Robustness Testing in Organic Analytical Procedures: A Complete Guide to QbD, Method Validation, and Regulatory Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive guide to robustness testing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with organic analytical procedures.

Robustness Testing in Organic Analytical Procedures: A Complete Guide to QbD, Method Validation, and Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to robustness testing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with organic analytical procedures. Covering the entire method lifecycle, it explains foundational principles based on ICH guidelines, demonstrates practical methodological approaches using experimental design, offers troubleshooting strategies for common issues, and clarifies validation requirements for regulatory compliance. By adopting the Quality by Design (QbD) framework outlined here, professionals can develop more reliable analytical methods, reduce out-of-specification results, and ensure successful method transfer and regulatory submissions.

Understanding Robustness Testing: Definitions, Importance, and Regulatory Foundations

What is Robustness Testing? ICH Q2(R2) and USP Definitions

Robustness testing is a critical component of analytical procedure validation, serving as a measure of a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters. Robustness provides an indication of the procedure's reliability and suitability during normal usage conditions by demonstrating that method performance remains consistent despite expected fluctuations in analytical conditions [1]. Within the pharmaceutical industry, robustness is formally defined by both the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) as a measure of an analytical procedure's ability to resist changes when subjected to minor modifications in procedural parameters specified in the method documentation [1] [2].

While often confused with related terms, robustness maintains distinct characteristics. Ruggedness, as defined by USP, refers to the degree of reproducibility of test results under a variety of normal conditions such as different laboratories, analysts, instruments, and reagent lots. The ICH guideline does not use the term "ruggedness" but addresses similar concepts under "intermediate precision" (within-laboratory variations) and "reproducibility" (between-laboratory variations) [1]. A practical rule of thumb distinguishes these concepts: if a parameter is written into the method (e.g., 30°C, 1.0 mL/min), it constitutes a robustness issue. If it is not specified in the method (e.g., which analyst runs the method or which specific instrument is used), it falls under ruggedness or intermediate precision [1].

Regulatory Framework: ICH Q2(R2) and USP

ICH Q2(R2) Perspective

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," establishes robustness as a fundamental validation element. According to the most recent ICH Q2(R2) implementation, robustness is "tested by deliberate variations of analytical procedure parameters" [2]. This guideline emphasizes that analytical procedure validation serves as proof that a method is fit for its intended purpose throughout the procedure's entire lifecycle, not merely as a one-time activity [2]. The scope of ICH Q2(R2) applies to procedures for release and stability testing of drug substances and products, though it can also extend to other control strategy tests when justified by risk assessment [2].

USP Chapter 1225 Perspective

USP Chapter 1225, "Validation of Compendial Methods," similarly defines robustness as a measure of the analytical procedure's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1]. Recent revisions to USP Chapter 1225 have aimed to harmonize more closely with ICH guidelines, including replacing references to "ruggedness" with "intermediate precision" [1]. Interestingly, while robustness appears in both ICH and USP guidelines, it has not traditionally been included in the list of suggested analytical characteristics used to validate a method, though this is changing in recent proposed revisions to USP Chapter 1225 [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Regulatory Definitions

| Aspect | ICH Q2(R2) | USP Chapter 1225 |

|---|---|---|

| Terminology | Prefers "Intermediate Precision" | Traditionally used "Ruggedness" but moving toward ICH terminology |

| Definition | Measure of capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations | Measure of capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations |

| Regulatory Status | Required validation element | Required validation element |

| Lifecycle Approach | Explicitly states validation continues throughout procedure lifecycle | Implied through ongoing suitability requirements |

| Focus | Reliability during normal use | Reliability during normal use |

Experimental Design for Robustness Studies

Key Parameters for Testing

Robustness testing involves the intentional variation of method parameters to assess their impact on method performance. The specific parameters selected for variation depend on the analytical technique, but common examples in chromatography include [1]:

- Mobile phase composition (number, type, and proportion of organic solvents)

- Buffer composition and concentration

- pH of the mobile phase

- Different column lots or suppliers

- Temperature (column, sample)

- Flow rate

- Detection wavelength

- Gradient variations (hold times, slope, length)

For dissolution testing, key parameters might include [3]:

- Media composition (buffer concentration, pH, surfactant percentage)

- Dissolution apparatus (brand, model, age)

- Paddle/basket height (typically varied by ±2mm)

- RPM speed

- Degassing method and dissolved gas levels

- Sinker design and construction

Experimental Design Approaches

Robustness studies have traditionally employed univariate approaches (changing one variable at a time), but modern practice favors multivariate experimental designs that allow multiple variables to be studied simultaneously. This approach is more efficient and enables detection of interactions between variables [1]. The most common experimental designs for robustness studies include:

Full Factorial Designs

In a full factorial design, all possible combinations of factors are measured at high and low values. If there are k factors, each at two levels, a full factorial design has 2^k runs. For example, with four factors, there would be 16 design points [1]. While comprehensive, full factorial designs become impractical with more than five factors due to the exponentially increasing number of runs [1].

Fractional Factorial Designs

Fractional factorial designs use a carefully chosen subset of the factor combinations from a full factorial design, significantly reducing the number of runs required. These designs work on the "scarcity of effects principle" - while many factors may exist, typically only a few are truly important [1]. The reduced number of runs comes with the tradeoff of some factors being "aliased" or confounded with other factors, requiring careful design selection [1].

Plackett-Burman Designs

Plackett-Burman designs are highly efficient screening designs particularly suited for robustness testing where the primary goal is determining whether a method is robust to many changes rather than quantifying each individual effect [1]. These economical designs work in multiples of four rather than powers of two and are ideal when only main effects are of interest [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Design Approaches

| Design Type | Number of Runs | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | 2^k (where k = factors) | Identifies all interactions; no confounding | Number of runs grows exponentially | Small number of factors (<5) |

| Fractional Factorial | 2^(k-p) (where p = fraction) | Balanced; efficient for multiple factors | Some confounding of interactions | Medium number of factors (5-10) |

| Plackett-Burman | Multiples of 4 | Highly efficient for many factors | Only evaluates main effects | Screening many factors (>10) |

Implementation Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Approach to Robustness Testing

Implementing a successful robustness study requires a structured approach:

Parameter Selection: Identify which method parameters to test based on risk assessment and knowledge gained during method development. Focus on parameters most likely to vary during routine use or those identified as potentially impactful during development [1] [3].

Range Definition: Establish appropriate high and low values for each parameter based on expected variations in normal laboratory conditions. These ranges should represent "reasonable but deliberate" variations that might occur during method transfer or routine application [1].

Experimental Design: Select the most appropriate experimental design based on the number of parameters, available resources, and required information about interactions [1].

Execution and Data Collection: Conduct the experiments according to the design, ensuring proper documentation of all conditions and results.

Data Analysis: Evaluate the effects of parameter variations on critical method performance characteristics, typically focusing on resolution, tailing factor, capacity factor, and precision [1].

Establishment of System Suitability: Use results from robustness testing to establish appropriate system suitability parameters that will ensure method validity during routine use [1].

Analytical Procedure

A typical robustness study for a chromatographic method follows this workflow:

Acceptance Criteria

While specific acceptance criteria depend on the analytical method and its intended purpose, generally, a method is considered robust when all measured responses remain within specified acceptance criteria despite the introduced variations. For chromatographic methods, this typically means maintaining [1] [2]:

- Resolution between critical pairs above specified minimum

- Tailing factor within acceptable limits

- Theoretical plates meeting minimum requirements

- Precision (RSD) within acceptable ranges

- Accuracy remaining within specified limits

For dissolution testing, acceptance criteria typically focus on maintaining dissolution results within acceptable ranges at specified timepoints, particularly at the Q value timepoint and last timepoint [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing effective robustness studies requires specific materials and tools designed for pharmaceutical analysis. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their functions in robustness testing:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Robustness Testing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Robustness Testing | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantification and system suitability verification | USP reference standards; impurity standards |

| Chromatographic Columns | Different lots/sources to test column robustness | C18, C8, phenyl, and other stationary phases |

| Buffer Components | Variation in mobile phase composition | Phosphate, acetate buffers at different pH and concentration |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Variation in organic modifier type and proportion | Methanol, acetonitrile of different lots and suppliers |

| Surfactants | Testing media robustness in dissolution | Sodium lauryl sulfate, polysorbates |

| Dissolution Media | Testing robustness to media variations | Different pH buffers, biorelevant media |

| Column Heater/Chiller | Controlling and varying temperature parameters | Testing temperature effects on separation |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical Evaluation

Robustness study data requires appropriate statistical analysis to distinguish significant effects from normal experimental variation. The experimental designs previously described facilitate this analysis through structured comparison of variations. For full and fractional factorial designs, statistical analysis typically includes [1] [4]:

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to identify significant factors

- Main effects plots to visualize parameter effects

- Interaction plots to identify significant interactions between parameters

- Normal probability plots to distinguish significant effects from noise

The statistical evaluation should focus on both the magnitude of effects and their practical significance. While a parameter variation might produce a statistically significant effect, it may not be practically significant if the method performance remains within acceptance criteria [1].

Response Surface Methodology

For more complex robustness studies, response surface methodology may be employed to model the relationship between parameter variations and method responses. This approach is particularly valuable when curvature is suspected in the response and enables the identification of optimal parameter settings that maximize robustness [1] [4].

Case Studies and Practical Applications

Chromatographic Method Example

A robustness study for an HPLC assay method might investigate the effects of variations in mobile phase pH (±0.2 units), organic composition (±2%), column temperature (±3°C), and flow rate (±0.1 mL/min) using a fractional factorial design. The responses measured would typically include retention time, resolution between critical pairs, tailing factor, and theoretical plates. The results would establish acceptable ranges for each parameter to be included in the method documentation [1].

Dissolution Method Example

For dissolution testing, a robustness study might examine the effects of media pH (±0.2 units), surfactant concentration (±10%), deaeration level, and apparatus model (different vendors). The study would evaluate dissolution results at key timepoints, particularly the Q value timepoint, to establish the method's robustness to these variations [3].

Robustness testing represents a critical element of the analytical procedure validation lifecycle, providing assurance that methods will perform reliably under the normal variations encountered during routine use in pharmaceutical quality control laboratories. The ICH Q2(R2) and USP guidelines provide aligned definitions and expectations for robustness testing, emphasizing its role in demonstrating method reliability.

Through appropriate experimental design—including full factorial, fractional factorial, or Plackett-Burman designs—and careful data analysis, robustness testing identifies critical method parameters and establishes acceptable operating ranges. This not only ensures method reliability but also informs system suitability criteria and method documentation, ultimately supporting robust pharmaceutical manufacturing and control strategies.

As regulatory guidance continues to evolve, with ICH Q2(R2) emphasizing a lifecycle approach to method validation, robustness testing remains fundamental to demonstrating that analytical procedures are fit for their intended purpose throughout their operational lifetime.

In analytical chemistry, the reliability of a method is paramount, especially in regulated industries like pharmaceuticals. While the terms "robustness" and "ruggedness" are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent two distinct pillars of method validation. Robustness is the measure of a method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in its internal procedural parameters. In contrast, ruggedness evaluates the reproducibility of test results under varying external conditions, such as different analysts, instruments, or laboratories [1] [5]. Understanding this distinction is critical for developing, validating, and successfully transferring analytical methods, ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance throughout a drug's lifecycle.

Core Concepts: A Side-by-Side Comparison

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between robustness and ruggedness, highlighting their unique focuses, objectives, and applications.

| Feature | Robustness Testing | Ruggedness Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Measures stability against small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1] [6]. | Measures reproducibility of results under varying external conditions [7] [5]. |

| Nature of Variations | Internal, controlled, and deliberate changes to parameters written into the method [1] [5]. | External, environmental factors that are expected to occur in normal use [6] [8]. |

| Primary Objective | Identify critical method parameters and establish controllable ranges [1] [9]. | Ensure method reproducibility and facilitate successful method transfer [7] [5]. |

| Typical Scope | Intra-laboratory study, performed during method development [1] [5]. | Often an inter-laboratory study, performed later in validation or during transfer [5]. |

| Key Question | "How well does the method withstand minor tweaks to its defined parameters?" [5] | "How well does the method perform across different settings, analysts, and instruments?" [5] |

| Example Variables | Mobile phase pH, flow rate, column temperature, wavelength [1] [6]. | Different analysts, instruments, laboratories, reagent lots, and days [1] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robustness Testing

A key outcome of robustness testing is the definition of a Method Operable Design Region (MODR), a multidimensional space where the method delivers consistent, reliable performance despite minor parameter fluctuations [9]. Scientifically rigorous experimental design is crucial for an efficient and informative robustness study.

Experimental Designs and Workflows

The univariate, or one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach, is time-consuming and fails to detect interactions between variables [1]. Multivariate screening designs are more efficient, allowing for the simultaneous study of multiple variables.

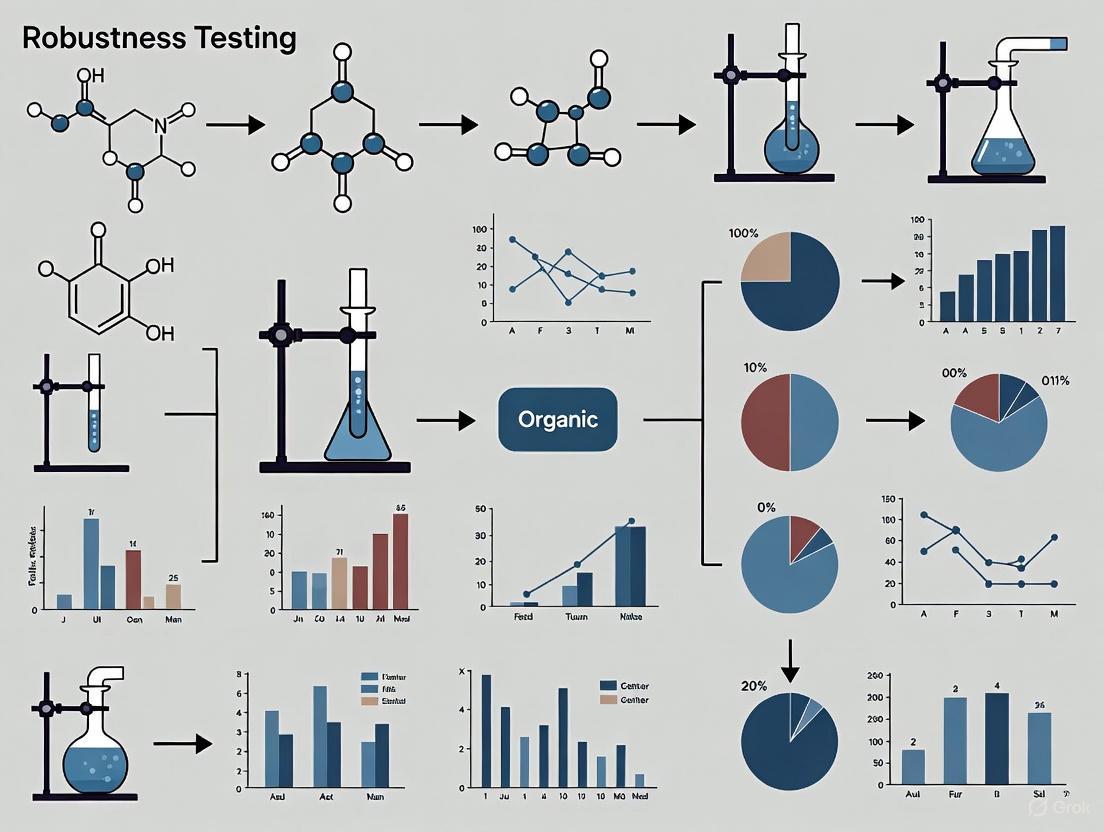

Figure: Robustness testing workflow from planning to establishing a validated method, showing design selection based on factor number.

- Full Factorial Designs: A full factorial design investigates all possible combinations of factors at their high and low levels. For k factors, this requires 2^k runs. This design is powerful but becomes impractical with more than four or five factors due to the exponentially increasing number of experiments [1].

- Fractional Factorial Designs: These designs are a carefully chosen subset (a fraction) of the full factorial runs. They are highly efficient for screening a larger number of factors (e.g., five or more) and are based on the principle that higher-order interactions are often negligible. The trade-off is that some effects may be confounded, requiring careful design selection [1].

- Plackett-Burman Designs: This type of design is an extremely efficient screening tool used to identify the most critical factors from a large set (e.g., 11 factors in 12 experimental runs). It is primarily used to estimate main effects economically and is ideal for situations where many factors need to be investigated with minimal experimental effort [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table lists essential materials and their functions in a robustness study for a chromatographic method.

| Item | Function in Robustness Testing |

|---|---|

| HPLC/UHPLC System | Instrument platform for executing separations; performance is validated through system suitability tests. |

| Chromatographic Column | Stationary phase; testing different column lots and/or suppliers is a critical robustness variable [1] [6]. |

| Organic Solvents & Buffers | Components of the mobile phase; variations in their composition, pH, and concentration are tested [1] [5]. |

| Analytical Reference Standards | High-purity compounds used to prepare samples with known concentrations for evaluating method performance. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | Reference mixtures used to verify that the chromatographic system is performing adequately before analysis. |

Experimental Protocols for Ruggedness Testing

Ruggedness testing, sometimes assessed under the umbrella of intermediate precision (within-laboratory variations) and reproducibility (between-laboratory variations), simulates the real-world variability a method will encounter [1]. The Youden test is a recognized, efficient method for ruggedness evaluation [10].

The Youden Test and Collaborative Studies

- The Youden Test: This method uses fractional factorial designs to assess the impact of multiple external factors with a minimal number of experiments. It is a highly efficient approach that conserves time and resources while providing essential data on the method's susceptibility to variations between analysts, instruments, or laboratories [10].

- Collaborative Study Design: A full ruggedness study may involve a formal inter-laboratory collaborative trial. In this design, identical samples and the fully documented method procedure are distributed to multiple participating laboratories. Each laboratory performs the analysis, and the results are compiled and statistically evaluated to determine the method's reproducibility across different environments [5].

Figure: Ruggedness testing workflow from sample preparation through multi-laboratory analysis to establish reproducibility criteria.

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Development

The principles of robustness and ruggedness are integral to modern pharmaceutical quality systems. A proactive approach to robustness, guided by Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles, is increasingly adopted to build reliability directly into the method from the start [9].

- A Proactive "Robustness-First" Mindset: Instead of treating robustness as a final validation check, AQbD encourages its investigation during the method development phase. This involves using systematic, multivariate experiments to understand the relationship between method parameters and performance outcomes, thereby defining a robust MODR early on [1] [9].

- Regulatory and Business Impact: A method validated with a thorough understanding of its robustness and ruggedness is more likely to avoid costly out-of-specification (OOS) results during routine use. This enhances regulatory compliance, smoothens method transfer between sites, and reduces the need for post-approval changes, leading to significant long-term cost and time savings [5] [9].

For researchers and drug development professionals, a clear and applied understanding of the distinction between robustness and ruggedness is non-negotiable. Robustness is an internal stress-test of the method's parameters, defining its operational boundaries and ensuring stability against minor fluctuations. Ruggedness is the ultimate test of a method's real-world applicability, proving its reproducibility across the different analysts, instruments, and environments inherent in a global industry. By systematically implementing rigorous experimental protocols for both, scientists can ensure the generation of reliable, high-quality data that safeguards product quality and patient safety from development through commercial manufacturing.

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical industry, the robustness of an analytical method is a critical parameter defined as a measure of its capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and provide unbiased results under normal usage conditions [11] [1]. This concept extends beyond simple error-checking to become a fundamental safeguard for data integrity, product quality, and patient safety throughout the drug development lifecycle. As regulatory guidance emphasizes through frameworks like ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, understanding robustness is not merely a compliance exercise but a scientific necessity for establishing reliable, trustworthy analytical procedures [1] [9].

The distinction between robustness and related validation parameters is crucial. While ruggedness (increasingly termed intermediate precision) refers to a method's reproducibility under varying external conditions such as different laboratories, analysts, or instruments, robustness specifically tests the method's resilience to intentional, internal parameter modifications [1]. Essentially, if a parameter is written into the method protocol (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate), testing its impact falls under robustness evaluation. This systematic assessment of a method's "edge of failure" provides scientists and regulators with confidence that the procedure will perform consistently, even when minor, inevitable operational variations occur in different laboratory environments [9].

The Critical Role of Robustness in Pharmaceutical Quality Systems

Foundation of Data Integrity and Product Quality

Robust analytical methods form the bedrock of data integrity—ensuring data remain accurate, consistent, and reliable throughout their lifecycle [12]. In pharmaceutical development, decisions regarding drug safety, efficacy, and quality are entirely dependent on analytical data. A method lacking robustness may produce biased or unreliable results when subjected to normal laboratory variations, leading to costly out-of-specification investigations, batch rejections, or worse, compromised patient safety [9].

The relationship between robustness and quality is direct and consequential. Robust methods demonstrate consistent performance, which translates to reliable potency assays, accurate impurity profiling, and trustworthy stability data. This reliability is paramount for making critical decisions during formulation development, establishing shelf life, and ensuring consistent product quality throughout commercial manufacturing. Furthermore, the implementation of a robustness study aligns with the Quality by Design (QbD) framework endorsed by FDA and ICH guidelines, shifting the quality paradigm from traditional quality-by-testing to a more systematic, science-based approach [9].

Economic and Regulatory Implications

Investing in robustness testing during method development provides significant economic returns by reducing failures during method transfer and routine use. The cost of remediating a non-robust method post-implementation far exceeds the investment in proper upfront evaluation [1]. As one white paper notes, inconsistent method performance can lead to "failure of the System Suitability Testing (SST) requiring redevelopment and regulatory approval, impacting cost and time" [9].

From a regulatory perspective, demonstrating method robustness provides confidence in the reliability of submitted data and supports regulatory flexibility. When a Method Operable Design Region (MODR) is established, changes within this proven robustness space may not require regulatory submissions, streamlining post-approval improvements [9].

Experimental Design for Robustness Evaluation

Key Method Parameters for Testing

Robustness testing in chromatographic methods involves deliberately varying critical method parameters to assess their impact on performance indicators such as resolution, tailing factor, and precision. Based on regulatory guidance and industry practice, the following parameters are typically evaluated:

- Mobile Phase Composition: Number, type, and proportion of organic solvents [1]

- pH of the mobile phase: Variations within a specified range [1]

- Buffer Concentration: Changes in molarity [1]

- Column Temperature: Fluctuations around the set point [1]

- Flow Rate: Deviations from the nominal value [1]

- Detection Wavelength: Minor adjustments [1]

- Different Column Lots: To assess column-to-column variability [1]

- Gradient Variations: Changes in gradient time, slope, or hold times [1]

Statistical Design of Experiments (DoE) Approaches

Traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches to robustness testing are increasingly replaced by multivariate statistical designs that provide greater efficiency and enable detection of parameter interactions [1] [4]. The most common screening designs include:

- Full Factorial Designs: All possible combinations of factors at two levels (high and low) are measured. While comprehensive (2^k runs for k factors), they become impractical for more than five factors due to the high number of required runs [1].

- Fractional Factorial Designs: A carefully chosen subset of the full factorial combinations, these designs significantly reduce the number of runs while still providing valuable information about main effects, though some effects may be confounded (aliased) [1].

- Plackett-Burman Designs: Highly efficient screening designs in multiples of four runs that are ideal for evaluating a large number of factors when only main effects are of interest. These have been widely employed in robustness studies for their operational convenience [11] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for a systematic robustness evaluation using DoE:

Comparative Analysis: Robust vs. Non-Robust Methods

Performance Under Variable Conditions

The fundamental value of robustness testing becomes evident when comparing method performance under stressed conditions. The following table summarizes key performance differences:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Robust vs. Non-Robust Analytical Methods

| Performance Characteristic | Robust Method | Non-Robust Method |

|---|---|---|

| Result Reproducibility | Consistent across permitted parameter variations | Significant deviation with minor parameter changes |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Failure Rate | Low and predictable | High and unpredictable |

| Method Transfer Success | High success rate between laboratories | Frequent failures requiring investigation |

| Operational Flexibility | Tolerates normal equipment and preparation variations | Requires extremely tight control of all parameters |

| Data Integrity Assurance | Maintains accuracy and consistency under normal variations | Produces biased or unreliable results with minor changes |

| Regulatory Compliance | Easily validated and transferred | Requires multiple investigations and re-validation |

Case Study: HPLC Method Development

A practical application of robustness evaluation comes from a pharmaceutical development case study employing Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles [9]. Scientists developed an HPLC method for analyzing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their related substances. Through a systematic robustness study using a fractional factorial design, they evaluated the impact of seven critical parameters: mobile phase pH, buffer concentration, column temperature, flow rate, gradient time, and detection wavelength.

The results demonstrated that only two parameters (mobile phase pH and gradient time) had statistically significant effects on critical resolution. This finding allowed the team to establish a Method Operable Design Region (MODR) where these two parameters were tightly controlled while other parameters could vary within broader ranges without affecting method performance. This approach enhanced method understanding, reduced the risk of out-of-specification results during routine use, and provided regulatory flexibility for future adjustments within the MODR [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robustness Evaluation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Robustness Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Reference Standards | USP, EP, BP reference standards; Certified reference materials from LGC, Merck | Provide benchmark for method performance under varied conditions [13] |

| High-Purity Mobile Phase Components | HPLC-grade solvents; LC-MS grade solvents; High-purity buffers and additives | Minimize variability introduced by impurity differences between reagent lots [13] |

| Characterized Column Variants | Different column lots; Columns from multiple manufacturers; Different column ages | Assess method resilience to normal column-to-column variability [1] |

| Quality Control Samples | In-house prepared reference standards; Spiked samples with known concentrations | Monitor method performance across experimental conditions [13] |

| Statistical Software Packages | Design of Experiments (DoE) software; Multivariate analysis tools | Enable experimental design and data analysis for robustness studies [1] [4] |

Robustness is not an isolated validation parameter but a fundamental characteristic that must be integrated throughout the entire analytical method lifecycle. From initial development through transfer and routine use, understanding a method's limitations and behavior under variable conditions provides the scientific foundation for reliable data generation [9]. The implementation of systematic robustness testing using appropriate experimental designs represents a critical investment in product quality, regulatory compliance, and ultimately, patient safety.

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to embrace QbD principles, the evaluation of robustness will increasingly become an integral part of method development rather than a standalone validation activity. This paradigm shift toward proactive understanding rather than retrospective verification represents the most significant advancement in ensuring data integrity and product quality for modern pharmaceutical development.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provide the foundational framework for pharmaceutical regulation, particularly for analytical procedures. The ICH develops harmonized technical guidelines adopted by regulatory authorities worldwide to ensure global consistency in drug development and manufacturing [14]. Its "Q" series guidelines are especially influential for quality matters. The FDA, as a key founding regulatory member of ICH, subsequently adopts and implements these harmonized guidelines, making compliance with ICH standards a direct path to meeting FDA requirements for regulatory submissions [14].

For analytical method validation, the recent simultaneous release of ICH Q2(R2) on validation and ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development represents a significant modernization of the regulatory landscape [14]. This evolution shifts the focus from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" approach to a more scientific, lifecycle-based model that emphasizes a risk-based approach and built-in quality from the initial development stages [14]. Understanding this interconnected framework is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to ensure compliance and robust analytical performance.

Comparative Analysis of ICH and FDA Requirements

Core Principles and Harmonization

While the ICH and FDA maintain distinct regulatory roles, their requirements for analytical procedures are fundamentally aligned. The ICH provides the internationally harmonized scientific and technical standards, which the FDA then adopts and implements within the U.S. regulatory framework [14]. Recent updates further demonstrate this synchronization, with the FDA publishing final versions of ICH Q2(R2) in March 2024 and ICH Q14, which replaces the previous Q2(R1) guideline [15] [14].

This harmonization means that for most new drug submissions, following the latest ICH guidelines is the key to meeting FDA requirements [14]. The core principles for analytical method validation remain consistent between both bodies, focusing on scientifically sound, fit-for-purpose methods that reliably measure drug quality attributes throughout the product lifecycle.

Key Validation Parameters Under ICH Q2(R2)

ICH Q2(R2) outlines fundamental performance characteristics that must be evaluated to demonstrate a method is fit for its intended purpose [16]. The following table summarizes these core validation parameters and their definitions:

Table: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters per ICH Q2(R2)

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of test results to the true value [14]. | Analysis of a known standard or spiked placebo [14]. |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among individual test results from repeated samplings [14]. | Repeatability, intermediate precision, reproducibility [14]. |

| Specificity | Ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of potential interferents [14]. | Analysis of samples with and without impurities/degradants [14]. |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration [14]. | Series of analyte solutions across a defined range [14]. |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [14]. | Derived from linearity and precision data [14]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be detected [14]. | Signal-to-noise ratio or visual evaluation [14]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest amount of analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [14]. | Signal-to-noise ratio or specified accuracy/precision criteria [14]. |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [14]. | Experimental design (e.g., Plackett-Burman) varying parameters [17]. |

Robustness Testing: Concepts and Regulatory Significance

Definition and Importance in Method Validation

Robustness is formally defined as "the capacity of an analytical procedure to remain unaffected by small but deliberate variations in method parameters and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage" [17]. This measures a method's resilience to minor changes in experimental conditions that might occur during routine analysis, such as slight fluctuations in temperature, pH, mobile phase composition, or flow rate [11]. A robust method will produce unbiased and consistent results despite these normal variations, which is critical for ensuring data reliability and product quality throughout a method's lifecycle [11].

The importance of robustness testing extends throughout the pharmaceutical industry. For a company testing drug purity, a non-robust method could mean that minor, inevitable changes in the lab environment lead to inconsistent results, potentially delaying product release or compromising patient safety [18]. Robustness testing is therefore not merely a regulatory requirement but a fundamental exercise in ensuring the dependability and trustworthiness of analytical data used for critical decision-making [18].

Robustness vs. Ruggedness

A common point of discussion in analytical circles is the distinction between robustness and ruggedness. While sometimes used interchangeably, a more nuanced understanding exists. Ruggedness typically refers to a method's reliability when subjected to variations in external conditions, such as different laboratories, analysts, or instruments [17]. Robustness, in its more specific ICH definition, focuses on the impact of variations in internal method parameters themselves [17]. However, the consensus in the scientific literature, as concluded in multiple studies, is that these terms are often considered synonymous, with both aiming to demonstrate method reliability under realistic conditions of use [11].

Experimental Design for Robustness Evaluation

Systematic Methodology

Robustness testing requires a structured, systematic approach rather than random parameter adjustments. A well-designed robustness study involves several key steps [17]:

- Selection of Factors and Levels: Identify method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, flow rate) and environmental conditions most likely to affect results. Choose two extreme levels for each factor, symmetrically around the nominal level, representing variations expected during method transfer or routine use [17].

- Selection of Experimental Design: Choose an appropriate experimental design that allows for efficient testing of multiple factors. Screening designs like fractional factorial (FF) or Plackett-Burman (PB) are commonly used [11] [17].

- Selection of Responses: Identify key assay responses (e.g., analyte recovery, impurity content) and System Suitability Test (SST) responses (e.g., resolution, retention time) to monitor [17].

- Execution and Data Analysis: Conduct experiments according to the defined protocol, then estimate factor effects and analyze them statistically or graphically to determine their significance [17].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details essential reagents, materials, and instruments critical for conducting a proper robustness study, particularly for chromatographic methods.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Robustness Studies

| Item | Function in Robustness Testing | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC/UPLC System | Separates and detects analytes; key source of parameter variations. | Parameters like flow rate, column temperature, and detector wavelength are tested [17]. |

| Analytical Columns | Stationary phase for separation; different batches/manufacturers are a key factor. | A common robustness factor is comparing the nominal column with an alternative column from a different batch or manufacturer [17]. |

| Mobile Phase Reagents | Liquid phase for separation; composition and pH are critical factors. | Variations in organic solvent percentage, buffer concentration, and pH are frequently tested [17] [18]. |

| Reference Standards | Provides known analyte for accuracy and system suitability assessment. | Used in sample solutions to measure responses like percent recovery and resolution under varied conditions [17]. |

| Sample Material | Represents the actual matrix containing the analyte. | A representative sample (e.g., drug formulation) is measured under all design experiments [17]. |

Statistical Analysis and Interpretation

After executing the experimental design, the effect of each factor on the response is calculated. The effect of a factor (EX) is the difference between the average responses when the factor was at its high level and the average when it was at its low level [17]. These effects are then analyzed to determine their statistical and practical significance.

Common graphical tools include normal probability plots or half-normal probability plots, where non-significant effects tend to fall along a straight line and significant effects deviate from it [17]. Statistically, effects can be compared to a critical effect value derived from the experimental error. For designs with dummy factors (unassigned factors in the matrix), the standard error of an effect can be estimated from the dummy effects, and a student's t-test can be performed [17]. If significant effects are found on critical assay responses, the method may require optimization, or the problematic parameter may need to be tightly controlled in the method instructions.

The Modernized Lifecycle Approach: ICH Q2(R2) and Q14

The recent updates to ICH Q2(R2) and the new ICH Q14 guideline represent a paradigm shift in analytical procedure validation and development. The most significant change is the move from validation as a one-time event to a continuous lifecycle management approach [14]. This enhanced model promotes building quality into the method from the very beginning rather than simply testing for it at the end.

A cornerstone of this modern approach is the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), introduced in ICH Q14 [14]. The ATP is a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and its required performance criteria. By defining the ATP at the outset, development efforts are focused on creating a method that is fit-for-purpose by design. This scientific, risk-based foundation also facilitates more flexible and efficient post-approval change management. Furthermore, ICH Q2(R2) has been expanded to explicitly include guidance for modern techniques like multivariate methods, ensuring the guidelines remain relevant amidst rapid technological advancement [14].

The regulatory landscape for analytical procedures, governed by the harmonized efforts of ICH and the FDA, is evolving toward a more scientific, flexible, and robust framework. The core principles of validation, with robustness testing as a critical component, remain essential for demonstrating method reliability. The introduction of the modernized, lifecycle approach through ICH Q2(R2) and Q14, emphasizing the ATP and risk-based development, empowers scientists to build quality in from the start. For researchers and drug development professionals, successfully navigating this landscape requires a deep understanding of both the regulatory expectations and the systematic, statistically sound experimental methodologies needed to prove that an analytical procedure is truly fit for its intended purpose throughout its entire lifecycle.

The Critical Role in Pharmaceutical Analysis and Method Transfer

Analytical method transfer (AMT) is a documented process that verifies a validated analytical procedure performs consistently and reliably when moved from one laboratory to another [19]. This formal transfer is a critical pharmaceutical requirement whenever a quality control method is relocated between sites, such as from a development lab to a quality control lab, or to a contract research organization [19] [20].

The process qualifies a receiving laboratory (RL) to use a procedure developed and validated by a transferring laboratory (TL) [20]. Its core purpose is to demonstrate that the method produces equivalent results despite differences in analysts, equipment, reagents, and environmental conditions, thereby ensuring the continued reliability of data used to make decisions about drug safety and quality [19] [21]. Regulatory agencies like the FDA, EMA, and WHO require evidence of this reliability, making AMT a cornerstone of regulatory compliance and a robust pharmaceutical quality system [19].

Core Approaches to Method Transfer

Several standardized approaches exist for transferring methods, each with specific applications. The choice depends on factors like method complexity, the receiving lab's experience, and regulatory requirements [20] [22]. The most common strategies, as outlined in USP General Chapter <1224>, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Approaches for Analytical Method Transfer

| Transfer Approach | Core Principle | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Testing [19] [20] | Both labs analyze identical samples; results are statistically compared for equivalence. | Well-established, validated methods; labs with similar capabilities and equipment [21]. | Requires robust statistical analysis and homogeneous samples; most common approach [19]. |

| Co-validation [19] [22] | The receiving lab participates in the original method validation study, providing reproducibility data. | New methods or those being developed for multi-site use from the outset [21]. | Fosters shared ownership and deep method understanding; requires high collaboration [19] [22]. |

| Re-validation [19] [20] | The receiving laboratory performs a full or partial revalidation of the method. | Significant differences in lab conditions/equipment or when the sending lab is unavailable [20]. | Most rigorous and resource-intensive approach; requires a full validation protocol [21]. |

| Data Review / Waiver [19] [21] | Historical data is reviewed, or the transfer is waived based on strong justification. | Simple compendial methods with minimal risk or highly experienced receiving labs [19]. | Rarely used; requires robust scientific justification and is subject to high regulatory scrutiny [21]. |

The Central Role of Robustness Testing

Robustness is a measure of an analytical procedure's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [1]. It provides an indication of the method's inherent reliability during normal usage and is a critical predictor of its success during transfer.

Defining Robustness and Ruggedness

While often confused, robustness and ruggedness are distinct concepts. Robustness evaluates the method's sensitivity to changes in internal parameters written into the procedure, such as mobile phase pH, flow rate, column temperature, or wavelength [1]. Ruggedness, a term increasingly being replaced by "intermediate precision," refers to the method's performance under external variations, such as different analysts, instruments, or days [1]. A method demonstrating good robustness is more likely to be rugged and transfer successfully.

Experimental Design for Robustness Studies

A systematic, multivariate approach is recommended for robustness testing, as it is more efficient than changing one variable at a time and can reveal interactions between parameters [1].

- Screening Designs: These are efficient for identifying critical factors among a larger set. Common designs include [1]:

- Full Factorial: Measures all possible combinations of factors (2^k runs for k factors). Suitable for up to 5 factors.

- Fractional Factorial: A carefully chosen subset of runs from a full factorial design. Ideal for investigating more factors efficiently, though some interactions may be confounded.

- Plackett-Burman: Highly economical designs in multiples of four, used when only main effects are of interest.

Table 2: Example of Factor Variations in an HPLC Robustness Study

| Method Parameter | Nominal Value | Variation Range | Measured Impact (e.g., %RSD, Retention Time Shift) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase pH | 3.1 | ± 0.1 units | |

| Flow Rate | 1.0 mL/min | ± 0.1 mL/min | |

| Column Temperature | 30 °C | ± 2 °C | |

| % Organic in Mobile Phase | 45% | ± 2% | |

| Wavelength | 254 nm | ± 2 nm |

Protocol for a Robustness Study

The following workflow outlines a standard process for conducting a robustness study:

Best Practices for a Successful Transfer

A successful analytical method transfer is built on meticulous planning, clear communication, and rigorous documentation [19] [21].

- Comprehensive Protocol Development: A detailed, pre-approved protocol is essential. It must define the scope, responsibilities, samples, analytical procedure, pre-defined acceptance criteria, and the statistical methods for data comparison [19] [20]. The protocol requires approval from both laboratories and the Quality Assurance (QA) department [20].

- Risk Assessment and Mitigation: Before transfer, conduct a risk assessment to identify potential issues like instrument model differences, reagent variability, or analyst skill gaps [19] [21]. Mitigation strategies may include standardizing materials, ensuring equipment equivalency, and conducting pilot testing [19].

- Effective Knowledge Sharing: The transferring lab must provide a comprehensive package including the validated method, development report, validation data, known issues, and troubleshooting tips [20]. Hands-on training for the receiving lab's analysts is crucial for building proficiency [21].

- Thorough Documentation and Reporting: All data, including any deviations, must be meticulously recorded. A final report summarizes the results, statistical analysis, and concludes on the success of the transfer, requiring QA approval before the method can be used routinely in the receiving lab [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The consistency and quality of reagents and standards are fundamental to the success of both robustness testing and method transfer. The following table details key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Transfer

| Item | Critical Function | Considerations for Transfer |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards [13] | Serves as the primary benchmark for quantifying the analyte and determining method accuracy. | Must be of certified purity and traceable to a recognized standard body. Use the same lot across TL and RL for transfer studies [20]. |

| Chromatography Columns [19] | The stationary phase responsible for the separation of analytes in HPLC/GC methods. | Column variability (lot-to-lot, different suppliers) is a major risk. Specify brand, dimensions, and particle chemistry. Pre-test columns from the same supplier [19] [1]. |

| HPLC/Spectroscopy Solvents [19] | Forms the mobile phase or solution matrix for analysis. | Use high-purity grades from the same supplier to minimize variability in UV cutoff, viscosity, and impurity profile [19]. |

| Buffer Salts & Additives [1] | Modifies mobile phase to control pH and ionic strength, impacting selectivity and peak shape. | Specify grade, supplier, and precise preparation methodology. Small variations in pH or concentration can significantly affect robustness [1]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Mixtures [20] | A prepared sample used to verify the entire chromatographic system's performance before analysis. | Critical for demonstrating method functionality in the RL. Typically contains key analytes and critical separation pairs [20]. |

Navigating Regulatory Guidelines

Adherence to regulatory guidelines is mandatory. Key documents governing method validation and transfer include [19]:

- ICH Q2(R2): "Validation of Analytical Procedures" provides the global standard for validation parameters [16] [14].

- USP General Chapter <1224>: "Transfer of Analytical Procedures" directly outlines transfer approaches [19].

- FDA & EMA Guidelines: Both agencies have issued guidance endorsing these principles and requiring evidence of method reliability across labs [19].

The recent simultaneous issuance of ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 ("Analytical Procedure Development") marks a shift towards a more scientific, lifecycle-based approach [23] [14]. This emphasizes proactive development of robust methods using tools like the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), which prospectively defines the method's required performance characteristics, inherently facilitating smoother method transfers [14].

Analytical method transfer is a critical, non-negotiable element of the pharmaceutical quality system. Its success hinges on a foundation of rigorous robustness testing during method development, the selection of an appropriate transfer strategy, and unwavering attention to detail in execution and documentation. By systematically employing best practices—thorough planning, clear communication, and the use of qualified reagents—organizations can ensure the consistent quality of medicines, maintain regulatory compliance, and safeguard patient safety across the global manufacturing and testing network.

In the development of organic analytical procedures, the robustness of a method is a critical determinant of its long-term reliability and regulatory acceptance. Robustness is formally defined as a measure of an analytical procedure's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [17]. This attribute is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical analysis, where method failures can lead to costly delays, regulatory non-compliance, and potential impacts on patient safety.

The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines emphasize robustness testing during method development, requiring demonstration that analytical methods can withstand typical operational variations encountered in different laboratories, by different analysts, and using different instruments [9]. Despite these requirements, non-robust methods continue to plague the industry, resulting in substantial scientific and economic consequences that merit thorough examination.

This article presents a comprehensive comparison between robust and non-robust analytical approaches through detailed case studies across multiple domains, with particular focus on pharmaceutical applications. We summarize quantitative performance data, provide detailed experimental protocols, and identify essential research reagents to support method development within a Quality by Design (QbD) framework.

Comparative Performance: Robust vs. Non-Robust Methods

Statistical Modeling Case Study

In longitudinal data analysis, the choice between robust and non-robust methods significantly impacts result reliability, particularly when data deviate from normality and contain missing values. Simulation studies comparing Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMM) with robust alternatives demonstrate critical performance differences.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Statistical Methods for Non-Normal Data with Missing Values

| Method | Key Assumptions | Bias in Fixed-Effect Estimates | Performance Under MAR Missing Data | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Mixed-Effects Models (LMM) | Normal distribution of errors and random effects | Significant bias under non-normality with missing data | Poor performance with skewed data | Highly sensitive to distributional assumptions and missing data mechanisms |

| Weighted Generalized Estimating Equations (WGEE) | Only marginal mean structure specification | Minimal bias under non-normality | Valid inference for skewed MAR data | Requires correct missing data model |

| Augmented WGEE (AWGEE) | Marginal mean and missing data model | Minimal bias (double robustness property) | Valid inference even with incorrect missing data model | Computational complexity |

Simulation studies reveal that while LMM provides reliable estimates under complete data conditions, its robustness is compromised with missing data when error terms deviate from normality. In these scenarios, LMM fixed-effect estimates demonstrate significant bias, whereas both WGEE and AWGEE maintain valid inference for skewed non-normal data when missing data follows the Missing At Random (MAR) mechanism [24].

Analytical Chemistry Case Study

In pharmaceutical analysis, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method robustness directly impacts method transfer success and routine application reliability. Experimental designs systematically evaluating parameter variations demonstrate measurable consequences of non-robust methods.

Table 2: HPLC Robustness Test Results for Active Compound and Related Substances

| Varied Parameter | Nominal Level | Variation Range | Impact on % Recovery (Active Compound) | Impact on Critical Resolution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase pH | 3.1 | ±0.1 units | -1.2% to +0.9% variation | Decrease by 0.3 at lower pH | Critical parameter requiring tight control |

| Column Temperature | 25°C | ±2°C | -0.7% to +0.5% variation | Minimal change (<0.1) | Non-critical within tested range |

| Flow Rate | 1.0 mL/min | ±0.1 mL/min | -1.5% to +1.8% variation | Decrease by 0.4 at higher flow | Critical parameter requiring specification |

| Organic Solvent % | 45% | ±2% | -2.1% to +1.7% variation | Decrease by 0.5 at lower organic | Critical parameter requiring specification |

Studies demonstrate that non-robust HPLC methods exhibit significant sensitivity to variations in critical parameters like mobile phase pH, flow rate, and organic solvent composition. These variations directly impact key performance indicators including percent recovery of active compounds and critical resolution between compounds [17]. The measurable consequences include out-of-specification results, system suitability test failures, and method transfer difficulties between laboratories.

Experimental Protocols for Robustness Assessment

Robustness Screening for Chemical Reactions

The assessment of robustness in chemical reactions employs a systematic protocol to identify limitations and failure points under varied conditions:

Parameter Selection: Identify critical reaction parameters including temperature, solvent composition, catalyst load, concentration, and reaction time based on preliminary risk assessment.

Experimental Design: Implement a Plackett-Burman design or fractional factorial design to efficiently evaluate multiple parameters with minimal experiments. For 8 factors, a 12-experiment Plackett-Burman design provides sufficient data for statistical analysis [17].

Level Selection: Define high and low levels for each parameter representing variations expected during normal method transfer and use. Levels typically represent "nominal level ± k * uncertainty" where k ranges from 2-10 based on parameter criticality [17].

Execution Protocol:

- Perform experiments in randomized sequence to minimize uncontrolled influences

- Include regular replicates at nominal conditions to monitor and correct for systematic drift

- For impractical randomization (e.g., column changes), block experiments by the challenging factor

Response Measurement: Quantify key performance indicators including yield, purity, reaction completion, and byproduct formation for each experimental condition.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate factor effects as Ex = (Ȳhigh - Ȳlow) for each parameter-response combination

- Apply statistical analysis (ANOVA) to identify significant effects

- Use graphical methods (normal probability plots) to distinguish significant from random effects [17]

Method Definition: Establish system suitability test limits and control strategies for critical parameters based on observed effects.

Robustness Evaluation for Analytical Methods

The protocol for assessing analytical method robustness follows a structured approach aligned with ICH guidelines:

Experimental Workflow for Analytical Method Robustness Assessment

Factor Selection and Level Definition:

- Select factors related to both procedural description and environmental conditions

- Define extreme levels as symmetric or asymmetric intervals around nominal conditions based on parameter behavior

- For quantitative factors (pH, temperature, flow rate), select levels representing expected operational variations

Design Selection:

- For screening purposes, employ fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs

- Select design resolution based on number of factors and resources

- Include dummy factors in unsaturated designs to estimate experimental error

Response Selection:

- Include both assay responses (content determinations, impurity quantifications) and system suitability test parameters (resolution, tailing factor, retention time)

- Define acceptance criteria for each response prior to experimentation

Experimental Execution:

- Prepare representative test solutions (blank, standard, sample)

- Execute experiments in defined sequence, with randomization where practical

- For time-sensitive factors, implement anti-drift sequences or include nominal condition replicates for drift correction

Effect Estimation and Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate factor effects using Ex = (ΣY+ - ΣY-)/N for each parameter

- Apply statistical significance testing using estimated experimental error

- Utilize graphical methods including normal probability plots and half-normal plots to identify significant effects

Conclusion and Control Strategy:

- Classify parameters as critical or non-critical based on statistical and practical significance

- Define system suitability test limits based on robustness study results

- Establish control strategies for critical parameters [17]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Robustness Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Robustness Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantification and system suitability verification | Use highly characterized materials with certified purity; essential for accuracy determination |

| Chromatographic Columns | Stationary phase for separation | Test multiple lots and/or manufacturers to assess column-to-column variability |

| Mobile Phase Components | Creation of elution environment | Vary pH, buffer concentration, and organic modifier percentage within realistic ranges |

| Sample Preparation Solvents | Extraction and dissolution medium | Evaluate impact of different grades, suppliers, and preparation methods |

| System Suitability Test Mixtures | Verification of method performance | Contain critical analyte pairs to assess resolution, efficiency, and sensitivity |

| Chemical Forcing Agents | Intentional stress conditions | Acids, bases, oxidants, and light sources for forced degradation studies |

Successful robustness testing requires careful selection and control of research reagents to ensure meaningful results. The method operable design region (MODR) is established based on demonstrated robustness across variations in these essential materials [9]. Implementation of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles enhances method robustness by systematically understanding and controlling relevant sources of variability, thereby reducing errors and out-of-specification results during routine use [9].

Consequences of Non-Robust Methods in Practice

Impact on Method Transfer and Reliability

Non-robust methods manifest significant operational consequences during technology transfer and routine application:

Method Transfer Failures: Methods that perform adequately in the development laboratory frequently fail during transfer to quality control laboratories due to unaccounted-for variations in equipment, reagents, and environmental conditions. These failures necessitate costly redevelopment and revalidation activities, delaying product development timelines.

System Suitability Test Failures: Non-robust methods exhibit heightened sensitivity to minor variations, resulting in frequent system suitability test failures during routine analysis. This necessitates extensive investigation, repeat testing, and potential batch rejection, impacting manufacturing efficiency and product release.

Inter-laboratory Variability: Without demonstrable robustness, methods produce significantly different results when performed by different analysts, using different instruments, or in different locations. This variability complicates result interpretation and decision-making based on analytical data.

Regulatory Challenges: Regulatory submissions require demonstration of method robustness. Non-robust methods face increased scrutiny during review and may receive deficiencies, delaying approval and requiring additional studies to address concerns.

Economic and Timeline Implications

The economic consequences of non-robust methods extend throughout the product lifecycle:

Investigation Costs: Each method failure or out-of-specification result triggers resource-intensive investigations requiring technical staff time, management oversight, and potentially manufacturing process review.

Timeline Impacts: Method redevelopment, additional validation, and regulatory responses can delay product launches by several months, resulting in significant opportunity costs and potential loss of market advantage.

Control Strategy Costs: Non-robust methods require tighter controls on reagents, equipment, and operating procedures, increasing routine testing costs and complexity.

The adoption of robust method development principles, including systematic robustness testing during development rather than after validation, significantly mitigates these consequences by identifying critical parameters early and establishing appropriate control strategies [17].

Non-robust analytical methods present substantial scientific and economic consequences throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle. Through systematic case studies, we have demonstrated that non-robust methods generate biased results, increase variability, and impair method transferability.

The implementation of structured robustness testing during method development, utilizing appropriate experimental designs and statistical analysis, enables identification of critical method parameters and establishment of effective control strategies. The adoption of Analytical Quality by Design principles provides a framework for developing inherently robust methods, reducing the occurrence of method failures and their associated consequences.

Robustness should not be an afterthought in analytical method development but rather an integral consideration throughout the method lifecycle. By prioritizing robustness during development, researchers can ensure reliable method performance, successful technology transfer, and maintained regulatory compliance, ultimately supporting the efficient development of quality pharmaceutical products.

Implementing Robustness Studies: Experimental Designs and Practical Applications

Robustness is defined as the capacity of an analytical procedure to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters and provides an indication of its reliability during normal usage [17]. This characteristic measures a method's resilience to minor operational fluctuations that inevitably occur during transfer between laboratories, analysts, or instruments. For researchers and drug development professionals, establishing method robustness is not merely a regulatory formality but a fundamental aspect of ensuring data integrity and reproducibility throughout the method lifecycle [25].

The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines recognize robustness as a critical validation parameter, while the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) has historically referred to a related concept as "ruggedness," defined as the degree of reproducibility of test results under a variety of normal conditions including different laboratories, analysts, instruments, and reagent lots [1]. Although terminology has evolved toward harmonization, with "intermediate precision" now often replacing "ruggedness" in regulatory contexts, the underlying principle remains essential: analytical methods must produce reliable results despite expected operational variations [1].

This guide examines the critical parameters that determine HPLC method robustness, providing a structured comparison of approaches for identifying, testing, and controlling these factors to ensure method reliability in pharmaceutical analysis and research settings.

Critical HPLC Method Parameters for Robustness Evaluation

Classification of Method Parameters

In robustness testing, method parameters are typically categorized as either internal (robustness) or external (ruggedness) factors [1]. Internal factors are those specified within the method documentation, such as mobile phase composition, pH, flow rate, and column temperature. External factors encompass elements not typically specified in methods, such as the analyst performing the test, the specific instrument used, or the day of analysis [1]. A practical rule of thumb distinguishes these: if a parameter is written into the method, it constitutes a robustness consideration; if it is not specified but may vary during normal use, it represents a ruggedness issue [1].

High-Impact HPLC Parameters

Mobile Phase Composition and pH are among the most critical parameters affecting separation robustness. The pH of the mobile phase profoundly impacts the ionization state of analytes, particularly when dealing with ionizable compounds, which constitute many pharmaceutical substances. For acidic analytes, maximum retention occurs in eluent systems at approximately two pH units lower than the functional group pKa, while basic analytes show maximum retention at two pH units higher than their pKa values [26]. Operating near analyte pKa values decreases robustness, as small changes in eluent pH cause significant retention time shifts. True buffer systems with adequate capacity provide more robust separation compared to single-component pH modifiers like trifluoroacetic acid [26].

Column Temperature significantly influences separation selectivity and efficiency. Temperature affects retention through its impact on thermodynamic partitioning and can alter selectivity for complex mixtures. Modern HPLC systems with advanced thermostatting capabilities allow precise temperature control, which is essential for robust methods [25]. During method development, temperature screening identifies optimal conditions that minimize sensitivity to minor fluctuations.

Flow Rate directly impacts retention times and backpressure. While retention time shows an inverse relationship with flow rate, peak shape and resolution may also be affected, particularly for complex separations. Robust methods maintain acceptable performance despite minor flow rate variations expected between different instruments [17].

Stationary Phase Characteristics including ligand chemistry, particle size, pore size, and manufacturer lot introduce important variables. Column chemistry differences, even between seemingly equivalent C18 columns from various manufacturers, can significantly alter selectivity [27]. Smaller particles (1.7-5µm for UPLC, 3-5µm for HPLC) increase efficiency but require higher operating pressures and may demonstrate different batch-to-batch variability [28].

Table 1: Critical HPLC Method Parameters and Their Impact on Separation

| Parameter Category | Specific Factors | Impact on Separation | Typical Variation Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | pH | Retention of ionizable compounds; selectivity | ±0.1-0.2 pH units |

| Buffer concentration | Peak shape; retention time | ±5-10% of nominal | |

| Organic modifier ratio | Retention; selectivity; pressure | ±1-2% absolute | |

| Column | Temperature | Retention; selectivity | ±2-5°C |

| Type/brand | Selectivity; efficiency | Different lots/manufacturers | |

| Age/history | Retention; peak shape | New vs. used columns | |

| System | Flow rate | Retention time; pressure | ±0.05-0.1 mL/min |

| Wavelength | Response factor; sensitivity | ±2-5 nm | |

| Gradient delay volume | Retention time (gradient methods) | Instrument-dependent |

Experimental Designs for Robustness Testing

Screening Design Approaches

Robustness testing systematically evaluates how method parameters affect analytical responses using structured experimental designs. Traditional univariate approaches (changing one factor at a time) have largely been replaced by more efficient multivariate designs that capture factor interactions [1]. Screening designs represent the most appropriate approach for robustness studies, with three primary types employed [1] [11]:

Full factorial designs investigate all possible combinations of factors at two levels (high and low). For k factors, this requires 2^k experiments. While comprehensive, these designs become impractical beyond 4-5 factors due to the exponentially increasing number of runs [1].

Fractional factorial designs carefully selected subsets of full factorial experiments that maintain the ability to estimate main effects while reducing experimental burden. These designs are particularly valuable when investigating 5 or more factors, as they can reduce the number of runs by half, quarter, or smaller fractions while still providing meaningful data [1].

Plackett-Burman designs highly efficient screening designs that require a multiple of four experiments to study up to N-1 factors. These designs are especially suitable for robustness testing where the primary interest lies in identifying significant main effects rather than detailed interaction effects [11] [17]. For example, a Plackett-Burman design with 12 experiments can efficiently evaluate the effects of 11 factors [1].

Implementing Robustness Studies

A systematic approach to robustness testing involves several defined stages [17]. First, critical factors and their appropriate test ranges are selected based on method knowledge and practical experience. The experimental levels should represent variations expected during method transfer between laboratories or instruments [17]. Quantitative factors typically employ symmetric intervals around the nominal level (e.g., nominal ± variation), though asymmetric intervals may be appropriate for parameters with nonlinear responses [17].

After executing the designed experiments, factor effects are calculated as the difference between average responses at high and low levels for each factor [17]. These effects are then evaluated statistically or graphically to distinguish significant impacts from random variation. Graphical approaches include normal or half-normal probability plots, while statistical methods may use t-tests or critical effects derived from dummy factors or the algorithm of Dong [17].

Diagram 1: Robustness Testing Workflow. This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to evaluating method robustness, from factor selection through method implementation.

Comparative Data: Experimental Designs for Robustness

The selection of an appropriate experimental design represents a critical decision in robustness testing, balancing comprehensiveness against practical constraints. Different designs offer distinct advantages depending on the number of factors under investigation and the specific objectives of the study [1] [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Designs for Robustness Testing

| Design Type | Number of Factors | Number of Experiments | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | 2-5 | 2^k | Estimates all main effects and interactions; no confounding | Number of experiments grows exponentially with factors |