Traditional SAR vs. Modern High-Throughput Experimentation: A Comparative Analysis for Optimizing Drug Development

This article provides a comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolution from traditional Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) optimization to modern High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and AI-driven approaches.

Traditional SAR vs. Modern High-Throughput Experimentation: A Comparative Analysis for Optimizing Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the evolution from traditional Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) optimization to modern High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and AI-driven approaches. It explores the foundational principles of both paradigms, detailing their methodological applications in lead identification and optimization. The scope extends to troubleshooting common challenges, such as high clinical attrition rates due to efficacy and toxicity, and examines optimization strategies from lead candidate selection to clinical dose optimization. Finally, it offers a validation framework for comparing the success rates, cost efficiency, and future potential of these strategies in improving the productivity of biomedical research.

From Single Targets to Complex Systems: The Evolution of Drug Optimization Philosophy

In the pursuit of optimization within drug development and chemical research, two distinct methodological paradigms have emerged: the linear, sequential approach of Traditional Successive Approximation (SAR) and the highly parallel, multi-dimensional framework of High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE). The fundamental distinction between these paradigms lies in their core operational logic. Traditional SAR employs a linear, sequential process where each experiment is designed based on the outcome of the previous one, creating a deliberate but slow path toward optimization [1]. In contrast, HTE leverages parallelism, executing vast arrays of experiments simultaneously to explore a broad experimental space rapidly [2].

This article provides a comparative analysis of these two approaches, examining their underlying principles, methodological workflows, and applications in research and development. By understanding their respective strengths, limitations, and ideal use cases, researchers can make more informed decisions about which paradigm best suits their specific optimization challenges.

Understanding the Traditional SAR Paradigm

Core Principles and Sequential Workflow

The Traditional Successive Approximation (SAR) paradigm is rooted in a binary search algorithm, operating on a linear, stepwise principle. In this approach, each experiment is designed, executed, and analyzed before the next one is conceived. The outcome of each step directly informs the design of the subsequent experiment, creating a tightly coupled chain of experimental reasoning [1].

This methodology is characterized by its deliberate, sequential nature. Much like a binary search algorithm, it systematically narrows possibilities by testing hypotheses at the midpoints of progressively smaller ranges [1]. This process requires significant domain expertise and chemical intuition at each decision point, as researchers must interpret results and determine the most promising direction for the next experimental iteration.

The sequential workflow of Traditional SAR, while methodical, presents inherent limitations in exploration speed. Since each experiment depends on the completion and analysis of the previous one, the total timeline for optimization scales linearly with the number of experimental iterations required. This makes the approach thorough but time-consuming, particularly for complex optimization spaces with multiple interacting variables.

Application Contexts and Limitations

Traditional SAR finds its strongest application in targeted optimization problems where the experimental space is relatively well-understood and the number of critical variables is limited. It is particularly effective when resources are constrained or when experiments are expensive to conduct, as it minimizes wasted effort on unproductive directions through its deliberate, informed sequencing [1].

However, this approach struggles with high-dimensional problems where multiple variables interact in complex, non-linear ways. Its sequential nature makes it susceptible to local optima convergence, as the path-dependent exploration may fail to escape promising regions that are not globally optimal [2]. Additionally, the linear workflow provides limited capacity for discovering unexpected reactivity or synergistic effects between variables, as the experimental trajectory is guided by prior expectations and existing chemical intuition.

Understanding the HTE Parallelism Paradigm

Core Principles and Parallel Workflow

High-Throughput Experimentation represents a paradigm shift from sequential to parallel investigation. Instead of conducting experiments one after another, HTE employs massively parallel experimentation through miniaturized reaction scales and automated robotic systems [2]. This approach allows for the simultaneous execution of hundreds or thousands of experiments, systematically exploring multi-dimensional parameter spaces in a fraction of the time required by traditional methods.

The power of HTE parallelism lies in its comprehensive exploration capabilities. Where Traditional SAR follows a single experimental path, HTE maps broad landscapes of reactivity by testing numerous combinations of variables concurrently [3]. This is particularly valuable for understanding complex reactions like Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, where outcomes are sensitive to multiple interacting parameters including catalysts, ligands, solvents, and bases [3].

Modern HTE campaigns increasingly integrate machine learning frameworks like Minerva to guide experimental design. These systems use Bayesian optimization to balance exploration of unknown regions with exploitation of promising areas, efficiently navigating spaces of up to 88,000 possible reaction conditions [2]. This represents a significant evolution from earlier grid-based HTE designs toward more intelligent, adaptive parallel exploration.

Application Contexts and Strengths

HTE parallelism excels in complex optimization challenges with high-dimensional parameter spaces, particularly in pharmaceutical process development where multiple objectives must be balanced simultaneously [2]. It has demonstrated remarkable success in optimizing challenging transformations such as nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reactions and Buchwald-Hartwig aminations, where traditional methods often struggle to identify productive conditions [2].

The methodology is particularly valuable for discovering unexpected reactivity and non-linear synergistic effects that would be unlikely found through sequential approaches. By comprehensively sampling the experimental space, HTE can reveal hidden structure-activity relationships and identify optimal conditions that defy conventional chemical intuition [3]. Additionally, the rich, multi-dimensional datasets generated by HTE campaigns provide valuable insights that extend beyond immediate optimization goals, contributing to broader chemical knowledge and reactome understanding [3].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences and Experimental Data

Direct Paradigm Comparison

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between the Traditional SAR and HTE parallelism approaches:

| Feature | Traditional SAR | HTE Parallelism |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Sequential binary search algorithm [1] | Parallel multi-dimensional mapping [2] |

| Workflow Structure | Linear, dependent sequence | Simultaneous, independent experiments |

| Experimental Throughput | Low (1 to few experiments per cycle) | High (96 to 1000+ experiments per cycle) [2] |

| Information Generation | Incremental, path-dependent | Comprehensive, landscape mapping |

| Optimal Application Space | Well-constrained, low-dimensional problems | Complex, high-dimensional optimization [2] |

| Resource Requirements | Lower equipment cost, higher time investment | High equipment cost, reduced time investment |

| Discovery Potential | Limited to anticipated reaction spaces | High potential for unexpected discoveries [3] |

Performance Comparison in Pharmaceutical Optimization

Recent studies directly comparing these approaches in pharmaceutical process development demonstrate their relative performance characteristics:

| Optimization Metric | Traditional SAR | HTE Parallelism |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Optimization | 6+ months for complex reactions [2] | 4 weeks for comparable systems [2] |

| Success Rate (Challenging Reactions) | Low (failed to find conditions for Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction) [2] | High (76% yield, 92% selectivity for same reaction) [2] |

| Parameter Space Exploration | Limited (guided by chemical intuition) | Comprehensive (88,000 condition space) [2] |

| Multi-objective Optimization | Sequential priority balancing | Simultaneous yield, selectivity, and cost optimization [2] |

| Data Generation for ML | Sparse, sequential data points | Rich, structured datasets for model training [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional SAR Experimental Protocol

The Traditional SAR approach follows a well-defined sequential methodology for reaction optimization:

Initial Condition Selection: Based on chemical intuition and literature precedent, select a starting point for reaction parameters (catalyst, solvent, temperature) [1].

Baseline Establishment: Execute the reaction at chosen conditions and analyze outcomes (yield, selectivity, conversion) using appropriate analytical methods [1].

Sequential Parameter Variation:

- Identify the parameter deemed most influential on reaction outcome

- Systematically vary this parameter while holding others constant

- Execute experiments sequentially, with each condition chosen based on previous results [1]

Iterative Refinement:

- Analyze results to determine optimal value for the first parameter

- Select the next most influential parameter to vary

- Repeat the sequential variation process [1]

Convergence Testing: Continue iterative refinement until additional parameter adjustments no longer produce significant improvements in reaction outcomes [1].

This methodology mirrors the binary search algorithm used in SAR analog-to-digital converters, where each comparison halves the possible solution space, progressively converging toward an optimum [1].

HTE Parallelism Experimental Protocol

HTE parallelism employs a distinctly different approach focused on simultaneous experimentation:

Reaction Parameter Selection: Identify critical reaction variables (catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, additives, temperatures) and define plausible ranges for each [2].

Experimental Design:

- Create a diverse set of reaction conditions spanning the parameter space

- Utilize algorithmic sampling (e.g., Sobol sampling) to maximize space coverage

- Design 96-well or 384-well plates with varied condition combinations [2]

Parallel Execution:

- Use automated liquid handling systems to prepare reaction mixtures

- Execute all reactions simultaneously under controlled conditions

- Quench and work up reactions in parallel [2]

High-Throughput Analysis:

- Employ automated analytical systems (UPLC, HPLC, GC) for rapid analysis

- Utilize plate readers for colorimetric or fluorescence-based assays [4]

Data Integration and Machine Learning:

Iterative Campaign Design:

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The experimental paradigms require different reagent and material approaches, reflected in the following research toolkit:

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Traditional SAR | Function in HTE Parallelism |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Libraries | Individual catalysts tested sequentially | Diverse catalyst sets (Pd, Ni, Cu) screened in parallel [3] [2] |

| Solvent Systems | Limited, commonly used solvents | Broad solvent diversity including unconventional options [2] |

| Ligand Sets | Selected based on mechanism hypothesis | Comprehensive ligand libraries for mapping structure-activity relationships [3] |

| Analytical Standards | External standards for quantitative analysis | Internal standards and calibration curves for high-throughput quantification [4] |

| Base/Additive Arrays | Limited selection varied one-at-a-time | Diverse bases and additives screened for synergistic effects [3] |

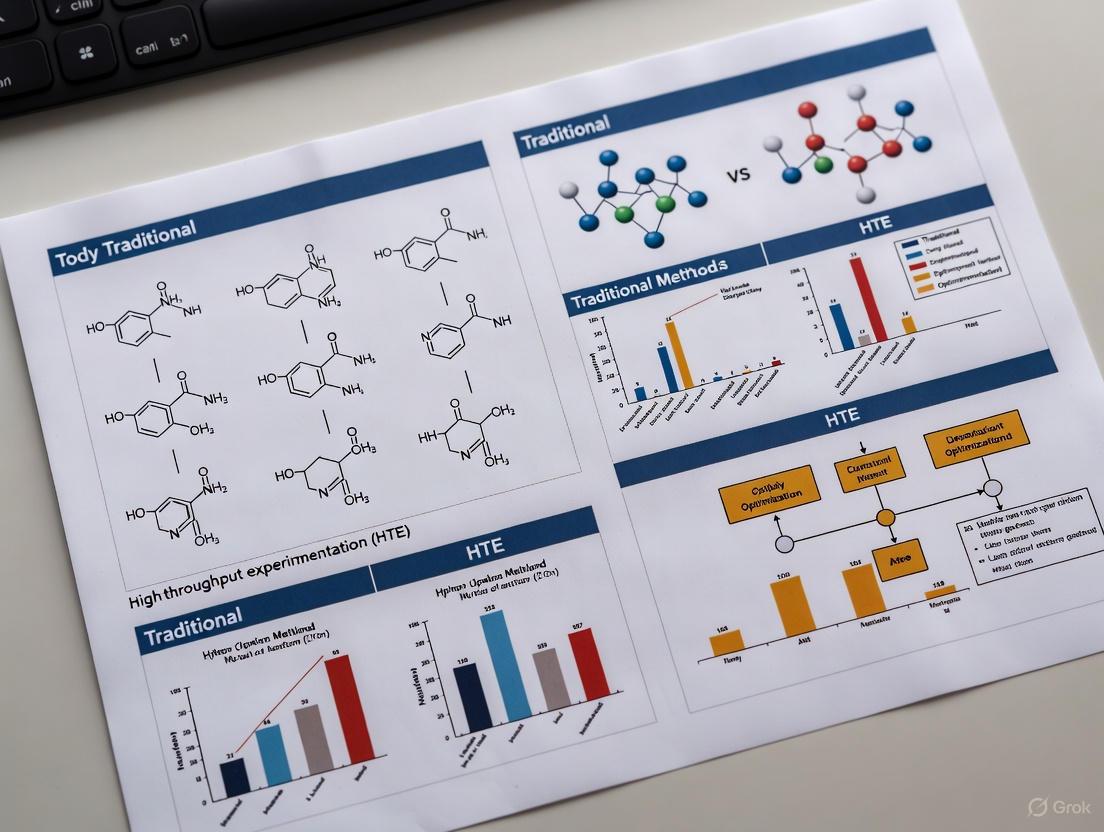

Workflow Visualization

Traditional SAR Sequential Workflow

HTE Parallelism Workflow

The choice between Traditional SAR and HTE parallelism represents a fundamental strategic decision in optimization research. Traditional SAR offers a focused, resource-efficient approach for problems with constrained parameter spaces and established reaction paradigms. Its sequential nature provides deep mechanistic insights through careful, iterative experimentation but risks convergence on local optima in complex landscapes.

HTE parallelism delivers unparalleled exploratory power for high-dimensional optimization challenges, particularly in pharmaceutical development where multiple objectives must be balanced. The ability to rapidly map complex reaction landscapes and discover non-obvious synergistic effects makes it invaluable for tackling the most challenging optimization problems in modern chemistry [2].

Rather than viewing these approaches as mutually exclusive, research organizations benefit from maintaining both capabilities, deploying each according to problem characteristics. Traditional SAR remains effective for straightforward parameter optimization and resource-constrained environments, while HTE parallelism excels when comprehensive landscape mapping and discovery of unexpected reactivity are required. The integration of machine learning with HTE represents the evolving frontier of optimization science, creating a powerful synergy between human chemical intuition and algorithmic search capabilities [2].

For decades, drug discovery has been predominantly guided by the "Single Target, Single Disease" model, a paradigm that revolves around identifying a single molecular target critically involved in a disease pathway and developing a highly selective drug to modulate it. [5] [6] This approach, often termed the "one disease–one target–one drug" dogma, has been successful for some conditions, particularly monogenic diseases or those with a clear, singular pathological cause. [6] The development of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for arthritis is a classic example of its successful application. [6]

However, clinical data increasingly reveal that this model is inefficient for multifactorial conditions. [5] [6] Complex diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, cancer, and diabetes involve intricate signaling networks rather than a single defective protein. [5] [6] [7] The over-reliance on the single-target paradigm has become a significant obstacle, contributing to high attrition rates, with many compounds failing in late-stage clinical development due to insufficient therapeutic effect, adverse side effects, or the emergence of drug resistance. [6] [7] This article examines the historical context and fundamental limitations of this model, framing it within a comparative analysis of traditional and modern High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) optimization research.

Core Limitations of the Single-Target Model

The limitations of the "Single Target, Single Disease" model stem from its reductionist nature, which often fails to account for the complex, networked physiology of human diseases. The core shortcomings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Limitations of the 'Single Target, Single Disease' Paradigm

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Therapeutic Efficacy [6] [7] | Inability to interfere with the complete disease network; activation of bypass biological pathways. [7] | Poor efficacy, especially in complex, multifactorial diseases. [6] |

| Development of Drug Resistance [5] [7] | Selective pressure on a single target leads to mutations; the body develops self-resistance. [7] | Loss of drug effectiveness over time, common in oncology and infectious diseases. [5] |

| Off-Target Toxicity & Adverse Effects [6] [7] | High selectivity for one target does not preclude unintended interactions with other proteins or pathways. [7] | Side effects and toxicity that limit dosing and clinical utility. [6] |

| Poor Translation to Clinics [6] | Lack of physiological relevance in target-based assays; oversimplification of disease biology. [6] | High late-stage failure rates despite promising preclinical data. [6] |

| Inefficiency in Treating Comorbidities [7] | Inability to address multiple symptoms or disease pathways simultaneously. [7] | Difficulty in managing patients with complex, overlapping conditions. [7] |

The Network Nature of Disease

The fundamental problem is that diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders, cancers, and metabolic syndromes, are not caused by a single protein but by dysregulated signaling networks. [6] As noted in a 2025 review, "when a single target drug interferes with the target or inhibits the downstream pathway, the body produces self-resistance, activates the bypass biological pathway, [leading to] the mutation of the therapeutic target." [7] This network effect explains why highly selective drugs often fail to achieve the desired clinical outcome; the disease network simply rewires around the single blocked node.

The Resistance and Toxicity Challenge

Drug resistance is a direct consequence of this model. In cancer, for example, inhibiting a single oncogenic kinase often leads to the selection of resistant clones or the activation of alternative survival pathways. [5] Furthermore, the pursuit of extreme selectivity does not automatically guarantee safety. Off-target effects remain a significant problem, as a drug can still interact with unforeseen proteins, "bring corresponding toxicity when bringing the expected efficacy." [7]

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. HTE Optimization Research

The evolution beyond the single-target paradigm has been driven by new research approaches that leverage scale, automation, and computational power. The table below contrasts the core methodologies.

Table 2: Paradigm Comparison: Traditional Target-Based vs. Modern HTE Optimization Research

| Aspect | Traditional Target-Based Research | HTE Optimization Research |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | "One disease–one target–one drug"; Reductionist. [6] | Multi-target, network-based; Systems biology. [6] |

| Screening Approach | Target-based screening (biochemical assays on purified proteins). [8] | Phenotypic screening (cell-based, organoids); Virtual screening (AI/ML). [6] [8] [9] |

| Throughput & Scale | Lower throughput, often manual or semi-automated. [8] | Ultra-high-throughput, miniaturized, and fully automated (e.g., 1536-well plates). [8] |

| Hit Identification | Based on affinity for a single, pre-specified target. [9] | Based on complex phenotypic readouts or multi-parameter AI analysis. [6] [10] |

| Data Output | Single-parameter data (e.g., IC50, Ki). [9] | Multi-parametric, high-content data (e.g., cell morphology, multi-omics). [6] [8] |

| Lead Optimization | Linear, slow Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycles. [10] | Rapid, integrated AI-driven DMTA cycles; can compress timelines from months to weeks. [10] |

The Rise of Phenotypic Screening and Multi-Target Strategies

A significant shift has been the renaissance of Phenotypic Drug Discovery (PDD). [6] Unlike target-based screening, PDD identifies compounds based on their ability to modify a disease-relevant phenotype in cells or tissues, without prior knowledge of a specific molecular target. [6] This approach is agnostic to the underlying complexity and is particularly advantageous for identifying first-in-class drugs or molecules that engage multiple targets simultaneously, making it a powerful tool for multi-target drug discovery. [6]

This aligns with the strategy of developing multi-target drugs or "designed multiple ligands," which aim to modulate several key nodes in a disease network concurrently. [5] [6] This approach, characterized by "multi-target, low affinity and low selectivity," can improve efficacy and reduce the likelihood of resistance by restoring the overall balance of the diseased network. [7] The antipsychotic drug olanzapine, which exhibits nanomolar affinities for over a dozen different receptors, is a successful example of a multi-targeted drug that succeeded where highly selective candidates failed. [6]

The Role of AI and Automation

Modern HTE is deeply integrated with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning. [10] [8] AI algorithms are used to analyze the massive, complex datasets generated by high-throughput screens, uncovering patterns that are invisible to traditional analysis. [8] Furthermore, AI is now being used for generative chemistry, where it designs novel molecular structures that satisfy multi-parameter optimization goals, including potency against multiple targets, selectivity, and optimal pharmacokinetic properties. [11] For instance, companies like Exscientia have reported AI-driven design cycles that are ~70% faster and require 10-fold fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms. [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

The transition to modern, network-driven drug discovery relies on a new set of tools and reagents that enable complex, high-throughput experimentation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Modern Drug Discovery

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application in Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-Derived Cells [6] | Physiologically relevant human cell models that reproduce disease mechanisms. | Provides human-relevant, predictive models for phenotypic screening and toxicity assessment, reducing reliance on non-translational animal models. [6] |

| 3D Organoids & Cocultures [6] | Advanced in vitro models that mimic cell-cell interactions and tissue-level complexity. | Used to model neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and other complex phenotypes in a more physiologically relevant context. [6] |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [10] | Validates direct drug-target engagement in intact cells and native tissue environments. | Bridges the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy; provides decisive evidence of mechanistic function within a complex biological system. [10] |

| Label-Free Technologies (e.g., SPR) [8] | Monitor molecular interactions in real-time without fluorescent or radioactive tags. | Provides high-quality data on binding affinity and kinetics for hit validation and optimization in screening campaigns. [8] |

| AI/ML Drug Discovery Platforms [11] | Generative AI and machine learning for target ID, compound design, and property prediction. | Accelerates discovery timelines and enables the rational design of multi-target drugs. For example, an AI-designed CDK7 inhibitor reached candidate stage after synthesizing only 136 compounds. [11] |

| High-Content Screening (HCS) [7] | Cell phenotype screening combining automatic fluorescence microscopy with automated image analysis. | Enables simultaneous detection of multiple phenotypic parameters (morphology, intracellular targets) in a single assay, ideal for complex drug studies. [7] |

Visualizing the Paradigm Shift

The following diagrams illustrate the core conceptual and methodological differences between the traditional and modern drug discovery paradigms.

The Traditional Single-Target Model

Linear Single-Target Pathway

The Modern Network-Based Model

Network-Based Multi-Target Therapy

The "Single Target, Single Disease" model, while historically productive, possesses inherent limitations in tackling the complex, networked nature of most major human diseases. Its insufficiency in delivering effective therapies for conditions like neurodegenerative disorders and complex cancers has driven a paradigm shift. The future of drug discovery lies in approaches that embrace biological complexity: multi-target strategies, phenotypic screening in human-relevant models, and the power of AI and HTE to navigate this complexity. This transition from a reductionist to a systems-level view is essential for increasing the success rate of drug development and delivering better therapies to patients.

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has fundamentally reengineered the drug discovery landscape, transforming it from a painstaking, sequential process into a parallelized, data-rich science. This systematic approach allows researchers to rapidly conduct thousands to millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests using automated robotics, data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors [12]. The traditional drug discovery process historically consumed 12-15 years and cost over $1 billion to bring a new drug to market [13]. HTE, particularly through its implementation in High-Throughput Screening (HTS), has dramatically compressed the early discovery timeline by enabling the screening of vast compound libraries containing hundreds of thousands of drug candidates at rates exceeding 100,000 compounds per day [14] [13]. This acceleration is not merely about speed; it represents a fundamental shift in how researchers identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways, providing superior starting points for drug design and understanding complex biological interactions [12].

Table 1: Core Capability Comparison: Traditional Methods vs. Modern HTE

| Aspect | Traditional Screening | Modern HTE/HTS |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | Dozens to hundreds of compounds per week [13] | Up to 100,000+ compounds per day [14] [13] |

| Typical Assay Volume | Milliliter scale | Microliter to nanoliter scale (2.5-10 µL) [14] |

| Automation Level | Manual or semi-automated | Fully automated, integrated robotic systems [12] |

| Data Output | Low, manually processed | High-volume, automated data acquisition and processing [12] |

| Primary Goal | Target identification and initial validation | Rapid identification of "hit" compounds and comprehensive SAR [15] [16] |

The HTE Toolbox: Core Technologies and Methodologies

The power of HTE stems from the integration of several core technologies that work in concert to create a seamless, automated pipeline. Understanding these components is essential to appreciating its revolutionary impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in a Typical HTE Workflow

| Tool/Reagent | Function in HTE | Specific Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | The core labware for running parallel assays. | 96-, 384-, 1536-, or 3456-well plates; chosen based on assay nature and detection method [14] [12]. |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of molecules screened for biological activity. | Libraries of chemical compounds, siRNAs, or natural products; carefully catalogued in stock plates [12]. |

| Assay Reagents | Biological components used to measure compound interaction. | Includes enzymes (e.g., tyrosine kinase), cell lines, antibodies, and fluorescent dyes for detection [15] [14]. |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Automated devices for precise reagent transfer. | Robotic pipettors that transfer nanoliter volumes from stock plates to assay plates, ensuring accuracy and reproducibility [12]. |

| Detection Reagents | Chemicals that generate a measurable signal upon biological activity. | Fluorescent dyes (e.g., for cell viability, apoptosis), luminescent substrates, and FRET/HTRF reagents [15] [14]. |

| Automated Robotics | Integrated systems that transport and process microplates. | Robotic arms that move plates between stations for addition, mixing, incubation, and reading [13] [12]. |

Standardized Experimental Workflow and Protocol

A typical HTE screening campaign follows a rigorous, multi-stage protocol designed to efficiently sift through large compound libraries and validate true "hits." The workflow below outlines the key stages from initial setup to confirmed hits.

Diagram 1: HTE Screening Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

Target Identification and Reagent Preparation: The process begins with the identification and validation of a specific biological target (e.g., a protein, enzyme, or cellular pathway). Reagents, including the target and test compounds, are optimized and prepared for automation. Contamination must be avoided, and reagents like aptamers are often used for their high affinity and compatibility with detection strategies [14].

Assay Plate Preparation: Compound libraries, stored as stock plates, are used to create assay plates via liquid handling systems. A small volume (often nanoliters) of each compound is transferred into the wells of a microtiter plate (96- to 3456-well formats) [12]. The wells are then filled with the biological entity (e.g., proteins, cells, or enzymes) for testing [12].

Automated Reaction and Incubation: An integrated robotic system transports the assay plates through various stations for reagent addition, mixing, and incubation. The system can handle many plates simultaneously, managing the entire process from start to finish under controlled conditions [13] [12].

High-Throughput Detection: After incubation, measurements are taken across all wells. This is typically done using optical measurements, such as fluorescence, luminescence, or light scatter (e.g., using NanoBRET or FRET) [13] [12]. Specialized automated analysis machines can measure dozens of plates in minutes, generating thousands of data points [12].

Primary Data Analysis and Hit Selection: Automated software processes the raw data. Quality control (QC) metrics like the Z-factor are used to assess assay quality [12] [17]. Compounds that show a desired level of activity, known as "hits," are identified using statistical methods such as z-score or SSMD, which help manage the high false-positive rate common in primary screens [17] [12].

Confirmatory Screening: Initial "hits" are "cherry-picked" and tested in follow-up assays to confirm activity. This hierarchical validation is crucial and often involves testing compounds in concentration-response curves to determine potency (IC50/EC50) and in counter-screens to rule out non-specific activity [17] [12].

Hit Validation and Progression: Confirmed hits undergo further biological validation to understand their mechanism of action and selectivity. Techniques like High-Content Screening (HCS), which uses automated microscopy and image analysis to measure multiple cellular parameters, are invaluable here for providing a deeper understanding of cellular responses [15].

Quantitative Performance: HTE vs. Traditional Screening

The superiority of HTE is unequivocally demonstrated when comparing its quantitative output and efficiency against traditional methods. The data below highlights the transformative gains in throughput, resource utilization, and cost-effectiveness.

Table 3: Performance Metrics: Traditional vs. HTE Screening

| Performance Metric | Traditional Screening | HTE Screening | Advantage Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Daily Throughput | ~100 compounds [13] | ~100,000 compounds [14] [13] | 1,000x |

| Typical Assay Volume | 1-10 mL | 1-10 µL [14] | 1,000x less reagent use |

| Typical Project Duration | 1-2 years (for 3000 compounds) [16] | 3-4 weeks (for 3000 compounds) [16] | ~10x faster |

| Data Points per Experiment | Limited by manual capacity | Millions of tests [12] | Several orders of magnitude |

| Key Analytical Outputs | Basic activity assessment | Full concentration-response (EC50, IC50), SAR [12] | Rich, quantitative pharmacological profiling |

The Evolving HTE Landscape: Integration of Enabling Technologies

The capabilities of HTE are continually being augmented by integration with other cutting-edge technologies. This synergy is pushing the boundaries of what is possible in drug discovery.

Convergence with AI and Machine Learning

The large, high-quality datasets generated by HTE are ideal fuel for artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms. This combination creates a powerful feedback loop: HTE provides the robust data needed to train predictive models, which in turn can propose new compounds or optimize reaction conditions for subsequent HTE cycles, significantly accelerating the discovery process [18]. This integration is proving to be a "game-changer," enhancing the efficiency, precision, and innovative capacity of research [18].

Adoption of Flow Chemistry

Flow chemistry is emerging as a powerful complement to traditional plate-based HTE. It addresses several limitations of plate-based systems, particularly for chemical reactions. Flow chemistry allows for superior control over continuous variables like temperature, pressure, and reaction time, and enables facile scale-up from screening to production without re-optimization [16]. It also provides safer handling of hazardous reagents and is particularly beneficial for photochemical and electrochemical reactions, opening new avenues for HTE in synthetic chemistry [16].

The Rise of High-Content Screening (HCS)

While HTS excels at speed and volume, High-Content Screening (HCS) provides a more detailed, multi-parameter analysis. Also known as High-Content Analysis (HCA), HCS uses automated fluorescence microscopy and image analysis to quantify complex cellular phenotypes—such as cell morphology, protein localization, and organelle health—in response to compounds [15]. This provides deep insights into a compound's mechanism of action and potential off-target effects, making it invaluable for secondary screening and lead optimization [15]. The relationship between these core screening technologies is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Synergy of Screening Technologies

The rise of High-Throughput Experimentation is a definitive driver for change in modern drug discovery. The transition from low-throughput, manual processes to automated, data-dense workflows has created a paradigm shift, compressing discovery timelines and enriching the quality of lead compounds. The integration of HTE with other transformative technologies like AI, flow chemistry, and High-Content Screening creates a synergistic ecosystem that is more powerful than the sum of its parts. As these technologies continue to evolve and converge, they promise to further de-risk the drug development process and accelerate the delivery of novel therapeutics to patients, solidifying HTE's role as an indispensable pillar of 21st-century biomedical research.

Core Principles of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) and Lead Optimization

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) analysis represents a fundamental pillar of modern drug discovery, providing the critical scientific link between a molecule's chemical structure and its biological activity [19]. The core premise of SAR is that specific arrangements of atoms and functional groups within a molecule dictate its properties and interactions with biological systems [20]. By systematically exploring how modifications to a molecule's structure affect its biological activity, researchers can identify key structural features that influence potency, selectivity, and safety, enabling progression from initial hits to well-optimized lead compounds [20]. This process is intrinsically linked to lead optimization, the comprehensive phase of drug discovery that focuses on refining different characteristics of lead compounds, including target selectivity, biological activity, potency, and toxicity potential [21]. Within the broader context of comparative studies between traditional and high-throughput experimentation (HTE) optimization research, understanding the fundamental principles and methodologies of SAR becomes essential for evaluating the relative strengths, applications, and limitations of each approach in advancing therapeutic candidates.

Core Principles of Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

Fundamental Concepts and Historical Foundation

The conceptual foundation of SAR was first established by Alexander Crum Brown and Thomas Richard Fraser, who in 1868 formally proposed a connection between chemical constitution and physiological action [19]. The basic assumption underlying all molecule-based hypotheses is that similar molecules have similar activities [22]. This principle, however, is tempered by the SAR paradox, which acknowledges that it is not universally true that all similar molecules have similar activities [22]. This paradox highlights the complexity of biological systems and the fact that different types of activity (e.g., reaction ability, biotransformation ability, solubility, target activity) may depend on different molecular differences [22].

The essential components considered in SAR analysis include:

- Size and shape of the carbon skeleton and overall spatial arrangement

- Functional groups that participate in key interactions (hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, hydrophobic interactions)

- Stereochemistry or three-dimensional arrangement of atoms

- Nature and position of substituents on a parent scaffold

- Physicochemical properties including solubility, lipophilicity, pKa, polarity, and molecular flexibility [20]

The SAR Study Workflow

SAR studies typically follow a systematic, iterative workflow often described as the Design – Make – Test – Analyze cycle [20]:

- Design: Based on existing data and structural information, propose structural analogs with specific modifications.

- Make: Synthesize the planned series of compounds (analogs), each with deliberate structural variations from a known active compound.

- Test: Measure the biological activity of each analog using relevant assays (e.g., enzyme inhibition, receptor binding, cellular effects).

- Analyze: Correlate the results to identify which structural features associate with increased, decreased, or altered activity, thus pinpointing the pharmacophore—the essential molecular features responsible for biological activity [20].

This workflow enables medicinal chemists to navigate vast chemical space systematically, making informed structural modifications to achieve desired biological outcomes [20].

SAR and QSAR: From Qualitative to Quantitative Analysis

While SAR provides qualitative relationships between structure and activity, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling extends this concept by building mathematical models that relate a set of "predictor" variables (X) to the potency of a response variable (Y) [22]. QSAR models are regression or classification models that use physicochemical properties or theoretical molecular descriptors of chemicals to predict biological activities [22]. The general form of a QSAR model is: Activity = f(physicochemical properties and/or structural properties) + error [22].

Types of QSAR Approaches

Multiple QSAR methodologies have been developed, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of QSAR Modeling Approaches

| QSAR Type | Core Principle | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragment-Based (GQSAR) [22] | Uses contributions of molecular fragments/substituents. | Studies various molecular fragments; Considers cross-term fragment interactions. | Fragment library design; Fragment-to-lead identification. |

| 3D-QSAR [22] | Applies force field calculations to 3D structures. | Requires molecular alignment; Analyzes steric and electrostatic fields. | Understanding detailed ligand-receptor interactions when structure is available. |

| Chemical Descriptor-Based [22] | Uses computed electronic, geometric, or steric descriptors for the whole molecule. | Descriptors are scalar quantities computed for the entire system. | Broad QSAR applications, especially when 3D structure is uncertain. |

| q-RASAR [22] | Merges QSAR with similarity-based read-across. | Hybrid method; Integrates with ARKA descriptors. | Leveraging combined predictive power of different modeling paradigms. |

QSAR Model Development and Validation

The principal steps of QSAR studies include: (1) selection of data set and extraction of structural/empirical descriptors, (2) variable selection, (3) model construction, and (4) validation evaluation [22]. Validation is particularly critical for establishing the reliability and relevance of QSAR models and must address robustness, predictive performance, and the applicability domain (AD) of the models [22] [23]. The domain of applicability defines the scope and limitations of a model, indicating when predictions can be considered reliable [23]. Validation strategies include internal validation (cross-validation), external validation by splitting data into training and prediction sets, blind external validation, and data randomization (Y-scrambling) to verify the absence of chance correlations [22].

Lead Optimization: Strategies and Methodologies

Lead optimization is the final phase of drug discovery that aims to enhance the efficacy, safety, and pharmacological properties of lead compounds to develop effective drug candidates [21]. This stage extensively evaluates the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties of compounds, often using animal models to analyze effectiveness in modulating disease [21].

Key Lead Optimization Strategies

Table 2: Lead Optimization Strategies in Drug Discovery

| Strategy | Core Approach | Key Techniques | Primary Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Chemical Manipulation [21] | Modifying the natural structure of lead compounds. | Adding/swapping functional groups; Isosteric replacements; Adjusting ring systems. | Initial improvement of binding, potency, or stability. |

| SAR-Directed Optimization [21] | Systematic modifications guided by established SAR. | Analyzing biological data from structural changes; Focus on ADMET challenges. | Improving efficacy and safety without altering core structure. |

| Pharmacophore-Oriented Design [21] | Significant modification of the core structure. | Structure-based design; Scaffold hopping. | Addressing chemical accessibility; Creating novel leads with distinct properties. |

A critical aspect of modern lead optimization involves the use of ligand efficiency (LE) metrics, which normalize experimental activity to molecular size (e.g., LE ≥ 0.3 kcal/mol/heavy atom) [9]. This is particularly important because the aim of virtual screening and lead optimization is usually to provide a novel chemical scaffold for further optimization, and hits with sub-micromolar activity, while desirable, are not typically necessary [9]. Most optimization efforts begin with hits in the low to mid-micromolar range [9].

Computational Approaches in Lead Optimization

Computational methods play an increasingly vital role in lead optimization, improving both efficacy and efficiency [21]. Specific computational techniques include:

- Molecular docking and dynamics simulations: Investigate how compounds interact with biological targets at a molecular level [20]. For example, molecular dynamics simulations using tools like NAMD can explore the dynamic behavior and stability of ligand-protein complexes [20].

- Free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations: Used in conjunction with Monte Carlo statistical mechanics simulations for protein-inhibitor complexes in aqueous solution to provide rigorous binding free energy estimates [24].

- 3D-QSAR methods: Such as comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) and comparative molecular similarity indices analysis (CoMSIA) [21].

- De novo design: Using programs like BOMB (Biochemical and Organic Model Builder) to grow molecules by adding layers of substituents to a core placed in a binding site [24].

- Virtual screening: Docking of available compound collections to identify promising candidates for purchase and assaying [24].

These computational approaches allow researchers to predict activities for new molecules, prioritize large screening decks, and generate new compounds de novo [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Experimental SAR Protocols

Experimental SAR studies involve the synthesis and testing of a series of structurally related compounds [20]. Key experimental techniques include:

- Biological assays: Measure compound activity on a specific target (enzyme, receptor, cell) [20]. In early SAR, percentage inhibition at a given concentration is widely used, while concentration-response endpoints (IC₅₀, EC₅₀, Kᵢ, or K_d) provide more quantitative data [9].

- Pharmacokinetic studies: Measure absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of compounds [20].

- Toxicological studies: Assess compound safety by measuring effects on various organs and systems [20]. This includes tests like Irwin's test for general safety screening and the Ames test for genotoxicity [21].

Computational SAR Protocols

Computational SAR methods utilize machine learning and other modeling approaches to predict biological activity based on chemical structure [20]. Standard protocols include:

- Descriptor calculation: Quantifying structural and physicochemical properties of molecules [22] [20].

- Model construction: Using statistical methods (e.g., regression analysis, machine learning like support vector machines or random forests) to build predictive equations [22] [23].

- Model validation: Applying rigorous validation procedures including external validation and applicability domain assessment [22] [23].

- Activity prediction: Using validated models to predict activities of new compounds or virtual libraries [23].

Advanced protocols may include scans for possible additions of small substituents to a molecular core, interchange of heterocycles, and focused optimization of substituents at one site [24].

Visualization of SAR and Lead Optimization Workflows

SAR Analysis Workflow

SAR Analysis Workflow

Integrated Lead Optimization Strategy

Lead Optimization Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for SAR and Lead Optimization

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SAR/Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software [24] [20] | Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), BOMB, Glide, KNIME, NAMD | Enables molecular modeling, QSAR, docking, dynamics simulations, and workflow automation. |

| Compound Libraries [9] [24] | ZINC database, Maybridge, Commercial catalogs | Sources of compounds for virtual screening and experimental testing to expand SAR. |

| Assay Technologies [21] | High-Throughput Screening (HTS), Ultra-HTS, Fluorescence-based assays | Measures biological activity of compounds in automated, miniaturized formats. |

| Analytical Instruments [21] | NMR, LCMS, Crystallography | Characterizes molecular structure, identifies metabolites, studies ligand-protein interactions. |

| Descriptor Packages [22] | QikProp, Various molecular descriptor calculators | Computes physicochemical properties and molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling. |

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. HTE Optimization Research

Traditional SAR approaches often focus on sequential, hypothesis-driven testing of a limited number of compounds, with heavy reliance on medicinal chemistry intuition and experience [23]. In contrast, High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) leverages automation and miniaturization to rapidly test thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds [21]. Key comparative aspects include:

- Throughput: Traditional methods handle smaller compound sets; HTE can analyze >100,000 assays per day using UHTS [21].

- Data Generation: HTE produces massive datasets that require computational methods for interpretation and SAR analysis [23] [21].

- Resource Requirements: HTE reduces human resource needs through automation but requires significant upfront investment [21].

- Hit Identification: Virtual screening, often used with HTE, typically tests a smaller fraction of higher-scoring compounds compared to traditional HTS [9].

- Success Rates: Despite technological advances, lead optimization remains challenging, with only approximately one in ten optimized lead compounds ultimately reaching the market [21].

The integration of both approaches—using HTE for broad exploration and traditional methods for focused optimization—represents the current state-of-the-art in drug discovery. This hybrid strategy allows researchers to leverage the strengths of both methodologies while mitigating their respective limitations.

Core Principles of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and High-Content Screening (HCS)

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the shift from traditional, targeted research to High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) has fundamentally accelerated the identification of novel therapeutic candidates. Within this paradigm, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and High-Content Screening (HCS) serve as complementary pillars. HTS is designed for the rapid testing of thousands to millions of compounds against a biological target to identify active "hits" [15] [25]. In contrast, HCS provides a multiparameter, in-depth analysis of cellular responses by combining automated microscopy with quantitative image analysis, yielding rich mechanistic data on how these hits affect cellular systems [15] [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their core principles, applications, and performance, framing them within the broader thesis of traditional versus HTE optimization research.

Core Principles and Direct Comparison

The fundamental difference lies in the depth versus breadth of analysis. HTS prioritizes speed and scale for initial hit identification, while HCS sacrifices some throughput to gain profound insights into phenotypic changes and mechanisms of action [15] [26].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of HTS and HCS

| Feature | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | High-Content Screening (HCS) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Rapid identification of active compounds ("hits") from vast libraries [15] [25] | Multiparameter analysis of cellular morphology and function [15] [26] |

| Typical Readout | Single-parameter (e.g., enzyme activity, receptor binding) [15] | Multiparameter, image-based (e.g., cell size, morphology, protein localization) [15] [26] |

| Throughput | Very high (10,000 - 100,000+ compounds per day) [25] | High, but typically lower than HTS due to complex analysis [15] |

| Data Output | Quantitative data on compound activity [27] | Quantitative phenotypic fingerprints from high-dimensional datasets [28] [26] |

| Key Advantage | Speed and efficiency in screening large libraries [27] | Provides deep biological insight and mechanistic context [15] [28] |

| Common Assay Types | Biochemical (e.g., enzymatic) and cell-based [25] | Cell-based phenotypic assays [15] [26] |

| Information on Mechanism of Action | Limited, requires follow-up assays [15] | High, can infer mechanism from phenotypic profile [28] [26] |

The following diagram illustrates the core HTS workflow, from library preparation to hit identification:

The HCS workflow is more complex, involving image acquisition and analysis to extract multi-parameter data:

Quantitative Data and Market Context

The growing adoption of these technologies is reflected in market data. The global HTS market, valued at approximately $28.8 billion in 2024, is projected to advance at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 10.5% to 11.8%, reaching up to $50.2 billion by 2029 [27] [29]. This growth is propelled by the rising demand for faster drug development, the prevalence of chronic diseases, and advancements in automation and artificial intelligence (AI) [27] [30].

Table 2: Quantitative Market and Performance Data

| Parameter | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | High-Content Screening (HCS) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024) | $28.8 billion | (Part of HTS market) | [27] |

| Projected Market (2029) | $39.2 - $50.2 billion | (Part of HTS market) | [27] [29] |

| Projected CAGR | 10.5% - 11.8% | (Part of HTS market) | [27] [29] |

| Typical Throughput | 10,000 - 100,000 compounds/day; uHTS: >300,000 compounds/day [25] | Lower than HTS, varies by assay complexity | [15] [25] |

| Standard Assay Formats | 96-, 384-, 1536-well microplates [25] | 96-, 384-well microplates [15] | [15] [25] |

| Key Growth Catalysts | AI/ML integration, 3D cell cultures, lab-on-a-chip [27] [30] | AI-powered image analysis, 3D organoids, complex disease modeling [15] [26] | [15] [27] [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for a Biochemical HTS Assay

This protocol outlines a typical enzymatic HTS, such as screening for histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors [25].

- Assay Design and Miniaturization: A peptide substrate coupled to a fluorescent leaving group is designed. The assay is optimized for a 384-well or 1536-well microplate format to minimize reagent use [25].

- Reagent and Library Preparation: The enzyme, substrate, and test compounds from the library are dispensed into the microplates using automated liquid handling robots capable of nanoliter dispensing [25].

- Reaction and Incubation: The enzymatic reaction is initiated and allowed to incubate under controlled conditions. The activity of HDAC cleaves the substrate, releasing the fluorescent group [25].

- Detection and Readout: Fluorescence intensity is measured using a plate reader. An increase in fluorescence signal indicates inhibitor activity, as more substrate remains cleaved [25].

- Data Triage and Hit Identification: Data analysis software processes the results. "Hits" are identified based on a predefined threshold of activity (e.g., compounds showing >50% inhibition). Statistical methods and cheminformatic filters are applied to flag and eliminate false positives caused by assay interference [31] [25].

Protocol for a Phenotypic HCS Assay

This protocol details an imaging-based HCS, such as the Cell Painting assay or a targeted assay using fluorescent ligands [28] [32].

- Cell-Based Assay Setup: Cells are cultured in 96- or 384-well microplates and treated with compounds. For complex models, zebrafish embryos or 3D cell cultures like organoids may be used [15] [28].

- Staining and Fixation: Cells are stained with multiple fluorescent dyes to highlight specific cellular components (e.g., nucleus, actin, mitochondria, Golgi apparatus). Alternatively, targeted fluorescent ligands are used to label specific proteins like XPB in live cells [28] [32].

- Image Acquisition: Automated high-resolution fluorescence microscopes capture multiple images per well across different fluorescence channels [15] [26].

- Image Processing and Analysis: Advanced AI and machine learning algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), perform image segmentation to identify individual cells and subcellular structures. Hundreds of morphological features (size, shape, texture, intensity) are extracted quantitatively from each cell [28] [26].

- Data Integration and Phenotypic Profiling: The extracted features are integrated to create a high-dimensional "phenotypic fingerprint" for each treated sample. Machine learning models analyze these fingerprints to classify compounds, infer mechanisms of action, and identify subtle phenotypic changes [28] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions in HTS and HCS

| Reagent / Material | Function | Screening Context |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | Large collections of diverse chemical or biological molecules used for screening [27] [25] | HTS & HCS |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Probes | Tags for visualizing cellular components (e.g., DAPI for nucleus) or measuring enzymatic activity [15] [25] | HTS & HCS (Essential for HCS) |

| Clickable Chemical Probes | Specialized probes (e.g., TL-alkyne) for bio-orthogonal labeling, enabling direct visualization of drug-target interactions in live cells [32] | HCS |

| Microplates (96 to 1536-well) | Miniaturized assay platforms that enable high-density testing and reduce reagent consumption [25] | HTS & HCS |

| Cell Lines & 3D Organoids | Biological models for cell-based assays; 3D models provide more physiologically relevant data [27] [26] | Primarily HCS, also cell-based HTS |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotics for accurate, nanoliter-scale dispensing of reagents and compounds, enabling automation [27] [25] | HTS & HCS |

Synergistic Integration in the Drug Discovery Pipeline

HTS and HCS are not mutually exclusive but are most powerful when used synergistically. A typical modern drug discovery campaign leverages the strengths of both in a cascading workflow. The process begins with ultra-HTS (uHTS) to rapidly sieve through millions of compounds, identifying a smaller subset of potent "hits" [15] [25]. These hits are then funneled into secondary HCS assays, where their effects on complex cellular phenotypes are profiled. This step helps triage artifacts, identify off-target effects, and generate hypotheses about the mechanism of action [31] [15]. Finally, during lead optimization, HCS is invaluable for assessing cellular toxicity and efficacy in more physiologically relevant models, such as primary cells or 3D organoids, ensuring that only the most promising and safe candidates progress [15] [26].

Within the framework of comparative traditional versus HTE optimization research, HTS and HCS represent a fundamental evolution. HTS excels as the primary discovery engine, offering unparalleled speed and scale for navigating vast chemical spaces. HCS serves as the mechanistic interrogator, providing the deep, contextual biological insight necessary to understand why a compound is active and what its broader cellular consequences might be. The future of efficient drug discovery lies not in choosing one over the other, but in strategically integrating both. The convergence of these technologies with AI, more complex biological models like organoids, and novel probe chemistry [28] [32] is poised to further reduce attrition rates and usher in a new era of predictive and personalized therapeutics.

The high failure rate of clinical drug development, persistently around 90%, necessitates a critical re-evaluation of traditional optimization approaches [33]. Historically, drug discovery has rigorously optimized for structure-activity relationship (SAR) to achieve high specificity and potency against molecular targets, alongside drug-like properties primarily assessed through plasma pharmacokinetics (PK) [33]. However, a significant proportion of clinical failures due to insufficient efficacy (~40-50%) or unmanageable toxicity (~30%) suggest that critical factors affecting the clinical balance of efficacy and safety are being overlooked in early development [33] [34].

This guide compares two paradigms in early drug optimization: the Traditional SAR-Centric Approach, which primarily relies on plasma exposure, and the Integrated ADMET & STR Approach, which incorporates Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity (ADMET) profiling and Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR) early in the process. The integration of these elements, supported by High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), represents a fundamental shift aimed at de-risking drug candidates before they enter costly clinical trials [35] [36].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Optimization Strategies

Table 1: Core Differences Between Traditional and Modern Optimization Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional SAR-Centric Approach | Integrated ADMET & STR Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Potency (IC₅₀, Kᵢ) and plasma PK [33] | Balanced efficacy, tissue exposure, and safety [33] [37] |

| Distribution Assessment | Plasma exposure as surrogate for tissue exposure [33] | Direct measurement of tissue exposure and selectivity (STR) [33] [38] |

| Toxicity Evaluation | Often later stage; limited early prediction [34] | Early ADMET screening (e.g., Ames, hERG, CYP inhibition) [39] [34] |

| Throughput & Data | Lower throughput, OVAT (One Variable at a Time) [36] | High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), parallelized data-rich workflows [36] |

| Lead Candidate Selection | May favor compounds with high plasma AUC [33] | Selects for optimal tissue exposure/selectivity and acceptable plasma PK [33] [38] |

| Theoretical Basis | Free Drug Hypothesis [33] | Empirical tissue distribution data; acknowledges limitations of free drug hypothesis [33] |

The Critical Role of ADMET and STR in De-risking Development

Quantitative ADMET Scoring

The ADMET-score is a comprehensive scoring function developed to evaluate chemical drug-likeness based on 18 predicted ADMET properties [39]. It integrates critical endpoints such as Ames mutagenicity, hERG inhibition, CYP450 interactions, human intestinal absorption, and P-glycoprotein substrate/inhibitor status. The scoring function's weights are determined by model accuracy, endpoint importance in pharmacokinetics, and usefulness index, providing a single metric to prioritize compounds with a higher probability of success [39].

Table 2: Key ADMET Properties for Early Screening and Their Performance Metrics [39]

| Endpoint | Model Accuracy | Endpoint | Model Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ames mutagenicity | 0.843 | CYP2D6 inhibitor | 0.855 |

| Acute oral toxicity | 0.832 | CYP3A4 substrate | 0.66 |

| Caco-2 permeability | 0.768 | CYP inhibitory promiscuity | 0.821 |

| hERG inhibitor | 0.804 | P-gp inhibitor | 0.861 |

| Human intestinal absorption | 0.965 | P-gp substrate | 0.802 |

Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship (STR)

STR is an emerging concept that investigates how structural modifications influence a drug's distribution and accumulation in specific tissues, particularly disease-targeted tissues versus normal tissues [33] [37]. This relationship is crucial because plasma exposure often poorly correlates with target tissue exposure.

A seminal study on Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) demonstrated that drugs with similar structures and nearly identical plasma exposure (AUC) could have dramatically different distributions in target tissues like tumors, bone, and uterus [33] [37]. This tissue-level selectivity was directly correlated with their observed clinical efficacy and safety profiles, suggesting that STR optimization is critical for balancing clinical outcomes [33].

Experimental Protocols and Data Generation

HTE-Enabled ADMET Screening

Protocol Overview: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) employs miniaturized, parallelized reactions to rapidly profile compounds across a wide array of conditions and assays [36].

Key Methodologies:

- In vitro ADMET assays are conducted using automated platforms. These include:

- CYP450 Inhibition: Using liver microsomes or hepatocytes to assess drug-drug interaction potential [34].

- Metabolic Stability: Incubating compounds with liver microsomes/S9 fractions and quantifying parent compound loss over time [34].

- Cellular Permeability: Utilizing Caco-2 or MDCK cell monolayers to predict intestinal absorption [39] [34].

- hERG Inhibition: Binding or functional assays to flag potential cardiotoxicity [39].

- Toxicokinetics (TK) studies link external exposure concentrations to internal doses in animal models, often using higher, therapeutically irrelevant doses to understand toxicity thresholds [40] [41]. Data from these studies are used to estimate a safe starting dose for human clinical trials [41].

STR Determination Protocol

Protocol Overview: Quantifying drug concentrations in multiple tissues over time to establish STR and calculate tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficients (Kp) [33] [38].

Detailed Workflow:

- Animal Dosing: Administer a single dose of the drug candidate (e.g., orally or intravenously) to relevant animal models (e.g., transgenic disease models when possible) [33].

- Serial Sacrifice and Sampling: At predetermined time points post-dosing, collect blood/plasma and a comprehensive panel of tissues (e.g., target tissue, liver, kidney, heart, brain, muscle) [33].

- Sample Processing: Homogenize tissue samples. Use protein precipitation (e.g., with ice-cold acetonitrile) or other extraction methods to isolate the drug and metabolites from plasma and tissue homogenates [33].

- Bioanalysis: Employ sensitive analytical techniques like LC-MS/MS or UPLC-HRMS to quantify drug concentrations in each sample [33] [38].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Area Under the Concentration-time curve (AUC) for plasma and each tissue. The tissue-to-plasma distribution coefficient (Kp) is determined as AUCtissue / AUCplasma [38].

Table 3: Experimental Tissue Distribution Data for CBD Carbamates L2 and L4 [38]

| Compound | Plasma AUC (ng·h/mL) | Brain AUC (ng·h/g) | Brain Kp (AUCbrain/AUCplasma) | eqBuChE IC₅₀ (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 | ~1200 | ~6000 | ~5.0 | 0.077 |

| L4 | ~1200 | ~1200 | ~1.0 | Most potent |

This table illustrates the STR concept: while L2 and L4 have identical plasma exposure, L2 achieves a 5-fold higher brain concentration, which is critical for CNS-targeted drugs, despite L4 having superior in vitro potency [38].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: A comparison of drug optimization workflows. The integrated approach introduces critical ADMET and STR profiling earlier, creating a more robust and de-risked development pipeline.

Diagram 2: The central principle of STR. Drug exposure in plasma is a poor predictor of tissue exposure, which in turn is a stronger correlate of clinical efficacy and toxicity. STR is the key determinant of tissue exposure and selectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for ADMET and STR Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Liver Microsomes / Hepatocytes | In vitro models for assessing metabolic stability and CYP450 inhibition/induction [34]. |

| Caco-2 / MDCK Cells | Cell-based assays to predict intestinal permeability and absorption [34]. |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes | Specific isoform-level analysis of metabolic pathways and drug-drug interactions [39]. |

| hERG Assay Kits | Screening for potential cardiotoxicity by inhibiting the hERG potassium channel [39]. |

| Bioanalytical Internal Standards | Isotope-labeled compounds for accurate LC-MS/MS quantification of drugs and metabolites in biological matrices [33]. |

| Tissue Homogenization Kits | Reagents and protocols for efficient and consistent extraction of analytes from diverse tissue types [33]. |

The expanding scope of early drug development to systematically incorporate ADMET profiling and STR analysis represents a necessary evolution from traditional, potency-centric approaches. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented in this guide consistently demonstrate that plasma exposure is a poor surrogate for target tissue exposure, and over-reliance on it can mislead candidate selection [33] [38] [37]. The integration of these elements, powered by modern HTE platforms that generate rich, parallelized datasets, provides a more holistic and predictive framework for selecting drug candidates with the highest likelihood of clinical success, ultimately aiming to improve the unacceptably high failure rates in drug development [36].

A Tale of Two Pipelines: Methodologies in Traditional and HTE Workflows

The hit-to-lead (H2L) and subsequent lead optimization phases represent a critical, well-established pathway in small-molecule drug discovery. This traditional approach is characterized by a linear, multi-step process designed to transform initial screening "hits"—compounds showing any desired biological activity—into refined "lead" candidates with robust pharmacological profiles suitable for preclinical development [42] [43]. The entire process from hit identification to a preclinical candidate typically spans 4-7 years, with the H2L phase itself averaging 6-9 months [42] [44]. The primary objective of this rigorous pathway is to thoroughly evaluate and optimize chemical series against a multi-parameter profile, balancing potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties while systematically reducing attrition risk before committing to costly late-stage development [43] [45].

This traditional methodology relies heavily on iterative Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycles [42]. In this framework, medicinal chemists design new compounds based on emerging structure-activity relationship (SAR) data, followed by synthesis ("Make"), biological and physicochemical testing ("Test"), and data analysis to inform the next design cycle [42] [46]. The process is driven by a defined Candidate Drug Target Profile (CDTP), which establishes specific criteria for potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetics, and safety that must be met for a compound to advance [42]. Initially, H2L exploration typically begins with 3-4 different chemotypes, aiming to deliver at least 2 promising lead series for the subsequent lead optimization phase [42].

The Hit-to-Lead and Lead Optimization Workflow

Stage 1: Hit Identification and Triage

The traditional H2L process begins after the identification of "hits" from high-throughput screening (HTS), virtual screening, or fragment-based approaches [42] [44]. A hit is defined as a compound that displays desired biological activity toward a drug target and reproduces this activity upon retesting [42]. Following primary screening, the hit triage process is employed to select the most promising starting points from often hundreds of initial actives [43]. This critical winnowing uses multi-parameter optimization strategies such as the "Traffic Light" (TL) system, which scores compounds across key parameters like potency, ligand efficiency, lipophilicity (cLogP), and solubility [43]. Each parameter is assigned a score (good=0, warning=1, bad=2), and the aggregate "golf score" (where lower is better) enables objective comparison of diverse chemotypes [43]. This systematic prioritization ensures resources are focused on hit series with the greatest potential for successful optimization.

Stage 2: Core Hit-to-Lead Optimization

The H2L phase focuses on establishing a robust understanding of the Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) within each hit series [42] [46]. Through iterative DMTA cycles, medicinal chemists synthesize analogs to explore the chemical space around the original hits, systematically improving key properties [42]. The screening cascade during this phase expands significantly beyond primary activity to include orthogonal assays that confirm target engagement and mechanism of action, selectivity panels against related targets to minimize off-target effects, and early ADME profiling (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) to assess drug-like properties [47] [43]. Critical properties optimized during H2L include:

- Potency: Improving half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) or effective concentration (EC₅₀) values, often guided by metrics like Ligand Efficiency (LE) and Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) that penalize excessive molecular size or lipophilicity [43].

- Selectivity: Demonstrating specific activity against the intended target versus unrelated proteins or closely related family members [47] [45].

- Physicochemical Properties: Optimizing solubility, lipophilicity (LogP), and molecular size to ensure adequate exposure and absorption [43].

- Early ADME: Assessing metabolic stability (e.g., in liver microsomes), membrane permeability, and protein binding [42] [45].

- In Vitro Safety: Initial cytotoxicity screening and assessment of activity against anti-targets such as cytochrome P450 enzymes [43].

Table 1: Key Assays in the Hit-to-Lead Screening Cascade

| Assay Category | Specific Examples | Primary Objective | Typical Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Potency | Enzyme inhibition, Binding assays (SPR, ITC) | Confirm primary target engagement and measure affinity | IC₅₀, Kd, Ki |

| Cell-Based Activity | Reporter gene assays, Pathway modulation | Demonstrate functional activity in cellular context | EC₅₀, % inhibition/activation |

| Selectivity | Counter-screening against related targets, Orthologue assays | Identify and minimize off-target interactions | Selectivity ratio (e.g., 10-100x) |

| Physicochemical | Kinetic solubility, Lipophilicity (LogD) | Ensure adequate drug-like properties | Solubility (µg/mL), cLogP/LogD |

| Early ADME | Metabolic stability (microsomes), Permeability (PAMPA, Caco-2) | Predict in vivo exposure and absorption | % remaining, Papp |

| In Vitro Safety | Cytochrome P450 inhibition, Cytotoxicity | Identify early safety liabilities | % inhibition at 10 µM, CC₅₀ |

Stage 3: Lead Optimization

Lead optimization (LO) represents an extension and intensification of the H2L process, focusing on refining the most promising lead series into preclinical candidates [42] [44]. While H2L typically aims to identify compounds suitable for testing in animal disease models, LO demands more stringent criteria appropriate for potential clinical use [45]. This phase involves deeper pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies, including in vivo profiling to understand absorption, distribution, and elimination [44]. Additional considerations include:

- Advanced SAR Exploration: Employing techniques like scaffold hopping to modify core structures while maintaining potency but improving properties like solubility or reducing toxicity [44].

- Stereochemistry Optimization: Investigating enantiomeric differences that can significantly impact both potency and toxicity profiles [44].

- Comprehensive Safety Assessment: Expanding toxicity screening to include genetic toxicity, cardiovascular safety (hERG channel binding), and broader organ toxicity panels [44].

- Formulation Development: Initial work on salt forms, crystallinity, and prodrug approaches to enhance bioavailability [44].

The successful output of lead optimization is a preclinical candidate that meets the predefined Candidate Drug Target Profile and is suitable for regulatory submission as an Investigational New Drug (IND) [42] [44].

Diagram 1: Traditional H2L and Lead Optimization Workflow. This linear process transitions from initial hits through progressive optimization stages to a preclinical candidate.

Quantitative Comparison of Traditional Optimization

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Traditional H2L and Lead Optimization

| Performance Metric | Hit-to-Lead Phase | Lead Optimization Phase | Overall (H2L through LO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Timeline | 6-9 months [42] | 2-4 years [44] | 3-5 years [44] |

| Initial Compound Input | 3-4 chemotypes [42] | 2-3 lead series [42] | 3-4 initial chemotypes |

| Compounds Synthesized & Tested | Hundreds [43] | Thousands [44] | Thousands |

| Key Success Metrics | Robust SAR established, Favorable early ADME, 2 series selected for LO [42] | PIC50 >7, LipE >5, Solubility >10 µg/mL, Clean in vitro safety [43] | Meets Candidate Drug Target Profile [42] |

| Attrition Rate | High (Multiple series eliminated) [42] | Moderate (Lead series refined) | ~90% from hit to preclinical candidate [44] |

| Primary Optimization Focus | Potency, Selectivity, Early ADME [47] | PK/PD, Safety, Pharmocokinetics [44] | Multi-parameter optimization [42] |

The quantitative profile of the traditional pathway reveals a process of progressive focus and refinement. The hit-to-lead phase serves as a rigorous filter, systematically eliminating problematic chemotypes while investing in the most promising series. The high attrition during H2L is strategic, designed to prevent costly investment in suboptimal chemical matter during the more resource-intensive lead optimization phase [42]. The transition to LO is marked by a defined milestone—typically the identification of compounds with sufficient potency (often PIC50 >7), favorable lipophilic efficiency (LipE >5), and acceptable solubility (>10 µg/mL) that can be tested in animal models of disease [43] [45].

Experimental Protocols in Traditional H2L/LO

Protocol 1: Hit Triage and Progression Criteria

The initial triage of HTS hits follows a standardized protocol to eliminate false positives and prioritize scaffolds with optimal developability potential [43].

Methodology:

- Activity Confirmation: Retest primary hits in concentration-response format to determine IC₅₀/EC₅₀ values and confirm dose-dependent activity [43].

- Orthogonal Assay Validation: Test confirmed hits in a biophysical binding assay (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance - SPR) to verify direct target engagement and eliminate assay-specific artifacts [42] [43].

- Compound Integrity Verification: Confirm chemical structure and purity (>95%) of hits via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [43].

- Computational Profiling: Calculate key physicochemical parameters (molecular weight, cLogP, topological polar surface area - TPSA) and efficiency metrics (Ligand Efficiency - LE, Lipophilic Efficiency - LipE) [43].