Partial Validation for Modified Analytical Methods: A Lifecycle Guide for Pharma Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive guide to partial validation for modified analytical methods in pharmaceutical development.

Partial Validation for Modified Analytical Methods: A Lifecycle Guide for Pharma Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to partial validation for modified analytical methods in pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it clarifies when partial validation is required, outlines a risk-based methodology for its execution, and presents strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing regulatory expectations and practical applications, this resource empowers professionals to ensure data integrity and maintain regulatory compliance throughout a method's lifecycle, from foundational concepts to comparative analysis with other validation types.

Understanding Partial Validation: Definitions, Scope, and Regulatory Context

In the lifecycle of an analytical method, modifications are inevitable. Partial validation is the documented process of establishing that a previously fully validated bioanalytical method remains reliable after a modification, without necessitating a complete re-validation [1] [2]. It is a targeted, risk-based assessment that confirms the method's continued suitability for its intended use following specific, often minor, changes.

This guide provides a structured comparison of partial, full, and cross-validation to help researchers and scientists select the appropriate validation pathway.

What is Partial Validation?

Partial validation is defined as the demonstration of assay reliability following a modification of an existing bioanalytical method that has previously been fully validated [1]. It is not a less rigorous process, but a more focused one. The extent of testing is determined by the nature and potential impact of the change, and can range from a single intra-assay precision and accuracy experiment to a nearly full validation [1] [2].

The core principle is a risk-based approach, where the parameters evaluated are selected based on the potential impacts of the modifications on method performance [1].

When is Partial Validation Required?

Common scenarios requiring partial validation include [3] [1] [2]:

- Method transfer between laboratories or analysts.

- Changes in instrumentation or software platforms.

- Changes to sample processing procedures (e.g., a change in extraction volume).

- Modification of the analytical methodology within the same technology (e.g., a minor change in mobile phase pH or composition).

- Extension of the analytical range.

- Changes in the species within the same matrix (e.g., rat plasma to mouse plasma).

- Changes in the matrix within the same species (e.g., human plasma to human urine), though a change in matrix type may sometimes be considered a new method requiring full validation [1].

The table below summarizes the core objectives, typical triggers, and scope of the three main types of method validation.

| Feature | Full Validation | Partial Validation | Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Establish performance characteristics for a new method, proving it is suitable for its intended use [3] [2]. | Confirm reliability after a modification to a fully validated method [1] [2]. | Compare two bioanalytical methods to ensure data comparability [3] [2]. |

| Typical Triggers | - Newly developed method [2]- Adding a metabolite to an assay [2]- New drug entity [3] | - Method transfer [3]- Minor changes in equipment, SOPs, or analysts [3] [1]- Change in sample processing [1] | - Data from >1 lab or method within the same study [2]- Comparing original and revised methods [2]- Different analytical techniques used across studies [2] |

| Scope | Comprehensive assessment of all validation parameters (e.g., specificity, accuracy, precision, LLOQ, linearity, stability, robustness) [3]. | Targeted assessment based on risk. Evaluates only parameters potentially affected by the change (e.g., only precision and accuracy for an analyst change) [1]. | Direct comparison of methods using spiked matrix and/or subject samples to establish equivalence or concordance [3] [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Requirements

The experimental design for each validation type varies significantly in breadth. The following table outlines the key parameters and data requirements based on regulatory guidance and industry best practices.

| Validation Parameter | Full Validation | Partial Validation | Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | Required. Minimum of 5 determinations per 3 concentrations (LLOQ, Low, Mid, High) [2]. | Required for affected parameters. Scope depends on change (e.g., 2 sets over 2 days for chromatographic method transfer) [1]. | Required. Comparison of accuracy and precision profiles between the two methods. |

| Linearity & Range | Required. Minimum of 5 concentrations to establish calibration model [2]. | May be required if the quantitative range is modified. | Required to ensure overlapping ranges of quantitation. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Required. Must demonstrate no interference from blank matrix, metabolites, etc. [2]. | Required if modification could impact interference (e.g., new matrix). | Required to show both methods can differentiate the analyte. |

| Stability | Comprehensive (freeze-thaw, short-term, long-term, post-preparative) [2]. | May be required if storage conditions or sample processing changes. | Not typically a focus, unless stability differences are suspected. |

| Robustness | Evaluated to show method resilience to deliberate variations [3]. | Often a key focus if equipment or reagents are changed. | Not typically assessed. |

| Key Experiment | Complete characterization of the method. | Targeted experiments based on risk assessment of the change. | Co-analysis of a set of samples by both methods. |

Detailed Protocol: Method Transfer as a Partial Validation

A common application of partial validation is the transfer of a chromatographic assay. The Global Bioanalytical Consortium provides specific recommendations for this scenario [1]:

- Objective: To demonstrate that a method performs similarly in a receiving laboratory compared to the originating laboratory.

- Experimental Design:

- A minimum of two sets of accuracy and precision data are generated over a 2-day period.

- Quality Control (QC) samples at the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) must be included.

- QC samples at the upper limit (ULOQ) are not required.

- Experiments like dilution or stability are generally not required unless the environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity) are expected to be an issue.

- Acceptance Criteria: The results must meet pre-defined acceptance criteria for precision and accuracy, demonstrating the method is performing similarly in the new environment [1].

The Validation Lifecycle: A Decision Workflow

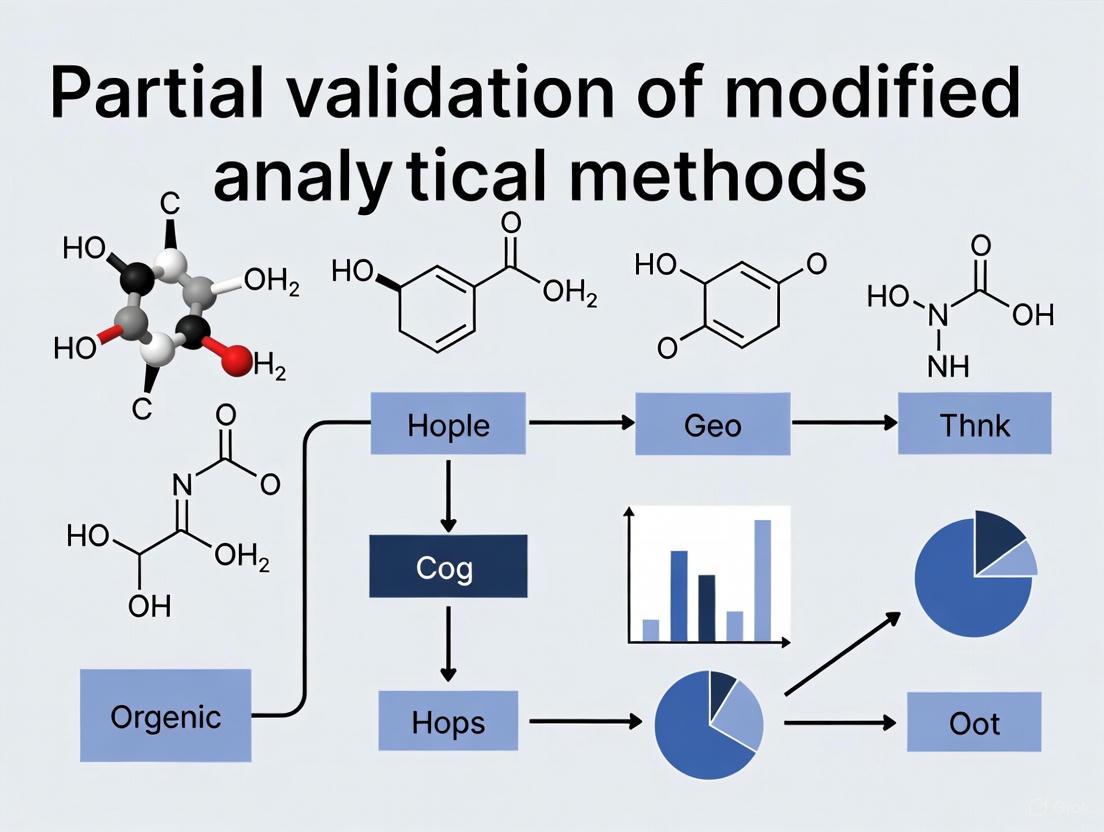

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between different validation activities and the triggers for selecting partial validation over other types.

Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting robust method validation studies, particularly in chromatographic assays.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for identifying the analyte and constructing calibration curves [2]. | Purity and stability are paramount; must be well-characterized and obtained from a certified source. |

| Control Blank Matrix | The biological fluid (e.g., plasma, urine) without the analyte, used to demonstrate specificity [2]. | Must be from the same species and type as the study samples. The absence of interfering components is critical. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Spiked samples at low, mid, and high concentrations within the calibration curve, used to assess accuracy and precision [2]. | Should be prepared independently from calibration standards and used to monitor the performance of each analytical run. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Added to all samples to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response, improving precision [1]. | Ideally used in chromatographic assays (e.g., LC-MS); must demonstrate no interference with the analyte. |

| Mobile Phase Components | The solvent system used to elute the analyte from the chromatographic column [4]. | Composition, pH, and buffer concentration are Critical Method Variables (CMVs) that can affect retention time, peak shape, and resolution [4]. |

| Chromatographic Column | The stationary phase where separation of the analyte from matrix components occurs. | Specifications (e.g., C18, dimensions, particle size) are key method parameters. Reproducibility between columns lots should be assessed for robustness. |

Selecting the correct validation pathway is critical for both regulatory compliance and scientific integrity. Full validation is the foundation for any new method. Partial validation is a flexible, risk-based tool for managing the inevitable evolution of a method post-validation, ensuring continued reliability while conserving resources. Cross-validation is the specific process for bridging data when multiple methods or laboratories are involved. Understanding these distinctions allows drug development professionals to build a efficient and compliant analytical lifecycle, ensuring that data quality is maintained from development through to routine application.

In the rigorous landscape of pharmaceutical development, the traditional approach to analytical method validation has been a comprehensive, one-time event conducted before a method's implementation. However, this static model is increasingly misaligned with the dynamic needs of modern drug development, where methods must evolve in response to new formulations, patient populations, and manufacturing processes. Partial validation represents a paradigm shift toward a more flexible, risk-based approach where specific method parameters are re-evaluated when method conditions change, rather than performing full revalidation. This strategy is embedded within a broader continuous improvement framework, enabling organizations to maintain methodological rigor while accelerating development timelines and reducing costs.

The concept of partial validation is particularly crucial within Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) approaches, where quantitative models are iteratively refined as new data emerges. These models, which include population pharmacokinetics (popPK), physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, and exposure-response modeling, rely on a foundation of analytically valid measurements that remain fit-for-purpose throughout the drug development lifecycle. As noted by regulatory scientists, MIDD approaches "allow an integration of information obtained from non-clinical studies and clinical trials in a drug development program" and enable more informed decision-making while reducing uncertainty [5]. Partial validation provides the mechanism through which the analytical methods supporting these models can adapt efficiently to expanding data sources and evolving clinical contexts.

Theoretical Framework: Partial Validation in Continuous Improvement Cycles

The Method Lifecycle and Validation Triggers

The method lifecycle extends far beyond initial validation, encompassing development, implementation, monitoring, and iterative improvement. Within this continuum, partial validation serves as a targeted mechanism for ensuring ongoing method reliability when specific, predefined changes occur. Unlike full validation, which verifies all performance parameters, partial validation focuses only on those parameters likely to be affected by a given modification, making it both resource-efficient and scientifically appropriate.

Key triggers for partial validation include:

- Transfer of methods between laboratories or sites

- Changes in methodology or instrumentation

- Updates to drug formulation or composition

- Expansion to new patient populations or matrices

- Evolution of regulatory requirements or standards

- Implementation of new software or algorithms for data analysis

The foundation for partial validation lies in risk-based decision making, where the scope of revalidation is determined by assessing the potential impact of changes on method performance. This approach aligns with the principles of Lean Sigma methodology, which has been successfully deployed across drug discovery value chains to deliver "incremental and transformational improvement in product quality, delivery time and cost" [6]. By applying these principles to analytical method management, organizations can eliminate wasteful comprehensive revalidation when targeted assessment would suffice.

Integration with Continuous Improvement Philosophies

Partial validation operates as a critical enabler of continuous improvement in analytical science, providing the mechanism through which methods can evolve without compromising quality. In the context of pharmaceutical R&D, continuous improvement programs focus on "increasing clinical proof-of-concept (PoC) success and the speed of candidate drug (CD) delivery" [6]. Analytical methods must keep pace with this accelerated timeline while maintaining reliability.

The integration occurs through:

- Iterative Method Enhancement: Systematic gathering of method performance data during routine use identifies opportunities for refinement, with partial validation confirming improvements maintain reliability.

- Knowledge Management: Documenting partial validation outcomes builds institutional understanding of method robustness and critical parameters.

- Reduced Method Lifecycle Costs: Targeted validation activities conserve resources compared to full revalidation, freeing capacity for innovation.

- Adaptive Compliance Strategies: Partial validation provides a structured approach to maintaining regulatory compliance while implementing method improvements.

This integrated approach is particularly valuable when deploying artificial intelligence and machine learning in drug discovery, where models require continuous refinement based on new data. As noted in industry assessments of AI in drug discovery, establishing "clear and measurable KPIs to track progress and evaluate the effectiveness of research efforts" is essential for continuous improvement [7]. Partial validation of the analytical methods that generate training data for these AI models ensures their ongoing reliability as the models evolve.

Comparative Analysis: Partial Validation vs. Traditional Approaches

Performance Metrics Comparison

The strategic implementation of partial validation offers significant advantages across multiple performance dimensions compared to traditional full validation approaches. These benefits extend beyond mere cost reduction to impact timelines, resource allocation, and methodological agility.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches in the Method Lifecycle

| Performance Metric | Traditional Full Validation | Partial Validation Approach | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Timeline | 4-8 weeks (all parameters) | 1-3 weeks (targeted parameters) | 50-75% reduction in validation time |

| Resource Requirements | High (cross-functional team, extensive testing) | Moderate (focused team, selective testing) | 40-60% reduction in resource utilization |

| Method Agility | Low (resistant to change due to revalidation burden) | High (structured approach to method evolution) | Enables rapid method adaptation |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Limited (fixed validation package) | Adaptable (risk-based documentation) | Better alignment with QbD principles |

| Cost Implications | $50,000-100,000 per full validation | $15,000-30,000 per partial validation | 60-70% cost reduction per change |

| Knowledge Management | Static validation package | Growing understanding of critical parameters | Enhanced method robustness understanding |

Impact on Drug Development Timelines

The cumulative effect of partial validation implementation across the drug development lifecycle can substantially accelerate overall development programs. With the average drug development process taking 10-15 years [8], efficiency gains in analytical method management contribute to reducing this timeline.

In practice, a typical drug development program may require 15-25 significant method modifications throughout its lifecycle. Under a traditional validation approach, these changes would trigger full revalidation, consuming approximately 18-48 months of cumulative validation time. Through partial validation, this timeline can be reduced to 6-18 months, representing a potential saving of 1-2.5 years in overall development time. These efficiencies are particularly valuable in the clinical research phase, where approximately 25-30% of phase III studies ultimately receive regulatory approval [8], making speed and adaptability critical competitive advantages.

The application of partial validation principles extends beyond conventional small molecules to complex modalities like biologics and cell and gene therapies, where "the potential for future application of MIDD include understanding and quantitative evaluation of information related to biological activity/pharmacodynamics, cell expansion/persistence, transgene expression, immune response, safety, and efficacy" [5]. As these innovative therapies require increasingly sophisticated analytical methods, partial validation provides a pathway for method evolution without excessive regulatory burden.

Experimental Protocols for Partial Validation Studies

Protocol Design Principles

Designing scientifically sound partial validation studies requires careful consideration of the specific method changes being implemented and their potential impact on method performance. The foundational principle is risk-based scope determination, where the extent of validation is proportional to the significance of the method modification. This approach aligns with the experimental medicine approach discussed in neuroscience drug development, which employs an "iterative process of testing specific mechanistic hypotheses" [9].

Key design considerations include:

- Change Impact Assessment: Systematic evaluation of how method modifications might affect different validation parameters.

- Parameter Selection: Identification of specific validation parameters (accuracy, precision, specificity, etc.) that require re-evaluation based on the change.

- Acceptance Criteria Definition: Establishment of predefined criteria for each parameter based on method requirements and regulatory expectations.

- Statistical Power: Appropriate sample size determination to ensure sufficient power to detect clinically or analytically significant changes.

- Comparative Testing: Inclusion of original method conditions alongside modified conditions to facilitate direct comparison.

These design principles support the continuous improvement philosophy by creating a structured framework for method evolution. As described in evaluations of Lean Sigma in drug discovery, successful implementation requires "distinguishing 'desirable' and 'undesirable' variability because variability in research can be a source of innovation" [6]. Partial validation protocols must similarly distinguish between meaningful changes in method performance and acceptable variation.

Specific Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Instrumentation Platform Transfer

Objective: Validate method performance after transfer to a new instrument platform while maintaining original method parameters.

Experimental Design:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare three concentration levels (QC low, medium, high) covering the calibration range (n=6 each).

- Analysis Sequence: Analyze in random order across original and new instrumentation.

- Comparison Approach: Use statistical equivalence testing with pre-defined equivalence margins (±15% for accuracy, ≤15% RSD for precision).

- Data Analysis: Calculate between-instrument difference in accuracy and precision using appropriate statistical methods.

Acceptance Criteria: No statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in accuracy or precision between platforms; all QC samples within ±15% of nominal concentration.

Protocol for Sample Matrix Expansion

Objective: Validate method performance when extending an established method to a new patient population with potentially different matrix composition.

Experimental Design:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare QC samples in original and new matrices (n=6 each at three concentrations).

- Selectivity Assessment: Analyze individual matrix lots from at least 6 different sources.

- Matrix Effect Evaluation: Use post-column infusion to assess ionization suppression/enhancement.

- Stability Assessment: Evaluate stability in new matrix under relevant storage conditions.

Acceptance Criteria: Accuracy and precision within ±15% (±20% at LLOQ) of nominal values; no significant matrix effect; selectivity demonstrated across all individual matrix lots.

Case Studies: Partial Validation in Drug Development Applications

Case Study 1: Model-Informed Drug Development

The application of partial validation is particularly evident in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), where models are continuously refined as new clinical data becomes available. In one documented case, MIDD approaches were used to support the approval of a new dosing regimen for paliperidone palmitate without additional clinical trials. The approach utilized "popPK modeling and simulation to support approval of a loading dose, dosing window, re-initiation strategy and dosage adjustment in patient subgroups" [5].

The analytical methods supporting the popPK model underwent partial validation when:

- The model was expanded to new patient subpopulations

- Additional metabolic pathways were incorporated

- The model was adapted to support a new dosing regimen

In each case, partial validation focused specifically on parameters affected by these changes, such as model precision at new concentration ranges or selectivity in the presence of new metabolites. This approach enabled continuous model refinement while maintaining regulatory confidence, ultimately supporting "regulatory decision-making and policy development" [5]. The success of this case highlights how partial validation of supporting analytical methods enables the application of MIDD approaches across the drug development lifecycle.

Case Study 2: Continuous Improvement in Oncology Drug Discovery

AstraZeneca's deployment of a continuous improvement program across its oncology drug discovery value chain provides another compelling case study. The program utilized Lean Sigma methodology to increase "clinical proof-of-concept (PoC) success and the speed of candidate drug (CD) delivery" [6]. Analytical method management was identified as a critical component of this initiative.

Key outcomes included:

- Reduced Method Qualification Time: Implementation of partial validation strategies reduced average method qualification time by 45% when methods were transferred between research sites.

- Enhanced Method Portability: Standardized partial validation protocols enabled more efficient method transfer between discovery and development teams.

- Accelerated Candidate Selection: Robust yet flexible analytical methods allowed for more rapid comparison of candidate compounds against critical quality attributes.

The program succeeded by focusing on "process, project and strategic" levels of the drug discovery value chain [6], with partial validation serving as a key enabler at the process level. This case demonstrates how partial validation integrates with broader continuous improvement initiatives to enhance R&D productivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing effective partial validation strategies requires carefully selected reagents, reference standards, and analytical materials. These tools ensure validation studies accurately assess method performance while maintaining efficiency and regulatory compliance.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Partial Validation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Partial Validation | Critical Quality Attributes | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic Reference Standards | Quantification and method calibration | Purity, stability, structural confirmation | Potency determination, method calibration |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization of analytical variability | Isotopic purity, chemical stability | Mass spectrometry-based assays |

| Matrix Blank Solutions | Assessment of selectivity and specificity | Matrix composition, absence of interferents | Selectivity verification in new populations |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring method performance | Stability, homogeneity, commutability | Accuracy and precision assessment |

| System Suitability Solutions | Verification of instrument performance | Retention characteristics, peak shape | System performance monitoring |

| Extraction Solvents & Reagents | Sample preparation procedural consistency | Purity, composition, lot-to-lot consistency | Extraction efficiency studies |

The selection and qualification of these materials should be proportionate to their intended use in partial validation studies. For example, when expanding a method to a new matrix, particular attention should be paid to sourcing representative matrix materials from appropriate populations. This approach aligns with the growing emphasis on diversity in clinical research [8], ensuring analytical methods remain valid across diverse patient populations.

Visualization of Method Lifecycle and Partial Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous improvement cycle for analytical methods, highlighting decision points for partial validation within the method lifecycle.

Method Lifecycle and Validation Decision Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the risk-based decision making central to partial validation strategies. Changes trigger assessment of potential impact on method performance, with the validation response proportionate to the risk. This approach ensures efficient resource utilization while maintaining methodological integrity.

Statistical Approaches for Partial Validation Data Analysis

Method Comparison Techniques

Statistical analysis of partial validation data focuses on demonstrating equivalence between the original and modified method conditions. Appropriate statistical methods vary based on the validation parameter being assessed and the nature of the method change.

Table 3: Statistical Methods for Partial Validation Data Analysis

| Validation Parameter | Recommended Statistical Methods | Equivalence Criteria | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Equivalence testing (TOST), Bland-Altman analysis | ±15% of nominal value (±20% at LLOQ) | 3 concentrations, n≥5 replicates |

| Precision | F-test for variance comparison, ANOVA | RSD ≤15% (≤20% at LLOQ) | 3 concentrations, n≥6 replicates |

| Selectivity | Hypothesis testing for interference | No significant interference (p<0.05) | 6 individual matrix sources |

| Linearity | Weighted regression, lack-of-fit test | R² ≥0.99, residuals ≤15% | 5-8 concentration levels |

| Robustness | Experimental design (DoE), ANOVA | No significant effect (p<0.05) | Deliberate variations |

These statistical approaches enable objective assessment of whether method modifications have significantly impacted performance. The use of equivalence testing is particularly important, as it directly tests the hypothesis that method performance remains equivalent within predefined acceptance limits, rather than merely failing to find a difference as with traditional hypothesis testing.

Integration with Analytical Validation Frameworks

The statistical approaches for partial validation align with broader analytical validation frameworks being developed for novel measurement technologies. For example, in the validation of sensor-based digital health technologies (sDHTs), researchers have evaluated multiple statistical methods including "the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) between DM and RM, simple linear regression (SLR) between DM and RM, multiple linear regression (MLR) between DMs and combinations of RMs, and 2-factor, correlated-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models" [10].

These approaches can be adapted to partial validation of traditional analytical methods, particularly when dealing with:

- Complex method modifications affecting multiple parameters simultaneously

- Multivariate data requiring advanced modeling techniques

- Method harmonization across multiple sites or platforms

The findings from digital health validation research suggest that "CFA to assess the relationship between a novel DM and a COA RM" [10] may be applicable to analytical method validation when establishing equivalence between original and modified method conditions.

Partial validation represents a sophisticated, risk-based approach to analytical method management that aligns with continuous improvement philosophies in pharmaceutical development. By enabling targeted, efficient method evolution while maintaining regulatory compliance, partial validation strategies directly address the industry's need for greater efficiency and adaptability. When implemented within a structured framework with appropriate statistical support, partial validation reduces development costs and timelines while enhancing method understanding and robustness.

The integration of partial validation with emerging approaches like Model-Informed Drug Development and digital health technologies creates opportunities for further optimization of the method lifecycle. As drug development continues to evolve toward more personalized medicines and complex therapeutic modalities, the flexible, science-driven principles of partial validation will become increasingly essential for maintaining analytical excellence while supporting innovation.

In the pharmaceutical industry, analytical methods are developed and validated to ensure the identity, potency, purity, and performance of drug substances and products. The lifecycle of an analytical procedure naturally requires modifications over time due to factors such as changes in the synthesis of the drug substance, composition of the finished product, or the analytical procedure itself [11]. When such changes occur, revalidation is necessary to ensure the method remains suitable for its intended purpose. The extent of this revalidation—often termed partial validation—depends on the nature of the changes [11]. Global regulatory bodies, including the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), provide the foundational guidelines that govern these modification processes. A thorough understanding of these drivers is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to maintain regulatory compliance and ensure the continued reliability of analytical data throughout a product's lifecycle.

Comparative Analysis of ICH, FDA, and USP Guidelines

The regulatory frameworks provided by ICH, FDA, and USP, while aligned in their overall goal of ensuring data quality, exhibit differences in terminology, structure, and specific requirements. The following table provides a high-level comparison of these key regulatory bodies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Regulatory Bodies for Analytical Methods

| Regulatory Body | Primary Role & Scope | Key Guidance Documents | Regulatory Standing |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) | Develops international technical guidelines for the pharmaceutical industry to ensure safety, efficacy, and quality [12] [13]. | ICH Q2(R2) Validation of Analytical Procedures [12]; ICH Q14 Analytical Procedure Development [13]. | Provides harmonized standards; adopted by regulatory agencies (e.g., FDA, EMA). |

| US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | US regulatory agency that enforces laws and issues binding regulations and non-binding guidance for drug approval and marketing [14]. | Adopts and enforces ICH guidelines (e.g., Q2(R2)) [12]; Issues FDA-specific guidance documents. | Has legal authority; requirements are mandatory for market approval in the US. |

| United States Pharmacopeia (USP) | Independent, scientific organization that sets public compendial standards for medicines and their ingredients [15] [16]. | General Chapters: <1220> Analytical Procedure Lifecycle [16], <1225> Validation of Compendial Procedures [11]. | Recognized in legislation (Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act); standards are legally enforceable. |

Detailed Comparison of Validation Parameters and Terminology

A critical aspect for scientists is navigating the specific validation characteristics required by different guidelines. The following table compares the parameters as outlined by ICH, FDA, and USP, which is crucial for planning any method modification and subsequent partial validation.

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Validation Parameters Across Guidelines

| Validation Characteristic | ICH Q2(R2) Perspective [17] [14] | FDA Perspective (aligned with ICH Q2(R2)) [14] | USP Perspective (General Chapters <1225>, <1220>) [18] [17] [16] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between accepted reference value and value found. | Evaluated across the method range; recovery studies of known quantities in sample matrix are typical [14]. | Closeness of agreement between the value accepted as a true value and the value found [11]. |

| Precision | Includes Repeatability, Intermediate Precision, and Reproducibility [17] [11]. | Primarily unchanged; includes repeatability and intermediate precision. For multivariate methods, uses metrics like RMSEP [14]. | Expressed as standard deviation or relative standard deviation; includes concepts of ruggedness [18] [11]. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential impurities [11]. | Specificity/Selectivity must show absence of interference. Specific technologies (e.g., NMR, MS) may justify reduced testing [14]. | Original term used is "Specificity"; also uses "Selectivity" to characterize methods [17]. |

| Linearity & Range | The range must be established to cover the intended application (e.g., 80-120% for assay) [17]. | Range must cover specification limits. Now explicitly includes non-linear responses (e.g., S-shaped curves in immunoassays) [14]. | The interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with precision, accuracy, and linearity [18]. |

| Detection Limit (LOD) / Quantitation Limit (LOQ) | LOD: S/N ≈ 3:1; LOQ: S/N ≈ 10:1 [17]. | Should be established if measuring analyte close to the lower range limit (e.g., for impurities) [14]. | LOD: Lowest concentration that can be detected; LOQ: Lowest concentration that can be quantified [18]. |

| Robustness | Considered part of precision under ICH [17]. | Emphasis shifted to method development; should show reliability against deliberate parameter variations [14]. | Evaluated separately; capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [18] [17]. |

| System Suitability | Treated as part of method validation [18]. | Incorporated into method development; acceptance criteria must be defined [14]. | Dealt with in a separate chapter (<621>); tests to verify system performance before/during analysis [18] [17]. |

Regulatory Framework for Method Modifications and Partial Validation

The guidelines implicitly and explicitly address the need for revalidation when an analytical procedure is modified. The core principle is that the extent of validation should be commensurate with the level of change and the risk it poses to the method's performance [11] [16]. The ICH Q14 guideline on analytical procedure development, together with USP's <1220> on the analytical procedure lifecycle, promote a science- and risk-based approach to managing changes throughout a method's life [13] [16]. This involves having a deep understanding of the method, its limitations, and its controlled state, which forms the basis for justifying the scope of partial validation.

Protocol for Partial Validation of a Modified HPLC Method

The following workflow outlines a generalized experimental protocol for assessing a modified analytical method, focusing on the key parameters that typically require verification. This protocol is based on the regulatory expectations synthesized from the ICH, FDA, and USP guidelines.

Diagram 1: Partial validation workflow for a modified analytical method.

Step 1: Risk Assessment and Scoping of Partial Validation

Before any laboratory work, a cross-functional team should be formed to assess the impact of the change [18]. The team, including members from analytical development, quality control, and regulatory affairs, defines the purpose and scope of the partial validation [18]. The risk assessment should answer:

- What critical method attributes (CMAs) are potentially affected by the change?

- What is the intended use of the method and the potential impact on product quality?

- Which validation parameters need to be re-evaluated to guarantee continued method fitness for purpose?

The output of this step is a partial validation protocol with pre-defined acceptance criteria based on method development data and original validation data [18] [11].

Step 2: Experimental Setup and Pre-Validation

- Instrument Qualification: Ensure the HPLC system has current Installation Qualification (IQ), Operational Qualification (OQ), and Performance Qualification (PQ). PQ testing should be conducted under actual running conditions using a well-characterized analyte mixture [18].

- System Suitability Test (SST): Before initiating validation experiments, establish that the system and procedure provide data of acceptable quality. Parameters like plate count, tailing factors, and resolution are determined and compared against method specifications [18]. A typical SST recommendation includes a Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of ≤1% for peak areas for N≥5 injections, and a resolution (Rs) of ≥2 between the peak of interest and the closest eluting potential interference [18].

- Solution Stability: Determine the stability of sample and standard solutions prior to validation. For assay methods, a change of ≤2% in standard or sample response after 24 hours under defined storage conditions is often acceptable [18].

Step 3: Execution of Critical Validation Experiments

The specific experiments are dictated by the risk assessment. The following are typical for a method modification:

- Specificity/Selectivity: Demonstrate that the method is still able to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferences (e.g., impurities, degradants, matrix). For a modified method, this typically involves analyzing stressed samples (e.g., forced degradation) and comparing the chromatogram to that of a fresh standard to ensure the analyte peak is still pure and free from interference [11] [14].

- Precision (Repeatability): Expresses the precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [17]. The methodology involves preparing and analyzing six determinations at 100% of the test concentration or nine determinations covering the specified range [17]. The results are expressed as %RSD, with an RSD of ≤1% often considered desirable for the assay of a drug product [18].

- Accuracy: Demonstrates the closeness of agreement between the value found and the accepted reference value [11]. The typical methodology is a recovery study, where a known amount of analyte is spiked into the sample matrix. The experiment is performed in triplicate at three different concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120%) covering the range of the procedure [14]. The mean recovery is calculated at each level, with acceptable criteria often being 98.0–102.0% recovery for the drug substance assay.

- Linearity and Range: The range of an analytical procedure is the interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [11]. To test this, a series of solutions are prepared from independent weighings, typically from 80% to 120% of the test concentration for an assay. The response is plotted against concentration, and the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line are calculated. A correlation coefficient (r) of ≥0.998 is a common acceptance criterion [18] [14].

Table 3: Example Acceptance Criteria for Partial Validation of a Drug Product Assay Method

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Procedure | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Chromatographic comparison of stressed sample vs. standard. | Analyte peak is pure and free from co-elution (e.g., peak purity index passes). |

| Repeatability (Precision) | Six replicate preparations of a homogeneous sample. | %RSD of peak areas ≤ 1.0% [18]. |

| Accuracy | Spike/recovery in triplicate at 80%, 100%, 120% of target. | Mean recovery 98.0–102.0% at each level. |

| Linearity | Minimum of 5 concentrations from 80% to 120% of target. | Correlation coefficient (r) ≥ 0.998 [18]. |

| Range | Established by successful accuracy and linearity results. | Encompasses 80% to 120% of test concentration [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of a partial validation study relies on high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details key items essential for the experiments described in the protocol.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Validation

| Item | Function & Importance in Validation |

|---|---|

| Drug Substance (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient - API) Reference Standard | Serves as the primary benchmark for identity, potency, and purity. Its certified and well-characterized nature is critical for accurate and precise results [18]. |

| Drug Product (Placebo and Formulated Product) | The placebo (excipients only) is vital for specificity/selectivity testing to demonstrate no interference. The formulated product is the actual sample for accuracy and precision studies. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents & Reagents | High-purity solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) and reagents (e.g., buffer salts) are essential for generating reproducible chromatography, preventing ghost peaks, and ensuring baseline stability. |

| Characterized HPLC Column | The column is the heart of the separation. Using a column with documented performance and from the same supplier/chemistry specified in the method is crucial for maintaining selectivity and resolution. |

| Volumetric Glassware (Class A) | Precise and accurate solution preparation is foundational to all quantitative analysis. Class A volumetric flasks and pipettes are required to minimize errors in concentration. |

| Stable Sample & Standard Solutions | Solutions must be stable for the duration of the analytical run. Pre-validation stability testing ensures that results are not compromised by degradation over time, especially for automated runs [18]. |

Navigating the regulatory drivers for modifying analytical methods requires a structured, science-based approach. The ICH, FDA, and USP guidelines, particularly with the recent adoption of ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, provide a harmonized yet flexible framework. The core principle is that the extent of validation—be it full or partial—must be justified based on a rigorous risk assessment of the change. The experimental protocols for partial validation, focusing on parameters like specificity, accuracy, and precision, provide a pathway to demonstrate that the modified method remains fit for its intended purpose. By understanding the comparative requirements of these key regulatory bodies and implementing a systematic partial validation workflow, drug development professionals can ensure robust, compliant, and reliable analytical methods throughout the product lifecycle, thereby safeguarding product quality and patient safety.

In the lifecycle of an analytical method, changes are inevitable. Effectively managing these changes through appropriate validation strategies is crucial for maintaining regulatory compliance and data integrity in pharmaceutical development. This guide compares the triggers and requirements for partial validation against those necessitating full revalidation, providing a structured framework for decision-making.

Defining Validation Types and Their Scope

Before identifying triggers, it is essential to understand the fundamental differences between a full validation and a partial validation.

Full Validation is required for new methods or when major changes to an existing method affect the scope or critical components of the procedure. It involves a comprehensive assessment of all relevant validation parameters to establish that the method is suitable for its intended use [3]. According to regulatory guidelines, any method used to produce data in support of regulatory filings must be validated [3].

Partial Validation is performed on a previously-validated method that has undergone a minor modification. It involves a subset of the validation tests, selected based on the potential effects of the new changes on method performance and data integrity. Fewer validation tests are generally needed compared to a full validation [3].

Re-validation is the process required when a previously-validated method undergoes changes sufficient to merit further validation activities. This can be full or partial, driven by the extent of the method changes [3].

The following table summarizes the core concepts and their applications.

| Validation Type | Objective | Typical Scope | Documentation Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Validation | Establish that a new method is suitable for its intended use [3]. | All validation parameters (e.g., specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, robustness) [3]. | Extensive protocol and summary report. |

| Partial Validation | Demonstrate a modified method remains valid after minor changes [3]. | A subset of parameters potentially impacted by the change (e.g., precision and accuracy only). | Supplement to the original validation report. |

| Full Re-validation | Re-establish method suitability after major changes or due to cumulative drift [3] [19]. | Full or nearly full suite of validation parameters, mirroring a new validation. | New, comprehensive protocol and report. |

Triggers for Partial vs. Full Revalidation

The decision to perform a partial or full revalidation is risk-based, centered on the potential impact of a change on the method's critical performance attributes.

Triggers for Partial Validation

Partial validation is appropriate for minor modifications where the core principles of the method remain unchanged. The experiments are selected based on the potential effects of the changes [3]. Common triggers include:

- Changes in equipment (e.g., same model from a different manufacturer, or a newer model of the same brand with confirmed similar operating principles) [3].

- Changes in solution composition (e.g., minor adjustments to buffer pH or molarity within a range that does not alter the method's mechanism) [3].

- Changes in quantitation range (e.g., extending the calibration range upwards or downwards without altering the core chemistry) [3].

- Changes in sample preparation (e.g., minor modifications to vortexing time, centrifugation speed, or dilution schemes) [3].

- Transfer of a validated method to a different laboratory site, where comparative testing or a co-validation approach may be used [3].

Triggers for Full Re-validation

Full re-validation is required when changes are substantial enough to potentially affect the fundamental identity or performance of the method. According to regulatory expectations, this is needed for "new methods or when major changes to an existing method affect the scope or critical components" [3]. Specific triggers include:

- A change in the method's fundamental principle (e.g., switching from a UV to a fluorescence detection method) [3].

- A change in the sample matrix (e.g., switching from plasma to serum analysis, or adding new analytes to a panel) which can alter selectivity and accuracy [3] [19].

- Major alterations to critical method parameters that define the method's operation and performance [3].

- Changes sufficient to merit further validation activities and documentation, often determined through a formal risk assessment [3].

- Existing processes that have been modified, expanded, experienced a downward trend in performance, or seen an increase in customer complaints [20].

Decision Workflow for Validation Strategy

The following diagram maps the logical decision process for determining the appropriate validation pathway after a change to an analytical method.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Studies

When executing partial or full revalidation, the experiments must be designed to challenge the specific parameters most likely to be impacted by the change.

Protocol 1: Assessing Precision and Accuracy for a Minor Sample Prep Change

This protocol is typical for a partial validation when adjusting a sample preparation step.

- 1. Objective: To demonstrate that a change in vortexing time during sample extraction does not adversely affect the method's precision and accuracy.

- 2. Experimental Design:

- Prepare a minimum of five (5) replicates each at three concentration levels (QCL, MQC, HQC) covering the analytical range [3].

- Use the revised sample preparation procedure (new vortexing time) alongside the current, validated procedure for comparison.

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) for the replicates at each QC level to establish precision. The acceptance criteria are typically ≤15% RSD.

- Calculate the % Nominal (measured concentration/ theoretical concentration * 100) for each QC level to establish accuracy. The acceptance criteria are typically within ±15% of the nominal value.

- 4. Acceptance Criteria: The results obtained with the modified procedure must meet pre-defined acceptance criteria for precision and accuracy and be comparable to the original procedure.

Protocol 2: Establishing Specificity and Linearity for a New Sample Matrix

This is a core component of a full revalidation, required when adapting a method for use with a new biological fluid (e.g., from plasma to urine).

- 1. Objective: To prove that the method can unequivocally quantify the analyte in the presence of potential interferents in the new matrix and that the response is linear across the required range.

- 2. Experimental Design:

- Specificity: Analyze at least six independent sources of the blank new matrix. Analyze blank matrix spiked with the analyte at the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ). The response in blank matrix at the retention time of the analyte should be <20% of the LLOQ response, and the response for the LLOQ should have a precision of ≤20% RSD and accuracy of 80-120% [3].

- Linearity: Prepare and analyze a minimum of six to eight non-zero calibrators covering the entire range (e.g., from LLOQ to ULOQ). The calibration curve is typically constructed using a weighted linear regression model [3].

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Specificity: Visually inspect chromatograms for interfering peaks and calculate the signal-to-noise ratio at the LLOQ.

- Linearity: The correlation coefficient (r) is calculated, and the back-calculated concentrations of the calibrators should be within ±15% of nominal (±20% at LLOQ).

- 4. Acceptance Criteria: The method is specific if no significant interference is observed. The linearity is accepted if the r value is ≥0.99 (or as per predefined criteria) and the % bias for calibrators is within the acceptable range.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation relies on high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in validation experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for identifying the analyte and constructing calibration curves for quantitative tests [3]. | Certified purity and identity, stability under storage conditions, proper documentation (e.g., Certificate of Analysis). |

| Blank Matrix | Used to prepare calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples to assess specificity, accuracy, and precision [3]. | Must be free of the target analyte and potential interferents; representative of the actual study samples. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Added to all samples to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response, improving precision and accuracy [3]. | High isotopic purity, co-elution with the analyte, and absence of chemical interference. |

| Mobile Phase & Buffer Components | Create the chromatographic environment that separates the analyte from interferents; critical for robustness testing [3]. | HPLC-grade or higher purity; specified pH and molarity; prepared with strict adherence to the method's SOP. |

| System Suitability Test Solutions | Used to verify that the chromatographic system is performing adequately before and during the validation runs [3]. | A stable mixture of key analytes that produces a defined response (e.g., retention time, peak shape, resolution). |

Navigating the triggers for partial validation versus full revalidation is a critical skill in pharmaceutical R&D. The core differentiator is the impact of the change on the method's fundamental operating conditions and performance. Minor, well-understood changes to equipment, reagents, or sample preparation within the original scope typically warrant a targeted partial validation. In contrast, changes that alter the method's principle, scope, or sample matrix necessitate a full revalidation. A risk-based assessment, following a structured decision tree, provides a defensible and scientifically sound strategy for ensuring analytical methods remain validated, compliant, and capable of generating reliable data throughout their lifecycle.

Risk-based validation has emerged as a critical paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development, displacing traditional one-size-fits-all approaches with targeted, scientifically-driven strategies. This framework enables researchers to allocate validation resources precisely where they have the greatest impact on product quality and patient safety. By integrating principles from ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management and standards like ASTM E2500, organizations can develop proportional validation strategies that focus on the most critical process parameters and analytical methods while maintaining regulatory compliance. This guide compares traditional versus risk-based validation approaches, provides experimental methodologies for implementation, and illustrates how this framework applies specifically to partial validation of modified analytical methods.

Risk-based validation represents a fundamental shift in how pharmaceutical companies approach process and analytical method validation. Instead of applying uniform validation efforts across all systems and methods, a risk-based approach targets resources toward elements with the greatest potential impact on product quality and patient safety [21] [22]. This strategy is supported by major regulatory frameworks including the FDA's "Pharmaceutical cGMPs for the 21st Century: A Risk-Based Approach" and ICH Q9 guidelines [21] [22].

The core principle involves establishing documented evidence that provides a high degree of assurance that a specific process will consistently produce a product meeting its predetermined specifications and quality attributes [21]. When applied to analytical methods, this means focusing validation activities on method characteristics and changes that pose the highest risk to data integrity and reliability. For partial validation of modified methods, the risk-based framework provides a logical structure for determining the extent of revalidation required based on the nature and significance of the modification [1] [2].

Traditional vs. Risk-Based Validation: A Comparative Analysis

The evolution from traditional to risk-based validation represents a significant advancement in validation efficiency and effectiveness. The table below compares these approaches across key dimensions:

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional vs. Risk-Based Validation Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Validation | Risk-Based Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Scope | Uniform testing of all functions regardless of criticality [23] | Testing scaled to system/function criticality [23] |

| Documentation Approach | Extensive, volume-driven documentation [23] | Focused, risk-justified documentation [23] |

| Testing Strategy | Exhaustive scripted testing of all features [22] [23] | Proportional scripted/exploratory testing based on risk priority [22] [23] |

| Resource Utilization | High cost with long validation timelines [23] | Optimized effort with shorter cycles [23] |

| Decision Basis | Compliance-driven without explicit risk rationale [23] | Science-based with documented risk assessments [21] [22] |

| Regulatory Alignment | Meets minimum compliance requirements [23] | Fully aligned with ICH Q9, ASTM E2500, and FDA guidance [21] [22] [23] |

| Change Management | Rigid, requiring full revalidation for most changes [1] | Flexible, allowing partial validation based on risk impact [1] [2] |

Core Components of the Risk-Based Validation Framework

Fundamental Principles

The risk-based validation framework rests on three essential elements: risk must be formally identified and quantified, effective control measures must be implemented to reduce risk to acceptable levels, and validation must be performed to a level commensurate with the risk [22]. This approach begins with the specification and design process and continues through verification of manufacturing systems and equipment that potentially affect product quality and patient safety [22].

The framework follows a systematic process flow based on ICH Q9 guidelines, comprising four major components: risk assessment, risk control, risk communication, and risk review [21]. This process provides a rational structure for developing an appropriate scope for validation activities, focusing on processes that have the greatest potential risk to product quality [21].

Risk Assessment Methodology

Risk assessment forms the foundation of the framework and involves risk identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation [21] [23]. For process validation, this typically uses inductive risk analysis tools that look forward in time to answer "What would happen if this failure occurred?" [21]

The selection of specific risk assessment tools depends on the process knowledge and available data. Well-defined processes with extensive characterization data benefit from detailed tools like Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), while less-defined processes may require higher-level tools like Preliminary Hazard Analysis [21].

Table 2: Risk Assessment Methods for Validation Scoping

| Method | Focus | Scoring Approach | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Risk Assessment (FRA) | Function impact on GxP processes [23] | High/Medium/Low classification [23] | Initial system assessment and User Requirement Specification (URS) development [23] |

| Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) | Potential failures and their prioritization [21] [23] | Risk Priority Number (RPN) = Severity × Occurrence × Detection [21] [23] | Complex systems requiring detailed failure analysis [21] |

| Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) | Hazards and critical control points [23] | Identification of critical points [23] | Data integrity and cybersecurity risks [23] |

Implementation Workflow for Risk-Based Validation

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for implementing risk-based validation:

Application to Partial Validation of Modified Analytical Methods

Defining Partial Validation Scope

Partial validation is defined as "the demonstration of assay reliability following a modification of an existing bioanalytical method that has previously been fully validated" [1]. The extent of validation required depends directly on the nature and risk level of the modification [1] [2].

The risk-based framework provides a logical approach to determining the appropriate scope of partial validation activities. Changes are evaluated based on their potential impact on method performance and the resulting risk to data quality [1]. This ensures that sufficient but not excessive validation is performed, optimizing resource utilization while maintaining data integrity.

Risk Assessment for Method Modifications

The risk assessment for analytical method modifications should evaluate both the significance of the change and its potential impact on critical method parameters. The following table categorizes common modifications by risk level and recommended validation approach:

Table 3: Risk-Based Partial Validation Scoping for Method Modifications

| Modification Type | Risk Level | Recommended Validation Activities | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change in mobile phase organic modifier (e.g., acetonitrile to methanol) [1] | High | Nearly full validation excluding long-term stability [1] | Major change to separation mechanism with potential impact on multiple method parameters |

| Complete change in sample preparation paradigm (e.g., protein precipitation to liquid/liquid extraction) [1] | High | Nearly full validation excluding long-term stability [1] | Fundamental change to extraction efficiency with potential impact on accuracy and precision |

| Minor change in elution or reconstitution volume [1] | Low | Limited precision and accuracy determination [1] | Minimal impact on method performance with primarily dilution factor effects |

| Change to internal standard [1] | Medium | Selectivity, accuracy, precision, and recovery testing [1] | Potential impact on quantification accuracy requiring verification of method reliability |

| Adjustment of mobile phase proportions to modify retention times [1] | Low | Critical performance evaluation by analyst [1] | Minor adjustment unlikely to affect method validity but requires verification |

| Change in analytical range [1] | Medium | Linearity, accuracy, and precision at new range limits [1] | Requires demonstration of method performance at extended concentrations |

Experimental Protocol for Partial Validation

When conducting partial validation for modified analytical methods, the following experimental protocol provides a structured approach:

Risk Assessment Phase

- Document the specific method modification and its intended purpose

- Conduct FMEA evaluating potential failure modes introduced by the change

- Calculate Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) for each potential failure mode using established scales for severity, occurrence, and detection [21]

- Determine appropriate validation activities based on RPN scores and modification type

Experimental Design Phase

- Select validation parameters for evaluation based on risk assessment results

- For chromatographic assays: Include minimum of two sets of accuracy and precision data using freshly prepared calibration standards over a 2-day period [1]

- For ligand binding assays: Include minimum of four sets of inter-assay accuracy and precision runs on four different days with QCs at LLOQ and ULOQ [1]

- Establish acceptance criteria based on original method validation data and regulatory guidelines

Execution and Evaluation Phase

- Execute predefined validation experiments

- Compare results against acceptance criteria

- Document any deviations and investigate outliers

- Prepare final validation report with rationale for partial validation scope

Case Study: FMEA in Process Validation

A case study applying FMEA to a mammalian cell culture and purification process demonstrates the practical application of risk-based validation [21]. The study established a systematic approach to evaluate the impact of potential failures and their likelihood of occurrence for each unit operation.

FMEA Scale Development

The case study used conventional 10-point scales with four distinct levels for severity, occurrence, and detection [21]:

- Severity Scale: Measured consequences related to product quality, with the highest rating (10) assigned to potential lot rejection and the lowest (1) having no quality impact [21]

- Occurrence Scale: Based on the percentage of time the failure mode was expected to occur, from high likelihood (10) to low possibility (1) [21]

- Detection Scale: Used reverse logic, with high values (10) for failures impossible to detect before the next process step and low values (1) for failures almost certain to detect [21]

Implementation and Outcomes

The risk assessment covered the entire process, with unit operations included in process validation requiring a Risk Priority Number greater than or equal to a specified threshold value [21]. Unit operations scoring below the threshold were evaluated for secondary criteria such as regulatory expectations or historical commitments [21].

This approach ensured that validation resources were focused on unit operations with the highest potential impact on product quality, while providing documented rationale for excluding lower-risk operations from intensive validation activities [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of risk-based validation requires specific materials and documentation approaches. The following table outlines essential components of the validation toolkit:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Risk-Based Validation

| Toolkit Component | Function | Application in Risk-Based Validation |

|---|---|---|

| FMEA Worksheet Template [21] | Structured documentation of failure modes, effects, and control measures | Provides consistent approach to risk assessment across different validation projects |

| Risk Priority Number (RPN) Calculator [21] | Quantitative assessment of risk levels | Enables objective comparison and prioritization of risks for validation scoping |

| Reference Standards [2] | Establish accuracy and precision of analytical methods | Critical for partial validation to demonstrate maintained method performance after modifications |

| Quality Control Samples (LLOQ, ULOQ) [1] | Verify method performance at critical concentrations | Essential for demonstrating method reliability after changes, particularly for bioanalytical methods |

| Risk Threshold Matrix | Decision tool for validation inclusion/exclusion | Provides consistent criteria for determining which elements require validation based on risk scores |

| Traceability Matrix [23] | Links requirements, risks, and validation activities | Documents the rationale for validation scope decisions and provides audit trail |

The risk-based framework for scoping validation activities represents a scientifically rigorous approach that aligns with modern regulatory expectations. By focusing resources on elements with the greatest potential impact on product quality and patient safety, organizations can achieve both compliance and efficiency objectives. For partial validation of modified analytical methods, this framework provides a logical structure for determining the appropriate scope of revalidation activities based on the risk introduced by specific changes.

Implementation requires initial investment in risk assessment capabilities and documentation systems, but delivers significant returns through optimized resource utilization, reduced validation timelines, and more robust scientific justification for validation approaches. As regulatory guidance continues to emphasize risk-based principles, adopting this framework positions organizations for successful technology transfers, method modifications, and regulatory submissions.

Executing Partial Validation: A Step-by-Step, Risk-Based Methodology

In the landscape of analytical methods research, particularly for bioanalytical methods supporting pharmacokinetic and bioequivalence studies, the development of a robust protocol and precise acceptance criteria forms the critical foundation for effective partial validation. Partial validation is the demonstration of assay reliability following a modification of an existing bioanalytical method that has previously been fully validated [1]. This process is inherently risk-based, where the nature and significance of the methodological modification directly determine the extent of validation required [1]. Within this framework, a well-defined protocol establishes the experimental roadmap, while clearly articulated acceptance criteria provide the unambiguous benchmarks for determining success or failure at each validation stage. For researchers and drug development professionals, this approach creates a structured pathway for managing method changes—from adjustments in mobile phase composition to paradigm shifts in sample preparation—while maintaining data integrity and regulatory compliance throughout the method's lifecycle.

Defining Acceptance Criteria: Purposes and Formats

The Fundamental Role of Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria (AC) are predefined, pass/fail conditions that a software product, user story, or—in the context of analytical science—a methodological output must meet to be accepted by a user, customer, or other stakeholder [24] [25] [26]. They are unique for each user story or, by extension, each validation parameter, and define the feature behavior from the end-user’s perspective or the method performance from the scientist's perspective [24]. Well-written acceptance criteria prevent unexpected results at the end of a development stage by ensuring all stakeholders are satisfied with the deliverables [24]. In analytical research, they transform subjective judgments of "success" into objective, verifiable outcomes.

Effective acceptance criteria share several key traits: they must be clear and understandable to all team members, concise to avoid ambiguity, testable with straightforward pass/fail results, and focused on the outcome rather than the process of achieving it [24] [25]. They describe what the system or method must do, not how to implement it [24]. Perhaps most importantly, they must be defined before development or validation work begins to prevent misinterpretation and ensure the deliverable meets needs and expectations [24] [25].

Acceptance Criteria Formats: Rule-Oriented and Scenario-Based

Two predominant formats exist for articulating acceptance criteria, each with distinct advantages for analytical method validation:

Rule-Oriented Format (Checklist): This approach utilizes a simple bullet list of conditions that must be satisfied [24] [26]. It is particularly effective when specific test scenarios are challenging to define or when the audience does not require detailed scenario explanations [24]. For analytical methods, this might include criteria such as "The method's accuracy must be within ±15% of the nominal value for all quality control levels" or "The calibration curve must demonstrate a coefficient of determination (R²) of ≥0.99."

Scenario-Oriented Format (Given/When/Then): This format, inherited from behavior-driven development (BDD), employs a structured template to describe system behavior [24] [26]. It follows the sequence: "Given [some precondition], When [I do some action], Then [I expect some result]" [24]. This format reduces ambiguity by explicitly defining initial states, actions, and expected outcomes, making it valuable for validating specific analytical procedures.

Table 1: Comparison of Acceptance Criteria Formats for Analytical Method Validation

| Format | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Example in Analytical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-Oriented (Checklist) | Overall method performance parameters; Specific system suitability criteria [24] | Quick to create and review; Easy to convert into a verification checklist | - Precision (\%RSD) ≤15% at LLOQ- Signal-to-noise ratio ≥5:1 at LLOQ |

| Scenario-Oriented (Given/When/Then) | Specific sample preparation steps; Data interpretation rules; System operation sequences [24] [26] | Reduces ambiguity; Excellent for training; Clear pass/fail scenarios | Given a extracted sample, When it is injected into the LC-MS system, Then the analyte peak must be detected within ±0.5 minutes of the retention time for the standard. |

Acceptance Criteria vs. Definition of Done

A critical distinction exists between Acceptance Criteria (AC) and the Definition of Done (DoD). The Definition of Done is a universal checklist that every user story or validation activity must meet for the team to consider it complete, ensuring consistent quality across the project [24] [25]. For example, a DoD might include: "Code is completed," "Tested," "No defects," and "Live on production" in software, or "Data peer-reviewed," "Documentation completed," and "No unresolved anomalies" in research [25].

In contrast, Acceptance Criteria are specific to each user story or validation parameter and vary from one to another, tailored to meet the unique requirements of each [24]. The DoD applies to all items, while AC define what makes a specific item fit for purpose. In practice, a validation activity is "done" when it meets the DoD, but it is "accepted" only when it also satisfies all its specific AC [25].

Protocol Development and Acceptance Criteria in Practice

Developing the Protocol: A Strategic Framework

Protocol development, especially in clinical and bioanalytical contexts, requires a strategic focus on reducing unnecessary complexity to minimize operational burden. A key principle is starting with endpoints that matter. Incorporating non-essential endpoints that do not directly influence subsequent stages of development creates significant logistical and execution effort for irrelevant data [27]. One analysis estimated that 30% of all data gathered in clinical trials falls into this category [27]. Selecting the right, scientifically sound endpoints that are representative of real-world priorities prevents unnecessary medical costs, maintains higher data quality, and can reduce follow-up periods [27].

Furthermore, a patient-centric and site-friendly approach to protocol design directly improves recruitment, retention, and overall data quality. Reducing the number of procedures per visit and the associated time commitment reduces patient burden, which is strongly correlated with better retention rates, shorter trial durations, and fewer protocol amendments [27]. Similarly, freeing site investigators from excessive operational burden allows them to focus more effort on patient communication and recruitment. Proactively gathering patient feedback through surveys, focus groups, and burden analyses during the protocol design phase—rather than reacting to issues post-implementation—leads to more feasible, accessible, and successful studies [27].

Defining Acceptance Criteria for Method Validation

The specific acceptance criteria for a bioanalytical method validation or partial validation are dictated by the nature of the change and its potential impact on method performance. The following table summarizes common acceptance criteria for key analytical performance parameters, reflecting industry standards and regulatory expectations.

Table 2: Example Acceptance Criteria for Bioanalytical Method Validation Parameters

| Performance Parameter | Experimental Protocol Summary | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy and Precision | Analyze replicates (n≥5) of Quality Control (QC) samples at a minimum of three concentration levels (Low, Medium, High) across multiple runs [1]. | Accuracy: Mean value within ±15% of nominal value (±20% at LLOQ) [1].Precision: %RSD ≤15% (≤20% at LLOQ) [1]. |

| Selectivity/Specificity | Analyze replicates of blank matrix from at least six different sources to check for interference at the retention time of the analyte and internal standard [1]. | No interference ≥20% of analyte response at LLOQ and ≥5% of internal standard response [1]. |

| Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Analyze replicates (n≥5) of samples at the LLOQ concentration [1]. | Signal-to-noise ratio ≥5:1 [1].Accuracy and Precision within ±20% [1]. |

| Carryover | Inject a blank sample immediately after a high-concentration (upper limit of quantification) sample. | Peak response in blank ≤20% of LLOQ analyte response and ≤5% of internal standard response. |

The Partial Validation Lifecycle and Method Transfer