Solvent Effects on Reaction Outcomes: A Comparative Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how solvents fundamentally influence chemical reaction outcomes, a critical consideration in pharmaceutical development and synthetic chemistry.

Solvent Effects on Reaction Outcomes: A Comparative Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how solvents fundamentally influence chemical reaction outcomes, a critical consideration in pharmaceutical development and synthetic chemistry. We explore the foundational principles governing solvent-solute interactions, from polarity to hydrogen bonding, and survey advanced computational methodologies like COSMO-RS and machine learning for predicting solvent effects. The content delivers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing solvent systems in complex processes, supported by comparative validation of experimental and theoretical approaches. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current knowledge and emerging trends to enable more efficient, predictive, and sustainable solvent selection.

The Unseen Driver: Foundational Principles of Solvent Effects in Chemical Systems

The traditional view of solvents as mere passive spectators in chemical processes has been fundamentally overturned. Contemporary research unequivocally demonstrates that solvents participate as active components that critically influence reaction pathways, selectivity, and efficiency across diverse chemical applications. The interplay between solute and solvent molecules extends beyond simple solvation to encompass complex interactions including van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and polarity effects that collectively dictate molecular behavior in solution. Understanding these interactions has become paramount for advancing fields ranging from asymmetric synthesis and pharmaceutical development to green chemistry and separation technology. This guide systematically compares the experimental and computational methodologies employed to quantify solvent-solute interactions, providing researchers with objective performance data and detailed protocols for investigating these fundamental relationships.

Comparative Methodologies for Studying Solvent-Solute Interactions

Computational Chemistry Approaches

Computational methods provide molecular-level insights into solvent-solute interactions that are often challenging to obtain experimentally.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Studying Solvent-Solute Interactions

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Applications | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT with Implicit Solvation | Continuum dielectric model approximating solvent effects | Initial screening of solvent effects on electronic properties | Underpredicts reduction potentials by ~66% for strongly hydrogen-bonding systems [1] | Fails to capture specific intermolecular interactions |

| DFT with Explicit Solvation | Inclusion of discrete solvent molecules in QM calculation | Systems with strong directional interactions (H-bonding, dispersion) | Accurate prediction of carbonate radical reduction potential (1.57V) with 9-18 explicit H₂O molecules [1] | Computationally expensive; sensitive to solvent configuration |

| Energy Decomposition Analysis | Partitioning of interaction energies into physical components | Quantifying dispersion contributions in asymmetric catalysis | Dispersion contributes up to 30% of total solvation energy; short-range repulsion often counteracts dispersion effects [2] | Requires advanced computational expertise |

| COSMO-RS | Quantum chemistry-based statistical thermodynamics | Solvation free energy and solubility prediction | Systematic deviations from experimental data for complex systems [3] [4] | Limited accuracy for multicomponent solvent systems |

Experimental Protocol: Calculating Reduction Potentials with Explicit Solvation [1]

- System Preparation: Generate molecular structures for both oxidized (carbonate radical anion) and reduced (carbonate dianion) species

- Explicit Solvation: Manually add explicit solvent molecules (9-18 water molecules for carbonate system) ensuring hydrogen-bonding interactions

- Geometry Optimization: Employ DFT functionals with dispersion corrections (ωB97xD or M06-2X) with 6-311++G(2d,2p) basis set

- Energy Calculation: Perform frequency calculations to confirm minima and obtain Gibbs free energies

- Reduction Potential Calculation: Apply equation ΔGᵣₓₙ = -nFE⁰ - ESHE where ESHE = 4.47 V

- Validation: Compare computed values with experimental benchmark (1.57 V for carbonate radical)

Experimental Measurement Techniques

Experimental approaches provide essential validation for computational models and direct measurement of solvent effects in real systems.

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Quantifying Solvent-Solute Interactions

| Method | Measured Property | Applications | Key Insights | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvent Nanofiltration (OSN) | Solute rejection and solvent flux through membranes | Solvent-solute-membrane interactions; separation efficiency | Solvent properties dominate flux; solute properties control retention in ceramic membranes [5] | Complex interplay of multiple factors difficult to deconvolute |

| Gravimetric Sorption | Solvent diffusivity in polymers | Membrane design for solvent separations | Enables calculation of permeability and permselectivity for membrane screening [6] | Time-intensive; limited to compatible polymer-solvent systems |

| Solubility Measurements | Saturation concentration | Pharmaceutical development, reaction optimization | Experimental error represents aleatoric uncertainty limit (0.5-1.0 log units) [4] | Resource-intensive; significant inter-laboratory variability |

| Reduction Potential Measurement | Electron affinity in solution | Electron transfer reactions, oxidation treatments | Provides benchmark for validating computational solvation models [1] | Requires careful control of experimental conditions |

Experimental Protocol: Organic Solvent Nanofiltration Studies [5]

- Membrane Selection: Utilize native TiO₂ (hydrophilic) and methyl-grafted TiO₂ (hydrophobic) ceramic membranes with 0.9 nm pore diameter

- Solvent System Preparation: Employ 12 organic solvents, water, and binary mixtures with varying polarities

- Solute Selection: Include 24 diverse solutes at different concentrations to assess retention behavior

- Filtration Experiments: Conduct dead-end filtration at room temperature with constant pressure

- Performance Measurement: Quantify volumetric flux (L·m⁻²·h⁻¹) and solute rejection (1 - Cₚₑᵣₘₑₐₜₑ/Cꜰₑₑd)

- Data Analysis: Calculate Spearman rank correlations between solvent/solute properties and membrane performance metrics

Machine Learning and Data-Driven Approaches

Machine learning methods leverage large datasets to predict solvent-mediated properties where traditional models face limitations.

Table 3: Machine Learning Approaches for Solvent-Solute Interaction Prediction

| Method | Architecture | Applications | Performance | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Molecular graph representation with node/edge features | Solubility prediction in multicomponent solvents [3] | MAE of 0.5-1.0 logS units approaching aleatoric limit [4] | Requires large datasets; limited extrapolation to novel chemistries |

| Transformer Models (SoDaDE) | Attention mechanisms trained on solvent property sequences | Solvent representation for reaction yield prediction [7] | Outperforms traditional molecular fingerprints on benchmark tasks [7] | Dependent on quality and diversity of pre-training data |

| Physics-Enforced Neural Networks | Incorporation of physical laws into network architecture | Solvent diffusivity through polymers [6] | Improved generalizability in data-limited scenarios [6] | Complex implementation; requires domain expertise |

| Semi-Supervised Distillation | Knowledge transfer from computational to experimental data | Solubility prediction with limited experimental data [3] | Corrects high-error margins in COSMO-RS predictions [3] | Dependent on accuracy of teacher model |

Experimental Protocol: Developing Solubility Prediction Models [3] [4]

- Data Curation: Compile experimental solubility datasets (MixSolDB, BigSolDB) with standardized formats

- Data Augmentation: Generate additional data points using COSMO-RS calculations for underrepresented chemical spaces

- Model Architecture Selection: Implement concatenation or subgraph GNN architectures for multicomponent systems

- Training Regimen: Employ semi-supervised distillation to combine experimental and computational data

- Validation: Rigorously test extrapolation to unseen solutes using train/validation/test splits with no solute overlap

- Performance Benchmarking: Compare against state-of-the-art models (e.g., Vermeire et al.) on standardized datasets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Studying Solvent-Solute Interactions

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramic Membranes | TiO₂, 0.9 nm pore size, native and methyl-grafted versions | Organic solvent nanofiltration studies | Provides stable platform for studying solvent-solute-membrane interactions without swelling [5] |

| DFT Software | Gaussian 16 with SMD solvation model | Computational solvation studies | Enables implicit and explicit solvation calculations with various functionals [1] |

| COSMO-RS Implementation | COSMOtherm with BVP86/TZVP/DGA1 level | Solvation free energy calculations | Provides quantum chemistry-based solubility predictions for data augmentation [3] |

| Polymer Membranes | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and recyclable alternatives | Solvent separation studies | Model system for studying diffusivity-selectivity tradeoffs in organic solvent separations [6] |

| Neural Network Potentials | OMol25-trained models (eSEN, UMA) | Charge-related property prediction | Predicts reduction potentials and electron affinities without explicit physics consideration [8] |

The systematic comparison of methodologies reveals that no single approach comprehensively captures the complexity of solvent-solute interactions. Computational chemistry provides molecular-level insights but requires experimental validation, particularly for systems with strong specific interactions. Experimental techniques yield direct measurements but often produce data with significant inherent variability. Machine learning approaches offer powerful predictive capabilities but face challenges in extrapolation and physical interpretability. The most robust understanding emerges from integrating multiple methodologies, where computational predictions guide experimental design, experimental data validates and refines models, and machine learning bridges gaps across chemical spaces. This integrated approach enables researchers to move beyond viewing solvents as inert media toward leveraging solvent-solute interactions as design parameters for controlling chemical outcomes across synthetic chemistry, separation science, and pharmaceutical development.

In the realm of chemical research and drug development, predicting and controlling reaction outcomes is a fundamental challenge. The efficacy of a reaction, particularly in solution, is not solely dictated by the reactants and catalysts but is profoundly influenced by the molecular environment created by the solvent. This guide frames the critical molecular interactions—polarity, polarizability, and hydrogen bonding—within the broader thesis of solvent effects on reaction outcomes. These non-covalent interactions govern a solvent's ability to dissolve reactants, stabilize transition states, and influence product distribution. For researchers and scientists, a comparative understanding of these interactions is not merely academic; it is a practical tool for rational solvent selection, a key determinant in the efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability of chemical processes, from carbon capture to pharmaceutical synthesis [9] [10].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Polarity

Polarity arises from an unequal distribution of electron density within a molecule, leading to the presence of partial positive (δ+) and partial negative (δ-) charges separated in space. This occurs when atoms with different electronegativities form a covalent bond; the more electronegative atom pulls the bonding electrons closer to itself [11] [12].

The degree of polarity is quantified by the dipole moment ((\mu)), a vector quantity whose magnitude depends on the magnitude of the partial charges and the distance between them. A molecule's overall polarity is the vector sum of the dipole moments of its individual bonds. Therefore, a molecule like tetrachloromethane (CCl₄) can have polar C-Cl bonds yet possess no net dipole moment due to its symmetrical tetrahedral geometry that causes the individual bond dipoles to cancel out [13].

The electronegativity difference ((\Delta)EN) between bonded atoms is a primary indicator of bond polarity. A (\Delta)EN ≥ 0.5 is generally considered to form a polar covalent bond, while a difference greater than approximately 1.7 indicates a primarily ionic character [11] [12].

Polarizability

Polarizability describes how easily the electron cloud of an atom or molecule can be distorted by an external electric field, leading to a temporary, instantaneous dipole moment. This is a distinct concept from permanent polarity [14] [12].

Polarizability increases with the size of the atom or molecule. Larger atoms have more electrons that are located further from the nucleus; these electrons are less tightly held and are more susceptible to displacement. For example, in the halogen series, the polarizability increases significantly from fluorine to iodine. Consequently, non-polar molecules like nitrogen (N₂) or iodine (I₂) can exhibit intermolecular attractions because their electron clouds can become temporarily uneven, creating fleeting dipoles that induce dipoles in neighboring molecules [14].

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a special type of strong dipole-dipole interaction that occurs when a hydrogen atom is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom—specifically nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), or fluorine (F). This bond polarizes the molecule so strongly that the hydrogen atom carries a significant partial positive charge, allowing it to interact strongly with a lone pair of electrons on another N, O, or F atom [14] [13].

It is crucial to distinguish this from a covalent bond; a hydrogen bond (often denoted with a dotted line: X-H···Y) is an intermolecular force between two molecules or different parts of a large molecule. With bond strengths typically ranging from 5 to 30 kJ/mol, hydrogen bonds are weaker than covalent bonds but significantly stronger than other dipole-dipole or dispersion forces. This interaction is responsible for the anomalously high boiling point of water and is a fundamental force in determining the structure and function of biological molecules like DNA and proteins [14] [13].

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Interactions

The physical properties of compounds, such as boiling point and solubility, are direct reflections of the strength of the intermolecular forces at play. These forces exist on a spectrum of strength, which directly correlates with their impact on a compound's behavior.

Table 1: Hierarchy and Characteristics of Key Intermolecular Forces

| Interaction Type | Relative Strength | Origin of Interaction | Key Structural Influence | Impact on Boiling Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Bonds | Strongest (∼600-1000 kJ/mol) | Electrostatic attraction between fully charged cations and anions. | Non-directional, forms extensive lattice structures. | Very High (e.g., NaCl, 801 °C) [14] |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Strong (∼5-30 kJ/mol) | H bonded to N, O, or F attracting to a lone pair on another N, O, or F. | Highly directional. | High (e.g., H₂O, 100 °C) [14] [13] |

| Dipole-Dipole | Moderate | Attraction between the partial charges of permanent molecular dipoles. | Directional, polar molecules align for maximum attraction. | Moderate (e.g., HCl) [14] [13] |

| London Dispersion | Weakest (∼0.5-5 kJ/mol) | Temporary, instantaneous dipoles from uneven electron distribution. | Present in all molecules, strength depends on surface area and polarizability. | Low for small molecules, increases with molecular size (e.g., I₂, 184 °C) [14] [12] |

The strength of these intermolecular forces has a direct and predictable effect on the physical properties of a substance. Stronger intermolecular attractions require more thermal energy to overcome for a substance to transition from liquid to gas, leading to a higher boiling point [14]. This principle allows researchers to make inferences about the types of interactions present based on physical data.

Table 2: Comparative Solvent Properties and Dominant Interactions

| Solvent | Chemical Type | Polarity | Hydrogen Bonding Capability | Dominant Intermolecular Forces | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Hexane | Alkane | Non-polar | No | London Dispersion Forces | Dissolving non-polar solutes like lipids and oils. |

| Toluene | Aromatic | Non-polar | No | London Dispersion Forces, π-π Interactions [10] | Aprotic apolar medium for oxidation reactions [10]. |

| Diethyl Ether | Ether | Polar Aprotic | Acceptor Only | Dipole-Dipole, Dispersion | Solvent for Grignard reactions; cannot donate H-bonds. |

| Dichloromethane | Halogenated | Polar Aprotic | No | Dipole-Dipole, Dispersion | Extraction solvent due to high density and polarity. |

| Acetonitrile | Nitrile | Polar Aprotic | No | Dipole-Dipole, Dispersion | Aprotic polar medium that can hinder reactions via H-bonding with reactants [10]. |

| Acetone | Ketone | Polar Aprotic | Acceptor Only | Dipole-Dipole, Dispersion | Versatile polar solvent for organic synthesis. |

| Ethanol | Alcohol | Polar Protic | Both Donor & Acceptor | Hydrogen Bonding, Dipole-Dipole | Solvent for dissolving polar and ionic compounds, sterilization. |

| Water | - | Polar Protic | Both Donor & Acceptor | Strong Hydrogen Bonding, Dipole-Dipole | Universal biological solvent; hydration of ions (Ion-Dipole Force) [13]. |

Experimental Data and Protocols

Case Study 1: Evaluating Solvent Efficiency for Carbon Capture

The search for efficient solvent systems for CO₂ capture is a critical area of research driven by the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The performance of amine-based solvents is governed by their interaction with CO₂ at a molecular level.

4.1.1 Experimental Protocol: Assessing CO₂ Absorption and Desorption

- Solvent Preparation: Prepare aqueous solutions of the target amines (e.g., MEA, MDEA, 1DMA2P, DEAB) at a standard concentration (e.g., 30% w/w) [9].

- Absorption Phase:

- Place a known volume of the amine solvent in a reaction cell equipped with a gas inlet and pressure/temperature sensors.

- Saturate the system with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to purge O₂.

- Introduce a stream of pure CO₂ or a CO₂/N₂ mixture at a controlled pressure (e.g., 1 atm) and temperature (e.g., 25-40°C).

- Monitor the pressure drop in the system or use a mass flow meter to measure the rate of CO₂ uptake over time. The reaction is typically allowed to proceed until equilibrium is reached.

- Data Analysis:

- CO₂ Loading Capacity: Calculate the moles of CO₂ absorbed per mole of amine at equilibrium.

- Absorption Rate: Determine the kinetic parameters from the uptake data.

- Desorption/Regeneration Phase:

- Heat the CO₂-rich solvent in a separate regeneration flask, typically to 90-120°C.

- Monitor the release of CO₂ gas, often by connecting the flask to a bubbler or gas meter.

- Measure the energy input required to strip the CO₂ and the residual CO₂ loading after regeneration to assess the solvent's regeneration efficiency [9].

4.1.2 Key Findings from Comparative Research Research shows that blending different classes of amines can synergize their advantages. For instance, a primary amine like Monoethanolamine (MEA) has fast absorption kinetics but requires a high energy penalty for regeneration. In contrast, tertiary amines like 1-Dimethylamino-2-propanol (1DMA2P) possess higher CO₂ loading capacity and a lower heat of absorption, albeit with slower kinetics [9]. The molecular interactions dictate the reaction pathway: primary and secondary amines form stable carbamates, while tertiary amines, which lack a free hydrogen, facilitate the direct formation of bicarbonate, a reaction that is more easily reversed during regeneration [9].

Table 3: Performance Data of Selected Amine Solvents for CO₂ Capture

| Amine Solvent | Amine Type | CO₂ Loading Capacity (mol CO₂/ mol amine) | Relative Absorption Rate | Relative Heat of Regeneration | Key Molecular Interaction with CO₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEA | Primary | ~0.5 [9] | High | High | Zwitterion formation, leading to stable carbamate [9] |

| 1DMA2P | Tertiary | >MEA [9] | Moderate | Low | Bicarbonate formation via base catalysis [9] |

| DEAB | Tertiary | >MEA [9] | Moderate | Low | Bicarbonate formation, low viscosity enhances mass transfer [9] |

| PZ (Piperazine) | Cyclic Secondary | - | Very High (rate constant 10x MEA [9]) | - | Acts as a promoter; fast carbamate formation [9] |

| AMP | Sterically Hindered Primary | High | Slower due to hindrance | Lower than MEA | Unstable carbamate, favors bicarbonate [9] |

Case Study 2: Solvent Effects in Olefin Oxidation Catalysis

The choice of solvent can dramatically influence both the kinetics and the selectivity of catalytic reactions, as demonstrated in the epoxidation of olefins.

4.2.1 Experimental Protocol: Catalytic Epoxidation of Olefins

- Reaction Setup: In a carousel reaction station, mix the olefin substrate (e.g., 1.6 mmol of styrene or cis-cyclooctene) with an internal standard (e.g., dibutyl ether, 1.6 mmol) and an oxidant (e.g., tert-butyl hydroperoxide, 200 mol %) [10].

- Solvent and Catalyst Addition: Add the selected solvent (e.g., toluene or acetonitrile, volume consistent across experiments) and the catalyst (e.g., MCM-bpy-Mo, 3 mol %).

- Reaction Execution: Heat the magnetically stirred mixture to a set temperature (e.g., 353 K) and maintain it for the reaction duration.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Sample the reaction mixture at regular intervals. Analyze substrate conversion and product yield using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [10].

4.2.2 Key Findings from Comparative Research A study comparing toluene (apolar aprotic) and acetonitrile (polar aprotic) revealed that the solvent's molecular interactions with the substrate and catalyst can override simple polarity considerations. While acetonitrile has a higher dielectric constant, it was found to hinder the reaction rate significantly more than toluene. Neutron diffraction studies supported a model where acetonitrile molecules form hydrogen bonds with the oxidant (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) or the substrate, effectively locking them in an unproductive state and reducing their availability for the catalytic cycle. In contrast, toluene, which cannot form such strong specific interactions, allows for greater substrate-catalyst interaction, leading to faster kinetics. Notably, at isoconversion, the product selectivity was unaffected, indicating that the solvent modulates the reaction pathway primarily through kinetic hindrance rather than by altering the fundamental mechanism [10].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Solvent Effect on Reaction Trajectory

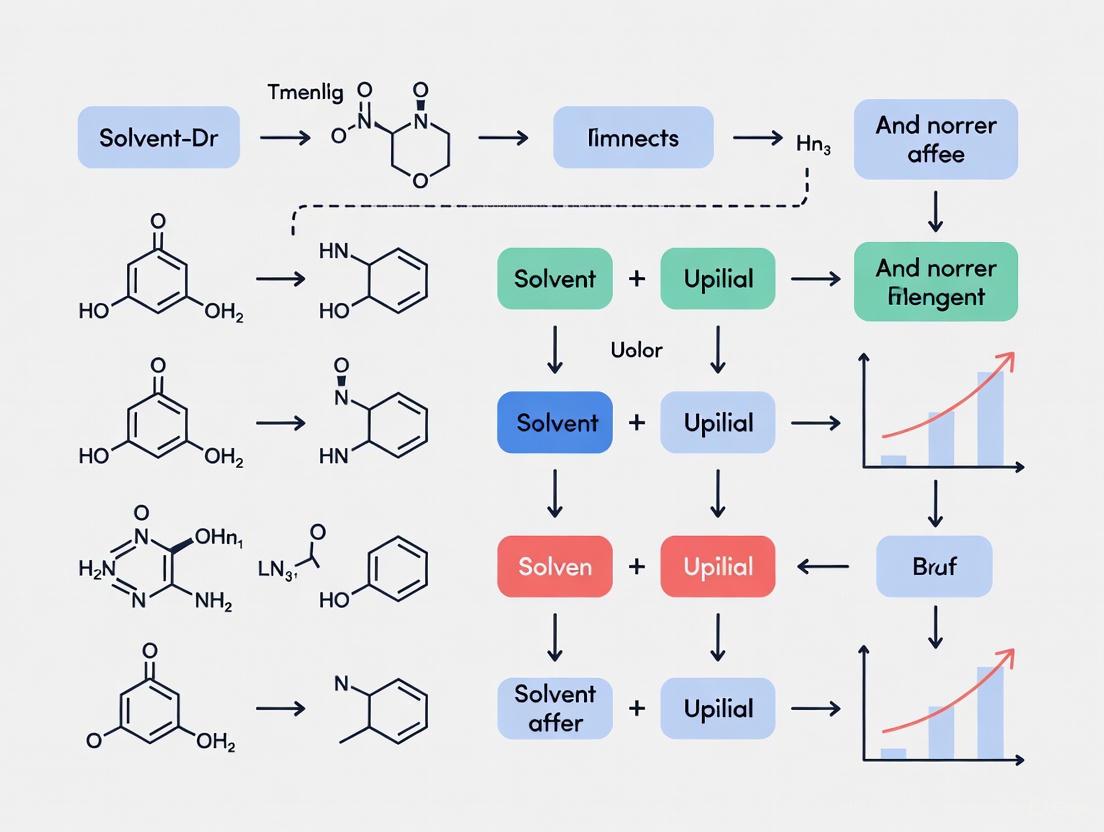

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of how different solvent interactions influence the energy landscape and outcome of a chemical reaction.

Diagram 1: A conceptual map of how key solvent interactions influence reaction outcomes.

Experimental Workflow for Solvent Evaluation

This diagram outlines a generalized experimental protocol for systematically evaluating solvent effects on a chemical reaction, applicable to the case studies cited.

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for the experimental evaluation of solvent effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions as derived from the experimental protocols discussed in this guide. This toolkit is essential for researchers investigating molecular interactions and solvent effects.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solvent Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Amines (e.g., MEA) | High-reactivity CO₂ solvents that form carbamates; serve as a benchmark for absorption rate. | Carbon capture efficiency studies [9]. |

| Tertiary Amines (e.g., 1DMA2P, DEAB) | High-capacity CO₂ solvents with lower regeneration energy; react via bicarbonate pathway. | Developing energy-efficient carbon capture blends [9]. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile) | Solvents with high dipole moment but no H-bond donating ability; can participate as H-bond acceptors. | Studying kinetic hindrance via H-bonding in oxidation catalysis [10]. |

| Apolar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Toluene) | Solvents with low polarity that primarily interact via dispersion forces. | Providing a low-interaction medium for high reaction rates in catalysis [10]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Dibutyl ether) | Inert compounds added in a known amount to reaction mixtures for quantitative chromatographic analysis. | Accurate measurement of substrate conversion and product yield in catalytic reactions [10]. |

| Chemical Oxidants (e.g., tert-Butyl hydroperoxide) | Source of oxygen atoms in catalytic oxidation reactions; its behavior is sensitive to solvent environment. | Model oxidant for studying solvent effects in epoxidation reactions [10]. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., MCM-bpy-Mo) | Solid catalysts with immobilized active sites; allow for studying solvent effects without catalyst solvation. | Probing substrate-solvent interactions at the solid-liquid interface [10]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Solvents used for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy; allow for mechanistic probing of reactions. | Identifying reaction intermediates and studying solvation shells. |

Solvent effects represent a critical, yet often overlooked, variable in pharmaceutical development that can dramatically alter the molecular properties, stability, and biological activity of drug compounds. Within the context of thienopyridine derivatives—a class of antiplatelet drugs including ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel—solvent interactions directly influence fundamental physicochemical parameters including pKa, lipophilicity, and metabolic activation pathways [15]. This case study examines how systematic manipulation of solvent environments alters the equilibrium behavior of thienopyridine derivatives, with implications for drug design, formulation stability, and bioavailability prediction. By comparing experimental and computational data across multiple solvent systems, this analysis provides a framework for understanding solvent-driven property modifications in heterocyclic pharmaceutical compounds.

Comparative Analysis of Solvent-Dependent Molecular Properties

Computational Predictions of Solvent Effects on Key Drug Properties

Advanced computational methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level, provide detailed insights into how solvents influence the molecular properties of thienopyridine-based antiplatelet drugs. These calculations employ the polarizable continuum model (PCM) to simulate aqueous and non-aqueous environments, revealing significant solvent-dependent trends in ionization behavior and molecular stability [15].

Table 1: Computed Physicochemical Properties of Antiplatelet Drugs in Aqueous Environment

| Compound | pKa | logP | Polar Surface Area (Ų) | Ionization State at pH 7.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ticlopidine | - | ~2.5-3.5 | 3-25 | Prodrug (requires metabolism) |

| Clopidogrel | - | ~2.5-3.5 | 3-25 | Prodrug (requires metabolism) |

| Prasugrel | - | ~2.5-3.5 | 3-25 | Prodrug (requires metabolism) |

| Ticlopidine Active Metabolite | Computed | - | - | Completely ionized |

| Clopidogrel Active Metabolite | Computed | - | - | Completely ionized |

| Prasugrel Active Metabolite | Computed | - | - | Completely ionized |

| Ticagrelor | Computed | - | - | Neutral undissociated |

| Cangrelor | Computed | - | 255 | Completely ionized |

The computational data reveals that solvent interactions significantly impact the ionization state of thienopyridine drugs at physiological pH. The active metabolites of prodrugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel) exist predominantly in ionized forms at pH 7.4, whereas ticagrelor and its active metabolite remain primarily in neutral, undissociated forms [15]. This fundamental difference in ionization behavior directly influences receptor binding interactions and bioavailability patterns.

Experimental Evidence of Solvent Effects on pKa and Stability

Experimental studies confirm that solvent composition significantly alters the acid-base equilibrium of thienopyridine derivatives. In organic solvent/water mixtures, the pKa values of thienopyridine compounds demonstrate marked dependence on both the concentration and chemical nature of the organic cosolvent [16].

Table 2: Experimental Solvent Effects on Thienopyridine Properties

| Solvent System | Observed Effect on Thienopyridine Derivatives | Impact on Drug Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol/Water | pKa values increase with organic cosolvent concentration | Altered ionization equilibrium |

| Ethanol/Water | pKa values increase with organic cosolvent concentration | Modified solubility profile |

| Acetone/Water | pKa values increase with organic cosolvent concentration | Shifted dissolution behavior |

| DMF/Water | pKa values increase with organic cosolvent concentration | Changed metabolic stability |

| Aqueous Oxidative Conditions | Forms multiple degradation products including N-oxides and endo-iminium species | Reduced pharmaceutical stability |

| Mechanochemical (Solvent-Free) | Selective oxidation without solution-based degradation pathways | Enhanced stability prediction |

The pKa values of thienopyridine derivatives ranging from 8.75 to 10.44 show consistent increases as the concentration of organic cosolvent (dimethylformamide, methanol, ethanol, or acetone) rises in water mixtures [16]. This phenomenon directly impacts drug purification processes, with methanol and ethanol frequently selected as recrystallization solvents for thienopyridine-based pharmaceuticals.

Forced degradation studies further highlight the profound influence of solvent environments on thienopyridine stability. Under traditional solution-based oxidative conditions, drugs like clopidogrel undergo complex degradation pathways producing multiple impurities including N-oxides and endo-iminium species [17]. In contrast, mechanochemical approaches without solvents yield more selective degradation profiles that better mimic actual solid dosage form stability, excluding irrelevant solution-based degradation pathways [17].

Molecular Structures and Solvent Interactions

Conformational Response to Solvent Environments

Quantum chemical calculations reveal that solvent interactions induce specific conformational changes in thienopyridine drugs that potentially influence their biological activity. For ticlopidine, the relative orientations of the phenyl and thienopyridine rings, defined by dihedral angles α[C(1)–C(2)–C(3)–N(4)] and β[C(2)–C(3)–N(4)–C(5)], shift significantly between gaseous, aqueous, and protein-bound states [15].

In the gas phase and aqueous solution, these moieties maintain a mutual gauche arrangement, whereas coordination with cytochrome P450 2B4 metabolizing enzyme induces a trans arrangement of the phenyl ring and thienopyridine moieties (dihedral angle β = 179.5°) [15]. The solvation energy—representing the energy difference between gas phase and solvated phase—is most pronounced for ionic species like cangrelor tetrasodium (-1316 kJ/mol), reflecting its considerable dipole moment and ionic character [15].

Solvent-Dependent Synthesis and Degradation Pathways

Solvent environments directly influence the synthetic pathways and degradation profiles of thienopyridine derivatives. In the synthesis of novel antimicrobial thienopyridine compounds, the lone electron pairs of hydroxy groups in methanol or ethanol solvents play essential roles in reaction mechanisms, leading to alkoxypyridine end products rather than the anticipated 4-H-cyanopyran compounds [18].

Similarly, oxidative degradation pathways diverge significantly based on solvent presence. Mechanochemical oxidative forced degradation of clopidogrel hydrogen sulfate with Oxone selectively produces the N-oxide CLP-DP-1 as the main degradant, while the same reaction performed with KNO₃ and KMnO₃ in solution yields the endo-iminium species CLP-DP-2 as the dominant product [17]. This solvent-controlled selectivity highlights how degradation mechanisms can be fundamentally altered by the presence or absence of solvent media.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Computational Chemistry Protocols

The investigation of solvent effects on thienopyridine derivatives employs sophisticated computational chemistry methods to predict molecular behavior across different environments:

Quantum Chemical Calculations: Density functional theory (DFT) methods at the Becke3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level are used to optimize molecular geometries and calculate energies of the most stable conformers of antiplatelet drugs [15]. This approach provides accurate determination of molecular structures for computer-aided drug design studies.

Solvent Modeling: The polarizable continuum method (PCM) is employed to account for solvent effects on equilibrium conformation. Specifically, the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) simulates aqueous environments and their influence on molecular geometry and stability [15].

Property Prediction: Computational approaches are used to evaluate key physicochemical parameters including pKa, lipophilicity (logP), solubility, absorption, and polar surface area. These calculations help rationalize observed differences in biological activity and bioavailability [15].

Solvation Energy Calculations: Energy differences between gas phase and solvated phases are computed to quantify solvent stabilization effects. These values are particularly large for ionic species like cangrelor tetrasodium (-1316 kJ/mol) due to their substantial dipole moments and ionic character [15].

Experimental Determination Methods

Experimental protocols for evaluating solvent effects encompass both traditional solution-based approaches and emerging solvent-free methodologies:

pKa Determination in Mixed Solvents: Experimental pKa values in organic solvent/water mixtures are determined using potentiometric or spectrophotometric methods. Studies systematically vary both the concentration and type of organic cosolvent (DMF, methanol, ethanol, acetone) to quantify their effects on ionization equilibrium [16].

Mechanochemical Forced Degradation: Ball milling procedures are employed to model solid-state degradation without solvent interference. Typical protocols involve milling drug substances with oxidants like Oxone in a mixer mill at 30 Hz frequency for durations up to 15 minutes, followed by LC-MS, NMR, and ATR-IR analysis of degradation products [17].

Drug-Excipient Compatibility Studies: Systematic evaluation of excipient effects on API stability involves milling drug compounds with individual excipients in the presence of oxidants, using inert SiO₂ as a grinding auxiliary to ensure proper mixing. Resulting degradation profiles are compared to identify excipient-specific interactions [17].

Chromatographic Analysis: Chiral HPLC methods are employed to monitor racemization processes and enantiomeric purity. For levetiracetam racemization studies, analyses are performed on an Ultimate 3000 system with UV detection at appropriate wavelengths [19].

Diagram Title: Solvent Effects on Thienopyridine Molecular Properties and Pharmaceutical Outcomes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Solvent Effects in Thienopyridine Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Polar aprotic cosolvent for pKa studies | Investigating pKa shifts in water/organic solvent mixtures [16] |

| Methanol & Ethanol | Protic polar solvents for recrystallization | Purification of thienopyridine derivatives; pKa modification studies [16] |

| Oxone (Potassium peroxymonosulfate) | Oxidant for forced degradation studies | Mechanochemical oxidative degradation of clopidogrel to model stability [17] |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) | Grinding auxiliary in mechanochemistry | Ensuring proper mixing and reaction efficiency in ball milling experiments [17] |

| Zirconium Dioxide (ZrO₂) | Milling material for mechanochemical studies | Providing mechanical energy input in solvent-free racemization and degradation reactions [17] [19] |

| Sodium Methoxide | Base catalyst for racemization studies | Promoting enantiomer interconversion in solution-based racemization processes [19] |

| Chiral HPLC Columns | Analytical separation of enantiomers | Monitoring racemization processes and determining enantiomeric purity [19] |

This case study demonstrates that solvent environments exert profound influences on the fundamental properties and behaviors of thienopyridine derivatives. Through both computational predictions and experimental validations, we have documented how solvent composition alters pKa values, molecular conformation, degradation pathways, and ultimately, pharmaceutical performance. The emergence of mechanochemical approaches as solvent-free alternatives provides valuable insights into intrinsic solid-state properties while eliminating solvent-mediated artifacts. For researchers developing thienopyridine-based pharmaceuticals, careful consideration of solvent effects during preformulation studies, stability testing, and bioavailability assessment is essential for accurate prediction of in vivo performance and shelf-life stability. The methodologies and data presented herein offer a framework for rational solvent selection in pharmaceutical development and quality control processes for this important class of therapeutic agents.

The selection and engineering of solvents are fundamental to controlling physical processes in chemical separation and purification. This guide examines two distinct paradigms: traditional solvent recrystallization and an emerging bypass purification method that utilizes a filtration membrane, thus avoiding energy-intensive thermal processes. Within the broader context of solvent effects on reaction outcomes, this comparison provides a quantitative framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select optimal purification strategies. The performance of these techniques is evaluated based on critical parameters including purity, yield, energy consumption, and operational scalability, with supporting experimental data structured for direct comparison.

Comparative Analysis: Recrystallization vs. Bypass Purification

The following table provides a high-level objective comparison of the two purification methods, summarizing their core principles, performance, and ideal application contexts.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Performance Comparison

| Feature | Solvent Recrystallization | Bypass Membrane Purification |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Differential solubility based on temperature changes. [20] | Molecular size and shape exclusion via filtration. [21] |

| Key Performance Driver | Solvent polarity, cooling rate, crystallization temperature. [20] | Membrane pore structure and swelling resistance. [21] |

| Maximum Purity/Selectivity | High (Purity raised from ~64% to over 91% in multiple cycles). [20] | High (Achieved 20x concentration of toluene over TIPB). [21] |

| Energy Consumption | Moderate (Requires heating for dissolution and cooling for crystallization). [20] | Low (Potentially reduces energy use by ~90% vs. thermal distillation). [21] |

| Optimal Application Scope | Purification of solid products (e.g., phytosterols, APIs, fine chemicals). [20] | Fractionation of liquid mixtures (e.g., crude oil, hydrocarbon feedstocks). [21] |

| Scalability & Industrial Maturity | Well-established and widely adopted. [20] | Emerging technology with promising scale-up potential. [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Solvent Recrystallization of Crude Phytosterols

This section details the methodology and results from a systematic investigation into the recrystallization of corn-derived phytosterols, a process relevant to pharmaceutical and functional food industries. [20]

Experimental Protocol: [20]

- Materials: Crude phytosterols (63.58% initial purity), solvents (95% ethanol, isopropyl alcohol, n-amyl alcohol, cyclohexanone, ethyl acetate, n-hexane).

- Procedure: A defined mass of crude phytosterols was dissolved in a selected solvent with heating to form a saturated solution. The solution was then cooled under controlled conditions: specific cooling rate, stirring speed, and a predetermined crystallization termination temperature. The resulting crystals were collected via filtration, and the process was repeated for multiple cycles.

- Analysis: The total phytosterol content (purity) and yield were quantified after each crystallization cycle to assess purification efficiency.

Table 2: Performance of Different Solvents in Phytosterol Recrystallination

| Solvent | Initial Purity (%) | Purity After 1st Cycle (%) | Purity After 2nd Cycle (%) | Optimal Crystallization Termination Temp. (°C) | Key Solvent Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Ethanol | 63.58 | 84.21 | 91.05 | 15 | Polar, hydrogen-bonding |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | 63.58 | 83.15 | 90.12 | 15 | Polar, hydrogen-bonding |

| n-Amyl Alcohol | 63.58 | 79.65 | 85.24 | 25 | Moderate polarity |

| Cyclohexanone | 63.58 | 77.58 | 83.11 | 25 | Polar aprotic |

| Ethyl Acetate | 63.58 | 75.42 | 80.35 | 20 | Moderate polarity |

| n-Hexane | 63.58 | 70.25 | 75.68 | 20 | Non-polar |

Key Parameter Optimization: [20]

- Crystallization Termination Temperature: Lower temperatures (e.g., 15°C) generally increased final purity but slightly reduced yield. A temperature of 15°C was identified as optimal for alcohols like ethanol.

- Cooling Rate: A slower cooling rate of 0.5°C/min favored the formation of larger, purer crystals compared to faster rates.

- Stirring Speed: A moderate stirring speed of 200 rpm was optimal, balancing crystal growth and mass transfer without promoting excessive nucleation.

- Recrystallization Cycles: A second recrystallization cycle was highly effective, boosting purity from ~84% to over 91% with 95% ethanol.

Bypass Purification via Polyimine Membrane Filtration

This section outlines the experimental approach for the emerging bypass purification technology, which separates molecules based on size exclusion without phase change. [21]

Experimental Protocol: [21]

- Materials: Hydrophobic monomer (TMC), hydrophilic monomer (MPD), catalyst, shape-persistent triptycene monomer, hexane, water.

- Membrane Synthesis (Interfacial Polymerization): A polyimine thin-film composite membrane was synthesized at the interface of hexane and water. The hydrophobic monomers dissolved in hexane react with hydrophilic monomers dissolved in water, forming a rigid, cross-linked, and non-swelling polyimine film with precise pore sizes, aided by the triptycene monomer.

- Filtration Procedure: The synthesized membrane was used in a filtration setup. A feed mixture (e.g., toluene/TIPB or industrial naphtha/kerosene/diesel) was passed through the membrane under pressure.

- Analysis: The permeate was analyzed to determine the concentration of separated components and the membrane's selectivity.

Key Performance Findings: [21]

- Separation Efficiency: The membrane achieved a 20-fold increase in the concentration of toluene relative to triisopropylbenzene (TIPB) in a model mixture, demonstrating high selectivity for smaller molecules.

- Industrial Relevance: When tested with a real industrial mixture of naphtha, kerosene, and diesel, the membrane efficiently separated lighter and heavier compounds by molecular size.

- Energy Savings: This membrane-based process is estimated to reduce the energy consumption of hydrocarbon separation by approximately 90% compared to conventional thermal distillation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Featured Purification Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Polar Protic Solvents (e.g., 95% Ethanol, Isopropanol) | Recrystallization of polar compounds via hydrogen bonding; high purity increase per cycle. [20] | Optimal for purifying phytosterols, achieving >90% purity. [20] |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Cyclohexanone, Ethyl Acetate) | Recrystallization of compounds with moderate polarity; offers different solubility profiles. [20] | Used in phytosterol purification with good results. [20] |

| Non-Polar Solvents (e.g., n-Hexane) | Recrystallization of non-polar molecules; least effective for the polar phytosterols in the study. [20] | Resulted in the lowest final purity for phytosterols. [20] |

| Polyimine Membrane | Core material for size-selective, bypass purification of organic liquid mixtures. [21] | Enabled energy-efficient fractionation of hydrocarbon fuels. [21] |

| Triptycene Monomer | A shape-persistent additive used during membrane synthesis to create and control pore size and selectivity. [21] | Critical for achieving molecular-level separation in polyimine membranes. [21] |

| CO2 Gas (≥99.9%) | Used as a processing aid in recrystallization to stabilize compounds prone to thermal decomposition. [22] | Suppressed NaHCO3 decomposition during dissolution, improving crystal quality and yield. [22] |

The data presented in this guide objectively demonstrates the distinct applications and advantages of solvent recrystallization and bypass membrane purification. Solvent recrystallization remains a powerful and versatile method for purifying solid compounds, with its efficiency highly dependent on a meticulously optimized solvent system and crystallization parameters. In contrast, bypass purification with advanced polyimine membranes represents a paradigm shift for separating liquid mixtures, offering dramatic energy savings by replacing thermal processes with molecular filtration. The choice between these methods is fundamentally dictated by the physical state of the mixture and the primary separation objective—solubility or molecular size.

In modern chemical research, the role of the solvent is often relegated to that of a passive medium, a mere spectator in the intricate dance of chemical reactions. This perspective overlooks a fundamental truth: solvents are active participants that can dramatically alter the course, efficiency, and outcome of chemical processes. The overarching thesis of this comparative research is that a nuanced understanding of solvent effects is not a specialized concern but a critical paradigm that cuts across all domains of modern chemistry, from synthetic organic chemistry to materials science and pharmaceutical development. Solvent interactions can govern reaction pathways, modify transition states, influence aggregation behavior, and ultimately determine the success or failure of an experimental protocol. This guide objectively compares the performance of different solvent environments through the lens of cutting-edge research, providing experimental data that underscores why the deliberate selection and understanding of solvents is indispensable for scientists and drug development professionals aiming to achieve predictable and optimized outcomes.

Theoretical Foundations of Solvent-Solute Interactions

The interaction between a solvent and a solute is a complex interplay of multiple forces, including polarity, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and solvophobic effects. These interactions are of similar strength to the non-covalent bonds that hold supramolecular polymers together, meaning that the solvent can directly compete with and influence the intended molecular associations [23]. In catalytic systems, particularly at liquid-solid interfaces, the solvent's role is multifaceted. It can interact with the reaction transition state to lower its free energy, modify the solubility and diffusivity of reactants, compete with reactants for adsorption sites on catalyst surfaces, or even participate as an active species, creating new reaction pathways with lower energy barriers [24].

A critical concept in materials chemistry is the phenomenon of aggregation-induced emission (AIE), where a fluorophore that is non-emissive in solution exhibits strong emission in its aggregated state. This switch is often governed by the solvent environment, which controls the molecular aggregation and the restriction of intramolecular motion [25] [26]. Furthermore, the solvent can induce dramatic emission color changes through solvatofluorochromism, a property where the fluorescence color of a compound shifts due to differences in the polarity of the solvent medium [26]. Understanding these foundational principles is the first step in harnessing solvent effects for practical applications.

Diagram 1: The foundational mechanisms through which a solvent influences chemical reactions and material properties. Key interactions like polarity and hydrogen bonding directly impact outcomes from reaction rates to material luminescence.

Comparative Experimental Data: A Tale of Different Solvents

Case Study 1: Solvent-Driven Luminescence in AIE Systems

Recent research on salicylic acid-derived fluorophores, DMAC-HBA and TPA-HBA, provides a compelling case study of dramatic solvent effects. These compounds exhibit unique water-caused quenching (WCQ) and AIE behaviors in tetrahydrofuran (THF)/water mixtures [25]. The following table summarizes the quantifiable photophysical changes for TPA-HBA as a function of water fraction in THF, a common organic solvent.

Table 1: Solvent-Dependent Emission Properties of TPA-HBA in THF/Water Mixtures [25]

| Water Fraction (vol%) | Emission Maximum (nm) | Relative Emission Intensity | Observed Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 475 nm | High | Efficient solution emission |

| 10% | 470 nm (blue-shift) | Dramatically quenched | Water-Caused Quenching (WCQ) |

| >10% (High) | Gradual red-shift | Gradually enhanced | Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) |

Experimental Protocol: The experiment was conducted by preparing dilute THF solutions of the synthesized TPA-HBA fluorophore. Precise volumes of water were gradually added to these solutions, and after thorough mixing, the photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded for each water fraction (f_w). The emission maximum (wavelength of peak intensity) and the relative intensity at that maximum were tracked. The synthesis of TPA-HBA itself involved a Suzuki coupling reaction between 4-bromo-2-hydroxybenzoic acid and 4-(diphenylamino)phenylboronic acid, followed by purification via silica gel column chromatography [25].

Comparative Analysis: The data demonstrates a non-linear, highly dependent relationship on solvent composition. The initial quenching and blue-shift are attributed to water molecules forming intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the salicylic acid unit, disrupting the intramolecular hydrogen bond and increasing the energy gap between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals. At higher water fractions, the AIE mechanism dominates. The formation of nanoaggregates restricts intramolecular rotation, leading to enhanced emission and a spectral red-shift [25]. This direct comparison shows that the same molecule can be tuned from being a quenched emitter to a bright luminogen solely by altering the solvent environment.

Case Study 2: Solvent Effects in Catalytic Reactions

In liquid-phase catalysis, the solvent's influence is quantifiable through reaction kinetics and adsorption thermodynamics. The presence of a solvent can significantly alter the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) of adsorption for reactants, which in turn dictates the overall reaction rate and selectivity [24].

Table 2: Impact of Solvent on Thermodynamic Parameters and Reaction Outcomes in Catalysis [24]

| Solvent Role | Mechanistic Influence | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Transition State Stabilizer | Lowers the apparent free energy barrier (ΔG‡) for the reaction. | Increased observed reaction rate under kinetic control. |

| Competitive Adsorber | Competes with reactants for active sites on the catalyst surface. | Decreased reaction rate; described by modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics (e.g., r = kKA CA / (1 + KA CA + KSol CSol)). |

| Participant in Reaction | Acts as a proton donor/acceptor or enables proton transfer via hydrogen bonding. | Creates new, lower-energy reaction pathways; can change product selectivity. |

| Structure Director | Modifies the structure and dynamics of water/solvent at the solid-liquid interface. | Alters the excess entropy and enthalpy of activation, affecting rates. |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating these effects typically involves a combination of experimental kinetics and computational modeling. For example, to study competitive adsorption, the reaction rate is measured for a series of solutions with constant reactant concentration but varying solvent identity. The data is then fitted to a kinetic model, such as the modified Langmuir-Hinshelwood equation, to extract the adsorption equilibrium constant for the solvent (K_Sol). Advanced techniques like vibrational spectroscopy and computational simulations are used to probe the structure of solvents at the solid-liquid interface [24].

Comparative Analysis: The choice between a polar protic solvent like water and a polar aprotic solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) can lead to order-of-magnitude differences in catalytic efficiency. For instance, in a reaction where the transition state is highly polar, a polar solvent will stabilize it, accelerating the reaction. Conversely, if that same solvent strongly adsorbs to the catalyst's active sites, it can block the reactant and slow the reaction down. The optimal solvent is thus not merely the one that dissolves the reactants, but the one that best balances these competing effects [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental studies highlighted above rely on a core set of reagents and materials designed to probe and exploit solvent interactions. The following toolkit details key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Solvent Effects

| Reagent / Material | Function & Chemical Role | Exemplar Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| AIE Luminogens (e.g., TPA-HBA, DMAC-HBA) | Bifunctional emitter and catalyst; exhibits aggregation-induced emission and solvatofluorochromism. | Visualizing solvent-dependent aggregation and high-contrast imaging [25] [26]. |

| Binary Solvent Systems (e.g., THF/Water) | Creates a tunable environment to study solvophobic effects and controlled aggregation. | Triggering the AIE effect and investigating water-caused quenching phenomena [25]. |

| Solid Base Supports (e.g., Sodium Carbonate) | Provides a surface for confining chemical reactions and controlling reaction locality. | Used in high-contrast visualization and information encryption via chemiluminescence [25]. |

| Lewis Basic Catalysts | Accelerates chemical reactions, such as the decomposition of peroxyoxalate in chemiluminescence systems. | Enhancing reaction speed and brightness in peroxyoxalate chemiluminescence (PO-CL) systems [25]. |

| Carbazole-Malononitrile Derivatives (e.g., CABM) | Acts as a mechanofluorochromic and solvatofluorochromic switch with a D-π-A structure. | Sensing anions (HSO3-), detecting water impurities, and bioimaging [26]. |

The comparative data presented herein unequivocally demonstrates that the solvent is a powerful, versatile, and often decisive variable in chemical research. The paradigm is clear: moving from a trial-and-error approach to a rational, mechanistic understanding of solvent effects is critical for advancing scientific discovery and technological innovation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this means integrating solvent selection as a primary design parameter, alongside catalyst and reactant choice. The experimental protocols and reagents outlined provide a roadmap for systematically exploring this parameter space. By embracing the "overlooked paradigm" of solvent effects, the scientific community can unlock new reaction pathways, optimize material properties, and achieve a higher degree of control in the complex landscape of chemical synthesis.

From Theory to Practice: Computational and Experimental Methods for Analyzing Solvent Effects

The outcomes of chemical reactions, especially in fields like pharmaceutical development, are profoundly influenced by their solvent environment. Solvents can alter reaction rates by several orders of magnitude, change the relative stability of intermediates, and even steer reactions toward entirely different mechanistic pathways [27]. These solvent effects are broadly categorized into general effects, arising from the solvent's bulk dielectric properties which stabilize charges, and specific effects, resulting from direct, short-range interactions like hydrogen bonding [27]. To accurately predict and model these influences in computational chemistry, researchers rely on continuum solvation models. These methods represent the solvent as a structureless continuum with a specific dielectric constant, within which a cavity containing the solute is embedded. This guide provides an objective comparison of four prominent continuum solvation models—PCM, CPCM, SMD, and Onsager—framed within the broader context of understanding solvent effects on reaction outcomes.

Theoretical Foundations of Continuum Models

At the core of all continuum solvation models is the central concept of a solvent reaction field. When a solute is placed in a solvent, the solute's charge distribution polarizes the solvent. This polarized solvent, in turn, generates an electric field that acts back upon the solute, modifying its electronic structure in a process that must be solved self-consistently [28] [29]. The fundamental goal of these models is to compute the Gibbs free energy of solvation (ΔG_solv), which quantifies the stability of a molecule in solution relative to the gas phase.

The key differentiator between models lies in how they define the solute cavity and compute the interaction with the solvent reaction field. Modern models typically construct the cavity as a union of overlapping spheres centered on the solute atoms [28]. The accuracy of a model depends on its treatment of this cavity and the mathematical formalism used to compute the electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions to the solvation energy.

Model Methodologies and Comparative Formulations

Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM)

The Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM), particularly its Integral Equation Formalism (IEFPCM) variant, is one of the most widely used and versatile models. It creates a solute cavity via a set of overlapping spheres and uses an integral equation formalism to compute the solvent reaction field [28]. The model discretizes the cavity surface into small elements, each carrying an apparent surface charge that is determined self-consistently with the solute's electrostatic potential [29]. The electrostatic problem is described by the linear equation Kq = Rv, where q is the vector of surface charges, v is the electrostatic potential at the surface, and K and R are matrices specific to the PCM flavor [29]. IEFPCM provides an exact treatment of surface polarization and an approximate treatment of volume polarization [29]. It is suitable for a wide range of applications, including geometry optimizations and excited state calculations in solution [28].

Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM)

The Conductor-like PCM (CPCM), also known as the Conductor-like Screening Model (COSMO), is a simplification that treats the solvent as a perfect conductor (with infinite dielectric constant) during the calculation of the surface charges. The results are then scaled back to the actual solvent dielectric constant using a factor, f(ε) = (ε-1)/ε [29]. This approach is computationally efficient and becomes highly accurate for solvents with high dielectric constants (ε > 50) [29]. For lower dielectric solvents, the scaling factor f(ε) = (ε-1)/(ε+1/2) is sometimes used, as in the original COSMO implementation [29]. CPCM is often the model of choice for high-dielectric solvents due to its computational efficiency and minimal loss of accuracy compared to more sophisticated models like IEFPCM [29].

Solvation Model based on Density (SMD)

The SMD model is a specific parameterization of the IEFPCM formalism developed by Truhlar and coworkers [28]. It is explicitly recommended for computing solvation free energies (ΔG) [28]. SMD goes beyond a simple dielectric continuum by incorporating a more detailed treatment of non-electrostatic interactions. The model uses state-specific atomic radii and a sophisticated parameterization of cavitation, dispersion, and solvent-structure terms based on the solvent's accessible surface area [28]. This makes it particularly accurate for predicting solvation free energies across a wide range of solvents and solute types. A key application is computing ΔG of solvation by performing separate gas phase and solution-phase calculations and taking the energy difference [28].

Onsager Model

The Onsager model is one of the earliest and simplest continuum models. It places the solute in a spherical cavity within the solvent reaction field [28]. The model is based on a dipole-field interaction, where the solute is characterized by its dipole moment and the cavity by a single radius [28]. While computationally very efficient, its major limitation is the oversimplified spherical cavity, which makes it inappropriate for molecules that are very non-spherical [29]. Input for the model typically consists of the solute radius in Angstroms and the solvent's dielectric constant [28].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Characteristics of Continuum Solvation Models

| Model | Cavity Construction | Dielectric Formalism | Key Electrostatic Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCM (IEFPCM) | Union of overlapping atom-centered spheres | Integral Equation Formalism (IEF) | Kq = Rv (IEFPCM/SS(V)PE matrices) [29] |

| CPCM (COSMO) | Union of overlapping atom-centered spheres | Conductor-like Screening, scaled by f(ε) | S q = -f(ε) v [29] |

| SMD | Union of overlapping spheres with specific atomic radii | IEFPCM with detailed non-electrostatic terms | IEFPCM electrostatics + parameterized non-electrostatic terms [28] |

| Onsager | Single sphere | Dipole reaction field in a spherical cavity | Dipole-based, depends on cavity radius and μ² [28] |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Theoretical formulations must be validated against experimental data. Benchmarking studies reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model for predicting key physicochemical properties.

Performance in Predicting Solvation Free Energies and Reduction Potentials

The SMD model is explicitly recommended for computing solvation free energies (ΔG_solv) due to its parameterization that accurately captures electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions [28]. Its performance is a key reason for its widespread use in computational chemistry and drug discovery.

For predicting reduction potentials, a critical property in electrochemistry and redox biology, the choice of solvation model significantly impacts accuracy. Studies benchmarking reduction potentials for main-group and organometallic species provide quantitative performance data. The table below summarizes the mean absolute error (MAE) for various computational methods, which typically couple a quantum mechanical method with an implicit solvation model like CPCM [8].

Table 2: Benchmarking Accuracy for Reduction Potential Predictions (Mean Absolute Error, V) [8]

| Computational Method | Main-Group Species (OROP, 192 compounds) | Organometallic Species (OMROP, 120 compounds) |

|---|---|---|

| B97-3c (with implicit solvation) | 0.260 | 0.414 |

| GFN2-xTB (with implicit solvation) | 0.303 | 0.733 |

| UMA-S Neural Network Potential (with CPCM-X) | 0.261 | 0.262 |

The data shows that the accuracy of a method can vary significantly between different chemical classes. For instance, while B97-3c is reasonably accurate for main-group species, its error increases for organometallics. Notably, the UMA-S neural network potential, when combined with the Extended Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM-X), showed consistent and high accuracy across both chemical classes, highlighting the effectiveness of the CPCM approach in this context [8].

Limitations in Specific Solvation Effects

While continuum models excel at capturing bulk electrostatic effects, they can struggle with specific solvation effects, such as direct hydrogen bonding. A 2025 study comparing the continuum model COSMO with the statistical-mechanical embedded cluster reference interaction site model (EC-RISM) found that COSMO significantly underestimated the effects of hydrogen bond donation on the excitation energies of phenolate anions in aqueous solution [30]. In contrast, EC-RISM, which models solvent distributions on an atomic level, provided a more faithful description [30]. This highlights a general limitation of continuum models: they may fail to capture strong, specific, and directional solute-solvent interactions that require an explicit, atomistic treatment of the solvent.

A Practical Guide for Model Selection

Choosing the right model depends on the scientific question, the system of interest, and computational resources.

- For General Solvation Free Energies (ΔG_solv): The SMD model is the recommended choice, as it is explicitly parameterized for this task and incorporates a comprehensive description of non-electrostatic terms [28].

- For Geometry Optimizations and Spectroscopic Calculations in High-ε Solvents: CPCM offers an excellent balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for solvents like water or DMSO [29].

- For Systems Requiring High Electrostatic Fidelity (e.g., Anions, Polar Excited States): The more rigorous IEFPCM formulation may be preferred, especially in lower dielectric environments or when asymmetric matrix formulations are needed [28] [29].

- For Rapid, Qualitative Estimates on Small, Roughly Spherical Molecules: The Onsager model can provide a first approximation, but its use is limited for quantitative work on complex molecules [28].

- For Processes Involving Strong, Specific Hydrogen Bonding: Consider hybrid approaches that combine a continuum model with a few explicit solvent molecules to capture the critical specific interactions, as pure continuum models like COSMO can be deficient here [30].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational study of solvent effects relies on a suite of key resources.

Table 3: Key Resources for Solvation and Solubility Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| BigSolDB [31] | Dataset | A large compilation of experimental solubility data for ~800 molecules in over 100 solvents, used for training and benchmarking models. |

| CPCM-X [8] | Solvation Model | The Extended Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model, used for calculating solvent-corrected electronic energies in reduction potential studies. |

| FastSolv [31] | Machine Learning Model | A fast, open-access model for predicting solubility, useful for synthetic planning and solvent selection in drug discovery. |

| OMol25 NNPs [8] | Neural Network Potential | Pre-trained machine learning potentials capable of predicting molecular energies in various charge states, often used with implicit solvation. |

Experimental Workflow for Benchmarking Solvation Models

The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for benchmarking the performance of solvation models against experimental data, as applied in studies of properties like reduction potential.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Benchmarking Solvation Models

Continuum solvation models such as PCM, CPCM, SMD, and Onsager provide powerful, computationally efficient tools for incorporating solvent effects into quantum chemical calculations. The choice of model involves a trade-off between physical rigor, computational cost, and parameterization for specific tasks. SMD stands out for solvation free energies, CPCM offers efficiency for high-dielectric solvents, and IEFPCM provides a robust general-purpose framework. The simpler Onsager model remains of historical interest but is limited for modern applications. As computational chemistry continues to drive innovations in drug development and materials science, the informed selection and application of these solvation models remain crucial for achieving predictive accuracy and reliable mechanistic insights. Future progress will likely involve tighter integration of continuum models with explicit solvent representations and machine-learning approaches to overcome current limitations in modeling specific solvation effects.

Theoretical models have profoundly impacted the understanding of organic reactions in solution, including mechanism elucidation, transition state stabilization, and solute-solvent interactions [32]. Solvent effects are highly sensitive and can dramatically influence rate acceleration and stereoselectivity; in extreme cases, the reaction path itself can be perturbed by the surrounding solvent environment [32]. While continuum models like the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) offer computational efficiency, they often provide poor results when differentiating between reaction rates in protic versus aprotic solvents due to their inability to capture specific intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding [32]. A QM/MM approach, where reactants are treated quantum mechanically in the presence of explicit solvent molecules modeled with molecular mechanics, proves better suited to explore these critical solute-solvent interactions and provides a more realistic representation of solvation environments [32] [33].

Multiscale QM/MM modeling, first introduced in 1976 and recognized with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has evolved into an indispensable methodology for studying chemical processes in explicit solvent [34]. This approach allows researchers to apply accurate but computationally expensive quantum mechanical methods to the region where chemical bonds are formed and broken, while employing efficient molecular mechanics to describe the surrounding solvent molecules, thus creating realistic solvation environments at feasible computational cost [34]. The strategic combination of these methods enables the simulation of complex biomolecular systems, drug delivery mechanisms, and organic electronics with unprecedented accuracy [34].

Comparative Analysis of QM/MM Methodologies for Solvation

Fundamental QM/MM Approaches and Their Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Primary QM/MM Methodologies for Solvation Studies

| Methodology | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRF (Discrete Reaction Field) | MM atoms interact with QM region via induced dipoles and static charges [35] | Facilitates calculation of optical properties; good for excited states [35] | Limited to specific polarizable force fields; charge parameterization required [35] | Water in water solvation; UV/Vis spectroscopy of solvated systems [35] |

| QM/FQ (Quantum Mechanics/Fluctuating Charges) | MM charges determined self-consistently with QM density; can include fluctuating dipoles (QM/FQFμ) [35] | Explicit terms appear within response equations for spectroscopic properties [35] | Computationally intensive; parameterization challenges for complex solvents [35] [36] | 2-methyloxirane in water; excited-state properties [35] |

| Adaptive QM/MM | Molecules reassigned to QM/MM regions during simulation; dual-sphere approach [33] | Accurately accounts for solvent reorganization along reaction path [33] | Implementation complexity; higher computational overhead [33] | Nucleophilic addition to carbonyl groups; diffusive systems [33] |

| Four-Tier QM/MM | Combines docking, QM/MM optimization, constrained MD, and single-point QM/MM [37] | High correlation with experimental binding affinities (R² = 0.90) [37] | Extremely resource-intensive; complex workflow [37] | Metalloprotein inhibitor binding (MMP-9 hydroxamates) [37] |

Performance Benchmarks Across Solvation Models

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Solvation Models for Chemical Reactions

| Reaction System | Methodology | Performance Metrics | Reference Data | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menshutkin Reaction (methyl chloride + ammonia) | QM/MM/MC with PDDG/PM3 [32] | Quantitative agreement with experimental rates across solvents [32] | Free energies of activation within 2-3 kcal/mol of experiment [32] | Moderate (semiempirical QM) |

| Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (azide + 4-fluoronitrobenzene) | QM/MM/MC with PDDG/PM3 [32] | Reproduced solvent effects on activation barriers [32] | ~5 kcal/mol lower barrier in DMSO vs water [32] | Moderate (semiempirical QM) |

| Kemp Decarboxylation | QM/MM/MC with PDDG/PM3 [32] | Captured 7-8 order of magnitude rate acceleration [32] | Dramatic rate effects from protic to aprotic solvents [32] | Moderate (semiempirical QM) |

| Nucleophilic Carbonyl Addition (Me₂N–(CH₂)₃–CH=O) | Continuous Adaptive QM/MM [33] | Accurate solvent reorganization along reaction path [33] | Superior to microsolvation models [33] | High (ab initio QM) |

| MMP-9 Hydroxamate Inhibitors (28 compounds) | Four-tier QM/MM [37] | 90% variance explained in inhibition constants [37] | Kᵢ range: 0.08-349 nM; error: 0.318 log units [37] | Very High (multiple stages) |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for QM/MM Solvation Studies

Protocol 1: Standard QM/MM Setup for Solvation Studies

The following protocol outlines the fundamental steps for setting up a QM/MM solvation simulation, adaptable for studying various chemical reactions in solution [35]:

System Preparation

Region Definition

- Use the Regions command to partition the system [35]

- Designate the 'Solute' region (QM treatment) containing reacting molecules [35]

- Designate the 'Solvent' region (MM treatment) containing explicit solvent molecules [35]

- For adaptive QM/MM, define transition regions with fractional QM character [33]

Method Selection

- For electrostatic embedding: Select DRF method for induced dipole interactions [35]

- For polarizable force fields: Enable QM/FQ for fluctuating charges [35]

- Choose QM method (DFT for accuracy, semiempirical for large systems) [32] [34]

- Select MM force field (OPLS, TIP4P for water, or polarizable variants) [32] [36]

Property Calculations

Protocol 2: Four-Tier Approach for Metalloprotein Ligand Binding

This sophisticated protocol combines multiple computational techniques to overcome force field limitations in describing coordination bonds [37]:

Docking with Metal-Binding Guidance

QM/MM Geometry Optimization

Constrained Molecular Dynamics Sampling

Single Point QM/MM Energy Calculation

Workflow Visualization: QM/MM for Solvation Environments

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for implementing QM/MM methodologies in solvation studies:

Diagram 1: QM/MM Methodology Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for QM/MM Solvation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Applicable Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM Software | AMS (Amsterdam Modeling Suite) [35] | Performs QM calculations with various functionals and basis sets | DRF, QM/FQ [35] |

| QM Methods | DFT (B3LYP, PBE, M06), Semiempirical (PDDG/PM3) [32] [34] | Describes electronic structure of QM region | All QM/MM variants [32] [34] |

| MM Force Fields | OPLS, TIP4P water model [32] | Describes classical interactions in solvent environment | QM/MM, QM/MM/MC [32] |

| Polarizable Models | Drude oscillator, Induced dipole, Fluctuating charge [36] | Enables environment-responsive electrostatics | DRF, QM/FQ [35] [36] |

| Sampling Methods | Molecular Dynamics, Monte Carlo [32] [37] | Configurational sampling of solvent molecules | QM/MM/MD, QM/MM/MC [32] [37] |

| Analysis Tools | Custom scripts for energy decomposition [37] | Extracts interaction energies and solvent contributions | Four-tier approach [37] |