Inductive and Resonance Effects: Electronic Control for Drug Design and Advanced Materials

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of inductive and resonance effects, fundamental electronic phenomena governing molecular behavior.

Inductive and Resonance Effects: Electronic Control for Drug Design and Advanced Materials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of inductive and resonance effects, fundamental electronic phenomena governing molecular behavior. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational theory with cutting-edge applications. We examine the quantitative assessment of these effects on acidity, basicity, and reactivity, detail their strategic application in optimizing drug molecules and functional materials, address contemporary challenges and misconceptions highlighted by recent research, and present advanced validation methodologies. The synthesis of foundational knowledge with current scientific debates offers a practical framework for leveraging electronic effects in rational molecular design for biomedical and clinical advancement.

Core Principles and Modern Re-evaluation of Electronic Effects

Within the broader thesis on electronic effects in organic molecules, understanding the fundamental mechanisms of inductive and resonance effects is paramount for predicting molecular behavior, reactivity, and physical properties. These electronic effects form the bedrock of rational molecular design in fields ranging from medicinal chemistry to materials science. The inductive effect describes the polarization of σ-bonds through a molecule due to electronegativity differences, while the resonance effect involves the delocalization of π-electrons or lone pairs across a conjugated system [1]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core concepts, framing them within contemporary research contexts and providing the methodological tools for their investigation.

Core Mechanisms and Theoretical Foundations

The Inductive Effect: A Sigma-Bond Phenomenon

The inductive effect is a permanent electronic phenomenon that occurs through σ-bonds in a molecule. It is initiated by the electronegativity difference between two bonded atoms, leading to a displacement of the bonding electron density toward the more electronegative atom [2] [1]. This polarization creates a permanent dipole moment, with partial positive (δ⁺) and partial negative (δ⁻) charges on the adjacent atoms.

This electron shift transmits through the carbon chain via successive polarization of σ-bonds, but its influence diminishes rapidly with increasing distance from the source substituent, typically becoming negligible beyond three carbon atoms [1]. The effect is classified as either +I effect (electron-donating) or –I effect (electron-withdrawing), with common examples summarized in Table 1.

The Resonance Effect: A Pi-Bond Delocalization

The resonance effect, also known as the mesomeric effect, involves the delocalization of π-electrons or lone pairs within conjugated systems [3] [1]. Unlike the inductive effect, resonance requires an interconnected system of p-orbitals, typically found in alternating single and double bonds, or atoms with lone pairs adjacent to π-systems.

This delocalization results in multiple valid Lewis structures, known as resonance structures or canonical forms, which collectively represent the true electronic structure of the molecule as a resonance hybrid [4] [5]. The resonance effect provides significant stabilization to molecules, often exceeding that provided by inductive effects, and can extend across the entire conjugated system without significant attenuation with distance [1]. Similar to inductive effects, resonance can be classified as +R effect (electron-donating) or –R effect (electron-withdrawing).

Table 1: Classification of Common Inductive and Resonance Effects

| Group | Inductive Effect | Resonance Effect | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkyl (e.g., -CH₃) | +I (Electron-Donating) [2] | Minimal | Carbocation stabilization [3] |

| Halogen (e.g., -Cl) | -I (Electron-Withdrawing) [2] | +R (Electron-Donating) [6] | Aromatic substitution directing |

| Nitro (-NO₂) | -I (Electron-Withdrawing) [1] | -R (Electron-Withdrawing) [1] | Acidity enhancement [3] |

| Methoxy (-OCH₃) | -I (Electron-Withdrawing) [3] | +R (Electron-Donating) [3] | Phenol acidity reduction |

| Hydroxyl (-OH) | -I (Electron-Withdrawing) | +R (Electron-Donating) [3] | Phenoxide stabilization |

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiators

A clear understanding of the distinctions between inductive and resonance effects is crucial for accurate prediction of molecular properties and reaction outcomes. These differences originate from their fundamental operating mechanisms and manifest in their scope, magnitude, and distance dependence.

Table 2: Fundamental Differences Between Inductive and Resonance Effects

| Criterion | Inductive Effect | Resonance Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Origin of Effect | σ-bond polarization [1] | π-electron/lone pair delocalization [1] |

| Bond Involvement | Sigma (σ) bonds only [1] | Pi (π) bonds and lone pairs [1] |

| Scope of Operation | All covalent bonds [1] | Requires conjugated systems [1] |

| Distance Dependence | Decreases rapidly with distance [1] | Extends across entire conjugated system [1] |

| Symbols Used | +I (donating), -I (withdrawing) [1] | +R (donating), -R (withdrawing) [1] |

| Relative Magnitude | Generally weaker, local effect [1] | Generally stronger, provides major stabilization [1] |

| Representative Example | Chlorine in alkyl chlorides [1] | π-system in benzene [5] [1] |

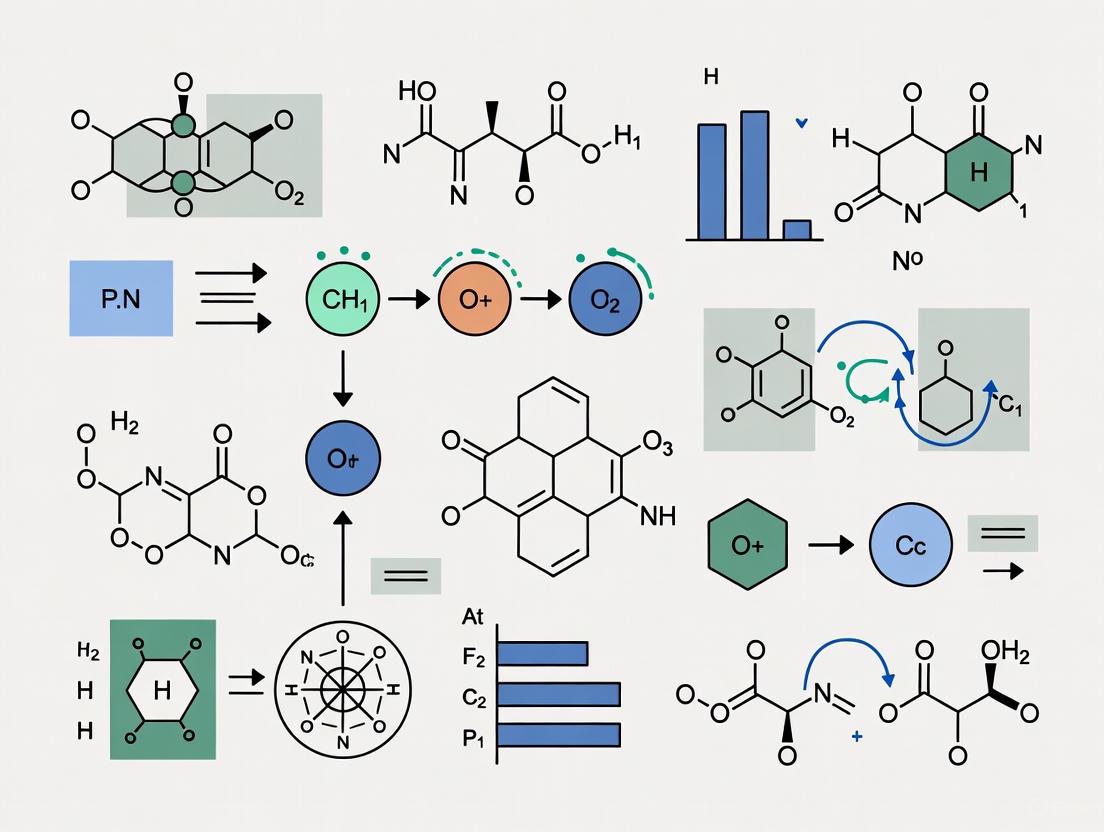

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational differences between these two electronic effects:

Impact on Molecular Properties and Reactivity

Acidity and Basicity Trends

Both inductive and resonance effects profoundly influence the acidity and basicity of organic compounds by stabilizing or destabilizing the charged species formed upon proton transfer.

Inductive Effect on Acidity: Electron-withdrawing groups (-I effect) increase acidity by stabilizing the conjugate base through σ-bond withdrawal of electron density. For example, in halogenated carboxylic acids, the electron-withdrawing effect of halogens stabilizes the carboxylate anion, making fluoroacetic acid (pKa = 2.59) significantly stronger than acetic acid (pKa = 4.76) [3]. This effect is distance-dependent, with α-substituents exerting the strongest influence.

Resonance Effect on Acidity: Resonance can dramatically enhance acidity when the conjugate base is stabilized by delocalization. Carboxylic acids are considerably more acidic than alcohols because the negative charge in the carboxylate ion is delocalized over two oxygen atoms [3]. Similarly, phenols (pKa ≈ 10) are more acidic than aliphatic alcohols (pKa ≈ 16-18) due to resonance stabilization of the phenoxide ion across the aromatic ring [5].

Competing Effects: When both effects operate simultaneously, resonance generally dominates. For instance, p-methoxyphenol (pKa = 10.26) is less acidic than phenol (pKa = 9.99) despite the methoxy group's -I effect, because its stronger +R effect donates additional electron density to the system, destabilizing the phenoxide ion [3].

Reaction Intermediate Stabilization

Electronic effects critically influence the stability of reactive intermediates, thereby determining reaction pathways and rates.

Carbocation Stability: Alkyl groups stabilize carbocations through their +I effect, donating electron density to the electron-deficient center [3]. This explains the stability trend: tertiary > secondary > primary > methyl carbocations. Hyperconjugation, which involves overlap between adjacent σ-bonds and the empty p-orbital, provides additional stabilization [3].

Aromatic Substitution: In electrophilic aromatic substitution, electron-donating groups (EDGs) with +I or +R effects activate the ring and direct incoming electrophiles to ortho/para positions [5]. Conversely, electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) with -I or -R effects deactivate the ring and typically direct meta, with halogens being a notable exception due to their opposing -I and +R effects [5].

Contemporary Research Context

Revisiting Fundamental Concepts

Recent research has challenged traditional understandings of electronic effects. A 2025 study by Elliott et al. employing Hirshfeld charge analysis found no significant difference in the inductive effects of different alkyl groups (t-Bu > i-Pr > Et > Me) in neutral organic molecules [7]. This contradicts long-standing textbook presentations and suggests that previously observed trends in alcohol acidity are primarily due to solvent effects and polarizability rather than inherent inductive differences [7].

Application in Energy Conversion Technologies

Current research explores these electronic effects in developing advanced energy conversion technologies. Studies on proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions in hydroquinone derivatives reveal that the resonance effect (+R) is the main driving force behind promoting concerted two-proton-coupled electron transfer (2PCET) with superoxide radical anions [6]. This has significant implications for designing efficient biomimetic quinone redox systems for catalytic energy conversion [6].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Computational Analysis Protocols

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations for Charge Distribution Analysis

- Objective: To determine electron density distribution and quantify inductive/resonance effects [7] [6].

- Methodology:

- Employ DFT calculations with functionals such as PBEh1PBE and basis sets like aug-cc-pVTZ [7].

- Perform geometry optimization to locate energy minima.

- Conduct population analysis using Hirshfeld, CM5, NBO, or QTAIM methods to calculate atomic charges [7].

- Compare charge distributions across molecular series to isolate electronic effects.

- Applications: Validating substituent effects, quantifying electron donation/withdrawal, and analyzing resonance stabilization in conjugated systems [7].

Electrochemical and DFT Analysis of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer

- Objective: To investigate substituent effects on concerted PCET mechanisms [6].

- Methodology:

- Perform cyclic voltammetry of substituted hydroquinones in aprotic solvents (e.g., DMF) [6].

- Generate superoxide radical anion electrochemically.

- Monitor scavenging kinetics through voltammetric measurements.

- Correlate electrochemical data with DFT-calculated parameters (reaction energies, orbital properties) [6].

- Apply Hammett or Yukawa-Tsuno equations to quantify I and R contributions [6].

- Applications: Designing efficient electron transfer catalysts and understanding bioenergetic processes [6].

Spectroscopic and Physical Property Analysis

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

- Objective: To experimentally assess electron density distribution [7].

- Methodology:

- Measure ¹³C NMR chemical shifts of strategically positioned nuclei.

- Correlate deshielding (downfield shifts) with decreased electron density.

- Compare trends across molecular series with different substituents.

- Interpretation: While ¹³C NMR provides useful data, recent studies suggest calculated Hirshfeld charges may offer more reliable indicators of charge distribution for quantifying inductive effects [7].

Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational and Visualization Resources

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09 [7] | Computational Software | Quantum chemical calculations | Electronic structure calculation, charge distribution analysis |

| Avogadro [8] | Molecular Graphics | 3D molecule construction and visualization | Molecular model building, orbital visualization, basic property prediction |

| IQmol [8] | Molecular Graphics | 3D molecular visualization and analysis | Orbital and electron density mapping, spectroscopy visualization |

| PULSEE [9] | Simulation Software | Magnetic resonance simulation | NMR/NQR spectral simulation for structural analysis |

The experimental workflow for investigating electronic effects typically follows a systematic approach from molecular design to data interpretation, as shown in the following diagram:

Inductive and resonance effects represent fundamental electronic phenomena that govern molecular behavior across chemical disciplines. While the inductive effect operates through σ-bonds with limited spatial influence, the resonance effect delocalizes electrons through π-systems, providing substantial stabilization. Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of these effects, revealing greater complexity than traditional textbook descriptions. The integration of computational and experimental methodologies provides powerful tools for quantifying these effects and applying them to challenges in drug development, materials science, and energy technologies. As research advances, particularly in understanding coupled proton-electron transfer processes, these classic concepts continue to find new relevance in cutting-edge scientific applications.

The Hammett equation stands as a cornerstone of physical organic chemistry, providing a powerful quantitative framework for understanding how electronic effects influence chemical reactivity and equilibrium. Developed by Louis Plack Hammett in 1937, it formalizes the intuitive concept that substituents on an aromatic ring can systematically alter the free energy of reaction transitions states and intermediates [10]. This guide frames the Hammett equation within broader research on the inductive effect and resonance in organic molecules, detailing how these separate electronic influences can be disentangled, quantified, and applied in modern scientific research, including drug development.

The Hammett equation is a linear free-energy relationship (LFER). Its most common forms are used to correlate equilibrium constants or reaction rates for meta- and para-substituted benzoic acid derivatives [10]:

For equilibria: log((\frac{K}{K_0})) = σρ

For reaction rates: log((\frac{k}{k_0})) = σρ

Here, (K) and (k) are the equilibrium constant and rate constant for a substituted compound, while (K0) and (k0) are the corresponding values for the unsubstituted reference compound (benzoic acid for equilibria). The two key parameters are σ (sigma), the substituent constant, which quantifies the substituent's electronic character, and ρ (rho), the reaction constant, which describes the sensitivity of a given reaction or equilibrium to these electronic perturbations [10].

The fundamental electronic effects quantified by the Hammett equation are the Inductive Effect and the Resonance (Mesomeric) Effect.

- The Inductive Effect is an electronic influence transmitted through σ bonds via polarization of bonding electrons. Electron-withdrawing groups (-I) stabilize anions by dispersing negative charge, while electron-donating groups (+I) stabilize cations [3].

- The Resonance (Mesomeric) Effect operates through π bonds, allowing for electron donation (+M) or withdrawal (-M) via orbital overlap and delocalization. This effect is generally more dominant than the inductive effect over longer distances and can lead to significant stabilization, as seen in the conjugate base of carboxylic acids compared to alcohols [3].

Quantitative Data: Substituent and Reaction Constants

Substituent Constants (σ)

Substituent constants are empirically determined. The baseline is set by the ionization of benzoic acid in water at 25°C, for which the reaction constant ρ is defined as 1.0. A substituent's σ value is then calculated from the equilibrium constant of the corresponding meta- or para-substituted benzoic acid [10]. The values reveal the interplay of inductive and resonance effects.

Table 1: Selected Hammett Substituent Constants

| Substituent | σ_meta | σ_para | Primary Electronic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitro (NO₂) | +0.710 | +0.778 | Strong -I, -M |

| Cyano (CN) | +0.56 | +0.66 | Strong -I, -M |

| Trifluoromethyl (CF₃) | +0.43 | +0.54 | Strong -I |

| Chloro (Cl) | +0.373 | +0.227 | -I, +M (weaker) |

| Fluoro (F) | +0.337 | +0.062 | -I, +M (stronger) |

| Hydrogen (H) | 0.000 | 0.000 | Reference |

| Methyl (CH₃) | -0.069 | -0.170 | +I |

| Methoxy (OCH₃) | +0.115 | -0.268 | -I, Strong +M |

| Hydroxy (OH) | +0.12 | -0.37 | -I, Strong +M |

| Amino (NH₂) | -0.161 | -0.66 | -I, Very Strong +M |

Data compiled from [10]

Electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs) feature positive σ values, increasing the acidity of benzoic acid by stabilizing the carboxylate anion. Strong EWGs like nitro and cyano exhibit significant positive σ values for both meta and para positions due to combined -I and -M effects [10]. Halogens have positive σ values, but their meta constants are larger than their para constants because the inductive withdrawal (-I) dominates at the meta position, while at the para position, it is partially counteracted by a mesomeric electron-donating effect (+M) [10] [3].

Electron-donating groups (EDGs) have negative σ values. Alkyl groups like methyl exhibit a weak +I effect [10]. Groups with lone pairs, like methoxy and amino, are strong EDGs at the para position due to powerful +M resonance, where a lone pair is delocalized into the ring. This dominant +M effect overcomes their inherent inductive withdrawal (-I), resulting in a negative σ_para [10] [3].

Modified Substituent Constants

The standard σ scale has limitations when the reaction center can engage in direct resonance with the substituent. For these cases, modified constants are used [10]:

- σp⁻ Constants: Used when the reaction center is electron-rich (e.g., phenoxide oxygen in phenols) and can conjugate with -M substituents in the para position. These constants are derived from the ionization of para-substituted phenols.

- σp⁺ Constants: Used when the reaction center is electron-deficient (e.g., a carbocation) and can conjugate with +M substituents in the para position. These constants are derived from the solvolysis rates of para-substituted cumyl chlorides.

Reaction Constants (ρ)

The reaction constant ρ measures the sensitivity of a reaction series to substituent effects. It is obtained from the slope of a Hammett plot (log(k/k₀) vs. σ) [10].

Table 2: Reaction Constants (ρ) for Selected Processes

| Reaction | ρ Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Ionization of benzoic acids (standard) | +1.000 | Reference: Builds negative charge |

| Ionization of phenols | +2.008 | Highly sensitive to substituents; builds negative charge |

| Alkaline hydrolysis of ethyl benzoates | +2.498 | Highly sensitive; builds negative charge at carbonyl |

| Hydrolysis of substituted cinnamic esters | +1.267 | Builds negative charge |

| Bromination of acetophenones | +0.417 | Builds some negative charge |

| Acid-catalyzed esterification of benzoic esters | -0.085 | Very low sensitivity; slight build of positive charge |

| Hydrolysis of benzyl chlorides (SN1) | -1.875 | Builds positive charge |

Data from [10]

The sign and magnitude of ρ provide mechanistic insight [10]:

- A positive ρ value indicates that electron-withdrawing groups (positive σ) accelerate the reaction or favor the products for an equilibrium. This signifies a build-up of negative charge in the transition state or product.

- A negative ρ value indicates that electron-donating groups (negative σ) facilitate the reaction, suggesting a build-up of positive charge.

- The magnitude of ρ indicates the degree of charge development at the transition state relative to the ground state. A large |ρ| signifies a high sensitivity to substituent effects.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the general workflow for determining substituent constants (σ) and reaction constants (ρ) using the Hammett equation, connecting the experimental steps with the underlying theoretical relationships.

Detailed Methodology: Determining a Substituent Constant (σ)

This protocol details the process for determining the σ constant for a new para-substituent, using the ionization of benzoic acids as the benchmark equilibrium [10].

Objective: To determine the substituent constant (σₓ) for a para-substituent (X) on a benzene ring.

Principle: The ionization constant (Kₐ) of the para-substituted benzoic acid (4-X-C₆H₄-COOH) is measured and compared to that of unsubstituted benzoic acid (K₀). Using the Hammett equation with ρ = 1.000 for this reference reaction, σₓ is calculated as log(Kₓ/K₀).

Materials:

- High-purity sample of 4-X-benzoic acid

- High-purity unsubstituted benzoic acid (reference)

- Potentiometric titrator or pH meter (calibrated with standard buffers)

- CO₂-free deionized water

- Standardized sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution (e.g., 0.05 M)

- Thermostatted water bath or jacketed vessel (25.0 ± 0.1 °C)

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh (~0.005 mol) of the 4-X-benzoic acid and dissolve it in CO₂-free deionized water to make a known volume (e.g., 250.0 mL).

- Titration: Place a known aliquot (e.g., 50.00 mL) of the acid solution in a thermostatted vessel at 25.0 °C. Under a nitrogen atmosphere to exclude CO₂, titrate with standardized NaOH solution.

- Data Recording: Record the pH after each small addition of titrant. Ensure sufficient data points are collected, especially in the region around the half-equivalence point and the equivalence point.

- Repeat: Perform the titration in triplicate for both the substituted acid and the unsubstituted benzoic acid reference.

Data Analysis:

- Determine pKₐ: For each titration, plot pH vs. volume of NaOH. The pKₐ is equal to the pH at the volume corresponding to the half-equivalence point.

- Calculate Kₐ: The acid dissociation constant is Kₐ = 10^(-pKₐ).

- Average Kₐ: Calculate the mean Kₐ value from the replicates for both the substituted (Kₓ) and unsubstituted (K₀) acids.

- Calculate σₓ: Apply the Hammett equation. σₓ = log(Kₓ / K₀)

Validation: The derived σₓ value should be consistent when applied to other reaction series with known ρ values.

Detailed Methodology: Determining a Reaction Constant (ρ)

This protocol describes how to determine the reaction constant for a new reaction, such as the alkaline hydrolysis of ethyl benzoate derivatives [10].

Objective: To determine the reaction constant (ρ) for the alkaline hydrolysis of meta- and para-substituted ethyl benzoates.

Principle: The reaction rate constant (k) for each substituted ester is measured and compared to that of the unsubstituted ethyl benzoate (k₀). A plot of log(k/k₀) vs. the known σ values for the substituents yields a straight line with a slope of ρ.

Materials:

- Series of meta- and para-substituted ethyl benzoates

- Standardized sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution in a water-ethanol mixture (e.g., 60% v/v)

- Thermostatted reaction vessel (30.0 ± 0.1 °C)

- Automatic titrator or HPLC system for reaction monitoring

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a solution of the substituted ethyl benzoate in the ethanol-water solvent and bring it to 30.0 °C in a thermostatted bath.

- Initiation and Monitoring: Rapidly add a known volume of standardized NaOH solution to start the reaction. The initial concentration of ester and base should be known precisely.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Monitor the reaction progress. This can be done by:

- Continuous Titration: Using an automatic titrator to maintain a constant pH by adding acid, with the rate of acid addition being proportional to the reaction rate.

- Aliquot Method: Withdrawing aliquots at timed intervals, quenching the reaction, and analyzing the remaining base by titration or the appearance of product (benzoate) by HPLC.

- Repeat: Conduct the kinetic experiment for each substituted ethyl benzoate and the unsubstituted reference ester.

Data Analysis:

- Determine Rate Constant (k): For each ester, plot the concentration data according to the appropriate integrated rate law for a second-order reaction (or pseudo-first-order if [OH⁻] >> [ester]). Perform a linear regression to obtain the rate constant k.

- Calculate log(k/k₀): For each substituent, calculate log(k/k₀).

- Construct Hammett Plot: Plot log(k/k₀) on the y-axis against the known σ values for each substituent on the x-axis.

- Perform Linear Regression: Fit the data points to a straight line (y = ρx + b). The slope of the best-fit line is the reaction constant ρ. The intercept should be approximately zero.

Visualization of Electronic Effects

Interplay of Inductive and Resonance Effects

The electronic character of a substituent is a composite of its inductive and resonance effects. The diagram below visualizes how these effects operate and interact for representative substituents at the para position.

Mechanism of Resonance Effects in Para-Substituted Phenols

The diagram below illustrates the resonance stabilization in the conjugate base of para-nitrophenol, which is the basis for the σp⁻ parameter set. This demonstrates how a -M group can delocalize charge over a larger system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Hammett Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Analysis | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Benzoic Acid (unsubstituted) | Reference compound for defining σ and ρ scales. | Must be of highest available purity; primary standard. |

| Substituted Benzoic Acids (meta- and para-) | Core substrates for determining substituent constants (σ). | Purity is critical; characterization via NMR, mp is essential. |

| Substituted Ethyl Benzoates | Common substrates for kinetic studies (e.g., hydrolysis to find ρ). | Can be synthesized from corresponding benzoic acids. |

| Standardized NaOH Solution | Titrant for determining acid ionization constants (Kₐ). | Must be standardized against primary acid; protected from CO₂. |

| Deionized, CO₂-Free Water | Solvent for equilibrium and kinetic studies. | Prevents interference from carbonic acid in pKₐ measurements. |

| Potentiometric pH Meter | For accurate measurement of pH during titrations. | Requires calibration with ≥2 NIST-traceable standard buffers. |

| Thermostatted Reaction Vessel | Maintains constant temperature (±0.1 °C) during experiments. | Temperature control is vital for reproducible K and k values. |

| Inert Atmosphere (N₂/Ar) | Excludes atmospheric CO₂ during titration of weak acids. | Prevents formation of carbonic acid which alters pH. |

| HPLC System with UV Detector | Alternative method for monitoring reaction kinetics. | Quantifies concentration of reactants/products over time. |

Modern Applications and Advanced Concepts

The principles of the Hammett equation extend far beyond classical organic chemistry, finding critical applications in modern scientific research. In drug development, Hammett correlations are used in quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) to predict the biological activity of drug candidates by linking the electronic nature of substituents to potency, metabolism, and absorption [10].

In materials science and catalysis, quantifying electronic effects is essential for designing efficient catalysts. A 2025 study on platinum nanoparticles for the water-gas shift reaction demonstrated a threshold where the intrinsic activity of corner platinum sites increased by three orders of magnitude due to an electronic structure effect, independent of geometric factors [11]. This highlights the power of disentangling electronic and geometric contributions to activity, a modern extension of the Hammett philosophy.

The Hammett equation's true power lies in its ability to separate and quantify the intrinsic electronic effect of a substituent (σ) from the susceptibility of a process to that effect (ρ). This foundational framework allows researchers to predict reactivity, deduce reaction mechanisms, and rationally design molecules with tailored electronic properties for applications from pharmaceuticals to nanotechnology.

For decades, organic chemistry education and research have been guided by established dogmas concerning substituent effects and reaction behaviors. Two particularly entrenched concepts are the inductive electron-releasing nature of alkyl groups and the limited synthetic utility of alkyl haloacetates outside traditional nucleophilic substitution. This whitepaper synthesizes recent, compelling experimental and computational evidence that directly challenges these textbook principles. Framed within the ongoing research into the precise dissection of inductive and resonance effects, these findings necessitate a revision of fundamental models used in rational drug design, where accurate prediction of electronic effects is paramount for optimizing potency, selectivity, and metabolic stability [12] [13].

Part 1: The Alkyl Group Inductive Effect – A Computational Reversal

The Established Dogma vs. New Evidence

The conventional teaching asserts that alkyl groups (e.g., -CH₃, -C₂H₅) are inductively electron-releasing (+I effect) when compared to a hydrogen atom. This concept is used to explain trends in carbocation stability, acid strength, and spectroscopic shifts. However, a significant body of computational chemistry analysis now robustly contradicts this position. High-level density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that alkyl groups actually exert a weak inductive electron-withdrawing effect (–I) relative to hydrogen [13].

This reversal is not in conflict with most experimental observations because the inductive effect of simple alkyl groups is small. Its manifestation is often masked by larger, concurrent effects such as hyperconjugation (which is electron-donating), polarizability (especially in charged species), and solvent influences. The revised understanding clarifies that the net electron-donating character of alkyl groups in contexts like carbocation stabilization is primarily due to hyperconjugation, not a positive inductive effect [13].

Quantitative Computational Data

The following table summarizes key computational evidence challenging the classic +I assignment for alkyl groups. Data is derived from analyses of 1,4-disubstituted bicyclo[2.2.2]octane (BCO) systems, which are ideal for isolating inductive effects by eliminating π-conjugation pathways [12] [13].

Table 1: Computational Evidence for the Inductive Electron-Withdrawing Nature of Alkyl Groups

| Computational Descriptor | System Analyzed | Key Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge of Substituent Active Region (cSAR) | 1-X-BCO, 4-X-BCO-1-Y derivatives | Linear relationships between cSAR(X) and cSAR of adjacent CH₂ groups show alkyl groups (X) withdraw electron density from the skeleton. | The slope of the correlation is negative, indicating an electron-withdrawing influence through σ-bonds, consistent with a –I effect [12]. |

| Substituent Effect Stabilization Energy (SESE) | Isodesmic reactions comparing X-R-Y systems | The energetic contribution from pure inductive effects for alkyl groups is consistent with weak electron withdrawal. | When resonance/hyperconjugation is computationally suppressed, the intrinsic σ-withdrawing nature is revealed [12] [13]. |

| Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) | Surfaces of alkanes vs. methane | Analysis of MEP indicates a depletion of electron density along the C-C bond compared to C-H. | Supports the polarization of electron density toward the more electronegative carbon in an C-C bond, contrary to the +I model [12]. |

Conceptual Diagram: The Revised Model of Alkyl Group Effects

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual shift from the textbook model to the evidence-supported model, separating the net stabilizing effect into its constituent components.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Tools for Computational Analysis of Substituent Effects

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (Gaussian, ORCA, etc.) | Performs quantum mechanical calculations to obtain molecular electron densities, energies, and properties. |

| B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) Method | A specific, widely validated level of theory (functional/basis set) for accurate organic molecule calculations [12]. |

| Bicyclo[2.2.2]octane (BCO) Model | A rigid, saturated computational model system used to isolate and study pure inductive (field) effects [12] [13]. |

| Charge Analysis Schemes (NPA, AIM) | Algorithms (Natural Population Analysis, Atoms in Molecules) to assign atomic charges from computed wavefunctions. |

| cSAR & SESE Scripts | Custom scripts to calculate the Charge of the Substituent Active Region and Substituent Effect Stabilization Energy from computational outputs [12]. |

Part 2: Haloacetate Reactivity – Electrochemical Activation for Cyclopropanation

Beyond SN2: Reductive Dimerization to Cyclopropanes

Alkyl 2-haloacetates are classic substrates for SN2 reactions and nucleophilic displacement. Recent electrochemical research unveils a novel and valuable reactivity paradigm: the electrogenerated base-promoted reductive dimerization to form functionalized cyclopropane derivatives [14]. This method provides an environmentally friendly alternative to traditional approaches using stoichiometric metals like lithium.

The reaction proceeds via electro-reduction of the alkyl 2-chloroacetate at the cathode, generating a carbanion intermediate. This anion attacks a second molecule of substrate in a Michael addition-like pathway, followed by intramolecular substitution to form the trisubstituted cyclopropane ring [14].

Experimental Protocol: Electrochemical Cyclopropanation

Detailed Methodology from Optimized Conditions [14]:

- Cell Setup: Use an H-type divided cell equipped with platinum plate electrodes (cathode and anode). The divided cell is essential to prevent re-oxidation of the anionic intermediate.

- Solution Preparation:

- Catholyte: Dissolve the alkyl 2-chloroacetate substrate (0.5 mmol) in 4.0 mL of 0.3 M tetrabutylammonium bromide (Bu4NBr) in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF).

- Anolyte: Add 4.0 mL of 0.3 M Bu4NBr in DMF to the anodic chamber.

- Electrolysis: Perform constant current electrolysis at 12 mA at room temperature. Pass 1.0 F/mol of electricity relative to the substrate.

- Work-up: After electrolysis, combine the contents of the cathodic chamber with water and extract with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Purification: Isolate the cyclopropane product using preparative gel permeation chromatography (GPC) or silica gel column chromatography.

Optimization Data and Substrate Scope

Table 3: Optimization of Electrochemical Cyclopropanation Conditions [14]

| Entry | Variation from Standard Conditions | Yield of Product 2 | Key Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Standard Conditions: Pt electrodes, DMF, Bu4NBr, 12 mA, rt, 1.0 F/mol | 46% | Baseline optimized yield. |

| 4 | DMSO as solvent instead of DMF | <22% | DMF is superior to DMSO. |

| 5 | MeOH as solvent instead of DMF | n.d. | Reaction fails in protic solvent. |

| 6 | Bu4NCl as supporting electrolyte | 35% | Bromide (Br⁻) gives best yield. |

| 14 | Lower current: 6 mA instead of 12 mA | 46% | Yield maintained at lower current. |

| 15 | Control: No electric current applied | n.d. | Reaction is electrochemical. |

Table 4: Scope of Alkyl 2-Haloacetates in Electrochemical Cyclopropanation [14]

| Entry | Substrate (Alkyl 2-Chloroacetate) | Product (Trisubstituted Cyclopropane) | Isolated Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Methyl (3) | Trimethyl cyclopropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate (4) | 28% |

| 2 | Ethyl (5) | Triethyl cyclopropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate (6) | 21% (est.) |

| 8 | Benzyl (15) | Tribenzyl cyclopropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate (16) | 34% |

| 9 | Allyl (17) | Triallyl cyclopropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate (18) | 31% |

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the logical sequence and key decision points in the electrochemical cyclopropanation protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Essentials

Table 5: Key Research Reagents & Equipment for Electrochemical Synthesis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| H-type Divided Electrochemical Cell | Physically separates anodic and cathodic chambers to prevent interference between oxidation and reduction products. |

| Platinum (Pt) Plate Electrodes | Inert electrodes for reduction (cathode) and oxidation (anode) processes. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Bromide (Bu4NBr) | Supporting electrolyte; dissolves in organic solvent (DMF) to conduct current. The Br⁻ ion may play a role in the mechanism. |

| Anhydrous N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Aprotic, polar solvent that stabilizes the anionic intermediates and dissolves organic substrates/electrolytes. |

| Constant Current Power Supply | Provides precise control of the electrical current (mA) passed through the cell. |

| Preparative GPC or Chromatography | Essential for purifying the cyclopropane products from complex reaction mixtures. |

The convergence of computational and experimental evidence presented herein mandates a nuanced update to foundational organic chemistry principles. Recognizing alkyl groups as intrinsically weak σ-electron withdrawers (–I) refines our ability to model electronic effects in drug candidates, leading to more accurate predictions of pKa, binding interactions, and spectroscopic properties [12] [13].

Simultaneously, the electrochemical activation of alkyl haloacetates for cyclopropane synthesis exemplifies how challenging reaction dogma can unlock novel, sustainable synthetic pathways. Cyclopropanes are prized motifs in medicinal chemistry for their ability to constrain conformation, modulate potency, and improve metabolic stability. This electrochemical method offers a direct, metal-free route to these valuable structures from simple precursors [14].

Together, these advances underscore that a deep and accurate understanding of inductive and resonance effects—free from historical oversimplifications—is critical for innovation in pharmaceutical research and development. The tools and protocols detailed provide a roadmap for researchers to further explore and apply these revised paradigms.

The Interplay of Polarizability, Field Effects, and Hyperconjugation

The classical pedagogy of organic chemistry often categorizes alkyl groups as inductively electron-donating (+I) relative to hydrogen. This entrenched view has been used for decades to explain trends in acidity, basicity, and reaction rates. However, contemporary computational and experimental evidence challenges this simplification, revealing a more nuanced picture where polarizability, external field effects, and hyperconjugation are deeply intertwined, often masking the true inductive effect [15] [16]. This whitepaper reframes the electronic character of substituents within a modern thesis on inductive and resonance effects, arguing that the perceived "inductive" trends are frequently manifestations of polarizability and hyperconjugation. For researchers and drug development professionals, accurately dissecting these effects is not merely academic; it is critical for predicting molecular behavior in varying dielectric environments, rationalizing host-guest interactions, and designing molecules with tailored electronic properties [17] [18].

Core Concepts and Their Intersections

The Redefined Inductive Effect

The IUPAC defines the inductive effect as the transmission of charge through a chain of atoms by electrostatic induction [15]. To isolate a 'purely inductive' effect for study, one must restrict analysis to ground-state charge distribution in neutral molecules, thereby excluding the larger contributions from polarizability in charged species or transition states [16]. Computational charge decomposition analyses, such as the Hirshfeld method, have demonstrated that alkyl groups are, in fact, weakly inductively electron-withdrawing (–I) relative to hydrogen, as carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen [16]. Crucially, these studies find no meaningful difference in the inductive effect across a series of alkyl groups (Me, Et, i-Pr, t-Bu) [15] [19]. The long-taught order (t-Bu > i-Pr > Et > Me) is not supported by charge distribution in neutral molecules and likely originated from misinterpreted solvent-dependent acidity trends [15] [19].

Polarizability as a Dominant Force

Polarizability (α) describes how easily an electron cloud is distorted by an external electric field. It is a key factor in stabilizing both positive and negative charges. Larger, more diffuse alkyl groups like t-butyl are more polarizable than methyl groups [15]. This explains why t-butanol is a stronger gas-phase acid and base than methanol—the polarizable t-butyl group better stabilizes the resulting alkoxide or oxonium ion [15] [16]. Polarizability is an environment-dependent, non-additive property, making it essential for modeling interactions in heterogeneous systems like protein binding pockets or lipid membranes [17]. Traditional fixed-charge force fields fail to capture this response, necessitating the development of polarizable force fields like the Drude oscillator model for accurate molecular dynamics simulations [17] [18].

Hyperconjugation: A Delocalization Phenomenon

Hyperconjugation is the stabilizing interaction where electrons in a σ-bond (typically C-H or C-C) delocalize into an adjacent empty or partially filled p-orbital or π-system. It is a primary mechanism for carbocation and radical stabilization. Recent computational work demonstrates a significant overlap between the concepts of hyperconjugation and polarizability [20]. The electron donation via hyperconjugation can be systematically modulated by applying an external electric field, proving that polarization directly affects hyperconjugation interactions [20]. This intersection suggests that what is often qualitatively described as "hyperconjugative stabilization" may be quantitatively inseparable from the molecule's polarizable response to internal or external fields.

External Field Effects

The application of an external electric field represents a powerful tool for probing and manipulating electronic effects. Calculations on molecules like hexane and fluoropentane under an applied field show that field-induced polarization is directly reflected in changes to hyperconjugation interactions [20]. This provides a clear experimental (or computational) protocol to dissect these intertwined effects. Furthermore, spatial confinement, modeled by harmonic oscillator potentials, can significantly alter molecular polarizability, as demonstrated in studies on H₂ bond dissociation [21] [22].

Data Presentation: Computational Evidence

Table 1: Summary of Key Computational Findings on Alkyl Group Electronic Effects

| Study Focus | Method | Key Finding | Implication | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inductive Effect of R Groups | DFT (PBEh1PBE/aug-cc-pVTZ), Hirshfeld Charges | Alkyl groups (Me, Et, i-Pr, t-Bu) are inductively electron-withdrawing (–I) vs. H. No significant trend among different alkyl groups. | Challenges textbook +I order. Isolated inductive effect is small and consistent. | [15] [19] [16] |

| Charge Stabilization | Gas-Phase Acidity/Basicity Calculations | t-BuOH more acidic & basic than MeOH in gas phase. | Trend due to polarizability, not inductive effect. Polarizability stabilizes both +ve and -ve charge. | [15] [16] |

| Hyperconjugation & Polarizability Link | NBO Analysis under Applied Field | Hyperconjugation interactions change systematically with applied electric field. | Polarization and hyperconjugation are interrelated, not independent models. | [20] |

| Alkyl Group Electronegativity | Derived from Bond Energies | Calculated χ values: Me (2.52), t-Bu (~2.43). | Suggests t-Bu is less electron-withdrawing, contradicting charge analysis. Method criticized for inherent radical stability bias. | [15] [19] |

| NMR Chemical Shifts (¹³C) | Experimental Measurement | α-C shift: H < Me < Et < i-Pr < t-Bu (deshielded). β-C shift: opposite trend (shielded). | Often misattributed to -I trend. Better explained by combined –I and +R (hyperconjugation) effects. | [15] [19] |

Table 2: Impact of Spatial Confinement on Molecular Properties (H₂ Case Study)

| Property | Isolated Molecule Behavior | Effect of Spatial Confinement | Theoretical Model | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Polarizability (α) | Non-monotonic with bond stretch; reaches a maximum. | Significantly diminished at all internuclear distances. | 2D Harmonic Oscillator Potential | [21] [22] |

| Second Hyperpolarizability (γ) | Non-monotonic with bond stretch; reaches a maximum. | Significantly diminished at all internuclear distances. | 2D Harmonic Oscillator Potential | [21] [22] |

| Bond Length & Stiffness | Equilibrium at ~0.74 Å. | Reduced bond length, increased bond stiffness. | Various confining potentials | [21] [22] |

Detailed Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol A: Isolating the Inductive Effect via Charge Analysis

This protocol is designed to calculate the "pure" inductive effect of a substituent in a neutral molecule [15] [16].

- System Selection: Choose a series of neutral, saturated hydrocarbon molecules (e.g., CH₃-R, where R = H, Me, Et, i-Pr, t-Bu) or simple analogs with sp, sp², sp³ hybridization at the attachment point.

- Computational Setup:

- Software: Gaussian 09 or later [15] [16].

- Theory Level: Density Functional Theory (DFT).

- Functional: PBEh1PBE (also known as PBE0) [15] [16].

- Basis Set: aug-cc-pVTZ, a flexible, correlation-consistent basis set with diffuse functions [15] [16].

- Geometry: Optimize all structures to their ground-state minimum.

- Population Analysis: Perform a charge decomposition analysis on the optimized geometry. The Hirshfeld method is recommended as it shows good performance and logical results for organic molecules [16]. Other methods (CM5, NBO, QTAIM) should be used for validation.

- Data Extraction & Interpretation: Extract the partial charge on the key atom (e.g., the carbon attaching the group R). Compare the charge when R = alkyl group versus R = H. A more positive charge indicates an electron-withdrawing (–I) effect relative to hydrogen.

Protocol B: Probing the Polarizability-Hyperconjugation Link via Applied Fields

This protocol demonstrates how an external field modulates hyperconjugation [20].

- System Selection: Choose a model molecule with a defined hyperconjugative pathway (e.g., n-hexane for σ→σ* interactions, or fluoropentane for an asymmetric case).

- Computational Setup:

- Software: Gaussian suite.

- Theory Level: DFT (as in Protocol A) or ab initio methods suitable for property calculation.

- External Field: Introduce a static, uniform electric field along a specified molecular axis during the single-point energy calculation.

- Analysis: Conduct a Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis on the wavefunction calculated both with and without the applied field.

- Key Metrics: Quantify and compare the stabilization energy E(2) associated with critical donor-acceptor interactions (e.g., σ(C-H) → σ*(C-C)) under different field strengths. The systematic change in E(2) values with field strength evidences the direct coupling of polarization and hyperconjugation.

Protocol C: Calculating (Hyper)polarizabilities via the Finite-Field Method

This protocol is used to compute polarizability (α) and hyperpolarizability (γ) tensors [21] [22].

- System Preparation: Define the molecular geometry and orientation (principal axis aligned with the coordinate system, e.g., x-axis).

- Software & Method: Use Gaussian 16 with high-accuracy wavefunction methods (e.g., CISD with a large basis like d-aug-cc-pV6Z for small molecules) [21] [22].

- Field Application: Perform a series of single-point energy calculations with different strengths of an applied finite electric field (F) along the required axis. A sequence like F = 0, ±0.0004, ±0.0008, … au is typical.

- Numerical Differentiation: Fit the calculated energies E(F) to the Taylor expansion:

E(F) = E0 - μF - (1/2)αF² - (1/6)βF³ - (1/24)γF⁴ + .... Using an algorithm like Romberg-Rutishauser for numerical differentiation minimizes error [21] [22]. The second derivative yields α, and the fourth derivative yields γ. - Confinement Studies (Optional): To model spatial confinement, add the potential energy term for a harmonic oscillator potential

V_c = 1/2 ω² (x² + y²)to the Hamiltonian before solving [21] [22].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Interplay of Electronic Effects & Outcomes

Diagram 2: Workflow for Isolating Inductive Effects

Diagram 3: Hyperconjugation Modulated by an External Field

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Models for Studying Electronic Interplay

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application Example | Source/Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09/16 | Quantum Chemistry Software | Performs ab initio, DFT, and property calculations. | Geometry optimization, energy calculation under external fields, NBO analysis. | [15] [21] |

| PBEh1PBE (PBE0) Functional | Density Functional | Hybrid GGA functional providing good accuracy for energy and electronic structure. | Standard functional for charge distribution studies in organic molecules. | [15] [16] |

| aug-cc-pVTZ Basis Set | Basis Set | Correlation-consistent polarized valence basis set with added diffuse functions. | Provides flexible description of electron density for accurate charge and property analysis. | [15] [16] |

| Hirshfeld Charge Analysis | Population Analysis Method | Partitions electron density based on promolecule reference. | Calculates atomic partial charges considered reliable for inductive effect studies. | [15] [16] |

| Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis | Wavefunction Analysis | Localizes molecular orbitals into Lewis-type bonds and lone pairs. | Quantifies hyperconjugation stabilization energies (E(2)). | [20] [16] |

| Finite-Field (FF) Method | Computational Protocol | Calculates properties from energy derivatives wrt external field. | Computes static polarizability (α) and hyperpolarizability (γ). | [21] [22] |

| Drude Oscillator Model | Polarizable Force Field | Models electronic polarization via auxiliary charged particles. | MD simulations where environment-dependent polarization is critical. | [17] |

Harmonic Oscillator Potential (e.g., V_c=½ω²(x²+y²)) |

Model Confinement Potential | Represents spatial compression in computational studies. | Investigating confinement effects on polarizability and bond properties. | [21] [22] |

| SMIRNOFF/SMIRKS | Force Field Format | Defines parameters via chemical substructure patterns, not atom types. | Creating transferable, extensible force fields for diverse molecules. | [18] |

| CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) | General Force Field | Provides parameters for drug-like molecules compatible with CHARMM. | MD simulations of ligands in biological environments. | [18] |

Strategic Implementation in Drug Design and Functional Materials

Rational pKa and Basicity Tuning for Enhanced Pharmacokinetics

The acid-base dissociation constant (pKa) is a fundamental physicochemical property that governs the ionization state of drug molecules, thereby directly influencing their solubility, permeability, and overall pharmacokinetic profile. Rational modulation of pKa through strategic application of inductive and resonance effects represents a powerful tool in modern medicinal chemistry for optimizing drug disposition characteristics. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of how electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups, operating through sigma bonds (inductive effects) and pi systems (resonance effects), can be systematically employed to fine-tune molecular basicity and acidity. Through structured tables, experimental protocols, and mechanistic diagrams, we frame these electronic effects within the context of a broader thesis on molecular orbital interactions in organic molecules, providing researchers with a practical framework for enhancing pharmacokinetic properties through targeted pKa optimization.

The acid-base dissociation constant (pKa) quantifies the propensity of a molecule to donate or accept a proton, defining its ionization state across physiological pH environments. In drug development, pKa knowledge is crucial as it influences solubility, oral absorption, distribution, and pharmacokinetics [23]. The pKa value determines at what pH a drug exists in its ionized or non-ionized form, directly affecting its ability to cross cell membranes and bind to target sites. For instance, a drug that is predominantly ionized near physiological pH (approximately 7.4) will be more hydrophilic and consequently less capable of penetrating lipid membranes, while a non-ionized drug at the same pH will be more lipophilic and readily cross cellular barriers [23].

Approximately 75% of marketed drugs are weak bases, 20% are weak acids, and the remainder consist of non-ionics, ampholytes, and alcohols [24]. The distribution of pKa values for pharmaceutical substances is influenced by both the nature of commonly occurring functional groups and the biological targets these compounds are designed to engage. For example, central nervous system (CNS) drugs demonstrate a markedly different pKa profile compared to non-CNS drugs, with only one CNS compound having an acid pKa below 6.1 and no CNS compounds with basic pKa above 10.5 [24]. This distribution reflects the stringent requirements for blood-brain barrier penetration, illustrating how pharmacokinetic considerations directly influence optimal pKa ranges for different therapeutic applications.

Theoretical Foundations: Inductive and Resonance Effects

Electronic Effects on Acidity and Basicity

The pKa values of ionizable groups are influenced by structural factors through three primary electronic mechanisms: inductive effects, resonance effects, and hybridization effects [25] [26] [27]. These effects operate by stabilizing or destabilizing the charged species resulting from proton transfer, thereby affecting the thermodynamic equilibrium of acid-base reactions.

Table 1: Fundamental Electronic Effects Influencing pKa

| Effect Type | Transmission Mechanism | Impact on Acidity | Impact on Basicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inductive (-I) | Polarization through σ-bonds | Increases acidity | Decreases basicity |

| Inductive (+I) | Electron donation through σ-bonds | Decreases acidity | Increases basicity |

| Resonance (-M) | Electron withdrawal through π-system | Increases acidity | Decreases basicity |

| Resonance (+M) | Electron donation through π-system | Decreases acidity | Increases basicity |

| Hybridization | Changing s-character of orbital | Higher s-character increases acidity | Higher s-character decreases basicity |

The Inductive Effect

The inductive effect refers to the permanent polarization of σ-bonds between atoms with different electronegativities, resulting in the transmission of electronic effects through carbon chains [28]. This effect is particularly important for aliphatic systems and substituents without extended π-systems.

Negative Inductive Effect (-I): Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NO₂, -CN, -F, -Cl, -COOH) pull electron density toward themselves, stabilizing negative charges in conjugate bases, thereby increasing acidity [28]. For example, the pKa of trifluoroacetic acid (0.32) is significantly lower than that of acetic acid (4.54) due to the strong -I effect of fluorine atoms [25].

Positive Inductive Effect (+I): Electron-donating groups (e.g., -CH₃, -C₂H₅) push electron density toward the ionizable center, destabilizing negative charges in conjugate bases, thereby decreasing acidity [28].

The inductive effect is distance-dependent, strongest at the position directly attached to the functional group and fading rapidly with each intervening carbon atom [28].

Resonance Effects

Resonance effects involve the delocalization of π-electrons or lone pairs through conjugated systems, often exerting a stronger influence than inductive effects [29] [27]. When resonance and induction compete in influencing acidity or basicity, resonance effects typically dominate [29].

Resonance Electron-Withdrawing (-M): Groups such as nitro (-NO₂), carbonyl (C=O), and cyano (-CN) can delocalize negative charges through π-systems, significantly stabilizing conjugate bases and increasing acidity [27]. For example, the nitro group in p-nitrophenol stabilizes the negative charge on the phenolate oxygen through both inductive and resonance effects, resulting in greater acidity (pKa = 7.15) compared to m-nitrophenol (pKa = 8.39) where only inductive effects operate [27].

Resonance Electron-Donating (+M): Groups with lone pairs adjacent to π-systems (e.g., -OCH₃, -NH₂) can donate electron density into the π-system, destabilizing negative charges in conjugate bases and decreasing acidity [29]. For instance, 4-methoxyphenol (pKa = 10.2) is less acidic than phenol itself (pKa = 10.0) due to the electron-donating resonance effect of the methoxy group [29].

Figure 1: Logical relationship demonstrating how resonance stabilization of a conjugate base leads to increased acid strength through negative charge delocalization enabled by electron-withdrawing groups.

Quantitative pKa Tuning Strategies

Inductive Effect and Acidic Strength Relationships

The primary application of inductive effects in medicinal chemistry involves predicting and modulating acidic strength through strategic placement of electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups. The key principle states: acidity is proportional to the stability of the conjugate base. Electron-withdrawing (-I) groups stabilize the negative charge on the conjugate base, thereby increasing acidity (lowering pKa), while electron-donating (+I) groups destabilize the anion, reducing acid strength (increasing pKa) [28].

Table 2: Inductive Effects on Carboxylic Acid pKa Values

| Compound | Substituent | Inductive Effect | pKa | Relative Acidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trifluoroacetic acid | -CF₃ | Strong -I | 0.32 | Very high |

| Chloroacetic acid | -CH₂Cl | Strong -I | 2.87 | High |

| Acetic acid | -H | Reference | 4.76 | Moderate |

| Propanoic acid | -CH₃ | Weak +I | 4.87 | Slightly reduced |

| Isobutyric acid | -CH(CH₃)₂ | Moderate +I | 4.84 | Slightly reduced |

The magnitude of the inductive effect depends on both the nature and position of the substituent. For halogen atoms, the -I effect decreases in the order: -F > -Cl > -Br > -I [28]. The effect is strongest at the α-position and diminishes significantly at the γ-position and beyond.

Basicity Tuning in Amines and Nitrogen Heterocycles

Amines represent the most common basic functional group in pharmaceuticals, with their basicity governed by similar electronic principles [26]. The pKa of protonated amines (pKaH) serves as the key parameter, with higher values indicating stronger bases.

Table 3: Basicity Trends in Nitrogen-Containing Compounds

| Compound | Structure Type | pKaH | Major Electronic Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piperidine | Saturated amine | 11.0 | sp³ hybridization, localized lone pair |

| Ammonia | Inorganic reference | 9.2 | Reference compound |

| Pyridine | Aromatic heterocycle | 5.2 | sp² hybridization, localized lone pair |

| Aniline | Aromatic amine | 4.6 | Resonance delocalization into ring |

| Pyrrole | Aromatic heterocycle | 0.4 | Lone pair part of aromatic sextet |

| Acetamide | Amide | ~0.5 | Resonance and inductive effects |

Five key factors affect amine basicity [26]:

- Charge: Basicity increases with negative charge on nitrogen

- Resonance: Conjugated amines are less basic than non-conjugated amines

- Inductive Effects: Electron-withdrawing groups reduce basicity

- Pi-Acceptors: Adjacent C=O groups decrease basicity through resonance

- Hybridization: sp³ > sp² > sp in basicity (inverse relationship with s-character)

Figure 2: Key factors influencing amine basicity, with hybridization, resonance, and inductive effects representing the most significant design elements for pKa tuning.

pKa Ranges for Pharmacokinetic Optimization

Different therapeutic applications require specific pKa ranges to optimize pharmacokinetic properties. Analysis of marketed drugs reveals distinct patterns based on administration route and target tissue [24].

Table 4: pKa Guidelines for Different Drug Classes

| Drug Category | Optimal pKa Range | Rationale | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS Drugs | Bases: pKaH < 10.5Acids: pKa > 6.1 | Blood-brain barrier penetration | Limited basic CNS drugs with pKaH > 10.5 |

| Oral Drugs | Acids: pKa 3-7Bases: pKaH 6-10 | Balanced solubility/permeability | Various marketed compounds |

| Extended Distribution | pKa near physiological pH | Limited tissue penetration | Sustained release formulations |

For CNS targets, the predominance of amines is partly explained by the presence of key aspartic acid residues in G protein-coupled receptors (7TM GPCRs) that interact with basic nitrogen atoms [24]. This target-based requirement influences the pKa profile of drugs containing basic groups.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

pKa Determination Protocols

Accurate experimental determination of pKa values is essential for verifying computational predictions and establishing structure-property relationships. Several well-established methodologies are employed in pharmaceutical research.

Potentiometric Titration Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve compound in purified water to approximately 0.5-5 mM concentration. For compounds with limited aqueous solubility, add up to 30% cosolvent (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) with appropriate correction for cosolvent effects.

- Titration System: Use automated titrators (e.g., Pion Sirius T3) with combination pH electrode, dosing pump, and temperature control maintained at 25°C ± 0.5°C.

- Acid-Base Titration: Titrate from pH 2.0 to 12.0 with standardized 0.5 M KOH and 0.5 M HCl, recording pH after each addition once stability criterion (0.001 pH/min) is met.

- Data Analysis: Calculate pKa values from titration curve using appropriate software (e.g, Pion pKa PRO), applying Yasuda-Shedlovsky extrapolation for cosolvent-containing solutions.

UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Protocol:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare series of buffers covering expected pKa range (typically pH 1-12) with ionic strength adjusted to 0.15 M with KCl.

- Sample Measurement: Dissolve compound in each buffer solution and measure UV-Vis spectrum from 200-800 nm. Use concentrations that provide absorbance values between 0.1-1.0 AU.

- Data Analysis: Plot absorbance at characteristic wavelength versus pH. Fit data to Henderson-Hasselbalch equation to determine pKa value.

Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling

Integrating pKa-derived ionization profiles with PK/PD modeling enables prediction of in vivo performance and optimization of dosing regimens [30]. The implementation follows these key steps:

- Structural Model Identification: Develop compartmental model describing drug disposition, with ionization-dependent permeability and distribution.

- Covariate Analysis: Incorporate pKa-influenced parameters such as tissue-plasma partition coefficients and clearance mechanisms.

- Model Validation: Compare simulated concentration-time profiles with experimental data, refining parameters to improve predictive accuracy.

In the clinical development of CGM097, an HDM2 inhibitor, PK/PD modeling successfully characterized the relationship between drug exposure, platelet decrease, and GDF-15 biomarker induction, enabling dose optimization despite delayed-onset thrombocytopenia [30]. This approach facilitated the identification of safe and effective dosing regimens without reaching traditional maximum tolerated dose thresholds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for pKa and Basicity Studies

| Reagent/Instrument | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pion Sirius T3 | Automated pKa determination | High-throughput (72-80 assays/day) for discovery screening |

| Potentiometric Titrator | Traditional pKa measurement | Gold standard for ionizable compounds with adequate solubility |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | pKa of chromophoric compounds | Requires UV-active functional groups near ionization center |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Bioanalytical quantification | Essential for PK/PD correlation studies [30] |

| Molecular Modeling Software | pKa prediction | Computational estimation of ionization properties |

| ELISA Kits (e.g., GDF-15) | Biomarker quantification | PD endpoint measurement for target engagement [30] |

Rational pKa and basicity tuning through strategic application of inductive and resonance effects represents a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry optimization. By understanding how electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups influence ionization states through σ-bond and π-system effects, researchers can systematically design compounds with improved pharmacokinetic profiles. The integration of experimental pKa determination with computational prediction and PK/PD modeling creates a powerful framework for accelerating drug development. As pharmaceutical research increasingly targets complex disease pathways with sophisticated therapeutic modalities, the fundamental principles of pKa modulation remain essential for achieving optimal drug disposition and therapeutic efficacy.

The strategic incorporation of fluorine into bioactive molecules has revolutionized modern drug discovery. This transformation is fundamentally rooted in the unique electronic properties of the fluorine atom, primarily its powerful inductive effect (-I) and its capacity for resonance (mesomeric) interactions within conjugated systems [3] [31]. With the highest electronegativity of all elements (3.98 Pauling), fluorine exerts a strong electron-withdrawing influence through σ-bonds, polarizing adjacent bonds and altering electron density distribution across a molecule [32] [31]. This permanent polarization directly modulates key physicochemical parameters—most notably, metabolic stability and lipophilicity—that are critical determinants of a drug's Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADME-Tox) profile [33] [34]. Within the broader thesis of inductive and resonance effects in organic molecules, fluorine serves as a paramount case study, demonstrating how subtle, atom-level electronic perturbations can be harnessed to achieve profound improvements in biological performance [32] [35].

Theoretical Underpinnings: Inductive and Resonance Effects of Fluorine

The impact of fluorine is governed by two primary electronic mechanisms:

- Inductive Effect (-I): This is a through-bond, distance-dependent polarization. The fluorine atom withdraws electron density through successive σ-bonds, stabilizing adjacent negative charges and destabilizing positive ones [3] [31]. This is the dominant effect in aliphatic and meta-substituted aromatic systems.

- Resonance (Mesomeric) Effect: In conjugated systems, particularly at ortho and para positions of aromatic rings, fluorine's lone pairs can participate in p-π conjugation, donating electron density (+M effect) [3] [31]. This dual character—electron-withdrawing by induction and potentially electron-donating by resonance—makes fluorine's influence highly context-dependent and tunable.

These electronic effects translate directly into tangible molecular properties. The inductive effect lowers the pKa of nearby acidic groups (e.g., carboxylic acids) and increases the pKa of nearby basic groups (e.g., amines), allowing for precise modulation of ionization state [3] [34]. Furthermore, the strong C-F bond (~472 kJ/mol) and the alteration of electronic landscapes at potential metabolic soft spots are the foundational principles behind enhanced metabolic stability [32] [36].

The following tables summarize the quantitative effects of fluorination on key physicochemical and developmental parameters.

Table 1: Impact of Fluorine Substitution on Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Effect of Fluorine | Magnitude / Example | Primary Electronic Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipophilicity (logP) | Typically increases | Avg. ΔlogP ~ +0.17 for Ar-H→Ar-F [34]; Aliphatic motifs show variable, motif-dependent changes [37]. | Combined effect of increased hydrophobicity and altered electronic distribution. |

| Acidity/Basicity (pKa) | Lowers pKa of acids; Raises pKa of bases | Fluoroacetic acid pKa = 2.6 vs. Acetic acid pKa = 4.8 [3]. | Strong inductive (-I) effect stabilizes conjugate base of acids and destabilizes conjugate acid of bases. |

| Metabolic Stability | Generally increases | Blockade of aromatic and aliphatic oxidation sites; prevention of reactive metabolite formation [32] [34]. | Strong C-F bond and electronic deactivation of adjacent C-H bonds for oxidation. |

| Membrane Permeability | Often improves | Excellent correlation between ΔlogP and ΔlogKp (membrane partition coeff.) within congeneric series [37]. | Increased lipophilicity facilitating passive diffusion. |

Table 2: Prevalence of Fluorinated Drugs (Representative Data)

| Metric | Observation | Source/Year |

|---|---|---|

| Current Market Share | ~20% of pharmaceuticals, ~50% of agrochemicals contain fluorine [32]. | Review (2023) |

| FDA Approvals (2021) | 10 out of 50 novel drugs approved were fluorinated (20%) [32]. | FDA Novel Drug Approvals |

| FDA Approvals (2024) | Continued significant pipeline of fluorinated drug approvals [38]. | Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry (2025) |

| Role in COVID-19 | Multiple fluorinated drugs (e.g., Paxlovid components) were crucial in pandemic control [32]. | Review (2023) |

Core Mechanism I: Modulating Metabolic Stability

Contrary to an oversimplified explanation based solely on C-F bond strength, the metabolic stabilization conferred by fluorine is a consequence of its electronic effects on the mechanism of oxidative metabolism by cytochrome P450 enzymes [36].

- Blocking Aromatic Oxidation: The primary site of aromatic metabolism is the epoxidation of a C-H bond to form a phenolic metabolite. Fluorine substitution, particularly at the site of oxidation, is highly effective because:

- Inductive Deactivation: The strong -I effect withdraws electron density from the aromatic π-system, making the ring less nucleophilic and less susceptible to electrophilic attack by the high-valent iron-oxo species in P450s.

- Steric and Bond Strength: The C-F bond is both stronger and shorter than C-H, presenting a kinetic barrier to hydroxylation.

- Blocking Aliphatic Oxidation: For sp³ C-H bonds, fluorination at the α-carbon drastically reduces the rate of hydroxylation. The inductive effect stabilizes the incipient radical or carbocation-like transition state in the hydrogen atom transfer step, raising the activation energy for the reaction [36] [34].

- Preventing Toxic Metabolite Formation: Fluorine can be used strategically to divert metabolism away from pathways that generate reactive, electrophilic intermediates (e.g., quinone methides, epoxides), thereby mitigating idiosyncratic toxicity risks [34].

Title: Mechanism of Fluorine-Induced Metabolic Blockade

Core Mechanism II: Modulating Lipophilicity and Permeability

Lipophilicity (logP) is a key driver of passive membrane permeability. Fluorination offers a nuanced tool for its modulation, though the effect is not uniformly predictable and depends on the molecular context [37] [34].

- General Trend: Replacing H with F in an aromatic ring typically increases logP by ~0.17 units, as fluorine is more hydrophobic than hydrogen [34].

- Aliphatic Fluorination: The effect is more complex. CF₃ and CF₂ groups are strongly lipophilic, while a single fluorine on an aliphatic carbon can have a variable, sometimes even logP-lowering, effect due to polar interactions and changes in molecular conformation [37] [34].

- Correlation with Membrane Partitioning: Critically, for drug delivery, the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) must serve as a proxy for membrane-water partitioning (logKp). Research using solid-state ¹⁹F NMR has shown that within a congeneric series, modifications to logP via aliphatic fluorination are faithfully reproduced in logKp values [37]. This validates the use of fluorine to fine-tune membrane permeability for a given compound class.

Experimental Protocol: A Case Study in Optimizing ADME Properties

The following detailed methodology is adapted from a study optimizing a MK2 kinase inhibitor, where strategic fluorination improved permeability and oral exposure while maintaining potency [33].

Protocol: Fluorine Scan to Improve Permeability and PK in a Pentacyclic MK2 Inhibitor Series

1. Objective: To improve the poor oral bioavailability of lead compound 1 by modifying its hydrogen bond donor (HBD) strength and lipophilicity through targeted fluorination, without sacrificing kinase inhibitory potency.

2. Design & Synthesis:

- Target Analogue: Design a fluorinated analogue (19) replacing a key hydrogen or modifying a heterocycle with a fluorine atom or fluorinated group. In this case, a 3-fluoropyridine moiety was introduced.

- Synthetic Route (Key Steps): a. Directed Ortho Metalation (DOM): Start from 3-fluoro-2-chloropyridine (10). Use sequential metalation (t-BuLi, then n-BuLi) for functionalization at the 4- and 5- positions, enabling the construction of a tetrasubstituted pyridine core (11) [33]. b. Elaboration to Bromoketone: Add vinyl Grignard to an aldehyde intermediate, perform ring-closing metathesis, reduce the alkene, oxidize to ketone, and α-brominate to obtain key bromoketone building block 8. c. Hantzsch Pyrrole Synthesis: Condense bromoketone 8 with a spiro-piperidinedione 9 in the presence of ammonium acetate to form the pyrrole core (16). d. Final Functionalization: Deprotect, methylate an amine, and install final substituents via Suzuki coupling to yield target fluorinated compound 19 [33].

3. Key Experimental Assays & Measurements:

- Biochemical Potency: Measure IC₅₀ for inhibition of human MK2 kinase activity.

- Cellular Potency: Assess inhibition of hsp27 phosphorylation in anisomycin-stimulated THP-1 cells and inhibition of TNFα release from LPS-stimulated human PBMCs/whole blood.

- Permeability: Determine apparent permeability (Papp) using a high-throughput Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA).

- Lipophilicity: Measure distribution coefficient (logD₇.₄) at physiological pH using shake-flask or chromatographic methods.

- In Vivo Pharmacokinetics (Rat):

- IV PK: Administer compound intravenously (1 mg/kg, formulated in NMP/PEG200) to determine clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vd).

- Oral PK: Administer orally (3 mg/kg, formulated in CMC/water/Tween) to determine maximum concentration (Cmax), area under the curve (AUC), and calculate oral bioavailability (F%).

Title: Workflow for Fluorine-Driven ADME Optimization

Advanced Technique: Measuring Membrane Partitioning via ¹⁹F NMR

To directly validate the impact of fluorination on membrane interactions, a novel solid-state ¹⁹F Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) NMR protocol was developed [37].

Protocol: Determination of Membrane-Water Partition Coefficient (logKp) using ¹⁹F MAS NMR

1. Sample Preparation:

- Lipid Vesicles: Prepare multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) or POPC/cholesterol mixtures in buffer (e.g., Tris, pH 7.4). Achieve a final lipid hydration level of 20% (w/v).

- Compound Incorporation: Add the fluorinated test compound from a DMSO stock solution to the MLV suspension. Use a compound-to-lipid molar ratio of 0.033 (e.g., 3.3 mol%).

- Loading: Pack the homogeneous suspension into a zirconia MAS NMR rotor.

2. NMR Acquisition:

- Instrumentation: High-field NMR spectrometer equipped with a ¹⁹F/H MAS probe.

- Conditions: Acquire ¹⁹F NMR spectra under MAS at a moderate spinning speed (e.g., 10 kHz) with low-power ¹H decoupling (e.g., 10 kHz field). Use a simple one-pulse sequence with adequate recycle delay.

- Observation: Two distinct ¹⁹F resonances will be observed: a sharp peak from the compound free in the aqueous phase and a broader peak from the compound partitioned into the lipid bilayer. The slow exchange on the NMR timescale allows for direct integration.

3. Data Analysis & Calculation:

- Integration: Precisely integrate the areas of the aqueous peak (Iaq) and the membrane-bound peak (Imem).

- Calculation: The molar partition coefficient, Kp, is calculated as:

Kp = (I_mem / I_aq) * (V_aq / V_mem)where Vaq and Vmem are the volumes of the aqueous and membrane phases, respectively, which are known from sample preparation. - logKp: Determine as log₁₀(Kp). This value can be correlated with the computed or measured octanol-water logP for the compound series.

Title: ¹⁹F NMR Method for Membrane Partitioning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Fluorine ADME Studies