Optimizing Photoredox Reactions with High-Throughput Experimentation: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to leverage High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in optimizing photoredox catalysis.

Optimizing Photoredox Reactions with High-Throughput Experimentation: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to leverage High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) in optimizing photoredox catalysis. Covering foundational mechanisms to advanced applications, it explores catalyst selection, reaction engineering, and scalable heterogeneous systems. A comparative analysis with electrochemistry highlights strategic advantages, while a dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls. The guide synthesizes these insights into practical HTE workflows designed to accelerate the development of sustainable and efficient synthetic routes for pharmaceutical and biomedical innovation.

Understanding Photoredox Fundamentals: Mechanisms, Catalysts, and HTE Opportunities

Core Principles of Single-Electron Transfer and Photoredox Cycles

Core Principles and Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which a photoredox catalyst activates substrates?

A photoredox catalyst (PC) is a colored dye that absorbs visible light to form an electronically excited state (PC*). This excited state possesses two half-occupied frontier orbitals, enabling it to act as both a potent single-electron oxidant and a potent single-electron reductant simultaneously [1]. The electron in the higher-energy orbital can be transferred to an electron acceptor (A), reducing it. Conversely, the "hole" in the lower-energy orbital can accept an electron from an electron donor (D), oxidizing it [1]. This process allows colorless organic compounds, which cannot be directly activated by visible light, to be converted into reactive radical intermediates via single-electron transfer (SET) [1].

Q2: What are the oxidative and reductive quenching cycles, and how do I distinguish them?

The two primary catalytic cycles in photoredox catalysis are the Oxidative Quenching Cycle (OQC) and the Reductive Quenching Cycle (RQC). The key distinction lies in the first step the excited catalyst undertakes [1].

- Oxidative Quenching Cycle (OQC): The photoexcited catalyst (PC*) is first oxidized by an electron acceptor (A). This reduces the acceptor to a radical anion (A•−) and generates the oxidized catalyst (PC•+). The ground-state catalyst is then regenerated by a sacrificial electron donor (D), which is itself oxidized to a radical cation (D•+) [1].

- Reductive Quenching Cycle (RQC): The photoexcited catalyst (PC*) is first reduced by an electron donor (D'). This oxidizes the donor to a radical cation (D'•+) and generates the reduced catalyst (PC•−). The ground-state catalyst is then regenerated by a sacrificial electron acceptor (A'), which is reduced to a radical anion (A'•−) [1].

Q3: My photoredox reaction fails to initiate, or proceeds very slowly. What are the primary causes?

Several factors can lead to reaction failure or low conversion. Please consult the troubleshooting table below.

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Diagnostic Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst & Light Source | Incorrect light wavelength | Ensure your light source emits at a wavelength matching the catalyst's absorption profile (e.g., blue LEDs for Ir(ppy)₃). Avoid using UV light if not required [1]. |

| Insufficient light penetration | For scale-up, ensure the reaction vessel is suitable for good light penetration. Stirring efficiently is critical. | |

| Reaction Components | Redox potential mismatch | Verify that the redox potentials of your substrates are thermodynamically matched to the excited-state potentials of your photocatalyst. Consult redox potential charts [2]. |

| Quenching of the excited state | Check if any components (e.g., substrates, bases) are quenching the catalyst's excited state. Stern-Volmer experiments can identify quenchers [2]. | |

| Lack of sacrificial reagent | In non-redox-neutral cycles, a sacrificial electron donor (e.g., triethylamine) or acceptor is essential to regenerate the ground-state catalyst [1]. Confirm its presence and integrity. | |

| Experimental Setup | Oxygen contamination | Oxygen is a potent quencher of excited states and reacts with radical intermediates. Ensure the reaction mixture is thoroughly degassed with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) before irradiation. |

| Solvent choice | The solvent affects ion-pairing and the stability of radical intermediates. Ensure the solvent does not react with the generated radicals and allows for outer-sphere electron transfer [2]. |

Essential Methodologies for Reaction Optimization

Protocol 1: Standard Procedure for a Degassed Photoredox Reaction

This protocol provides a general method for setting up a photoredox reaction, emphasizing key steps to ensure reproducibility.

- Preparation: In a vial, weigh out the photocatalyst (typically 0.1-2 mol%), substrate, and any other reagents (sacrificial donors/acceptors, bases).

- Solution Preparation: Transfer the solids to a Schlenk flask or a reaction vial suitable for irradiation. Add the solvent via syringe.

- Degassing: Seal the vessel with a septum and purge the headspace with an inert gas (Ar or N₂) for 15-20 minutes. Alternatively, use a minimum of 3-5 freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Irradiation: Place the sealed vessel at a fixed distance from the LED light source (e.g., blue LEDs, ~450 nm). Begin vigorous stirring.

- Monitoring & Work-up: Monitor reaction progress by TLC, GC-MS, or LC-MS. After completion, turn off the light source and open the reaction vessel. Work up as required for the specific transformation.

Protocol 2: Investigating Chain Propagation via Intermittent Illumination

Certain photoredox reactions proceed via radical chain mechanisms, where the photochemical step only initiates a self-propagating chain. Intermittent illumination can help characterize this [3].

- Setup: Use a photoreactor equipped with a programmable shutter or an LED controller capable of generating precise on/off light cycles (e.g., 1 second on, 9 seconds off).

- Execution: Run the reaction under intermittent light and, in parallel, under continuous illumination.

- Analysis: Compare the reaction yields and rates. If the reaction proceeds efficiently with intermittent light, it suggests a radical chain process with a long chain length, as the propagation continues in the dark. This knowledge is crucial for HTE and scale-up, as it indicates the photon efficiency of the reaction [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Common Components in Photoredox Catalysis and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts (e.g., [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Ir(ppy)₃) | Serve as the photoredox catalyst. They absorb visible light to form long-lived triplet excited states capable of single-electron transfer. Iridium complexes often provide stronger redox potentials [2] [4]. |

| Organic Dyes (e.g., Eosin Y, Mes-Acr⁺) | Metal-free alternatives as photoredox catalysts. They are often inexpensive and less toxic, though their excited-state lifetimes are typically shorter than metal complexes [2]. |

| Sacrificial Electron Donors (e.g., DIPEA, TEA) | Consumed stoichiometrically to regenerate the photocatalyst in an Oxidative Quenching Cycle (OQC). They are oxidized to radical cations and typically discarded [1]. |

| Sacrificial Electron Acceptors (e.g., O₂, persulfates) | Consumed stoichiometrically to regenerate the photocatalyst in a Reductive Quenching Cycle (RQC). They are reduced to radical anions [1]. |

| CBr₄ | Functions as an electron acceptor in oxidative transformations. For example, it is used in the controlled oxidative desulfurization of thioureas to synthesize thioamidoguanidines [5]. |

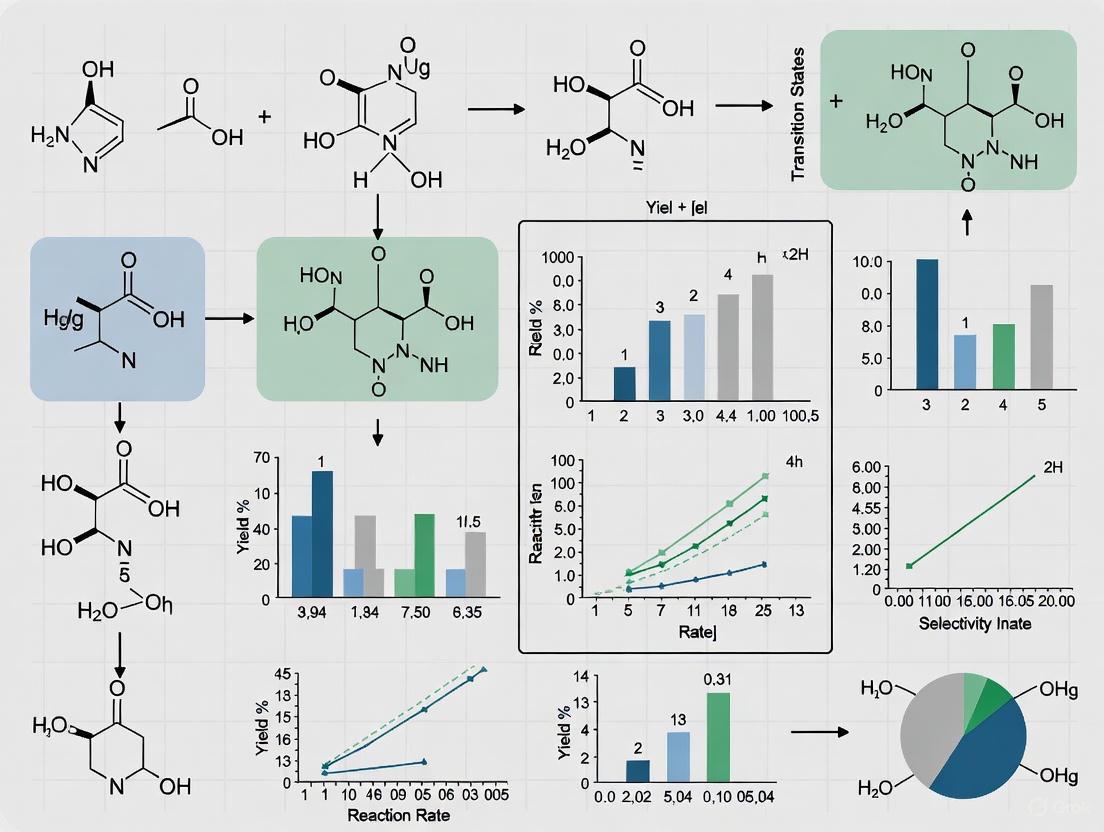

Reaction Mechanism Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core cycles of photoredox catalysis, including the generation of radical intermediates and the role of sacrificial reagents.

Diagram: Photoredox Catalytic Cycles. This diagram shows the two main pathways: the Oxidative Quenching Cycle (red), where the excited catalyst is first oxidized, and the Reductive Quenching Cycle (blue), where it is first reduced. Both pathways generate radical intermediates (green) for synthesis.

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for developing and troubleshooting a photoredox reaction, from initial setup to data analysis.

Diagram: Photoredox Reaction Workflow. A logical workflow for executing and troubleshooting a photoredox catalysis experiment, highlighting key decision points and common optimization paths.

FAQ: Catalyst Selection and Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the fundamental operational differences between transition metal complexes and organic dyes in photoredox catalysis?

The core difference lies in their structure and mechanism. Transition metal complexes, such as Ru(bpy)₃²⁺, operate via Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT). When excited by visible light, an electron is promoted from a metal-centered orbital to a ligand-centered π* orbital. This creates a long-lived triplet excited state that can act as both a strong oxidant and a strong reductant, engaging in single-electron transfer (SET) processes via either oxidative or reductive quenching cycles [6].

Organic dyes, in contrast, are purely organic molecules that absorb visible light to form excited states capable of similar SET processes. They can engage in photoredox cycles through electron transfer, energy transfer (EnT), or even direct hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) [7]. Their key advantage is modular tunability; their redox and spectroscopic properties can be finely adjusted through synthetic modification of their organic structure [7].

Q2: My photoredox reaction is not proceeding, despite confirmed light absorption by the catalyst. What could be the issue?

This is a common problem often related to an incorrect match between the catalyst's redox potential and the substrate's requirements. Please consult the quantitative data in Table 1 to verify that your catalyst's excited-state reduction potential (E1/2(M*/M-)) is sufficiently negative to reduce your substrate, or that its excited-state oxidation potential (E1/2(M+/M*)) is sufficiently positive to oxidize it [6].

Furthermore, ensure you are using the correct reaction vessel. Due to the Beer-Lambert law, photon penetration is limited in traditional batch reactors, with reactions typically occurring only within a ~2 mm zone from the vessel wall [8]. For better efficiency and more reproducible results, especially in High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), consider transferring your reaction to a flow system or using a microscale HTE platform designed to simulate flow conditions [8].

Q3: When should I prioritize an organic dye over a transition metal complex for my HTE campaign?

Organic dyes should be prioritized when cost, sustainability, and toxicity are primary concerns. They are generally less expensive, derived from abundant elements, and avoid the use of rare metals like ruthenium and iridium [7] [9]. They are particularly advantageous when your reaction requires a strongly oxidizing catalyst, as certain acridinium salts can reach excited-state potentials up to ~2.0 V [7]. Their ease of structural fine-tuning also makes them ideal for bespoke catalyst development using machine-learning-guided approaches [9].

Q4: How can I rapidly optimize a photoredox reaction for scale-up using HTE principles?

A modern approach involves using a Flow Simulation (FLOSIM) HTE platform. This involves running parallel microscale reactions (e.g., in a 96-well glass plate) where the solution height is carefully controlled to match the internal diameter of a target flow reactor's tubing. This "path-length matching" ensures that the light penetration in the HTE system mimics that of the flow system, allowing for direct translation of optimal conditions [8]. Key parameters to screen in this setup include catalyst identity, light wavelength/intensity, residence time, base, and solvent. The optimal conditions identified at the microscale can then be seamlessly transferred to a continuous-flow reactor for larger-scale synthesis [8].

Quantitative Data for Catalyst Comparison

The following table summarizes key properties of common photoredox catalysts, which are critical for selecting the right catalyst for a given transformation.

Table 1: Properties of Common Transition Metal and Organic Photoredox Catalysts

| Catalyst | Type | Key Redox Potentials (V vs. SCE)* | Key Absorption (nm) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ | Transition Metal | E1/2(III/*II) = -0.81E1/2(*II/I) = +0.77 [6] |

~450-460 [6] | Well-understood, balanced redox profile, long-lived excited state. |

| Mes-Acr-Ph⁺ (OD3) | Organic Dye (Acridinium) | E(PC+*/PC) ≈ +2.0 [7] |

- | Very strong oxidant in its excited state. |

| 4CzIPN | Organic Dye (Cyanoarene) | - | - | Strong reductant in its excited state; widely used in dual catalysis. |

| Rhodamine 6G (OD14) | Organic Dye (Xanthene) | E(PC+*/PC) ≈ +1.2 [7] |

- | Good oxidant, commonly available. |

*SCE = Saturated Calomel Electrode. Potentials can be tuned via ligand substitution (metal complexes) or structural modification (dyes).

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for FLOSIM-HTEC High-Throughput Photoredox Optimization

This protocol enables the rapid optimization and scale-up translation of photoredox reactions [8].

- Reaction Validation: First, confirm that the desired photoredox reaction works in a standard batch setup under previously reported or initial conditions.

- Wavelength Screening: Using the batch setup, screen different wavelengths (e.g., using Kessil PR160 LEDs) to identify the most effective one for your transformation.

- HTE Plate Preparation: Inside a nitrogen-filled glovebox, prepare reaction mixtures in a 96-well glass plate. A key design factor is to pipette a precise volume of reaction solution such that the solution height in the well matches the internal diameter of the intended flow reactor's FEP tubing (e.g., ~1-2 mm).

- FLOSIM Irradiation: Seal the plate with a transparent film and place it in the benchtop HTE device. Irradiate the plate for a duration equivalent to the desired residence time in the future flow system.

- Analysis and Iteration: Analyze the crude reaction mixtures via UPLC. Use the results to inform the next set of conditions (e.g., varying catalyst, base, concentration) and repeat steps 3-5 until optimal performance is achieved.

- Translation to Flow: Directly apply the optimal conditions (catalyst, concentration, solvent, residence time) identified in the FLOSIM platform to a commercial flow reactor (e.g., Vapourtec E-Series) with a matching tube diameter.

Protocol for Bayesian Optimization of Organic Photocatalyst Formulations

This data-driven protocol is used to discover and optimize new organic photocatalysts for specific reactions, such as metallaphotoredox cross-couplings [9].

- Virtual Library Design: Define a large virtual library of potentially synthesizable organic dye candidates based on a reliable and diversifiable scaffold (e.g., a cyanopyridine (CNP) core built via the Hantzsch pyridine synthesis).

- Molecular Descriptor Encoding: Compute a set of molecular descriptors (e.g., 16 descriptors capturing thermodynamic, optoelectronic, and excited-state properties) for each candidate in the virtual library to map the chemical space.

- Initial Sampling: Select a small, diverse set of molecules (e.g., 6 candidates) from the virtual library using an algorithm like Kennard-Stone (KS) to obtain initial data points.

- Synthesis and Testing: Synthesize and test these initial candidates under standardized reaction conditions. The average reaction yield from replicates serves as the objective metric.

- Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Model Building: Use the experimental data to build a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model that predicts reaction yield based on the molecular descriptors.

- Informed Selection: The Bayesian optimization algorithm queries the model to select the next most promising batch of candidate molecules (e.g., 12 molecules) for synthesis and testing, aiming to maximize the predicted yield.

- Iteration: Update the model with the new experimental results and repeat the process. This active learning loop efficiently navigates the vast chemical space to find high-performing catalysts with minimal experimental effort.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Catalyst Selection and Reaction Optimization Workflow

Photoredox Catalytic Cycles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Photoredox HTE

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ | Transition Metal Photocatalyst | Provides a balanced, well-understood catalyst for initial reaction scouting [6]. |

| 4CzIPN | Organic Photocatalyst | A strongly reducing organic dye as a metal-free alternative for specific transformations [9]. |

| Mes-Acr-Ph⁺ (OD3) | Organic Photocatalyst | A very strong oxidant for challenging substrate activation, such as decarboxylation [7]. |

| NiCl₂·glyme / dtbbpy | Transition Metal Cross-Coupling Catalyst | Forms the nickel catalytic cycle in dual metallaphotoredox cross-coupling reactions [9]. |

| Cs₂CO₃ | Base | Commonly used to deprotonate substrates and facilitate electron transfer processes [8] [9]. |

| Kessil PR160 LEDs | Light Source | Tunable wavelength, high-intensity light source for precise photocatalysis in HTE and flow [8]. |

| 96-Well Glass Plates | HTE Reaction Vessel | Enables parallel microscale reaction screening with excellent light transmission [8]. |

| FEP Tubing | Flow Reactor Component | Material for flow reactor coils; transparent to visible light and chemically resistant [8]. |

FAQs: Core Photophysical Concepts for Reaction Optimization

1. What are the key photophysical properties I need to monitor in photoredox HTE? The three most critical properties for optimizing photoredox reactions in high-throughput experimentation (HTE) are excited-state lifetimes, redox potentials in the excited state, and light absorption characteristics. These properties directly determine if your catalyst can be excited by your light source, how long it remains reactive, and whether it has sufficient energy to transfer an electron to or from your substrate [10] [11].

2. Why is my photoredox reaction failing despite a high catalyst loading? This could be due to a mismatch between the catalyst's excited-state redox potential and your substrate's redox potential. For a successful electron transfer, the excited catalyst must be a strong enough reductant or oxidant. Specifically, for the catalyst to oxidize a substrate, its excited-state oxidation potential (Eox) must be more negative than the substrate's reduction potential. Conversely, for the catalyst to reduce a substrate, its excited-state reduction potential (Ered) must be more positive than the substrate's oxidation potential [11]. Check these values first.

3. How can I reduce photobleaching and blinking of my organic dye in single-molecule studies? Unwanted photophysical processes like blinking and photobleaching are often exacerbated by the presence of oxygen and can be mitigated by using small-molecule solution additives. Compounds such as cyclooctatetraene (COT), Trolox, and 4-nitrobenzyl alcohol (NBA) have been shown to act as triplet state quenchers, favorably attenuating blinking and photobleaching in a concentration-dependent manner [12]. Using an enzymatic oxygen scavenging system is also a common strategy.

4. My reaction seems inefficient. How does excited-state lifetime affect my photoredox catalysis yield? The excited-state lifetime (τ) dictates the time window available for your catalyst to collide with and react with a substrate. It is calculated as τ = 1 / (kr + knr), where kr and knr are the radiative and non-radiative decay rate constants, respectively [10]. A short lifetime may mean the catalyst decays back to its ground state before a productive collision can occur. If your substrate concentration is low, a catalyst with a longer lifetime (e.g., one that undergoes intersystem crossing to a triplet state) is often preferable.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Reaction Yield | Mismatched redox potentials | Measure/compare Eox or Ered of catalyst with Ered or Eox of substrate [11] | Select a photocatalyst with a more powerful excited-state potential |

| Short catalyst excited-state lifetime | Consult literature for the catalyst's reported lifetime (τ) [10] | Switch to a catalyst with a longer triplet-state lifetime (e.g., metal complexes) | |

| Inner filter effect | Check if substrates/products absorb significantly at the excitation wavelength | Dilute reaction mixture or use a different wavelength | |

| Catalyst Deactivation (Photobleaching) | Oxygen-mediated degradation | Run reaction under inert atmosphere or with degassed solvents | Use an oxygen scavenging system (e.g., glucose oxidase/catalase) [12] |

| Formation of long-lived reactive states | Add triplet state quenchers like COT or Trolox [12] | ||

| Irreproducible Results | Inconsistent light absorption | Verify light source stability and alignment; ensure solution is homogeneous | Use a chemical actinometer to calibrate photon flux for each run |

| Deviation from Beer-Lambert Law | Check for high concentration or absorbing species causing light gradient [13] | Lower catalyst concentration to ensure uniform light penetration |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Additives for Stable Performance

The following table lists common additives used to suppress unwanted photophysical pathways and enhance experimental outcomes, particularly in sensitive applications like single-molecule fluorescence [12].

| Reagent | Function | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Trolox | Triplet state quencher; reduces blinking and photobleaching | smFRET imaging; photoredox catalysis requiring extended irradiation |

| Cyclooctatetraene (COT) | Triplet state quencher; attenuates dark-state formation | Used in cocktail with other additives to tune dye performance |

| 4-Nitrobenzyl Alcohol (NBA) | Reduces prevalence of long-lived dark states; decreases blinking | Effective in complex environments like ribosome imaging |

| Enzymatic O₂ Scavengers | Removes molecular oxygen to prevent photobleaching | Essential for most single-molecule fluorescence experiments |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | Reductant; can suppress blinking but may promote photobleaching | A common, though not always optimal, additive |

Quantitative Data for Common Organophotocatalysts

Selecting the right photocatalyst requires comparing its quantitative photophysical properties. The following table provides key data for frequently used organocatalysts, crucial for predicting electron transfer feasibility and matching light sources [11].

| Photocatalyst | Absorbance Max (λ_max) | Excited State | Ered (cat/cat•−) | Eox (cat•+/cat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosin Y | 520 nm | Triplet | +0.83 V | -1.15 V |

| Methylene Blue | 650 nm | Triplet | +1.14 V | -0.33 V |

| Rose Bengal | 549 nm | Triplet | +0.81 V | -0.96 V |

| Mes-Acr | 425 nm | Singlet | +2.32 V | - |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Quantum Yield by Comparative Method The quantum yield (Φ) is the efficiency of a photophysical or photochemical process, defined as the number of events per photon absorbed [10].

- Select a Standard: Choose a standard fluorophore with a known quantum yield (Φ_std) that has an absorption spectrum similar to your sample (e.g., Rhodamine 6G).

- Measure Absorbance: Prepare solutions of the standard and your sample with absorbance below 0.1 at the excitation wavelength to avoid inner filter effects [10] [13].

- Record Emission Spectra: Using a fluorescence spectrometer, excite both samples at the same wavelength and intensity, and record their full emission spectra.

- Calculate Quantum Yield: Use the following formula, where Φ is the quantum yield, A is the integrated area under the emission spectrum, and η is the refractive index of the solvent. The subscripts "std" and "sam" refer to the standard and sample, respectively. Φsam = Φstd × (Asam / Astd) × (ηsam² / ηstd²)

Protocol 2: Using the Beer-Lambert Law for Concentration and Light Absorption This law relates the absorption of light to the properties of the material through which the light is traveling. It is fundamental for setting up reproducible photochemical reactions [13] [14].

- Instrument Setup: Use a UV-Vis spectrophotometer with a monochromatic light source.

- Prepare Sample: Dissolve your photocatalyst in the reaction solvent at a known, low concentration (typically < 0.01 M) to ensure absorbers act independently [13].

- Measure Blank: Place a cuvette filled only with solvent in the beam path and set the instrument to 100% transmission (0 Absorbance).

- Measure Sample: Replace the blank with your sample solution and record the absorbance (A) at the desired wavelength.

- Apply the Law: Use the Beer-Lambert law to calculate the concentration or molar absorptivity: A = ε c l

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance.

- ε is the molar attenuation coefficient or molar absorptivity (M⁻¹cm⁻¹).

- c is the concentration of the absorber (M).

- l is the path length of the cuvette (cm).

Visualization of Photophysical Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Excited State Decay and Reactivity Pathways. This chart shows the pathways for a molecule after light absorption, including radiative decay (fluorescence, phosphorescence) and non-radiative transitions (intersystem crossing) that lead to reactive states capable of electron transfer [10] [11].

Diagram: Photoredox Reaction Troubleshooting Logic. A systematic workflow for diagnosing the root cause of failures in photoredox catalysis experiments, based on key photophysical properties [10] [12] [11].

Identifying Key Variables for HTE Screening in Photoredox Reactions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my photoredox reaction optimized in a batch HTE plate not translating to my flow reactor? The most common cause is a mismatch in the effective light path length and photon flux between your high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platform and your flow system. In batch, a significant portion of your reaction mixture may be in shadow, while flow reactors are designed for uniform illumination. To solve this, ensure your HTE screening uses a well depth that matches the internal diameter of your flow reactor's tubing to simulate identical path lengths [8].

Q2: Which photophysical properties of the catalyst are most critical to screen? The key properties are the catalyst's oxidizing and reducing potentials in its excited state and its excited-state lifetime. The excited-state potentials determine if electron transfer with your substrates is thermodynamically favorable, while the lifetime determines if there is sufficient time for this electron transfer to occur [2]. These can be estimated using the Rehm-Weller equation or measured directly via specialized methods [2].

Q3: How can I prevent my reaction mixture from clogging the tubing in a flow reactor? During HTE optimization, closely monitor for the formation of precipitates. A key strategy is to use the HTE platform to identify homogeneous reaction conditions. This often involves screening different organic bases and solvent compositions to find a system where all components remain in solution throughout the reaction, thereby avoiding clogging in translational efforts [8].

Q4: What is a "backplate" and why is it appearing in my high-contrast UI?

In forced colors modes (like Windows High Contrast), browsers may automatically draw a solid background, or "backplate," behind text nodes. This ensures legibility when web pages use background images that might otherwise disappear in these modes. If this backplate is interfering with your custom high-contrast design for lab software, you can control its behavior using the forced-color-adjust CSS property [15] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Translation from HTE Batch to Flow

Symptoms: Reaction yield decreases significantly when moving from an optimized HTE batch plate to a continuous-flow reactor.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Light Path | Compare the depth of solution in your HTE well to the internal diameter (ID) of your flow tubing. | Use an HTE plate where the solution height matches the ID of your flow reactor tubing [8]. |

| Different Photon Flux | Measure the light intensity (e.g., with a radiometer) at the well surface vs. the flow reactor wall. | In your HTE device, use a light source that provides the same radiant flux per unit area as your target flow system [8]. |

| Insufficient Mixing in HTE | Check for yield variations between wells at the center and edge of the plate. | Ensure your HTE setup includes adequate agitation to mimic the mixing dynamics of a flow system [8]. |

Issue 2: Low Reaction Yield Across All Conditions

Symptoms: Consistently low yields in the HTE platform, regardless of parameter changes.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Electron Transfer | Perform a Stern-Volmer quenching study to see if your substrate(s) effectively quench the catalyst's excited state [2]. | Screen catalysts with a range of excited-state redox potentials to find one matched to your substrate [2]. |

| Low Cage Escape Yield | Review literature for similar reaction types and their typical performance. | Optimize solvent polarity and viscosity; these parameters significantly impact the separation of the radical ions after electron transfer. |

| Wavelength Mismatch | Check the absorption spectrum of your catalyst against your light source's emission spectrum. | Use a light source whose output overlaps strongly with the catalyst's absorption peak [8]. |

Key Variables for HTE Screening: Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Core Photoredox Catalyst Properties to Screen These intrinsic properties of the photocatalyst determine the thermodynamic feasibility and efficiency of the initial electron transfer step [2].

| Variable | Typical Range/Options | Impact on Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Type | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Ir(ppy)₃, Organic Dyes (e.g., Eosin Y) | Determines the available redox potentials and absorption wavelength. |

| Excited-State Redox Potential (E*₁/₂) | Varies by catalyst (e.g., Ru/Ir complexes: Strong oxidizer & reducer) | Must be sufficient to oxidize/reduce the reaction substrates. Can be estimated via the Rehm-Weller equation [2]. |

| Excited-State Lifetime (τ₀) | Nanoseconds to microseconds (e.g., [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺: ~1100 ns) [2] | Longer lifetime increases the chance of successful collisions and electron transfer with substrates. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for HTE Optimization These are the primary adjustable parameters in an HTE campaign for a photoredox reaction [8].

| Variable | Typical Screening Range | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Light Wavelength (λ) | 365 nm, 427 nm, 455 nm, 525 nm [8] | Must match the absorption profile of the photosensitizer for efficient excitation. |

| Light Intensity | Varies with LED power and distance | Higher intensity can increase reaction rate but may lead to side-reactions. |

| Residence/Reaction Time | Seconds to hours (flow residence time is a key variable) [8] | Optimizes conversion and can suppress decomposition pathways. |

| Base | Inorganic (e.g., Cs₂CO₃) or Organic (e.g., DIPEA) | Critical for deprotonation steps; organic bases often preferred for solubility in flow [8]. |

| Solvent Polarity | DMSO, DMF, MeCN, Toluene, MeOH | Affects solubility, redox potentials, and the cage escape efficiency after electron transfer. |

Experimental Protocol: The FLOSIM HTE Workflow

This protocol outlines the "Flow Simulation" (FLOSIM) method for directly translating photoredox reactions from a high-throughput batch platform to a flow reactor [8].

1. Principle To simulate the conditions of a flow photochemical reactor within a microscale HTE platform by matching the key parameters of light path length and radiant flux. This enables rapid, parallel optimization of reactions with high predictive accuracy for subsequent flow scale-up [8].

2. Materials and Equipment

- Light Source: Tunable LEDs (e.g., Kessil PR160 series) capable of emitting at various wavelengths [8].

- HTE Platform: A 96-well glass plate housed in a custom device with concave lenses and mirrors to ensure uniform light distribution across all wells [8].

- Inert Atmosphere: Nitrogen-filled glovebox for assembling air-sensitive reactions.

- Analysis: UPLC-MS for high-throughput reaction analysis.

3. Procedure Step 1: Reaction Validation. Confirm the model photoredox reaction works in standard batch mode under published conditions [8]. Step 2: Wavelength Screening. Using the HTE platform, screen the reaction across a range of LED wavelengths (e.g., 427 nm, 455 nm, 525 nm) to identify the most effective one [8]. Step 3: Path-Length Matching. In the 96-well glass plate, pipet a reaction volume such that the height of the solution equals the internal diameter of the target flow reactor's FEP tubing [8]. Step 4: Parameter Screening. In parallel, prepare wells with variations in: * Photocatalyst identity and loading. * Base (type and equivalence). * Solvent composition. * Substrate concentration. Step 5: FLOSIM "Reaction". Seal the plate with a transparent film, place it in the HTE device, and irradiate for a duration equivalent to the desired residence time in the flow system [8]. Step 6: Analysis and Translation. Analyze outcomes via UPLC. The optimal conditions identified are then directly applied to the commercial flow reactor (e.g., Vapourtec E-Series) using the same wavelength, concentration, and residence time [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photoredox HTE Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Photocatalysts | Absorbs light to generate potent redox agents in its excited state. | [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺, Ir(ppy)₃, Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy))⁺ [2] |

| Organic Photoredox Catalysts | Metal-free alternative for photoredox catalysis. | Eosin Y, Acridinium salts [2] |

| Stoichiometric Sacrificial Reagents | Consumed to permanently oxidize or reduce the catalyst, enabling a catalytic cycle. | DIPEA, Hantzsch ester (reductants); Na₂S₂O₈ (oxidant) |

| Solvents for Photoredox | Medium that can dissolve components and affects electron transfer efficiency. | Acetonitrile (MeCN), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) |

| Transparent HTE Plates | Vessel for microscale reactions that allows maximum light penetration. | 96-well glass plates [8] |

| FEP Tubing | Standard material for flow photoreactors due to its high transparency. | Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) coils [8] |

HTE Workflows and Reaction Engineering for Scalable Photoredox Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my photoredox reaction in the HTE plate showing inconsistent yields across different solvent conditions? Inconsistent yields are often due to solvent-dependent quenching of the photocatalyst's excited state or variations in solvent polarity affecting reaction intermediate stability [17]. Ensure solvents are anhydrous and of high purity, as trace water can deactivate certain catalysts or intermediates. Check that the solvent fully dissolves all reactants to prevent concentration gradients during dispensing.

Q2: How can I troubleshoot low conversion across all catalyst libraries in my [2+2] cycloaddition screen? Low conversion typically indicates an issue with photon flux or catalyst activation [17]. First, verify that your light source emission spectrum overlaps with your catalysts' absorption profiles. Second, ensure that PCN-based or other heterogeneous catalysts are properly immobilized on glass beads or fibers to maximize light penetration and surface area in flow reactors [17]. Third, check oxygen exclusion, as oxygen can quench photocatalyst excited states.

Q3: What causes precipitation in reaction wells during screening, and how can it be prevented? Precipitation occurs due to poor solubility of reactants, catalysts, or products in specific solvent-library combinations [17]. Pre-test compound solubility in a representative subset of solvents. Include co-solvents like DMSO or ethanol (10-20%) in problematic screens, or use higher dilution. For heterogeneous catalysts, ensure particle size is controlled to prevent clogging in flow systems [17].

Q4: My HTE results show high variability between replicates. What are the potential sources of this error? Technical variability often stems from liquid handling inaccuracies, uneven illumination across the plate, or oxygen sensitivity [17]. Calibrate pipettes and ensure homogeneous mixing after reagent addition. Use parallel photoredox flow reactors for consistent light exposure [17]. Implement rigorous glovebox procedures for oxygen-sensitive reactions and include control reactions to benchmark performance.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Screening Runs

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Deactivation | Compare catalyst color/precipitation pre/post-reaction. | Use fresh catalyst batches; implement stabilizers. |

| Oxygen Contamination | Run control with deliberate air exposure. | Enhance degassing techniques; use oxygen scavengers. |

| Light Intensity Fluctuations | Measure light output with radiometer at well positions. | Calibrate light sources regularly; use LED arrays with constant current. |

Problem: Low Selectivity in Cyclobutane Formation

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-irradiation | Monitor reaction progress with time sampling. | Optimize reaction time; use flow chemistry to control residence time [17]. |

| Incorrect Catalyst Loading | Run catalyst gradient screen (e.g., 0.1-5 mol%). | Optimize catalyst loading for selectivity versus activity. |

| Solvent Polarity Effects | Screen solvents across a polarity index. | Choose solvents that stabilize polarized transition states. |

Problem: Clogging in Photoredox Flow Reactors

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Catalyst Leaching | Analyze reaction mixture for catalyst metals. | Improve catalyst immobilization method on glass beads/fibers [17]. |

| Product Precipitation | Identify precipitation point via visual inspection. | Adjust solvent composition; increase temperature; use in-line filters. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immobilization of Polymeric Carbon Nitride (PCN) on Glass Beads for Flow Reactors [17]

- Prepare PCN Catalyst: Synthesize urea-derived PCN (UCN) by heating urea to 550°C for 4 hours in a muffle furnace under air. Confirm layered structure with XRD and measure BET surface area (~52 m²/g is optimal) [17].

- Functionalize Glass Beads: Acid-wash 3mm glass beads with HCl solution, rinse with deionized water, and dry at 120°C.

- Immobilize Catalyst: Prepare a suspension of 100 mg UCN in 20 mL ethanol. Add 10 g cleaned glass beads and stir gently for 1 hour. Evaporate solvent under reduced pressure while rotating to ensure uniform coating.

- Cure and Load: Dry the coated beads at 80°C for 2 hours. The final catalyst loading should be approximately 1 wt.% [17]. Pack the beads into the flow reactor column ensuring even distribution.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening of Solvent and Additive Libraries for [2+2] Photocycloaddition

- Library Preparation: Prepare a 96-well plate with solvent variations (nitromethane, acetonitrile, DMF) and additives (Lewis acids, Bronsted acids, bases) in a Cartesian array format. Use 2 mL glass vials as reaction wells.

- Reagent Dispensing: Via an automated liquid handler, add fixed concentrations of trans-anethole (0.1 M) and styrene (0.12 M) to each well.

- Catalyst Addition: Dispense a standard PCN catalyst stock suspension (5 mg/mL in reaction solvent, 10 µL) to each well. For homogeneous catalysts, use solutions at 1 mol% catalyst loading.

- Reaction Execution: Seal plate under inert atmosphere. Irradiate with white LED arrays (0.1 W/cm² intensity) with continuous shaking for 8 hours [17].

- Analysis: Quench reactions by removing light source. Sample aliquots from each well for UPLC-MS analysis to determine conversion and selectivity using calibrated standard curves.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Carbon Nitride (UCN) | Metal-free heterogeneous photocatalyst | Use 2-5 mol%; superior charge separation; recyclable [17]. |

| Nitromethane Solvent | High polarity reaction medium | Optimal for many PCN-catalyzed photocycloadditions; handle with care [17]. |

| Glass Beads (3mm) | Catalyst support in flow reactors | Provide high surface area for catalyst immobilization and enhance light penetration [17]. |

| White LED Array | Visible light source for photocatalysis | Ensure uniform 0.1 W/cm² intensity across reaction vessels [17]. |

| Oxygen Scavengers | Remove trace oxygen from reaction mixtures | Critical for reactions with oxygen-sensitive intermediates. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Implementing Heterogeneous Photoredox Catalysts for Simplified Workup and Reusability

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers integrating heterogeneous photoredox catalysts into high-throughput experimentation (HTE) workflows. These materials offer significant advantages over homogeneous systems, including simplified catalyst recovery, reuse potential, and minimized metal contamination in products—critical factors for accelerating reaction optimization and drug development pipelines. The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs address specific experimental challenges documented in recent literature.

★ Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Heterogeneous Photoredox Catalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogenized Iridium Catalyst (e.g., Al₂O₃–Ir) | Precious metal photoredox catalyst immobilized on a solid support (e.g., Al₂O₃ nanopowder) via a surface-anchoring group [18]. | Enables very low loadings (0.01-0.1 mol %), recovery, and reuse [18]. |

| Redox-Active Sacrificial Reagents (e.g., TEOA, Hünig's base) | Acts as an electron donor (reductive quencher) to regenerate the catalyst ground state [18]. | Essential for certain reaction mechanisms like ATRA and oxidative hydroxylation [18]. |

| Solvent Systems (DCM, DCE, DMF, EtOAc, THF, Toluene) | Reaction medium compatible with the heterogenized catalyst [18]. | Prevents significant catalyst desorption/leaching. Avoid MeCN, MeOH, CHCl₃, DMSO, and H₂O [18]. |

| Solid Support (Aluminum Oxide, Al₂O₃) | Redox-inactive, insulating metal oxide support for the organometallic catalyst [18]. | Provides a robust, high-surface-area platform, allowing for easy separation from the reaction mixture [18]. |

| Metal Scavengers | Resins or silica-based materials to remove leached metal contaminants from the product stream [19]. | Used as a troubleshooting step if minor catalyst leaching is detected. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my heterogeneous catalyst activity decreasing over multiple reuse cycles? Catalyst deactivation is a common challenge. Potential causes include:

- Poisoning/Fouling: Strong adsorption of reaction byproducts or impurities onto the catalyst's active sites can block access [20] [19].

- Leaching/Desorption: Active metal species can leach into the solution, especially in incompatible solvents, leading to irreversible loss [18] [19].

- Structural Degradation: Irreversible structural changes, such as sintering of metal nanoparticles or destruction of coordination structures (e.g., in MOFs), can occur over time [20].

- Carbon Deposition: Formation of carbonaceous layers ("coke") on the catalyst surface during reaction can deactivate it [19].

Q2: My reaction yield is low with the heterogeneous catalyst, but it works well with a homogeneous analog. What could be wrong? This often relates to mass transfer limitations.

- In a slurry reactor, pollutant molecules and reagents must diffuse to the catalyst surface, and products must diffuse away [20]. Aggregation of catalyst nanoparticles can reduce the accessible surface area.

- Ensure efficient mixing or agitation to enhance contact between the solid catalyst and dissolved substrates [20].

Q3: I am having trouble separating the fine catalyst powder from the reaction mixture via filtration. What are my options? Traditional filtration can be slow. Consider these alternatives:

- Centrifugation: A faster and more efficient method for separating fine powders on a laboratory scale [18] [19].

- Magnetic Separation: If using a catalyst supported on magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄), separation can be achieved rapidly using a simple magnet, minimizing solvent use and waste [19].

- Catalyst Immobilization on Fixed-Bed or Monoliths: For continuous flow systems, immobilizing the catalyst on a fixed bed or within a monolithic reactor completely eliminates the separation step [20].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield | 1. Catalyst poisoning or fouling.2. Mass transfer limitations.3. Sub-optimal light penetration. | 1. Characterize spent catalyst (TGA, XPS) to identify poisons; implement a regeneration protocol (e.g., calcination) [19].2. Increase agitation speed; reduce catalyst loading to minimize aggregation [20].3. Ensure reactor design allows uniform light distribution; use thinner reaction vessels or internal light sources [20]. |

| Catalyst Leaching | 1. Use of incompatible solvent.2. Weak catalyst-support interaction. | 1. Confirm solvent compatibility. Soak catalyst in deoxygenated solvent for 2+ hours, then analyze supernatant by UV-Vis for characteristic absorption bands (e.g., ~370 nm for Ir complexes) [18].2. Switch to a solvent with low desorption potential (e.g., DCM, DCE, THF, Toluene) [18]. |

| Difficulty with Catalyst Recovery | 1. Catalyst particle size is too small for efficient filtration.2. Catalyst forms stable colloids. | 1. Employ high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 10,000 RPM) instead of gravity filtration [18] [19].2. Utilize a magnetic nanocatalyst support for rapid separation with a magnet [19]. |

| Loss of Activity Upon Reuse | 1. Progressive leaching of active metal.2. Irreversible catalyst degradation. | 1. Analyze recovered catalyst and reaction filtrate via ICP-MS to quantify metal loss [19].2. If degradation is confirmed, the catalyst has reached its end-of-life. Explore metal recovery from the spent catalyst (e.g., via combustion or plasma arc technology) [19]. |

★ Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solvent Compatibility Screening for Al₂O₃–Ir Catalyst

This procedure is critical for ensuring catalyst stability and preventing leaching before running any reaction [18].

Materials:

- Heterogenized Al₂O₃–Ir catalyst

- Test solvents (e.g., DCM, MeCN, MeOH, DMF, THF, DCE, etc.)

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Centrifuge

- Fine frit filter

Method:

- In a series of vials, add a fixed mass (e.g., 5 mg) of the Al₂O₃–Ir catalyst to 2 mL of each deoxygenated solvent.

- Seal the vials and irradiate with visible light for 2 hours under agitation.

- Centrifuge the mixtures to separate the solid catalyst.

- Carefully decant and filter the supernatant through a fine frit to remove any residual particles.

- Record the UV-Vis spectrum of each filtered supernatant from 300-450 nm.

- Analysis: A significant absorption band around 370 nm indicates desorption of the molecular Ir(dcabpy)(ppy)₂ complex from the support. Solvents showing no such peak (e.g., DCM, DCE, THF, Toluene) are suitable for use [18].

Protocol 2: Gram-Scale Perfluorination via Atom-Transfer Radical Addition (ATRA)

This protocol demonstrates the scalability of heterogeneous photoredox catalysis [18].

Materials:

- Al₂O₃–Ir catalyst (0.01 mol%)

- 5-hexene-1-ol

- Perfluoroalkyl iodide (e.g., C₆F₁₃I)

- Solvent: 4:3 Methanol/Acetonitrile (a uniquely compatible mixed solvent for Al₂O₃–Ir [18])

- Blue LEDs (~ 450 nm)

Method:

- Charge a photoreactor (e.g., a round-bottom flask equipped with a stir bar and LED strip) with 5-hexene-1-ol (1.0 equiv, ~16 mmol), perfluoroalkyl iodide (1.5 equiv), and Al₂O₃–Ir (0.01 mol%).

- Add the 4:3 MeCN/MeOH solvent mixture to achieve a homogeneous solution.

- Degas the reaction mixture by purging with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes.

- Irradiate the vigorously stirred mixture with blue LEDs at room temperature for 24 hours. Monitor reaction progress by TLC or GC-MS.

- Upon completion, separate the catalyst by centrifugation.

- Wash the recovered catalyst with a compatible solvent (e.g., DCM) for reuse.

- Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure and purify the crude material by flash chromatography to isolate the perfluorinated ATRA product.

- Expected Outcome: >90% isolated yield at gram-scale [18].

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Heterogeneous Photoredox Catalyst Lifecycle

The following diagram illustrates the complete lifecycle of a heterogeneous catalyst, from reaction to final disposal, which is crucial for planning HTE workflows and sustainability assessments.

Oxidative Quenching Catalytic Cycle

This diagram details the electron transfer mechanism for an oxidative quenching cycle, a fundamental pathway in photoredox reactions such as the ATRA reaction described in Protocol 2.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Photoredox Reaction Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | - Incorrect light source/wavelength [21]- Inefficient catalyst turnover [22]- Sub-optimal reactor setup/light penetration [21] | - Verify light source matches catalyst absorption [21]- Re-optimize terminal oxidant/reductant concentration [22]- Ensure proper mixing and use a temperature-controlled reactor [21] |

| Poor Selectivity (Lactonization) | - Competing reaction pathways [23] | - For lactonization, adjust photocatalyst/use chiral ligands [23]- For C-H functionalization, explore HAT catalysts or PCET conditions [24] |

| Slow Reaction Rate | - Low photon flux or incorrect light intensity [21]- Catalyst decomposition [22] | - Increase light intensity or use a flow reactor for better illumination [21]- Screen more stable catalysts (e.g., acridinium salts) [22] |

| Difficulty in Reproducibility | - Inconsistent temperature control [21]- Variations in light source output or positioning | - Use a temperature-controlled photoreactor (e.g., PhotoRedOx Box TC) [21]- Calibrate light source regularly and standardize reactor geometry |

Troubleshooting Guide for Reductive Dehalogenation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Dehalogenation | - Insufficient hydrogen atom donor [25]- Quenching of radical intermediates by oxygen [22] | - Increase concentration of Hantzsch ester or formate donor [25]- Ensure rigorous degassing of reaction mixture with inert gas |

| Low Functional Group Tolerance | - Over-reduction of other sensitive motifs | - Tune reducing power by switching photocatalyst (e.g., from Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ to Ir(ppy)₃) [24]- Lower catalyst loading (can be as low as 0.05 mol%) [25] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of using photoredox catalysis for C-H functionalization over traditional methods?

Photoredox catalysis offers several key advantages for C-H functionalization. It enables the generation of highly reactive radical intermediates under exceptionally mild conditions (often at room temperature), bypassing the need for strong oxidants or high temperatures [24]. This results in improved functional group tolerance and the ability to selectively target specific C-H bonds through proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) or hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) processes [24]. Furthermore, it provides access to unique reaction pathways that are difficult to achieve with conventional two-electron chemistry.

FAQ 2: My dehydrogenative lactonization gives a mixture of regioisomers with substituted substrates. How can I improve selectivity?

For the lactonization of 3′-substituted biphenyl-2-carboxylic acids, which presents a regioselectivity challenge, the choice of methodology can be critical. While both photoredox and electrochemical approaches can achieve good yields, the photoredox-catalyzed strategy has been shown to offer superior regioselectivity (ranging from 80:20 to 96:4) compared to some electrochemical and other radical lactonization methods [23]. Fine-tuning the steric and electronic properties of the photocatalyst and the solvent system can further enhance selectivity.

FAQ 3: What is the most common mistake when setting up a photoredox reaction for the first time?

A common oversight is the use of an inappropriate light source or reaction vessel. The light source must emit at a wavelength that overlaps significantly with the absorption profile of the photocatalyst [21]. Furthermore, the reactor must be designed to allow for efficient photon penetration; for scale-up, moving from a batch reactor to a continuous flow system, where the reaction mixture is passed through a thin, illuminated tube, can dramatically improve efficiency and reproducibility [21] [26].

FAQ 4: Why is the choice of terminal oxidant so important in photocatalytic "oxidase" reactions?

In oxidase-type reactions, the terminal oxidant is responsible for turning over the photocatalyst but does not become incorporated into the product. The choice is critical because many common oxidants can quench the excited state of the photocatalyst or react unproductively with the radical intermediates, leading to decomposition or side reactions [22]. For example, while molecular oxygen is an ideal "green" oxidant, it can quench photocatalyst excited states and generate superoxide, which decomposes sensitive substrates [22]. Persulfate salts are potent alternatives but often require solvent systems that can dissolve them [22].

FAQ 5: Can photoredox catalysts be recycled to improve sustainability and cost-efficiency?

Yes, this is an active area of innovation. A key strategy involves the immobilization of homogeneous photocatalysts onto insoluble polymers or surfaces [26]. These heterogeneous catalysts can be used to coat the inside of tubes in flow reactors, allowing the catalyst to be used and reused without contaminating the product. This approach combines the precise tunability of homogeneous catalysts with the recyclability and durability of heterogeneous systems [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Dehydrogenative Lactonization via Photoredox Catalysis

This protocol is adapted from methods for the cyclization of 2-arylbenzoic acids to benzocoumarins [23].

- Reaction Setup: In a dry vial, combine the 2-arylbenzoic acid substrate (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 9-mesityl-10-methylacridinium (Acr-Mes⁺) catalyst (2 mol%), and sodium persulfate (Na₂S₂O₈, 2.0 equiv). Seal the vial with a septum.

- Solvent System: Add a 4:1 mixture of acetonitrile and trifluoroethanol (TFE) (2 mL total volume) to the vial [23].

- Deoxygenation: Purge the reaction mixture with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10 minutes.

- Irradiation: Place the vial in a LucentBLUE or similar photoreactor equipped with 450 nm blue LEDs. Irradiate the mixture for 16-24 hours with stirring [21].

- Work-up: After completion, concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure. Purify the crude residue by flash column chromatography to isolate the lactone product.

Protocol 2: Tin-Free Reductive Dehalogenation

This protocol is based on the seminal work for the reduction of activated C-X bonds [25].

- Reaction Setup: In a Schlenk flask, charge the alkyl halide substrate (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ (0.05-1.0 mol%), and Hantzsch ester (1.5 equiv) or formic acid (HCO₂H) with diisopropylethylamine (i-Pr₂NEt, 2.0 equiv) as the hydrogen atom donor system [25].

- Solvent: Add degassed acetonitrile (4 mL) as the solvent.

- Deoxygenation: Freeze-pump-thaw the reaction mixture or sparge with argon for 15 minutes.

- Irradiation: Irradiate the reaction with a 450 nm blue LED lamp while stirring at room temperature for 4-12 hours.

- Work-up: Directly concentrate the reaction mixture and purify the product by flash chromatography.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Dehydrogenative Lactonization [23]

| Substrate Class | Photoredox Catalysis Yield (Range) | Electrochemical Yield (Range) | Key Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-arylbenzoic acids | Good to High Yields | Good to High Yields | Both methods are efficient. |

| 3′-substituted acids | Good yields, High Regioselectivity (80:20 to 96:4) | Good yields, Lower Regioselectivity | Photoredox offers superior control. |

| 2-Benzylbenzoic acids | -- | Exclusive formation of phenyl phthalides | Electrochemical method showcases C(sp³)-H lactonization. |

Table 2: Representative Reagents for Reductive Dehalogenation [25]

| Reagent | Function | Typical Loading (equiv) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ | Photoredox Catalyst | 0.0005 - 0.01 | Converts light energy to chemical potential; highly tunable. |

| Hantzsch Ester | Hydrogen Atom Donor | 1.5 - 2.0 | Bench-stable, reduces radical intermediate. |

| HCO₂H / i-Pr₂NEt | Alternative H-Donor System | 2.0 / 2.0 | Effective, cost-efficient alternative donor system. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Photoredox HTE

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example Use-Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Photoredox Catalysts | Absorbs light to initiate single-electron transfer (SET); choice dictates redox window [21]. | - Ru(bpy)₃²⁺: General-purpose reductant [25].- Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy))PF₆: Strong oxidant in excited state.- Acr-Mes⁺: Very oxidizing organocatalyst for lactonization [23]. |

| Terminal Oxidants | Regenerates the ground-state photocatalyst in oxidation reactions [22]. | - Persulfates (S₂O₈²⁻): For strong oxidizing conditions [23] [22].- O₂: "Green" oxidant, but can cause decomposition [22]. |

| Terminal Reductants | Regenerates the ground-state photocatalyst in reduction reactions. | - i-Pr₂NEt: Common sacrificial amine reductant [25].- Hantzsch Ester: Serves as both reductant and H-atom donor [25]. |

| Hydrogen Atom Donors (HAT) | Quenches carbon-centered radicals to form C-H bonds. | HCO₂H/i-Pr₂NEt or Hantzsch Ester for reductive dehalogenation [25]. |

| Specialized Solvents | Medium that dissolves reagents and is transparent to reaction wavelength. | Acetonitrile (MeCN), Trifluoroethanol (TFE), Dimethylformamide (DMF) [23]. |

| LED Photoreactors | Provides controlled, monochromatic light to power the reaction [21]. | LucentBLUE (450 nm), PhotoRedOx Box TC (temperature-controlled) [21]. |

Experimental Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Photoredox Dehalogenation Mechanism

Photoredox Lactonization Mechanism

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Photoredox Reaction Optimization

This technical support center addresses common challenges faced by researchers when scaling and intensifying photoredox reactions from high-throughput experimentation (HTE) to continuous flow production. The guidance is framed within a broader thesis on optimizing photoredox processes for industrial application.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my reaction efficiency drop significantly when I intensify the process by increasing light intensity?

This is a common phenomenon where the system shifts from being photon-limited at low light intensities to being kinetically-limited at high intensities [27]. At low light levels, reaction rate increases linearly with light intensity. Beyond a critical point, the flux of photogenerated charges at the catalyst surface exceeds the rate at which surface catalysis, mass transfer, or adsorption/desorption steps can process them [27]. This leads to increased charge carrier recombination and diminished returns. Strategies to counter this include optimizing temperature to enhance surface reaction rates and ensuring efficient mass transfer through reactor design [27].

2. What are the key advantages of continuous flow reactors over batch systems for photoredox scale-up?

Flow reactors address several fundamental limitations of batch photochemistry. Their high surface-area-to-volume ratio ensures uniform irradiation of the entire reaction mixture, overcoming the photon transport attenuation effect (Beer-Lambert law) that plagues large batch vessels [28] [17]. They provide superior control over reaction parameters, leading to enhanced reproducibility, more efficient irradiation, shorter reaction times, and easier scale-up without changing reaction parameters [28] [29]. They also enable safer handling of reactive intermediates.

3. How can I maintain temperature control in intensified photoredox processes, and why is it critical?

Temperature control is often overlooked in photochemistry. While reactions are photon-initiated, the subsequent surface catalytic steps are thermally activated [27]. Precise temperature control, achievable in advanced modular photoreactors (from -20°C to +80°C), is vital for reproducibility and for facilitating the surface reaction steps that become rate-limiting under high-intensity light [27] [30]. This ensures consistent performance across scales and different reactor formats (e.g., from parallel HTE plates to flow systems) [30].

4. My heterogeneous photocatalytic reaction is slow. Should I focus on developing a new catalyst material?

Not necessarily. Before synthesizing new catalysts, investigate the reaction engineering aspects. A catalyst proven efficient for one reaction (e.g., Aeroxide P25 for nitrobenzene reduction) can be inefficient for another, indicating that the bottleneck is often not the bulk catalyst properties but the nature of the surface reaction itself [27]. Focus on optimizing mass transfer, temperature, and substrate-catalyst interaction before exploring new catalyst synthesis.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Reaction Yields Between Small and Large Scale Batches

- Potential Cause: Inefficient and non-uniform irradiation in the larger batch reactor due to the exponential decay of light intensity as it penetrates the reaction mixture [28].

- Solution: Transition to a continuous flow microreactor. The short optical path length in microchannels ensures uniform photon flux throughout the reaction volume [17] [29].

- Protocol:

- Transfer your optimized batch reaction to an FEP or PFA tubular flow reactor (ID < 1 mm).

- Use a syringe or HPLC pump to deliver the reaction mixture.

- Place the reactor tube in close proximity to high-power LEDs.

- Calibrate the residence time (

tR) to achieve full conversion. The significantly shortertRin flow often leads to a direct increase in hourly productivity [29].

Problem: Catalyst Deactivation or Reactor Blockage with Heterogeneous Photocatalysts in Flow

- Potential Cause: Physical instability of the solid catalyst or poor reactor design for solid-liquid systems.

- Solution: Immobilize the heterogeneous catalyst within the flow reactor [17].

- Protocol (Catalyst Immobilization):

- Select a support (e.g., glass beads, glass fibers).

- Prepare a stable suspension of your catalyst (e.g., polymeric carbon nitride - PCN).

- Functionalize the support by coating it with the catalyst suspension, using a minimal binder if required.

- Pack the coated beads into a column or wrap the coated fibers to create a fixed-bed flow photoreactor.

- This setup prevents blockage, eliminates catalyst separation steps, and ensures consistent catalyst loading for scale-up [17].

Problem: Formation of Undesired By-products During Scale-Up

- Potential Cause: Over-irradiation of the reaction mixture in certain zones of the reactor or prolonged reaction times in batch.

- Solution: Utilize the precise residence time control offered by flow chemistry. Once the reaction is complete, the mixture is immediately removed from the light source, preventing secondary reactions [28] [17].

- Protocol:

- In your flow system, determine the minimum residence time required for >95% conversion of the starting material.

- Set the flow rate precisely to maintain this residence time.

- This approach is superior to batch methods where the entire volume is irradiated for the duration of the slowest molecule's reaction.

Quantitative Data for Process Intensification

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Batch vs. Flow Photoredox Reactors [29]

| Reaction Type | Batch Yield (%) / Time | Flow Yield (%) / Time | Throughput Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azide Reduction (1 -> 2) | 70% / 6 h | 89% / 0.5 h | 12-fold |

| Reductive Ring Opening (3 -> 4) | 90% / 4 h | 90% / 10 min | 24-fold |

| Iminium Ion Generation (15 -> 16) | ~90% / 18 h | ~90% / 30 s | ~70-fold (mmol/h) |

Table 2: Impact of Temperature on Photocatalytic Reaction Rates [27]

| Photocatalytic Reaction | Temperature Increase | Effect on Reaction Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrobenzene Reduction | 15°C to 65°C | ~50% more efficient |

| Oxygen Reduction | 15°C to 65°C | 3x increase |

| Water Splitting | Room Temp to 270°C | Quantum Yield >80% achieved |

| Ethylene Oxidation | 60°C to 160°C | More than doubled |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Heterogeneous Photoredox Flow Chemistry

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Carbon Nitride (PCN) | Metal-free, stable heterogeneous photocatalyst | Prepared from urea (UCN), thiourea (TCN), or melamine (MCN). UCN often shows highest efficiency due to better charge separation [17]. |

| FEP/PFA Tubing | Material for flow reactor construction | Chemically inert, flexible, and highly transparent to visible light [29]. |

| High-Power LED Arrays | Light source for photoexcitation | Provide high-intensity, cool, and monochromatic light. Enable precise control over light intensity [27]. |

| Glass Beads/Fibers | Support for catalyst immobilization | Provide high surface area for catalyst coating within a flow reactor, creating a fixed-bed photocatalytic system [17]. |

| Ru(bpy)₃Cl₂ / Ir(ppy)₃ | Homogeneous photoredox catalysts | Common metal-based catalysts for a wide range of transformations. Used in early-stage reaction discovery and HTE [28] [29]. |

| Syringe/HPLC Pumps | Precise fluid delivery in flow systems | Allow accurate control over residence time, a critical parameter in flow chemistry [29]. |

Experimental Workflow and System Diagnostics

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving efficiency losses in photoredox catalysis, guiding you from problem identification to solution.

The diagram below outlines the decision process for selecting the appropriate reactor configuration based on the stage of research and project goals.

Solving Common Challenges: Quenching, Deactivation, and Performance Optimization

Diagnosing and Overcoming Reaction Quenching and Catalyst Deactivation

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Reaction Quenching in Photoredox Catalysis

What is Reaction Quenching? Reaction quenching refers to any process that decreases the fluorescent intensity of a substance or interferes with the conversion of decay energy to photons, thereby reducing the efficiency of photochemical reactions [31] [32]. In the context of high-throughput experimentation (HTE) for photoredox reactions, quenching can significantly diminish reaction yields and lead to false negative results during screening.

Key Questions for Diagnosis:

- Has your reaction yield dropped suddenly despite previously optimized conditions?

- Are you observing inconsistent results across different wells in your HTE plate?

- Have you recently changed your solvent system or added new reagents?

Diagnostic Table for Reaction Quenching:

| Type of Quench | Key Characteristics | Common Sources in Photoredox | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Quench | Reduces photon production by absorbing nuclear decay energy [31] | Inappropriate solvents, dissolved oxygen, amine additives [31] [32] | Decreased count rate (CPM), reduced maximum pulse height [31] |

| Color Quench | Absorbs photons of light before detection [31] | Colored substrates, reaction byproducts, metallic salts [31] | Visible color in samples, reduced light penetration [31] |

| Collisional Quench | Excited fluorophore experiences contact with quencher [32] | Molecular oxygen, iodide ions, acrylamide [32] | Fluorescence intensity loss, lifetime changes [32] |

| Static Quench | Non-fluorescent complex formation in ground state [32] | Dye aggregation, π-stacking interactions [32] [33] | Unique absorption spectrum, nonfluorescent complexes [32] |

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies:

For Chemical Quenching:

- Replace highly quenching solvents (e.g., chloroform) with less quenching alternatives (e.g., dichloromethane) [31]

- Degas solutions to remove dissolved oxygen, a known chemical quencher [31]

- Optimize cocktail volume or decrease sample volume [31]

- Consider bleaching colored samples with hydrogen peroxide prior to adding cocktail [31]

For Color Quenching:

For Collisional and Static Quenching:

Preventive Measures for HTE Platforms: When using HTE platforms like the FLOSIM system for photoredox reaction optimization, ensure uniform photon dispersion across the platform and maintain temperature control through air convection methods [8]. The use of a glass 96-well plate allows complete penetration and reflection of light in all directions, minimizing quenching variations between wells [8].

Guide 2: Addressing Catalyst Deactivation in High-Throughput Experimentation

What is Catalyst Deactivation? Catalyst deactivation is the loss of catalytic activity and/or selectivity over time, which poses significant challenges in industrial catalytic processes [34] [35]. In HTE for photoredox reactions, understanding and mitigating deactivation is crucial for developing robust and scalable processes.

Key Questions for Diagnosis:

- Is your catalyst showing decreased activity despite initial high performance?

- Are you observing changes in product selectivity over time?

- Have you introduced new substrate sources or impurities into your system?

Diagnostic Table for Catalyst Deactivation:

| Deactivation Type | Primary Causes | Impact on Photoredox Catalysis | Common in Biomass Feedstocks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisoning | Strong chemisorption of impurities on active sites [34] [35] | H₂S, Pb, Hg, S, P can poison primary reformer and low shift catalysts [34] | Sulfur compounds, chlorine species, nitrogen compounds [35] [36] |

| Coking/Fouling | Deposition of carbonaceous species blocking active sites [34] [35] | Pore blockage, especially at high temps, low pressures, low H₂/CO ratios [35] | Alkali metals (e.g., potassium), AAEMs [35] [36] |

| Sintering | Thermal degradation diminishing active surface area [34] [35] | Loss of active surface due to high reaction temperature [35] | - |

| Attrition | Mechanical damage in slurry- and fluidized-bed reactors [35] | Catalyst particle breakdown [35] | - |

| Water Damage | Structural damage to catalyst support [36] | Acceleration of sintering, support degradation [35] [36] | High water content in biomass feeds [36] |

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies:

For Catalyst Poisoning:

- Implement guard beds (e.g., ZnO for sulfur removal) or pre-treatment processes [34]

- Remove sulfur sources to below 0.2 ppm for Fe-based catalysts and <0.1 ppm for Co-based catalysts [35]

- Consider reversible vs. irreversible poisoning; some poisons can be removed by increasing temperature or chemical treatment [34]

For Coking/Fouling:

For Sintering and Thermal Degradation:

For Water-Induced Deactivation:

HTE-Specific Considerations: When using HTE platforms for photoredox catalyst screening, consider extended-duration experiments to evaluate catalysts after their initial "break-in" period [36]. Study catalyst deactivation under kinetically-controlled conditions and develop accelerated catalyst aging processes to simulate long-term deactivation, saving both time and resources during optimization [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common chemical quenchers I should avoid in photoredox reaction screening? The most common chemical quenchers include molecular oxygen, iodide ions, and acrylamide [32]. In solvent systems, the sequence of chemical quench strength from strongest to mildest is: nitro groups (e.g., nitromethane) > sulfides (e.g., diethyl sulfide) > halides (e.g., chloroform) > amines (e.g., 2-methoxyethylamine) > ketones (e.g., acetone) > aldehydes > organic acids > esters > water > alcohols > ethers > other hydrocarbons (e.g., hexane) [31]. When designing HTE screens, carefully select solvents low on this quenching scale to maximize photon penetration and reaction efficiency.

Q2: How do I determine if my catalyst is being poisoned versus other forms of deactivation? Catalyst poisoning typically involves strong chemical interaction of feed components with active sites and is often specific to certain catalyst materials [34]. Key indicators include:

- Sudden activity drop rather than gradual decline

- Correlation with introduction of new feedstock batches

- Presence of known poisons (S, P, As, Hg, Pb) in feedstream [34]

- Specificity to certain catalyst types (e.g., sulfur poisoning of nickel catalysts) [34]

Contrast this with coking, which usually shows more gradual deactivation and may be influenced by temperature and H₂ pressure, or sintering, which is typically temperature-dependent and causes permanent loss of active surface area [35]. Advanced characterization techniques like in situ spectroscopy can provide definitive identification of poisoning mechanisms.

Q3: What are the key amino acids that quench fluorescence, and how can I mitigate their effects? Four amino acids effectively quench Alexa Fluor dyes: Tryptophan (Trp), Tyrosine (Tyr), Histidine (His), and Methionine (Met) [33]. The quenching mechanisms involve photoinduced electron transfer (PET) with a combination of static and dynamic components [33]. To mitigate:

- Select labeling sites distant from these amino acids in protein engineering

- Add spacers (short saturated carbon chains) between fluorophore and attachment site

- For Trp and His, note that static quenching occurs through stacking interactions, so positional considerations are crucial [33]

- Consider that approximately half of total quenching by Trp arises from static mechanisms [33]

Q4: How can I design better HTE experiments to account for potential quenching and deactivation? Implement these strategies for more robust HTE design:

- Path-length matching: Vary volume in wells to match internal diameter of flow system tubing for better light penetration [8]

- Light source uniformity: Ensure consistent photon dispersion across all wells using concave lenses and reflection mirrors [8]

- Temperature control: Maintain uniform temperature through air convection methods [8]

- Accelerated aging: Include extended-duration experiments or stressed conditions to probe deactivation early [36]

- Material compatibility: Avoid heterogeneous conditions that might clog systems or introduce quenching [8]

- Parallel poisoning studies: Include intentional poison spikes in subset of wells to assess tolerance [36]

Q5: Are there specific strategies to mitigate water-induced deactivation in biomass-derived photoredox reactions? Yes, water-induced deactivation can be addressed through multiple approaches:

- For sulfide catalysts, maintain H₂S/H₂O partial pressure ratio > 0.025 to prevent S-O exchange at MoS₂ edges [35]

- 100% Co promotion at S-edge can inhibit S-O exchange across wider H₂S/H₂O ranges [35]

- For oxide catalysts, carefully control H₂/H₂O ratio as they can only be exposed to low H₂ pressures to avoid reduction [35]

- Consider that phosphides operated at low H₂ pressures are oxidized by water and lose activity [35]

- Develop water-tolerant catalyst systems or implement dehydration pre-treatment steps for wet feedstocks [36]