Reaction Condition Optimization: From Traditional Methods to AI-Driven High-Throughput Experimentation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern chemical reaction condition optimization techniques, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Reaction Condition Optimization: From Traditional Methods to AI-Driven High-Throughput Experimentation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern chemical reaction condition optimization techniques, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of optimization, including key parameters and common challenges. The piece delves into advanced methodological applications, highlighting machine learning, Bayesian optimization, and high-throughput experimentation (HTE) platforms. It also addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for data and algorithmic limitations and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques and algorithm performance. By synthesizing insights from recent literature and case studies, this review serves as a guide for implementing efficient, data-driven optimization strategies in both academic and industrial settings, with significant implications for accelerating pharmaceutical and fine chemical development.

The Fundamentals of Reaction Optimization: Core Concepts and Modern Challenges

Defining Reaction Optimization and Its Impact on Yield, Efficiency, and Cost

Frequently Asked Questions

What is reaction optimization and why is it critical in pharmaceutical development? Reaction optimization is the systematic process of tuning reaction parameters to simultaneously improve key outcomes such as yield, selectivity, and efficiency. In pharmaceutical process development, this is essential not only for maximizing the output of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) but also for incorporating economic, environmental, health, and safety considerations. Optimal conditions are often substrate-specific and challenging to identify. Traditional trial-and-error methods are slow and resource-intensive, which can delay drug development timelines. Machine learning (ML) frameworks like Minerva have demonstrated the ability to identify process conditions achieving >95% yield and selectivity in weeks, potentially replacing development campaigns that previously took months [1].

My reaction yield is low despite trying common conditions. How can I efficiently explore a large space of possibilities? High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) combined with Machine Learning is designed for this challenge. HTE platforms use miniaturized reaction scales and robotics to execute numerous reactions in parallel, making the exploration of thousands of condition combinations more cost- and time-efficient than traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches [1]. When even HTE cannot exhaustively screen a vast space, Bayesian Optimization guides the search. It uses machine learning to balance the exploration of unknown conditions with the exploitation of promising ones, identifying high-performing reactions in a minimal number of experimental cycles [1] [2]. For example, one study exploring over 12,000 combinations achieved joint yield and conversion rates over 80% for all four substrates in just 23 experiments [3].

How do I optimize for multiple objectives like both yield and selectivity? This is a common challenge, as these objectives can often compete. Modern multi-objective Bayesian optimization approaches are specifically designed for this task. They use acquisition functions like q-NParEgo or q-NEHVI to navigate the trade-offs between multiple goals [1]. The optimization outcome is not a single "best" condition, but a set of Pareto-optimal conditions that represent the best possible compromises between your objectives. You can then select the condition from this set that best aligns with your overall process priorities [1].

My optimized conditions from small-scale screens fail when scaled up. What am I missing? This is a classic scale-up problem. Conditions optimized at a small scale may not account for changes in heat transfer, mixing efficiency, and mass transfer limitations in larger reactors [4]. To improve scalability, ensure your optimization campaign includes robustness testing, where slight variations in critical parameters (like temperature or concentration) are tested to ensure the reaction outcome is stable [4]. Furthermore, specialized Bayesian optimization methods exist that are designed for multi-reactor systems with hierarchical constraints (like a common feed for reactor blocks), which can better bridge the gap between small-scale screening and larger-scale production [2].

I have a limited budget for experimentation. Can I still use data-driven optimization? Yes, methods have been developed specifically for scenarios with limited data. For instance, the "RS-Coreset" technique uses active learning to strategically select a small, representative subset of reactions (e.g., 2.5% to 5% of the full space) to evaluate. The yield information from this small set is then used to predict outcomes across the entire reaction space, significantly reducing the experimental load while still discovering high-yielding conditions that might otherwise be overlooked [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Yield and Poor Reproducibility

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Uncontrolled reaction parameters.

- Solution: Implement systematic approaches like Design of Experiments (DoE) instead of One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT). DoE can reveal critical interactions between variables (e.g., between temperature and concentration) that OFAT misses, leading to more robust and reproducible conditions [6].

- Cause 2: Inadequate reaction monitoring.

- Solution: Use robust, quantitative analytical techniques to track reaction progress accurately. Techniques like HPLC and GC provide precise data on starting material consumption and product formation. For complex mixtures, leverage modern software tools that allow for tailored peak-picking and quantification for each component, ensuring highly reliable data [7] [4].

- Cause 3: Sensitivity to slight parameter variations.

- Solution: Perform robustness testing (a key part of DoE) around your optimal conditions. Test a small range of values for critical parameters (e.g., temperature ±5°C, reagent equivalents ±0.1) to establish a "sweet spot" where the reaction outcome remains consistently high [4].

Problem: Optimization is Taking Too Long

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Using a sequential, manual optimization approach.

- Solution: Adopt highly parallel methods. HTE allows for the simultaneous testing of dozens or hundreds of conditions in a single batch. Integrating HTE with a batch Bayesian optimization algorithm (e.g., handling 96 experiments at a time) can dramatically accelerate the search for optima in large, complex spaces [1].

- Cause 2: The algorithm is not learning efficiently from past experiments.

- Solution: Utilize scalable machine learning frameworks. For multi-objective optimization, ensure your Bayesian optimization platform uses acquisition functions (like TS-HVI or q-NParEgo) that are computationally efficient for large batch sizes, enabling faster iteration cycles and convergence [1].

Problem: The Optimization Algorithm is Stuck in a Local Optimum

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Over-reliance on exploitation (refining known good conditions) and insufficient exploration of new regions.

- Solution: Adjust the balance in the acquisition function. Bayesian optimization naturally balances exploration and exploitation. However, if results stagnate, you can manually increase the weight on exploration. Alternatively, algorithms like Thompson Sampling are known for their strong exploration properties and can be effective in complex, multi-reactor systems to escape local optima [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: A 96-Well HTE Bayesian Optimization Campaign

The following protocol is adapted from a validated study on a nickel-catalysed Suzuki reaction [1].

1. Define the Reaction Condition Space:

- Compile a discrete set of all plausible reaction conditions, including reagents, solvents, catalysts, ligands, additives, and temperatures.

- Apply chemical knowledge and practical constraints to automatically filter out unsafe or impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points).

- In the cited study, this process defined a search space of 88,000 possible conditions [1].

2. Initial Experimental Batch Selection:

- Use a quasi-random Sobol sampling algorithm to select the first batch of 96 experiments.

- Purpose: This initial sampling maximizes the coverage of the reaction space, increasing the likelihood of discovering informative regions that may contain optima [1].

3. Automated Execution and Analysis:

- Execute the batch of 96 reactions in parallel using an automated HTE robotic platform.

- Analyze reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) using reliable quantitative methods like UPLC/PDA or LC/MS.

- Software tools like Chrom Reaction Optimization 2.0 can be used here for fine-grained control over target detection and quantification, including handling isomers and configuring peak-picking per trace [7].

4. Machine Learning Model Training and Next-Batch Selection:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all accumulated experimental data to predict reaction outcomes and their associated uncertainties for all conditions in the search space.

- Use a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to evaluate all conditions and select the next most promising batch of 96 experiments. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performing areas [1].

5. Iteration and Convergence:

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 for as many iterations as needed.

- Terminate the campaign upon convergence (i.e., no significant improvement in objectives), stagnation, or exhaustion of the experimental budget.

Quantitative Data from Recent Studies

Table 1: Impact of Advanced Optimization Techniques on Key Metrics

| Optimization Technique | Reaction Type | Key Improvement | Experimental Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML Framework (Minerva) [1] | Ni-catalysed Suzuki coupling; Pd-catalysed Buchwald-Hartwig | Identified conditions with >95% area percent yield and selectivity | Accelerated process development: achieved in 4 weeks vs. previous 6-month campaign |

| AI & Automation (SDLabs & RoboRXN) [3] | Iodination of terminal alkynes | Achieved joint yield and conversion rates >80% for all substrates | 23 experiments covered ~0.2% of 12,000+ possible combinations |

| Coreset-Based Active Learning (RS-Coreset) [5] | Buchwald-Hartwig coupling | >60% of predictions had absolute errors <10% | Required yields for only 5% of the 3,955 reaction combinations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for Cross-Coupling Reaction Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts | Lower-cost, earth-abundant alternatives to precious metals like palladium; important for sustainable and economical process design. | Nickel catalysts were successfully optimized for Suzuki couplings, replacing traditional Pd catalysts [1]. |

| Ligand Libraries | Fine-tune catalyst activity and selectivity; a critical categorical variable that dramatically influences the reaction yield landscape. | Bayesian optimization efficiently navigates different ligands to find those that enable high yield and selectivity [1] [5]. |

| Solvent Sets | Affect solubility, reaction rate, and mechanism. Solvent selection is often guided by pharmaceutical industry guidelines for safety and environmental impact. | ML algorithms screen various solvents to find those that meet both performance and regulatory criteria [1]. |

| Additives | Can act as activators, stabilizers, or scavengers to overcome reaction-specific challenges and improve outcomes. | Included as a key parameter in the combinatorial reaction condition space for the algorithm to explore [1] [5]. |

Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting Guides

Temperature

Issue: Reaction yield is low or reaction fails at the prescribed temperature.

- Potential Cause 1: The reaction temperature is below the activation energy barrier.

- Solution: Confirm the temperature range using the Arrhenius equation. Use a controlled heating source (e.g., oil bath) for consistent heating and verify the temperature with a calibrated thermometer.

- Potential Cause 2: Solvent boiling point is exceeded, leading to solvent loss or pressure buildup.

- Solution: Ensure the reaction temperature is at least 10-15°C below the solvent's boiling point. Use a reflux condenser to prevent solvent loss.

Issue: Unwanted side products or decomposition is observed.

- Potential Cause: The reaction temperature is too high, promoting side reactions.

- Solution: Lower the reaction temperature and consider a gradual addition of reagents to control exothermicity.

Catalysts

Issue: Low catalytic activity or reaction failure.

- Potential Cause 1: Catalyst decomposition or deactivation under reaction conditions.

- Solution: Check the stability of the catalyst. Inorganic supports or ligands can stabilize catalysts. For air-sensitive catalysts (e.g., Ni(0), Pd(0)), ensure an inert atmosphere is rigorously maintained [1].

- Potential Cause 2: The catalyst is not suitable for the specific reaction type or substrate.

- Solution: Employ a catalyst screening strategy. Modern approaches use machine learning frameworks like Minerva or CatDRX, which are pre-trained on broad reaction databases to recommend or generate effective catalyst candidates for given reaction conditions [1] [8].

Issue: Difficulty in separating the catalyst from the reaction mixture.

- Potential Cause: Use of a homogeneous catalyst.

- Solution: Switch to a heterogeneous catalyst, which can be removed by simple filtration, or use a biphasic system (e.g., water/organic) where the catalyst resides in one phase and the product in the other.

Solvents

Issue: Poor reaction yield due to substrate solubility.

- Potential Cause: The solvent polarity is incompatible with the reactants.

- Solution: Consult a solvent selectivity table. Switch to a solvent with a more appropriate polarity index or use solvent mixtures. For green chemistry, consider bio-based solvents like Cyrene or 2-MeTHF [9].

Issue: The solvent is classified as hazardous.

- Potential Cause: Use of a volatile organic compound (VOC) or toxic solvent.

- Solution: Replace with a safer, greener alternative. Refer to the ACS GCI Pharmaceutical Roundtable solvent selection guide. Common green substitutes include water, ethanol, supercritical CO₂, and ionic liquids [9] [10].

Concentration

Issue: The reaction is too slow.

- Potential Cause: Low concentration of reactants leads to infrequent molecular collisions.

- Solution: Increase the concentration of reactants, if solubility permits, to enhance the reaction rate.

Issue: Viscosity buildup or precipitation occurs, hindering mixing.

- Potential Cause: Concentration is too high.

- Solution: Dilute the reaction mixture with additional solvent to improve mass transfer and mixing efficiency.

Reaction Time

Issue: Incomplete conversion even after extended time.

- Potential Cause: The reaction has reached equilibrium, or the catalyst is deactivated.

- Solution: Monitor the reaction progress analytically (e.g., by LC-MS, TLC). Remove a byproduct (e.g., water) to shift equilibrium or add a fresh portion of catalyst.

Issue: Product degradation over time.

- Potential Cause: The product is unstable under prolonged reaction conditions.

- Solution: Shorten the reaction time by using a more active catalyst or higher temperature. Use in-process monitoring to determine the optimal quenching time [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most efficient method to simultaneously optimize multiple reaction parameters like temperature, catalyst loading, and solvent? Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches are inefficient for multi-parameter optimization. A more effective strategy is to use Machine Learning (ML)-driven Bayesian optimization integrated with high-throughput experimentation (HTE). Frameworks like Minerva can explore high-dimensional search spaces (e.g., 88,000 conditions) efficiently. They use an acquisition function to balance the exploration of new conditions and the exploitation of known promising areas, rapidly identifying optimal conditions that satisfy multiple objectives (e.g., high yield and selectivity) [1] [6].

Q2: How can I design a novel catalyst for a specific reaction? Generative AI models, such as the CatDRX framework, are now used for inverse catalyst design. These models are pre-trained on vast reaction databases and can be fine-tuned for your specific reaction. Given the reaction conditions (reactants, reagents, desired product), the model generates potential catalyst structures and predicts their performance, significantly accelerating the discovery process beyond conventional trial-and-error or existing libraries [8].

Q3: Are there any alternatives to using solvents and catalysts altogether? Yes. "Solvent-free and catalyst-free" reactions are an advanced area of green synthesis. These reactions often rely on alternative energy inputs like mechanochemistry (grinding) or microwave irradiation to drive the reaction forward. While not universally applicable, they represent the ultimate in waste reduction by eliminating auxiliary materials, aligning with the principles of green chemistry [11].

Q4: What is the best way to present quantitative data from my optimization campaign? Structured tables are essential for clear data comparison. Below is an example summarizing key performance metrics from a machine learning-driven optimization campaign for a pharmaceutical synthesis [1].

Table 1: Optimization Outcomes for API Syntheses using ML-Guided HTE

| Reaction Type | Catalyst | Key Optimized Parameters | Performance (Area Percent) | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suzuki Coupling | Nickel | Ligand, Solvent, Temperature | >95% Yield, >95% Selectivity | Identified improved process conditions in 4 weeks vs. 6 months. |

| Buchwald-Hartwig Amination | Palladium | Ligand, Solvent, Concentration | >95% Yield, >95% Selectivity | Accelerated process development timeline. |

Q5: How do I balance the trade-offs between different objectives, such as maximizing yield while minimizing cost? This is a classic multi-objective optimization problem. Machine learning algorithms are particularly suited for this. They use metrics like Hypervolume Improvement to navigate the trade-offs. You can assign weights to your objectives (e.g., yield is twice as important as cost), and the algorithm will identify a set of "Pareto-optimal" conditions where no objective can be improved without worsening another [1] [6].

Experimental Protocol: ML-Guided High-Throughput Optimization

This protocol outlines the methodology for optimizing a catalytic reaction using an automated machine learning framework, as validated in recent studies [1].

1. Define the Reaction Condition Space:

- Compile discrete combinatorial sets of plausible reaction parameters: catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, additives, temperature range, and concentration range.

- Apply chemical knowledge filters to exclude impractical or unsafe combinations (e.g., temperature exceeding solvent boiling point, incompatible reagents).

2. Initial Experimental Batch (Sobol Sampling):

- Use a Sobol sequence algorithm to select the first batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate).

- This quasi-random sampling ensures the initial conditions are widely spread across the entire defined search space for maximum coverage.

3. Automated Execution and Analysis:

- Execute the batch of reactions using an automated HTE robotic platform.

- Analyze reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity, conversion) via automated analytical techniques (e.g., UPLC-MS).

4. Machine Learning Iteration Cycle:

- Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all accumulated experimental data. The model learns to predict reaction outcomes and their associated uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space.

- Next-Batch Selection: An acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) uses the model's predictions to select the next most promising batch of experiments. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting conditions predicted to be high-performing.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until convergence (e.g., no significant improvement in hypervolume) or the experimental budget is exhausted.

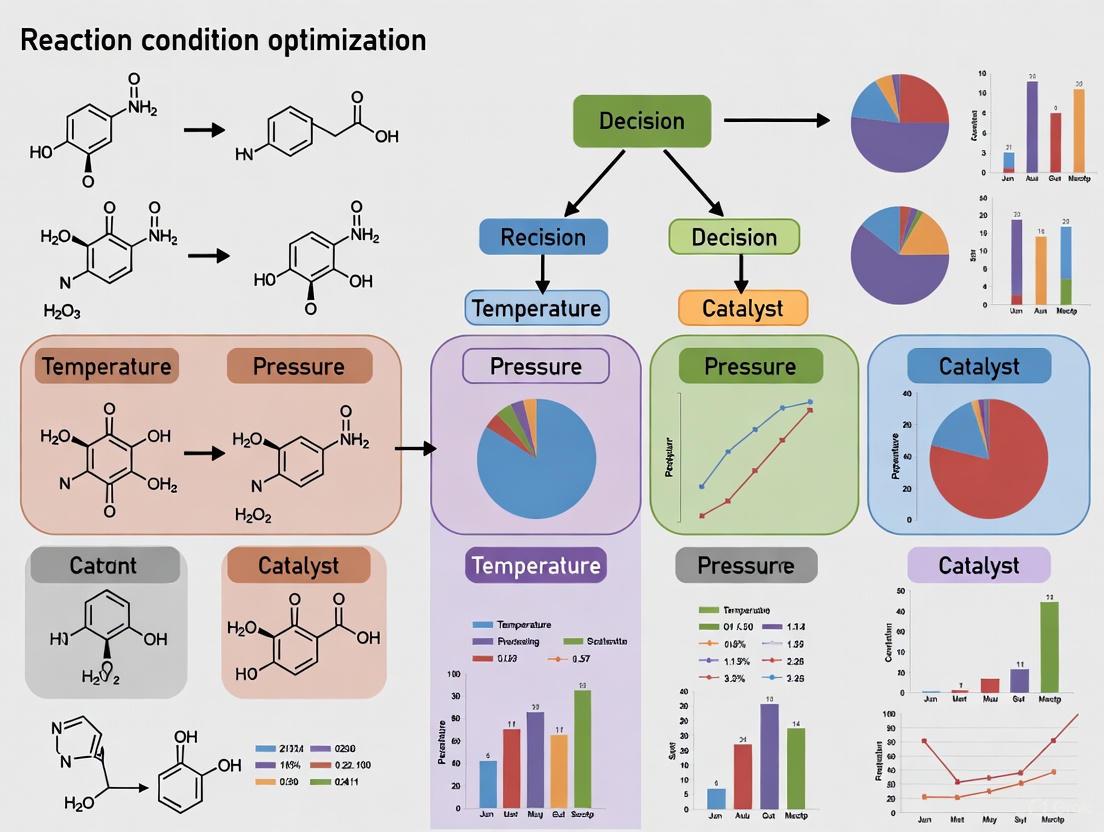

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Modern Reaction Optimization

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ni, Fe, Cu) | Earth-abundant, lower-cost alternatives to precious metals like Pd and Pt for cross-coupling and other catalytic reactions. Key for sustainable process design [1] [9]. |

| Structured Ligand Libraries | Collections of diverse phosphine, nitrogen-based, and other ligands. Used in HTE screens to rapidly identify the optimal ligand for a metal-catalyzed transformation, which can dramatically impact yield and selectivity [1]. |

| Green Solvent Kits | Pre-selected collections of solvents aligning with green chemistry principles, including bio-based solvents (e.g., 2-MeTHF, Cyrene), water, and ionic liquids. Essential for developing environmentally benign processes [9] [10]. |

| ML-Optimization Software (e.g., Minerva) | A machine learning framework that automates experimental design and decision-making for highly parallel reaction optimization. It efficiently navigates large, multi-dimensional search spaces to find optimal conditions [1]. |

| Generative AI Models (e.g., CatDRX) | A deep learning framework for catalyst discovery. It uses a reaction-conditioned variational autoencoder to generate novel catalyst structures and predict their performance for given reactions [8]. |

The Pitfalls of Traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Approaches

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why doesn't my experiment find the optimal reaction conditions, even after extensive testing?

This is a common issue with the OFAT approach, primarily caused by its failure to detect interaction effects between factors.

- Problem Detail: In OFAT, you vary one factor while holding all others constant. This assumes that factors act independently. However, in complex chemical systems, factors like temperature and catalyst concentration often interact; the best level for one depends on the level of the other. OFAT is blind to these interactions [12] [13].

- Evidence: Simulation studies demonstrate that OFAT finds the true optimal process settings only about 20-30% of the time, meaning it can fail up to 80% of the time, regardless of the number of runs performed [12].

- Solution: Adopt a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach. DOE uses structured tests where multiple factors are varied simultaneously. This allows you to mathematically model the response surface and identify not just main effects, but also crucial interaction effects between variables, leading you to the true optimum [13].

Yes, OFAT is notoriously inefficient, and this is a well-documented pitfall.

- Problem Detail: OFAT requires a large number of experimental runs. For example, a process with just 5 factors can require 46 runs using a typical OFAT method. The required number of runs increases linearly with each additional factor, making it unsustainable for complex systems [12] [14].

- Solution: DOE is designed for efficiency. For the same 5-factor process, a screening design from JMP's Custom Designer required only 12-27 runs to model main and interaction effects [12]. Furthermore, advanced machine learning (ML) frameworks like Minerva have been shown to identify optimal conditions for challenging reactions like Ni-catalyzed Suzuki couplings in a fraction of the time compared to traditional methods, sometimes accelerating process development from 6 months to just 4 weeks [1].

How can I account for multiple, competing objectives like yield, selectivity, and cost during optimization?

OFAT is fundamentally unsuited for multi-objective optimization, as it provides no model to understand trade-offs.

- Problem Detail: Optimizing for one response at a time (e.g., maximizing yield) can inadvertently push other critical responses (e.g., selectivity or cost) into an unacceptable range. OFAT offers no systematic way to balance these competing goals [13].

- Solution: Modern optimization strategies combine DOE or ML-guided High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) with multi-objective optimization algorithms. For instance, Bayesian Optimization can use acquisition functions like q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-EHVI) to navigate complex landscapes and find a set of Pareto-optimal conditions that represent the best compromises between multiple objectives, such as yield and selectivity [1] [15].

My optimized process is not robust when scaled up. What am I missing?

OFAT provides a narrow view of the experimental space, so the "optimum" it finds is often a false peak that is highly sensitive to small variations.

- Problem Detail: Because OFAT explores a very limited path through the possible factor combinations, it does not characterize the broader experimental space. A condition that seems optimal in a narrow OFAT study might be on a steep slope, meaning small, unavoidable changes during scale-up can lead to significant performance loss [12].

- Solution: Response Surface Methodology (RSM), a key tool within DOE, creates a predictive model of your entire region of interest. This model allows you to locate a "robust optimum"—a set of conditions that not only provides a high yield but is also less sensitive to process variations. You can use the model's profiler to find factor settings that meet a target (e.g., a specific yield) while minimizing the impact of expensive ingredients [12] [13].

Quantitative Comparison: OFAT vs. Modern Approaches

The table below summarizes the key performance differences between OFAT and more advanced methodologies.

| Feature | One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Design of Experiments (DOE) | ML-Guided High-Throughput Experimentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Efficiency | Low. Example: 46 runs for 5 factors [12]. | High. Example: 12-27 runs for 5 factors [12]. | Very High. Identifies optimum in a minimal number of iterative batches (e.g., 96-well plates) [1]. |

| Ability to Detect Interactions | No. Cannot detect interactions between factors, a major cause of missed optima [12] [13] [14]. | Yes. Specifically designed to estimate and quantify two-factor and higher-order interactions [13]. | Yes. ML models (e.g., Gaussian Processes) naturally capture complex, non-linear interactions [1]. |

| Success Rate in Finding True Optimum | Low. ~20-30% in simulation studies [12]. | High. Systematically explores the space to reliably find a global optimum [12]. | High. Uses intelligent search to efficiently navigate high-dimensional spaces and find global optima [16] [1]. |

| Output & Applicability | A single data point or series of unconnected results. Limited predictive power [12]. | A predictive mathematical model of the process. Allows for "what-if" analysis and in-silico optimization [12] [13]. | A predictive model and a set of verified optimal conditions. Capable of fully autonomous optimization campaigns [1] [15]. |

| Best Use Case | Very preliminary, intuitive investigation when data is cheap and abundant [17]. | Systematic process development, optimization, and robustness testing for R&D and manufacturing [13]. | Highly complex systems with many variables and multiple objectives, especially with tight timelines [1] [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Modern ML-Guided Optimization Campaign

The following workflow, as demonstrated in recent literature, outlines the steps for a machine-learning-guided reaction optimization campaign using high-throughput experimentation [1] [15].

Objective: To autonomously optimize a chemical reaction (e.g., a Ni-catalyzed Suzuki coupling) for multiple objectives, such as yield and selectivity.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Define the Reaction Condition Space:

- Compile a discrete set of all plausible reaction conditions. This includes categorical variables (e.g., solvent, ligand, base) and continuous variables (e.g., temperature, concentration, catalyst loading).

- Critical Step: Apply chemical knowledge and process constraints to filter out impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding a solvent's boiling point or unsafe reagent pairs) [1].

Initial Experimental Design (Sobol Sampling):

- Use an algorithm like Sobol sampling to select the initial batch of experiments (e.g., one 96-well plate).

- Purpose: This technique ensures the initial experiments are maximally diverse and spread out across the entire defined reaction space, providing broad coverage for the initial model [1].

Execute Experiments and Collect Data:

Train the Machine Learning Model:

- Input the experimental data (conditions and results) into a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor.

- The trained GP model will predict the reaction outcomes and, crucially, the associated uncertainty for every possible condition in your predefined space [1].

Select the Next Batch of Experiments via Acquisition Function:

- Use a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo or Thompson Sampling) to analyze the GP model's predictions.

- Purpose: The acquisition function automatically balances exploration (testing conditions with high uncertainty) and exploitation (testing conditions predicted to be high-performing) to select the most informative next batch of experiments [1].

Iterate to Convergence:

- Repeat steps 3-5 for several iterations. The algorithm will quickly focus the experimental effort on the most promising regions of the condition space.

- Termination: The campaign is stopped when performance converges, a satisfactory condition is identified, or the experimental budget is exhausted [1] [15].

Workflow Diagram: ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Technologies

The table below lists essential components for setting up a modern, automated reaction optimization laboratory.

| Item | Function in Optimization | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Batch Platform (e.g., Chemspeed, Unchained Labs) | Executes numerous reactions in parallel (e.g., in 96-well plates) for rapid data generation. | Integrates liquid handling, reactors, and agitation. Allows for precise control of categorical and continuous variables on a small scale [16]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | The core intelligence that guides the experimental strategy by balancing exploration and exploitation. | Uses a statistical model (like a Gaussian Process) to predict reaction outcomes and an acquisition function to decide the most valuable next experiments [1] [15]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | The machine learning model that predicts reaction outcomes and quantifies its own uncertainty. | This model is key to understanding the "landscape" of your reaction and is particularly good at handling limited data, which is typical in initial optimization campaigns [1]. |

| Multi-Objective Acquisition Function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) | Selects the next experiments when optimizing for more than one goal (e.g., Yield AND Selectivity). | These functions compute the potential value of testing a new condition by estimating how much it could improve the entire set of best-found solutions across all objectives [1]. |

| Chemical Descriptors | Converts categorical variables (like solvent or ligand identity) into a numerical format that the ML model can understand. | Enables the algorithm to reason about chemical similarity and its relationship to reaction performance, which is crucial for exploring categorical spaces [1]. |

Data Scarcity and the 'Completeness Trap' in Dataset Preparation

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 'Completeness Trap' and data scarcity? The "Completeness Trap" occurs when researchers delay machine learning projects indefinitely, seeking a perfect, 100% complete dataset before beginning any analysis [18]. Data scarcity is the challenge of having a limited amount of labeled training data or a severe imbalance between available labels [19]. In high-stakes fields like drug discovery, these issues can paralyze research and development.

How can I start modeling with scarce or incomplete data? Begin with simple heuristics and domain knowledge to create an initial, interpretable model. This approach provides a baseline functionality without requiring large datasets and allows the product or research to move forward [19]. As more data becomes available, you can transition to more complex models.

What techniques can generate data for rare events? For rare events, such as machine failures in predictive maintenance, you can create "failure horizons." This technique labels the last 'n' observations before a failure event as 'failure,' artificially increasing the number of positive examples in your training set [20]. For other data types, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can create synthetic data with patterns similar to your observed data [20].

How does data quality impact AI in drug development? High-quality data is a non-negotiable prerequisite for effective AI models. Poor data quality introduces noise and bias, which can distort critical metrics like the Probability of Technical and Regulatory Success (PTRS). This leads to misinformed decisions, unreliable comparisons, and a loss of credibility in financial models [18].

What are the core attributes of high-quality data? High-quality data is characterized by six core attributes [18]:

- Completeness: Captures the full picture with all relevant variables.

- Granularity: Provides a detailed, multi-dimensional view.

- Traceability: Every data point can be traced back to its source.

- Timeliness: Data is current and updated continuously.

- Consistency: Uses uniform terminology and standard data formats.

- Contextual Richness: Linked to its clinical and regulatory background.

Can I use pre-trained models to overcome data scarcity? Yes, transfer learning is a powerful technique for this. It involves taking a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset (e.g., a broad reaction database) and fine-tuning it on your smaller, domain-specific dataset. This allows you to leverage general patterns learned from big data for your specific task [21] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model performs poorly due to insufficient training data. Solution: Implement a synthetic data generation pipeline.

- Step 1: Identify the type and structure of your scarce data (e.g., time-series sensor readings, molecular representations).

- Step 2: Select an appropriate generative model. For general-purpose data, consider Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [20]. For molecular and reaction data, a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) might be more suitable [21].

- Step 3: Train the generative model on your existing observed data. In a GAN, the generator creates synthetic data while the discriminator tries to distinguish it from real data; this adversarial competition continues until the generator produces realistic data [20].

- Step 4: Use the trained generator to create synthetic data that shares relational patterns with your original dataset [20].

- Step 5: Combine synthetic and real data to train your final predictive machine learning model.

Problem: Dataset is imbalanced with very few positive examples (e.g., machine failures, rare disease cases). Solution: Apply techniques to address class imbalance.

- Step 1: Define a "failure horizon" for your data. If your data is temporal (e.g., run-to-failure), label the last 'n' time-step observations before a failure event as 'failure' [20].

- Step 2: For non-temporal data, consider using algorithmic approaches like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to generate more examples of the rare class [19].

- Step 3: When training your model, use evaluation metrics that are robust to imbalance, such as F1-score, precision-recall curves, or Cohen's Kappa, instead of relying solely on accuracy [22].

Problem: Struggling to build a first model with no labeled dataset. Solution: Develop a heuristic model based on domain expertise.

- Step 1: Collaborate with domain experts (e.g., chemists, biologists) to identify key signals or features that influence the outcome. For example, in ranking news articles, signals could be relevance score, article recency, and publisher popularity [19].

- Step 2: Construct a simple, interpretable function to combine these signals. A linear model like

w1*f1 + w2*f2 + w3*f3is a common starting point, whereware weights andfare the feature signals [19]. - Step 3: Manually tune the weights based on qualitative analysis and domain intuition until the model's output is satisfactory.

- Step 4: Deploy the heuristic model. This provides immediate functionality and a baseline for future data-driven models.

Quantitative Data on Data Quality Methods

The table below summarizes a study comparing traditional and advanced approaches to data handling, showing the significant impact of methodology on key data quality metrics [22].

| Data Quality Dimension | Traditional Approach | Advanced Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (F1 Score) | 59.5% | 93.4% |

| Completeness | 46.1% | 96.6% |

| Traceability | 11.5% | 77.3% |

| Description | Used single-source structured data (EHR or claims) accessed with SQL. [22] | Incorporated multiple data sources (unstructured EHR, claims, mortality registry) and AI technologies. [22] |

Experimental Protocol: Overcoming Scarcity with GANs and Failure Horizons

This protocol details a methodology for building predictive maintenance models in scenarios with scarce and imbalanced data [20].

1. Objective: To train accurate machine learning models for predicting equipment failure by overcoming data scarcity and imbalance.

2. Materials and Data Sources:

- Dataset: Run-to-failure data from industrial equipment (e.g., the Production Plant Data for Condition Monitoring from Kaggle) [20].

- Software: Python programming environment with libraries such as TensorFlow or PyTorch for building GANs and other ML models.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing

- Clean the data by handling minor missing values (e.g., 0.01% missingness can often be imputed or removed).

- Normalize all sensor readings using min-max scaling to maintain a consistent scale [20].

- Create initial labels where only the final observation in each run is labeled as a 'failure'.

Step 2: Address Data Imbalance with Failure Horizons

- To rectify the extreme imbalance (e.g., 228,416 healthy vs. 8 failure observations), create a failure horizon.

- Re-label the data so that the last 'n' observations before each failure are also classified as 'failure'. This increases the number of failure instances for the model to learn from [20].

Step 3: Address Data Scarcity with Synthetic Data

- Train a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) on the preprocessed and re-labeled run-to-failure data.

- The GAN's generator will learn to produce synthetic time-series data that mimics the patterns of the real equipment data.

- Use the trained generator to create a large synthetic dataset [20].

Step 4: Model Training and Evaluation

- Train various machine learning models (e.g., ANN, Random Forest, XGBoost) on the augmented dataset containing both real and synthetic data.

- Evaluate model performance using accuracy and other relevant metrics. The cited study achieved an accuracy of 88.98% with an ANN using this approach [20].

Workflow: Overcoming Data Scarcity and Imbalance

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for tackling data challenges, from preprocessing to model training.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and techniques essential for experiments dealing with data scarcity in reaction optimization and predictive maintenance.

| Reagent / Technique | Function |

|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | A neural network architecture that generates synthetic data with patterns similar to the original, scarce dataset. It is used to create a larger, augmented training set. [20] |

| Failure Horizon | A labeling technique that marks the last 'n' observations before a failure as positive. It directly mitigates data imbalance in run-to-failure datasets. [20] |

| Transfer Learning / Pre-trained Model | A method where a model pre-trained on a large, broad dataset is fine-tuned on a smaller, specific dataset. This leverages general knowledge for a specialized task. [21] [19] |

| Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) | A generative model that learns to produce data samples (e.g., catalyst molecules) conditioned on specific inputs (e.g., reaction components). It is useful for inverse design. [21] |

| Heuristic Model | A rule-based model created from domain expertise, used as a starting point when labeled data is insufficient for training a statistical model. [19] |

Molecular Representation as a Primary Bottleneck in Advancing Optimization

→ Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

This guide helps diagnose and resolve common issues related to molecular representation in optimization workflows.

Problem: Poor Model Performance in Catalyst Optimization

- Symptoms: Low prediction accuracy for yield or catalytic activity; inability to identify high-performing catalysts.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Representation of Reaction Context. The model only uses catalyst structure, ignoring critical reaction components.

- Solution: Implement a reaction-conditioned model. Use a framework like CatDRX, which jointly learns from catalysts and other reaction components (reactants, reagents, products) to create a comprehensive catalytic reaction embedding [8].

- Cause 2: Representation Mismatch Between Pre-training and Target Domain.

- Solution: Perform a chemical space analysis. Generate t-SNE embeddings of reaction fingerprints (RXNFPs) and catalyst fingerprints (ECFP4) from both your target dataset and the model's pre-training data. If overlap is minimal, consider domain adaptation techniques or seek a more broadly pre-trained model [8].

- Cause 1: Inadequate Representation of Reaction Context. The model only uses catalyst structure, ignoring critical reaction components.

Problem: Inefficient Search in High-Dimensional Representation Spaces

- Symptoms: Bayesian optimization (BO) fails to converge or requires an excessive number of experiments to find optimal materials.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Curse of Dimensionality from Overly Complex Representations.

- Solution: Integrate dynamic feature selection into the BO loop. Use the Feature Adaptive Bayesian Optimization (FABO) framework. At each cycle, employ feature selection methods like Maximum Relevancy Minimum Redundancy (mRMR) to identify and use only the most informative features for the specific task [23].

- Cause 2: Suboptimal Fixed Representation.

- Solution: For MOF optimization, start with a complete feature set that includes both chemical (e.g., Revised Autocorrelation Calculations - RACs) and geometric pore characteristics. Allow the FABO framework to adaptively select the relevant features during optimization [23].

- Cause 1: Curse of Dimensionality from Overly Complex Representations.

Problem: Failure to Generalize in Scaffold Hopping

- Symptoms: Models successfully identify analogs with similar scaffolds but fail to find novel, functionally equivalent core structures.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Reliance on Traditional Structural Fingerprints.

- Solution: Transition to AI-driven continuous representations. Use graph neural networks (GNNs) or transformer-based models trained on large, diverse molecular datasets. These models learn high-dimensional embeddings that capture non-linear structure-activity relationships, enabling identification of non-obvious scaffold hops [24].

- Cause: Reliance on Traditional Structural Fingerprints.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our HTE campaign has a large search space (88,000+ conditions). Which ML strategy is best suited for this scale? A1: For highly parallel optimization in large search spaces, a scalable Bayesian optimization framework is recommended. The Minerva platform has been experimentally validated to handle batch sizes of 96 and high-dimensional spaces efficiently. It uses scalable acquisition functions like q-NParEgo and TS-HVI, which are designed for large parallel batches and multiple objectives, outperforming traditional chemist-designed approaches [1].

Q2: What is the practical impact of choosing the wrong molecular representation? A2: A suboptimal representation can severely hinder optimization. For example, a study on MOF discovery showed that when key features were missing from the representation, the performance of Bayesian optimization significantly degraded. An adaptive representation strategy led to the identification of top-performing materials 2-3 times faster than using a fixed, suboptimal representation [23].

Q3: How can I represent a chemical reaction as a whole, rather than just individual molecules? A3: Modern approaches move beyond representing single molecules. You can use reaction fingerprints (RXNFPs) [8] or employ a joint architecture that embeds multiple reaction components. For instance, frameworks like CatDRX create a unified "catalytic reaction embedding" by processing catalysts, reactants, reagents, and products simultaneously, which is then used for prediction or generation tasks [8].

Q4: Our project involves a novel reaction with little historical data. How can we approach representation? A4: In scenarios with sparse data, starting with a broad exploration of categorical variables (e.g., ligand, solvent) is crucial. Represent the reaction condition space as a discrete combinatorial set of plausible conditions. Initiate the optimization with algorithmic quasi-random sampling (e.g., Sobol sampling) to maximize initial coverage of the reaction space. This increases the likelihood of discovering promising regions before fine-tuning continuous parameters [1].

→ Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Highly Parallel ML-Driven Optimization Campaign

This protocol is based on the Minerva framework for automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [1].

- Define Search Space: Enumerate all plausible reaction parameters (catalysts, ligands, solvents, additives, temperatures, concentrations) as a discrete combinatorial set. Apply chemical knowledge filters to exclude impractical or unsafe combinations.

- Initial Batch Selection: Use Sobol sampling to select the first batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate). This ensures diverse coverage of the reaction condition space.

- Execute Experiments & Analyze: Run reactions using an automated HTE platform. Analyze outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) via high-throughput analytics (e.g., UPLC/HPLC).

- Train ML Model & Select Next Batch: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all acquired data. Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to evaluate all possible conditions and select the next most promising batch of experiments.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until convergence or budget exhaustion.

Protocol 2: Reaction-Conditioned Catalyst Generation and Screening with CatDRX

This protocol outlines the use of a generative model for catalyst design [8].

- Model Setup: Utilize a pre-trained Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) model. The model should have three core modules:

- A catalyst embedding module (processes catalyst structure).

- A condition embedding module (processes reactants, reagents, products, reaction time).

- An autoencoder module (encoder, decoder, and predictor).

- Fine-Tuning: If necessary, fine-tune the pre-trained model on a downstream dataset relevant to your reaction of interest.

- Candidate Generation: For a given set of reaction conditions, sample a latent vector and use the decoder to generate novel catalyst structures.

- Performance Prediction & Validation: Use the model's predictor to estimate the performance (e.g., yield) of generated catalysts. Filter candidates using background chemical knowledge and validate top candidates with computational chemistry (e.g., DFT) or targeted experiments.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions in Large-Batch Optimization (Hypervolume % after 5 iterations, batch size 96) [1]

| Acquisition Function | Benchmark Dataset A | Benchmark Dataset B | Benchmark Dataset C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sobol (Baseline) | 45.2% | 38.7% | 51.5% |

| q-NParEgo | 72.5% | 65.1% | 78.3% |

| TS-HVI | 70.8% | 63.9% | 76.5% |

| q-NEHVI | 68.3% | 60.5% | 74.1% |

Table 2: Predictive Performance of CatDRX on Various Catalytic Activity Datasets [8]

| Dataset | Target Property | Model | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BH | Reaction Yield | CatDRX | 1.92 | 1.41 |

| SM | Reaction Yield | CatDRX | 2.15 | 1.58 |

| UM | Reaction Yield | CatDRX | 2.01 | 1.49 |

| AH | Enantioselectivity (ΔΔG‡) | CatDRX | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| CC | Catalytic Activity | CatDRX | 0.91 | 0.72 |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Molecular Representation and Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Minerva ML Framework [1] | Scalable Bayesian Optimization | Highly parallel reaction optimization in HTE (e.g., 96-well plates). |

| CatDRX Model [8] | Reaction-conditioned generative model | Catalyst discovery and yield prediction for given reaction components. |

| FABO Framework [23] | Feature-adaptive Bayesian optimization | Dynamic material representation for MOF and molecule discovery. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [24] | Learning graph-based molecular embeddings | Capturing complex structure-property relationships for scaffold hopping. |

| Reaction Fingerprints (RXNFP) [8] | Representing entire chemical reactions | Analyzing and comparing the chemical space of reactions. |

| mRMR Feature Selection [23] | Selecting informative, non-redundant features | Dimensionality reduction within an adaptive BO framework. |

→ Workflow Visualization

ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

Reaction-Conditioned Catalyst Generation

Advanced Methodologies: Machine Learning, HTE, and Automated Workflows in Action

Troubleshooting Guides

Robotic Platform Performance Issues

Problem: The robotic arm fails to dispense solids or liquids accurately.

- Potential Cause 1: Clogged or worn dispensing tips.

- Solution: Implement a routine cleaning and calibration protocol. For positive displacement tips, flush with an appropriate solvent. Check tips for visible wear and replace them according to the manufacturer's schedule [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect calibration of liquid handler.

- Solution: Recalibrate the liquid dispensing volumes using a gravimetric method. Ensure the robotic arm's positional calibration is up to date, especially if the system uses vision feedback for well plate localization [25].

- Potential Cause 3: Software communication error.

- Solution: Reboot the control software and the physical hardware. Check all connection cables and ensure the latest firmware and driver versions are installed.

Problem: The system cannot detect the position of well plates or labware.

- Potential Cause 1: Fiducial markers (e.g., AprilTags) are obscured, moved, or have poor lighting.

- Solution: Ensure all fiducial markers are clean and firmly attached in their calibrated positions. Check that the overhead camera has a clear, unobstructed view and that the lighting conditions are consistent with the calibration setup [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Well plate is not seated in the expected location.

- Solution: Use a computer vision system to detect the well plate's position directly, rather than relying solely on pre-defined coordinates. This allows the robot to adapt to minor positional shifts [25].

Experiment-Specific Failures

Problem: Inconsistent or irreproducible solubility measurements.

- Potential Cause 1: Insufficient stabilization time for thermodynamic equilibrium.

- Solution: Ensure saturated solutions are allowed to stabilize for a sufficient duration (e.g., 8 hours) at a tightly controlled, fixed temperature [26]. Do not shorten this equilibrium time to increase throughput.

- Potential Cause 2: Solvent evaporation during long incubation periods.

- Solution: Use sealed containers to prevent solvent evaporation, which can significantly alter concentration and lead to inaccurate solubility measurements [26].

- Potential Cause 3: Inaccurate quantification method.

- Solution: Regularly validate and calibrate the analytical instrument (e.g., qNMR, UV-Vis). Use internal standards in qNMR to ensure quantitative accuracy [26].

Problem: Scheduled tests or reactions do not initiate or run correctly.

- Potential Cause 1: Agent not checking in with the control server.

- Solution: Verify that the robotic platform or control agent can communicate with the central server. Check the network connection, ensure no firewalls are blocking communication, and confirm the controller URL is accessible [27].

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect agent labeling or test assignment.

- Solution: On the control software, confirm that the correct agent label has been created and applied to the test. Verify that the agent is actively matching the label's criteria and that the test itself is enabled [27].

- Potential Cause 3: Oversubscription of tests to a single agent.

- Solution: Check that the same agent has not been matched to more tests than it can handle concurrently (e.g., a platform may be limited to 10 scheduled tests at a time). Review and adjust the agent-label assignments [27].

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and Machine Learning (ML) Integration

Problem: The active learning algorithm is not efficiently navigating the chemical space.

- Potential Cause 1: Poor initial dataset.

- Solution: The initial set of experiments should be selected using a space-filling algorithm like Sobol sampling to maximize the diversity and coverage of the initial parameter space, providing a robust foundation for the model [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Inappropriate balance between exploration and exploitation.

- Solution: Adjust the acquisition function's parameters. To focus on finding the absolute best conditions, increase exploration. To refine a promising set of conditions, increase exploitation. For multiple objectives, use a scalable multi-objective function like q-NParEgo or TS-HVI [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical throughput gain of using an automated HTE platform compared to manual methods? A: The throughput improvement is substantial. One study reported that an automated platform for thermodynamic solubility measurements required approximately 39 minutes per sample when processing 42 samples in a batch. In contrast, manual processing of samples one-by-one required about 525 minutes per sample—making the automated workflow more than 13 times faster [26].

Q2: How does machine learning, specifically active learning, accelerate reaction optimization? A: Active learning, often using Bayesian optimization, guides the experimental workflow by using a surrogate model to predict the outcomes of untested experiments. An acquisition function then suggests the next most informative experiments to run. This strategy can identify high-performing conditions by testing only a small fraction of the total search space. For example, optimal electrolyte solvents were discovered by evaluating fewer than 10% of a 2000-candidate library [26] [1].

Q3: What are the key differences between global and local machine learning models for reaction optimization? A:

- Global Models: Trained on large, diverse datasets (e.g., millions of reactions from databases like Reaxys). They are broad in scope and can recommend general conditions for a wide range of reaction types, making them useful for computer-aided synthesis planning [15].

- Local Models: Focus on a single reaction family or a specific transformation. They are trained on smaller, high-fidelity HTE datasets (often including failed experiments) and are used to fine-tune parameters like concentration and temperature to maximize yield or selectivity for that specific reaction [15].

Q4: Our robotic platform is not updating to the latest software package. What should we check? A:

- Check-in Status: Ensure the agent is regularly checking in with the controller, as updates are distributed this way. If check-ins are failing, resolve network or service issues first [27].

- Automatic Updates: Confirm that your environment allows for automatic downloads from the update domain and that it is not being blocked by a firewall or proxy [27].

- Manual Installation: In restricted environments, automatic updates may not work. Contact your system administrator to perform a manual update using the official software package [27].

Q5: What are the best practices for ensuring high-quality, reproducible data in automated solubility screening? A:

- Control Experimental Conditions: Strictly control temperature and stabilization time across all samples to ensure thermodynamic equilibrium is reached [26].

- Include Control Samples: Use control samples (e.g., a known concentration of solute in a standard solvent) in every batch to monitor and validate the consistency and precision of the platform over time [26].

- Use Robust Quantification: Employ quantitative analytical methods like qNMR for accurate concentration determination [26].

Key Experimental Protocols & Data

Automated Workflow for Solubility Measurement

This protocol details the high-throughput determination of thermodynamic solubility for redox-active molecules, as used in redox flow battery research [26].

- Sample Preparation: A robotic arm dispenses precise amounts of solid powder and organic solvent into vials to create solute-excess saturated solutions.

- Stabilization: The vials are agitated and held at a fixed temperature (e.g., 20 °C) for a defined period (e.g., 8 hours) to ensure thermodynamic equilibrium is reached.

- Liquid Sampling: After stabilization, the robotic system automatically transfers a sample of the saturated solution into an analysis vial or NMR tube.

- Quantitative Analysis: The concentration of the solute in the saturated solution is determined using a quantitative method, such as Quantitative NMR (qNMR).

- Data Processing: The molar solubility (in mol L⁻¹) is calculated from the analytical data.

Table 1: Throughput Comparison: Manual vs. Automated Solubility Screening

| Method | Samples per Batch | Time per Sample | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual (One-by-one) | 1 | ~525 minutes | Traditional "excess solute" / shake-flask method [26] |

| Automated HTE Platform | 42+ | ~39 minutes | Automated "excess solute" method with parallel processing [26] |

Machine Learning-Guided Reaction Optimization

This protocol describes a closed-loop workflow for optimizing chemical reactions, such as cross-couplings, using an HTE platform guided by Bayesian optimization [1].

- Define Search Space: A combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions is defined, including categorical variables (e.g., solvent, ligand) and continuous variables (e.g., temperature, concentration).

- Initial Sampling: An initial batch of experiments is selected using a space-filling algorithm like Sobol sampling to explore the search space broadly.

- Execution & Analysis: The selected reactions are executed on the HTE platform, and the outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) are measured.

- Model Training & Proposal: A machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process) is trained on the collected data. An acquisition function then uses the model's predictions and uncertainties to propose the next batch of experiments that best balance exploration and exploitation.

- Iteration: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated for several iterations until performance converges or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Table 2: Comparison of Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions for Large Batch Sizes

| Acquisition Function | Full Name | Suitability for Large Batches |

|---|---|---|

| q-NParEgo | q-Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm | Highly scalable; uses random scalarization to handle multiple objectives [1] |

| TS-HVI | Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement | Scalable; uses random samples from the model to select diverse batches [1] |

| q-EHVI | q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement | Less scalable; computational load increases exponentially with batch size [1] |

Workflow Diagrams

HTE-ML Closed-Loop Optimization

Robotic Solubility Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HTE in Reaction and Solubility Optimization

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Redox-Active Organic Molecules (ROMs) | Act as the electroactive material in nonaqueous redox flow batteries (NRFBs); solubility is a key performance parameter. | 2,1,3-benzothiadiazole (BTZ) [26] |

| Organic Solvent Library | To screen for optimal solubility of ROMs or to serve as the reaction medium. | A curated list of 22 single solvents (e.g., ACN, DMF) and their 2079 binary combinations [26] |

| Catalyst/Ligand Library | To enable and optimize catalytic reactions, such as cross-couplings. | Nickel- or palladium-based catalysts with diverse phosphine ligands [1] |

| qNMR Reference Standard | Provides an internal standard for quantitative concentration analysis in NMR spectroscopy. | A known concentration of a stable compound in a deuterated solvent [26] |

| Disposable Pipette Tips | Ensures sterility and prevents cross-contamination during liquid handling steps. | Removable 10 mL pipette tips used with custom digital pipettes [25] |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Model Selection

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a global model and a local model in reaction optimization?

- Answer: The distinction lies in their scope, data requirements, and primary application.

- Global Models are trained on large, diverse datasets covering many reaction types. Their strength is broad applicability, making them suitable for tasks like Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) to recommend general conditions for entirely new reactions [15].

- Local Models are specialized for a single reaction family or a specific chemical transformation. They are trained on smaller, high-quality datasets, often from High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), and are used to fine-tune parameters like catalyst, solvent, and temperature to maximize yield and selectivity for that specific reaction [15].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between a global and local model for my project?

- Answer: The choice depends on your project's stage and goal. The following table outlines the key decision factors:

| Feature | Global Model | Local Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Initial screening, CASP, suggesting conditions for novel reactions [15] | Fine-tuning and optimizing a specific, known reaction [15] |

| Data Requirements | Large & diverse (millions of reactions from databases like Reaxys, ORD) [15] | Focused & deep (HTE data for one reaction family, often <10k datapoints) [15] |

| Optimal Stage of R&D | Early discovery, route scouting [15] | Late-stage optimization, process chemistry [15] |

| Key Advantage | Broad applicability across chemical space [15] | High precision and performance for a targeted reaction [15] |

FAQ 3: What are common data quality issues, and how can they be mitigated?

- Answer: Two major issues are selection bias and yield definition discrepancies [15].

- Selection Bias: Large commercial databases often only report successful reactions, omitting failed experiments (zero yields). This can lead to models that overestimate expected yields [15].

- Mitigation: Whenever possible, incorporate internal HTE data that includes failed experiments. When using public data, be aware of this inherent bias [15].

- Yield Definition: Literature yields can be derived from different methods (isolated yield, crude NMR, LC area %), leading to inconsistent data [15].

- Mitigation: Standardize data processing protocols. For local models, ensure all yields are measured using a consistent, documented method [15].

Troubleshooting: Experimental Implementation

Issue 1: My global model suggests implausible reaction conditions.

- Solution: This is often a "out-of-domain" problem where the model encounters a reaction type not well-represented in its training data.

- Step 1: Check the model's confidence score or applicability domain assessment, if available.

- Step 2: Use the global model's output as a starting point for literature search, not a definitive recipe.

- Step 3: Consider initiating a local HTE campaign to generate relevant data and build a specialized local model for your specific reaction [15].

Issue 2: My local model is overfitting to the limited HTE data.

- Solution: Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying relationship.

- Step 1: Employ Bayesian Optimization (BO) for your experimental design. BO is efficient at navigating the parameter space with fewer experiments and inherently balances exploration and exploitation [15] [28].

- Step 2: Ensure your HTE dataset is well-designed to cover the parameter space (e.g., using Design of Experiments) rather than collecting random points.

- Step 3: Use techniques like cross-validation during model training to detect overfitting. Simplify the model or increase training data if necessary [29].

Issue 3: The algorithm fails to converge during Bayesian Optimization.

- Solution:

- Step 1: Re-scale your input parameters (e.g., temperature, concentration) so they have comparable ranges (e.g., 0-1).

- Step 2: Re-evaluate the choice of the acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound). Adjust its parameters to change the balance between exploring new areas and exploiting known good ones.

- Step 3: Check for and potentially remove any outliers in the existing data that could be skewing the model's understanding of the response surface.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Local Model with HTE and Bayesian Optimization

This protocol details the workflow for optimizing a specific reaction, such as a Buchwald-Hartwig amination.

1. Objective Definition:

- Define the Key Performance Indicator (KPI), typically reaction yield or selectivity.

- Identify the critical variables to optimize (e.g., ligand, base, solvent, temperature, concentration).

2. High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE):

- Design: Create a screening matrix that efficiently samples the defined variable space. This can be a full factorial design for a small number of variables or a sparse sampling method (e.g., Plackett-Burman) for larger spaces.

- Execution: Conduct the reactions using an automated liquid handling platform in a 96- or 384-well plate format.

- Analysis: Use high-throughput analytics, such as UPLC-MS, to quantify the yield for each reaction condition [15].

3. Model Building & Optimization:

- Algorithm Selection: Select a regression algorithm like Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) or Random Forest to build a model that predicts yield based on the input conditions.

- Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- The model proposes the next most promising experiment(s) based on the acquisition function.

- The proposed conditions are tested experimentally in the lab.

- The new result is added to the training dataset.

- The model is updated with the new data.

- Convergence: The loop continues until a predefined stopping criterion is met (e.g., yield target achieved, minimal improvement over several iterations, or budget exhausted) [15] [28].

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Protocol 2: Implementing a Global Model for Reaction Condition Recommendation

1. Data Sourcing and Curation:

- Sources: Obtain data from large-scale databases like Reaxys, Pistachio, or the open-access Open Reaction Database (ORD) [15].

- Curation: This is a critical step. The data must be cleaned and standardized. This includes:

- Reaction Mapping: Correctly identifying and mapping atoms from reactants to products.

- Standardization: Standardizing chemical structures and names for reagents and solvents.

- Extraction: Consistently extracting reaction conditions (e.g., temperature, time, yield) from text or data fields [15].

2. Model Training:

- Input Representation: Reactions are converted into a machine-readable format, often using SMILES strings or molecular fingerprints [15].

- Algorithm: Train a classification or recommendation model. Common approaches include transformer-based architectures, random forests, or collaborative filtering [15] [28].

- Output: The model learns to predict the most probable reagents, solvents, or catalysts for a given reaction transformation.

3. Validation and Application:

- Validation: The model's performance is tested by holding out a portion of the data and checking if it can correctly predict the known conditions.

- Application: The trained model is integrated into a CASP tool. When a chemist draws a new reaction, the model suggests a set of plausible conditions based on learned chemical similarities [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key resources and their functions for implementing ML-guided reaction optimization.

| Category | Item / Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Open Reaction Database (ORD) | An open-source initiative to collect and standardize chemical synthesis data; serves as a benchmark for global model development [15]. |

| Reaxys, SciFinderⁿ, Pistachio | Large-scale, proprietary commercial databases containing millions of reactions for training comprehensive global models [15]. | |

| Software & Algorithms | Bayesian Optimization (BO) | A sequential learning strategy for optimizing expensive black-box functions; ideal for guiding HTE campaigns with local models [15] [28]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A powerful ML algorithm that provides uncertainty estimates along with predictions, making it well-suited for use with BO [15]. | |

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Robust ensemble learning algorithms effective for both classification (global models) and regression (local models) tasks on structured data [15] [29]. | |

| Experimental Platforms | High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Automated platforms for rapidly conducting hundreds to thousands of micro-scale parallel reactions to generate data for local models [15]. |

| Automated Flow Synthesis | Robotic platforms that enable continuous, automated synthesis; can be integrated with ML models for self-optimizing systems [15]. |

Model Selection and Application Workflow

The following diagram provides a decision pathway to help researchers choose the appropriate modeling strategy.

Bayesian Optimization and Active Learning for Efficient Experimental Design

For researchers in drug development and chemical synthesis, optimizing reaction conditions is a fundamental yet resource-intensive challenge. Traditional methods like one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) are inefficient for complex, multi-parameter systems as they ignore critical variable interactions and often miss the global optimum [30]. Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Active Learning present a paradigm shift, enabling intelligent, data-efficient experimental design. These machine learning approaches sequentially guide experiments by balancing the exploration of unknown conditions with the exploitation of promising results, significantly accelerating the optimization of objectives like yield, selectivity, and cost [30] [1]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for implementing these powerful techniques in your research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

1. My Bayesian Optimization model is not converging to a good solution. What could be wrong? This is often due to an poorly chosen acquisition function or an inadequate surrogate model. For multi-objective problems common in chemistry (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost), ensure you are using a scalable acquisition function like q-NParEgo, TS-HVI, or q-NEHVI, especially when working with large parallel batches (e.g., 96-well plates) [1]. Furthermore, the presence of significant experimental noise can confuse standard models; in such cases, consider implementing noise-robust methods or multi-fidelity modeling to improve performance [30] [1].

2. How do I efficiently incorporate categorical variables, like solvents or catalysts, into my optimization? Categorical variables are crucial but challenging. The recommended approach is to represent the reaction space as a discrete combinatorial set of plausible conditions, automatically filtering out impractical combinations (e.g., a temperature exceeding a solvent's boiling point) [1]. Molecular entities can be converted into numerical descriptors for the model. Algorithmic exploration of these categorical parameters first helps identify promising regions, after which continuous parameters (e.g., concentration, temperature) can be fine-tuned [1].

3. How can I reduce the number of physical experiments needed? Active Learning is key. Instead of random sampling, use an uncertainty-guided sampling strategy. The model should prioritize experiments where its predictions are most uncertain or where the potential for improvement is highest. Starting the optimization process with a space-filling design like Sobol sampling can also maximize initial knowledge and help the algorithm find promising regions faster [1].

4. What are the best practices for designing the initial set of experiments? A well-designed initial set is critical for bootstrapping the BO process. Use quasi-random Sobol sampling to select initial experiments that are diversely spread across the entire reaction condition space [1]. This maximizes the coverage of your initial data, increasing the likelihood of discovering informative regions that contain optimal conditions and preventing the algorithm from getting stuck in a suboptimal local area early on.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Performance | Slow convergence or poor results in high-dimensional spaces. | Use scalable acquisition functions (e.g., TS-HVI) and ensure numerical descriptors for categorical variables are meaningful [1]. |

| Experimental Noise | Model is misled by high variance in experimental outcomes (common in chemistry). | Integrate noise-robust methods and use signal-to-noise ratios in analysis to find robust settings [31] [30]. |

| Resource Management | Need to optimize multiple competing objectives (e.g., yield, selectivity, cost). | Implement Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO). Track performance with the hypervolume metric to ensure diverse, high-quality solutions [1]. |

| Physical Constraints | The algorithm suggests conditions that are unsafe or impractical. | Define the search space as a discrete set of pre-approved plausible conditions, automatically excluding unsafe combinations [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the core iterative workflow for using BO in a chemical synthesis setting [30] [1].

- Define the Problem: Formally state your objectives (e.g., maximize yield, maximize selectivity) and identify all variables (e.g., temperature, concentration, solvent, catalyst).

- Establish the Search Space: Define the plausible range for each continuous variable and the list of options for each categorical variable. Use domain knowledge to filter out unsafe or impractical combinations.

- Initial Sampling: Select an initial set of experiments (typically 10-20% of your total experimental budget) using Sobol sampling to ensure broad coverage of the search space [1].

- Run Experiments & Collect Data: Execute the initial experiments and record the outcomes for your defined objectives.