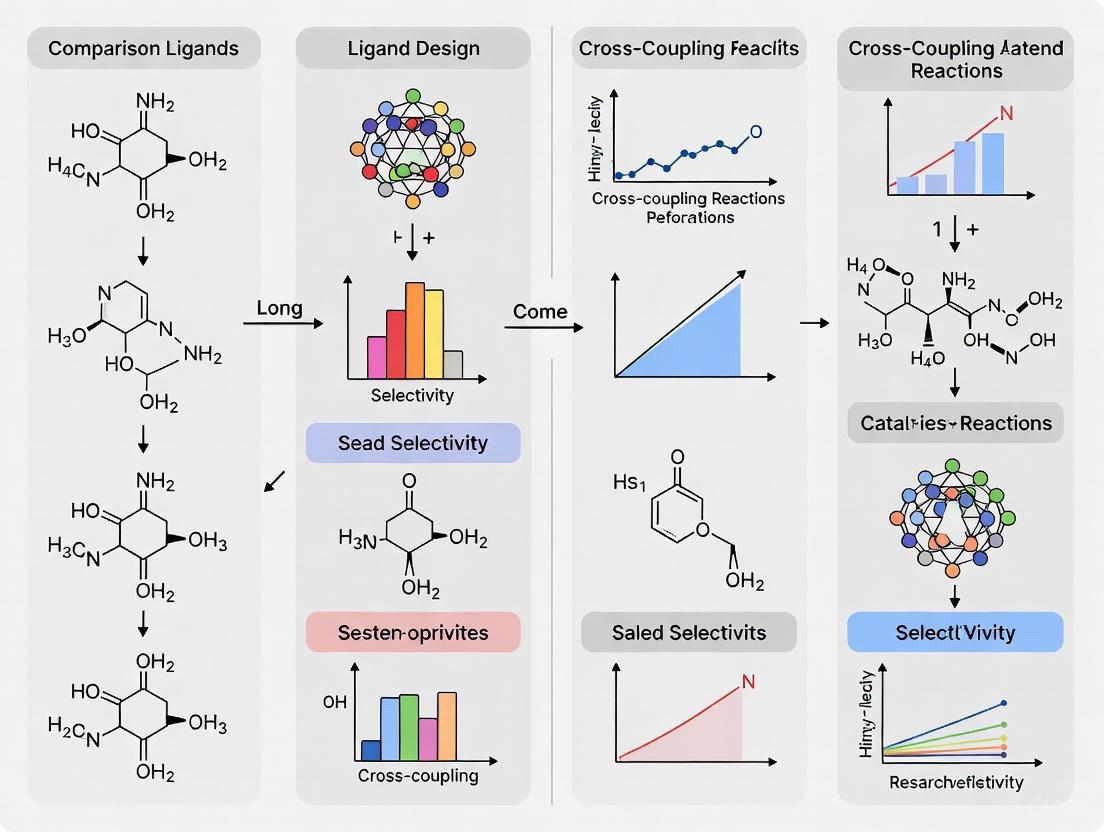

Ligand Comparison in Cross-Coupling Reactions: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development and Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ligand selection for cross-coupling reactions, a cornerstone of modern organic synthesis in pharmaceutical and agrochemical development.

Ligand Comparison in Cross-Coupling Reactions: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development and Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ligand selection for cross-coupling reactions, a cornerstone of modern organic synthesis in pharmaceutical and agrochemical development. It bridges fundamental concepts—exploring ligand properties, metal compatibility, and the pivotal Pd(0)/Pd(II) catalytic cycle—with advanced methodological applications, including specialized ligand design for challenging substrates. The content delivers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance catalytic efficiency and reaction reliability. Finally, it offers a validated, comparative framework for selecting optimal ligand systems across various reaction classes, empowering researchers to streamline synthetic routes for drug candidates and complex molecules.

Ligand Fundamentals: Understanding Electronics, Sterics, and the Catalytic Cycle

In palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, which are cornerstone methods for carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formation in pharmaceutical and agrochemical synthesis, ligands transcend their traditional supportive role to become decisive determinants of catalytic efficiency and selectivity [1] [2]. These organic molecules coordinated to the palladium center are fundamentally responsible for stabilizing the active catalyst, controlling its reactivity, and steering the pathway toward the desired product while suppressing undesired side reactions [1] [3]. The evolution from simple triarylphosphines to sophisticated specialized ligands represents one of the most significant advances in cross-coupling methodology over the past two decades, enabling reactions with previously challenging substrates and driving the widespread adoption of these transformations in industrial applications [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major ligand classes, supported by experimental data and protocols, to inform rational ligand selection in research and development.

Ligand Classes and Their Performance Characteristics

Traditional and Modern Ligand Architectures

Cross-coupling ligands span diverse structural classes, each imparting distinct steric and electronic properties to the catalytic system. Traditional monodentate phosphines like triphenylphosphine (PPh₃) remain popular due to low cost and availability but offer limited effectiveness in modern applications [1] [4]. Bidentate phosphines including 1,1'-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (DPPF) and 1,3-bis(diphenylphosphino)propane (DPPP) provide enhanced stability through chelation effects [1]. Dialkylbiarylphosphines, pioneered by Buchwald and others, feature substantial steric bulk that accelerates oxidative addition and reductive elimination, enabling room-temperature couplings of unactivated substrates [2]. N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) have emerged as strong σ-donors that often outperform phosphines in sterically demanding transformations [2]. Most recently, aminophosphines such as tris(dibutylamino)phosphine (P₃N ligands) offer synthetic simplicity and sustainability advantages while maintaining high activity in aqueous media [4].

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Reaction Types

Table 1: Ligand Performance in Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactions

| Ligand Class | Specific Ligand | Pd Source | Base | Solvent | Yield (%) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Monodentate | PPh₃ | Pd(OAc)₂ | K₂CO₃ | DMF | 40-60 [1] | Low cost, widely available |

| Bidentate Phosphines | DPPF | PdCl₂(DPPF) | Cs₂CO₃ | DMF/HEP | 85-95 [1] | Enhanced stability, chelation effect |

| Dialkylbiarylphosphines | SPhos | Pd(OAc)₂ | K₃PO₄ | DMF | 90-99 [2] | Handles steric hindrance, room temperature capability |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbenes | IPr | Pd₂(dba)₃ | t-BuOK | Toluene | 85-98 [2] | Excellent for bulky substrates, strong σ-donation |

| Aminophosphines (P₃N) | (n-Bu₂N)₃P | [Pd(allyl)Cl]₂ | Et₃N | H₂O/SDS | 92 [4] | Sustainable synthesis, aqueous conditions |

Table 2: Ligand Performance in Heck-Cassar-Sonogashira Reactions

| Ligand Class | Specific Ligand | Pd Source | Base | Solvent | Yield (%) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Monodentate | PPh₃ | Pd(OAc)₂ | TMG | DMF/HEP | 45-65 [1] | Standard for basic systems |

| Bidentate Phosphines | DPPP | PdCl₂(ACN)₂ | Pyrrolidine | DMF | 75-85 [1] | Balanced activity and stability |

| Dialkylbiarylphosphines | XPhos | Pd(OAc)₂ | Et₃N | H₂O/TPGS-750-M | 80-90 [4] | Broad substrate scope |

| Aminophosphines | (n-Bu₂N)₃P | [Pd(allyl)Cl]₂ | Et₃N | H₂O/SDS | 92 [4] | Copper-free conditions, excellent recyclability |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation of Ligand Efficiency

Protocol for In Situ Pre-catalyst Reduction Studies [1]:

- Reaction Setup: In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, combine Pd(OAc)₂ (0.02 mmol) and ligand (0.022 mmol for monodentate; 0.021 mmol for bidentate) in 4 mL of DMF or THF solvent.

- Additive Introduction: Introduce primary alcohols such as N-hydroxyethyl pyrrolidone (HEP) as a co-solvent (30% v/v) to facilitate Pd(II) reduction without phosphine oxidation.

- Base Screening: Evaluate various bases including N,N,N',N'-tetramethylguanidine (TMG), triethylamine (TEA), Cs₂CO₃, K₂CO₃, and pyrrolidine.

- Monitoring: Track reduction efficiency using ³¹P NMR spectroscopy to characterize formed Pd(0) species and detect potential nanoparticle formation.

- Analysis: Correlate reduction efficiency with catalytic activity in model Suzuki-Miyaura and Heck-Cassar-Sonogashira reactions.

Key Finding: The combination of counterion, ligand, and base must be carefully optimized to control Pd(II) reduction to Pd(0) while preserving ligand integrity and avoiding substrate consumption through dimerization pathways [1].

Ligand Synthesis:

- Charge a dry flask with PCl₃ (1.0 equiv) and dissolve in anhydrous diethyl ether.

- Add n-Bu₂NH (3.2 equiv) dropwise at 0°C over 30 minutes.

- Warm reaction mixture to room temperature and stir for 12 hours.

- Filter to remove ammonium salts and concentrate filtrate under vacuum.

- Purify by distillation under reduced pressure to obtain (n-Bu₂N)₃P as a colorless liquid.

Cross-Coupling Procedure:

- In a reaction vial, combine [Pd(allyl)Cl]₂ (0.5 mol%), (n-Bu₂N)₃P (2.0 mol%), and SDS (2 wt%) in deionized water.

- Add aryl halide (1.0 equiv), boronic acid (1.5 equiv), and triethylamine (2.0 equiv).

- Stir reaction mixture at 60°C for 16 hours monitoring by TLC or GC-MS.

- Upon completion, extract with ethyl acetate, dry over Na₂SO₄, and concentrate.

- Purify crude product by flash chromatography to afford isolated biaryl products.

Mechanism and Catalyst Activation Pathways

The catalytic cycle for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling follows a fundamental Pd(0)/Pd(II) pathway, but ligand structure profoundly influences each elementary step [2]. Oxidative addition of the organic electrophile to Pd(0) is accelerated by electron-rich ligands, with dialkylbiarylphosphines providing both steric and electronic optimization [2]. The transmetalation step exhibits strong dependence on ligand architecture, where excessive steric bulk can inhibit this process while insufficient stabilization may lead to catalyst decomposition [3]. Finally, reductive elimination to form the product and regenerate the Pd(0) catalyst is dramatically accelerated by bulky ligands that destabilize the Pd(II) intermediate [2].

Diagram 1: Ligand-Modified Catalytic Cycle for Cross-Coupling (47 characters)

The ligand-controlled catalytic cycle highlights how specialized ligands influence each mechanistic step, from the critical in situ pre-catalyst reduction to the final reductive elimination that reforms the active Pd(0) species [1] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Ligand Evaluation in Cross-Coupling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Catalytic System |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Sources | Pd(OAc)₂, PdCl₂(ACN)₂, [Pd(allyl)Cl]₂, Pd₂(dba)₃ | Pre-catalyst precursors that determine initial oxidation state and reduction pathway [1] [4] |

| Phosphine Ligands | PPh₃, DPPF, DPPP, Xantphos, SPhos, XPhos, RuPhos | Control steric and electronic properties, stabilize active species, dictate catalytic activity [1] [2] |

| NHC Ligands | IPr, IMes, SIPr | Strong σ-donors particularly effective for sterically hindered couplings [2] |

| Aminophosphines | (n-Bu₂N)₃P, (Et₂N)₃P, (C₆H₁₁)₃P | Sustainable alternatives with straightforward synthesis and good aqueous compatibility [4] |

| Solvent Systems | DMF, THF, Toluene, H₂O/SDS, H₂O/TPGS-750-M | Reaction medium affecting solubility, pre-catalyst activation, and nanomicelle formation [1] [4] |

| Base Additives | K₂CO₃, Cs₂CO₃, Et₃N, TMG, K₃PO₄, t-BuOK | Critical for transmetalation step and controlling in situ reduction pathways [1] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of cross-coupling ligand design is evolving toward sustainable synthesis with simplified preparation routes, as exemplified by single-step P₃N ligands that avoid resource-intensive multi-step sequences [4]. Machine learning approaches are accelerating ligand discovery, with recent studies identifying an "active ligand space" defined by a ±10 kJ mol⁻¹ window of optimal ligand binding strength for specific transformations [5]. The development of aqueous-compatible catalytic systems represents another frontier, where ligand hydrophobicity can be tuned to enhance compatibility with micellar environments [4]. Finally, high-throughput experimentation coupled with multivariate data analysis enables comprehensive mapping of complex reaction landscapes, revealing subtle ligand effects on product distributions and side-product formation [3].

These advances collectively point toward a future where ligand selection transitions from empirical screening to rational design based on quantitative structure-activity relationships and predictive computational models, ultimately expanding the synthetic toolbox available for pharmaceutical development and fine chemical synthesis.

In transition-metal catalysis, the performance of a catalyst is profoundly influenced by the properties of the ligands coordinated to the metal center. For cross-coupling reactions—indispensable tools in pharmaceutical development and fine chemical synthesis—rational ligand selection is paramount for achieving high activity and selectivity [6]. Quantitative parameters have been developed to describe three fundamental ligand characteristics: steric bulk (cone angle), geometric constraint (bite angle), and electronic properties (electronic parameters). These descriptors enable researchers to move beyond qualitative guesses, establishing predictive relationships between ligand structure and catalytic function [7] [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these parameters, their experimental determination, and their practical application in cross-coupling research.

Defining the Fundamental Parameters

Cone Angle: Quantifying Steric Bulk

The cone angle (θ) provides a three-dimensional measure of a ligand's steric volume around a metal center. Developed by Chadwick Tolman, it is defined as the apex angle in a cone with its vertex at the metal center, encompassing the ligand's van der Waals radii [9].

- Symmetrical Ligands: For symmetric ligands like PPh₃, the cone angle is a single value [9].

- Asymmetric Ligands: For asymmetric ligands (PRR'R"), the individual half-angles for each substituent are averaged:

θ = 2/3 Σ(θᵢ/2)[9].

Cone angles significantly impact catalytic outcomes by influencing metal coordination geometry, substrate approach, and reductive elimination rates. In cross-coupling, larger cone angles can accelerate reductive elimination but may hinder oxidative addition if steric crowding becomes excessive [4].

Table 1: Representative Tolman Cone Angles for Common Phosphine Ligands

| Ligand | Cone Angle (°) | Ligand | Cone Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PH₃ | 87 | P(cyclo-C₆H₁₁)₃ | 179 |

| PF₃ | 104 | P(t-Bu)₃ | 182 |

| P(OCH₃)₃ | 107 | P(C₆F₅)₃ | 184 |

| P(CH₃)₃ | 118 | P(C₆H₄-2-CH₃)₃ | 194 |

| P(CH₂CH₃)₃ | 132 | P(2,4,6-Me₃C₆H₂)₃ | 212 |

| P(C₆H₅)₃ | 145 |

Bite Angle: The Geometric Constraint of Chelating Ligands

The bite angle is the preferred chelating angle formed by the two donor atoms of a bidentate ligand and the metal center (∠P–M–P) [10]. It is an intrinsic geometric property of the ligand that dictates the spatial arrangement of the coordination sphere.

- Catalytic Influence: The bite angle directly affects catalytic selectivity and reactivity by forcing the metal into specific geometries that control the orientation of substrates and transition states [8].

- Beyond Innate Value: The flexibility of a ligand and its ability to deviate from its natural bite angle under catalytic conditions are as crucial as the angle itself [7].

Table 2: Natural Bite Angles for Selected Bidentate Ligands

| Ligand Backbone | Natural Bite Angle (°) | Key Catalytic Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene (CH₂) | ~74 | Constrained geometry |

| Ethylene (C₂H₄) | ~85 | Common for many diphosphines |

| Propylene (C₃H₆) | ~90 | Balanced flexibility and constraint |

| Xantphos types | 100-125 | Promotes bis-equatorial coordination |

Electronic Parameters: Measuring Donor/Acceptor Character

Electronic parameters quantify a ligand's ability to donate or accept electron density from the metal, thereby influencing the metal's electron density and reactivity.

- Tolman Electronic Parameter (χ): Measured as the A₁ carbonyl stretching frequency (in cm⁻¹) in Ni(CO)₃L complexes. A lower frequency indicates stronger σ-donor ability [8].

- %V_Bur (Percent Buried Volume): A modern steric descriptor calculating the fraction of the metal's coordination sphere occupied by the ligand. It provides a more accurate steric picture for asymmetric ligands than the cone angle [11].

- ¹Jₛₑ₋ₚ Coupling Constant: The selenium-phosphorus coupling constant in phosphine-selenide derivatives serves as a proxy for electronic character. A smaller ¹Jₛₑ₋ₚ value indicates stronger σ-donor ability [8].

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Computational Workflow for Descriptor Extraction

Modern virtual screening relies on automated computational workflows to generate complexes and calculate descriptors. These workflows are crucial for handling conformational flexibility and obtaining accurate parameters [7] [11].

Diagram 1: Computational descriptor workflow.

Key Experimental Measurements

Spectroscopic Determination of Electronic Parameters

Tolman Electronic Parameter (χ):

- Synthesize the complex Ni(CO)₃L under inert atmosphere.

- Record the IR spectrum in a non-coordinating solvent (e.g., cyclohexane).

- Identify the symmetric A₁ carbonyl stretching band.

- Report the frequency in cm⁻¹. Values typically range from ~2040 cm⁻¹ for poor donors to ~2080 cm⁻¹ for strong π-acceptors [8].

¹Jₛₑ₋ₚ Coupling Constant:

- Oxidize the phosphine ligand to its corresponding phosphine-selenide (R₃P=Se).

- Dissolve in an appropriate deuterated solvent.

- Acquire a ³¹P NMR spectrum.

- Measure the Se-P coupling constant from the satellite peaks. Stronger σ-donors exhibit smaller coupling constants [8].

Crystallographic and Computational Determination of Steric Parameters

Cone Angle from X-ray Crystallography:

- Obtain a high-quality single crystal of the metal complex.

- Perform an X-ray diffraction study to determine the molecular structure.

- Using the coordinates, place the metal at the cone's vertex (using a standard M-P bond length for comparison, e.g., 2.28 Å for Ni).

- Calculate the cone angle as the angle between vectors tangential to the outermost atoms' van der Waals spheres [9].

%V_Bur Calculation:

- A 3D structure of the metal complex is required (from X-ray or DFT optimization).

- Define a sphere around the metal center with a given radius (typically 3.5 Å for palladium).

- Calculate the volume of this sphere occupied by the ligand atoms.

- Express this volume as a percentage of the total sphere volume [11].

Comparative Analysis in Cross-Coupling Reactions

Ligand Performance in Model Reactions

The interplay of steric and electronic parameters dictates ligand efficacy in cross-coupling. The following table synthesizes data from recent studies on Suzuki-Miyaura and Heck couplings.

Table 3: Ligand Parameter Correlation with Cross-Coupling Performance

| Ligand / Type | Key Steric Parameter | Key Electronic Parameter | Reaction Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPh₃ (Monodentate) | θ = 145° | Moderate donor | Baseline activity; limited in demanding substrates [4]. |

| XPhos (Bidentate) | Wide bite angle | Strong donor | Effective in aqueous Sonogashira; good activity [4]. |

| P3N-type, L4 (Aminophosphine) | High lipophilicity/bulk | Strong σ-donor | 92% yield in Heck-Sonogashira; excellent in micellar media [4]. |

| Diphosphine L4 (Indolyl-based) | Specific backbone | Strong π-acceptor (¹Jₛₑ₋ₚ = 740 Hz) | Enables hydroformylation of strained alkenes [8]. |

Case Study: Aqueous Micellar Cross-Coupling

A 2025 study highlights the critical role of parameter balancing. A new P3N ligand (L4, (n-Bu₂N)₃P) was evaluated against established ligands in copper-free Heck-Cassar-Sonogashira couplings in water [4].

- Steric Demand & Lipophilicity: L4's steric bulk around phosphorus and high lipophilicity improved its compatibility with the SDS micellar environment, enhancing catalyst stability and substrate partitioning.

- Electronic Profile: As a strong σ-donor, L4 increased electron density on palladium, facilitating the critical oxidative addition step.

- Performance: L4 achieved 92% yield with only 0.5 mol% Pd loading, outperforming other aminophosphines and XPhos, which gave lower conversions (10-79%) [4]. This demonstrates how tailored steric and electronic properties solve challenges like aqueous solubility and stability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation in ligand design and catalysis requires specific tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured studies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| CREST (GFN2-xTB//GFN-FF) | Conformer ensemble generation for flexible ligands. | Sampling the conformational landscape of bisphosphines prior to DFT [11]. |

| DFT Methods (PBE0-D3(BJ)) | Quantum chemical geometry optimization and property calculation. | Calculating accurate bite angles, HOMO-LUMO gaps, and %V_Bur [7] [11]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic surfactant for forming aqueous micellar reaction media. | Enabling cross-couplings in water, replacing toxic organic solvents [4]. |

| [Pd(allyl)Cl]₂ | Palladium source for pre-catalyst formation. | Used with P3N ligands to form active catalytic species in water [4]. |

| Phosphine Selenide Probes | Reporting on the electronic character of phosphorus ligands. | Determining σ-donor strength via ¹Jₛₑ₋ₚ coupling constants [8]. |

Integrated Workflow for Ligand Selection

Navigating the multi-parameter space of ligand design requires a structured approach. The following diagram and process outline a rational strategy for ligand selection in cross-coupling reaction development.

Diagram 2: Rational ligand selection workflow.

- Define the Catalytic Challenge: Identify the reaction type and the likely turnover-determining or selectivity-determining step (e.g., oxidative addition, reductive elimination).

- Map the Parameter Space:

- For reductive elimination, favor ligands with large cone angles (>160°) or wide bite angles (>100°) to relieve steric crowding [7].

- For oxidative addition into Ar-X bonds, a strong σ-donor ligand electronically enriches the metal to facilitate oxidation.

- For reactions in aqueous media, consider ligand lipophilicity to ensure compatibility with micellar systems [4].

- Generate and Screen Candidates: Use computational workflows (Diagram 1) to shortlist promising ligands by calculating their key parameters before resource-intensive synthesis and testing.

- Model and Iterate: Employ statistical modeling (e.g., machine learning, linear regression) to correlate the measured parameters with catalytic performance, creating a predictive model for future ligand design [7] [11].

Cone angle, bite angle, and electronic parameters provide a powerful, quantitative language for ligand design in cross-coupling catalysis. Moving from qualitative "trial-and-error" to a parameter-driven approach enables rational catalyst optimization. The integration of computational descriptor calculation with experimental validation, as outlined in this guide, represents the modern paradigm. As machine learning models become more sophisticated, the accuracy of predicting catalytic outcomes from these fundamental ligand properties will only increase, further accelerating the development of efficient and sustainable catalytic processes for pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis.

Homogeneous palladium catalysis constitutes a cornerstone of modern synthetic chemistry, enabling the construction of carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds with high efficiency and selectivity. These transformations are indispensable in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries for the synthesis of complex molecules. The catalytic cycle operates predominantly through a Pd(0)/Pd(II) manifold, where the palladium center undergoes oxidation states between 0 and +2. Within this framework, ligands are not mere spectators; they are integral components that fundamentally alter the structure and electronic properties of the metal center, thereby influencing the activation energy of every elementary step. Ligands exert control over kinetic reactivity, regio- and stereoselectivity, catalyst longevity, and operational stability. This guide provides a mechanistic comparison of how different ligand classes—including monodentate and bidentate phosphines, and N,O-donors—govern critical steps in the Pd(0)/Pd(II) cycle, supported by quantitative data and experimental protocols for direct comparison [12] [13] [14].

The Catalytic Cycle: A Ligand's Journey

The canonical Pd(0)/Pd(II) cross-coupling cycle comprises three core steps: oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination. The ligand coordination sphere dynamically changes throughout this cycle, directly impacting the energy landscape of each step. The following diagram maps the catalytic cycle and highlights the specific points of ligand influence.

- Pre-catalyst Activation: The cycle is often initiated from a Pd(II) source (e.g., Pd(OAc)₂, PdCl₂, Pd(acac)₂) which must be reduced to the active Pd(0) species. The ligand plays a critical role in this step, as its electronic and steric properties can either promote clean reduction or lead to unproductive decomposition pathways [1] [15].

- Oxidative Addition: An aryl (pseudo)halide (Ar–X) adds to the Pd(0) center, oxidizing it to Pd(II). The rate of this step is highly sensitive to the electron density and steric profile of the ligand [12].

- Transmetalation: The organometallic nucleophile (R–M) transfers its R-group to the palladium center, forming a Pd(II)(Ar)(R) species. The mechanism of this step is highly dependent on the ligand's ability to create a vacant coordination site and stabilize the transition state [16].

- Reductive Elimination: The final C–C bond is formed, and the Pd(0) catalyst is regenerated. Ligand bulk is often crucial to accelerate this step by destabilizing the Pd(II)(Ar)(R) ground state [12].

Quantitative Comparison of Ligand Performance

The following tables summarize experimental data from key studies, providing a direct comparison of ligand efficacy across different reaction steps and conditions.

Table 1: Ligand Influence on Pre-catalyst Reduction and Oxidative Addition

| Ligand | Ligand Type | Pd Precursor | Reduction Efficiency / Conditions | Oxidative Addition Rate / Substrate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPh₃ [1] [15] | Monodentate Phosphine | Pd(OAc)₂, Pd(acac)₂ | High with primary alcohols as reductant | Moderate / Aryl Iodides & Bromides | Reduction pathway well-studied; can form Pd nanoparticles if uncontrolled [1] [15]. |

| XPhos [1] | Bulky Biarylphosphine | Pd(OAc)₂, PdCl₂(ACN)₂ | High with optimized base/solvent pairs | High / Aryl Chlorides | Electron-richness and bulk facilitate oxidative addition of challenging Ar–Cl bonds [12] [1]. |

| DPPF [1] [17] | Bidentate Phosphine | Pd(OAc)₂, PdCl₂(DPPF) | Moderate to High | High / Aryl Bromides | Chelate effect provides stability; widely used in Ni/Pd-catalyzed SMCs [1] [17]. |

| SPhos [1] | Bulky Biarylphosphine | Pd(OAc)₂ | High with primary alcohols as reductant | High / Aryl Chlorides | Superior performance in Suzuki-Miyaura couplings with deactivated substrates [1]. |

| Mono-N-protected Amino Acids [12] | Bifunctional (N,O) | Pd(OAc)₂ | Not Specified | Not Applicable (C-H Activation) | Key for Pd(II)-catalyzed C-H functionalization; acts as a directing ligand and proton shuttle [12] [13]. |

Table 2: Ligand Influence on Transmetalation and Reductive Elimination

| Ligand | Transmetalation Mechanism | Reductive Elimination Rate | Exemplary Reaction Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPh₃ [16] | Involves Si–O–Pd intermediate (8-Si-4) | Moderate | Effective in HCS and telomerization reactions [1] [15] | Lability allows for site vacancy during transmetalation. |

| Dppf [17] [16] | Can occur via anionic 10-Si-5 intermediate with Cs⁺ [16] | Fast | Top performer in many Ni-/Pd-catalyzed Suzuki reactions [17] | The bite angle and electronic properties tune reactivity at both steps. |

| Bidentate N,O-Ligands [14] | Not explicitly detailed | Not explicitly detailed | Enables coupling of aryl chlorides under mild conditions [14] | Air and moisture stability is a major advantage over phosphines. |

| Bulky Biarylphosphines (SPhos, XPhos) [12] [1] | Not explicitly detailed | Very Fast | High yields in SM coupling of sterically hindered partners [1] | The large cone angle creates a coordinatively unsaturated complex, promoting both transmetalation and reductive elimination. |

| Dcypf [17] | Not explicitly detailed | Fast | Outperforms DPPF in electronically mismatched SMC pairings [17] | Increased electron density from Cy groups enhances performance. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Mechanistic Studies

Protocol 1: Monitoring Pre-catalyst Reduction by ³¹P NMR

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the controlled reduction of Pd(II) precursors to generate active Pd(0) species while avoiding phosphine oxidation [1].

- Objective: To observe the conversion of Pd(II)-phosphine complexes to Pd(0) species and identify potential by-products like phosphine oxides.

- Key Reagents:

- Palladium Source: Pd(OAc)₂ or PdCl₂(ACN)₂.

- Ligand: The phosphine ligand under investigation (e.g., PPh₃, DPPF, XPhos).

- Reductant/Solvent: Primary alcohols (e.g., N-hydroxyethyl pyrrolidone, HEP) in DMF or THF.

- Base: N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylguanidine (TMG), triethylamine (TEA), or carbonates (Cs₂CO₃, K₂CO₃).

- Methodology:

- Prepare a solution of the Pd(II) salt and ligand (1:1 to 1:2 ratio) in the chosen solvent in an NMR tube.

- Add the base and reductant (if used).

- Acquire ³¹P NMR spectra immediately and at regular time intervals.

- Monitor the disappearance of the starting Pd(II)-ligand complex peaks and the appearance of new signals corresponding to Pd(0) complexes and phosphine oxide.

- Data Interpretation: A clean reduction is indicated by the quantitative formation of the target Pd(0) complex with minimal phosphine oxide signals. The choice of counterion (acetate vs. chloride) and base significantly impacts the reduction efficiency and pathway [1].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Analysis of Transmetalation Using Isolated Intermediates

This protocol is based on the isolation and study of arylpalladium(II) silanolate complexes to dissect the transmetalation step [16].

- Objective: To determine the rate constant of the transmetalation step independently from other catalytic steps.

- Key Reagents:

- Pre-formed Intermediate: Arylpalladium(II) alkenylsilanolate complex, e.g.,

(Xantphos)Pd(Ar)(OSiR₂=CR'₂). - Additive: Tetraalkylammonium salts (e.g., NBu₄F) or cesium salts to study anionic pathways.

- Solvent: Tetrahydrofuran (THF) or 1,4-Dioxane.

- Pre-formed Intermediate: Arylpalladium(II) alkenylsilanolate complex, e.g.,

- Methodology:

- Synthesize and isolate the stable pre-transmetalation intermediate.

- Dissolve the intermediate in the chosen solvent in a reaction vessel equipped for monitoring (e.g., by UV-Vis or NMR spectroscopy).

- Initiate the reaction by adding the desired additive or by thermal activation.

- Track the disappearance of the starting intermediate and the formation of the biaryl reductive elimination product or the Pd(0) species.

- Data Interpretation: The kinetics can reveal whether transmetalation proceeds via a neutral (8-Si-4) or anionic (10-Si-5) mechanism. The order in the intermediate and additive, along with the calculated rate constant, provides direct insight into the influence of the ligand and reaction conditions on this critical step [16].

Protocol 3: Disassembling a Dual Catalytic Process into Elementary Steps

This approach involves breaking down a complex catalytic reaction, such as the copper-free Sonogashira reaction, into its proposed elementary steps for individual kinetic study [18].

- Objective: To identify the rate-determining step and the entry point of reagents by independently studying each proposed step of the mechanism.

- Key Reagents:

- Isolated Intermediates: Pre-formed oxidative addition complexes

LnPd(Ar)(X)and palladium acetylidesLnPd(C≡CR)₂. - Palladium Source:

Pd(PPh₃)₄or related complexes. - Substrates: Aryl halides and terminal alkynes.

- Isolated Intermediates: Pre-formed oxidative addition complexes

- Methodology:

- Synthesize Proposed Intermediates: Isolate and characterize key species like palladium bisacetylides and monoacetylides.

- Study Step 1 - Nucleophile Formation: Measure the rate of formation of palladium bisacetylide from

LnPdX₂and terminal alkyne. - Study Step 2 - Transmetalation: Measure the rate of reaction between the isolated oxidative addition complex and the isolated palladium bisacetylide to form the product.

- Compare Rates: Compare the measured rates of all independent elementary steps under identical conditions.

- Data Interpretation: The slowest step among the elementary reactions is identified as the rate-determining step for the overall catalytic process. This method confirmed transmetalation between two palladium complexes as a viable pathway in copper-free Sonogashira reactions [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their functions for studying mechanisms in Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Mechanistic Studies | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Pd(OAc)₂ / PdCl₂(ACN)₂ [1] | Common Pd(II) pre-catalyst sources. | Starting material for in situ generation of active Pd(0) catalysts; study of reduction pathways. |

| Pd(acac)₂ [15] | Neutral Pd(II) source for specific catalytic systems. | Model pre-catalyst for industrial telomerization and other reactions; study of alternative reduction pathways. |

| Pd₂(dba)₃ [1] | A source of Pd(0). | Bypasses reduction step; used to study later stages of the catalytic cycle without complication from reduction. |

| PPh₃ [1] [15] | Archetypal monodentate phosphine ligand. | Benchmark ligand for mechanistic studies; well-understood reactivity and speciation. |

| DPPF / Dcypf [1] [17] | Bidentate phosphine ligands. | Study the effect of chelation and electron-donating ability on catalyst stability and activity. |

| XPhos / SPhos [1] | Bulky, electron-rich monophosphines. | Investigation of reactions involving challenging substrates (e.g., aryl chlorides); study of ligand steric effects. |

| Primary Alcohols (e.g., HEP) [1] | Reductants for controlled Pd(II) to Pd(0) conversion. | To study and optimize the pre-catalyst activation step while minimizing phosphine oxidation. |

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts [16] | Additives to generate cationic or anionic species. | Investigation of anionic pathways in transmetalation (e.g., in the Si-O-Pd bond mechanism). |

| Isolated Intermediates [18] [16] | Pre-formed, characterized organopalladium complexes. | Direct kinetic analysis of individual elementary steps (e.g., transmetalation, reductive elimination). |

The profound influence of ligands on the Pd(0)/Pd(II) cycle is a demonstrable and quantifiable phenomenon. As this guide has detailed through mechanistic diagrams, comparative data, and experimental protocols, ligand choice directly dictates the efficiency of pre-catalyst reduction, the rate of oxidative addition and transmetalation, and the facility of reductive elimination. No single ligand class is universally superior; rather, the optimal choice is dictated by the specific substrate pairing and the demands of the catalytic cycle's potential rate-determining step. The ongoing development of ligands—from traditional phosphines to modern bifunctional and N,O-based designs—continues to expand the frontiers of palladium-catalyzed synthesis. A deep, mechanistic understanding of ligand effects empowers researchers to make rational choices in catalyst design and reaction optimization, ultimately driving innovation in the synthesis of complex molecules.

In the field of transition-metal catalysis, which is pivotal to modern organic synthesis and pharmaceutical development, the choice of ligand is a critical determinant of catalyst performance. For decades, phosphines (PR₃) and cyclopentadienyls (Cp) were the dominant classes of tunable spectator ligands [19]. However, the rise of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) over the past two decades has established them as a third, privileged ligand class, leading to direct comparisons with phosphines regarding their electronic properties and stability [19] [20]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison between phosphines and NHCs, focusing on their σ-donor strengths and stability profiles—two fundamental parameters that profoundly influence their efficacy in catalytic cycles, particularly in cross-coupling reactions central to drug development.

Electronic Properties and σ-Donation

The bonding interaction between a ligand and a metal center is foundational to catalysis. A ligand's σ-donation capacity strengthens the metal-ligand bond and can modulate reactivity at the metal center.

Quantifying Ligand-Metal Interactions

Theoretical and experimental studies directly compare the bond energies and electronic effects of phosphines versus NHCs.

Table 1: Comparative Ligand Binding Energies (LBEs) for Group 11 Cations (ΔH at 298 K) [21]

| Ligand | Approximate LBE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| PH₃ | ~30 |

| PMe₃ | ~45 |

| PPh₃ | ~45-50 |

| NHC (Typical) | >50 |

Table 2: Electronic and Structural Parameters of Phosphines and NHCs [19] [20]

| Parameter | Tertiary Phosphines (e.g., PCy₃) | N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (NHCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Strong σ-donor, good π-acceptor | Very strong σ-donor, variable π-acceptor |

| Typical Bond Strength | Strong, but reversible | Stronger, often irreversible |

| Impact on Trans Ligand | Can be labilized | Can strengthen via enhanced π-back-donation |

Conflicting Effects of Strong NHC Donation

The strong σ-donation of NHCs has complex, sometimes opposing, effects on catalytic activity. While it can stabilize reactive intermediates and increase thermal stability, it can also inhibit catalyst initiation [20]. A prominent example is found in the second-generation Grubbs ruthenium catalysts for olefin metathesis. The strong σ-donation from the NHC ligand, unrelieved by significant π-backbonding in the case of unsaturated NHCs like IMes, leads to increased electron density at the ruthenium center. This enhances Ru→PCy₃ π-back-donation, thereby strengthening the Ru–P bond and making phosphine dissociation—the essential initiation step—slower by nearly an order of magnitude compared to the saturated H₂IMes analogue [20]. This demonstrates that strong donation is not universally beneficial and must be considered in the context of the specific catalytic mechanism.

Stability and Practical Handling

Beyond electronic properties, the stability of a ligand and its complexes under synthetic conditions dictates their practical utility.

Stability Profiles and Degradation Pathways

| Aspect | Tertiary Phosphines | N-Heterocyclic Carbenes |

|---|---|---|

| Air/Moisture Stability | Many are air-sensitive, prone to oxidation [1] | Complexes are often air- and moisture-stable [22] |

| Metal-Ligand Bond Stability | Reversible binding; can lead to ligand dissociation [19] | Often irreversible binding; can be cleaved under specific conditions [19] |

| Synthetic Accessibility | Wide commercial range; rich variety of chelate architectures [19] | Tunable core; challenges with metallation and chelation [19] |

Advanced Pre-catalyst Design

The superior stability of Pd(II)–NHC complexes has enabled the design of highly effective pre-catalysts. Among these, [Pd(NHC)(μ-Cl)Cl]₂ chloro dimers are recognized as some of the most reactive and stable Pd(II)–NHC pre-catalysts available [22]. These dimers are air- and moisture-stable, facilitating easy handling, yet they readily dissociate and are activated under mild basic conditions to generate the highly active monoligated Pd(0)–NHC species. This combination of operational stability and high reactivity makes them a premier choice for challenging cross-coupling reactions in complex molecular settings [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Reliable experimental data is essential for a meaningful comparison. This section outlines key methodologies for quantifying ligand properties and evaluating catalyst performance.

Quantifying Bond Energies via Theoretical Calculations

Objective: To determine accurate Ligand Binding Energies (LBEs) for phosphine and NHC complexes.

- Method: High-level computational studies using Density Functional Theory (DFT) and correlated molecular orbital theory (CCSD(T)) [21].

- Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: The ground-state structures of the metal-ligand complexes (e.g., with Group 11 cations) are optimized using DFT.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: More accurate electronic energies are computed for the optimized structures using the CCSD(T) method.

- LBE Calculation: The binding enthalpy (ΔH₂₉₈ₖ) is calculated as the enthalpy change for the reaction: M + L → M-L, where M is the metal fragment and L is the phosphine or NHC ligand.

- Benchmarking: Computational results are compared with available experimental data to validate the methodology [21].

Assessing Ligand Lability in Catalytic Complexes

Objective: To measure the kinetics of ligand dissociation, a critical step in catalyst initiation.

- Method: Kinetic analysis of phosphine dissociation from ruthenium methylidene complexes (GIIm) [20].

- Procedure:

- Complex Preparation: Isolate the well-defined methylidene complexes, such as s-GIIm (saturated NHC) and u-GIIm (unsaturated NHC).

- Decomposition Kinetics: Monitor the thermal decomposition of the complexes in solution (e.g., C₆D₆) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 85 °C) via NMR spectroscopy.

- Pathway Interrogation: Conduct the decomposition experiment in the presence of added free PCy₃. An unchanged decomposition rate indicates a dissociative mechanism (Scheme 1a), where loss of PCy₃ is the rate-determining step.

- Data Analysis: The first-order rate constants (k) for decomposition are directly related to the rate of PCy₃ loss, allowing for a direct comparison of phosphine lability between different NHC ligands [20].

Evaluating Pre-catalyst Reduction in Cross-Coupling

Objective: To control the in situ generation of active Pd(0) species from Pd(II) pre-cursors, avoiding ligand oxidation and reagent consumption.

- Method: Use of ³¹P NMR spectroscopy and DFT calculations to monitor the reduction process [1].

- Procedure:

- Standardized Setup: Combine a Pd(II) source (e.g., Pd(OAc)₂ or PdCl₂(ACN)₂) with the phosphine ligand (e.g., PPh₃, DPPF, XPhos) in a solvent like DMF.

- Controlled Reduction: Introduce a specific base (e.g., triethylamine, Cs₂CO₃) and a benign reducing agent, such as a primary alcohol (e.g., N-hydroxyethyl pyrrolidone, HEP), which reduces Pd(II) to Pd(0) without being consumed to form side products.

- Monitoring: Use ³¹P NMR to track the formation of Pd(0)-phosphine complexes and the absence of phosphine oxide signals, indicating successful reduction without ligand degradation.

- Optimization: Identify the optimal combination of counterion, ligand, base, and solvent that maximizes the yield of the active Pd(0) catalyst [1].

Visualization of Comparative Properties and Catalytic Behavior

The following diagrams summarize the key comparative properties and mechanistic behaviors of phosphine and NHC ligands.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This table details key reagents and materials essential for working with phosphine and NHC ligands in cross-coupling reactions, based on the experimental protocols cited.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions [19] [1] [22]

| Reagent/Material | Function & Description | Example Application/Note |

|---|---|---|

| [Pd(NHC)(μ-Cl)Cl]₂ Dimers | Air- and moisture-stable Pd(II)–NHC pre-catalysts. Highly reactive, readily activated under mild conditions. | The go-to pre-catalyst for many challenging cross-couplings; commercially available [22]. |

| Pd(OAc)₂ / PdCl₂(ACN)₂ | Common Pd(II) sources for in situ catalyst formation. PdCl₂(ACN)₂ is often more soluble and reactive. | Used with phosphines or for generating NHC complexes in situ [1]. |

| Buchwald Phosphines (SPhos, XPhos) | Bulky, electron-rich biaryl monophosphine ligands. Enhance reductive elimination and stabilize mono-ligated Pd(0). | Crucial for challenging C–N and C–C couplings; require controlled pre-catalyst reduction [1]. |

| Silver Oxide (Ag₂O) | A metallating agent for transferring NHCs to metals. Mild method to form M–NHC bonds from imidazolium salts. | Enables synthesis of NHC complexes, even in air/water, avoiding strong bases [19]. |

| N-Hydroxyethyl Pyrrolidone (HEP) | A benign reducing agent and co-solvent. Reduces Pd(II) to Pd(0) via oxidation of its primary alcohol group. | Prevents phosphine oxidation and unwanted reagent consumption during pre-catalyst activation [1]. |

| DPPF / Xantphos | Common bidentate phosphine ligands. Provide chelating effects and tunable bite angles, stabilizing Pd centers. | Used to study the effect of bidentate structure on pre-catalyst reduction and complex stability [1]. |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the choice between phosphines and N-heterocyclic carbenes is not a matter of simple superiority but of strategic selection based on the specific demands of a catalytic process. Phosphines offer a long-established, highly tunable platform with reversible binding, but can suffer from air sensitivity and oxidation under standard reaction conditions. NHCs provide superior σ-donation and form stable, often irreversible bonds with metals, leading to robust and air-stable pre-catalysts; however, this very strength can sometimes inhibit catalytic initiation. The conflicting effects of strong NHC donation mean that a deep understanding of the catalytic cycle—particularly the steps of activation and turnover—is essential for optimal ligand selection. Advanced pre-catalyst designs, such as Pd–NHC chloro dimers, effectively leverage the stability of NHCs while ensuring efficient activation. For researchers in drug development and synthetic chemistry, this guide underscores that mastering both ligand classes and their associated experimental protocols is key to solving the complex challenges of modern cross-coupling chemistry.

Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions represent a cornerstone of modern organic synthesis, enabling the construction of carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bonds with high efficiency and selectivity. These transformations are indispensable in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical industries for assembling complex molecular architectures. While numerous pre-formed palladium complexes are available, the in situ generation of active Pd(0) species from Pd(II) precursors remains a widely adopted approach in both academic and industrial settings due to its practicality and cost-effectiveness [1]. This methodology involves combining stable, readily available Pd(II) salts with appropriate ligands directly in the reaction mixture.

However, the transition from Pd(II) pre-catalysts to the active Pd(0) species presents significant challenges that can profoundly impact reaction outcomes. Inefficient reduction can lead to diminished catalytic activity, increased catalyst loading, and the formation of undesired byproducts [1]. This guide examines the critical challenges associated with in situ Pd(0) formation and provides evidence-based strategies for optimizing this process, with a particular focus on ligand comparison within cross-coupling research.

Fundamental Challenges in In Situ Pd(0) Formation

The pathway from Pd(II) pre-catalysts to active Pd(0) species is fraught with potential complications that can compromise catalytic efficiency. Understanding these challenges is essential for developing effective catalytic systems.

Uncontrolled Reduction Pathways

A primary challenge lies in controlling the reduction process itself. The common practice of simply mixing Pd(II) salts, ligands, and substrates under standard reaction conditions does not guarantee the efficient formation of the intended active Pd(0)L~n~ species [1]. The reduction can proceed through competing pathways:

- Phosphine Oxidation: Phosphine ligands, crucial for stabilizing Pd(0), can be consumed through oxidation to phosphine oxides, altering the critical ligand-to-metal ratio and compromising catalyst structure and stability [1]. This is particularly problematic with chiral bidentate phosphines where ligand oxidation destroys chirality transfer.

- Substrate Consumption: Alternatively, reduction can occur at the expense of coupling partners, leading to reagent degradation and the formation of impurity profiles that complicate purification processes [1]. On an industrial scale, this consumption of expensive molecular fragments represents a significant efficiency and cost issue.

Ligand Oxidation and Stability

The stability of ligands under catalytic conditions is frequently overlooked. Even ligands considered "oxidatively stable" can undergo degradation during catalysis. For instance, in Pd(II)-catalyzed aerobic oxidations, N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands can be oxidized by Pd(II)-hydroperoxide species, leading to catalyst deactivation [23]. Similarly, phosphine ligands are susceptible to oxidation during the pre-catalyst activation step, especially when the reduction process is not carefully controlled [1].

Formation of Inactive Species and Nanoparticles

Inefficient reduction can lead to the formation of catalytically inactive species or palladium nanoparticles. Waymouth and co-workers observed the formation of a catalytically inactive Pd(II)-alkoxide complex during alcohol oxidation, which originated from the reaction of the Pd(II)-hydroperoxide intermediate with the ligand [23]. Furthermore, certain catalytic systems, particularly those involving sulfur-ligated palladacycles, can decompose to form Pd nanoparticles under reaction conditions [24]. While these nanoparticles can sometimes serve as active catalysts, their formation represents a deviation from the intended homogeneous catalytic pathway and can lead to inconsistent results and reproducibility issues.

Strategic Approaches to Controlled Pd(0) Formation

Recent research has elucidated several strategies to overcome the challenges associated with in situ Pd(0) formation. The core principle involves carefully balancing the palladium source, ligand, base, and solvent to favor efficient and selective reduction.

Ligand-Specific Reduction Protocols

A landmark study by Fantoni et al. demonstrated that optimal reduction protocols are highly dependent on the specific ligand employed [1]. Their systematic investigation revealed that the correct combination of counterion, ligand, and base allows for perfect control of the Pd(II) to Pd(0) reduction in the presence of primary alcohols. The following table summarizes their key findings for various ligand classes:

Table 1: Ligand-Specific Reduction Conditions for Efficient Pd(0) Formation

| Ligand Class | Ligand Example | Recommended Pd Source | Recommended Base | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monodentate Phosphines | PPh~3~ | Pd(OAc)~2~ | TMG | Avoids phosphine oxidation |

| Bidentate Phosphines | DPPF, DPPP | PdCl~2~(ACN)~2~ | TEA | Chloride counterion preferred |

| Large Bite-Angle Phosphines | Xantphos | Pd(OAc)~2~ | TEA | Requires THF as solvent |

| Buchwald-type Phosphines | SPhos, RuPhos, XPhos | Pd(OAc)~2~ | TMG | Primary alcohols as reductants |

This ligand-dependent specificity underscores the importance of tailored approaches rather than one-size-fits-all methodologies. For instance, while Pd(OAc)~2~ works well with many ligands, bidentate phosphines like DPPF perform better with PdCl~2~(ACN)~2~ [1]. The use of primary alcohols, such as N-hydroxyethyl pyrrolidone (HEP), as stoichiometric reductants provides a controlled reduction pathway that minimizes side reactions and prevents nanoparticle formation by maintaining the correct metal/ligand ratio [1].

The Role of Ligand Design in Stabilizing Active Species

Ligand design plays a pivotal role in not only facilitating reduction but also in stabilizing the resulting Pd(0) species and controlling its catalytic activity. For example, the use of sulfur-containing Schiff base ligands can lead to the formation of stable palladacycles that serve as pre-catalysts, decomposing under reaction conditions to release active Pd species, often in the form of nanoparticles [24]. While this demonstrates an alternative activation pathway, the formation of defined Pd(0) complexes is often preferred for reproducibility.

In nickel-catalyzed reactions, ligand geometry exerts profound control over catalytic pathways. A study on Ni-catalyzed sulfuration showed that planar bidentate ligands like 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline promote a NiI/NiIII cycle, while non-planar ligands like 6,6′-dimethyl-2,2′-dipyridyl lead to a Ni0/NiII/NiI cycle [25]. This principle translates to palladium catalysis, where ligand sterics and electronics can direct reaction pathways and stabilize intermediate species.

Comparative Experimental Data and Protocols

Performance Comparison of Ligand Systems

The efficiency of different ligand systems in facilitating in situ Pd(0) formation directly correlates with their performance in cross-coupling reactions. The following table compiles experimental data from recent studies, highlighting the critical role of optimized reduction conditions:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Pd Catalytic Systems in Cross-Coupling Reactions

| Catalyst System | Reaction Type | Key Performance Metric | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd(SPhos) from Pd(OAc)~2~/TMG/HEP | HCS & Suzuki-Miyaura | High yield, avoids substrate dimerization | Controlled reduction in DMF/HEP | [1] |

| S-ligated Palladacycle | Suzuki-Miyaura & Sonogashira | High yields with aryl chlorides/bromides (0.01-0.05 mol% Pd) | Forms Pd nanoparticles in situ | [24] |

| Pd-PPh~3~ from Pd(OAc)~2~ | Aminocarbonylation | 81% yield in amide formation | Photoinduced, two-chamber reactor | [26] |

| Pd-bpy from Pd(OAc)~2~ | Aminocarbonylation | 84% yield (improved over PPh~3~) | Photoinduced, two-chamber reactor | [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Controlled Reduction with SPhos

The following optimized protocol for generating active Pd(0) from Pd(OAc)~2~ and SPhos exemplifies the principles of controlled pre-catalyst reduction [1]:

- Reaction Setup: Conduct reactions under an inert atmosphere (N~2~ or Ar) using standard Schlenk techniques.

- Solvent System: Use anhydrous DMF containing 30% v/v N-hydroxyethyl pyrrolidone (HEP) as a co-solvent.

- Activation Sequence:

- Charge the reaction vessel with Pd(OAc)~2~ (1 mol%) and SPhos (2-2.2 mol%).

- Add the solvent mixture (DMF/HEP).

- Add TMG (N,N,N',N'-tetramethylguanidine, 1.5 equiv relative to Pd).

- Stir the mixture at room temperature for 15-30 minutes to generate the active Pd(0) species. The solution typically darkens during this activation period.

- Subsequently add the coupling partners and base to initiate the cross-coupling reaction.

- Key Considerations: The HEP co-solvent acts as a sacrificial primary alcohol, facilitating reduction while simplifying product isolation compared to other alcohol solvents. The TMG base is crucial for promoting clean reduction without phosphine oxidation.

This methodology, when applied to Heck-Cassar-Sonogashira and Suzuki-Miyaura reactions, maximizes the formation of the targeted Pd(0) catalyst, prevents substrate consumption, and suppresses nanoparticle formation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful in situ Pd(0) formation requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components and their functions in the catalyst activation process:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for In Situ Pd(0) Formation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pd(OAc)~2~ | Pd(II) pre-catalyst source | Stable, cost-effective; forms monomeric species in solution [1] |

| PdCl~2~(ACN)~2~ | Pd(II) pre-catalyst source | Alternative to PdCl~2~; improved solubility [1] |

| Buchwald-type Ligands (SPhos, XPhos) | Ligand for Pd(0) stabilization | Electron-rich, bulky; require specific reduction protocols [1] |

| Bidentate Phosphines (DPPF, Xantphos) | Ligand for Pd(0) stabilization | Form chelates; chloride counterion often preferred [1] |

| N-Hydroxyethyl Pyrrolidone (HEP) | Sacrificial reductant & co-solvent | Primary alcohol facilitates controlled reduction; simplifies workup [1] |

| TMG (Tetramethylguanidine) | Strong organic base | Promotes reduction via alkoxide formation; ligand-dependent efficacy [1] |

| TBADT (Tetrabutylammonium Decatungstate) | Photocatalyst for radical generation | Enables alternative reduction pathways in dual catalytic systems [26] |

Mechanistic Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The journey from Pd(II) pre-catalyst to active Pd(0) species involves a series of coordinated steps. The following diagram visualizes this mechanistic workflow, highlighting key intermediates, potential pitfalls, and strategic control points.

In Situ Pd(0) Formation Workflow

This mechanistic map illustrates the critical branching points where improper conditions lead to deactivation pathways (red nodes), while strategic interventions (blue nodes) steer the system toward the desired active Pd(0) species (green node).

The controlled in situ formation of Pd(0) catalysts from Pd(II) precursors remains a dynamic area of research with significant implications for synthetic efficiency and sustainability. The evidence presented demonstrates that successful catalyst activation requires moving beyond simple "mix-and-react" approaches to embrace carefully designed, ligand-specific reduction protocols. The strategic use of primary alcohols as reductants, combined with optimized base and counterion selection, provides a robust framework for generating active Pd(0) species while minimizing deleterious side reactions.

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on several key areas: the development of more oxidatively stable ligand architectures, a deeper mechanistic understanding of reduction pathways through advanced in situ and operando techniques [27], and the design of catalytic systems that bridge the gap between homogeneous and nanoparticle catalysis. As the field progresses, the systematic approach to pre-catalyst activation outlined in this guide will serve as a foundation for developing more efficient, reproducible, and sustainable cross-coupling methodologies for pharmaceutical and agrochemical applications.

Advanced Ligand Systems and Their Application in Modern Synthesis

Dialkylbiarylphosphines represent a cornerstone class of ligands in modern palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, most notably the Buchwald-Hartwig amination. Their development successfully addressed two critical challenges in industrial and academic applications: achieving high catalytic activity and maintaining robust air stability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these ligands against other prominent ligand classes, detailing the design principles that enable their unique performance. Supported by experimental data and protocols, it serves as a reference for researchers and development professionals in selecting optimal ligands for C-N bond formation in complex settings, such as drug discovery and materials science.

The advent of palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling, particularly for C-N bond formation via the Buchwald-Hartwig reaction, has revolutionized synthetic organic chemistry. The efficacy of these catalytic systems is singularly dependent on the supporting ligand, which stabilizes the palladium center and facilitates the elementary steps of the catalytic cycle [28] [29]. Early ligands, particularly triarylphosphines like PPh₃, often suffered from low activity, poor functional group tolerance, and rapid decomposition under ambient conditions [28].

The introduction of dialkylbiarylphosphines by Buchwald and coworkers marked a paradigm shift [29]. These ligands were rationally designed to confer high catalytic activity while being stable enough to be handled in air, a combination that had previously been elusive. This review objectively compares the performance of these privileged ligands with other alternatives, including other phosphines and N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), providing a data-driven resource for the scientific community.

Design Principles and Comparative Analysis

Architectural Features of Dialkylbiarylphosphines

Dialkylbiarylphosphines are characterized by a specific molecular architecture that underpins their performance. The design incorporates a biaryl backbone that creates a large, electron-donating, and sterically hindered environment around the palladium center. Key design elements include:

- Bulky Dialkyl Groups: Substituents like cyclohexyl (

Cy) or tert-butyl (tBu) on the phosphorus atom provide strong electron-donating capacity, facilitating the critical oxidative addition step of less reactive aryl chlorides. The steric bulk also promotes the formation of highly active monoligated Pd(0) species,L·Pd(0)`, crucial for catalytic efficiency [29] [30]. - Biphenyl Backbone: This rigid structure, often with substituents at the 2' and 6' positions (ortho to the phosphorus), enforces a specific geometry that shields the metal center and creates a "hydrophobic pocket," enhancing selectivity and stability [30].

- Modular Tuning: The backbone and alkyl groups can be systematically varied, leading to a library of ligands (e.g., BrettPhos, RuPhos, SPhos, XPhos) optimized for specific substrate classes and reaction types [31] [30].

Quantitative Performance Comparison with Other Ligand Classes

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing dialkylbiarylphosphines to other common ligand classes in the Buchwald-Hartwig amination.

Table 1: Comparison of ligand classes in the amination of aryl chlorides with aniline [28].

| Ligand Class | Specific Ligand | Time (h) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triarylphosphines | PPh₃ | 42 | 37 |

| Bidentate Phosphines | dppf | 36 | 66 |

| Dialkylbiarylphosphines | BrettPhos | 12 | >95 [30] |

| N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (NHCs) | IPr·HCl | 36 | 67 |

Table 2: Ligand selection guide for different nucleophile classes in Buchwald-Hartwig coupling [30].

| Nucleophile Class | Recommended Dialkylbiarylphosphine | Typical Performance (Yield %) | Superiority Over Alternative Ligands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Alkyl Amines | BrettPhos | >90 [30] | Higher selectivity for monoarylation vs. bidentate phosphines. |

| Secondary Cyclic Amines | RuPhos | >90 [30] | Faster rates and lower catalyst loadings compared to triarylphosphines. |

| Aryl Amines / Anilines | BrettPhos / XPhos | >85 [30] | Broader scope for sterically hindered anilines vs. early-generation NHCs. |

| Amides | tBuBrettPhos | >80 [31] | Unique ability to activate less nucleophilic amides, where other ligands fail. |

| Heteroaryl Amines (Indole) | DavePhos | >85 [31] | Superior performance with N-H heterocycles compared to monodentate phosphines. |

The Air Stability Advantage

A defining practical advantage of dialkylbiarylphosphines over other electron-rich phosphines like tricyclohexylphosphine (PCy₃) or tri-tert-butylphosphine (P(tBu)₃) is their air stability. While the latter are highly air-sensitive pyrophoric solids requiring glove-box handling, dialkylbiarylphosphines are typically stable, crystalline solids that can be weighed on the benchtop [29] [30]. This stability stems from the steric shielding of the phosphorus atom by the ortho-substituted biaryl backbone, which kinetically impedes oxidation. This feature drastically simplifies their use in industrial and academic settings, reducing both operational complexity and cost.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Reaction Setup: In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, an oven-dried vial was charged with Pd₂(dba)₃ (2.5 mol% Pd), BrettPhos (10 mol%), and Cs₂CO₃ (1.5 equiv). The vial was sealed with a septum cap and removed from the glovebox. Reaction: Aryl chloride (1.0 equiv) and amine (1.2 equiv) were added via syringe, followed by anhydrous toluene (0.5 M). The reaction mixture was stirred at 100 °C and monitored by TLC or LC-MS. Work-up: After completion, the reaction was cooled to room temperature, diluted with ethyl acetate, and filtered through a short pad of Celite. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification: The crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired arylamine product.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Buchwald-Hartwig Amination

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Palladium Precursors (e.g., Pd₂(dba)₃, Pd(OAc)₂) | Source of palladium. Pd₂(dba)₃ is common for in-situ catalyst formation; pre-formed Pd-phosphine complexes offer more reproducibility [30]. |

| Dialkylbiarylphosphine Ligands (e.g., BrettPhos, RuPhos) | The ligand defines catalyst activity and stability. It facilitates all key steps in the catalytic cycle: oxidative addition, deprotonation, and reductive elimination [31] [30]. |

| Strong Bases (e.g., NaOtBu, LiHMDS) | Essential for deprotonating the amine nucleophile, generating the amine anion that attacks the Pd center [31] [30]. |

| Weak Bases (e.g., Cs₂CO₃, K₃PO₄) | Used for base-sensitive substrates. Particle size and agitation can significantly impact reaction rate in slurries [30]. |

| Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Toluene, 1,4-Dioxane) | Common solvents with good heating profiles. Coordinating solvents like DMF or MeCN can inhibit the catalyst by binding to Pd [30]. |

Catalytic Cycle and Ligand Role

The following diagram illustrates the general catalytic cycle of the Buchwald-Hartwig amination, highlighting the critical role played by the dialkylbiarylphosphine ligand (L) in each step. The strong electron-donating and sterically bulky nature of the ligand promotes the formation of the active L·Pd(0) species, facilitates oxidative addition, and enables the final reductive elimination to form the C-N bond [31] [30].

Diagram: Catalytic cycle of Buchwald-Hartwig amination facilitated by dialkylbiarylphosphine ligands (L).

Dialkylbiarylphosphines have firmly established themselves as a premier ligand class for Buchwald-Hartwig amination and other cross-coupling reactions. Their rationally designed structure strikes a optimal balance between high catalytic activity—enabling the coupling of challenging substrate pairs like aryl chlorides and sterically hindered amines—and excellent air stability, which is critical for practical application. While other ligands, such as N-heterocyclic carbenes, excel in specific niches, the versatility, predictable performance, and commercial availability of dialkylbiarylphosphines like BrettPhos, RuPhos, and XPhos make them the default choice for a wide range of C-N bond-forming applications in pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis.

The cross-coupling of unactivated aryl chlorides represents a significant challenge in modern organic synthesis, particularly for pharmaceutical and agrochemical applications where complex biaryl structures are prevalent. Aryl chlorides are particularly attractive industrial substrates due to their lower cost and wider commercial availability compared to their bromide and iodide counterparts. However, their inherent lack of reactivity, stemming from stronger carbon-chloride bonds and higher activation barriers for oxidative addition, has historically necessitated the development of specialized catalyst systems. The strategic implementation of bulky and electron-rich ligands has emerged as a cornerstone solution to this challenge, enabling the activation of these recalcitrant substrates under practical conditions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of ligand platforms that facilitate these demanding transformations, examining their performance across different metal catalysts and reaction types to inform researcher selection and application.

Comparative Analysis of Ligand Frameworks

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of major ligand classes in cross-couplings of unactivated aryl chlorides, highlighting their distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ligand Classes with Unactivated Aryl Chlorides

| Ligand Class | Specific Example | Metal Catalyst | Reaction Type | Reported Yield (%) | Key Reaction Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (NHCs) | 1,3-Dimesitylimidazol-2-ylidene (IMes) | FeBr3 | Suzuki Biaryl Coupling [32] | 24-98% (substrate-dependent) | Requires organolithium-activated boronic esters |

| Arsine Ligands | Triphenylarsine (AsPh3) | Pd/NBE Cooperative | C–H Difunctionalization [33] | 58-65% | Outperforms all tested phosphines |

| Bulky Alkylphosphines | Tricyclohexylphosphine (PCy3) | Ni(COD)2 | Suzuki-Miyaura [34] | 74-95% | Effective at room temperature |

| Standard Triarylphosphines | Triphenylphosphine (PPh3) | Ni(COD)2 | Suzuki-Miyaura [34] | 80-98% | Room temperature, cost-effective |

| Biimidazoline (BiIM) Ligands | Chiral BiIM L1 | Ni/Electrochemical | Reductive Cross-Coupling [35] | 45-89% | Enantioselective, uses electrochemical reductant |

Ligand Property and Performance Relationship

The efficacy of a ligand in activating aryl chlorides is governed by a balance of its steric bulk and electronic donor properties. The following table parameterizes key ligands to illustrate these structure-activity relationships.

Table 2: Steric and Electronic Parameters of Representative Ligands

| Ligand | Tolman Electronic Parameter (TEP, cm⁻¹) [a] | Cone Angle (degrees) | % Buried Volume (%Vbur) | Optimal Property for Aryl Chloride Activation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AsPh3 (Arsine) [33] | ~2067-2075 | 158-160 | 22.7-22.9 | Moderate σ-donation, low steric shielding |

| PPh3 (Standard Phosphine) [34] | 2068.9 | 145 | 25.4 | Less bulky, suitable for Ni-catalyzed systems |

| PCy3 (Bulky Alkylphosphine) [34] | 2056.1 | 170 | 31.2 | Strong σ-donation, high steric bulk |

| IMes (NHC) [32] | N/A [b] | N/A [b] | N/A [b] | Extremely strong σ-donation, poor π-acceptance |

[a] A lower TEP indicates a stronger electron-donating ability. [b] NHCs are not typically characterized by Tolman parameters. They are generally considered stronger σ-donors than even the most electron-rich phosphines.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Iron-Catalyzed Suzuki Coupling with NHC Ligands

The following protocol, adapted from a recent Nature Catalysis study, enables the traditionally challenging iron-catalyzed Suzuki biaryl coupling of aryl chlorides [32].

- Reaction Setup: Conduct reactions in a dry, inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) using standard Schlenk line or glovebox techniques.

- Catalyst System: Utilize FeBr₃ (5-10 mol%) and the NHC ligand IMes (5-10 mol%). The NHC ligand can be generated in situ from its imidazolium salt precursor.

- Activation: A key step is the activation of the boronic ester partner. Treat the aryl boronic ester (1.5-2.0 equiv) with tert-butyllithium (t-BuLi) (1.5-2.0 equiv) at low temperature (-78 °C) prior to coupling. This forms a more reactive boronate complex.

- Additives: MgBr₂ (additive, role not fully defined) and MeMgBr (1 equiv per Fe, acts as an activator for the NHC precursor) are essential for high yield [32].

- Coupling Reaction: Add the activated boronate to a mixture of the aryl chloride (1.0 equiv), iron catalyst, and additives.

- Solvent and Conditions: Use a 1:1 mixture of 1,4-dioxane and 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran. Heat the reaction mixture to 100 °C with vigorous stirring for several hours.

- Analysis: Monitor reaction progress by GC-MS, TLC, or LC-MS. Purify the crude product via flash column chromatography to isolate the desired biaryl product and remove homo-coupled by-products.

Nickel-Electrochemical Reductive Cross-Coupling

This protocol describes an enantioselective method for coupling aryl halides with benzyl chlorides, leveraging electrochemistry as a clean reductant [35].

- Electrochemical Cell: Perform reactions in an undivided cell equipped with a Nickel foam cathode and a Platinum plate anode.

- Catalyst System: Employ NiBr₂•glyme (10 mol%) and a chiral Biimidazoline (BiIM) ligand (L1) (10-12 mol%).

- Reaction Mixture: Combine the benzyl chloride (1.0 equiv) and aryl halide (1.2-1.5 equiv) in a mixed solvent system of DMAc:THF (1:45). Add triethylamine as a base and terminal reductant. 4 Å molecular sieves are added as a desiccant to enhance enantioselectivity.

- Electrolysis: Apply constant current electrolysis (specific current density optimized) at room temperature for the required duration (typically 12-24 hours).

- Work-up and Analysis: Quench the reaction and extract the organic product. Determine yield and enantiomeric excess (ee) by chiral HPLC or SFC analysis.

Catalyst Design and Reaction Pathways

The synergy between a metal center and its ligand is crucial for facilitating the key steps in cross-coupling. The following diagram illustrates the core design principles and mechanistic roles of bulky, electron-rich ligands.

Diagram 1: Ligand Function in Cross-Coupling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Cross-Coupling of Aryl Chlorides

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ni(COD)₂ (Bis(cyclooctadiene)nickel(0)) | Zero-valent nickel precursor for catalyst formation. | Room temperature Suzuki couplings with PPh3 [34]. Air-sensitive, requires inert handling. |

| FeBr₃ / FeBr₂ | Earth-abundant, cost-effective iron catalyst precursor. | Suzuki biaryl coupling with NHC ligands; purity is critical [32]. |

| IMes·HCl (1,3-Bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazolium chloride) | NHC precursor ligand; strong σ-donor. | In situ deprotonation with base (e.g., MeMgBr) generates active Fe-NHC catalyst [32]. |

| Chiral BiIM Ligands (e.g., L1) | Chiral bidentate nitrogen ligands for enantiocontrol. | Enantioselective Ni-electrochemical reductive cross-couplings [35]. |

| t-BuLi (tert-Butyllithium) | Strong base for organometallic synthesis and boronate activation. | Activates aryl boronic esters prior to transmetallation in Fe-catalyzed Suzuki [32]. |

| MgBr₂ | Lewis acidic halide additive. | Enhances reaction rate and yield in Fe-catalyzed Suzuki; specific role under investigation [32]. |

| Triethylamine | Base and terminal reductant in electrochemical setups. | Replaces sacrificial metal powders (e.g., Mn, Zn) in electrochemical reductive couplings [35]. |

The development of cross-coupling reactions for unactivated aryl chlorides continues to be a dynamic field, driven by ligand design. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that no single ligand class is universally superior; rather, the optimal choice is dictated by the specific metal catalyst, reaction type, and desired selectivity. While bulky alkylphosphines like PCy3 remain a powerful tool, particularly for palladium and nickel catalysis, the emergence of NHCs has been pivotal for enabling unprecedented transformations with base metals like iron. Furthermore, niche ligand families such as arsines offer unique steric and electronic profiles that can unlock reactivity inaccessible to traditional phosphines. A key contemporary trend is the integration of these advanced ligand systems with alternative energy inputs, such as electrochemistry, to provide more sustainable and selective synthetic pathways. As ligand design evolves, focusing on finer control of steric accessibility, electronic tuning, and integration with heterogeneous and earth-abundant metal systems, the synthetic toolbox for tackling unreactive substrates like aryl chlorides will continue to expand, offering researchers ever more powerful and selective methods for complex molecule construction.

The field of synthetic organic chemistry is undergoing a paradigm shift, driven by the demand for more complex, three-dimensional chemical architectures, particularly in drug discovery. Molecules with a higher fraction of sp3-hybridized carbons are associated with improved clinical success rates, yet their synthesis presents significant challenges due to the inert nature of C(sp3)–H bonds and the propensity for undesired side reactions in alkyl electrophiles [36] [37]. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern ligand-enabled strategies that are overcoming these historical limitations. We focus on two interconnected frontiers: the catalytic functionalization of unactivated sp3-hybridized electrophiles and the generative design of novel 3D molecular structures. By comparing experimental data and providing detailed protocols, this review serves as a benchmark for researchers selecting ligand systems for cross-coupling reactions and for scientists exploring the expanding chemical space for drug development.

Ligand Systems for sp3-Rich Electrophile Coupling

The engagement of unactivated secondary alkyl halides in cross-coupling reactions has been notoriously difficult, often plagued by sluggish oxidative addition and facile β-hydride elimination. Advanced ligand systems have emerged as the key to controlling reactivity and selectivity in these transformations.

Performance Comparison of Ligand-Enabled Catalytic Systems

The table below summarizes the performance of distinct ligand platforms in enabling cross-couplings with challenging sp3-hybridized electrophiles.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Ligand Systems for sp3-Hybridized Electrophile Cross-Coupling

| Catalytic System | Ligand Architecture | Reaction Type | Key Achievement | Reported Yield/Scope | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-based Multiligand [38] | NHC (e.g., NHC-1) + Phenanthroline (e.g., L6) | Hiyama Coupling | Coupling of arylsilanes with unactivated secondary alkyl bromides | Up to 72% yield; tolerant of cyclic & acyclic 2° alkyl halides | Multiligand relay: NHC enables C(sp²)–Si transmetallation; Phen handles C(sp³) radical capture & C–C bond formation |

| Ni-catalyzed Chain-Walking [36] | N-Heterocyclic Carbenes (e.g., IMes, IPr) | Regiodivergent Alkyl–Heteroaryl Coupling | Control over benzylic vs. terminal C(sp³)–H functionalization from same precursor | Excellent regioselectivity for linear (IPr) or branched (IMes) products | Ligand bulk controls rate of chain-walking: bulky ligands (IPr*OMe) interrupt, less bulky (IMes) allow rapid isomerization |

| Ni-catalyzed Chain-Walking [36] | Substituted 1,10-Phenanthrolines (e.g., L2) | Carboxylation of Alkyl Bromides | Regiodivergent synthesis of linear or α-branched carboxylic acids with CO₂ | Formation of all-carbon quaternary centers (e.g., 10d) | Temperature and ligand-substrate interactions dictate site-selectivity via "interrupted" chain-walking |