Organic Molecule Structure Determination: From Classical Spectroscopy to AI-Driven Techniques

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the techniques used for determining the structure of organic molecules, a critical process in drug discovery and materials science.

Organic Molecule Structure Determination: From Classical Spectroscopy to AI-Driven Techniques

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the techniques used for determining the structure of organic molecules, a critical process in drug discovery and materials science. It covers foundational spectroscopic methods like NMR and IR, explores advanced applications of scanning probe microscopy and powder XRD, addresses troubleshooting for complex natural products and nanocrystalline materials, and evaluates the growing role of machine learning and computational validation. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this review synthesizes established and emerging methodologies to guide the selection and optimization of structure elucidation strategies.

Core Principles and Classical Spectroscopic Techniques for Organic Structure Elucidation

The determination of a molecule's precise structure represents a cornerstone of modern scientific research, particularly in the field of drug development. For researchers and scientists, this process is a multi-stage endeavor that begins with the crude biological source and culminates in a definitive molecular formula and three-dimensional configuration. This technical guide delineates the fundamental workflow for organic molecules, focusing on the critical pathway from isolation and purification through to final structural elucidation. The integrity of every subsequent analytical step is contingent upon the initial purity and stability of the isolated molecule, making the early stages of this workflow paramount to success [1]. Within the broader context of organic molecule structure determination techniques, this document provides a comprehensive framework, integrating detailed methodologies, essential tools, and advanced analytical protocols to guide research and development efforts.

Core Workflow: From Crude Sample to Molecular Formula

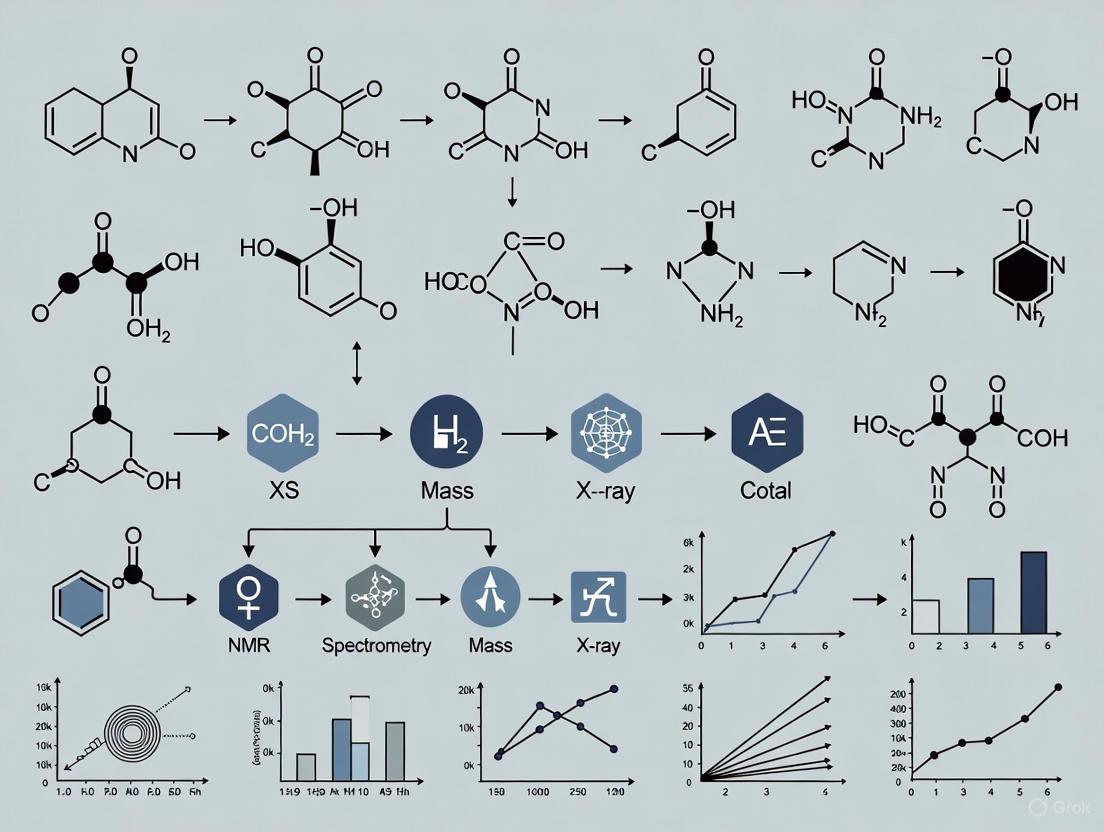

The journey to determining a molecular formula is a systematic, multi-phase process. Each stage is designed to progressively transform a complex crude mixture into a pure compound, followed by rigorous analysis to reveal its identity. The following diagram illustrates this integrated pathway, highlighting the key objectives and outputs at each stage.

Phase 1: Isolation and Purification

The initial phase focuses on extracting the target molecule from its native environment and separating it from contaminants. This involves a series of techniques selected based on the source material and the properties of the target molecule.

2.1.1 Sample Sourcing and Extraction Proteins can be isolated from native tissues or produced recombinantly using genetically engineered systems in bacteria (e.g., E. coli), yeast, insect, or mammalian cells (e.g., Expi293, ExpiCHO, ExpiSf systems) to achieve high yields [2] [3]. The primary goal of extraction is to break open cells and release their contents. Table 1 summarizes the common extraction methods.

Table 1: Protein Extraction Methods

| Method | Principle | Common Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Homogenization [3] | Applies shear force to disrupt cells. | Tough plant and animal tissues. | Scalable but may generate heat. |

| Sonication [3] | Uses ultrasonic waves to disrupt cell membranes. | Bacterial cells, small volumes. | Requires cooling to prevent denaturation. |

| Detergent-Based Lysis [2] [3] | Solubilizes cell membranes by disrupting lipid bilayers. | Total protein extraction; especially effective for membrane proteins. | Risk of protein denaturation at high concentrations. |

| Enzymatic Treatment [3] | Uses enzymes (e.g., lysozyme) to break down cell walls. | Bacterial cells. | Specific and gentle; often requires a complementary method. |

| Chaotropic Agents [1] [3] | Disrupts hydrogen bonding to solubilize proteins. | Insoluble proteins (e.g., inclusion bodies). | Often denatures proteins, requiring refolding. |

During and after extraction, protein stability is critical. The use of protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails is essential to prevent enzymatic degradation and preserve post-translational modifications [2].

2.1.2 Purification Techniques Following extraction, purification techniques are employed to isolate the target molecule. Chromatography is the most powerful and versatile set of methods for this purpose.

- Affinity Chromatography: This is often the first and most powerful step, especially for recombinant proteins with engineered tags (e.g., His-tag). It exploits specific interactions between the target protein and a ligand immobilized on a resin. The target protein binds selectively and is later eluted under specific conditions [2] [3].

- Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX): Separates proteins based on their net charge. Proteins bind to oppositely charged resin and are eluted by increasing the ionic strength of the buffer. It is highly effective for further refining purity after an initial capture step [2] [3].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Also known as gel filtration, SEC separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic size and shape. It is typically used as a final "polishing" step to remove aggregates and exchange the buffer [2] [3].

Other techniques like precipitation (e.g., using ammonium sulfate or organic solvents) and ultrafiltration are frequently used for concentration and initial crude fractionation [1] [3].

Phase 2: Characterization and Purity Assessment

Before proceeding to structural analysis, it is imperative to confirm the purity and integrity of the isolated molecule. A combination of techniques provides a comprehensive assessment.

- Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE): Used to assess protein purity, homogeneity, and approximate molecular weight. A single band on a gel after Coomassie or silver staining indicates a high degree of purity [3].

- Spectroscopic Quantitation: Methods like UV-Vis spectroscopy are used to determine protein concentration accurately (e.g., using the Pierce BCA Assay) and can provide information on cofactors or contaminants [2] [3].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Provides an exact molecular mass of the protein or peptide, which is a critical parameter for confirmation and identification. It is highly sensitive and can detect minor impurities or post-translational modifications [1] [3].

Phase 3: Structure Determination and Molecular Formula

With a pure and characterized molecule, the final phase is to determine its three-dimensional structure. For natural products and small organic molecules, this often involves crystallography, while for proteins, both crystallography and other biophysical methods are employed.

2.3.1 Crystallography for Absolute Configuration Crystallographic analysis is the most reliable method for elucidating the absolute configuration of natural products and small molecules, providing precise spatial arrangement information at the atomic level [4]. The traditional requirement for high-quality single crystals has been a major hurdle. Recent advancements have introduced innovative strategies to overcome this:

- Crystalline Sponge Method: Involves orienting target molecules within pre-prepared porous crystals, eliminating the need to grow crystals of the target itself [4].

- Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED): Allows for structure determination from nanocrystals that are too small for conventional X-ray diffraction, using an electron microscope [4].

2.3.2 Integrated Workflow for Protein Structure Determination For proteins, the structure determination pipeline is computationally intensive. A recent demonstration involves an Evolutionary Algorithm (EA) informed by Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP). This approach searches vast organic chemical spaces for molecules with desired solid-state properties by predicting their most stable crystal structures and evaluating properties like charge carrier mobility directly from the predicted packing [5]. This method outperforms searches based on molecular properties alone.

2.3.3 Deriving the Molecular Formula The molecular formula is a definitive output of this phase. For small molecules, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) provides the exact mass, from which the molecular formula can be deduced with high confidence. For novel compounds, this data is combined with elemental analysis and the atomic coordinates obtained from X-ray crystallography to unambiguously confirm the molecular formula.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the isolation-to-structure workflow requires a suite of reliable reagents and kits. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Isolation and Purification

| Product/Reagent Name | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Expi293/ExpiCHO Expression System [2] | High-yield transient recombinant protein expression in mammalian cells. | Chemically defined medium; yields up to 3 g/L; adapted for suspension culture. |

| M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent [2] | Total protein extraction from mammalian cells. | Gentle, detergent-based; eliminates need for mechanical disruption; preserves protein activity. |

| Mem-PER Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit [2] | Selective enrichment of membrane proteins from cells and tissues. | Provides improved yield of integral membrane proteins compared to other kits. |

| Pierce Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Tablets [2] | Prevention of protein degradation and dephosphorylation during extraction. | Ready-to-use, broad-spectrum formulations; EDTA-free options available. |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit [2] | Colorimetric quantification of protein concentration. | Compatible with samples containing detergents; highly sensitive. |

| Surfact-Amps Detergent Solutions [2] | Highly purified detergents for cell lysis and protein solubilization. | Precisely diluted (10%); exceptionally pure with low peroxides and carbonyls. |

Advanced Technical Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Purification of a Recombinant His-Tagged Protein

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for purifying a recombinant protein expressed in E. coli using Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC).

Materials:

- Cell pellet from induced culture.

- Lysis Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, protease inhibitors).

- IMAC Resin (e.g., Ni-NTA Agarose).

- Wash Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20-50 mM imidazole).

- Elution Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 250-500 mM imidazole).

- Dialysis Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl).

Method:

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in Lysis Buffer. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Lyse cells by sonication on ice (e.g., 3-5 cycles of 30 seconds pulse, 30 seconds rest). Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at >14,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Retain the supernatant [2] [3].

- Chromatography: Equilibrate the IMAC resin with Lysis Buffer. Incubate the clarified lysate with the resin for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle mixing. Load the mixture into a column and allow the flow-through to collect.

- Washing: Wash the resin with 10-15 column volumes of Wash Buffer to remove weakly bound contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the bound His-tagged protein with 5-10 column volumes of Elution Buffer. Collect the eluate in small fractions.

- Buffer Exchange and Polishing: Analyze fractions by SDS-PAGE. Pool fractions containing the pure target protein. Dialyze against Dialysis Buffer or perform a buffer exchange using a desalting column (SEC) to remove imidazole [2] [3]. Concentrate the protein using a centrifugal concentrator with an appropriate molecular weight cutoff.

Detailed Protocol: Crystal Structure Prediction-Informed Evolutionary Algorithm

This protocol describes the computational search for organic molecules with optimal solid-state properties, as demonstrated for organic semiconductors [5].

Objective: To identify molecules with high charge carrier mobility by evaluating their predicted crystal structures.

Workflow:

- Initialization: Define a search space of possible organic molecules and generate an initial population.

- Fitness Evaluation: a. Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP): For each candidate molecule, perform an automated CSP search. A cost-effective scheme may involve generating 500-2000 trial crystal structures in each of the 5-10 most common space groups (e.g., P1, P2₁, P2₁2₁2₁, P2₁/c, C2/c) [5]. b. Property Calculation: For the low-energy predicted crystal structures (e.g., within 7 kJ/mol of the global minimum), calculate the target property—in this case, the electron mobility based on the transfer integrals and reorganization energies derived from the crystal packing [5]. c. Assign Fitness: Assign a fitness score to the molecule based on the highest (or landscape-averaged) predicted mobility from its stable crystal structures.

- Evolution: Select the fittest molecules as "parents." Generate a new "child" generation through crossover (combining molecular fragments from parents) and mutation (introducing random chemical modifications).

- Iteration: Repeat the fitness evaluation and selection process for multiple generations until convergence is achieved, i.e., no significant improvement in the maximum fitness is observed.

Key Consideration: This method's efficacy relies on a balance between computational cost and the completeness of the CSP search. Biased sampling towards frequently observed space groups can recover over 70% of low-energy structures at a fraction of the cost of a comprehensive search [5].

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy remains a cornerstone technique for organic molecule structure determination, prized for its rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and non-destructive nature. The technique identifies functional groups by measuring the absorption of infrared radiation by molecular vibrations, providing a characteristic spectral fingerprint. While nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (MS) have become predominant for complete structure elucidation, IR spectroscopy maintains critical advantages for specific applications, including minimal sample preparation, low operational costs, and rapid measurement times that enable high-throughput analysis [6] [7]. This technical guide examines both traditional interpretation methods and emerging artificial intelligence (AI) approaches that are revolutionizing spectroscopic analysis for researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of IR Spectroscopy

IR spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb specific frequencies of infrared radiation corresponding to the natural vibrational frequencies of their chemical bonds. When the frequency of IR radiation matches the vibrational frequency of a bond, absorption occurs, resulting in characteristic peaks in the IR spectrum.

The spectrum is typically divided into two primary regions. The functional group region (4000-1500 cm⁻¹) contains absorptions from stretching vibrations of key functional groups like O-H, C=O, and C-H bonds. The fingerprint region (1500-500 cm⁻¹) presents a complex pattern resulting from a combination of stretching and bending vibrations that is unique to each molecule, much like a human fingerprint [8]. This region is particularly valuable for confirming a compound's identity by comparison to reference spectra.

The intensity and shape of absorption bands provide additional structural information. Intensity depends primarily on bond polarity, with more polar bonds producing stronger absorptions. Shape characteristics—whether a peak is broad or sharp—can indicate specific bonding environments, such as the broad hydrogen-bonded O-H stretches of alcohols and carboxylic acids [8].

Characteristic IR Absorptions of Major Functional Groups

Structured Reference Table of Key IR Frequencies

Table 1: Characteristic IR Absorption Frequencies of Common Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Bond/Vibration Type | Frequency Range (cm⁻¹) | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol, Phenol | O-H stretch | 3200-3600 | Broad, medium-strong |

| Carboxylic Acid | O-H stretch | 2500-3300 | Very broad |

| Amine, Amide | N-H stretch | 3300-3500 | Medium, sharp |

| Terminal Alkyne | ≡C-H stretch | 3250-3350 | Strong, sharp |

| Alkene/Aromatic | =C-H stretch | 3000-3100 | Medium |

| Alkane | C-H stretch | 2850-2950 | Medium-strong |

| Aldehyde | C-H stretch | 2700-2800 (doublet) | Weak |

| Carbonyl (general) | C=O stretch | 1650-1750 | Very strong |

| Ketone | C=O stretch | 1705-1725 | Very strong |

| Aldehyde | C=O stretch | 1720-1740 | Very strong |

| Ester | C=O stretch | 1730-1750 | Very strong |

| Carboxylic Acid | C=O stretch | 1700-1725 | Very strong |

| Amide | C=O stretch | 1640-1670 | Strong |

| Nitrile | C≡N stretch | 2240-2260 | Medium |

| Alkyne | C≡C stretch | 2100-2260 | Weak (strong for terminal) |

| Alkene | C=C stretch | 1620-1680 | Variable |

| Aromatic | C=C stretch | 1475-1600 (multiple) | Variable |

| Alcohol, Ether, Ester | C-O stretch | 1000-1300 | Strong |

Compiled from multiple spectroscopic references [9] [10] [11]

Strategic Interpretation of IR Spectra

Effective IR spectrum analysis requires a strategic approach rather than attempting to assign every absorption band. The "tongue and sword" method provides a prioritized framework, focusing first on two critical regions: the hydroxyl region (3200-3600 cm⁻¹) for broad "tongue-like" O-H stretches, and the carbonyl region (1630-1800 cm⁻¹) for sharp "sword-like" C=O stretches [12].

Additional diagnostic regions include the 3000 cm⁻¹ dividing line between alkene/aromatic C-H stretches (above 3000 cm⁻¹) and alkane C-H stretches (below 3000 cm⁻¹), and the triple-bond region (2050-2250 cm⁻¹) for nitriles and alkynes [12]. This prioritized approach enables rapid functional group identification before delving into finer structural details.

Experimental Protocols for IR Spectrum Acquisition

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Table 2: Standard IR Sample Preparation Techniques

| Technique | Application Scope | Protocol Details | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| KBr Pellet | Solid powders | 1-2 mg sample mixed with 100-200 mg dry KBr; pressed under vacuum at 10,000-15,000 psi | Excellent spectral quality; hygroscopic KBr requires drying |

| Solution Cell | Liquid samples, solutions | Pathlength 0.1-1.0 mm; NaCl or KBr windows; typical concentration 1-10% | Quantitative analysis possible; solvent absorption may interfere |

| ATR-FTIR | Solids, liquids, pastes | Sample placed on crystal (diamond, ZnSe); pressure applied for contact | Minimal preparation; non-destructive; surface analysis only |

| Thin Film | Non-volatile liquids | Sample squeezed between two salt plates | Rapid analysis; suitable for qualitative identification |

| Gas Cell | Volatile compounds | Sealed cell with pathlength 5-20 cm; NaCl or KBr windows | Requires specialized equipment; quantitative vapor analysis |

Instrument Operation and Data Collection

Modern Fourier Transform IR (FTIR) spectrometers have standardized IR analysis, but proper operational protocols remain essential for reproducible results:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform daily validation using polystyrene reference film, verifying key absorption peaks at 1601 cm⁻¹, 2850 cm⁻¹, and 3026 cm⁻¹ [10].

- Background Collection: Collect background spectrum with pure solvent or empty ATR crystal under identical analytical conditions.

- Parameter Optimization: Set resolution to 4 cm⁻¹ for most applications; 8 cm⁻¹ for qualitative screening; accumulate 16-64 scans depending on signal-to-noise requirements [13].

- Quality Assessment: Verify absorption bands are within linear response range (transmittance 15-85%); check for saturation effects in key diagnostic regions.

- Data Processing: Apply baseline correction when necessary; avoid over-processing that may distort spectral features.

Advanced AI-Driven Approaches to IR Spectral Interpretation

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications

Traditional interpretation of IR spectra has been limited to identifying a select few functional groups, leaving much of the information in the fingerprint region underutilized. Recent advances in machine learning are overcoming these limitations through several approaches:

Functional Group Classification: Neural networks can now identify 17 or more functional groups simultaneously from IR spectra alone, achieving F1 scores above 0.7 [13]. These models learn spectral features directly from data rather than relying on handcrafted rules, improving accuracy and reproducibility.

Complete Structure Elucidation: Transformer-based models represent the cutting edge in IR analysis, directly predicting molecular structures from IR spectra. These sequence-to-sequence models use both the chemical formula and IR spectrum as input to generate the molecular structure in SMILES notation [6]. Recent architectures employing patch-based representations similar to Vision Transformers preserve fine-grained spectral details, significantly enhancing performance [7].

Multimodal Integration: Advanced systems combine IR data with other analytical techniques, such as mass spectrometry, to constrain the chemical space and improve prediction accuracy [13] [6].

Performance Benchmarks and Validation

Current state-of-the-art models achieve remarkable accuracy in structure elucidation. The best-performing systems report top-1 accuracy of 63.8% and top-10 accuracy of 83.9% for compounds containing 6-13 heavy atoms [7]. When predicting molecular scaffolds rather than complete structures, accuracy increases to 84.5% top-1 and 93.0% top-10 [6].

These models are typically pretrained on large datasets of simulated IR spectra (over 600,000 compounds) followed by fine-tuning on experimental spectra from reference databases like NIST [6] [7]. This approach leverages the abundance of computational data while maintaining real-world applicability.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for IR Spectroscopy Analysis

| Resource | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | IR spectrum acquisition | Resolution: 1-4 cm⁻¹ for research, 8 cm⁻¹ for routine; Spectral range: 4000-400 cm⁻¹ |

| ATR Accessory | Sample analysis without preparation | Crystal materials: diamond (universal), ZnSe (aqueous solutions), Ge (high refractive index) |

| KBr Pellets | Solid sample preparation | FTIR grade, 300 mg for 13 mm die; requires drying at 110°C to remove water |

| NIST Database | Reference spectra | >16,000 compounds; GC-IR vapor phase spectra; 8 cm⁻¹ resolution [13] |

| Sigma-Aldrich Library | Commercial spectral database | >11,000 pure compounds; subscription-based access [13] |

| SDBS Database | Free spectral resource | IR, NMR, MS data for organic compounds; measured at AIST, Japan [13] |

The development of AI-based IR analysis has created new essential resources for researchers:

Spectral Databases: The NIST SRD 35 database provides 5,228 infrared spectra with chemical structures, combining EPA vapor-phase spectra and NIST laboratory measurements [13]. These datasets serve as critical benchmarks for training and validating machine learning models.

Simulated Spectra: Molecular dynamics simulations using force fields like PCFF can generate realistic IR spectra incorporating anharmonic effects, providing large-scale training data (over 600,000 compounds) for AI models [6].

Open Data Repositories: Resources like the Chemotion repository provide open-access, specialized research data that can supplement commercial databases and improve model performance for specific compound classes [13].

IR spectroscopy continues to evolve as an indispensable tool for organic molecule structure determination. While traditional interpretation methods focusing on characteristic functional group absorptions remain valuable for rapid analysis, emerging AI technologies are dramatically expanding the information that can be extracted from IR spectra. The integration of transformer-based models and comprehensive spectral databases enables increasingly accurate structure elucidation, making IR spectroscopy more powerful and accessible than ever before. For researchers in drug development and chemical sciences, these advances promise enhanced analytical capabilities that leverage the inherent advantages of IR spectroscopy—speed, cost-effectiveness, and operational simplicity—while overcoming traditional limitations in interpretation complexity.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy constitutes an indispensable analytical technique in the modern research laboratory, providing unparalleled insights into the structure and dynamics of organic molecules. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of both proton (1H) and carbon-13 (13C) NMR is fundamental to elucidating molecular skeletons and determining complete chemical structures without the need for extensive purification or crystallization [14]. This technical guide examines the core principles, applications, and experimental protocols of these complementary spectroscopic methods, framing them within the broader context of organic molecule structure determination techniques.

The evolution of Fourier transform (FT) NMR instruments has revolutionized the field, making the acquisition of carbon spectra routine despite the intrinsic sensitivity challenges of the 13C nucleus [14]. When employed in concert with other spectroscopic methods such as mass spectrometry and infrared spectroscopy, NMR enables the complete structural determination of unknown organic compounds, forming the foundational toolkit for analytical chemists in pharmaceutical development and basic research [15] [16].

Fundamental Principles of NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei when placed in a strong external magnetic field. Nuclei with non-zero spin, such as 1H and 13C, absorb electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency range, and the resulting resonance signals provide detailed information about molecular structure.

The 1H nucleus (proton) is the most sensitive NMR-active nucleus, while 13C presents significant detection challenges due to two fundamental limitations. First, the natural abundance of the 13C isotope is only 1.08%, meaning that in a molecule with few carbon atoms, it is statistically unlikely that any single molecule will contain more than one 13C atom [14]. Second, the magnetic gyration ratio of a 13C nucleus is smaller than that of hydrogen, resulting in a lower resonance frequency and reduced sensitivity for NMR detection [14]. These factors combine to make 13C resonances approximately 6,000 times weaker than proton resonances, necessitating specialized approaches for signal acquisition [14].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of NMR-Active Nuclei

| Property | 1H NMR | 13C NMR |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Abundance | ~99.98% | ~1.08% |

| Nuclear Spin | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| Relative Sensitivity | 1 | 1.76 × 10⁻⁴ |

| Magnetic Gyration Ratio | 26.75 × 10⁷ rad·T⁻¹·s⁻¹ | 6.73 × 10⁷ rad·T⁻¹·s⁻¹ |

| Standard Reference Compound | Tetramethylsilane (TMS) | Tetramethylsilane (TMS) |

1H NMR Spectroscopy: Proton Analysis

Information Content and Spectral Interpretation

Proton NMR spectroscopy provides three critical pieces of information for structural elucidation: chemical shift, integration, and spin-spin coupling. The chemical shift (δ, measured in ppm) reveals the electronic environment of each proton, with typical values ranging from 0-12 ppm [14] [17]. Integration measures the area under absorption peaks, indicating the relative number of protons contributing to each signal [15]. Spin-spin splitting patterns arise from interactions between neighboring non-equivalent protons, following the n+1 rule where n represents the number of adjacent coupling protons [15].

The phenomenon of spin-spin splitting occurs due to magnetic interactions between neighboring hydrogen atoms, resulting in the splitting of NMR signals into multiple peaks [15]. This coupling provides crucial information about molecular connectivity and stereochemistry. More complex splitting patterns emerge from interactions between non-equivalent protons on adjacent carbons, producing multiplet patterns rather than simple doublets or triplets [15].

Chemical Shift Factors

Chemical shifts in 1H NMR are influenced primarily by the electronegativity of adjacent atoms and the hybridization of the carbon atom to which the proton is attached [15]. Electronegative elements cause a deshielding effect, shifting proton resonances downfield (to higher ppm values), with the effect diminishing as the distance between the proton and electronegative atom increases [14]. Proton equivalence, determined by molecular symmetry and chemical environments, simplifies NMR spectra as equivalent protons produce identical signals, while non-equivalent protons yield distinct resonances [15].

Table 2: Characteristic 1H NMR Chemical Shifts for Common Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Chemical Shift Range (ppm) | Proton Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Alkanes | 0.9-1.8 | R-CH₃, R-CH₂-R |

| Allylic | 1.6-2.2 | R-CH₂-C=C |

| Alkynes | 2.0-3.0 | ≡C-CH |

| Alcohols | 3.3-4.0 | R-OH |

| Ethers | 3.3-4.0 | R-O-CH |

| Alkyl Halides | 3.0-4.5 | R-X-CH (X = Cl, Br, I) |

| Aldehydes | 9.0-10.0 | R-CHO |

| Carboxylic Acids | 11.0-12.0 | R-COOH |

| Aromatics | 6.0-8.5 | Ar-H |

| Alkenes | 4.5-6.5 | C=CH |

13C NMR Spectroscopy: Carbon Skeleton Analysis

Special Considerations for Carbon NMR

Carbon-13 NMR spectroscopy provides direct information about the carbon skeleton of organic molecules, complementing the proton information obtained from 1H NMR [14]. The most significant advantage of 13C-NMR is the breadth of its spectral window, with carbon resonances occurring across a range of 0-220 ppm compared to only 0-12 ppm for protons [17]. This wide chemical shift distribution means that 13C signals rarely overlap, allowing researchers to distinguish separate peaks for each unique carbon environment, even in complex molecules [17].

Unlike 1H NMR, the area under 13C-NMR signals cannot be reliably used to determine the number of carbons due to the variable relaxation times and nuclear Overhauser effects that differentially affect signal intensities for different types of carbons [17]. Carbonyl carbons, for example, typically exhibit much smaller peaks than methyl or methylene carbons [17]. Consequently, the most valuable information provided by a 13C-NMR spectrum is the number of distinct signals and their chemical shifts, rather than integration values or multiplicity [17].

Decoupling Techniques

To address the challenge of carbon-proton coupling (with coupling constants typically ranging from 100-250 Hz), chemists generally employ broadband decoupling techniques that effectively 'turn off' C-H coupling, resulting in a spectrum where all carbon signals appear as singlets [17]. This proton decoupling dramatically simplifies the spectrum and enhances signal-to-noise ratio, making 13C NMR data more interpretable.

Chemical Shift Ranges for Carbon Nuclei

The chemical shifts of 13C nuclei are profoundly affected by electronegative effects and hybridization. When a hydrogen atom in an alkane is replaced by an electronegative substituent (O, N, halogen), the 13C signals for nearby carbons shift downfield, with the effect diminishing with distance from the electron-withdrawing group [17].

Table 3: Characteristic 13C NMR Chemical Shifts for Organic Functional Groups

| Carbon Type | Chemical Shift Range (ppm) | Representative Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Alkyl | 0-50 | R-CH₃, R-CH₂-R |

| Alkynes | 50-80 | HC≡C-R |

| Alkenes | 100-150 | H₂C=CH-R |

| Aromatics | 110-170 | Benzene derivatives |

| Nitriles | 115-125 | R-C≡N |

| Amides | 160-180 | R-CONR₂ |

| Carboxylic Acids | 160-185 | R-COOH |

| Esters | 160-180 | R-COOR |

| Aldehydes | 190-220 | R-CHO |

| Ketones | 190-220 | R-COR |

Comparative Analysis: 1H vs. 13C NMR

While both techniques provide structural information, 1H and 13C NMR offer complementary data for organic structure elucidation. Proton NMR is superior for determining the number and type of hydrogen atoms, integration (relative proton counts), and connectivity through spin-spin coupling patterns [15]. In contrast, carbon NMR excels at determining the number of non-equivalent carbon atoms, identifying carbon types (methyl, methylene, aromatic, carbonyl, etc.), and providing direct information about the carbon skeleton [14] [17].

The broader chemical shift range of 13C NMR (0-220 ppm) compared to 1H NMR (0-12 ppm) makes it particularly valuable for analyzing larger, more complex structures where proton signals often overlap [17]. For example, in the proton spectrum of 1-heptanol, only the signals for the alcohol proton and the two protons on the adjacent carbon are easily analyzed, while the remaining proton signals overlap. However, in the 13C spectrum of the same molecule, each carbon signal is readily distinguishable, confirming the presence of seven non-equivalent carbons [17].

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Structure Elucidation of Unknown Compounds

For complete structure determination of unknown organic molecules, NMR spectroscopy is typically employed in combination with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) [16]. Two-dimensional NMR techniques have dramatically advanced the field, allowing structure elucidation of new organic compounds with sample amounts of less than 10 μg [16]. Key 2D-NMR experiments include COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy), HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence), and HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation), which provide crucial information about through-bond connectivities.

The pure shift approach, which provides 1H-decoupled proton spectra, has dramatically simplified the interpretation of both 1D and 2D NMR spectra [16]. For extremely hydrogen-deficient compounds, methodology combining new 2D-NMR experiments providing long-range heteronuclear correlations with computer-assisted structure elucidation (CASE) has proven particularly powerful [16].

Diagram 1: NMR Structure Elucidation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the systematic process for determining molecular structures using NMR spectroscopy, from sample preparation to final structure confirmation.

Computer-Assisted Structure Elucidation (CASE)

CASE expert systems mimic the reasoning of a human expert during structure elucidation, offering significant advantages in reliability and comprehensiveness [16]. These systems explicitly state all axioms about the interrelationship between spectra and structures, deduce all logical consequences without exclusion, and can determine structures that would be manually undecipherable [16]. When initial spectral data are complete and consistent, computer-based structure elucidation proceeds far more quickly and reliably than manual approaches [16].

Experimental Protocol: Basic 1H and 13C NMR Acquisition

Sample Preparation:

- Sample Quantity: For 1H NMR, 1-10 mg of compound; for 13C NMR, 10-50 mg (due to lower sensitivity)

- Solvent Selection: Deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃) is most common; use DMSO-d6 for polar compounds, D₂O for water-soluble compounds

- Reference Standard: Add 0.1% tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal reference (δ = 0 ppm) or use solvent residual peak as secondary reference

- NMR Tube: Use high-quality 5 mm NMR tubes; sample volume typically 500-600 μL

Spectral Acquisition Parameters for 1H NMR [18]:

- Pulse Sequence: zg30 (standard single pulse) or NOESY for solvent suppression

- Spectral Width: 12-16 ppm

- Relaxation Delay: 1-5 seconds

- Number of Scans: 16-64 for 1H NMR

- Temperature: 25-30°C (298-303 K)

- 90° Pulse Width: Typically 8-12 μs

Spectral Acquisition Parameters for 13C NMR [18]:

- Pulse Sequence: zgpg30 with broadband proton decoupling

- Spectral Width: 220-240 ppm

- Relaxation Delay: 2-5 seconds

- Number of Scans: 100-1000 (due to low sensitivity)

- Temperature: 25-30°C (298-303 K)

- Acquisition Time: 1-2 seconds

Spectral Processing [19]:

- Fourier Transformation: Apply appropriate window function (exponential for S/N enhancement, Gaussian for resolution enhancement)

- Phase Correction: Adjust zero-order and first-order phase for pure absorption lineshape

- Baseline Correction: Apply polynomial or spline functions to correct baseline distortions

- Chemical Shift Referencing: Reference spectrum to TMS at 0 ppm or solvent residual peak

Protocol for 2D NMR Experiments

For complex structure elucidation, the following 2D NMR experiments are recommended as a standard set [16]:

- 1H-1H COSY: Identifies proton-proton through-bond correlations (3-bond couplings)

- HSQC (or HMQC): Identifies direct 1H-13C correlations (1-bond couplings)

- HMBC: Identifies long-range 1H-13C correlations (2- and 3-bond couplings)

- NOESY or ROESY: Provides through-space correlations for stereochemical assignment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for NMR Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Chloroform (CDCl₃) | Primary NMR solvent for organic compounds | Contains 0.03% TMS as reference; residual CHCl₃ peak at 7.26 ppm (1H), 77.16 ppm (13C) |

| Deuterated DMSO (DMSO-d6) | Solvent for polar compounds | Residual DMSO peak at 2.50 ppm (1H), 39.52 ppm (13C); hygroscopic |

| Deuterated Water (D₂O) | Solvent for water-soluble compounds | Requires water suppression techniques; no internal reference |

| Tetramethylsilane (TMS) | Internal chemical shift reference | Inert, volatile, single sharp peak at 0 ppm for both 1H and 13C |

| DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) | Water-soluble chemical shift reference | Single sharp methyl peak at 0 ppm; preferred over TSP for biofluids |

| TSP (3-(trimethylsilyl)-2,2′,3,3′-tetradeuteropropionic acid) | Water-soluble chemical shift reference | pH-sensitive; use with caution in unbuffered solutions |

| NMR Tubes (5 mm) | Sample containment | High-quality tubes essential for reproducible results |

| Shimming Tools | Magnetic field homogeneity optimization | Automated shimming routines standard on modern instruments |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of NMR spectroscopy continues to evolve with several emerging trends enhancing its capabilities for molecular structure determination. Ultrafast 2D-NMR can now acquire a 2D-NMR spectrum in several seconds, dramatically increasing throughput [16]. Pure shift methods that provide 1H-decoupled proton spectra are simplifying the interpretation of complex spectra [16]. Additionally, new methodologies for mixture analysis without physical separation are expanding the application of NMR to complex biological and environmental samples [16].

Recent developments in NMR instrumentation include the availability of spectrometers operating at frequencies exceeding 1 GHz, cryogenically cooled probe technology for enhanced sensitivity, and microprobe designs for small-volume samples [19]. These advances, combined with dynamic nuclear polarization techniques, have pushed detection limits to nanomolar concentrations for samples as small as 50 μL [19].

Diagram 2: NMR Experiment Classification. This diagram categorizes the primary NMR experiments used in structural elucidation, showing the relationship between 1D and 2D techniques.

1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy remain cornerstone techniques for unraveling molecular skeletons and determining organic compound structures. While 1H NMR provides detailed information about proton environments and connectivity, 13C NMR directly probes the carbon skeleton with a wider chemical shift range that minimizes signal overlap. The integration of these complementary approaches, enhanced by advanced 2D experiments and computer-assisted structure elucidation, provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful toolkit for molecular characterization.

As NMR technology continues to advance with higher field strengths, improved sensitivity, and faster acquisition methods, its role in structural determination will undoubtedly expand. The ongoing development of pure shift methods, mixture analysis techniques, and sophisticated algorithms for spectral interpretation promises to further solidify NMR spectroscopy's position as an indispensable technique in the analytical sciences.

Determining Molecular Mass and Fragmentation Patterns with Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an indispensable analytical technique for determining the molecular mass and structural characteristics of organic compounds. It enables researchers to elucidate chemical structures by measuring the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of gas-phase ions, providing critical information about molecular weight, elemental composition, and functional groups through analysis of fragmentation patterns [20]. The fundamental process involves converting sample molecules into ions, separating these ions based on their m/z ratios, and detecting them to generate a mass spectrum that serves as a molecular fingerprint.

The continued evolution of mass spectrometry instrumentation and computational methods is pushing the boundaries of what is analyzable, allowing researchers to probe ever-larger molecules and more complex chemical systems [21]. As noted in assessments of the 2025 mass spectrometry landscape, technical advances are fostering interdisciplinary collaborations that turn complex data into insights with real-world impact, particularly in drug discovery and development [21] [20]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical overview of current methodologies for determining molecular mass and interpreting fragmentation patterns, framed within the context of modern organic molecule structure determination research.

Instrumentation and Ionization Techniques

The selection of appropriate instrumentation and ionization methods is fundamental to successful mass spectrometric analysis. Different interfaces and ion sources accommodate varying sample types and analytical requirements.

Table 1: Common Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Technique | Abbreviation | Principle | Optimal Mass Range | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospray Ionization | ESI | Solution-phase ions transferred to gas phase through charged aerosol | Up to megadalton [21] | Polar molecules, proteins, protein-protein interactions [20] |

| Electron-Activated Dissociation | EAD | Electron removal from protonated molecular ions | Typical small molecules | Structural elucidation of synthetic opioids (e.g., nitazene analogs) [22] |

| Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization | MALDI | Laser desorption of sample embedded in light-absorbing matrix | Up to megadalton [21] | Large biomolecules, polymers, imaging |

The sophistication of modern mass spectrometers has increased to the point where instruments have become more "turnkey," facilitating ease of use by researchers who may not have deep fundamental expertise in mass spectrometry [21]. This accessibility has broadened the influence of MS into diverse fields including molecular biology, immunology, and infectious disease research [21].

Determining Molecular Mass

Fundamental Approaches

Molecular mass determination relies on accurate measurement of the m/z ratio of molecular ions or charged adducts formed during the ionization process. In the MS1 spectrum (the initial mass analysis), the protonated molecular ion [M+H]^+ is typically observed for organic molecules analyzed using electrospray ionization [22]. For molecules with multiple basic sites, double-charge ions such as [M+2H]^{2+} may also be detected, particularly for larger compounds [22].

High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) provides exact mass measurements that enable determination of elemental composition with sufficient accuracy to distinguish between different molecular formulas. Modern HRMS instruments can measure mass with precision sufficient to confirm molecular formulas, which is particularly valuable when analyzing novel compounds or complex mixtures.

Advanced Applications: Megadalton Measurements

Recent technical advances have dramatically expanded the mass range amenable to MS analysis. As highlighted in assessments of the field, "new ion sources and megadalton capabilities are emerging, [and] the boundaries of mass spectrometry are being redefined" [21]. This capability to analyze extremely large biomolecules opens new possibilities for characterizing macromolecular complexes, viral capsids, and other massive structures relevant to drug development.

Fragmentation Patterns and Structural Elucidation

Principles of Fragmentation

Fragmentation patterns provide the structural information necessary for comprehensive molecular characterization. When molecules undergo ionization, they often fragment in predictable ways that reflect their chemical structure. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) isolates precursor ions and subjects them to collision-induced dissociation (or other fragmentation methods), generating product ions that reveal structural details.

The resulting MS2 spectra contain fragment ions characteristic of the molecular structure. For example, in the analysis of nitazene analogs using electron-activated dissociation, characteristic product ions include double-charge free radical fragment ions [M+H]^{•2+} produced through removal of one electron from protonated molecular ions, along with alkyl amino side chain fragment ions, benzyl side chain fragment ions, and methylene amino ions [22].

Experimental Workflow for Structure Determination

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining molecular structure through mass spectrometry:

Advanced Fragmentation Techniques

Electron-Activated Dissociation (EAD) represents an advanced fragmentation method that has demonstrated particular utility for structural elucidation of complex molecules. In the analysis of nitazene analogs, EAD produces characteristic fragment ions that enable differentiation of structurally similar compounds [22]. The technique generates double-charge free radical fragment ions [M+H]^{•2+} through removal of one electron from protonated molecular ions, providing complementary fragmentation pathways compared to traditional collision-based methods [22].

Data Analysis and Computational Tools

Mass Spectrometry Query Language (MassQL)

The increasing volume and complexity of mass spectrometry data have necessitated development of sophisticated computational tools. Mass Spectrometry Query Language (MassQL) is an open-source language introduced in 2025 that enables flexible, manufacturer-independent searching of MS data [23]. This innovative approach allows researchers to directly query mass spectrometry data with an expressive set of user-defined mass spectrometry patterns without requiring programming expertise [23].

MassQL implements a specialized grammar to search for chemically and biologically relevant molecules by leveraging patterns in MS1 data (e.g., isotopic patterns, adduct mass shifts) and MS/MS fragmentation spectra (e.g., presence/absence of fragments and neutral losses) [23]. The language can incorporate chromatographic and ion mobility constraints, with query elements combinable using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to form complex queries [23].

Data Management Challenges

Mass spectrometry generates tremendous amounts of data, with dataset sizes having grown from 20-40 megabytes in the early days of GC-MS to modern laboratories generating 1-10 terabytes of data monthly [24]. This exponential growth in data volume presents significant challenges for storage, processing, and analysis, necessitating sophisticated data management strategies and computational tools [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Mass Spectrometry Experiments

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents protein degradation during sample preparation | Use EDTA-free formulations; PMSF is recommended [25] |

| HPLC-Grade Water | Preparation of mobile phases and sample solutions | Prevents contamination that interferes with detection [25] |

| Filter Tips | Prevents sample contamination | Essential for avoiding keratin and polymer contamination [25] |

| Appropriate Enzymes | Protein digestion for proteomics | Selection affects peptide size; trypsin most common [25] |

| Calibration Standards | Mass accuracy calibration | Required for precise mass measurement, especially in HRMS |

| Chromatography Columns | Sample separation prior to MS analysis | Choice affects resolution of complex mixtures |

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Mass spectrometry plays increasingly critical roles throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline. Key applications include:

Proteomics and Biomarker Discovery

MS-based proteomics can reveal alterations in protein abundance, isoforms, or post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination [25]. In vivo protein crosslinking studies enable detailed investigation of protein-protein interactions, providing insights that were previously only addressable through systematic mutation studies [25].

Metabolomics and Lipidomics

The increasing availability of multiomics approaches is influencing personalized medicine and biomedical research [21]. Mass spectrometry allows researchers to study a wide variety of biomolecules—proteins, peptides, lipids, metabolites, and glycans—and their spatial distributions in tissues [20]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

Molecular Imaging

Advanced mass spectrometry imaging techniques, such as the integration of tissue expansion microscopy with MS imaging, enable researchers to visualize biomolecular detail in tissues like cancer tumors in their native environments at unprecedented resolution [20]. This approach preserves molecular composition and native structure while achieving higher resolution without requiring expensive new hardware, making it accessible to biomedical researchers [20].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of mass spectrometry continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future applications in organic molecule structure determination:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: These technologies are increasingly employed to manage the huge volumes of data generated by modern MS systems, translating complex datasets into biological and clinical insights [20]. AI shows great potential for biomarker discovery and predictive modeling in precision medicine [20].

Data Integration Challenges: The biggest technical challenges currently facing the field involve integrating multiple data streams coming from different types of experiments—some from mass spectrometry technologies, others from orthogonal techniques [21]. Successfully integrating these diverse data into a cohesive framework represents both a challenge and opportunity for advancing personalized medicine [21].

Fundamental Training: Despite technological advances that have made MS more accessible, maintaining expertise in fundamental mass spectrometry principles remains critical. As noted by mass spectrometry leaders, "the more thoroughly and fundamentally you understand a piece of technology, the more creative you can be in exploiting it—the more creative you can be in designing new experiments and pushing into new areas" [21].

As mass spectrometry capabilities continue to advance—with instruments potentially becoming ubiquitous in clinics for real-time personalized medicine or deployed in extraterrestrial environments—the fundamental principles of molecular mass determination and fragmentation pattern analysis will remain cornerstone techniques for elucidating organic molecular structures [21].

The determination of unknown molecular structures is a cornerstone of scientific advancement in fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science. This process has evolved from relying solely on experimental spectral data to integrating sophisticated computational predictions. Traditionally, structure elucidation has depended on a suite of spectroscopic techniques, including mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). However, a modern paradigm shift is underway, fueled by the integration of machine learning (ML) and quantum chemistry. This new approach enhances the accuracy and efficiency of identifying molecular structures, particularly for complex organic molecules and novel compounds [26] [5]. This guide, framed within a broader thesis on organic molecule structure determination techniques, details a step-by-step methodology that marries traditional experimental clues with cutting-edge computational power, providing a robust framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Foundational Steps in Structure Elucidation

The initial steps in solving an unknown structure involve determining the fundamental molecular formula and assessing the molecule's saturation. These steps provide the critical framework upon which all subsequent hypotheses are built.

Determining Molecular Formula

The molecular formula is the foundational clue in any structural investigation. It is typically determined through the combined use of mass spectrometry (MS) and combustion analysis [27].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): MS provides the molar mass of the unknown compound by identifying the molecular ion peak (M⁺), which corresponds to the intact molecule after the loss of a single electron. The m/z value of this peak gives the molecular weight [27].

- Combustion Analysis: This technique provides the mass percent composition of each element within the compound (e.g., carbon, hydrogen, chlorine). The mass percentages are used to calculate the empirical formula, which is then scaled up to the molecular formula using the molar mass obtained from MS [27].

Example Calculation: A combustion analysis report showing a composition of 52.0% C, 38.3% Cl, and 9.7% H, coupled with an MS molecular ion peak at m/z = 92, leads to the molecular formula C₄H₉Cl [27].

Calculating the Index of Hydrogen Deficiency (IHD)

Once the molecular formula is known, the Index of Hydrogen Deficiency (IHD) is calculated. The IHD reveals the number of rings and multiple bonds (double or triple bonds) present in the molecule, offering immediate insight into the structural backbone [27].

The formula for calculating IHD is:

IHD = ( (2n + 2) - A ) / 2

Where:

n= number of carbon atomsA= (number of hydrogen atoms) + (number of halogen atoms) - (number of nitrogen atoms) - (net charge) [27]

Table: IHD Interpretation Guide

| IHD Value | Structural Implications | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No rings or multiple bonds; saturated molecule | Alkanes (e.g., hexane) |

| 1 | One double bond or one ring | Cyclohexane, 2-hexene |

| 4 or more | Often indicates an aromatic ring system (3 π-bonds + 1 ring) | Benzene (C₆H₆, IHD=4) |

The Computational Toolkit: Machine Learning and Crystal Structure Prediction

For complex molecules, particularly those with potential solid-state applications like pharmaceuticals, predicting the three-dimensional crystal structure is paramount. Modern computational methods have made this previously intractable problem feasible.

Machine Learning for Efficient CSP

Traditional CSP is computationally prohibitive because it requires exploring a vast space of possible molecular arrangements. Machine learning models can dramatically increase the efficiency of CSP by intelligently narrowing the search space.

- Space Group and Density Prediction: ML models can predict the most probable space groups and crystal packing density for a given molecule based on its molecular fingerprint (e.g., MACCSKeys) or 3D structure. This "sample-then-filter" strategy prevents the generation of low-density, unstable structures that are computationally expensive to process [28] [29].

- Performance Gains: One ML-based workflow, SPaDe-CSP, achieved an 80% success rate in predicting the correct crystal structure for a test set of 20 organic molecules—twice the success rate of a random search [28]. Graph neural networks (GNNs) trained with 3D molecular information have achieved a top-1 accuracy of 47.2% in predicting a molecule's space group, a significant improvement over baseline methods [29].

Table: Machine Learning Models in Crystal Structure Prediction

| Model/Workflow | Input Features | Key Function | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPaDe-CSP [28] | Molecular Fingerprint (MACCSKeys) | Predicts space group & packing density | 80% success rate on test set |

| Graph Neural Network [29] | 3D Molecular Graph | Predicts space group preference | 47.2% top-1 accuracy |

| Random Forest [29] | 2D & 3D Molecular Features | Predicts space group preference | Improved accuracy with combined features |

Integrating CSP into Broader Searches

Crystal structure prediction is not only an end in itself but also a powerful component in the larger quest for functional materials. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) can search vast chemical spaces for molecules with desired properties. By embedding CSP directly into the fitness evaluation of an EA, researchers can now optimize for solid-state properties, such as charge carrier mobility in organic semiconductors, which are highly sensitive to crystal packing [5]. This "crystal structure-aware" evolutionary search has been shown to outperform methods that rely on molecular properties alone [5].

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

The frontier of structure determination is being pushed by methods that incorporate deeper quantum-mechanical insights and tackle long-standing computational challenges.

Incorporating Quantum-Chemical Insight

Traditional molecular representations in machine learning, such as simplified graphs, often overlook crucial quantum-mechanical details. A new approach involves creating stereoelectronics-infused molecular graphs (SIMGs) that explicitly include information about natural bond orbitals and their interactions [26]. This quantum-chemical insight allows models to capture phenomena like stereoelectronic effects, which directly influence molecular geometry and reactivity. This approach enhances predictive performance, especially with the small datasets common in chemistry [26].

Orbital-Free Density Functional Theory

For decades, a major goal in quantum chemistry has been to perform accurate calculations using only electron density, without the computational cost of modeling individual orbitals. A recent breakthrough, STRUCTURES25, is a machine learning-powered orbital-free density functional theory (OF-DFT) method that achieves chemical accuracy in energy predictions for small organic molecules [30]. This advancement opens the door to fast, quantum-level modeling of large molecular systems, such as proteins, that are currently beyond the reach of standard methods [30].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Protocol for Machine Learning-Enhanced CSP

The following detailed protocol is adapted from recent research for implementing a machine learning-guided CSP workflow [28].

Data Curation and Model Training:

- Source a dataset from a reliable repository like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). Apply filters for data quality (e.g., organic molecules, R-factor < 10, no solvents) and to remove outliers based on lattice parameters and molecular weight.

- Split the curated dataset into training and test subsets (e.g., 80:20 ratio).

- Train machine learning models using the training subset. A model for space group prediction (a classifier) can be trained using cross-entropy loss, while a model for crystal density prediction (a regressor) can be trained using L2 loss. Algorithms like LightGBM, random forest, or neural networks can be compared for performance.

Structure Generation (SPaDe-CSP):

- Convert the SMILES string of the target molecule into a molecular fingerprint vector (e.g., MACCSKeys).

- Use the trained ML models to predict the most likely space group candidates and the target crystal density.

- Randomly select one of the predicted space groups and sample lattice parameters within reasonable ranges.

- Check if the sampled parameters satisfy the predicted density tolerance. If they do, place the molecules in the lattice to generate a candidate crystal structure.

- Repeat this process until a sufficient number of valid candidate structures (e.g., 1000) are generated.

Structure Relaxation:

- Optimize the generated crystal structures using a neural network potential (NNP) such as PFP, which provides near-DFT accuracy at a lower computational cost.

- Perform the optimization using an algorithm like L-BFGS with a defined force threshold (e.g., 0.05 eV Å⁻¹) to ensure the structures reach a stable energy minimum.

Workflow for Evolutionary Optimization Informed by CSP

For discovering new materials, the following workflow integrates CSP into a larger optimization loop [5]:

- Initialize a population of candidate molecules.

- For each molecule in the population, perform an automated, efficient CSP (see Section 5.1) to generate its likely crystal structures.

- Evaluate the fitness of each molecule based on the predicted property (e.g., electron mobility) of its most stable predicted crystal structure.

- Select the fittest molecules as parents for the next generation.

- Generate new candidate molecules ("children") by applying evolutionary operators (e.g., crossover, mutation) to the parent molecules.

- Repeat steps 2-5 for multiple generations until convergence, guiding the search toward regions of chemical space with optimal solid-state properties.

The diagram below visualizes this iterative process.

Modern structure determination relies on a combination of experimental data, computational tools, and extensive reference libraries.

Table: Key Resources for Structure Determination

| Resource/Solution | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [28] | Database | A curated repository of experimentally determined organic and metal-organic crystal structures used for training ML models and validating predictions. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [28] [5] | Computational Tool | Machine learning potentials (e.g., PFP, ANI) that provide near-DFT accuracy for energy and force calculations at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling rapid structure relaxation. |

| Sadtler Spectral Libraries [31] | Reference Library | Authoritative collections of IR, Raman, and MS spectra used to verify compound identity by comparing experimental data against known references. |

| NIST Mass Spectral Library [32] | Reference Library | A comprehensive database of mass spectra used for compound identification and deconvolution of complex mixture data via tools like AMDIS. |

| KnowItAll Software [31] | Analytical Software | A platform that provides access to Wiley's extensive spectral databases and analysis tools for interpretation, identification, and verification of compounds. |

| Orbital-Free DFT (OF-DFT) [30] | Computational Method | An emerging quantum chemistry method that uses electron density alone, accelerated by ML, to enable accurate calculations for large systems currently intractable with orbital-based methods. |

The process of solving unknown molecular structures has been transformed into a highly integrative discipline. The classical approach, which moves systematically from molecular formula to IHD and on to spectral interpretation, remains a vital foundation. However, the integration of machine learning for crystal structure prediction and the incorporation of quantum-chemical insights now provide an unprecedented level of accuracy and predictive power. Furthermore, the ability to conduct evolutionary searches of chemical space informed by solid-state properties opens new avenues for the rational design of pharmaceuticals and advanced materials. As spectral libraries continue to expand and computational models become ever more sophisticated, the synergy between experimental clues and computational prediction will undoubtedly remain the central paradigm for elucidating molecular structures.

Advanced and Specialized Methods for Complex Structural Challenges

Atomic-Resolution Scanning Probe Microscopy for Direct Molecular Imaging

The determination of organic molecule structures is a cornerstone of modern scientific research, with profound implications for drug development, materials science, and molecular engineering. Within this context, atomic-resolution scanning probe microscopy (SPM) has emerged as a transformative technique, enabling the direct visualization of molecular structures with unprecedented clarity. Unlike conventional crystallographic methods that often require high-quality single crystals, SPM techniques can resolve molecular configurations without long-range crystalline order, making them particularly valuable for studying complex molecular systems where traditional approaches face limitations.

This technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and applications of atomic-resolution SPM for direct molecular imaging, with emphasis on its growing role in structural determination of organic molecules. We present quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and emerging research directions that collectively establish SPM as an indispensable tool in the structural analyst's arsenal.

Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Core Imaging Modalities

Atomic-resolution scanning probe microscopy encompasses several specialized techniques that enable direct molecular imaging:

Non-contact Atomic Force Microscopy (nc-AFM): Utilizes frequency shift detection of an oscillating cantilever with a sharp tip to map surface topography with atomic resolution. Recent advancements in probe-particle models have significantly improved the accuracy of simulating nc-AFM images, enabling better interpretation of molecular structures [33].

qPlus-based AFM: A specific implementation of AFM that uses a quartz tuning fork sensor for enhanced stability and resolution. This technology has enabled atomic-resolution imaging of two-dimensional amorphous ice on graphite surfaces, revealing nucleation-free crystallization pathways [34].

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM): Measures electronic tunneling current between a sharp tip and a conductive surface, providing atomic-scale information on electronic structure. When combined with AFM, it offers complementary structural and electronic information.

Bond-Resolved AFM: An advanced AFM technique that achieves sufficient resolution to visualize individual chemical bonds within molecules, providing direct insight into molecular connectivity and bonding arrangements.

Recent Technical Advancements

The field of SPM has seen significant technical progress in recent years, enhancing its capabilities for molecular imaging:

Probe-Particle Model Improvements: The latest version of the Probe-Particle Model, implemented in the open-source ppafm package, represents substantial advancements in accuracy, computational performance, and user-friendliness [33]. These improvements facilitate more reliable simulation of SPM images, bridging the gap between experimental observations and molecular structure.

High-Speed Detector Technology: The development of fast pixelated detectors capable of frame speeds of 1 kHz or greater has enabled new imaging modalities like electron ptychography to be performed simultaneously with traditional Z-contrast imaging [35]. This combination provides both structural and compositional information from the same sample region.

Mixed Reality Integration: Emerging metaverse laboratory systems integrate mixed reality technologies with SPM, allowing intuitive gesture-based probe manipulation and imaging control [36]. This integration enhances spatial understanding of three-dimensional atomic arrangements, particularly beneficial for complex manipulation sequences.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of different atomic-resolution SPM techniques based on recent literature:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Atomic-Resolution SPM Techniques

| Technique | Lateral Resolution | Vertical Resolution | Optimal Environment | Key Applications in Molecular Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPlus AFM | Atomic (< 1 Å) [34] | Sub-Ångström [34] | Ultra-high vacuum, Cryogenic (15-120 K) [34] | 2D ice crystallization, Hydrogen-bonding networks, Defect visualization [34] |

| Probe-Particle AFM | Sub-molecular (1-2 Å) [33] | ~10 pm [33] | Variable (UHV to ambient) | Single-molecule analysis, Surface science, Automated structure recovery [33] |

| STM | Atomic (~1 Å) | ~1 pm | UHV, Cryogenic | Electronic structure mapping, Molecular orbitals, Surface adsorption |

| Electron Ptychography | Ångström-level [35] | N/A | UHV, STEM configuration | Light element imaging, Beam-sensitive materials, Biological structures [35] |

Table 2: Fractal Dimension Analysis of 2D Ice Crystallization [34]

| Temperature (K) | Phase | Fractal Dimension (Df) | Morphological Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 70 K | Phase I | ~1.7 | Dendritic hexagonal ice islands with narrow branches |

| 95 K | Phase II | ~1.7 | Larger dendritic structures with increased branch length |

| 120 K | Phase III | ~2.0 | Compact hexagonal structures with line defects |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Methods

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful atomic-resolution imaging of organic molecules:

Substrate Selection and Preparation:

- Graphite is preferred for many applications due to its weak interaction and structural incommensurability with water molecules, preserving metastable states during crystallization processes [34].

- Substrates must be atomically flat and clean, typically achieved through mechanical cleavage and in-situ heating under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions.

- Functionalized substrates can be used to promote specific molecular adsorption while maintaining mobility for self-assembly.

Molecular Deposition Techniques:

- Thermal sublimation in UHV allows controlled deposition of organic molecules onto pristine surfaces.

- Solution-based deposition enables study of molecules that cannot be vaporized without decomposition.

- In-situ preparation methods minimize contamination between synthesis and characterization.

Confinement Strategies for Single-Molecule Imaging: Recent advances utilize spatial confinement to stabilize individual molecules for imaging:

- Crystalline Sponge Method: Orientation of organic molecules within pre-prepared porous crystals [4].

- Encapsulated Nanodroplet Crystallization: Confinement of organic molecules within inert oil nanodroplets [4].

- Microporous Material Encapsulation: Using materials like zeolites to fix and visualize molecular configurations inside channels, even at room temperature [37].

Imaging Procedure for Atomic-Resolution AFM

The following protocol details the steps for obtaining atomic-resolution images of organic molecules using qPlus-based AFM:

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare graphite substrate by mechanical cleavage in air.

- Immediately transfer to UHV system with base pressure < 1×10⁻¹⁰ mbar.

- Thermally anneal substrate at 773 K for 30 minutes to remove contaminants.

Molecular Deposition:

- For water molecules, deposit using a precision leak valve with chamber pressure of 5×10⁻⁹ mbar for 30-120 seconds at 15 K [34].

- For organic molecules, use a thermal evaporator with controlled temperature to achieve sub-monolayer coverage.

- Anneal at specific temperatures (70 K, 95 K, or 120 K for water ice) to induce crystallization [34].

AFM Imaging:

- Approach the surface using coarse positioning system until tunneling contact is established.

- Set qPlus sensor to oscillate with amplitude of ~1 Å at its resonance frequency.

- Use frequency shift detection (Δf) as feedback parameter for topography imaging.

- Acquire images with pixel resolution of 256×256 or 512×512 at scan rates of 1-10 minutes per frame.

- For high-resolution imaging, optimize parameters at specific temperatures: 70 K for fractal structures, 120 K for compact crystalline phases [34].

Data Processing:

- Apply line-by-line flattening to remove thermal drift artifacts.

- Use Fourier filtering to enhance periodic features while reducing noise.

- Compare with simulated images from probe-particle models for structural interpretation [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Atomic-Resolution SPM

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| qPlus Sensor | Quartz tuning fork with etched tungsten tip | Core sensing element for high-resolution AFM; provides exceptional stability for atomic-resolution imaging [34] |

| Graphite Substrate | HOPG (Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite) | Atomically flat surface for molecular deposition; weak interaction preserves molecular metastable states [34] |

| Molecular Sources | High-purity organic compounds (>99.9%) | Sample materials for structure determination; purity critical for interpretable results |

| Crystalline Sponges | Porous coordination polymers | Confinement method for pre-orienting organic molecules to facilitate structure determination [4] |

| Probe-Particle Software | ppafm open-source package | Simulation of SPM images; enables interpretation of experimental data and automated structure recovery [33] |

| Fast Pixelated Detector | Frame rates ≥1 kHz, high dynamic range | Enables simultaneous acquisition of multiple signals (e.g., ptychography with Z-contrast) [35] |

Case Studies and Applications

Direct Imaging of Two-Dimensional Ice Crystallization

Atomic-force microscopy has revealed non-classical crystallization pathways in two-dimensional bilayer ice on graphite surfaces. Contrary to classical nucleation theory, the crystallization proceeds via dendritic extension of fractal islands without forming a critical nucleus [34]. The process undergoes a distinct fractal-to-compact transition as temperature increases from 70 K to 120 K, with fractal dimension increasing from approximately 1.7 to 2.0 [34].

This study demonstrated the critical role of out-of-plane adsorbed water molecules in facilitating the rearrangement of hydrogen-bonding networks from disordered pentagons or heptagons to ordered hexagons. These ad-molecules dynamically shuttle between the adsorbate layer and the 2D bilayer structure, mediating three-dimensional interactions vital for the 2D crystallization process [34].

Metal-Organic Coordination Systems

SPM techniques have proven invaluable for characterizing metal-organic coordination systems, including two-dimensional metal-organic coordination networks (MOCNs), crystalline metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and discrete metallosupramolecular architectures (DMSAs) [38]. The combination of scanning tunneling microscopy and atomic force microscopy provides nanoscale resolution imaging across different length scales, revealing both structural and electronic properties of these complex systems.

These characterization capabilities are particularly important for applications in functional materials, where precise control over metal-organic structures enables tuning of functional properties for specific technological applications [38].

Single-Molecule Imaging via Confinement Strategies

Recent advances have demonstrated ångström-level spatial resolution for single molecules using confinement strategies with various microscopy techniques [37]. These approaches address the fundamental challenges of molecular thermal activity and beam sensitivity by physically restricting molecular movement.

Notably, spatial confinement at room temperature has been achieved using microporous materials like zeolites, enabling fixation and visualization of single-molecule configurations inside channels [37]. This development represents a significant advancement for studying molecular structures under more physiologically relevant conditions.

Integration with Complementary Techniques

Correlation with Crystal Structure Prediction

Computational methods like crystal structure prediction (CSP) have emerged as powerful complements to experimental SPM data. Recent developments enable high-throughput CSP on hundreds to thousands of molecules, allowing evolutionary algorithms to optimize materials properties based on predicted crystal structures [5].