Multi-Target Parameter Optimization in Drug Discovery: Strategies, Algorithms, and Real-World Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to multi-objective optimization (MOO) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Multi-Target Parameter Optimization in Drug Discovery: Strategies, Algorithms, and Real-World Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to multi-objective optimization (MOO) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of navigating conflicting objectives, such as maximizing drug efficacy while minimizing toxicity and cost. The content covers state-of-the-art methodological frameworks, including Bayesian optimization, evolutionary algorithms, and deep generative models, with specific applications in virtual screening and de novo molecular design. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges and offers a comparative analysis of algorithm performance and validation metrics. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to efficiently identify optimal compound candidates and accelerate the drug discovery pipeline.

The Core Challenge: Navigating Conflicting Objectives in Drug Discovery

Defining Multi-Objective vs. Many-Objective Optimization in a Biomedical Context

Core Definitions and Distinctions

What is the fundamental difference between Multi-Objective and Many-Objective Optimization?

The distinction is based on the number of objective functions being simultaneously optimized [1] [2]:

- Multi-Objective Optimization (MultiOO): Addresses problems involving two or three objectives.

- Many-Objective Optimization (ManyOO): Addresses problems involving four or more objectives.

This distinction is critical because the challenges and suitable algorithms change significantly as the number of objectives increases [2].

Why is this distinction important in biomedical research?

Biomedical problems often involve multiple, conflicting goals. For example, in de novo drug design, researchers aim to maximize drug potency and structural novelty while minimizing synthesis costs and unwanted side effects [1]. Framing this correctly as a many-objective problem (with four or more goals) rather than a multi-objective one guides the selection of appropriate optimization algorithms and leads to more effective and realistic solutions [2].

Key Concepts and Terminology

What is a Pareto Front? In both multi- and many-objective optimization, there is usually no single "best" solution because improving one objective often worsens another. Instead, algorithms seek a set of non-dominated solutions, known as the Pareto front [1] [2]. A solution is "non-dominated" if no other solution is better in all objectives simultaneously. The Pareto front represents the optimal trade-offs between the conflicting objectives [3].

What are the main challenges when moving from MultiOO to ManyOO? As the number of objectives increases, several computational and conceptual challenges emerge [1] [2]:

- Difficulty in Visualizing the Pareto Front: It is easy to visualize a 2- or 3-dimensional trade-off space, but this becomes impossible with four or more objectives.

- Increased Computational Cost: The number of solutions needed to approximate the high-dimensional Pareto front grows exponentially.

- Selection Pressure Loss: In many-objective problems, most solutions become non-dominated to each other, making it difficult for evolutionary algorithms to effectively select the best candidates for the next generation.

- Challenges in Decision-Making: Presenting a large set of high-dimensional trade-off solutions to a decision-maker (e.g., a scientist or clinician) for final selection becomes more complex.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Area | Common Issue | Potential Cause & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Performance | Slow convergence or poor quality results on a problem with 5+ objectives [2]. | Cause: Using an algorithm designed for 2-3 objectives (e.g., NSGA-II).Solution: Switch to a many-objective algorithm (e.g., MOEA/D, NSGA-III) or use Bayesian Optimization (MOBO) which can handle higher dimensions efficiently [4]. |

| Problem Formulation | The optimization results are clinically or biologically impractical. | Cause: Important real-world constraints (e.g., synthetic feasibility, toxicity) were not modeled [1].Solution: Reformulate the problem, moving some objectives to the constraint set to better reflect practical requirements [2]. |

| Data & Modeling | Algorithm performance is highly variable or unreliable. | Cause: The objective functions are noisy or expensive to evaluate (common with wet-lab experiments or clinical data) [3].Solution: Use a surrogate model (e.g., an Artificial Neural Network) to approximate the objective functions and reduce experimental burden [5] [4]. |

| Decision-Making | Difficulty selecting a single optimal solution from the Pareto front. | Cause: The high-dimensional trade-off space is difficult for a human to interpret [2].Solution: Employ a post-hoc decision-making tool (e.g., the BHARAT technique) to rank and identify the most suitable compromise solution based on your preferences [6]. |

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Research Reagent Solutions for In Silico and Experimental Optimization

| Item / Tool | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) | A class of population-based metaheuristics (e.g., NSGA-II, MOEA/D) that evolve a set of candidate solutions towards the Pareto front [7] [1]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A machine learning approach that builds a probabilistic surrogate model of the objective functions to guide the search for optimal parameters, ideal for expensive-to-evaluate functions [3] [4]. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Used as highly accurate surrogate models to predict the outcomes of complex experiments, drastically reducing the number of physical trials needed [5]. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) | A statistical and mathematical method used to design experiments, build models, and explore the relationships between input parameters and responses [5]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A population-based optimization technique inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking, often used in its multi-objective form (MOPSO) [5] [8]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Workflow for a Multi/Many-Objective Biomedical Optimization

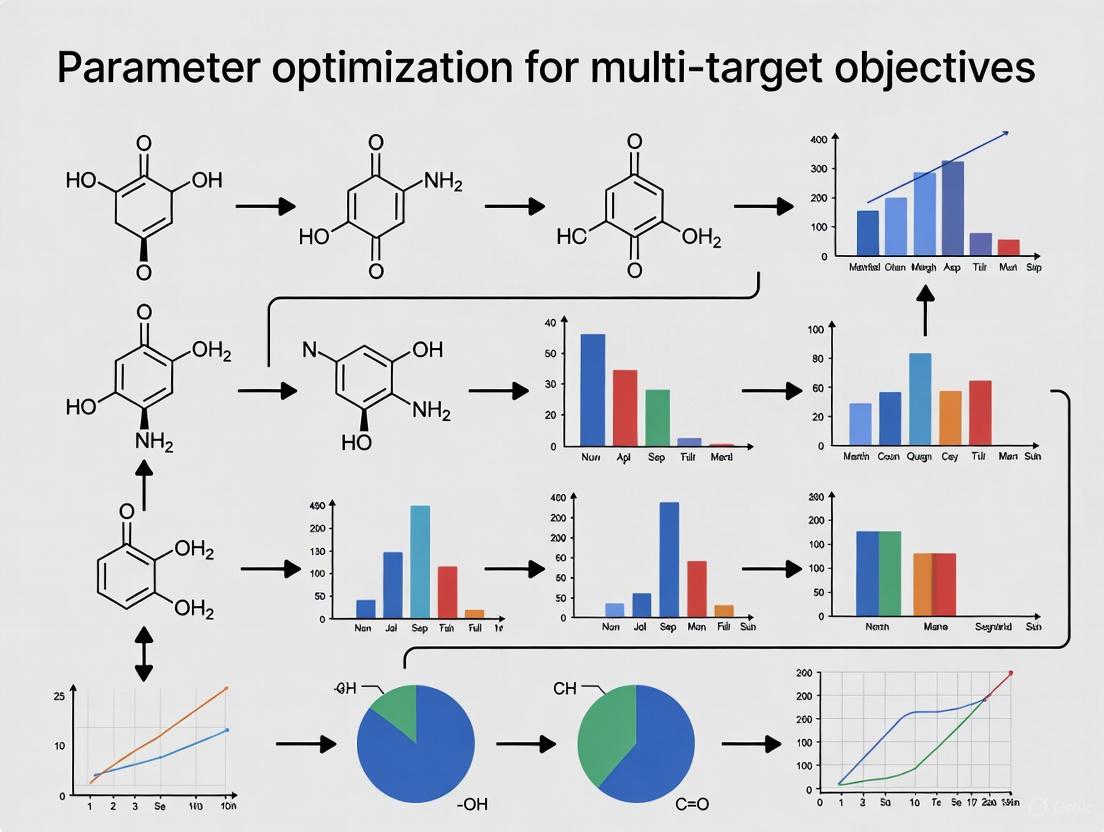

The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for tackling a biomedical optimization problem, from setup to solution.

Detailed Protocol Steps:

Problem Definition:

- Identify Objectives: Clearly list all performance measures to be optimized (e.g.,

maximize drug potency,minimize side effects,minimize synthesis cost) [2]. - Define Decision Variables: Specify the input parameters you can control (e.g.,

chemical structure,process temperature,concentration). - Establish Constraints: Define any hard limits (e.g.,

chemical stability,biocompatibility,maximum allowable cost) [1].

- Identify Objectives: Clearly list all performance measures to be optimized (e.g.,

Experimental Design & Data Collection:

- Use a design strategy like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to efficiently sample the parameter space and collect initial data [5].

- For computationally expensive or time-consuming experiments (e.g., clinical DBS programming or scaffold fabrication), this step is crucial for gathering a representative dataset [3] [8].

Model Building (Surrogate-Assisted Optimization):

- Train a surrogate model, such as an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), on the collected data. This model will act as a fast, approximate predictor of your experimental outcomes [5].

- This step dramatically reduces the number of costly physical experiments or complex simulations required during the optimization loop [4].

Algorithm Selection & Execution:

Decision-Making:

- The output is a Pareto front of non-dominated solutions. Use a decision-making technique (e.g., BHARAT) to analyze the trade-offs and select the single best compromise solution that aligns with the project's overarching goals [6].

Understanding Pareto Optimality and the Trade-Offs of the Pareto Front

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Pareto Front in multi-objective optimization? The Pareto front (also known as the Pareto frontier or Pareto curve) is the set of all Pareto optimal solutions for a multi-objective optimization problem. A solution is considered Pareto optimal if it is impossible to improve one objective without making at least one other objective worse. These solutions represent the best possible trade-offs between competing objectives [9] [10].

What does "Pareto Dominance" mean? A solution is said to "Pareto dominate" another if it is at least as good in all objectives and strictly better in at least one objective. For example, in a search for selective drug molecules, a candidate that is equally potent but more selective than another dominates it. All solutions on the Pareto front are non-dominated, meaning no other solution dominates them [11] [10].

Why can't I find a single solution that optimizes all my objectives at once? In most real-world problems, objectives are conflicting. For instance, in drug discovery, a molecule designed for extremely high potency might have poor selectivity or pharmacokinetic properties. The Pareto front formally captures this inherent conflict, showing that improvement in one goal (e.g., potency) can only be achieved by accepting a concession in another (e.g., selectivity) [12] [13].

What is the difference between a Pareto front and a "Utopian Point"? The Utopian point is a theoretical point in objective space where all objectives are at their individual optimal values. It is typically unattainable because the objectives conflict. The Pareto front, on the other hand, represents the set of all achievable optimal trade-offs. The distance between the Pareto front and the Utopian point visually illustrates the cost of these trade-offs [11].

What are some common algorithms used to find the Pareto front? Several algorithms are available, which can be broadly categorized as follows [9]:

| Algorithm Type | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Scalarization | Weighted Sum Method | Converts multi-objective problem into single-objective using weights; requires prior preference knowledge [9] [13]. |

| ε-Constraint | --- | Optimizes one objective while treating others as constraints with epsilon bounds [9]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | MOEA/D, NSGA-II | Population-based metaheuristics; can approximate complex Pareto fronts in a single run [9]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | EHI, PHI | Model-based; efficient for expensive function evaluations (e.g., virtual screening) [13]. |

How do I choose a single solution from the Pareto front? The choice requires incorporating decision-maker preferences. Common methods include:

- A Priori: Setting weights for a scalarization method before optimization.

- A Posteriori: Calculating the distance of each Pareto-optimal solution to the Utopian point and selecting the closest one [11]. The developer then reviews the trade-offs illustrated by the front and selects the solution that best aligns with project goals.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pareto Front is too sparse or poorly defined. | Optimization algorithm has not sufficiently explored the objective space. | Use a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm (MOEA) or Bayesian optimization designed to explore the entire front. Increase the population size or number of iterations [14]. |

| Algorithm converges to a single point, not a front. | Incorrect use of a single-objective optimizer or flawed scalarization. | Ensure you are using a genuine multi-objective algorithm. If using scalarization, run the optimization multiple times with different weight combinations [13]. |

| Calculated Pareto front is computationally expensive. | Objective functions (e.g., molecular docking, protein simulations) are very costly to evaluate. | Implement model-guided optimization like Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MoBО). It uses surrogate models to reduce the number of expensive evaluations needed [13]. |

| Difficulty interpreting the trade-offs in a high-dimensional front (3+ objectives). | Human intuition is best with 2D or 3D plots. | Use visualization tools like trade-off parallel coordinate plots or perform a lower-dimensional (2D) projection to analyze specific objective pairs. |

Experimental Protocol: Mapping a Pareto Frontier for a Deimmunized Biotherapeutic

The following protocol, adapted from Salvat et al. (2015), details the steps for computationally designing and experimentally validating the Pareto frontier of a therapeutic enzyme, balancing immunogenic potential with molecular function [12].

1. Objective Definition and Computational Setup

- Define Dual Objectives: Formally define the two conflicting objectives. In this case: 1) Minimize Immunogenicity: Reduce the content of predicted T-cell epitopes. 2) Maximize Function: Maintain high-level catalytic activity and stability [12].

- Select Prediction Tools: Choose computational tools to quantify each objective.

- For immunogenicity, use an epitope prediction tool like ProPred to identify peptides that bind to common MHC-II alleles [12].

- For function, use a protein stability and folding predictor (e.g., FoldX or Rosetta).

- Formulate the Optimization Problem: Implement a Pareto optimization algorithm (e.g., Pepfr, IP2) to search the sequence space for variants that are non-dominated with respect to the two objectives [12].

2. Computational Design and Pareto Front Generation

- Run Optimization Algorithm: Execute the protein design algorithm to generate a large set of candidate variants.

- Identify the Pareto Front: The algorithm will output a set of variants where no single variant is better in both immunogenicity and function than another. This set is the predicted Pareto front [12].

- Select Variants for Experimental Validation: Choose several variants from different regions of the predicted Pareto front (e.g., one偏向于 function, one偏向于 low immunogenicity, and one balanced) for synthesis and testing.

3. Experimental Validation and Analysis

- Construct Variants: Synthesize the genes for the selected Pareto-optimal variants and express the proteins.

- Measure Immunogenicity: Use in vitro T-cell activation assays or MHC-binding assays to experimentally quantify immunogenicity.

- Measure Function: Perform enzyme activity assays and stability tests (e.g., thermal shift assays) to measure functionality.

- Plot Experimental Pareto Front: Plot the experimentally measured values for each variant on a 2D graph (Immunogenicity vs. Function). The variants that form the non-dominated front constitute the experimentally validated Pareto front, revealing the functional penalty paid for deimmunization [12].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists essential computational and experimental tools used in the featured biotherapeutic deimmunization experiment and related Pareto optimization studies [12] [13].

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pepfr (Protein Engineering Pareto Frontier) | A computational algorithm for identifying all Pareto-optimal protein variants that balance multiple design objectives [12]. | Used to generate the set of enzyme variants optimally trading off immunogenicity and function. |

| ProPred | An immunoinformatic tool for predicting T-cell epitopes within a protein sequence by simulating binding to MHC-II alleles [12]. | Quantifies the "Immunogenicity" objective by identifying and scoring putative immunogenic regions in wild-type and designed enzyme variants. |

| Multi-objective Bayesian Optimization (MoBО) | A model-based optimization strategy that uses surrogate models to efficiently find the Pareto front with fewer expensive evaluations [13]. | Applied in virtual screening to identify molecules with optimal trade-offs between on-target and off-target docking scores. |

| Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide) | Structure-based computational method to predict the binding pose and affinity of a small molecule to a protein target [13]. | Used to calculate the objectives (e.g., binding affinity to on-target and off-target proteins) in multi-objective virtual screens. |

| In vitro T-cell Activation Assay | An experimental method to measure the immunogenic potential of a protein variant by its ability to activate T-cells [12]. | Provides experimental validation for the predicted "Immunogenicity" objective from computational tools like ProPred. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Optimization Performance and Premature Convergence

Problem: The optimization algorithm converges on molecules with high similarity, missing the global optimum and failing to explore the chemical space effectively. This often results in a lack of diverse candidate molecules.

Solutions:

- Implement Advanced Diversity Mechanisms: Replace standard crowding distance calculations in evolutionary algorithms (like NSGA-II) with a Tanimoto similarity-based crowding distance. This better captures structural differences between molecules, preserves population diversity, and prevents premature convergence [15].

- Utilize Dynamic Update Strategies: Incorporate a dynamic acceptance probability for population updates. This strategy favors exploration (accepting more diverse candidates) in early iterations and shifts toward exploitation (refining the best candidates) in later stages, effectively balancing the search [15].

- Leverage Pareto-Frontier Search: Use algorithms specifically designed for multi-objective optimization, such as Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search Molecular Generation (PMMG). These methods efficiently explore the Pareto front in high-dimensional objective spaces without collapsing objectives into a single score, thus avoiding the masking of deficiencies in any one property [16].

Balancing Conflicting Property Objectives

Problem: Optimizing for one property (e.g., efficacy) leads to significant deterioration in another (e.g., solubility or synthetic accessibility). Scalarization methods, which combine objectives using weighted sums, fail to find a satisfactory balance.

Solutions:

- Adopt a Pareto-Optimality Framework: Frame the problem as a Pareto optimization to identify a set of non-dominated solutions. A solution is Pareto-optimal if no objective can be improved without worsening another. This reveals the true trade-offs between properties like efficacy, toxicity, and solubility, providing researchers with multiple balanced options [16] [17].

- Incorporate Domain Expertise via Preference Learning: For high-dimensional objective spaces, integrate chemist preferences directly into the optimization loop. Frameworks like CheapVS use preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization, where experts provide pairwise comparisons on candidate molecules. This guides the algorithm toward regions of the chemical space that align with practical, nuanced trade-offs [18].

- Validate Conflict Relationships: Before optimization, quantitatively analyze the conflict relationships between your objectives. Understanding the degree to which objectives compete helps in selecting an appropriate multi-objective optimization algorithm and interpreting the final results [19].

High Computational Cost of Property Evaluation

Problem: The process is bottlenecked by the time and resources required to compute molecular properties (e.g., binding affinity, ADMET properties) for a vast number of candidate molecules.

Solutions:

- Employ Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization: Instead of exhaustively evaluating entire molecular libraries, use Bayesian optimization. This machine-learning strategy builds a surrogate model to predict properties and intelligently selects the most promising candidates for full evaluation, drastically reducing the number of expensive computations [18].

- Use Efficient Surrogate Models: Develop and use quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models built with high-performance algorithms like CatBoost. These models can rapidly predict biological activity and ADMET properties from molecular descriptors, enabling the pre-screening of candidates before more expensive simulations or experiments [19].

- Implement a Multi-Fidelity Approach: Combine fast, approximate property predictors (e.g., lightweight machine learning models) with slow, accurate ones (e.g., molecular docking or free-energy perturbation). The optimizer can use the fast models for broad exploration and reserve high-fidelity evaluations for the most promising candidates [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is multi-objective optimization superior to simple weighted sums for my drug design project? Weighted sum methods, or scalarization, require pre-defining the importance of each objective, which can be arbitrary and often suboptimal. Excessively prioritizing one property can mask critical deficiencies in others. Multi-objective optimization, particularly Pareto optimization, identifies a set of optimal trade-off solutions. This provides a comprehensive view of the available options, allowing you to see how improving binding affinity might impact toxicity, and to make a more informed final choice [16] [17].

Q2: My generated molecules have good predicted efficacy but poor synthetic accessibility. How can I fix this? This is a common conflict. To address it, explicitly include synthetic accessibility as an optimization objective. Use a quantitative score like the Synthetic Accessibility Score (SAScore) as one of the goals in your multi-objective setup. Algorithms like PMMG and MoGA-TA have been successfully used to optimize efficacy alongside SAScore, ensuring the proposed molecules are not only active but also practical to synthesize [16] [15].

Q3: What are the key metrics for evaluating the success of a multi-objective molecular optimization? The performance should be evaluated from multiple perspectives:

- Hypervolume (HV): Measures the volume of objective space covered by the computed Pareto front relative to a reference point. A higher HV indicates a better and more diverse set of solutions [16] [15].

- Success Rate (SR): The percentage of generated molecules that simultaneously meet all desired property thresholds [16].

- Diversity (Div): Assesses the structural and property diversity of the generated molecule set, ensuring a broad exploration of chemical space [16].

Q4: How can I incorporate expert chemist knowledge into an automated optimization process? Preferential Bayesian optimization provides a formal framework for this. Platforms like CheapVS allow chemists to interact with the algorithm by comparing pairs of molecules and indicating their preference. The system learns a latent utility function from these comparisons and uses it to guide the search toward chemist-preferred regions of the objective space, effectively capturing hard-to-quantify chemical intuition [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Benchmark Performance of Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms

The following table summarizes the performance of various algorithms on benchmark molecular optimization tasks, demonstrating the effectiveness of advanced multi-objective methods.

Table 1: Algorithm Performance on Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization Tasks [16]

| Method | Hypervolume (HV) | Success Rate (SR) | Diversity (Div) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMMG | 0.569 ± 0.054 | 51.65% ± 0.78% | 0.930 ± 0.005 |

| SMILES_GA | 0.184 ± 0.021 | 3.02% ± 0.12% | 0.891 ± 0.007 |

| SMILES-LSTM | 0.217 ± 0.031 | 5.44% ± 0.23% | 0.905 ± 0.004 |

| REINVENT | 0.235 ± 0.028 | 8.91% ± 0.35% | 0.912 ± 0.006 |

| MARS | 0.433 ± 0.047 | 20.76% ± 0.61% | 0.921 ± 0.003 |

Detailed Protocol: Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search Molecular Generation (PMMG)

This protocol is designed for generating novel molecules optimized for multiple conflicting objectives [16].

1. Principle: The PMMG algorithm integrates a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) as a molecular generator with a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) guided by the Pareto principle. It explores the chemical space by building SMILES strings token-by-token to discover molecules on the Pareto front.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Initialization. Train an RNN model on a large corpus of SMILES strings to learn the underlying grammatical structure. Initialize the MCTS.

- Step 2: Selection. Start from the root of the search tree (an empty SMILES string) and traverse down by selecting child nodes with the highest Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) score, which balances explored value and uncertainty.

- Step 3: Expansion. When a leaf node (a partial SMILES string) is reached, use the RNN to predict the probability distribution of the next possible tokens. Add one or more of these tokens as new child nodes to the tree.

- Step 4: Simulation. From a new child node, continue generating a complete SMILES string by sampling tokens from the RNN's output distribution until the termination symbol is reached.

- Step 5: Evaluation. Convert the completed SMILES string into a molecule and evaluate it against all defined objectives (e.g., docking score, QED, SAScore, etc.). Normalize the scores if they are on different scales.

- Step 6: Backpropagation. Propagate the multi-objective evaluation result back up the tree. Update the node statistics. The MCTS uses Pareto dominance to determine whether a new solution is an improvement.

- Step 7: Iteration. Repeat Steps 2-6 for a predefined number of iterations or until a performance criterion is met. The final output is a set of non-dominated molecules approximating the Pareto front.

3. Key Objectives for a Dual-Target (EGFR/HER2) Case Study: [16]

- Efficacy: Docking score for EGFR (Maximize)

- Efficacy: Docking score for HER2 (Maximize)

- Drug-likeness: QED score (Maximize)

- Solubility: (Maximize)

- Toxicity: (Minimize)

- Metabolic Stability: (Maximize)

- Synthetic Accessibility: SAScore (Minimize)

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

PMMG Algorithm Workflow

This diagram illustrates the core iterative process of the Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search Molecular Generation algorithm.

Multi-Objective Conflict Relationship

This diagram visualizes the core conflicts between the four key objectives in drug discovery that must be balanced during optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprints (ECFP, FCFP), and properties like logP and TPSA. | Used in benchmark tasks for featurization and property calculation [15]. |

| GuacaMol | A benchmarking platform for assessing generative models and optimization algorithms on a series of tasks based on public ChEMBL data. | Provides standardized benchmark tasks (e.g., Fexofenadine, Osimertinib) for fair algorithm comparison [15]. |

| Pareto-Based MCTS | A search algorithm that combines Monte Carlo Tree Search with Pareto dominance rules to navigate high-dimensional objective spaces. | Core component of the PMMG method for multi-objective de novo molecular design [16]. |

| Tanimoto Similarity | A coefficient measuring the similarity between molecules based on their fingerprint bits (e.g., ECFP4). Used in crowding distance and as an objective. | Maintains structural diversity in MoGA-TA; used as an objective to maintain similarity to a lead compound [15]. |

| SAScore | A quantitative estimate of synthetic accessibility, typically minimized during optimization. | A key objective to ensure generated molecules are practical to synthesize [16]. |

| CatBoost Algorithm | A high-performance gradient boosting algorithm effective with categorical data, used to build accurate QSAR models. | Used for relationship mapping between molecular descriptors and biological/ADMET properties [19]. |

In parameter optimization research, a fundamental shift is occurring from single-objective to multi-objective frameworks. Traditional single-objective optimization methods, which seek to find the optimal solution for a single property of interest, are increasingly proving inadequate for complex real-world problems where multiple, competing objectives must be balanced simultaneously [20]. This transition represents more than a simple linear increase in the number of objectives—it demands dramatically different methods, interpretations, and solution approaches [20].

In fields from drug discovery to engineering design, researchers face the challenge of optimizing systems where improving one metric often comes at the expense of another. For example, in pharmaceutical development, medicinal chemists must carefully balance multiple properties including potency, absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and safety characteristics [21]. Similarly, in manufacturing processes, engineers might need to maximize product strength while minimizing fabrication costs—objectives that typically conflict [20]. This article explores why traditional single-objective optimization falls short for these complex problems and provides practical guidance for implementing multi-objective approaches.

Core Concepts: Understanding the Fundamental Differences

What is Single-Objective Optimization?

Single-objective optimization aims to maximize or minimize a singular property of interest. It's the go-to method when you have both a clear goal and a single metric of success [20]. In this framework:

- A probabilistic model is trained to predict the property of interest as a function of one or more inputs

- At each optimization iteration, the model predicts optimal input parameters

- These parameters are evaluated computationally or experimentally

- Results are integrated back into the model to refine predictions

- The process continues until the best set of inputs is identified [20]

Single-objective optimization typically utilizes gradient descent approaches that use derivatives and iterative algorithms to hone in on the optimum value of the objective function [22]. This approach relies on constraints to set conditions that must be met for a solution to be considered feasible.

What is Multi-Objective Optimization?

Multi-objective optimization (also known as Pareto optimization, vector optimization, multicriteria optimization, or multiattribute optimization) involves mathematical optimization problems with more than one objective function to be optimized simultaneously [10]. Unlike single-objective problems, multi-objective optimization problems rarely have a single solution that optimizes all objectives simultaneously, as the objective functions are typically conflicting [10].

The key conceptual difference is that multi-objective optimization does not generate a single "best" solution, but rather an array of solutions collectively known as the Pareto front [22]. These solutions represent optimal trade-offs between the competing objectives.

Table: Key Terminology in Multi-Objective Optimization

| Term | Definition | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pareto Optimal | A solution that cannot be improved in any objective without degrading at least one other objective [10] | Defines the set of optimal trade-off solutions |

| Pareto Front | The set of all Pareto optimal solutions in objective space [20] | Visualizes the complete trade-off landscape between objectives |

| Dominance | Solution A dominates B if A is better in at least one objective and not worse in all others [23] | Enables comparison and ranking of solutions |

| Hypervolume | The volume of objective space dominated by Pareto solutions relative to a reference point [20] | Quantifies the quality and diversity of a Pareto front approximation |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Multi-Objective Optimization Challenges

FAQ: Implementation Challenges

Q: How do I determine if my problem requires single or multi-objective optimization?

A multi-objective approach is necessary when you face competing goals that cannot be reduced to a single metric without oversimplifying the problem [20]. Key indicators include:

- Having multiple success criteria that conflict with each other (e.g., maximizing performance while minimizing cost)

- Needing to understand trade-offs between different objectives before making decisions

- Working in domains where optimal decisions require balancing multiple factors (common in engineering, economics, logistics, and drug discovery) [10]

If you find yourself trying to combine different metrics into a single objective through subjective weighting, your problem is likely inherently multi-objective.

Q: My multi-objective optimization isn't finding diverse solutions along the Pareto front. What could be wrong?

This common issue typically stems from several potential causes:

- Insufficient exploration: The optimization may be over-emphasizing exploitation of known good regions. Consider increasing the exploration parameter in your acquisition function [24]

- Poor parameter tuning: Evolutionary algorithms like NSGA-II require proper tuning of crossover and mutation rates to maintain diversity

- Misguided priors: If using prior knowledge, ensure it's not overly constraining the search space. Algorithms like PriMO include mechanisms to recover from misleading priors [24]

- Inadequate population size: For evolutionary methods, ensure your population size is sufficient to approximate the entire Pareto front

Q: How can I incorporate constraints in multi-objective optimization?

Constrained multi-objective optimization problems (CMOPs) present additional challenges as they must balance convergence, diversity, and feasibility [25]. Several effective approaches exist:

- Penalty methods: Convert constraints into penalty terms that worsen objective values proportionally to constraint violation [23]

- Feasibility-first sorting: Prioritize feasible solutions during selection operations

- Specialized algorithms: Use constrained multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (CMOEAs) specifically designed for these problems [25]

- Repair mechanisms: Transform infeasible solutions into feasible ones through repair operations

Recent advances in machine learning have also enabled new constraint-handling techniques that learn feasible regions from data [25].

Q: What's the computational cost difference between single and multi-objective approaches?

Multi-objective optimization typically has higher computational requirements due to:

- The need to approximate an entire front of solutions rather than a single point

- Additional operations like non-dominated sorting and diversity maintenance

- Potentially longer convergence times to fully explore trade-offs

However, strategies like using cheap approximations of objective functions can significantly reduce this burden [24]. For example, the PriMO algorithm leverages low-fidelity proxies of expensive objectives to speed up optimization while maintaining performance [24].

FAQ: Method Selection and Implementation

Q: When should I use blended vs. hierarchical approaches for multiple objectives?

The choice depends on your problem structure and decision-making process:

Blended objectives (weighted sum) are appropriate when you can quantitatively express the relative importance of different objectives beforehand [26]. This approach creates a single objective through linear combination of individual objectives with specified weights.

Hierarchical (lexicographic) approaches work best when objectives have clear priority rankings [26]. In this method, you optimize objectives in priority order, with each subsequent optimization considering only solutions that don't significantly degrade higher-priority objectives.

Pareto-based methods are ideal when you want to explore trade-offs without pre-specifying preferences. These methods identify the Pareto front for posteriori decision making.

Many modern optimization frameworks, including commercial solvers like Gurobi, support hybrid approaches that combine both blended and hierarchical elements [26].

Q: How do I effectively incorporate expert knowledge into multi-objective optimization?

Recent advances like the PriMO (Prior Informed Multi-objective Optimizer) algorithm provide structured ways to integrate expert beliefs over multiple objectives [24]. Key considerations include:

- Representing prior knowledge as probability distributions over the location of optima for each objective

- Balancing exploration and exploitation to benefit from good priors while recovering from misleading ones

- Using adaptive weighting of priors that decreases as optimization progresses to avoid over-reliance on potentially incorrect beliefs

In drug discovery applications, multi-parameter optimization (MPO) tools have become indispensable for incorporating medicinal chemists' knowledge while eliminating cognitive biases that can occur when dealing with large volumes of complex data [21].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Multi-Objective Optimization

Standard Protocol for Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization

Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful framework for multi-objective problems, particularly when objective evaluations are expensive [24]. The following protocol outlines a standard approach:

Problem Formulation

- Define the vector-valued objective function f(λ) = (f₁(λ), f₂(λ), ..., fₙ(λ)) where λ represents decision variables

- Specify the feasible region for λ

- Identify cheap approximations (if available) for expensive objectives [24]

Prior Specification (Optional but Recommended)

- Elicit expert beliefs about promising regions for each objective: πfi(λ) = P(fi(λ) = min{λ'} fi(λ'))

- Form compound prior Πf(λ) = {πfi(λ)} for i=1 to n [24]

Initial Design

- Generate initial samples using space-filling designs (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling)

- Evaluate initial points using available cheap approximations where possible

Model Fitting

- Train probabilistic surrogate models (typically Gaussian Processes) for each objective

- For constrained problems, also model constraint functions

Acquisition Optimization

- Select next evaluation point by optimizing acquisition function (e.g., Expected Hypervolume Improvement)

- Incorporate prior beliefs through weighted acquisition: α(λ) × π_fi(λ)^γ where γ controls prior influence [24]

- Balance exploration and exploitation through appropriate trade-off parameters

Evaluation and Update

- Evaluate selected point on true objectives

- Update surrogate models with new data

- Update Pareto front approximation

Termination Check

- Stop when hypervolume improvement falls below threshold or budget exhausted

- Return approximated Pareto front

Case Study Protocol: RFSSW Parameter Optimization

A 2025 study on Refill Friction Stir Spot Welding (RFSSW) demonstrates an integrated approach combining statistical methods, machine learning, and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms [27]. The experimental workflow can be adapted to various domains:

Experimental workflow for multi-objective optimization

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Data Generation

- Implement full-factorial design (3³ DOE) varying three critical process parameters: rotational speed, plunge depth, and welding time [27]

- Generate training and validation data measuring outcomes of interest (e.g., joint load capacity under different shear-testing conditions)

- Replicate center points to estimate experimental error

Phase 2: Statistical Analysis and Model Building

- Perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to identify significant factors and interaction effects [27]

- Train multiple machine learning models (MLP, RBF, GPR, k-NN, SVR, XGBoost) to predict outcomes from parameters

- Evaluate models via cross-validation, selecting best performer based on R², MAE, and RMSE

- Interpret models using feature importance and SHAP analysis to validate mechanistic understanding

Phase 3: Multi-Objective Optimization

- Implement NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) to optimize multiple objectives simultaneously [27]

- Define objective functions based on trained ML models

- Set appropriate genetic algorithm parameters (population size, crossover, and mutation rates)

- Run optimization until Pareto front convergence

Phase 4: Decision Making

- Analyze resulting Pareto front to understand trade-offs between objectives

- Apply maximin strategy or other decision-making approaches to select final compromise solution [27]

- Validate selected solution through physical experimentation

Computational Tools and Algorithms

Table: Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Type | Best For | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSGA-II [23] [27] | Evolutionary | Problems requiring well-distributed Pareto fronts | Fast non-dominated sorting, crowding distance for diversity |

| MOEA/D [23] | Evolutionary | High-dimensional problems | Decomposes multi-objective problem into single-objective subproblems |

| SPEA2 [23] | Evolutionary | Complex Pareto fronts | Uses fine-grained fitness assignment with density estimation |

| PriMO [24] | Bayesian Optimization | Expensive evaluations with expert knowledge | Incorporates multi-objective priors, uses cheap approximations |

| MOPSO [23] | Swarm Intelligence | Continuous optimization | Particle swarm approach with external archive |

| SMS-EMOA [23] | Evolutionary | Precision-critical applications | Uses hypervolume contribution for selection |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Equivalents

In computational optimization, "reagents" equate to the tools and methodologies that enable effective multi-objective problem-solving:

Surrogate Models: Gaussian Process Regression, Neural Networks, or XGBoost [27] act as replacements for expensive experimental evaluations, allowing extensive virtual testing before physical validation.

Hypervolume Calculator: This critical metric measures the quality of Pareto front approximations by calculating the volume of objective space dominated by solutions [20], serving as the multi-objective equivalent of convergence tracking in single-objective optimization.

Scalarization Functions: Linear weighted sums, achievement scalarizing functions, or Chebyshev approaches [23] transform multi-objective problems into single-objective subproblems for decomposition-based methods.

Constraint Handling Techniques: Penalty functions, feasibility rules, or stochastic ranking [25] manage feasibility constraints while maintaining population diversity.

Visualization Tools: Parallel coordinate plots, scatterplot matrices, and 3D Pareto front visualizations enable researchers to understand complex trade-offs in high-dimensional objective spaces.

The transition from single-objective to multi-objective optimization represents more than a technical shift—it requires a fundamental change in how we conceptualize optimality. Where single-objective thinking seeks a singular "best" solution, multi-objective optimization acknowledges the reality of trade-offs and empowers researchers to make informed decisions based on a comprehensive understanding of these compromises.

For researchers and practitioners moving from traditional optimization approaches, the key is to recognize that multi-objective problems aren't just more complex versions of single-objective problems—they're fundamentally different classes of problems requiring different tools, methodologies, and mindsets. By leveraging the troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and toolkit resources provided here, scientists across domains can more effectively navigate this transition and harness the full power of multi-objective optimization in their research.

The Role of Expert Preference and Chemical Intuition in Guiding Optimization

Troubleshooting Guide: Multi-Objective Optimization in Drug Discovery

No Meaningful Pareto Front Generated After Extensive Optimization

Problem: The optimization process fails to produce a diverse set of viable candidate compounds trading off different objectives effectively.

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Misguided Expert Priors | Check if sampled configurations cluster narrowly in hyperparameter space. | Implement PriMO algorithm to balance prior use with exploration; reduce prior weighting over iterations [24]. |

| Poor Scalarization Weights | Analyze if Pareto front favors one objective excessively. | Use random linear scalarization with uniformly sampled weights for each BO iteration [24]. |

| Insufficient Budget for MOO | Monitor hypervolume progression; if still increasing significantly, more budget needed. | Leverage cheap approximations (low-fidelity proxies) for initial screening; use multi-fidelity optimization [24]. |

Learned Molecular Scoring Function Contradicts Expert Intuition

Problem: The AI model trained on chemist preferences produces rankings that experts find unreasonable or cannot rationalize.

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Inter-Rater Agreement | Compute Fleiss' κ from evaluation data; values <0.4 indicate weak consensus [28]. | Collect more preference data with active learning; refine preference question design [28]. |

| Model Capturing Spurious Correlations | Perform SHAP analysis or feature importance scoring on learned model [28]. | Use fragment analysis to rationalize preferences; validate against known structural alerts [28]. |

| Insufficient Training Data | Plot learning curve (AUROC vs. training pairs); AUROC <0.7 indicates need for more data [28]. | Extend data collection; use active learning to select informative pairs [28]. |

Multi-Objective Hyperparameter Optimization Fails to Utilize Expert Knowledge

Problem: Existing HPO algorithms cannot incorporate medicinal chemists' prior beliefs about promising molecular regions.

| Possible Cause | Verification Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Lacks Prior Integration | Check if HPO method supports user beliefs over multiple objectives. | Implement PriMO (Prior Informed Multi-objective Optimizer), the first HPO algorithm for multi-objective expert priors [24]. |

| Poor Recovery from Misleading Priors | Analyze if performance degrades with imperfect priors. | Use PriMO's exploration parameter and prior weighting decay (γ=exp(-n²BO/n𝑑)) to recover from bad priors [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can we quantitatively capture medicinal chemistry intuition?

Medicinal chemistry intuition can be captured through preference learning techniques where chemists provide pairwise comparisons between compounds [28]. This approach avoids psychological biases like anchoring that affect Likert-scale ratings. The learned implicit scoring functions capture aspects of chemistry not covered by traditional chemoinformatics metrics, with models achieving >0.74 AUROC in predicting chemist preferences [28].

What are the key desiderata for modern multi-objective HPO in drug discovery?

Modern HPO algorithms for drug discovery should fulfill four key criteria:

- Utilize cheap approximations: Leverage low-fidelity proxies of objective functions to speed up optimization [24]

- Integrate multi-objective expert priors: Incorporate prior beliefs about optimal hyperparameter regions for multiple objectives [24]

- Strong anytime performance: Find good candidates quickly under limited budget [24]

- Strong final performance: Yield optimal solutions as computational budget increases [24]

Studies show moderate inter-rater agreement (Fleiss' κ = 0.32-0.4) between different chemists, but fair intra-rater consistency (Cohen's κ = 0.59-0.6) within individual chemists [28]. This suggests that while personal experiences drive decisions in close cases, there are learnable patterns in the aggregate preferences of medicinal chemists.

How does PriMO integrate expert priors for multiple objectives?

PriMO integrates multi-objective expert priors through a factorized prior approach [24]. For each objective ( fi ) in the vector-valued function ( f ), prior beliefs ( π{fi}(λ) ) represent a probability distribution over the location of the optimum of ( fi ). The algorithm weights its acquisition function with a selected prior, with the weight decaying as optimization progresses to prevent overdependence on potentially misleading priors [24].

Preference Learning Performance Metrics

| Training Pairs | Cross-Val AUROC | Preliminary Set AUROC | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 0.60 | 0.75 | Performance steadily improves with more data [28] |

| 5000 | 0.74+ | ~0.75 | No performance plateau observed; more data beneficial [28] |

Multi-Objective HPO Algorithm Comparison

| Algorithm | Utilize Cheap Approx. | Multi-objective Expert Priors | Strong Anytime Performance | Strong Final Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Search (RS) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Evolutionary Alg. (EA) | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | (✓) |

| MOMF | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | (✓) |

| MO-BO | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ |

| PriMO | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Correlation of Learned Scores with Traditional Metrics

| Molecular Descriptor | Pearson Correlation (r) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| QED (Drug-likeness) | ~0.4 (highest) | Learned scores provide orthogonal perspective [28] |

| Fingerprint Density | ~0.4 | Slight preference for feature-rich molecules [28] |

| SA Score | Small positive | Slight preference for synthetically simpler compounds [28] |

| SMR VSA3 | Slight negative | Possible liking toward neutral nitrogen atoms [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Collecting Medicinal Chemistry Preference Data

Purpose: To gather pairwise comparison data from medicinal chemists for training preference learning models [28].

Materials:

- Molecular pair presentation platform (web-based interface)

- 35+ medicinal chemists (wet-lab, computational, and analytical)

- Diverse compound library representing lead optimization chemical space

Procedure:

- Present chemists with pairs of compounds in randomized order

- For each pair, ask: "Which compound would you prefer to synthesize and test in the next round of optimization?"

- Collect responses over several months with active learning guidance

- Include redundant pairs to measure intra-rater consistency (target Cohen's κ > 0.59)

- Compute inter-rater agreement using Fleiss' κ (expected range: 0.32-0.4)

Quality Control:

- Monitor for positional bias in presentation

- Include consistency checks with previously seen pairs

- Achieve >5000 annotated pairs for robust model training [28]

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Hyperparameter Optimization with PriMO

Purpose: To optimize neural network hyperparameters for multiple objectives while incorporating expert priors [24].

Materials:

- Deep learning training pipeline

- Validation datasets for multiple objectives (e.g., activity, ADMET, synthesizability)

- Computational budget for Bayesian optimization

Procedure:

- Define Multi-Objective Space:

- Identify hyperparameters to optimize (e.g., layers, learning rate, dropout)

- Define multiple objectives (e.g., validation loss, training time, model size)

Specify Expert Priors:

- For each objective ( fi ), define prior belief ( π{f_i}(λ) ) over optimal hyperparameters

- Form compound prior ( Πf(λ) = {π{fi}(λ)}{i=1}^n )

Initialize PriMO:

- Set prior weighting exponent ( γ = \exp(-n{\text{BO}}^2 / nd) )

- Configure exploration parameter for recovery from misleading priors

Run Optimization Loop:

- At each iteration:

- Select random prior from ( Πf(λ) )

- Compute acquisition function weighted by prior^γ

- Convert multi-objective to scalar using random linear weights ( wi \sim \mathcal{U} )

- Evaluate promising configurations using cheap approximations when available

- Continue until computational budget exhausted or convergence achieved

- At each iteration:

Validation:

- Compare dominated hypervolume against baseline optimizers

- Verify robustness to misleading priors by testing with perturbed expert beliefs

- Achieve up to 10x speedups over existing algorithms [24]

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Application in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| MolSkill Package | Production-ready preference learning models and anonymized response data [28] | Deploy learned scoring functions for compound prioritization |

| PriMO Algorithm | Bayesian optimization with multi-objective expert priors [24] | Hyperparameter tuning for predictive models in drug discovery |

| Active Learning Framework | Selects informative molecular pairs for chemist evaluation [28] | Efficiently collect preference data by reducing redundant comparisons |

| QED Calculator | Computes quantitative estimate of drug-likeness [28] | Baseline metric for comparing learned preference scores |

| SHAP Analysis Tool | Interprets machine learning model predictions [28] | Rationalizes learned chemical preferences via feature importance |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Preference Learning for Molecular Optimization

Diagram 2: PriMO Multi-Objective HPO with Expert Priors

Frameworks and Algorithms: From Bayesian Optimization to Evolutionary Strategies

The CheapVS (CHEmist-guided Active Preferential Virtual Screening) framework is a novel, human-centered approach designed to overcome the major bottleneck of post-processing hit selection in virtual screening (VS) for drug discovery. It integrates preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization with an efficient diffusion docking model, allowing chemists to guide the ligand selection process by providing pairwise preference feedback on the trade-offs between multiple critical drug properties [29] [18].

This framework addresses the challenge where traditional VS, despite advancements in automation, remains resource-intensive. It requires medicinal chemists to manually select promising molecules from vast candidate pools based on their chemical intuition, forcing them to repeatedly balance complex trade-offs among properties like binding affinity, solubility, and toxicity [18]. By capturing this human chemical intuition computationally, CheapVS significantly improves the efficiency and reliability of hit identification.

Key Components and Workflow

The CheapVS framework combines several advanced components into a cohesive workflow. The diagram below illustrates how these components interact to streamline the virtual screening process.

At its core, the framework operates through this sequence [18]:

- Initialization: The process begins with a target protein and a large library of chemical candidates.

- Property Prediction: A lightweight diffusion docking model measures key ligand properties, with a primary focus on binding affinity.

- Preference Elicitation: A medicinal chemist provides pairwise preference feedback, comparing candidates based on multiple, potentially competing objectives.

- Optimization: The preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm uses this feedback to learn a latent utility function that reflects the expert's trade-offs.

- Candidate Selection: The algorithm then intelligently selects the most promising candidates for the next round of evaluation, drastically reducing the number of compounds that need to be fully screened.

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Optimization Performance or Slow Convergence

Problem: The Bayesian optimization process is not efficiently identifying high-quality candidates, converges to sub-optimal solutions, or progresses too slowly.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Prior Width [30] | Check if the model is over-smoothing predictions or failing to capture trends. | Adjust the Gaussian Process (GP) kernel amplitude (σ) and lengthscale (ℓ) to better reflect the actual smoothness and variance of the objective function. |

| Inadequate Acquisition Function Maximization [30] | Review optimization logs; the proposed points may cluster in a small area. | Increase the number of restarts (n_restarts) when maximizing the acquisition function to more thoroughly explore the search space and avoid local optima. |

| High-Dimensional Search Space [31] | Algorithm runtime scales exponentially; performance plateaus. | Implement a local optimization method like TuRBO (Trust Region Bayesian Optimization), which adaptively restricts the search to a promising local region [32]. |

| Insufficient Expert Feedback | The utility function fails to reflect chemist intuition. | Ensure the chemist provides consistent and sufficiently diverse pairwise comparisons, especially in early rounds, to guide the model effectively. |

Handling Multi-Objective Trade-offs and Constraints

Problem: The algorithm suggests candidates that are excellent in one property (e.g., binding affinity) but poor in others critical for a viable drug (e.g., solubility or toxicity).

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poorly Defined Preferences | The suggested Pareto-optimal solutions are chemically impractical. | Refine the preference feedback mechanism. Use pairwise comparisons that directly present trade-offs, allowing the chemist to define what balance is acceptable [18]. |

| Black-Box Nature of BO [31] | Inability to understand why a candidate was chosen or which variables drive performance. | Leverage model interpretability tools. If using an alternative like random forests, use feature importance or Shapley values to explain predictions and build trust [31]. |

| Ignoring Hard Constraints | Candidates violate fundamental chemical rules or stability criteria. | Augment the acquisition function to model the probability of constraint satisfaction and multiply it into the acquisition function, thereby penalizing invalid suggestions [31]. |

Computational Performance and Scalability Issues

Problem: Each optimization cycle takes an impractically long time, making the framework unsuitable for large libraries or tight research schedules.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Surrogate Model [31] | GP fitting time becomes prohibitive as the number of evaluations grows. | For high-dimensional problems, consider switching to a more scalable surrogate model like Random Forests with integrated uncertainty estimates [31]. |

| Inefficient Docking Model [18] | The diffusion model for binding affinity prediction is a computational bottleneck. | Use the lightweight diffusion docking model advocated in CheapVS, which uses data augmentation to maintain high performance while significantly improving efficiency [18]. |

| Large Library Size | The algorithm struggles to explore a library of 100K+ compounds. | Adopt the active learning strategy of CheapVS, which screens only a small fraction (e.g., 6%) of the library by focusing computational resources on the most promising candidates [29] [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Framework and Methodology

Q: What makes CheapVS different from traditional virtual screening? A: Traditional virtual screening relies on exhaustively docking entire large libraries, which is computationally expensive, followed by a manual selection by chemists. CheapVS revolutionizes this by combining an active learning approach with expert guidance. It uses multi-objective Bayesian optimization to sequentially select small batches of compounds for evaluation, incorporating chemist preferences via pairwise feedback to balance multiple drug properties simultaneously. This allows it to identify hits by screening only a small fraction (~6%) of the library, saving immense computational resources [29] [18].

Q: On what scale has CheapVS been validated? A: The framework was validated on a substantial library of 100,000 chemical candidates targeting two proteins: EGFR (a cancer-associated protein) and DRD2. This demonstrates its applicability to realistic drug discovery scenarios [18] [33].

Q: What are the key properties that CheapVS can optimize? A: The framework is designed to handle multiple objectives that are critical for drug success. While binding affinity is a primary property, the multi-objective and preference-based approach allows for the incorporation of other key properties such as solubility, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties [18].

Implementation and Practical Use

Q: How is the chemist's "chemical intuition" actually captured by the algorithm? A: Chemical intuition is captured through pairwise preference feedback. The chemist is presented with pairs of candidate molecules and their property profiles. The chemist then indicates which candidate they prefer, based on their expert assessment of the trade-offs. The Bayesian optimization algorithm uses this feedback to learn a latent utility function that mathematically represents the chemist's preferences, effectively embedding their intuition into the optimization process [18] [33].

Q: What is the role of the diffusion model in CheapVS? A: The diffusion model serves as an efficient and accurate docking model for measuring binding affinity. It predicts how strongly a small molecule (ligand) binds to the target protein, which is a fundamental property in virtual screening. The CheapVS framework specifically uses a lightweight diffusion model to ensure this critical step remains computationally feasible for large-scale screening [29] [18].

Q: My research requires covering multiple diverse targets (e.g., a spectrum of pathogens). Can Bayesian optimization handle this? A: Yes, this is known as the coverage optimization problem. Methods like MOCOBO (Multi-Objective Coverage Bayesian Optimization) extend Bayesian optimization to find a small set of K solutions (e.g., drug candidates) that collectively "cover" T objectives (e.g., effectiveness against T different pathogens). The goal is that for each objective, at least one solution in the set performs well, which is ideal for designing broad-spectrum therapies or cocktail treatments [32].

Performance and Limitations

Q: What is the real-world performance evidence for CheapVS? A: In published experiments, CheapVS demonstrated exceptional performance. On the EGFR-targeted library, it was able to recover 16 out of 37 known drugs while scanning only 6% of the 100,000-compound library. Similarly, for DRD2, it recovered 37 out of 58 known drugs. This shows its high potential to identify true hits with minimal computational budget [18] [33].

Q: What are the main limitations of using Bayesian optimization in drug discovery? A: While powerful, Bayesian optimization has limitations:

- Scalability: It can become computationally intensive in very high-dimensional search spaces (e.g., with dozens of variables) [31] [34].

- Interpretability: It can sometimes act as a "black box," making it difficult to understand why a specific candidate was chosen, though methods exist to mitigate this [31].

- Initial Samples: It typically requires a dozen or so initial samples to build a useful surrogate model [34].

- Complex Constraints: Handling multiple, hard real-world constraints (e.g., synthetic accessibility) can be challenging and may require modifications to the standard framework [31].

Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Key Experimental Protocol: Validating CheapVS on EGFR

The following protocol details the key experiment demonstrating the efficacy of the CheapVS framework, as described in the literature [18].

Objective: To evaluate the performance of CheapVS in identifying known drugs from a large library of chemical candidates targeting the EGFR protein, while using only a small fraction of the computational budget of traditional screening.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Library Curation: A library of 100,000 chemical candidates known to target the EGFR protein was assembled.

- Initialization: A small, random subset of the library was selected as the initial batch for evaluation.

- Property Evaluation: The lightweight diffusion docking model was used to predict the binding affinity and other relevant properties for the selected candidates.

- Preference Learning: A medicinal chemist provided pairwise feedback on the evaluated candidates, indicating preferences based on multi-property trade-offs.

- Bayesian Update: The preferential multi-objective Bayesian optimization algorithm updated its internal surrogate model and the latent utility function based on the new property data and preference feedback.

- Candidate Proposal: The acquisition function (e.g., one based on Expected Improvement) was maximized to propose the next most promising batch of candidates to evaluate.

- Iteration: Steps 3-6 were repeated for a fixed number of iterations or until a computational budget (e.g., 6% of the total library screened) was exhausted.

- Output: The final list of top-ranked hit candidates was output. Performance was measured by the number of known drugs recovered from the library within the screened subset.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists the key computational "reagents" and their functions essential for implementing a framework like CheapVS.

| Research Reagent | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Compound Library | A large collection (e.g., 100,000 candidates) of small molecules or compounds, such as those targeting EGFR or DRD2. This is the search space for the optimization [18]. |

| Target Protein Structure | The 3D structure of the protein of interest (e.g., EGFR). Serves as the input for the docking model to predict binding interactions [18]. |

| Diffusion Docking Model | A machine learning model (e.g., a lightweight diffusion model) used to predict the binding affinity and pose of a ligand to the target protein. It is the primary property evaluator [29] [18]. |

| Preferential MOBO Algorithm | The core optimization engine that sequentially selects compounds, incorporates pairwise preferences, and balances the trade-offs between multiple objectives to maximize a latent utility function [18] [33]. |

| GP Surrogate Model | A Gaussian Process model that acts as a probabilistic surrogate for the expensive objective functions, predicting the mean and uncertainty of property values for unscreened compounds [30] [35]. |

| Acquisition Function | A function (e.g., Expected Improvement) that guides the search by quantifying the potential utility of evaluating a new candidate, balancing exploration and exploitation [30] [35]. |

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of the CheapVS framework as reported in its validation experiments, providing a clear benchmark for expected outcomes [18].

| Metric | Performance on EGFR | Performance on DRD2 |

|---|---|---|

| Library Size | 100,000 compounds | 100,000 compounds |

| Screening Budget | ~6,000 compounds (6%) | ~6,000 compounds (6%) |

| Known Drugs in Library | 37 known drugs | 58 known drugs |

| Drugs Recovered by CheapVS | 16 drugs | 37 drugs |

| Key Innovation | Incorporation of chemist preference via pairwise feedback | Multi-objective optimization beyond just binding affinity |

Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (MOPs) require simultaneously optimizing several, often competing, objective functions [2]. Unlike single-objective optimization, there is no single optimal solution but a set of trade-off solutions known as the Pareto-optimal set [2]. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are particularly well-suited for solving MOPs because their population-based nature allows them to approximate the entire Pareto front in a single run [2].

This technical support center focuses on three prominent algorithms:

- NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II): A domination-based genetic algorithm known for its efficiency and use of crowding distance [36] [37].

- MOPSO (Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization): A swarm intelligence algorithm adapted from Particle Swarm Optimization for multi-objective problems [38] [39].

- MOPO (Multi-Objective Parrot Optimizer): A recently introduced (2025) swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by the foraging behavior of parrots [37].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of these algorithms.

Table 1: Core Algorithm Characteristics

| Feature | NSGA-II | MOPSO | MOPO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Type | Genetic Algorithm | Particle Swarm Optimization | Parrot Swarm Optimization |

| Core Inspiration | Biological Evolution | Social Behavior of Birds/Fish | Foraging Behavior of Parrots |

| Key Selection Mechanism | Non-dominated Sorting & Crowding Distance [36] | Non-dominated Ranking & Crowding Distance [37] | Non-dominated Ranking & Crowding Distance [37] |

| Primary Application Shown | Benchmark Problems (ZDT1) [36] | Continuous Function Minimization [38] | CEC'2020 Benchmarks & Engineering Design [37] |

| Key Strength | Good distribution of solutions [40] | Computational efficiency [40] | Superior performance on multiple metrics (HV, GD, Spread) [37] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a priori and a posteriori methods in multi-objective optimization?

A: In a priori methods, the decision-maker must specify preferences (e.g., weights for different objectives) before the optimization run. The algorithm then finds a single solution matching these preferences. In contrast, a posteriori methods, like NSGA-II, MOPSO, and MOPO, first find a set of Pareto-optimal solutions and then the decision-maker selects one after the optimization. This is more flexible as it reveals the trade-offs between objectives [37].

Q2: My algorithm is converging prematurely to a local Pareto front. What strategies can I use to improve global exploration?

A: Premature convergence is a common challenge. Algorithm-specific strategies include:

- For MOPSO: Implement a mutation operator to perturb particles and help them escape local optima [38] [39].

- For MOPO: The algorithm inherently uses an archive of non-dominated solutions and a crowding distance operator to promote diversity and exploration [37].

- General Approach: Adjust algorithm parameters to favor exploration over exploitation (e.g., increase mutation rates, inertia weight in PSO variants) and ensure your archive/repository size is large enough to maintain diverse solutions.

Q3: How do I choose an algorithm for my specific multi-objective problem in drug discovery?

A: The choice depends on your problem's characteristics and priorities.

- NSGA-II is a well-established, general-purpose choice with proven effectiveness in many domains, including molecular design [17] [2].

- MOPSO is often computationally efficient and can be a good choice for problems where speed is critical [40].

- MOPO is a newer algorithm that has demonstrated superior performance on benchmark problems and complex engineering challenges, making it a strong candidate for demanding applications [37]. Empirical testing on a simplified version of your problem is always recommended.

Troubleshooting Guides

NSGA-II: Poor Distribution of Solutions on the Pareto Front

Problem: The solutions found by NSGA-II are clustered in a small region of the Pareto front, providing poor trade-off options.

Diagnosis & Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient selective pressure for diversity | Check the spread of crowding distance values in the final population. | Ensure the crowding distance operator is correctly implemented and used for survival selection when splitting fronts [36]. |

| Population size too small | Increase the population size and observe if the distribution improves. | Use a larger population size (pop_size) to allow for better coverage of the front [36]. |

| Loss of extreme solutions | Check if the solutions at the extremes of the objective space are present. | Verify that your implementation assigns an infinite crowding distance to extreme points, ensuring their preservation [36]. |

MOPSO: Finding the Global Best (gBest) Particle

Problem: Selecting the global best guide (gBest) for each particle from the non-dominated set is challenging and can negatively affect convergence and diversity [39].

Diagnosis & Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

Poor gBest selection strategy |

Analyze if the gBest selection is biased towards a specific region of the front. |

Implement a more effective Pareto-optimal solution searching strategy, such as the Sigma method or other techniques that balance global and local search [39]. |

| Repository (archive) overcrowding | Check the number of non-dominated solutions in the archive. | Use a crowding distance or density-based method to prune the archive when it becomes too full, maintaining a diverse set of leaders [38]. |

| Lack of mutation | Review if the algorithm includes a mutation step. | Introduce a mutation operator to perturb the particles' positions or the gBest selections, enhancing exploration [38]. |

MOPO: General Workflow and Parameter Tuning

Problem: As a new algorithm, users may be unsure how to implement and tune MOPO effectively.

Diagnosis & Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unfamiliarity with the algorithm's structure | Review if the archive update and position update rules are correctly implemented. | Follow the detailed methodology from the source paper [37]. The core steps involve using an external archive to store non-dominated solutions and using crowding distance to manage its diversity. Parrots update positions based on this archive. |

| Suboptimal performance on a specific problem | Compare the Hypervolume (HV) and Generational Distance (GD) metrics with known benchmarks. | Fine-tune the parameters specific to the parrot's foraging behavior, such as the rates for different movement patterns (flight, perch, forage). The original study found MOPO robust across various tests [37]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Testing Protocol for Algorithm Comparison

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons between NSGA-II, MOPSO, and MOPO, follow this standardized protocol:

- Benchmark Problems: Select a diverse set of benchmark problems with different characteristics (e.g., convex, concave, disconnected Pareto fronts). The CEC'2020 multi-objective benchmark suite is a modern choice used in MOPO's evaluation [37].

- Performance Metrics: Calculate multiple metrics to assess different aspects of performance:

- Hypervolume (HV): Measures the volume of objective space dominated by the solutions (combines convergence and diversity) [37].

- Inverted Generational Distance (IGD/IGDX): Measures the distance from the true Pareto front to the obtained front [37].

- Generational Distance (GD): Measures how far the obtained solutions are from the true Pareto front [37].

- Spacing & Maximum Spread: Assess the distribution and extent of the solution set [37] [40].

- Statistical Validation: Perform multiple independent runs of each algorithm. Use non-parametric statistical tests like the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine the significance of performance differences [37].

- Parameter Tuning: All algorithms should be tuned to their best-known parameter settings for the specific benchmark problem to ensure a fair comparison.

The workflow for this comparative analysis is outlined below.

Protocol for Multi-Objective Drug Design (de novo Drug Design)

In de novo drug design (dnDD), the goal is to create novel molecules that optimize multiple properties like potency, novelty, and synthetic feasibility [17] [2]. The following protocol integrates multi-objective EAs into this pipeline.

Problem Formulation:

- Objectives: Define 2-4 key objectives (e.g., maximize binding affinity, maximize drug-likeness (QED), minimize synthetic accessibility score).

- Constraints: Define molecular constraints (e.g., permissible atoms, molecular weight range, no pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS)).

- Representation: Choose a molecular representation (e.g., SMILES strings, molecular graphs).

Algorithm Execution:

- Initialization: Generate an initial population of random or seed molecules.

- Evaluation: Calculate all objective functions for each molecule in the population.

- Evolution: Apply the multi-objective EA (NSGA-II/MOPSO/MOPO) for a fixed number of generations. This involves:

- Selection: Selecting parent molecules based on non-dominated rank and crowding distance.