Sustainable Research

Abstract

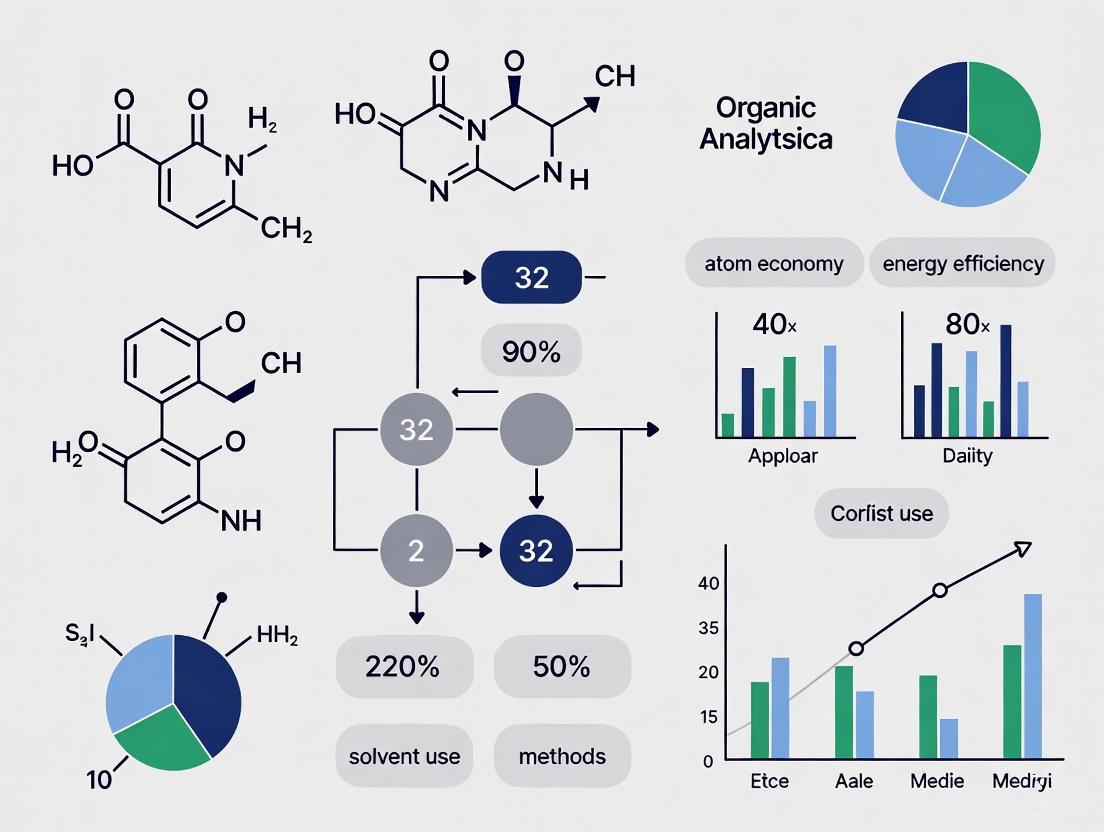

This article provides a comprehensive overview of greenness assessment for organic analytical methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and the critical need for sustainability in pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. The content details major assessment tools like AGREE, GAPI, AMGS, and the emerging White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework, offering practical guidance for method selection, application, and troubleshooting. It further covers validation strategies and comparative analysis to benchmark method performance, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for integrating ecological and practical considerations into analytical workflows.

The Principles and Drivers of Green Analytical Chemistry

The Foundation of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a transformative approach to analytical science that emphasizes environmental stewardship and sustainability while maintaining high standards of accuracy and precision [1]. Originating from the broader green chemistry movement formally established in the 1990s by Paul Anastas and John C. Warner, GAC specifically addresses the environmental impact of analytical methodologies [2] [3]. This discipline optimizes analytical processes to ensure they are safe, non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [4].

The foundational framework for GAC adapts the 12 principles of green chemistry to fit analytical contexts, providing a comprehensive strategy for reimagining how chemical analysis is conducted [1]. These principles prioritize waste prevention, safer solvents, energy efficiency, and real-time analysis to collectively reduce the ecological footprint of analytical laboratories while driving innovation in scientific research and industrial applications [1] [4]. The transition to greener analytical methods is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development, where traditional techniques often consume large quantities of hazardous solvents and generate substantial waste [5].

The 12 SIGNIFICANCE Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a systematic framework for designing environmentally benign analytical methods. The "SIGNIFICANCE" acronym offers a practical way to remember and apply these principles in research and method development [5].

Table 1: The 12 SIGNIFICANCE Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Letter | Principle Name | Core Concept | Application in Analytical Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | Select Direct Analytical Techniques | Choose methods that require minimal or no sample preparation | Direct injection techniques; in-situ measurements; online monitoring [5] |

| I | Integrate Analytical Processes & Operations | Combine sampling, preparation, and analysis into streamlined workflows | Automated systems; online extraction coupled with analysis; flow injection techniques [4] |

| G | Generate as Little Waste as Possible | Prevent waste rather than treating or cleaning it up after generation | Micro-extraction techniques; miniaturized equipment; solvent-less methods [1] [5] |

| N | Never Use Large Amounts of Sample | Minimize sample size while maintaining analytical performance | Micro-scale analysis; capillary techniques; low-volume extraction methods [4] |

| I | Implement Automated & Miniaturized Methods | Use small-scale, automated systems to reduce reagent consumption and increase safety | Lab-on-a-chip devices; automated sample processors; microfluidic systems [1] |

| F | Favor Reusable & Renewable Materials | Choose sustainable materials over single-use products | Regenerable sensors; reusable extraction phases; bio-based solvents [1] [2] |

| I | Increase Safety for the Operator | Design methods that reduce exposure to hazardous substances | Closed-system analysis; replacement of toxic reagents; remote operation [4] |

| C | Carry Out In-Situ Measurements | Perform analysis at the point of need rather than transporting samples | Field-portable instruments; real-time sensors; on-site monitoring devices [1] |

| A | Avoid Derivatization Steps | Eliminate unnecessary chemical modification of analytes | Direct analysis methods; simplified sample preparation; reduced reaction steps [2] |

| N | Note Energy Consumption | Minimize power requirements of analytical equipment | Energy-efficient instruments; ambient temperature processes; alternative energy sources [1] |

| C | Combine Different Techniques | Use hybrid methods to enhance efficiency and reduce steps | Coupled chromatography-spectroscopy; extraction-chromatography systems [6] |

| E | Eliminate or Replace Hazardous Reagents | Substitute dangerous chemicals with safer alternatives | Green solvents (water, CO₂, ionic liquids); biodegradable reagents; less toxic catalysts [1] [5] |

Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

The implementation of GAC principles requires systematic assessment tools to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods. Several validated metrics have been developed to quantify the "greenness" of analytical procedures [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Developer(s) | Evaluation Criteria | Output Format | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | US Government Agencies [4] | Persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, corrosivity | Pictogram (four quadrants) | Initial screening of method environmental impact |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Plotka-Wasylka et al. [4] | Entire method lifecycle from sampling to waste disposal | Color-coded pentagram (15 parameters) | Comprehensive evaluation of analytical procedures |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric) | Pena-Pereira et al. [4] | All 12 GAC principles with weighting options | Circular pictogram with overall score | Holistic assessment aligning with GAC principles |

The AGREE tool is particularly valuable as it provides a holistic evaluation based on all 12 GAC principles, generating an overall score between 0-1 and a visual representation that quickly communicates method greenness [4]. This tool helps researchers identify specific areas for improvement in their analytical methods and supports the development of greener alternatives in pharmaceutical analysis and other fields.

Diagram 1: SIGNIFICANCE Principles Workflow (47 characters)

Green Alternatives to Conventional Analytical Techniques

Chromatographic Techniques

Traditional chromatographic methods like HPLC and GC are resource-intensive, often generating 1-1.5 liters of waste per day [5]. Green alternatives focus on reducing solvent consumption, replacing hazardous mobile phases, and improving energy efficiency.

Table 3: Comparison of Conventional vs. Green Chromatographic Methods

| Technique | Solvent Consumption | Waste Generation | Energy Demand | Typical Applications | Greenness Score (AGREE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional HPLC | 500-2000 mL/day [5] | High (1-1.5 L/day) [5] | High (pumps, oven, detector) | Pharmaceutical QC, environmental analysis | 0.3-0.5 [4] |

| UHPLC (Ultra-High Performance LC) | 50-500 mL/day [5] | Low-Medium | Medium-High | High-throughput analysis, method development | 0.6-0.7 [5] |

| SFC (Supercritical Fluid Chromatography) | 5-50 mL/day (co-solvent) [1] | Very Low | Medium | Chiral separations, natural products | 0.7-0.8 [1] |

| HPTLC (High-Performance TLC) | 10-100 mL/analysis [5] | Low | Low | Herbal drugs, purity testing | 0.6-0.75 [5] |

Sample Preparation Methods

Sample preparation is often the most polluting stage in analytical workflows [5]. Green approaches focus on minimizing or eliminating solvents, reducing steps, and improving efficiency.

Table 4: Comparison of Sample Preparation Techniques

| Extraction Technique | Solvent Volume | Extraction Time | Automation Potential | Analytical Performance | Green Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction | 50-500 mL [5] | 30-120 minutes | Low | High recovery for non-polar compounds | Large solvent consumption, hazardous waste |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | 10-50 mL [5] | 20-60 minutes | Medium-High | Good for clean-up and concentration | Reduced solvent vs. LLE, reusable cartridges |

| QuEChERS | 10-15 mL [5] | 15-30 minutes | Medium | Comprehensive multi-analyte extraction | Minimal solvent, high throughput, buffer systems |

| Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Solvent-less [5] | 5-60 minutes | High | Excellent for volatiles, minimal matrix effects | No solvents, reusable fibers, easy automation |

Experimental Protocols for Green Analytical Methods

Green UHPLC Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Principle: Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) utilizes smaller particle sizes (<2μm) and higher pressures to achieve faster separations with significantly reduced solvent consumption compared to conventional HPLC [5].

Protocol:

- Column: Acquity UPLC BEH C18 (100mm × 2.1mm, 1.7μm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol-water gradient (replacing acetonitrile) [5]

- Flow Rate: 0.4-0.6 mL/min (vs. 1-2 mL/min in HPLC)

- Injection Volume: 1-5μL

- Temperature: 40°C

- Detection: PDA detector (210-400nm)

- Analysis Time: 5-10 minutes (vs. 20-40 minutes in HPLC)

Performance Data: UHPLC reduces solvent consumption by 60-80% and analysis time by 50-70% while maintaining equivalent resolution to HPLC methods [5].

QuEChERS Extraction for Multi-Residue Analysis

Principle: QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) employs acetonitrile extraction followed by dispersive SPE clean-up, significantly reducing solvent use compared to traditional methods [5].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 10g sample with 10mL acetonitrile

- Extraction: Add 4g MgSO₄ (drying agent) and 1g NaCl (salting out)

- Shaking: Vortex for 1 minute

- Centrifugation: 5000rpm for 5 minutes

- Clean-up: Transfer 1mL supernatant to d-SPE tube containing:

- 150mg MgSO₄ (removes residual water)

- 25mg PSA (removes fatty acids and sugars)

- Analysis: Direct injection of 5μL into LC-MS/MS

Green Benefits: Uses only 10-15mL solvent per sample vs. 100-300mL in traditional methods; processing time reduced from 4-6 hours to 30-40 minutes [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Green Alternatives for Analytical Laboratory Reagents

| Traditional Reagent | Green Alternative | Function | Environmental & Safety Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (HPLC) | Ethanol-water mixtures [5] | Mobile phase | Lower toxicity, biodegradable, renewable sourcing |

| Dichloromethane (extraction) | Supercritical CO₂ [1] | Extraction solvent | Non-flammable, non-toxic, easily removed |

| Hexane (partitioning) | Cyclopentyl methyl ether [1] | Organic solvent | Higher boiling point, lower toxicity, not peroxidize |

| Traditional SPE sorbents | Molecularly imprinted polymers [6] | Selective extraction | Higher specificity, reusability, reduced solvent needs |

| Derivatization agents | Direct analysis methods [2] | Analyte modification | Eliminates hazardous reagents and additional steps |

| Toxic metal catalysts | Bio-based catalysts [2] | Reaction catalysis | Biodegradable, from renewable resources, non-toxic |

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry principles represents a paradigm shift in how chemical analysis is conceived and performed. By implementing the 12 SIGNIFICANCE principles, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of their analytical workflows while maintaining, and often enhancing, analytical performance [1] [4].

The future of GAC is promising, with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, miniaturized devices, and advanced solvent systems offering new opportunities to optimize analytical processes [1]. As regulatory frameworks increasingly mandate sustainable practices, familiarity with GAC principles and greenness assessment tools will become essential for analytical chemists [4]. By embracing these approaches, the scientific community can transform analytical methodologies into tools that not only achieve high performance but also align with global sustainability goals [1].

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by an increasing awareness of its environmental and economic footprint. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods by reducing waste, energy consumption, and hazardous reagents [7] [8]. This movement represents a fundamental shift in how analytical challenges are approached, where environmental benignity is considered alongside traditional performance metrics like accuracy and sensitivity. The evolution from simple greenness metrics to comprehensive assessment frameworks enables researchers to make informed decisions that balance analytical efficacy with sustainability goals [8].

The imperative for greener analytical methods extends beyond environmental concerns to encompass significant economic considerations. Methods that consume less solvent and energy not only reduce environmental impact but also lower operational costs, creating a compelling business case for sustainability in drug development and analytical laboratories [7] [8]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of contemporary greenness assessment tools, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers and drug development professionals in quantifying and improving their analytical methods' sustainability profile.

Comparative Analysis of Greenness Assessment Metrics

Several metrics have been developed to evaluate the environmental impact of analytical methods, each with distinct approaches, advantages, and limitations [7] [8]. These tools provide either numerical scores, visual representations, or both to facilitate method comparison and sustainability assessment. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major greenness assessment metrics:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Assessment Approach | Output Format | Scope | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Binary evaluation against four environmental criteria [8] | Pictogram with four quadrants [8] | Entire method | Simple, user-friendly [8] | Lacks granularity; doesn't assess full workflow [8] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Penalty points for non-green attributes subtracted from base score of 100 [8] | Numerical score (0-100) [8] | Entire method | Facilitates direct comparison between methods [8] | Relies on expert judgment; lacks visual component [8] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Evaluation of entire analytical process from sample collection to detection [8] | Five-part, color-coded pictogram [8] | Comprehensive workflow | Visual identification of high-impact stages [8] | No overall score; subjective color assignments [8] |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness) | Based on 12 principles of GAC [8] | Circular pictogram + numerical score (0-1) [8] | Entire method | Comprehensive coverage; user-friendly interface [8] | Doesn't sufficiently account for pre-analytical processes [8] |

| AGREEprep | Focused specifically on sample preparation [8] | Visual and quantitative outputs [8] | Sample preparation only | Addresses often-overlooked high-impact stage [8] | Must be used with broader tools for full method evaluation [8] |

| GEMAM (Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods) | Based on 12 principles of GAC and 10 factors of green sample preparation [9] | Pictogram with seven hexagons + numerical score (0-10) [9] | Comprehensive including operator impact | Simple, flexible, and comprehensive [9] | Newer metric with less established track record [9] |

Case Study Application: Comparative Evaluation of SULLME Method

A case study evaluating a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method for determining antiviral compounds demonstrates how these complementary tools provide a multidimensional sustainability perspective [8]. The method was assessed using four different metrics, yielding the following quantitative results:

Table 2: Multi-Metric Greenness Assessment of SULLME Method for Antiviral Compound Determination

| Assessment Metric | Overall Score | Key Strengths Identified | Key Weaknesses Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoGAPI (Modified Green Analytical Procedure Index) | 60/100 | Use of green solvents and reagents; microextraction limiting solvent to <10 mL/sample [8] | Specific storage requirements; moderately toxic substances; vapor emissions; >10 mL waste/sample without treatment [8] |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness) | 56/100 | Miniaturization; semiautomation; no derivatization; small sample volume (1 mL) [8] | Toxic and flammable solvents; low throughput (2 samples/hour); moderate waste generation [8] |

| AGSA (Analytical Green Star Analysis) | 58.33/100 | Semi-miniaturization; avoidance of derivatization [8] | Manual sample handling; multiple hazard pictograms; mixed renewable/non-renewable reagents; no waste management [8] |

| CaFRI (Carbon Footprint Reduction Index) | 60/100 | Low energy consumption (0.1-1.5 kWh/sample); no energy-intensive equipment [8] | No clean/renewable energy; no CO₂ tracking; long-distance transportation; >10 mL organic solvents/sample [8] |

This multidimensional assessment reveals both consistent patterns and unique insights across different sustainability dimensions. The method demonstrates strengths in miniaturization and solvent reduction but consistently shows weaknesses in waste management, reagent safety, and energy sourcing considerations [8].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment and Method Validation

Protocol for Comprehensive Method Greenness Assessment

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for conducting a comprehensive greenness assessment using multiple complementary metrics:

Step 1: Data Collection - Compile comprehensive data on all method parameters including:

- Reagent types, quantities, and hazard classifications [9]

- Energy consumption per analysis (kWh) [8] [9]

- Waste generation volumes and treatment protocols [8] [9]

- Sample collection, transport, and storage requirements [9]

- Instrumentation specifications and automation capabilities [9]

Step 2: Metric Selection and Application - Select appropriate metrics based on assessment goals:

- For comprehensive workflow assessment: Apply GAPI or AGREE [8]

- For sample preparation focus: Include AGREEprep [8]

- For climate impact: Calculate CaFRI score [8]

- For simplified overall scoring: Use Analytical Eco-Scale or GEMAM [8] [9]

Step 3: Results Integration and Improvement Planning - Synthesize findings from multiple metrics to identify consistent strengths and weaknesses across different environmental dimensions. Develop targeted improvements addressing highest-impact opportunities [8].

Protocol for Analytical Method Validation

Robust method validation is prerequisite for meaningful greenness assessment, ensuring that sustainable methods maintain analytical performance [10]. The following protocol provides a comprehensive validation framework:

Experimental Design for Validation:

- Perform three complete calibration curves across three different days (nine total replicates) [10]

- Analyze quality control samples at multiple concentrations throughout each sequence

- Include blank samples to assess carryover and specificity [10]

Key Validation Parameters and Calculations:

- Accuracy and Precision: Calculate intra-day and inter-day accuracy (% bias) and precision (% relative standard deviation) from replicate measurements [10]

- Linearity and Calibration: Evaluate heteroscedasticity, compare weighting models, and test linear vs. quadratic calibration curves [10]

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Determine via signal-to-noise approach or standard deviation of blank measurements [10]

- Selectivity and Specificity: Verify absence of interference from matrix components [10]

- Carryover: Assess by injecting blank samples after high-concentration standards [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Methods

| Item | Function | Green Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvents | Compound isolation from matrix [8] [9] | Bio-based solvents; supercritical CO₂; deep eutectic solvents [8] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enhance detection of non-UV absorbing or non-volatile compounds | Less toxic alternatives; reagent-free techniques [9] |

| Sorbent Materials | Extraction and clean-up in sample preparation [9] | Sustainable materials; reduced sorbent volumes [9] |

| Calibration Standards | Method calibration and quantification | In-house prepared from pure materials; sustainable sourcing [10] |

| Mobile Phase Additives | Modify chromatographic separation | Green alternatives; minimized quantities [8] |

The quantitative assessment of analytical methods' environmental impact represents both an ecological imperative and an economic opportunity for research and drug development. The evolving landscape of greenness assessment metrics, from foundational tools like NEMI to comprehensive frameworks like AGREE and GEMAM, provides researchers with sophisticated means to quantify, compare, and improve their methods' sustainability profiles [7] [8] [9].

The case study demonstrates that multi-metric assessment offers the most complete sustainability picture, revealing complementary insights that might be missed by single-metric approaches [8]. As global awareness of climate change and resource constraints grows, the integration of comprehensive greenness assessment into analytical method development and validation will become increasingly crucial [8]. By adopting these assessment protocols and prioritizing sustainability alongside traditional performance metrics, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce their environmental footprint while simultaneously achieving economic benefits through reduced reagent consumption and waste disposal costs.

The pharmaceutical industry and analytical laboratories are increasingly prioritizing sustainability, driven by the need to minimize environmental impact while maintaining scientific rigor and regulatory compliance. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on reducing hazardous substance use, energy consumption, and waste generation throughout analytical workflows [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate greenness assessment tools is essential for evaluating and improving the environmental footprint of organic analytical methods without compromising data quality essential for patient safety [11].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of major greenness assessment metrics, supported by experimental data and practical implementation protocols. By objectively evaluating the strengths and limitations of each tool, this resource enables scientists to make informed decisions when designing, optimizing, and validating analytical methods aligned with sustainability goals, such as AstraZeneca's ambition to achieve carbon zero status for analytical laboratories by 2030 [11].

Comparative Analysis of Greenness Assessment Metrics

Multiple metrics have been developed to evaluate the environmental impact of analytical methods, each with distinct approaches, scoring systems, and applications. The evolution of these tools has progressed from basic binary indicators to comprehensive multi-parameter assessments that provide both visual and quantitative outputs [8]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major greenness assessment tools used in analytical chemistry.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Assessment Approach | Scoring System | Key Parameters Evaluated | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Binary pictogram | Pass/Fail based on 4 criteria | Persistence, toxicity, corrosivity, waste quantity | Basic initial screening [8] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Penalty point system | Score out of 100 (higher = greener) | Reagents, waste, energy, toxicity | Semi-quantitative method comparison [11] [8] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Color-coded pictogram | Qualitative visual assessment | All stages from sampling to waste | Comprehensive workflow analysis [8] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | 12 GAC principles | 0-1 scale (higher = greener) | Toxicity, waste, energy, safety, practicality | Holistic method evaluation [11] [8] |

| AGREEprep | Sample preparation focus | 0-1 scale (higher = greener) | Solvent consumption, energy, hazardousness, waste | Sample preparation optimization [12] [8] |

| AMGS (Analytical Method Greenness Score) | Multi-dimensional LC focus | Comprehensive scoring | Solvent EHS, solvent energy, instrument energy | Chromatographic method assessment [11] |

| AGSA (Analytical Green Star Analysis) | Star-shaped diagram | Integrated scoring with visual | Toxicity, waste, energy, solvent consumption | Multi-criteria comparative analysis [8] |

| CaFRI (Carbon Footprint Reduction Index) | Climate impact focus | Carbon reduction assessment | Energy source, transportation, emissions tracking | Carbon footprint evaluation [8] |

Detailed Metric Characteristics and Applications

The AGREE metric represents one of the most comprehensive tools, evaluating methods against all 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and providing both a unified pictogram and a numerical score between 0 and 1. This facilitates direct comparison between methods, though it involves some subjective weighting of criteria and doesn't fully account for pre-analytical processes [8]. The Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), developed by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute with industry partners, specifically addresses chromatographic methods by evaluating environmental impact across multiple dimensions including solvent energy consumption during production and disposal, safety/toxicity profiles, and instrument energy consumption [11].

For sample preparation evaluation, AGREEprep offers specialized assessment of this often resource-intensive analytical step. As sample preparation frequently involves substantial solvent use, energy consumption, and potentially hazardous reagents, this dedicated tool addresses a crucial but frequently overlooked component of the analytical workflow [8]. The recently developed Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) aligns analytical chemistry with broader climate goals by estimating and encouraging reduction of carbon emissions associated with analytical procedures, considering both direct and indirect contributions to carbon footprints throughout method workflows [8].

Case Study: Multi-Metric Assessment of an Analytical Method

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A recent study applied multiple greenness assessment tools to evaluate a Sugaring-Out-Induced Homogeneous Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (SULLME) method developed for determining antiviral compounds [8]. This comprehensive evaluation utilized MoGAPI, AGREE, AGSA, and CaFRI metrics to provide a multidimensional perspective on the method's environmental profile.

Materials and Reagents: The method employed green solvents alongside moderately toxic substances, with total solvent consumption maintained below 10 mL per sample through microextraction techniques. No derivatization steps were required, reducing additional chemical usage [8].

Instrumentation and Equipment: Standard analytical instrumentation was utilized without energy-intensive specialized equipment. The method maintained analytical energy consumption within a relatively low range of 0.1–1.5 kWh per sample [8].

Assessment Procedure: Each metric tool was applied according to its standardized protocol. MoGAPI provided a modified pictogram approach with cumulative scoring. AGREE evaluated alignment with 12 GAC principles. AGSA employed its star-shaped visualization, and CaFRI focused specifically on carbon footprint considerations across the method lifecycle [8].

Comparative Results and Data Analysis

The multi-metric assessment generated complementary insights into the SULLME method's environmental performance, with results summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Multi-Metric Greenness Assessment Results for SULLME Method

| Assessment Metric | Overall Score | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoGAPI | 60/100 | Green solvents, microextraction (<10 mL/sample), no additional sample treatment | Specific storage requirements, moderate toxicity substances, vapor emissions, >10 mL waste/sample without treatment |

| AGREE | 56/100 | Miniaturization, semi-automation, no derivatization, small sample volume (1 mL) | Toxic/flamable solvents, low throughput (2 samples/hour), moderate waste generation |

| AGSA | 58.33/100 | Semi-miniaturization, avoided derivatization | Manual sample handling, multiple pretreatment steps, 6+ hazard pictograms, no waste management |

| CaFRI | 60/100 | Low energy consumption (0.1-1.5 kWh/sample), no energy-intensive equipment | No renewable energy, no CO2 tracking, long-distance transportation, no waste procedure, >10 mL organic solvents/sample |

The case study demonstrates how complementary metrics provide a more comprehensive sustainability profile than any single tool. While the method showed strengths in miniaturization and solvent selection, consistent limitations emerged in waste management, reagent safety, and energy sourcing across multiple assessments [8].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment Implementation

Standardized Assessment Workflow

Implementing greenness assessment requires a systematic approach to ensure consistent and comparable results. The following workflow provides a standardized protocol for evaluating organic analytical methods:

Phase 1: Method Characterization

- Document all method parameters including sample volume, solvent types and volumes, reagent quantities, and equipment requirements

- Record energy consumption specifications for all instruments

- Identify waste streams and management procedures

- Note required safety precautions and hazard classifications [8]

Phase 2: Metric Selection and Application

- Select appropriate metrics based on method characteristics and assessment goals

- Apply each metric according to its standardized calculation methodology

- For pictogram-based tools (GAPI, AGREE), complete all designated sections

- For scoring systems (Eco-Scale, AMGS), calculate penalty points or credit allocations [11] [8]

Phase 3: Data Interpretation and Improvement Planning

- Compare scores against method alternatives or benchmark values

- Identify specific parameters contributing to poor performance

- Develop optimization strategies targeting lowest-scoring elements

- Implement improvements and reassess greenness [11]

AGREEprep Assessment Methodology

For specialized evaluation of sample preparation, the AGREEprep protocol follows this specific methodology:

- Compile data on sample preparation-specific parameters: solvent consumption, energy requirements, equipment usage, and generated waste

- Evaluate each of the 10 AGREEprep criteria on a 0-1 scale

- Calculate overall score as the average of all criteria ratings

- Generate the AGREEprep pictogram visualizing performance across all assessed parameters [12]

Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) Implementation

The AMGS methodology, particularly relevant for chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical settings, involves:

- Collect solvent data including types, volumes, and EHS (Environmental, Health, Safety) profiles

- Calculate solvent energy impact based on production and disposal requirements

- Determine instrument energy consumption during method operation

- Compute final AMGS through integrated algorithm balancing all parameters [11]

Visualization of Greenness Assessment Workflows

Greenness Assessment Selection and Implementation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting and implementing appropriate greenness assessment tools based on methodological characteristics and sustainability objectives.

Greenness Assessment Impact on Method Development Lifecycle

This diagram depicts how greenness assessment integrates throughout the analytical method development lifecycle, creating continuous improvement toward sustainability goals.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

Implementing green analytical principles requires both methodological optimization and appropriate selection of reagents and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions that support sustainability goals in analytical laboratories.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Attributes | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Alternative extraction solvents | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable sourcing | Customizable for specific applications; used in metal extraction and bioactive compound recovery [13] |

| Bio-based Surfactants (e.g., rhamnolipids, sophorolipids) | Replacement for PFAS-based surfactants | Biodegradable, low eco-toxicity, renewable | Effective in textile manufacturing, cosmetics, and cleaning products [13] |

| Water-based Mobile Phases | Chromatographic separations | Non-toxic, non-flammable, readily available | Replaces acetonitrile and methanol in reversed-phase LC when method compatibility allows [13] |

| Mechanochemical Reactants | Solvent-free synthesis | Eliminates solvent waste, reduced energy requirements | Ball milling techniques for pharmaceutical synthesis and material preparation [13] |

| Silver Nanoparticles | Catalytic and analytical applications | Synthesis possible in aqueous solutions | Plasma-driven electrochemical synthesis in water reduces solvent use [13] |

The systematic assessment of method greenness using standardized metrics provides researchers and pharmaceutical developers with critical data to balance analytical performance with environmental responsibility. As demonstrated through comparative evaluation and case studies, multi-metric approaches offer the most comprehensive sustainability profiling, enabling identification of improvement opportunities across method workflows.

The evolving landscape of greenness assessment tools continues to address different aspects of environmental impact, from general sustainability (AGREE, GAPI) to specialized applications (AGREEprep, AMGS) and emerging climate-specific concerns (CaFRI). Implementation of these assessment frameworks, combined with appropriate reagent selection and method optimization, supports the pharmaceutical industry's progress toward ambitious sustainability targets while maintaining the rigorous analytical standards required for drug development and quality control.

The pursuit of sustainability in analytical laboratories has evolved significantly from the initial principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). While GAC successfully raised awareness about reducing the environmental impact of analytical methods, its primary focus on ecological aspects often overlooked critical methodological requirements. White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has emerged as a holistic framework that addresses this limitation by integrating environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical applicability. This paradigm shift, introduced by Nowak et al. in 2021, represents a more comprehensive approach to sustainable method development in analytical chemistry [14] [15].

The fundamental concept of WAC employs the RGB color model as its foundational structure, where three primary components—Red (analytical performance), Green (environmental impact), and Blue (practical & economic factors)—combine to produce "white" when balanced optimally [14] [15]. This model acknowledges that a truly sustainable method must excel simultaneously across all three dimensions rather than maximizing greenness at the expense of functionality [16]. The WAC framework establishes 12 principles that expand upon the original GAC principles, providing a more balanced set of criteria for method development and evaluation [14].

For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting the WAC framework enables a more comprehensive assessment of analytical methods, ensuring they are not only environmentally responsible but also scientifically valid and practically feasible for routine use [15]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development, where method robustness, reliability, and practicality are as crucial as environmental considerations [11].

The RGB Components of White Analytical Chemistry

The Green Component: Environmental Sustainability

The Green component forms the ecological foundation of WAC, incorporating the established principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [8]. This dimension focuses primarily on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods throughout their entire lifecycle—from sample preparation to final analysis and waste disposal [8] [9]. Key priorities include reducing or eliminating hazardous chemicals and solvents, minimizing energy consumption, decreasing waste generation, and implementing safety measures for laboratory personnel [8] [9].

Several metric tools have been developed to quantify and evaluate the greenness of analytical methods. The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric provides a comprehensive assessment based on the 12 principles of GAC, offering both a numerical score (0-1) and a visual pictogram for intuitive interpretation [8]. The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) employs a five-part color-coded pictogram that assesses the entire analytical process from sample collection to final detection, enabling identification of high-impact stages within a method [8]. More recently, the Analytical Green Star Area (AGSA) introduced a star-shaped diagram that evaluates multiple green criteria including reagent toxicity, waste generation, energy use, and solvent consumption, with the total star area providing direct visual comparison between methods [15].

The Red Component: Analytical Performance

The Red component addresses the analytical performance and functionality of methods, ensuring they meet necessary quality standards for their intended applications [17]. This dimension focuses on fundamental validation parameters that determine the reliability and effectiveness of analytical methods, including sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision, and robustness [14] [17]. The red dimension acknowledges that environmentally friendly methods are only valuable if they deliver scientifically sound and defensible results.

A significant development in quantifying this component is the introduction of the Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) in 2025 [17]. This metric tool evaluates ten key analytical parameters guided by ICH validation recommendations and good laboratory practice principles:

- Repeatability (variation when measurements are performed by a single analyst)

- Intermediate precision (variation within a single laboratory)

- Trueness (agreement between measured and reference values)

- Linearity (ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration)

- Range (interval between upper and lower concentration levels)

- Limit of detection (LOD) (lowest detectable analyte concentration)

- Limit of quantification (LOQ) (lowest quantifiable analyte concentration)

- Robustness (resistance to deliberate variations in method parameters)

- Matrix effect (impact of sample components on analyte measurement)

- Specificity/selectivity (ability to distinguish and measure analyte in mixture) [17]

RAPI employs a star-shaped pictogram with different color intensities (white to dark red) representing performance scores for each criterion, along with a final numerical assessment (0-100) [17].

The Blue Component: Practicality and Economic Factors

The Blue component addresses the practical and economic aspects of analytical methods, focusing on factors that influence their implementation in routine laboratory settings [18]. This dimension emphasizes operational simplicity, cost-efficiency, and time-efficiency, advocating for methods that are rapid, economical, easy to use, and require readily available instrumentation and materials [18]. Key considerations include sample throughput, degree of automation, availability of reagents and materials, required sample amount, and the need for specialized equipment or operator skills [18].

The primary metric for evaluating this component is the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI), introduced in 2023 [18] [15]. BAGI assesses ten practical criteria:

- Analysis type (quantitative, confirmatory, etc.)

- Type and number of analytes

- Analytical technique

- Simultaneous sample preparation capability

- Type of sample preparation

- Sample throughput (samples per hour)

- Availability of reagents and materials

- Need for preconcentration

- Degree of automation

- Sample amount required [18]

Each criterion receives a score of 10.0, 7.5, 5.0, or 2.5 points, corresponding to high, medium, low, or no practicality, resulting in a final numerical score between 25.0 and 100.0 [18]. Methods scoring above 60.0 are considered practically applicable, with the results visualized through an asteroid pictogram where dark blue, blue, light blue, and white indicate the respective score levels [18].

Comparative Analysis of WAC Assessment Tools

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Major WAC Assessment Metrics

| Metric Tool | RGB Focus | Evaluation Criteria | Output Format | Score Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [8] | Green | 12 principles of GAC | Circular pictogram + numerical score | 0-1 | General analytical methods |

| GAPI [8] | Green | Entire analytical process | 5-part color-coded pictogram | Qualitative only | Method stage identification |

| AGSA [15] | Green | Reagent toxicity, waste, energy, solvents | Star-shaped diagram + area calculation | Numerical + visual | Direct method comparison |

| RAPI [17] | Red | 10 analytical performance parameters | Star pictogram + numerical score | 0-100 | Analytical validation assessment |

| BAGI [18] | Blue | 10 practical & economic factors | Asteroid pictogram + numerical score | 25-100 | Practical applicability assessment |

| RGB12 [14] | White (combined) | 4 red, 4 green, 4 blue principles | Color mixing model | Color saturation levels | Holistic method optimization |

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Industry Case Study - Solvent Selection Criteria in HPLC Methods

| Solvent | Green Profile | Practical Considerations | Performance Impact | Overall WAC Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | High toxicity, fossil-based | High cost, supply chain issues | Excellent chromatographic properties | Poor (despite good red score) |

| Ethanol [19] | Renewable, low toxicity | Low cost, readily available | Higher viscosity, UV cut-off ~210 nm | Good (balanced RGB profile) |

| Cyrene [19] | Biobased, biodegradable, non-toxic | Non-flammable, cheaper than ACN | High UV cut-off (350 nm), viscosity challenges | Moderate (limited application scope) |

| Methanol | Moderate toxicity, fossil-based | Low cost, widely available | Good chromatographic properties | Fair (environmental concerns) |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies in WAC

Pharmaceutical Analysis Case Study

A 2023 study demonstrated the application of WAC principles in developing a chromatographic method for simultaneous determination of moxifloxacin and metronidazole [19]. Researchers replaced traditional solvents with Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone), a green biobased solvent derived from cellulose, as a mobile phase component in reversed-phase chromatography [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Stationary phase: Monolithic C18 column (100 × 4.6 mm)

- Mobile phase: Cyrene:ethanol:0.1 M sodium acetate buffer pH 4.25 (8:13:79, v/v/v)

- Detection: UV with dual wavelength monitoring (below and above 350 nm)

- Sample preparation: Minimal sample pretreatment

- Method validation: Full validation per ICH guidelines

WAC Assessment Results:

- Green Profile: AGREE evaluation confirmed significantly improved greenness compared to acetonitrile-based methods [19]

- Practical Performance: BAGI score indicated good practicality due to simple operation and readily available materials [19]

- Analytical Performance: RAPI assessment demonstrated satisfactory validation parameters meeting pharmaceutical requirements [19]

- Overall Whiteness: RGB12 tool confirmed balanced RGB profile, resulting in high whiteness score [19]

Multi-residue Analysis in Complex Matrices

A study focusing on pesticide detection in bee pollen demonstrated effective WAC implementation [18]. The method employed ultrasound-assisted extraction followed by liquid chromatography and quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UAE-LC-QTOF-MS) for 79 target compounds [18].

Key Method Characteristics:

- Sample throughput: 2-4 samples per hour

- Automation level: Semi-automated with LC autosampler

- Sample amount: Minimal requirement (following blue principles)

- Reagent availability: Readily available chemicals

- Preconcentration: Not required

BAGI Assessment: The method achieved a score of 82.5, significantly exceeding the 60-point practicality threshold, with strengths in multi-analyte capability, sample throughput, and operational simplicity [18].

Implementation Workflow and Strategic Guidance

WAC Method Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for WAC Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in WAC | Green Alternative | Practical Benefit | Performance Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrene [19] | Green mobile phase solvent | Replaces acetonitrile, DMF | Non-flammable, cost-effective | High UV cut-off (350 nm) limits application |

| Ethanol [19] | Green solvent | Replaces methanol, acetonitrile | Readily available, low cost | Higher viscosity affects backpressure |

| Monolithic Columns [19] | Stationary phase | Reduced analysis time | Enables higher flow rates | Limited phase diversity vs. particulate |

| Microextraction Devices [15] | Sample preparation | Solvent volume reduction | Simplicity, minimal equipment | May require method development |

| SPME Fibers [18] | Solvent-free extraction | Eliminates organic solvents | Easy automation | Limited analyte spectrum for some applications |

Strategic Implementation Framework

Successful WAC implementation requires a systematic approach that balances the three RGB components throughout method development:

Initial Assessment Phase: Begin with simultaneous evaluation of all three dimensions using appropriate metric tools (AGREE/GAPI for green, RAPI for red, BAGI for blue) to establish baseline scores [18] [17] [8].

Iterative Optimization Cycle: Employ a continuous improvement process targeting the weakest component while maintaining strengths in other areas. This may involve:

Final Integration: Achieve optimal balance where no single dimension significantly underperforms, resulting in a method with high "whiteness" suitable for sustainable implementation [14] [15].

White Analytical Chemistry represents a significant evolution in sustainable method development, moving beyond the purely environmental focus of Green Analytical Chemistry to embrace a more balanced approach that equally values analytical performance and practical applicability. The RGB model provides a comprehensive framework for developing and assessing methods that are not only environmentally responsible but also scientifically valid and practically feasible for routine implementation.

For researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, adopting the WAC framework enables more informed decision-making in method selection and optimization. The availability of dedicated metric tools like AGREE (green), RAPI (red), and BAGI (blue) facilitates quantitative assessment of each dimension, while integrated approaches like the RGB12 model provide overall whiteness evaluation. As demonstrated in the case studies, successful WAC implementation requires iterative optimization and compromise among the three components, ultimately resulting in methods that support both scientific excellence and sustainability goals in analytical chemistry.

Within the evolving paradigm of green analytical chemistry (GAC), the adoption and development of sustainable organic analytical methods are propelled by a confluence of distinct yet interconnected industry drivers. This guide objectively compares three primary catalysts—regulatory pressures, corporate sustainability goals, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—evaluating their influence, mechanisms, and measurable outcomes on the advancement of eco-friendly analytical techniques such as chromatography.

Comparative Analysis of Industry Drivers

The following table synthesizes the characteristics, impact, and experimental manifestations of each driver based on current research and industry practices.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Drivers in Green Analytical Method Adoption

| Driver | Primary Mechanism of Influence | Typical Measurable Outcomes (Experimental Focus) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Pressures | Compliance with mandatory laws, directives, and pharmacopoeial standards. Drives method updates to meet defined environmental safety criteria [12]. | Reduction in hazardous solvent volume; adoption of approved green alternative solvents; implementation of waste treatment protocols. Quantified via tools like AGREEprep [12]. | Creates a level playing field; ensures minimum environmental standards; directly forces change in regulated industries (e.g., pharmaceuticals) [12]. | Can be slow to change (official method updates are long processes) [12]; may lead to minimal compliance rather than innovation; varies significantly by region, causing complexity for multinationals [20]. |

| Corporate Sustainability Goals | Internal business strategy aligned with ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) performance, cost reduction, and stakeholder expectations [20] [21]. | Reduction in Process Mass Intensity (PMI); lowering of Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) [11]; decreased carbon footprint and solvent costs. | Directly tied to operational efficiency and economic benefits [11]; allows for proactive and innovative approaches (e.g., Quality-by-Design with GAC) [22]; can be faster to implement than regulatory changes. | Risk of "greenwashing" if not backed by data; priorities can shift with business performance; requires internal expertise and tool adoption (e.g., AMGS, life cycle assessment) [11] [23]. |

| UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Provides a voluntary, aspirational global framework for sustainable development. Used for strategic alignment, reporting, and communication [20] [24]. | Method development aligned with specific SDGs (e.g., SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production). Often assessed using holistic metrics like AGREE or White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB models [22]. | Offers a broad, recognized framework for holistic sustainability; enhances reputation and aligns with impact investment [24]; encourages consideration of social and economic pillars alongside environment. | Broad and abstract scope makes direct translation to specific analytical methods challenging [20]; lack of standardized metrics for analytical chemistry [20]; voluntary nature limits coercive power; current geopolitical shifts may affect its influence in some regions [20] [21]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols: Quantifying the Impact of Drivers

The comparative effect of these drivers is best illustrated through experimental data from greenness assessments of developed analytical methods.

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Scores of Analytical Methods Developed Under Different Drivers Data synthesized from research on pharmaceutical analysis methods [22] [11] [23].

| Analytical Method & Target | Primary Development Driver | Greenness Assessment Tool(s) Used | Score / Outcome | Key Green Features Attributed to Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC for simultaneous determination of four antihypertensives [22] | Corporate Sustainability Goals (QbD-GAC integration) | AGREE, Analytical Eco-Scale, AMGS, WAC-RGB | AGREE: >0.8 (estimated high score); Solvent: Ethanol/water with 0.1% FA [22]. | Replacement of hazardous organic solvents with ethanol; optimized method reduced solvent consumption [22]. |

| Generic LC methods for Rosuvastatin API [11] | Regulatory Pressures (Pharmacopoeial standards) | AMGS (Case study evaluation) | High solvent energy & EHS scores identified, highlighting poor sustainability of some standard methods [11]. | Analysis quantified the significant cumulative environmental burden (e.g., ~18,000 L mobile phase/year), creating a case for regulatory method re-evaluation [11]. |

| Evaluation of 174 CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeia standard methods [12] | Regulatory Pressures | AGREEprep | 67% of methods scored below 0.2 (on a 0-1 scale) [12]. | Quantified the poor greenness of many existing official methods, urging regulatory agencies to phase them out [12]. |

| Not explicitly stated, but alignment demonstrated in sustainability reports | UN SDGs (e.g., SDG 9, 12, 13) | GAPI, AGREE, NEMI | Varies by method. High-scoring methods would feature minimal waste, safe chemicals, and energy efficiency [23]. | Methods are developed or selected to contribute to reporting on SDG targets like responsible consumption, industry innovation, and climate action [24]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Developing a Green HPLC Method Under Corporate Sustainability Goals Based on the integrated Quality-by-Design (QbD) and GAC approach for simultaneous drug analysis [22].

Method Development & Optimization:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): A systematic DoE is employed to optimize critical method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, organic modifier percentage, flow rate, column temperature). This minimizes the number of experiments, aligning with GAC principles [22] [11].

- Mobile Phase Selection: Hazardous traditional solvents like acetonitrile are replaced with greener alternatives (e.g., ethanol). A tool like the Green Solvents Selecting Tool (GSST) can be used to justify the choice [22].

- Chromatographic Conditions: A standard ODS column is used. The mobile phase consists of 0.1% formic acid in water (pH~2.5) and ethanol. UV detection is set at 220 nm [22].

Method Validation: The method is validated per ICH guidelines for linearity, accuracy, precision, LOD, LOQ, robustness, and ruggedness to ensure analytical performance is not compromised [22].

Greenness Assessment:

- Multi-Metric Evaluation: The method's sustainability is quantified using several tools:

- Analytical Greenness (AGREE) Calculator: Uses a pictogram with 12 segments to provide a comprehensive score [22] [23].

- Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS): Calculates scores based on solvent energy, solvent EHS (Environmental, Health, Safety), and instrument energy consumption [11].

- Analytical Eco-Scale: Assigns penalty points; a score >75 is considered excellent green analysis [22] [23].

- White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB Model: Assesses the method's environmental (Green), practical/economic (Red), and quality (Blue) aspects [22].

- Multi-Metric Evaluation: The method's sustainability is quantified using several tools:

Diagram: Interplay of Industry Drivers in Advancing Green Analytical Chemistry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Green Method Development

Table 3: Key Tools and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry Research

| Item | Category | Function in Green Assessment/Development |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE Calculator [22] [23] | Software/Tool | Provides a comprehensive, semi-quantitative greenness score based on 12 principles of GAC. Essential for standardized environmental impact reporting. |

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) [11] | Software/Tool | Industry-developed metric focusing on solvent energy, solvent EHS, and instrument energy for chromatography. Crucial for internal benchmarking and process improvement. |

| Green Solvents Selecting Tool (GSST) [22] | Software/Database | Guides the replacement of hazardous solvents (e.g., acetonitrile) with environmentally benign alternatives (e.g., ethanol, supercritical CO2). |

| Ethanol | Green Solvent | A common, renewable, and less toxic alternative to acetonitrile in reversed-phase HPLC, reducing method toxicity and environmental footprint [22]. |

| Quality-by-Design (QbD) Software | Development Framework | Enables systematic method development with fewer experiments, reducing solvent and material waste during optimization [22]. |

| UPLC/HPLC System with MS/MS | Instrumentation | Provides high sensitivity and selectivity, allowing for methods that may use smaller sample sizes and less solvent, contributing to green principles [23]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [23] | Assessment Metric | A simple penalty-points system ideal for quick comparative greenness evaluation of published or developed methods. |

| White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) RGB Model [22] | Assessment Framework | Evaluates the balance between method greenness (environmental), practicality (economic), and analytical quality, ensuring sustainable methods are also robust and feasible. |

A Practical Guide to Major Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of analytical methods while maintaining analytical performance [8]. The field has progressed from foundational concepts to sophisticated assessment frameworks that enable researchers to quantify and compare the environmental impact of their methodologies. This evolution reflects a growing commitment within the scientific community to align analytical practices with broader sustainability goals, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where regulatory requirements must be balanced with ecological responsibility [11].

The drive toward greener analytical methods is not merely theoretical; it addresses tangible environmental concerns. A case study on rosuvastatin calcium manufacturing reveals that approximately 25 liquid chromatography analyses are performed per batch, consuming about 18 L of mobile phase per batch and totaling 18,000 L annually for global production of a single active pharmaceutical ingredient [11]. This scale of consumption underscores the critical need for effective greenness assessment tools that can guide method development toward more sustainable practices.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of seven established greenness assessment tools: the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Analytical Eco-Scale, Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), Analytical Greenness (AGREE), Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), AGREEprep, and Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods (GEMAM). Each tool offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different applications within analytical chemistry.

Comparative Analysis of Greenness Assessment Tools

Tool Descriptions and Key Characteristics

Table 1: Overview of Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Year Introduced | Assessment Scope | Scoring System | Visual Output | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Early 2000s | Analytical method | Binary (pass/fail) for 4 criteria | Quadrant pictogram | General analytical methods |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 2012 | Entire analytical procedure | Penalty points subtracted from 100 | Numerical score | General analytical methods |

| GAPI | 2018 | Entire analytical process | Qualitative (green/yellow/red) | 5-part pentagram | Detailed process evaluation |

| AGREE | 2020 | Entire analytical method | 0-1 scale based on 12 GAC principles | Circular pictogram | Comprehensive method comparison |

| AMGS | Not specified | Chromatographic methods | Holistic score incorporating multiple dimensions | Numerical score | Pharmaceutical chromatography |

| AGREEprep | 2022 | Sample preparation | 0-1 scale based on 10 GSP principles | Circular pictogram | Sample preparation evaluation |

| GEMAM | 2025 | Entire analytical assay | 0-10 scale based on 21 criteria | 7-hexagon pictogram | Comprehensive method assessment |

Technical Specifications and Scoring Methodologies

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Greenness Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Assessment Criteria | Calculation Method | Weighting System | Software Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | 4 criteria: PBT, hazardous, corrosive, waste volume | Binary assessment | Not applicable | No software |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Reagents, energy, waste | Penalty points subtracted from base 100 | Fixed penalties | Manual calculation |

| GAPI | 5 stages from sampling to waste | Color-coded assessment | Equal weighting | No software |

| AGREE | 12 principles of GAC | Score calculation with input percentages | User-adjustable | Online calculator |

| AMGS | Solvent energy, EHS, instrument energy | Holistic algorithm | Predefined | Industry tool |

| AGREEprep | 10 principles of GSP | Weighted criteria scoring | User-adjustable | Open-source software |

| GEMAM | 21 criteria across 6 sections | Weighted sum with adjustable weights | User-adjustable | Freely available software |

The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) was among the first tools developed for greenness assessment, featuring a simple pictogram with four quadrants that indicate whether a method meets basic criteria for avoiding persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic chemicals; hazardous substances; corrosives; and excessive waste [8]. While user-friendly, its binary structure provides limited differentiation between methods and doesn't cover the full analytical workflow [8].

The Analytical Eco-Scale offers a semi-quantitative approach that assigns penalty points to parameters that deviate from ideal green conditions [11]. The final score is calculated by subtracting penalty points from a base of 100, with higher scores indicating greener methods. This tool provides clearer differentiation between methods than NEMI but still relies on expert judgment for penalty assignment and lacks a visual component [8].

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) expanded assessment scope with a five-part pentagram that color-codes environmental impact across the entire analytical process from sample collection to final determination [11]. Each section is divided into sub-sections that are colored green (low impact), yellow (moderate impact), or red (high impact). This visual representation helps identify specific stages needing improvement, though it doesn't provide an overall numerical score for direct comparison [8].

Analytical Greenness (AGREE) represents a significant advancement with its comprehensive approach based on all 12 principles of GAC [8]. It generates both a visual output (circular pictogram with 12 sections) and a numerical score between 0 and 1, facilitating direct method comparisons. The tool allows user-adjustable weighting of different principles but involves some subjectivity in scoring [11].

The Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) was developed specifically for chromatographic methods in the pharmaceutical industry [11]. It incorporates unique dimensions including energy consumed in solvent production and disposal, safety/toxicity profiles, and instrument energy consumption during operation. This industry-focused approach provides practical sustainability metrics for pharmaceutical development.

AGREEprep is the first metric dedicated specifically to sample preparation, evaluating this critical stage against 10 principles of green sample preparation (GSP) [25]. Since sample preparation often involves substantial solvent use, energy consumption, and hazardous reagents, this focused tool addresses a significant gap in greenness assessment [26]. It provides both visual and quantitative outputs through user-friendly software.

The Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods (GEMAM) is one of the most recent and comprehensive tools, incorporating both the 12 principles of GAC and 10 factors of green sample preparation [9] [27]. It evaluates six key dimensions (sample, reagent, instrumentation, method, waste, and operator) through 21 specific criteria, with results presented on a 0-10 scale via a seven-hexagon pictogram [9]. The tool allows adjustable weighting of different sections and criteria based on their environmental and health impacts.

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Standardized Assessment Methodology

To ensure consistent and comparable greenness evaluations across different methods and laboratories, the following standardized protocol is recommended:

Data Collection Phase: Compile complete methodological details including sample collection procedures, sample preparation techniques, reagent types and volumes, instrumentation specifications, energy consumption metrics, waste generation quantities, and operator safety considerations [9] [25]. This comprehensive data collection is essential for accurate assessment across all tools.

Tool Selection Procedure: Based on the method characteristics and assessment goals, select appropriate tools. For holistic method evaluation, AGREE, GAPI, or GEMAM are recommended. For focused sample preparation assessment, AGREEprep is ideal. For pharmaceutical chromatography methods, AMGS provides industry-specific insights [11].

Scoring Implementation: Follow tool-specific guidelines for assigning scores or penalty points to each criterion. For tools with software implementations (AGREE, AGREEprep, GEMAM), input the collected data systematically. For manual tools (Eco-Scale, GAPI), apply scoring rules consistently across all method components [9] [25].

Validation and Comparison: Where possible, apply multiple assessment tools to the same method to gain complementary perspectives on its environmental performance. Compare scores against established benchmarks or previously assessed methods to contextualize the results [28].

Interpretation and Reporting: Document both numerical scores and visual outputs for comprehensive reporting. Identify specific areas of poor environmental performance to target for method improvement [8].

Case Study Application

A recent evaluation of standard methods from CEN, ISO, and pharmacopoeias using AGREEprep revealed generally poor greenness performance, with 67% of methods scoring below 0.2 on the 0-1 scale [28]. Methods for environmental analysis of organic compounds showed particularly low scores, with 86% falling in this poor performance category [28]. This assessment highlights the urgent need to update traditional standard methods with more contemporary, sustainable approaches.

Another case study assessing a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method using multiple metrics (MoGAPI, AGREE, AGSA, CaFRI) demonstrated how complementary tools provide a multidimensional sustainability perspective [8]. The method showed strengths in miniaturization and avoidance of derivatization but weaknesses in waste management and reagent safety, illustrating how comprehensive assessment identifies specific improvement areas [8].

Visual Guide to Green Metric Relationships

The evolution of greenness assessment tools follows two primary pathways: specialization and integration. The specialization path (yellow dashed arrows) represents the development of tools focused on specific analytical phases, such as AGREEprep for sample preparation [25] or AMGS for chromatographic methods [11]. The integration path (red dashed arrows) shows the combination of multiple assessment approaches into comprehensive frameworks like GEMAM, which incorporates both GAC principles and GSP factors [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Assessment

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Greenness Assessment Implementation

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Greenness Assessment | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Software | GEMAM Software, AGREE Calculator, AGREEprep Tool | Automated score calculation and visualization | Free download or online access |

| Solvent Databases | CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide, NFPA Toxicity Ratings | Evaluation of reagent greenness based on safety and environmental impact | Published guides and online resources |

| Energy Calculators | Instrument power consumption specs, carbon footprint converters | Quantification of energy use and climate impact | Manufacturer specifications and environmental tools |

| Waste Classification Guides | Hazardous waste categories, disposal requirement charts | Assessment of waste generation and management practices | Regulatory agency publications |

| Reference Standards | Published method assessments, benchmark scores | Comparison and validation of assessment results | Scientific literature and method databases |

The implementation of effective greenness assessment requires both computational tools and reference materials. Software implementations such as the freely available GEMAM software (https://gitee.com/xtDLUT/Gemam/releases/tag/Gemam-v1) enable practical application of complex assessment algorithms [9]. Solvent databases and classification systems provide essential data for evaluating reagent-related criteria across multiple tools. Energy consumption metrics, often available from instrument manufacturers, support the assessment of operational efficiency and carbon footprint. Together, these resources form a complete toolkit for comprehensive greenness evaluation.

The development of greenness assessment tools represents significant progress in aligning analytical chemistry with sustainability principles. From the simple binary evaluation of NEMI to the comprehensive, multi-criteria approach of GEMAM, these tools provide increasingly sophisticated means to quantify and improve the environmental performance of analytical methods. Current evidence suggests that traditional standard methods generally perform poorly on greenness metrics, highlighting an urgent need for method modernization [28]. The complementary application of multiple assessment tools offers the most complete perspective on method sustainability, enabling researchers to make informed decisions that balance analytical performance with environmental responsibility. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of greenness assessment into method development and validation processes will be essential for advancing sustainable analytical practice.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Greenness Assessment Metrics

- The AGREE Calculator: A Detailed Overview

- Experimental Protocol for Applying AGREE

- Comparative Analysis with Other Green Metrics

- Case Study: AGREE in Action

- Integrated Frameworks: Beyond a Single Score

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become a cornerstone of modern analytical method development, aiming to minimize the environmental impact of analytical procedures. The evolution of GAC has been supported by the creation of various assessment metrics, which have progressed from basic tools to comprehensive, multi-criteria frameworks [8]. Foundational tools like the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) offered a simple, binary pictogram but lacked the granularity to distinguish between degrees of greenness [8]. The Analytical Eco-Scale introduced a quantitative score by assigning penalty points for non-green attributes, though it relied on expert judgment and lacked a visual component [8]. The field advanced significantly with the development of the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), which provided a detailed, color-coded pictogram for the entire analytical workflow [17] [8]. The AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric represents a major step forward by combining a unified circular pictogram with a comprehensive numerical score based on all 12 principles of GAC [8].

AGREE is a widely adopted metric that translates the 12 principles of GAC into a practical evaluation tool. Its strength lies in its holistic approach and user-friendly output.

- Scoring System: The tool evaluates an analytical method against the 12 principles of GAC. Each principle is scored, and the results are integrated into a final comprehensive score ranging from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates a greener method [8].

- Visual Output: The score is presented within a circular pictogram. The circle is divided into 12 segments, each corresponding to one principle of GAC. The segments are colored on a gradient from red (score of 0) to green (score of 1), providing an immediate visual summary of the method's performance across all criteria [8].

- Accessibility: AGREE is available as user-friendly, open-source software, which simplifies the calculation process and ensures standardized, reproducible assessments [8].

Experimental Protocol for Applying AGREE

Applying the AGREE calculator requires a systematic gathering of data from the analytical method protocol. The following workflow outlines the steps for a comprehensive assessment.

Step 1: Data Collection Gather all quantitative and qualitative data related to the analytical procedure. Essential information includes:

- Reagents and Solvents: Type, quantity, and hazard classifications (e.g., GHS pictograms) for all chemicals used [8].

- Energy Consumption: The power requirements of instruments (e.g., in kWh per sample) and any special energy demands (e.g., high-temperature operations) [25].

- Waste Generation: The total volume of waste produced per sample and any information on waste treatment or recycling [8].

- Operator Safety: Direct hazards to the operator, such as the use of corrosive substances, volatile vapors, or the need for specialized personal protective equipment [8].

- Method Efficiency: Analytical throughput (samples per hour), degree of automation, and if the method is direct or requires derivatization [8].

Step 2: Data Input Enter the collected data into the dedicated AGREE software. The software typically features a form or a series of fields corresponding to the 12 GAC principles.

Step 3: Score and Pictogram Generation The software automatically calculates the scores for each principle and generates the final overall score and the circular pictogram.

Step 4: Result Interpretation Analyze the output to identify areas of strength and weakness. Red or yellow segments in the pictogram clearly indicate which principles the method performs poorly on, guiding efforts for future optimization.

Comparative Analysis with Other Green Metrics

While AGREE is a powerful tool, it is one of several metrics available. The table below summarizes its key features against other common green assessment tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Score Range | Visual Output | Key Focus | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [8] | 0 to 1 | Circular pictogram (12 segments) | Entire analytical method | Comprehensive, based on 12 GAC principles, user-friendly software. | Does not fully account for pre-analytical processes (e.g., reagent synthesis). |

| NEMI [8] | Binary (Pass/Fail) | Quadrant pictogram | Basic environmental criteria | Extreme simplicity and accessibility. | Lacks granularity; cannot differentiate between moderately and very green methods. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [8] | 0 to 100 (100=ideal) | Numerical score only | Penalty points for non-green practices | Quantitative result, facilitates direct comparison. | Relies on expert judgment; lacks a visual pictogram. |

| GAPI [17] [8] | N/A | Multi-step pictogram (5 parts) | Entire analytical process | More detailed than NEMI; visualizes impact at each stage. | No single cumulative score; some subjectivity in color assignment. |

| AGREEprep [25] | 0 to 1 | Circular pictogram (10 segments) | Sample preparation only | First dedicated tool for sample prep, which is often the least green step. | Must be used with another metric for a full method assessment. |