Validating Machine Learning Predictions in Organic Chemistry: From Digital Models to Laboratory Benches

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate machine learning (ML) predictions in organic chemistry and drug discovery.

Validating Machine Learning Predictions in Organic Chemistry: From Digital Models to Laboratory Benches

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate machine learning (ML) predictions in organic chemistry and drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of ML validation, details cutting-edge methodological applications from reaction prediction to crystal structure analysis, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous comparative evaluation guidelines. By synthesizing insights from large-scale validation studies, prospective drug development projects, and the latest evaluation standards, this guide aims to bridge the gap between computational forecasts and experimental reliability, thereby accelerating robust and trustworthy ML integration into chemical research and development.

The Critical Need for ML Validation in Chemical Sciences

In organic chemistry and drug development, the transition from a machine learning (ML) prediction to a tangible, synthesized compound hinges on a critical process: validation. This process defines the bridge between theoretical algorithmic output and actionable chemical insight. As machine learning models become deeply integrated into the research pipeline, a rigorous, multi-faceted validation strategy is paramount. It ensures that predictions about molecular properties, reaction outcomes, or new chemical entities are not merely statistical artifacts but are reliable, reproducible, and chemically plausible. This guide objectively compares validation methodologies, from statistical foundations to experimental confirmation, providing researchers with the protocols and metrics needed to critically evaluate ML performance in a chemical context.

Core Concepts: Machine Learning Validation Fundamentals

At its heart, validation in machine learning is the practice of estimating how well a model will perform on new, unseen data. This is distinct from training, where a model learns patterns from a known dataset. A robust validation strategy guards against overfitting, a scenario where a model memorizes training data—including its noise and outliers—but fails to generalize to new data [1].

Foundational Validation Strategies

Several core methodologies form the bedrock of model evaluation:

The Three-Way Holdout Method: This fundamental approach splits the data into three distinct sets [1] [2]. The training set is used to derive the ML algorithm. The validation set provides an unbiased evaluation for hyperparameter tuning and model selection. Finally, the test set (or hold-out set) is reserved for a final, independent evaluation of the chosen model. A critical guideline is to use the test set only for this final assessment; any prior use risks information leakage and an overly optimistic performance estimate [1].

K-Fold Cross-Validation: To make maximal use of limited data, K-Fold cross-validation is widely employed. The entire dataset is partitioned into k subsamples (or folds). The model is trained k times, each time using k-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. The performance is then averaged across all k iterations [1] [2]. This method provides a more comprehensive view of model robustness and range than a single holdout split. For datasets with class imbalances, Stratified K-Fold cross-validation is recommended, as it preserves the original class distribution in each fold [2].

Quantifying Performance: Key Evaluation Metrics

Choosing the right evaluation metric is crucial and should reflect the ultimate business or research goal. These metrics quantitatively answer the question: "How good is the model?" [2].

Table: Common Machine Learning Metrics for Model Evaluation

| Model Type | Metric | Definition | Interpretation in a Chemical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Accuracy | (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Predictions | Overall ability to correctly categorize, e.g., successful vs. failed reactions. |

| Precision | True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives) | When a model predicts a compound is active, how often is it correct? Minimizes wasted resources on false leads. | |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) | Ability to find all truly active compounds in a dataset. Crucial for avoiding missed discoveries. | |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall | A single metric balancing the trade-off between Precision and Recall. | |

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes (e.g., active/inactive) across all classification thresholds. | |

| Regression | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Average of the squares of the errors between predicted and actual values. | Heavily penalizes large errors, e.g., a large error in predicting reaction yield is considered very bad. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Average of the absolute differences between predicted and actual values. | Provides a linear penalty for errors, offering a more intuitive average error magnitude. |

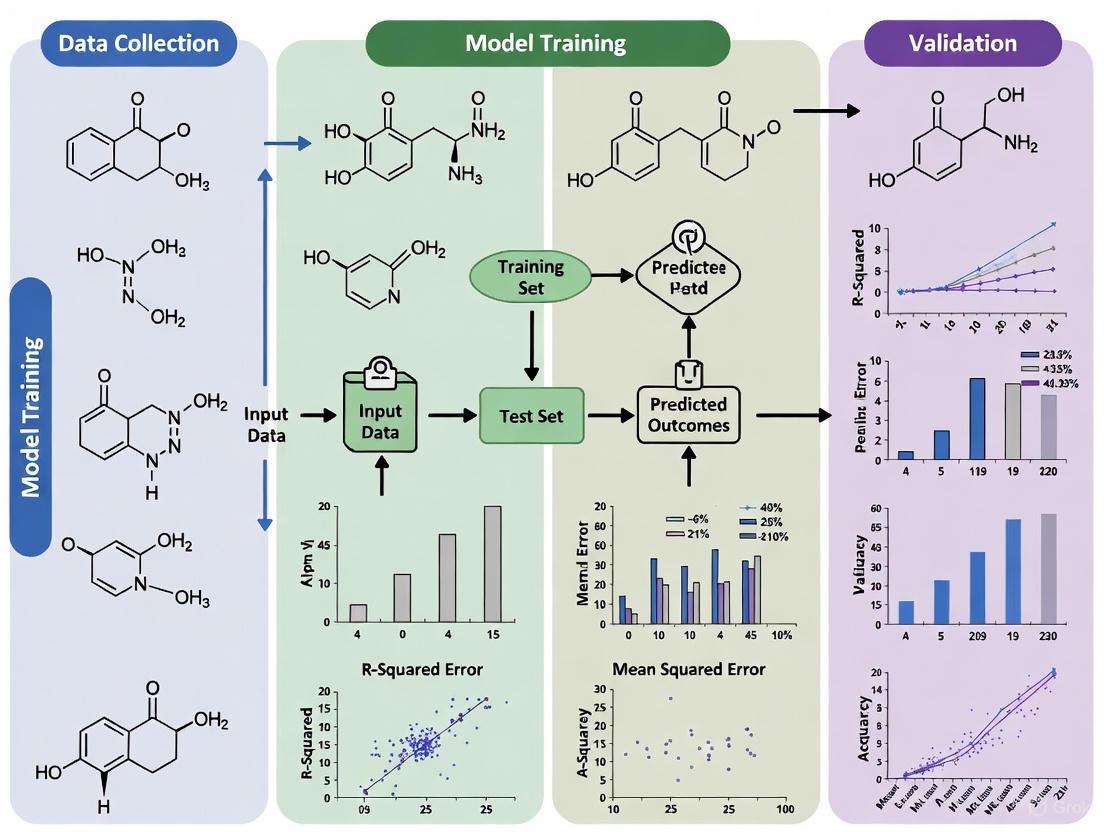

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard process for applying these fundamental validation techniques in a machine learning project:

Validation in Practice: A Chemical Case Study

Theoretical validation is meaningless without practical application. A compelling example of advanced validation in chemical research is the MEDUSA Search engine, a machine-learning-powered tool designed for deciphering tera-scale mass spectrometry (HRMS) data to discover previously unknown organic reactions [3].

Experimental Protocol: MEDUSA Search Workflow

The validation protocol within MEDUSA is a multi-stage, iterative process designed to move from a raw data hypothesis to a confirmed chemical insight [3]:

- Hypothesis Generation: The process begins by generating a list of hypothetical reaction pathways or ions of interest. This can be based on prior knowledge of the reaction system, such as breakable bonds and fragment recombination, or automated methods like BRICS fragmentation.

- Data Search & Ion Detection: The chemical formula and charge of a query ion are used to calculate its theoretical isotopic pattern. A coarse search identifies mass spectra containing the two most abundant isotopologue peaks. A subsequent, precise isotopic distribution search is performed on these candidate spectra using a cosine similarity metric.

- Machine Learning Filtering: A key step involves using ML models, trained on synthetic MS data, to filter out false positive matches. This step estimates an ion presence threshold based on the query ion's formula, adding a layer of intelligent, data-driven validation.

- Chemical Interpretation & Orthogonal Confirmation: The final, and most critical, validation step is chemical. The user must interpret the results—supplementing the ML findings with orthogonal methods like NMR spectroscopy or tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to manually verify the ion's structure. This closes the loop between algorithmic detection and chemical reality.

This integrated approach exemplifies "experimentation in the past," where new discoveries are made by rigorously validating hypotheses against vast repositories of existing experimental data, reducing the need for new wet-lab experiments [3].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Reaction Discovery

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Validation Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) | Generates the primary analytical data (mass spectra) with high accuracy and sensitivity, enabling the detection of precise isotopic distributions [3]. |

| MEDUSA Search Engine | The core software platform that performs the ML-powered search and initial validation of ion presence in tera-scale MS datasets [3]. |

| Synthetic MS Data | Used to train the ML models in the absence of large, manually annotated datasets. Simulates isotopic patterns and instrument errors to create robust models [3]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Provides orthogonal, structural validation for ions discovered via the ML-driven workflow, confirming molecular structure beyond mass formula [3]. |

| Chloranilic Acid (CA) | An example of a coformer used in cocrystal discovery campaigns [4], analogous to a reactant in reaction discovery, used for experimental validation. |

The diagram below visualizes this integrated, iterative workflow for ML-powered reaction discovery and its validation steps:

Comparative Analysis: Validation Methods at a Glance

Different stages of the research pipeline demand different validation approaches. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the methods discussed, highlighting their primary use cases and limitations.

Table: Comparison of Validation Methods for ML in Chemistry

| Validation Method | Primary Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Way Holdout [1] [2] | Initial model evaluation and selection. | Simple to implement; clear separation of roles between training, validation, and test sets. | Performance can be sensitive to a single, random data split; less efficient with small datasets. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation [1] [2] | Robust performance estimation with limited data. | Reduces variance by averaging multiple runs; makes efficient use of all data. | Computationally more expensive; requires careful setup to avoid data leakage. |

| A/B Testing [5] | Comparing two or more versions of a deployed model (e.g., in production). | Provides a direct, live comparison of model performance on real-world tasks. | Requires robust infrastructure; ethical considerations if testing impacts user experience. |

| Orthogonal Experimental Confirmation [3] | Final, definitive validation of an ML-generated chemical hypothesis. | Provides ground-truth, physical evidence (e.g., structural confirmation via NMR). | Can be time-consuming and resource-intensive; requires expertise and laboratory access. |

Defining validation in the context of machine learning for organic chemistry requires a synthesis of rigorous statistical practice and definitive experimental science. As demonstrated, the journey from an algorithmic output to an actionable chemical insight is not a single step but a multi-stage process. It begins with statistical assurances—using holdout methods and cross-validation to ensure generalizability—and culminates in physical verification, where tools like mass spectrometry and NMR provide the ultimate judgment on a model's predictions.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the critical takeaway is that no single validation method is sufficient. A robust framework integrates them all: using K-fold cross-validation to select a promising model, a holdout test set for a final unbiased performance check, and, most importantly, designing a clear pathway for experimental confirmation. This comprehensive approach transforms machine learning from a black-box predictor into a powerful, reliable partner in the discovery of new chemical knowledge.

In the field of organic chemistry research, the adoption of machine learning (ML) for predicting reaction outcomes and optimizing syntheses is rapidly accelerating. However, for these models to gain the trust of researchers and become integral to the drug development pipeline, they must overcome three fundamental challenges: interpretability, data scarcity, and real-world generalization. This guide provides an objective comparison of how different ML approaches address these challenges, presenting quantitative performance data and detailed experimental methodologies to inform scientists and research professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance

The performance of ML models is highly dependent on the data context and the specific challenge being addressed. The tables below summarize the performance of various algorithms across different tasks relevant to organic chemistry and related fields.

Table 1: Model Performance in Predictive Maintenance (Addressing Data Scarcity with Synthetic Data) [6]

| Model | Accuracy | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 88.98% | Predictive Maintenance |

| Random Forest | 74.15% | Predictive Maintenance |

| k-Nearest Neighbour (kNN) | 74.02% | Predictive Maintenance |

| XGBoost | 73.93% | Predictive Maintenance |

| Decision Tree | 73.82% | Predictive Maintenance |

Note: These models were trained on a dataset augmented with synthetic data generated by a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to overcome data scarcity.

Table 2: Generalization Error Comparison from Simulation Study (Varying Data Conditions) [7]

| Model | Optimal Performance Context |

|---|---|

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | Smaller number of correlated features (number of features not exceeding ~half the sample size). Superior in average generalization error and stability. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) with RBF Kernel | Larger feature sets, provided sample size is not too small (at least 20). Outperformed LDA, RF, and kNN by a clear margin. |

| k-Nearest Neighbour (kNN) | Performance improves with number of features; outplays LDA and RF unless data variability is high and/or effect sizes are small. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Outperformed only kNN in instances with high data variability and small effect sizes; provided more stable error estimates. |

Table 3: Performance in IoT Data Classification [8]

| Model | Relative Performance |

|---|---|

| Random Forests | Performed better than other machine learning models considering all performance metrics (precision, recall, f1-score, accuracy, ROC-AUC). |

| ANN & CNN | Achiehed more interesting results among deep learning models. |

Core Challenge 1: Interpretability

Interpretability is crucial for chemists to trust and understand a model's predictions, especially when the model's objective function does not fully capture real-world costs like ethics or fairness [9].

Defining Interpretability

Interpretability in ML can be broken down into two broad categories [9]:

- Transparency: Understanding the model's internal mechanism.

- Simulatability: A human can simulate the model's calculations in a reasonable time.

- Decomposability: Each part of the model (inputs, parameters, calculations) has an intuitive explanation.

- Algorithmic Transparency: Theoretical guarantees about the algorithm's behavior.

- Post-hoc Explanations: Extracting information from a trained model to explain its learned patterns.

- Text Explanations: Natural language justifications for decisions.

- Visualization: Techniques like t-SNE or saliency maps to show what the model "sees".

- Local Explanations: Explaining individual predictions rather than the entire model.

- Explanation by Example: Justifying predictions by showing similar training instances.

Evaluation of Interpretability Methods

The evaluation of interpretability methods should be human-centric. Doshi-Velez & Kim propose a hierarchy of evaluation methods [9]:

- Application-Grounded Evaluation: Involves domain experts (e.g., chemists) performing real-world tasks using the explanations. This is the most rigorous but costly method.

- Human-Grounded Evaluation: Uses human subjects on simplified tasks, balancing cost and rigor.

- Functionally-Grounded Evaluation: Uses proxy metrics (e.g., model sparsity) where no human subjects are involved; less definitive but more accessible.

Core Challenge 2: Data Scarcity

Data scarcity is a primary barrier for applying deep learning in many scientific domains, including organic chemistry, where labeled data from failed or successful reactions may be limited [10].

Solutions for Data Scarcity

Table 4: Strategies to Overcome Data Scarcity and Imbalance

| Technique | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Two neural networks (Generator and Discriminator) are trained adversarially to generate synthetic data that mimics real data patterns [6] [10]. | Generating synthetic run-to-failure data for predictive maintenance models [6]. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) | A model pre-trained on a large, general dataset (e.g., Wikipedia text) is fine-tuned on a smaller, domain-specific dataset (e.g., chemical reaction data) [10] [11]. | Fine-tuning a general language model on a small set of labeled tweets for sentiment analysis [11]. |

| Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) | A model learns representations from unlabeled data by solving a pretext task (e.g., predicting a masked word), reducing the need for labeled data [10]. | Not explicitly detailed in results, but a key state-of-the-art technique [10]. |

| Failure Horizons | To address class imbalance, the last 'n' observations before a failure event are labeled as 'failure' instead of just the final point, increasing failure examples [6]. | Used in predictive maintenance with run-to-failure data to create a more balanced dataset for training [6]. |

| Heuristics | Using simple, rule-based models designed with domain knowledge to get an application started when no or very little data exists [11]. | Ranking news articles using hand-tuned weights for recency, relevance, and publisher popularity [11]. |

| Synthetic Data (SMOTE) | Generating artificial examples for the minority class in a dataset to balance class distribution [11]. | Augmenting a spam detection dataset where spam emails are rare [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Addressing Scarcity with GANs

The following workflow, as applied in predictive maintenance, can be adapted for generating synthetic organic reaction data [6].

Core Challenge 3: Real-World Generalization

A model that performs well on its training data but fails on new, unseen data from the real world has poor generalization. This is a critical concern in laboratory and production environments.

Ensuring Robust Generalization

- Temporal Feature Extraction: For sequential data like sensor readings or reaction time series, using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks can help extract temporal patterns and improve generalization over statistical methods [6].

- Proper Model Comparison Protocols: Reliable generalization error estimation requires robust statistical methods to avoid bias from single data splits [7] [12].

- Corrected Resampled t-test: Accounts for the correlation between training sets in cross-validation, providing more reliable hypothesis testing than a standard t-test [12].

- Repeated k-Fold Cross-Validation: Averages performance across multiple runs and folds to reduce sampling fluctuations and deliver tighter confidence intervals [12].

Experimental Protocol: Comparing ML Models

The methodology below, derived from a simulation study, provides a framework for objectively comparing the generalization performance of different algorithms [7].

Key variable factors to define include [7]:

- Number of features (p)

- Training sample size (n)

- Biological / between-subjects variation (σb)

- Within-subject / experimental variation (σe)

- Effect size (θ)

- Correlation between features (ρ)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Computational Tools for ML in Chemistry Research

| Item | Function in ML Experimentation |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables massively parallel processing for extensive simulation studies and hyperparameter optimization, reducing experiment time from weeks to hours [7]. |

| Community Innovation Survey (CIS) Data | An example of a structured, firm-level dataset used for benchmarking ML models predicting innovation outcomes, analogous to chemical reaction databases [12]. |

| Reaxys Database | A critical source of chemical reaction data (∼10 million examples) used for training foundational ML models for reaction condition prediction [13] [14]. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | A software framework (e.g., using TensorFlow or PyTorch) used to generate synthetic data and augment small experimental datasets [6] [10]. |

| Corrected Resampled t-test | A statistical script/procedure used to reliably compare the performance of two ML models by accounting for dependencies in cross-validation splits [12]. |

| optBiomarker R Package | An example of specialized software providing simulation (simData) and performance estimation (classificationError) tools for rigorous method comparison [7]. |

Case Study: ML for Predicting Organic Reaction Conditions

A neural network model trained on ~10 million reactions from Reaxys demonstrates the potential of ML in organic chemistry, achieving a 69.6% top-10 accuracy for predicting a close match to recorded catalysts, solvents, and reagents. Top-10 accuracies for individual species reached 80-90%. Temperature was predicted within ±20°C in 60-70% of test cases [13] [14]. This showcases a practical application where large-scale data helps create a tool with significant utility for chemists in planning syntheses.

In the demanding field of drug development, the validation of predictive models is not merely a technical checkbox but a critical determinant of commercial success and patient impact. Poor validation, particularly of machine learning (ML) tools and experimental data, directly fuels skyrocketing costs and protracted timelines. This guide examines the tangible impact of validation rigor within organic chemistry research and early drug discovery, providing a comparative analysis of approaches and the concrete experimental protocols that underpin them.

Quantifying the Impact: The Cost of Poor Validation

The financial and temporal penalties of inadequate validation are severe and measurable. The following tables summarize the direct consequences across the drug development pipeline.

Table 1: Impact of Poor Data Quality on R&D Costs and Timelines

| Cost Category | Financial Impact | Timeline Impact | Primary Data Quality Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeating Experiments/Trials | Significant waste of materials, labor, and resources [15] | Bottlenecks in target validation and preclinical studies [15] | Inconsistent datasets, errors in sample labeling [15] |

| Investment in Failed Candidates | Wasted resources on ineffective compounds [15] | Delays in progressing through research pipelines [15] | Incorrect experimental annotations (e.g., misreported concentrations) [15] |

| Regulatory Submission Delays | Additional studies and extended review costs [15] | Extended timeline for drug approval [15] | Lack of data standardization across clinical trial sites [15] |

Table 2: Drug Development Lifecycle and Attrition Rates [16]

| Development Stage | Average Duration (Years) | Probability of Transition to Next Stage | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 2-4 | ~0.01% (to approval) | Toxicity, lack of effectiveness |

| Phase I | 2.3 | ~52% - 70% | Unmanageable toxicity/safety |

| Phase II | 3.6 | ~29% - 40% | Lack of clinical efficacy |

| Phase III | 3.3 | ~58% - 65% | Insufficient efficacy, safety |

| FDA Review | 1.3 | ~91% | Safety/efficacy concerns |

The data shows that Phase II trials are the epicenter of value destruction, primarily due to a lack of efficacy that often originates from poorly validated predictions in early research [16]. When ML models used in organic chemistry to predict compound activity or synthetic pathways are not rigorously validated, they propagate errors that culminate in costly clinical failures.

Comparative Analysis: Validation in Machine Learning for Chemistry

The core of robust ML validation in chemistry lies in the methodology for assessing model performance. The following experiment illustrates a direct comparison between different validation approaches.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking ML Model Performance

- Objective: To evaluate the impact of validation data quality on the performance of a machine learning model predicting reaction outcomes in organic chemistry.

- Dataset: The experiment utilizes two primary data sources:

- High-Quality, Real-World Data: Curated, standardized data from the PharmaBench dataset, which employs a multi-agent LLM system to extract and harmonize experimental conditions from public bioassays [17].

- Synthetic or Poorly-Curated Data: Artificially generated data or data lacking standardized experimental conditions (e.g., varying buffers, pH levels, and procedures) [17] [18].

- Model Training: A consistent ML model architecture (e.g., a graph neural network) is trained on each of the two datasets to predict the success of a Mizoroki-Heck reaction, a widely used carbon-carbon bond-forming reaction [3].

- Validation Method: Model performance is assessed through:

- Retrospective Validation: Testing on a held-out portion of the training data.

- Prospective Validation: Deploying the model to predict outcomes for new, previously unseen reactions, which is considered the gold standard for assessing real-world utility [19].

- Key Metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score are calculated for both models on the prospective validation set.

Results and Comparison

Table 3: ML Model Performance Based on Validation Data Quality

| Validation Metric | Model Trained on High-Quality Real-World Data | Model Trained on Synthetic/Poorly-Curated Data |

|---|---|---|

| Retrospective Accuracy | 94% | 92% |

| Prospective Accuracy | 88% | 62% |

| Prospective Precision | 85% | 58% |

| Prospective Recall | 82% | 55% |

| Impact on Research | Reliable prediction of viable synthetic pathways; enables "experimentation in the past" by discovering new reactions from existing data [3]. | High false-positive rate; leads to pursuit of non-viable reactions, wasting laboratory resources and time. |

The results demonstrate a critical divergence. While both models perform similarly in a controlled, retrospective test, the model trained on high-quality real-world data maintains robust performance in a prospective, real-world scenario. In contrast, the model trained on lower-quality data fails catastrophically outside its training environment. This directly mirrors the high failure rate in Phase II clinical trials, where a lack of efficacy—often rooted in unvalidated preclinical predictions—becomes apparent [19] [16].

Experimental Workflow for Robust Validation

The following diagram illustrates a robust validation workflow for ML-powered discovery, integrating mass spectrometry analysis to confirm hypothetical reactions.

ML-Powered Reaction Discovery Workflow

Detailed Methodologies

- Hypothesis Generation (Step 1): The process begins by defining potential reaction pathways based on breakable bonds and the recombination of corresponding molecular fragments. This can be automated using algorithms like BRICS fragmentation or multimodal Large Language Models (LLMs) [3].

- Theoretical Pattern Calculation (Step 3): For a given query ion's chemical formula and charge, the engine calculates its theoretical "isotopic pattern," which serves as a unique fingerprint [3].

- ML-Powered Search (Steps 5-7): The search is a multi-stage process:

- Coarse Search: The two most abundant isotopologue peaks from the theoretical pattern are searched against an inverted index of the mass spectrometry database with high precision (0.001 m/z) [3].

- Isotopic Distribution Search: For candidate spectra, a machine learning model calculates the cosine similarity between the theoretical isotopic distribution and the observed peaks in the spectrum [3].

- Automated Decision: A second ML model, trained on synthetic data, estimates an ion-presence threshold specific to the query ion's formula. If the cosine similarity exceeds this threshold, the ion is considered present [3].

- Orthogonal Validation (Step 8): A crucial final step. While the MS search confirms the presence of an ion with a specific formula, its exact structure must be verified using orthogonal methods like Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy or tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Validation

| Item / Solution | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| MEDUSA Search Engine | A machine learning-powered search engine for discovering organic reactions by analyzing tera-scale high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data [3]. |

| PharmaBench Dataset | A comprehensive, LLM-curated benchmark set for ADMET properties, providing high-quality, standardized data for training and validating predictive models [17]. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) | An analytical instrument used for precise detection and characterization of chemical compositions; the primary source of data for the discovery workflow [3]. |

| Polly Platform | A data harmonization platform that integrates and standardizes data from multiple sources, ensuring consistency and implementing quality control checks to prevent downstream failures [15]. |

| GPT-4 / Multi-Agent LLM System | Large Language Models used to automatically extract and standardize complex experimental conditions from unstructured text in bioassay descriptions, solving data curation challenges [17]. |

The high stakes of drug development demand a paradigm shift where validation is integrated into the fabric of research. Relying on synthetic data or poorly curated datasets for AI model training introduces profound risks, as evidenced by the significant performance drop in prospective validation [18]. The industry is consequently moving towards a framework that prioritizes high-quality, real-world data and prospective, clinical-grade validation [19] [18]. Adopting rigorous, standardized experimental protocols and leveraging modern computational tools are no longer optional best practices but fundamental requirements for compressing timelines, reducing costs, and delivering effective therapies to patients.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into organic chemistry and drug discovery has ushered in an era of unprecedented data generation and analysis capabilities. However, this rapid adoption has created a critical need for robust validation frameworks to separate genuine advancements from exaggerated claims [20]. The scientific community finds itself at a crossroads, where establishing a gold standard for validating ML predictions is paramount for building foundational trust. This guide examines the central role of experimental-correlation—the rigorous benchmarking of computational outputs against empirical data—as the cornerstone of this validation framework. Within this context, we objectively compare emerging ML-powered tools against traditional experimental methods, providing researchers with the analytical resources needed to critically evaluate performance claims and implementation readiness.

The Theoretical Foundation: From Statistical Validation to Chemical Reality

A gold standard in ML evaluation must be grounded in both statistical rigor and domain-specific applicability. Cross-validation (CV) has long been the default statistical method for evaluating model performance, but recent theoretical analyses question its universal superiority. Iyengar et al. (2024) demonstrate that for a wide spectrum of models, $K$-fold CV does not statistically outperform the simpler "plug-in" approach (reusing training data for testing evaluation) in terms of asymptotic bias and coverage accuracy. Leave-one-out CV can offer reduced bias, but this improvement is often negligible compared to the evaluation's inherent variability [21]. This indicates that statistical validation alone is insufficient for establishing predictive trustworthiness in chemical applications.

The true measure of a model's value in organic chemistry lies in its experimental correlation—its ability to accurately predict outcomes that are subsequently verified through controlled laboratory experiments. This correlation transforms abstract predictions into chemically meaningful insights, creating a bridge between computational and experimental domains. As Gómez-Bombarelli notes, machine learning studies typically use benchmarking tools to create tables comparing performance between new and established models, but real-world impact requires more than just benchmarking: "If a model claims to improve molecule discovery, it must be tested experimentally" [20].

Methodologies: Protocols for Establishing Experimental-Correlation

Benchmarking and Performance Metrics

Establishing experimental-correlation requires standardized protocols for evaluating ML tools against empirical data. The following methodologies represent current best practices:

Controlled Experimental Validation: Candidate compounds or reactions predicted by ML models undergo synthesis and characterization using established experimental techniques. Key metrics include synthetic yield, reaction efficiency, and structural fidelity compared to predictions [20].

Comparative Benchmarking: Using standardized datasets like Tox21 for toxicity predictions or MatBench for materials properties to compare new models against established baselines [20]. Performance is quantified using correlation coefficients (Pearson's r) between predicted and experimental values [22].

Prospective Experimental Testing: The most rigorous validation involves using ML tools to predict new chemical entities or reactions not in the training data, followed by experimental synthesis and characterization to verify predictions [3].

Cross-Platform Consistency Testing: Evaluating whether models produce consistent results across different computational frameworks and experimental conditions to assess robustness and transferability [20].

The MEDUSA Search Engine: A Case Study in Validation

A recent breakthrough in ML-powered reaction discovery provides an exemplary case study in experimental-correlation. The MEDUSA Search engine was specifically designed for analyzing tera-scale high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data, harnessing a novel isotope-distribution-centric search algorithm augmented by two synergistic ML models [3]. Its validation protocol offers a template for the field:

Table 1: MEDUSA Search Engine Validation Metrics

| Validation Metric | Performance Result | Experimental Correlation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Search Accuracy | High-accuracy identification of isotopic patterns (0.001 m/z tolerance) | Verification against known standards and synthetic compounds [3] |

| Database Scale | Successful operation on >8 TB of 22,000 spectra | Detection of previously unidentified reactions in existing data [3] |

| Computational Efficiency | Acceptable processing time for tera-scale databases | Practical deployment in research workflows [3] |

| Novel Discovery Validation | Identification of heterocycle-vinyl coupling in Mizoroki-Heck reaction | Subsequent experimental confirmation of newly discovered transformation [3] |

The MEDUSA workflow exemplifies the gold standard approach, moving from computational prediction to experimental verification through a structured pipeline:

Diagram 1: MEDUSA Validation Workflow. This workflow demonstrates the process of validating machine learning predictions against experimental mass spectrometry data, culminating in experimental verification of discovered reactions.

Comparative Analysis: ML Tools Versus Traditional Experimental Methods

The transition from traditional methods to ML-assisted approaches requires clear understanding of performance trade-offs. Below we compare key dimensions across methodology types:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Reaction Discovery Methods

| Evaluation Dimension | Traditional Experimental Approach | ML-Powered Approach (e.g., MEDUSA) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Discovery | Months to years for new reaction discovery | Rapid screening of existing data (hours to days) [3] |

| Resource Consumption | High (reagents, solvents, energy) | Minimal additional resource use when mining existing data [3] |

| Data Utilization | Focus on target compounds; most byproducts unanalyzed | Comprehensive analysis of all recorded signals [3] |

| Reproducibility | High when procedures are well-documented | Variable; some models show reproducibility issues [20] |

| Novelty Range | Limited by researcher intuition and literature awareness | Can identify unexpected patterns outside human bias [3] |

| Experimental Correlation | Inherent (method is experimental) | Requires deliberate validation framework [20] |

| Error Rate | Generally low with careful experimentation | False positives require filtering algorithms [3] |

Specialized ML Models in Chemistry

Beyond the MEDUSA platform, several specialized ML architectures have emerged for chemical applications, each with distinct strengths and validation requirements:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Particularly effective for molecular property prediction when trained on large datasets (thousands of structures). These models represent molecules as mathematical graphs where edges connect nodes, analogous to chemical bonds connecting atoms [20].

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs): A "huge success" in replacing computationally demanding density functional theory (DFT) calculations in molecular simulations. When trained on DFT data, MLPs perform similarly but are "way faster," significantly reducing computational energy costs [20].

Transformer Models (e.g., MoLFormer-XL): Using simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) representations, these models learn by predicting missing molecular fragments through autocompletion, showing particular promise when labeled data is scarce [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing a robust experimental-correlation framework requires specific tools and resources. The following table details key solutions for validating ML predictions in organic chemistry:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Experimental-Validation

| Tool/Resource | Function in Validation | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) | Provides precise molecular formula data for correlation with predictions | MEDUSA Search validation of isotopic patterns [3] |

| Benchmarking Datasets (Tox21, MatBench) | Standardized references for comparing model performance against established baselines | Evaluating toxicity predictions and materials properties [20] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Creates training and testing data when annotated experimental data is scarce | MEDUSA's use of synthetic MS data with augmented measurement errors [3] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Orthogonal structural validation method for compounds identified via ML | Supplemental structural verification after MS-based discovery [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Property prediction from structure with strong performance on large datasets | Pharmaceutical company adoption for structure-property linking [20] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Accelerated molecular simulations while maintaining quantum accuracy | Replacing DFT in molecular dynamics simulations [20] |

Visualization Framework for Validation Data

Effective communication of validation results requires careful visual design. The following principles ensure clarity and accuracy when presenting experimental-correlation data:

Color Coding for Enhanced Interpretation

Color serves as a powerful tool for enhancing data visualization when applied purposefully. The following guidelines support effective visual communication of validation results:

Limit Color Categories: Qualitative color scales work best with three to five categories. Beyond eight to ten categories, color matching becomes burdensome [23].

Use Lightness for Gradients: Design sequential color scales with consistent lightness progressions from light (low values) to dark (high values). Avoid rainbow color scales as they are non-monotonic and can misrepresent data relationships [23].

Ensure Accessibility: Use sufficient contrast and avoid color combinations that are indistinguishable to color-blind users. Tools like Datawrapper's colorblind-check can verify accessibility [24].

Implement Intuitive Colors: When possible, use culturally established color associations (e.g., red for attention/stop, green for good/go) to enhance interpretability [24].

Leverage Grey Strategically: Use grey for less important elements or context data, making highlight colors reserved for key findings more prominent [24].

The relationship between validation methodologies and their evidence strength can be visualized through the following framework:

Diagram 2: Validation Evidence Hierarchy. This diagram illustrates the progression of evidence strength from statistical validation through to experimental correlation, with experimental verification representing the strongest form of validation.

The establishment of experimental-correlation as the gold standard for validating ML predictions in organic chemistry represents both a scientific and cultural shift toward more rigorous, reproducible research practices. As the field continues to evolve, the commitment to robust validation—where computational predictions are consistently correlated with experimental outcomes—will determine the pace at which AI-driven discoveries transition from algorithmic curiosities to tangible advancements in chemistry and drug development. The frameworks, methodologies, and tools presented here provide a pathway for researchers to implement this gold standard in their own work, contributing to a foundation of trust that will support the entire scientific community.

Cutting-Edge Methods and Proven Applications for Predictive Chemistry

In modern drug development, the phenomenon of crystal polymorphism—where a single drug molecule can exist in multiple distinct crystalline structures—presents both a significant challenge and a critical opportunity for pharmaceutical scientists. Different polymorphs of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) can exhibit vastly different properties, including solubility, stability, dissolution rate, and ultimately, bioavailability [25] [26]. The pharmaceutical industry has learned this lesson through costly experiences, most famously with ritonavir, where a late-appearing polymorph forced a product recall and reformulation at an estimated cost of $250 million [27] [26]. Similarly, the Parkinson's therapy rotigotine faced a multi-year market outage when a new crystal form precipitated in transdermal patches, drastically reducing drug solubility [26].

Traditional experimental polymorph screening alone cannot guarantee that all relevant polymorphs have been identified, as crystallization conditions cannot be exhaustively explored [25] [28]. This limitation creates substantial risk for drug developers, as undiscovered polymorphs may emerge during manufacturing or storage, potentially compromising product quality, efficacy, and regulatory compliance [27]. Computational crystal structure prediction (CSP) has emerged as a powerful approach to complement experimental screening by theoretically mapping a molecule's polymorphic landscape [29] [28]. However, for CSP to be truly valuable in de-risking pharmaceutical development, it must undergo rigorous large-scale validation to demonstrate its accuracy and reliability across diverse chemical space. This guide examines the current state of large-scale CSP validation, directly comparing the performance of leading methodologies and their supporting experimental evidence.

Comparative Analysis of Large-Scale CSP Validation Studies

Performance Metrics Across Major Validation Studies

Recent breakthroughs in CSP methodology have enabled unprecedented scale and accuracy in polymorph prediction. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from three significant validation studies, highlighting their comparative strengths.

Table 1: Large-Scale CSP Validation Performance Metrics

| Study & Reference | Dataset Scale | Accuracy in Reproducing Known Polymorphs | Computational Cost | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature Communications 2025 [25] | 66 molecules, 137 polymorphs | All experimentally known polymorphs correctly predicted and ranked among top candidates | Not explicitly quantified (uses hierarchical ranking to balance cost/accuracy) | Novel systematic crystal packing search algorithm; Machine learning force fields in hierarchical ranking |

| arXiv 2025 (Fully Automated Protocol) [27] | 49 molecules, 110 polymorphs | Successfully generated structures matching all 110 experimental polymorphs | ~8,400 CPU hours per CSP (significant reduction vs. other protocols) | Fully automated workflow; Lavo-NN neural network potential purpose-built for pharmaceuticals |

| Science Advances 2019 [29] | 5 blind test systems from CCDC | Experimental structure predicted as most stable form for 4/5 systems; All experimental structures within 3 kJ/mol for most complex system | High (uses hybrid DFT with many-body dispersion) | Hierarchical approach combining PBE0+MBD+Fvib; Excellent for relative stabilities |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Validation

The validated CSP protocols employ distinct but complementary methodological strategies, each with rigorous experimental validation.

Nature Communications 2025 Protocol employs a novel systematic crystal packing search algorithm that uses a divide-and-conquer strategy to break down parameter space into subspaces based on space group symmetries [25]. Its energy ranking method combines molecular dynamics simulations using a classical force field, structure optimization and reranking using a machine learning force field with long-range electrostatic and dispersion interactions, and periodic density functional theory calculations for final ranking [25]. The validation encompassed 33 molecules with only one experimentally known crystalline form and 33 molecules with multiple known polymorphs, including challenging cases like ROY and Galunisertib [25]. For all 66 molecules, the method sampled and ranked structures matching known experimental structures within the top 10 candidates, with 26 of the 33 single-form molecules having their best-match candidate ranked in the top 2 [25].

arXiv 2025 Fully Automated Protocol introduces Lavo-NN, a novel neural network potential specifically architected and trained for pharmaceutical crystal structure generation and ranking [27]. This NNP-driven crystal generation is integrated into a scalable cloud-based workflow, achieving complete automation that removes the need for manual specification and expert knowledge [27]. The validation demonstrated particular strength with drug-like molecules, almost all of which were in the Z' = 1 search space [27]. The protocol was further validated through semi-blinded challenges that successfully identified and ranked polymorphs of three modern drugs from powder X-ray diffraction patterns alone [27].

Science Advances 2019 Hierarchical Approach combines the most successful crystal structure sampling strategy (Neumann and co-workers) with the most successful first-principles energy ranking strategy (Tkatchenko and co-workers) from the sixth CCDC blind test [29]. This approach incorporates three crucial theoretical aspects often neglected in CSP protocols: (1) sophisticated treatment of Pauli exchange repulsion and electron correlation with hybrid functionals, (2) inclusion of many-body dispersion interactions and dielectric screening effects, and (3) accounting of harmonic vibrational contributions to free energy [29]. For the most challenging system in the blind test (XXIII), which involved a conformationally flexible former drug candidate with five confirmed polymorphs, the method placed all experimental structures within an exceptionally narrow energy interval of 3 kJ/mol in the final ranking [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow of a Modern CSP Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow of a modern, validated CSP protocol, integrating elements from the leading approaches:

Diagram 1: CSP Method Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Crystal Structure Sampling Methods: The foundational step in CSP involves comprehensively exploring crystallographic space. The Nature Communications protocol uses a novel systematic approach that partitions the search space based on space group symmetries, consecutively searching each subspace [25]. Similarly, the arXiv protocol employs Monte Carlo parallel tempering algorithms with tailor-made force fields to generate initial crystal structures [27] [29]. For flexible molecules, conformational diversity is incorporated by sampling multiple molecular conformers generated from isolated-molecule optimizations, though this rigid-molecule approximation is later relaxed during refinement [28].

Energy Ranking Methodologies: Accurate energy ranking presents the most computationally demanding aspect of CSP. The hierarchical approach proves most effective, beginning with faster methods to prune unlikely candidates before applying more accurate, expensive techniques [25] [29]. The Nature Communications protocol progresses from molecular dynamics with classical force fields, to machine learning force fields with long-range electrostatics and dispersion, and finally to periodic density functional theory for the final shortlist [25]. The Science Advances approach advances from PBE+TS to PBE+MBD to PBE0+MBD, ultimately incorporating vibrational free energy contributions (Fvib) to yield Helmholtz free energies that account for thermal entropic effects [29].

Experimental Validation Procedures: CSP validation relies heavily on comparison to experimentally characterized polymorphs from sources like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [25]. Preferred experimental data comes from neutron diffraction studies, low-temperature single-crystal X-ray diffraction, and room temperature powder X-ray diffraction studies [25]. Successful prediction requires generating structures with RMSD (root mean square deviation) better than 0.50 Å for spherical clusters of at least 25 molecules compared to experimental structures [25]. Additional validation comes from prospective blinded studies, such as CCDC blind tests where participants predict crystal structures based solely on 2D molecular formulas [27] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for CSP Implementation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in CSP Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Classical FFs, Tailor-made FFs [29] | Initial structure generation and sampling through Monte Carlo parallel tempering algorithms |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Lavo-NN [27], QRNN [25], Dual-cutoff MLPs [30] | Intermediate refinement and ranking with near-DFT accuracy at reduced computational cost |

| Quantum Chemistry Methods | PBE+TS, PBE+MBD, PBE0+MBD, r2SCAN-D3 [25] [29] | Final energy ranking with high-accuracy treatment of exchange-correlation and dispersion |

| Sampling Algorithms | Systematic packing search [25], Monte Carlo parallel tempering [29] | Comprehensive exploration of crystallographic space and molecular conformations |

| Free Energy Calculators | Harmonic approximation, quasi-harmonic methods [29] | Incorporation of temperature-dependent stability through vibrational contributions |

| Validation Databases | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [25], CCDC Blind Test compounds [29] | Experimental reference structures for method validation and benchmarking |

The large-scale validation of CSP methods marks a transformative advancement for pharmaceutical development. With demonstrated accuracy across diverse molecular sets—reproducing all known polymorphs for 66 molecules in one study and 49 in another—CSP has transitioned from theoretical promise to practical utility [25] [27]. The integration of machine learning force fields and automated workflows has simultaneously improved accuracy while dramatically reducing computational costs, enabling CSP to be deployed earlier in drug discovery pipelines [27].

These validated CSP approaches now provide pharmaceutical scientists with powerful capabilities for comprehensive polymorphic landscape mapping, salt and cocrystal screening, intellectual property protection, and manufacturing risk mitigation [26]. By identifying potentially more stable polymorphs that have not yet been observed experimentally, CSP enables proactive risk management rather than reactive crisis response [25] [28]. As these methods continue to evolve, addressing more complex systems with multiple molecules in the asymmetric unit and further improving computational efficiency, CSP is positioned to become an indispensable component of pharmaceutical solid-form development, ultimately ensuring the delivery of safer, more effective, and more reliable drug products to patients.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) into organic chemistry has catalyzed a transformative shift in how researchers predict reaction outcomes. These data-driven approaches promise to accelerate synthetic planning and reaction optimization, yet their real-world utility hinges on a critical factor: robust validation with experimental data. As machine learning models for predicting chemical reaction yields and selectivities become increasingly sophisticated, comprehensive benchmarking against experimental results is essential to establish reliability, identify limitations, and guide future development. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of contemporary ML approaches by examining their predictive accuracy, generalization capabilities, and practical performance when applied to experimental datasets. The findings underscore a pivotal theme within the broader thesis of validating machine learning predictions in chemical research: despite impressive in-distribution benchmark performance, significant challenges remain in achieving robust, out-of-distribution generalization, necessitating rigorous experimental validation as an indispensable component of model development and deployment.

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for Reaction Prediction

The efficacy of machine learning models for reaction outcome prediction is commonly evaluated on several benchmark tasks, including yield prediction for catalytic reactions and product identification in forward synthesis. Performance varies considerably across model architectures, input representations, and the nature of the validation split, highlighting the importance of the evaluation design itself.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Models on Yield Prediction Tasks

| Model | Architecture / Approach | Dataset | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GraphRXN [31] | Graph Neural Network (GNN) | In-house HTE Buchwald-Hartwig | R² (Yield Prediction) | 0.712 |

| ReaMVP [32] | Multi-view Pre-training (Sequence + 3D Geometry) | Buchwald-Hartwig | R² (Yield Prediction) | State-of-the-art |

| DKL-GNN [33] | Deep Kernel Learning with GNN | Buchwald-Hartwig | RMSE (Yield Prediction) | Comparable to GNNs, with uncertainty |

| EnP Model [34] | Ensemble of Fine-tuned Chemical Language Models | Asymmetric β-C(sp³)–H Activation (220 reactions) | Accuracy on Unseen Reactions | High reliability in prospective validation |

Table 2: Performance on USPTO Reaction Product Prediction Benchmarks

| Model | Architecture | USPTO-50K (Top-1 Accuracy) Known Class | USPTO-50K (Top-1 Accuracy) Unknown Class | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RetroExplainer [35] | Multi-sense & Multi-scale Graph Transformer | 56.9% | 54.2% | Interpretable, molecular assembly |

| FlowER [36] | Flow Matching on Bond-Electron Matrix | ~95% valid SMILES generation | Effective OOD generalization | Strict mass/electron conservation |

| BART (Author Split) [37] [38] | Transformer (SMILES-based) | 55% | - | Highlights OOD performance drop |

Key Performance Insights from Comparative Analysis

- Generalization Gap: A critical insight from comparative studies is the overoptimism of random data splits. When models are evaluated on more realistic out-of-distribution (OOD) splits—such as by separating reactions by patent author or publication year—performance can drop significantly. For instance, a standard BART model's top-1 accuracy dropped from 65% on a random split to 55% on an author-based split, highlighting a ~10% generalization gap [37] [38].

- Value of Multi-View and Pre-training: Models that incorporate multiple representations of chemical data consistently show enhanced performance. The ReaMVP framework, which leverages both sequential (SMILES) and 3D geometric views of reactions through a two-stage pre-training strategy, achieved state-of-the-art performance on the Buchwald-Hartwig dataset and demonstrated superior generalization on out-of-sample data [32].

- Uncertainty Quantification: The Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) model combines the representation learning power of GNNs with the reliable uncertainty estimates of Gaussian Processes. This provides accurate yield predictions comparable to other GNNs, but with the crucial addition of uncertainty quantification, which is vital for decision-making in experimental optimization [33].

- Mechanistic Interpretability and Conservation: The FlowER model addresses a common failure mode of sequence-based models—the violation of mass conservation. By recasting reaction prediction as electron redistribution using flow matching on a Bond-Electron matrix, FlowER ensures 100% atom and electron conservation, drastically reduces hallucinatory predictions, and provides inherently interpretable, mechanistic pathways [36].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Model Validation

The validation of ML models in organic chemistry relies on rigorous, standardized experimental protocols and high-quality datasets. The methodologies below are commonly employed to generate the critical data needed for training and benchmarking.

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Data Generation

Protocol Objective: To generate high-quality, consistent, and large-scale reaction data for training and testing ML models [31] [33].

- Reaction Selection: A catalytic reaction with high practical utility (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig amination) is selected.

- Experimental Design: A multidimensional grid of reaction conditions is defined, systematically varying key parameters such as:

- Aryl halide substrate

- Ligand

- Base

- Additive

- Parallelized Execution: Reactions are set up and run in parallel using robotic liquid handling systems and automated reactor platforms [31].

- Analysis and Quantification: Reaction outcomes (e.g., yield) are determined for each well using standardized analytical techniques, typically ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) or gas chromatography (GC) [31].

- Data Curation: The resulting data (reactant structures, conditions, and yields) are compiled into a structured dataset, ensuring consistency and accurate atom mapping [39].

Prospective Experimental Validation of Model Predictions

Protocol Objective: To assess the real-world utility and generalizability of a trained ML model by testing its novel predictions in a wet lab [34].

- Model Prediction:

- For yield/selectivity prediction, a regressor (e.g., the EnP model) predicts the outcome for a set of unseen reactant and condition combinations [34].

- For reaction discovery or ligand design, a generative model (e.g., a fine-tuned generator, FnG) proposes novel chemical structures or transformations [34] [3].

- Candidate Selection: Predictions are ranked based on predicted score (e.g., high yield) or novelty, and a subset is selected for experimental testing.

- Wet-Lab Synthesis: The selected reactions are conducted manually or using automated systems by chemists who are typically blinded to the predicted outcomes to avoid bias.

- Outcome Analysis: The experimental results (e.g., yield, enantiomeric excess) are measured and compared to the model's predictions to calculate accuracy and validate the model's extrapolative capabilities [34].

Tera-Scale Mass Spectrometry for Reaction Discovery

Protocol Objective: To mine existing large-scale HRMS data for undiscovered reactions, validating a model's ability to generate plausible chemical hypotheses [3].

- Data Aggregation: Collect terabytes of historical high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data from various reaction screenings.

- Hypothesis Generation: Use algorithms (e.g., BRICS fragmentation or LLMs) to generate potential reaction pathways and corresponding product molecular formulas [3].

- Automated Search: Employ a specialized search engine (e.g., MEDUSA Search) with an isotope-distribution-centric algorithm to scan the MS data for the hypothesized ions [3].

- Validation: When a hypothesized ion is detected, perform follow-up experiments, such as targeted synthesis or tandem MS, to confirm the structure and verify the predicted transformation [3].

Diagram 1: Experimental validation workflow for ML models in organic chemistry, covering High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE), Prospective Validation, and Mass Spectrometry (MS) Data Mining.

Visualization of Model Comparison and Validation Logic

The following diagram synthesizes the key relationships between different model architectures, their defining characteristics, and their performance in experimental validation, as discussed in this guide.

Diagram 2: Relationship between model architectures, key characteristics, and experimental performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational tools, datasets, and algorithms that function as essential "reagents" in the workflow of developing and validating ML models for reaction prediction.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Reaction Prediction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPTO Dataset [39] [32] | Reaction Database | Provides a large-scale source of published chemical reactions for model training and benchmarking. | Training foundation models for product prediction [39] [32]. |

| Mech-USPTO-31K [39] | Mechanistic Dataset | Offers curated arrow-pushing diagrams for training models on electron movement and reaction mechanisms. | Developing mechanistic predictors like FlowER [36]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotics [31] | Experimental Platform | Generates high-quality, consistent reaction data for model training and validation. | Creating the Buchwald-Hartwig dataset for yield prediction [31] [33]. |

| RDKit [39] [32] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Handles molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and conformer generation. | Extracting reaction templates and generating 3D molecular geometries [39] [32]. |

| MEDUSA Search [3] | Search Algorithm | Enables efficient mining of tera-scale mass spectrometry data for specific ions. | Validating hypotheses of novel reaction products in historical data [3]. |

| Differential Reaction Fingerprint (DRFP) [33] | Reaction Representation | Creates a binary fingerprint for a reaction from SMILES, useful for conventional ML. | Featurizing reactions for input into models like DKL [33]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [33] | Optimization Algorithm | Uses a surrogate model (e.g., a GP) to efficiently navigate a chemical space toward optimal conditions. | Optimizing reaction yields guided by a model with uncertainty estimates [33]. |

The objective comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that while machine learning models have become powerful tools for predicting reaction outcomes, their validation against rigorous experimental data is non-negotiable. Models incorporating multi-view learning, mechanistic principles, and uncertainty quantification are showing promising improvements in both accuracy and generalizability. However, the persistent gap between in-distribution and out-of-distribution performance underscores that the field has not yet solved the challenge of robust chemical extrapolation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this implies that the most effective path forward is a tightly-knit feedback loop between predictive in-silico models and high-quality experimental validation, ensuring that these powerful tools can be deployed with confidence in real-world discovery and development settings.

The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a transformative shift with the integration of machine learning (ML) into its core workflows. Traditional drug development burns through $2.6 billion and 15 years per approved medication on average, with high failure rates at every stage [40]. Validated ML tools are emerging as a powerful strategy to de-risk this process, offering predictive power that can identify promising candidates and flag potential failures earlier. Industry studies project AI could save pharmaceutical companies $25 billion in clinical development alone by automating processes and reducing late-stage trial failures [40]. This guide examines prospective case studies of validated ML tools, comparing their performance against traditional methods and alternative approaches, with a specific focus on applications within organic chemistry research.

Case Study 1: ML-Powered Reaction Discovery in Mass Spectrometry Data

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

MEDUSA Search (Machine-lEarning Powered Decoding of mass spectrometry data for Uncovering Synthetic Applications) addresses the challenge of tera-scale high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data analysis for reaction discovery [3]. The methodology enables "experimentation in the past" by rigorously investigating existing data instead of conducting new experiments.

Detailed Methodology:

- Hypothesis Generation: The system generates potential reaction pathways based on breakable bonds and fragment recombination, using either prior knowledge, BRICS fragmentation, or multimodal LLMs.

- Theoretical Pattern Calculation: For a given chemical formula and charge, the engine calculates the theoretical isotopic pattern of the ion.

- Coarse Spectra Search: The two most abundant isotopologue peaks are searched in inverted indexes across the database (0.001 m/z accuracy).

- Isotopic Distribution Search: A machine learning regression model estimates an ion presence threshold. An in-spectrum isotopic distribution search algorithm returns the cosine distance as a similarity metric between theoretical and matched distributions.

- False Positive Filtering: A second ML classifier, trained on synthetic data, filters false positive matches using features of the matched isotopic pattern.

The ML models were trained exclusively on synthetic MS data, constructing isotopic distribution patterns from molecular formulas and augmenting data to simulate instrument measurement errors, thus avoiding the bottleneck of manual data annotation [3].

Performance Comparison & De-risking Impact

MEDUSA Search was validated on a database of more than 8 TB of 22,000 spectra accumulated from diverse chemical transformations. Its application to the well-studied Mizoroki-Heck reaction successfully identified several previously undescribed transformations, including a heterocycle-vinyl coupling process, demonstrating its capability to uncover complex chemical phenomena overlooked in manual analysis [3].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of MEDUSA Search Engine

| Performance Metric | MEDUSA Search | Traditional Manual Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Data Volume Processed | >8 TB (22,000 spectra) | Limited by human capacity |

| Key Discovery | Novel heterocycle-vinyl coupling in Mizoroki-Heck | Focused on desired product; byproducts overlooked |

| Analysis Approach | Comprehensive, hypothesis-agnostic ion candidate search | Targeted, hypothesis-driven |

| Resource Consumption | No new experiments or chemicals (Green Chemistry) | Requires repeated experiments, reagents, waste handling |

This tool de-risks pharmaceutical development by enabling exhaustive, cost-efficient retrospective analysis of existing data. It mitigates the risk of overlooking critical reaction pathways or byproducts and reduces the resource risk associated with continuous new experimentation.

Case Study 2: Validated Diagnostic Tools for Preclinical Safety

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

The FInD (Foraging Interactive D-prime) Color system is a rapid, self-administered computer-based tool for assessing color vision deficiencies (CVDs), which can serve as biomarkers for neuro-ophthalmic and systemic diseases [41]. Its robust validation provides a template for diagnostic tool development in preclinical safety assessment.

Detailed Methodology:

- Apparatus: Experiments are programmed in MATLAB with Psychtoolbox and presented on a gamma-corrected display. Luminance of the mid-grey background is standardized at 90.3 cd/m² [41].

- Stimuli: Gaussian blobs (σ=1°, support diameter=4°) in dynamic luminance noise are used to mask potential luminance artefacts.

- FInD Color Detection Task: Measures detection thresholds for L-, M-, and S-cone isolating stimuli to classify photoreceptor-level color sensitivity.

- FInD Color Discrimination Task: Measures hue discrimination thresholds around multiple directions on an equiluminant color plane to quantify the resolution of color perception.

- Validation & Classification: Thresholds from 19 color-normal and 18 inherited color-atypical observers were collected. Unsupervised machine learning (K-means clustering) was used on the detection and discrimination thresholds to classify CVD type and severity, confirming functional subtypes without prior genetic data [41].

Performance Comparison & De-risking Impact

The FInD Color tasks were compared directly against established clinical tools: the Hardy-Rand-Rittler (HRR) pseudoisochromatic plates and the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 hue test (FM100) [41]. The tool demonstrated high sensitivity and repeatability in reliably detecting inherited CVDs.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Color Vision Assessment Tools

| Assessment Tool | Testing Duration | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | CVD Classification Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FInD Color Tasks | Rapid, self-administered | Quantifies type/severity; high sensitivity | Requires computer setup | Unsupervised ML on behavioral thresholds |

| Anomaloscope (Gold Standard) | Extensive testing time | Precise red-green CVD diagnosis | Expensive; requires expert administration | Red-green matching ranges |

| HRR Plates | Rapid screening | Can classify tritan defects | Coarse severity scale; requires clinician | Symbol identification & location |

| FM100 Test | Extremely time-consuming | Complete color discrimination measurement | Vague error score interpretation | Total error score & axis |

The deployment of a validated tool like FInD de-risks development in several ways. It provides a quantitative and repeatable biomarker assessment, moving beyond the coarse, qualitative results of older tests. The use of unsupervised ML for classification offers a data-driven, objective method for identifying and grouping deficiencies, reducing diagnostic risk and subjectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials essential for implementing and validating ML-driven approaches in pharmaceutical and chemical research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in ML Validation & Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (HRMS) | Generates tera-scale, high-fidelity data on chemical compositions; the primary data source for reaction discovery engines like MEDUSA [3]. |

| Gamma-Corrected Display & Photometer | Ensures visual stimuli are presented with consistent and accurate color/luminance; critical for obtaining reliable data in visual assessment tools like FInD [41]. |

| Synthetic Data Generation Pipelines | Creates large volumes of annotated training data (e.g., simulated mass spectra, visual stimuli) to train ML models where real labeled data is scarce, mitigating a major bottleneck [3]. |

| Cone-Isolating Stimuli | Visual targets designed to selectively stimulate individual L-, M-, or S-cone types; essential for dissecting the specific biological components of a complex system like color vision [41]. |

| Dynamic Luminance Noise | A visual background of randomly changing luminance; used to mask non-chromatic cues, ensuring that tasks measure the intended color detection or discrimination ability [41]. |

Visualizing ML Validation Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for the machine learning tools discussed in the case studies, highlighting the validation steps that ensure their reliability.

MEDUSA Search Engine Workflow

FInD Color Diagnostic & ML Classification

The prospective case studies of MEDUSA Search and the FInD Color system demonstrate a clear paradigm shift: validated ML tools are actively de-risking pharmaceutical and chemical development. They achieve this by converting vast, complex datasets into reliable, actionable predictions, thereby reducing both financial risks and timelines. MEDUSA mitigates resource risk and reveals hidden chemistry, while FInD provides a robust, quantitative framework for biomarker assessment. The consistent themes across these tools—the use of synthetic data for training, multi-stage validation protocols, and objective ML-driven classification—provide a replicable blueprint for the development of future tools. As the industry moves forward, embedding these rigorous validation principles from day one will be paramount for translating the promise of AI into tangible improvements in drug success rates and patient outcomes.

The field of organic chemistry is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional labor-intensive experimentation to data-driven discovery processes. This shift is necessitated by the enormous backlog of experimental data accumulated in research laboratories worldwide—terabytes of high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data containing undiscovered chemical reactions recorded but never analyzed. The central challenge lies in the "human factor" limitations of manual analysis, where researchers typically examine only desired products and a few known byproducts, leaving the vast majority of MS signals unattended [3].

Machine learning-powered search engines represent a technological breakthrough that addresses this challenge directly. These systems enable what researchers term "experimentation in the past"—mining existing experimental data to test chemical hypotheses without conducting new experiments [3]. This approach offers significant advantages for drug development professionals and research scientists, including reduced chemical consumption, eliminated waste generation, and accelerated discovery timelines. For the validation of machine learning predictions in organic chemistry, these tools provide an empirical foundation for verifying computational models against actual experimental evidence stored in legacy data.

Technology Comparison: MEDUSA Search Versus Alternative Approaches

The landscape of tools for chemical data analysis spans multiple methodologies, from manual approaches to specialized automated systems. The following comparison examines MEDUSA Search alongside other common strategies researchers employ for reaction discovery and analysis.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Reaction Discovery Methodologies

| Methodology | Data Processing Capacity | Key Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDUSA Search | Tera-scale (8+ TB demonstrated; 22,000 spectra) [3] | Automated hypothesis testing; Isotopic distribution-centric algorithm; Minimal false positives [3] | Requires hypothesis generation; Limited to MS data | Large-scale retrospective reaction discovery; Green chemistry applications |

| Manual Analysis | Single experiments to small batches | Intuitive interpretation; No specialized software needed | Human bias toward expected products; Limited coverage [3] | Targeted analysis of known reaction pathways; Small-scale studies |

| Traditional Search Algorithms | Medium to large datasets | Established workflows; Good for targeted compound identification [3] | Narrow application scope; High false positive rates without isotopic distribution [3] | Metabolomics; Proteomics; Targeted compound identification |

| MolView | Individual compounds and spectra | Interactive visualization; Integration with PubChem and RCSB [42] | Not designed for large-scale data mining; Manual operation required | Educational purposes; Single compound visualization and analysis |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of MEDUSA Search Engine

| Performance Metric | MEDUSA Search Result | Significance for Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Search Accuracy | Cosine distance similarity metric with ML-derived thresholds [3] | Reduces false positives while maintaining sensitivity for novel reaction discovery |