Machine Learning Guided Reaction Optimization: Transforming Drug Synthesis and Pharmaceutical Development

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing chemical reactions for drug synthesis and pharmaceutical research.

Machine Learning Guided Reaction Optimization: Transforming Drug Synthesis and Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in optimizing chemical reactions for drug synthesis and pharmaceutical research. It covers foundational AI concepts, key methodologies like retrosynthetic analysis and reaction prediction, and their practical integration with high-throughput experimentation. The content addresses critical challenges such as data scarcity and model selection, while providing comparative analysis of optimization algorithms and validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements to enable more efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective pharmaceutical development processes.

The AI Revolution in Chemical Synthesis: From Traditional Methods to Machine Learning Paradigms

Limitations of Traditional Trial-and-Error Synthesis Approaches

Within drug discovery and development, the synthesis of novel biologically active compounds is a foundational activity. The traditional approach to reaction development and optimization has historically relied on a trial-and-error methodology, guided by chemist intuition and manual experimentation. While this approach has yielded success, it presents significant limitations in efficiency, scalability, and the ability to navigate complex chemical spaces. This document details these limitations and frames them within the modern context of machine learning (ML)-guided reaction optimization research, providing application notes and protocols for researchers seeking to overcome these challenges.

Core Limitations of the Traditional Approach

The traditional trial-and-error method is characterized by iterative, sequential experimentation, where the outcomes of one experiment inform the design of the next. The primary constraints of this paradigm are summarized in the table below and elaborated in the subsequent sections.

Table 1: Quantitative and Qualitative Limitations of Traditional Trial-and-Error Synthesis

| Limitation Category | Key Challenges | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Data Inefficiency | Relies on small, localized datasets; knowledge does not systematically accumulate across different reaction families [1]. | Slow exploration of chemical space; high risk of missing optimal conditions. |

| Time and Resource Intensity | Manual, labour-intensive processes; slow iteration cycles [2]. | Extended timelines for hit identification and lead optimization; high material and labour costs. |

| Subjective and Bounded Exploration | Unintentionally bounded by the current body of chemical understanding; prone to human cognitive biases [1]. | Failure to discover novel, high-performing reaction conditions or scaffolds. |

| Scalability and Reproducibility | Difficulty in systematically exploring vast parameter spaces (catalyst, solvent, temperature, etc.); reproducibility challenges [3]. | Inefficient optimization; poor transferability of conditions between different but related synthetic problems. |

Data Inefficiency and the "Small Data" Problem

Expert chemists typically work with a small number of highly relevant data points—often from a few literature reports—to devise initial experiments for a new reaction space [1]. While effective for specific problems, this "small data" approach limits the ability to exploit information from large, diverse chemical databases. The knowledge gained from one reaction family often does not transfer quantitatively to another, creating a data bottleneck that hinders the rapid development of new synthetic methodologies [1].

Time and Resource Consumption

Traditional methods are inherently slow and labour-intensive. The manual process of setting up reactions, isolating products, and analysing results creates a significant bottleneck. This is in stark contrast to automated, predictive workflows that can significantly accelerate the optimization of chemical reactions [2]. In a field where the number of plausible reaction conditions is immense due to the combinations of components like catalysts, ligands, and solvents, this manual process is a major constraint on efficiency [1].

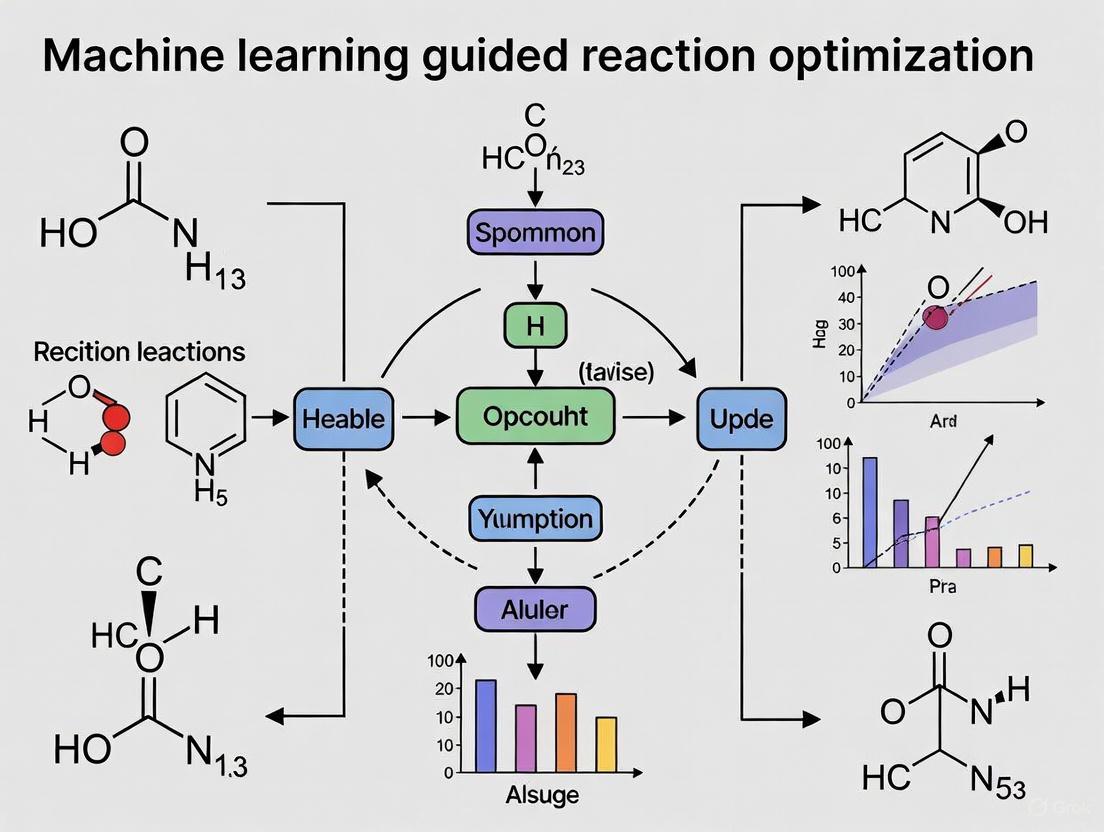

Machine Learning-Guided Solutions and Experimental Strategies

The limitations of traditional synthesis have catalyzed the development of ML-guided strategies. These approaches leverage large datasets, automation, and computational power to create a more efficient and effective discovery process. The following workflow illustrates the core components of an ML-guided optimization cycle, integrating both computational and experimental elements.

Foundational ML Strategies for Reaction Optimization

Two key ML strategies, transfer learning and active learning, are particularly suited to address the "small data" problem inherent in laboratory research [1].

Protocol 1: Implementing Transfer Learning for Reaction Yield Prediction

- Objective: To leverage knowledge from a large, general reaction database (source domain) to build a predictive model for a specific, data-poor reaction class (target domain).

- Materials:

- Methodology:

- Pre-train a Base Model: Train a model (e.g., a Transformer neural network) on the large source dataset to predict general reaction outcomes or yields [1].

- Fine-tune on Target Data: Use the small, focused target dataset to further train (fine-tune) the pre-trained model. This process adapts the model's general knowledge to the specific nuances of the target reaction class [1].

- Validation: Validate the fine-tuned model's performance on a held-out test set of reactions from the target family. Performance is typically superior to models trained only on the source or only on the small target dataset [1].

Protocol 2: Active Learning for Closed-Loop Reaction Optimization

- Objective: To iteratively and efficiently guide experimentation towards optimal reaction conditions by allowing the ML model to select the most informative experiments to run next.

- Materials:

- Initial Dataset: A small seed dataset of experiments.

- Automated Experimentation Platform: High-throughput experimentation (HTE) system [2].

- ML Model: A probabilistic model capable of quantifying prediction uncertainty.

- Methodology:

- Initial Model Training: Train an initial model on the seed dataset.

- Prediction and Prioritization: The model predicts outcomes for a vast number of possible reaction conditions within a defined search space. It prioritizes experiments where it is most uncertain or where the predicted payoff is highest (e.g., high yield).

- Automated Execution: The top-prioritized experiments are automatically executed by the HTE system [2].

- Iterative Update: The results from the new experiments are added to the training dataset, and the model is retrained. This closed-loop cycle continues until performance targets are met.

Integration with High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)

The synergy of ML and HTE is critical for transforming the traditional workflow. HTE provides the rapid data generation capability required to feed ML models, creating a virtuous cycle of data acquisition and model improvement [2].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ML/HTE-Driven Synthesis

| Item / Solution | Function in ML-Guided Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening Kits | Pre-formatted plates containing diverse catalysts, ligands, and bases to rapidly explore chemical space [2]. |

| Automated Liquid Handling Systems | Enable precise, miniaturized, and parallel setup of hundreds to thousands of reaction conditions for data generation [2]. |

| Reaction Representation Software | Converts chemical structures and conditions into numerical descriptors (e.g., fingerprints, SELFIES) that ML models can process [3]. |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | Provide scalable computational resources for training large ML models on extensive reaction databases [4]. |

Case Studies and Impact Assessment

The application of ML-guided strategies has demonstrated tangible improvements over traditional methods.

- Case Study 1: A retrospective study on Buchwald-Hartwig C–N coupling reactions showed that models built using entire reaction datasets outperformed those built on narrower, more specific data, highlighting the value of integrated data for certain reaction classes [1].

- Case Study 2: In a prospective application, the integration of ML and HTE enabled the autonomous optimization of complex chemical reactions, drastically reducing the number of experiments and time required to identify optimal conditions compared to a manual approach [2].

The logical relationship between the problems of traditional synthesis and the solutions offered by modern ML approaches is summarized in the following diagram.

Traditional trial-and-error synthesis, while foundational, is fundamentally limited by its data inefficiency, slow pace, and inherent biases. These limitations create significant bottlenecks in the drug discovery pipeline. The emerging paradigm of machine learning-guided optimization, particularly when integrated with high-throughput experimentation, offers a powerful solution set. By leveraging strategies like transfer learning and active learning, researchers can overcome the "small data" problem, systematically explore vast reaction spaces, and accelerate the development of synthetic routes, ultimately contributing to the more efficient discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized pharmaceutical research, directly addressing critical challenges of efficiency, scalability, and predictive accuracy. Traditional drug discovery is characterized by extensive timelines, often exceeding 14 years, and costs averaging $2.6 billion per approved drug, with high attrition rates in clinical phases [5] [6]. AI technologies are projected to generate between $350 billion and $410 billion in annual value for the pharmaceutical sector by transforming this paradigm [6]. Machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and reinforcement learning (RL) now underpin a new generation of computational tools that accelerate target identification, compound screening, lead optimization, and reaction planning. By leveraging large-scale biological and chemical datasets, these technologies enhance precision, reduce development timelines by up to 40%, and lower associated costs by 30%, marking a fundamental shift in therapeutic development [7] [6].

Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling in Drug Discovery

Machine learning encompasses algorithmic frameworks that learn from high-dimensional datasets to identify latent patterns and construct predictive models through iterative optimization. In drug discovery, ML is primarily applied through several paradigms: supervised learning for classification and regression tasks (e.g., using SVMs and Random Forests), unsupervised learning for clustering and dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA, K-means), and semi-supervised learning which leverages both labeled and unlabeled data to boost prediction reliability [8]. These methods have become indispensable for early-stage research, enabling data-driven decisions across the discovery pipeline.

A primary application is predicting drug-target interactions (DTI) and drug-target binding affinity (DTA), which quantifies the strength of interaction between a compound and its protein target. Accurate DTA prediction enriches binary interaction data, providing crucial information for lead optimization [9]. ML models analyze molecular structures and protein sequences to predict these affinities, outperforming traditional methods. For instance, on benchmark datasets like KIBA, Davis, and BindingDB, modern ML models achieve high performance, as summarized in Table 1 [9].

Table 1: Performance of ML Models for Drug-Target Affinity Prediction on Benchmark Datasets

| Model | Dataset | MSE (↓) | CI (↑) | r²m (↑) | AUPR (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepDTAGen [9] | KIBA | 0.146 | 0.897 | 0.765 | - |

| DeepDTAGen [9] | Davis | 0.214 | 0.890 | 0.705 | - |

| DeepDTAGen [9] | BindingDB | 0.458 | 0.876 | 0.760 | - |

| GraphDTA [9] | KIBA | 0.147 | 0.891 | 0.687 | - |

| GDilatedDTA [9] | KIBA | - | 0.920 | - | - |

| SSM-DTA [9] | Davis | 0.219 | - | 0.689 | - |

Abbreviations: MSE: Mean Squared Error; CI: Concordance Index; r²m: R squared metric; AUPR: Area Under Precision-Recall Curve. Lower MSE is better; higher values for other metrics indicate better performance.

Application Note: Protocol for Predicting Drug-Target Binding Affinity

Objective: To computationally predict the binding affinity of a small molecule drug candidate against a specific protein target using a supervised deep learning model.

Experimental Protocol (in silico):

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Source benchmark datasets such as KIBA, Davis, or BindingDB, which provide known drug-target pairs with experimental binding affinity values [9].

- Represent drugs as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings or molecular graphs. For graph representations, extract atom features (e.g., atom type, degree) and bond features [9].

- Represent protein targets as amino acid sequences.

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 80%/10%/10%) using random or cold-fold splits to assess model generalizability.

Model Training and Optimization:

- Employ a deep learning architecture such as DeepDTAGen, which uses:

- A graph neural network (GNN) or 1D convolutional neural network (CNN) to learn structural features from the drug molecule [9].

- A CNN or recurrent neural network (RNN) to learn sequential features from the protein target [9].

- A multitask framework with a shared feature space for simultaneous affinity prediction and target-aware drug generation [9].

- Address gradient conflicts in multitask learning using algorithms like FetterGrad, which minimizes the Euclidean distance between task gradients to ensure aligned learning [9].

- Train the model to minimize the loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error for affinity prediction) using an optimizer like Adam.

- Employ a deep learning architecture such as DeepDTAGen, which uses:

Model Validation and Affinity Prediction:

- Validate model performance on the held-out test set using metrics in Table 1.

- Perform robustness tests including drug selectivity analysis, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) analysis, and cold-start tests for new drugs or targets [9].

- Input the novel drug-target pair's representations into the trained model to predict the binding affinity value.

Diagram 1: Workflow for ML-based Drug-Target Affinity Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Modeling

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Datasets for Predictive Modeling

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIBA Dataset | Dataset | Provides benchmark data for drug-target binding affinity prediction, combining KIBA and binding affinity scores. | Used for training and evaluating models like DeepDTAGen [9]. |

| SMILES | Molecular Representation | A string-based notation for representing molecular structures in a format readable by ML models. | Standard input for models like DeepDTA [9]. |

| Molecular Graph | Molecular Representation | Represents a drug as a graph with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, preserving structural information. | Input for GraphDTA and related GNN-based models [9]. |

| FetterGrad Algorithm | Software Algorithm | Mitigates gradient conflicts in multitask learning models, ensuring stable and aligned training for joint tasks. | Key component of the DeepDTAGen framework [9]. |

| Cold-Start Test | Validation Protocol | Evaluates a model's performance on predicting interactions for entirely new drugs or targets not seen during training. | Critical for assessing real-world applicability [9]. |

Deep Learning for Molecular Design and Optimization

Deep learning, a subset of ML utilizing multi-layered neural networks, excels at automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from raw data. DL architectures such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and graph neural networks (GNNs) are particularly powerful for processing complex chemical and biological data, including molecular structures, protein sequences, and images [7] [8]. These capabilities have made DL transformative for molecular design and optimization.

A landmark application is de novo molecular generation, where models like generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) design novel chemical entities with desired properties. The DeepDTAGen framework exemplifies this by integrating drug-target affinity prediction with target-aware drug generation in a unified multitask model [9]. This ensures generated molecules are not only chemically valid but also optimized for specific biological targets. For generated molecules, key evaluation metrics include Validity (proportion of chemically valid molecules), Novelty (proportion not in training data), and Uniqueness (proportion of unique molecules among valid ones) [9].

Furthermore, DL has revolutionized protein structure prediction. AlphaFold, an AI system from DeepMind, predicts protein 3D structures from amino acid sequences with near-experimental accuracy [5]. This provides critical insights for drug design by elucidating how potential drugs interact with their targets.

Application Note: Protocol for Target-Aware de Novo Molecular Generation

Objective: To generate novel, target-specific drug molecules with optimal binding affinity using a deep generative model.

Experimental Protocol (in silico):

Problem Formulation and Condition Setup:

- Define the condition, which is the protein target's structural or sequential information.

- Specify desired properties for the generated molecules, such as high binding affinity to the target, suitable drug-likeness (e.g., QED), and synthesizability.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Utilize a conditioned generative model such as DeepDTAGen, which employs a shared latent space for both affinity prediction and molecule generation [9].

- The encoder transforms the input drug (e.g., SMILES) and target information into a shared latent representation.

- The decoder is typically a transformer-based model that generates new, valid SMILES strings conditioned on the target information and the latent features [9].

- Train the model using a combined loss function that includes:

- A reconstruction loss for accurate SMILES generation.

- A prediction loss for accurate binding affinity.

- A regularization loss (e.g., from a variational autoencoder) to ensure a smooth latent space.

Molecule Generation and Validation:

- Generate novel molecules by sampling from the latent space and decoding, conditioned on the specific target.

- Validate the output by assessing the Validity, Novelty, and Uniqueness of the generated SMILES [9].

- Perform chemical analysis on the generated drugs to evaluate key properties like solubility, drug-likeness, and synthesizability [9].

- Conduct polypharmacological analysis to investigate the interaction profiles of the generated drugs with non-target proteins.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Deep Learning-based Molecular Generation

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Design

Table 3: Key Tools and Metrics for Deep Learning in Molecular Design

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepDTAGen Framework | Software Model | A multitask deep learning framework that predicts drug-target affinity and simultaneously generates novel, target-aware drug variants. | Represents unified approach to predictive and generative tasks [9]. |

| Transformer Decoder | Model Architecture | A neural network architecture used for generating SMILES strings sequentially, conditioned on a latent representation. | Used in DeepDTAGen for molecule generation [9]. |

| Validity/Novelty/Uniqueness | Evaluation Metric | A set of standard metrics to quantify the quality, originality, and diversity of molecules generated by an AI model. | Essential for benchmarking generative models [9]. |

| AlphaFold | Software Model | A deep learning system that predicts a protein's 3D structure from its amino acid sequence with high accuracy. | Critical for structure-based drug design [5]. |

| Chemical Property Analysis | Validation Protocol | Computational assessment of generated molecules for solubility, drug-likeness (QED), and synthesizability (SA). | Ensures generated molecules have practical potential [9]. |

Reinforcement Learning for Reaction Route Optimization

Reinforcement learning involves an intelligent agent that learns to make optimal sequential decisions by interacting with an environment to maximize cumulative rewards. Framed as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), RL defines states (sₜ), actions (aₜ), a transition function (P(sₜ₊₁|aₜ, sₜ)), and a reward function (r) [10] [11]. In chemical synthesis, the agent learns to select a sequence of chemical reactions or adjustments to reaction parameters to achieve a desired outcome, such as maximizing yield or identifying the lowest-energy reaction pathway.

RL is uniquely suited for complex problems like computer-assisted synthesis planning (CASP) and catalytic reaction mechanism investigation. For instance, RL can be applied to hybrid organic chemistry–synthetic biological reaction network data to assemble synthetic pathways from building blocks to a target molecule [12]. The agent "learns the values" of molecular structures to suggest near-optimal multi-step synthesis routes from a large pool of available reactions [12].

A significant advancement is the High-Throughput Deep Reinforcement Learning with First Principles (HDRL-FP) framework, which autonomously explores catalytic reaction paths. HDRL-FP uses a reaction-agnostic representation based solely on atomic positions, mapped to a potential energy landscape derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations [11]. This allows the RL agent to explore elementary reaction mechanisms without predefined rules, successfully identifying pathways for critical processes like ammonia synthesis on Fe(111) with lower energy barriers than previously known [11].

Application Note: Protocol for Optimizing Chemical Reactions using RL

Objective: To employ a reinforcement learning agent to autonomously discover an optimal, low-energy pathway for a catalytic reaction.

Experimental Protocol (in silico):

Environment and MDP Definition:

- State (sₜ): Define the state using the Cartesian coordinates of the migrating atom(s). Normalize coordinates and include the Euclidean distance to the target product position [11]. Example: sₜ = (xₜ/Lₓ, yₜ/Lᵧ, zₜ/L₂, distance{(xₜ, yₜ, zₜ), (xf, yf, z_f)}/D).

- Action (aₜ): Define the action space as the stepwise movement of a migrating atom in six possible directions within a 3D grid: forward, backward, up, down, left, right. For multiple atoms, use a 2D action space: (atom choice, move direction) [11].

- Reward (r): Design the reward function based on first principles. A common approach is r = -ΔE / E₀, where ΔE is the electronic energy difference (from DFT) between states, and E₀ is a normalization factor. Assign a penalty (e.g., r = -1) for physically impossible moves, such as atoms moving too close [11].

Agent Training with High-Throughput RL:

- Implement an HDRL-FP framework to run thousands of concurrent RL simulations on a single GPU. This high-throughput parallelization diversifies exploration and dramatically accelerates convergence [11].

- Use a policy network, π{θp}(aₜ|sₜ), represented by a deep neural network, to select actions.

- Train the agent using an off-policy RL algorithm (e.g., TD3, SAC) suited for continuous action spaces. The agent explores the potential energy landscape by taking actions, receiving rewards, and updating its policy to maximize the cumulative reward.

Pathway Identification and Validation:

- After training, the agent's policy will yield the trajectory of states (atomic coordinates) that maximizes reward, which corresponds to the minimum energy path (MEP) for the reaction.

- Validate the identified reaction path by comparing its energy profile and activation barrier with known pathways from literature or traditional methods like Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) calculations [11].

Diagram 3: Reinforcement Learning for Reaction Pathway Exploration

Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Optimization

Table 4: Key Components for RL-based Reaction Optimization

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDRL-FP Framework | Software Framework | A high-throughput, reaction-agnostic RL framework that uses atomic coordinates and first-principles calculations to explore catalytic reaction paths. | Enables fast convergence on a single GPU [11]. |

| Potential Energy Landscape (PEL) | Environment Model | The energy surface of the chemical system, derived from first-principles (e.g., DFT), which the RL agent navigates. | Provides the foundation for the reward function [11]. |

| Policy Network (π) | Model Architecture | A deep neural network that defines the agent's strategy by mapping states (atomic positions) to actions (atom movements). | The core of the RL agent, e.g., in HDRL-FP [11]. |

| Markov Decision Process (MDP) | Formal Framework | A mathematical framework for modeling sequential decision making, defining states, actions, transitions, and rewards. | Standard formalism for structuring RL problems [11]. |

| Reaxys & KEGG Databases | Data Source | Comprehensive databases of historical organic and metabolic reactions used to build hybrid reaction networks for synthesis planning. | Used as reaction pools for RL-based retrosynthesis [12]. |

Retrosynthetic Analysis, Reaction Yield Prediction, and Pathway Optimization

Application Note

Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized synthetic chemistry by introducing data-driven methodologies for retrosynthetic planning, reaction outcome prediction, and multi-objective pathway optimization. These technologies address core challenges in organic synthesis and drug discovery, enabling more efficient and informed experimental workflows. By leveraging large reaction datasets and advanced algorithms, ML models can predict complex reaction pathways, forecast yields, and prioritize synthetically accessible and biologically relevant molecules, thereby accelerating the hit-to-lead optimization process [13] [7].

This application note details key protocols for implementing ML-guided reaction optimization, framed within a broader thesis on this transformative research area. It provides a structured overview of core concepts, quantitative performance comparisons of state-of-the-art models, and detailed experimental methodologies.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Performance

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of various ML models and descriptors for critical tasks in reaction optimization.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML Models in Synthesis Planning and Yield Prediction

| Model / Descriptor | Task | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Key Innovation / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetroTRAE [14] | Single-step Retrosynthesis | Top-1 Exact Match Accuracy | 58.3% (61.6% with analogs) | Uses Atom Environments (AEs) instead of SMILES, avoiding grammar issues. |

| Retro-Expert [15] | Interpretable Retrosynthesis | Outperforms specialized & LLM models | N/A | Collaborative reasoning between LLMs and specialized models; provides natural language explanations. |

| RS-Coreset [16] | Yield Prediction with Small Data | Prediction Error (Absolute) | >60% of predictions have <10% error | Achieves high-fidelity yield prediction using only 2.5-5% of the full reaction space data. |

| Geometric Deep Learning [13] | Minisci-type C-H Alkylation | Potency Improvement | Up to 4500-fold over original hit | Identified subnanomolar MAGL inhibitors from a virtual library of 26,375 molecules. |

| Guided Reaction Networks [17] | Analog Synthesis & Validation | Experimental Success Rate | 12 out of 13 designed routes successful | Generated & validated potent analogs of Ketoprofen and Donepezil via a retro-forward pipeline. |

Protocols

Protocol 1: ML-Guided Retrosynthetic Planning using Atom Environments

Principle: This protocol uses the RetroTRAE framework to perform single-step retrosynthesis prediction [14]. It bypasses the inherent fragility of SMILES strings by representing molecules as sets of Atom Environments (AEs)—topological fragments centered on an atom with a preset radius. A Transformer-based neural machine translation model then learns to translate the AEs of a target product into the AEs of the likely reactants.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Input Representation:

a. Obtain the molecular structure of the target product.

b. Decompose the molecule into its constituent Atom Environments. An AE with radius

r=0(AE0) contains only the central atom type. An AE withr=1(AE2) contains the central atom, its nearest neighbors, and the bonds connecting them [14]. c. Convert each unique AE, represented as a SMARTS pattern, into a unique integer token. d. The input to the model is the sequential list of these integer tokens representing the product's AEs.

Model Inference: a. Utilize a pre-trained RetroTRAE model, which is based on the Transformer architecture [14]. b. The model's encoder processes the input sequence of product AEs. c. The model's decoder auto-regressively generates a sequence of tokens representing the AEs of the predicted reactants.

Output Reconstruction: a. Convert the output sequence of integer tokens back into their corresponding AE SMARTS patterns. b. Reconstruct the complete molecular structures of the predicted reactants from the set of output AEs.

Protocol 2: Predictive Yield Modeling with Limited Data

Principle: This protocol employs the RS-Coreset method to predict reaction yields across a vast reaction space while requiring experimental data for only a small fraction (2.5-5%) of all possible condition combinations [16]. It combines active learning with representation learning to iteratively select the most informative reactions for experimentation, building a predictive model that generalizes to the entire space.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Reaction Space Definition: a. Define the scope of all reaction components: substrates, catalysts, ligands, solvents, additives, etc. b. The full reaction space is the Cartesian product of all component options, which can contain thousands to hundreds of thousands of combinations [16].

Iterative RS-Coreset Construction: a. Initialization: Select a small batch of reaction combinations uniformly at random or based on prior literature knowledge. b. Yield Evaluation: Perform experiments for the selected combinations and record the yields. This is ideally done using High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) equipment [16]. c. Representation Learning: Update a machine learning model (e.g., a deep representation learning model) using all accumulated yield data. The model learns to map reaction conditions to a representation space that correlates with yield. d. Data Selection: Using a maximum coverage algorithm, select the next batch of reaction combinations from the unexplored space that are most informative for the model. This step aims to maximize the diversity and representation quality of the growing "coreset." e. Iteration: Repeat steps b-d until the model's predictions stabilize, typically after several rounds.

Prediction and Validation: a. Use the final model to predict yields for all reactions in the full, originally defined space. b. Prioritize high-predicted-yield conditions for experimental validation.

Protocol 3: Integrated Analog Design via Retro-Forward Synthesis

Principle: This protocol describes a pipeline for generating and synthesizing structural analogs of a known drug (parent molecule) [17]. It integrates parent diversification, retrosynthesis, and guided forward synthesis to rapidly identify potent and synthetically accessible analogs.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Parent Diversification: a. Identify key substructures within the parent molecule that are suitable for modification. b. Generate a library of "replica" molecules by systematically replacing these substructures with functionally similar or bioisosteric fragments [17].

Retrosynthetic Substrate Selection: a. For each replica, perform computer-assisted retrosynthetic analysis using a knowledge base of reaction transforms. The search is typically limited to a practical depth (e.g., 5 steps) and uses common medicinal chemistry reactions [17]. b. Trace all routes back to commercially available starting materials. c. Collect the union of all identified substrates to form a diverse and synthetically relevant set of building blocks (G0).

Guided Forward-Synthesis: a. Use the substrate set (G0) to build a forward-synthesis reaction network. b. Apply a large set of reaction transforms (~25,000 rules) to G0 to create the first generation of products (G1). c. Beam Search: From the thousands of molecules in G1, retain only a pre-determined number (

W, e.g., 150) that are structurally most similar to the parent molecule [17]. d. Iterate the process: allow retained molecules to react with substrates from previous generations, and after each generation, prune the network to keep only theWmost parent-similar molecules. This "guides" the network expansion toward the parent's structural analogs. e. The output is a network containing thousands of readily makeable analogs, generated in a matter of minutes.Candidate Selection and Experimental Validation: a. Select top candidates from the network based on synthetic accessibility, predicted binding affinity (e.g., via molecular docking), and other drug-like properties. b. Execute the computer-designed synthetic routes and validate the potency of the analogs through binding assays [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Workflow | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Commercially Available Building Blocks | Serve as the foundational substrates (G0) for forward-synthesis networks and retrosynthetic analysis. | Used in the retro-forward pipeline to ensure proposed analogs originate from purchasable materials [17]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Kits | Enable rapid, parallel synthesis of hundreds to thousands of reaction conditions for data generation. | Crucial for efficiently collecting the yield data needed to train predictive models like RS-Coreset [13] [16]. |

| Pre-defined Reaction Transforms / Templates | Encoded chemical rules that allow computers to simulate realistic chemical reactions in silico. | A knowledge base of ~25,000 rules was used to build guided reaction networks for analog design [17]. |

| Atom Environment (AE) Libraries | Chemically meaningful molecular descriptors that serve as non-fragile inputs for retrosynthesis models. | Used by RetroTRAE to represent molecules, overcoming the grammatical invalidity issues of SMILES strings [14]. |

| Specialized Model Suites | Software tools for specific subtasks (e.g., reaction center identification, reactant generation). | Integrated within the Retro-Expert framework to provide "shallow reasoning" and construct a chemical decision space for LLMs [15]. |

The integration of cheminformatics and quantum chemistry simulations is creating a powerful, data-driven paradigm for scientific discovery, particularly within the context of machine learning (ML) guided reaction optimization. This synergy leverages the data management and predictive power of cheminformatics with the high-fidelity simulation capabilities of quantum mechanics to navigate complex chemical spaces with unprecedented efficiency [18]. The core of this evolving workflow lies in using large-scale quantum chemical data to train ML models, which can then accelerate and guide research decisions, from molecular design to reaction feasibility studies [19] [20]. This application note details the protocols and key solutions enabling this transformative integration.

Application Note: ML-Guided Reaction Pathway Exploration

A primary application of this integrated workflow is the automated exploration of reaction pathways, a task fundamental to understanding reaction mechanisms and optimizing chemical synthesis.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following tools and datasets are essential for implementing the protocols described in this note.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Workflows

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARplorer [21] | Software Program | Automated reaction pathway exploration | Integrates QM calculations with rule-based and LLM-guided chemical logic to efficiently map Potential Energy Surfaces (PES). |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [19] [20] | Dataset | Pre-trained foundation model training | Provides over 100 million DFT-calculated molecular snapshots for training accurate, transferable ML interatomic potentials. |

| Architector [19] | Software | 3D structure prediction | Predicts 3D structures of challenging metal complexes, enriching datasets for inorganic and organometallic chemistry. |

| GFN2-xTB [21] | Quantum Chemical Method | Semi-empirical quantum mechanics | Enables rapid, large-scale PES screening and initial structure optimization at a fraction of the computational cost of DFT. |

| LLM-Guided Chemical Logic [21] | Methodology | Reaction rule generation | Mines chemical literature to generate system-specific SMARTS patterns and filters, guiding the exploration of plausible reaction pathways. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the recursive, multi-step workflow for automated reaction pathway exploration, as implemented in tools like ARplorer.

Protocol: Automated Multi-Step Reaction Exploration with ARplorer

This protocol outlines the process for using a program like ARplorer to automate the exploration of multi-step reaction pathways, combining quantum mechanics with LLM-guided chemical logic [21].

Objective: To automatically identify feasible reaction pathways, including intermediates and transition states, for a given set of reactants.

Materials:

- ARplorer software (or equivalent integrated computational environment) [21].

- Quantum chemistry software packages (e.g., Gaussian 09) and semi-empirical methods (e.g., GFN2-xTB) [21].

- Pre-processed general chemical knowledge base for LLM guidance.

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster.

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Convert the molecular structures of the reactants into SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) format.

- Input the SMILES strings into the ARplorer program.

Active Site Identification & Rule Application:

- The program uses a Python module like Pybel to compile a list of active atom pairs and potential bond-breaking/forming locations.

- The integrated LLM, prompted with the reaction system's SMILES, generates system-specific chemical logic and SMARTS patterns. This logic acts as a filter to bias the search towards chemically plausible pathways and avoid unlikely ones [21].

Structure Optimization and Transition State Search:

- The system performs an initial, rapid geometry optimization of all generated molecular structures using the GFN2-xTB method to ensure reasonable starting conformations [21].

- An active-learning sampling method is employed for transition state (TS) searches on the potential energy surface generated by GFN2-xTB. This iterative process hones in on potential TS geometries.

Pathway Validation via Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC):

- For each located TS, perform an IRC analysis in both forward and reverse directions to confirm it connects the correct reactants and products.

- The resulting pathways from the IRC are analyzed, and new intermediates are identified and stored.

Data Curation and Iteration:

- The program eliminates duplicate structures and reaction pathways.

- Newly identified intermediates are fed back into the workflow as starting points for the next cycle of exploration, enabling the discovery of multi-step reaction networks.

High-Fidelity Calculation (Optional):

- For the most promising pathways, single-point energy calculations or re-optimization can be performed using higher-level Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods to achieve greater accuracy.

Notes: The flexibility of the workflow allows for switching between computational methods based on the task—GFN2-xTB for rapid screening and DFT for precise results. The entire process is designed for parallel computing, significantly accelerating the exploration.

Application Note: Leveraging Large-Scale Datasets for ML Potentials

The development of accurate Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) relies on access to vast, high-quality quantum chemistry data.

Protocol: Building and Using a Foundation Model with OMol25

This protocol describes how to leverage the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset to train or fine-tune MLIPs for molecular simulations [19] [20].

Objective: To create an MLIP that provides quantum chemistry-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling the simulation of large and complex molecular systems.

Materials:

- The Open Molecules 2025 dataset (publicly available).

- Machine learning software for training interatomic potentials (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow-based frameworks).

- Access to computing resources with GPUs for model training.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Familiarization:

- Download the OMol25 dataset, which contains over 100 million molecular configurations with properties calculated using DFT [20].

- Explore the dataset's composition, which includes diverse molecular classes: small organic molecules, biomolecules (proteins, RNA), electrolytes, and metal complexes [19] [20].

Model Selection and Setup:

- Choose a suitable neural network architecture for an MLIP (e.g., a graph neural network).

- As an alternative, download the pre-trained "universal model" provided by the Meta FAIR team, which is already trained on OMol25 and other open-source datasets [20].

Training/Finetuning:

- If training from scratch, partition the OMol25 data into training, validation, and test sets.

- Train the model to predict the system's energy and atomic forces from the 3D atomic structure.

- For domain-specific applications, fine-tune the pre-trained universal model on a smaller, targeted dataset of relevant molecules to enhance its performance for your specific research question.

Validation and Evaluation:

- Use the provided evaluation benchmarks from the OMol25 project to rigorously test the model's performance on chemically relevant tasks [20].

- Validate the model's predictions against held-out DFT calculations or select experimental data to ensure physical soundness and accuracy.

Deployment in Simulation:

- Integrate the validated MLIP into molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulation packages.

- Run simulations that were previously computationally prohibitive with DFT, such as nanosecond-scale dynamics of systems with thousands of atoms [20].

Data Presentation

The quantitative impact of using large-scale datasets for training is demonstrated by the scale and diversity of the OMol25 resource compared to its predecessors.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Molecular Datasets for ML Potential Training

| Dataset | Size (No. of Calculations) | Computational Cost | Avg. Atoms per Molecule | Key Chemical Domains Covered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [19] [20] | >100 million | 6 billion CPU hours | ~200-350 | Biomolecules, Electrolytes, Metal Complexes, Small Molecules |

| Previous Datasets (e.g., pre-2025) [20] | Smaller (implied) | "10 times less" than OMol25 | 20-30 | Limited, "handful of well-behaved elements" |

The workflows and protocols detailed herein demonstrate a tangible shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery. The integration of cheminformatics for data management and hypothesis generation, with quantum chemistry for foundational accuracy, creates a powerful cycle. Machine learning models, trained on massive quantum datasets like OMol25 and guided by chemical logic, are no longer just predictive tools but are becoming active partners in the exploration of chemical space. This evolving workflow promises to significantly accelerate the design of novel reactions and the optimization of molecular properties for diverse applications, from synthetic chemistry to rational drug design.

ML Algorithms and Automation: Practical Implementation in Reaction Optimization

The optimization of chemical reactions is a cornerstone of synthetic chemistry, crucial for applications ranging from industrial process scaling to the development of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Traditional optimization methods, which often rely on chemical intuition and one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, are increasingly proving inadequate for navigating complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces efficiently. The integration of machine learning (ML) algorithms represents a paradigm shift, enabling data-driven and adaptive experimental strategies. This application note details the operational frameworks, experimental protocols, and practical implementations of three cornerstone ML-guided methodologies—Bayesian Optimization, Active Learning, and Evolutionary Methods—within the context of modern reaction optimization research for drug development professionals.

Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Optimization

Core Principles and Workflow

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy for the global optimization of expensive-to-evaluate "black-box" functions. It is particularly suited for chemical reaction optimization where each experimental measurement is resource-intensive. The algorithm operates by constructing a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective function (e.g., reaction yield or selectivity) and uses an acquisition function to intelligently select the next most promising experiments based on the model's predictions and associated uncertainties [22] [23].

The robust performance of BO has been demonstrated experimentally. In one study, a BO framework was deployed in a 96-well high-throughput experimentation (HTE) campaign for a challenging nickel-catalysed Suzuki reaction. The BO approach successfully identified conditions yielding 76% area percent (AP) yield and 92% selectivity, outperforming chemist-designed HTE plates which failed to find successful conditions [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Implementing Bayesian Optimization for a Chemical Reaction Campaign

- Objective: Maximize reaction yield and selectivity for a Ni-catalysed Suzuki coupling.

- Step 1 – Define the Search Space: Compile a discrete set of plausible reaction conditions. This typically includes:

- Ligands: A list of 10-20 potential ligands.

- Bases: A set of 5-10 inorganic or organic bases.

- Solvents: A selection of 10-15 solvents adhering to pharmaceutical guidelines [24].

- Continuous Variables: Catalyst loading (e.g., 0.5-5.0 mol%), temperature (e.g., 25-100 °C), and concentration.

- Constraints: Implement automatic filtering to exclude unsafe or impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [24].

- Step 2 – Initial Experimental Design:

- Use Sobol sampling, a quasi-random method, to select an initial batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate) [24].

- Rationale: This maximizes the initial coverage of the reaction space, increasing the probability of discovering informative regions.

- Step 3 – Execution and Analysis:

- Run the batch of reactions using automated HTE platforms.

- Analyze the outcomes (e.g., via UPLC/MS) to obtain the objectives (yield, selectivity).

- Step 4 – Machine Learning Iteration:

- Surrogate Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all accumulated experimental data. The GP models the reaction landscape and provides predictions and uncertainty estimates for all unexplored conditions [24].

- Next Experiment Selection: Use an acquisition function to select the next batch of experiments. For scalable multi-objective optimization (e.g., simultaneously maximizing yield and selectivity), functions like q-NParEgo or Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI) are recommended for large batch sizes due to their computational efficiency [24].

- Step 5 – Iteration and Termination:

- Repeat Steps 3 and 4 for a predetermined number of iterations or until convergence (e.g., no significant improvement in hypervolume over two iterations).

- The final output is a set of Pareto-optimal conditions that balance the multiple objectives.

Table 1: Key Components of a Bayesian Optimization Workflow

| Component | Description | Example/Common Choice |

|---|---|---|

| Search Space | The set of all possible reaction parameters to be explored. | Combinations of ligand, base, solvent, concentration, temperature [24]. |

| Surrogate Model | A probabilistic model that approximates the objective function. | Gaussian Process (GP) with a Matérn kernel [24]. |

| Acquisition Function | A function to decide which experiments to run next by balancing exploration and exploitation. | q-NParEgo, TS-HVI for multi-objective, large-batch optimization [24]. |

| Initial Sampling | Method to select the first batch of experiments before any data is available. | Sobol Sequence (quasi-random sampling) [24]. |

Workflow Visualization

Active Learning for Data-Scarce Drug Discovery

Core Principles and Workflow

Active Learning (AL) is an iterative ML paradigm designed to maximize information gain while minimizing the number of expensive experiments or computations. It is particularly valuable in data-scarce regimes, such as late-stage functionalization (LSF) of complex drug candidates, where acquiring data is costly and time-consuming [25]. The core idea is to start with a small initial dataset and have the algorithm iteratively select the most "informative" or "uncertain" data points for experimental validation, thereby refining the model most efficiently.

Advanced implementations, such as those used in generative AI for drug design, can involve nested AL cycles. One reported workflow uses a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) as a molecular generator, coupled with an inner AL cycle that filters generated molecules for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility, and an outer AL cycle that uses physics-based oracles (e.g., molecular docking) to prioritize molecules for further training [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: An Active Learning Workflow for Late-Stage Functionalization

- Objective: Predict regioselectivity and optimize yield for C-H borylation on novel, complex substrates.

- Step 1 – Initial Model Training:

- Begin with a small, diverse benchmark dataset of historical C-H borylation reactions [25].

- Train an initial tree-based ensemble model (e.g., Random Forest or XGBoost) or a geometric graph neural network to predict reaction outcome. Tree-based models are often preferred initially due to their computational efficiency and strong performance on small datasets [25].

- Step 2 – Query Strategy and Selection:

- Use the trained model to predict outcomes on a large, virtual library of potential substrate and condition combinations.

- Apply an uncertainty sampling query strategy. Select the substrates/conditions for which the model's prediction is most uncertain (e.g., highest predictive variance or entropy).

- Alternatively, use a diversity sampling strategy to ensure broad coverage of the chemical space.

- Step 3 – Experimental Validation and Model Update:

- Synthesize the selected substrates and run the proposed borylation reactions in the laboratory.

- Acquire the ground-truth data on reaction success, yield, and regioselectivity.

- Add this new experimental data to the training set and retrain the predictive model.

- Step 4 – Iteration:

- Repeat Steps 2 and 3 until a predefined performance threshold is met (e.g., >90% regioselectivity prediction accuracy on a test set) or the experimental budget is exhausted.

- The final model can then be used to prospectively guide the functionalization of new, unseen drug-like molecules.

Table 2: Active Learning Components for Reaction Prediction

| Component | Role in Reaction Optimization | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Dataset | A small, starting point of known reactions. | 50-100 C-H borylation reactions with varied substrates [25]. |

| Machine Learning Model | The predictive function to be improved. | Tree-based Ensemble (speed) or Geometric Graph Neural Network (accuracy) [25]. |

| Query Strategy | The algorithm for selecting new experiments. | Uncertainty Sampling (selects most uncertain predictions) [25]. |

| Oracle | The source of ground-truth labels for selected experiments. | High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in the lab [25]. |

Workflow Visualization

Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization

Core Principles and Workflow

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are population-based metaheuristics inspired by biological evolution. They are highly effective for complex, multi-objective optimization problems (MOPs) where the goal is to find a set of solutions representing the best possible trade-offs between competing objectives—a concept known as the Pareto front. In chemical terms, this could mean finding conditions that balance high yield, low cost, and high selectivity. Chemical Reaction Optimization (CRO) is a specific EA that simulates the interactions of molecules in a chemical reaction to drive the population toward optimal solutions [27] [28].

Modified CRO algorithms have demonstrated superiority over standard CRO and other EAs in solving unconstrained benchmark functions and have been successfully applied to real-world engineering problems like antenna array synthesis [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Modified Chemical Reaction Optimization for Process Design

- Objective: Identify the Pareto-optimal set of process conditions for a catalytic reaction, balancing yield, environmental factor (E-factor), and cost.

- Step 1 – Population Initialization:

- Generate an initial population of "molecules" (each representing a set of reaction conditions, e.g.,

{ligand_A, solvent_B, 1.5 mol%, 80 °C}) using a space-filling design to ensure diversity [27].

- Generate an initial population of "molecules" (each representing a set of reaction conditions, e.g.,

- Step 2 – Fitness Evaluation:

- For each molecule in the population, evaluate its "fitness" by running the reaction (in silico or experimentally) and calculating the multiple objective values (e.g., Yield, -E-factor, -Cost). The negative sign is used to frame all objectives as maximization.

- Step 3 – Evolutionary Operations (Modified CRO):

- On-wall Ineffective Collision: Perturb a molecule slightly (e.g., small change in temperature or concentration) to create a new "neighbor" solution, promoting local search (exploitation).

- Decomposition: Split one molecule into two new, significantly different molecules, encouraging exploration of distant regions of the search space.

- Inter-molecular Ineffective Collision: Two molecules collide and exchange information (e.g., a crossover operation from Genetic Algorithms), creating two new offspring.

- Synthesis: Two molecules combine to form one new molecule.

- Improved Search Mechanism: The modified CRO incorporates a differential evolution-like strategy, using the best individuals to guide the search direction and a controlled modification rate to balance exploration and exploitation [27].

- Step 4 – Selection for the Next Generation:

- Use a non-dominated sorting and crowding distance technique (e.g., as in NSGA-II) to select the fittest individuals from the combined pool of parents and offspring. This ensures the population moves toward the Pareto front while maintaining diversity of solutions.

- Step 5 – Iteration:

- Repeat Steps 2-4 for multiple generations until the Pareto front converges.

Table 3: Evolutionary Operations in Chemical Reaction Optimization

| Evolutionary Operation | Analogy | Optimization Function |

|---|---|---|

| On-wall Ineffective Collision | A molecule hits a wall and undergoes a small structural change. | Local Search / Exploitation |

| Decomposition | A molecule decomposes into two smaller molecules. | Global Search / Exploration |

| Inter-molecular Collision | Two molecules collide and cause changes in each other. | Information Exchange / Crossover |

| Synthesis | Two molecules combine to form one new molecule. | Intensification / Convergence |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of these algorithms requires a synergy of computational and experimental tools. Below is a non-exhaustive list of key resources.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

| Category | Item | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software & Libraries | GPyTorch / BoTorch | Libraries for implementing Gaussian Processes and Bayesian Optimization in Python [24]. |

| EDBO / Minerva | Open-source software packages specifically designed for Bayesian reaction optimization, providing user-friendly interfaces [24] [22]. | |

| Olympus | An open-source platform for benchmarking and implementing optimization algorithms in chemistry [24]. | |

| Chemical Descriptors & Representations | SURF (Simple User-Friendly Reaction Format) | A standardized format for representing chemical reaction data, facilitating data sharing and model training [24]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A geometric deep learning architecture that operates directly on molecular graphs, highly effective for predicting regioselectivity [25]. | |

| Hardware & Automation | Automated HTE Platforms | Robotic systems enabling highly parallel execution of numerous reactions (e.g., in 24, 48, or 96-well plates), which is critical for feeding data-hungry ML algorithms [24]. |

| Solid-Dispensing Workstations | Automated tools for accurate and rapid dispensing of solid reagents, a key enabler for HTE [24]. | |

| Analytical Equipment | UPLC/MS Systems | High-throughput analytical instruments for rapid quantification of reaction outcomes (yield, conversion, selectivity), generating the data points for ML models. |

Bayesian Optimization, Active Learning, and Evolutionary Methods provide a powerful, complementary toolkit for addressing the complex challenges of modern reaction optimization in drug development. BO excels at sample-efficient navigation of high-dimensional spaces, AL is uniquely powerful in data-scarce scenarios, and EAs are robust solvers for complex multi-objective problems. The integration of these algorithms with automated HTE platforms creates a closed-loop, self-improving system that can significantly accelerate process development timelines—from 6 months to 4 weeks in one reported case [24]—and unlock novel chemical spaces. As these tools become more accessible and user-friendly, their adoption will be key to maintaining a competitive edge in pharmaceutical research and development.

The transition from traditional molecular representation methods to modern, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven techniques represents a paradigm shift in materials informatics and drug discovery. Molecular representation serves as the essential foundation for predicting material properties, chemical reactions, and biological activities, playing a pivotal role in machine learning-guided reaction optimization research [29] [30]. Traditional expert-designed representation methods, including molecular fingerprints and string-based formats, face significant challenges in dealing with the high dimensionality and heterogeneity of material data, often resulting in limited generalization capabilities and insufficient information representation [29]. In recent years, graph neural networks (GNNs) and transformer architectures have emerged as powerful deep learning algorithms specifically designed for graph and sequence structures, respectively, creating new opportunities for advancing molecular representation and reaction optimization [29] [30].

The evolution of molecular representation has progressed through three distinct phases over recent decades. The initial phase relied on molecular fingerprints such as Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) and Molecular ACCess System (MACCS), which employed expert-defined rules to encode structural information [29]. The subsequent phase incorporated string-based representations, particularly the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES), which provided a compact format for molecular encoding [29] [30]. The current phase is dominated by graph-based approaches, particularly GNNs and transformer architectures, which treat molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges, enabling more nuanced and information-rich representations [29]. This progression reflects an ongoing effort to develop representations that more accurately capture the complex structural and functional relationships underlying molecular behavior.

Table 1: Evolution of Molecular Representation Techniques

| Representation Type | Key Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | ECFP, MACCS, ROCS [29] | Computational efficiency, interpretability [31] | Limited generalization, manual feature engineering [29] |

| String-Based | SMILES, InChI [29] [30] | Compact format, human-readable [30] | Loss of spatial information, invariance issues [29] |

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, KA-GNN [29] [32] | Automatic feature learning, rich structural encoding [29] | Computational complexity, interpretability challenges [29] |

| Transformer Architectures | Graphormer, MoleculeFormer [33] [34] | Capture long-range interactions, flexibility [34] | Data hunger, high computational requirements [34] |

Fundamental Requirements for Effective Molecular Representation

For molecular representation techniques to be effective in reaction optimization and property prediction, they must satisfy four fundamental requirements: expressiveness, adaptability, multipurpose capability, and invariance [29]. Expressiveness demands that representations contain rich, fine-grained information about atoms, chemical bonds, multi-order adjacencies, and topological structures [29]. Adaptability requires that representations can dynamically adjust to different downstream tasks rather than remaining frozen, actively generating task-relevant features based on specific application characteristics [29]. Multipurpose capability reflects the breadth of application, enabling competence across various tasks including node classification, graph classification, connection prediction, and node clustering [29]. Finally, invariance ensures that the same molecular structure always generates identical representations, a particular challenge for string-based methods where different SMILES sequences can represent identical molecules [29].

When evaluated against these requirements, traditional and modern representation methods demonstrate distinct strengths and limitations. Molecular fingerprint-based approaches generally satisfy expressiveness for basic structural features but lack adaptability and multipurpose capability [29]. String-based methods offer some advantages in adaptability but suffer from limited expressiveness and critical failures in invariance [29]. In contrast, GNNs meet all four requirements, providing a comprehensive framework for effective molecular representation in reaction optimization research [29]. This comprehensive capability explains the rapid adoption of GNNs and related architectures in modern cheminformatics and drug discovery pipelines.

Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Representation

Core Architectures and Methodologies

Graph Neural Networks represent a specialized class of deep learning algorithms explicitly designed for graph-structured data, making them particularly suitable for molecular representation where atoms naturally correspond to nodes and chemical bonds to edges [29]. The fundamental operation of GNNs involves message passing, where node representations are iteratively updated by aggregating information from neighboring nodes [29]. This process enables GNNs to automatically capture local chemical environments and topological relationships without manual feature engineering, addressing key limitations of traditional fingerprint-based approaches [29].

Several GNN architectures have been developed specifically for molecular applications. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) operate by performing symmetric normalization of neighbor embeddings, effectively capturing local graph substructures [32]. Graph Attention Networks (GATs) incorporate attention mechanisms that assign learned importance weights to neighboring nodes during message passing, enabling the model to focus on more relevant chemical contexts [32]. More recently, Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) have integrated Kolmogorov-Arnold network modules into the three fundamental components of GNNs: node embedding, message passing, and readout [32]. These KA-GNNs utilize Fourier-series-based univariate functions to enhance function approximation, providing theoretical guarantees for strong approximation capabilities while improving both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency [32].

Table 2: Key GNN Architectures for Molecular Representation

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Key Advantages | Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [32] | Neighborhood aggregation with symmetric normalization | Conceptual simplicity, computational efficiency | Molecular property prediction, activity classification [32] |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) [32] | Attention-weighted neighborhood aggregation | Differentiated importance of atomic interactions | Protein-ligand binding affinity prediction [32] |

| Kolmogorov-Arnold GNN (KA-GNN) [32] | Fourier-based KAN modules in embedding, message passing, and readout | Enhanced expressivity, parameter efficiency, interpretability | Molecular property prediction with highlighted substructures [32] |

| MoleculeFormer [33] | GCN-Transformer multi-scale feature integration | Incorporates 3D structural information with rotational invariance | Efficacy/toxicity prediction, ADME evaluation [33] |

Experimental Protocol: KA-GNN Implementation for Property Prediction

Purpose: To implement and evaluate KA-GNNs for molecular property prediction using benchmark datasets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular Datasets: Seven benchmark molecular datasets encompassing physical, chemical, and biological properties [32]

- Software Framework: Python with PyTorch and PyTorch Geometric libraries [32] [13]

- Molecular Features: Atomic features (atomic number, radius), bond features (bond type, length), and molecular graph topology [32]

- Hardware: GPU-enabled computing environment for efficient deep learning

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges

- Initialize node features using atomic properties and local chemical context

- Initialize edge features with bond characteristics and spatial relationships

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 80/10/10)

Model Initialization:

- Implement KA-GCN or KA-GAT architecture with Fourier-based KAN layers

- Configure node embedding module: concatenate atomic features with averaged neighboring bond features, process through KAN layer

- Set up message-passing layers with residual KAN connections instead of traditional MLPs

- Initialize graph-level readout with KAN-based global aggregation

Training Configuration:

- Employ mean squared error loss for regression tasks or cross-entropy for classification

- Utilize Adam optimizer with initial learning rate of 0.001

- Implement learning rate scheduling with reduction on validation loss plateau

- Apply early stopping based on validation performance with patience of 50 epochs

Model Evaluation:

- Assess predictive performance on test set using task-relevant metrics (RMSE, MAE, ROC-AUC)

- Compare against baseline GNN models (GCN, GAT) under identical conditions

- Analyze computational efficiency through training time and inference speed measurements

- Conduct interpretability analysis by visualizing attention weights or important substructures

Troubleshooting Notes:

- For small datasets, employ regularization techniques including dropout and weight decay

- If training instability occurs, reduce learning rate or implement gradient clipping

- For molecules with complex stereochemistry, incorporate 3D structural information

- Address class imbalance in classification tasks through weighted loss functions or sampling strategies

Transformer Architectures in Molecular Representation

Graph Transformer Models and Methodologies

Transformer architectures, originally developed for natural language processing, have been successfully adapted for molecular representation by treating molecular structures as graphs and leveraging self-attention mechanisms to capture global relationships [34]. Graph-based Transformer models (GTs) have emerged as flexible alternatives to GNNs, offering advantages in implementation simplicity and customizable input handling [34]. These models can effectively process various data formats in a multimodal manner and have demonstrated strong performance across different molecular data modalities, particularly in managing both 2D and 3D molecular structures [34].

The MoleculeFormer architecture represents a significant advancement in this domain, implementing a multi-scale feature integration model based on a Graph Convolutional Network-Transformer hybrid architecture [33]. This model uses independent GCN and Transformer modules to extract features from atom and bond graphs while incorporating rotational equivariance constraints and prior molecular fingerprints [33]. By capturing both local and global features and introducing 3D structural information with invariance to rotation and translation, MoleculeFormer demonstrates robust performance across various drug discovery tasks, including efficacy/toxicity prediction, phenotype screening, and ADME evaluation [33]. The integration of attention mechanisms further enhances interpretability, and the model shows strong noise resistance, establishing it as an effective, generalizable solution for molecular prediction tasks [33].

Experimental Protocol: Graph Transformer for Molecular Property Prediction

Purpose: To implement and benchmark Graph Transformer models for molecular property prediction using 2D and 3D molecular representations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular Datasets: Three benchmark datasets (BDE, Kraken, tmQMg) focusing on reaction properties, sterimol parameters, and transition metal complexes [34]

- Software Environment: Python with PyTorch and Graphormer implementation

- Molecular Features: Heavy atom types, neighbor counts, topological distances (2D), or binned spatial distances (3D) [34]

- Computational Resources: GPU acceleration for transformer model training

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- For 2D-GT: Generate vectors of heavy atom types and neighbor counts, compute topological distances as shortest paths

- For 3D-GT: Calculate binned spatial distances with customizable parameters (recommended: 0.9Å minimum distance, 5Å neighbor sphere radius, 0.5Å precision)

- Apply dataset-specific preprocessing: conformer ensembles for Kraken, catalyst structures for BDE [34]

Model Architecture:

- Implement 2D-GT using topological distances in multi-head bias with distance-biased dot-product attention

- Implement 3D-GT using binned distances for enhanced spatial granularity

- Configure transformer layers with hidden dimension of 128 (explore 64 and 256 for ablation)

- Incorporate optional auxiliary task heads for atomic property prediction

Training Strategy:

- Employ context-enriched training through pretraining on quantum mechanical atomic-level properties

- Utilize multi-task learning where applicable to leverage correlated molecular properties

- Apply adaptive optimization with learning rate warmup and decay scheduling

- Implement gradient accumulation for large batch training on limited hardware

Evaluation and Benchmarking:

- Assess performance on primary metrics: RMSE for regression tasks, accuracy for classification

- Compare against GNN baselines (ChemProp, GIN-VN, SchNet, PaiNN) under identical conditions

- Evaluate computational efficiency through training convergence speed and inference latency

- Analyze attention maps to interpret model focus and decision rationale

Technical Notes:

- 3D-GT provides superior spatial resolution but may introduce noise for topology-focused tasks

- 2D-GT offers computational advantages for large-scale screening applications

- Context-enriched pretraining significantly enhances performance on small datasets

- Multi-task learning improves generalization across related molecular properties

Application in Reaction Optimization and Drug Discovery

Integrated Workflows for Hit-to-Lead Optimization

Molecular representation techniques using GNNs and Transformers have demonstrated significant practical impact in accelerating drug discovery pipelines, particularly in the critical hit-to-lead optimization phase [13]. Recent research has established integrated medicinal chemistry workflows that effectively diversify hit and lead structures through deep learning-guided synthesis planning [13]. In one notable implementation, researchers employed high-throughput experimentation to generate a comprehensive dataset encompassing 13,490 novel Minisci-type C-H alkylation reactions, which subsequently served as the foundation for training deep graph neural networks to accurately predict reaction outcomes [13]. This approach enabled scaffold-based enumeration of potential Minisci reaction products, starting from moderate inhibitors of monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), yielding a virtual library containing 26,375 molecules [13].

The application of molecular representation and reaction prediction in this workflow facilitated the identification of 212 MAGL inhibitor candidates from the virtual chemical library through integrated assessment using reaction prediction, physicochemical property evaluation, and structure-based scoring [13]. Of these, 14 compounds were synthesized and exhibited subnanomolar activity, representing a potency improvement of up to 4500 times over the original hit compound [13]. These optimized ligands also showed favorable pharmacological profiles, and co-crystallization of three computationally designed ligands with the MAGL protein provided structural insights into their binding modes [13]. This case study demonstrates the powerful synergy between advanced molecular representation techniques and experimental validation in accelerating drug discovery.

Scaffold Hopping and Molecular Optimization

Scaffold hopping represents another critical application of advanced molecular representation techniques in drug discovery, aimed at identifying new core structures while retaining similar biological activity as the original molecule [30]. Traditional approaches to scaffold hopping typically utilized molecular fingerprinting and structure similarity searches to identify compounds with similar properties but different core structures [30]. However, these methods are limited in their ability to explore diverse chemical spaces due to their reliance on predefined rules, fixed features, or expert knowledge [30]. Modern methods based on GNNs and transformer architectures have greatly expanded the potential for scaffold hopping through more flexible and data-driven exploration of chemical diversity [30].