Stereochemistry and Isomerism in Drug Development: From Molecular Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of stereochemistry and isomerism for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Stereochemistry and Isomerism in Drug Development: From Molecular Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of stereochemistry and isomerism for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of stereoisomers, enantiomers, and diastereomers, explores advanced methodological approaches for stereochemical analysis and resolution, addresses common challenges in bioanalytical method development, and discusses rigorous validation techniques for absolute configuration determination. The content highlights the critical impact of molecular chirality on drug safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance, with practical insights from pharmaceutical case studies including thalidomide, beta-lactams, and chiral switches.

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Symmetry and Isomerism

Stereochemistry, the study of the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in molecules, is a fundamental discipline with profound implications across chemistry, biology, and medicine. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of stereochemistry, exploring how molecular geometry dictates properties and functions in chemical and biological systems. Within the broader context of isomerism research, we examine how stereoisomers—identical in atomic connectivity but divergent in spatial orientation—exhibit dramatically different biological activities, physical properties, and reactivities. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering stereochemistry is not merely academic but crucial for designing effective pharmaceuticals, understanding biochemical pathways, and developing advanced materials. This guide provides a technical foundation of stereochemical concepts, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and analytical methodologies essential for contemporary research and development.

Stereochemistry is the branch of chemistry concerned with the three-dimensional (3D) arrangement of atoms and molecules and how this spatial configuration influences their properties and reactions [1]. It is often described as the "chemistry of space," stemming from the Greek word "stereos," meaning solid or three-dimensional [2]. In the broader research landscape of molecular isomerism, stereochemistry specifically addresses stereoisomers—molecules that share the same molecular formula and atomic connectivity (bonding sequence) but differ in the orientation of their atoms in space [2].

This spatial arrangement is critical because it directly governs how a molecule interacts with biological targets, its chemical reactivity, and its physical properties. In essence, the 3D structure of a molecule is as fundamental to its identity and function as its 2D connectivity. For drug development professionals, this is paramount; the pharmacological activity of a compound is often exclusively dependent on its correct stereochemical configuration [3]. A molecule with the "wrong" handedness may be inactive, less potent, or even cause toxic side effects, as tragically demonstrated by the drug thalidomide [4].

The study of stereochemistry intersects with all domains of chemistry—organic, inorganic, and physical—but is particularly critical in organic chemistry and biochemistry, where chiral molecules are ubiquitous. Understanding stereochemistry allows scientists to rationalize reaction outcomes, design asymmetric syntheses, and predict the behavior of molecules in complex environments, from catalytic systems to living organisms.

Fundamental Concepts and Classification of Stereoisomers

At the heart of stereochemistry lies the concept of chirality. A molecule is considered chiral if it cannot be superimposed on its mirror image, much like a left and right hand [3] [2]. This property most commonly arises from a chiral center, typically a carbon atom with four different substituents [3]. The two non-superimposable mirror images of a chiral molecule are called enantiomers [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Stereoisomers

| Type | Definition | Key Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enantiomers | Mirror images that are not superimposable [2]. | Have identical physical properties except for the direction they rotate plane-polarized light; often exhibit different biological activities [3]. | D- and L-glucose [5]. |

| Diastereomers | Stereoisomers that are not mirror images [2]. | Have different physical and chemical properties [2]. | cis- and trans- isomers; different forms of tartaric acid [2]. |

| Cis-Trans Isomers | A subtype of diastereomerism in alkenes or rings, where groups are on the same (cis) or opposite (trans) sides [2]. | Cis isomers often have higher boiling points and lower melting points than their trans counterparts [2]. | cis- and trans-2-butene [2]. |

Chiral molecules are optically active, meaning they rotate the plane of plane-polarized light. One enantiomer rotates light clockwise (dextrorotatory, labeled (+)) and the other counterclockwise (levorotatory, labeled (–)) [3]. The absolute configuration of a chiral center is unambiguously described using the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) system, which assigns an ( R ) (from Latin rectus) or ( S ) (from Latin sinister) descriptor based on the atomic numbers of the substituents [3]. For sugars and amino acids, an older but still prevalent D/L system is used, which references the absolute configuration of D- or L-glyceraldehyde [5].

When a chiral compound is synthesized in the lab without a chiral influence, it typically forms a racemic mixture (or racemate), a 50:50 mixture of both enantiomers [3]. In a chiral environment, such as the human body, enantiomers can behave as entirely different substances. For instance, the D-enantiomer of the drug isoproterenol is effective for treating heart rate issues, whereas the L-enantiomer acts on blood pressure [4].

Analytical Methods for Determining Stereochemistry

Determining the precise three-dimensional structure of a molecule is a critical step in research. The methodologies can be broadly categorized into physical, spectroscopic, and chemical techniques, each providing complementary information.

Physical and Spectroscopic Methods

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Stereochemical Determination

| Method | Underlying Principle | Application in Stereochemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Polarimetry | Measures the rotation of plane-polarized light by a chiral substance [2]. | Determines optical activity and enantiomeric purity; used to quantify the specific rotation ([α]) of a sample. |

| X-ray Crystallography | Uses X-ray diffraction patterns from a crystallized sample to determine electron density [2]. | Provides the most direct and unambiguous determination of absolute configuration and the 3D arrangement of all atoms in a molecule. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Exploits the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei in a magnetic field [2]. | 1H/13C NMR: Reveals connectivity and chemical environment.NOE (Nuclear Overhauser Effect): Measures through-space interactions to determine relative configuration and conformation [2]. |

| Chiral Derivatization | Converts enantiomers into diastereomers by reacting with a single-enantiomer chiral reagent [2]. | Allows for the separation and analysis of enantiomers using standard achiral methods like HPLC or GC, as diastereomers have different physical properties. |

The experimental workflow for structural elucidation often integrates multiple techniques, as shown in the following protocol.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Enantiomeric Excess (e.e.) via Chiral HPLC

Objective: To determine the enantiomeric purity of a chiral synthesis product.

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve a small quantity (∼1-5 mg) of the synthesized chiral compound in a suitable solvent (e.g., hexane/isopropanol mixture) to a concentration of approximately 1 mg/mL. Filter the solution through a 0.45 μm syringe filter to remove particulates.

- Chiral HPLC Setup:

- Column: Install a dedicated chiral stationary phase column (e.g., amylose- or cellulose-based).

- Mobile Phase: Prepare an isocratic or gradient eluent, often a mixture of alkane and alcohol (e.g., 90:10 Hexane:Isopropanol).

- Conditions: Set flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min), column temperature (e.g., 25 °C), and detection wavelength (e.g., UV-Vis at 254 nm).

- Calibration and Analysis:

- First, inject the racemic mixture (if available) to establish retention times for both enantiomers and ensure baseline resolution.

- Inject the synthesized sample.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the peak areas for each enantiomer. Calculate the enantiomeric excess (e.e.) using the formula: [ e.e. (\% ) = \frac{| [R] - [S] |}{[R] + [S]} \times 100 = \frac{| AreaR - AreaS |}{AreaR + AreaS} \times 100 ] A high e.e. indicates a highly enantioselective synthesis.

Quantitative Models and Machine Learning in Stereochemistry

Moving beyond qualitative understanding, quantitative models are essential for predicting stereochemical outcomes. A prominent example is the statistical mechanical model used to quantify stereochemical communication in metal-organic assemblies [6]. This model treats each metal center in a self-assembled cage as a two-state system (Δ or Λ configuration). It introduces two key parameters:

- Intra-vertex coupling ((f_1)): The free energy penalty for incorporating an "incorrect" chiral amine enantiomer at a single metal center, quantifying the local chiral induction strength.

- Inter-vertex coupling ((f_2)): The free energy associated with a ligand connecting metal centers with opposite configurations, quantifying the propagation of stereochemical information across the assembly [6].

By fitting experimental data from "sergeant-and-soldiers" experiments to this model, researchers can extract (f1) and (f2) values, providing a unified understanding of how factors like metal ion identity, ligand length, and chiral residue structure influence the overall stereochemistry of complex supramolecular systems [6].

More recently, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for quantitatively predicting stereoselectivity, a task traditionally difficult for computational methods. A composite ML approach has been developed to predict enantioselectivity ((\Delta \Delta G^\ddag)) for chiral phosphoric acid (CPA)-catalyzed reactions [4].

Table 3: Machine Learning Models for Predicting Enantioselectivity

| ML Algorithm | Application Example | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Prediction of enantioselectivity in glycosylation and asymmetric catalytic reactions [4]. | Handles non-linear relationships and interactions between molecular features. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Prediction of enantioselectivities in thiol addition to N-acylimines [4]. | Effective in high-dimensional spaces. |

| LASSO Regression | Feature selection and prediction for asymmetric phenolic dearomatization [4]. | Performs variable selection and regularization to enhance prediction accuracy. |

| Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Predicting enantioselectivity of catalytic asymmetric β-C-H bond activation [4]. | Capable of learning complex, hierarchical patterns from large datasets. |

The ML workflow involves training models on datasets comprising hundreds of reactions, with features derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations and molecular topologies describing the catalyst, solvent, nucleophile, and imine components [4]. The composite method uses Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning and a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to cluster new reactions and assign the most appropriate pre-trained ML model for accurate prediction of (\Delta \Delta G^\ddag) [4].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The impact of stereochemistry is perhaps most acutely felt in the pharmaceutical industry, where the principle that "enantiomers should be considered different drugs" is a guiding tenet [3]. Approximately 50% of marketed drugs are chiral, and of these, about half were initially sold as racemic mixtures [3].

Single-Enantiomer Drugs offer several potential advantages over racemates:

- Improved Pharmacologic Profile: Often, the therapeutic activity resides predominantly in one enantiomer (the eutomer), while the other (the distomer) may be inactive or contribute to side effects [3] [7].

- Simpler Pharmacokinetics: Enantiomers can be metabolized at different rates, leading to complex pharmacokinetics for a racemate. Using a single enantiomer simplifies the dose-response relationship [3].

- Reduced Drug Interactions: The distomer may inhibit enzymes or interact with off-target receptors, leading to unwanted drug interactions [3].

A classic case is the antidepressant citalopram and its single-enantiomer derivative escitalopram. Citalopram is a racemic mixture, but the (S)-enantiomer (escitalopram) is responsible for the serotonin reuptake inhibition. The (R)-enantiomer is not only less active but may counteract the therapeutic effects of the (S)-enantiomer. Clinically, 10 mg of escitalopram was shown to be as effective as 40 mg of the racemic citalopram, demonstrating the profound therapeutic advantage of the single-enantiomer formulation [7].

Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require strict control over stereochemistry. Sponsors must identify the stereochemical composition of a drug substance, develop chiral analytical methods early, and justify the choice of developing a racemate versus a single enantiomer [7]. This has led to the strategy of "chiral switching," where a company develops a single-enantiomer version of a previously racemic drug, as seen with esomeprazole (Nexium) from omeprazole (Prilosec) [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stereochemical Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Stationary Phase (CSP) HPLC Columns | To separate and analyze enantiomers based on their differential interaction with a chiral solid phase [7]. | Determining enantiomeric purity (e.e.) of synthesis products; analytical and preparative separation. |

| Chiral Solvating Agents (CSAs) | To form transient diastereomeric complexes with enantiomers in solution, making them distinguishable by NMR [2]. | NMR analysis for enantiomeric composition and absolute configuration assignment. |

| Chiral Catalysts (e.g., Chiral Phosphoric Acids - CPAs) | To catalyze reactions enantioselectively, favoring the formation of one enantiomer over the other [4]. | Asymmetric synthesis, such as the addition of nucleophiles to imines to create chiral centers with high e.e. |

| Chiral Derivatizing Agents | To covalently attach a chiral moiety to enantiomers, converting them into diastereomers with different physical properties [2]. | Enabling separation of enantiomers on achiral chromatographic systems or analysis by other methods. |

| Enantiopure Building Blocks (e.g., D-/L- amino acids, sugars) | Serve as chiral starting materials or templates with a known, defined absolute configuration [5]. | Synthesis of complex chiral molecules, peptides, and natural products in a stereocontrolled manner. |

Stereochemistry is a foundational pillar of modern chemical science, inextricably linking the three-dimensional architecture of a molecule to its function. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep and practical understanding of stereochemical principles is non-negotiable. It is critical for interpreting spectroscopic data, designing synthetic routes, predicting biological activity, and ensuring the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical agents. The field continues to evolve, with advanced quantitative models and machine learning approaches now providing powerful tools to predict and rationalize stereoselectivity, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods. As research delves deeper into complex molecular systems, from supramolecular cages to novel energetic materials, the principles of stereochemistry will remain central to innovation and discovery.

Isomerism constitutes a foundational concept in organic chemistry and a critical consideration in modern drug discovery and development. It describes the phenomenon whereby molecules share the same molecular formula but differ in the arrangement of their atoms [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a nuanced understanding of isomerism is not merely academic; it directly impacts the physicochemical properties, biological activity, metabolic fate, and ultimate therapeutic efficacy of molecular entities [9]. The broadest classification divides isomers into two primary categories: structural isomers (also known as constitutional isomers) and stereoisomers [10] [11]. This classification is paramount because the "type" of isomerism dictates the strategies required for synthesis, separation, analysis, and purification—processes central to pharmaceutical development [9].

The significance of this field is powerfully illustrated by historical lessons. The case of thalidomide, a drug administered as a racemic mixture in the late 1950s, remains a stark reminder. While one enantiomer provided the desired sedative effect, its mirror image isomer caused severe teratogenic effects [12]. This tragedy underscored the critical importance of stereochemistry in pharmacology and catalyzed a paradigm shift in how regulatory agencies evaluate chiral drugs, compelling the industry to develop sophisticated methods for isomer-specific synthesis and analysis [12]. Within the context of a broader thesis on stereochemistry, this guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for classifying isomers, complete with experimental protocols essential for research and development.

Foundational Concepts and Classification Framework

At its core, isomerism recognizes that a single molecular formula can correspond to multiple, distinct chemical entities. The fundamental dichotomy in isomer classification rests on the nature of the difference between these entities.

Structural Isomers (Constitutional Isomers) are defined by a different connectivity of atoms [8] [13]. They possess the same molecular formula but differ in the sequence in which their atoms are bonded together. This different bonding architecture inherently means that structural isomers are different compounds with unique IUPAC names and often vastly different chemical and physical properties [11].

Stereoisomers, by contrast, share the same atomic connectivity (the same structural formula) but differ in the three-dimensional orientation of their atoms in space [14]. This category includes a range of isomers from enantiomers to conformational isomers, all of which are detailed in the sections that follow.

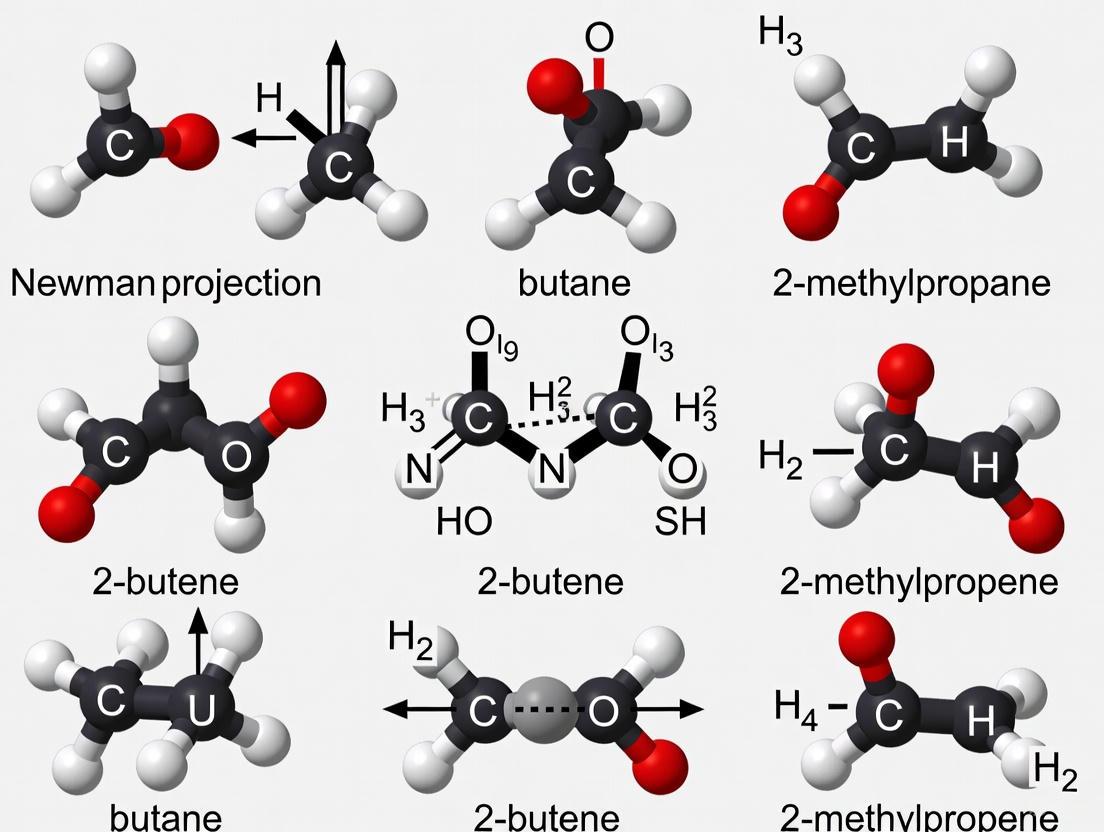

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision tree for classifying isomers, providing a roadmap for researchers to categorize any given pair of molecules.

Figure 1: Logical workflow for isomer classification.

Structural Isomerism

Types and Examples

Structural isomerism arises when atoms are bonded in a fundamentally different sequence. The different connectivities lead to distinct skeletal frameworks and/or functional groups. The table below summarizes the primary types of structural isomerism, which include chain, position, and functional group isomerism [8] [15].

Table 1: Classification and Examples of Structural Isomerism

| Type of Structural Isomerism | Defining Principle | Example Molecular Formula | Example Isomers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chain Isomerism [8] [13] | Different arrangements of the carbon skeleton (e.g., straight chain vs. branched) | C4H10 | Butane (straight-chain), 2-Methylpropane (branched) |

| Position Isomerism [8] [15] | Same functional group or substituent located at different positions on the same carbon skeleton | C5H11Br | 1-Bromopentane, 2-Bromopentane, 3-Bromopentane |

| Functional Group Isomerism [8] [15] | Different functional groups, leading to compounds from different homologous series | C3H6O | Propanal (aldehyde), Propanone (ketone) |

Experimental Protocols for Separation and Analysis

The separation of structural isomers is typically feasible through standard chemical methods because their different connectivities impart significant differences in physical properties like boiling point, melting point, and polarity.

Protocol 1: Fractional Distillation for Chain Isomers

- Principle: Leverages differences in boiling points (bp) arising from variations in molecular surface area and branching. Linear isomers typically have higher boiling points than branched isomers due to stronger London dispersion forces [8].

- Methodology: The isomeric mixture is heated in a distillation apparatus. For example, to separate the chain isomers of C5H12, the mixture is carefully heated. n-Pentane (bp ~36°C) distills over first, followed by isopentane (bp ~28°C), and finally neopentane (bp ~10°C) [8]. The fractions are collected separately based on their predetermined boiling point ranges.

- Key Analysis: Purity of collected fractions is confirmed by Gas Chromatography (GC), comparing retention times against authentic samples.

Protocol 2: Chromatographic Separation for Positional Isomers

- Principle: Utilizes differences in polarity and adsorption affinity. For instance, 1-Bromopentane is slightly less polar than 2-Bromopentane due to the position of the polar bromine atom relative to the alkyl chain [15].

- Methodology: Column Chromatography. The isomeric mixture is applied to a silica gel column. A non-polar mobile phase (e.g., hexane) is used initially, gradually increasing polarity with a more polar solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). The less polar isomer elutes first.

- Key Analysis: Fractions are collected and analyzed by Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC). Further structural confirmation is achieved using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, where the chemical shifts and splitting patterns of protons near the functional group are diagnostically different [13].

Stereoisomerism

Stereoisomers possess an identical bond connectivity but a different spatial arrangement of atoms. This broad category is first divided into configurational isomers and conformational isomers. Configurational isomers are stereoisomers that cannot be interconverted readily because the process requires breaking and reforming bonds (e.g., enantiomers, diastereomers, cis-trans isomers) [14]. Conformational isomers, on the other hand, can be interconverted rapidly by rotation around single bonds (e.g., the chair and boat forms of cyclohexane) [14] [16].

Table 2: Classification of Stereoisomers with Defining Features

| Category | Subtype | Key Defining Feature | Example | Separable at RT? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configurational Isomers | Enantiomers [14] [12] | Non-superimposable mirror images; contain chiral centers. | D- & L-lactic acid [15] | Yes |

| Diastereomers [14] [11] | Stereoisomers that are not mirror images. | Cis- & Trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane [16] | Yes | |

| Geometric (Cis-Trans/E-Z) [14] [10] | Differ in arrangement about a double bond or ring due to restricted rotation. | Cis- & Trans-2-butene [10] | Yes | |

| Conformational Isomers | Rotamers (e.g., Staggered, Eclipsed) [16] | Differ by rotation around a single bond. | Staggered & Eclipsed ethane | No |

| Ring Conformers [16] | Different puckering modes of a ring system. | Chair & Boat cyclohexane | No |

Enantiomers and Chirality

Enantiomers are a pair of stereoisomers that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other [12] [16]. A molecule that is not superimposable on its mirror image is described as chiral. The most common source of chirality is a chiral center, typically a carbon atom bonded to four different substituents [12].

- Optical Activity: The most defining property of enantiomers is their ability to rotate the plane of plane-polarized light. One enantiomer will rotate the light in a clockwise direction (dextrorotatory, labeled as (+) or d), while the other will rotate it counterclockwise (levorotatory, labeled as (-) or l) by an equal magnitude [12].

- Physical and Biological Properties: Enantiomers have identical physical properties (melting point, boiling point, solubility) in an achiral environment. However, their interactions with other chiral molecules, such as biological receptors and enzymes, can be dramatically different, leading to distinct pharmacological effects, as seen with thalidomide [12].

Diastereomers, Geometric Isomers, and Conformers

- Diastereomers: These are stereoisomers that are not mirror images [14] [11]. Unlike enantiomers, diastereomers have different physical properties (e.g., melting points, solubilities) and can therefore be separated by conventional techniques like fractional crystallization or chromatography [12].

- Geometric Isomers (Cis-Trans / E-Z): This form of diastereomerism arises from restricted rotation around a double bond or in a ring system [14] [10]. In the E/Z system (used for more complex alkenes), priority is assigned to substituents based on atomic number. If the two highest-priority groups are on the same side, it is the Z-isomer (zusammen, together); if on opposite sides, it is the E-isomer (entgegen, opposite) [14].

- Conformational Isomers: These represent different spatial arrangements of atoms achieved by rotation around single bonds [14] [16]. In cyclohexane, the chair conformation is the most stable energy minimum, while the boat conformation represents a higher-energy form. Despite being rapidly interconverting, different conformers can have profoundly different steric and electronic environments, influencing reactivity.

Experimental Protocols for Stereoisomer Analysis

Protocol 3: Polarimetry for Enantiomer Characterization

- Principle: Measures the angle and direction by which a chiral compound rotates plane-polarized light [12].

- Methodology: A solution of the pure chiral compound is prepared in a suitable solvent at a known concentration (c, in g/mL) and placed into a sample cell of specific path length (l, in dm). The polarimeter is zeroed with the pure solvent. The sample is inserted, and the observed rotation (α) is measured. The specific rotation [α] is calculated as: [α] = α / (l * c).

- Key Analysis: The specific rotation is a physical constant used to identify and characterize enantiomers. A racemic mixture (a 50:50 mixture of enantiomers) will show no net optical rotation [12].

Protocol 4: Chiral Chromatography for Enantiomer Separation

- Principle: Uses a chromatographic column with a chiral stationary phase (CSP) that interacts differentially with each enantiomer, creating a diastereomeric interaction complex and allowing separation [9].

- Methodology: The racemic mixture is injected into a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a CSP (e.g., cyclodextrin, macrocyclic glycopeptide). An achiral mobile phase is used. The two enantiomers, interacting differently with the CSP, elute at different retention times (tR1 and tR2).

- Key Analysis: The resolution (Rs) between the two peaks is calculated. The identity of each peak can be confirmed by comparison with the known specific rotation of the collected fractions or by co-injection with a pure enantiomer standard.

The following diagram visualizes the key instrumental workflow for separating and analyzing stereoisomers, integrating chiral chromatography and polarimetry.

Figure 2: Workflow for chiral separation and analysis.

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Isomer Research

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for experimental work in isomer synthesis, separation, and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Isomer Research

| Reagent/Material/Instrument | Primary Function in Isomer Research |

|---|---|

| Silica Gel (for Column Chromatography) [13] | A polar stationary phase for separating structural isomers and diastereomers based on adsorption affinity differences. |

| Chiral HPLC Columns [9] | Columns with a chiral stationary phase (CSP) for the analytical and preparative separation of enantiomers. |

| Polarimeter [12] | Instrument for measuring the optical activity of chiral compounds, used to determine enantiomeric purity and identity. |

| Chiral Derivatizing Agent (e.g., MTPA-Cl) | A chiral reagent that reacts with a racemic mixture to form a pair of diastereomers, which can then be separated using standard achiral methods (e.g., silica gel chromatography). |

| Deuterated Solvents (for NMR) | Essential solvents for NMR spectroscopy, used to confirm molecular structure, identify isomer type, and determine enantiomeric purity using chiral shift reagents. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Instrument for separating and analyzing volatile mixtures of isomers, particularly effective for chain and positional isomers. |

The rigorous classification of isomers into structural and stereoisomers provides an indispensable framework for scientific research, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. The ability to distinguish, separate, and characterize these molecular variants is not a mere academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for developing safe and effective therapeutics. As the field advances, the focus on isomer-specific drug formulations is intensifying, driven by the demands of personalized medicine and the lessons of history [9]. The experimental protocols and analytical techniques outlined in this guide form the bedrock of this endeavor. Future research will continue to leverage advancements in nanotechnology, computational modeling, and synthetic methodology to achieve ever-greater control over molecular geometry, pushing the boundaries of drug delivery and therapeutic efficacy [17] [9]. A deep and practical understanding of isomerism, as detailed in this comprehensive guide, remains a cornerstone of innovation in chemistry and drug development.

Chirality, derived from the Greek word for "hand," describes the fundamental geometric property of a molecule that is non-superimposable on its mirror image [18]. This "handedness" in molecular architecture is not merely an abstract chemical concept but a critical determinant of biological activity, particularly in pharmaceutical science. The three-dimensional spatial arrangement of atoms around specific stereogenic elements dictates how a drug molecule interacts with its biological targets, which are themselves chiral entities such as proteins, enzymes, and receptors [19] [18]. The historical recognition of this phenomenon dates back to Louis Pasteur's 1848 manual separation of tartaric acid crystals, which established the foundational principles of molecular asymmetry [19] [18].

In pharmaceutical contexts, the distinction between enantiomers—non-superimposable mirror image molecules—can mean the difference between therapeutic benefit and detrimental toxicity. The tragic case of thalidomide, where one enantiomer provided desired sedative effects while its mirror image caused severe birth defects, starkly illustrates the life-or-death implications of stereochemistry in drug development [18]. Modern regulatory agencies now require rigorous stereochemical evaluation of new drug candidates, recognizing that enantiomers can exhibit marked differences in pharmacology, toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism [19]. Contemporary research indicates that over half of all marketed drugs are chiral compounds, with approximately 90% of these historically marketed as racemic mixtures (equimolar combinations of both enantiomers), though current practice increasingly favors development of single-enantiomer drugs [19].

Stereogenic Elements: Beyond the Carbon Center

Classical Stereogenic Centers

Traditional stereochemistry has primarily focused on carbon-centered chirality, where a tetrahedral carbon atom bears four distinct substituents [18]. This asymmetric carbon center represents the most prevalent stereogenic element in organic molecules and pharmaceuticals. The configuration around such centers is conventionally described using the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules, which assign descriptors of R (rectus) or S (sinister) based on the atomic numbers and masses of substituents systematically arranged in three-dimensional space [19]. In molecular representations, wedge-dash notation depicts three-dimensional orientation with solid wedges indicating bonds projecting toward the viewer and hashed wedges representing bonds receding away from the viewer [18]. For molecules with multiple chiral centers, Fischer projections provide a two-dimensional schematic representation where horizontal lines indicate bonds projecting outward from the plane and vertical lines represent bonds extending behind the plane [18].

Table 1: Classical and Emerging Stereogenic Elements in Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Stereogenic Element Type | Structural Basis | Configuration Descriptors | Pharmaceutical Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon center | Tetrahedral carbon with four different substituents | R/S | (S)-Propranolol, (S)-Naproxen |

| Nitrogen center | Tertiary amines in rigid skeletons | N-inversion limited | Quinine derivatives |

| Chiral axis | Restricted rotation around single bonds | P/M (or R/S) | Atropisomeric drugs |

| Chiral plane | Helical or planar structures with hindered rotation | N/A | Helicenes |

| All-heteroatom spiro center | Carbon with four heteroatom substituents (O, N) | R/S | UNIGE experimental molecules |

Emerging Heteroatomic Stereogenic Elements

While carbon-centered chirality has been extensively studied, recent research has revealed the substantial importance and unique challenges of heteroatomic stereogenic elements. Nitrogen-centered chirality has proven particularly challenging to control due to the relatively low inversion barrier between nitrogen enantiomers, which typically leads to rapid racemization [20]. Strategies to stabilize chiral nitrogen centers include incorporation into quaternary ammonium salts, amine N-oxides, metal coordination complexes, or rigid polycyclic skeletons as found in natural products like quinine [20]. Boron-centered chirality has also emerged as a significant frontier, particularly in pharmaceutical and materials chemistry [20].

A groundbreaking advance comes from researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and University of Pisa, who have designed a novel family of chiral molecules featuring an unprecedented all-heteroatom-substituted carbon spiro stereocenter [21] [22]. Unlike traditional chiral centers where carbon is bound to carbon-based substituents, these innovative structures feature a central carbon atom bonded exclusively to oxygen and nitrogen atoms [21]. This architectural approach represents "a major conceptual and experimental breakthrough" in stereochemistry, marking the first isolation of such molecules in stable form [21] [22].

The most remarkable property of these novel chiral molecules is their exceptional configurational stability. Using dynamic chromatography and quantum chemistry calculations, researchers demonstrated that the half-life for racemization (conversion from one enantiomer to its mirror image) reaches approximately 84,000 years at room temperature for one molecule, and 227 days at 25°C for another variant [21] [22]. This extraordinary stability—essentially creating 'mirror-proof' molecular architectures—has profound implications for pharmaceutical development, as it guarantees drug integrity without requiring specialized storage conditions and prevents the transformation of therapeutic enantiomers into potentially harmful counterparts over time [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Chiral Stability and Drug Properties

The biological implications of molecular chirality are quantifiable through numerous pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. Enantioselective interactions with biological systems can produce dramatically different dose-response relationships, metabolic profiles, and toxicity thresholds between enantiomers of the same compound.

Table 2: Enantioselective Pharmacological Properties of Representative Chiral Drugs

| Drug Compound | Therapeutic Activity by Enantiomer | Potency Ratio (Eutomer:Distomer) | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | S(-): β-adrenergic blockadeR(+): Minimal β-blockadeR(+): Inhibits T4 to T3 conversion | 100:1 (β-blockade) | Racemate: contraindicated in thyroid disordersSingle R-enantiomer: potential for hyperthyroidism |

| Methadone | (R)-methadone: Opioid analgesia(S)-methadone: hERG binding, cardiac risk | N/A | (S)-enantiomer associated with QT prolongation and cardiac arrest |

| β-blockers (class) | S(-): β-adrenoceptor blockade | Varies by compound | Most marketed as racemates except timolol, penbutolol |

| Amine boranes (experimental) | Continuous N-B stereocenters | High diastereo-/enantioselectivity | Potential chiral transfer hydrogenation reagents |

Advanced Methodologies in Stereochemical Analysis and Control

Experimental Protocols for Stereochemical Construction

The precise construction of complex stereogenic architectures requires sophisticated synthetic methodologies. Recent advances in copper-catalyzed asymmetric B-H insertion reactions demonstrate state-of-the-art protocols for creating challenging continuous stereogenic centers incorporating nitrogen and boron atoms [20].

Protocol: Copper-Catalyzed Asymmetric B-H Insertion for Continuous Stereogenic Centers

- Reaction Setup: In a flame-dried Schlenk flask under inert atmosphere, combine racemic cyclic amine borane (1a, 1.0 equiv) and diaryl diazomethane (2a, 1.2 equiv) in anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) as solvent [20].

- Catalyst System: Employ copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate hydrate (CuTc, 5 mol%) with specialized bisoxazoline (BOX) ligand L1 (20 mol%) as the chiral controller [20]. The additive potassium tetrakis(perfluorophenyl)borate (KBArF, 20 mol%) is crucial for enhancing reaction efficiency [20].

- Reaction Conditions: Conduct the transformation at -70°C with strict temperature control to maintain high enantioselectivity. Reaction monitoring via TLC or in situ spectroscopy is recommended [20].

- Workup and Isolation: Upon completion, quench the reaction with saturated aqueous ammonium chloride solution. Extract with DCM (3 × 15 mL), dry the combined organic layers over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure [20].

- Purification and Analysis: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel. Analyze enantiomeric purity by chiral HPLC or SFC, and determine absolute configuration by X-ray crystallography or computational methods (e.g., DFT calculations) [20].

This protocol achieves excellent diastereoselectivity (ranging from 4.8:1 to >20:1 dr) and enantioselectivity (84-98% ee) across a broad substrate scope, including electronically varied diazo compounds and substituted amine boranes [20]. The methodology features a meaningful kinetic resolution pathway during the transformation, enabling access to enantiopure boron-coordinated nitrogen-centered compounds that serve as potential chiral transfer hydrogenation reagents [20].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Constructing Continuous Stereogenic Centers via Asymmetric B-H Insertion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Advanced Stereochemical Research

| Reagent/Catalyst | Function in Stereochemical Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral BOX Ligands (L1-L6) | Induce asymmetry in metal-catalyzed reactions | Copper-catalyzed B-H insertion [20] |

| Copper(I) Thiophene-2-carboxylate (CuTc) | Catalytic activation of B-H bonds | Stereoselective transformations [20] |

| KBArF (Potassium tetrakis(perfluorophenyl)borate) | Enhances reaction efficiency as additive | B-H insertion optimization [20] |

| Diazo Compounds | Carbene precursors for insertion reactions | Construction of C-B bonds [20] |

| Amine Boranes | Provide N-B stereogenic elements | Continuous stereocenter formation [20] |

| Chiral Stationary Phases | Enantiomer separation in chromatography | Analysis of enantiomeric purity [21] |

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

Modern stereochemical research increasingly incorporates computational methods and artificial intelligence to predict, analyze, and optimize chiral molecules. Stereochemistry-aware generative models represent a cutting-edge approach in computational drug discovery that explicitly accounts for three-dimensional molecular arrangement during the design process [23]. These models utilize string-based molecular representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System), SELFIES (SELF-Referencing Embedded Strings), and GroupSELFIES, which natively encode stereochemical information through specialized tokens denoting R/S and E/Z configurations [23].

Benchmarking studies demonstrate that stereochemistry-aware models perform comparably to or surpass conventional algorithms in stereochemistry-sensitive tasks, including optimization of binding affinity, metabolic stability, and optical activity [23]. However, researchers must consider the trade-off between stereochemical precision and chemical space complexity, as stereo-aware models navigate an expanded molecular landscape that includes all possible stereoisomers [23]. These computational approaches are particularly valuable for predicting the biological activity of enantiomers and avoiding problematic stereochemical configurations, such as the (S)-methadone enantiomer associated with hERG channel binding and cardiotoxicity [23].

Figure 2: Computational Workflow for Stereochemistry-Aware Molecular Generation

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of stereochemistry in drug molecules continues to evolve with several promising research frontiers. Catalytic deracemization strategies represent a paradigm shift in accessing single enantiomers from racemic mixtures without traditional separation techniques. The CALIDE (Catalytic Light-induced Deracemization) project explores photochemical approaches that temporarily erase stereogenic information and recreate it using light as the exclusive energy source, potentially establishing "one of the key pillars on which the future preparation of enantiomerically pure compounds will rest" [24].

The development of continuous stereogenic frameworks incorporating multiple heteroatoms (N-B, N-B-C) expands the toolbox for designing molecular architectures with precisely controlled three-dimensional shapes [20]. These complex chiral environments enable fine-tuning of drug-target interactions that may lead to improved specificity and reduced off-target effects. Additionally, the integration of stereochemistry-aware machine learning models into drug discovery pipelines promises to accelerate the identification of optimal chiral configurations while avoiding problematic stereochemical features associated with toxicity or metabolic instability [23].

As these technologies mature, the pharmaceutical industry is poised to transition from primarily carbon-centered chirality to embrace diverse stereogenic elements including stable heteroatomic centers, axial chirality, and helical structures. This expansion of the stereochemical lexicon will provide medicinal chemists with unprecedented control over molecular geometry, ultimately enabling the design of safer, more effective therapeutic agents with precisely optimized three-dimensional architectures.

Stereochemistry, the study of the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in molecules, is a fundamental concept with profound implications in organic chemistry and biological research. A molecule's spatial orientation directly dictates its interactions with biological systems, making stereochemistry not merely an academic exercise but a critical consideration in fields such as drug discovery and development [25]. Isomers—molecules with identical molecular formulas but different atom arrangements—are broadly categorized into constitutional isomers (differing in bond connectivity) and stereoisomers (identical connectivity but different spatial arrangement) [11] [26]. Stereoisomers are further subdivided into enantiomers and diastereomers, two classes that exhibit distinct properties and biological behaviors. Within the chiral environment of biological systems, these differences can dictate efficacy, toxicity, and the overall fate of a molecule, underscoring the necessity for researchers to adeptly identify and separate these isomers [27] [28].

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Stereoisomers: Enantiomers and Diastereomers

Stereoisomers share the same atomic connectivity but differ in the orientation of their atoms in three-dimensional space [11]. This difference arises from the presence of stereogenic centers, most commonly chiral carbon atoms bonded to four different substituents [3].

- Enantiomers are pairs of stereoisomers that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other [29] [30]. This relationship requires that all chiral centers in the molecule have opposite configurations. A molecule with one chiral center exists as a pair of enantiomers.

- Diastereomers are stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other [29] [30]. This occurs when molecules have multiple chiral centers and the configurations differ at one or more, but not all, of these centers [30]. Unlike enantiomers, which always exist in pairs, a single molecule can have multiple diastereomers.

Table 1: Core Definitions and Relationships

| Feature | Enantiomers | Diastereomers |

|---|---|---|

| Mirror Image Relationship | Non-superimposable mirror images [30] [31] | Non-mirror images [30] [31] |

| Configuration at Chiral Centers | Opposite configuration at every chiral center [30] | Different configuration at one or more, but not all chiral centers [30] |

| Number of Possible Isomers | Always a pair | Can be several molecules for a compound with multiple chiral centers [31] |

Key Differentiating Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for classifying the relationship between two stereoisomers.

Comparative Properties of Enantiomers and Diastereomers

The distinct spatial relationships between enantiomers and diastereomers manifest in significantly different physical, chemical, and biological properties.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Table 2: Comparative Physical and Chemical Properties

| Property | Enantiomers | Diastereomers |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Properties | Identical in achiral environments (melting point, boiling point, solubility in achiral solvents) [30] | Distinct (different melting points, boiling points, solubilities) [30] |

| Optical Activity | Rotate plane-polarized light equally but in opposite directions [30] | Have different specific rotations; not necessarily equal and opposite [30] |

| Interaction with Achiral Reagents | Identical chemical behavior [30] | Can exhibit different chemical reactivity [30] |

| Separation Methods | Require chiral environments (e.g., chiral chromatography, chiral resolving agents) [30] | Can often be separated by conventional techniques (e.g., distillation, recrystallization, achiral chromatography) [30] |

Biological and Pharmacological Significance

Biological systems are inherently chiral, composed of building blocks like L-amino acids and D-sugars. This homochirality means that enantiomers, despite their identical physical properties in a test tube, are perceived as completely different entities by biological systems [3]. Enzymes, receptors, and transporters can distinguish between them, leading to dramatically different pharmacological profiles [27].

- Enantioselectivity in Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity: The enantiomers of a drug can exhibit differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [27]. For instance, carrier-mediated absorption in the intestine can be enantioselective. Distribution can be influenced by preferential binding to plasma proteins like human serum albumin (HSA) or α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP). Most notably, metabolic enzymes often display high enantioselectivity, leading to different metabolic rates and pathways for each enantiomer [27]. This can result in one enantiomer being efficiently detoxified and excreted while the other is metabolized into a toxic compound [27].

- Diastereomers in Drug Action: Because diastereomers have different physical properties and 3D shapes, they bind to biological targets with distinct affinities and can produce different therapeutic or adverse effects. This makes them effectively different drugs from a pharmacological perspective.

Table 3: Biological and Pharmacological Implications

| Aspect | Enantiomers | Diastereomers |

|---|---|---|

| Binding to Biological Targets | Can have drastically different affinities and effects (e.g., one is active, the other inactive or antagonistic) [3] | Have different physical properties and 3D shapes, leading to different binding affinities and biological activities [30] |

| Metabolism | Often metabolized at different rates and/or by different pathways, potentially producing different metabolites [27] | Behave as distinct chemical entities; are metabolized differently |

| Toxicity Profile | One enantiomer may be responsible for desired effect, while the other causes side effects or toxicity (e.g., Thalidomide) [30] | Toxicity profiles are typically uncorrelated and must be evaluated separately |

| Regulatory Considerations | Requires justification for developing a racemate vs. a single enantiomer; stereochemistry must be defined early [28] | Regarded as distinct molecular entities; each requires full characterization |

Analytical Methods for Differentiation and Characterization

Determining the absolute configuration and purity of stereoisomers is crucial in research and development. The following workflow visualizes a multi-technique approach to stereochemical analysis.

Experimental Protocols for Stereochemical Analysis

1. Determination of Absolute Configuration using Chiroptical Methods

- Objective: To unambiguously assign the absolute configuration (AC) of a novel chiral compound, such as a β-lactam derivative, using a combination of computational chemistry and spectroscopic techniques [32].

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a high-purity sample of the chiral compound. For solution-based methods like Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) and Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD), select an appropriate solvent and determine the optimal concentration to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Theoretical Calculation:

- Perform a conformational search to identify all low-energy conformers of the molecule.

- Optimize the geometry of these conformers using quantum chemical methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory - DFT).

- Calculate the theoretical ECD and/or VCD spectra for the optimized conformers, applying an appropriate solvation model. The final theoretical spectrum is a Boltzmann-weighted average of the spectra of all significant conformers.

- Experimental Data Acquisition:

- Acquire the experimental ECD and VCD spectra of the compound under conditions as close as possible to the theoretical model.

- Data Analysis and Assignment: Compare the experimental spectra with the calculated theoretical spectra. A strong match between the experimental and calculated spectra for one enantiomer allows for the confident assignment of its absolute configuration [32].

2. Enantioselective Analytical Methods for Pharmacokinetic Studies

- Objective: To accurately monitor and quantify the concentration of individual enantiomers in biological matrices (e.g., plasma, urine) during pharmacokinetic studies [27].

- Methodology:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect biological samples at predetermined time points after drug administration. Pre-treat samples using techniques like protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, or solid-phase extraction to remove interfering matrix components.

- Chiral Chromatography:

- Technique: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC).

- Stationary Phase: Use a chiral stationary phase (CSP) designed to interact differentially with the two enantiomers. Common CSPs include cyclodextrins, macrocyclic glycopeptides (e.g., teicoplanin), and polysaccharide derivatives (e.g., cellulose tris-3,5-dimethylphenylcarbamate).

- Mobile Phase: Optimize the composition of the mobile phase (organic solvent, buffer pH, ionic strength) to achieve baseline separation of the enantiomers.

- Detection: Couple the chromatographic system to a sensitive detector, such as a mass spectrometer (MS) or a fluorescence detector, for specific and accurate quantification of each enantiomer at low concentrations in complex biological samples [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stereochemical Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application in Stereochemistry |

|---|---|

| Chiral Stationary Phases (CSPs) | Used in HPLC/UHPLC to physically separate enantiomers based on transient diastereomeric complex formation on the column [27]. |

| Chiral Derivatizing Agents | Achiral reagents that react with enantiomers to form covalently bonded diastereomers, which can then be separated using standard achiral chromatography [27]. |

| Chiral Solvating Agents | Additives that create a chiral environment in the solution, used in NMR spectroscopy to cause chemical shift differences between the enantiomers, allowing for their identification and quantification. |

| Enantiopure Building Blocks | Commercially available chiral synthons (e.g., amino acids, sugars, terpenes) used in asymmetric synthesis to introduce specific chirality into a target molecule. |

The distinction between enantiomers and diastereomers is a cornerstone of stereochemistry with profound practical consequences. While enantiomers are indistinguishable in achiral environments, their divergent interactions with biological systems necessitate rigorous characterization and often separate development as unique pharmaceutical agents. Diastereomers, with their distinct physical properties, are treated as different chemical compounds altogether. The drive towards developing single-enantiomer drugs, known as "chiral switches," underscores the importance of stereochemistry in improving therapeutic efficacy and safety profiles [27] [3]. For researchers, a deep understanding of these concepts, coupled with mastery of modern analytical techniques like chiroptical spectroscopy and enantioselective chromatography, is indispensable for success in drug discovery, natural product chemistry, and the development of new chiral materials.

The field of stereochemistry, which governs the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms within molecules and its profound implications for biological activity, finds its origin in a seminal 1848 experiment conducted by Louis Pasteur. While working with crystals of sodium ammonium tartrate, Pasteur observed that paratartaric acid (now known as racemic acid) consisted of two distinct types of crystals that were nonsuperimposable mirror images of one another [33]. Using tweezers, he meticulously separated these left-handed and right-handed crystals and discovered that their solutions rotated plane-polarized light in equal but opposite directions, while the original mixture was optically inactive [33] [34]. This foundational discovery of molecular chirality (from the Greek cheir, meaning "hand") revealed that molecules with identical chemical compositions could exhibit "handedness," a property Pasteur termed molecular dissymmetry [34] [35]. This whitepaper traces the trajectory from this critical observation to its indispensable role in modern pharmaceutical research and drug development, framing these developments within the broader context of stereochemistry and isomerism in organic molecules research.

Pasteur's Seminal Experiment: Methodology and Discovery

Historical and Scientific Background

In the mid-19th century, the molecular basis for optical activity was unknown. Jean-Baptiste Biot had previously established that certain organic substances, including natural tartaric acid derived from wine production, could rotate plane-polarized light [34] [35]. However, a chemically identical substance, paratartaric or racemic acid, showed no such optical activity, presenting a scientific paradox. The prevailing theory from Eilhard Mitscherlich suggested that the tartrate and paratartrate salts had identical crystalline forms, which Pasteur suspected was incorrect [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Setup

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Sodium Ammonium Tartrate Salt | The key substrate, derived from wine production sediments [33] [36]. |

| Polarimeter | An apparatus, pioneered by Biot, used to measure the rotation of plane-polarized light by a solution [34]. |

| Microscope with Magnifying Lens | Essential for observing the small hemihedral facets on the crystals [34]. |

| Tweezers | Used for the manual separation of the left-handed and right-handed crystals [33]. |

| Crystallization Dish | For the slow crystallization of a concentrated solution of the salt [33]. |

Procedure

- Crystallization: A concentrated solution of sodium ammonium tartrate was prepared and allowed to crystallize slowly at a temperature below 28 °C [34]. Pasteur noted that temperature control was critical, as higher temperatures could lead to a different crystalline form (a racemate) where the hemihedral facets would not appear [34].

- Observation and Hypothesis: Under the microscope, Pasteur observed that the crystals of the paratartrate were not identical. They exhibited small hemihedral facets—tiny faces inclined to the left or to the right—making the crystals mirror images of each other [33] [34]. This was the visual manifestation of molecular dissymmetry.

- Separation: Using tweezers, Pasteur painstakingly separated the crystals into two piles: one of "right-handed" crystals and another of "left-handed" crystals [33].

- Analysis: The crystals from each pile were dissolved in water to create separate solutions. These solutions were then analyzed using a polarimeter.

- Results: The solution of right-handed crystals rotated polarized light to the right (dextrorotatory), while the solution of left-handed crystals rotated light to the left (levorotatory) by an equal magnitude [33] [34]. An equal mixture of the two solutions resulted in no net rotation of light, explaining the inactivity of the original racemic acid.

The logical flow of Pasteur's discovery, from initial observation to the conclusive interpretation of molecular chirality, is summarized in the diagram below.

Interpretation and Significance

Pasteur correctly deduced that the dissymmetry observed in the crystals reflected a fundamental dissymmetry at the molecular level [33] [35]. He postulated that the paratartaric acid was not a pure compound but a 1:1 mixture of two different molecular species with opposite asymmetric arrangements—what we now call enantiomers [33] [36]. This discovery was revolutionary because it suggested that a molecule's properties were determined not only by the type and number of its atoms but also by their spatial arrangement. As noted in contemporary analyses, "Pasteur’s vision was extraordinary, for it was not until 25 years later that his ideas regarding asymmetric carbon atoms were confirmed" by van't Hoff and Le Bel, who proposed the tetrahedral carbon atom [33] [37].

The Bridge to Molecular Pharmacology

The principle of stereochemistry revealed by Pasteur established a fundamental code for molecular pharmacology: biological systems are inherently chiral environments [35]. Receptors, enzymes, and other macromolecular targets are themselves composed of chiral building blocks (e.g., L-amino acids) and thus interact stereospecifically with the molecules that bind to them.

Key Quantitative Examples of Stereochemistry in Drug Action

| Drug/Compound | Enantiomer/Eutomer | Pharmacological Activity | Distomer/Other Enantiomer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thalidomide [37] | (R)-thalidomide | Sedative | (S)-thalidomide (Teratogenic, causes birth defects) |

| Methadone [23] | (R)-methadone | Opioid agonist (pain relief) | (S)-methadone (Binds hERG, cardiotoxic) |

| Citalopram/Escitalopram [7] | (S)-citalopram (Escitalopram) | Potent SSRI (antidepressant) | (R)-citalopram (~30x weaker, may counteract S-isomer) |

| β-blockers (e.g., Propranolol) [7] | L-enantiomer | Beta-adrenergic blockade | D-enantiomer (Significantly less active) |

| Dopa [7] | L-DOPA | Effective for Parkinson's disease | D-DOPA (Inactive in human enzymes) |

| Tartaric Acid [33] [36] | L-tartaric acid | Naturally occurring dextrorotatory form | D-tartaric acid (Levorotatory form) |

This stereospecificity means that two enantiomers can be perceived by the body as two completely different molecules. A powerful analogy is the "lock-and-key" model, where only one key (the correct enantiomer) fits perfectly into the lock (the biological target) to elicit a response [35]. The other enantiomer may have reduced activity, no activity, or an entirely different and potentially adverse effect. This principle directly challenges the pharmaceutical industry to identify the specific stereochemical isomer responsible for a drug's efficacy and safety [35].

Modern Pharmaceutical Applications and Protocols

Stereochemistry in Drug Discovery and Development

The legacy of Pasteur's discovery is deeply embedded in every stage of modern drug development, from initial screening to regulatory approval.

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR): Medicinal chemists treat each stereoisomer as a distinct molecule during SAR exploration [7]. The eudismic ratio (the ratio of activity between the eutomer and distomer) is used to quantify the stereoselectivity of a compound for its target [7].

- Screening Libraries: There is a strategic shift from "flat" aromatic compound libraries to 3D-enriched libraries with higher Fsp3 (fraction of sp3 carbons) and stereogenic centers to improve target specificity and metabolic stability [7] [23]. Strategies involve screening either separate enantiomers or racemic mixtures followed by "deconvolution" to identify the active enantiomer [7].

- Regulatory Landscape: Regulatory bodies (ICH/FDA/EMA) require strict control over stereochemistry [7]. Guidelines mandate the identification of stereochemical composition, development of chiral analytical methods (e.g., chiral HPLC), and justification for developing a racemate versus a single enantiomer. For racemates, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of both enantiomers must be characterized [7].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Chiral Resolution Protocol

This modern methodology descends directly from Pasteur's initial manual separation.

- Diastereomeric Salt Formation: The racemic mixture of a chiral acid (or base) is reacted with a single enantiomer of a chiral base (or acid) to form a pair of diastereomeric salts [34].

- Fractional Crystallization: These diastereomeric salts have different physical properties (e.g., solubility) and can be separated through fractional crystallization.

- Regeneration: The separated diastereomeric salts are then treated with a strong acid or base to regenerate the purified enantiomers of the original compound.

Computational Drug Design

Modern in silico methods must explicitly account for stereochemistry. The workflow for stereochemistry-aware molecular generation is illustrated below.

- String-Based Representations: Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) uses "@" and "@@" tokens to denote chirality, while more robust representations like SELFIES and GroupSELFIES have native stereochemical tokens [23].

- Generative Models: Machine learning models, including reinforcement learning (RL) and genetic algorithms (GAs), are trained on databases like ZINC15 to generate novel molecular structures with targeted properties [23]. Stereochemistry-aware models explicitly incorporate stereochemical information during the generation process, which is crucial for optimizing stereochemistry-sensitive properties like binding affinity and optical activity [23]. Research shows these models perform on par with or surpass conventional models in such tasks, despite the increased complexity of the chemical search space [23].

Louis Pasteur's meticulous observation of tartrate crystals in 1848 unveiled the fundamental principle of molecular chirality, creating the field of stereochemistry. His discovery that the spatial arrangement of atoms is a critical determinant of molecular function has evolved from a foundational concept in organic chemistry to an indispensable pillar of modern pharmaceutical science. Today, from the design of 3D-enriched screening libraries and stereospecific SAR studies to the application of stereochemistry-aware AI generative models and stringent regulatory requirements, Pasteur's legacy endures. The journey from his crystals to contemporary drug development underscores a continuous thread: in the chiral world of biology, the correct three-dimensional structure is not a mere detail—it is often the very key to efficacy and safety.

Within the framework of stereochemistry and isomerism research, the existence of meso compounds presents a fascinating paradox that challenges initial assumptions about molecular chirality. By definition, a meso compound is an achiral molecule that possesses two or more chiral centers, yet is optically inactive and superimposable on its mirror image [38] [39]. This apparent contradiction to the fundamental rule that chiral centers impart chirality is resolved by the presence of specific symmetry elements within the molecule's structure [40]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding meso compounds is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for predicting optical activity, interpreting spectroscopic data, and designing syntheses where stereochemistry dictates biological activity. The most classic example is found in tartaric acid, which exists in two enantiomeric forms and one meso form, each with distinct physical properties [41]. This guide delves into the structural basis, identification protocols, and research implications of these exceptional molecules.

Structural Basis and Defining Symmetry Elements

The achirality of a meso compound arises from the presence of an internal plane of symmetry (also called a mirror plane) that bisects the molecule into two mirror-image halves [38] [42]. This symmetry element makes one half of the molecule the mirror reflection of the other, effectively canceling out the optical activity typically induced by the chiral centers [40].

A meso compound must fulfill three key criteria:

- It must contain two or more stereocenters (chiral centers) [38].

- It must possess an internal plane of symmetry [38] [43].

- It must contain stereocenters with identical substituents [38]. The chiral centers must have opposite configurations (one R and one S), leading to a net cancellation of optical rotation [38] [44].

A critical practice for researchers is recognizing that molecular conformation can obscure the plane of symmetry. Single bonds can rotate, and a molecule that appears asymmetric in one drawing may reveal a symmetry plane in a different, energetically accessible conformation [40] [44]. Therefore, analysis must consider the molecule's ability to adopt a conformation with a symmetry plane, not just its static representation.

Methodologies for Identification and Analysis

Visual Identification and the Role of Fischer Projections

Fischer projections provide a two-dimensional framework that greatly simplifies the identification of meso compounds [43]. The key is to look for a plane of symmetry that cuts through the molecule horizontally or vertically. For instance, in 2,3-dichlorobutane, the meso isomer is the one where the horizontal reflection of the top half perfectly reproduces the bottom half [43].

A common pitfall, often called the "Meso Trap," is assuming that two differently drawn structures are enantiomers when they are, in fact, the same meso molecule [44]. Two structures drawn as mirror images of a meso compound are superimposable, meaning they represent identical molecules, not a pair of enantiomers [44]. This is empirically verified by mentally rotating one representation 180° to see if it matches the other [38] [41].

Absolute Configuration (R/S) Analysis

A robust methodological approach to confirm a meso compound is to assign the absolute configuration (R or S) to each chiral center [44]. In a meso compound with two stereocenters, the configurations will be inverted relative to each other—specifically, one will be R and the other S [38] [44]. This (R,S) designation is a necessary but not sufficient condition; the substituents on the chiral centers must also be identical [44]. For example, while (2R,3S)-2,3-dibromobutane is meso, (2S,3R)-2-bromo-3-methylpentane is not, because the chiral centers lack identical substituents [44].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Molecule Types with Multiple Stereocenters

| Characteristic | Meso Compound | Enantiomeric Pair | Diastereomer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Stereoisomers | One distinct molecule [38] | Two mirror-image molecules [38] | Multiple, non-mirror-image molecules [45] |

| Superimposable on Mirror Image? | Yes [39] | No [45] | No |

| Internal Plane of Symmetry? | Yes [38] | No [38] | No |

| Optical Activity | Inactive [38] | Active (equal and opposite rotation) [45] | Varies |

| R/S Relationship | (R,S) or (S,R) [44] | (R,R) and (S,S) [44] | Differs at some, but not all, centers |

Experimental Characterization and Protocols

Experimental Determination of Optical Activity

The definitive experimental protocol for distinguishing a meso compound from a chiral one is polarimetry [45]. A polarimeter measures a compound's ability to rotate the plane of plane-polarized light.

Protocol:

- Preparation: Prepare a solution of the analyte of known concentration in an achiral solvent.

- Baseline: Pass plane-polarized light through a sample cell containing only the pure solvent to establish a baseline reading (α_solvent).

- Measurement: Replace the solvent with the analyte solution and measure the observed rotation (α_observed).

- Calculation: Calculate the specific rotation [α] using the formula: [α] = α_observed / (c * l), where c is concentration (g/mL) and l is path length (dm).

- Interpretation: A meso compound will yield a specific rotation of 0° (optically inactive), whereas a single enantiomer will show a non-zero value [α], and a racemic mixture will also yield 0° [45].

It is critical to note that while both meso compounds and racemic mixtures are optically inactive, they are fundamentally different. A meso compound is a single, pure achiral substance, while a racemic mixture is a 50:50 mixture of two chiral enantiomers [39] [45].

Physical Property Analysis

Beyond optical activity, meso compounds can be distinguished from their chiral diastereomers through their physical properties [41]. Since meso compounds and enantiomers are not mirror images, they are diastereomers of each other and thus have different physical properties.

Table 2: Comparative Physical Data for Tartaric Acid Stereoisomers [41]

| Stereoisomer | Specific Rotation [α] | Melting Point (°C) | Solubility (g/100 mL H₂O) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-(+)-Tartaric Acid | +12° | 170 | 139 |

| D-(-)-Tartaric Acid | -12° | 170 | 139 |

| Meso-Tartaric Acid | 0° | 146 | 125 |

This data demonstrates that while enantiomers share identical physical properties like melting point and solubility, the meso diastereomer has distinct characteristics, making it separable by standard techniques like crystallization [45].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Meso Compound Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Polarimeter | The primary instrument for determining optical activity by measuring the rotation of plane-polarized light [45]. |

| Achiral Solvents (e.g., Hexane, Acetone, Methanol) | Used to prepare samples for polarimetry and chromatography without introducing a chiral environment [45]. |

| Chiral Derivatizing Agents (e.g., MPA, MTPA) | Used to convert enantiomeric mixtures into diastereomers via chemical reaction, allowing for separation by NMR or achiral chromatography [45]. |

| Chiral Stationary Phase (HPLC/GC) | Used for the direct chromatographic separation of enantiomers, which is not required for a pure meso compound but is essential for analyzing mixtures containing meso and chiral forms [45]. |

Application in Pharmaceutical and Chemical Research

The implications of meso compounds in drug development are profound. Biological systems are chiral, and proteins, enzymes, and receptors interact differently with each enantiomer of a chiral drug [45]. A meso compound, being achiral, will not have enantiomer-specific biological activity. This can be a significant advantage, as it eliminates concerns about one enantiomer being therapeutically active while the other is inactive or toxic, a notorious example being the drug thalidomide [45].

Furthermore, the presence of a meso form affects the total number of possible stereoisomers for a given molecular structure. For a molecule with n chiral centers, the theoretical maximum number of stereoisomers is 2^n. However, if one of these is a meso compound, the actual number is 2^n - 1 [39]. This is critical for synthetic chemists planning stereoselective syntheses and calculating reaction yields, as the meso form can be a unique and predictable product, especially in symmetric reactions. For instance, hydrogenation of a symmetric diketone might produce a meso diol as a single stereoisomer, while an asymmetric counterpart would yield a pair of enantiomers requiring separation.

The thalidomide disaster represents a pivotal case study in medicinal chemistry, demonstrating the critical importance of stereochemistry in drug development and safety. This technical analysis examines the mechanistic underpinnings of thalidomide's teratogenicity through the lens of stereoisomerism, exploring how apparently subtle spatial arrangements of atoms confer dramatically different biological activities. We detail the molecular interactions between thalidomide enantiomers and their primary biological target, cereblon, and present quantitative data on the stereospecific binding affinities that underpin the drug's tragic teratogenic effects. Furthermore, we analyze the phenomenon of in vivo racemization and its implications for pharmaceutical development, providing experimental methodologies for investigating stereochemical properties of chiral therapeutics. This case continues to inform regulatory frameworks and drug design paradigms six decades after the initial tragedy, serving as an enduring lesson in molecular pharmacology.

Stereochemistry, the study of the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in molecules, represents a fundamental domain in organic chemistry and drug development with profound implications for biological activity [46]. Chirality, formally defined as the geometric property of a rigid object of not being superimposable on its mirror image, is ubiquitous throughout biological systems [3]. Chiral molecules exist as pairs of enantiomers - non-superimposable mirror images that share identical two-dimensional structural formulas but differ in their three-dimensional orientation [47].

In achiral environments, enantiomers exhibit identical physical and chemical properties. However, in biological systems - which are inherently chiral due to the homochirality of biomolecules such as L-amino acids and D-sugars - each enantiomer may display distinct pharmacological behavior [3]. This dichotomy arises from the precise structural complementarity required for molecular recognition at biological target sites; just as a left hand fits poorly into a right-handed glove, one enantiomer may bind effectively to a protein binding site while its mirror image may not [3].

The thalidomide molecule contains a single stereogenic center, making it capable of existing as two enantiomers: (R)-thalidomide and (S)-thalidomide [48]. Initially marketed as a racemic mixture (containing equal amounts of both enantiomers), the drug was prescribed as a sedative and antiemetic for morning sickness in pregnant women before its teratogenic properties were recognized [49]. The tragic consequences of this oversight would forever change pharmaceutical regulation and underscore the critical importance of stereochemical considerations in drug development.

Historical Context of the Thalidomide Disaster

Pharmaceutical Development and Initial Use