Parallel Synthesis in Organic Chemistry: Accelerating Drug Discovery through High-Throughput Methodologies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of parallel synthesis techniques and their transformative impact on organic chemistry, particularly in drug discovery.

Parallel Synthesis in Organic Chemistry: Accelerating Drug Discovery through High-Throughput Methodologies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of parallel synthesis techniques and their transformative impact on organic chemistry, particularly in drug discovery. It covers foundational principles, from the basic definition of parallel synthesis as a method for simultaneous processing of multiple reactions to its role in creating compound libraries for biological screening. The scope extends to modern methodological applications, including high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms, automated workstations, and the integration of machine learning for reaction optimization. It also addresses practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for multistep synthesis and purification, and concludes with a comparative analysis of validation techniques and the economic value of these methodologies in pharmaceutical development, offering researchers a complete guide from concept to application.

Parallel Synthesis Fundamentals: Principles, Core Concepts, and Historical Evolution

Parallel synthesis is a high-throughput technique in organic chemistry and drug discovery that enables the simultaneous preparation of multiple compounds or the parallel experimentation with multiple reaction conditions. Unlike traditional sequential synthesis, which processes one reaction at a time, parallel synthesis utilizes arrays of reaction vessels to dramatically accelerate research and development processes. This methodology has become indispensable in modern chemical research, particularly in pharmaceutical development where rapid generation of compound libraries is essential for screening potential drug candidates [1]. The approach represents a fundamental shift from linear, one-by-one synthesis to multidimensional experimentation, significantly enhancing efficiency in both discovery and optimization phases of research.

Core Principles and Definitions

Fundamental Concepts

Parallel synthesis operates on the principle of conducting multiple chemical reactions simultaneously under varied conditions or with different starting materials. This methodology is characterized by its systematic approach to experimentation, where reactions are performed in identical or systematically varied conditions across multiple reaction vessels. The core objective is to maximize data generation while minimizing time and resource investment. According to market research, the chemical synthesizer sector is experiencing substantial growth, with the market size valued at USD 2.18 billion in 2024 and projected to cross USD 8.67 billion by 2037, registering more than 11.2% CAGR during the forecast period [1]. This growth is largely driven by the adoption of automated parallel synthesis technologies that significantly enhance research productivity.

Comparison with Traditional Methods

Table 1: Comparison Between Parallel Synthesis and Traditional Sequential Synthesis

| Parameter | Parallel Synthesis | Sequential Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (dozens to hundreds of reactions simultaneously) | Low (single reactions processed consecutively) |

| Time Efficiency | Significantly reduced synthesis time per compound | Lengthy overall process for multiple compounds |

| Resource Utilization | Optimized use of equipment and laboratory space | Sequential use of resources |

| Experimental Uniformity | Consistent reaction conditions across vessels | Potential variation between batches |

| Automation Potential | High compatibility with automated systems | Limited automation opportunities |

| Data Generation | Rapid generation of structure-activity relationships | Slow accumulation of experimental data |

The transition to parallel synthesis methodologies represents a paradigm shift in chemical research, enabling researchers to address complex optimization challenges more systematically. This approach is particularly valuable in medicinal chemistry and materials science, where understanding the relationship between multiple variables is essential for developing optimal compounds or materials [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Microwave-Assisted Parallel Peptide Synthesis Protocol

The application of microwave irradiation to solid-phase peptide synthesis represents a significant advancement in parallel synthesis methodology, increasing product purity and reducing reaction time. The following protocol details the parallel synthesis of peptide libraries in 96-well plates using microwave irradiation [2].

Materials and Equipment

- Solid Support: Appropriate resin for solid-phase peptide synthesis

- Reagents: Fmoc-protected amino acids, coupling reagents (HBTU, HATU, etc.), deprotection solution (piperidine in DMF)

- Solvents: High-quality DMF, DCM, methanol

- Equipment: 96-well polypropylene filter plates, multichannel pipette, microwave reactor with temperature control

- Vessels: Chemical-resistant deep-well plates compatible with microwave irradiation

Step-by-Step Procedure

Plate Preparation: Array the solid-phase support into each well of a 96-well plate using a multichannel pipette for consistent distribution.

Resin Swelling: Add an appropriate solvent (typically DCM or DMF) to each well to swell the resin, ensuring uniform suspension.

Fmoc Deprotection:

- Add deprotection solution (20% piperidine in DMF) to each well.

- Irradiate in a microwave reactor for 4 minutes under temperature-controlled conditions (typically 75°C).

- Drain the solution and wash the resin thoroughly with DMF (3-5 times).

Coupling Reaction:

- Prepare coupling solutions containing Fmoc-amino acids (3-5 equivalents) and coupling reagents in DMF.

- Add the coupling solutions to respective wells using a multichannel pipette.

- Irradiate in a microwave reactor for 6 minutes under temperature-controlled conditions (typically 75°C).

- Drain the coupling solutions and wash the resin with DMF.

Iterative Cycle: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for each amino acid addition in the target peptide sequence.

Cleavage and Isolation:

- After completing the sequence, add cleavage cocktail (typically TFA-based) to each well.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 1-2 hours.

- Collect the filtrate containing the crude peptide into a collection plate.

- Evaporate solvents and precipitate peptides.

Analysis: Analyze crude products directly for biological activity without HPLC purification when sufficient purity is achieved.

Using this protocol, a library of 96 different hexapeptides can be synthesized in approximately 24 hours (excluding characterization time). The method has been successfully applied to generate difficult hexa-β-peptides with an average initial purity of 61% and approximately 50% yield [2].

Parallel Synthesis of Ziegler-Natta Catalysts

The exhaustive and multi-step nature of Ziegler-Natta catalyst synthesis has long posed a bottleneck in synthetic throughput and data generation. The following protocol describes the parallel synthesis of magnesium ethoxide-based Ziegler-Natta catalysts using a custom-designed 12-parallel reactor system [3].

Materials

- Magnesium Source: Magnesium powder (particle size = 0.06-0.3 mm)

- Initiator: Iodine (I₂, purity > 99.0%)

- Solvents: Ethanol (anhydrous), n-heptane, toluene (dried over 3Å molecular sieve)

- Reagents: Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄), di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP)

- Atmosphere: High-purity nitrogen or argon gas

Step-by-Step Procedure

Reactor Setup:

- Perform a repetitive cycle of evacuation and N₂ purging to establish an inert atmosphere.

- Ensure all reaction vessels are properly sealed and connected to the stirring mechanism.

Magnesium Ethoxide (MGE) Preparation:

- Heat the parallel reactor system to 75°C.

- Add 3.0 mL of an I₂ solution in ethanol (0.13 mol L⁻¹) to each reaction vessel under N₂ flow.

- Stir at 250 rpm for 10 minutes to ensure proper dissolution and mixing.

- Add 0.25 g of Mg powder suspended in 3.0 mL of ethanol to each vessel, repeating this addition 5 times at 30-minute intervals.

- Continue the reaction for 3 hours after the final addition.

- Wash the resultant solid twice with 20 mL of heptane.

- Dry the solid content in parallel using a centrifugal vacuum evaporator.

Catalyst Synthesis - First Treatment:

- Charge each reaction vessel with 1.0 g of the prepared MGE and 10 mL of toluene.

- Cool the system to 5°C using an ice bath or cooling system.

- Slowly add 2.0 mL of TiCl₄ to each vessel over approximately 1 hour.

- Gradually heat the suspension to 90°C.

- Add 0.3 mL of DBP to each vessel.

- Increase the temperature to 110°C and maintain for 2 hours.

- Wash the solid twice with toluene via decantation or filtration.

Catalyst Synthesis - Second Treatment:

- Add 2.0 mL of TiCl₄ in 10 mL of toluene to each vessel.

- Maintain the reaction at 110°C for 2 hours.

- Wash the resulting product repeatedly with toluene followed by heptane.

- Dry under vacuum at room temperature.

This established system achieves over a tenfold reduction in synthetic scale compared to conventional methods while ensuring consistency and reliability. The protocol enables efficient generation of catalyst libraries with diverse compositions and physical features, serving as a foundation for data-driven establishment of structure-performance relationships in heterogeneous olefin polymerization catalysis [3].

Applications in Organic Chemistry and Drug Development

Pharmaceutical Applications

Parallel synthesis has revolutionized pharmaceutical research by enabling the rapid generation of compound libraries for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. In drug discovery, this methodology allows medicinal chemists to systematically explore chemical space around lead compounds, optimizing pharmacological properties while minimizing undesirable characteristics. The technology is particularly valuable in the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds, peptide mimetics, and natural product analogs that serve as starting points for drug development [4].

The pharmaceutical and biotech industry segment is poised to generate the highest revenue share of over 30% in the chemical synthesizer market, underscoring the critical role of parallel synthesis technologies in modern drug development. This dominance reflects the extensive application of parallel synthesis in optimizing pharmacological compounds, with medicinal chemists creating and assembling novel molecules with therapeutic potential through systematic parallel approaches [1].

Material Science and Catalyst Development

In material science, parallel synthesis enables the efficient exploration of new materials with tailored properties. The development of Ziegler-Natta catalysts through parallel methodologies demonstrates how this approach facilitates the understanding of complex structure-performance relationships in heterogeneous systems. By generating catalyst libraries with diverse compositions and physical features, researchers can systematically investigate the impact of various parameters on catalytic performance [3].

The integration of parallel synthesis with high-throughput screening technologies has created powerful platforms for materials discovery and optimization. This approach is particularly valuable in fields such as polymer science, nanomaterials development, and heterogeneous catalysis, where multiple variables influence the final material properties [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Parallel Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks for solid-phase peptide synthesis | Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-Ala-OH, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH |

| Coupling Reagents | Facilitate amide bond formation between amino acids | HBTU, HATU, TBTU, DIC, Oxyma Pure |

| Solid Supports | Insoluble polymeric support for solid-phase synthesis | Wang resin, Rink amide resin, 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin |

| Deprotection Reagents | Removal of temporary protecting groups | Piperidine in DMF (20-50%), TFA with scavengers |

| Specialized Catalysts | Enable specific transformations in parallel systems | NiFe₂O₄@MCM-41@IL/Pt nanocatalyst, Pd/Ni cross-coupling catalysts |

| Activated Magnesium Reagents | Catalyst precursors for polymerization catalysts | Magnesium ethoxide spheroidal particles |

| Titanium-Based Activators | Active component in Ziegler-Natta catalysts | Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄) |

| Internal/External Donors | Control stereoselectivity in polymerization | Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP), Cyclohexyl(dimethoxy)methylsilane (CMDMS) |

| High-Purity Solvents | Reaction medium for chemical transformations | Anhydrous DMF, toluene, n-heptane, dichloromethane |

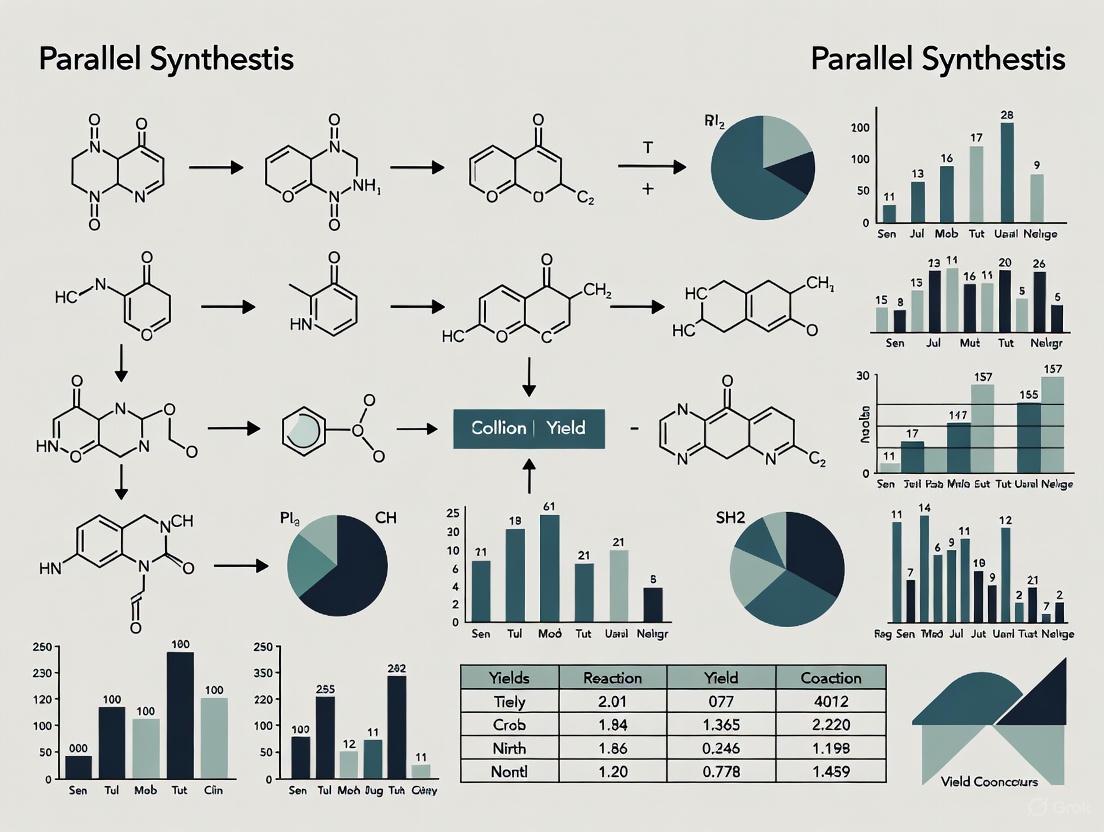

Workflow and Process Visualization

Conceptual Workflow for Parallel Synthesis

Experimental Setup for Parallel Synthesis

Quantitative Data Analysis

Efficiency Metrics in Parallel Synthesis

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics in Parallel Synthesis Applications

| Application Area | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Values | Traditional Method Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Library Synthesis | Synthesis Time for 96 hexapeptides | 24 hours [2] | Several days to weeks |

| Average Initial Purity | 61% [2] | Variable, often lower | |

| Average Yield | 50% [2] | Similar or slightly higher | |

| Ziegler-Natta Catalyst Synthesis | Scale Reduction | >10x [3] | Standard laboratory scale |

| Synthetic Throughput | 12 reactions simultaneously [3] | Single reactions sequentially | |

| Time per Batch | Significantly reduced | Typically 12 hours per batch | |

| Chemical Synthesizer Market | Market Size (2024) | USD 2.18 billion [1] | N/A |

| Projected Market Size (2037) | USD 8.67 billion [1] | N/A | |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2037) | 11.2% [1] | N/A |

Recent Advancements and Future Perspectives

The field of parallel synthesis continues to evolve with emerging technologies enhancing its capabilities and applications. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents one of the most significant recent advancements, with companies investing approximately USD 199 billion in AI technologies by 2025 [1]. This integration enables more intelligent experimental design, predictive modeling, and optimization of reaction conditions in parallel formats.

Recent innovations include the development of cloud-based automated laboratories such as IBM's RoboRXN, which combines AI with parallel synthesis capabilities to facilitate remote discovery and synthesis of novel compounds. This platform has generated over five million reaction predictions since its launch in 2018, demonstrating the powerful synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation in parallel formats [1].

The growing emphasis on green chemistry principles has driven the development of more sustainable parallel synthesis methodologies. Recent research has focused on integrating microwave irradiation, flow chemistry, and recyclable catalysts to minimize environmental impact while maintaining high throughput [4]. These approaches align with the broader trend toward sustainable chemical manufacturing while leveraging the efficiency advantages of parallel processing.

Future developments in parallel synthesis are likely to focus on increased integration with automated analytical systems, real-time reaction monitoring, and closed-loop optimization algorithms. These advancements will further accelerate the discovery-optimization cycle, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and faster development of novel compounds with desired properties.

In the field of organic chemistry, particularly within drug discovery and development, the efficiency of synthesizing target compounds is paramount. Traditional sequential synthesis has long been the cornerstone of organic synthesis, constructing molecules through a linear series of individual reactions [5]. In contrast, parallel synthesis represents a modern methodology enabling the simultaneous production of multiple compounds or libraries through systematic, parallel reaction execution [6]. This application note delineates the core distinctions between these approaches, provides quantitative comparisons, and details practical protocols for implementing parallel methodologies within research focused on organic synthesis and drug development. The shift towards parallel techniques is driven by the necessity for accelerated compound generation and screening in the pursuit of novel therapeutic agents [7] [8].

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Workflows

The underlying workflows of sequential and parallel synthesis are fundamentally distinct, impacting throughput, resource allocation, and application.

Traditional Sequential Synthesis is a linear process. A single target molecule is synthesized through a multi-step sequence where each reaction is conducted individually. The product of each step is typically isolated and purified before proceeding to the subsequent reaction [8] [5]. This method offers high flexibility for optimizing individual steps but is inherently time-consuming when a diverse array of compounds is required.

Parallel Synthesis is a divergent process. Multiple related compounds are synthesized simultaneously in separate reaction vessels. This is achieved by reacting a set of different starting materials with a common reagent or, more commonly, by reacting a single starting material with a set of different reagents under identical reaction conditions [6] [9]. This approach is highly amenable to automation and is designed for the rapid generation of compound libraries.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical relationship and workflow difference between these two strategies:

Quantitative Attribute Comparison

The choice between sequential and parallel synthesis is guided by specific project requirements. The table below summarizes the key attributes of each approach to inform this decision.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sequential vs. Parallel Synthesis

| Attribute | Traditional Sequential Synthesis | Parallel Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Linear, stepwise synthesis of a single target molecule [5] | Simultaneous synthesis of multiple compounds in separate vessels [6] |

| Throughput | Low (one compound per full sequence) [5] | High (dozens to hundreds of compounds per run) [6] [9] |

| Automation Potential | Low to moderate; difficult to fully automate multi-step sequences [6] | High; highly amenable to automation and robotics [6] [8] |

| Resource Efficiency | Lower for generating diverse libraries; requires separate sequences for each target | Higher for generating libraries; shared reaction conditions and setups [6] |

| Primary Application | Optimization of a single lead compound, late-stage functionalization, method development [5] | Rapid generation of compound libraries for hit discovery and lead optimization (SAR studies) [7] [6] |

| Flexibility & Control | High flexibility to adjust conditions for each individual reaction step [5] | Lower flexibility; reactions must be compatible with a standardized set of conditions [6] |

| Purification & Characterization | Straightforward purification and characterization after each step [6] | Can be complex due to simultaneous generation of multiple products; often requires parallel purification [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Parallel Synthesis of an Amide Library

This protocol details a 2x2 parallel synthesis of amides via the Schotten-Baumann reaction, adapted from a microfluidic study [9]. The methodology demonstrates the principles of parallel synthesis and can be scaled to a larger format using automated liquid handlers or multi-well reactor plates.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Parallel Amide Synthesis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Benzylamine (A1) | Amine building block 1; provides structural diversity to the library [9] |

| 4-Bromobenzylamine (A2) | Amine building block 2; provides structural diversity to the library [9] |

| Acetyl Chloride (B1) | Acid chloride building block 1; reacts with amines to form amide bonds [9] |

| Isobutyryl Chloride (B2) | Acid chloride building block 2; provides steric and electronic diversity [9] |

| Triethylamine | Base; scavenges HCl produced during the reaction, driving the reaction forward and preventing salt formation of the amine [9] |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Solvent; an aprotic polar solvent suitable for the reaction [9] |

| Parallel Reactor | A device with multiple isolated reaction chambers (e.g., microfluidic chip, multi-well plate) [9] |

| Syringe Pumps | For precise, continuous delivery of reagents in a microfluidic setup [9] |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The experimental workflow for a 2x2 parallel amide synthesis is as follows:

Procedure:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare 0.18 M solutions of each reactant in anhydrous acetonitrile (ACN). For the amine solutions (Benzylamine and 4-Bromobenzylamine), include a stoichiometric equivalent of triethylamine to act as an acid scavenger [9].

- Reactor Setup: Load the reagent solutions into separate input syringes. In the referenced microfluidic setup [9], the chip is designed with four input streams for the two amines (A1, A2) and two acid chlorides (B1, B2), which converge to create four distinct reaction channels.

- Initiate Reaction: Using syringe pumps, drive all reactant solutions into the microfluidic chip at a constant flow rate (e.g., 0.06 mL/min). This ensures uniform flow and mixing within the reaction channels. The reagents mix via diffusion in the laminar flow regime within the channel.

- Product Collection: Collect the output from each of the four reaction channels into separate glass vials. The output from each channel contains one of the four specific amide products.

- Analysis: Analyze the collected products using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to confirm the identity of the synthesized amides (based on mass) and to determine the purity of the outflow solution by comparing peak areas on the chromatogram [9].

Expected Outcomes and Data Analysis

Upon successful execution, this protocol yields four distinct amide products. The expected masses (m/z) from mass spectrometric analysis and typical purity values are summarized below.

Table 3: Expected Products and Analytical Data from 2x2 Amide Library [9]

| Product | Combination | Structural Formula | Mass (m/z) | Typical Purity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1B1 | Benzylamine + Acetyl Chloride | C₆H₅CH₂NHCOCH₃ | 150.1 | >98% |

| A1B2 | Benzylamine + Isobutyryl Chloride | C₆H₅CH₂NHCOCH(CH₃)₂ | 178.1 | >98% |

| A2B1 | 4-Bromobenzylamine + Acetyl Chloride | BrC₆H₄CH₂NHCOCH₃ | 228.0 | >96% |

| A2B2 | 4-Bromobenzylamine + Isobutyryl Chloride | BrC₆H₄CH₂NHCOCH(CH₃)₂ | 256.0 | >98% |

The comparative analysis and experimental protocol clearly establish the distinct roles of sequential and parallel synthesis in modern organic chemistry research. Traditional sequential synthesis remains indispensable for in-depth, stepwise optimization of complex target molecules where individual reaction control is critical [5]. Conversely, parallel synthesis is a powerful tool for accelerating discovery, particularly in the early stages of drug development where the rapid generation and screening of extensive compound libraries against parasitic or other disease targets is essential for identifying novel bioactive leads [7] [8].

The successful implementation of the provided protocol for parallel amide synthesis highlights key advantages: significantly enhanced throughput (four compounds synthesized in the time it takes to perform one sequential reaction) and efficient resource utilization through shared reaction conditions and automation-compatible workflows [9]. Future prospects for parallel synthesis are closely linked with advancements in automation, continuous flow technologies, and the integration of machine learning for reaction optimization, which will further solidify its role as a cornerstone methodology in efficient and sustainable chemical synthesis [10] [11].

The identification of a lead compound is a critical milestone in the drug discovery pipeline, representing a molecule with confirmed therapeutic potential against a defined biological target. This process, situated after initial target validation and hit discovery, is notoriously time-consuming and resource-intensive. The integration of parallel synthesis techniques has emerged as a transformative force, dramatically accelerating the generation and optimization of chemical libraries for biological screening. This Application Note delineates structured protocols and data-driven methodologies that leverage parallel synthesis to streamline the hit-to-lead (H2L) phase, providing researchers with a framework to enhance efficiency and outcomes in early-stage drug development [12] [13].

Key Methodologies for Accelerated Lead Discovery

The following table summarizes the core screening and design methodologies employed to rapidly identify and characterize lead compounds from vast molecular libraries.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for Accelerated Lead Identification

| Methodology | Core Principle | Primary Output | Throughput Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) [12] [14] | Automated, robotic testing of large compound libraries against a biological target in microtiter plates. | "Hit" compounds with confirmed activity. | Very High (100,000+ compounds) |

| DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) Screening [12] | Each small molecule in a library is covalently linked to a unique DNA tag, enabling simultaneous screening of billions of compounds. | DNA sequences encoding for binding molecules, which are decoded to identify "hits." | Ultra-High (Billions of compounds) |

| Parallel Synthesis [15] [13] | The simultaneous synthesis of multiple compounds or libraries in separate reaction vessels, using automated or semi-automated systems. | Focused libraries of structurally related compounds for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. | High (10s to 1000s of compounds) |

| In Silico (Virtual) Screening [12] | Computational docking of compound libraries into the 3D structure of a target protein to predict binding affinity and selectivity. | A prioritized list of compounds with high predicted activity for physical testing. | High (Millions of compounds virtually) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Parallel Synthesis of a Focused Compound Library

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a focused library of 96 analogs via parallel synthesis to establish preliminary Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR).

I. Materials and Reagents

- Solid Support: Polystyrene resin with a acid-labile linker (e.g., Wang resin) [15].

- Building Blocks: Diverse set of carboxylic acids (R1-COOH) and alkyl/aryl amines (R2-NH2).

- Reagents: Coupling reagents (e.g., HATU, DIC), solvents (DMF, DCM, DMSO), and cleavage cocktail (e.g., 95% TFA, 2.5% TIS, 2.5% H₂O).

- Equipment: 96-well reaction block, automated liquid handling system, orbital shaker, vacuum manifold, and analytical LC-MS system [15].

II. Procedure

- Resin Preparation: Dispense pre-swollen resin into each well of the 96-well reaction block.

- Coupling Cycle (R1):

- Deprotection: Remove the Fmoc-protecting group from the resin-bound linker using 20% piperidine in DMF.

- Washing: Wash the resin with DMF (3x) and DCM (2x) using the vacuum manifold.

- Coupling: To each well, add a unique carboxylic acid (R1-COOH, 3 equiv), HATU (2.95 equiv), and DIPEA (6 equiv) in DMF.

- Reaction: Shake the block for 12-16 hours at room temperature.

- Washing: Wash thoroughly with DMF and DCM.

- Coupling Cycle (R2):

- Activation: To each well, add a unique amine (R2-NH2, 3 equiv) and DIC (3 equiv) in DMF.

- Reaction: Shake the block for 4-6 hours. Microwave irradiation may be applied to accelerate reaction rates [15].

- Washing: Wash with DMF (3x) and DCM (3x).

- Cleavage and Isolation:

- Add the cleavage cocktail (TFA/TIS/H₂O) to each well and shake for 2-3 hours.

- Collect the filtrate containing the crude compound into a deep-well collection plate.

- Evaporate the TFA under a stream of nitrogen or via centrifugal evaporation [15].

III. Analysis and Purification

- Analysis: Analyze a sample from each well via LC-MS to determine purity and confirm the identity of the target compound [15].

- Purification: Purify compounds deemed suitable via mass-directed automated preparative HPLC. The system pools appropriate fractions into pre-tared vessels, which are evaporated in parallel to yield the final purified compounds [15].

Protocol for High-Throughput Purification of Parallel Synthesis Libraries

A robust high-throughput purification (HTP) system is essential for processing the large number of compounds generated via parallel synthesis.

I. Sample Preparation

- Dissolve the crude compounds in DMSO to a preset concentration (e.g., 10 mg/mL) [15].

- Use an automated system to transfer an aliquot for LC-MS analysis.

II. Analytical LC-MS

- Perform a rapid LC-MS analysis on each crude sample.

- Use the data to determine the approximate amount of the target compound and to develop an optimal method for preparative purification [15].

III. High-Resolution Mass-Directed Fractionation (HR-MDF)

- Inject the crude sample onto a preparative HPLC system coupled to a mass spectrometer.

- The HR-MDF system collects eluent only when the mass spectrometer detects the target ion, minimizing the number of fractions generated.

- This system allows for processing greater numbers and weights of crude compounds efficiently [15].

IV. Final Processing

- The system automatically pools fractions containing the target compound.

- Solvents are removed via parallel evaporation.

- A final LC-MS analysis is performed to confirm the purity and identity of the purified compound before it proceeds to biological screening [15].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from library creation to lead identification, highlighting the central role of parallel synthesis.

Integrated Lead Discovery Workflow

The subsequent diagram details the specific iterative cycle of parallel synthesis and analysis used during the Hit-to-Lead optimization phase.

Hit-to-Lead Optimization Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key reagents and materials that are fundamental to executing the protocols described in this note.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Parallel Synthesis and Lead Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Heterocyclic Building Blocks [12] | A vast class of organic compounds used as core structural elements in medicinal chemistry to create drug-like molecules with diverse stereochemistry and functional groups. |

| Solid-Phase Synthesis Resins [15] | Functionalized polymer beads (e.g., with Wang or Rink linkers) that serve as an insoluble support for synthesis, simplifying purification through filtration and washing. |

| Scavenger Resins [15] | Functionalized resins used to remove excess reagents or byproducts from a reaction mixture in a purification technique known as reactive filtration. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) [12] | Vast collections of small molecules, each tagged with a unique DNA barcode, allowing for the ultra-high-throughput screening of billions of compounds in a single vial. |

| MyriaScreen Diversity Collection [12] | A curated library of drug-like screening compounds designed to maximize chemical diversity, used in HTS campaigns to identify novel hit compounds. |

The evolution from traditional, single-compound synthesis to automated, high-throughput methodologies represents one of the most significant transformations in modern organic chemistry. This paradigm shift began with the emergence of combinatorial chemistry in the late 1980s, which introduced systematic approaches for creating large molecular libraries, and has culminated in today's integrated automated synthesis platforms that combine hardware, software, and digital planning tools [16]. The driving force behind this transformation has been the increasing pressure to accelerate drug discovery and materials development, particularly in pharmaceutical research where the traditional "one-compound-at-a-time" approach could no longer support the throughput demands of modern screening technologies [17] [16]. This article traces this technological evolution within the context of parallel synthesis techniques, providing both historical perspective and practical experimental protocols for implementing modern automated synthesis approaches in research settings.

The core principle underlying this field is the systematic and repetitive covalent connection of different "building blocks" to generate large arrays of diverse molecular entities [16]. What began primarily with peptide synthesis has expanded to encompass small molecules, oligonucleotides, and complex organic structures, enabling researchers to explore chemical space with unprecedented efficiency. The development of these methodologies has fundamentally changed the drug discovery process, with combinatorial and parallel synthesis technologies now routinely applied to numerous therapeutic areas, including antiparasitic drug discovery and beyond [7].

Historical Development of Combinatorial and Parallel Synthesis

Key Milestones in Combinatorial Chemistry

The origins of combinatorial chemistry can be traced to 1963, when biochemistry professor R. Bruce Merrifield developed solid-phase peptide synthesis, for which he later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1984 [16]. This foundational work established the principle of using a solid support to facilitate chemical synthesis through simplified purification and reaction driving through excess reagents. However, the field in its modern form began taking shape in the 1980s, when research scientist H. Mario Geysen developed a technique in 1984 to synthesize arrays of peptides on pin-shaped solid supports, followed by Richard Houghten's development in 1985 of creating peptide libraries in "tea bags" using solid-phase parallel synthesis [16].

A critical breakthrough came in 1988 when Árpád Furka introduced the split-and-pool (split-mix) method, enabling preparation of millions of new peptides in only a couple of days [18] [16]. This method proved highly efficient, generating peptide libraries with exponential growth in molecular diversity through each synthetic cycle. Through the 1980s and early 1990s, combinatorial chemistry focused predominantly on peptide and oligonucleotide synthesis, later expanding to small, drug-like organic compounds [16].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Combinatorial Chemistry Development

| Year | Milestone | Key Innovator(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Solid-phase peptide synthesis | R. Bruce Merrifield | Foundation for all solid-phase combinatorial methods; Nobel Prize 1984 |

| 1984 | Multi-pin peptide synthesis | H. Mario Geysen | First parallel synthesis arrays on solid supports |

| 1985 | "Tea bag" method | Richard Houghten | Efficient parallel peptide synthesis in permeable containers |

| 1988 | Split-and-pool method | Árpád Furka | Exponential library generation; true combinatorial synthesis |

| 1990 | Biological peptide library methods | Multiple groups | Application of biological systems to library generation |

| 1991 | One-bead-one-compound concept | Lam et al. | Direct linkage between single beads and individual compounds |

| 1990s | Small molecule libraries | Pharmaceutical industry | Expansion beyond peptides to drug-like organic compounds |

The Evolution of Parallel Synthesis Methodologies

Parallel synthesis developed as a complementary approach to combinatorial split-and-pool methods, with each compound synthesized in a separate reaction vessel rather than as mixtures [19]. This methodology offered the advantage that the identity of each compound was known and trackable throughout the synthesis process. While requiring more individual reactions than split-and-pool methods, parallel synthesis enabled preparation of larger quantities of each compound and was more readily adaptable to automation [19].

The acceptance of parallel synthesis and synthesizers among chemists drove development of planning tools like Design of Experiments (DoE) software to fully utilize reaction capacity, creating a synergistic relationship between automation and statistical experimental design [19]. As the technology evolved, researchers gained the ability to select the most appropriate synthesis technology based on their specific needs— considering factors such as library size, number of synthetic transformations, points of diversity, and precedent for each synthetic step [19].

Modern Automated Synthesis Platforms

Current Automated Synthesis Technologies

Modern automated synthesis platforms have evolved into sophisticated systems that integrate hardware, software, and chemistry expertise to accelerate and standardize chemical synthesis. Companies like Chemspeed provide automated synthesis solutions that enable complex workflows and "off-road chemistry" through versatile automation, handling reaction preparation, synthesis, work-up/purification, and analysis in an integrated system [20]. These systems can perform parallel synthesis across wide temperature and pressure ranges, supporting everything from small organic molecules to polymers and inorganic materials [20].

The principle of operation for these automated systems varies by synthesis type. For liquid-phase synthesis, automated synthesizers essentially mechanize traditional test-tube organic synthesis, with reaction vessels installed in thermostatic chambers with heating and cooling functions, while reagent addition and stirring are mechanically controlled [21]. For peptide synthesis, automation follows the Merrifield solid-phase synthesis method, mechanizing the cycle of de-protection, washing, condensation reaction, and washing [21]. A significant advancement has been the incorporation of microwave irradiation for dramatically shorter reaction times in peptoid library synthesis and other applications [19].

Flow Chemistry and Digital Integration

A particularly transformative development has been the emergence of automated flow chemistry systems, which offer significant advantages over traditional batch processing. Continuous flow synthesis provides enhanced safety by minimizing human contact with reagents, better reproducibility, more efficient mixing and heat transfer, and real-time reaction monitoring [17]. When combined with automation, these systems enable organic syntheses to be automatically carried out and optimized with minimal human intervention [17].

The integration of digital technologies with flow chemistry has created powerful new platforms for chemical synthesis. Automated systems can now be linked with Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools, creating systems that input a chemical structure and output plausible reaction pathways from commercially available materials [17]. Some advanced platforms have incorporated machine learning and artificial intelligence to develop intelligent algorithms and AI-driven synthetic route planning, creating continuous flow platforms that can design viable pathways to particular molecules and execute them autonomously [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Modern Automated Synthesis Platforms

| Platform Type | Key Features | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid-phase Automated Synthesizers | Mechanized traditional synthesis; thermostatic control; automated reagent addition | Library synthesis; reaction optimization; process development | Reproducibility; precise condition control; reduced operator exposure |

| Solid-phase Peptide Synthesizers | Automated Merrifield method; Fmoc/tBoc chemistry; microwave assistance | Peptide libraries; oligonucleotides; peptidomimetics | Rapid cycle times; simplified purification; high efficiency |

| Flow Chemistry Systems | Continuous flow channels; immobilized catalysts; process intensification | Multistep syntheses; hazardous chemistry; scale-up studies | Enhanced safety; better heat transfer; real-time monitoring |

| Integrated Digital Platforms | CASP integration; machine learning; automated optimization | De novo molecule design; route scouting; autonomous discovery | Pathway prediction; minimal human intervention; knowledge capture |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Parallel Library Synthesis Using Solid-Phase Techniques

This protocol describes the synthesis of a 96-member small molecule library using an automated parallel synthesizer, applicable for drug discovery lead optimization.

Materials and Equipment

- Automated parallel synthesizer (e.g., Chemspeed TECHNOLOGIES) with temperature control and liquid handling capabilities

- Reaction blocks with 96-well format and sealing systems

- Solid support: Wang resin (100-200 mesh, 1.0 mmol/g loading capacity)

- Building blocks: Diverse set of carboxylic acids (1.5 mmol each), amines (1.5 mmol each)

- Coupling reagents: HATU (0.95 M in DMF), N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA, 2.0 M in DMF)

- Solvents: Dimethylformamide (DMF, peptide synthesis grade), dichloromethane (DCM), methanol

- Cleavage cocktail: Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/water/triisopropylsilane (95:2.5:2.5)

Procedure

Resin Preparation: Distribute 50 mg of Wang resin to each well of the reaction block (0.05 mmol per well). Swell the resin in DCM for 30 minutes with agitation.

Building Block Distribution: Using the automated liquid handler, distribute 1.2 mL of each carboxylic acid building block (0.95 M in DMF) to individual wells according to the library design.

Activation Solution Addition: Add 1.2 mL of HATU solution (0.95 M in DMF) to each well, followed by 0.6 mL of DIPEA solution (2.0 M in DMF).

Coupling Reaction: Agitate the reaction block at 25°C for 3 hours. Monitor reaction completion using in-situ IR spectroscopy if available.

Washing Cycles: Drain the reaction solutions and perform sequential washings with DMF (3 × 2 mL), methanol (2 × 2 mL), and DCM (2 × 2 mL).

Cleavage: Add 1.5 mL of TFA-based cleavage cocktail to each well and agitate for 2 hours.

Product Isolation: Collect the cleavage solutions into a deep-well collection plate. Evaporate TFA under reduced pressure using a centrifugal evaporator.

Purification: Perform automated solid-phase extraction using pre-packed C18 cartridges.

Analysis: Characterize compounds by LC-MS and purify by preparative HPLC as needed.

Protocol 2: Automated Flow Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Compounds

This protocol adapts the continuous flow synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds based on the system described by Adamo et al. [17], suitable for the production of small molecule APIs and intermediates.

Materials and Equipment

- Flow chemistry system with multiple reagent streams, pumps, and temperature-controlled reactors

- In-line analytical modules: FlowIR, UV-Vis detector

- Separation modules: Liquid-liquid membrane separator

- Reagent solutions: Prepared at appropriate concentrations in compatible solvents

- Solvents: Methanol, acetonitrile, water, ethyl acetate (HPLC grade)

Procedure

System Configuration: Set up the flow system according to the desired synthetic pathway, connecting reagent reservoirs, pumps, reactors, and separation units.

Reagent Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of starting materials at 0.5-1.0 M concentrations in appropriate solvents, ensuring compatibility with flow system materials.

System Priming: Prime all fluidic paths with respective solvents, removing air bubbles and ensuring stable flow profiles.

Reaction Execution: Initiate the flow synthesis by starting pumps at predetermined flow rates to achieve desired residence times. For multistep sequences, coordinate flow rates between different stages.

Process Monitoring: Utilize in-line analytics (FlowIR, UV-Vis) to monitor reaction progress and intermediate formation in real-time.

In-line Workup: Direct reaction streams through membrane-based separators for immediate liquid-liquid extraction or through scavenger cartridges for purification.

Product Collection: Divert the purified product stream to an appropriate collection vessel.

System Cleaning: Implement automated cleaning cycles between syntheses to prevent cross-contamination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Modern automated synthesis relies on specialized reagents and materials optimized for high-throughput and automated applications. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for implementing the protocols described in this article.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HATU (Hexafluorophosphate Azabenzotriazole Tetramethyl Uronium) | Peptide coupling reagent | Amide bond formation; library synthesis | High efficiency; minimal racemization; use in automated synthesizers |

| Rink Amide Resin | Solid support for synthesis | Peptide and small molecule synthesis; cleavage yields amide | Standard loading 0.4-1.0 mmol/g; compatible with Fmoc chemistry |

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks for synthesis | Peptide library construction; diverse scaffold generation | Standard for solid-phase synthesis; wide commercial availability |

| SYNTHIA Retrosynthesis Software | Computer-aided synthesis planning | Retrosynthetic analysis; route scouting | AI-driven; integrates with automated platforms |

| Pre-packed Reagent Cartridges | Simplified reagent delivery | Specific reaction classes (e.g., SnAP, PROTAC formation) | Compatible with systems like Synple; ensure reproducibility |

| Scavenger Resins | Purification agents | Solution-phase purification; impurity removal | Quaternary ammonium salts; polymer-supported reagents |

Workflow Visualization

Evolution of Synthesis Methodology

Automated Flow Synthesis Platform Architecture

The journey from early combinatorial chemistry to modern automated platforms represents a fundamental transformation in how chemists approach molecular synthesis. The historical development of split-and-pool methods, parallel synthesis techniques, and solid-phase approaches has converged with advancements in automation, flow chemistry, and digital technologies to create powerful new paradigms for chemical discovery [17] [16]. These integrated systems now enable researchers to execute complex multistep syntheses with minimal human intervention, while capturing data and knowledge in digitally reproducible formats.

Looking forward, the continued integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with automated synthesis platforms promises to further accelerate chemical discovery [17]. We anticipate increased capabilities in predictive synthesis planning, autonomous optimization, and the ability to navigate chemical space more efficiently. As these technologies become more accessible and user-friendly, they will likely transition from specialized research environments to mainstream chemical synthesis, ultimately transforming how chemists design, execute, and analyze chemical reactions across both academic and industrial settings.

Parallel synthesis techniques have revolutionized organic chemistry research, particularly in the field of drug discovery. These methods enable the rapid, systematic assembly of large collections of related compounds, known as chemical libraries, which are essential for identifying novel bioactive molecules [22] [23]. The efficiency of parallel synthesis allows researchers to explore chemical space more comprehensively than traditional one-at-a-time synthesis, significantly accelerating the hit identification and optimization process [19]. This application note details established protocols and emerging methodologies for constructing high-quality compound libraries and screening process conditions using parallel synthesis platforms, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementation within modern drug discovery pipelines.

Compound Library Design and Curation

Library Design Strategies

The design of a screening library is a critical determinant of screening success. Several strategic approaches exist, each tailored to specific discovery objectives:

- Diverse Libraries: Designed to sample broad chemical space, these libraries are ideal for initial screening against novel targets with limited structural information. They are characterized by high Tanimoto similarity scores, indicating significant structural variety [24].

- Focused/Targeted Libraries: These collections are enriched with compounds known to interact with specific target families (e.g., GPCRs, kinases, proteases) or therapeutic areas, thereby increasing the probability of identifying hits for biologically relevant targets [24] [22].

- Lead-like and Drug-like Libraries: Designed according to predefined physicochemical criteria (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to improve the likelihood of oral bioavailability and favorable ADMET properties [25].

- Fsp³-Enriched Libraries: Reflecting the "Escape from Flatland" concept, these libraries feature a high fraction of sp³ hybridized carbons (Fsp³ ≥ 0.47), which correlates with improved solubility, bioavailability, and target selectivity compared to flat aromatic compounds [26].

- Natural Product-like Libraries: Inspired by the structural complexity and success of natural products in drug discovery, these libraries incorporate complex, often chiral, scaffolds with three-dimensional diversity [24].

Design Criteria and Compound Filtering

Strategic application of filtering criteria ensures library quality and drug-likeness. Key parameters and their typical ranges are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Standard Physicochemical Parameters for Library Design

| Parameter | Target Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | ≤ 500 g/mol | Ensures favorable absorption and permeability [25] |

| Calculated logP (ClogP) | < 5.0 | Controls lipophilicity to balance permeability and solubility [24] [25] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | ≤ 5 | Enhances cell membrane permeability [25] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | < 10 | Improves permeability and reduces metabolic clearance [25] |

| Polar Surface Area (PSA) | < 140 Ų | Optimizes for cell permeability [26] |

| Rotatable Bonds (RotB) | ≤ 10 | Reduces conformational flexibility, potentially improving bioavailability [24] |

| Fraction of sp³ carbons (Fsp³) | ≥ 0.47 | Increases molecular complexity and improves solubility [26] |

Additionally, compounds should be filtered to remove problematic chemical motifs using substructure filters such as REOS (Rapid Elimination of Swill) and PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) to minimize false positives in biological assays [24] [26]. The application of these filters, combined with strategic diversity analysis using Bemis-Murcko scaffold clustering or 3D-pharmacophore modeling, enables the creation of high-confidence screening collections [24].

Experimental Protocols for Library Synthesis

Protocol 1: Solid-Phase Parallel Synthesis of a Focused Library

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a focused compound library by diversifying a central scaffold on solid support, adapted from Breinbauer and Mentel [23].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- Solid Support: ChemMatrix or Polystyrene resin (loading: 0.5-1.0 mmol/g)

- Linker: Rink amide linker or Wang linker, appropriate for the desired final product

- Building Blocks: Diverse set of carboxylic acids, amines, and boronic acids

- Reagents & Solvents: N,N'-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), Hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), Piperidine, Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), Triisopropylsilane (TIS), Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dichloromethane (DCM), Diethyl ether

- Equipment: Polypropylene reaction vessels or 96-well filter plates, Automated peptide synthesizer or orbital shaker, Vacuum manifold, HPLC-MS for analysis

Procedure:

- Resin Loading: Place 100 mg of Rink amide resin (0.7 mmol/g) into each well of a 96-well filter plate. Swell the resin with DCM for 30 minutes.

- Fmoc Deprotection: Drain the DCM and treat the resin with 20% piperidine in DMF (2 × 2 mL, 5 + 10 minutes). Drain and wash thoroughly with DMF (5 × 2 mL).

- Scaffold Coupling: Prepare a solution of Fmoc-protected amino acid (4 equiv), HOBt (4 equiv), and DIC (4 equiv) in DMF. Add 1.5 mL of this solution to each well and agitate for 2 hours at room temperature. Drain and wash with DMF (3 × 2 mL).

- Diversification (Amidation): After Fmoc deprotection, add a solution of a diverse carboxylic acid (4 equiv), HOBt (4 equiv), and DIC (4 equiv) in DMF to individual wells. Agitate for 2 hours. Wash with DMF (3 × 2 mL) and DCM (3 × 2 mL).

- Diversification (Suzuki Coupling): For boronic acid diversification, prepare a solution of aryl bromide (if present on scaffold, 1 equiv), diverse boronic acid (3 equiv), Pd(PPh₃)₄ (0.1 equiv), and K₂CO₃ (3 equiv) in DMF/Water (4:1). Add to appropriate wells, seal the plate, and heat at 80°C for 12 hours. Cool and wash with DMF (3 × 2 mL), Water (3 × 2 mL), and DCM (3 × 2 mL).

- Cleavage: Treat each well with a cleavage cocktail of TFA/TIS/Water (95:2.5:2.5, 1.5 mL) for 2 hours with agitation. Collect the cleaved solution into a deep-well collection plate.

- Purification and Analysis: Evaporate TFA under a stream of nitrogen or by vacuum centrifugation. Purify compounds by preparative HPLC and characterize by LC-MS and ¹H-NMR [23].

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Parallel Synthesis of a 2x2 Amide Library

This protocol describes a parallel solution-phase synthesis of amides using a single-layer PDMS microfluidic device, enabling rapid optimization and library generation [9].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- Microfluidic Chip: Single-layer poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) device with parallel reaction channels

- Reactants: 0.18 M solutions of amines (e.g., benzylamine, 4-bromobenzylamine) and acid chlorides (e.g., acetyl chloride, isobutyryl chloride) in acetonitrile (ACN)

- Base: Triethylamine dissolved with the amines in ACN

- Equipment: Syringe pumps, Flexible small-gauge tubing for world-to-chip interface, Glass vials for collection, GC-MS for analysis

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation: Fabricate the microfluidic chip using conventional soft lithography with SU-8 photoresist to create a PDMS layer bonded to a glass slide [9].

- Reagent Loading: Load each reactant solution into separate syringes. Connect the syringes to the inflow ports of the microfluidic chip using tubing.

- Reaction Execution: Drive all reactant solutions hydrodynamically using a syringe pump at a constant volumetric flow rate (e.g., 0.06 mL/min), ensuring uniform flow and mixing. The on-chip residence time under these conditions is approximately 2.1 seconds [9].

- Product Collection: Collect the effluent from each of the four outflow ports into separate glass vials.

- Analysis and Purity Determination: Analyze each collected solution by GC-MS. Determine product purity by comparing peak areas on the gas chromatograms, calculating as 1 minus the ratio of the average integral of impurity peaks to the integral of the product peak [9].

Figure 1: Parallel Synthesis Library Generation Workflow. Two primary methodologies—Solid-Phase Organic Synthesis (SPOS) and Microfluidic Synthesis—are used to construct compound libraries following strategic design.

High-Throughput Screening and Process Optimization

Screening Methodologies for Hit Identification

Once compound libraries are synthesized, they are screened against biological targets to identify hits. Various biophysical methods are employed in screening campaigns, each with distinct advantages and applications, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Biophysical Screening Methods for Hit Identification

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures binding-induced refractive index changes | Medium | Label-free binding kinetics (kon/koff) [25] |

| Weak Affinity Chromatography (WAC) | Chromatographic separation based on weak interactions | High | Low-affinity binder identification [25] |

| Thermal Shift Assay (DSF) | Monitors protein thermal stability changes | High | Ligand binding-induced stabilization [25] [27] |

| Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) | Tracks molecule movement in temperature gradients | Medium | Solution-phase binding affinity [25] [27] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Detects chemical shift perturbations | Low | Fragment screening and binding site mapping [25] |

| Crystallographic Screening | Direct visualization of ligand-protein complexes | Low | Structure-based drug design [25] |

Protocol 3: Automated High-Throughput Process Optimization

This protocol utilizes high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms combined with machine learning to optimize chemical reaction conditions efficiently, minimizing experimental effort while maximizing information gain [28].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

- HTE Platform: Chemspeed SWING robotic system or equivalent automated platform

- Reaction Blocks: 96-well or 48-well metal blocks with pressure-resistant seals

- Liquid Handling System: Automated liquid dispenser with four-needle dispense head

- Analytical Tools: Integrated UPLC-MS or GC-MS systems

- Software: DoE (Design of Experiments) software and machine learning algorithms for data analysis and prediction

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Use DoE software to define the experimental space, selecting relevant continuous variables (temperature, concentration, time) and categorical variables (catalyst, solvent, ligand). A machine learning-guided approach can suggest the most informative initial experiments [28].

- Automated Reaction Setup: Program the liquid handling system to dispense reagents, catalysts, and solvents into individual wells of the reaction block according to the experimental design. The system can accurately deliver low volumes and even slurries [28].

- Parallel Reaction Execution: Execute all reactions in parallel under the specified conditions (e.g., heating, stirring). Modern HTE platforms enable precise control over reaction parameters for each well where possible [28].

- High-Throughput Analysis: Automatically sample reaction mixtures and analyze them using integrated UPLC-MS or GC-MS systems. Convert analytical data into reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, conversion, selectivity) [28].

- Machine Learning Optimization: Feed reaction outcomes back into the ML algorithm. The algorithm predicts the next set of promising conditions to test, creating a closed-loop optimization cycle. This process iterates until optimal conditions are identified, requiring minimal human intervention [28].

- Validation: Manually validate the top-performing conditions identified by the platform in traditional round-bottom flasks to confirm reproducibility and scalability.

Figure 2: Closed-Loop Process Optimization Workflow. This automated, iterative cycle combines high-throughput experimentation with machine learning to efficiently navigate complex parameter spaces and identify optimal reaction conditions.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of parallel synthesis and screening continues to evolve with several emerging technologies enhancing efficiency and capabilities:

- Nanoscale Automated Synthesis: Recent advances demonstrate the use of acoustic dispensing technology to synthesize compound libraries in 1536-well formats on a nanomole scale, dramatically reducing reagent consumption and waste generation [27]. This approach was successfully applied to synthesize a library via the Groebcke–Blackburn–Bienaymé reaction, with subsequent in-situ screening against the menin-MLL protein-protein interaction.

- Integrated Continuous Flow Platforms: Flow chemistry systems, such as the Vapourtec R-Series, enable automated library synthesis with superior heat and mass transfer, allowing safe use of high temperatures and pressures with volatile reagents like ammonia and dimethylamine [29].

- Machine Learning Integration: The combination of HTE platforms with ML algorithms represents a paradigm shift in reaction optimization, enabling simultaneous optimization of multiple variables and targets (yield, selectivity, cost) with fewer experiments than traditional methods [28].

- Advanced Microfluidics: Next-generation microfluidic devices allow genuinely parallel combinatorial synthesis in single-layer PDMS chips, offering improved throughput over sequential methods while minimizing cross-contamination [9].

These emerging technologies collectively support a trend toward more sustainable, efficient, and accelerated discovery workflows, reducing the environmental footprint of medicinal chemistry while increasing the pace of innovation.

Modern Parallel Synthesis Workflows: Technologies, Automation, and Real-World Applications

High-Throughput Experimentation has emerged as a cornerstone technology in modern organic chemistry and drug discovery, enabling the rapid screening and optimization of chemical reactions across vast parameter spaces. By leveraging parallel synthesis techniques, HTE allows researchers to simultaneously explore hundreds to thousands of reaction variables, dramatically accelerating the development of new synthetic methodologies and compound libraries. The foundation of these approaches lies in miniaturized reaction systems, primarily batch reactors and microtiter plates, which provide the physical platform for executing numerous experiments in parallel while conserving precious materials [30] [28].

The evolution of HTE has transformed traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization into a multidimensional exploration of chemical space. This paradigm shift is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, where the demand for rapid compound library synthesis and reaction screening necessitates efficient material use and data-rich experimentation [30]. Modern HTE platforms combine automated hardware for reaction execution with advanced analytical technologies and data analysis tools, creating integrated systems that bridge the gap between initial discovery and process development [31] [28].

Platform Architectures and Technical Specifications

Microtiter Plate Systems

Microtiter plates (MTPs) represent the workhorse format for high-density HTE campaigns, offering standardized footprints that integrate seamlessly with automated liquid handling systems. These platforms are characterized by their well-based architecture, which enables parallel reaction execution while maintaining individual reaction integrity.

Table 1: Microtiter Plate Formats for Chemical HTE

| Well Format | Typical Working Volume | Common Applications | Material Compatibility | Throughput Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-well | 1-5 mL | Reaction optimization, small library synthesis | Glass-reinforced polymers, glass inserts | Moderate throughput, suitable for heterogeneous reactions |

| 96-well | 100-1000 µL | Library synthesis, catalyst screening | Polypropylene, glass-coated wells | High throughput, standard for bioactivity screening |

| 384-well | 10-100 µL | Reaction screening, condition mapping | Polypropylene, specially coated plates | Ultra-high throughput, requires advanced liquid handling |

| 1536-well | 2-10 µL | Ultra-HT screening, direct-to-biology assays | Specialty polymers with low adsorption | Maximum density, minimal reagent consumption |

The choice of well format involves careful consideration of the trade-offs between throughput, material consumption, and experimental complexity. While 96-well plates offer a balanced approach for most synthetic applications, 384-well and 1536-well formats enable unprecedented screening density at the cost of more complex fluid handling requirements [28]. Modern MTP systems address key experimental challenges through specialized designs, including gas-permeable seals to minimize evaporation while allowing oxygen exchange, and pre-treated surfaces to reduce compound adsorption [32].

A significant advancement in MTP technology is the development of fed-batch microtiter plates that mimic industrial production conditions. These specialized plates incorporate a polymer-based substrate release system (e.g., silicone matrix with embedded glucose crystals) at the bottom of each well, enabling continuous nutrient feeding through an osmotically driven mechanism [32]. This approach maintains carbon-limited growth conditions essential for microbial cultivations and prevents undesirable metabolic phenomena associated with batch operations, effectively bridging the gap between screening and production conditions [32] [33].

Batch Reactor Platforms

Batch reactors in HTE encompass a diverse range of closed-system vessels where reactions proceed to completion without continuous input or output of materials. These systems vary significantly in scale and complexity, from simple vial-based arrays to sophisticated automated reactor blocks with individual parameter control.

Table 2: Batch Reactor Systems for Chemical HTE

| Reactor Type | Scale Range | Temperature Control | Mixing Mechanism | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass vial arrays | 1-20 mL | Shared block, individual possible | Magnetic stirring, orbital shaking | Simple, flexible, easy to access |

| Commercial reactor blocks (e.g., Chemspeed) | 0.5-10 mL | Individual or block control | Overhead stirring, vortex mixing | Integrated liquid handling, solid dosing |

| Custom robotic platforms | 0.1-5 mL | Variable by station | Various methods | Mobile robots linking specialized stations |

| Micro-bioreactors | 0.1-2 mL | Block control | Orbital shaking | Integrated pH/DO monitoring, fed-batch operation |

Batch reactors offer distinct advantages for HTE, including flexibility in reaction setup, compatibility with heterogeneous mixtures and solids, and the ability to perform complex multi-step sequences. Modern automated batch platforms, such as the Chemspeed SWING system, incorporate multiple reagent delivery mechanisms (including low-volume and slurry dispensing) and enable precise control over both categorical and continuous variables [28]. These systems have been successfully applied to diverse reaction classes including Suzuki-Miyaura couplings, Buchwald-Hartwig aminations, photochemical reactions, and asymmetric transformations [28].

The principal limitations of traditional MTP-based batch reactors include the inability to independently control temperature and pressure in individual wells and challenges with high-temperature reactions near solvent boiling points due to the lack of reflux capability [28]. However, ongoing engineering innovations continue to expand the operational boundaries of these systems, with custom solutions emerging for demanding reaction conditions.

Enabling Technologies and Analytical Methods

High-Throughput Analytics

The utility of HTE platforms is critically dependent on rapid, sensitive analytical methods capable of processing large numbers of samples with minimal material consumption. Several technologies have been developed specifically to address the analytical bottleneck in high-throughput synthesis.

Acoustic Droplet Ejection-Open Port Interface-Mass Spectrometry (ADE-OPI-MS) represents a transformative approach for ultra-high-throughput analysis. This technology utilizes acoustic energy to eject nanoliter-scale droplets directly from reaction wells into a continuously flowing solvent stream that delivers the sample to the MS ionization source [30]. Key advantages include:

- Extreme speed: Analysis times of 1-2 seconds per sample enable complete 384-well plate analysis in under 15 minutes

- Minimal sample consumption: Nanoliter volumes eliminate the need for extensive reaction scaling

- Matrix tolerance: High dilution factors (up to 1000-fold) in the OPI reduce ion suppression effects

- Versatility: Compatible with both nominal and high-resolution mass analyzers [30]

The ADE-OPI-MS workflow enables direct sampling of crude reaction mixtures without prior purification, making it ideally suited for rapid reaction screening and optimization [30]. In comparative studies, this approach has demonstrated superior sensitivity for detecting low conversion rates compared to standard UPLC-MS methods, while providing comparable semiquantitative assessment of reaction performance across diverse condition arrays [30].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) remains the workhorse analytical technique for HTE, providing both separation and characterization capabilities essential for complex reaction mixtures. Modern UPLC-MS systems adapted for high-throughput analysis can process samples in minutes while delivering robust qualitative and quantitative data [30] [34]. The integration of autosamplers and automated data processing pipelines enables continuous operation with minimal manual intervention.

For specialized applications, additional detection modalities are employed:

- Corona Aerosol Detection (CAD) for universal calibration without compound-specific standards

- In-line NMR for structural elucidation capabilities

- Online UV/Vis and fluorescence monitoring for reaction progress kinetics [31]

Software and Data Management

The data-rich nature of HTE necessitates sophisticated software solutions for experimental design, execution, and analysis. Platforms such as phactor have been developed specifically to streamline HTE workflows, enabling researchers to rapidly design reaction arrays, generate robotic instructions, and analyze results in an integrated environment [34].

Key capabilities of modern HTE software include:

- Inventory integration: Direct connection to chemical databases for automated population of reagent information

- Flexible experimental design: Support for full factorial, sparse matrix, and user-defined array configurations

- Hardware interoperability: Generation of instructions for both manual and robotic execution (e.g., Opentrons OT-2, SPT Labtech mosquito)

- Data visualization: Heatmaps, scatter plots, and multiplexed pie charts for intuitive result interpretation

- Standardized output: Machine-readable data formats compatible with electronic lab notebooks and predictive modeling tools [34]

The emergence of standardized data formats, such as the Open Reaction Database, facilitates knowledge sharing and enables the application of machine learning approaches to reaction optimization [31] [34]. This closed-loop integration of experiment planning, execution, and analysis represents a critical advancement toward fully autonomous discovery platforms.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reaction Optimization Screening in Microtiter Plates

This protocol describes a nanoscale screening approach for Pd-catalyzed C-N coupling, adapted from established methodologies with modifications for enhanced throughput [30].

Materials and Reagents

- 3-Bromopyridine (100 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- 4-Phenylpiperidine (100 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- Palladium catalysts (e.g., Pd2(dba)3, Pd(OAc)2, PdCl2, 10 mM in DMSO)

- Ligand sets (e.g., biarylphosphines, Josiphos derivatives, 20 mM in DMSO)

- Base solutions (e.g., Cs2CO3, K3PO4, t-BuONa, 1.0 M in water or appropriate solvent)

- DMSO (anhydrous) for dilution

- 384-well polypropylene microtiter plate

- Gas-permeable sealing membrane

Equipment

- Automated liquid handler (e.g., Opentrons OT-2, Tecan Freedom EVO)

- Centrifuge with plate adapters

- Heated shaker with plate capability

- UPLC-MS or ADE-OPI-MS system for analysis

Procedure

- Plate Setup: Design a 16×24 reaction array using HTE software (e.g., phactor) with catalyst variations along rows and base/ligand combinations along columns.

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare all reagent solutions at specified concentrations in anhydrous DMSO, except for inorganic bases dissolved in minimal water.

- Reaction Assembly:

- Dispense 20 µL of 3-bromopyridine stock solution to all wells (200 nmol, 1.0 equiv)

- Add 20 µL of 4-phenylpiperidine stock solution to all wells (200 nmol, 1.0 equiv)

- Transfer variable volumes of catalyst and ligand solutions according to the experimental design (typically 0.5-10 mol%)

- Add 2 µL of base solutions (2.0 equiv) to appropriate wells

- Dilute to a final volume of 200 µL with DMSO

- Reaction Execution:

- Seal plate with gas-permeable membrane

- Centrifuge briefly (1000 rpm, 1 min) to collect contents at well bottom

- Incubate at designated temperature (e.g., 80°C) with shaking (500 rpm) for 18 h

- Reaction Analysis:

- Cool plate to room temperature and centrifuge (3000 rpm, 5 min)

- For ADE-OPI-MS: Directly sample 2.5 nL from each well for analysis

- For UPLC-MS: Dilute 10 µL aliquot with 190 µL acetonitrile, transfer to analysis plate

- Data Processing:

- Import analytical results to HTE software

- Generate heatmaps of reaction conversion or yield

- Identify optimal catalyst/base/ligand combinations for further investigation

Notes

- Maintain anhydrous conditions for oxygen- and moisture-sensitive catalysts

- Include control reactions without catalyst, without base, and with known successful conditions

- For air-sensitive chemistry, perform liquid handling in glove box or under inert atmosphere

Protocol 2: Fed-Batch Cultivation in Microtiter Plates

This protocol describes a polymer-based fed-batch system for microbial cultivations, enabling carbon-limited growth conditions mimicking industrial production processes [32].

Materials and Reagents

- Fed-batch microtiter plates (e.g., FeedPlate with silicone-glucose matrix)

- Wilms-MOPS medium or other defined mineral medium

- Vitamin mix (1% v/v)

- Glucose releasing enzyme mix (1% v/v for enzymatic systems)

- Microbial strain (e.g., E. coli, H. polymorpha)

- Antifoam agent (e.g., PPG 2000)

- Permeable sealing films (e.g., AeraSeal)

Equipment

- BioLector micro-fermentation system or similar

- Multichannel pipettes

- Centrifuge with plate adapters

- Sterile workstation or laminar flow hood

Procedure

- Medium Preparation:

- Prepare Wilms-MOPS base medium containing (per liter): 6.98 g (NH4)2SO4, 3 g K2HPO4, 2 g Na2SO4, 41.85 g MOPS (0.2 M), 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O

- Adjust pH to 7.5 with NaOH

- Add 1% (v/v) vitamin mix

- For enzymatic release systems, add 1% (v/v) glucose releasing enzyme mix

Inoculum Preparation:

- Thaw frozen microbial stock and harvest cells by centrifugation (7500 rpm, 5 min)

- Wash with sterile medium to remove residual glycerol

- Resuspend in fresh medium to OD600 = 2.0

Cultivation Setup:

- Dispense 800-1000 µL medium into each well of fed-batch microtiter plate

- Inoculate to initial OD600 = 0.5

- Seal plate with gas-permeable membrane

- Place in BioLector system with controlled humidity (≥85% rH)

Process Monitoring:

- Set monitoring parameters: scattered light (biomass), dissolved oxygen, pH, fluorescence (for recombinant protein)

- Use cycle time of 15 min for all parameters

- Maintain temperature appropriate for microorganism (e.g., 37°C for E. coli)

- Set shaking frequency to 1400 rpm

Process Control:

- Monitor glucose release through periodic offline measurements

- Adjust environmental parameters based on dissolved oxygen trends

- For recombinant protein expression, induce at appropriate growth phase

Analytics:

- Take periodic samples for offline analysis (substrate, metabolites, pH)

- Correlate online signals with offline measurements for calibration

- Determine final product titer and yield

Notes

- The glucose release rate depends on osmotic concentration, pH, and temperature

- Include control wells with turbidity standards and pH buffers for calibration

- For comparative studies, include parallel batch cultivations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTE

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palladium catalysts | Cross-coupling catalyst | Suzuki, Buchwald-Hartwig, C-N couplings | Varying ligand specificity, air sensitivity |

| Phosphine ligands | Modulate catalyst activity/selectivity | Cross-coupling, asymmetric hydrogenation | Air-sensitive, structure-activity relationships |