Modern Catalyst Screening Methods for Organic Reactions: From AI-Driven Discovery to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary catalyst screening methodologies that are accelerating discovery in organic synthesis and drug development.

Modern Catalyst Screening Methods for Organic Reactions: From AI-Driven Discovery to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

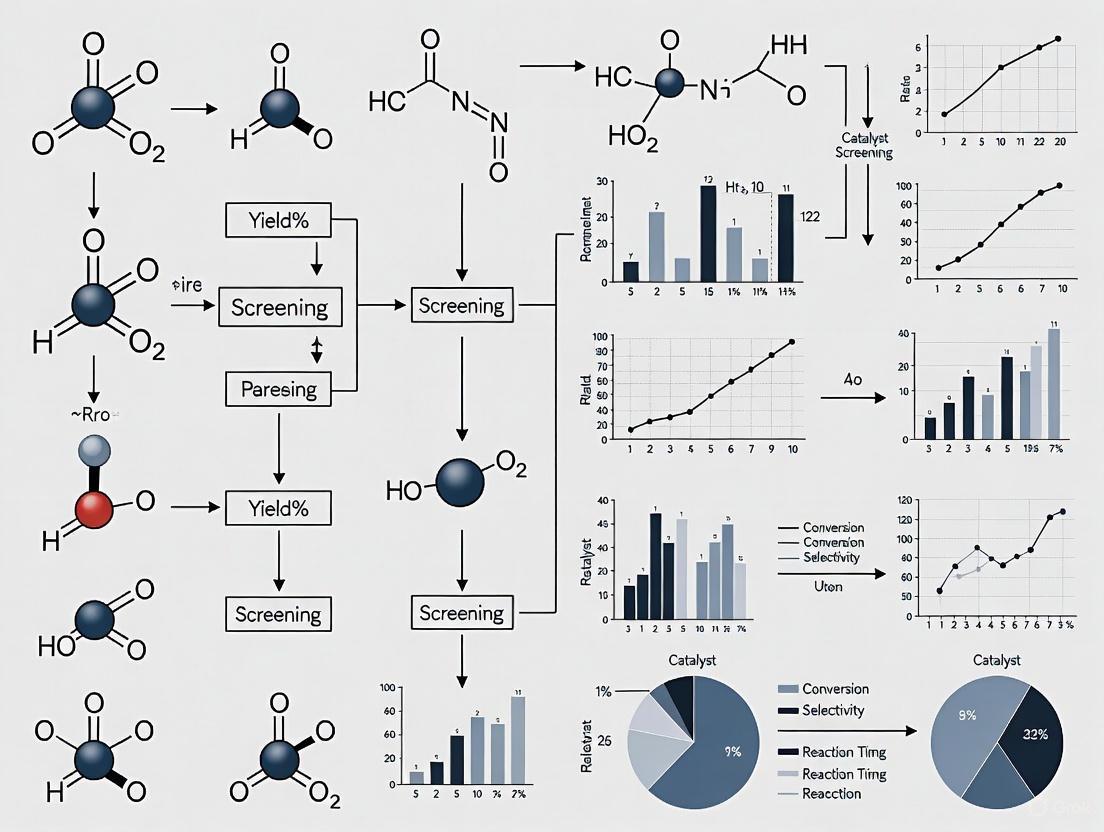

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary catalyst screening methodologies that are accelerating discovery in organic synthesis and drug development. We explore the foundational shift from traditional, labor-intensive techniques to intelligent, data-driven workflows powered by artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and high-throughput experimentation (HTE). The scope encompasses a wide array of methodological advances, including biomacromolecule-assisted sensing, ultra-high-throughput enantioselectivity analysis, and computational screening with AI-powered transition state prediction. A dedicated focus on troubleshooting common challenges—such as data quality and model interpretability—and a comparative analysis of validation techniques equip researchers with practical knowledge for optimizing their screening strategies. This resource is tailored for scientists and professionals in research and drug development seeking to leverage cutting-edge screening technologies to streamline catalyst discovery and reaction optimization.

The Evolution of Catalyst Screening: From Edisonian Trials to AI-Guided Discovery

The field of chemical synthesis has undergone a profound methodological shift, moving from traditional one-at-a-time approaches to sophisticated combinatorial and high-throughput strategies. This transition is particularly evident in catalyst screening and organic reaction research, where the demand for rapid discovery and optimization has transformed experimental paradigms. Where chemists once synthesized and tested individual compounds sequentially, they now regularly create and screen vast libraries of molecules in parallel, dramatically accelerating the pace of research and development [1] [2].

This shift has been driven by necessity. Traditional methods, while systematic, proved inadequate for exploring complex, multidimensional chemical spaces where subtle variations in catalyst structure, substrate, and reaction conditions can profoundly influence outcomes [3]. The combinatorial approach, rooted in the integration of parallel synthesis, automation, and sophisticated analytics, has enabled researchers to navigate this complexity with unprecedented efficiency [1]. Within pharmaceutical research, catalyst discovery, and materials science, these methodologies have reduced discovery timelines and opened new frontiers for exploring chemical reactivity.

The Paradigm Shift in Methodology

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

The conventional "one-variable-at-a-time" (OVAT) approach to chemical optimization involved systematically altering a single parameter while holding all others constant. This method, while conceptually straightforward, suffers from significant inefficiencies in exploring complex experimental spaces where multiple factors interact non-linearly [4]. In catalyst development, this often translated to laborious, sequential testing of catalytic combinations through "trial-and-error tactics" that were "tiresome, time-wasting, and usually one-at-a-time" [1]. The OVAT approach not only consumed substantial time and resources but also risked overlooking optimal combinations due to its inability to efficiently detect synergistic or inhibitory interactions between variables.

The Combinatorial Revolution

Combinatorial chemistry represents a fundamental reimagining of chemical synthesis, defined as "the systematic and repetitive, covalent connection of a set of different 'building blocks' of varying structures to each other to yield a large array of diverse molecular entities" [2]. This methodology transforms chemical exploration from a linear process to a parallelized one, enabling the simultaneous creation and evaluation of numerous compounds.

The theoretical underpinnings of this approach extend beyond chemistry, finding resonance in what technology theorist Brian Arthur describes as "combinatorial evolution" – the principle that novel technologies arise primarily through novel combinations of existing components [5]. Similarly, in chemistry, new catalysts and reactions often emerge from innovative combinations of known ligands, metal centers, and reaction conditions.

The historical development of combinatorial methods reveals several key milestones that enabled this paradigm shift:

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Combinatorial Methodology

| Year | Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1909 | Mittasch's ammonia catalyst discovery [1] | Early example of high-throughput screening; ~6,500 tests to identify iron catalysts |

| 1963 | Merrifield's solid-phase synthesis [2] | Enabled iterative synthesis on insoluble supports; Nobel Prize 1984 |

| 1984 | Geysen's multi-pin peptide synthesis [2] | First spatially addressed peptide arrays |

| 1985 | Houghten's "tea bag" method [2] | Parallel peptide synthesis in mesh containers |

| 1988 | Furka's split-and-pool synthesis [2] | Exponential library generation from limited reactions |

| 1990s | Expansion to small molecule libraries [2] | Broadened application beyond peptides to drug-like compounds |

| 2000s+ | Integration of automation & informatics [1] | Enabled true high-throughput experimentation (HTE) |

The migration of combinatorial thinking from pharmaceutical discovery to other domains like catalysis and materials science represents a classic example of technology combinatoriality, where methodologies developed in one field become building blocks for innovation in another [5].

Key Technological Enablers

Synthesis and Reaction Platforms

Advanced reactor systems have been crucial for implementing combinatorial principles in practical laboratory settings. These platforms enable parallel reaction execution under controlled conditions while minimizing reagent consumption.

Stop-Flow Micro-Tubing (SFMT) Reactors combine advantages of both batch and continuous flow systems, featuring micro-tubing with shut-off valves at both ends [6]. This configuration allows for the creation of discrete, isolated reaction environments that are ideal for small-scale screening. SFMT reactors demonstrate particular utility for reactions involving gases or photochemical transformations, where their design enhances mass transfer and light penetration compared to conventional batch reactors [6]. For example, in Sonogashira couplings with acetylene gas, SFMT reactors achieved better conversion and selectivity than batch reactors, with screening completed in less than three hours across multiple conditions [6].

Microtiter Plates and Automated Parallel Synthesizers provide standardized formats for conducting numerous reactions simultaneously. When integrated with robotic liquid handling systems, these platforms enable the rapid assembly of reaction arrays varying catalyst, substrate, and condition parameters [4]. The pharmaceutical industry has extensively adopted these systems for library synthesis and reaction optimization, significantly reducing the time from target conception to compound testing.

Analytical and Screening Methodologies

The value of combinatorial synthesis would be limited without corresponding advances in analytical techniques capable of rapidly evaluating library performance. Several key methodologies have emerged as enablers of high-throughput screening in catalysis.

Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS) has recently been applied to one of the most challenging problems in catalytic screening: the rapid determination of enantiomeric excess (ee). Traditional chiral chromatography requires lengthy separation times that bottleneck throughput. IM-MS escapes this limitation by performing gas-phase separations on the millisecond timescale [3]. When combined with a diastereoisomerization strategy using chiral derivatizing agents, IM-MS can accurately determine ee values with a median error of <±1% at speeds of approximately 1,000 reactions per day [3]. This represents a 100-fold increase over conventional methods, enabling comprehensive mapping of asymmetric catalytic spaces.

In Situ Enzymatic Screening (ISES) utilizes biological recognition to provide real-time reaction monitoring without the need for aliquot removal or workup. This biphasic system features an organic reaction layer adjacent to an aqueous reporting layer containing enzymes that convert reaction products or byproducts into detectable spectroscopic signals [7]. For instance, reactions releasing ethanol or methanol can be monitored through enzymatic oxidation coupled to NAD(P)H production, detectable at 340 nm. The ISES approach has been successfully applied to screen metal-ligand combinations for allylic amination and hydrolytic kinetic resolution of epoxides, in some cases providing information on both reaction rate and enantioselectivity [7].

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Methodologies

| Method | Throughput | Key Metrics | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| IM-MS with diastereoisomerization [3] | ~1,000 reactions/day | Enantiomeric excess (ee) | Asymmetric catalysis, reaction discovery |

| In Situ Enzymatic Screening (ISES) [7] | Medium throughput | Reaction rate, enantioselectivity | Transition metal catalysis, kinetic resolutions |

| Stop-Flow Micro-Tubing Reactors [6] | Parallel condition screening | Conversion, selectivity | Photoredox catalysis, gas-liquid reactions |

| Infrared Thermography [1] | High throughput | Reaction heat | Catalyst activity screening |

Experimental Design and Data Analysis

The transition to parallel experimentation necessitated more sophisticated approaches to experimental design. Traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches have been largely supplanted by Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies that systematically vary multiple parameters simultaneously [4]. Statistical approaches such as factorial designs and response surface methodology enable researchers to efficiently explore complex variable spaces, identify significant factors, and model optimal parameter settings with far fewer experiments than required by OVAT approaches [4].

The implementation of DoE in chemical optimization typically follows a two-stage process: initial "screening" designs to identify critical variables, followed by "optimization" designs to determine their ideal levels [4]. This structured approach to experimentation has proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical process chemistry, where it has improved yields, enhanced reproducibility, and accelerated development timelines.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Ultra-High-Throughput Screening for Asymmetric Catalysis Using IM-MS

Application Note: This protocol describes a method for rapid enantiomeric excess determination of asymmetric catalytic reactions, specifically applied to the α-alkylation of aldehydes merged with photoredox and organocatalysis [3].

Principle: Enantiomeric products are converted to diastereomers via chiral derivatization, then separated and quantified using ion mobility-mass spectrometry, bypassing slow chromatographic methods.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Chiral Derivatizing Agent D3: (S)-2-((((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-phenylpropyl 4-azidobenzoate; enables diastereomer formation via CuAAC "click" chemistry

- Photocatalysts (P1-P13): 13 transition metal and organic dye-based photocatalysts

- Organocatalysts (L1-L11): 11 secondary amine organocatalysts for enamine formation

- Bromoacetophenone Derivatives (S1-S10): 10 electrophilic coupling partners

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Reaction Setup: In a 96-well plate, combine hept-6-ynal (3b, 0.05 mmol) with bromoacetophenone derivatives (S1-S10, 0.06 mmol), organocatalyst L1-L11 (10 mol%), photocatalyst P1-P13 (2 mol%), and 2,6-lutidine (0.075 mmol) in DMF (0.5 mL) [3].

Photoreaction: Place the reaction plate in a home-made photochemical reaction chamber and irradiate with blue LEDs for 12 hours at room temperature with continuous mixing [3].

Derivatization: Transfer an aliquot (10 µL) to a new 96-well plate containing chiral derivatizing agent D3 (0.06 mmol in DMF). Add CuI (0.01 mmol) and stir for 10 minutes at room temperature to complete the diastereoisomerization via CuAAC [3].

IM-MS Analysis: Directly inject the derivatized reaction mixture using an autosampler into the IM-MS system. Use the following parameters:

- Ionization: ESI positive mode

- Drift gas: Nitrogen

- Mobility separation: Trapped ion mobility spectrometry (TIMS)

- Detection: Time-of-flight mass analyzer [3]

Data Analysis: Extract ion mobilograms (EIMs) for the sodium adducts of the diastereomeric products. Determine peak area ratios through curve fitting. Calculate enantiomeric excess using the formula: ee (%) = |(A₁ - A₂)|/(A₁ + A₂) × 100, where A₁ and A₂ represent peak areas of the diastereomeric ions [3].

Protocol 2: Reaction Screening Using Stop-Flow Micro-Tubing Reactors

Application Note: This protocol describes the use of SFMT reactors for screening gaseous and photochemical reactions, specifically applied to Sonogashira coupling and photoredox transformations [6].

Principle: Micro-tubing reactors with shut-off valves create isolated reaction environments that enhance gas solubility and light penetration while enabling parallel condition screening.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- PFA Tubing: Chemically inert, gas-impermeable micro-tubing (300-340 cm)

- Shut-off Valves: Enable isolation and pressurization of reaction mixtures

- Acetylene Gas Source: With pressure regulation and needle valve control

- Blue LED Strip: Provides uniform irradiation for photoredox reactions

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Reactor Assembly: Wrap 300 cm of high-purity PFA tubing (0.75 mm inner diameter) into a coil and secure with zip ties. Attach shut-off valves to both ends [6].

Reaction Mixture Preparation: Combine 4-iodoanisole (58.5 mg, 0.25 mmol), Bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium chloride (8.5 mg, 0.012 mmol), copper iodide (1 mg, 0.005 mmol), and DIPEA (80 µL, 0.5 mmol) in DMSO (2.5 mL). Degas the mixture with argon for 15 minutes [6].

Reactor Loading: Connect the SFMT reactor to an acetylene gas source with back-pressure regulator. Draw the reaction mixture into an 8 mL stainless steel syringe and mount on a syringe pump. Simultaneously pump the reaction mixture (300 µL/min) and acetylene gas at a 1:1 liquid-to-gas ratio into the reactor until filled [6].

Reaction Execution: Close both shut-off valves and immerse the reactor coil in a silicone oil bath heated to 80°C for 1 hour, keeping valves clear of oil [6].

Product Recovery: Connect a syringe to one valve and push the reaction mixture into a collection vial. Rinse the tubing with diethyl ether (4 mL) and combine with the reaction mixture [6].

Analysis: Wash the combined organic phases with saturated ammonium chloride solution (4 mL), dry over MgSO₄, and analyze by GC-MS using an internal standard for yield determination [6].

Impact and Future Perspectives

The adoption of combinatorial methodologies has fundamentally transformed catalyst screening and reaction discovery. In heterogeneous catalysis, high-throughput approaches have enabled the rapid discovery and optimization of catalytic materials that would have been impractical to identify through sequential methods [1]. The economic impact is substantial, with catalytic processes contributing to products worth over USD 10 trillion annually to the global economy, with the catalyst market itself projected to reach USD 34 billion by 2024 [1].

In pharmaceutical research, combinatorial chemistry has "turned traditional chemistry upside down" by requiring chemists to "think in terms of simultaneously synthesizing large populations of compounds" rather than single, well-characterized molecules [2]. This shift has addressed the critical bottleneck where traditional synthesis could no longer keep pace with high-throughput biological screening capabilities.

The future trajectory of combinatorial methodologies points toward further integration of automation, artificial intelligence, and increasingly sophisticated analytical techniques. As throughput continues to increase – with methods like IM-MS approaching 1,000 analyses per day – researchers will be able to explore increasingly complex chemical spaces with unprecedented comprehensiveness [3]. This will likely accelerate the discovery of not only improved catalysts but entirely new reaction paradigms that would have remained inaccessible through one-at-a-time experimentation.

This application note details the core principles of high-throughput screening (HTS) as applied in catalyst development and drug discovery. We define the critical performance parameters—throughput, enantioselectivity, and activity—and provide standardized protocols for their quantitative assessment. Framed within the context of catalyst screening for organic reactions, this document includes structured data summaries, experimental methodologies, and visual workflows designed to equip researchers with the tools for robust assay development and data interpretation.

The empirical discovery and optimization of catalysts are fundamental to advancing synthetic organic chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where the demand for enantiopure molecules is paramount [8] [9]. Screening serves as the primary engine for this development, transforming intuition and computation into experimental validation. The effectiveness of any screening campaign hinges on a clear understanding and precise measurement of three core concepts:

- Throughput: The number of individual experiments or samples that can be processed and analyzed per unit time.

- Enantioselectivity: The ability of a catalyst to favor the production of one enantiomer over the other in a chiral product.

- Activity: A measure of the catalytic efficiency, often expressed as conversion over time or the concentration required for half-maximal response (AC~50~ or IC~50~).

These parameters are deeply interconnected. High-throughput methods enable the rapid surveying of vast chemical or biological space to identify "hits," but these hits must then be characterized for their enantioselectivity and potency to be of practical value [10] [11]. The following sections dissect each concept and provide a framework for their integrated application.

Defining and Quantifying Core Screening Parameters

Throughput

Throughput in screening is a measure of operational scale and speed, enabled by miniaturization, automation, and rapid assay readouts [10]. In HTS, liquid handling devices, robotics, and sensitive detectors are used to automatically test thousands to millions of samples in multi-well microplates (e.g., 96- to 3456-well formats) [10]. Ultra-HTS systems can analyze over 100,000 samples per day, dramatically accelerating the identification of candidate catalysts or compounds for further study [10].

Enantioselectivity

Enantioselectivity is a property of a chiral catalyst or enzyme to differentiate between enantiomeric transition states, leading to the unequal production of one stereoisomer over another [9]. It is quantitatively expressed as the enantiomeric ratio (E) or the enantiomeric excess (e.e.). For industrial applications, particularly in agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals, achieving high enantioselectivity is critical because different enantiomers of a molecule can possess vastly different biological activities [8] [9].

Activity

Activity is a measure of the catalytic potency. In enzymatic or homogeneous catalysis, it can be reported as turnover frequency (TOF) or conversion over time. In quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS), where concentration–response curves are generated for thousands of compounds, activity is often quantified by fitting data to the Hill equation to determine the AC~50~ (the concentration for half-maximal response) and E~max~ (the maximal response or efficacy) [12]. The reliability of these parameter estimates is highly dependent on assay design and data quality.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Catalyst and Biocatalyst Screening

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Measures & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Number of samples processed per day. | Low: 100s; Medium: 1,000s; High: >100,000 [10]. Governed by automation, miniaturization, and readout speed. |

| Enantioselectivity | Preference for forming one enantiomer over the other. | Enantiomeric Excess (e.e.): (\frac{[R]-[S]}{[R]+[S]} \times 100\%)Enantiomeric Ratio (E): ( = \frac{k{cat}^{fast}}{k{cat}^{slow}} ) [9]. |

| Activity (qHTS) | Potency and efficacy from a concentration-response curve. | AC~50~: Concentration for half-maximal response. E~max~: Maximal response. Hill slope (h): Curve steepness [12]. |

| Activity (Enzyme) | Catalytic efficiency. | Turnover Frequency (TOF): Molecules converted per catalyst site per unit time. |

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Screening

A Protocol for Determining Hydrolase Activity and Enantioselectivity

This protocol is adapted from a published HTS method that uses fluorescein sodium salt as a pH-sensitive indicator for the hydrolysis of chiral esters [13]. The method is sensitive, economical, and versatile for substrates derived from either chiral alcohols or chiral carboxylic acids.

Principle: The hydrolysis of acetate esters releases acetic acid, decreasing the pH of the solution. This quenches the fluorescence and optical density of fluorescein sodium salt, providing a real-time, quantitative readout of reaction progress [13].

Materials:

- Substrates: (R,S)-1-phenylethyl acetate (for initial activity screen), pure (R)- and (S)-1-phenylethyl acetate (for enantioselectivity determination).

- Indicator: Fluorescein sodium salt solution (0.06 mM in 10 mM phosphate buffer, PBS).

- Enzymes: Library of hydrolases (e.g., lipases, esterases) expressed and purified or in cell lysates.

- Equipment: 96- or 384-well microplates, plate reader capable of measuring absorbance or fluorescence, liquid handling automation.

Procedure:

- Primary Activity Screen (with Racemate): a. In each well of a microplate, combine 93 µL of fluorescein sodium salt solution and 7 µL of (R,S)-1-phenylethyl acetate substrate. b. Initiate the reaction by adding 100 µL of enzyme solution (e.g., 0.05 mM protein concentration). c. Incubate the plate at the desired temperature and monitor the decrease in optical density at 495 nm over time. d. Identify "hit" enzymes that show a significant and rapid decrease in OD~495~ compared to negative controls (no enzyme).

- Enantioselectivity Determination (with Pure Enantiomers): a. For each "hit" enzyme from Step 1, set up two separate reaction wells: one containing the pure (R)-substrate and the other the pure (S)-substrate. b. Follow the same procedure as in Step 1, measuring the initial rate of OD~495~ decrease for each enantiomer. c. The enantioselectivity (E value) is calculated from the ratio of the initial rates for the two pure enantiomers: ( E \approx \frac{V{S}}{V{R}} ) (or vice-versa, depending on which enantiomer is faster).

Advantages: This method uses an inexpensive indicator, avoids the need for specialized fluorescent substrates, and reduces cost and time by using racemates in the primary screen [13].

Workflow for a Generic qHTS Campaign

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a typical qHTS campaign for catalyst or compound screening, from library preparation to hit validation.

Diagram: High-Level qHTS Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the screening protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS and Enantioselectivity Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein Sodium Salt | pH-sensitive indicator; fluorescence and OD quench with decreasing pH. | Label-free detection of hydrolytic enzyme activity and enantioselectivity [13]. |

| Chiral Substrates (Acetates) | Esters of chiral alcohols or acids; racemic and enantiopure forms. | Probes for determining hydrolase activity and enantioselectivity (E value) [13]. |

| Biomacromolecule Sensors | Enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids used as chiral sensors. | Providing high-sensitivity, chiral readouts for product stereochemistry in reaction discovery [11]. |

| Chiral Derivatizing Agents | Chiral compounds that convert enantiomers into diastereomers. | Enabling separation and analysis of enantiomers by standard chromatographic or NMR methods [9]. |

| Metal Triflates | Lewis acid catalysts (e.g., Sc(OTf)~3~, Yb(OTf)~3~). | Efficient catalysts for imine-linked COF synthesis, illustrating catalyst screening in materials science [14]. |

| Multi-Well Microplates | Miniaturized assay platforms (96- to 3456-well). | Foundation for HTS, enabling parallel processing of thousands of reactions [10]. |

Critical Data Analysis and Statistical Considerations

Challenges in Parameter Estimation from qHTS Data

The Hill equation is widely used to model sigmoidal concentration-response data in qHTS. However, parameter estimates like AC~50~ and E~max~ can be highly variable and unreliable if the experimental design is suboptimal [12]. Key challenges include:

- Poor Asymptote Definition: If the tested concentration range fails to define at least one of the upper or lower response asymptotes, AC~50~ estimates can span several orders of magnitude, as shown in simulation studies [12].

- Impact of Replicates: Increasing the number of experimental replicates (n) significantly improves the precision of AC~50~ and E~max~ estimates, narrowing confidence intervals [12].

- Systematic Error: Artifacts like signal bleaching, compound carryover, and well location effects can introduce bias that is not mitigated by simple replication [12].

Table 3: Impact of Sample Size (n) on AC~50~ and E~max~ Estimation Precision (Simulated Data) [12]

| True AC~50~ (µM) | True E~max~ (%) | n | Mean [95% CI] for AC~50~ | Mean [95% CI] for E~max~ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | 50 | 1 | 6.18e-05 [4.69e-10, 8.14] | 50.21 [45.77, 54.74] |

| 0.001 | 50 | 3 | 1.74e-04 [5.59e-08, 0.54] | 50.03 [44.90, 55.17] |

| 0.001 | 50 | 5 | 2.91e-04 [5.84e-07, 0.15] | 50.05 [47.54, 52.57] |

| 0.1 | 50 | 1 | 0.10 [0.04, 0.23] | 50.64 [12.29, 88.99] |

| 0.1 | 50 | 3 | 0.10 [0.06, 0.16] | 50.07 [46.44, 53.71] |

| 0.1 | 50 | 5 | 0.10 [0.07, 0.14] | 50.04 [48.23, 51.85] |

Decision Pathway for Screening Data Analysis

The following diagram outlines a logical process for analyzing and interpreting screening data, from raw data processing to final activity calls.

Diagram: Screening Data Analysis Pathway

Application Note: Virtual High-Throughput Screening (vHTS) for Hit Identification

Background and Principle

Traditional high-throughput screening (HTS), while foundational to drug discovery, is constrained by the physical availability of compounds, high costs, and low hit rates, typically below 1% [15]. Virtual High-Throughput Screening (vHTS) overcomes these limitations by leveraging deep learning models to computationally evaluate ultra-large, synthesis-on-demand chemical libraries before any physical synthesis occurs [16]. This paradigm shift allows researchers to access trillions of hypothetical molecules, focusing experimental efforts only on the most promising candidates.

Quantitative Performance of AI-Driven Screening

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AI-Driven Screening vs. Traditional HTS

| Screening Method | Library Size | Average Hit Rate | Notable Success Rate | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional HTS | ~100,000s of physical compounds [15] | < 1% [15] | N/A | Direct experimental measurement |

| AI-Driven vHTS (Internal Portfolio) | 16 billion virtual compounds [16] | 6.7% (Dose-Response) [16] | 91% of projects yielded reconfirmed hits [16] | Accesses novel scaffolds, thousands of times larger chemical space |

| AI-Driven vHTS (Academic Validation) | 20+ billion virtual compounds [16] | 7.6% [16] | Successful across 318 diverse targets [16] | Broad applicability across therapeutic areas and protein families |

A landmark study involving 318 prospective projects demonstrated that an AtomNet convolutional neural network could successfully identify novel bioactive hits across every major therapeutic area and protein class [16]. This approach proved effective even for targets without known binders or high-quality crystal structures, challenging historical limitations of computational methods [16].

Detailed Protocol: Implementing an AI-Driven Virtual Screen

Objective: To identify novel hit compounds for a protein target of interest from a multi-billion compound virtual library.

Materials and Software:

- Target Structure: A 3D structure of the target protein (from X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or a high-quality homology model).

- Virtual Chemical Library: Access to a synthesis-on-demand virtual library (e.g., Enamine's 16-billion compound space).

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster (requiring ~40,000 CPUs, ~3,500 GPUs, ~150 TB memory).

- AI Model: A trained deep learning system for structure-based drug design (e.g., AtomNet).

Procedure:

- Target Preparation:

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and defining binding sites if known.

- Library Preparation:

- Generate credible 3D conformations for each compound in the virtual library.

- Apply pre-filters to remove molecules with undesirable properties (e.g., reactive functional groups, poor drug-likeness) or those that are too similar to known binders of the target or its homologs.

- Neural Network Scoring:

- The AI model analyzes and scores the 3D coordinates of each generated protein-ligand complex, producing a list of ligands ranked by their predicted binding probability. This step involves over 40,000 CPUs and 3,500 GPUs [16].

- Hit Selection and Clustering:

- Select the top-ranked molecules from the scored library.

- Cluster these top hits to ensure chemical and structural diversity.

- Algorithmically select the highest-scoring exemplars from each cluster. Crucially, this step should be performed without manual cherry-picking to avoid bias [16].

- Synthesis and Validation:

- Procure the selected compounds from a synthesis-on-demand provider (e.g., Enamine).

- Validate compound purity (>90% by LC-MS) and identity (NMR) before biological testing [16].

- Test compounds in a single-dose primary assay, followed by dose-response studies for confirmed hits.

Critical Steps for Success:

- Ensure the quality of the input protein structure, as this directly impacts the accuracy of predictions.

- The computational workflow must be designed for massive parallelization to handle the terabyte-scale data transfers and scoring of billions of compounds [16].

- Incorporate standard assay additives (e.g., Tween-20, Triton-X 100, DTT) during experimental validation to mitigate common assay interference mechanisms [16].

Application Note: Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Condition Screening

Background and Principle

Optimizing chemical reactions involves navigating a high-dimensional space of variables (e.g., concentration, temperature, time), which is traditionally labor-intensive and inefficient. Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a machine learning strategy that addresses this by building a probabilistic model of the reaction landscape and intelligently selecting the next experiments to perform, balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of known promising conditions [17]. This approach is particularly powerful when integrated with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms, creating a closed-loop, self-driving laboratory [17].

Case Study: Optimizing a Sulfonation Reaction

In a recent application, researchers employed flexible batch BO to optimize the sulfonation reaction of fluorenone derivatives for redox flow batteries [17]. The goal was to identify conditions that maximize yield under milder temperatures (<170 °C) to mitigate the hazards of fuming sulfuric acid.

Table 2: Optimization Parameters and Outcomes for Sulfonation Reaction [17]

| Parameter | Search Space | Optimal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Time | 30.0 - 600 min | Part of identified high-yield conditions |

| Reaction Temperature | 20.0 - 170.0 °C | < 170 °C (milder conditions) |

| Sulfuric Acid Concentration | 75.0 - 100.0 % | Part of identified high-yield conditions |

| Analyte Concentration | 33.0 - 100 mg mL⁻¹ | Part of identified high-yield conditions |

| Key Outcome | 11 conditions identified achieving yield > 90% under mild temperatures |

Detailed Protocol: Flexible Batch Bayesian Optimization on an HTE Platform

Objective: To autonomously optimize a multi-step chemical synthesis (e.g., sulfonation) where hardware imposes different batch-size constraints on variables.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-Throughput Robotic Platform: Equipped with liquid handlers for formulation and multiple heating blocks for temperature control.

- Characterization Instrument: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system for automated yield analysis.

- Computational Environment: Python with libraries for Bayesian Optimization (e.g., Scikit-learn, GPyTorch) and clustering.

Procedure:

- Define Search Space: Identify the key variables (e.g., time, temperature, reagent concentrations) and their realistic boundaries based on chemical knowledge and literature.

- Initial Sampling: Generate the first batch of experimental conditions (e.g., 15 unique conditions) using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to ensure the space is evenly explored [17].

- Hardware-Aware Condition Assignment:

- Challenge: The LHS may suggest 15 different temperatures, but the hardware only has 3 heating blocks.

- Solution: Cluster the LHS-generated temperatures into 3 groups and assign all conditions within a cluster to the centroid temperature of that cluster [17].

- Execution and Analysis:

- The robotic platform executes the synthesis according to the assigned conditions.

- Products are automatically transferred to HPLC for analysis, and yields are calculated from the chromatograms.

- Model Training and Next-Batch Selection:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model using the collected condition-yield data.

- Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to propose the next set of promising conditions.

- Re-cluster the proposed conditions to fit hardware constraints (e.g., map to 3 available temperatures).

- Iteration: Repeat steps 4 and 5 until a satisfactory yield is achieved or the resource budget is exhausted.

Critical Steps for Success:

- The flexibility of the BO algorithm is key. It must accommodate the fact that the number of compositions that can be explored per round is limited by the number of available wells, while temperature constraints depend on the number of heaters [17].

- Including replication (e.g., n=3) in the experimental design is crucial for robust yield measurement and modeling noise.

- The entire digital and physical workflow must be integrated into a seamless closed-loop system to minimize human intervention.

Application Note: ML-Powered Discovery from Archived Data

Background and Principle

A transformative "third strategy" in chemical discovery involves mining existing, often underutilized, experimental data to uncover novel reactions or phenomena without conducting new experiments [18]. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) datasets are a prime candidate, as laboratories routinely accumulate terabytes of archived spectra. A machine-learning-powered search engine can decipher this data at scale, identifying potential reaction products that were previously overlooked in manual analyses [18].

Protocol: Reaction Discovery via Mass Spectrometry Data Mining

Objective: To discover previously unknown organic reactions by systematically searching through a large archive of HRMS data.

Materials and Software:

- HRMS Data Archive: A large-scale database of historical HRMS spectra (e.g., 8 TB of 22,000 spectra).

- Search Engine: A specialized ML-powered tool (e.g., MEDUSA Search) [18].

- Hypothesis Generation: Knowledge of breakable bonds and fragment recombination, or automated methods like BRICS fragmentation or LLMs.

Procedure:

- Generate Reaction Hypotheses:

- Based on chemical knowledge, define potential reaction pathways by considering breakable bonds and the recombination of corresponding fragments. Automated methods can also be used to generate hypotheses [18].

- Calculate Theoretical Isotopic Patterns:

- For each hypothetical product ion (defined by its chemical formula and charge), calculate its theoretical "isotopic pattern."

- Coarse Spectra Search:

- Use inverted indexes to rapidly identify candidate mass spectra from the archive that contain the two most abundant isotopologue peaks of the theoretical pattern (within a 0.001 m/z tolerance) [18].

- Isotopic Distribution Search:

- For each candidate spectrum, run a finer search to match the full theoretical isotopic distribution against the experimental data, calculating a similarity metric (e.g., cosine distance).

- ML-Powered Filtering:

- Apply a machine learning model to estimate an ion-presence threshold and filter out false positive matches. The ML models in MEDUSA Search are trained on synthetic MS data to simulate instrument errors, avoiding the need for large manually annotated datasets [18].

- Validation:

- For matched ions of high interest, conduct follow-up experiments (e.g., NMR or MS/MS) to confirm the structure and validate the newly discovered reaction.

Critical Steps for Success:

- The search algorithm must be highly optimized to process tera-scale datasets in a reasonable time. The multilevel architecture of MEDUSA Search, inspired by web search engines, is crucial for this [18].

- The use of isotopic distribution patterns is critical for reducing false positive detections compared to methods that rely on single m/z values.

- This approach enables "experimentation in the past," repurposing existing data for new discoveries in a highly resource-efficient manner [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Exploration Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis-on-Demand Libraries | Provides access to billions of novel, make-on-demand virtual compounds for screening. | Virtual HTS against a new protein target [16]. |

| Fluorinated Oil & PEG-PFPE Surfactant | Creates a stable, biocompatible emulsion for microfluidic droplet-based screening. | High-throughput optimization of cell-free gene expression systems [19]. |

| Poloxamer 188 (P-188) | A non-ionic triblock-copolymer surfactant used to stabilize emulsions in droplet assays. | Preventing coalescence of picoliter reactors during incubation [19]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol 6000 (PEG-6000) | A biocompatible crowding reagent that improves stability and performance in confined volumes. | Enhancing yields in droplet-based CFE reactions [19]. |

| Crude Cellular Extracts (E. coli, B. subtilis) | The active lysate containing the transcriptional/translational machinery for cell-free systems. | Prototyping genetic circuits or optimizing protein production in a CFE system [19]. |

In the field of synthetic organic chemistry, the discovery and optimization of new reactions and catalysts are fundamental to advancing drug development and manufacturing. A central and formidable challenge in this endeavor is the effective navigation of the multidimensional chemical space, a complex matrix formed by the vast number of possible combinations between catalysts, substrates, additives, and reaction conditions [20]. Even modest structural changes to any of these variables can profoundly impact the experimental outcome, making exhaustive experimentation impractical [21] [20]. This application note details the core challenges of this navigation and provides structured protocols and data from contemporary screening methodologies that accelerate the mapping of this expansive reactivity landscape.

Quantitative Comparison of Screening Methodologies

The selection of a screening method is critical, as it dictates the throughput, information content, and ultimately the success of a reaction discovery campaign. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of modern screening approaches, highlighting their key characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of High-Throughput Screening Methods for Reaction Discovery

| Screening Method | Analysis Speed | Key Metric | Accuracy (Median Error) | Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM-MS with Diastereomerization [20] | ~1,000 reactions/day | Enantiomeric Excess (ee) | < ±1% | Direct ee determination, high sensitivity |

| Closed-Loop ML & Robotics [21] | Data-guided, iterative | Reaction Yield | N/A (Doubled average yield in benchmark) | High-dimensional optimization |

| Chiral Chromatography [20] | Bottleneck for HTS | Enantiomeric Excess (ee) | High (Benchmark) | General and reliable, but slow |

| Biomacromolecule-Assisted [11] | Varies by assay (e.g., cat-ELISA) | Product Chirality / Formation | High selectivity and sensitivity | High sensitivity, chiral readout |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Ultra-High-Throughput ee Determination using Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS)

This protocol enables the rapid screening of asymmetric reactions by overcoming the speed limitations of chiral chromatography [20].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for IM-MS-Based Enantiomeric Excess Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chiral Resolving Reagent D3 | Derivatizes enantiomeric products into diastereomers for IM-MS separation. |

| Derivatizable Substrate (e.g., hept-6-ynal) | Contains an alkynyl group for rapid, chemoselective derivatization via CuAAC. |

| Copper(I) Catalyst (CuAAC) | Facilitates the click chemistry for fast and quantitative derivatization. |

| 96-/384-Well Plate Microreactors | Enables parallel reaction setup and high-throughput automation. |

| Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry (TIMS) | Provides millisecond-scale gas-phase separation of diastereomers. |

Procedure

- Reaction Setup: Conduct parallel reactions in a 96-well microreactor plate. A home-made photochemical reaction chamber compatible with the plate format is used for photoredox reactions [20].

- Post-Reaction Derivatization: To each reaction well, add the chiral resolving reagent D3 and a Copper(I) catalyst to initiate the CuAAC "click" reaction. Incubate for approximately 10 minutes to quantitatively convert enantiomeric products into diastereomers [20].

- Automated Analysis: Use a well-plate autosampler to directly inject the derivatized solutions into the IM-MS system.

- Data Acquisition & Analysis:

- Acquire extracted ion mobilograms (EIMs) for the diastereomer adduct ions.

- The enantiomeric excess (ee) is calculated directly from the peak area ratio of the derived diastereoisomers in the EIMs. A linear correlation between the molar ratio of enantiomers and the diastereoisomer peak area ratio has been validated, allowing for accurate ee determination without standard curves [20].

Workflow Visualization

Protocol: Closed-Loop Optimization for Reaction Condition Discovery

This protocol outlines a machine learning-driven approach to efficiently search high-dimensional condition spaces [21].

Procedure

- Initial Experimental Design: Select a diverse subset of reaction conditions from the high-dimensional matrix (e.g., solvent, ligand, base, concentration) to form an initial dataset.

- Robotic Experimentation: Execute the designed experiments using an automated robotic platform to ensure reproducibility and collect yield data.

- Machine Learning Model Training: Train an uncertainty-minimizing machine learning model on the collected experimental data. The model learns the complex relationships between reaction conditions and outcomes.

- Model-Guided Down-Selection: Use the trained model to predict the performance of a vast number of untested condition combinations and select the most promising ones for the next iteration.

- Iterative Closed-Loop: The selected conditions are automatically executed by the robotic system, with the new data fed back to retrain and improve the ML model. This loop continues until optimal conditions are identified [21].

Workflow Visualization

Application in Catalyst Discovery: A Case Study

The IM-MS protocol was applied to map the chemical space of the direct asymmetric α-alkylation of aldehydes merged with photoredox and organocatalysis [20].

- Scale of Study: The platform orthogonally combined 10 bromoacetophenone substrates, 11 organocatalysts, and 13 photocatalysts, resulting in a comprehensive analysis of 1,430 individual reactions [20].

- Outcome: This high-throughput mapping led to the discovery of a novel class of 1,2-diphenylethane-1,2-diamine-based sulfonamide primary amine organocatalysts exhibiting high enantioselectivity. The mechanism for high selectivity was further elucidated through computational chemistry [20].

This case demonstrates the power of ultra-high-throughput methodologies to navigate multidimensional spaces that are impractical to explore with conventional methods, enabling the discovery of new catalytic systems and revealing their generality across different substrates.

A Guide to High-Throughput and AI-Powered Screening Platforms

Biomacromolecule-assisted screening represents a powerful empirical approach in synthetic organic chemistry for reaction discovery and catalyst optimization. These methods leverage the innate molecular recognition capabilities of biological polymers—enzymes, antibodies, and nucleic acids—to provide sensitive, selective readouts for chemical reactions [11]. These biomacromolecules function as exquisite sensors, capitalizing on their native chirality and specific binding properties to detect reaction products with high sensitivity [11]. This approach has uncovered valuable new chemical transformations that might otherwise remain undiscovered through purely rational design methods, supporting the iterative nature of reaction development in both academic and industrial process chemistry settings [11].

The value of these screening methodologies is particularly evident in pharmaceutical development, where they have contributed to processes recognized with Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge awards, such as the enzymatic reductive amination route to Sitagliptin [11]. As the field continues to evolve, biomacromolecule-assisted screening provides complementary approaches to computational and machine-learning methods, enabling researchers to explore new reactivity space and identify novel catalytic transformations [11].

Principles of Biomacromolecular Sensing

Fundamental Biosensing Components

All biosensing platforms, including those used for reaction screening, consist of two crucial components: a recognition layer containing biological elements that interact specifically with the desired analyte, and a transducer that converts the biological response into a quantifiable signal [22]. In the context of reaction screening, the analyte is typically a product of the catalytic transformation being studied.

Biomacromolecular sensors achieve their remarkable specificity through different mechanisms:

- Enzymes leverage their engineered active sites for specific substrate recognition and catalytic conversion

- Antibodies utilize high-affinity antigen-binding sites with dissociation constants ranging from 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹¹ M [22]

- Nucleic acids employ precise base-pairing rules for complementary strand hybridization

The chiral nature of these biomacromolecules makes them particularly valuable for assessing stereoselectivity in asymmetric synthesis, providing critical information about enantiomeric excess alongside reaction conversion [11].

Transduction Mechanisms

Different transduction platforms transform molecular recognition events into measurable signals:

Table 1: Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms for Reaction Screening

| Transducer Type | Detection Principle | Applications in Reaction Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Optical | Measures changes in light properties | Colorimetric/fluorescent readouts of product formation |

| Electrochemical | Detects electrical changes from binding events | Direct monitoring of redox-active products |

| Mass-based (Piezoelectric) | Measures mass shift from biomolecular interaction | Label-free detection of product binding |

Enzyme-Assisted Screening

In Situ Enzymatic Screening (ISES)

In Situ Enzymatic Screening (ISES) employs enzymes as coupled reporters to detect specific functional groups or chiral products generated in catalytic reactions. This method typically yields UV-spectrophotometric or visible colorimetric readouts, enabling rapid assessment of reaction success [11].

Protocol: ISES for Asymmetric Reaction Screening

- Reaction Setup: In a 96-well microtiter plate, set up catalytic reactions in 100-200 μL volumes containing substrates, catalysts, and appropriate solvents

- Enzymatic Detection: Terminate reactions after appropriate time, then add:

- 50 μL of enzyme preparation specific to the expected product

- 100 μL of coupled chromogenic assay mixture

- Appropriate cofactors for the enzymatic reaction

- Incubation: Incubate at 30°C for 15-60 minutes

- Readout: Measure absorbance or fluorescence using a plate reader

- Data Analysis: Correlate signal intensity with product formation and enantiopurity using appropriate standards

Key Applications: ISES facilitated the discovery of the first Ni(0)-mediated asymmetric allylic amination and a novel thiocyanopalladation/carbocyclization transformation where both C-SCN and C-C bonds are formed sequentially [11].

Antibody-Assisted Screening (cat-ELISA)

Principles of cat-ELISA

Catalytic Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (cat-ELISA) utilizes antibodies raised against specific reaction products to screen for successful catalytic transformations [11]. This approach leverages the immune system's ability to generate highly specific immunoglobulins that can distinguish subtle structural differences in small molecules.

Antibody Immobilization Strategies

Effective antibody-based biosensors require careful optimization of surface immobilization to maintain antibody functionality:

Table 2: Antibody Immobilization Methods for cat-ELISA

| Immobilization Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive Absorption | Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions | Simple procedure, minimal antibody modification | Random orientation may reduce binding capacity |

| Covalent Binding | Chemical cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, carbodiimide, or maleimide succinimide esters | Stable attachment, commercial surfaces available | May affect binding sites if not properly oriented |

| Matrix Capture | Entrapment in polymeric gels (starch, cellulose, polyacrylamide) | High loading capacity, maintains antibody activity | Potential diffusion limitations |

| Affinity Labels | Genetic fusion to peptides/proteins with specific binding partners | Controlled orientation, easier purification | Requires recombinant antibody engineering |

Protocol: cat-ELISA for Reaction Discovery

- Plate Preparation:

- Coat 96-well ELISA plates with capture antibody (1-10 μg/mL in PBS buffer)

- Incubate overnight at 4°C, then block with 1% BSA for 2 hours

- Reaction and Detection:

- Add catalytic reaction mixtures (50-100 μL) to wells, incubate 1 hour

- Wash 3× with PBS-Tween buffer

- Add detection antibody conjugated to reporter enzyme (e.g., horseradish peroxidase)

- Incubate 1 hour, wash thoroughly

- Signal Development:

- Add enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for colorimetric readout)

- Incubate 15-30 minutes, stop reaction with acid

- Measure absorbance with plate reader

- Hit Identification: Compare signals to positive and negative controls

Key Applications: cat-ELISA screening has identified new classes of sydnone-alkyne cycloadditions and other valuable transformations [11].

DNA-Assisted Screening

DNA-Encoded Library Screening

DNA-assisted screening employs nucleic acids as both templates and barcodes for chemical reactions [11]. This approach facilitates the screening of vast chemical libraries by converting bimolecular reactions into a pseudo-unimolecular format through templation, and allows parallel screening by tracking reactants via DNA barcodes [11].

DNA-Based Biosensor Platforms

DNA biosensors (genosensors) typically use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules as recognition elements that hybridize with complementary strands with high specificity and efficiency [22]. These platforms offer advantages over traditional hybridization methods like Southern blotting, providing greater sensitivity, reusability, and potential for real-time detection [22].

Protocol: DNA-Encoded Library Screening for Catalyst Discovery

- Library Preparation:

- Encode chemical substrates with unique DNA sequences

- Combine encoded substrates with candidate catalysts

- Reaction Execution:

- Perform reactions under desired conditions

- Use DNA templation to facilitate bimolecular interactions

- Selection Process:

- Immobilize reaction products via DNA hybridization

- Wash away unreacted starting materials

- Elute and amplify bound DNA sequences

- Analysis:

- Sequence amplified DNA to identify successful reactions

- Decode sequences to determine effective catalyst-substrate pairs

Transducer Platforms for DNA Biosensors:

- Optical fibers with fluorescent labels (e.g., ethidium bromide)

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for label-free detection

- Evanescent wave sensors for PCR product detection

- Quantum dots for enhanced fluorescence sensitivity [22]

Key Applications: DNA-encoded screening has uncovered oxidative Pd-mediated amido-alkyne/alkene coupling reactions and other interesting transformations [11].

Experimental Design and Workflows

Integrated Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for biomacromolecule-assisted screening:

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) Data Visualization

For screening campaigns generating large datasets, three-dimensional visualization tools like qHTS Waterfall Plots enable comprehensive data analysis. These plots incorporate compound identity, concentration, and response efficacy to reveal patterns across thousands of concentration-response curves [23].

Protocol: qHTS Waterfall Plot Implementation

- Data Formatting:

- Prepare data file with columns: FitOutput, CompID, Readout, LogAC50M, S0, SInf, Hill_Slope

- Include concentration columns (LogConcM) and response data (Data0, Data1,...DataN)

- Specify format as 'genericqhts' or 'ncatsqhts'

- Software Execution:

- Use R package:

qHTSWaterfallor Shiny application - Load formatted data file

- Customize display parameters (colors, point sizes, axis formatting)

- Use R package:

- Data Interpretation:

- Identify active responses passing curation thresholds

- Group compounds by chemotype or response characteristics

- Analyze potency (AC50) and efficacy (S_Inf) relationships

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biomacromolecule-Assisted Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Preparations | Dehydrogenases, oxidoreductases, transaminases | Product detection through coupled assays |

| Antibody Types | Polyclonal, monoclonal, recombinant antibodies | Specific product capture and detection |

| Immobilization Matrices | Polyacrylamide, silica gel, alginate, gold surfaces | Solid supports for bioreceptor attachment |

| Detection Reagents | HRP conjugates, fluorescent tags, quantum dots | Signal generation for readout |

| DNA Components | Oligonucleotides, primers, DNA polymerases | Encoding, amplification, and detection |

| Sensor Surfaces | Gold, glass, iron oxide, platinum chips | Transducer platforms for biosensors |

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

Table 4: Biomacromolecular Screening Method Comparison

| Parameter | Enzyme Screening | Antibody Screening | DNA Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | High (μM-nM) | Very High (pM) | High (nM) |

| Chirality Assessment | Excellent | Excellent | Limited |

| Throughput Capacity | High (96-384 well) | Medium (96 well) | Very High (millions) |

| Development Time | Weeks | Months (antibody production) | Weeks |

| Key Applications | Functional group detection, stereoselectivity | Specific product formation | Library screening, reaction discovery |

| Required Expertise | Enzyme kinetics, assay development | Immunoassays, surface chemistry | Molecular biology, sequencing |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of biomacromolecule-assisted screening with emerging technologies represents the cutting edge of reaction discovery. Machine learning approaches are being applied to predict catalyst performance [24], while advances in biosensor design continue to improve sensitivity and throughput [22]. The combination of empirical screening with computational methods creates a powerful feedback loop for exploring chemical space.

Recent innovations include the use of graph neural networks to predict adsorption energy responses to surface strain in heterogeneous catalysts [24], demonstrating how computational approaches can complement experimental screening. As these technologies mature, we anticipate increased integration between biomacromolecular sensing and machine learning for accelerated reaction discovery and catalyst optimization.

The ongoing development of portable biosensor platforms [22] also suggests future applications in distributed reaction screening, where multiple laboratories could contribute to shared catalyst discovery campaigns using standardized biomacromolecular sensing protocols.

Within pharmaceutical development and organic synthesis, the rapid determination of enantiomeric excess (ee) is a critical bottleneck in screening and optimizing asymmetric catalysts and reactions. Traditional methods, primarily chiral high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), are limited by lengthy analysis times, necessitating extensive method development and run times of up to an hour per sample [25]. This severely restricts throughput, making the comprehensive exploration of vast chemical spaces—encompassing catalysts, substrates, and reaction conditions—impractical [26].

Ion mobility-mass spectrometry (IM-MS) has emerged as a powerful alternative for ultra-high-throughput chiral analysis. This technique separates gas-phase ions based on their size, shape, and charge as they drift through a buffer gas under an electric field. While IM-MS cannot directly separate enantiomers in an achiral environment, it can efficiently resolve diastereomers on a millisecond timescale [26]. By coupling IM-MS with a strategic derivatization step that converts enantiomeric products into diastereomeric complexes, researchers can achieve accurate ee analysis at unprecedented speeds. This protocol details the application of IM-MS for rapid chiral screening, enabling the mapping of asymmetric reaction landscapes at a rate of ~1000 reactions per day [26].

Principles of IM-MS for Chiral Analysis

The fundamental principle underlying chiral analysis with IM-MS is the conversion of enantiomers into diastereomeric species that possess different collision cross-sections (CCS), leading to different mobilities in the gas phase. Enantiomers, having identical masses and physicochemical properties in an achiral environment, cannot be distinguished by MS or standard IM-MS. However, diastereomers, which are stereoisomers that are not mirror images, have distinct physical properties.

Two primary strategies are employed to achieve this:

- Formation of Diastereomeric Complexes: A chiral selector (CS) is complexed with the analyte enantiomer in solution or the gas phase to form diastereomeric complexes (e.g., proton-bound dimers or metal-bound trimers). The differential interaction strengths between the CS and each enantiomer can result in complexes with distinct structures and sizes, and thus, different mobilities [25] [27] [28].

- Derivatization with a Chiral Resolving Agent: This method, particularly powerful for reaction screening, involves transforming the enantiomeric products of an asymmetric reaction into diastereomers via a rapid, high-yielding, and chiral-selective derivatization reaction. The resulting diastereomers are then separated by IM and quantified by MS [26].

The separation is governed by the interaction between the ion and the buffer gas. The measured drift time is used to calculate the rotationally averaged CCS ((Ω)), a quantitative descriptor of the ion's gas-phase size and shape. Diastereomers will have measurably different CCS values, allowing for their separation and quantification.

Quantitative Performance and Advantages

The IM-MS platform for ee analysis demonstrates exceptional performance metrics, offering a paradigm shift in screening efficiency compared to chiral HPLC.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of IM-MS vs. Chiral HPLC for ee Analysis

| Parameter | Chiral HPLC | IM-MS with Derivatization |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Minutes to hours per sample | ~30 seconds per sample [26] |

| Daily Throughput | Dozens of samples | ~1000 samples [26] |

| Accuracy (Median Error) | N/A (Benchmark) | < ±1% [26] |

| Quantification Correlation | N/A (Benchmark) | Pearson r = 0.9985 vs. HPLC [26] |

| Sample Consumption | Moderate to high | Low (compatible with microreactors) |

| Method Development | Lengthy column screening required | Rapid, generic method |

The key advantage is the dramatic increase in throughput without sacrificing accuracy. A direct comparison of ee values for 41 enantiomer mixtures determined by both IM-MS and chiral HPLC showed a near-perfect linear correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.9985) with a median error of only -0.62% [26]. This validates IM-MS as a highly reliable and quantitative alternative.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diastereomerization and IM-MS Analysis for Reaction Screening

This protocol is adapted from a study that screened over 1600 asymmetric alkylation reactions [26].

Workflow Overview: The overall process, from reaction to ee determination, is visualized in the following workflow.

Materials:

- Chiral Resolving Reagent D3: (S)-2-((((9H-fluoren-9-yl)methoxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-phenylpropyl 4-azidobenzoate. Synthesized as described [26].

- CuAAC Catalyst: Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO₄·5H₂O) and sodium ascorbate.

- Solvents: HPLC-grade or higher DMF, methanol, water.

- Equipment: Trapped ion mobility spectrometer coupled to a time-of-flight mass spectrometer (TIMS-TOF), 96-well plates, automated liquid handler.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reaction Execution:

- Perform asymmetric reactions in a 96-well plate format using a microreactor. Ensure one of the substrates contains an alkynyl group (e.g., hept-6-ynal) for subsequent derivatization.

- Use a home-made or commercial photochemical reaction chamber for photoredox reactions.

Post-Reaction Derivatization:

- Quench the reactions if necessary.

- Using an automated liquid handler, add a solution of the chiral resolving reagent D3 to each well.

- Add catalysts for the copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC): CuSO₄ (1-5 mol%) and sodium ascorbate (5-10 mol%).

- Allow the derivatization reaction to proceed for ~10 minutes at room temperature. This converts the enantiomeric products into diastereomers.

IM-MS Analysis:

- Directly infuse the derivatized solutions from the 96-well plate into the TIMS-TOF MS using an autosampler.

- MS Parameters: ESI in positive mode; capillary voltage, 4500 V; dry gas flow, 3 L/min; nebulizer pressure, 3 psi; capillary temperature, 275 °C.

- TIMS Parameters: Nitrogen as drift gas; accumulate and trap ions for high-resolution mobility separation. The mobility scan range should be optimized to cover the diastereomers of interest.

Data Processing and ee Determination:

- Extract ion mobilograms (EIMs) for the sodium adducts of the derivatized diastereoisomers (e.g., [M+Na]⁺).

- Use curve-fitting software to integrate the peak areas of the separated diastereomers in the EIM.

- Calculate the enantiomeric excess (ee) directly from the peak area ratio using the formula: ( ee\,(\%) = \frac{|R - S|}{(R + S)} \times 100 ) where R and S are the peak areas of the derivatized diastereomers.

Protocol 2: Metal-Free Chiral Analysis of Amino Acids

This protocol is suitable for chiral analysis of small molecules like amino acids without using metal ions, which can be challenging to work with [29].

Materials:

- Chiral Selector: N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-O-benzyl-L-serine (BBS).

- Analytes: L/D-amino acids (e.g., proline, cysteine).

- Solvent: Methanol/water (1:1, v/v) acidified with 0.1% formic acid.

- Equipment: High-resolution differential ion mobility spectrometer coupled to a mass spectrometer (DMS-MS).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare separate solutions of the chiral selector BBS and the amino acid enantiomer(s) in the methanol/water solvent.

- Mix the BBS and analyte solutions to form proton-bound diastereomeric dimer complexes, [L/D-X(BBS)+H]⁺, in solution.

DMS-MS Analysis:

- Directly infuse the mixed solution into the DMS-MS.

- MS Parameters: ESI in positive mode; optimize voltages for transmission of the proton-bound dimers.

- DMS Parameters: Systematically scan the separation voltage (SV) while applying a constant compensation voltage (CoV) offset to maximize the separation of the L- and D-enantiomer complexes. Use nitrogen as the drift gas.

Data Analysis:

- Monitor the ion intensity of the proton-bound dimer as a function of the separation field.

- Identify the specific SV/CoV conditions that baseline-separate the two diastereomeric complexes corresponding to the L- and D-enantiomers.

- Quantify the enantiomeric excess by comparing the relative intensities of the separated peaks in the ion chromatogram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for IM-MS Chiral Screening

| Item | Function / Role | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Resolving Reagent | Converts enantiomers into separable diastereomers via derivatization. | (S)-D3 Reagent [26]. Critical for creating diastereomers with sufficient CCS difference for IM separation. |

| Chiral Selector (CS) | Forms diastereomeric complexes with analytes for direct IM-MS separation. | N-tert-butoxycarbonyl-O-benzyl-L-serine (BBS) [29], Amino Acids (L-Phe, L-Pro) [27]. The choice of CS is analyte-dependent. |

| Metal Salts | Acts as a central ion to form rigid, well-defined diastereomeric complexes (e.g., trimers). | Copper(II) Chloride (CuCl₂) [27] [28], Nickel(II), Zinc(II). Enhances chiral discrimination for some analytes. |

| Derivatization Catalysts | Facilitates the covalent coupling between the analyte and the chiral resolving reagent. | CuSO₄ / Sodium Ascorbate [26]. Used for CuAAC "click" chemistry; ensures rapid and quantitative derivatization. |

| Drift Gas Modifier | Introduces a chiral environment into the drift tube for direct enantiomer separation. | (S)-(+)-2-Butanol [30]. Vapor is doped into the inert drift gas to create chiral interactions (CIMS). |

| IM-MS Instrumentation | Platform for gas-phase separation and detection. | TIMS-TOF, DMS-MS, TWIMS-MS [27] [28] [26]. High-resolution mobility systems (e.g., TIMS) are preferred for separating subtle differences. |

Application in Catalyst Discovery and Optimization

The implementation of this IM-MS screening strategy has a transformative impact on asymmetric reaction development. Its primary application is in the ultra-high-throughput mapping of multidimensional chemical spaces. For instance, it has been used to screen a matrix of 1430 reactions in a single study, investigating the synergistic effects of 11 organocatalysts, 13 photocatalysts, and 10 substrate scopes for the α-alkylation of aldehydes [26]. This scale of experimentation, which would be prohibitively time-consuming with HPLC, led to the discovery of a new class of highly enantioselective primary amine organocatalysts based on 1,2-diphenylethane-1,2-diamine sulfonamides.

The ability to rapidly generate large, high-quality datasets allows researchers to identify nuanced structure-activity relationships and catalyst generalities that would otherwise remain hidden. This accelerates the iterative cycle of catalyst design, synthesis, and evaluation, significantly shortening the development timeline for new asymmetric methodologies. The workflow is also applicable to other reaction types, including asymmetric hydrogenation, as the derivatization strategy is general for functional groups like aldehydes, amines, and alcohols [26].

Machine Learning and Causal Inference for Efficient Catalyst Pre-Screening

Application Note: Enhancing Catalyst Discovery with Machine Learning

The development of high-performance heterogeneous catalysts is challenging due to the multitude of factors influencing their performance, such as composition, support, particle size, and morphology [31]. Traditional trial-and-error methods, guided by chemical intuition, are time- and resource-intensive [31]. Machine learning (ML) is an emerging interdisciplinary field that merges computer science, statistics, and data science, offering a transformative approach to catalyst design by building models that map catalyst features to their performance [31]. This application note details how ML, particularly when combined with principles of causal inference, can create efficient pre-screening frameworks to identify promising catalyst candidates before resource-intensive experimental synthesis and testing.

ML is expected to continue adding value to catalysis research, with key application areas including [31]:

- Rapid, automated, and detailed screening of suitable materials/catalysts and operating conditions.

- Classification of reaction mechanisms and description of thermodynamic properties.

- Integration with optimization techniques for more accurate estimation of kinetic parameters.

- Extraction of complex patterns to acquire reaction rate data.

The core sequence for building ML models of catalysts involves [31]:

- Defining a dataset of various catalysts.

- Identifying their key properties (e.g., electronic structure, atomic/physical characteristics).

- Using ML tools to detect patterns and develop predictive models.

Automated ML processes show great potential in building better models, understanding catalytic mechanisms, and offering new insights into catalyst design [31]. For organic reactions research, biomacromolecule-assisted screening methods—using enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids as sensors—provide high sensitivity and selectivity, and can be integrated with ML-driven approaches to accelerate discovery [11].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Relationships in Catalyst Performance Modeling

| Performance Metric | Typical ML Algorithm Used | Input Variable Example (Intrinsic Property) | Correlation Strength (R² / Key Finding) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocarbon Conversion (Toluene Oxidation) | Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Catalyst Cost, Surface Area, Cobalt Content | Modeled successfully with ANN ensembles (600 configurations tested) | [31] |

| Hydrocarbon Conversion (Propane Oxidation) | Supervised Regression (Scikit-Learn) | Catalyst Cost, Energy Consumption, Crystallite Size | Optimization goal: Minimize cost for 97.5% conversion | [31] |

| Catalyst Selectivity | Random Forests / SVM | Metal Oxidation State, Support Acidity | Identified via feature importance analysis from ML models | [31] |

| Reaction Rate (CO₂ Reduction) | Explainable AI / Pattern Recognition | Metal Node, Organic Linker in 2D c-MOFs | Key influencing factors identified via ML analysis | [31] |

| Electrocatalyst Performance (Water Oxidation) | Explainable AI | Composition of (Ni-Fe-Co-Ce)Ox libraries | Predicts performance as alternative to RuO₂/IrOₓ | [31] |

Table 2: Comparison of Biomacromolecule-Assisted Screening Methods

| Screening Method | Biomacromolecule Used | Readout Mechanism | Throughput | Key Chemical Transformations Discovered | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Situ Enzymatic Screening (ISES) | Enzymes | UV-spectrophotometric or visible, colorimetric | High | Ni(0)-mediated asymmetric allylic amination; Thiocyanopalladation/carbocyclization | [11] |

| cat-ELISA | Antibodies | Direct fluorescence or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | High | New sydnone-alkyne cycloadditions | [11] |

| DNA-Encoded Library Screening | Nucleic Acids (DNA) | DNA sequencing (barcoding of reactants) | Very High | Oxidative Pd-mediated amido-alkyne/alkene couplings | [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Machine Learning-Guided Workflow for Catalyst Pre-Screening

Purpose: To establish a standardized procedure for using machine learning to pre-screen and optimize cobalt-based catalysts for the oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like toluene and propane [31].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Cobalt Nitrate Hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O): Primary metal precursor.

- Precipitating Agents: Includes oxalic acid (H₂C₂O₄•2H₂O), sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and ammonium hydroxide, used to precipitate different cobalt precursors (e.g., CoC₂O₄, CoCO₃, Co(OH)₂) which influence the final catalyst properties [31].

Procedure:

- Dataset Curation:

- Collect a comprehensive dataset from historical experimental data or literature. The dataset should include catalyst properties (e.g., surface area, crystallite size, cobalt content) and their corresponding performance metrics (e.g., conversion percentage, temperature of 97.5% conversion) [31].

- Ensure data quality by addressing missing values and outliers.

Feature Identification and Model Training:

- Identify key physical properties of the catalysts as input variables for the model [31].

- Utilize custom software or open-source ML libraries (e.g., Scikit-Learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch) to train a large number of models. For instance, fit the hydrocarbon conversion datasets to 600 artificial neural network (ANN) configurations and eight supervised regression algorithms from Scikit-Learn [31].

- Split data into training and testing sets to validate model performance and prevent overfitting.

Model Validation and Selection:

- Evaluate the trained models based on statistical metrics (e.g., R², Mean Absolute Error) on the test set.

- Select the best-performing neural network or regression model for subsequent optimization tasks [31].

Catalyst Optimization:

- Develop an optimization framework using the best-performing model. Use algorithms like the Compass Search to minimize objective functions, such as the combined cost of the catalyst and the energy required to achieve a target hydrocarbon conversion (e.g., 97.5%) [31].

- The optimization analysis will output a set of recommended catalyst properties that satisfy the cost and performance criteria.

Protocol: Biomacromolecule-Assisted Catalyst Screening (cat-ELISA)

Purpose: To discover new catalytic reactions or optimize catalysts using antibody-based sensing, which provides high sensitivity and selectivity, particularly for detecting specific reaction products [11].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Antibody Sensors: Antibodies raised against the target reaction product or a key intermediate. These provide selective binding.

- Enzyme-Linked Reagents: For cat-ELISA readout, enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to secondary antibodies or other binding molecules are used to generate a detectable signal [11].

- Fluorescent Dyes: If using a direct fluorescent readout, dyes that fluoresce upon antibody-analyte binding are required [11].

Procedure:

- Plate Coating: Immobilize the catalyst or reaction mixture components onto a microtiter plate.

- Reaction Incubation: Add the catalyst library and substrates to the wells, allowing the catalytic reaction to proceed.

- Detection: Add the primary antibody sensor that specifically binds to the desired product.